Introduction

Why was the idea of a hidden or double self so appealing to writers and readers of the late Victorian period? Two of the most powerful and controversial English novels of the time are Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886) and Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890). Both novels explore a conflict between the demands of social respectability and the desire to pursue pleasure. Both offer the fantasy solution of having a second self to carry the burden of one’s vices. Dr. Jekyll confesses that he possessed a “gaiety of disposition” that could not be reconciled with his desire “to carry my head high, and wear a more than commonly grave countenance before the public.” Even before he learned to transform himself into Mr. Hyde, he “stood already committed to a profound duplicity of life.” The identity of Mr. Hyde takes this duplicity to its logical extreme. Mr. Hyde allows Jekyll to shed all restraint and “spring headlong into the sea of liberty.”

Dorian Gray’s path to a double life begins with vanity, the wish that he might hold onto his beautiful, youthful appearance and let his portrait bear the ugly changes associated with age. But it quickly becomes clear that changes in our appearance are not due to a neutral process of aging, they are manifestations of our sorrows and our crimes. When Dorian discovers that his appearance will not change regardless of his actions, he claims full license to act as selfishly and cruelly as he chooses in pursuit of pleasure and “passionate experience.”

The following collection of primary sources develops the cultural contexts for these novels’ representations of double and hidden selves. While Stevenson’s novel draws attention to early theories of the unconscious, Wilde’s novel points to his engagement with Aestheticism, the late-nineteenth-century arts movement that promoted art for the sake of its beauty alone, not for any utilitarian, moral, or political purpose. Both novels also raise questions about gender and sexual identity. Dorian Gray and Jekyll/Hyde explore what it could mean for educated, Victorian men to pursue pleasure free of the inhibiting threat of social ostracism. Recent literary critics, as well as some nineteenth-century readers, have suggested that the ultimate feared and forbidden pleasure these novels tacitly evoke is sexual relations between men. Indeed, during Wilde’s 1895 trials for “indecency,” the prosecutor tried to use The Picture of Dorian Gray as evidence against him. Many of the sources that follow explore changing ideas about gender and sexual identity in England and America at the turn of the last century.

Essential Questions

- What were the cultural contexts for Stevenson’s and Wilde’s novels? How can studying these contexts lead us to a deeper understanding of the novels?

- How did writers and audiences in late Victorian England and America explore the idea of a hidden or double self? What does the hidden self represent?

- What is the role of sexuality in representations of the hidden self in Victorian society? What were the prevailing norms around gender and sexual identity at this time?

- What are the roles of class and urban geography in Stevenson’s and Wilde’s novels?

- In what ways do Wilde’s and Stevenson’s representations of the hidden self challenge prevailing conceptions of sin and crime? In what ways do they reinforce these conceptions?

Geography of the Double Life

Late one night, near the end of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, Dorian dresses himself in “common” clothes, conceals his face behind a scarf and hat, and walks to Bond Street where he hails a carriage. The driver initially refuses to take him to the address he requests, but after Dorian has promised a large payment, they take a long journey through London to a neighborhood by the shipping docks on the Thames River. The streets are roughly paved and dimly lit. Dorian enters “a small shabby house, that was wedged in between two gaunt factories.” The house is an opium den, peopled with gentlemen, sailors, and prostitutes, South Asians and whites: “grotesque things that lay in such fantastic postures on the ragged mattresses. The twisted limbs, the gaping mouths, the staring lusterless eyes…”

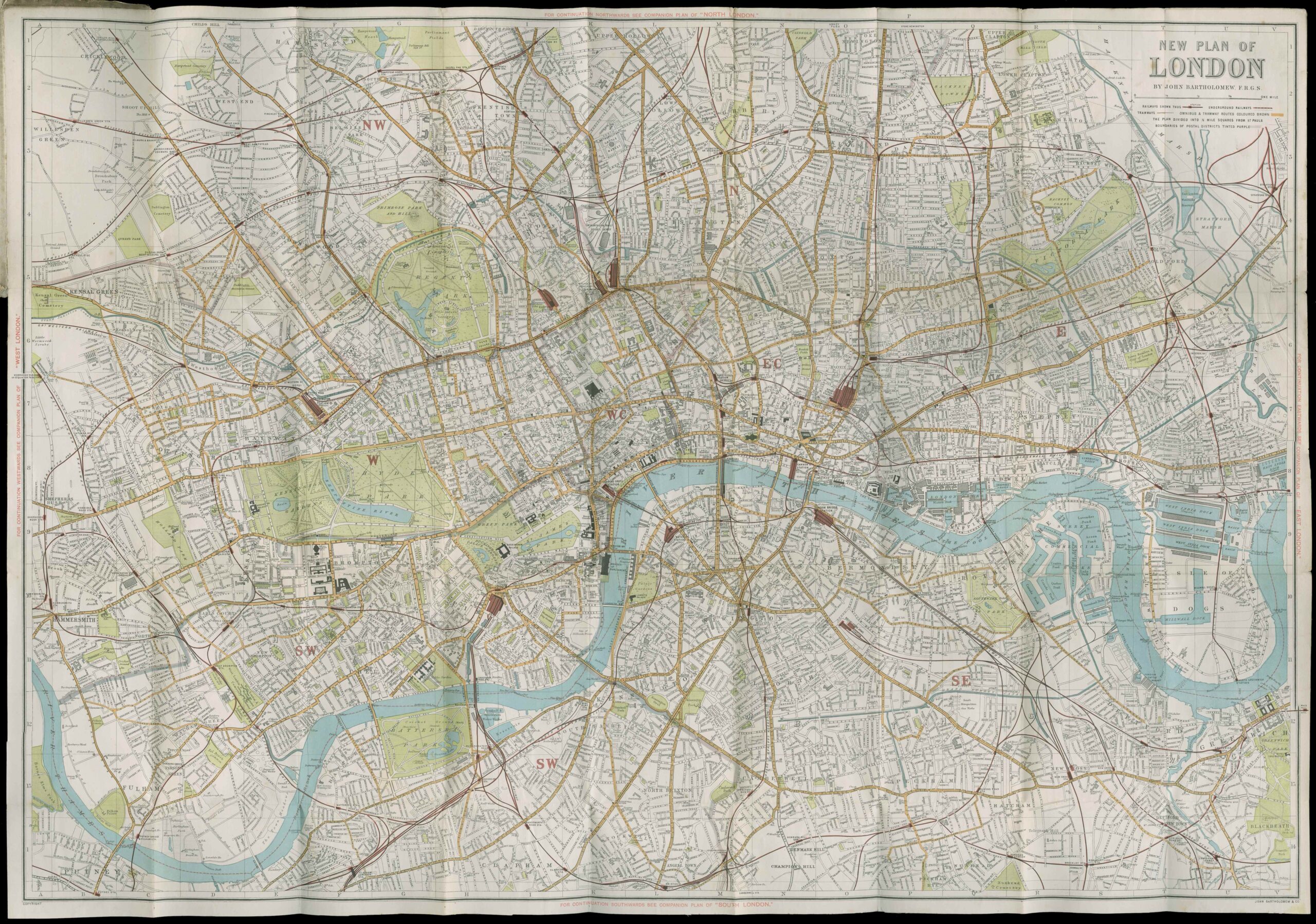

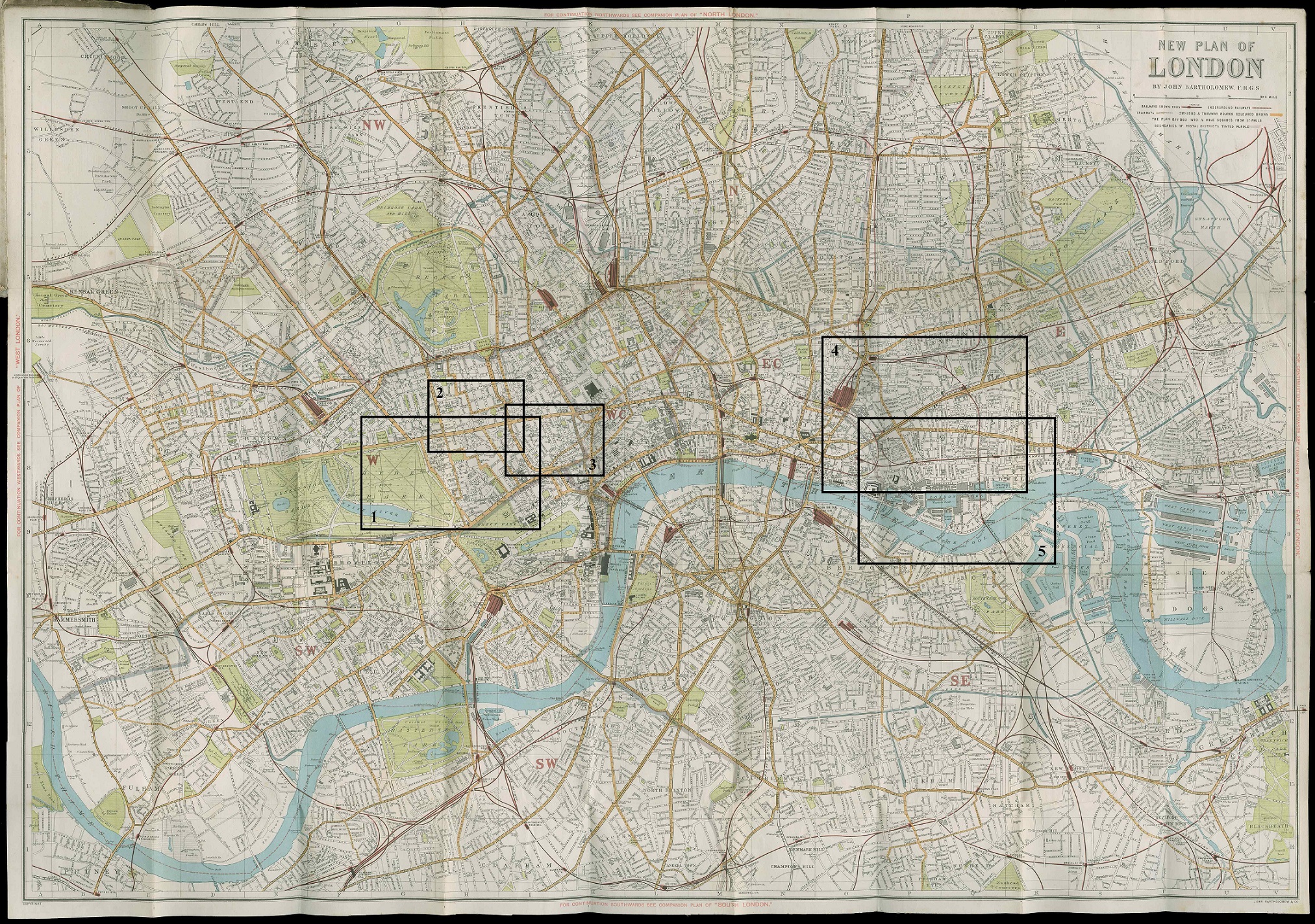

Dorian’s journey on that night makes explicit a pattern of behavior that both Robert Louis Stevenson and Oscar Wilde reference throughout their novels: wealthy Victorian men escaped stifling social conventions and the surveillance of their peers by seeking pleasure in London’s poor neighborhoods. In the 1880s and ’90s, London was a city deeply divided by class. The city’s population had increased exponentially during the course of the nineteenth century, from less than one million in 1800 to over four million in 1890. The population increase was due to immigration from the English countryside as well as from Ireland and Central and Eastern Europe.

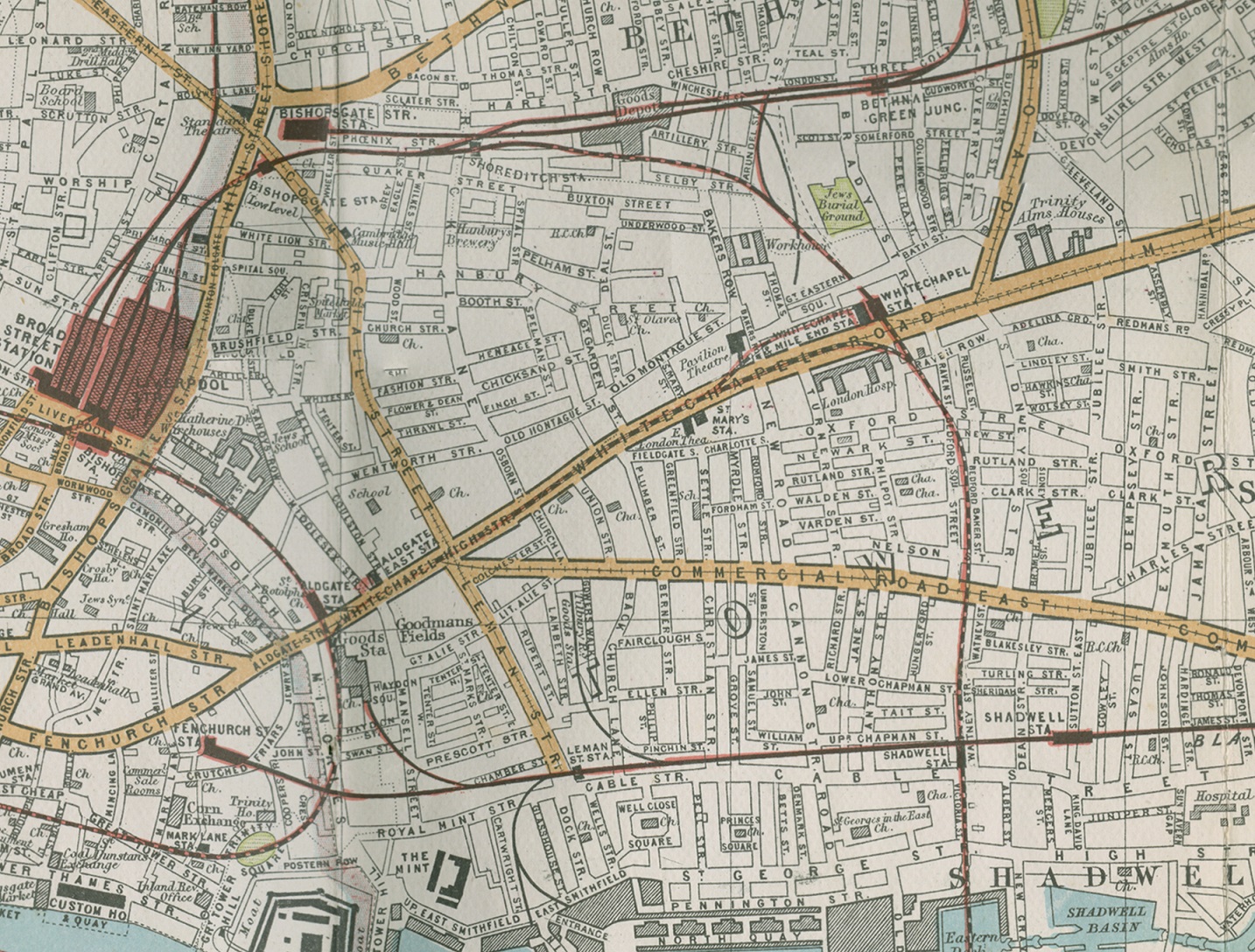

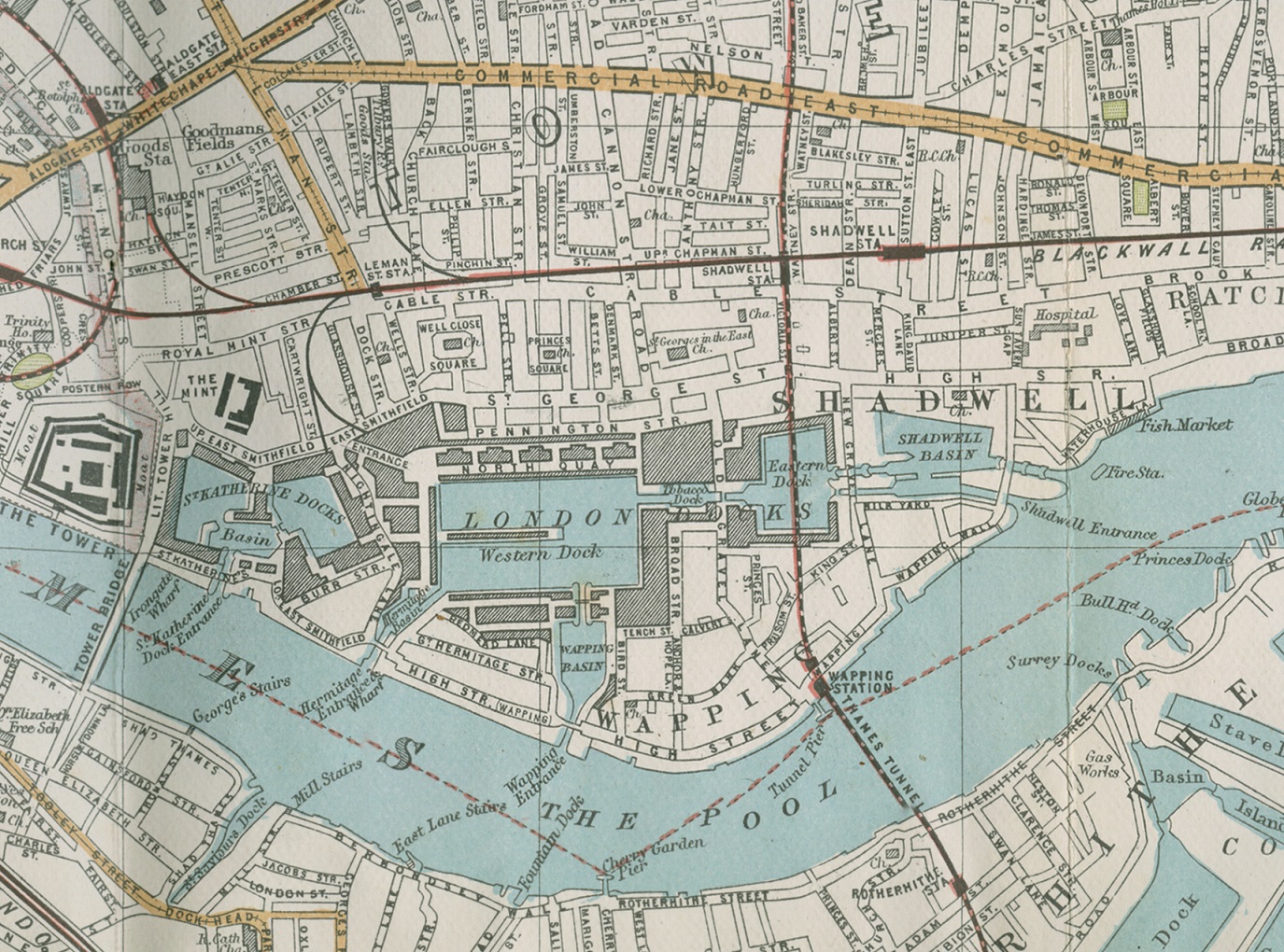

Many poor and working-class people found themselves crowded into miserable slums on the East End, that is, the neighborhoods east of the City of London and north of the Thames River. The area included the docks that received goods from Britain’s growing empire in South and East Asia and the West Indies. It also included sea-related industries, such as shipbuilding and rope making. The hub of the East End was Whitechapel, a neighborhood that became notorious in the late 1880s as the site of the Jack the Ripper murders.

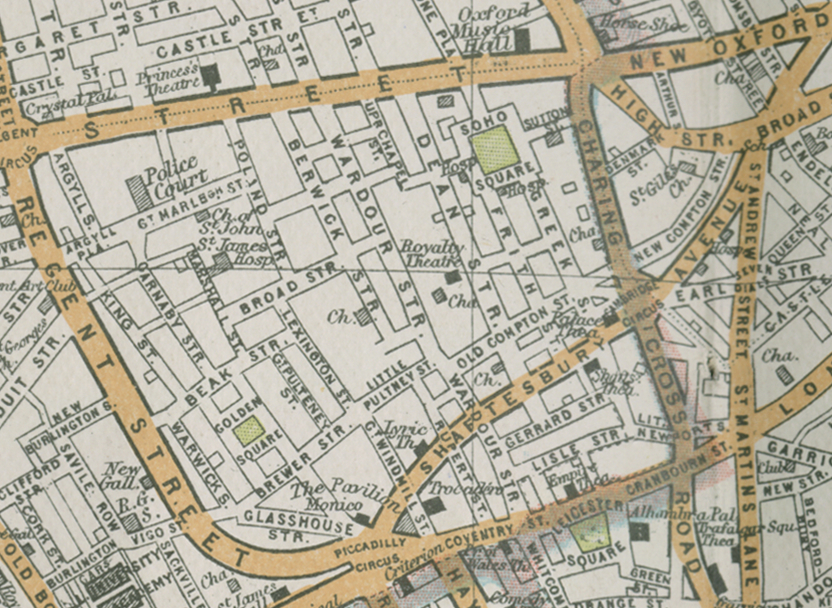

In contrast, the main characters in The Picture of Dorian Gray spend much of their known lives in Mayfair, a wealthy, fashionable neighborhood in central London. Lord Henry Wooton’s house, the Royal Academy of Arts, and the Grosvenor House Hotel are all in Mayfair. In Stevenson’s novel, Dr. Lanyon, the close friend of Utterson and (at one time) Jekyll, lives at Cavendish Square, one block north of Mayfair. Henry Jekyll chooses Soho, the neighborhood just east of Mayfair, but still in central London, as the location for Edward Hyde’s house. This formerly respectable, if not wealthy, neighborhood had, by the mid-nineteenth century, become known for its music halls, small theaters, and prostitutes.

Wilde’s and Jekyll’s wealthy characters were not unusual for venturing to poor and working-class neighborhoods. As historian Seth Koven notes, by the 1890s, large numbers of wealthy Londoners regularly visited the East End, sometimes under the auspices of philanthropy and social reform, but often as tourists and pleasure-seekers or some combination of all of these. For the educated elite, Koven argues, the East End could be the site of personal liberation, an escape from upper-class, Victorian mores into a world they saw as exotic, primitive, and free of moral restraint.

The map below shows the layout of London in the 1890s and, specifically, the neighborhoods represented in Wilde’s and Stevenson’s novels.

Bartholomew, New Plan of London

Questions to Consider

- Describe the layout of London in the 1890s. What do you notice about the city’s location?

- How are London’s streets arranged? How would you compare the city’s plan to that of American cities, such as New York and Chicago?

- Compare the neighborhoods of central London to those of the East End. Where are the green spaces, such as parks and squares? How large or small are the streets? What evidence do you see of industry or commerce? Which routes would one take from central London to the docks or to other parts of the East End?

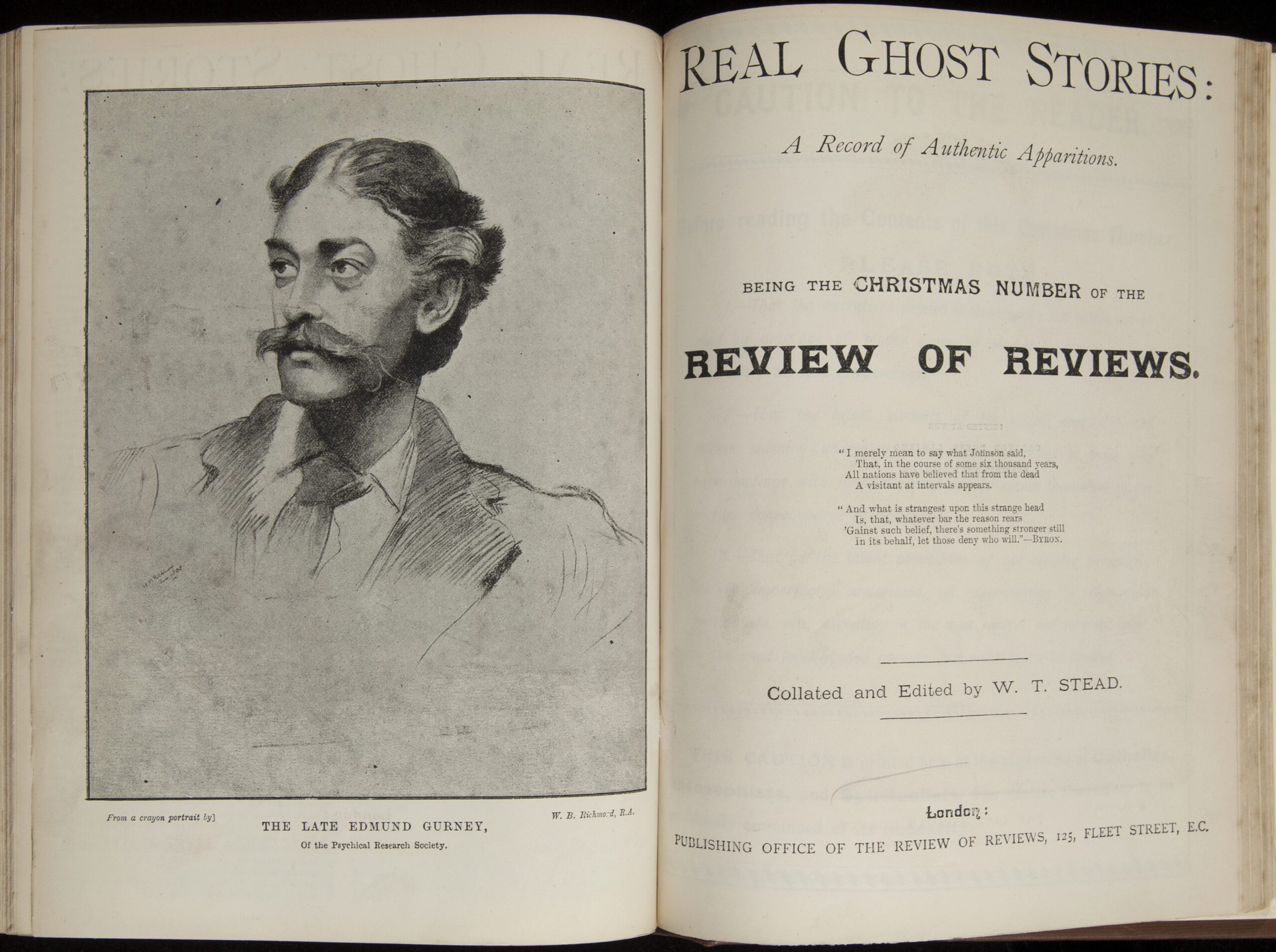

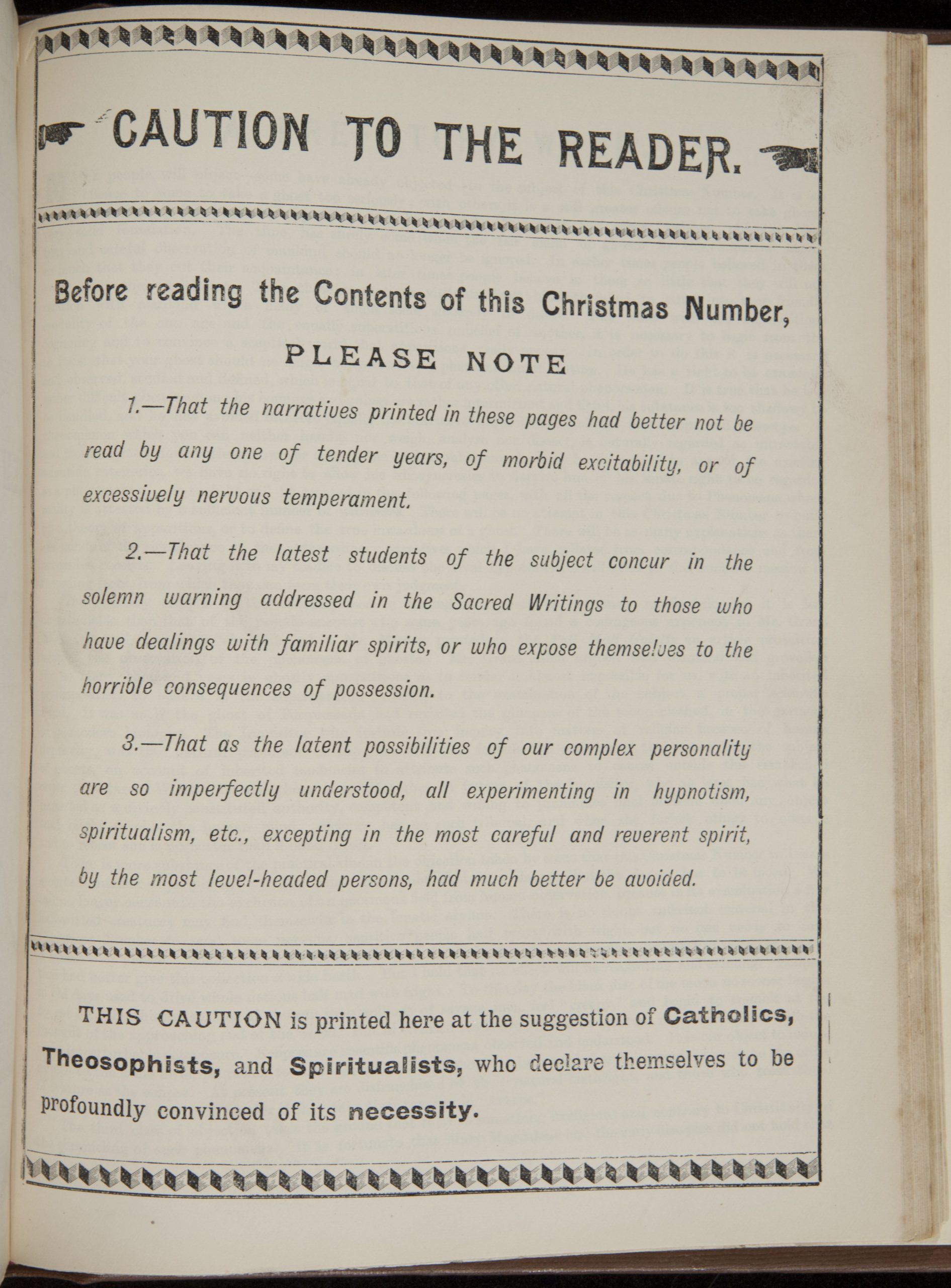

Victorian Representations of the Hidden Self

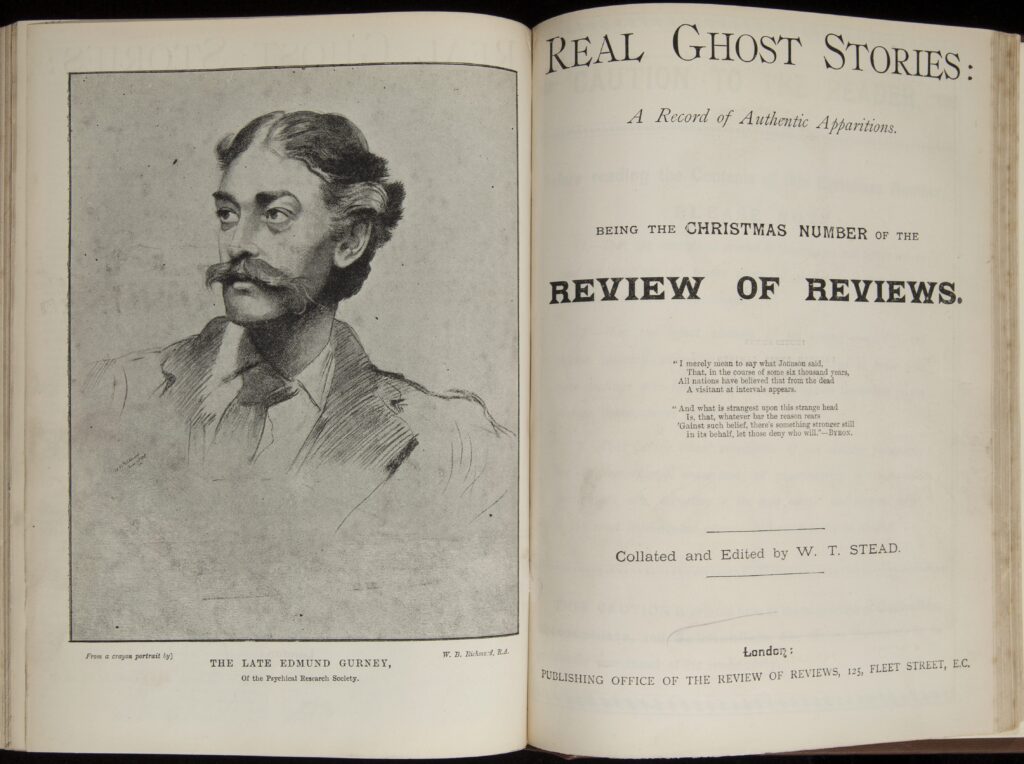

British journalist and reformer W. T. Stead devoted the 1891 Christmas issue of his journal Review of Reviews to scientific studies of “real ghost stories.” Yet, the first essay that Stead published was not a ghost story in the conventional sense of gothic and supernatural. Instead, it was a study of “the ghost that dwells in each of us.” The article suggests that there was widespread interest in the idea of the unconscious—a part of the mind that exists below the level of conscious thought—years before Sigmund Freud’s landmark work The Interpretation of Dreams (1899).

Stead, Real Ghost Stories, The Ghost in Each of Us

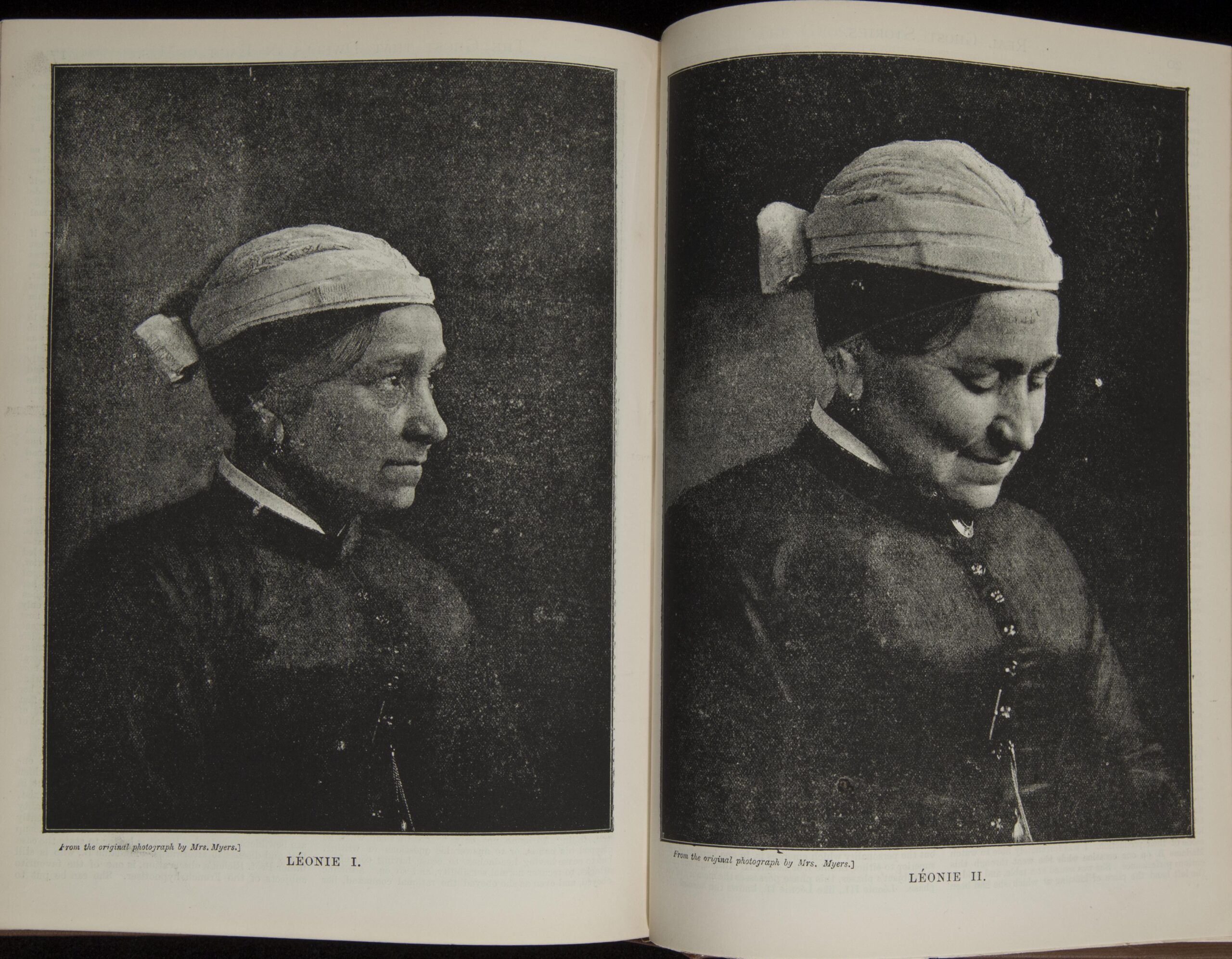

The magazine also included an account of a woman referred to as Madame B. who, under hypnosis, revealed alternate personalities.

Stead, Real Ghost Stories, Mme. B as Leonie I and II

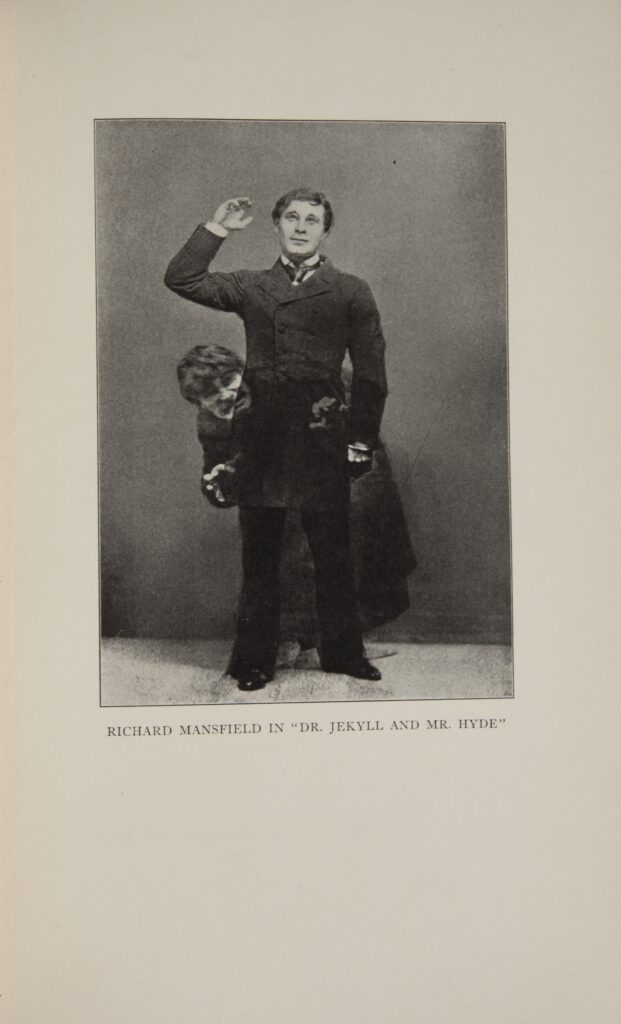

The second source below is an excerpt from the biography of Richard Mansfield, a British actor celebrated for his dual performance as Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in an 1887 stage adaptation of Stevenson’s novel. The photograph of Mansfield was created using the technique of double-exposure. The photographer took Mansfield’s picture, then rewound the film and took a second shot over the first, making the two images appear to be one. Both the text and the image below suggest how Mansfield attempted to express Jekyll/Hyde’s double nature.

Questions to Consider

- Why do you think Stead included this “Caution to the Reader” at the beginning of his Real Ghost Stories issue? How might the warning contribute to interest in the magazine? What could be dangerous or threatening about the magazine’s subject?

- What does the essay’s author mean by “the ghost that dwells in each of us”? How does the writer both build on and depart from Christian understandings of the “dual nature” of man, that is, torn between good and evil? Is there a moral distinction between the conscious and the unconscious?

- How does the Review of Reviews writer compare the conscious and the unconscious to husband and wife? What are the implications of this metaphor, both for thinking about the mind and for thinking about gender?

- According to Mansfield’s biographer, how did the actor understand the character of Jekyll and Hyde? How did he convey the differences between them and the transformation from one to the other?

- Based on the photograph, describe Mansfield’s physical appearance in each of the roles of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Why were audiences terrified by Mansfield’s performance? Why were people reluctant to believe that the actor could make this transformation without the assistance of artificial devices?

Wilstach, Richard Mansfield: The Man and the Actor

Victorian Masculinity and Effeminacy

In Britain and the United States today, boys and men who display feminine behaviors are often subject to ridicule and accused of being gay. Yet cultural theorists such as Michel Foucault and Eve Sedgwick caution against assuming that the Victorians thought about gender and sexuality in the same ways that people would in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Critic Alan Sinfield argues that, as late as the 1870s, “recognition of homosexuality as a practice and a subculture was still very uneven and muddled.” For much of his life, Oscar Wilde and other aristocratic men could embrace the public persona of the “effeminate aesthete and dandy” without necessarily being accused of having sexual desire for other men. This apparent freedom did not reflect tolerance of homosexuality. Rather, to the majority of people in Victorian England, sexual relations between men were so horrifying as to seem unthinkable, at least among respected acquaintances. However, as later texts in this collection will show, these cultural norms were changing rapidly. In 1885 the British parliament passed a law making it much easier to prosecute men for homosexuality and in 1895 Wilde found himself convicted of crimes and publically vilified for his relationships with men.

The documents that follow testify to the acceptability of some expressions of male effeminacy in England throughout much of the nineteenth century. The illustrations come from the London magazine The Woman’s World, which Wilde edited from 1887 to 1889. They portray Charles Edward Stuart, known as the Young Pretender, the grandson of the Catholic king James II (who ruled Britain from 1685 to 1688). Stuart proclaimed himself the rightful heir to the throne and in 1745 attempted to invade England from Scotland. His forces were quickly defeated and he escaped into exile in France, reportedly in the disguise of a maid named Betty Burke. Although Charles earned a reputation for drunkenness and debauchery in his remaining years in Europe, he was romanticized as a national hero of Scotland. Wilde published these illustrations, based on 1748 paintings, along with other drawings from history and fashion.

The second document is an excerpt from a series of interviews conducted with a Conservative British politician and aristocrat shortly before his death. They were published in Blackwood’s magazine. Lord Lamington reminisces about the “polished and brilliant society” of the 1830s and 1840s, which he and his interviewer lament no longer exists. In this passage, “A” stands for author, that is, Lord Lamington, who has written his memoirs, and “Maga” for the magazine’s publisher who interviews him. Lamington spends some time discussing the Count d’Orsay, a French artist and man of fashion who married into the English aristocracy, but went bankrupt in the last years of his life. (D’Orsay was the model for the New Yorker magazine’s Eustace Tilley.)

Blackwood, In the Days of the Dandies, pg 4-7

Questions to Consider

- Describe the two portraits of Charles Edward Stuart. What differences and similarities do you notice between them? In what ways would you characterize his appearance as masculine or feminine in each portrait? Does he appear beautiful?

- What does Lord Lamington mean by the term dandy? What qualities do—or did—dandies possess? What is the role of class in the making of a dandy?

- Consider the description of Count d’Orsay specifically. What are the qualities that made d’Orsay an impressive or memorable person in Lamington’s eyes?

- Does sexual identity seem to be a factor in Lamington’s descriptions of d’Orsay or in any other passages from this text? Why or why not? Do you think that such attention to men’s fashion and appearance would be associated with sexual identity today? Why or why not?

The Trials of Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde’s vaguely scandalous reputation took a devastating turn in 1895 when Wilde participated in three court cases. The first, he initiated as a libel suit against the Marquess of Queensbury, the father of Wilde’s lover, Lord Alfred Douglas. Queensbury had accused Wilde of “posing somdomite” (that is, pretending to be a sodomite, a man who has sex with other men) and Wilde sued to clear his name, assuming that Queensbury could have no proof. Queensbury hired private detectives who produced a great deal of evidence, not only incriminating letters that Wilde had written to Douglas, but testimony of Wilde’s liaisons with young, working-class, male prostitutes as well. Wilde lost the case and found himself immediately prosecuted by the state on the basis of the evidence that Queensbury had produced in the libel trial. The charges were “gross indecency”—sexual acts—“with another male person.” The jury did not reach a verdict in this trial, but the prosecution brought the case again and, this time, Wilde was found guilty. He received the maximum sentence: two years in prison with hard labor. Upon his release, he left England for France and spent the last three years of his life in poverty and exile. He died of cerebral meningitis in 1900.

It is worth noting that the law that Wilde was convicted of breaking was itself less than a decade old. The Labouchere Amendment, as it was known, was hastily added to an 1885 law intended to protect young women from prostitution. English law already prohibited sodomy, though it was rarely prosecuted. The amendment provided a way to punish same-sex relations, even when sodomy could not be proved.

During the trial, Wilde eloquently defended “the love that dares not speak its name” (a phrase taken from a poem by Lord Alfred Douglas). It is “a great affection of an elder for a younger man,” he said, “as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michelangelo and Shakespeare. It is that deep, spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect. It dictates and pervades great works of art.” Wilde’s words would make him a hero to defenders of gay rights in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

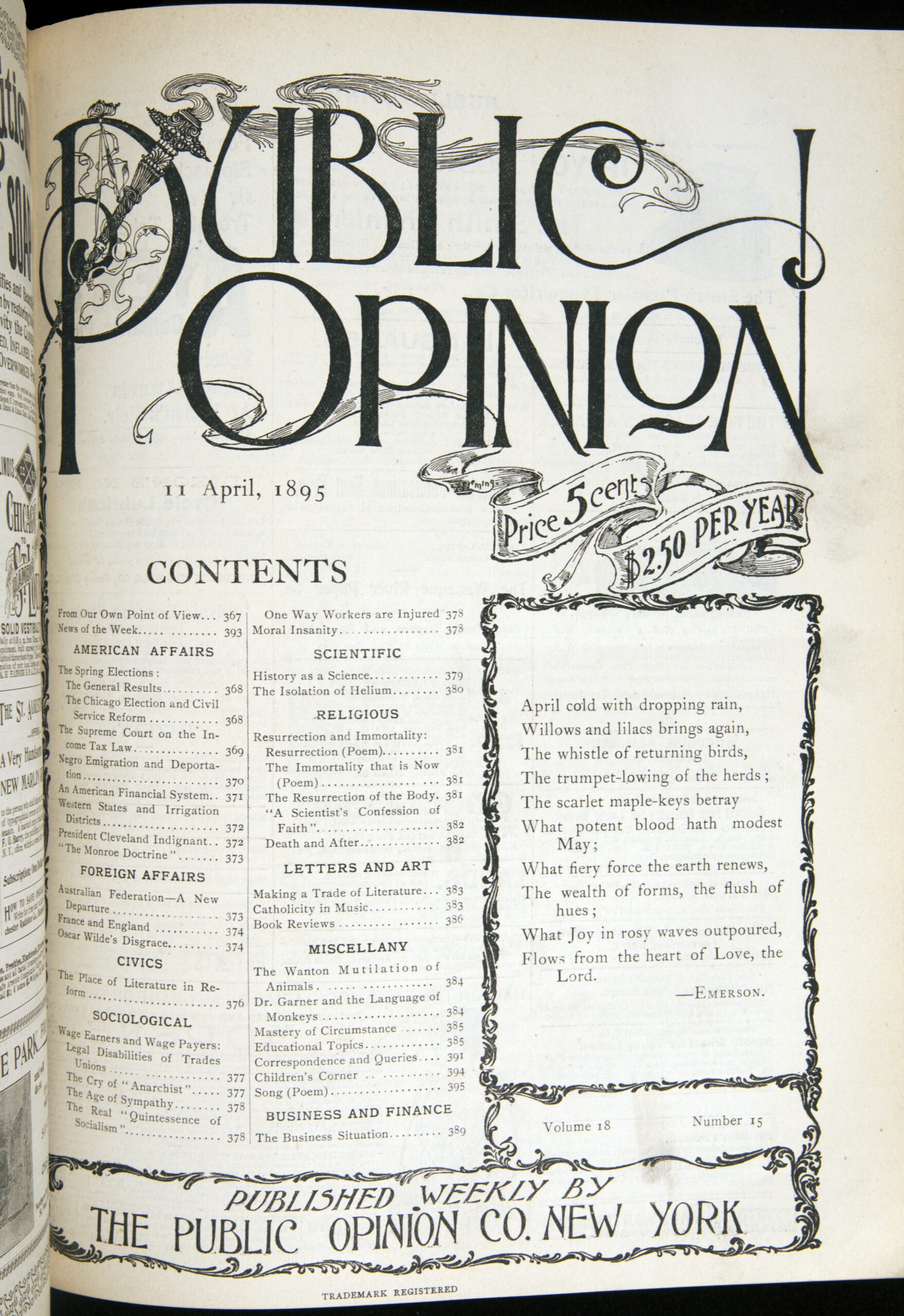

Public Opinion, Oscar Wilde’s Disgrace, pg 374-375

But the trials had the effect of hardening public attitudes against homosexuality in the years that followed. Scholars such as Alan Sinfield and Douglas O. Linder argue, “Many same-sex relations that appeared innocent before the Wilde trials became suspect after the trials.” Previously accepted qualities among educated men, such as a love of art or attention to fashion or an effeminate style, were now increasingly perceived as evidence of gay identity.

The document below represents commentary on the trials that appeared in various U.S. newspapers and was compiled by the New York weekly Public Opinion. Wilde was well known in the United States. In 1882 he had gone on a very successful lecture tour throughout the country in which he presented his ideas on aestheticism. The Picture of Dorian Gray was first published in the Philadelphia magazine Lippincott’s in 1890 before it appeared in London in book form.

Questions to Consider

- How did U.S. newspapers write about Wilde’s trials and alleged crimes? If you did not have any additional information, would you be able to tell what exactly Wilde was accused of? How would you or wouldn’t you?

- What does the newspapers’ language tell you about prevailing ideas about homosexuality in the United States at the turn of the century? What connections do the papers draw between homosexuality and the Aesthetic movement?

- How does “Wilde’s disgrace” provide the basis for these American newspapers to criticize other aspects of English culture, such as the aristocracy and the press?

Criminals and Their Punishment

The two texts below offer competing understandings of what it means to be a person convicted of a crime. The first piece was published in the London weekly magazine The Speaker, which featured articles on politics, science, and the arts. It presents increasingly popular, pseudoscientific theories associating certain physical and intellectual characteristics with a propensity to commit crimes.

The Speaker, The Criminal Appearance, pg 13-14

The second text is an excerpt from Oscar Wilde’s long poem, The Ballad of Reading Gaol, published after his release from prison. The narrative is based on the life of Charles Thomas Wooldridge who was executed at the prison (or gaol, pronounced as “jail”) in Reading, England, on July 7, 1896, for cutting the throat of his estranged wife whom he suspected of adultery. Wilde was imprisoned at Reading at the same time and observed Wooldridge, though they never met. He published the ballad anonymously, using his prisoner identification number, C.3.3, instead of his name. It was a great commercial success, going through seven editions in two years, while few knew the author’s identity. It was the last book Wilde published during his lifetime.

Wilde, The Ballad of Reading Gaol, pg 1-3; 26-27

Questions to Consider

- What is the author’s argument in the magazine article “The Criminal Appearance”? What are the “two orders” of crime that the author identifies? How do these two categories of crime correspond to two “classes,” or types, of appearance?

- According to this author, are criminals almost always recognizable as such, even when they are not committing a crime? How are they recognizable and by whom?

- In what ways do Stevenson and Wilde explore the idea that a person’s crimes become manifest in the person’s appearance? Does Edward Hyde fit the description of either of the physical types identified in “The Criminal Appearance”?

- How does Dorian Gray’s perpetually youthful and innocent appearance affect other characters’ responses to him? What are the physical changes that he and, later, Basil perceive in his portrait?

- Why do you think that Victorian writers, such as the author of “The Criminal Appearance,” were so committed to the idea that a person’s moral character and propensity to crime could be read in his or her physical appearance? Why is the idea of completely dissociating morality and appearance so appealing to Henry Jekyll and Dorian Gray? Do you think that a person’s physical appearance usually reflects his or her moral character?

- How does Wilde portray the prisoners in The Ballad of Reading Gaol? Are they different from other people or monstrous in the way the magazine article suggests all criminals are?

- What are Wilde’s criticisms of the prison system?

- Why do you think Wilde wrote this poem as a ballad, that is, the popular, folk, poetic form?

Further Reading

Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality: An Introduction. Volume 1. Vintage: New York, 1990.

Koven, Seth. Slumming: Sexual and Social Politics in Victorian London. Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, 2004.

Lindner, Douglas O. The Trials of Oscar Wilde. 1895.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Epistemology of the Closet. University of California Press: Berkeley, 1990.

Sinfield, Alan. “Queer Thinking.” In The Wilde Century: Effeminacy, Oscar Wilde and the Queer Movement. Columbia University Press: New York, 1994. 1–24.

Showalter, Elaine. “Dr. Jekyll’s Closet.” In Sexual Anarchy: Gender and Culture at the Fin de Siecle. Viking: New York, 1990. 105–126.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and Other Tales. Oxford University Press: New York, 2008.

Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray. Oxford University Press: New York, 2008.