Introduction

Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote, published in 1605, has been described as the first modern novel—and the first postmodern novel. The novel’s parody of chivalric romances seems to draw to a close a feudal society based on family lineage and rigid social hierarchy. It opens up the possibility of the modern individual, shaped by his or her own beliefs and actions. “Each man is the child of his deeds,” Don Quixote tells us.

Critics have also described the novel as a work of metafiction—fiction that self-consciously reveals its own techniques—in ways that anticipate postmodern writing. Think of the proliferation of authors, editors, and translators, of found manuscripts and uncovered histories that Cervantes provides. Think of the very nature of Don Quixote’s madness: he has internalized the chivalric world he read about in books and now seeks to impose that imaginary world on the people and things he encounters. These elements in the novel encourage us to consider the problem of representation (the relationship between reality and fiction) itself. They encourage the reader to ask questions: Who is telling this story? How are they telling it? What is the reader’s role in the narrative’s creation?

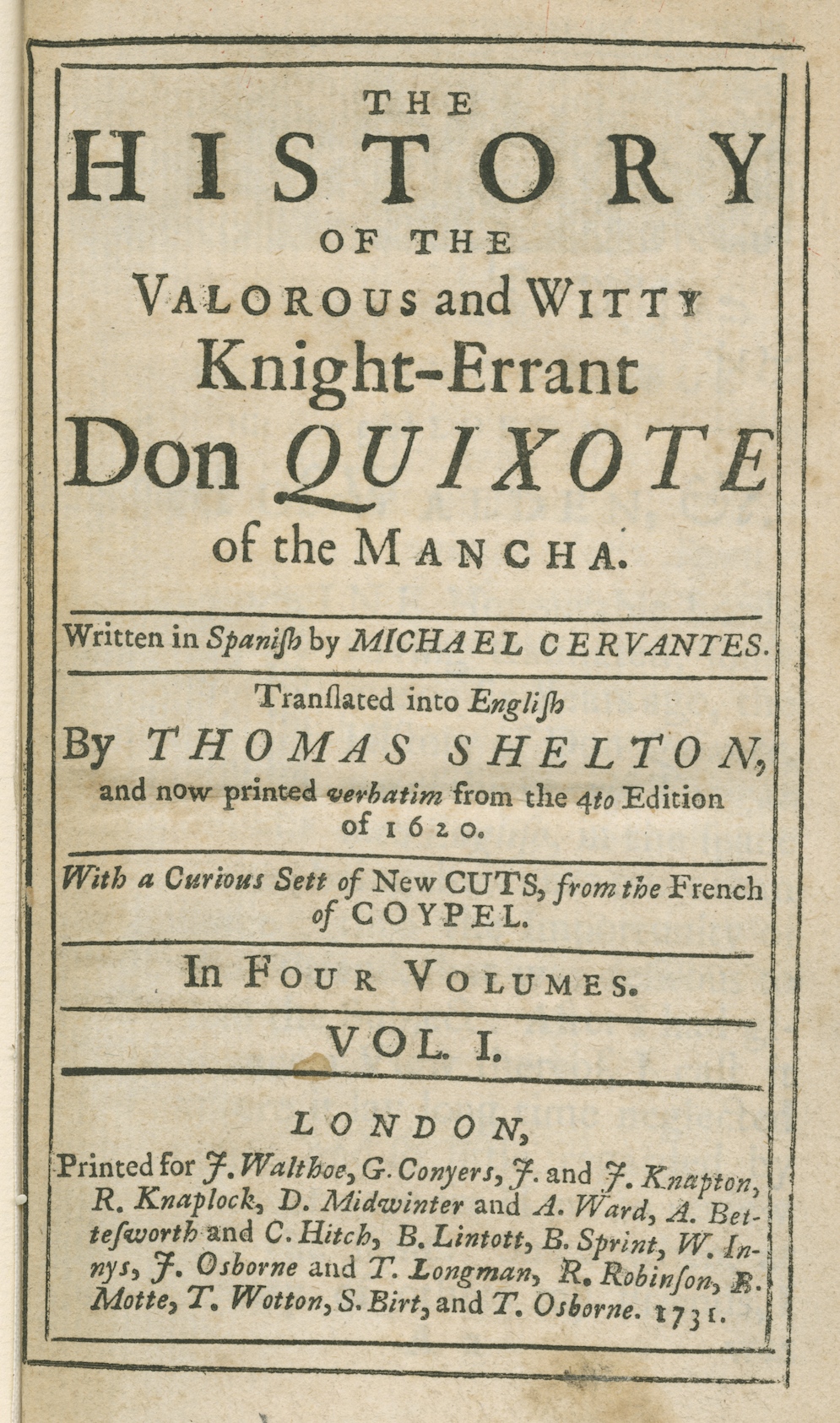

Yet if Don Quixote strikes readers today as an uncannily modern work, the novel spoke powerfully to seventeenth-century readers as well. Don Quixote was an immediate success in Spain, throughout Europe, and, thanks to Spain’s extensive empire, the Americas. Originally published in Madrid in 1605, the first volume was translated into English, Italian, French, and German in less than a decade. Cervantes published the second volume in 1615.

While critics often remark on the novel’s ability to reach readers across different cultures and historical periods, it is worth noting that much of the work’s power and relevance comes from Cervantes’ skillful navigation of the specific social conditions in Spain around 1600. Roughly 100 years earlier, Spain had become a politically unified country, ruled by Catholic monarchs, and had begun a course of exploration and conquest of the Americas and Asia. During Cervantes’ lifetime (1547–1616), the country profited from its vast, New World empire and maintained a strong political and military presence in Europe.

At the same time that Spain became such a formidable global power, the government embarked on a profound internal remaking of the country by means of the Inquisition. Medieval Spain had large Muslim and Jewish populations and is considered to have been the most diverse and tolerant society in western Europe. Moors (North African and Arab Muslims) ruled large swaths of the Iberian Peninsula from the eighth century through the fifteenth. Regions under Christian control were also multireligious. As scholar Carroll B. Johnson notes, “In an age when other European monarchs styled themselves ‘Defender of the [Christian] Faith,” the king of Castile was proud to be known as ‘King of the Three Religions.’”

Spain’s relatively tolerant social structure began to change during the fourteenth century with increasingly violent persecution of Jews. The persecution became official policy under Queen Isabel and King Ferdinand (the same monarchs who launched Columbus on his journey to the Caribbean). In 1478, with the pope’s sanction, the monarchs created the Inquisition, a new legal system dedicated to seeking out and punishing heresy (religious beliefs that contradicted Roman Catholic teachings). In 1492 Jews were given the choice of leaving the country or converting to Christianity (becoming conversos). Muslims, at first, were subject to conversion (becoming Moriscos) but, in the early seventeenth century, were expelled from the country. People accused of heresy were subject to torture, loss of property, and, if convicted, burning at the stake. In the century that followed 1492, Spanish society became organized around a new division between Old Christians (whose families had always been Christian) and New Christians (the converts and their descendants). New Christians were systematically excluded from participation in the leading political and religious institutions.

Cervantes could not help but be affected by these conflicts within Spanish society. As Johnson explains, not only was Cervantes himself probably descended from conversos, but every writer was subject to scrutiny by the Inquisition’s censors. The Inquisition “exercised absolute control over what could and could not be published” and carefully suppressed statements that appeared unorthodox or critical of the church or government. Writers had to avoid any suggestion of dissent. For Cervantes, Johnson argues, the solution was to develop a style rich in ambiguity and a “pervasive and systematic irony.” The very qualities that help Don Quixote resonate with modern readers were essential to protecting the author and getting his work past the censors.

The documents that follow offer teachers and students a deeper understanding of the world that Cervantes—and Don Quixote—negotiated. They include seventeenth-century maps of Spain and Europe, a letter from King Philip II regarding the Moriscos, illustrations from the books that drove Quixote mad, and, finally, evidence of the work of the Inquisition’s censors.

Please consider the following questions as you review the documents

- What was the geography of Spain in the seventeenth century? Where is La Mancha? What regions does Quixote travel through?

- How were Moriscos (descendants of Moors) regarded by the Spanish government and the Christian majority in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Spain? How can knowledge of this history help us understand Cervantes’ representations of Moriscos in Don Quixote?

- What were the books that Quixote loved and that drove him insane? How do Don Quixote and Don Quixote—the character and the novel—compare to the knights and chivalric tales that he so admired?

- How did the Inquisition shape the world of letters in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Spain? How did Cervantes respond to the Inquisition’s practice of censorship in his representation of the “inquisition” into Quixote’s library in Volume 1, Chapter 6?

The Geography of Quixote’s World

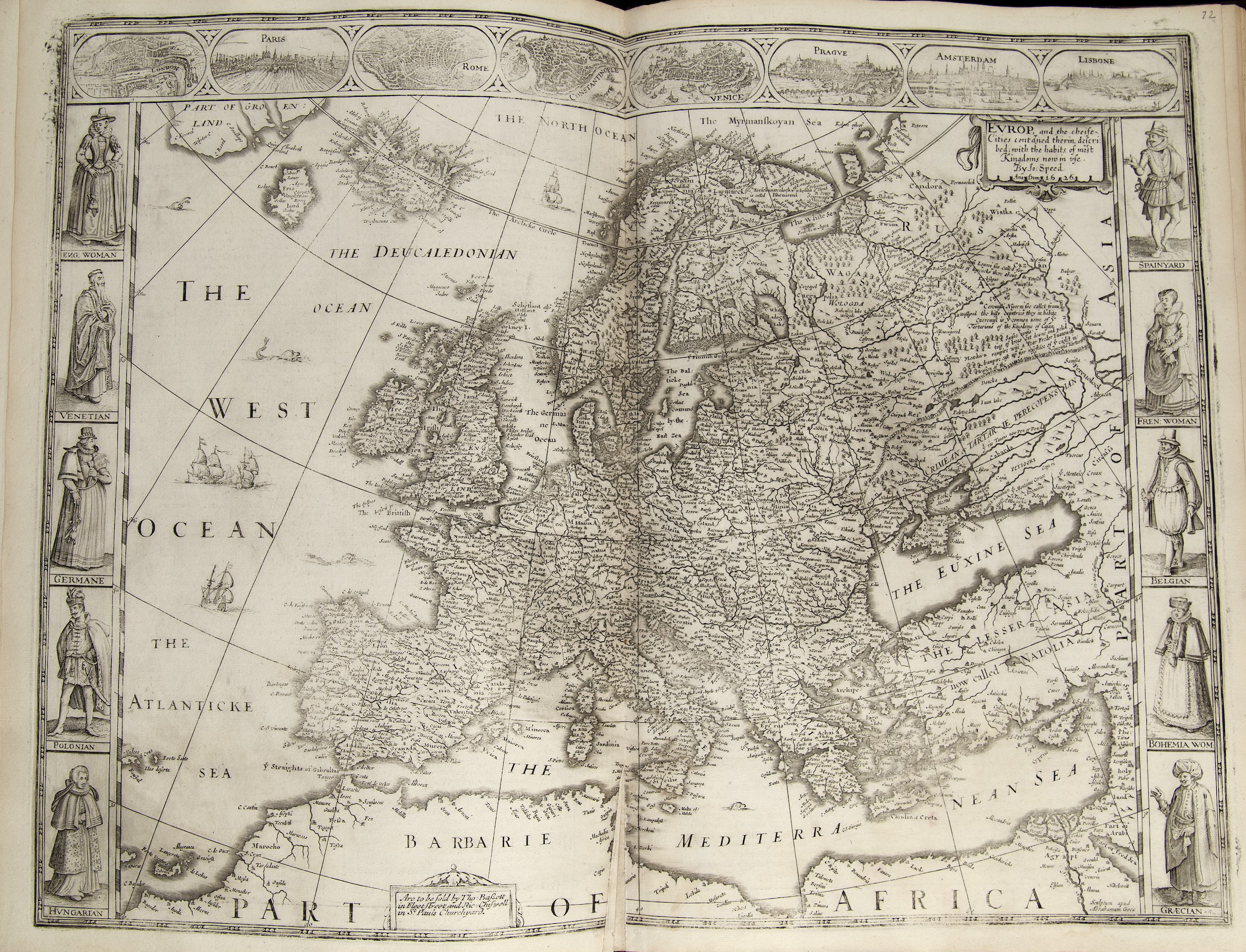

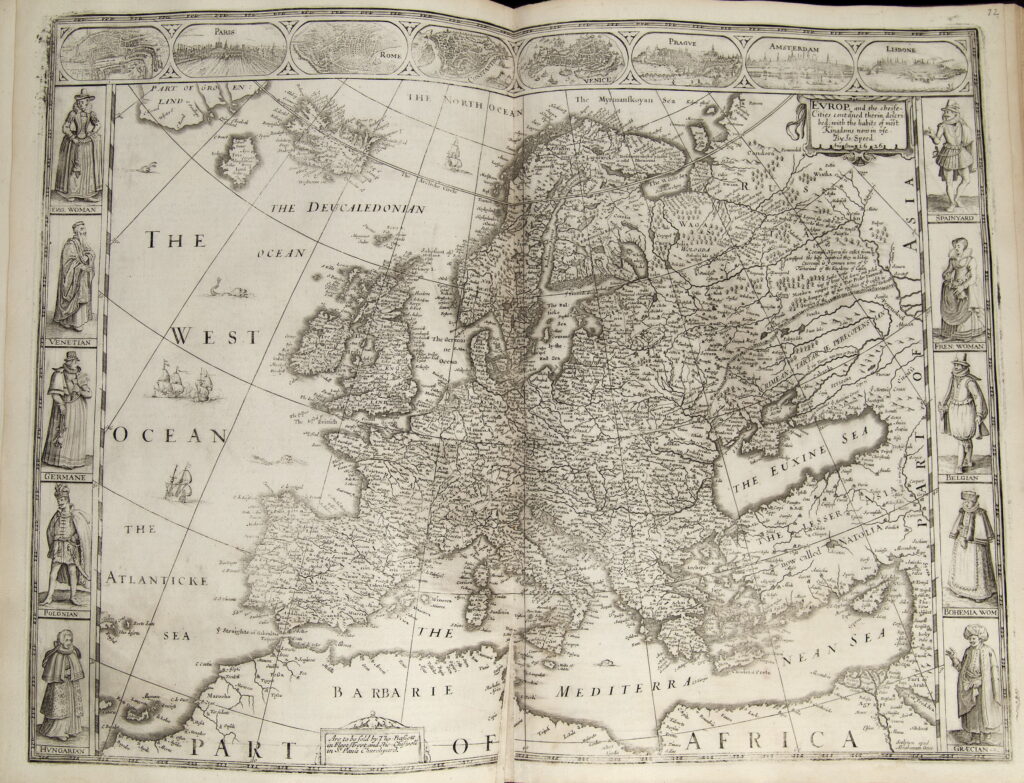

Speed, Evrop and the Cheife Cities Contayned Therin

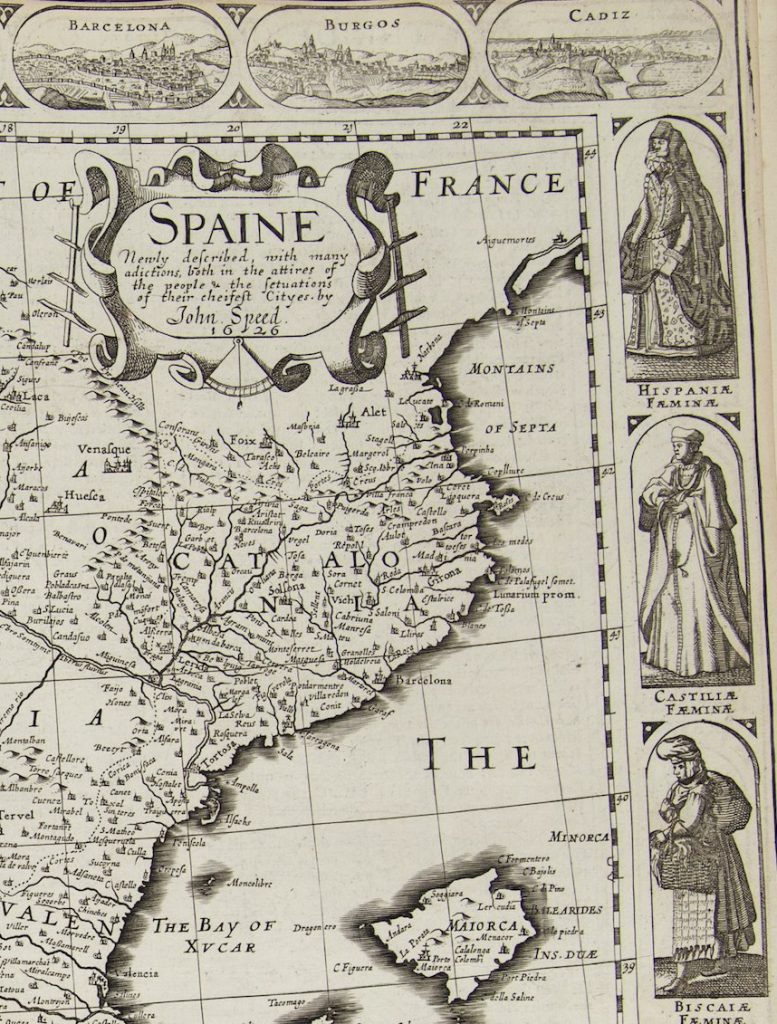

The maps in this section can help orient readers to the geography of Cervantes’ and Quixote’s world. However, they should not be approached as neutral or objective documents. The first two maps are taken from John Speed’s The Theatre of the Empire of Great-Britain. This English atlas is best remembered now for having provided the first detailed maps of English and Welsh counties and towns when it was originally published in 1611 and 1612. The maps below were first printed in 1627 as part of the atlas’ fifth book, A Prospect of the Most Famous Parts of the World, viz. Africa, Europe, America.

Relations between England and Spain were tense during much of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and twice broke into war (1587–1604 and 1654–1660). The antagonism was due, in part, to religious differences: Spain’s monarchy was loyal to the Roman Catholic Church, while the English rulers Elizabeth I and James I supported Protestantism and the Church of England. Furthermore, Spain reached the height of its imperial powers during this period. Spain was the dominant European power in the Americas and derived immense wealth from the gold and silver mines in its colonies there. England sought not only to remain independent of Spanish rule, but to build its own American empire.

Speed, Spaine

The title of Speed’s atlas signals his commitment to English imperialism and his description of the Spanish is particularly critical. Speed claims that Spain is more sparsely populated than the rest of Europe because its women are less fertile. Furthermore, he finds the Spanish “Superstitious beyond any other people … For how can hearty [religious] devotion stand with cruelty, leachery, pride, idolatry, and those other Gothish, Moorish, Jewish, Heathenish conditions of which they still favor.”

Even so, Speed’s maps usefully represent the knowledge available in Europe of regions and towns in Spain and provide a sense of Spain’s relationship to North Africa (“Barbarie”) and the rest of Europe. Note that Portugal does not appear as an independent country; it was incorporated into Spain from 1580 to 1640.

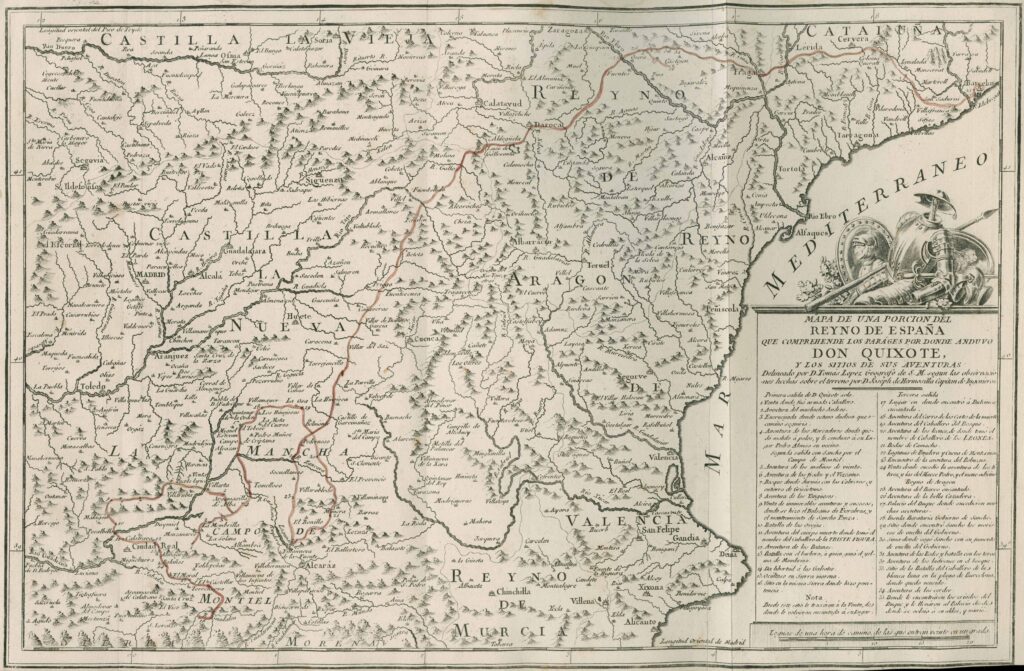

The final map below traces Don Quixote’s route through La Mancha and eastern Spain. Literary critic Carroll B. Johnson notes that, while Don Quixote sought to ennoble himself by incorporating his homeland into his name, la mancha “means ‘stain’ in Spanish, and is the name of a region with nothing particular to recommend it: no cities, no illustrious families, the site of no important historical events, a semiarid plain given over mostly to wheat and dotted with windmills.” This map appears in a 1780 Madrid edition of the novel, the first in a series of deluxe, illustrated editions printed in Spain.

Questions to Consider

- What information does Speed’s map of Spain include? Can you identify regions, towns, and natural features?

- Examine the portraits that appear in the borders Speed’s maps of Spain and Europe. What differences do you notice in the costumes associated with specific regions in Spain and with different countries in Europe? Is Spain’s association with Moors or Jews evident?

- Describe the cities that appear at the top of both maps. Which cities does Speed consider the major ones of Europe? How do Spanish cities compare?

- Evaluate the map of Don Quixote’s route based on your knowledge of the novel. Does the novel provide sufficient information to create a precise map of his route?

- Why do you think printers in the late eighteenth century were interested in mapping Quixote’s route? How does the map contribute to the text’s playful claims to be a true history?

The Politics of Quixote’s World I: The Inquisition and the Moors

Cervantes wrote Don Quixote as Spain was completing its transformation from a society in which Muslims, Jews, and Christians lived alongside one another in conditions of relative tolerance to one that would be—at least officially—exclusively Catholic and absolutely intolerant of religious differences.

At the beginning of the eighth century, North African and Arab Muslims, known as Moors, invaded the Iberian peninsula and, for over 700 years, remained a significant presence in the region. At their height, Muslim states, known collectively as al-Andalus, extended across the peninsula into southern France. Beginning in the eleventh century, Christian kingdoms in the north defeated the Muslim states in a series of wars and steadily took control of the peninsula in a process known to the Christians as the Reconquista or “reconquest.” In 1492 the Emirate of Granada, the last Muslim province in Spain, surrendered to Queen Isabel of Castile. She implemented an ultimately unsuccessful policy of forced, mass conversions.

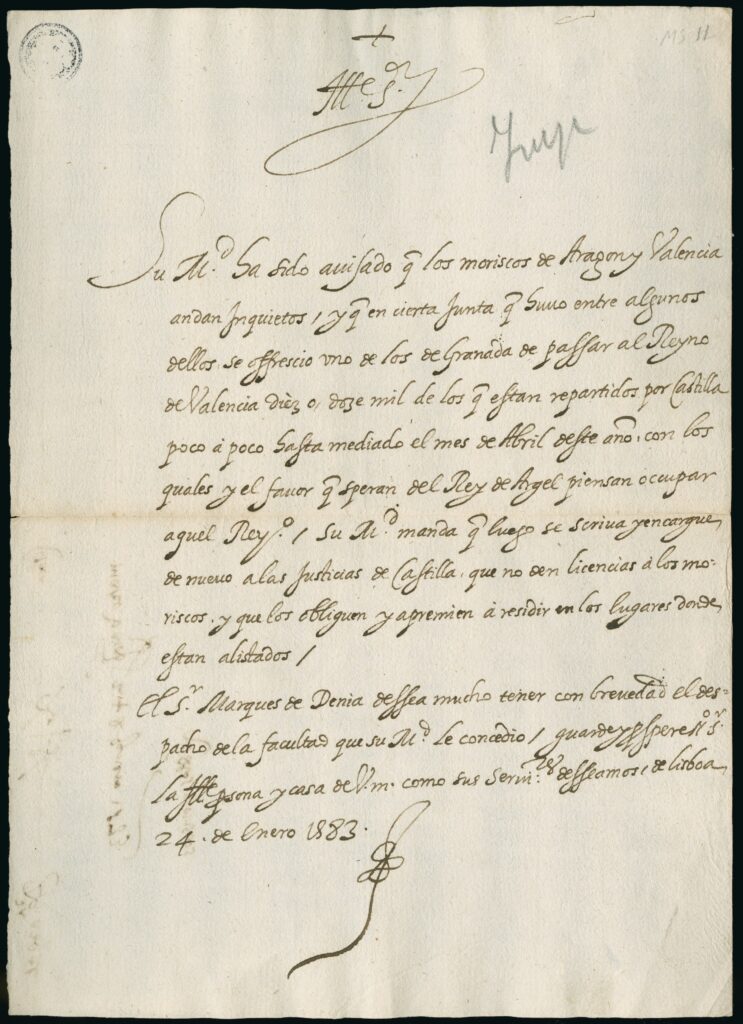

Seventy years later, the Moriscos remained a largely unassimilated population that spoke Arabic, followed Muslim customs, and often practiced Islam in secret. In 1566, suspicious that they might be colluding with Algerians and Turks against Spain, King Philip II ordered Morisco property in Granada to be confiscated and forbade the speaking of Arabic as well as the use of Muslim names or clothing. The Moriscos rebelled and, after their defeat in 1571, the king ordered them deported from Granada and scattered throughout Castile, a province in northern Spain. But a number of religious and political figures urged the crown to expel the Moriscos from Spain entirely, describing them as a disease that threatened to infect the entire political body. On September 22, 1609, the new king, Philip III, ordered their expulsion and, within five years, approximately 300,000 people had been deported to North Africa.

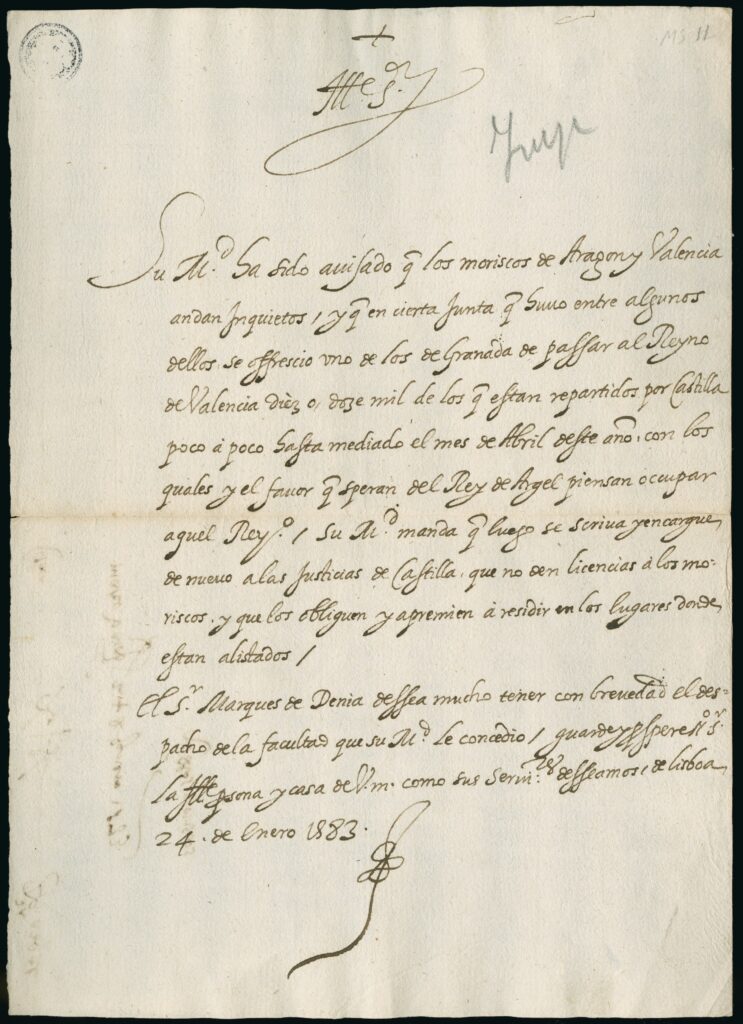

Letter of King Philip II of Spain and Portugal

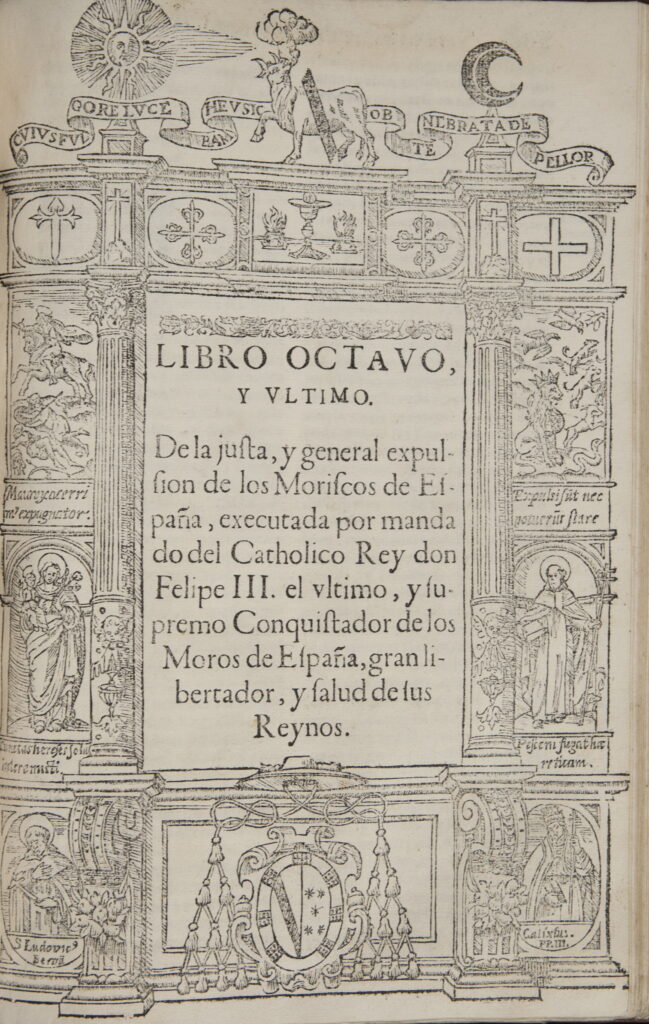

The documents in this section include a 1583 letter written on behalf of Philip II regarding the Moriscos as well as the title page of Jaime Bleda’s Chronicle of the Spanish Moors. Bleda was the priest of a town with a large Morisco population. He campaigned for years to persuade Philip III to expel them from Spain.

Questions to Consider

- Examine the letter on behalf of Philip II and read the translation of the first paragraph. What is the purpose of the letter? What are Philip’s fears regarding the Moriscos? How does his government attempt to manage the threat he believes they pose?

- Examine the title page of the final book of Bleda’s Chronicle of the Spanish Moors. What can you learn from the title about Bleda’s views on the expulsion of the Moriscos? What is the significance of referring to Philip III as a conquistador? How do ideas of conquest and expulsion frame the history of a population that had inhabited the Iberian Peninsula for almost 1,000 years?

- Consider Cervantes’ frequent references to Moriscos in Don Quixote in light of the government’s policies and the anti-Morisco views of many Old Christians. Why do you think Cervantes attributes most of the “found” history of Don Quixote to the “Arab historian” Sidi Hamid Benengeli (also spelled Cide Hamete)? How do you interpret Morisco figures like Zoraida (Vol. 1, Ch. 37–42) and Ricote (Vol. 2, Ch. 54)?

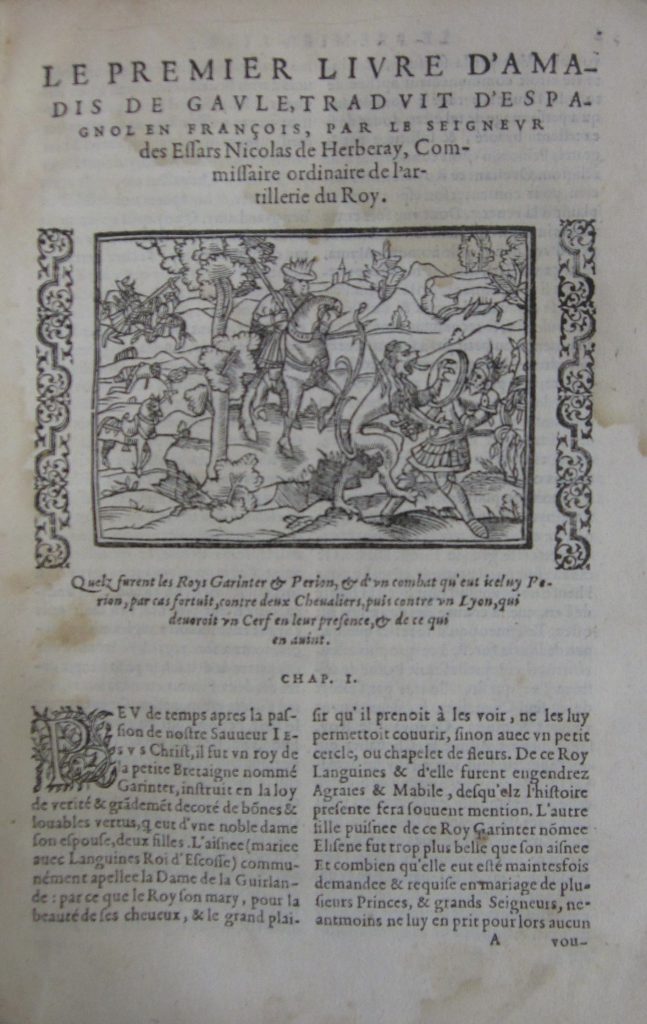

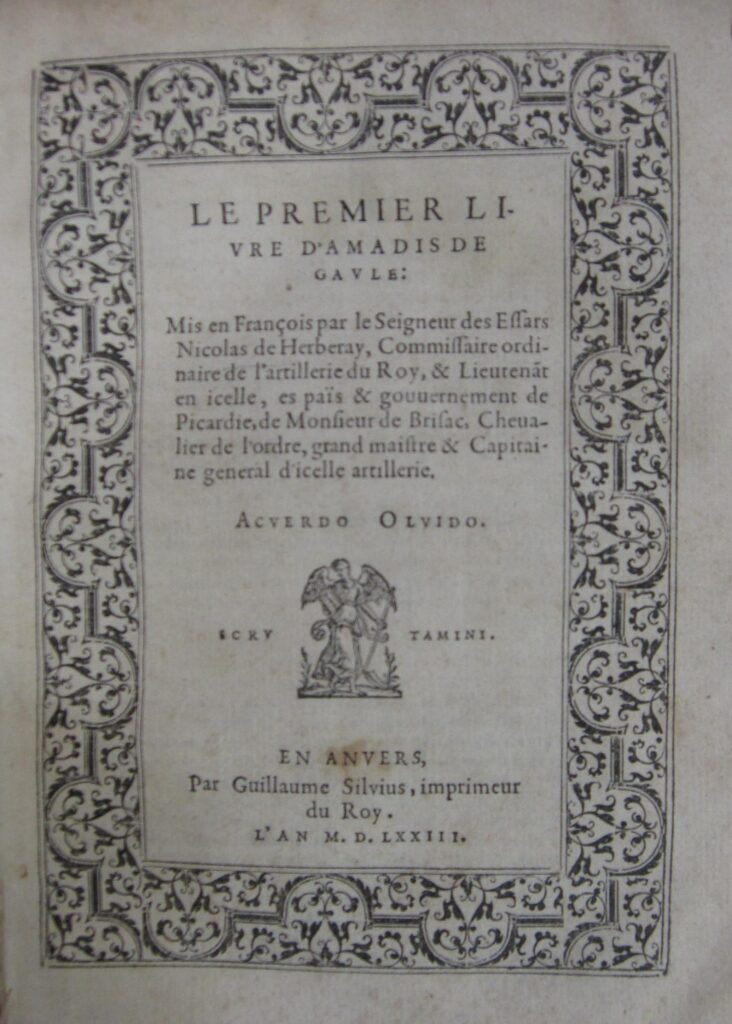

Quixote’s Reading: The Chivalric Romances

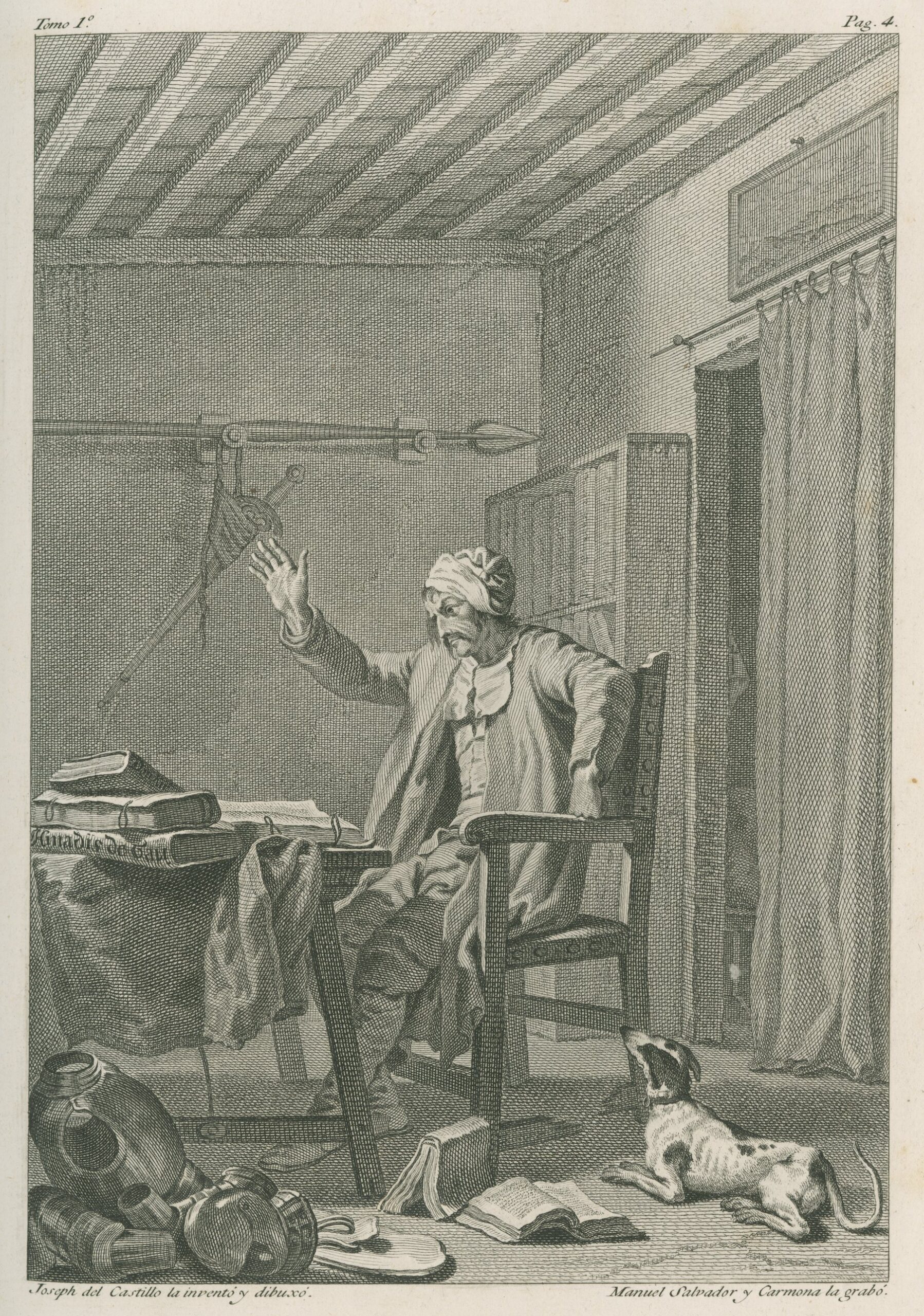

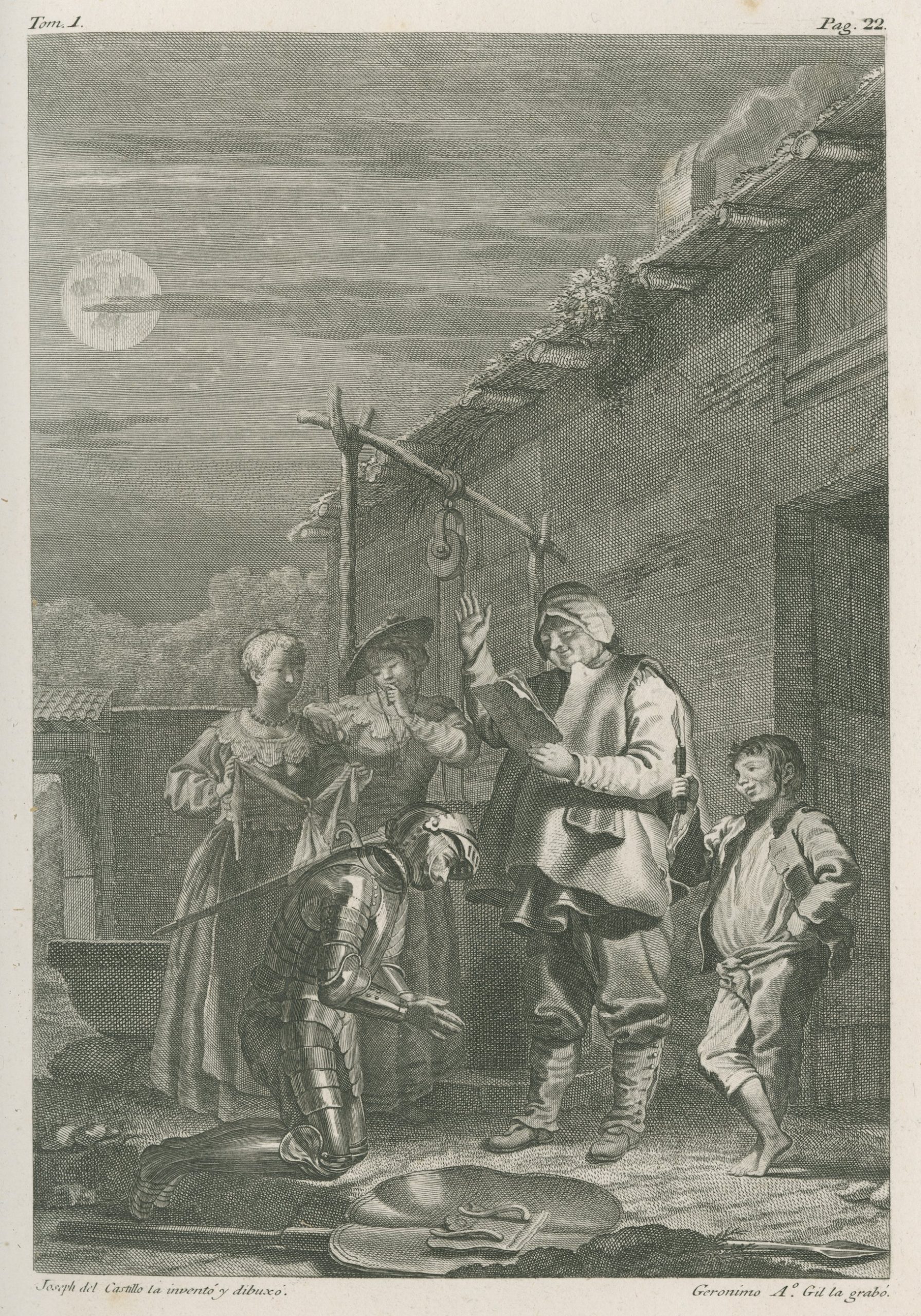

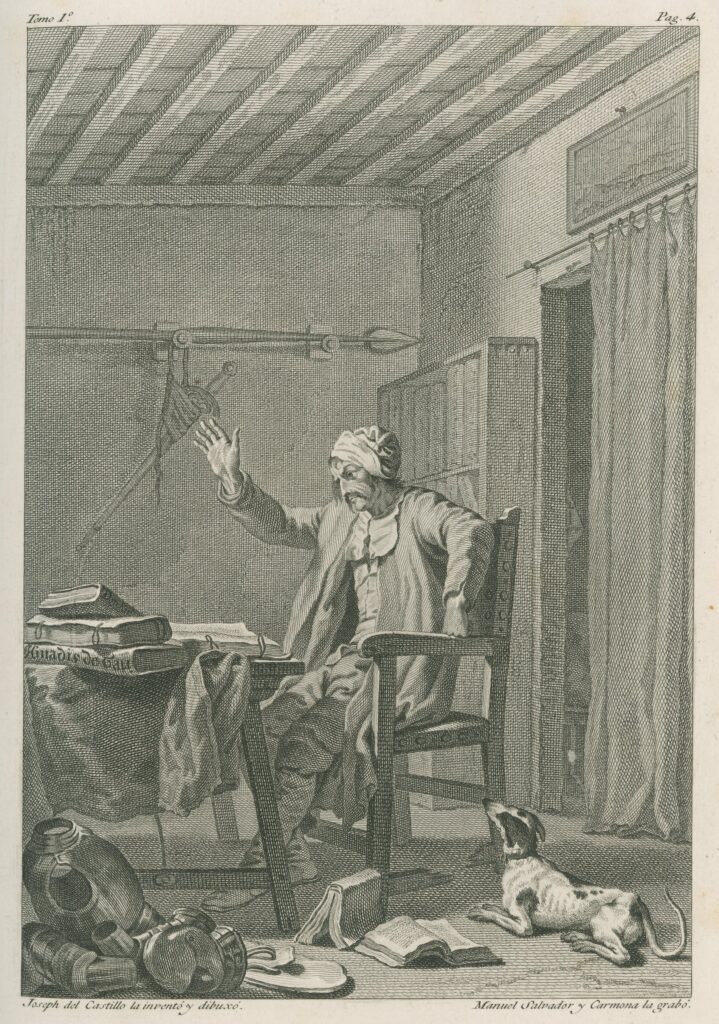

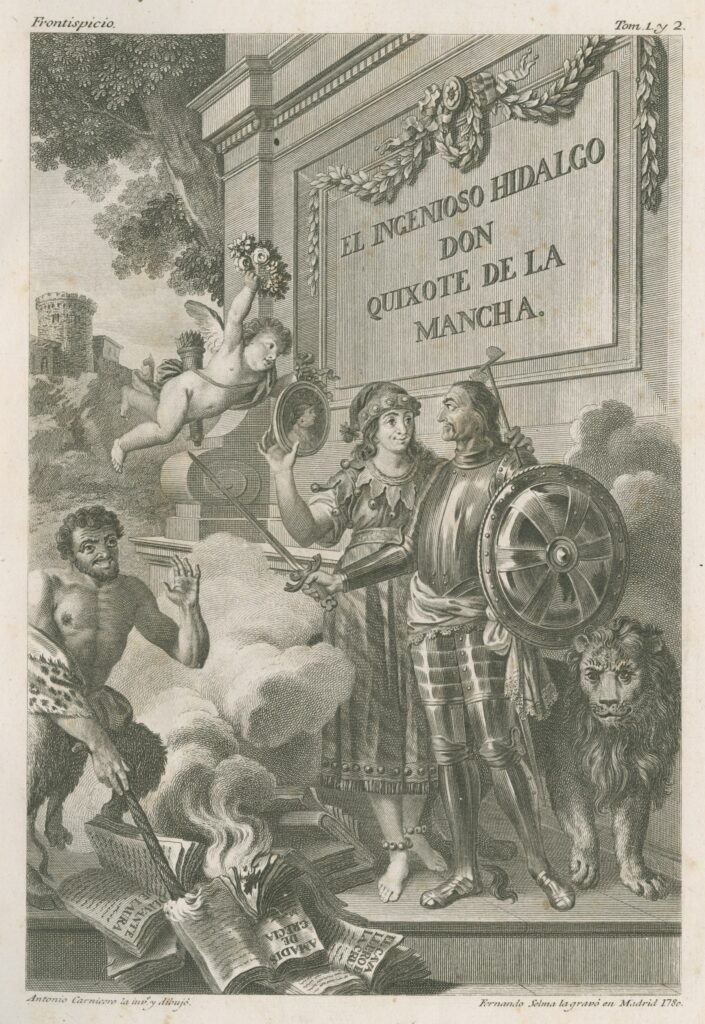

de Cervantes Saavedra, The Ingenious Nobleman Don Quixote de la Mancha

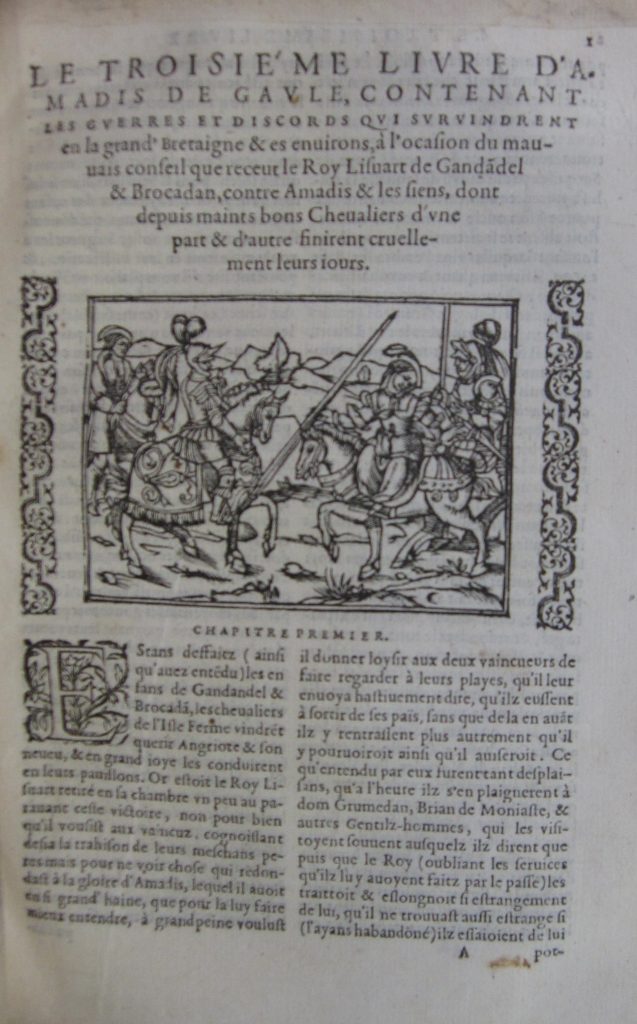

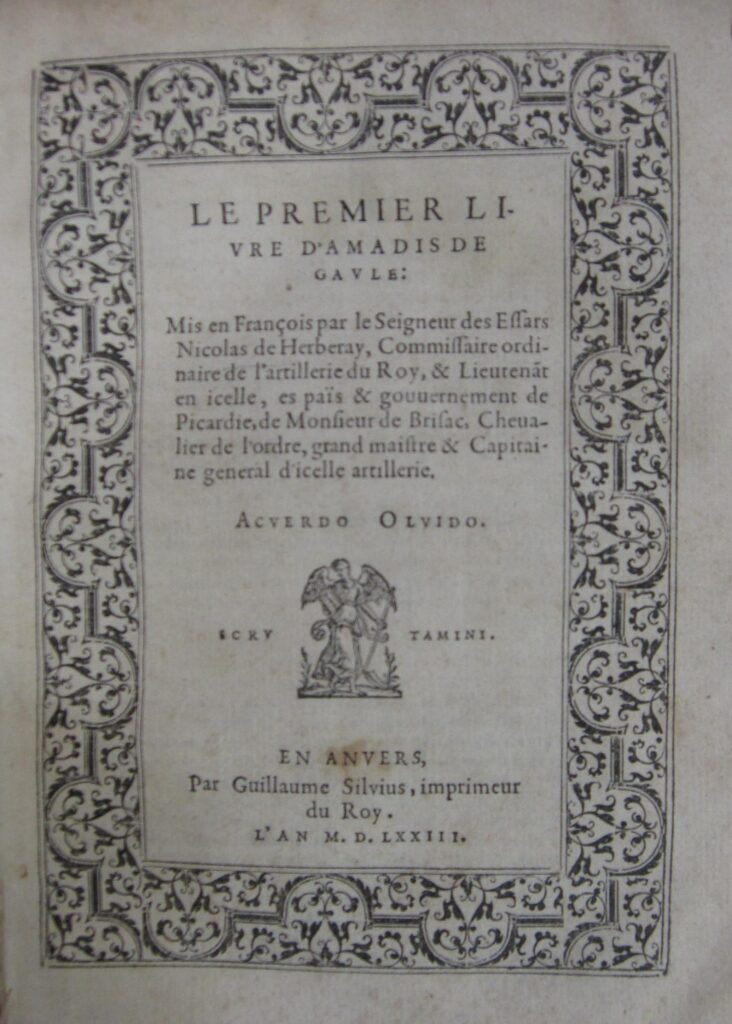

In the first chapter of Don Quixote, the narrator tells us, “Don Quixote so buried himself in his books that he read all night from sundown to dawn, and all day from sunup to dusk, until with virtually no sleep and so much reading he dried out his brain and lost his sanity.” One of the books that has driven Quixote to madness is Montalvo’s Amadís of Gaul, a Spanish chivalric romance, published in 1508, that became a bestseller across Europe for the next century. Montalvo’s 12-volume series on the adventures of Amadis, his sons, and his nephews may have been scorned by a few scholars, but was passionately read by monarchs and saints, conquistadors and commoners “from Scandinavia to Sicily,” according to literary critic Diana de Armas Wilson. The stories portrayed heroic knights, loyal squires, and virtuous ladies as well as evil (often Muslim) antagonists and included plenty of sword fights and magic potions.

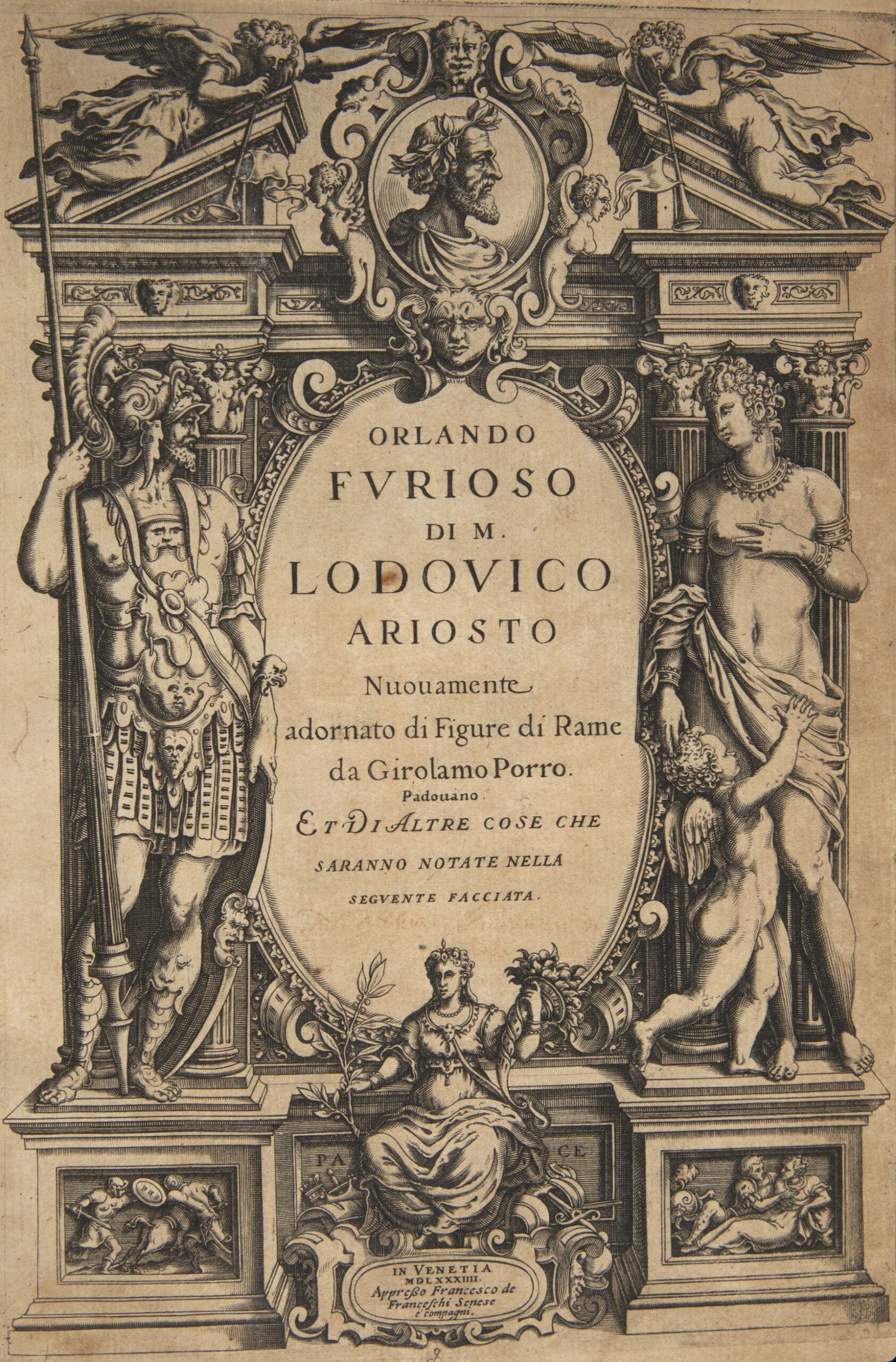

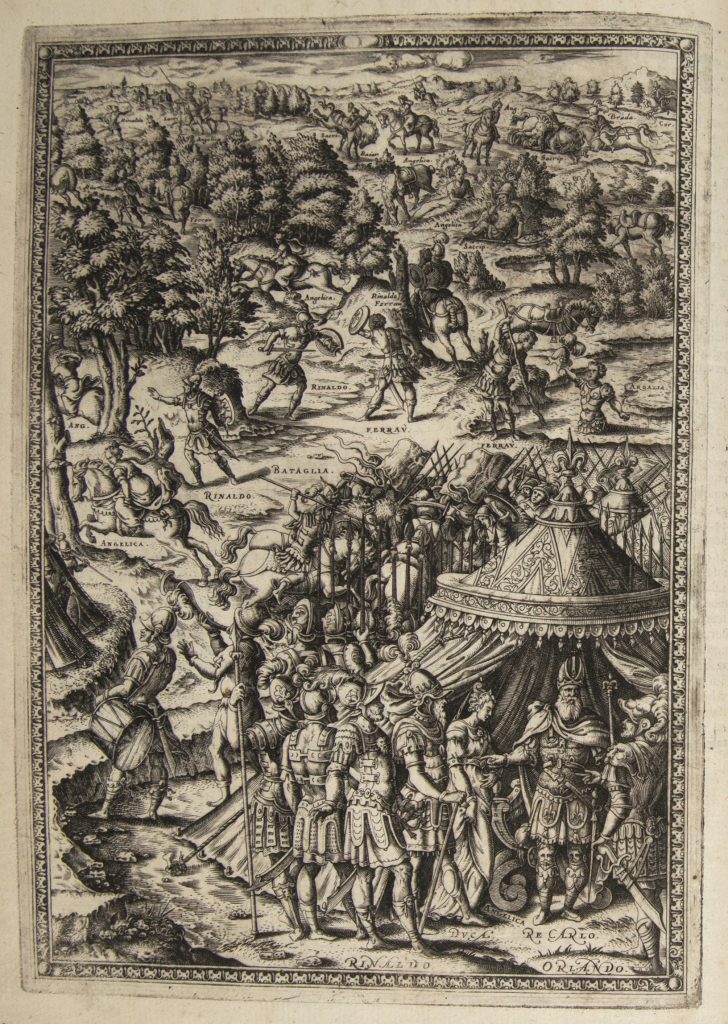

Another important influence on Quixote (and object of Cervantes’ parody) is Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando furioso, an Italian epic poem, published in 1516. Orlando furioso (“Orlando insane”) follows the plight of the knight Orlando (usually Roland, in English) of King Charlemagne’s court, who discovers that the woman he loves has eloped with a Moor in the enemy’s army. Orlando goes insane with rage, pulls up trees, and generally storms around until, as Carroll Johnson explains, another knight “flies to the moon on a magical horse, finds Orlando’s brains in a glass vial, and returns with them to earth.”

The engravings in this section from a sixteenth-century French edition of Amadis and an Italian edition of Orlando furioso suggest the kind of imaginary world that Quixote inhabited through these books. Engravings from the 1731 English and 1780 Spanish editions of Quixote offer an interesting contrast. While the popularity of the chivalric romance and epic declined dramatically during the sixteenth century, Quixote would continue to be widely read and beloved for centuries to come.

Questions to Consider

- What kinds of people, animals, and events do the illustrations from Amadis and Orlando portray?

- How would you compare the knights in the earlier works to the representations of Quixote as a knight?

- Consider the settings and captions in the Quixote illustrations. How does his world compare to Amadis’s and Orlando’s? Why do you think he would prefer to live in theirs?

- Can the same reader enjoy both? Or does Quixote spell the end of chivalric tales?

The Politics of Quixote’s World II: Reading and the Inquisition

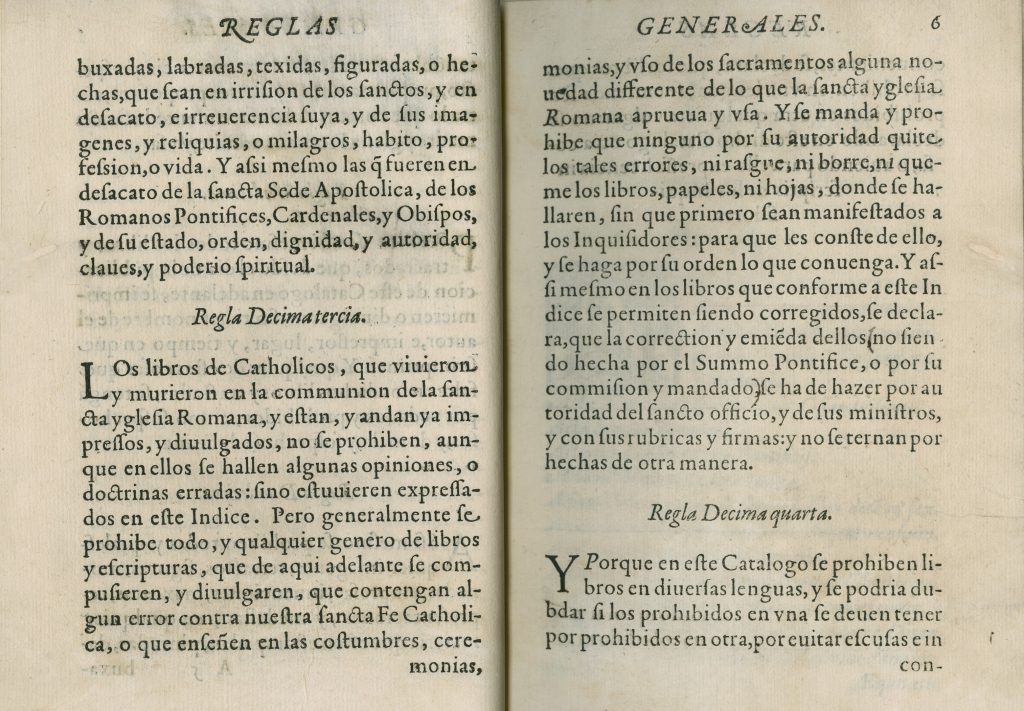

In order to prevent the spread of heresy, the Spanish Inquisition exercised tight control over which books were published and sold in Spain. Every new book went through a process of review and licensing before it could be printed. Books already in circulation could be denounced and banned by later censors. For this reason, the Inquisition regularly published indexes, or lists, of prohibited books, revising and updating these lists as the Catholic Church’s precepts changed over time. Sometimes entire books were banned, and, especially in the early decades around 1500, the Inquisition staged ceremonial book burnings. Thousands of Jewish and Arabic books and manuscripts were destroyed in this way. Over the course of the sixteenth century, Inquisition officials increasingly chose to censor works more selectively. They carefully blotted out specific passages considered heretical, allowing the remainder of the work to survive for readers.

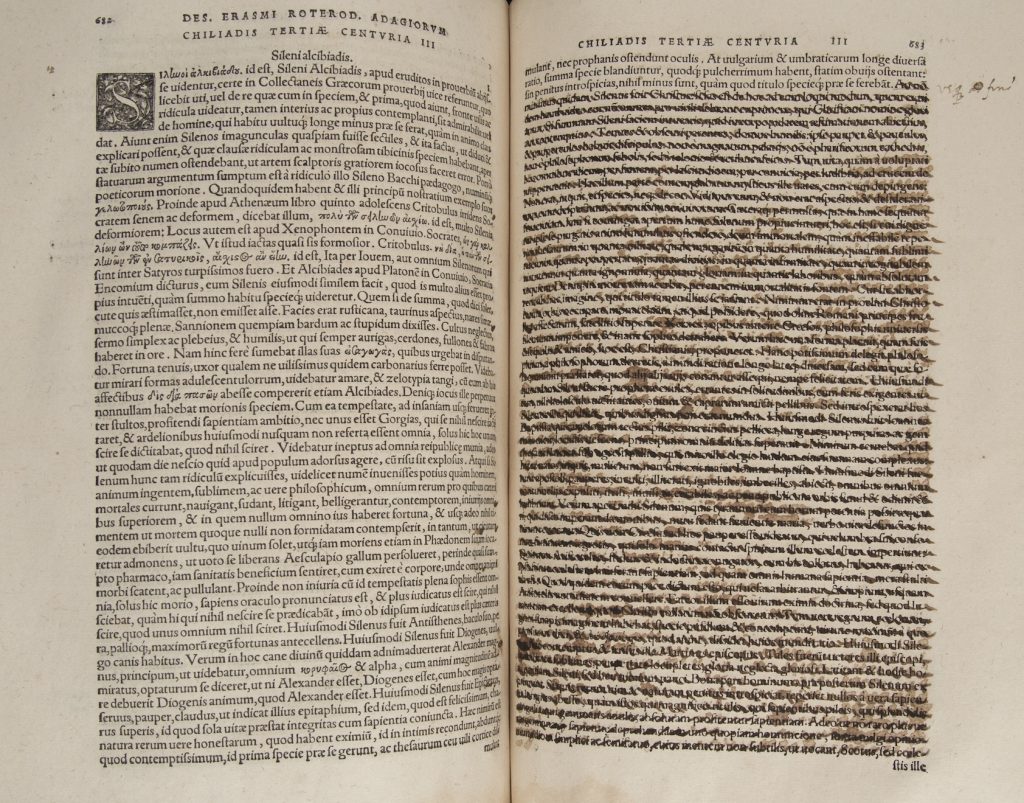

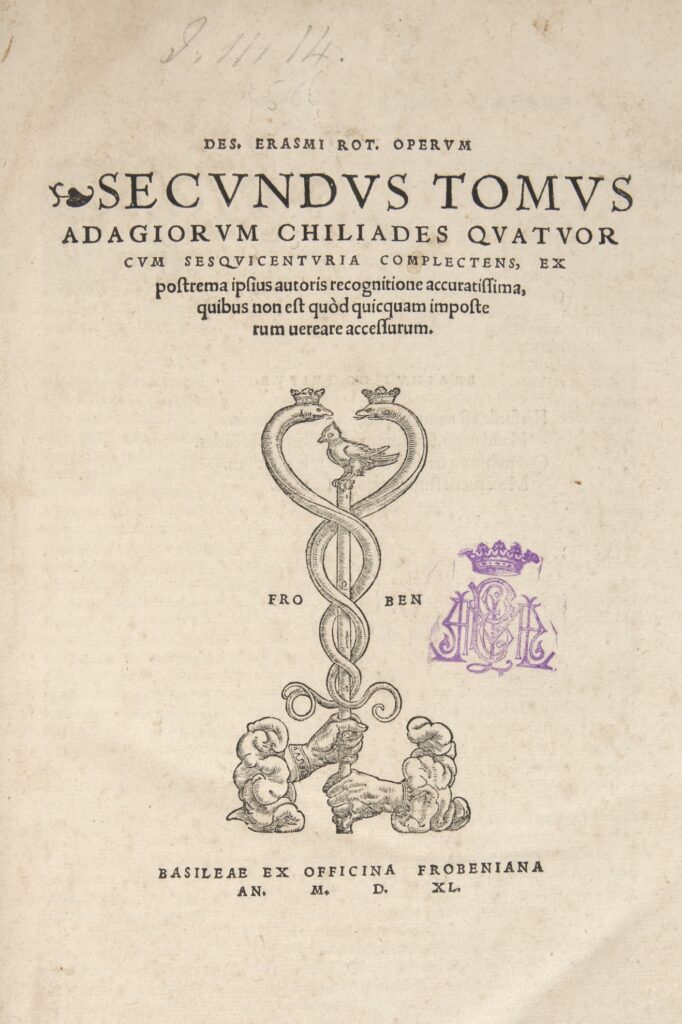

The Christian humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam was a writer whose works became widely influential during the early sixteenth century, only to be later targeted by the Inquisition. Critic Carroll B. Johnson explains, “Erasmus believed that the essence of Christianity is contained in the sacred texts, the Bible and the writings of the fathers, and not in the accumulation of traditional teachings and practices.” Erasmus insisted on the importance of inner devotion, rather than public rituals or displays of faith. In Spain, his ideas attracted many New Christians and intellectuals who modeled their spirituality after his teachings and sought to draw the Catholic Church closer in line with his views. By the middle of the sixteenth century, when Cervantes was born, the Inquisition had censored Erasmus’ work, finding it dangerously critical of the Church and close to Protestant heresy. However, Erasmus’ work remained influential and continued to circulate in secret. Johnson cites evidence that Cervantes was deeply familiar with Erasmus’ thought.

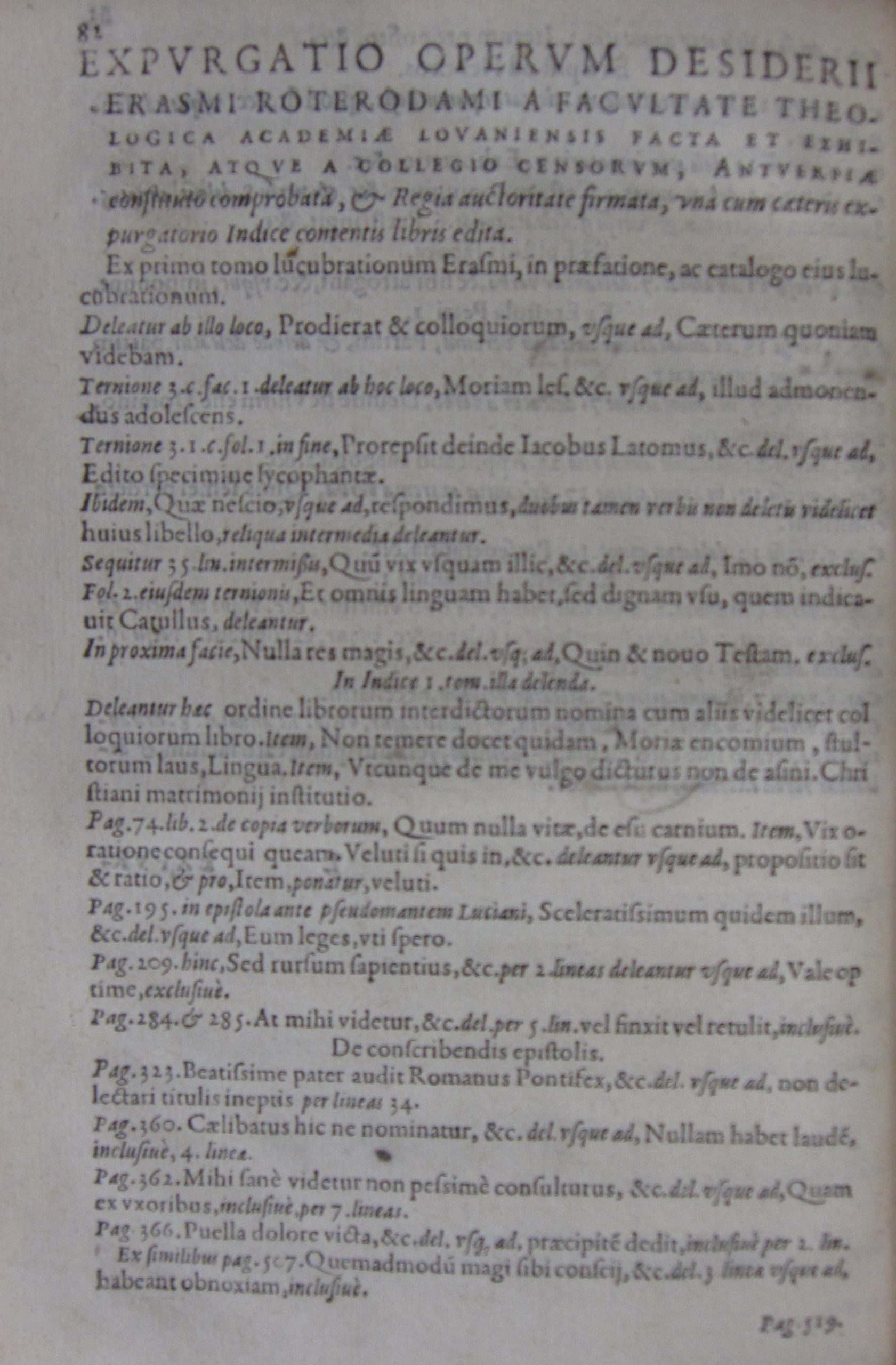

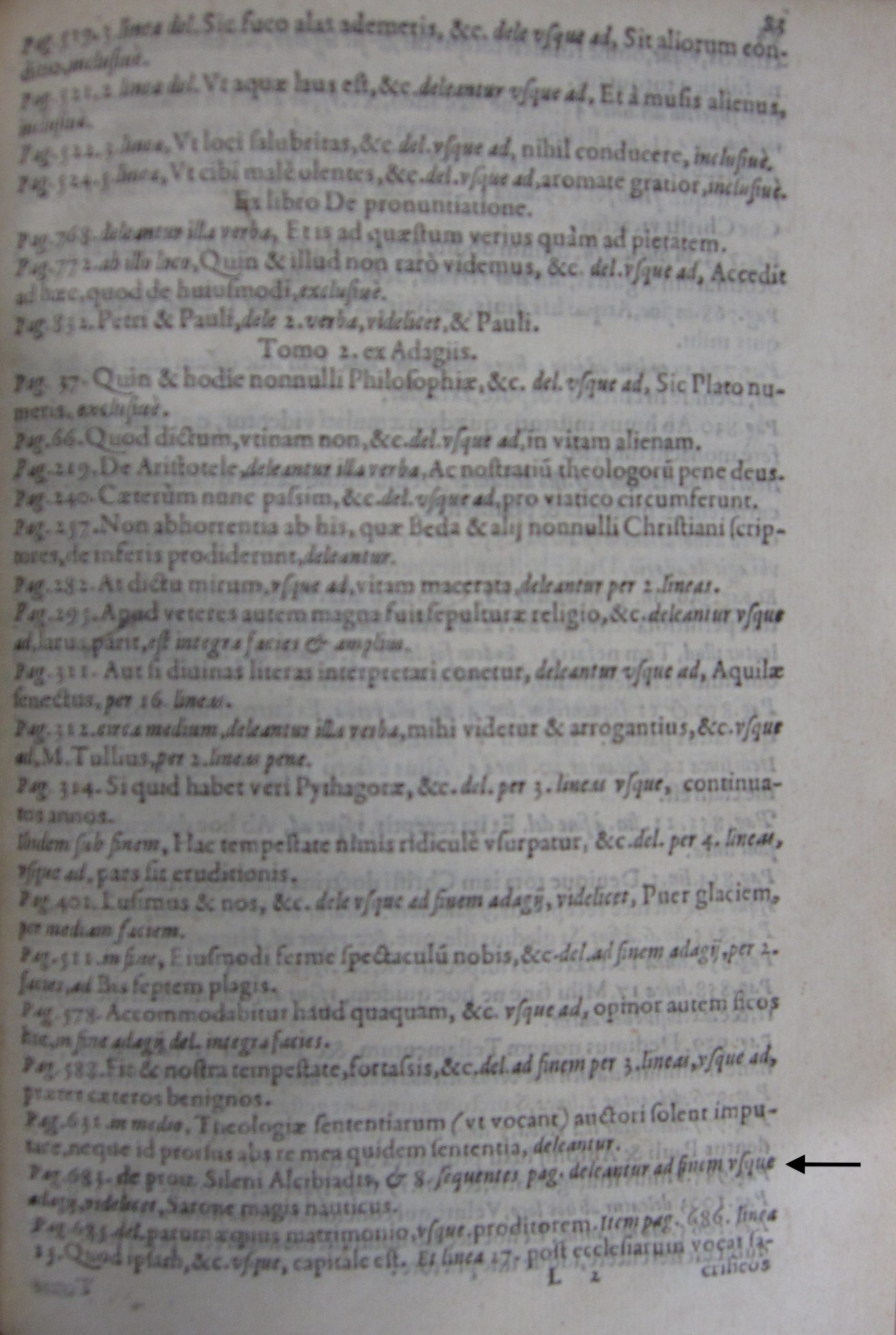

Erasmus, Adages [Sileni Alcibiades]

These documents offer some context for and insight into Cervantes’ representations of both Catholicism and censorship in Don Quixote. The first is a passage on the Sileni of Alcibaides from one of Erasmus’ most popular works, the Adages. Erasmus discusses a scene in Plato’s Symposium in which Alcibiades defends the philosopher Socrates by comparing him to a popular wooden nesting doll. The outer doll represented Silenus, a clownish flute player and companion to Dionysus, the god of wine. The inner doll was a beautiful carving of a god. Alcibiades suggests that Socrates resembles these dolls: ugly and unimpressive on the surface, but great and wise within. Erasmus first explores this idea through figures from ancient Greece, then asks “And what of Christ? Was not he, too, a marvelous Silenus?” When he turns to Christ, the censor’s pen gets busy, carefully crossing out each line for nearly two pages. The censor then cut out the remaining six pages of the entry. The section stands in sharp contrast to the rest of the book, which the censor left almost completely untouched.

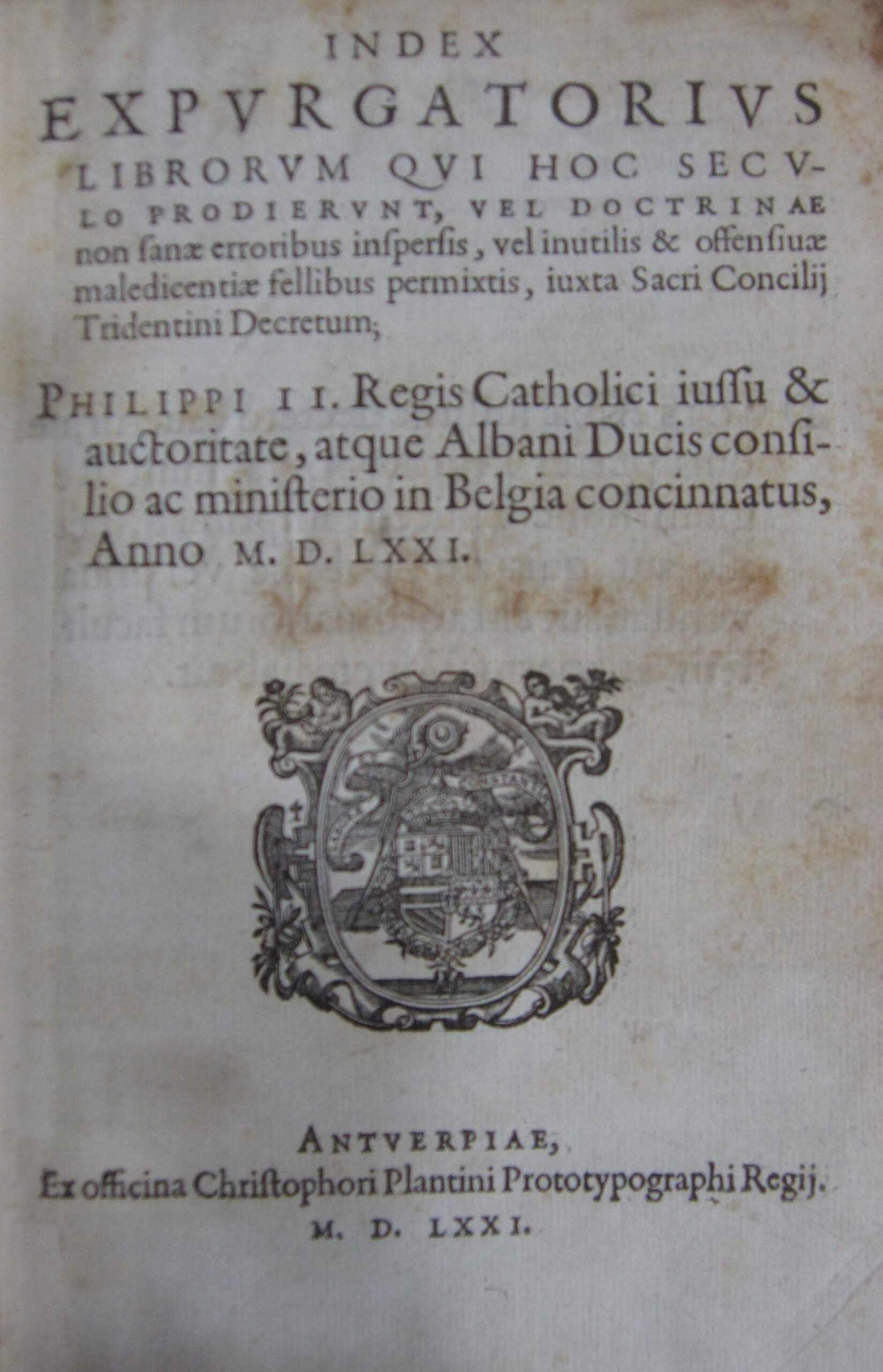

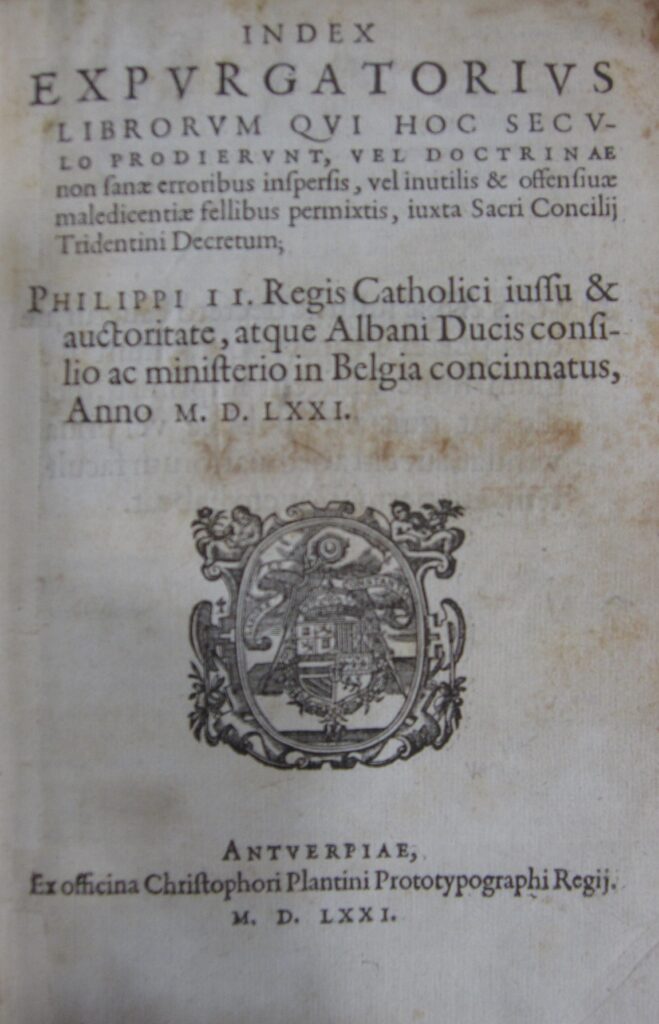

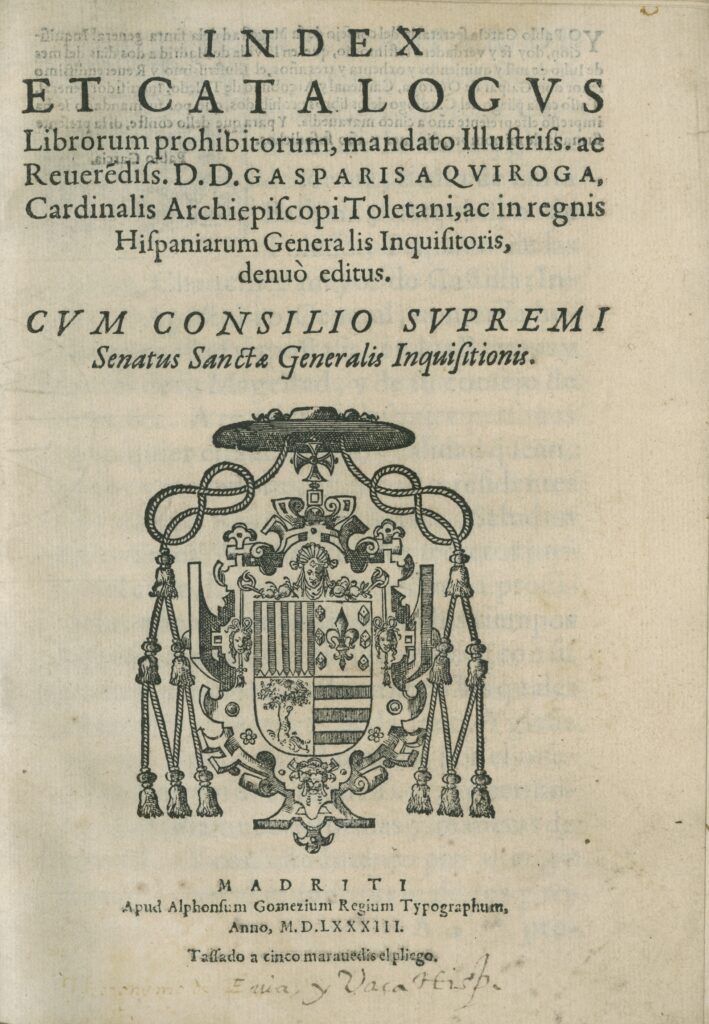

The second and third documents are excerpts from indexes of forbidden books. The 1571 Index was printed in Antwerp by order of Philip II of Spain and the Netherlands (ruled by Spain at the time). It includes a special section devoted to the works of Erasmus and probably provided the guidelines for the censor’s work on this copy of Erasmus’s Adages. The 1583 Index, published in Madrid, includes a rule prohibiting anyone who does not have the Inquisition’s approval from removing, tearing, crossing out, or burning books that contain errors.

Index of Expurgated Books

Index et Catalogus

The final document below is the frontispiece of the 1780 Madrid edition of Don Quixote, featuring an image of book burning. By this time, the Inquisition was in decline, challenged more and more openly within Spain and widely ridiculed abroad. It would not be finally abolished until 1834. It’s worth noting that Don Quixote itself passed through the Inquisition censors largely unscathed with only a few lines removed.

Questions to Consider

- In what ways does Christ resemble a Silenus figure, according to Erasmus? Why might the Inquisition have seen this passage as heretical or in some way critical of the Catholic Church? Why do you think the censor went to such lengths to preserve the two lines at the top of page 683 and to black out the passages that follow?

- What is the role of adages in Don Quixote? How might, for example, Sancho Panza’s use of adages respond to or play with the popularity and influence of Erasmus’s work?

- Why do you think the Inquisition issued a rule prohibiting people from censoring or burning books on their own, without official direction? Do Don Quixote’s friends violate this rule when they perform an inquisition of his library in Volume 1, Chapter 6? How do they decide which books to save and which to burn?

- Does Cervantes parody the Inquisition in Don Quixote? Provide evidence from the text to support your answer. If it is a parody, why do you think the censors did not object to it?

- Based on these excerpts from the altered copy of Erasmus and the two indexes, how would you characterize the methods of the Inquisition’s censors? What do you think they hoped to accomplish with their efforts? Do you think censorship was an effective way for the Spanish state to exercise power?

- Examine the frontispiece of the 1780 Madrid Don Quixote. How do you interpret the figures that appear alongside Quixote—the lion, the woman, and the cherub? What is the significance of the figure who conducts the book burning? What does this frontispiece suggest about the novel’s meaning to readers in late-eighteenth-century Spain, 175 years after its original publication?

Maps

Engravings

Texts

Further Reading

de Aramas Wilson, Diana. “Editor’s Introduction.” In Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quijote. New York: Norton, 1999. pp. ix-x.

Carr, Matthew. Blood and Faith: The Purging of Muslim Spain. New York: New Press, 2009.

Encyclopædia Britannica Online. “Spain” and “Morisco.” http://www.britannica.com.

Johnson, Carroll B. Don Quixote: The Quest for Modern Fiction. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, 1990. pp. 2, 4, 5, 10, 43, and 75.

Skelton, R. A. “Bibliographical Note.” In John Speed, A Prospect of the Most Famous Parts of the World, London 1627. Amsterdam: Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, 1966.

Wardropper, Bruce W. “Don Quixote: Story or History?” Modern Philology 63, 1 (August 1965): 1–11.