Introduction

For centuries, China’s encounters with the foreign lands and peoples involved the commercial exchange of goods. The Chinese attitude towards trade viewed it as desirable, within a structured and regulated framework. Prior to the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, China’s trade developed within a global capitalist system dominated by Great Britain and other Western powers. China’s economic growth and trade opportunities were limited by treaty restrictions that hindered its ability to compete. In the decades following the creation of the PRC, the focus of Chinese trade and diplomatic relations were other socialist nations. Hostility between the PRC and the Soviet Union in the 1960s contributed to a rapprochement with the United States in 1972. This set the stage for China’s reopening to the world in the 1980s, the resumption global trade relations, and China’s rapid development into a global economic power.

This collection brings together maps, correspondence, editorial cartoons, and other materials to explore the interplay between foreign trade and diplomacy in China, as well as how China’s economic and diplomatic ties to the outside world have shaped its modern history.

Essential Questions

- How did China seek to control its place within international systems of trade?

- How have China’s domestic politics influenced its foreign affairs?

- How have Western traders and diplomats interacted with China? How have Western perceptions of China and its people changed over time?

Silver, Opium, and Treaty Ports

Throughout the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912), demand for Chinese goods in the West far exceeded demand for Western goods in China. Instead of exchanging goods, European traders seeking Chinese tea, silks, and porcelain had to pay for their purchases with silver bullion. As British and American consumer demand for tea increased in the eighteenth century, so too did the flow of Western silver into China. In the 1760s, China took in more than 3 million taels (a monetary unit equivalent to about 1.3 ounces) of silver; by the 1780s, that amount rose to 16 million.

During the late eighteenth century, the British East India Company slowed the flow of silver by capitalizing on Chinese consumer demand for opium. Opium is a narcotic made from the seed pods of opium poppies, a plant that flourished in British-controlled northern India. European and American merchants called country traders purchased licenses to sell opium from the British East India Company. The country traders sold opium to Chinese merchants in exchange for silver bullion, which could then be used to buy tea and other Chinese goods for Western markets.

Trade and consumption of opium had a profound impact on Chinese society. Qing leaders worried that widespread opium addiction bred moral corruption and instability, and also opened the door to unwanted foreign influence. By the 1830s, China was importing so much opium that the price of silver began to increase. Since the Qing state required its subjects to pay taxes in silver bullion, the amount of taxes peasants had to pay each year rose along with the cost of silver, causing social unrest.

In 1838, Emperor Daoguang decided that the only way to resolve these problems was by ending the opium trade altogether. Daoguang appointed Lin Zexu to oversee the process, but his efforts met resistance from the British who considered the opium trade so vital to their enterprise that in 1839 they went to war to preserve it. In the first document below, a British translation of one of Lin Zexu’s wartime declarations, Lin explains how Britain’s refusal to comply with Qing regulations compelled him to shut down all trade between Britain and China. The Opium War ended in 1842, after British forces captured Shanghai and forced the Qing to sue for peace by threatening to assault the ancient capital city of Nanjing.

British victory in the Opium War reconfigured relations between China and the West. The Treaty of Nanjing, which formally ended the war, increased foreign access to Chinese markets by opening five port cities (Canton, Fuzhou, Xiamen, Ningbo, and Shanghai) to British traders and consulates. These cities, called treaty ports, quickly became cornerstones of China’s new system for overseeing foreign trade and diplomacy. That system struck a tenuous balance between the Qing’s customary policy of containing foreign influence, and new need to satisfy Western demands for greater access to Qing merchants and imperial officials. The second, third, and fourth documents in this section depict how the attempt to balance conflicting Qing and foreign objectives took physical form in late nineteenth century Shanghai, then the largest and most profitable treaty port. In Shanghai and other treaty ports, local officials consigned foreigners to tracts of land called concessions where they erected new buildings, carved out new roadways, and renamed existing streets and neighborhoods. Transforming the urban landscape facilitated Western trading interests by making the treaty ports easier for foreign traders to access and navigate.

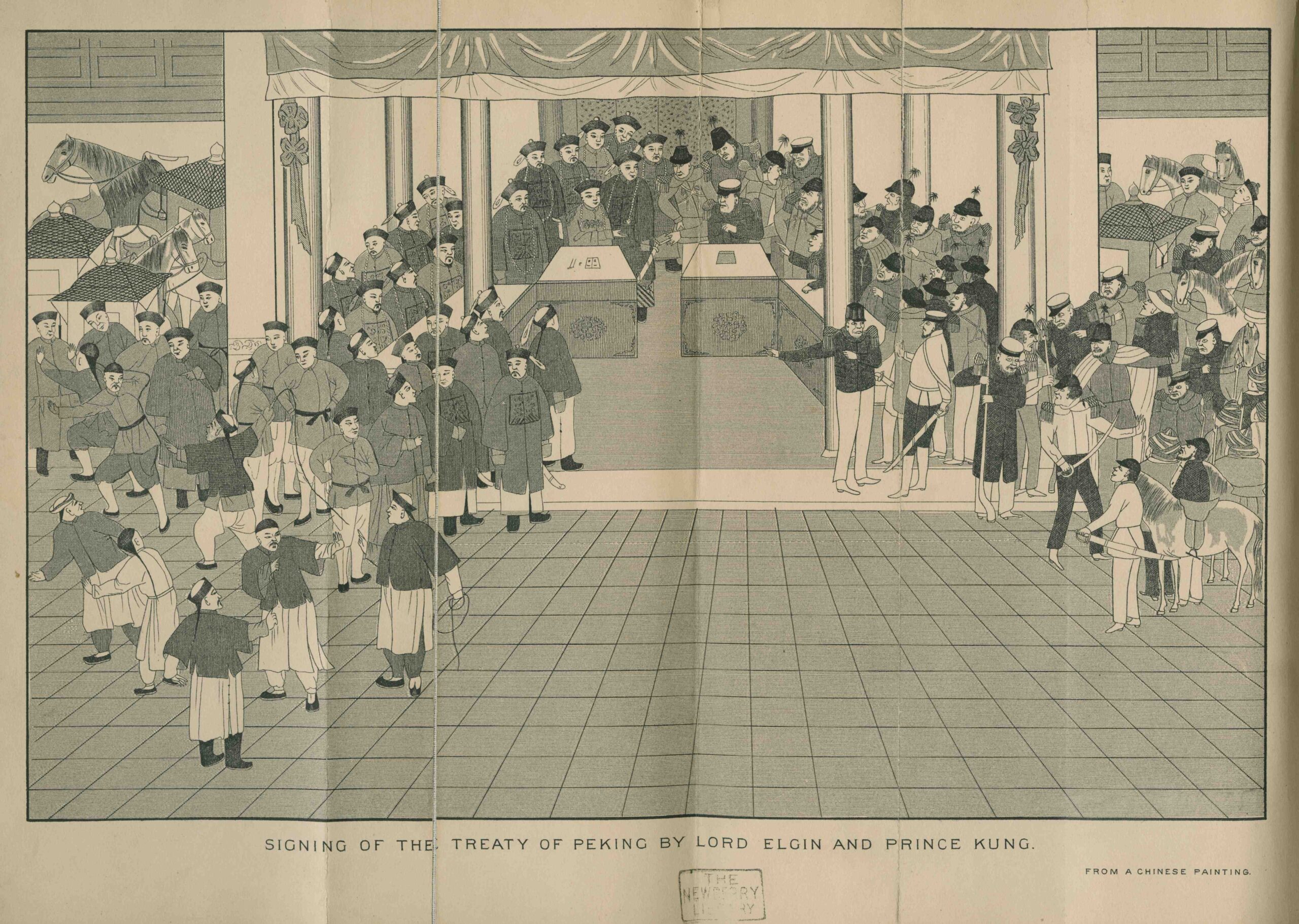

Although the treaty ports gave Britain unprecedented access to Chinese markets, British officials soon turned to military force to extract additional concessions for the Qing state. In October, 1860, soldiers under the command of British High Commissioner Lord Elgin marched on the capitol city of Peking (Beijing), burning the emperor’s summer palace to the ground on the way. To save the city from a British takeover, the emperor signed a new treaty that opened additional treaty ports and further expanded foreign access and legal rights within China. The final document below shows Lord Elgin and Prince Gong, Emperor Xianfeng’s brother, signing the Treaty of Peking, which became the new foundation of the Qing Dynasty’s treaty port system.

Questions to Consider

- How does Lin describe the British in his proclamation? What British actions does Lin object to? Based on this proclamation, what kind of relationship do you think Qing leaders wanted to forge with Britain?

- What are the British concession’s distinguishing features? To what extent did the city change as a result of the British presence? What evidence of ongoing Chinese influence do you notice?

- Look carefully at the map of Shanghai. How is the city organized? What features of the city has the cartographer identified? How are the foreign concessions connected or separated from each other and the walled city? What can the layout of Shanghai tell us about the relationship between China and the West?

- Describe what you see in the illustration of the signing of the treaty of Peking. Who is present at the signing? How are people in the crowd behaving? How would you describe their reaction to the treaty?

Rebellion and the Birth of the Republic

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, Western incursions and civil unrest within China elicited new expressions of Chinese nationalism and hostility toward foreigners. In 1900 these sentiments spurred a grassroots rebellion known as the Boxer Uprising. The Boxers first emerged in 1898 to oppose foreign missionaries working in the province of Shandong. Over the next two years, the group attracted support from young peasant farmers, artisans, and others united by their disaffection with the Qing state and opposition to foreigners. During the rebellion, Boxers seized control of several major cities, and executed the missionaries and other foreigners they encountered.

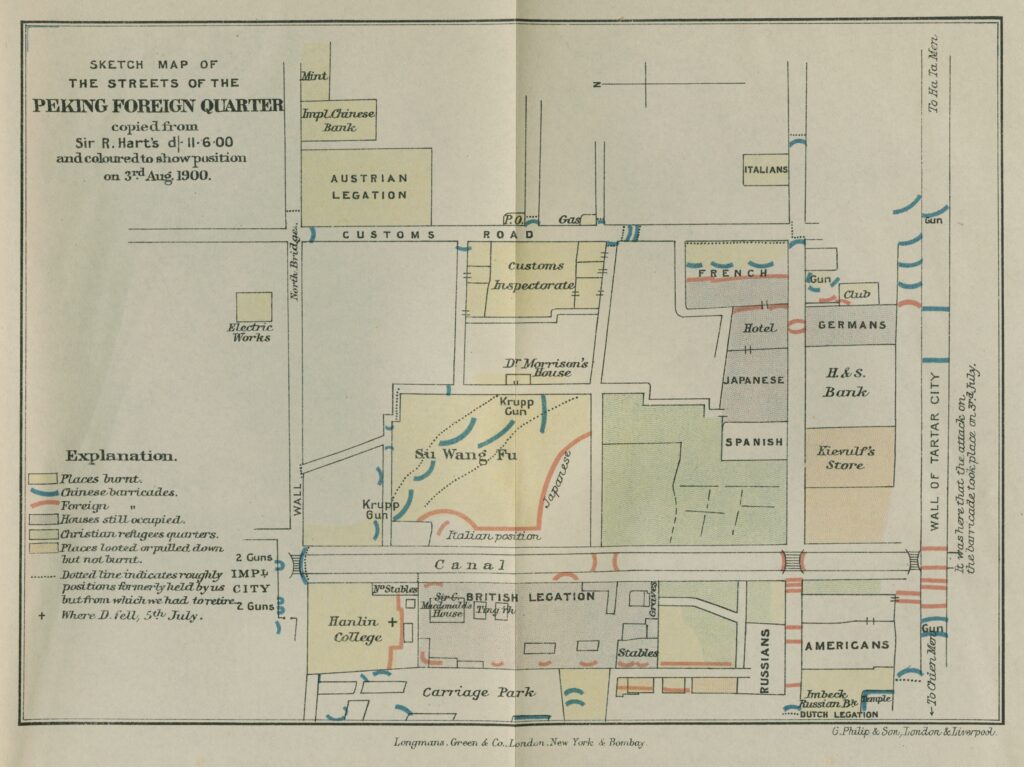

On June 19, 1900, Boxers lay siege to Peking’s foreign quarter, home to diplomats from Europe, the United States, and Japan. The first document below depicts the foreign quarter during the midst of the siege. Orange lines on the map indicate the location of piles of furniture, mattresses, and other items that the foreigners cobbled together as barricades against the Boxers, whose positions are indicated in blue. The siege ended on August 14, when a joint force of British, French, American, Russian, and Japanese soldiers sent from the city of Tianjin arrived in Peking to subdue the rebels and take possession city. The Boxer Protocol, the treaty that formally ended the uprising, the Qing agreed to execute high-ranking officials involved with the rebellion and pay the allied Western powers more than 450,000,000 taels in reparations.

In the wake of the Boxer Uprising, the Qing attempted to implement new constitutional reforms designed to strengthen China against foreign pressure. Dissent and division within China, however, increased throughout the first decade of the twentieth century, sparking a number of anti-Qing movements. Toward the end of the decade, these movements banded together as the Revolutionary Alliance, led by Sun Yat-sen, the Qing Dynasty’s most prominent critic. Revolutionaries began to mobilize in earnest during the fall of 1911, gradually taking control of cities and provinces throughout China. In December 1911, the revolutionaries captured the city of Nanjing, thereby bringing an end to the Qing Dynasty. On January 1, 1912, Sun Yat-sen was inaugurated as provisional president of the new Republic of China.

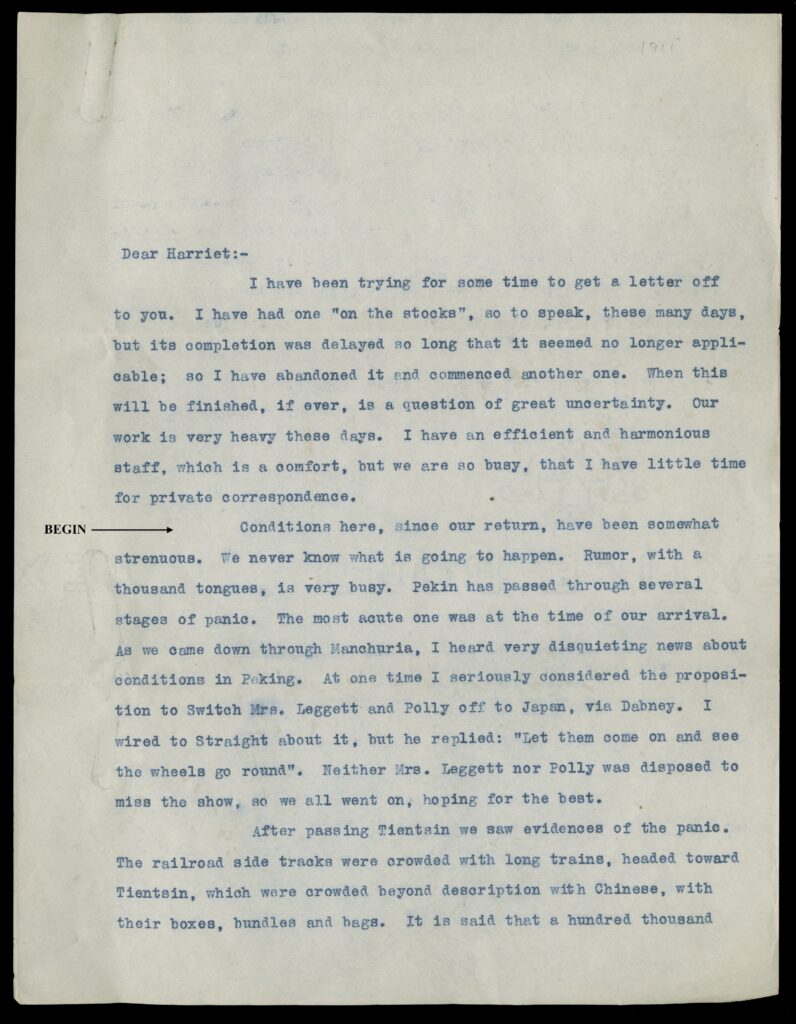

Foreigners both within and outside of China followed the unfolding revolution with great interest. William J. Calhoun, the United States Minister to China from 1901 to 1913, described the tumultuous state of affairs in Peking (Beijing) in a letter he wrote to his sister-in-law, Harriet Monroe, on the eve of Sun Yat-sen’s inauguration. In his letter Calhoun expressed pessimism about the revolution and uncertainty about where he and other foreigners would fit into the emerging Republic of China. Calhoun also draws attention to the foreign districts as key sites of the revolution, noting how Qing officials soft refuge in the foreign districts because of their peculiar legal status within the empire.

William Calhoun to Harriet Monroe (1911)

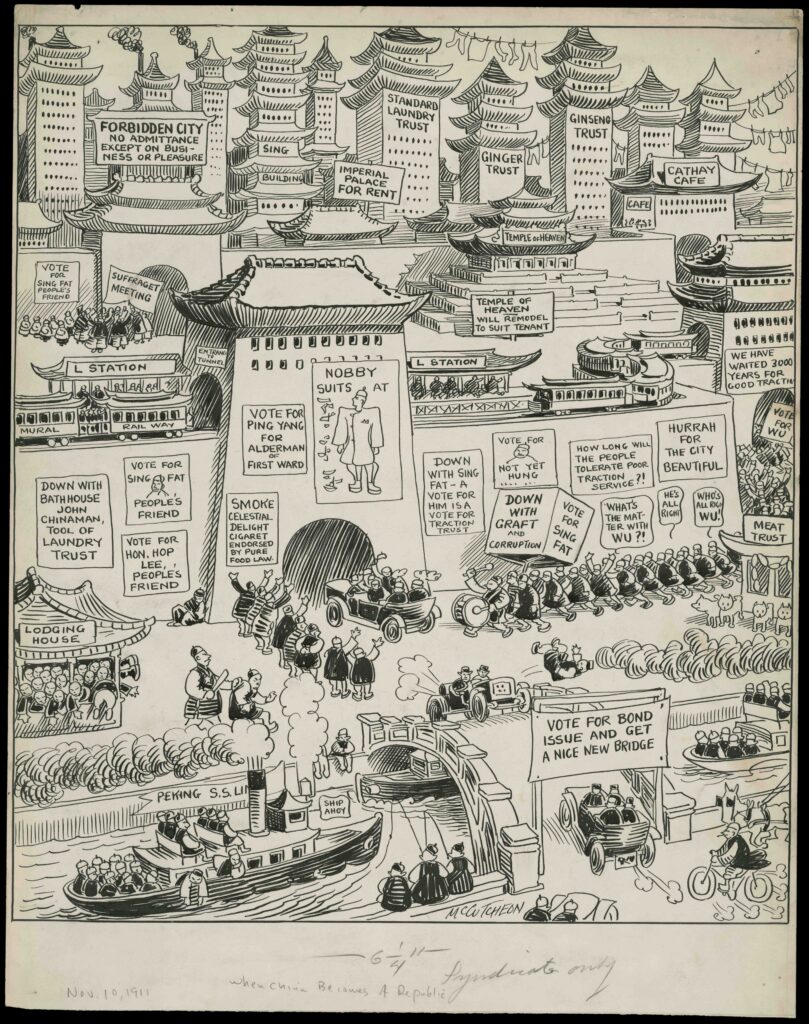

Just as Chinese revolutionaries struggled to define the shape of the new republic, Western observers had their own ideas about what was to come. The final document in this section, an editorial cartoon by John T. McCutcheon, offers one American’s opinion about the future Republic of China and its people. As McCutcheon’s cartoon suggests, many observers in the United States anticipated that China’s revolution might open China to new business ventures and internal improvements, such as the expansion of railroads.

Questions to Consider

- Look carefully at the map of the foreign quarter. How was the foreign quarter divided up? Does the map suggest anything about the relationship between the foreign quarter and the rest of the city? What kinds of information does the map offer about the foreigners’ experience during the siege? How might the map look if drawn by Boxers?

- How would you characterize Calhoun’s feelings about the unfolding revolution? What aspects of the revolution concerned Calhoun the most? What can the letter tell us about Chinese responses to the revolution?

- Describe what you see happening in John McCutcheon’s editorial cartoon, “When China becomes a republic.” Which features of McCutcheon’s imagined cityscape seem most prominent? What visual symbols can you identify? What message(s) do you think McCutcheon sought to convey with this cartoon?

- Compare the views of China offered in William Calhoun’s letter and John McCutcheon’s editorial cartoon. How similar or different were Calhoun and McCutcheon’s perceptions of the revolution?

Reconnecting with the West

The Republic of China’s transformation into the socialist People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949 redefined China’s ties to the outside world. Cold war politics, combined with underlying anti-foreign sentiments, led China’s leaders to cultivate diplomatic relationships with other communist powers and break off ties to the West. During the 1960s, however, tensions between China and the Soviet Union encouraged China and the United States to reconnect.

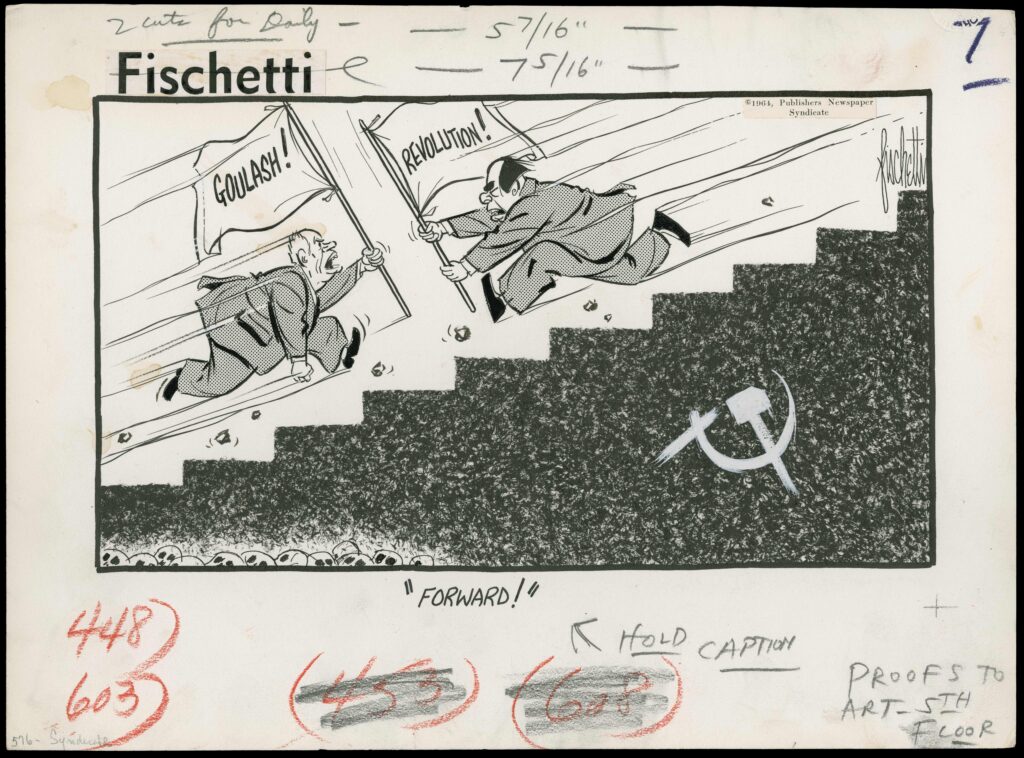

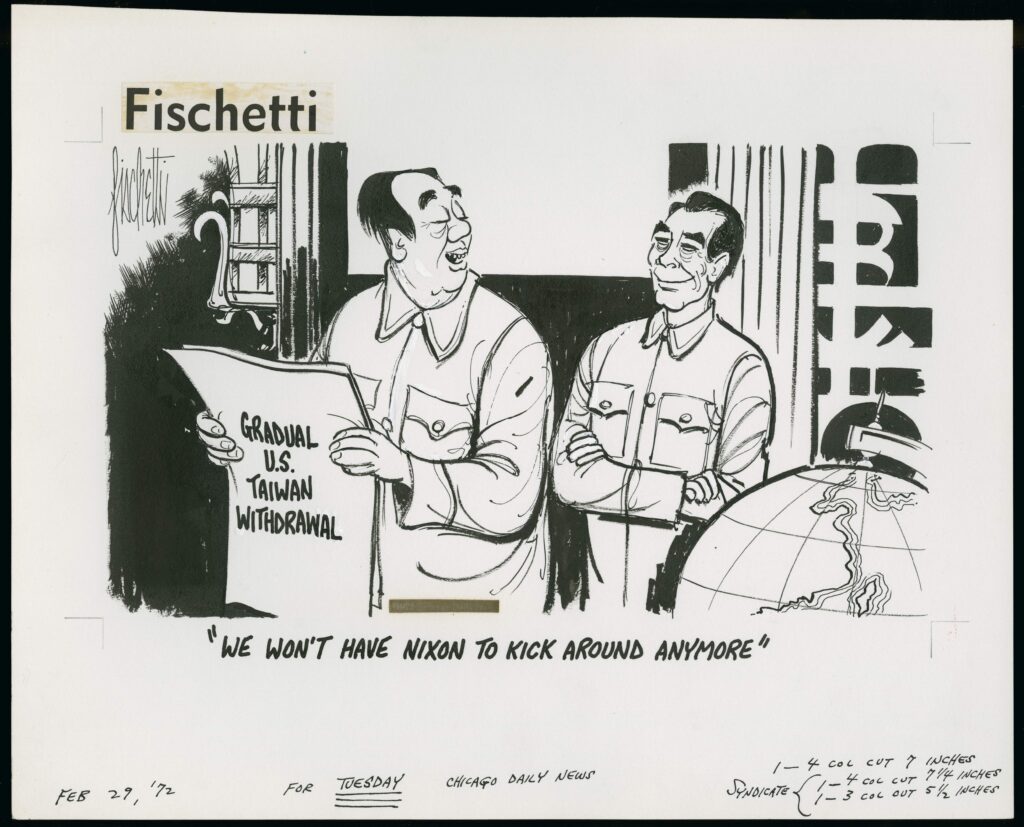

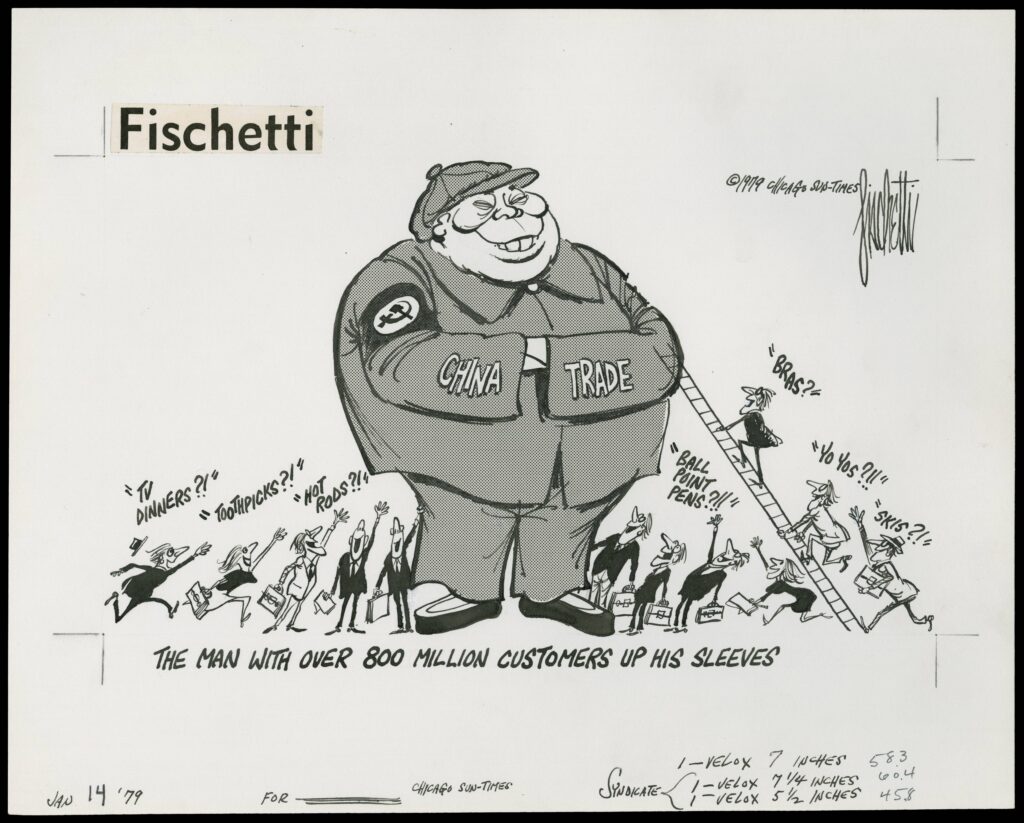

Just as Western observers had watched China’s internal turmoil in the early 1900s with great interest, so too did they follow the late twentieth century evolution of China’s foreign affairs. American political cartoons from this period offer an interesting perspective on these events and American sentiments about them. John Fischetti was a nationally syndicated editorial cartoonist whose work appeared in major newspapers like the Chicago Sun-Times and Chicago Daily News. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Fischetti drew cartoons that chronicled China’s reopening to the Western world. The three cartoons below are original proofs that Fischetti sent to be reproduced in the Chicago Sun-Times and Chicago Daily News. They offer insight into some of the cultural assumptions of the artist and period, as well as information about the people and events they depict.

Fischetti drew the first cartoon (entitled “Forward!”) for the November 10, 1964, edition of the Chicago Daily News. During the 1960s, relations between the Soviet Union and PRC, then the two largest communist countries in the world, turned sour over conflicting national interests and ideological differences. The cartoon underscores the growing divide between the two nations by depicting Nikita Khrushchev, first secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (on the left) and Mao Zedung, chairman of the Communist Party of China (on the right) charging at each other.

Tensions between China and the Soviet Union opened space for new relations between China and the United States. The second cartoon below, printed in the February 29, 1972, edition of the Chicago Daily Sun alludes to President Richard Nixon’s historic visit to China in 1972. Nixon was the first president to visit the PRC since it was established in 1949. Nixon’s key objective for the visit was to settle Taiwan’s political status in relation to the PRC. During the visit, Nixon agreed to pull U.S. forces out of Taiwan. The cartoon depicts Mao Zedung (on the left) and Zhou Enlai, the first premier of the PRC, who was instrumental in shaping China’s foreign policy.

President Nixon’s visit to China marked the first step toward the formal resumption of diplomatic relations between the U.S. and China on January 1, 1979. The final cartoon in this section, which appeared in the January 6, 1979, edition of the Chicago Sun-Times, offers Fischetti’s view on the economic implications of this development. Fischetti shows American businessmen clamoring for the attention of Deng Xiaoping, leader of the PRC from 1978–1992.

Questions to Consider

- What kinds of symbols does Fischetti use in the “Forward!” cartoon? How would you explain this cartoon’s message? Why do you think Fischetti entitled the cartoon “Forward!”?

- Where do you think the imagined scene in the cartoon entitled “We won’t have Nixon to kick around any more” was taking place? What kinds of symbols does Fischetti use to identify the two men? What message does the cartoon convey about the relationship between the U.S. and China?

- How has Fischetti distorted the figures depicted in the “Man with over 800 million customers” cartoon? How would you describe the relationship between the central figure (Deng Xiaoping) and the people surrounding him?

Political Cartoons

Other Images

Letters

Further Reading

Colin Mackerras. China in transformation 1900-1949, 2008.

John Gittings. The Changing Face of China: from Mao to Market, 2005.

Jonathan Spence. The Search for Modern China, 2013