Introduction

Students in the United States know Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn as a fixture in the American literary canon and a staple of high school reading lists. But this status has not gone uncontested: the novel has been the subject of controversy ever since it was first published in 1884. While early reviewers sometimes praised the work for its social realism and its ability to promote the virtues of “manliness and self-sacrifice,” many others found much to criticize. The San Francisco Examiner charged Huckleberry Finn with an “utter absence of truth and being unlike anything that ever existed in the earth.” Other reviewers bemoaned Huck’s lack of a moral center, his inadequacy as a role model for children, and the bad company he keeps. (Twain himself insisted that the story had no moral.)

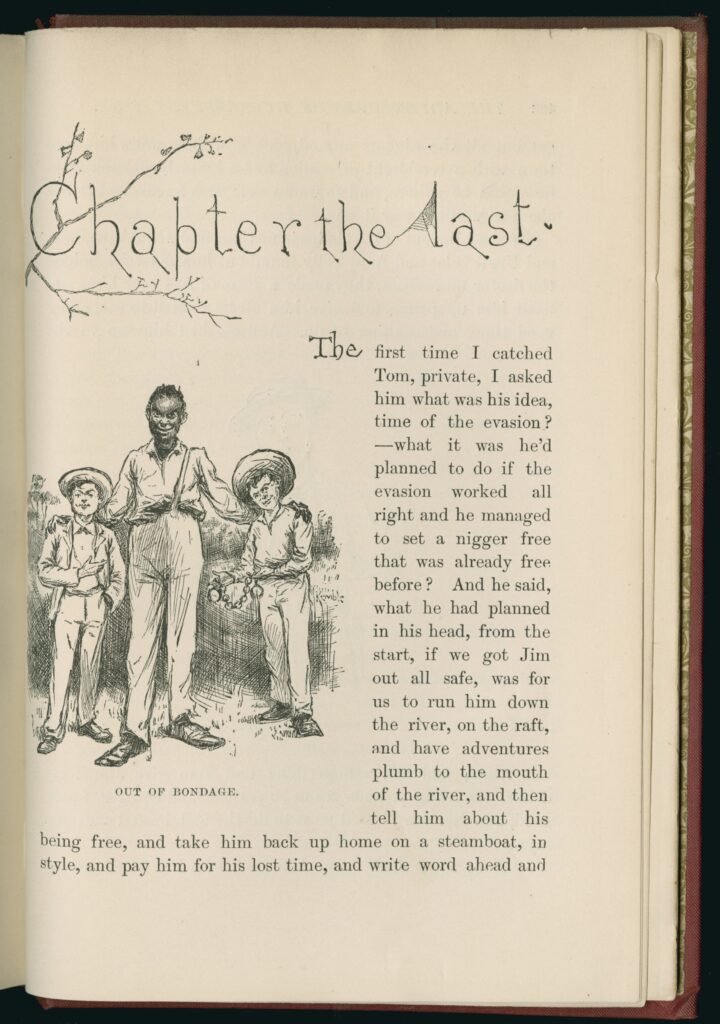

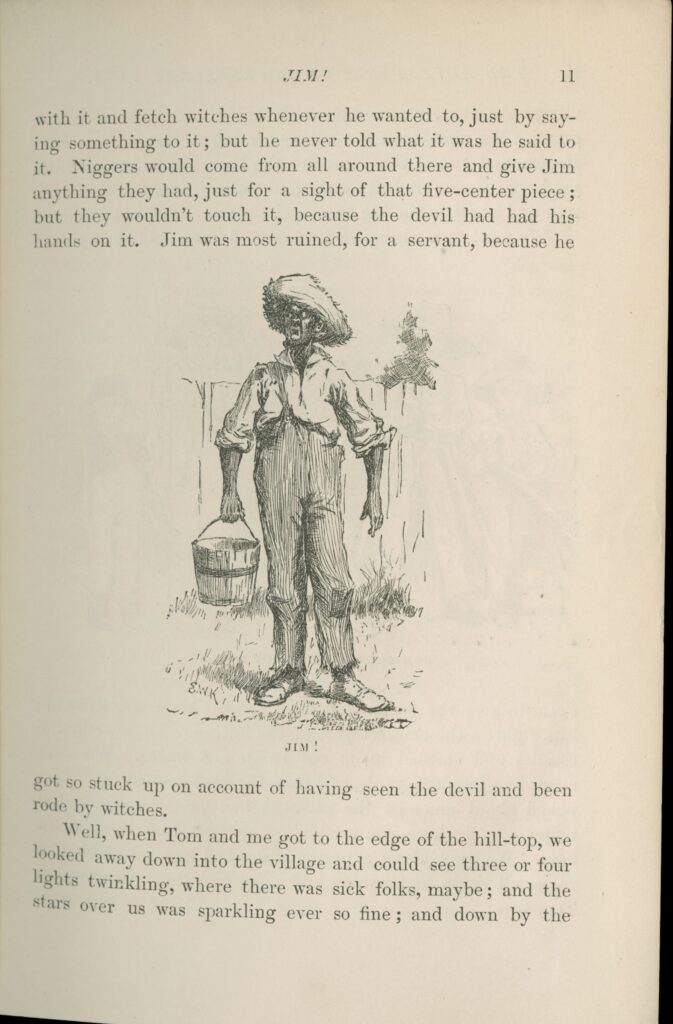

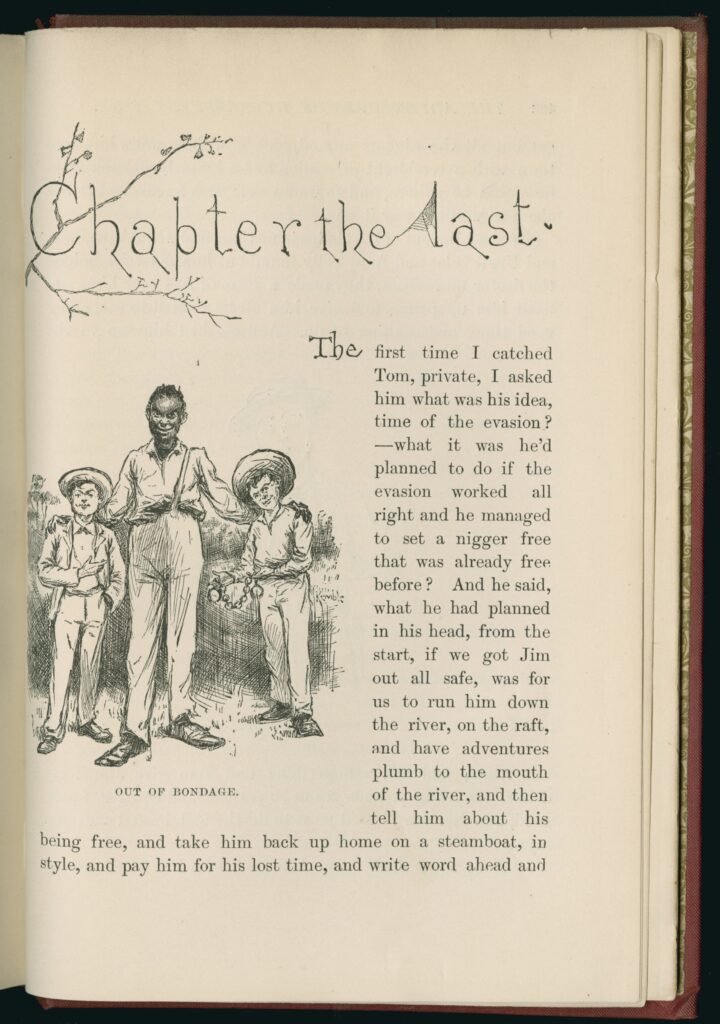

These concerns with the novel’s moral influence have since given way to impassioned debate over its treatment of race. Twain wrote the novel in the first-person voice of its main character, Huckleberry Finn. The text reproduces the vernacular, or spoken, language of people who lived along the Mississippi River in the mid-nineteenth century. The characters frequently use the word “nigger.” Furthermore, though Huck befriends the fugitive slave Jim and tries to help him escape down the river, Jim is often the butt of jokes, outwitted by Huck and Tom Sawyer. Some recent critics have argued that the novel reinforces racist stereotypes and should be removed from the public school curriculum. In 1976 New Trier High School in Winnetka, Illinois, struck the book from its curriculum in response to protests from parents and students who were offended by the novel’s language. Defenders of Huckleberry Finn respond that the book, in fact, challenges the institution of slavery and that its language accurately represents regional speech at the time. In her introduction to a recent edition, the Nobel Prize–winning author Toni Morrison writes that Huckleberry Finn is remarkable for “its ability to transform its contradictions into fruitful complexities and to seem to be deliberately cooperating in the controversy it has excited.”

Why has Adventures of Huckleberry Finn remained required reading in classrooms across the country? How did people in Twain’s own time respond to Huckleberry Finn? What cultural, literary, and historical influences shaped Huck and Jim and the characters they encounter on their journey down the Mississippi? Is it possible for a book to be both racist and a critique of racism at the same time?

The following collection of documents develops the historical and cultural context for this complex work. It brings together excerpts from novels and newspapers as well as paintings, sketches, and other historical documents to help readers understand the social world in which Twain wrote and which he wrote about.

Please consider the following questions as you review the documents:

- What images and ideas from popular culture helped to shape the characters that Twain created?

- Why was Huckleberry Finn such a popular book when it was published and why do we still read it today?

- How did ideas about and representations of African Americans change in the years before and after the Civil War?

“This lawless, mysterious, wonderful Mississippi”

A reviewer in the Hartford Courant, writing about Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, said no one had better captured “this lawless, mysterious, wonderful Mississippi” than Mark Twain. Twain cemented the Mississippi River in the American imagination as a site of adventure, romance, and nostalgia, but he was not the first to depict life on the river. The Mississippi was the dividing line between the early eastern United States and the new western territory that formed the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. Though the river became a booming commercial thoroughfare with the introduction of steamboats in the 1810s and ’20s, it retained its status as a dividing line between eastern civilization and western wilderness. Life on the Mississippi had a reputation as wild and unconstrained by the strict moral and social norms that shaped society in the East.

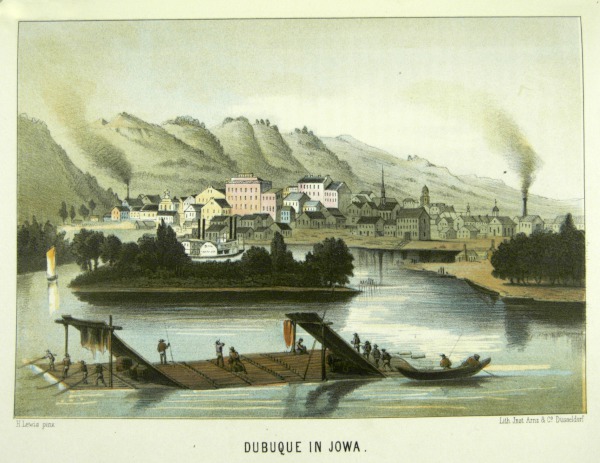

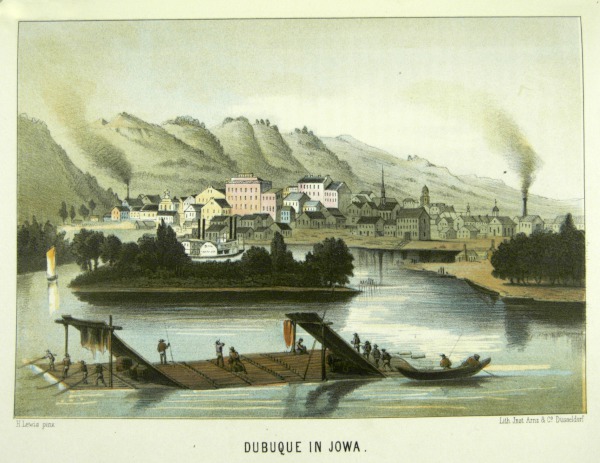

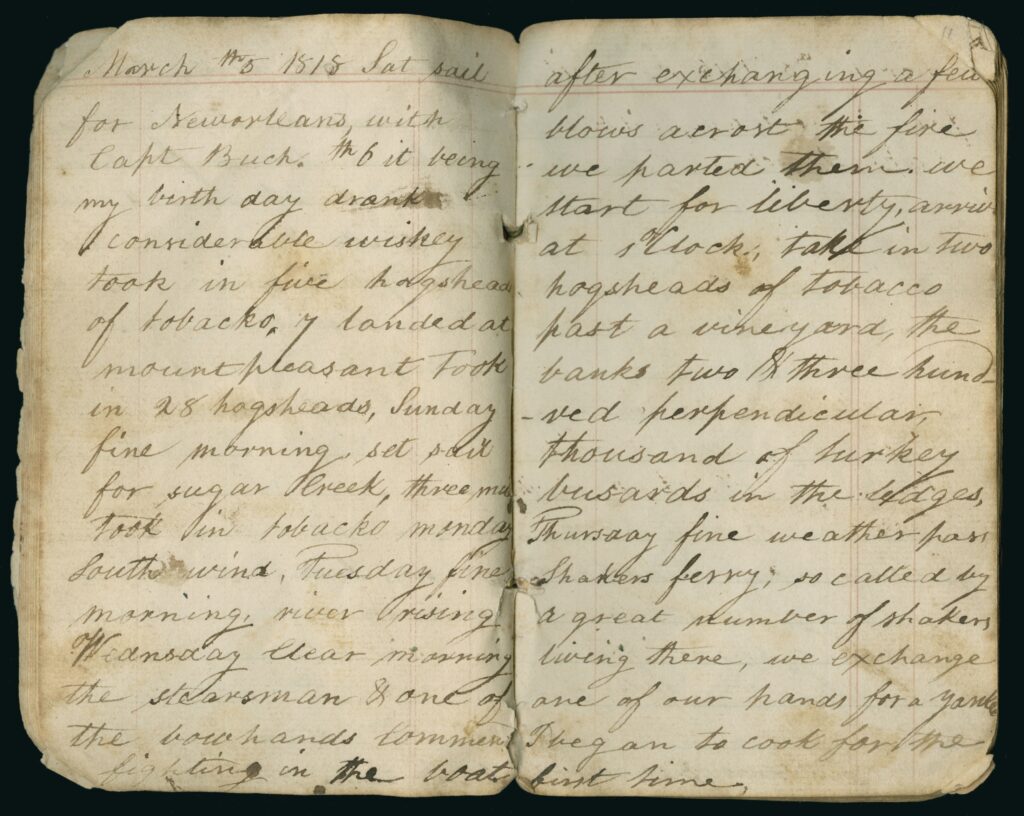

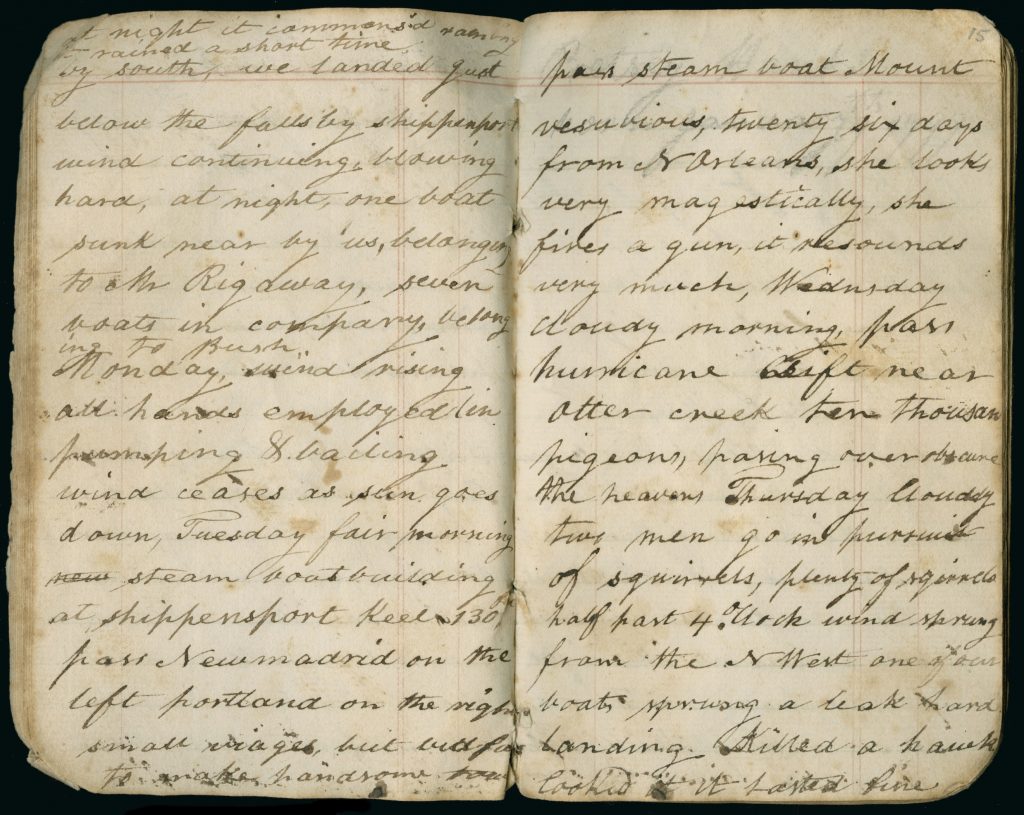

The items in this section offer differing views of the Mississippi in the early part of the nineteenth century. Henry Lewis’s view of Dubuque from the river was part of a giant panorama of the Mississippi that traveled around the United States and Europe in the 1840s and ’50s. Panoramas were the 3D IMAX movies of their day—huge, circular paintings that promised to make the audience feel like they were part of the image. The massive crowds that flocked to see Lewis’s painting would have felt like they were floating down the mighty Mississippi. A diary of a trip from Pittsburgh to New Orleans written in the winter of 1817–1818 follows the route of the steamboats that opened the river up to trade. Though the boats could be a bit rustic, occasionally tipping passengers into the water, by the 1840s some steamboats were offering luxury sightseeing excursions down the river.

Selection: Diary of a Journey Down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers in 1817, from Pittsburgh to New Orleans (1817)

Questions to Consider:

- Imagine you are a German visitor looking at Henry Lewis’s panorama on display in Berlin in the 1850s. What would you think about America from the image? How would you describe the Mississippi?

- How does the account of a voyage down the Mississippi compare to Huck and Jim’s journey? What sort of people does the author encounter on his journey and how do his descriptions differ from Twain’s?

Images of Race in Antebellum America

Twain’s ideas about race didn’t develop in a vacuum. He and his readers would have encountered various images of African Americans in novels, newspapers, magazines, and on stage. Two of the most prominent sources for white understandings of African American life in the mid-nineteenth century were the blackface minstrel show and the abolitionist novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

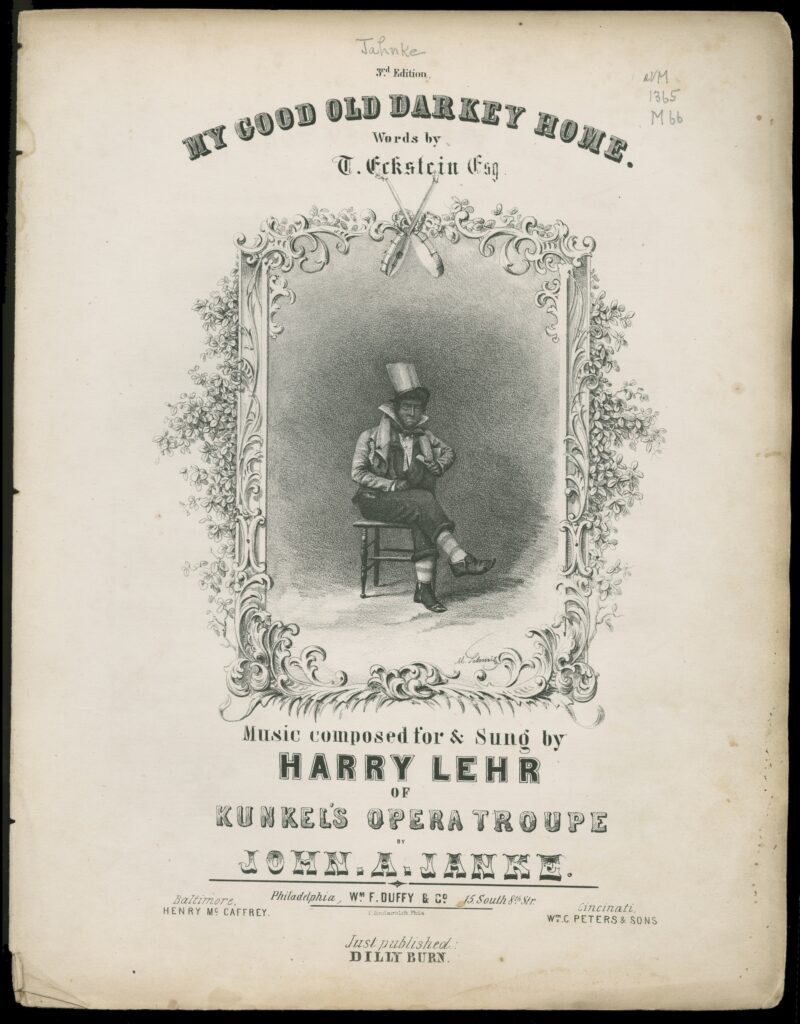

In minstrel shows, white performers would use a burnt cork to darken their faces and hands and mimic black dialect, dances, and songs. Minstrel shows were massively popular among white audiences in the United States and in Great Britain across the political spectrum. Scholars have recently pointed out that in the nineteenth century, minstrel shows and blackface were complex cultural forms. They conveyed a variety of messages to their audiences, and racism was only one of them. Abolitionists put on blackface shows to depict the horrors of slavery. Proslavery advocates pointed to the foolish behavior of white minstrel performers as proof that slaves weren’t intelligent enough to look after themselves. Historian Eric Lott contends that minstrel performance provided a way for audiences (especially working-class audiences) and performers to express their own attraction to African American culture by appropriating parts of that culture. Minstrel acts poked fun at elites and allowed the white working class to make political statements about their own grievances, even as they demeaned African Americans. Later in the nineteenth century there is evidence that African American performers started their own minstrel troupes, complete with cork-blackened faces.

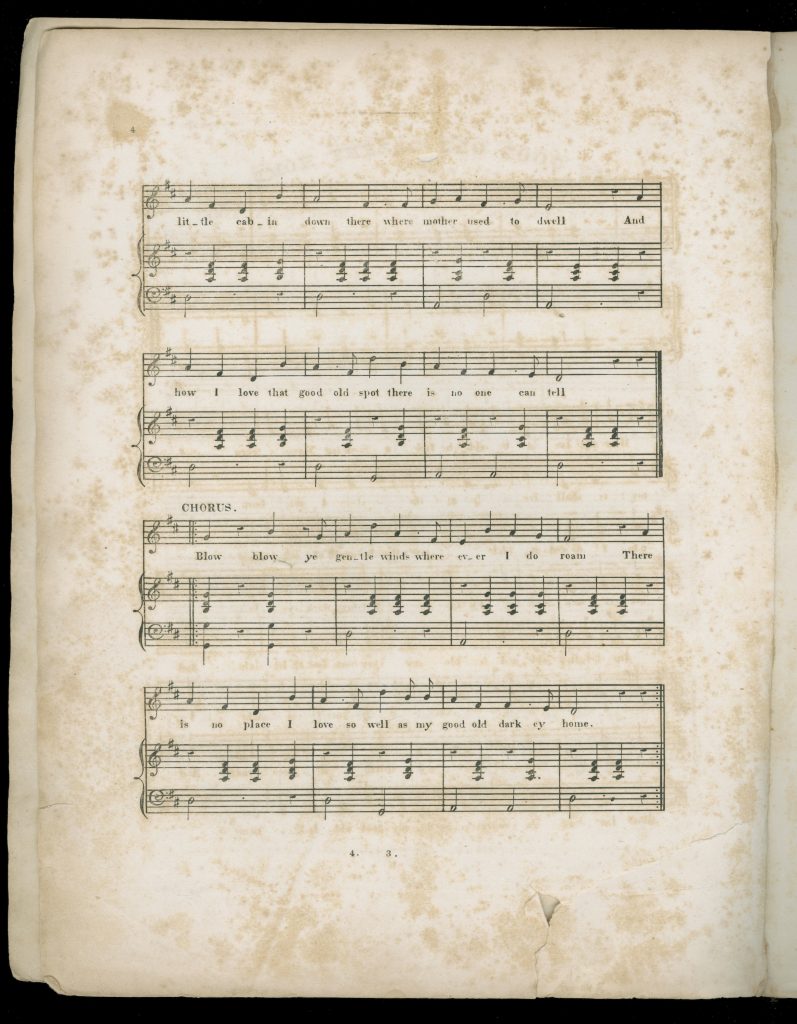

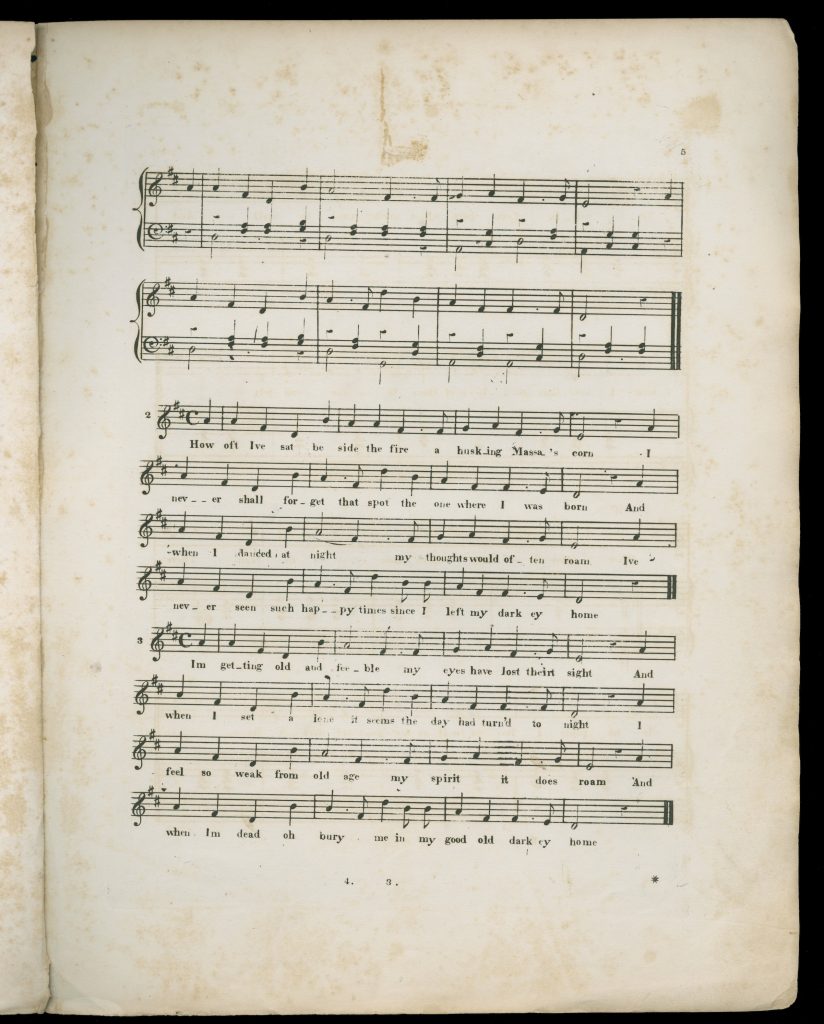

Selection: John A, Janke, “My Good Old Darkey Home” (1854)

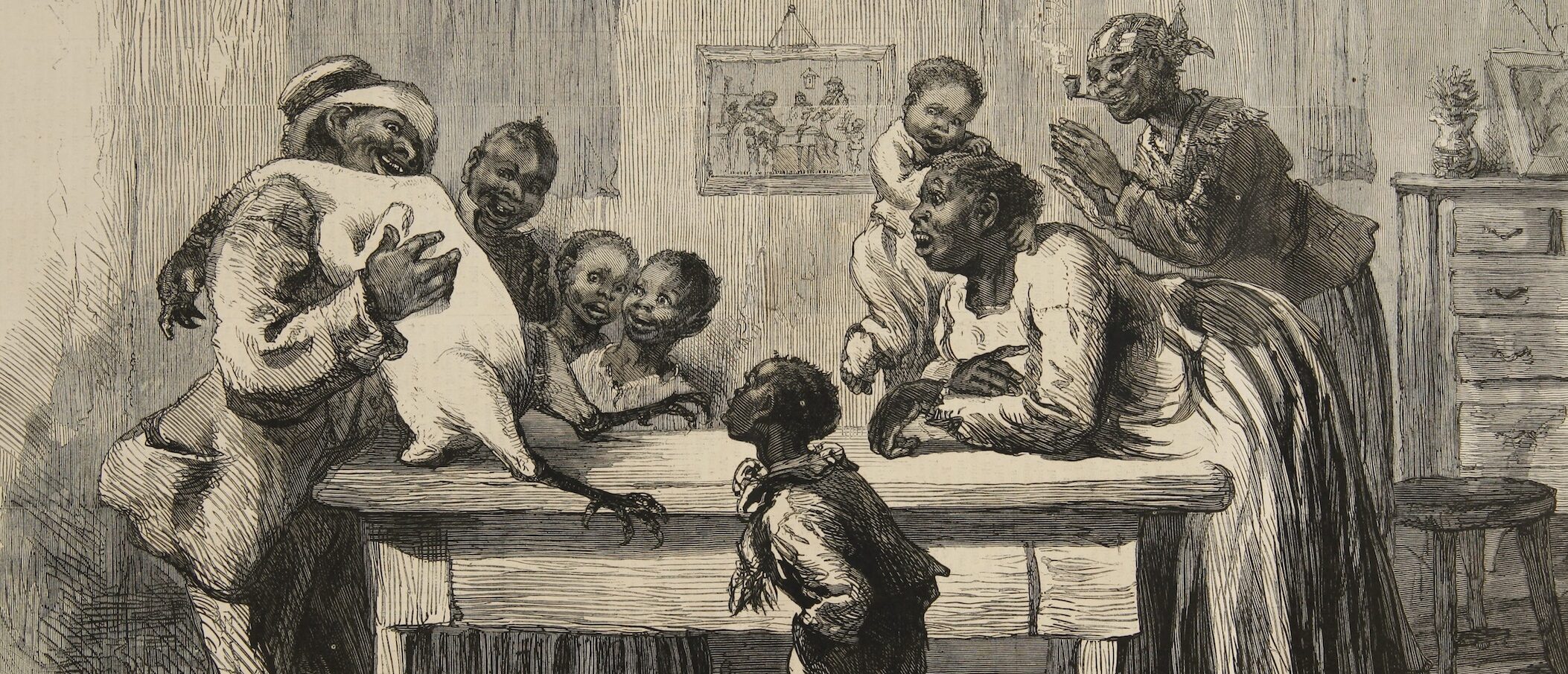

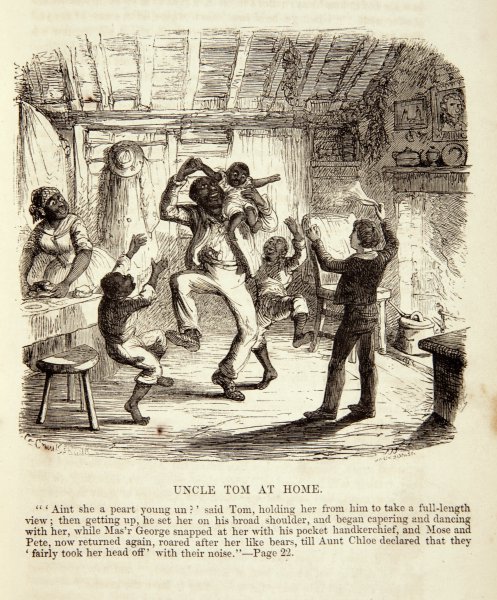

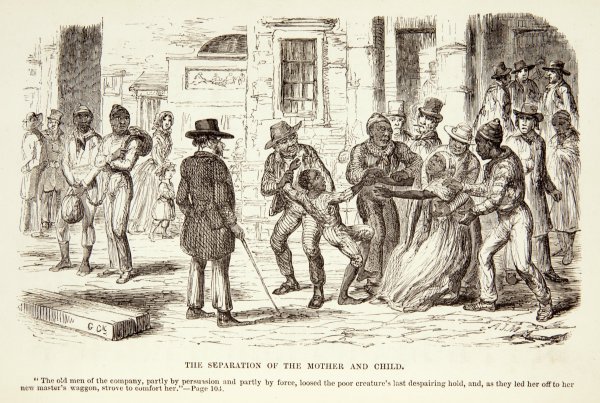

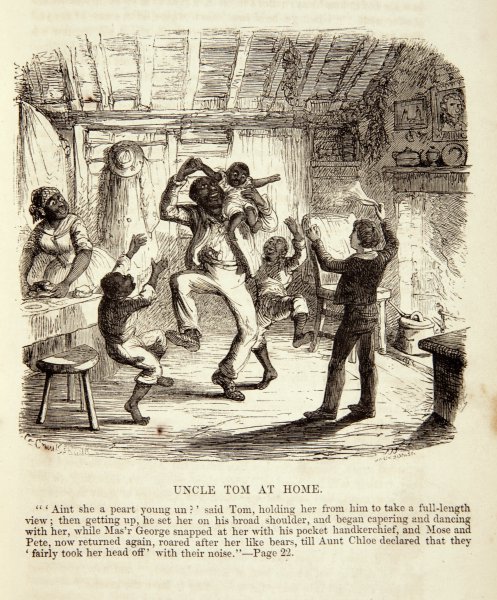

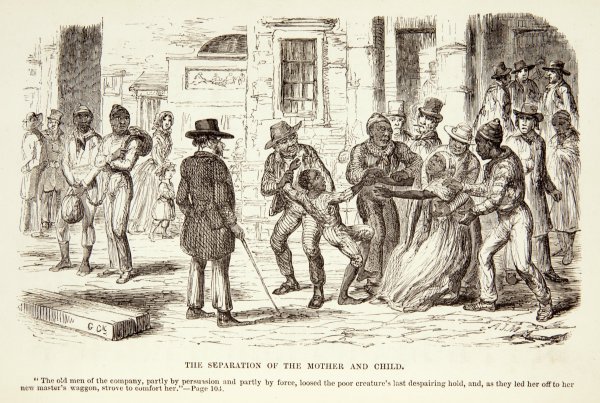

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin was a publishing sensation and a powerful force for abolition. The novel inspired antislavery sentiment in its readers, famously moving even Queen Victoria to tears, through its depiction of the suffering that slaves endured when they were sold away from family and friends, abused by cruel overseers, or attempting to escape. George Cruikshank’s illustrations, two of which appear in this section, appeared in the first London edition of the novel and emphasize both comic and dramatic elements.

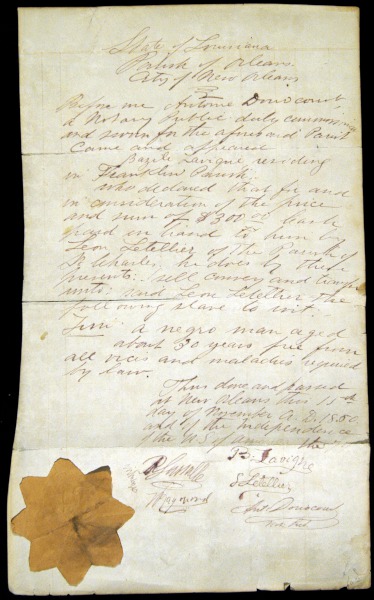

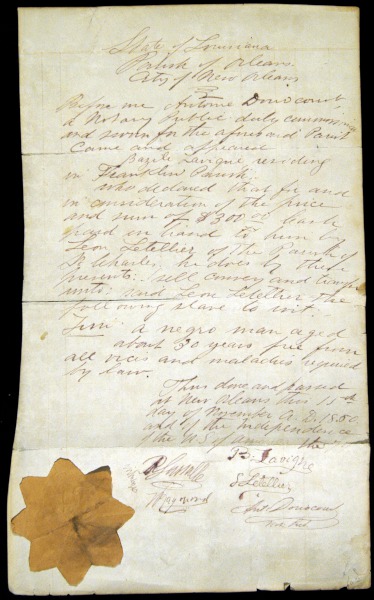

Finally, a bill of sale for a slave known only as “Jim” underlines the dehumanizing nature of slavery. The sale is couched in the legal language of trade and five white men witness the transaction, but the document leaves no trace of who Jim was or what this sale meant for him and the people he loved. Historian Walter Johnson estimates that two million people were sold in the United States between the Revolution and the Civil War.

Questions to Consider:

- Compare the two illustrations from Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Do you think these images offer historically accurate representations of slavery? Why or why not?

- What information does the bill of slave include? How does Cruikshank’s illustration of a slave auction compare with the representation of the transaction given in the bill of sale?

- Examine the cover illustration and lyrics to My Good Old Darkey Home. How does the song portray its African American narrator and the experience of slavery? Why do you think music like this appealed to white audiences after the Civil War? Can you think of any present-day parallels to the minstrel show?

- Compare the minstrel sheet music to the Uncle Tom’s Cabin illustrations. In what ways are these images similar and in what ways are they different? How do you see Twain responding to these popular sources in his depiction of Jim and other black characters?

Race Relations after the Civil War

By the time Twain was writing Huckleberry Finn in the early 1880s, the United States was redefining itself as a nation postwar and postslavery. Reconstruction policies, begun by Abraham Lincoln and continued by the United States Congress after the Civil War, aimed to reintegrate the Southern states into the Union politically and to provide support for freed slaves. But antagonism between North and South, Southern bitterness at defeat, and racism on both sides meant that early gains in political representation and equality for African Americans were quickly suppressed. Historian David Blight argues that attempts to heal the breach created by the Civil War came at the expense of African American rights. In both North and South, many white Americans felt a great deal of nostalgia for the decades before the war. The horrors of slavery disappeared from the nation’s history books, replaced by images of contented slaves and affectionate masters. The Democratic Party, historically allied with the South, violently contested the presidential election of 1876, resorting to mob violence to suppress black voter turnout in the South. Though the Democratic candidate ultimately lost the electoral vote, the election marked the end of Reconstruction Era policies aimed at reuniting the country politically.

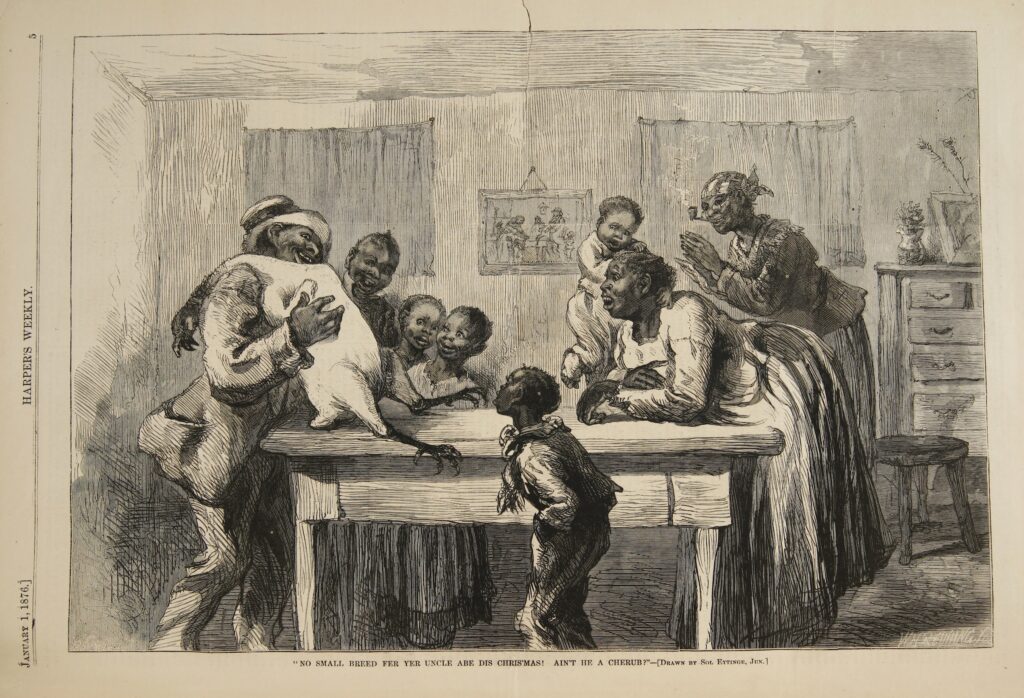

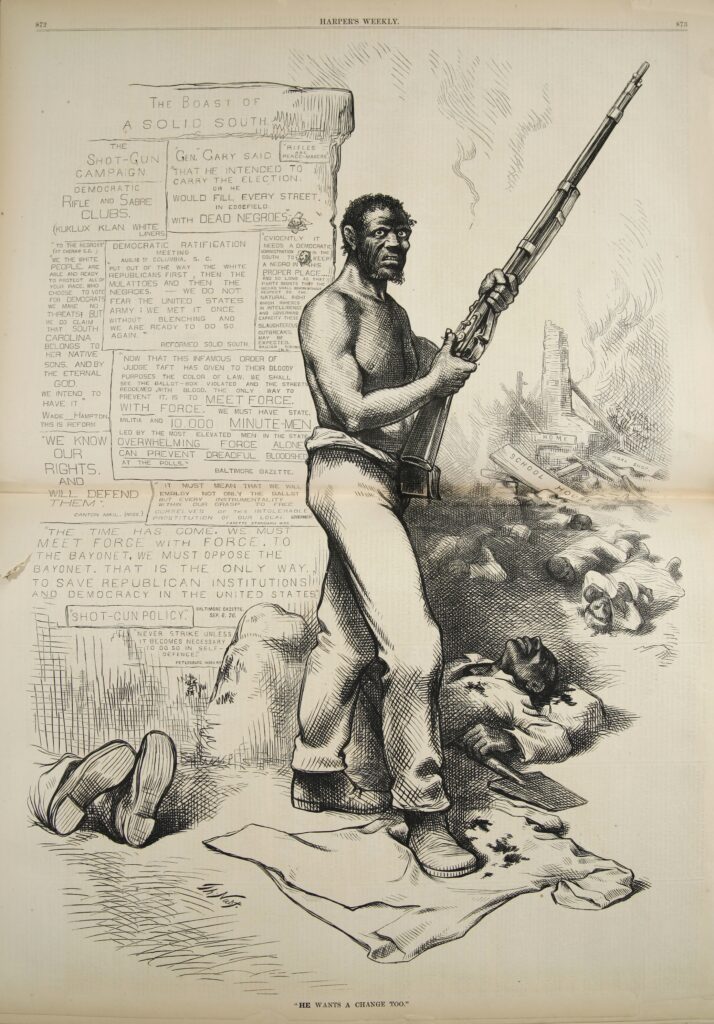

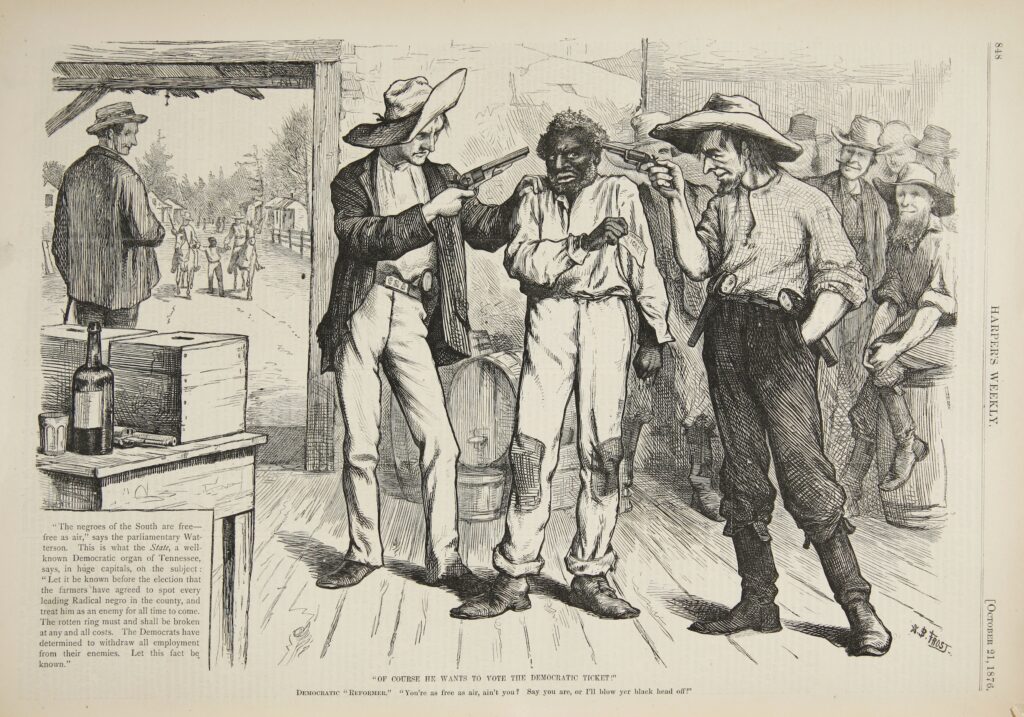

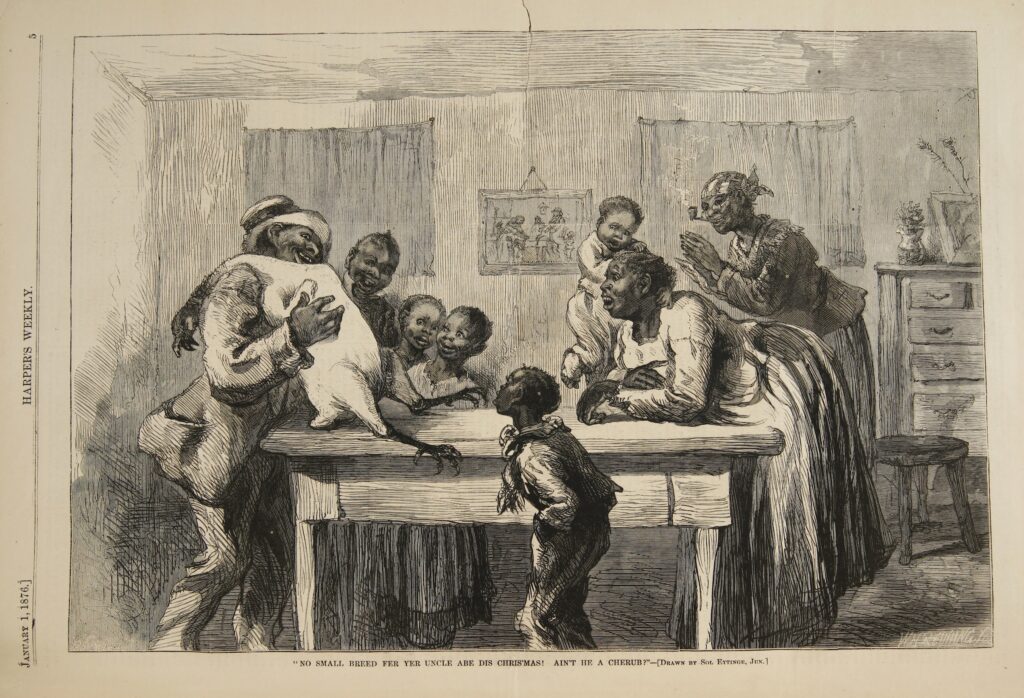

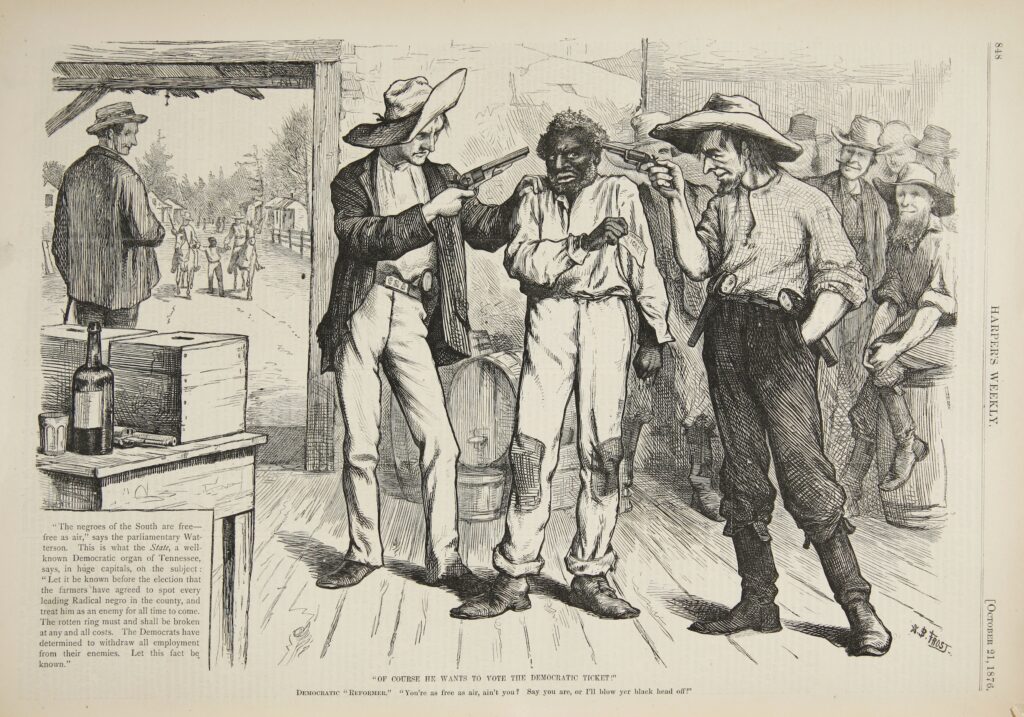

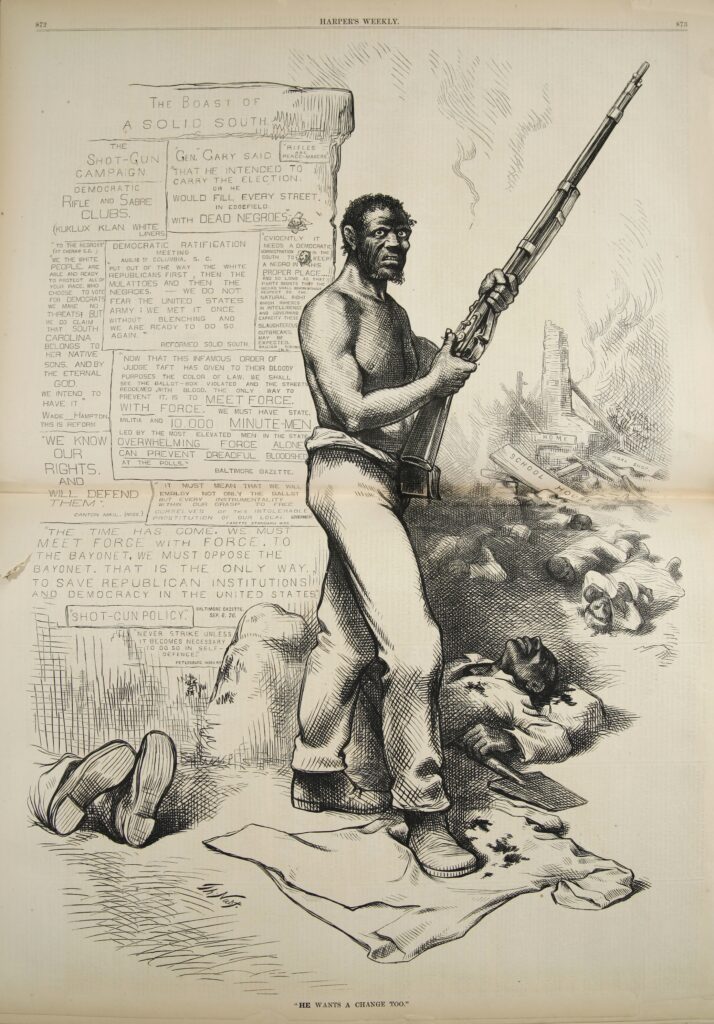

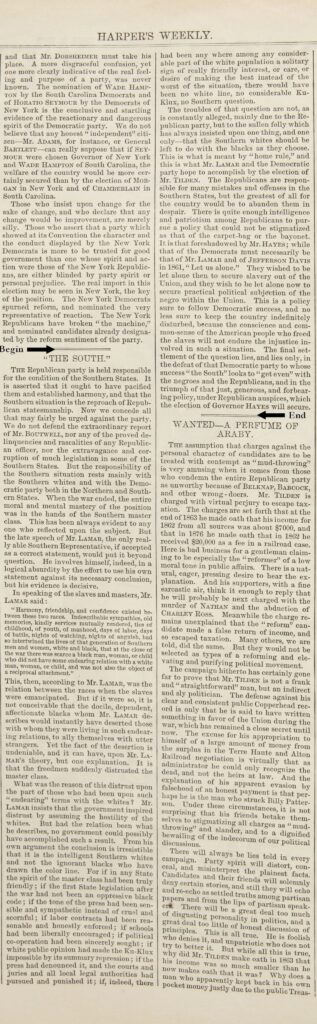

Amid this political strife, representations of African American life varied greatly. Within the space of one year, depictions in New York–based Harper’s Weekly veered from a cheery Christmas scene to a terrifying image of a black voter held at gunpoint and an African American man seeming to vow revenge on the mob that killed his family. Illustrator Sol Eytinge borrowed from his background illustrating American editions of Charles Dickens to show a black family gathered excitedly around a Christmas goose. A.B. Frost and Thomas Nast depict the consequences of mob violence against African Americans in their cartoons. In a Harper’s editorial on the South and the 1876 election, at left below, Mississippi Representative Lucius Lamar is quoted on prewar race relations.

Questions to Consider:

- How do the Harper’s Weekly illustrations and article portray race relations in the South in 1876? Are they critical of conditions in the South? Identify evidence to support your interpretation.

- Describe how Eytinge, Frost, and Nast depict African Americans in their illustrations. Are the images caricatured (comically exaggerated) or realistic? What messages are the illustrators trying to convey to their audience?

- Do these postwar depictions of African Americans and, specifically, families differ from the prewar illustrations presented above?

- How might racial and regional tensions during Reconstruction and the 1876 election affect Twain’s depictions of African American characters?

Mark Twain and Race

Mark Twain grew up in a slave state and said in his autobiography that, as a child, he “was not aware there was anything wrong” with slavery. Twain came to see plenty wrong with the institution as he grew into adulthood, and he published a variety of articles, sketches, and novels criticizing slavery throughout his career. Twain’s views on race are less clear. In his essay “Only a Nigger,” published in his newspaper the Buffalo Express, Twain denounces lynching and rejects justifications for mob violence. But Twain revealed complicated and contradictory ideas about race and inheritance in his characterization of African Americans in The Tragedy of Pudd’nhead Wilson and the Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins.

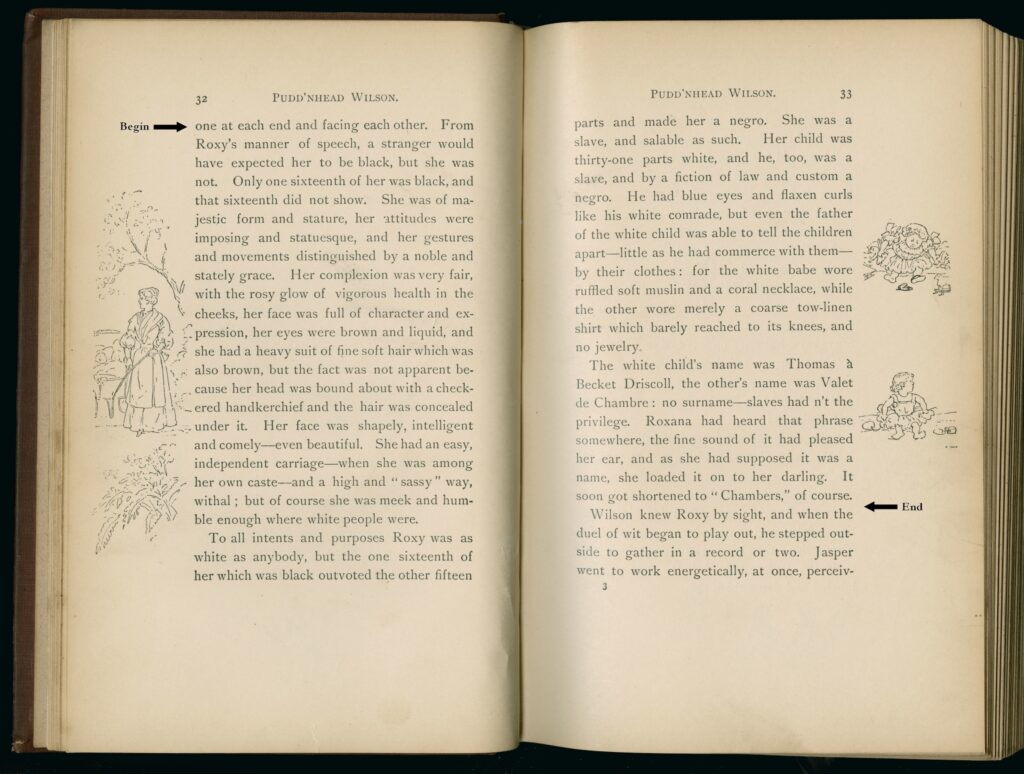

Selection: The Tragedy of Pudd’nhead Wilson and the Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins, 32-33, 44-46 (1894)

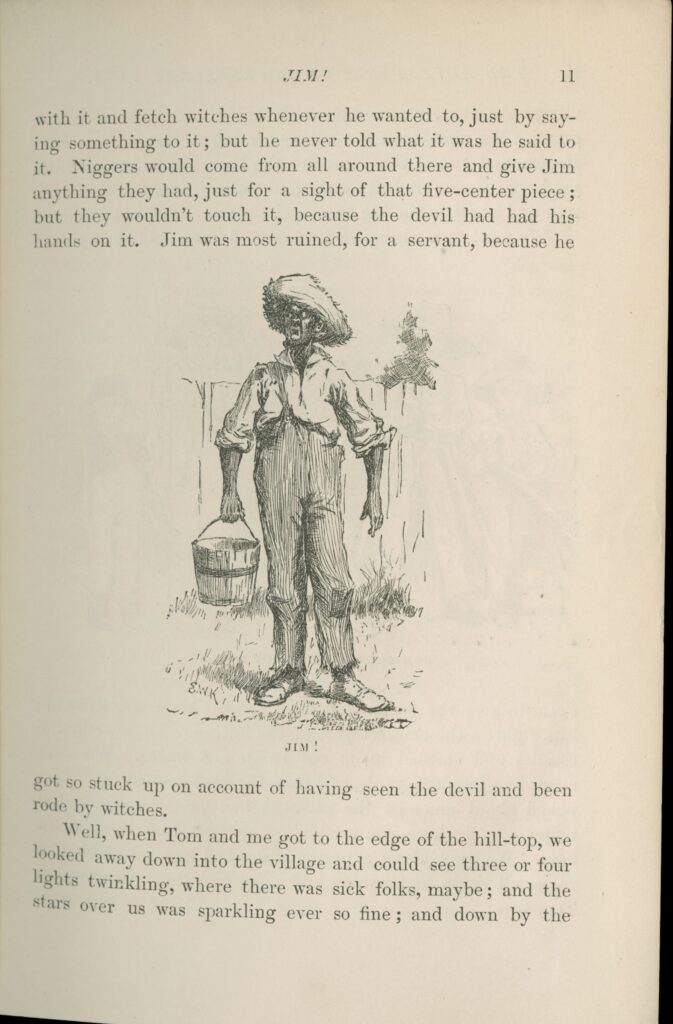

Twain’s Pudd’nhead Wilson is a humorous novel about a tragic situation. This excerpt shows how empathy and racial stereotyping can be bound up in one character, the figure of Roxy, a slave woman faced with the horrible prospect of having her own child sold away from her. Where Harriet Beecher Stowe used a similar scene to evoke sympathy in her readers, Twain plays Roxy’s dilemma mostly for laughs. Two illustrations from the first edition of Huckleberry Finn, pictured in the Introduction, reveal how nineteenth-century readers might have imagined Huck and Jim. Illustrator Edward Kemble used a young white boy named Cort as a model for all the characters in the book, including Huck, Jim, Tom Sawyer, and Aunt Sally. Cort dressed as and mimicked black and female characters when he posed for Kemble, in an echo of minstrel performance.

Questions to Consider:

- How do the images of Jim as a slave and Jim as a free man differ? What do these images have in common with the other illustrations of African Americans presented here?

- How does Twain describe Roxy? Why do you think he emphasizes the contrast between her black speech and her white appearance? Do you think the contrast works to challenge assumptions about race and identity or to reinforce them?

- What is the source of the humor in the passage in which Roxy decides to swap the babies? Who or what is being poked fun at in this scene? Do you find that Twain’s humor works as a form of social critique?

- How do the illustrations in Pudd’nhead Wilson affect the meaning of the text?

Huck Finn and American Identity

The writers Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, and Eugene O’Neill have all claimed that Mark Twain was the first great American writer and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn the first great American novel. Recent critics suggest that the novel may have been especially appealing to readers at the turn of the century, a time when Americans began to worry that city life and office jobs were weakening American men and boys. Anxieties about urbanization, immigration, and American character made a hero like Huck—independent, rebellious, and adventurous—all the more attractive to a reading public eager to see in him a reflection of their own best qualities.

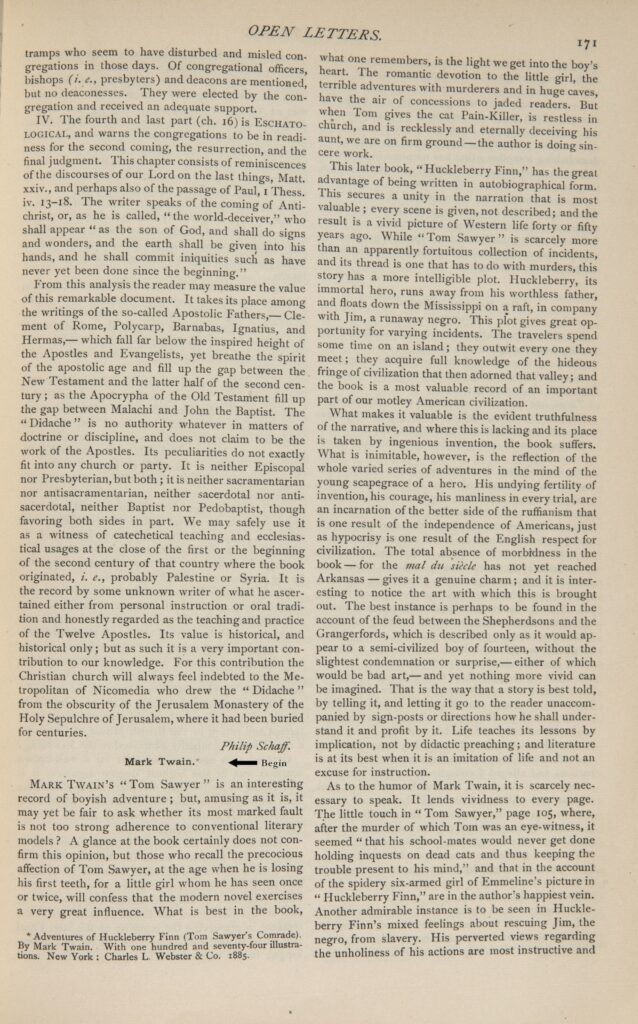

Huckleberry Finn’s first chapters were published in The Century, a magazine that championed American nationalism. The following year, the magazine published an admiring review of the novel, included below.

Selection: T. S. Perry, “Mark Twain” in The Century (1885)

Questions to Consider:

- How does T. S. Perry describe Huckleberry Finn in his 1885 essay? Why does he praise the novel?

- Is Huck an admirable character? Why do you think readers have found him so appealing?

- Why do you think so many readers have described Adventures of Huckleberry Finn as a quintessentially American novel? What features of the story and the character of Huck demonstrate qualities that we associate—or would like to associate—with national character?

Further Reading

David Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory, 2001.

Shelley Fisher Fishkin, The Mark Twain Anthology: Great Writers on his Life and Work, 2010.

Walter E. Johnson, Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market, 1999.

Eric Lott, Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working-Class, 1993.

Mark Twain, Autobiography of Mark Twain, Vols. 1 and 2, 2010, 2013.