Written and compiled by Lia Markey, Suzanne Karr Schmidt, and Stephanie Reitzig as a companion to the 2020 Newberry exhibition and book (Northwestern University Press) by the same title. Entries here have been adapted from texts by James R. Akerman, Ikumi Croccol, Olivia Dill, Christopher Fletcher, Marisa Guo, Elisa J. Jones, Suzanne Karr Schmidt, Stephanie Lee, Risa Puleo, Sandra Racek, and John Sullivan.

Introduction

Much like our Internet Age, the period known as the Renaissance (circa 1350–1600) experienced significant technological innovations. Inventions like the printing press, gunpowder, and the compass dramatically transformed the world, while others, such as eyeglasses and new medicines, quietly reshaped daily life.

“Printing, gunpowder, and the magnet. . . . These three have changed the whole face and state of things throughout the world.” – Francis Bacon, 1620

The renowned sixteenth-century engraved series the Nova Reperta (New Discoveries) depicts inventions in ways that can deepen our understanding of relationships between the local and the global, the individual and the community, and progress and destruction. Many so-called Western inventions represented in the prints, such as the compass, were developed in areas outside Europe long before the Renaissance. New breakthroughs in technology, such as printmaking, were not necessarily born in the minds of individual genius inventors but rather resulted from collaboration. The Nova Reperta challenges the viewer to consider the negative impact of some new discoveries, like gunpowder, and how invention was intimately tied to warfare, disease, and colonization.

The first section provides an introduction to the world of the Nova Reperta. Then the three middle sections explore the following themes: Navigation and Colonization, Machines and Warfare, and Transformation and Vision. A final section explores major publications about invention in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. By examining the idea of innovation during the early modern period (1350-1900), this collection encourages us to consider progress in our own time.

Essential Questions:

- What do you consider to be the major inventions of the Renaissance?

- What are today’s nova reperta (new discoveries)?

- How is technological change transforming life in the twenty-first century?

Nova Reperta

In late 1580s Florence, Flemish artist Johannes Stradanus designed a series of twenty engravings titled Nova Reperta, becoming the first person to depict in print major recent inventions and updates to ancient ones. A versatile artist who travelled throughout Italy and Flanders, he worked in various media at the Medici court and for private patrons like Luigi Alamanni. Collaborating with Alamanni, Stradanus both celebrated innovation and promoted debates about it with the Nova Reperta. He created detailed drawings for each print and sent them from Florence to Antwerp to be engraved and printed by Philips Galle. The engravings were popular among scholars and print collectors, and the Galle family produced multiple editions into the early seventeenth century.

Following the title page that introduces the series, the first 19 engravings seen linked in the Newberry’s album represent: America, Magnet (Compass), Gunpowder, Book Printing, Iron Clock, Guaiacum (a treatment for syphilis), Distillation, Silkworm, Stirrup, Water Mill, Windmill, Sugar, Oil Painting, Eyeglasses, Longitude, Armor Polishing, Astrolabe, and Engraving.

The following images, maps, and texts provide insight into the changing world of the Renaissance that Stradanus represents in the print series. The maps reveal two very different modes of representing the globe, while the Gutenberg page and portrait demonstrate the significance of this major Renaissance invention, the printing press.

Image 1: Philips Galle after Johannes Stradanus, Nova Reperta frontispiece, circa 1588.

Image 2: Gregorio Dati, Map of the Holy Land in La Sfera, circa 1425.

La Sfera provided Florentines with a summary of important geographical and celestial information they needed to know before the age of print made such information, including maps, more accessible. Its pedagogical text on the astronomic and geographic sciences includes hand-drawn maps based partially on common navigational charts of the day. This Holy Land map is not particularly current to 1425, and may refer to the ancient Ptolemaic model that put the earth at the center of the universe.

-James R. Akerman

Image 3: Anonymous, Cordiform Fool’s Map, circa 1590.

The fool’s motley cap harbors an enduring cartographic mystery. This anthropomorphic heart-shaped projection of the world marries sixteenth-century mathematic developments with concerns about what lies undiscovered outside Europe. The map’s designer and artist also remain unknown. Only the projection’s adoption of geographical details from the world map in Flemish cartographer Abraham Ortelius’s 1587 Theater of the World atlas helps provide a possible date. Suggesting that it is a fool’s errand to truly know the globe, this map combines cartography with tongue-in-cheek humor, a visual mockery of European power, exploration, and vanity.

-Stephanie Lee

Image 4: Johannes Gutenberg, Gutenberg page (Cat. 16), circa 1454.

Despite an Eastern tradition of movable type beginning around 1000 AD, Western book printing was thought to begin with Johannes Gutenberg, who both invented new tools (hand molds for casting individual, movable type) and adapted existing technology (the wine press) to print books. Gutenberg and his team took more than two years to print 180 copies of his Bible, just one-third the time a scribe needed to produce one by hand. These deluxe Bibles proved that the new technology celebrated by Stradanus could produce works of comparable quality.

-Christopher Fletcher

Image 5: André Thevet, Gutenberg in Les vrais pourtraits et vies des hommes illustres, 1584.

In Les vrais pourtraits, French cosmography André Thevet collected 232 biographies, accompanied by explanations of where and how he found them. Many of the portraits he claimed to have discovered, however, were plagiarized or falsified. Here, Thevet portrays Johannes Gutenberg as the inventor of the printing press, holding a punch and matrix to represent his movable metal type. By contrast, the Nova Reperta print representing the printing press does not identify Gutenberg as the inventor, reflecting sixteenth-century uncertainty around Gutenberg’s role in the invention of printing.

-Elisa J. Jones.

Questions to Consider:

- What inventions are highlighted in the Nova Reperta’s frontispiece (first page)?

- How are the inventions represented in this image?

- How do the medium, format, and style of the two maps in this section differ? How do they reflect the changing world of the sixteenth century?

- How does Gutenberg fit the single genius inventor cliché, and how should we think about his contribution today?

Navigation and Colonization

Renaissance exploration created a new conception of the world, but also led to the ravages of colonization. The Nova Reperta engravings, like many sixteenth-century atlases, books, and maps, represent astrolabes and other navigational tools that facilitated global travel. Europeans used these instruments to reach the “New World,” later named America.

The first plate of the Nova Reperta portrays “America” allegorically, as a jarringly nude Native woman. Such aestheticized depictions were common and served to obscure the violence of colonization. Similarly, contemporary sources praising navigators Christopher Columbus and Amerigo Vespucci hardly ever acknowledge the destructive effects of colonization and its racially motivated justifications.

Image 1: Philips Galle after Johannes Stradanus, America (Plate 2) in Nova Reperta, circa 1588.

Image 2: Abraham Ortelius, Title Page of Theatrum oder Schawbüch des Erdtkreijs, 1580.

Antwerp publishing sparked close collaboration. In 1570, cartographer Ortelius published the first modern world atlas. Theater of the World prompted many translations and updates reflecting new geographic discoveries. In its famed frontispiece of the four continents personified, “America,” nude except for a feathered cap, reclines beneath the title. She wields a club and grips a man’s severed head, with a bow and a hammock nearby that reappear in Stradanus’s America plate, published by Ortelius’s friend Philips Galle.

-John Sullivan

Image 3: Lucas Janszoon Waghenaer, Title Page of Speculum nauticum, 1588.

Nautical cartographer Waghenaer introduces his navigational manual, Mariner’s Mirror, with an assortment of the functional tools that sea travel required. Cross-staffs, quadrants, and mariner’s astrolabes are suspended from a decorative border. Dividers and compasses stand in the corners below male figures who use sounding lines to measure the depth of the water. This book provided navigators with accurate information and helpful instructions, while declaring precision essential to navigation. The influential text was disseminated widely and translated into several languages.

-Olivia Dill

Image 4: Hernán Cortés, Mexico City and the Gulf of Mexico, 1524.

The so-called Cortés Map gave Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain Charles V and other Europeans a first glimpse of the “New World.” Its overhead view of the region of Tenochtitlan (present-day Mexico City) is based on an Indigenous source and the map’s center references the ritual activities that took place at the Templo Mayor. Charles V’s Habsburg flag marks the place where Cortés stopped the city’s freshwater supply to conquer its citizens during his ongoing and brutal campaign.

-Risa Puleo

Image 5: Theodor de Bry, Columnam a Praefecto prima navigatione locatam venerator Floridenses, circa 1591.

Like Stradanus, Flemish artist Theodor de Bry traveled throughout Europe and published numerous thematic volumes, which often intertwined intellectual progress, artistic innovation, and dramatic anecdotes. Whereas Stradanus’s print shows the Italian Amerigo Vespucci at the moment of “discovery,” De Bry depicts the French explorer René Goulaine de Laudonnière’s 1565 expedition to establish a Huguenot colony in Florida. De Bry never traveled to America and instead based his drawings off the images and descriptions of artist Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, who accompanied Laudonnière’s expedition.

-Stephanie Lee and Risa Puleo

Questions to Consider:

- Consider Stradanus’s image of the New World, keeping in mind that Stradanus himself never visited the Americas. What does the terrain look like? Do you see any buildings? What animals are there, and how would you describe them? What does this landscape seem intended to convey about the Americas and the people who live there? Why do you think the female Indigenous figure is represented the way that she is?

- Waghenaer’s Speculum nauticum emphasized the importance of precise information and navigational instruments. Thinking about the composition, objects, and people in the frontispiece, how does the illustration reflect these ideas?

- Cortés’ map (which was likely based on an Indigenous source) shows floating agricultural beds called chinampas and Tenochtitlan’s complex water system, which enabled the city to survive in the middle of a brackish lake. How does the technologically advanced civilization seen in this map contrast with Stradanus and Ortelius’s depictions of Native peoples?

- Like Stradanus’s print, De Bry’s “encounter” scene was drawn from a European perspective by someone who had never traveled to the Americas. What aspects of European exploration and colonization do he and Stradanus emphasize, and which do they downplay or omit?

Warfare and Machines

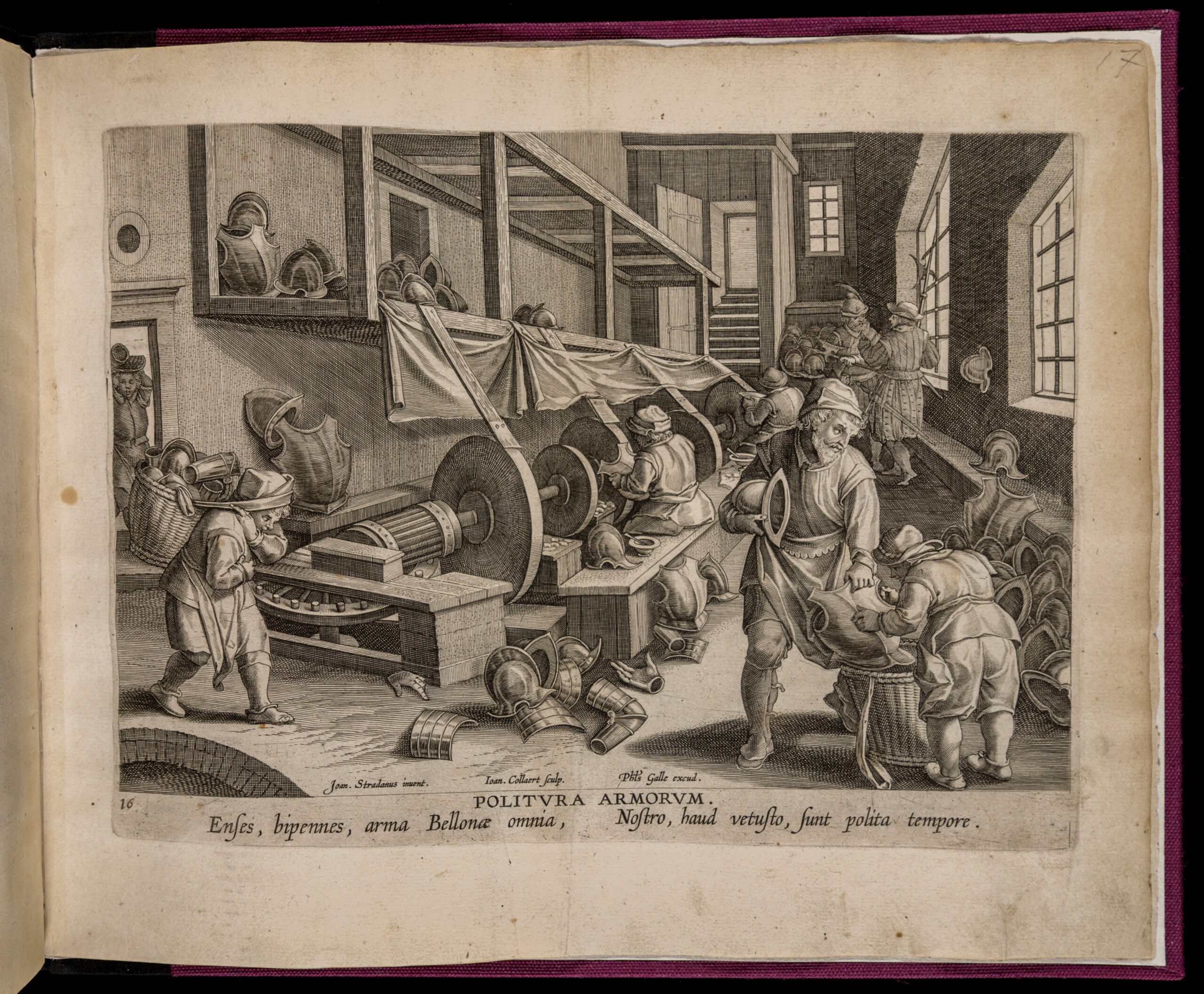

Throughout the Nova Reperta engravings, machines represent innovative devices for war, agriculture, and timekeeping. The prints cleverly display many secrets of how they work.

Gunpowder and war machines expedited the conquest of the Americas and fueled European wars. Gears and wheels polished armor for the battlefield and powered wind and water mills and clocks at home. Many machines harnessed natural energy, increased the efficiency of human labor, and used animal power more effectively. Others dramatically changed daily life, such as the increased accuracy of the iron clock, which helped transform the perception of time in the Renaissance.

Image 1: Philips Galle after Johannes Stradanus, Armor Polishing Plate (Plate 18) in Nova Reperta, circa 1588.

Image 2: Roberto Valturio, Cannons in De re militari, circa 1483.

The second illustrated book printed in Italy, Of Military Matters, contains woodcut images of inventa or “inventions” like cannons, that depict the newest siege technology and war machines, and the increasingly dangerous use of gunpowder. Valturio was a scholar, not a military expert, but his patron, Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta of Rimini, may still have used the manuscript for military strategy. First completed in 1460, it well preceded Malatesta’s successful 1465 campaign against the Ottomans.

-Marisa Guo

Image 3: Luis Collado, Mortar in Prattica manvale dell’artiglieria, 1606.

Luis Collado, a Spanish military officer active in Italy, penned a Practical Artillery Manual. Here he discusses the mortar’s construction and use, with a bold woodcut illustration following the dramatic parabolic trajectory. The ball veers downward toward two unprotected central towers with slender spires, possibly marking an eastern site with a pair of minarets. Technology would soon level the playing field, when Ottoman forces used mortars extensively against the Habsburgs in the Long Turkish War (1593-1606).

-Suzanne Karr Schmidt

Image 4: Agostino Ramelli, Windmill in Le diverse et artificiose machine, 1588.

Military engineer Ramelli presents 195 Diverse and Skillful Machines for his patron Henry III of France. These imaginative projects harness natural energy to raise water, bombard castles, span rivers, and rotate books for study. His depiction of a wind-powered grain mill is among the earliest published images describing the interior of a windmill by dramatically opening up the mill’s walls. Ramelli’s internal vantage point and gearing system coupling the sail to the grindstone reappears in the Nova Reperta.

-Olivia Dill

Image 5: Vittorio Zonca (designer) and Francesco Bertelli (printer), Filatoio da aqua, 1656.

The Novo teatro de machine et edificii, written by Paduan architect and engineer Vittoria Zonca and posthumously published in 1607, exhibits both recent mechanical advancements and imagined future innovations. One prominent example is the filatoio, a silk-spinning hydraulic mill which originated around 1330. Its inclusion in the Novo teatro evinces the economic importance of both waterpower and silk spinning in the early modern European economy.

-John Sullivan

Questions to Consider:

- How do these five images demonstrate to the viewer how machines work?

- Both Zonca’s and Ramelli’s illustrations celebrate the ingenuity of new inventions. What problems do these machines solve? How do they take advantage of the natural world, and what kind of mechanisms (gears, levels, etc.) enable them to do so?

- The devices depicted in Stradanus’s, Valturio’s, and Collado’s images all improved Europeans’ abilities to wage war. What impact do you think these new technologies had on life in Europe and elsewhere?

Transformation and Vision

The commodities represented in the Nova Reperta served an increasingly global economy linked by health threats. Physicians cooked down guaiacum wood from the Caribbean to treat the syphilis epidemic. Alchemists distilled substances into healing or intoxicating liquors. Laborers refined Brazilian sugar cane and pressed Tuscan olives into oil for consumption. Women bred silkworms, originally from China, for silk production.

Other processes changed and refined during this period transformed how Europeans saw the world: the grinding of eyeglass lenses improved sight; the use of oil expanded the possibilities of painting; and copperplate engravings allowed for more detailed visual information to circulate.

Image 1: Philips Galle after Johannes Stradanus, Distillation (Plate 8) in Nova Reperta, circa 1588.

Image 2: Adam Lonicer, Distillation tools in the Kreutterbuch, 1546.

Sixteenth-century distillation had many uses: it could aid medical treatments, facilitate mining and metallurgy, and produce strong, potable spirits. Lonicer’s Herbal addresses both artisans involved in these trades and a broader audience by combining theoretical distillation principles with innovative practical advice, like the use of steam. Flasks, ovens, and other apparatus were used to distill balsam, turpentine oil, and other plant spirits. The hand-colored woodcuts distinguish among materials such as glass (green), copper (brown), and lead (gray).

-Sandra Racek

Image 3: Marcus Hieronymus Vida (author) and Samuel Pullein (translator) The Silkworm: A Poem; In Two Books, 1750.

In 1750, Samuel Pullein translated Marcus Hieronymus Vida’s 1527 poem The Silkworm into English, adding a British twist by substituting Albion for Italy and the Princess of Wales for Isabella d’Este, the poem’s dedicatee. Stradanus also dedicated his Vermis sericus series on silk production to a woman, Costanza Alamanni, reflecting the way silk production in the Renaissance was billed as a valuable domestic enterprise in which women were key.

-Suzanne Karr Schmidt

Image 4: Sebastian Brant, Scholar in Stultifera navis, 1506.

A true post-classical European invention, reading spectacles were commonly used in the West by the fifteenth century. Yet lens technology was also criticized for making sight unreliable. Soon, the popular illustrated narrative poem Ship of Fools, (first published 1494), adopted glasses to satirize human folly. This educated fool wears oversized spectacles, a mockery linking vision to the acquisition of knowledge. Indeed, this four-eyed scholar with a jester’s cap dusts his books instead of reading them.

-Sandra Racek

Questions to Consider:

- The innovations represented here all facilitate the transformation of something. What is being changed or produced? What are some modern inventions which facilitate transformations?

- In the Renaissance, silk production, unlike many of the other trades shown in these images, was marketed as an enterprise suitable for women. Compare the “Silkhouse” shown in the frontispiece to Vida’s The Silkworm to the distillery shown by Stradanus. Who is working in each place? What do the buildings’ interiors look like, and what can we see in the background? Overall, how would you describe the two industries based on this image?

- Compare and contrast the figures wearing glasses in the Stradanus Distillation print and the Brant book.

Beyond the Nova Reperta

Publications describing, illustrating, and praising innovation flourished into the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and further emphasized the collective nature of innovation. Francis Bacon’s philosophical Novum organum (1620) discusses many of the inventions highlighted in the Nova Reperta—including silk, sugar, and the compass—and calls for collaborative experimentation. Galileo, a colleague of Stradanus’s patron, Luigi Alamanni, knew well the role of scholarly exchange to promote new scientific thought. His controversial Dialogo (1632), with its renowned frontispiece representing scientists in conversation, shifted the focus from the globe to the skies. Bate’s Mysteries of Nature and Art provides an example of an early modern illustrated book that includes recipes and instructions for innovative devices and activities.

Image 1: Francis Bacon, Title Page of Novum organum, 1620.

English statesman and inventor of the scientific method, Bacon singled out printing, gunpowder, and the magnet for their contributions to literature, warfare, and navigation. In his New Organon, a reference to Aristotle’s work on logic, Bacon considered these inventions hopeful signs for continued progress. The title page depicts ships approaching two columns representing the old learning described in the scroll below: “Many will pass through, [and] knowledge will be increased.”

-Christopher Fletcher

Image 2: Galileo Galilei (author) and Stefano Della Bella (engraver), Title Page of Dialogo, 1632.

A colleague of Alamanni and Stradanus, Galileo Galilei adamantly defended the Copernican planetary model. His Dialogue presents a conversation between three fictional philosophers discussing the theory that the earth and other planets orbit the sun. The pope banned the book and summoned Galileo to Rome to stand trial before the Inquisition. The Medici sponsored his Dialogue––the frontispiece features their crown and coat-of-arms above the debating philosophers, outdated armillary sphere in hand.

-Olivia Dill

Image 3: John Bate, The Mysteries of Nature and Art, 1635.

Though not much is known about John Bate, The Mysteries of Nature and Art speaks to his experiential interest in a broad array of technological, scientific, artistic, and medicinal matters. The title page includes a variety of creations from the main text, both entertaining (like the flying dragons at the top middle) and practical. The book’s various editions demonstrate the evolution of technical how-to guides before the more rationalized works of the eighteenth century.

-Ikumi Crocoll

Questions to Consider:

- Ships are depicted in the frontispieces to Bacon’s work (between the two columns) and Galileo’s text (in the background, behind the philosophers). Thinking back to the other prints containing ships, what do you think these vessels symbolize, and what are they meant to tell us about the texts they preface?

- The Medici coat-of-arms consisted of five round spheres and can be found above the philosophers in the Galileo frontispiece. What does this tell us about Galileo’s relationship to the Medici family? About the Medici’s role in Renaissance art and science?

- What innovations can you identify in Bate’s frontispiece?

Today’s Nova Reperta

The incessant listing of new technologies that became common by the 1580s continued in the subsequent centuries. Following books emphasized the collective nature of innovation as positive progress. As a result, list culture still thrives today.

Selected Sources

Dackerman, Susan, editor. Prints and the Pursuit of Knowledge in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Art Museums, 2011.

Grafton, Anthony. New Worlds, Ancient Texts: The Power of Tradition and the Shock of Discovery. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1995.

Long, Pamela O. Artisan/Practioners and the Rise of New Sciences, 1400-1600. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press, 2011.v

Markey, Lia, editor. Renaissance Invention: Stradanus’s Nova Reperta. Chicago: Northwestern University Press, 2020.

Smith, Pamela H. The Body of the Artisan: Art and Experience in the Scientific Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.