Introduction

The Civil War has long served as a powerful, organizing division in American literary history. As critics Christopher Hager and Cody Marrs recently noted, 1865 has provided a nearly unquestioned periodization for students, teachers, and scholars of American literature. “American Literature to 1865,” “American Literature after 1865.” These are the standard rubrics for countless courses, anthologies, and critical works. Yet, Hager and Marrs ask, what if “as an event in literary history [the Civil War] is both a rupture and an occasion for extension?” Many celebrated writers of the 1850s (Herman Melville, Walt Whitman, Frederick Douglass) continued to produce important works during and after the war. Realism, a literary movement associated with the end of the nineteenth century, has significant precedents in antebellum literature. How would the study of nineteenth-century American literature change if we explored these continuities?

Americans wrote, published, and read a great deal about the war as it was going on and in the years that immediately followed. This literature invested the violence and trauma of the Civil War with meaning.

Drawing a firm line at 1865 may have had another effect as well: encouraging us to look away from literature on the war itself and on its immediate aftermath. The traditional American literary canon often skips from American Renaissance figures of the 1850s to late-century realists like Henry James and Edith Wharton. Yet Americans wrote, published, and read a great deal about the war as it was going on and in the years that immediately followed. Civil War literary culture included a wide variety of both popular and highbrow forms, from news of the frontlines to accounts of emancipation to patriotic songs and poems as well as countless works of fiction. This literature invested the violence and trauma of the Civil War with meaning. It helped Americans on both sides of the conflict make sense of the war and its effects.

The collection of texts below draws on a number of these genres to explore the ways that literary culture shaped the meaning of the war for people who lived through it. This collection is based on the 2013 Newberry Library and Terra Foundation for American Art exhibition Home Front: Daily Life in the Civil War North, curated by Peter John Brownlee and Daniel Greene. It complements another Digital Collection for the Classroom: Home Front: The Visual Culture of the Civil War North.

Essential Questions

- What literature was published and read during the Civil War?

- How did literature shape the meaning of the war? How did writers and readers turn to literature to make sense of the war itself and of the profound changes it brought to the nation?

- How might reading the literature of the Civil War lead us to think in new ways about American literary history?

Writing the War for the Union I

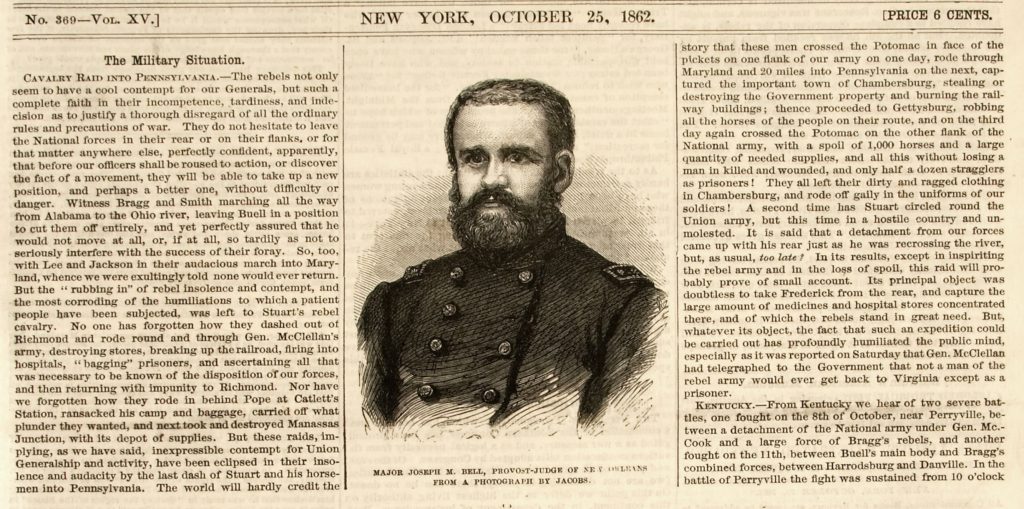

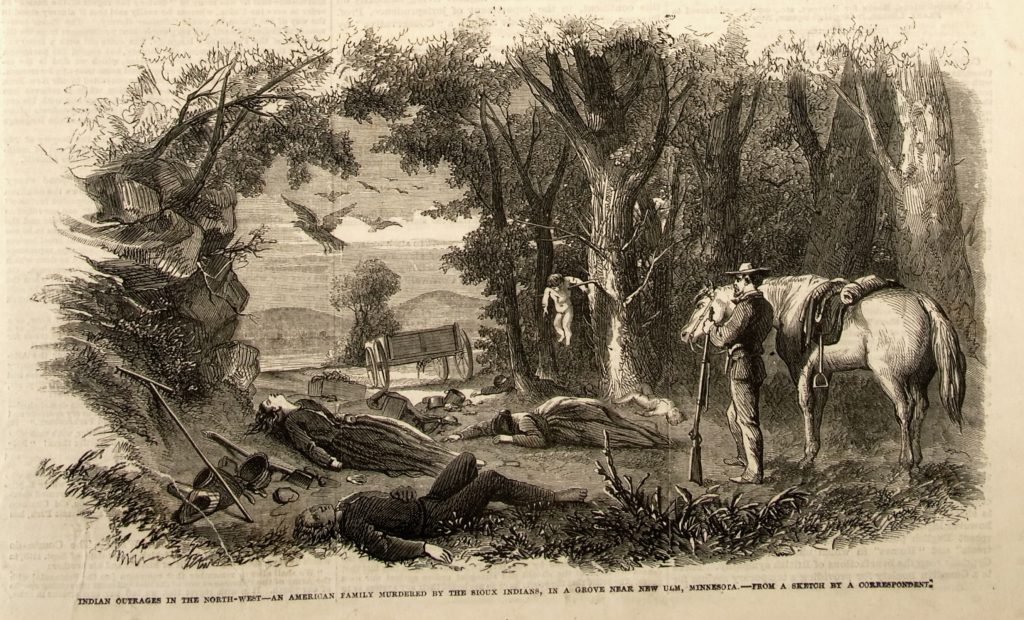

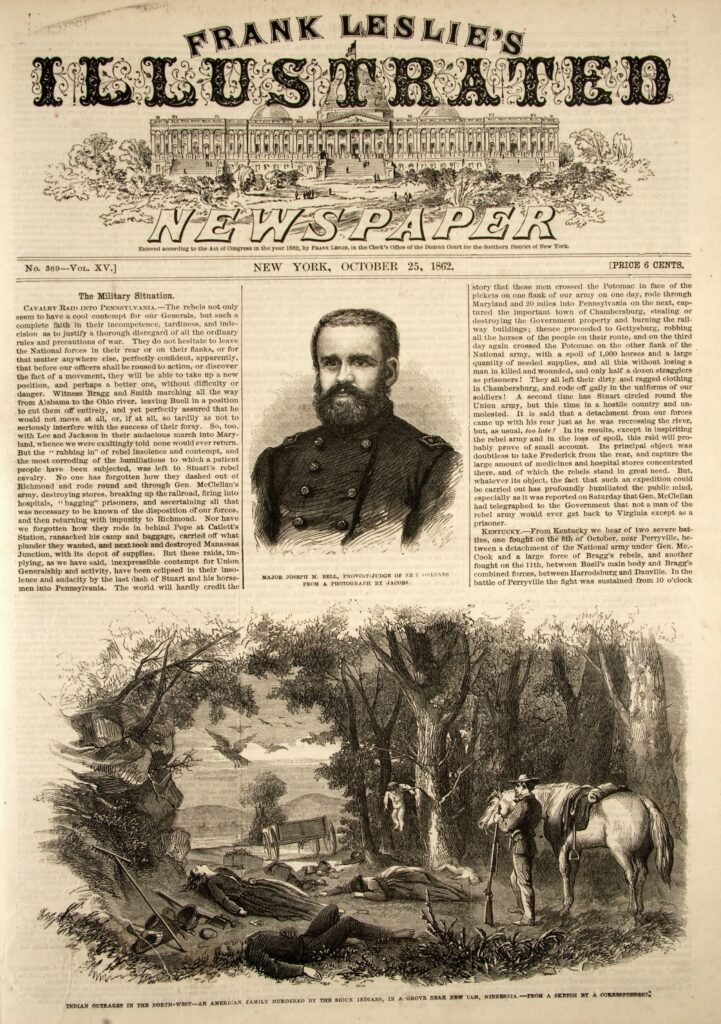

Northerners read about the war through many different kinds of texts, several of which appear here. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper was a popular, New York–based weekly. This cover, dated October 25, 1862, offers a good example of Northern war reporting in its account of Jeb Stuart’s October 10–12 raid on Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. The illustration on the bottom half of the page offers a reminder that the Civil War was not the only war the United States fought that year; it also conducted a war against Dakota (or Sioux) Indians in Minnesota, then considered the Northwest. The Civil War had placed new pressures on Indian Country. Both the Union and the Confederacy laid claim to territory outside the established states. In August of 1862, tensions over land erupted into a war between the Dakota and settlers who were soon joined by the U.S. army. Hundreds of people on both sides of the conflict died. By the end of December, most of the Dakota bands had surrendered. The United States held nearly 400 Dakota warriors prisoner and, on December 26, hanged 38 men in the largest mass execution in U.S. history. Leslie’s presents the illustration here as “a sketch by a correspondent,” but the drawing was probably embellished by a staff artist.

Selection: “The Military Situation,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, details (October 25, 1862)

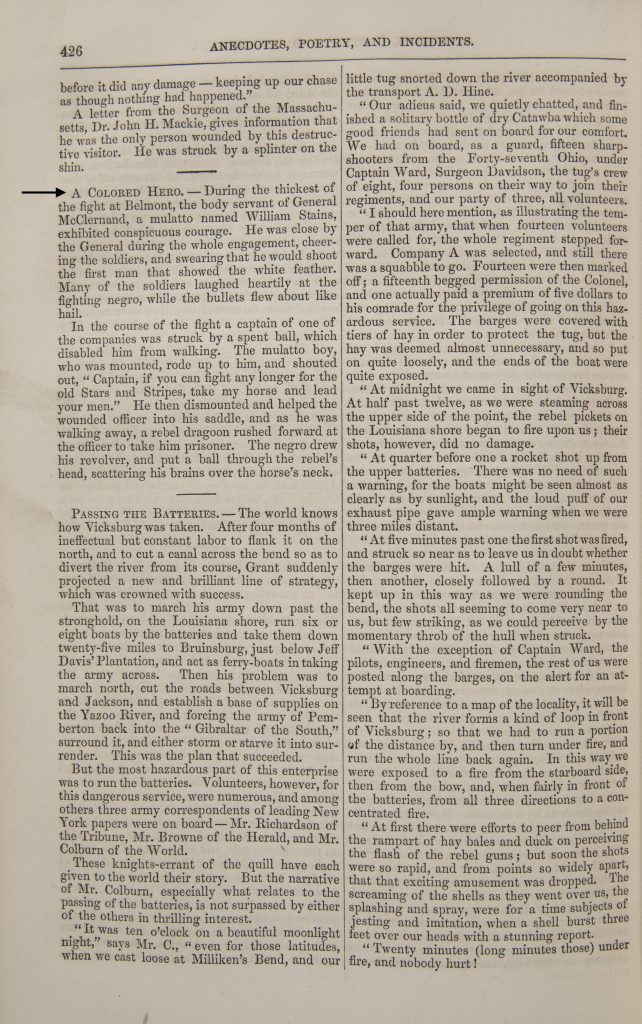

The final source in this section is Frank Moore’s collection of anecdotes and popular poems about the war. Moore was a New York journalist who, in the 1860s, published many compilations of writing related to the war, including a 12-volume history entitled The Rebellion Record. This work opens with Abraham Lincoln’s portrait on the frontispiece.

Selection: Frank Moore, Anecdotes, Poetry and Incidents of the War: North and South, 7-9, 349-350, 426 (1867)

Questions to Consider

- Even if you did not know where Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper was published, would you know which side of the Civil War this journalist was on? How would you know?

- As twenty-first-century readers, we, of course, know who won the Civil War. This October 1862 piece, however, captures a moment when the war’s outcome was far from certain. What are the writer’s criticisms and concerns about the Union’s military strategy?

- Examine the illustration of “Indian Outrages in the Northwest.” What does the illustration depict? How would you characterize the illustration’s style?

- Would you consider either the report on the Chambersburg raid or the “Outrages” illustration examples of objective journalism? What sort of responses might they solicit—considered separately or together—from readers at the time? How do they compare to articles and images in newspapers today?

- How do anecdotes such as “How to Cross a River,” “A Brave Woman,” and “How an Amputation Is Performed” represent the war to Northern readers? What is the tone of these pieces?

- Examine the pieces from Frank Moore’s volume that portray African Americans, “When you is about, we is” and “A Colored Hero.” How are African Americans represented in each of these stories? What do these anecdotes suggest about popular views of African Americans and emancipation among white Northerners? (Please note: Price refers to Sterling Price a Confederate general from Missouri. Secesh is short for “secessionist,” a supporter of the Confederate cause.)

Writing the War for the Union II

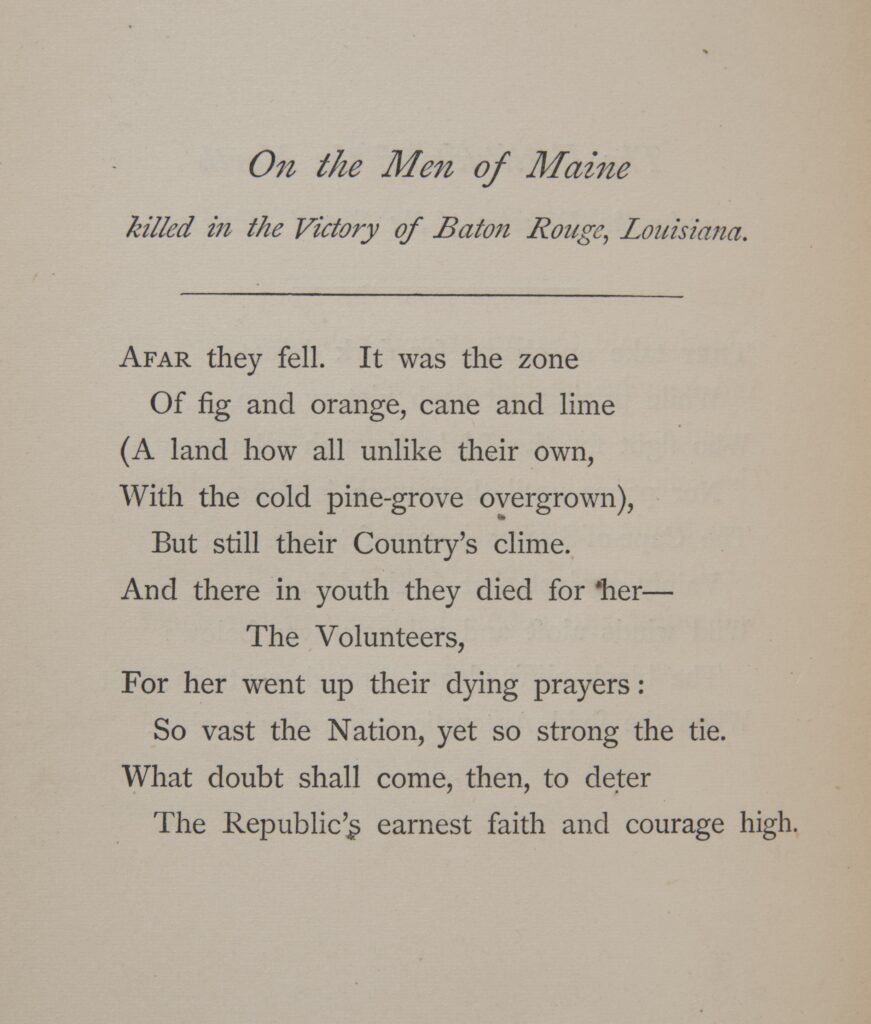

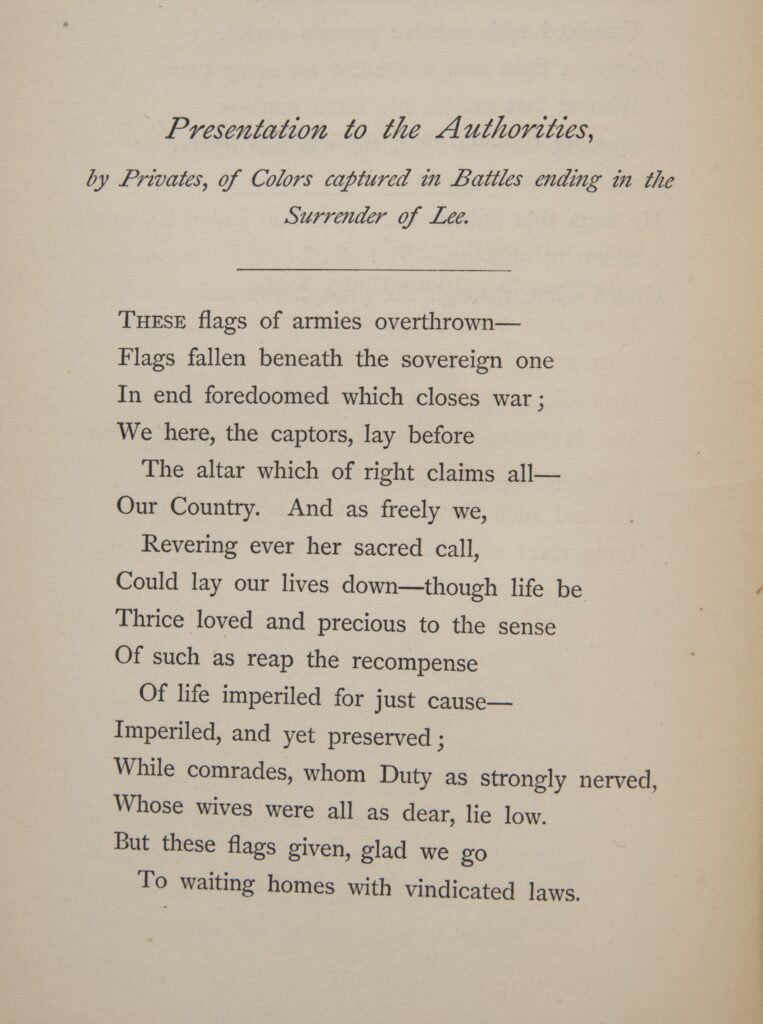

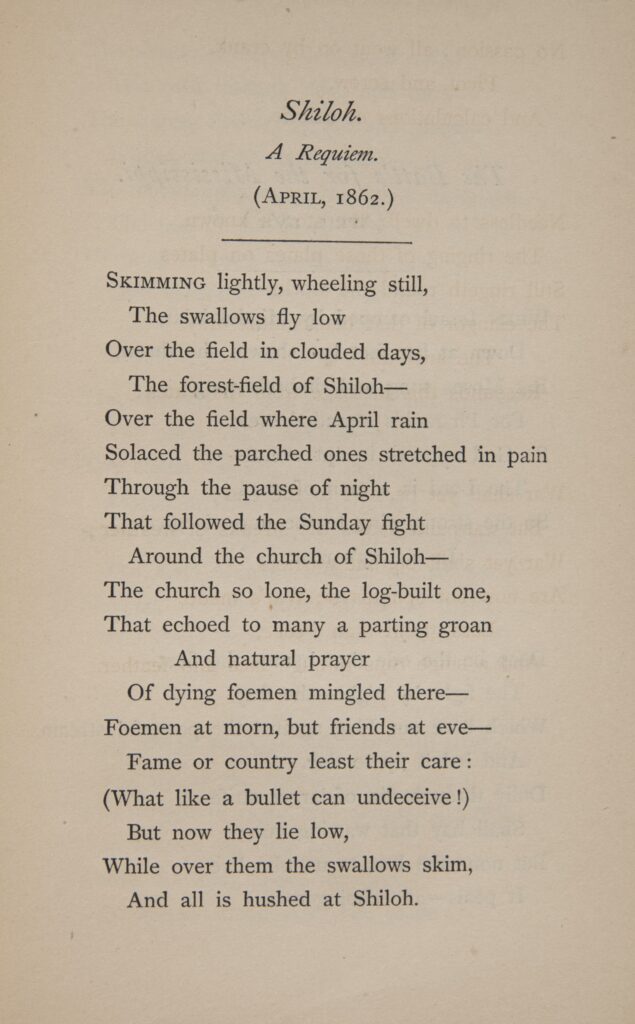

The poems that follow are by Herman Melville, a writer more commonly associated today with great works of fiction, such as Moby Dick and “Bartleby the Scrivener.” Melville responded to the Civil War by writing poetry, publishing this book, Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War, the year after the war had ended. The book is dedicated “to the memory of the three hundred thousand who in the war for the maintenance of the Union fell devotedly under the flag of their fathers.” It offers a lyric history of the war, moving chronologically through battles and other important events. The poems presented here express both devotion to the national cause and ambivalence about the meaning of war itself.

The poem “Shiloh” refers to a battle that took place in Tennessee on two days in April 1862. It began with a strong Confederate strike, but the Union army turned the battle on the second day and defeated the Confederate forces. Each side suffered over 1,700 killed and over 8,000 wounded. At the time, it was the bloodiest battle in U.S. history. A requiem is a chant or dirge that lays the dead to rest.

The last two poems are from a section entitled “Verses Inscriptive and Memorial.” The first refers to the Battle of Baton Rouge in August 1862, when Confederate forces tried and failed to recapture that city. The last refers to the presentation of captured, Confederate flags to Union authorities after General Robert E. Lee’s surrender.

Questions to Consider

- In “Shiloh,” Melville creates a vivid image of the battlefield after the fighting has ended. He draws our attention, especially, to the natural environment: the swallows, the “forest-field,” the rain, and even the church, which is made of logs and echoes a “natural prayer.” Why do you think Melville foregrounds the natural world in this poem laying the dead to rest? What relationships does he suggest between the natural world and the spiritual one suggested by the church, which provides the center and turning point for the poem?

- Consider the last 10 lines of “Shiloh.” Who are the “foemen,” or enemies? Why do the “Foemen at morn” become “friends at eve—Fame or country least their care”? How might “a bullet…undeceive”? What truth does death reveal? How does this transformation affect the meaning of the men’s deaths and of the war as a whole?

- As in the poem “Shiloh,” Melville begins “On the Men of Maine” with attention to the natural environment. Why does the poem contrast Louisiana’s “zone of fig and orange” to the Maine soldiers’ familiar land? How does this contrast relate to the idea of the nation that the poem presents?

- How does Melville represent patriotism and the idea of sacrificing one’s life for one’s country in “Presentation to the Authorities”?

- Compare the tone of these poems to “Shiloh.” How do they differ in their responses to war-related deaths?

- Do these poems suggest ways for the country to move forward after the war?

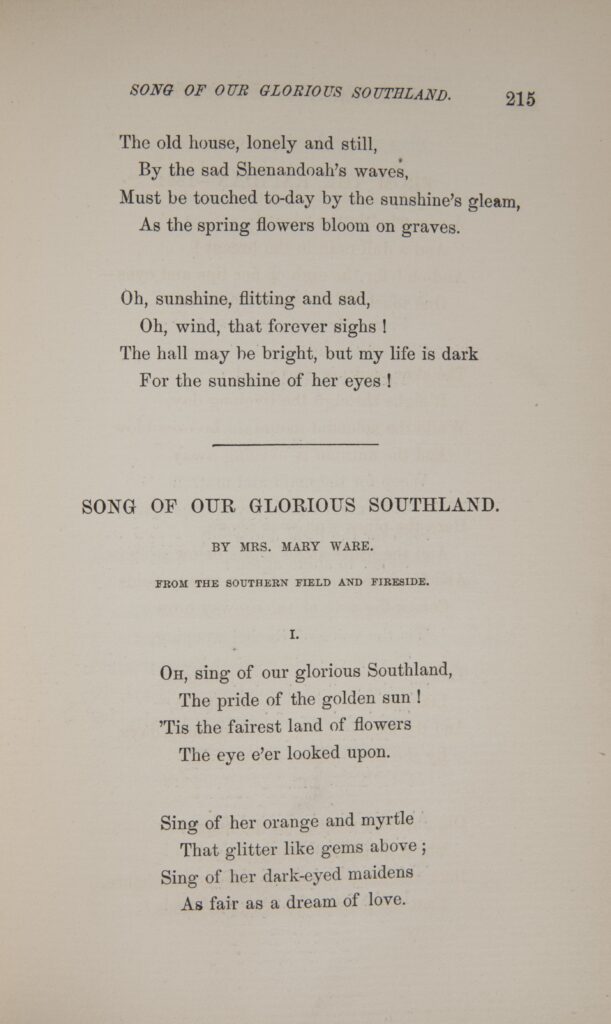

War Poetry of the South

Publishing conditions in the South were dramatically different from those in the North at the time of the Civil War. As historian Alice Fahs explains, before the war, the North had many more printing presses than the South. Much of the literature that Southerners read was published in the North. The war exacerbated this disparity: the South experienced severe shortages of paper and ink as well as personnel to run what presses remained south of the Mason-Dixon line. War Poetry of the South, the anthology excerpted below, reflects these conditions: it was published in New York the year after the war ended.

Selection: Mary Ware, “Song of Our Glorious Southland” in War Poetry of the South, 215-216 (1866)

Simms gleaned the poems in War Poetry of the South from various Southern magazines and newspapers as well as from his private correspondence. The poems selected here are all by women who were well-known poets at the time.

Selection: Anna Peyre Dinnies, “The Confederate Flag,” in War Poetry of the South, 478-480 (1866).

Selection: Carrie Bell Sinclair, “Georgia, My Georgia!” in War Poetry of the South, 170-172 (1866)

Questions to Consider

- Consider the use of the terms liberty, oppression, and patriotism in the poems “Georgia, My Georgia!” and “Song of the Glorious Southland.” What do these words mean in the context of these poems? Who is the oppressor? What forms of freedom are under threat? (Please note: “the Stars and Bars” refers to the Confederate flag.)

- Words such as liberty implicitly evoke the rhetoric of the American Revolution. What relationships do these poems suggest between the Revolution and the Civil War? What are the reasons for the Civil War, according to these works? What does the war mean?

- Compare “The Confederate Flag” to Northerners’ representations of the U.S. flag. What does the Confederate flag symbolize to the poem’s speaker in light of the South’s defeat? In what ways do the flags play similar or different roles for people on opposing sides of the Civil War?

- William Gilmore Simms wrote in the preface to War Poetry of the South, “Though sectional in its character, and indicative of a temper and a feeling which were in conflict with nationality, yet, now that the States of the Union have been resolved into one nation, this collection is essentially as much the property of the whole as are the captured cannon which were employed against it during the progress of the late war. It belongs to the national literature.” Rewrite this statement in your own words. What does Simms mean by it? In what ways are these poems like the Confederacy’s cannons? How will these poems find a place in American literary history?

- Southern political texts make clear that secessionists went to war largely to protect the institution of slavery. (See, for example, Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina). Yet these poems make no reference to chattel slavery. Why do you think that is?

- Taken together, what feelings do these poems express about the war? What possibilities do they offer for the future of the South and for its reintegration into the United States?

Literature of Emancipation

For many people, the most important effect of the Civil War was that it ended slavery. The North did not enter the war with the goal of freeing the slaves; it fought to preserve the Union. But the South seceded in order to protect the institution of slavery. And in the North, the literature on slavery and emancipation played an essential role, first, in promoting the cause of abolition and, then, in helping Northerners understand the significance of emancipation when it did arrive. For these reasons, the literature of emancipation is integral to the literature of the war itself.

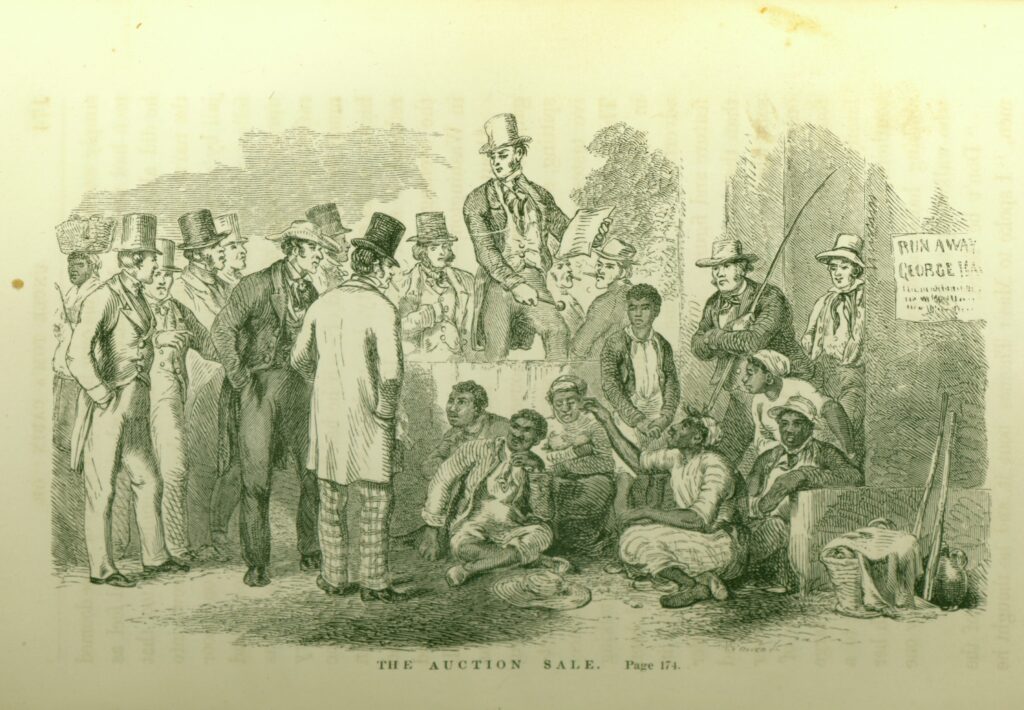

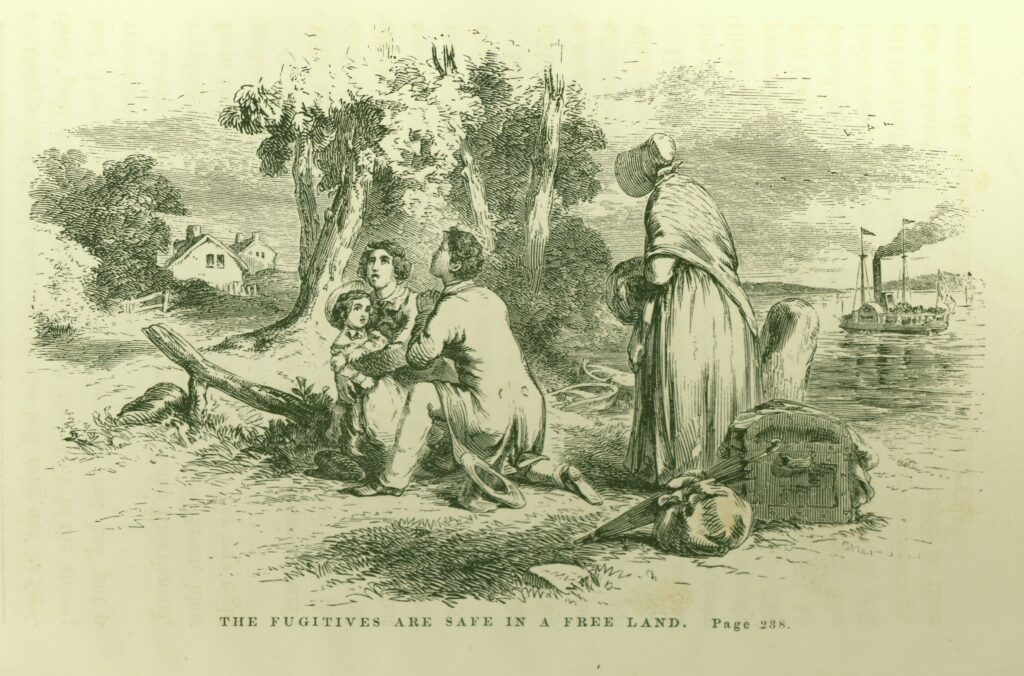

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin was the single most influential literary text in the antislavery cause. It was first published serially in 1851–1852 in the antislavery newspaper the National Era. When it appeared in book form later in 1852, its popularity “had no precedent,” writes critic Elizabeth Ammons. “The book sold more copies than any book except the Bible.” The illustrations below appeared in that first edition. They shed light on the ways that Northern readers imagined the suffering that slaves experienced and the struggle for freedom.

Selection: Hammatt Billings, “The Auction Sale” and “The Fugitives are Safe in a Free Land” in Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe (1852).

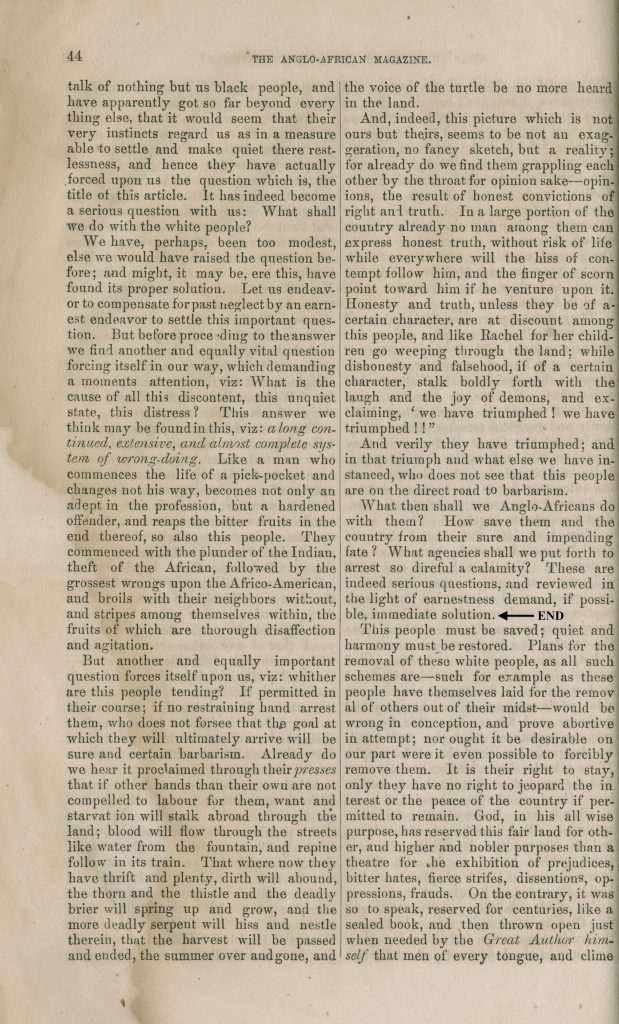

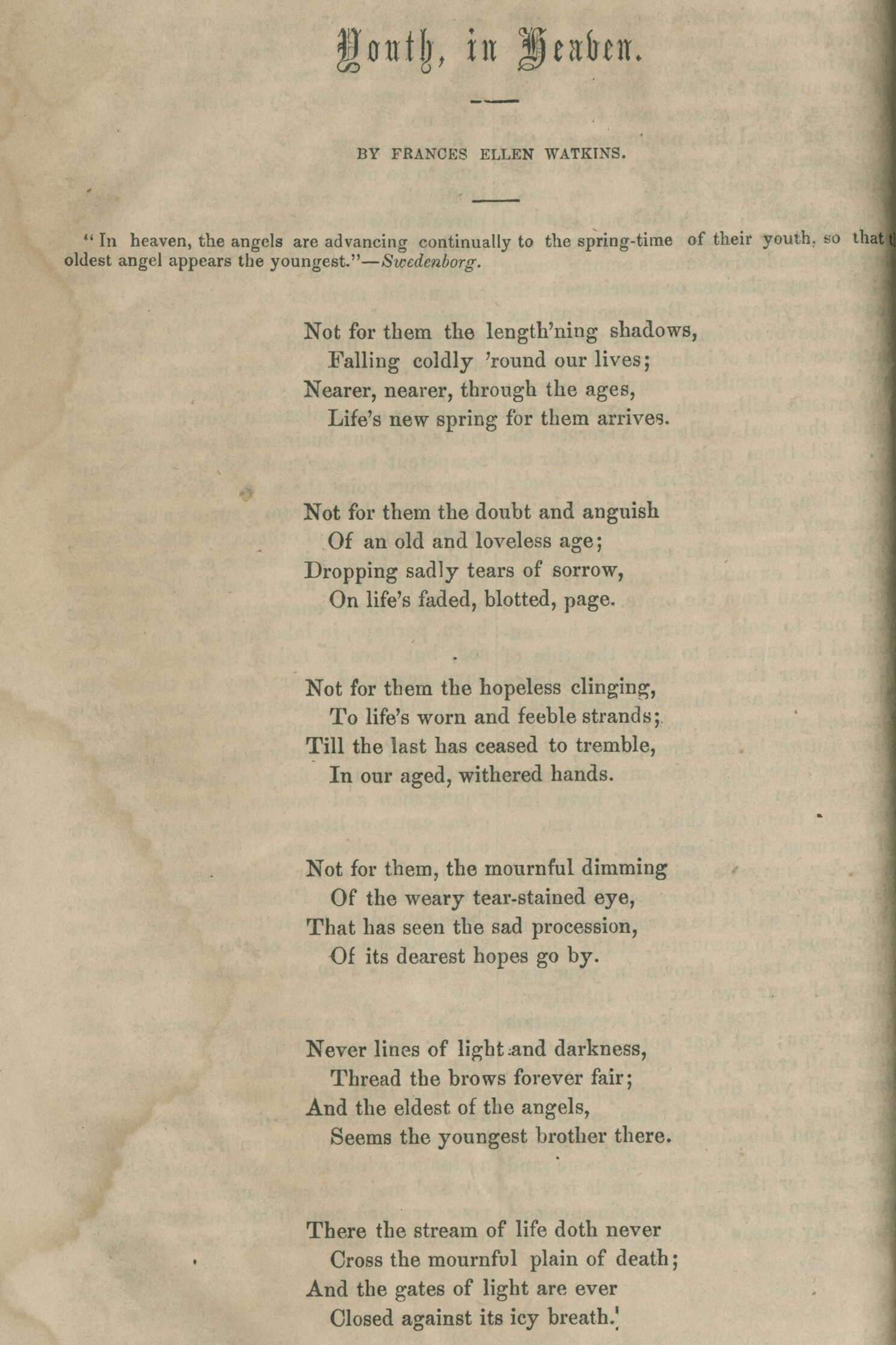

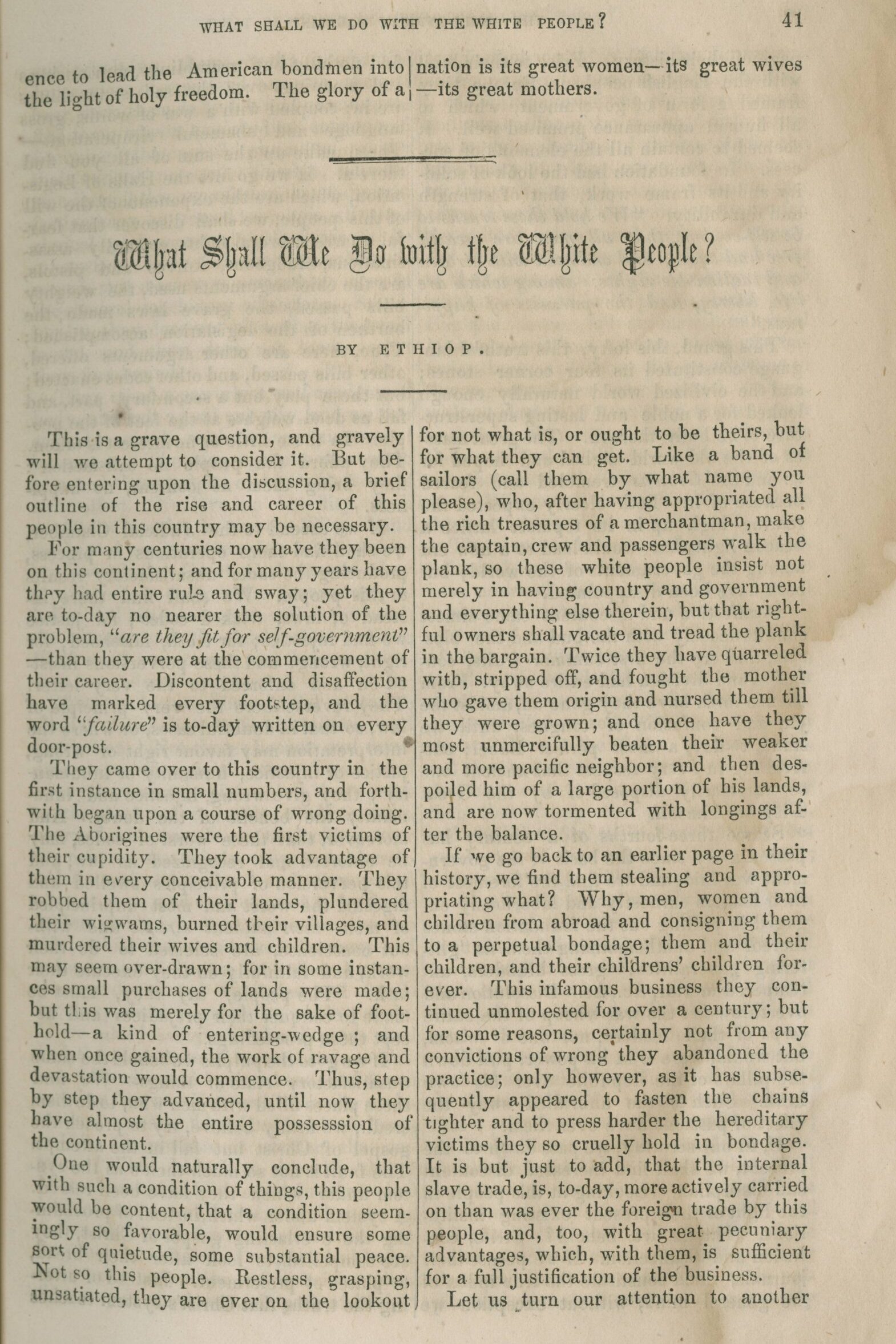

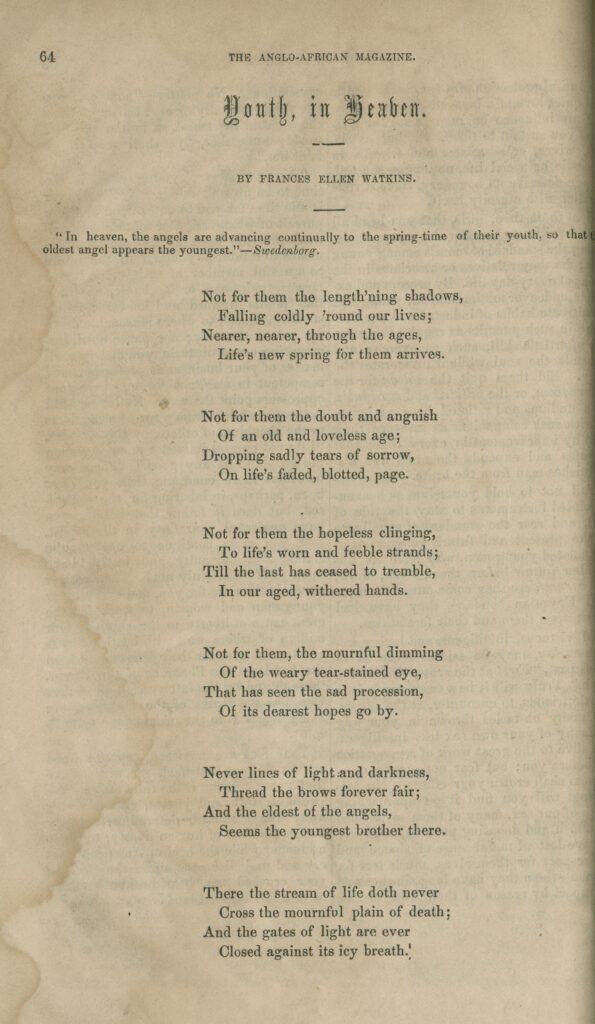

The monthly Anglo-African Magazine was “the first literary magazine produced by and for the black community,” the scholar Eric Gardner notes. Its editor, Thomas Hamilton, published the magazine in New York in 1859 and 1860 along with a newspaper, the Weekly Anglo-African, which ran from 1859 to 1865. Hamilton laid out in the magazine’s first issue his intention to feature African American writers and to reach African American readers. “We need a Press—a press of our own,” he wrote, and a forum for “our own advocacy.” The magazine included fiction and poetry as well as political and social commentary. The excerpts below are from the magazine’s final issue. William J. Wilson was a prolific essayist who often published under the pseudonym Ethiop. (The name commonly referred to African Americans in the nineteenth century and evoked African contributions to human civilization.) Frances Ellen Watkins was one of the most famous African American writers and activists in the nineteenth century.

Selection: Ethiop, “What Shall We Do with the White People?” The Anglo-African Magazine, 41-44 (1860)

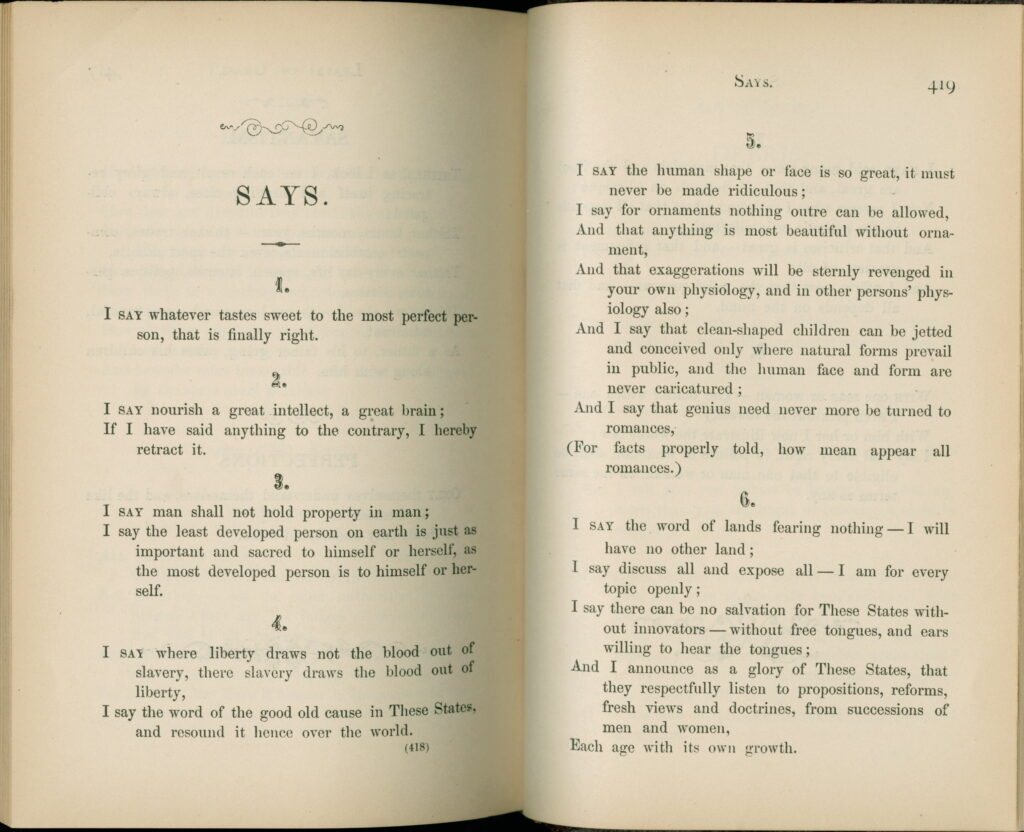

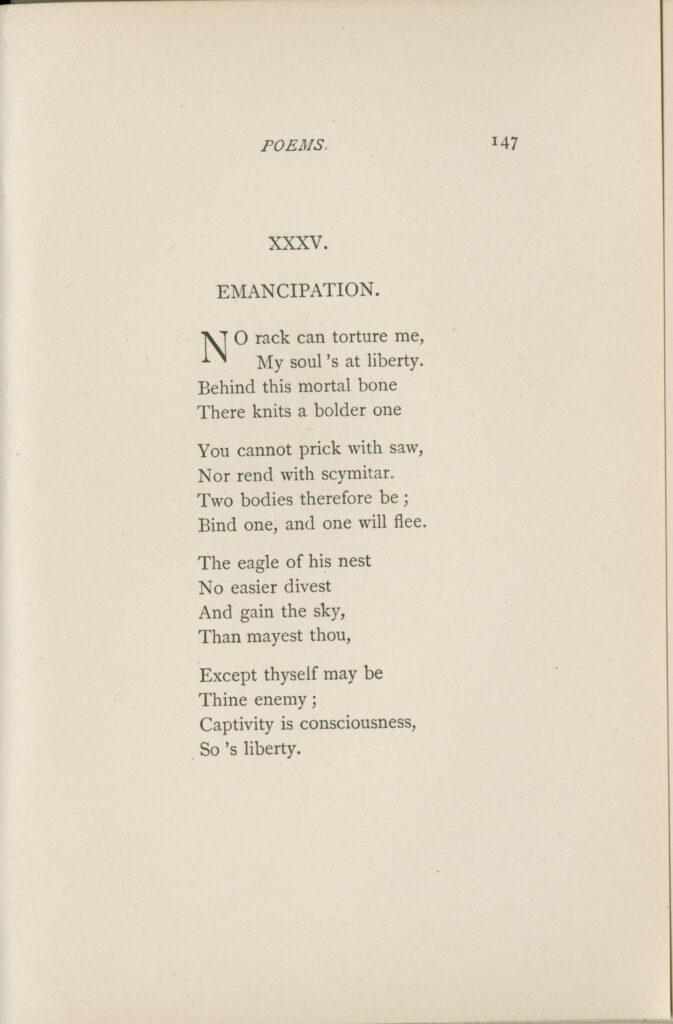

The final two poems below suggest some of the ways that the now-canonical writers Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson responded to slavery. Whitman first published Leaves of Grass in 1855 but continued to revise and reissue the work throughout his life. The poem by Emily Dickinson was first published posthumously in this 1890 edition edited by Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Mabel Loomis Todd. Higginson was an abolitionist and colonel who led the First South Carolina Volunteers, a regiment of black soldiers composed mainly of former slaves. Higginson and Todd added the title “Emancipation” to Dickinson’s untitled poem upon publishing it.

For related sources, see Lincoln, the North, and the Question of Emancipation.

Questions to Consider

- Examine the illustrations from Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. How are African Americans and whites portrayed in these drawings? What would Northern readers have learned about slavery from these images? In what ways do you think they support or undermine the novel’s abolitionist message?

- What questions does Ethiop (William J. Wilson) raise about white Americans and their capacity for self-governance in “What Shall We Do with the White People?” How would you characterize the tone of this essay? How does it parody nineteenth-century arguments concerning African Americans? In what ways do you think the critique is or is not meant to be taken seriously?

- Watkins opens her poem “Youth, in Heaven” with a quote from Emanuel Swedenborg, an eighteenth-century Swedish philosopher and theologian who influenced many nineteenth-century American writers. How does she elaborate his claim that angels grow younger with time? Do you see this poem as an escape from the abolitionist concerns that dominated much of Watkins’ life and work? Or does this meditation on angels in heaven also implicitly respond to conditions on earth?

- Consider the first four “says” in Whitman’s poem. How does the statement “I say man shall not hold property in man” relate to the statements that precede and follow it? What do you think Whitman means by his statement in section four concerning liberty, slavery, and blood?

- Examine the first two stanzas of Dickinson’s poem. What claim does she make about the relationship between the soul and the body? How does she understand the nature of freedom?

- What does Dickinson suggest in the final two stanzas? Who is the one enemy to the soul’s liberty?

- The title of Dickinson’s poem “Emancipation” was provided by her editors after her death. There is no way to know whether Dickinson herself would have approved it. Do you think the title fits? Would you interpret the poem differently without that title? How so?

- How do Whitman’s and Dickinson’s uses of the term liberty compare to the term’s use by Southern writers in the section above?

Women and the Home Front

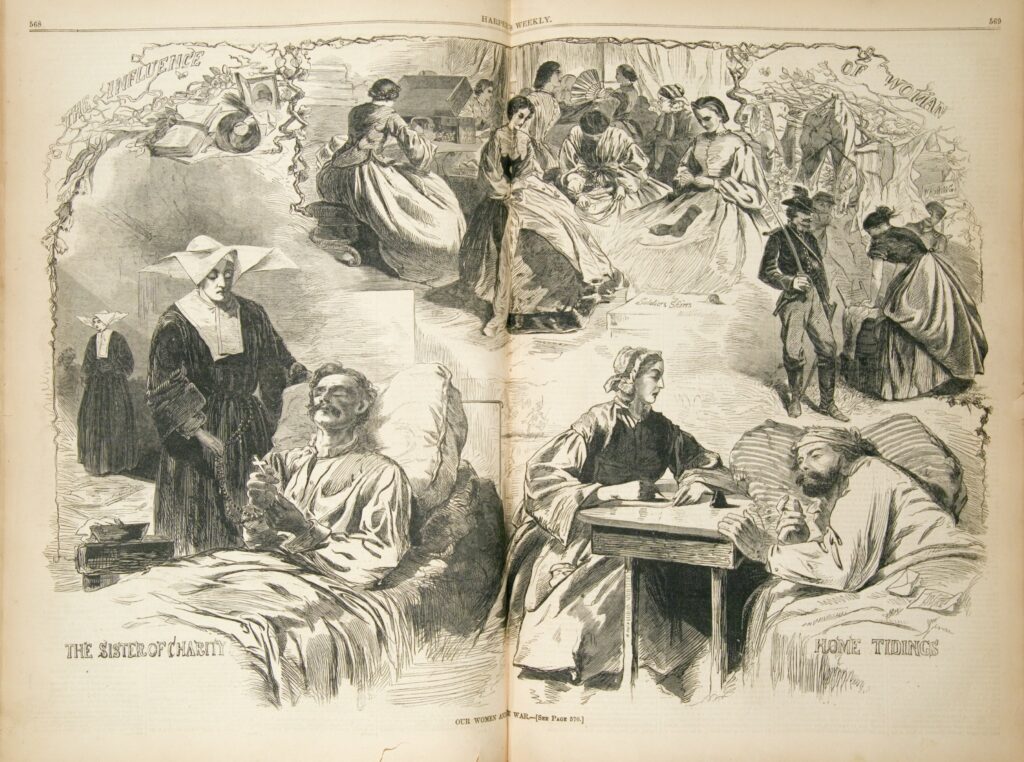

In the North and South alike, women took up new responsibilities when their fathers, husbands, and sons left home to serve in the war. Traditionally female domestic chores took on new meanings during wartime. Middle-class women stitched shirts and flags, while working-class women in factories and sweatshops produced uniforms and cartridge bags by the millions. Women ran family farms, nursed the wounded, spearheaded fundraising initiatives, and became increasingly visible in society and the economy. During the war, as before it, many women continued to be voracious readers of periodicals and novels.

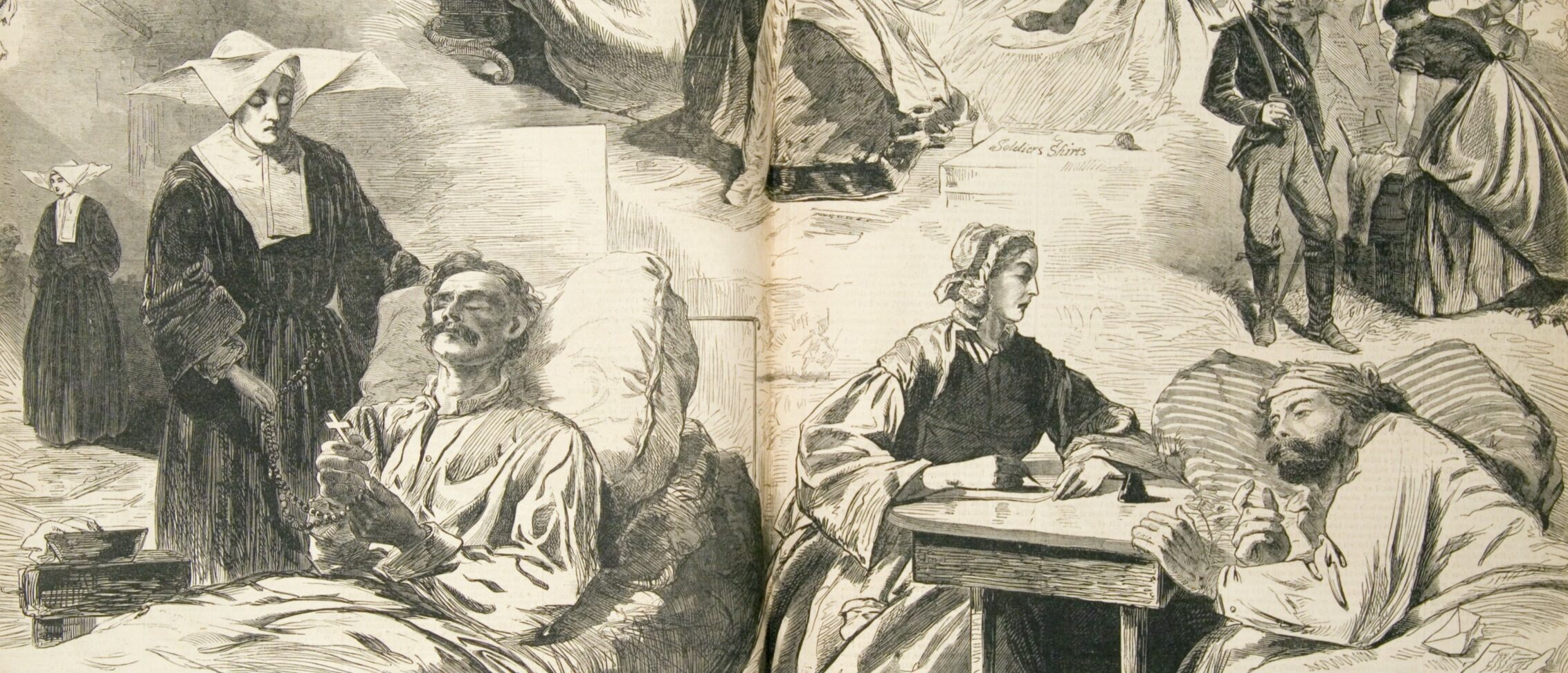

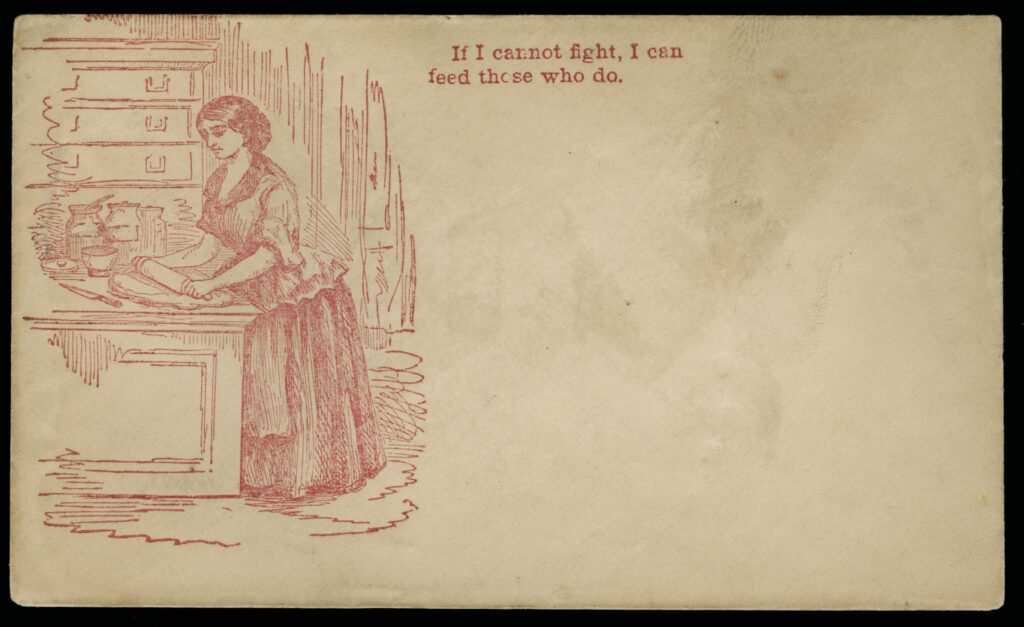

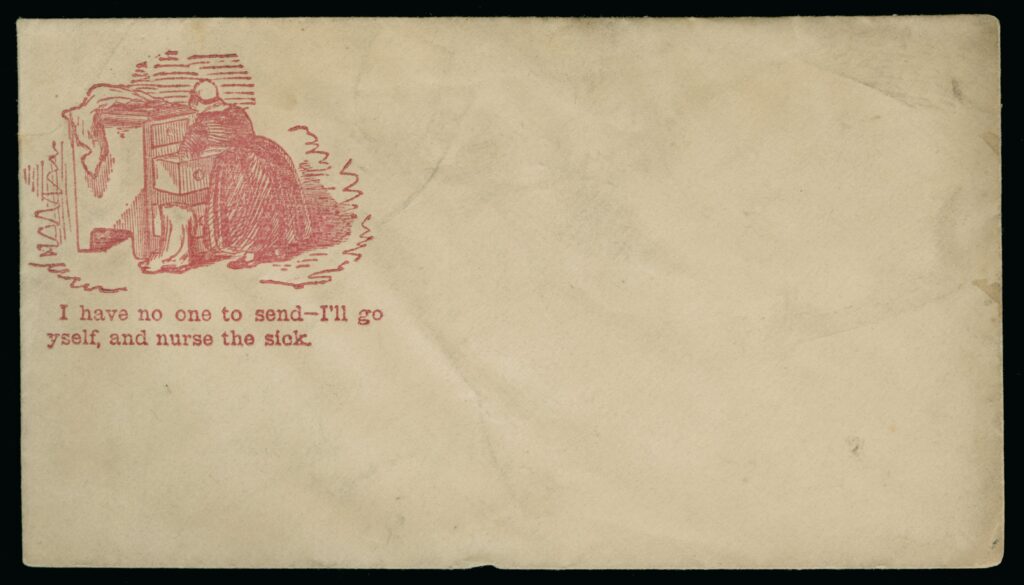

The illustrations and captions in this section suggest some of the ways that women’s wartime work shaped literary culture in the North. The Harper’s Weekly illustration portrays women sewing soldiers’ uniforms, caring for the wounded, and washing laundry in a military camp. Patriotic envelopes, such as the two below, were enormously popular and printed in thousands of different designs.

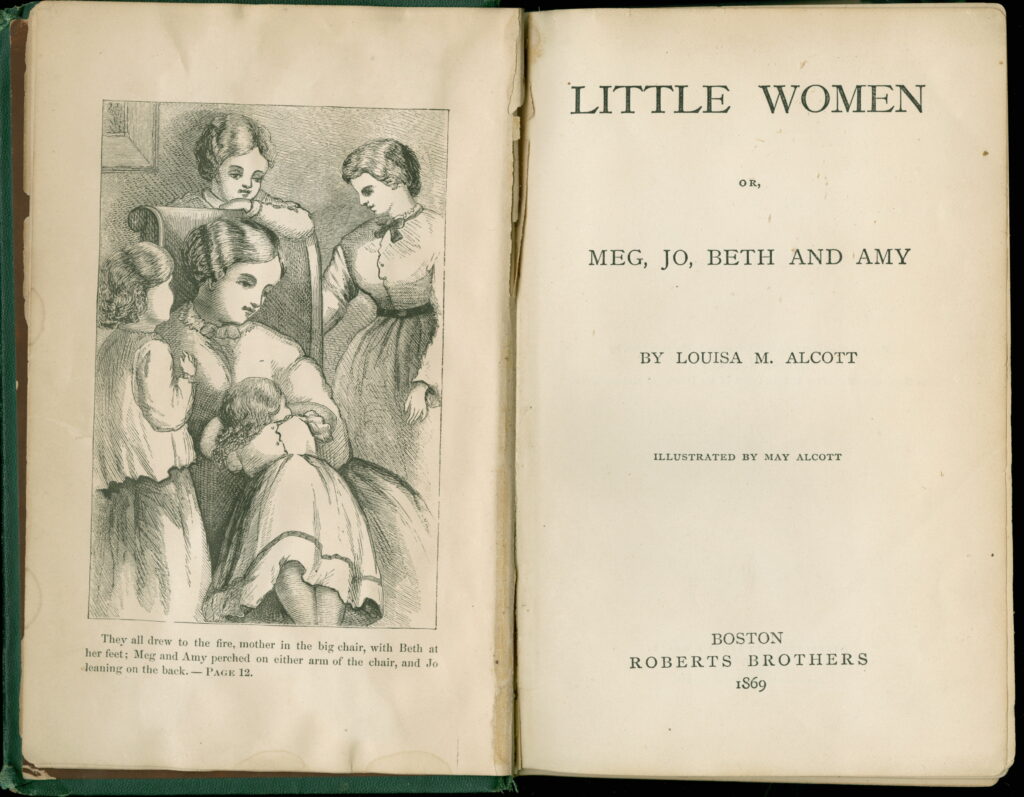

Finally, the novel Little Women was published just a few years after the war ended. The mother and daughters of the March family try to contribute to the war effort while their father is serving as a chaplain in the U.S. Army. When the father returns home wounded, he requires care from his wife and daughters.

Questions to Consider

- How does women’s wartime work appear in the Harper’s Weekly illustration? What kinds of work are available to women? Does this work seem important to the war effort? What message do you think the image communicated to readers at the time?

- Why do you think envelopes such as these were popular during the war? How might they serve to promote the war effort?

- What makes the family group on the frontispiece of Little Women especially evocative of the war? How might a narrative like this help readers come to terms with their own wartime experiences?

- Based on these texts, what were some of the changes that the war brought to people’s lives far from the front lines? In what ways does the war seem to have changed women’s roles in society and in the family? In what ways did expectations of women remain the same?

- Compare these representations of women’s contributions to the Civil War to images from World War I. What do these documents suggest about changes in gender roles between the two wars?

War Writings for the North

These texts, produced by Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, journalist Frank More, and novelist Herman Melville, offer a glimpse into the numerous writings about the war consumed by Northern audiences, including newspaper reports, vignettes, and poetry.

War Poetry of the South

Due to the publishing conditions in the South, much of the literature that Southerners read during the Civil War was published in the North, as with the anthology War Poetry of the South. These poems from this text, all authored by women, provide insight into Southern sentiments about the war, the Confederacy, and the relationship of the South to the U.S.

Literature on Slavery and Emancipation

From illustrations inspired by Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin to pieces published in the Anglo-American Magazine and poetry by Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson, literature on slavery helped shed light on the experiences of the enslaved, promote abolitionism, and make clear the significance of the struggle for freedom.

Women and the Home Front

As depicted in these illustrations and Louisa May Alcott’s novel Little Women, women in both the North and South took on new responsibilities and roles when their husbands, fathers, sons, and brothers left to serve in the war and contributed in a variety of ways to the war effort.

Further Reading

Brownlee, Peter John and Daniel Greene, curators. Home Front: Daily Life in the Civil War North. Exhibition co-organized by the Newberry Library and the Terra Foundation for American Art. 2013.

Coviello, Peter. “Battle Music: Melville and the Forms of War” in Melville and Aesthetics, edited by Samuel Otter and Geoffrey Sandborn (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 193–212.

Fahs, Alice. The Imagined Civil War: Popular Literature of the North & South, 1861–1865 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001).

Gardner, Eric. Unexpected Places: Relocating Nineteenth-Century African American Literature (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009).

Hager, Christopher and Cody Marrs. “Against 1865: Reperiodizing the Nineteenth Century.” Journal of Nineteenth-Century Americanists 1, no. 2 (Fall 2013): 259–284.

Terra Foundation for American Art. The Civil War in Art: Teaching and Learning through Chicago Collections. 2012.

Wilson, Ivy. “‘Are You Man Enough?’: Imagining Ethiopia and Transnational Black Masculinity.” Callaloo 33, no. 1 (2010): 265–277.

Wimsatt, Mary Ann. “William Gilmore Simms.” American National Biography Online (Feb. 2000).