Introduction

The history of civil rights in the twentieth-century United States is inseparable from the history of the Great Migration. From the end of World War I through the 1970s, extraordinary numbers of African Americans chose to leave the South with its pervasive system of legalized racism and move to cities in the North and West. While we often associate the Great Migration with the decades around the two World Wars, historians have recently established that many more people moved away from the South after 1940 than before. Between 1940 and 1980, five million African Americans moved to the urban North and West, more than twice the number associated with the first wave of migration from 1915 to 1940. In 1930 Chicago had 198,061 southern-born black residents, which made up 72.7 percent of the city’s African American population. By 1980 it had 532,861 southern-born black residents, which was 34 percent of Chicago’s African American populace.

Drawn north by employment opportunities and the desire to escape de jure segregation in the south, African Americans found economic improvement and freedoms amid different kinds of racism and segregation.

The history of African Americans in northern cities during the twentieth century is in some ways a story of de facto segregation, that is, a separation of the races based on custom rather than law. As Arnold Hirsch pointed out more than 30 years ago in his groundbreaking history of race and housing in mid-century Chicago, Making the Second Ghetto, Martin Luther King Jr.’s greatest triumphs came in the South where de jure (or legal) segregation “was an obvious, if not always easy, target to shoot at. The immediate aftermath of his premature death, however, was punctuated by a wave of race riots in Northern cities that left Americans groping for explanations and reminded them . . . of the great social and economic problems left untouched by Jim Crow’s demise.” As Hirsch has shown in his analysis of public policy and race relations in Chicago, urban whites constructed stringent segregationist housing policies that circumscribed African Americans into new urban ghettos during and immediately after World War II.

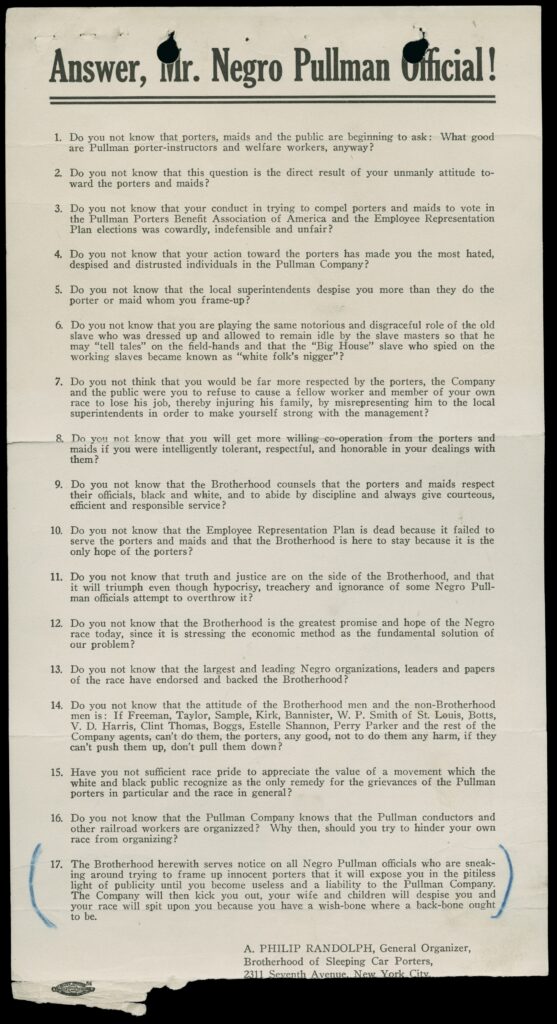

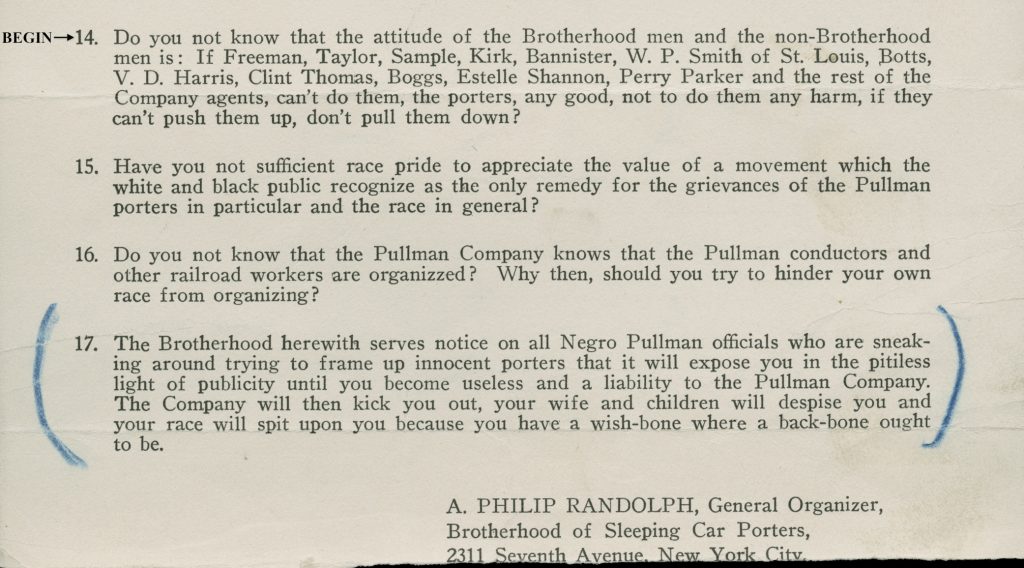

Randolph, Answer, Mr. Negro Pullman Official!

Drawn north by employment opportunities and the desire to escape de jure segregation in the south, African Americans found economic improvement and freedoms amid different kinds of racism and segregation. In addition to housing, African Americans sought fair treatment and full participation in civic life through organizing for better wages and treatment in the workplace, public school desegregation, and civil rights reform. Like de jure segregation, which required changes in law to dismantle, de facto segregation often required legal actions—in the form of law suits—to destabilize and diminish, if not completely destroy, it.

The following documents explore relationships between the Great Migration and the civil rights struggle in northern cities and, especially, Chicago from the 1920s through the 1960s. For additional sources, see Chicago and the Great Migration, 1915–1950.

Essential Questions

- What does de facto segregation in the urban North look like? How is it similar and different from de jure segregation in the South?

- How did African Americans respond to the segregation and racism they faced in the North?

- How did the civil rights movement in the urban North connect to the movement in the South?

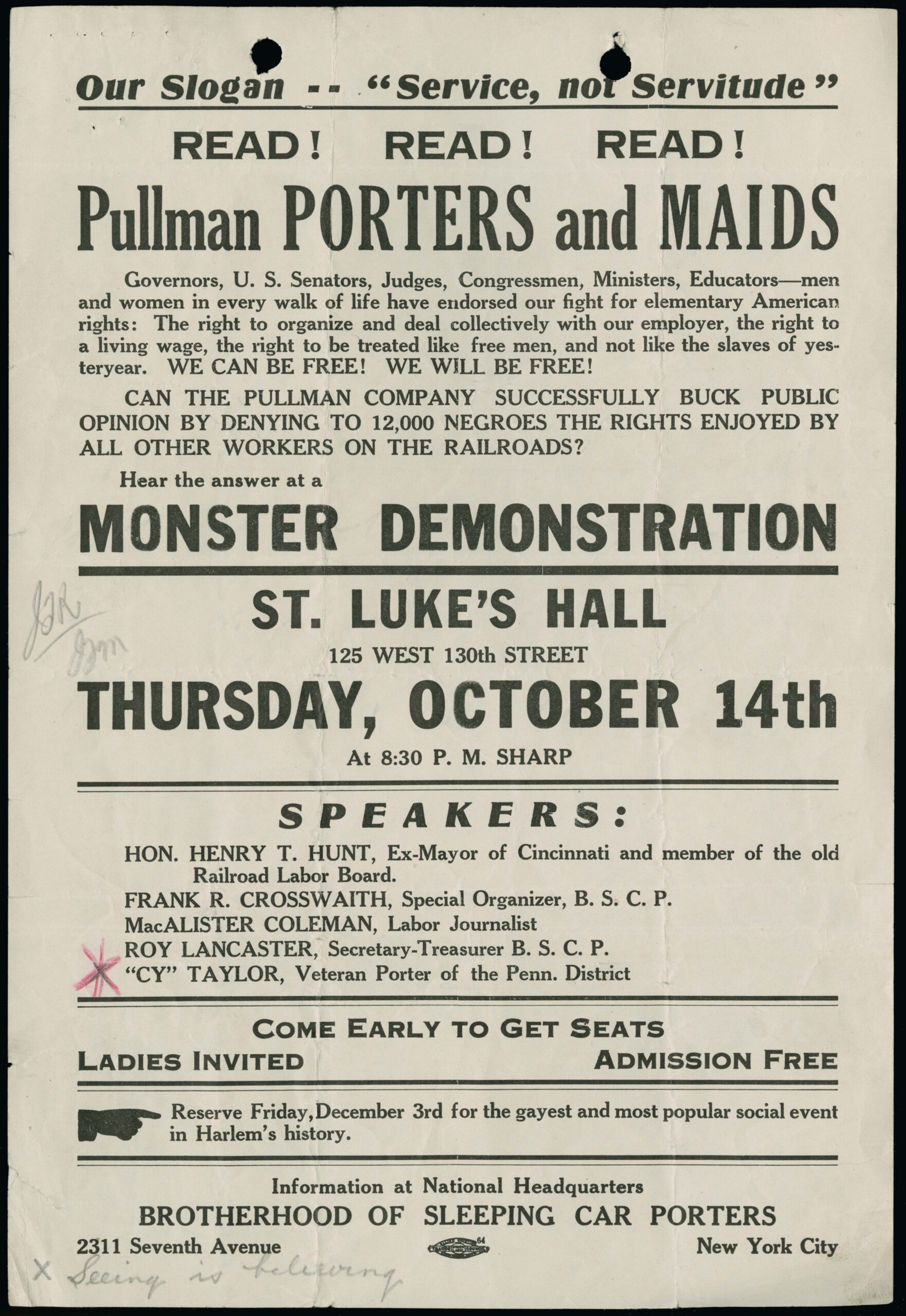

The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

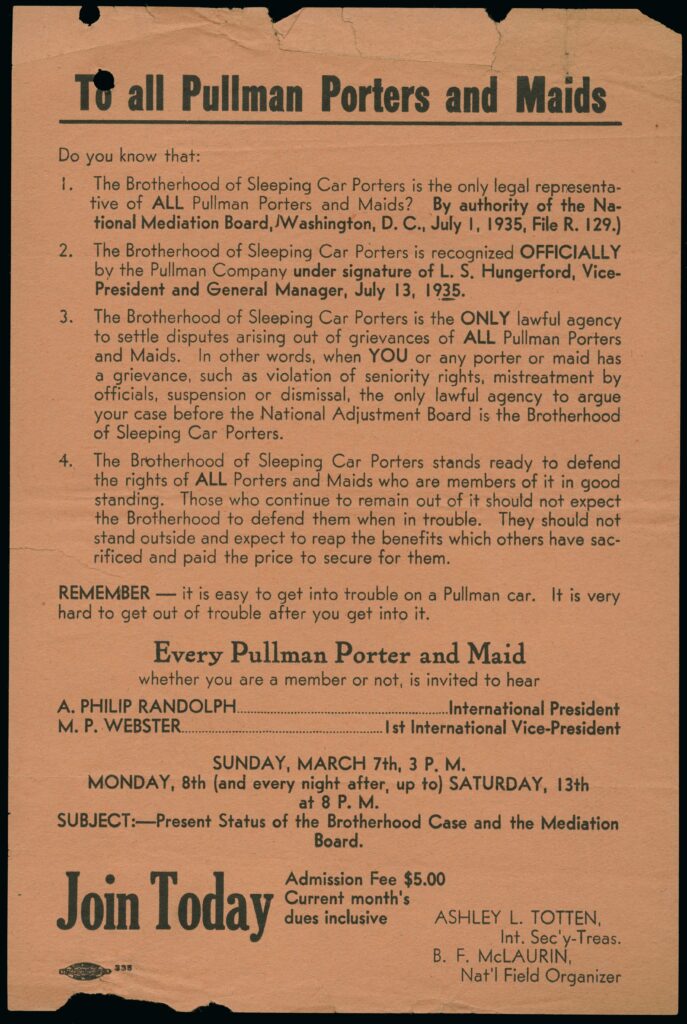

The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), the first African American labor union in the United States, was established by A. Philip Randolph in August 1925 in New York City. The BSCP organized to improve the working conditions and earnings of porters and maids on Pullman Company railroad cars. George Pullman opened the Pullman Palace Car Company in 1867 to build railroad passenger cars that offered not only comfortable but luxurious long-distance travel. He took advantage of newly freed slaves and hired only African American men from southern states as porters on his passenger cars. During its early years the Pullman Company paid porters no wages and their only earnings were tips. Pay remained the main grievance between porters and the company. The BSCP’s publication, The Messenger, reported in 1926 that a porter’s base pay was only $810 a year when the U.S. government estimated that an average American family required an annual income of $2,088 to maintain an adequate standard of living. Tips, which averaged $600 annually, did not make up the difference. Maids earned an even lower base pay with fewer chances to gain tips.

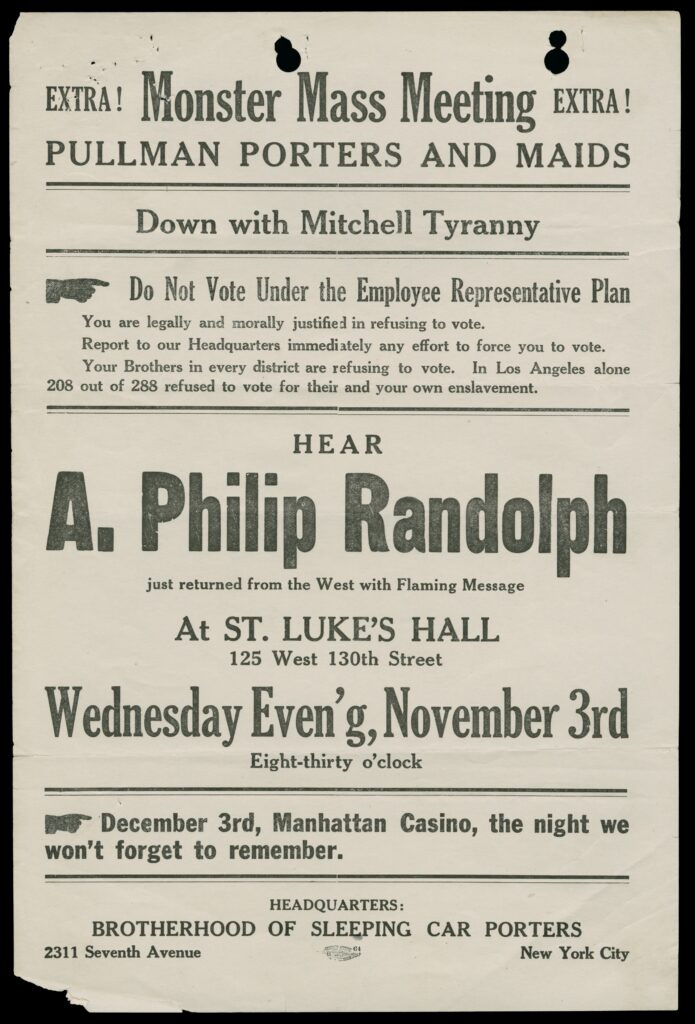

During the first decades of the twentieth century, organized labor in the United States generally refused to admit African American workers or to organize them. When Pullman porters and maids established the Pullman Porters and Maids Protective Association in 1920, the Pullman Company responded with the Employee Representation Plan (ERP), a company union. Strategically, Pullman company leaders included African American representation on the ERP’s board at the same time that they created a climate of intimidation toward BSCP members by encouraging employee informants among porters and maids.

Randolph and his fellow organizers struggled to establish the BSCP on three fronts: to convince porters and maids that their interests lay with the BSCP and not their employer’s union; to gain recognition and bargaining status with the Pullman Company; and to secure a charter from the American Federation of Labor (AFL). As these flyers show, in 1926 the BSCP waged a campaign among porters and maids to not endorse the ERP, and against the company’s divide-and-conquer tactics among its African American workers. Despite vigorous campaigning, the BSCP could not contend against the power of the company. Amid BSCP allegations of intimidation, Pullman officials claimed that 85 percent of porters and maids voted in support of the company plan.

The BSCP appealed to the Mediation Board, the government body charged with managing labor disputes as part of the 1926 Railway Labor Act. The BSCP hoped the Board would recognize the Brotherhood as the representative body for porters and maids over the ERP. Randolph and his BSCP organizers broke through the impasse only in 1934 with passage of New Deal legislation that invalidated company unions. The following year the BSCP gained recognition from both the Pullman Company and the AFL.

The BSCP was a vanguard organization within the African American community, whose cultural and historical significance outweighed its size. At the height of the BSCP’s power, in the late 1930s, its membership rolls only included about 6500 workers. A. Philip Randolph and his colleagues waged campaigns for African American rights in general, beyond bread and butter labor questions. In 1941 Randolph organized the March on Washington Movement to protest racist hiring practices in defense industries. This initiative was the first modern example of a direct-action organization with a mass membership, which foreshadowed the civil rights actions in the 1950s and 1960s. Randolph also, with Bayard Rustin, organized the 1963 March on Washington.

For additional sources related to the BSCP, see Subversives in the City.

Questions to Consider

- Who is the audience or audiences for The Pullman Porter? What questions or assumptions was the pamphlet trying to address, and from whom?

- The tipping system is carefully explained in The Pullman Porter. Why? What “evils” did it represent to the BSCP and Pullman porters and maids?

- Who does the BSCP address in the flyer, Answer, Mr. Negro Pullman Official!? How does this flyer approach class differences among African Americans?

- Do BSCP flyers for meetings convey a reform agenda beyond union organizing? If so, how?

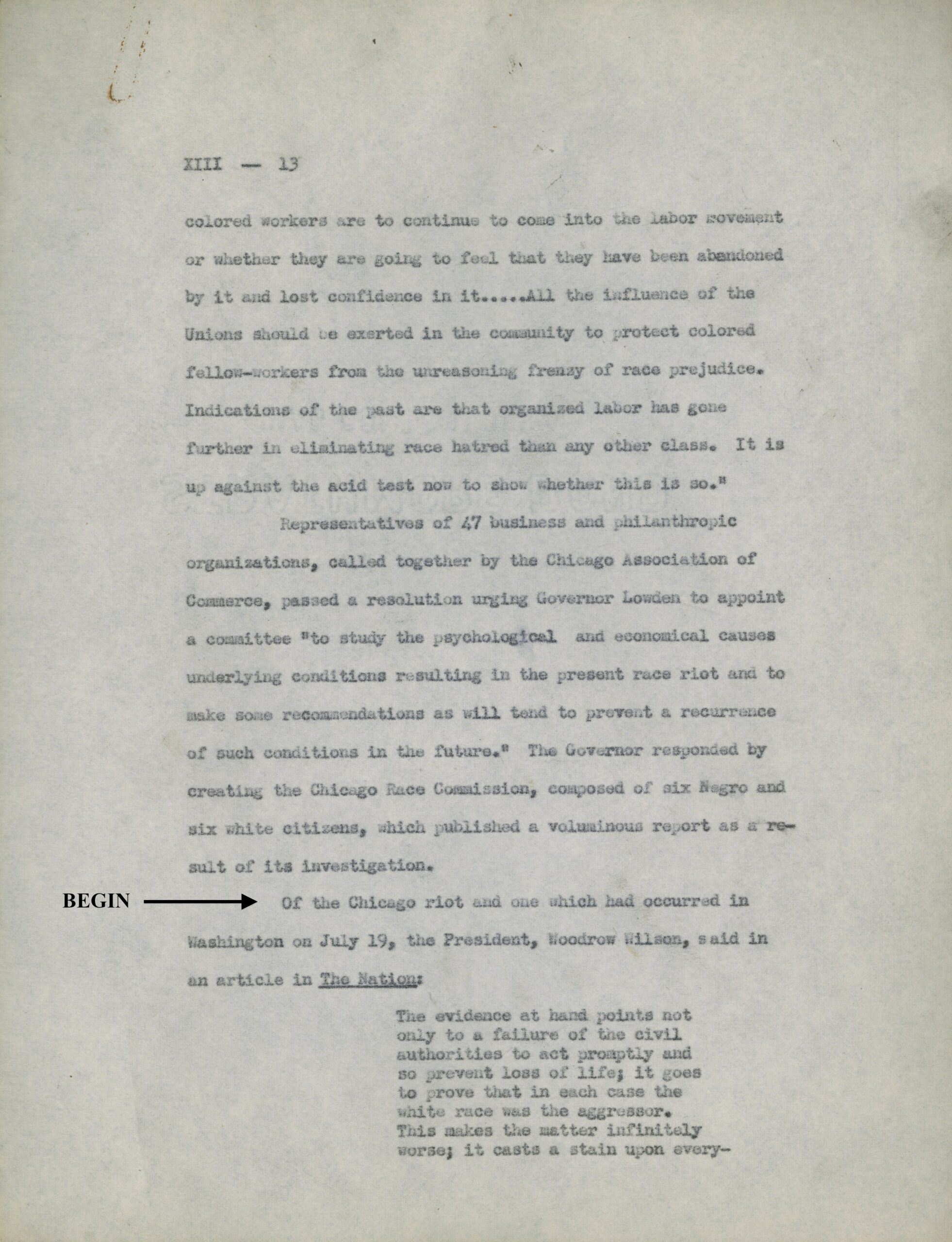

They Seek a City

During the middle of the Great Depression two writers in the Illinois Writers’ Project, an initiative of the New Deal’s Work Projects Administration, were given an assignment: gather material for a book on the history of African Americans in Illinois. Arna Bontemps, a distinguished poet and novelist of the Harlem Renaissance, and Jack Conroy, the best-known proletarian writer of his generation, researched and wrote a history of the Great Migration. It was published in 1945 as They Seek a City, then expanded and republished in 1966 as Anywhere But Here.

Bontemps and Conroy brought different but complementary perspectives to the book. At the age of three Bontemps migrated with his family from Louisiana to Los Angeles, California. The son of a bricklayer and a schoolteacher, Bontemps graduated from college and quickly moved to New York, where the Harlem Renaissance drew the aspiring poet and writer. Bontemps’ poetry and a short story found early critical acclaim in the 1920s; several novels a few years later, including God Sends Sunday and Black Thunder, achieved mixed reviews. Frustrated by the difficulty of supporting his growing family on meager book royalties and the lack of critical attention paid to African American writers, Bontemps earned a degree in librarianship and turned to a new profession by the mid-1940s. He also began writing children and young adult fiction and history in the 1940s and 1950s; the most notable was his 1948 The Story of the Negro, which won the 1956 Jane Addams Children’s Book Award.

Conroy was born in Monkey Nest, a coal mining camp near Moberly, Missouri, and during the 1920s was a migratory worker. Conroy established his literary reputation with publication of an autobiographical novel, The Disinherited, in 1933. That same year he launched a literary magazine, The Anvil. Conroy proved adept at identifying new writing talent and he also welcomed work by African American and women writers, including Langston Hughes and Meridel Le Seuer. The Anvil’s slogan, “We prefer crude vigor to polished banality,” indicated Conroy’s editorial policy, which was to foster literary creativity by working people—a new proletarian literature.

Bontemps and Conroy teamed up in the folklore section of the Illinois Writers’ Project for an ambitious project: a history of African Americans in the state from the beginnings of slavery to emancipation and the Great Migration, with separate chapters on aspects of African American life, culture, and politics. Bontemps and Conroy hired major black writers living in Chicago at the time to work on the project, including Richard Wright, Margaret Walker, Katherine Dunham, Fenton Johnson, Frank Yerby, and Richard Durham. When the U.S. entered World War II, funding for Writers’ Projects books ended and the manuscript was left uncompleted. Bontemps and Conroy, however, reworked it and published a limited history, focused on the Great Migration with additional material documenting African American participation in the history of American exploration and settlement.

Bontemps and Conroy, Jordan’s Stormy Bank, 13-17

Questions to Consider

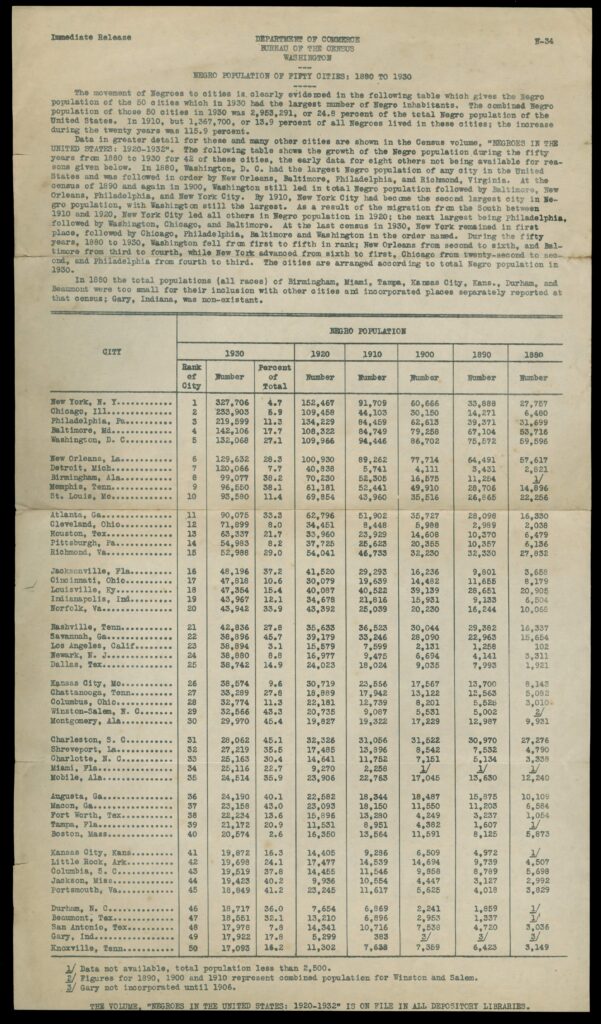

- The Bureau of the Census table shows African American populations of fifty cities from 1880 to 1930. The description above the table notes that in 1880 only one northern city, Philadelphia, made the top five most populous African American cities. By 1930, that ratio had nearly reversed, with only two southern cities still in the top five: Baltimore and Washington DC. What does the census table reveal about how African American migration changed over the 20-year period from 1910 to 1930?

- What kinds of de facto segregation did African Americans encounter in Chicago, according to this excerpt from the chapter, “Jordan’s Stormy Banks”?

- When They Seek a City was published in 1945 it received good reviews, being especially noted for its even tone and factual delivery. Do you think the book’s tone has held up after more than sixty years? How would you characterize the authors’ voice?

Blockbusting

In Chicago, starting in the late nineteenth century, African Americans were restricted to living in a narrow corridor of land between 22nd Street and 31st Street and from the Illinois Central railroad tracks to State Street. With the First Great Migration, this area widened slightly and expanded south. In the 1920s white property owners began using racially restrictive covenants in areas adjacent to the Black Belt. These were contractual agreements among owners not to sell, lease, or allow occupation by members of a group of people, usually African Americans.

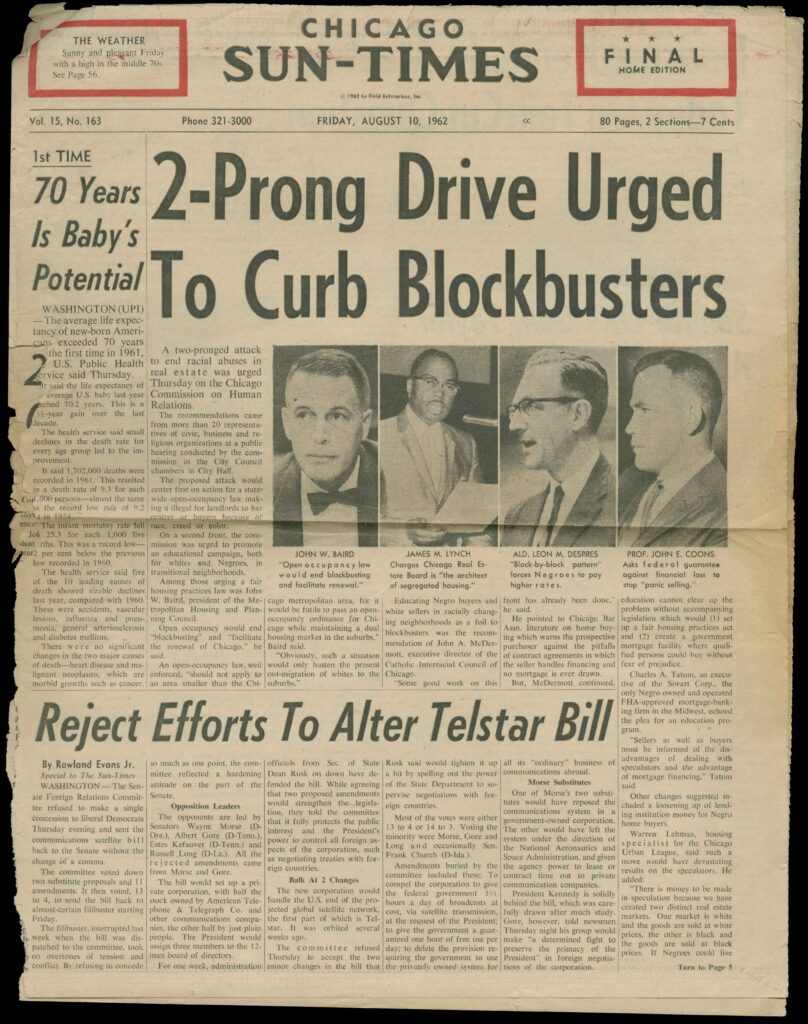

Chicago Sun-Times, 2-Prong Drive Urged to Curb Blockbusters

Blockbusting was the work of real estate agents and speculators to hasten or trigger the transition of white-owned residential property to African Americans. Sometimes called panic peddling, these methods often coincided with the expansion of African American residential areas and the entry of African Americans into neighborhoods from which they had previously been excluded. Speculators would frighten white home owners into selling below market value then turn around and sell the property for double or triple what they had paid to African American buyers. The explosion of African American migration during and after World War II led to an intense period of blockbusting as African Americans desperately needed housing and a growing middle class had the means to escape the poorest sections of the old urban core.

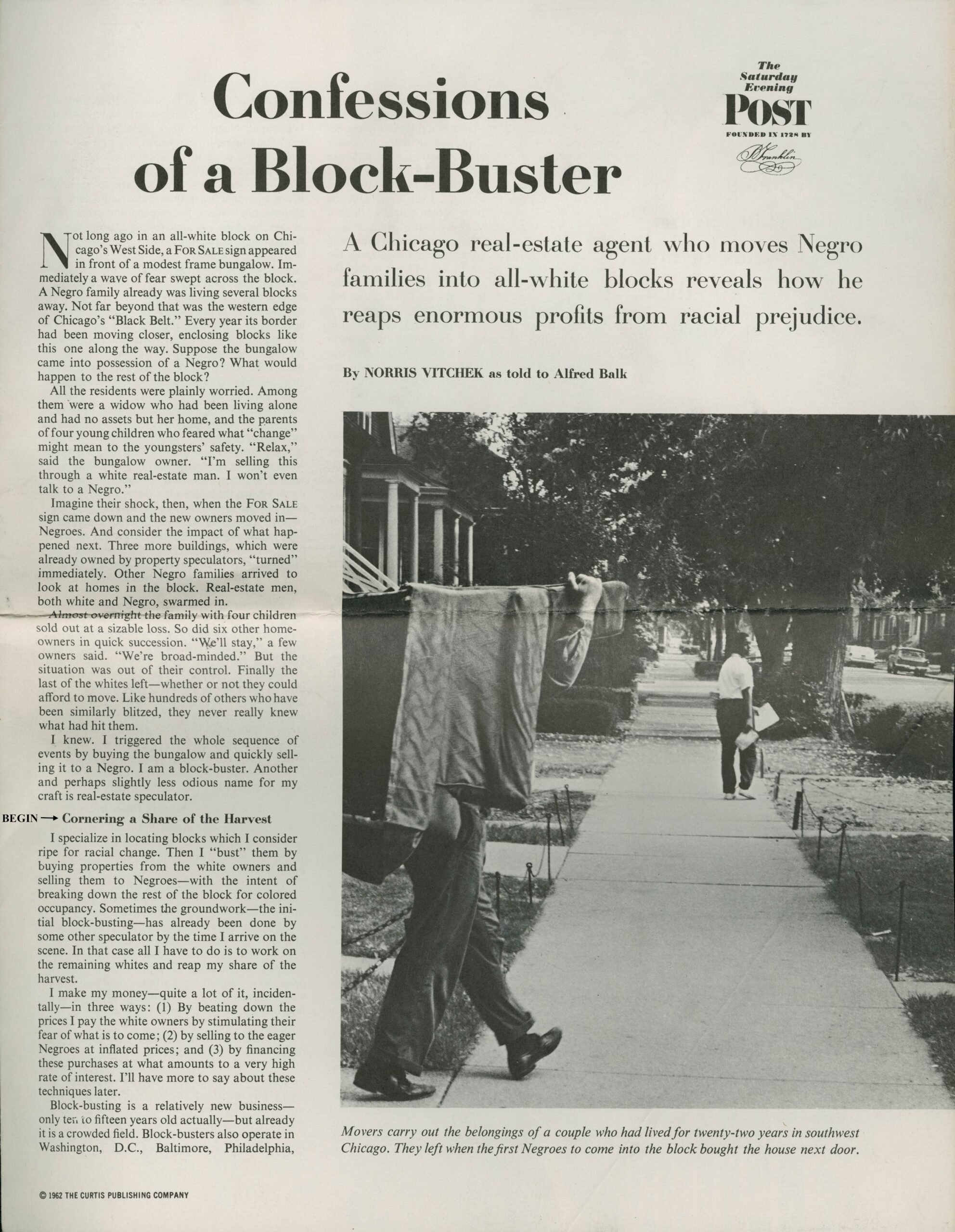

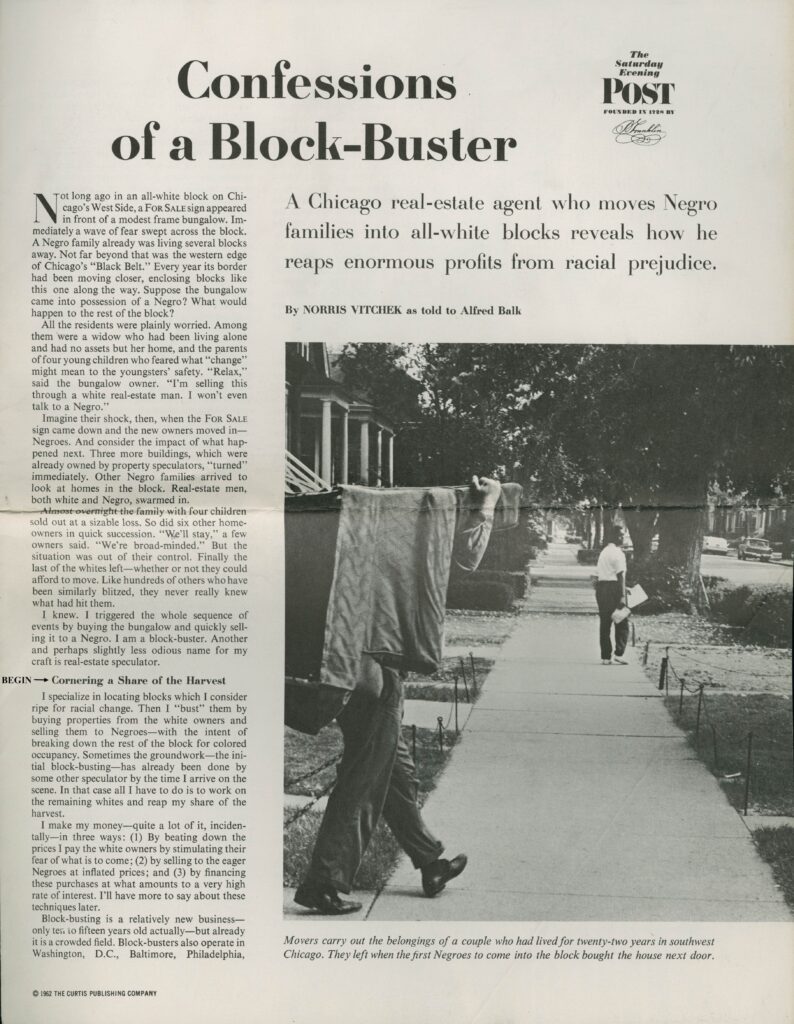

In July 1962 Alfred Balk, a freelance reporter in Chicago, published an exposé on the practice of blockbusting in the national weekly magazine, The Saturday Evening Post. Balk wrote the piece from the perspective of his source, Norris Vitchek, a pen name Balk used to protect his informant. The article sparked outrage; some thought Balk deliberately provoked racial tensions, and others gleefully pointed to the article’s exposure of northern white racial hypocrisy. In Chicago, Balk’s article prompted debate about fair housing practices. The journalist’s later refusal to identify the source for his article led to a landmark Federal District Court decision that protected journalists’ confidentiality, a decision the Supreme Court let stand in 1972.

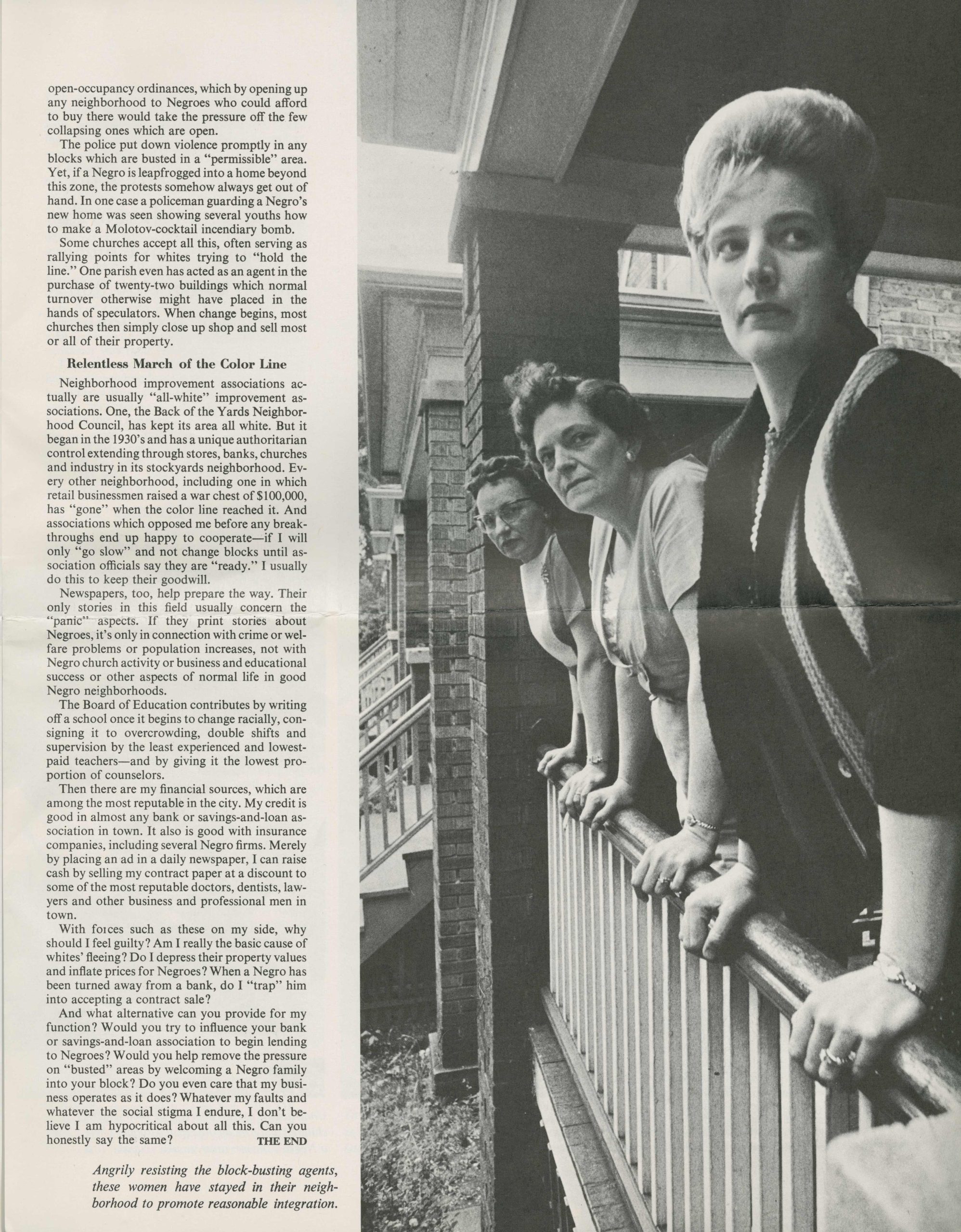

Vitchek, Confessions of a Block-Buster, 1-5

Questions to Consider

- In Balk’s article, “Confessions of a Block-Buster,” how did real estate speculators or blockbusters use race and racial stereotypes to frighten white property owners?

- What reaction do you think Balk was trying to evoke in readers?

- What were the “forces” the blockbuster identifies that were “on his side” as he broke into a neighborhood? Who was responsible for white flight and the exorbitant financing costs African Americans often accepted to purchase their new homes?

- Do you think the advertisement in the Daily News pandered to white racist fears?

- What was the “Rule of Segregation” that Alderman Leon Despres referred to in the “Attack All-White Realty Board” article? Was this an example of de facto segregation or something more organized?

- We usually assume that Jim Crow laws (de jure segregation) could only be dismantled through new legislation. But legal challenges are often required to eliminate de facto segregation as well. What did leading Chicago citizens urge the Chicago Commission on Human Relations to do to end racial abuses in real estate?

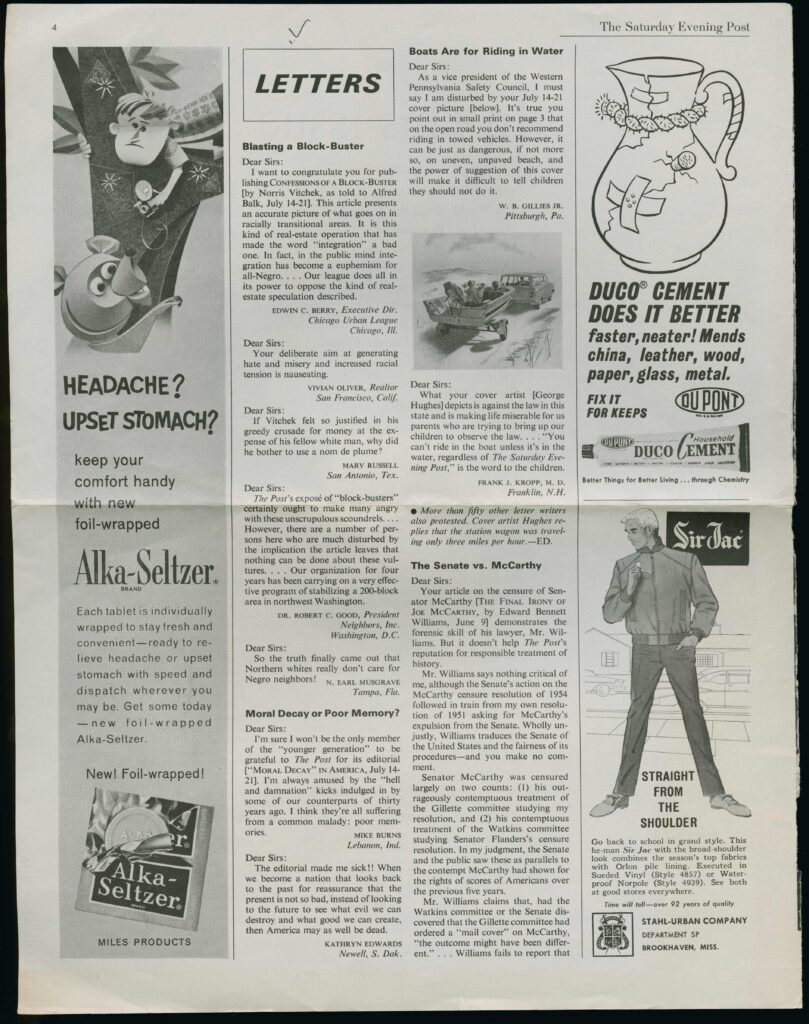

- What did Vivian Oliver mean when she wrote a letter to the editor, accusing the Saturday Evening Post of a “deliberate aim at generating hate and misery and increased racial tension”?

The March on Washington and on the Chicago Sun-Times

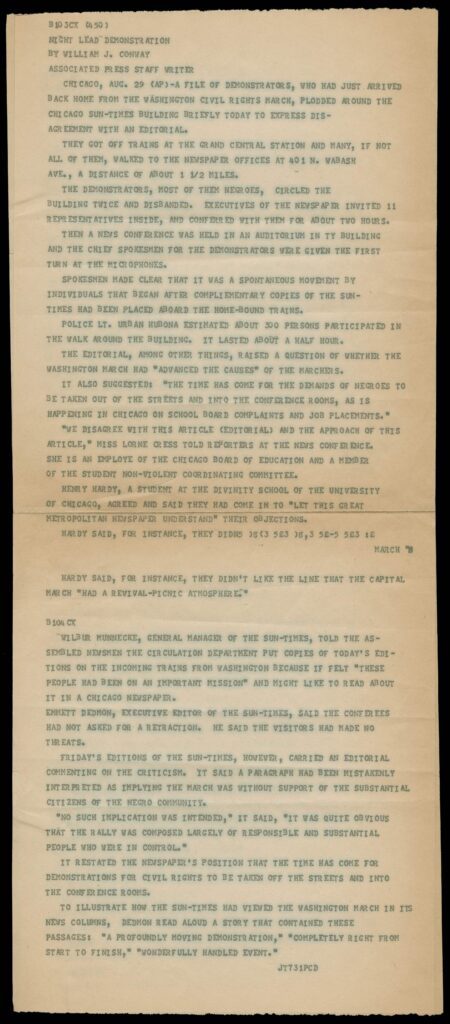

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963 brought more than 200,000 people to the National Mall to demonstrate for civil and economic rights for African Americans. Timuel Black, a 44-year-old teacher and civil rights activist, organized the Chicago contingent, about half of whom traveled to and from Washington on two “freedom trains” chartered to accommodate nearly 2,000 passengers. When Black and his fellow marchers returned to Chicago on the morning of August 29th, however, they were met with a critical Chicago Sun-Times editorial, “Now that the March is Over.”

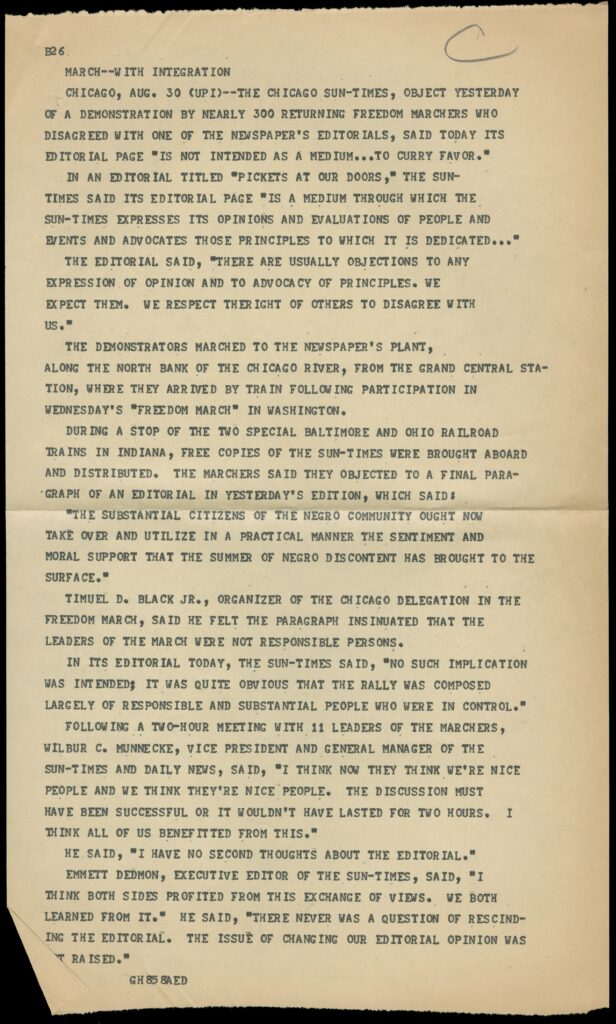

The Associated Press and United Press International, two respected news services, widely reported the Chicago paper’s editorial and its aftermath. According to them, the Sun-Times editorialized that “[t]he substantial citizens of the Negro community ought now take over and utilize in a practical manner the sentiment and moral support that the summer of Negro discontent has brought to the surface.” It also declared that “[t]he time has come for the demands of Negroes to be taken out of the streets and into the conference rooms, as is happening in Chicago on school board complaints and job placements.”

Copies of the Sun-Times were placed on the chartered trains when they made a stop in Indiana. When the marchers alighted in Chicago, between 200 and 300 walked a mile and a half from the station to the Sun-Times building on the Chicago River. They circled the building twice, some carrying signs improvised from those they had carried the day before in Washington. Demonstration leaders met with newspaper officials, including Emmett Dedmon, executive editor of the Sun-Times.

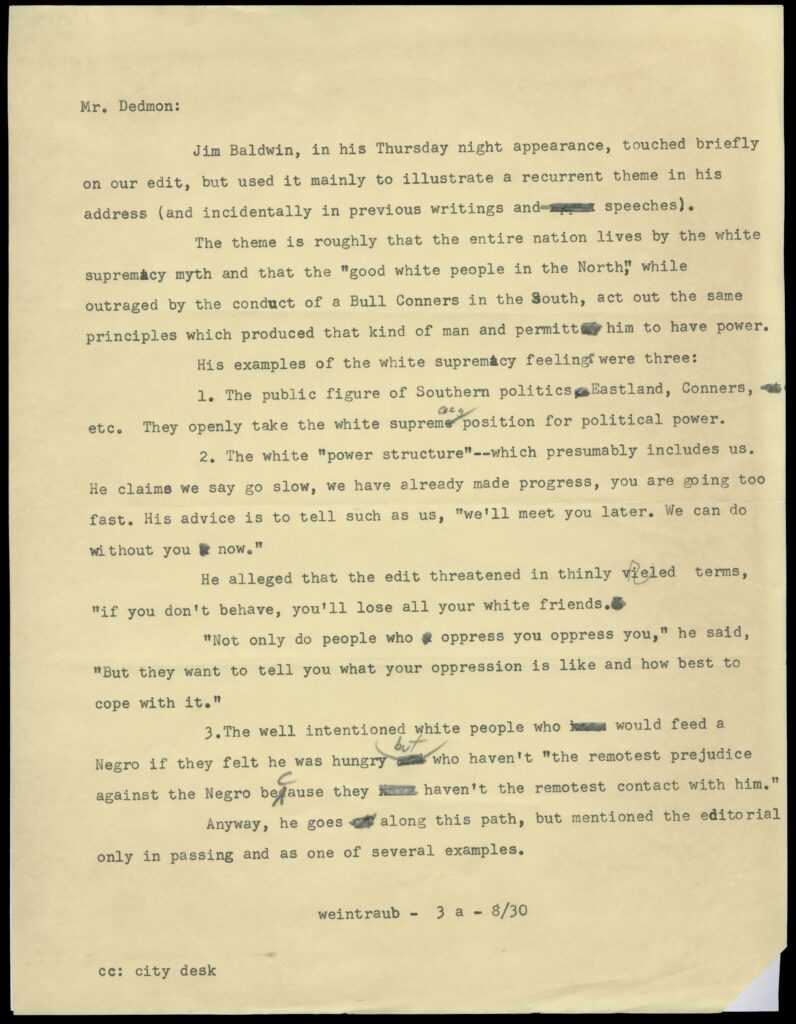

With protesters at their doors and national and international coverage turned on them, Sun-Times officials anxiously watched for further public reaction. One African American leader they paid particular attention to was writer and activist James Baldwin, who spoke at a Congress for Racial Equality event on the evening of August 29th. Sun-Times reporter Larry Weintraub described Baldwin’s remarks to Dedmon in an internal Sun-Times memo the next day, noting twice that Baldwin had mentioned the editorial only briefly.

The Sun-Times published “Pickets at Our Doors” the day after its controversial editorial, denying they had intended to imply that the march did not have the support and leadership of responsible people within the African American community.

Questions to Consider

- Lorne Cress, one of the protesters at the Sun-Times, reportedly told the press, “[w]e disagree with this article (editorial) and the approach of this article.” What did she object to?

- As Larry Weintraub described James Baldwin’s public remarks in this memo, what does the reporter reveal about his own perspective on race and civil rights?

- What is the tone of the Sun-Times officials in these reports? Do they seem prepared for or surprised by the protest? Why? Given enough public pressure, does it seem possible that the Sun-Times might have retracted the editorial? Do you think the paper should have retracted it?

Desegregating Public Schools in Chicago

The Chicago Sun-Times editorial on August 29, 1963, following the March on Washington, indicated the importance of African Americans’ taking their complaints to places of power in their communities and it mentioned in particular the Chicago School Board. The School Board had long been a sore spot for black Chicagoans. Parents and community leaders had protested segregation and unfair treatment in the city’s schools since the end of World War II, when the rapidly expanded African American population in the city required urgent attention from the Board of Education. White officials responded, however, by adjusting school district boundaries to maintain racial segregation. By 1960, when Chicago’s African American population reached over 800,000, almost a quarter of the city’s total, schools in black neighborhoods were so overcrowded that many held double shifts to accommodate students. Superintendent of Schools Benjamin Willis steadily rejected calls for desegregation, opting instead, beginning in late 1961, to install aluminum, portable classrooms at African American schools, which quickly became known, derisively, as “Willis Wagons.”

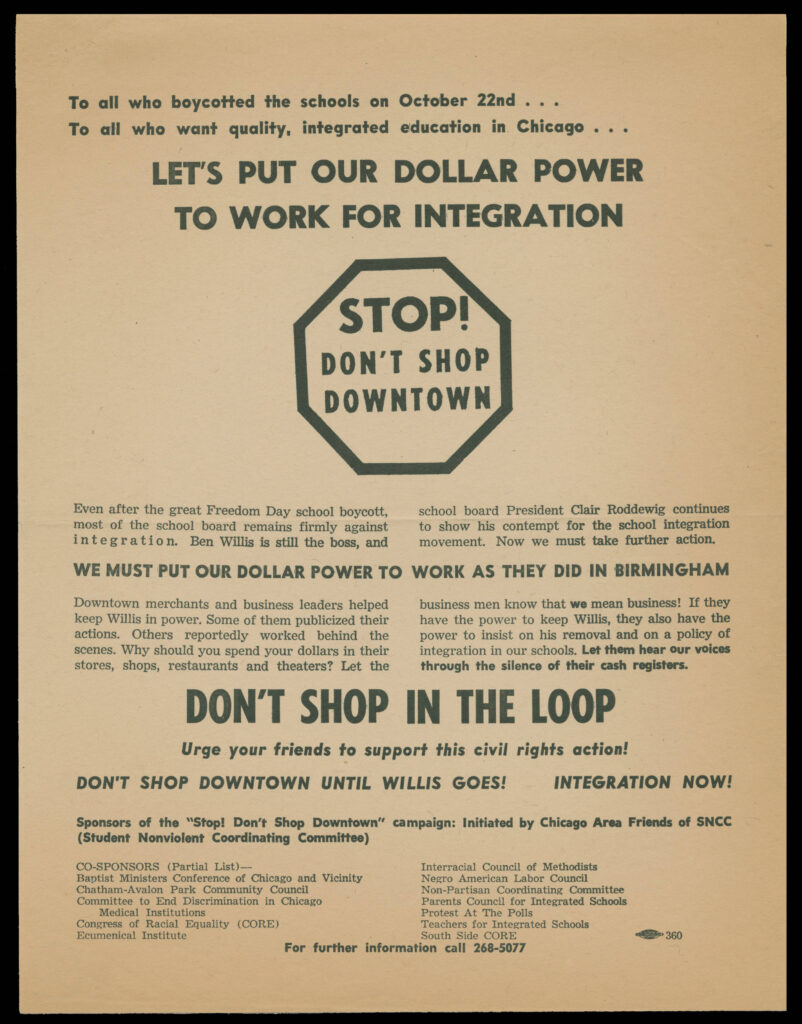

Just a few months after the March on Washington, civil rights activists, including the Chicago Area Friends of SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), the Coordinating Council of Community Organizations (CCCO), and others, created a massive school boycott to demonstrate against continued segregation and Willis’s tenure. On October 22, 1963, more than 200,000 students declared it “Freedom Day” and refused to attend school, while 10,000 people marched to Willis’s office at the Board of Education, demanding a meeting.

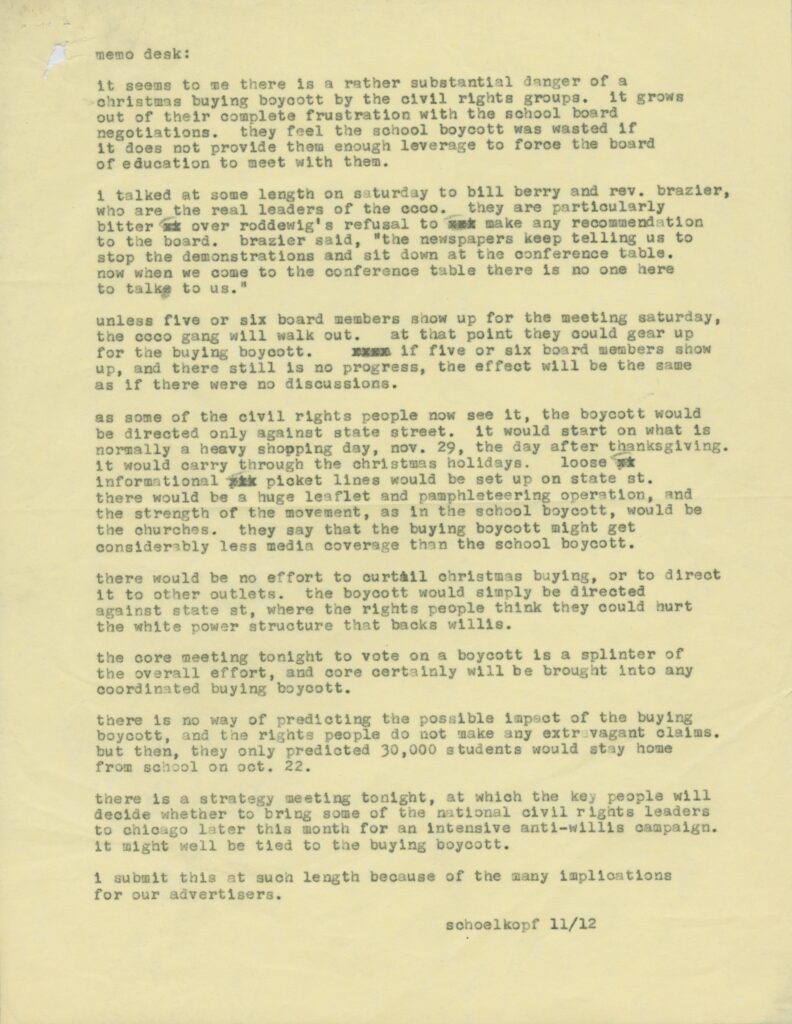

Board of Education President Claire Roddewig and Willis refused to negotiate, however, so the CCCO, led by Chicago Urban League Executive Director Bill Berry and Reverend Arthur Brazier, organized a holiday season shopping boycott. They focused the protest on downtown stores along State Street, the city’s main retail area. They hoped to put pressure on the white business establishment that supported the Board of Education and kept Willis in power.

In an internal Chicago Daily News memo on November 12, 1963, reporter Dean Schoelkopf described an interview with Berry and Brazier about the shopping boycott. The activists expressed frustration with Chicago newspapers, which “keep telling us to stop the demonstrations and sit down at the conference table.” Schoelkopf ended his memo with a statement about a boycott’s effect on the paper’s advertisers. In a separate internal memo a few days later, Larry Fanning, executive editor of the paper, fretted to his staff about the boycott, “[i]t could be serious.”

Chicago’s schools remained largely segregated, despite concerted efforts by civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr. Later efforts by the state and federal governments as well as the courts brought only slight improvements. Between 1970 and 1990 the white-student population fell by nearly 75 percent. The dramatic decrease was due in part to white flight to suburban communities and in part to a shift by whites to private and parochial schools. Today, Chicago Public Schools remains the most-segregated big-city school district in the country.

Questions to Consider

- Why did the shopping boycott organizers refer to Birmingham in their flyer? Why do you think they wanted to associate Chicago with Birmingham?

- To whom is this flyer addressed? Who are the audiences for it? Could there be more than one?

- What tensions between civil rights workers and the press appear in Schoelkopf’s memo? Does Schoelkopf seem worried about a boycott and what might happen?

Newspaper Sources

Correspondence

Fliers

Further Reading

African American Urban History Since World War II. Kenneth L. Kusmer and Joe W. Trotter, eds. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Chicago Historical Society and Newberry Library. Encyclopedia of Chicago.

William H. Harris. Keeping the Faith: A. Philip Randolph, Milton P. Webster, and the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, 1925–37. Urbana: The University of Illinois Press, 1977.

Arnold R. Hirsch. Making the Second Ghetto: Race and Housing in Chicago, 1940–1960. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

The Negro in Illinois: The WPA Papers. Brian Dolinar, ed. Urbana: The University of Illinois Press, 2013.