Introduction

Women have always worked outside of the home. They have done so for a variety of reasons, such as to maintain their own independence, have a comfortable life, contribute to society, assist in providing for their families, and support their families as the sole provider. Some women have had a variety of choices in their work lives, while others had very little to no choice at all. By the mid-twentieth century, female employees had become common enough in the United States that people started to comment on, congratulate, and criticize them for seeking outside employment. Some employers, employees, and members of society did not approve of or feel comfortable with women working outside of the home, which led to discrimination in the workplace. While every woman’s experience was unique, many were exposed to sexism, racism, and ageism—terms for treating someone differently because of their sex, race, and age—as working women. Characteristics such as the color of a woman’s skin, her outward appearance, level of education, skill, marital status, and economic status played a role in whether a woman worked at all, and if so, where she worked and what type of job she had. Social and economic factors, especially during wartime, had the greatest effect on the opportunities available to women in the workforce. The twentieth century saw yearly fluctuations among the numbers of working women; however, from 1920 to 1950, those numbers continued to rise steadily with each decade.

In an effort to recognize women as an essential part of the workforce, scholars, professionals, organizations, and media outlets produced an array of literature about the lives of working women. Women who had already established their place in the working world wrote books highlighting their experiences and outlining career options available to young ladies new to the workforce. The Federal Government Census Bureau and organizations such as the National School of Business Science for Women and Smith College Council on Industrial Studies published reports and articles on the number of women in the workforce, the types of work they did, and the obstacles and accomplishments they experienced while on the job. Between 1939 and 1952, the Public Affairs Committee published pamphlets discussing what motivated women to work and the complications that working wives and mothers faced, giving insight into the personal lives of working women both in and outside of the workplace. In the 1940s, magazines like Life and Mademoiselle published articles and books about and for women workers, providing a glimpse into what life was really like for the ‘career gal’. All of these materials not only supported women in the workforce, but also aimed to educate the public on this topic. These specific resources held at the Newberry Library, along with many others, promoted a woman’s right to work in order to ensure that women continued to participate in the workforce.

As you view the documents below, think about the working women that you know. What have they struggled with, and what have they accomplished? How do their experiences relate to the women in these sources?

Questions to Consider:

- Why do women work?

- What factors determine the type of job a woman might have had in the mid-twentieth century?

- What do these documents reveal about the differences between men’s and women’s experiences in the U.S. workforce?

- What gender issues exist in the workforce today? Do you see any of those issues reflected in these documents?

Working Women

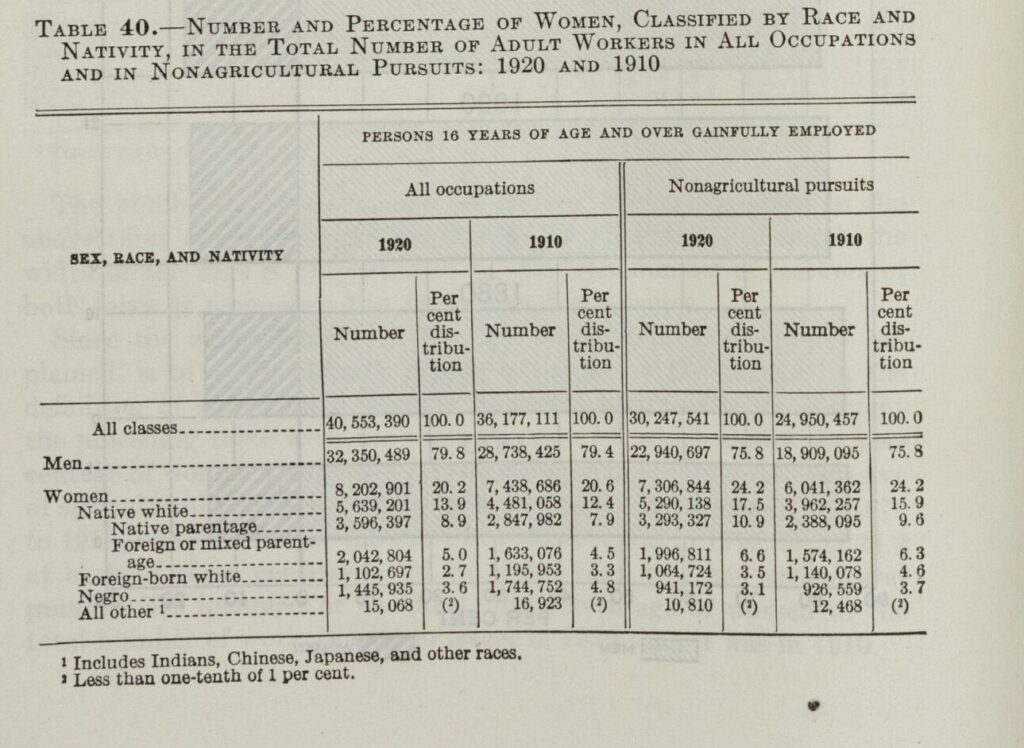

In 1929 the United States Bureau of the Census published a report called Women in Gainful Occupations, 1870 to 1920: A Study of the Trend of Recent Changes in the Numbers, Occupational Distribution, and Family Relationship of Women Reported in the Census as Following a Gainful Occupation,compiled by Joseph A. Hill. The report used data gathered from the 1920 census and compared it to information from the previous fifty years of census data to provide statistics and analyses about women in the workforce. In his Forward to the report, Hill recognized that the Industrial Revolution had brought about “an increasing need for- and opportunity for- the participation of women in economic activities” and that “the women’s place to-day is no longer in the home” (xv). The report included the range of women’s occupations; comparisons by decade, race, and geographic location; age at obtaining gainful employment; and family relationships. It also compared the number of women with the number of men in the workforce. Because it only analyzed data from the census, however, this report was unable to provide information regarding wages, hours, job conditions, or the quality of the work performed.

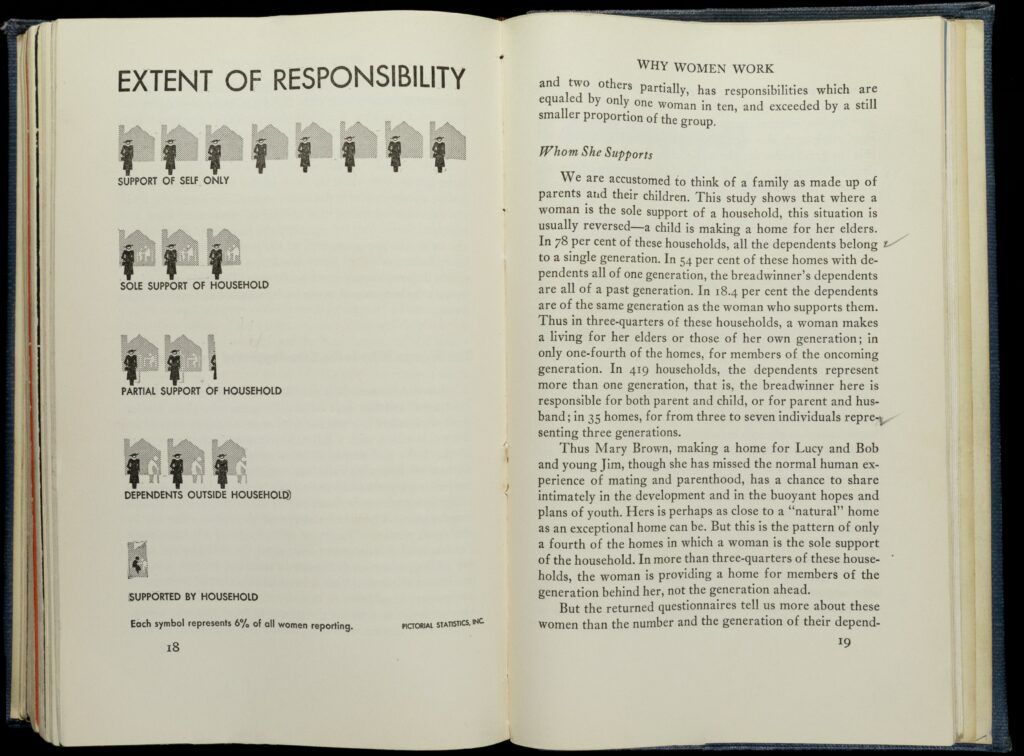

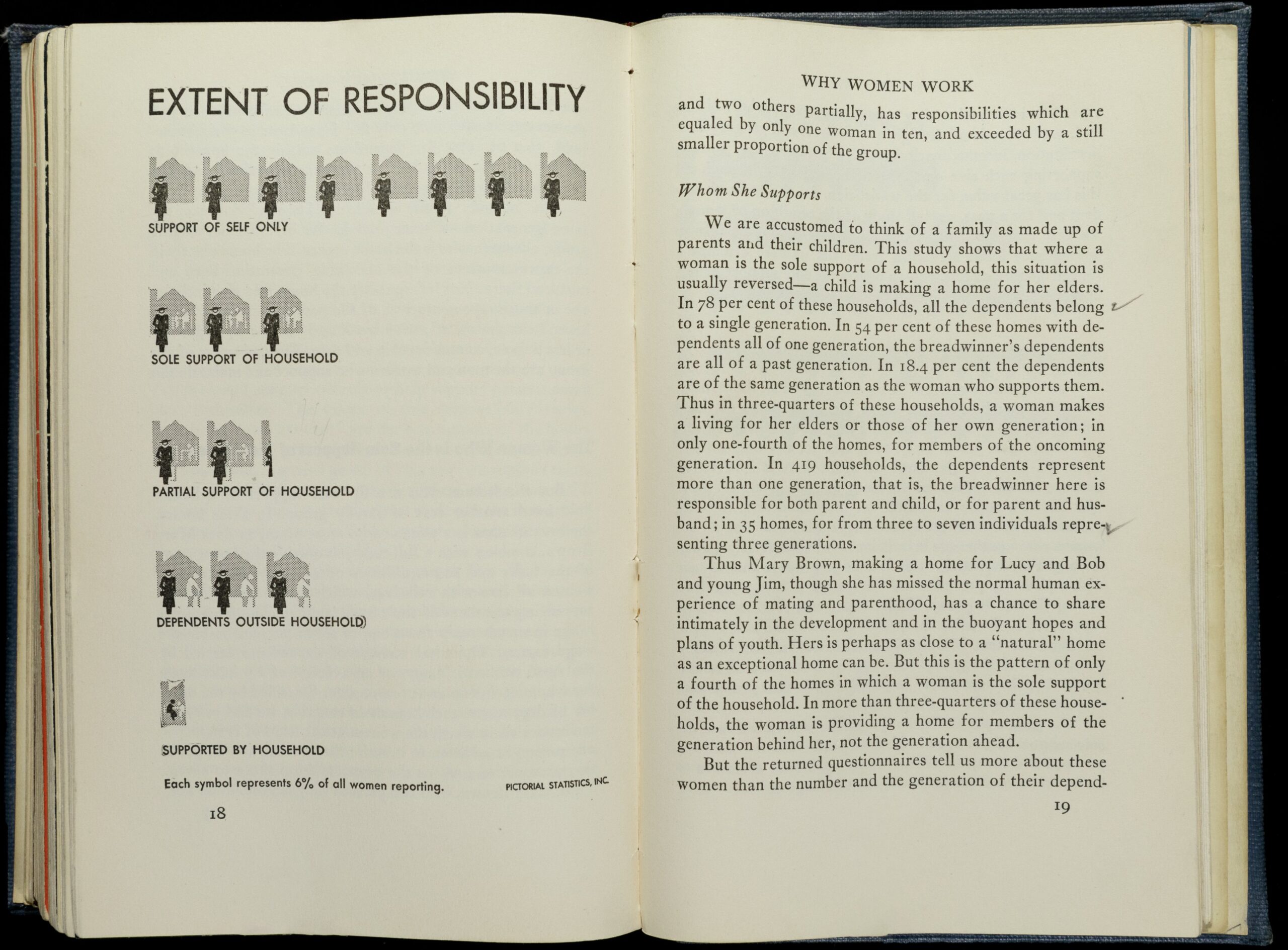

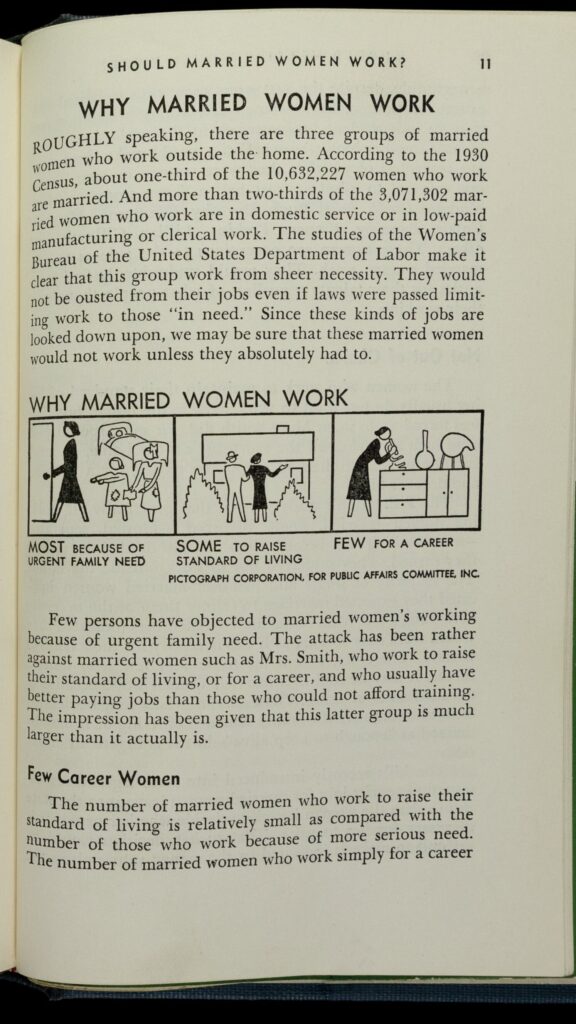

A decade later, in 1939, the Public Affairs Committee published a pamphlet entitled Why Women Work. The committee published over 200 pamphlets from 1936 to 1986 on topics such as war, medicine, policy, discrimination and inequality, and much more. The price and format of the pamphlets made them easily affordable and accessible to the general public. This pamphlet used information from the 1930 census as well as the answers to a questionnaire sent out by the National Federation of Business and Professional Women’s Clubs to 12,043 professional women workers. (In this case, professional work is anything that is not agricultural, domestic, or factory work.) This pamphlet not only included facts and data, similar to the Hill report, but also provided personal stories from working women, thereby offering insight that the Hill report did not. Why Women Work focused primarily on how much money women earned and whether or not it was enough for them to support themselves and, if necessary, their families. The pamphlet made a point to indicate that families could include children and husbands as well as extended family members that may or may not live in the same household. Why Women Work disproved the idea that only men had families to support and therefore needed to make more money than women, as stated in the summary of the pamphlet.

Both of these works were important documents because they legitimized working women as a demographic worthy of study and recognized the contributions working women were making to the U.S. economy.

Questions to Consider:

- Why do you think Table 40 separates women by race? Why might race and ethnicity be a factor in the number of women working?

- Table 41 lists the main occupations that women and men were engaged in. Which jobs have a higher percentage of women workers in 1920 as compared to 1910?

- What is the difference between each category of women illustrated in the “Extent of Responsibility” image? Why might each group need to or choose to work?

Advice, Encouragement, and Support

Most, if not all, women faced sexism in the workplace. This means they were treated differently because of their sex. As a woman it could be difficult to get a job, and once she had one, she had to behave properly in order to keep it. Luckily, there were a variety of resources to look to for help. An Outline of Careers for Women: A Practical Guide to Achievement, compiled and edited by Doris E. Fleischman and published in 1928, offered a collection of essays written by professional women in a variety of occupations. As the title reflects, these essays laid out the range of occupations open to women, and offered advice on how to break into and become successful in certain vocational fields. Edith Mae Cummings’s Pots, Pans and Millions: A Study of Woman’s Right to be in Business, Her Proclivities and Capacity for Success explored her personal story as a widow forced to find work to support her two children and ill mother after the sudden death of her husband. Not only did this book tell Cummings’s story as a working woman, but it followed her rise through the ranks of the business world, starting from a machine shop worker during World War I to becoming the president of her own company. The book, published by the National School of Business Science for Women, came out in 1929 and was dedicated to “all women ambitious to serve humanity and help make this a better world.”

Selection: Edith Mae Cummings, “Introduction,” in Pots, Pans, Millions: A Study of Women’s Right to be in Business, Her Proclivities and Capacity for Success (1929), xi-xiii.

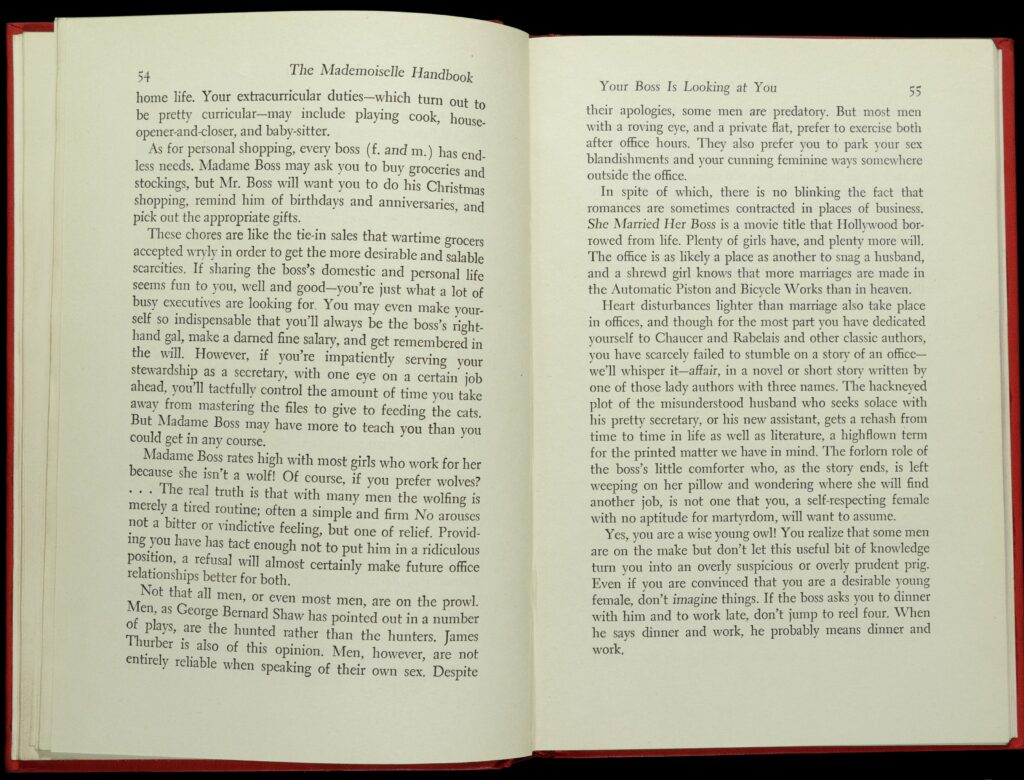

Many women encountered double standards in the workplace regarding their age and appearance. Some employers viewed older women as allegedly more mature and dependable than their younger counterparts. Other employers preferred to hire younger and unattached (single) employees, which could lead to scrutiny from other female colleagues and unwanted advances from male coworkers. Working women had to be cautious about their own appearance and behavior, as well as that of their employers and male colleagues, in order to maintain a pleasant and professional workspace, as shown in The Mademoiselle Handbook for the Girl with a Job and a Future. This book was published in 1946 and written by Mary Hamman and the editors of Mademoiselle, a women’s magazine that ran from 1935 to 2001. It used a light-hearted and sometimes whimsical tone to deliver a very serious message. The Handbook offered advice on how to look, dress, and behave so the working girl could “fit in,” while seeming to place all the responsibility for a pleasant and professional workspace, as well as a successful career, on women.

Selection: “Your Boss is Looking at You,” The Mademoiselle Handbook for the Girl with a Job and a Future (1944), 54-55.

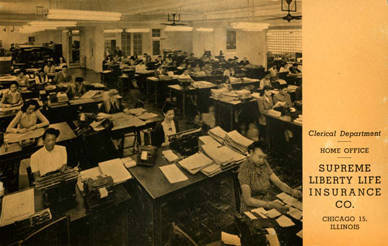

While many women had to navigate how to fit in with their employers and colleagues in the workplace, this was often more difficult for women of color. Racism was very much alive in the mid-twentieth century, and many white-owned businesses and white employers preferred to hire white folks over people of color. Later, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination by an employer based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin; however, it did not stop racism in the workplace. Women of color did not have as many job opportunities open to them as white women did and in some cases were forced to take on work that was beneath their education and skill level, such as domestic service. Women of color were also not always paid as much as white women, even when they had the same education and skill level as their white counterparts. It was also possible (and is still true today) that women of color were the only or one of few people of color at that organization. Businesses run by people of color offered a greater variety of job opportunities for women of color. For instance, African American women had better luck finding jobs with African American-owned businesses, such as the Supreme Liberty Insurance Company in Chicago. Supreme Liberty offered better policies for the clients and more opportunities for those looking for work in the African American community. Starting a career could be daunting for women, but as these examples demonstrate, resources were available to encourage and advocate for women’s success in the workplace.

Questions to Consider:

- Based on this excerpt of the railroading chapter from An Outline of Careers for Women, do you think this book might have been useful to young girls and women thinking about entering the workforce? Why or why not?

- How does the advice from these two pages from the Mademoiselle Handbook help you identify problems faced by working women in this period?

Working Women in Factories

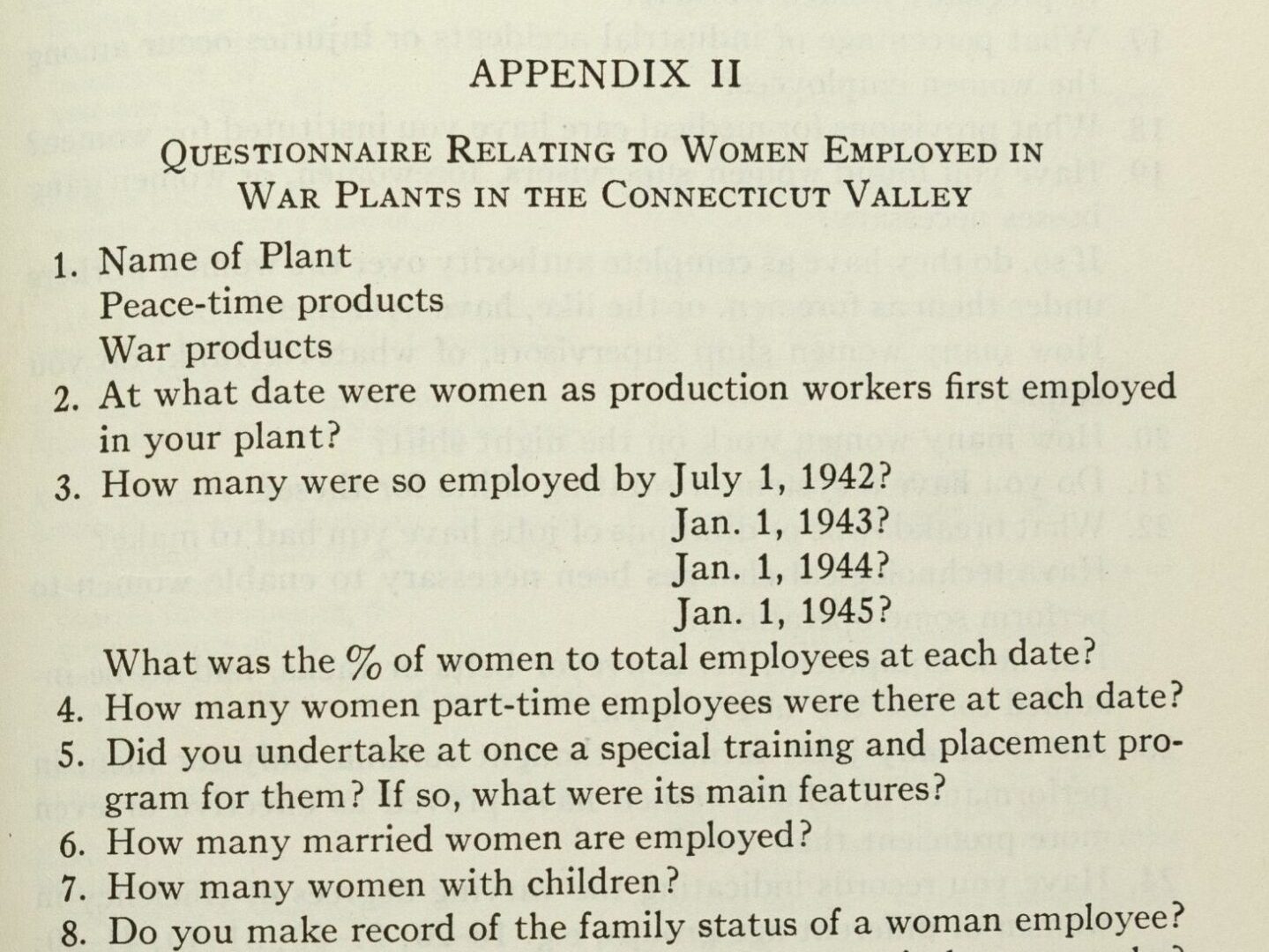

Times of war opened a floodgate of job opportunities for women in the first half of the twentieth century, creating more jobs in different types of work as many men went off to fight. During World Wars I and II, employers needed workers to keep their factories and plants running, and hired women to do so, as documented in Constance Green’s article The Role of Women as Production Workers in War Plants in the Connecticut Valley, published in 1946. The article studied all aspects of the life of women workers in several Connecticut plants during World War II. The article captured the perspectives of both the women workers and their employers, and highlighted their success in performing what had been considered “men’s work” in the factories and the essential part they played in the war effort as a whole.

The chart accompanying Green’s article showed that the war opened up jobs for women. Before December 7, 1941, one in four workers were women, and after Pearl Harbor one in three workers were women. In her article, Green explained that employers who had women employees in their plants were more likely to hire women than all-male operated factories, and by 1942 many employers were either looking into hiring women or had already done so to fill positions previously held by men. Several training programs also allowed women to learn skills such as operating machinery, which would enable them to take on factory work (6-7).

Green found that not everyone was happy about women entering the workforce, however, because women employees needed to be treated differently from men. Not all men left to go to war, some stayed in factory positions, and some employers were slow to hire women because they were afraid of how their male employees might react. Plant supervisors also had to add facilities such as a women’s restroom. Due to stereotypes related to women’s physical abilities and their allegedly delicate sensibilities, employers had to introduce additional safety measures such as providing stools for sitting, breaks for rest, and a midday hot meal for sustenance (8, 40). They reported that some women were also absent from work more often, because, in addition to work, they still had their families and household responsibilities. Not all women wanted to join the workforce or work in factories during World War II, even if they had done so during World War I. These women had to be persuaded to either come back to work, or enter the workforce for the first time, and Green found that higher wages, child care programs, and the promise of an independent life usually enticed them (10, 52).

Selection: Constance McLauglin Green, Appendix II: “Questionnaire Relating to Women Employed in War Plants in the Connecticut Valley,” in The Role of Women as Production Workers in War Plants in the Connecticut Valley (1946), 77-78.

In 1945, unlike 1919, women stayed on the job or found other work rather than returning to the home. Dr. Hill’s report, Women in Gainful Occupations, 1870-1920, established that while more women participated in the workforce during World War I than in previous years, the number of women still working after World War I was roughly the same as before the war. Once World War II was over, many women and their employers saw it in the women’s best interest to continue working in the same ways with which they were familiar. For instance, the Springfield Chamber of Commerce Post-War Planning Committee sent a survey to war plants in the Connecticut Valley. In one plant, out of 3,374 responses, 2,759 women agreed to continue working and only 615 declined (63-64). Many women and their families enjoyed the extra income, others appreciated the social aspect of working outside of the home, and still others felt the importance of being a productive member of society. Employers felt that women were easier to supervise, responsible for less job turnover and decreased accident rates, and could be paid less than men outside of wartime.

Questions to Consider:

- Spend two minutes reviewing the chart. If you were to construct a narrative, or tell a story, of what this chart says, what would you describe?

- The questionnaire contains questions sent to the plant employers in the Connecticut Valley. Do any of the questions surprise you?

- Why do you think they only asked the plant employers, and not the employees? What could be the underlying reason for choosing that population, as opposed to another?

The Working Single Girl

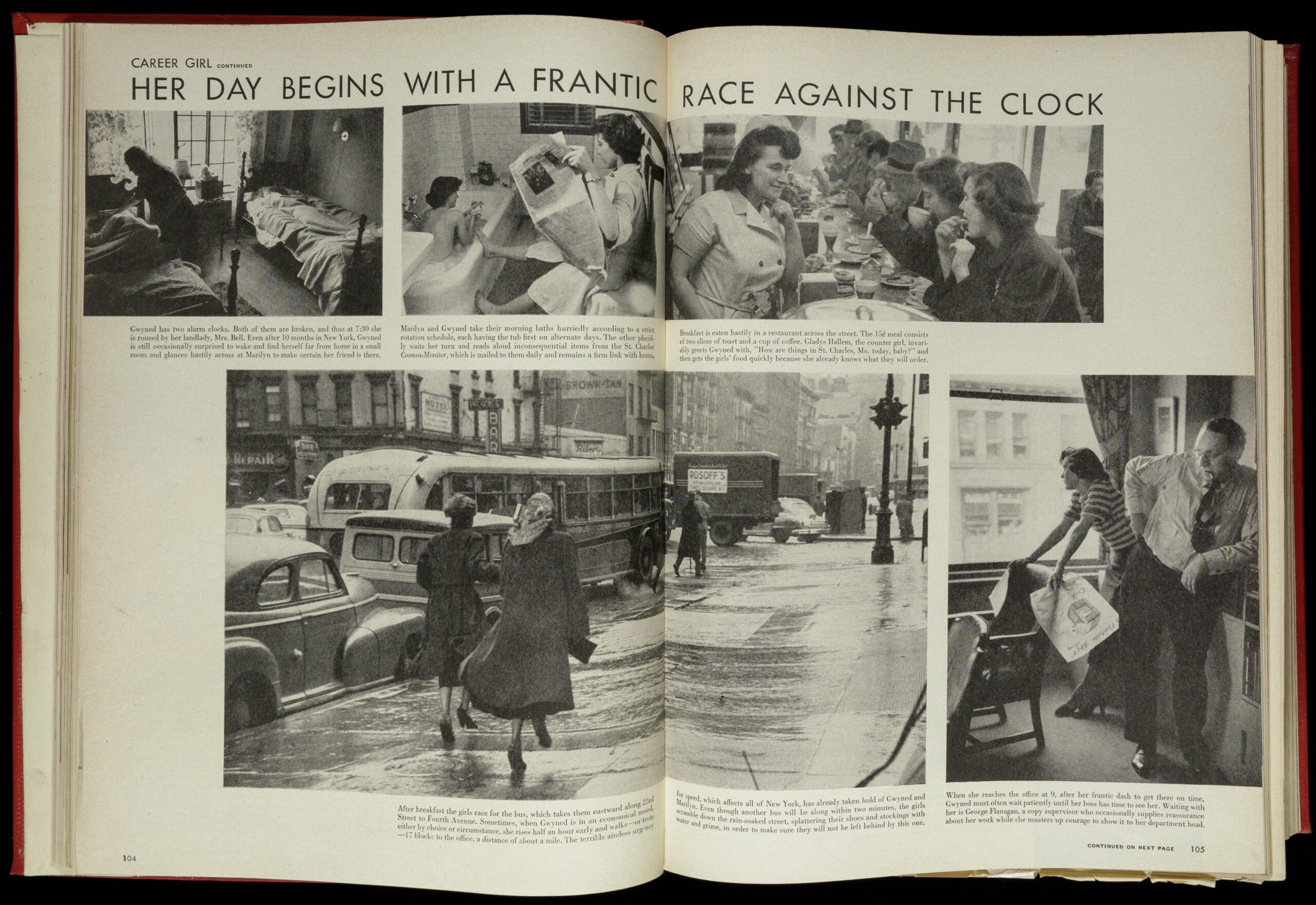

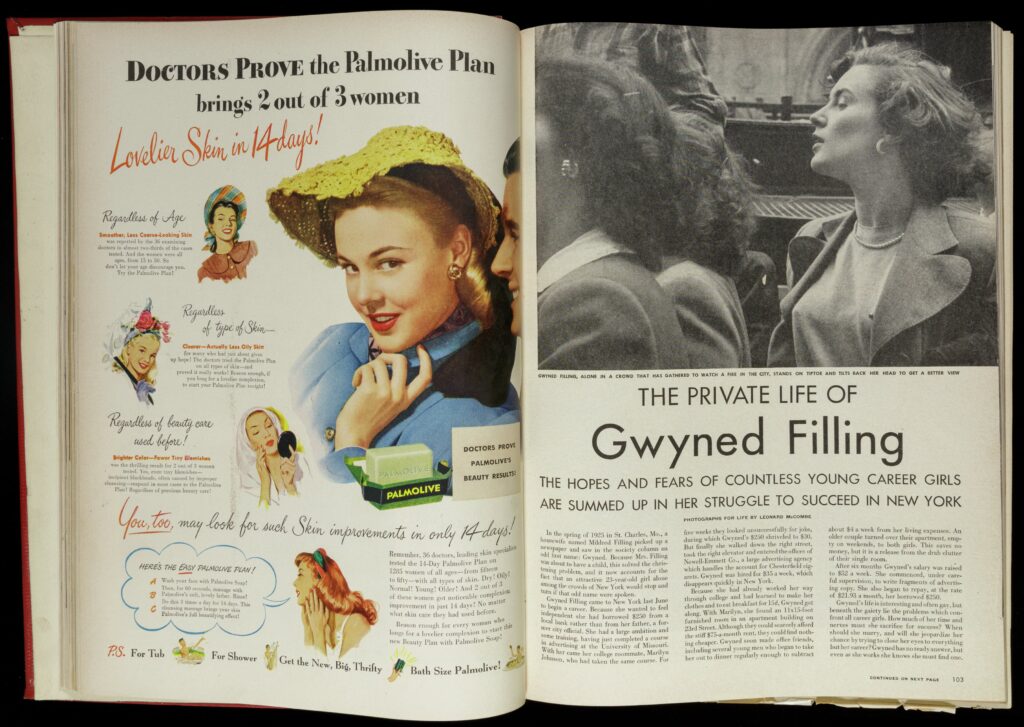

The May 3, 1948 issue of Life Magazine, a popular American weekly periodical, featured Gwyned Filling, a working woman in New York City. The article titled “The Private Life of Gwyned Filling” followed Gwyned and portrayed her as the quintessential career gal, as explained in the subheading: “The Hopes and Fears of Countless Young Career Girls are Summed Up in Her Struggle to Succeed in New York.” Gwyned was born in 1925 in St. Charles, Missouri, and attended college at the University of Missouri. She borrowed $250 from a bank, rather than her father, to demonstrate her independence and moved to New York City in June 1947 to start a career. She had taken an advertising course in college, and after five weeks of searching, found a position at an advertising agency called Newell-Emmett Co. She worked for $35 a week and shared a $75 per month single room apartment with her roommate, Marilyn. After working at Newell-Emmett for six months, Gwyned earned a raise of $52 per week.

All of this information is available on the first page of the twelve-page article. The rest of the article blends text with photographs of Gwyned living her life. While the majority of the article focuses on Gwyned’s work, the rest discusses things like her past and current relationships, her ability to afford everyday items, especially clothes, and (as the article promised) her hopes and fears. This is a very intimate article that studies every aspect of Gwyned as a person, delving deeper into Gwyned’s life as a woman, and as a woman in the workforce. While she did not represent all working women during this time, the story is framed in such a way to represent her story as one of many, many women who work to support themselves, their families, and their independence.

Selection: “The Private Life of Gwyned Filling” in Life Magazine (May 3, 1948), 103-113.

Questions to Consider:

- What do you think this article is trying to accomplish?

- Why do you think Life Magazine picked Gwyned Filling to be the representative of young career girls in 1948? And, further, in what ways is Gwyned possibly not representative of many women in the workforce, despite the magazine’s intentions?

Working Wives and Mothers

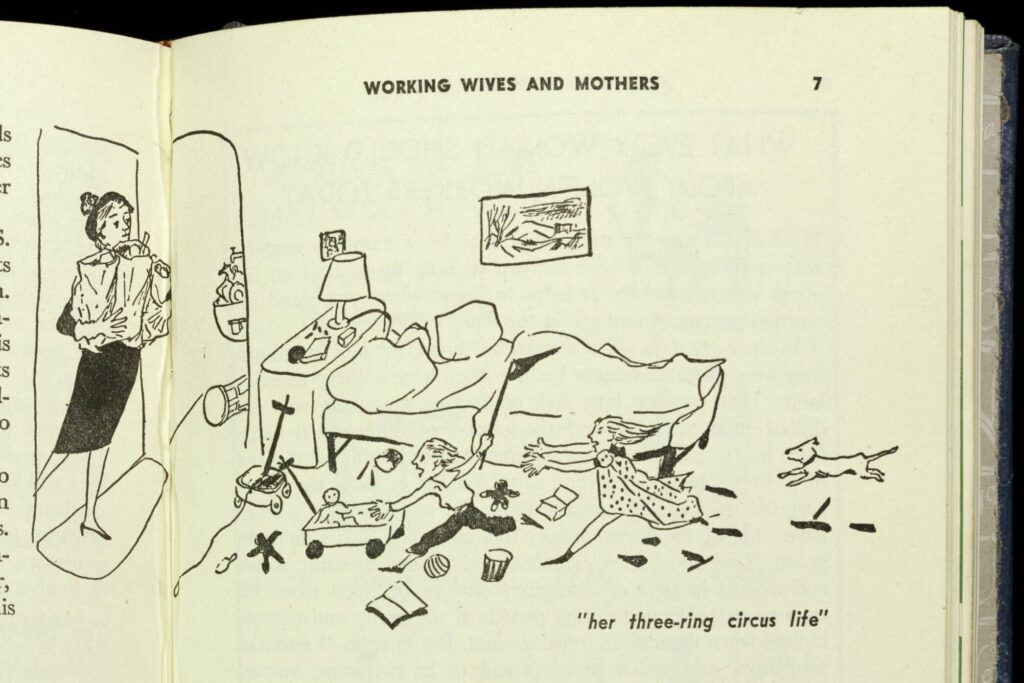

Some members of society, including working women, believed that women should only work while they were single. In reality, though, not all women stopped working once they became wives and mothers. The Public Affairs Committee published two pamphlets, Should Married Women Work? and Working Wives and Mothers, in 1940 and 1952, respectively. Both pamphlets addressed the various reasons that wives and mothers worked, as well as the obstacles they faced, and the steps society, their employers, and their families could take to help them stay in the workforce. Ruth Shallcross compiled Should Married Women Work? from a study conducted by the National Federation of Business and Professional Women’s Clubs, and began by telling the story of one particular woman, who was meant to represent many. Mary Smith was a housewife who found work at a department store after her husband’s job was reduced to part-time because they could not survive on his lowered salary alone. Working Wives and Mothers was written by Stella Applebaum, a working mother herself, and featured several women’s stories to highlight the fact that every woman’s situation was different.

Selection: Ruth Shallcross, Should Married Women Work? (1940), 6-7, 11, 28-29.

Both pamphlets outlined beliefs that some people held against working wives and mothers: that married women didn’t need to work for money because their husbands could provide support; that families would suffer if women were not at home to care for them; that married women took jobs away from people who needed them (men and single women); and that they would be unreliable and not take their work seriously because of outside concerns, including their obligations to their families. Some states went so far as to take legal action, and proposed legislation to limit married women’s opportunities or altogether ban them from the workplace, as the map below illustrates. Working Wives and Mothers concluded that “our country will have the services of womanpower to maintain the high level of productivity we enjoy today” (28), and they could not do that without respect and understanding. The pamphlets not only offered practical advice for working wives and mothers, but also for the rest of society. For example, the pamphlet urged employers to offer part-time work or flexible hours and suggested to husbands and children that they could help out more at home. Applebaum also recommended that the “Industry,” as she calls it, regard the family as a primary rather than secondary concern, as explained in the document below. She believed that the workplace and home were equally as important, and society should show balanced respect and support for both. These two pamphlets succeeded in arguing that despite the many obstacles they faced, women continued to work simply because they were human, with particular economic needs and desires for independence. No matter what, anyone had the right to work, and it was the duty of employers and society to help women succeed in the workforce.

Selection: Stella Applebaum, Working Wives and Mothers Public Affairs Pamphlet no. 49 (1952), 31.

Questions to Consider:

- What does the illustration on p.6-7 of the Working Wives and Mothers pamphlet show? How could this situation improve?

- What are your answers to the questions asked in the “Tempest in a Teapot” section of Should Married Women Work?

Women in the Workforce

The period from 1920 to 1950 saw the numbers of working women steadily rise with each decade, with women increasingly occupying positions in offices, factories, and so forth. These materials document this trend and how working women became a demographic group studied and recognized for their contributions to the U.S. economy.

Support for Working Women

Many women faced sexism, racism, and other challenges both while trying to enter the workforce and once in it. There were a variety of resources and spaces that women could look to for information, advice, and support, as these materials demonstrate.

Views on Working Women

These documents–a feature in Life Magazine of a working woman in New York City, Stella Applebaum’s Working Wives and Mothers, and Ruth Shallcross’s Should Married Women Work?–capture the different backgrounds and situations that led women into the workforce and the varied opinions on working women and family responsibilities.

Further Reading

Kessler-Harris, Alice. Out to Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press,1982.

Woloch, Nancy. Class by Herself: Protective Laws for Women Workers, 1890s-1990s. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

Milkman, Ruth. On Gender, Labor, and Inequality. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2016.

Brock, Julia, Jennifer W. Dickey, Richard Harker, and Catherine Lewis, eds. Beyond Rosie: A Documentary History of Women and World War II. Fayetteville, AK: University of Arkansas Press, 2015.