Introduction

When the Great War began in Europe in 1914, few Americans believed the United States should get involved. President Woodrow Wilson issued a proclamation of neutrality, urging Americans to remain “impartial in thought as well as in action,” and worked to resolve the conflict through diplomacy. This policy proved impossible to maintain. Britain was one of America’s closest trading partners and Germany’s effort to shut down Allied ships soon affected the United States. One-hundred-twenty-eight Americans died when German U-boats sank the British passenger ship Lusitania in May 1915, and public sentiment began to shift in favor of U.S. involvement. As the presidential election of 1916 approached, Wilson emphasized “preparedness” in speeches and parades designed to show that he and the nation were not timid, but ready for war, if necessary. At the same time, Wilson campaigned and won the election under the slogan “He Kept Us Out of War.”

While World War I was not fought on U.S. soil, it had an enormous social and cultural impact on the nation.

But by the spring of 1917, the Allies were running low on money and supplies, and Allied troops had been decimated. In March, German U-boats sunk four American merchant ships. On April 6, 1917, the United States formally declared war and, a year and a half later, secured the Allied victory. Ten million soldiers (including 50,000 Americans) and nearly seven million civilians had lost their lives.

While World War I was not fought on U.S. soil, it had an enormous social and cultural impact on the nation. President Wilson made a concerted effort to maintain public support for his policies through propaganda as well as legal prosecution. Americans participated in countless parades and commemorative events to demonstrate, first, preparedness, then support for the war. In April 1917 his administration formed the Committee on Public Information (CPI) and hired writers and speakers to promote the war effort throughout the country. People who opposed the war, such as reformer Jane Addams and Senator Robert La Follette, were subject to public ridicule. With the passage of the Espionage Act (1917) and the Sedition Act (1918), critics of the war effort became subject to fines and jail sentences.

The following collection of documents explores U.S. popular—and, especially, visual—culture during World War I. These sources were not produced by the government. Rather, they demonstrate how extensively private companies, organizations, and individuals embraced the war effort. Atlases, cartoons, advertisements, and sheet music all expressed support for the war with remarkable consistency and reinforced the government’s messages. One exception was the socialist magazine the Masses, which provides dissenting voices among the documents below.

Please consider the following questions as you review the documents

- How did popular publications encourage Americans to support the war effort?

- How did artists, advertisers, and mapmakers visually represent the war to the American public? What patterns or conventions do you notice in these images of soldiers? What ideals of masculinity and national identity do they express?

- What criticisms of the government and, specifically, the war effort did dissenters voice? How did dissenting artists parody or otherwise subvert pro-war propaganda?

Mapping the War

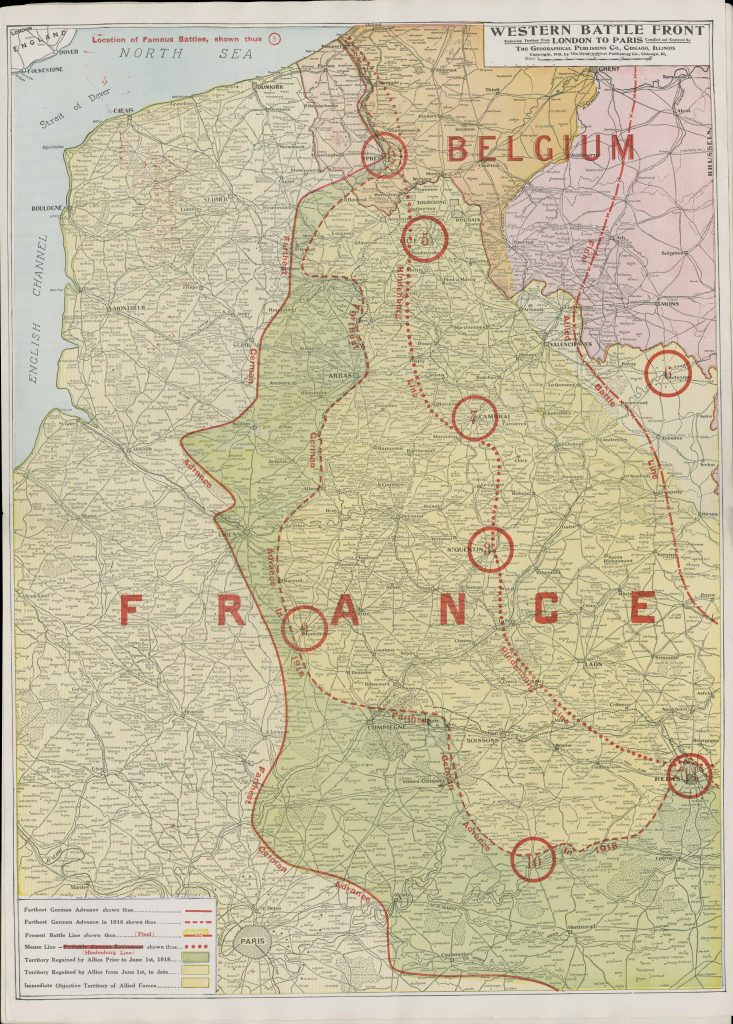

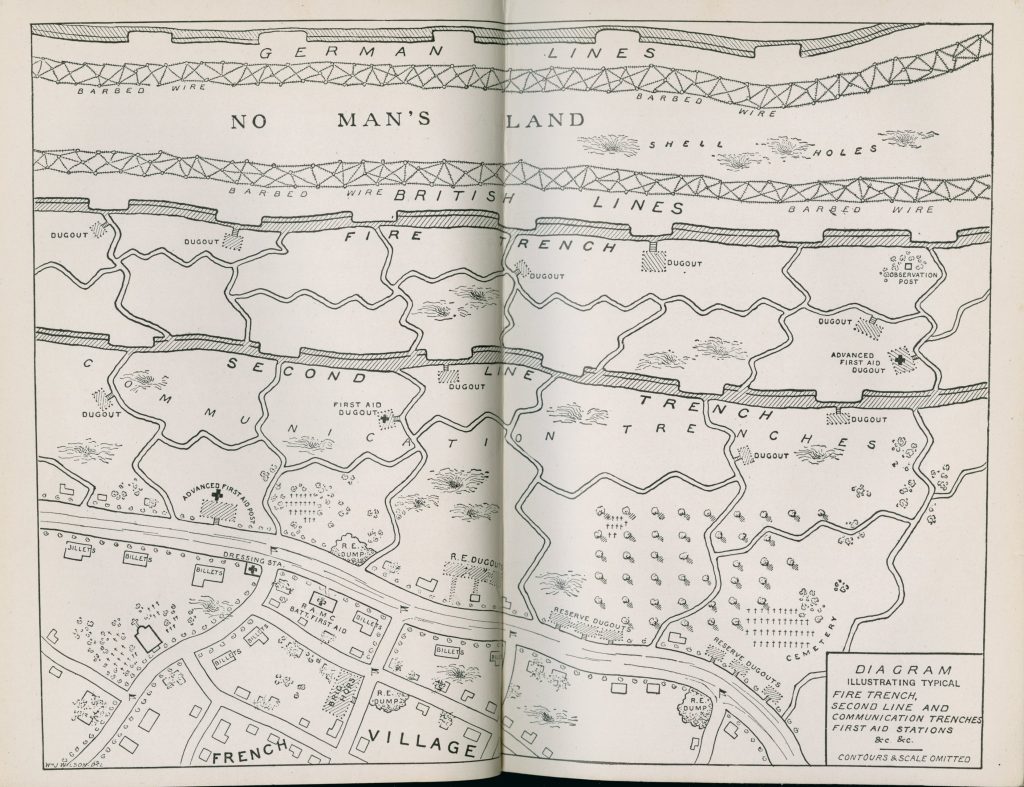

The two maps below offer very different perspectives on the infamous Western Front. The term Western Front refers to the combat zone where Germany, on the east, met Allied troops from the west. Germany opened the Western Front by invading Belgium and then France in August 1914. The front was marked by a line of trenches stretching from the North Sea through Belgium, northeastern France, and Alsace-Lorraine to the Swiss-French border. Though the front was the site of several major military offenses and a great deal of human suffering, it moved very little until 1918. That spring, Germany succeeded in pushing the front 60 miles west, within shelling range of Paris. In the summer and fall of 1918, the Allied counteroffensive along the Western Front led to Germany’s surrender.

The map above offers a soldier’s perspective on the front line. Arthur Guy Empey was a 32-year-old recruiting sergeant in the U.S. Army in 1915, when he became disgusted with the American policy of neutrality in the war. He traveled to England to enlist in the British army and served with the British in France until he was wounded at the beginning of the Battle of the Somme. (This battle was one of the bloodiest during the war. It took place along the river Somme from July to November 1916 and resulted in an estimated one million casualties. The Germans retreated from the Somme in early 1917, falling back 40 miles to the Hindenburg Line.)

After his return to the United States, Empey published an account of his war experiences that became enormously popular. He went on to write and star in a film based on the book and to tour the United States, promoting the war effort and helping to shift public sentiment away from neutrality.

Selection: Arthur Guy Empey, Over the Top, title page, frontispiece, and map (1917).

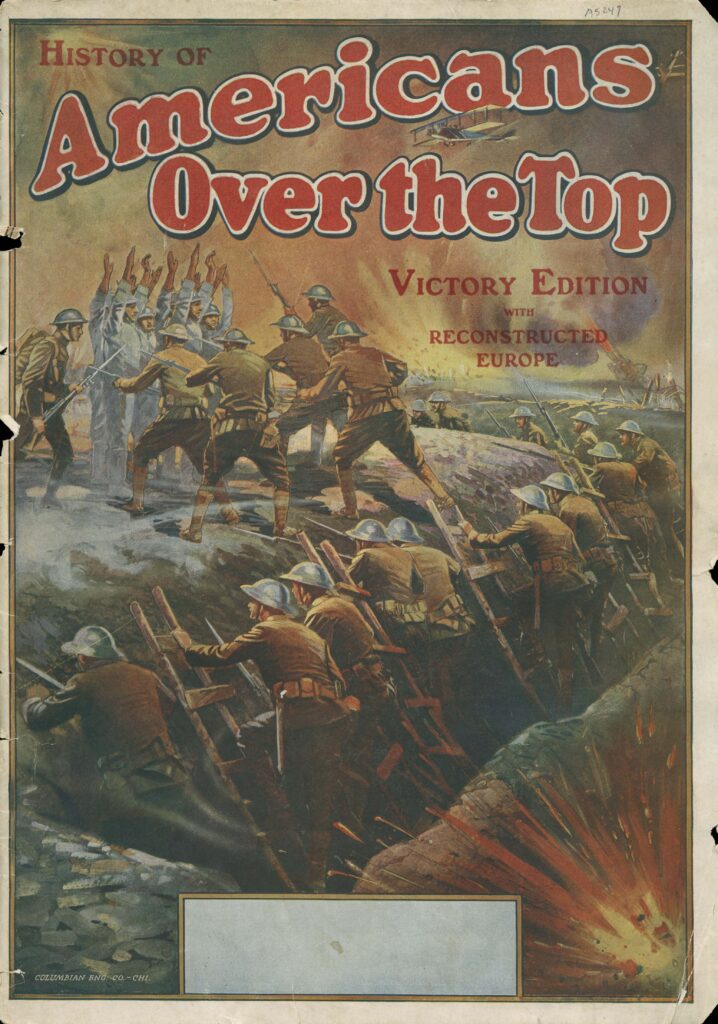

The second document below is an atlas published in Chicago in 1918 at the close of the war. It offers an early history of the war from a victorious, American perspective.

Selection: Geographical Publishing Company, Americans Over the Top, cover and map (1918).

Questions to Consider

Both documents embrace the phrase over the top in their titles. The expression originated during World War I to refer to the act of climbing out of the trenches and charging toward the enemy’s defenses. Doing so required running through no man’s land, the barren space between the two armies’ lines, where soldiers were unprotected and exposed to enemy fire. As writer Evan Morris notes, “‘Going over the top’ was frequently fatal; on the first day of the Battle of the Somme in France (July 1, 1916), the British Army lost almost 60,000 soldiers.” As a result, going over the top was associated with extraordinary bravery during and after the war. It was not until the 1930s that, according to Morris, the phrase acquired its current meaning of “going too far” or “being excessive.”

- Examine Empey’s diagram of the front line. What information does it include? How does the physical space of the front seem to be organized?

- How does Empey’s diagram convey his perspective on the landscape as a soldier in the British Army? What insight does it give you into the experience of warfare during the Great War?

- Describe the cover of Americans Over the Top Atlas? How does the illustration portray the soldiers’ experience of the war? What emotions in the viewer is this illustration meant to elicit?

- What information appears in the map of the Western Front included in Americans Over the Top Atlas? How does the map visually convey the events and history of the war?

Popular Music and the War

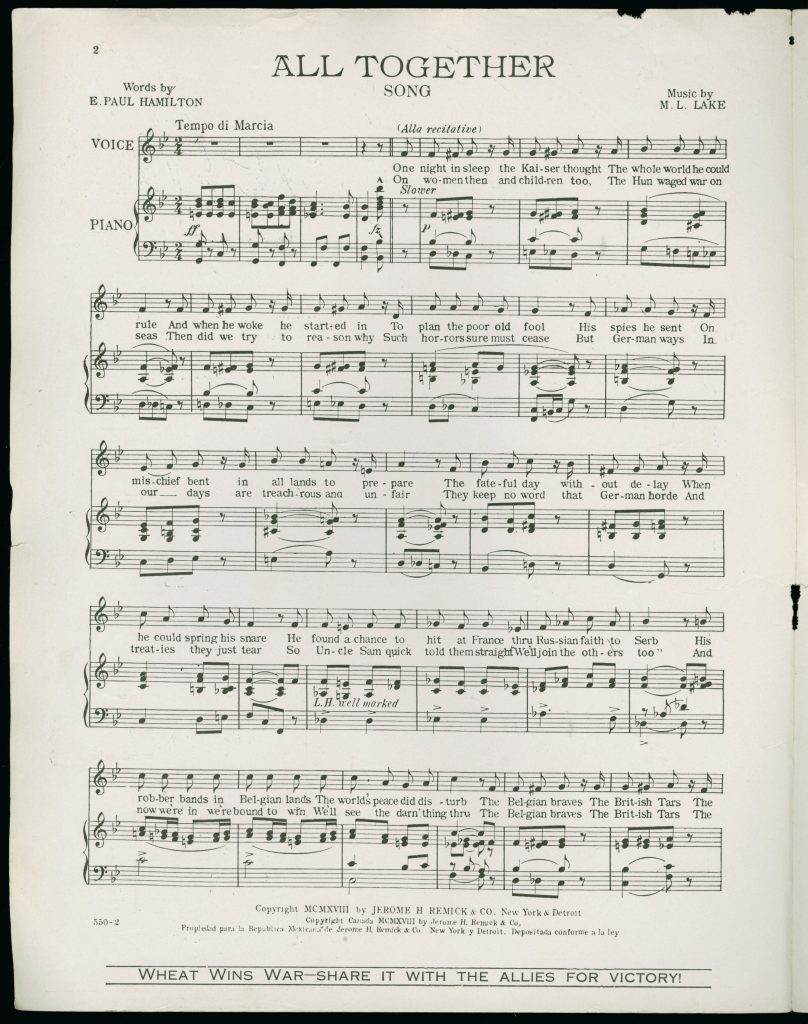

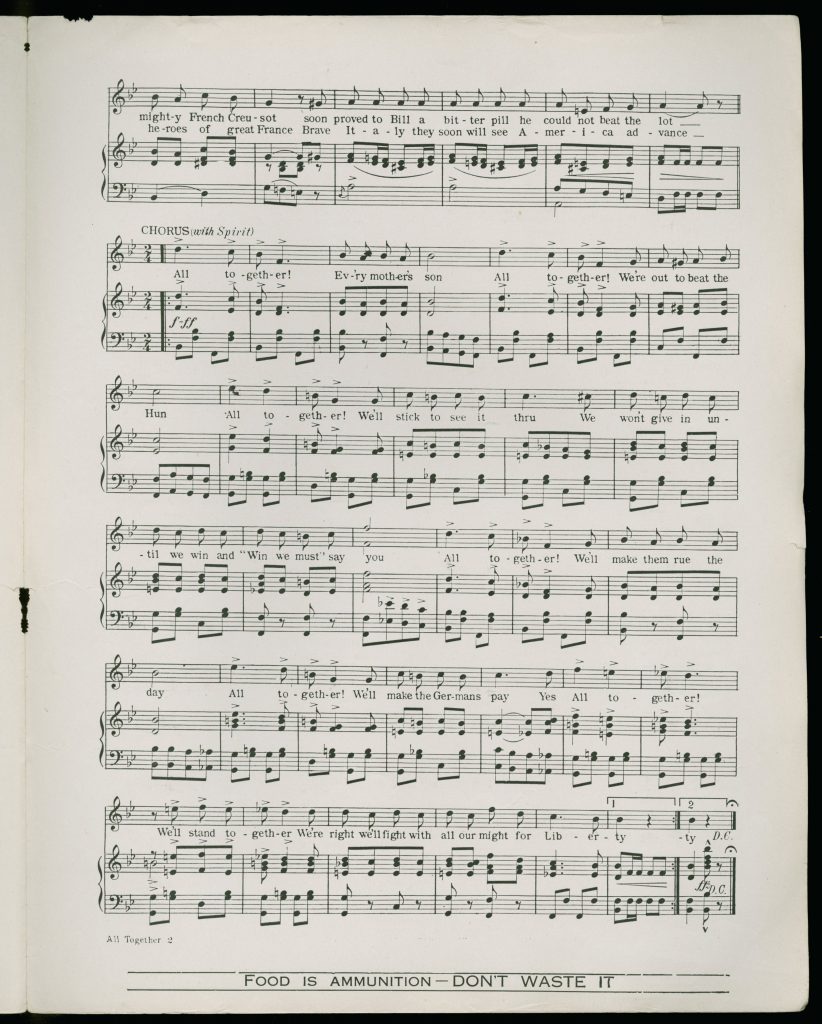

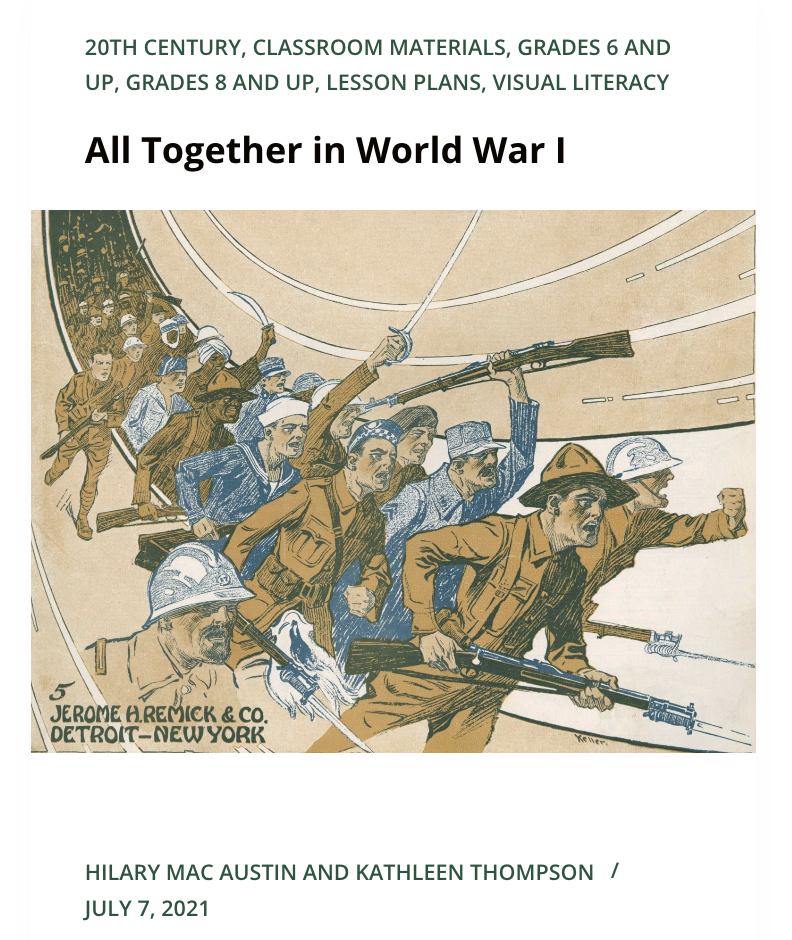

Selection: M. L Lake and E. Paul Hamlition, All Together: “We’re Out to Beat the Hun” (1918).

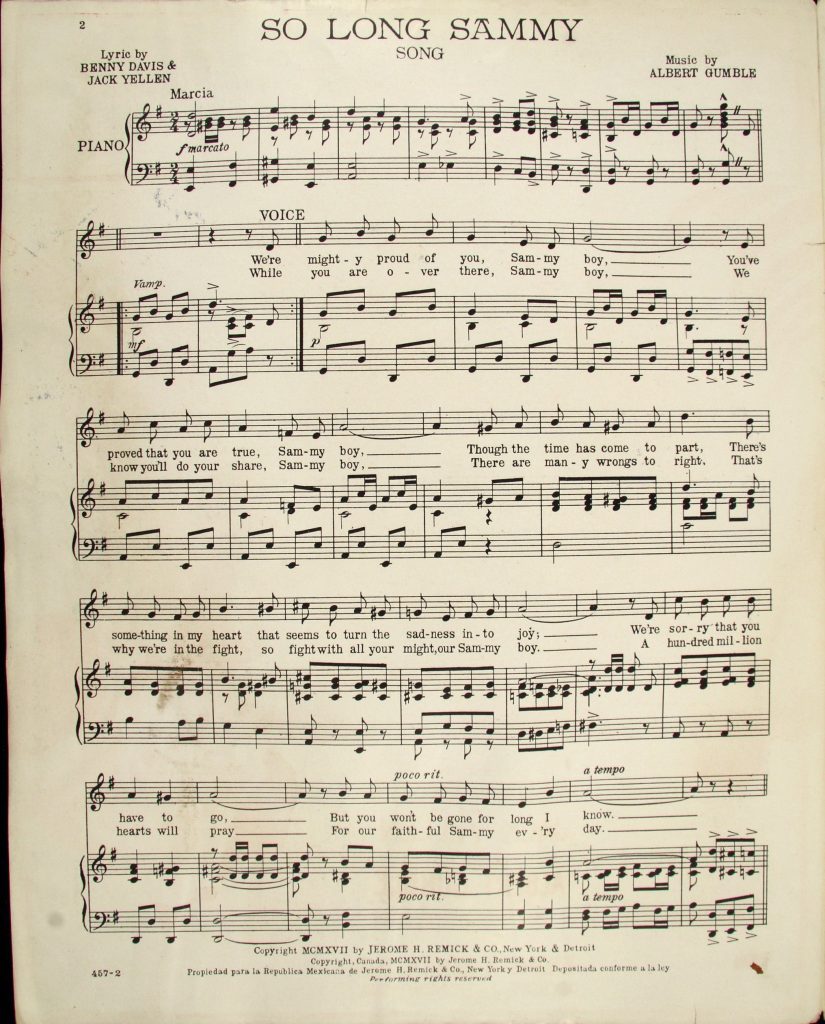

At a time when many American homes had pianos and few had gramophones (early record players), sheet music played an important role in popular culture. People gathered in their living rooms to sing songs or heard them performed at music halls and parades. After the United States joined the war, the government turned to songwriters to help promote the war effort. Historian Jennifer Wingate notes that “70 percent of all copyrighted songs in 1918 were war songs.” Earlier songs, written during Wilson’s policy of neutrality, had featured mothers who didn’t want their boys to go to war. But after April 1917, sheet music almost invariably supported the war effort. Songs expressed straightforward appeals to men to enlist, portrayed women supporting the war effort from home, and warned unenlisted men not to seduce soldiers’ girlfriends. The covers of much sheet music also provide a rich visual source for popular illustrations.

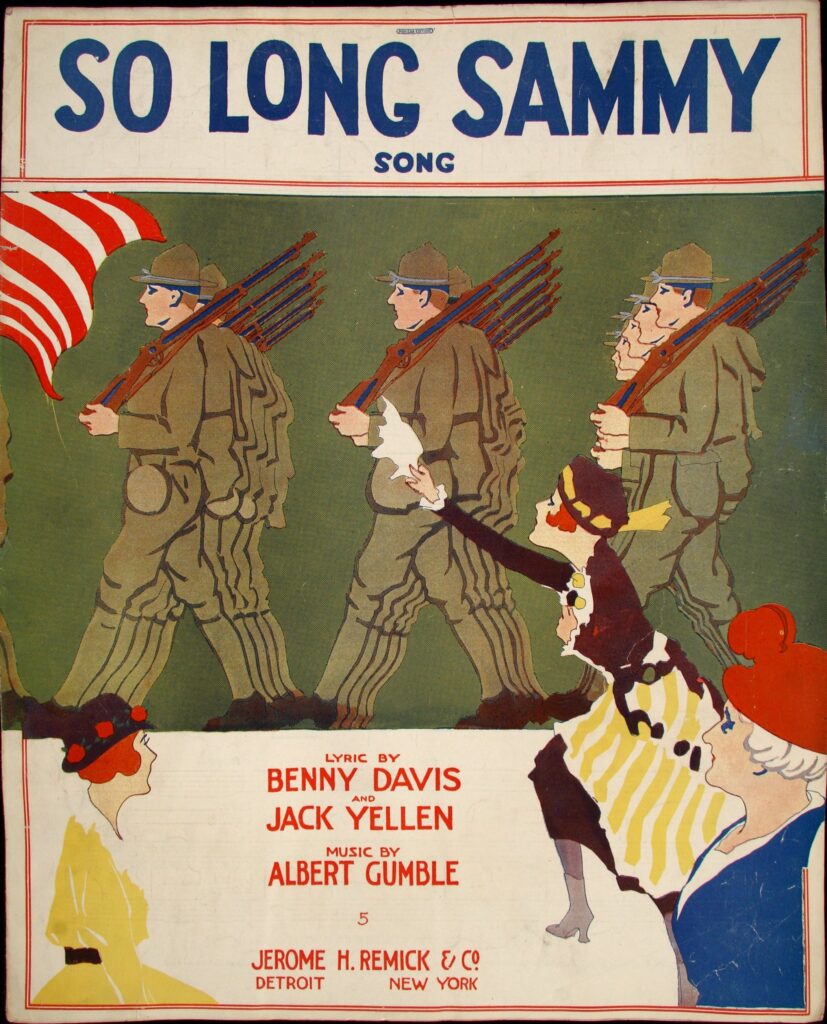

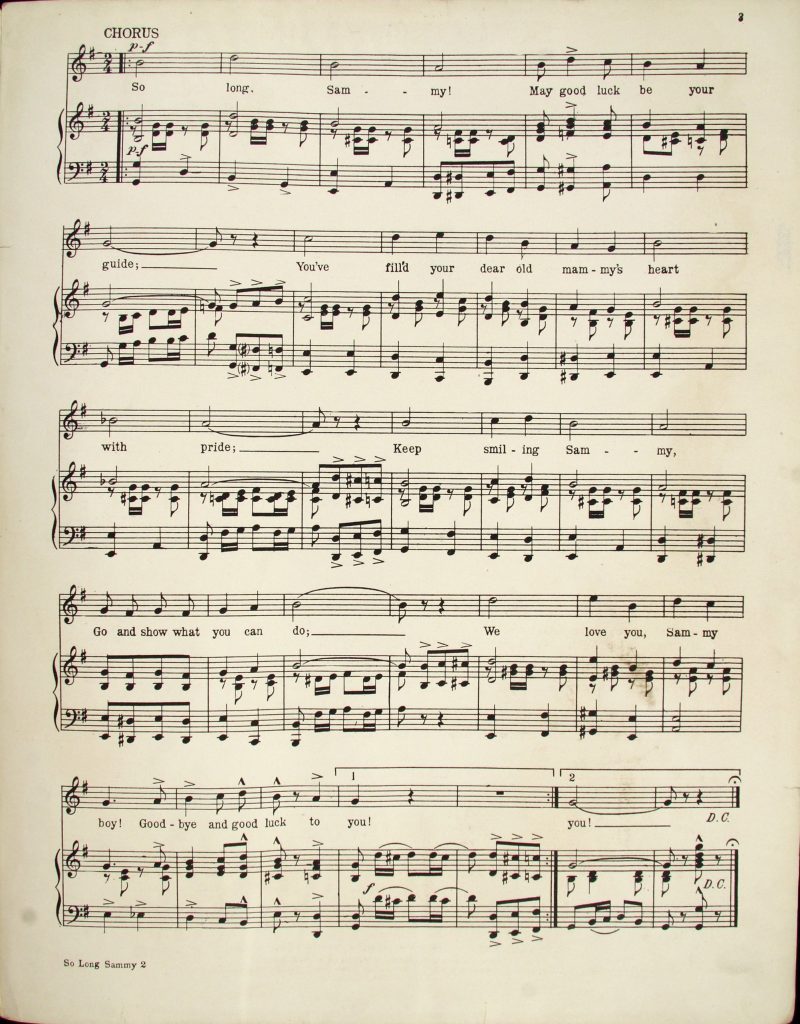

Selection: Benny Davis, Jack Yellen, and Albert Gumble, So Long Sammy (1917).

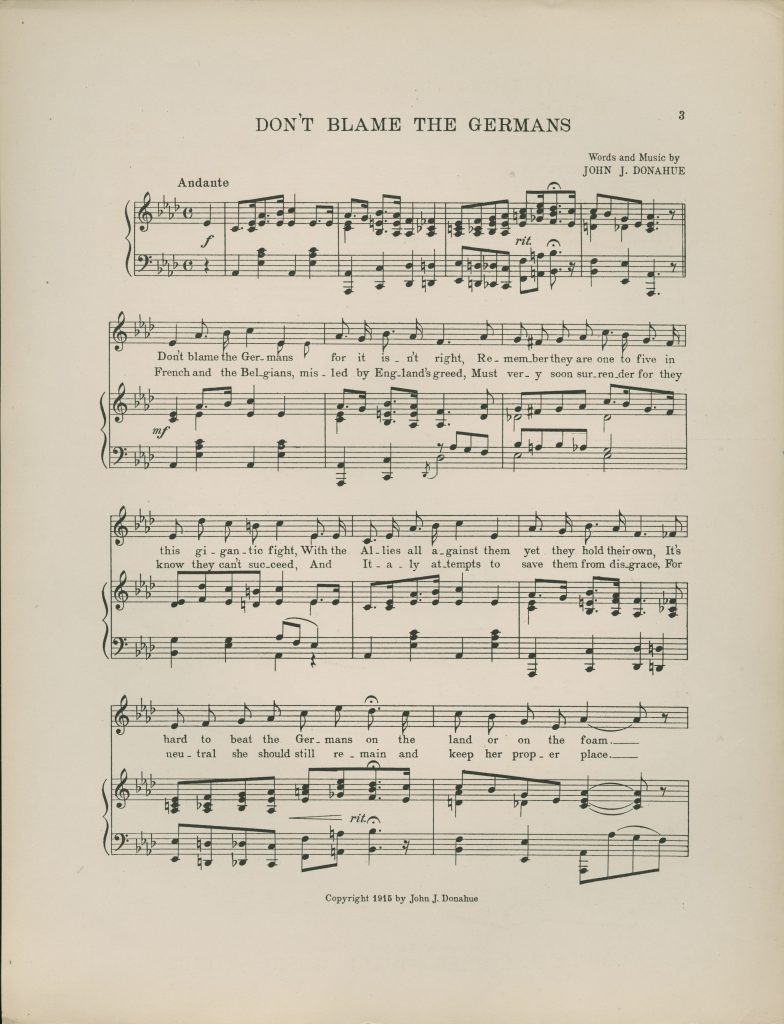

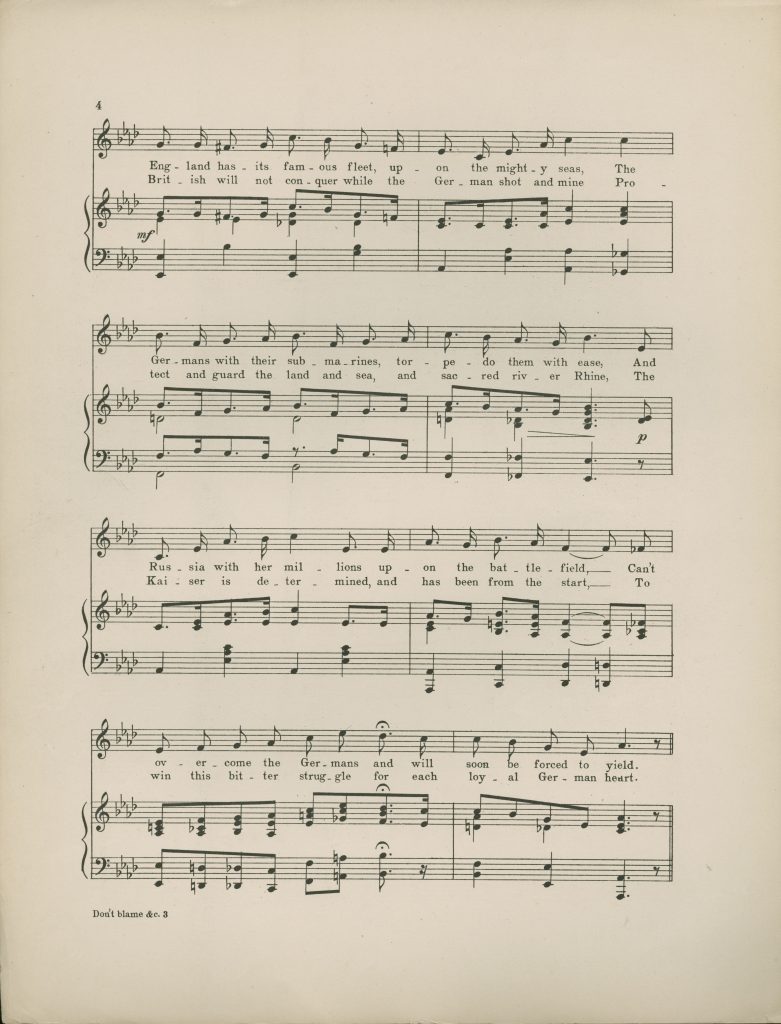

The sheet music presented in this section suggests some of the complexities of Americans’ responses to the war. When the war began in Europe, there were 8 million Americans of German or Austrian descent in the United States as well as 4.5 million Irish-Americans. These groups tended to sympathize with Germany or (in the case of the Irish) oppose Britain. They came under suspicion as the war progressed. As historian Patricia Junker notes, the former president, Theodore Roosevelt, and other early supporters of the Allies derided “hyphenated Americans,” insisting that residence in the United States meant “becoming an American and nothing else.”

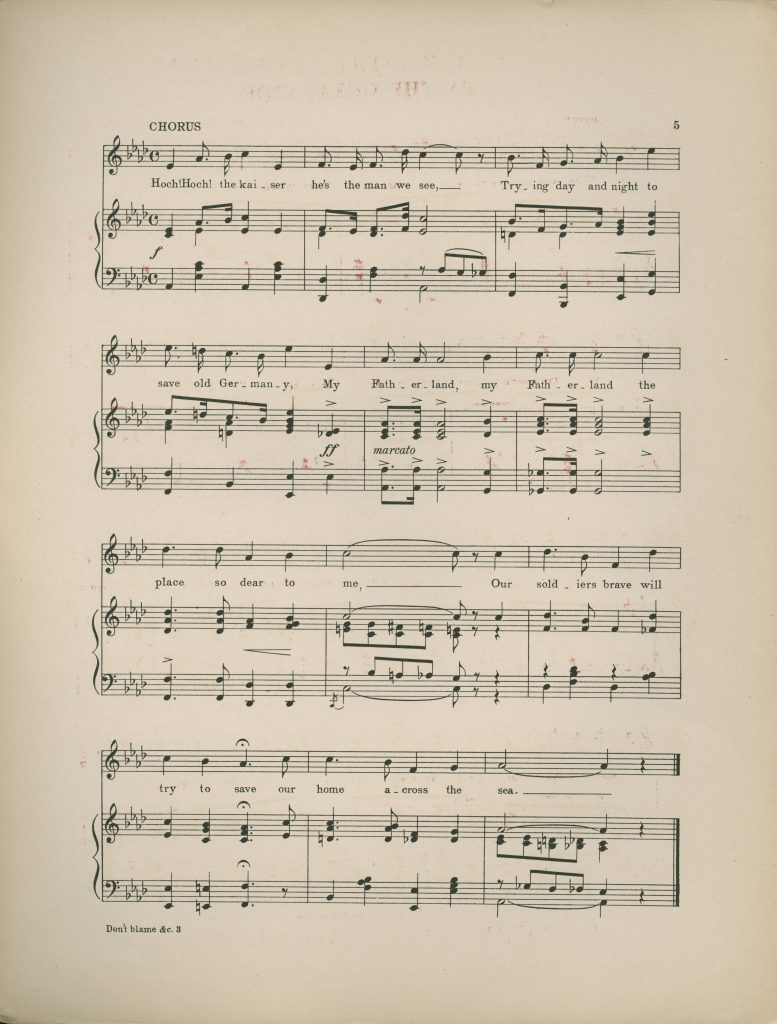

Selection: John J. Donahue, Don’t Blame the Germans (1915).

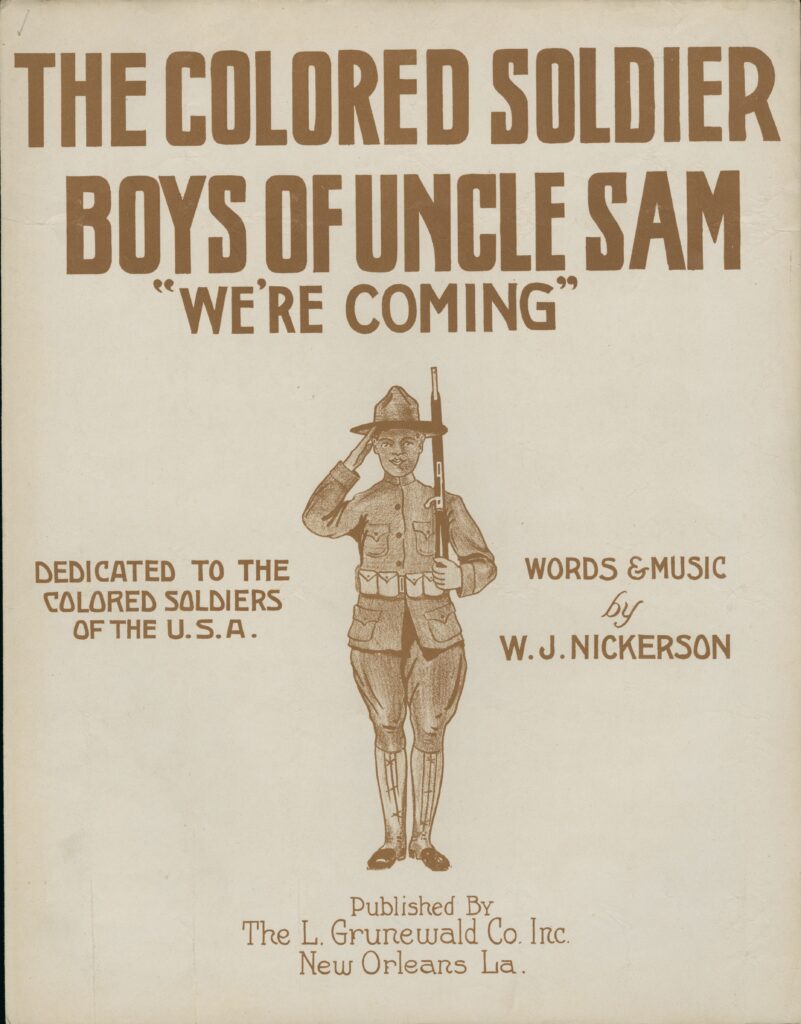

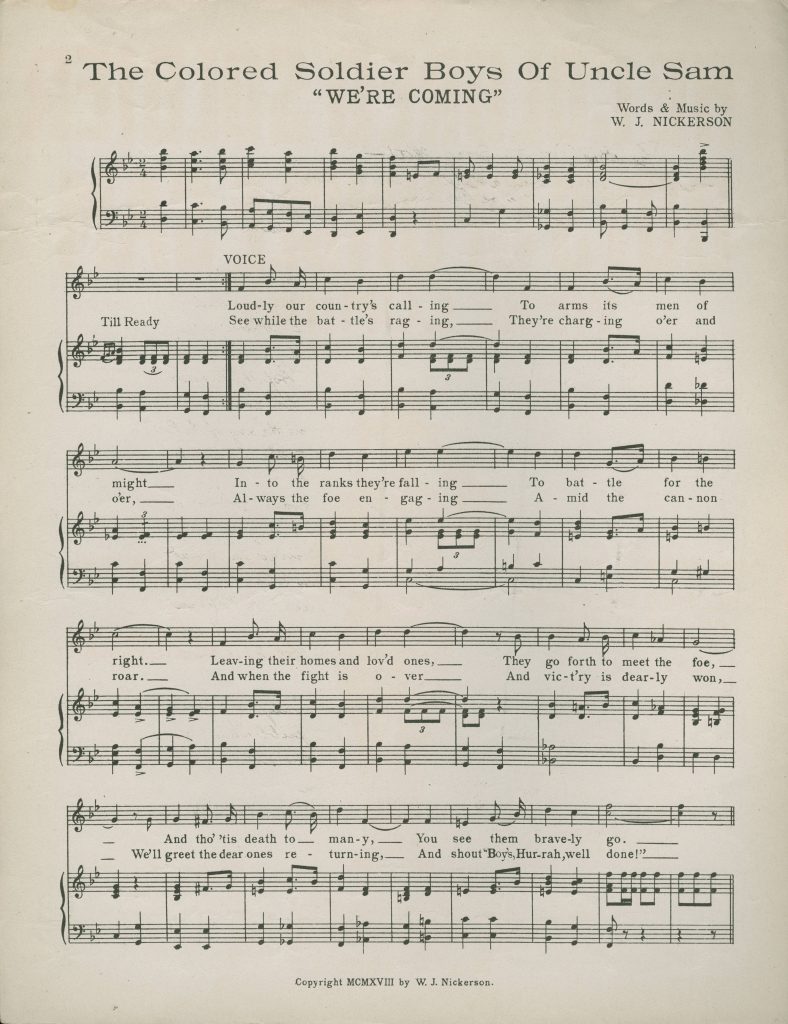

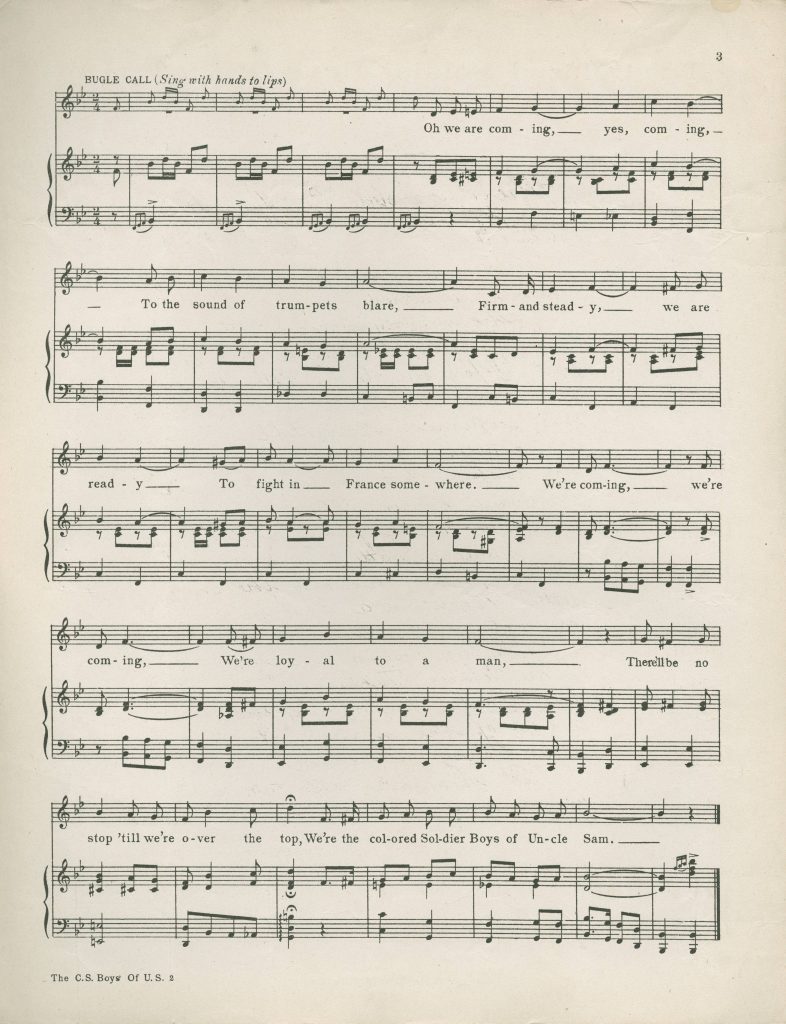

Many African Americans, including leaders such as W. E. B. DuBois, supported the war effort and appreciated the opportunities it created. Draft laws applied equally to black and white men, though African Americans served in segregated units that usually provided support rather than engaging in combat. Within the United States, the war effort created intense demand for labor in industry and transportation, stimulating the Great Migration of African Americans from the Southeast to cities in the North and West.

Selection: W. J. Nickerson, The Colored Soldier Boys of Uncle Sam (1918).

Questions to Consider

- Compare the song “Don’t Blame the Germans,” published in 1915, to the 1918 song “All Together.” How does each song make its appeal to support or oppose Germany? What kind of audience does each song seem to address? Why do you think “All Together” uses the archaic term Hun for German person? How do the references to voluntary food rations (at the bottom of the page) contribute to the song’s message?

- Describe the cover of “All Together.” How do the soldiers appear? What emotions do they express?

- How do “So Long Sammy” and “The Colored Soldier Boys” promote the war effort? What emotions do they solicit from their audiences? What role do women play in the war effort, as suggested by “So Long Sammy”? Why do you think the soldiers in “The Colored Soldier Boys” are specifically identified by their race? Does their race affect the song’s lyrics or patriotic message?

Advertising and the War Effort

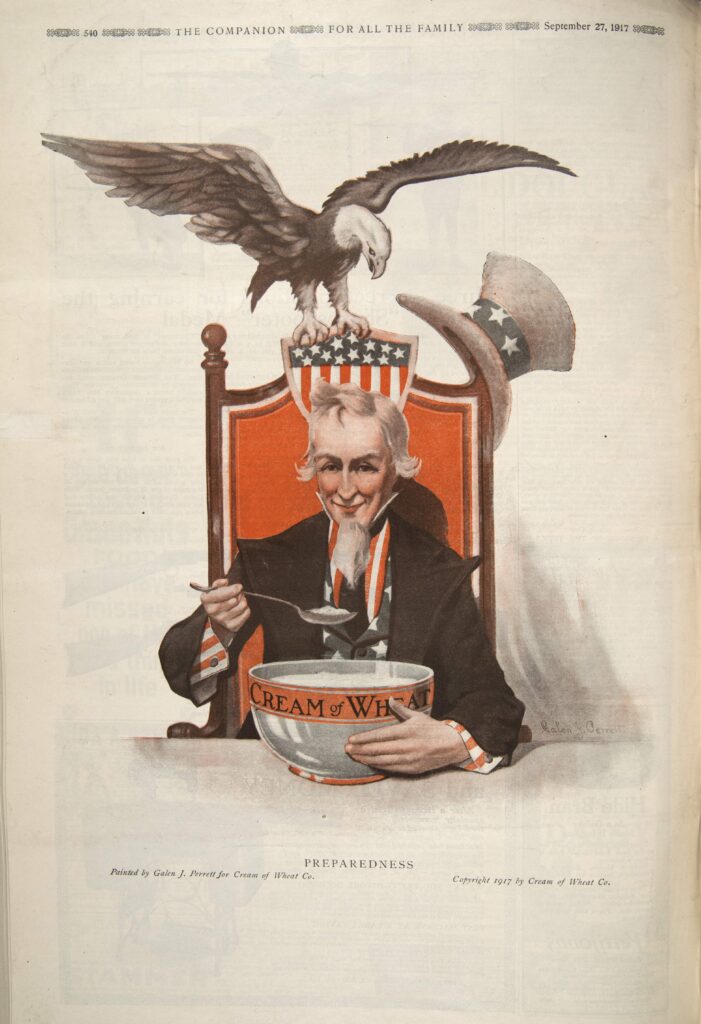

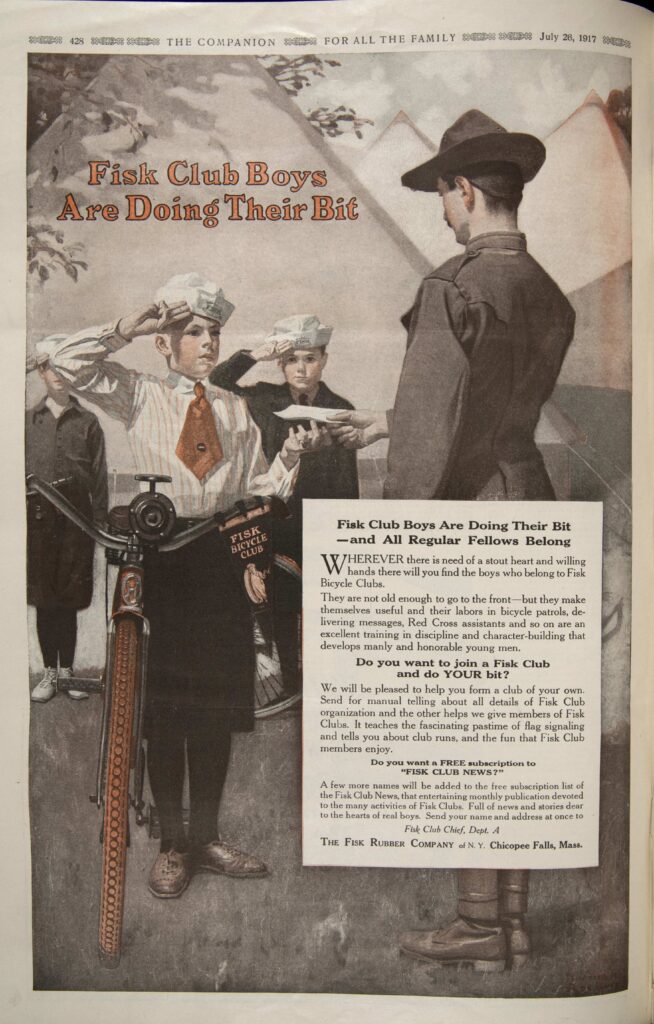

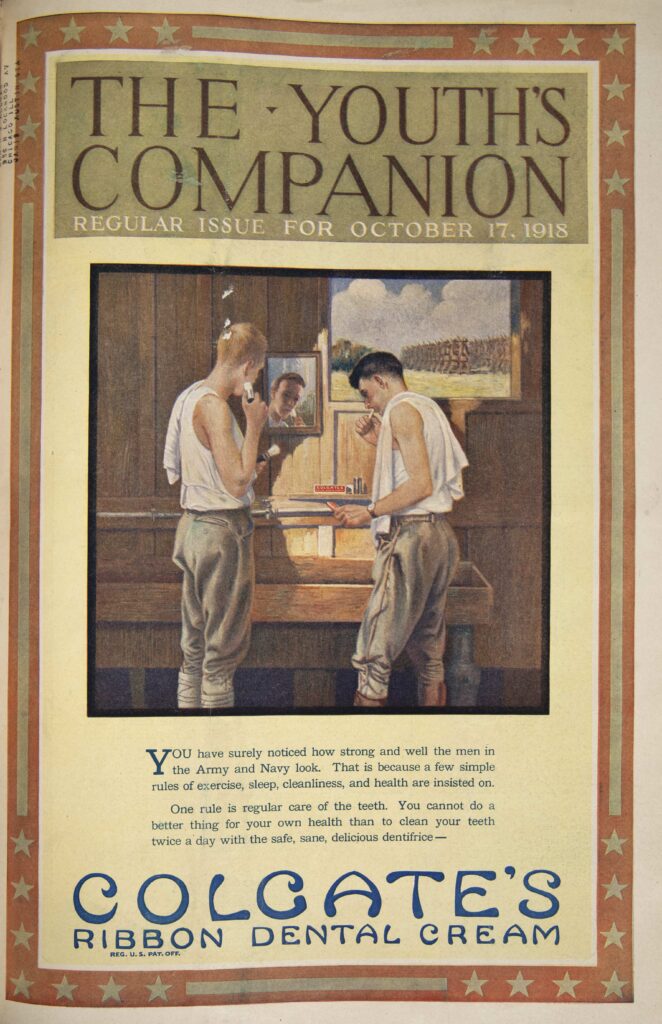

Many U.S. companies were quick to embrace the war effort by including patriotic messages in advertisements for their products. Representations of Uncle Sam and the bald eagle, for example, became pervasive in both government propaganda and ads. But popular art offers insight into cultural anxieties as well as ideals, as suggested by the attention to physical fitness in the ads below. As historian Jennifer Wingate explains, when the United States entered the war, “the army rejected as physically unfit for military service almost a third of the 2.5 million men between the ages of 21 and 30 who had been given physical examinations.” In response, the War Department developed training battalions to make men fit to fight, and government propaganda emphasized the health benefits of military training. The ads below all appeared in The Youth’s Companion, a magazine addressed to adults as well as children, that featured writers such as Mark Twain, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Jack London.

Questions to Consider

- Examine the Cream of Wheat “Preparedness” advertisement. How does the ad appropriate the Wilson administration’s rhetoric and iconography (or images)? How would you characterize Uncle Sam in this representation? Is he intimidating, friendly, comic? What do you think made him such an effective figure in the mobilization for war?

- How do the Fisk Bicycle Club and Colgate toothpaste ads evoke ideas of physical fitness and patriotism while marketing their products? In what ways do they address young men and boys, specifically?

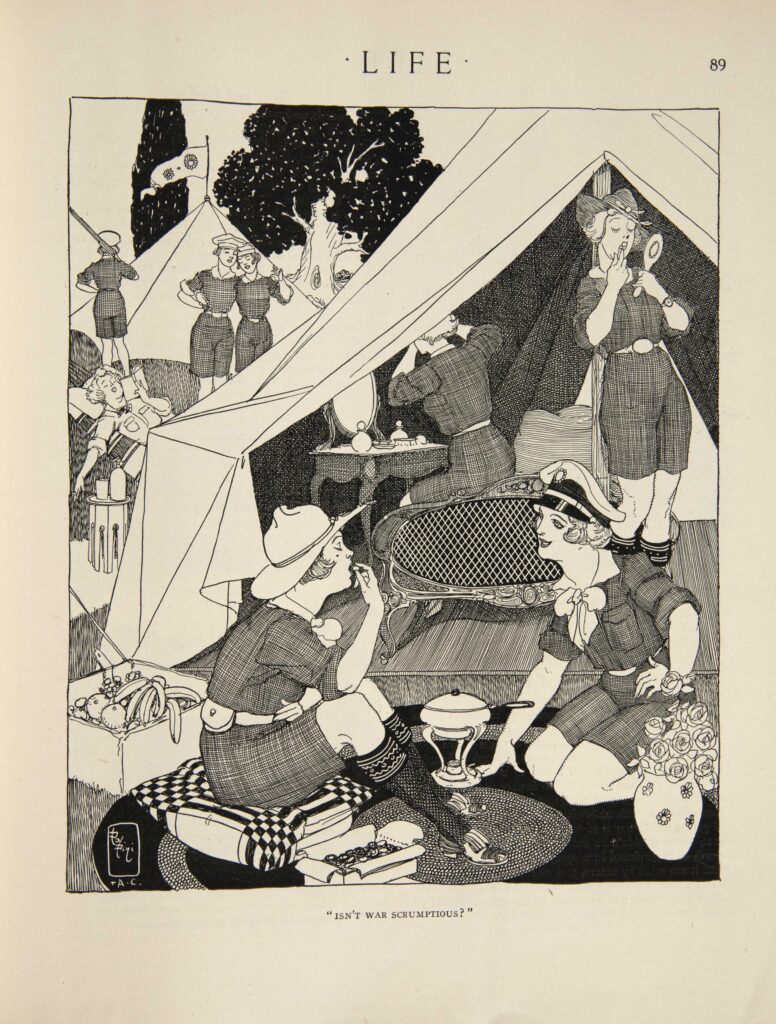

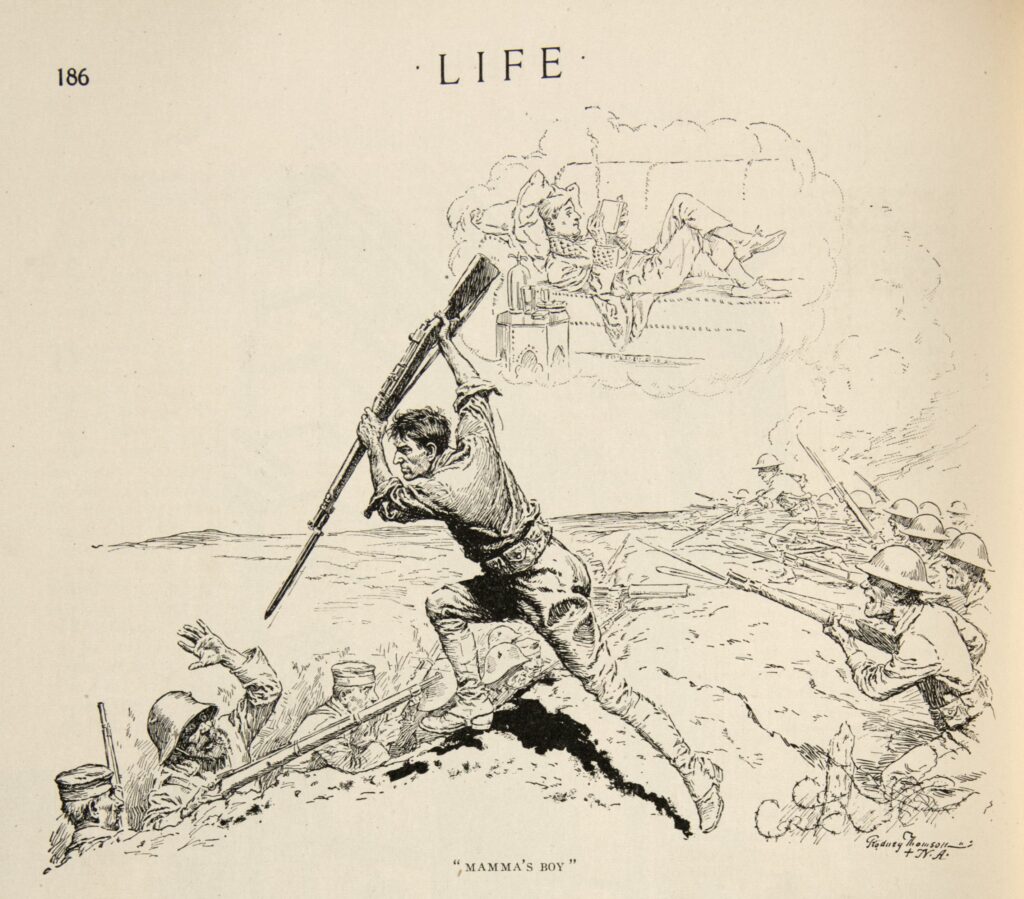

Gender and War Culture

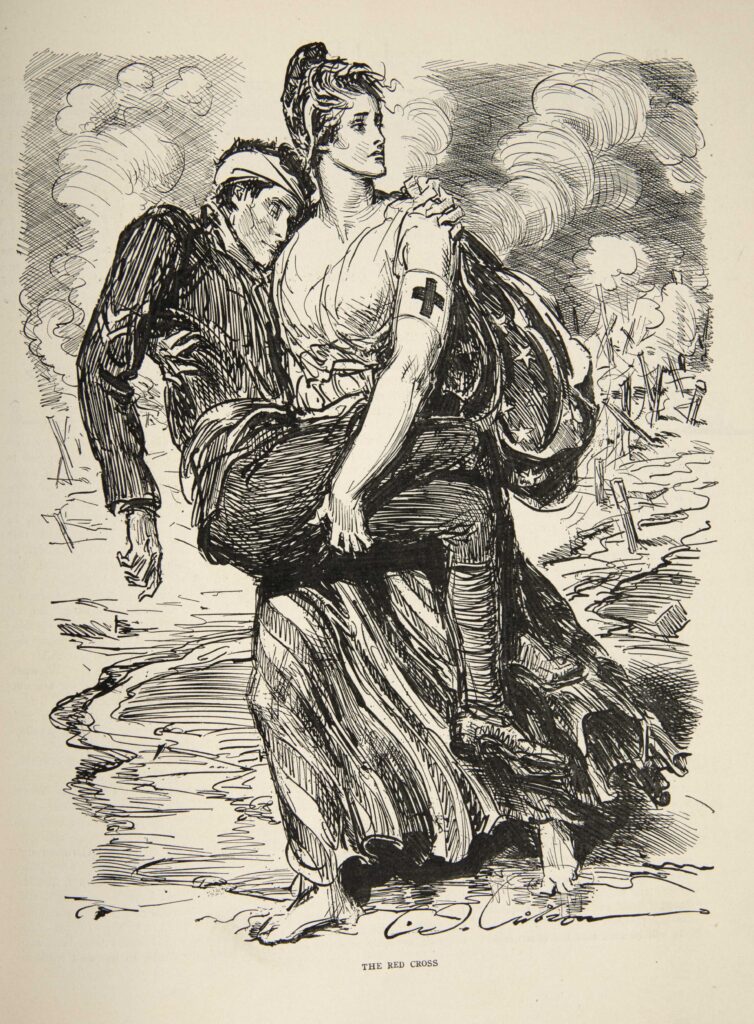

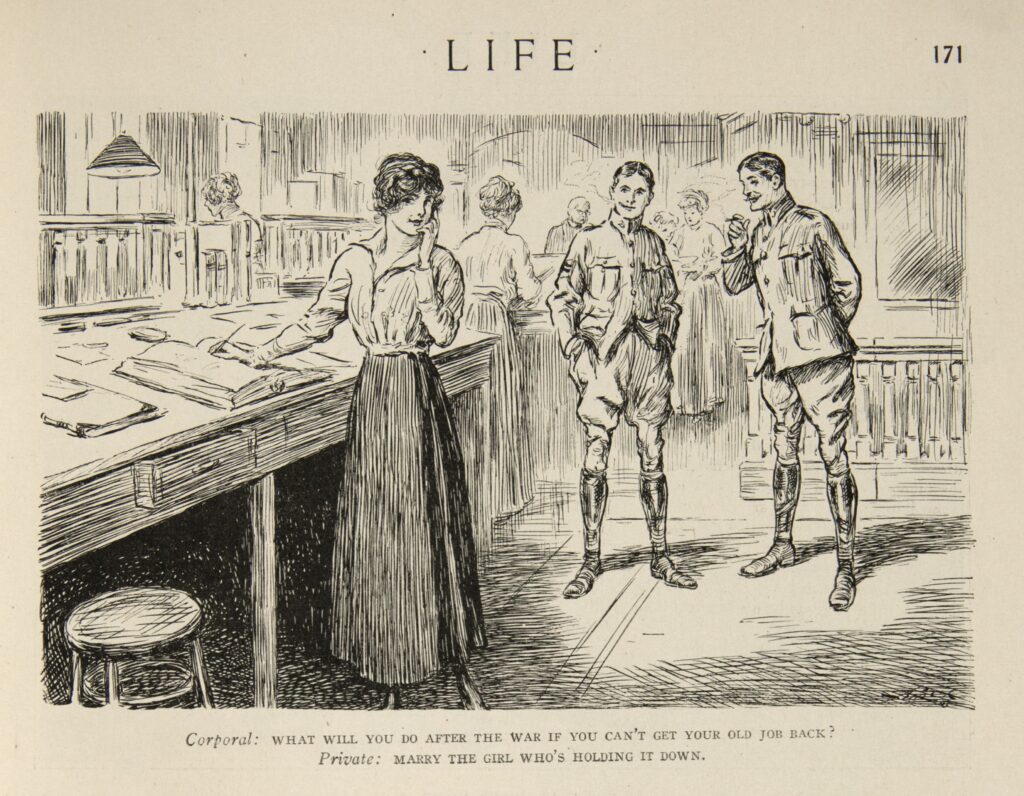

The U.S. entry into the war prompted a proliferation of images of soldiers and a new attention to ideas of manly heroism. Artists often portrayed American soldiers in aggressive poses, wielding bayonets as they charge over the tops of trenches in pursuit of retreating or cowering Germans. But the war also brought changes to women’s social roles and to popular perceptions of femininity. Some women went to Europe with service organizations, such as the Red Cross and the YMCA. Many more took jobs in the United States that had formerly been held by men and that would not have been open to women before the war.

These illustrations from Life, a widely read humorous magazine, sheds light on popular ambivalence about the war’s impact on gender roles.

Questions to Consider

- Examine the illustration captioned “Isn’t war scrumptious?” How does this artist portray women who have joined service organizations in Europe?

- Compare the “Scrumptious” illustration to the drawing entitled “The Red Cross.” Is the woman in the second drawing intended to be real or symbolic? What feelings does the drawing evoke? Why do you think the artist chose to portray a woman rather than a man rescuing the soldier?

- Analyze the “What will you do…?” illustration as a response to women’s increased participation in the workforce. How does this drawing respond to or alleviate concerns about the consequences of these workplace changes?

- Consider the illustration “Mamma’s Boy.” How would you describe the soldier in the foreground, leaping over the edge of the trench? What is his relationship to the reclining man in the cloud? Why is the drawing titled “Mamma’s Boy”? What is the artist trying to demonstrate by juxtaposing the man at home and the man at war?

Criticizing the War Effort

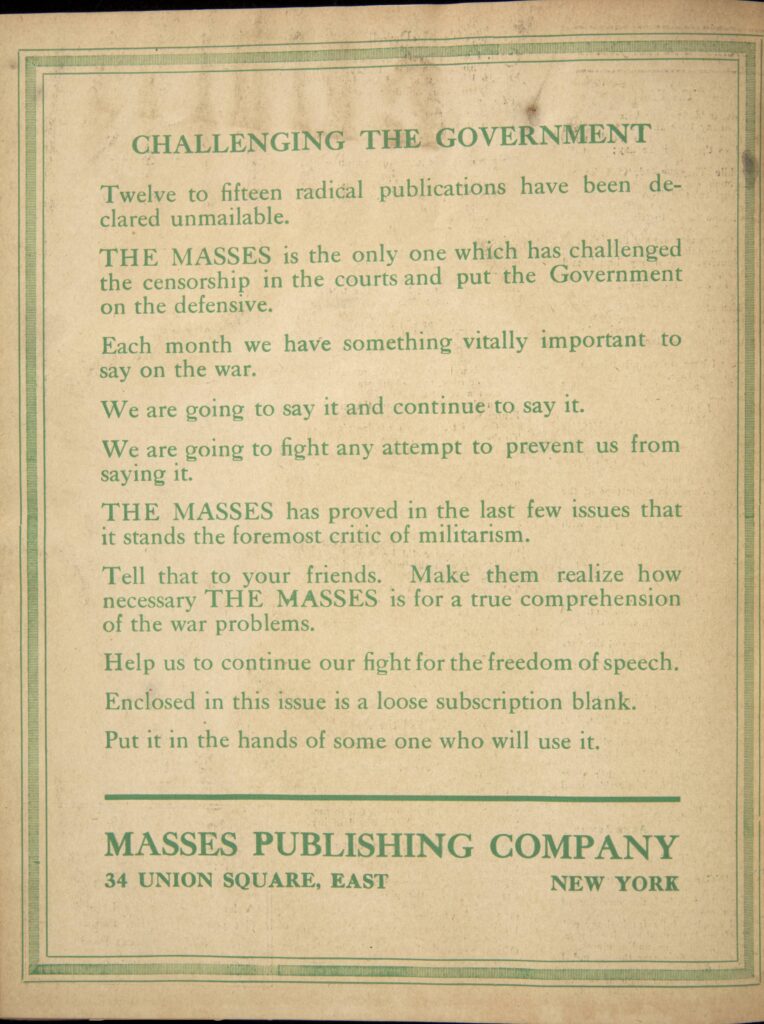

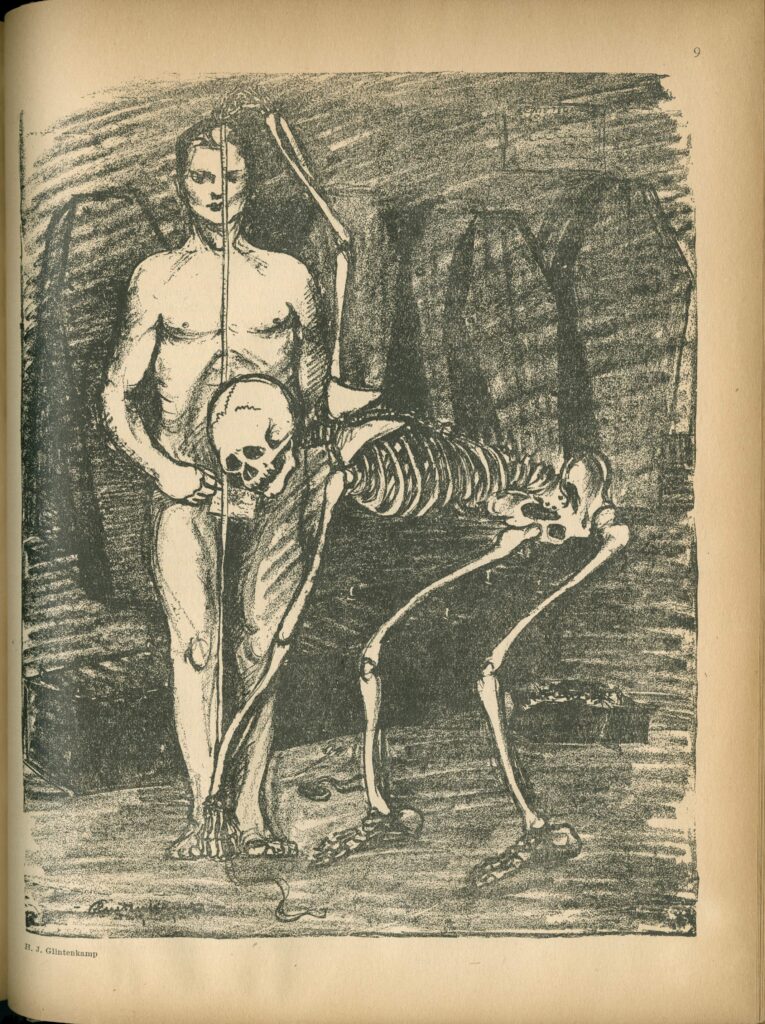

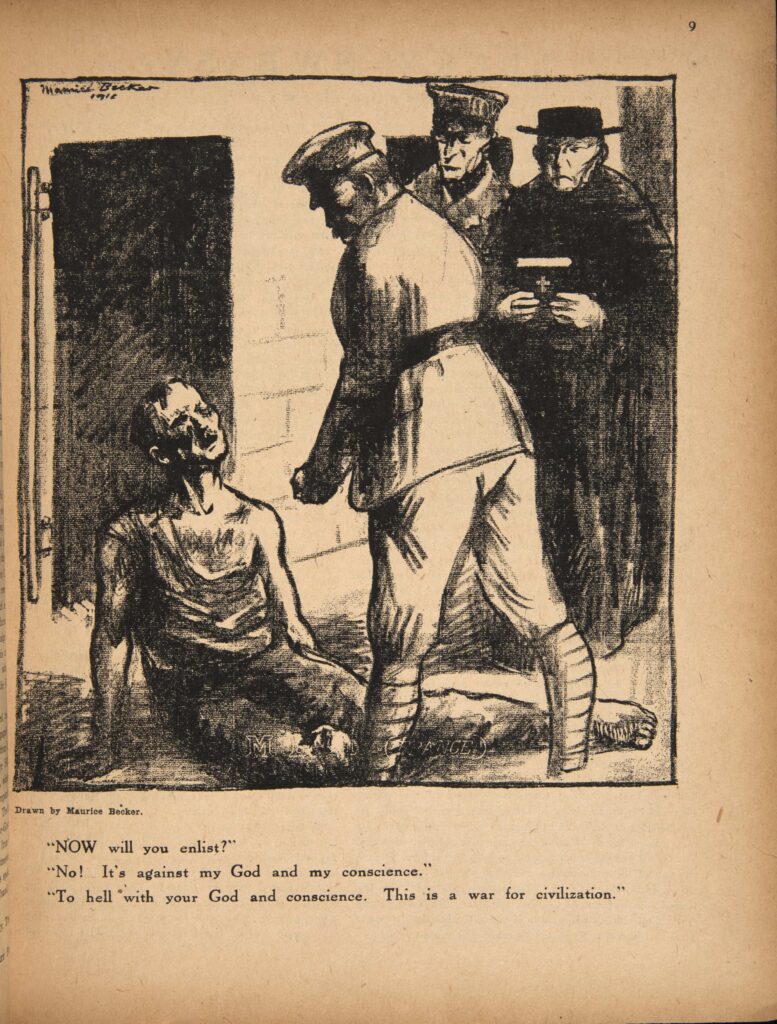

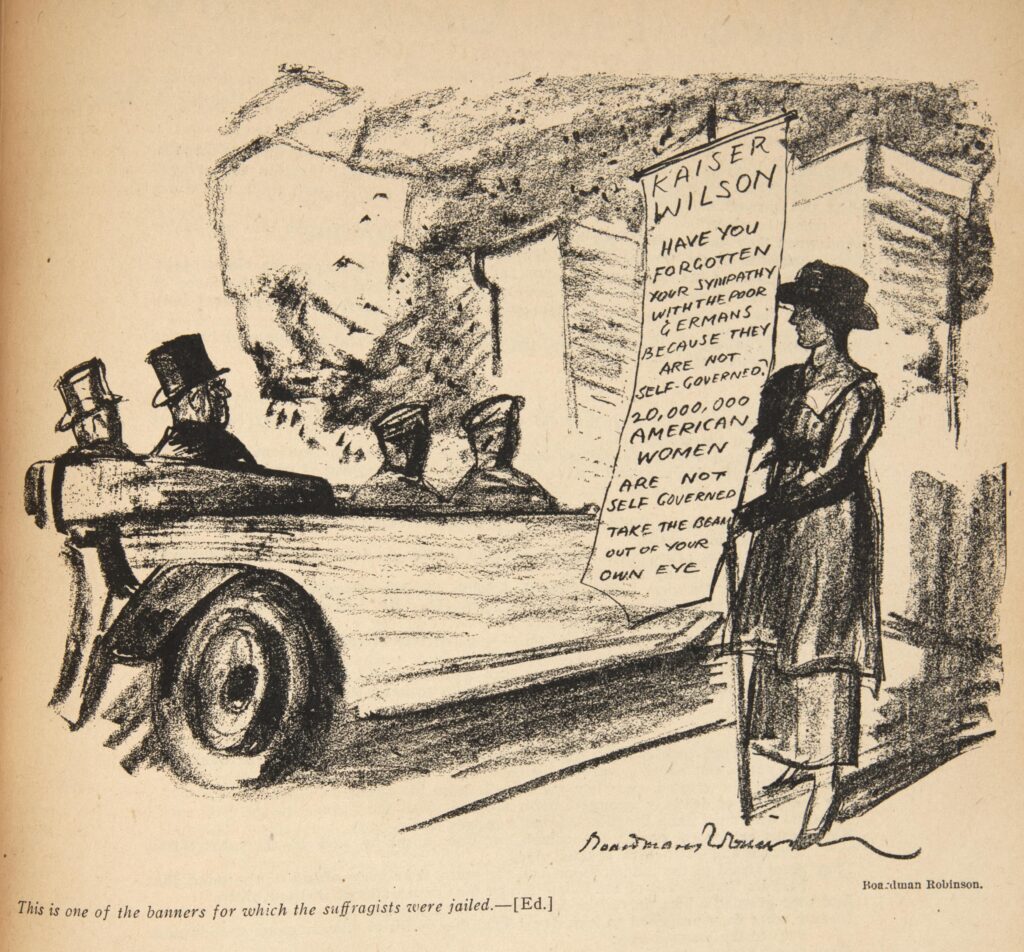

The Masses was a socialist monthly magazine that featured vivid illustrations and political cartoons alongside poetry, fiction, and editorials. It was produced by a group of radical artists and activists in Greenwich Village, New York City. The Masses’ artists and writers expressed strong and consistent opposition to the war, which they argued sacrificed workingmen’s lives to serve the interests of wealthy capitalists. They supported other radical causes as well, such as labor strikes, women’s suffrage, and Margaret Sanger’s birth control crusade.

The magazine ran from 1911 to 1917, when federal prosecutors charged its editors with violating the Espionage Act of 1917. This act, along with the Sedition Act of 1918, imposed fines and jail sentences on people who aided the enemy, interfered in military recruitment, or spoke against the war effort. Two trials resulted in hung juries, and the editors of the Masses went on to found other radical publications.

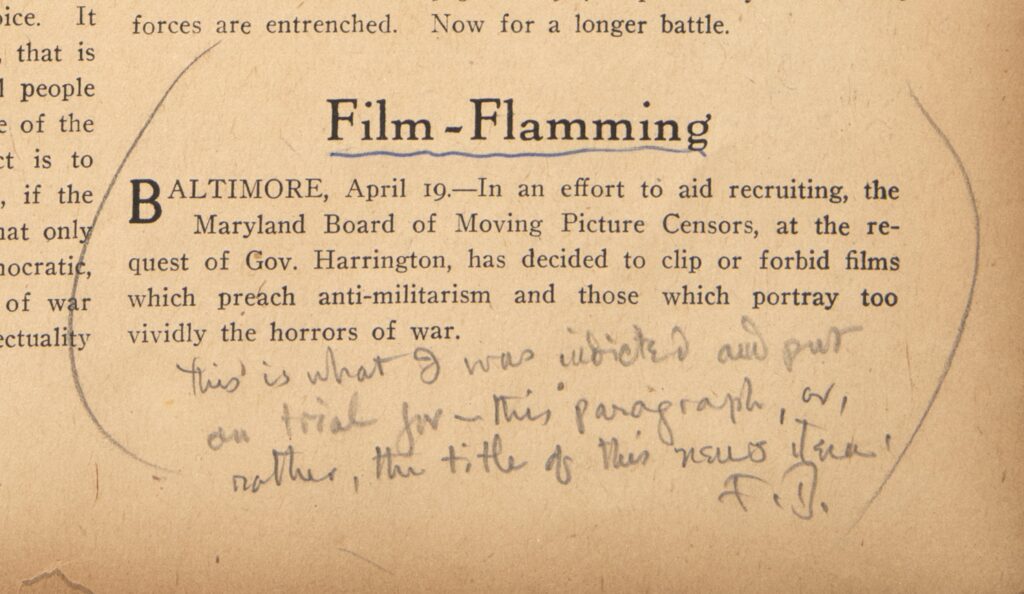

Transcription of Floyd Dell’s note:

This is what I was indicted and put on trial for — This paragraph or, rather, the title of this news item.

F.D.

This selection of pieces from the Masses includes a handwritten note by Floyd Dell, an author and editor at the magazine, concerning wartime censorship. Dell’s title, “Film-flamming,” refers to the flamethrower, a portable weapon, consisting of a backpack and a gun, that projects a stream of ignited, flammable liquid. Flamethrowers were first used by Germany in 1915 against French and British trenches. (Many other countries, including the United States, adopted them in World War II.)

Questions to Consider

- Examine the illustrations by Maurice Becker and Henry Glintenkamp. On what grounds does each one criticize the government’s recruitment efforts?

- Why would the government attempt to censor the Masses’ illustrations and commentary?

- How does the magazine respond to the censorship through the back cover commentary and Dell’s piece on “film-flamming”? What connections does it suggest between “militarism” and censorship?

- The Supreme Court upheld the Espionage and Sedition Acts in Schenk v United States (1919), arguing that when there is “a clear and present danger” to national interest, the government may suppress free speech. The laws were subsequently modified and many critics regard them as violating the Constitution. Do you believe such censorship is justified during wartime?

- Examine Boardman Robinson’s illustration of a suffragist. How does the illustration connect opposition to the war to the cause of women’s right to vote? (Note: The suffragist’s sign plays on the title of the German monarch, Kaiser Wilhelm II.)

Maps of the War

These two maps, one providing the perspective of a soldier and the other from the victorious, American perspective, offer starkly different perspectives on the Western Front.

Popular Music and the War

Sheet music played an important role in popular culture during the war and was used to help promote the war effort.

War Advertisements

As these images from The Youth’s Companion demonstrate, many U.S. companies supported the war effort by including patriotic messages in advertisements for their products.

Gender and the War

These illustrations from Life Magazine capture representations of soldiers and women who contributed to the war effort and the impact of the war on traditional gender roles.

Criticisms of the War

These pieces from the Masses include illustrations and commentary criticizing the war, including wartime censorship, the government’s recruitment efforts, and the horrors of war.

Further Reading

Junker, Patricia. “Childe Hassam, Marsden Hartley, and the Spirit of 1916.” American Art 24 (Fall 2010): 26–51.

Lubin, David. “Losing Sight: War, Authority, and Blindness in British and American Visual Cultures, 1914–22.” In Anglo-American: Artistic Exchange between Britain and the USA, edited by David Peters Corbett and Sarah Monks. 2012. 175–195.

Morris, Evan. The Word Detective. February 16, 2005. http://www.word-detective.com/021605.html.

Wingate, Jennifer. “Over the Top: The Doughboy in World War I Memorials and Visual Culture.” American Art 19 (Summer 2005): 27–47.