Introduction

In November of 1933, Franklin Roosevelt won the American presidency during one of America and the world’s gravest economic depressions. As he gazed out at hundreds of thousands of unemployed workers standing in humiliating breadlines, Roosevelt vowed to reverse unemployment and jumpstart America’s economy. To end the Depression, Roosevelt and his administration promised Americans a New Deal, and implemented programs designed to offer “relief, recovery, and reform” to the American people. Because programs and organizations began with confusing acronyms, they became known as the “alphabet soup.” For example, the CCC, CWA, and WPA created jobs, the HOLC reformed housing loans, the FSA and NRA instituted federal social security, and the NRA and the NLRB made it legal and safe for unions to organize. Within a few years, the economy improved and though critics asserted it had nothing to do with the New Deal, the president declared that his programs had single-handedly stemmed the tide of economic hardship and improved the lives of millions. In 1936, as he ran for his second term in office, Roosevelt asserted, “none of this [recovery] came by chance. It came because your Government refused to leave it to chance. It came because your Administration thought things through—thought of things as a whole—planned a balanced national economy and acted in a score of ways to bring it to pass.” Whether New Deal programs reversed the effects of the Great Depression remains up for debate, but Roosevelt’s radical new plan certainly altered the landscape of the federal government. After the 1930s, ordinary Americans began to rely on the federal state in new ways, expecting measured welfare benefits, increased regulation of banking and industry, and the promise of financial security in old age.

This collection explores several New Deal programs, highlighting how Chicago and Midwestern-based workers negotiated new welfare reforms. It provides a snapshot of how new agencies reshuffled family relations, mobilized immigrants, and sometimes reached across racial barriers. With a particular focus on labor and employment, these documents represent a broad range of responses to President Roosevelt’s policies, demonstrating the praise and protest elicited as policymakers established a growing welfare state.

Essential Questions:

- Who benefited from New Deal labor reforms?

- What effect did new social programs have on Chicagoans across class, racial, and ethnic divides?

- How did the politics of the New Deal change ordinary Americans’ relationship to the federal government?

Emergency Relief

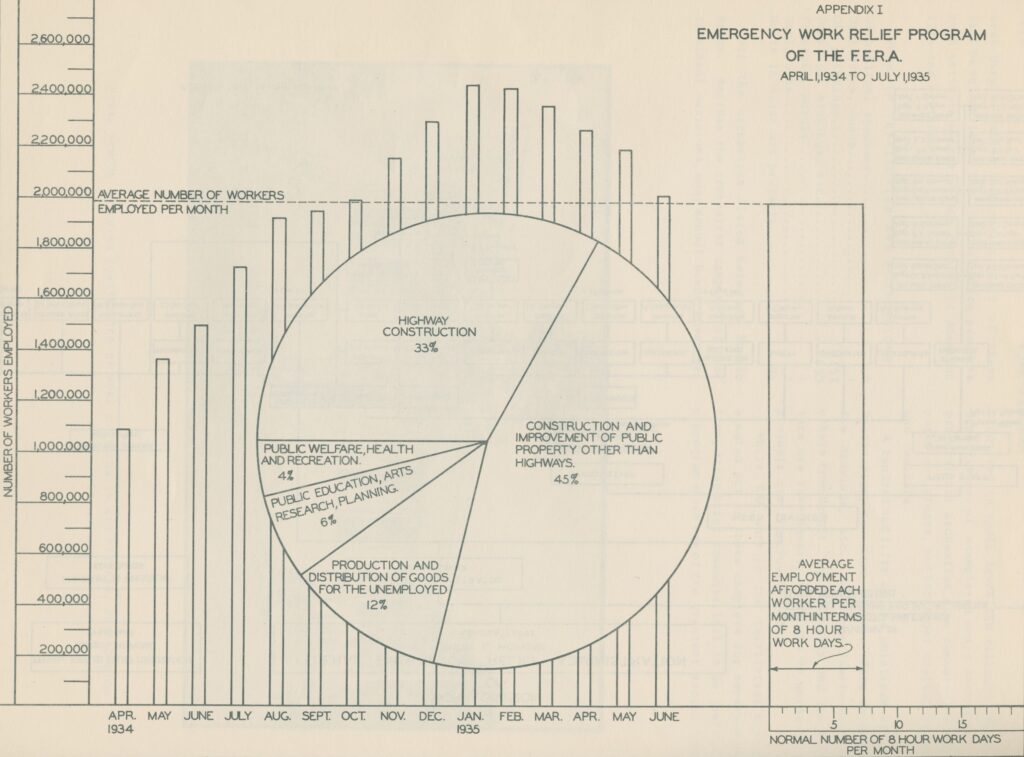

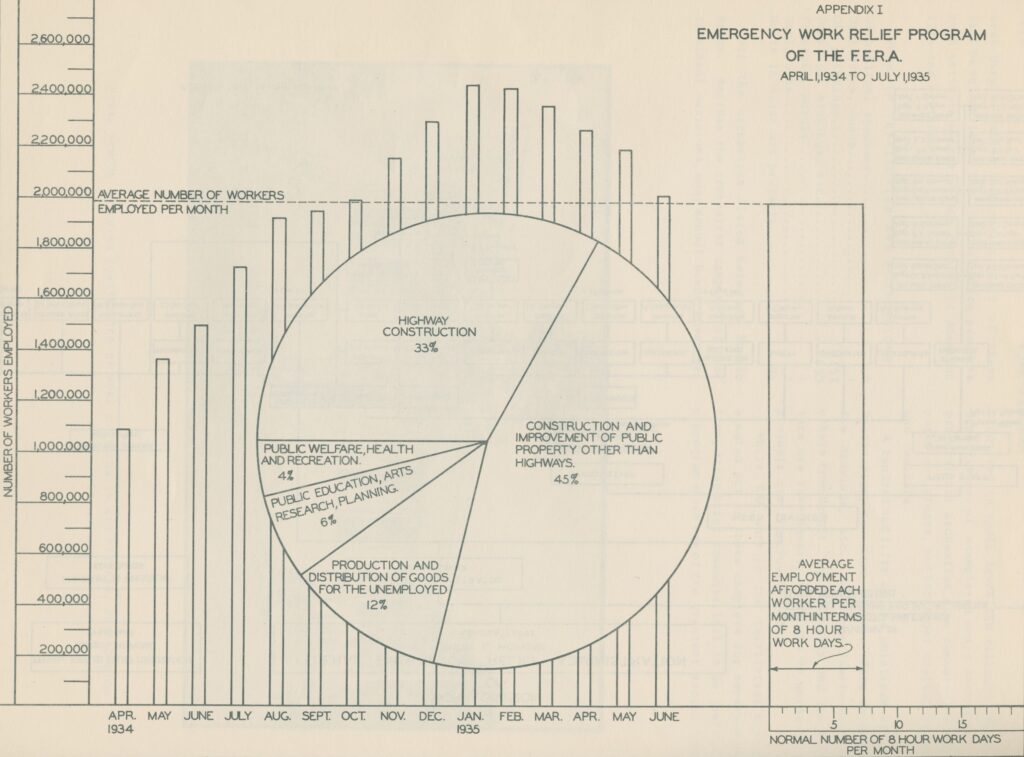

In the spring of 1933, the Roosevelt administration enacted the Federal Emergency Relief Act (FERA), representing one of the first and most expansive New Deal creations. The act was meant to “relieve the hardship and suffering caused by unemployment,” by creating a range of works programs to give idle workers a sense of purpose and a paycheck. Works projects were diverse, but they included highway construction, public education programs, public welfare initiatives, and the production of goods for the unemployed.

Chicago was one of the first cities to receive FERA benefits. FERA was created as a federal and state undertaking, but the federal government bore the lion’s share of funding. The original act appropriated $500 million for relief with the expectation that states would match half of this depending on local need. Illinois had such high unemployment in 1933 that Roosevelt ensured it would be one of the first seven states to receive aid. And of the millions of dollars spent on aid in Illinois between 1933 and 1935, 87.6 percent was covered by the federal government. However, the millions offered in federal funding came with a catch. Money could only be administered at the local level by public institutions. This meant private church groups, religious charities, and ethnic organizations, which traditionally attended to urban welfare work, ceded the role to state welfare agencies.

Questions to Consider:

- Look carefully at the pie chart showing how work was allocated under FERA programs. Which types of work are represented the most here? Why do you think this is?

- Now examine the bar graph charting the number of workers employed by FERA programs monthly. When is employment under FERA the highest? What could account for this? Do these numbers seem surprisingly high or low to you?

Working Men, Not Beggars

The Roosevelt administration’s work-relief programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) meant to give young men across the nation a sense of purpose along with a salary. Chicago and the rest of Illinois supplied a core number of the 2.5 million young men who went into CCC camps located in rural Wisconsin, Oregon, and Washington. CCC camps had a hierarchical structure: officers supervised recruits from across the nation, who planted trees, conserved the soil, and built trails. While CCC workers were allowed to keep a portion of their pay, a significant sum had to be sent home to a mother, a wife, or other family member. Thus, the relief program reinforced a traditional family structure by providing income to a male breadwinner who, presumably, was responsible for dependent women and children.

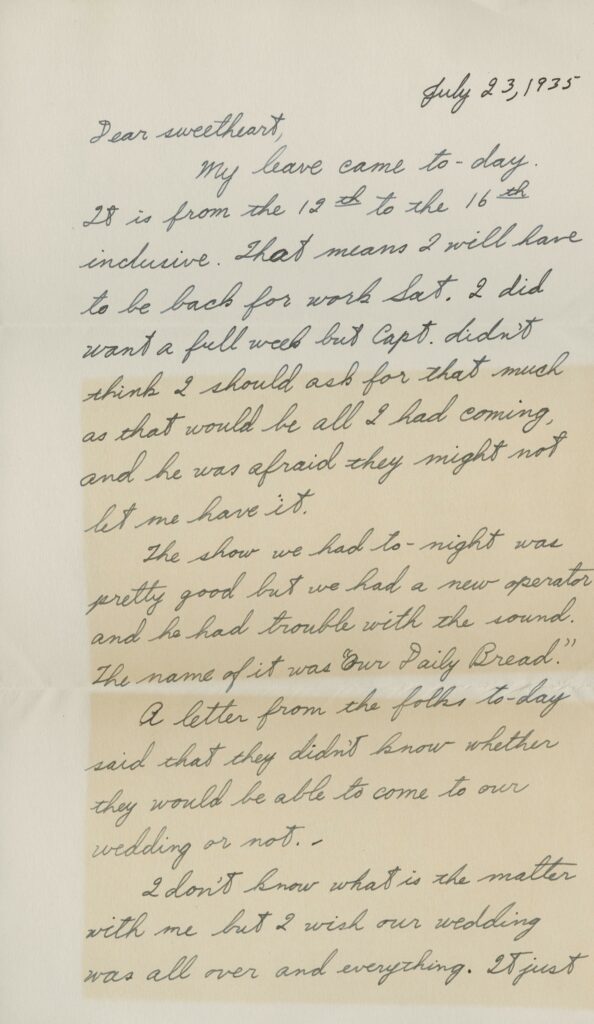

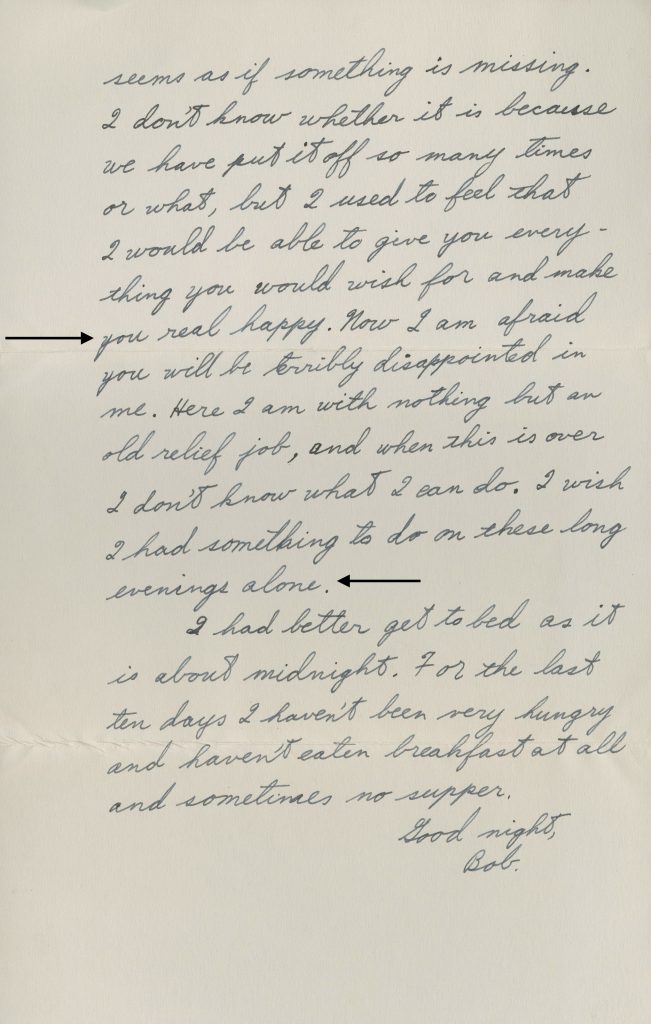

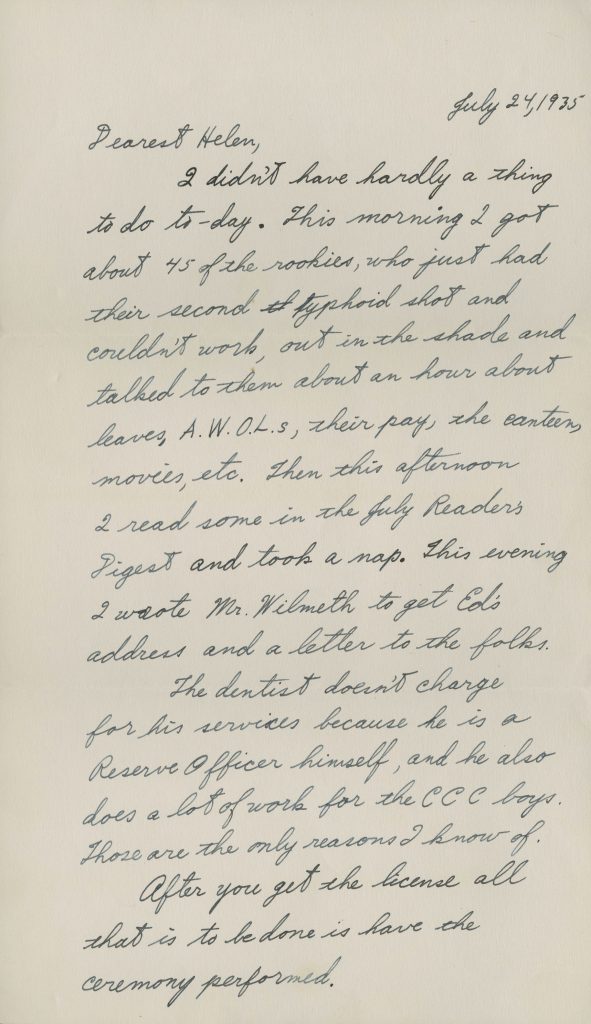

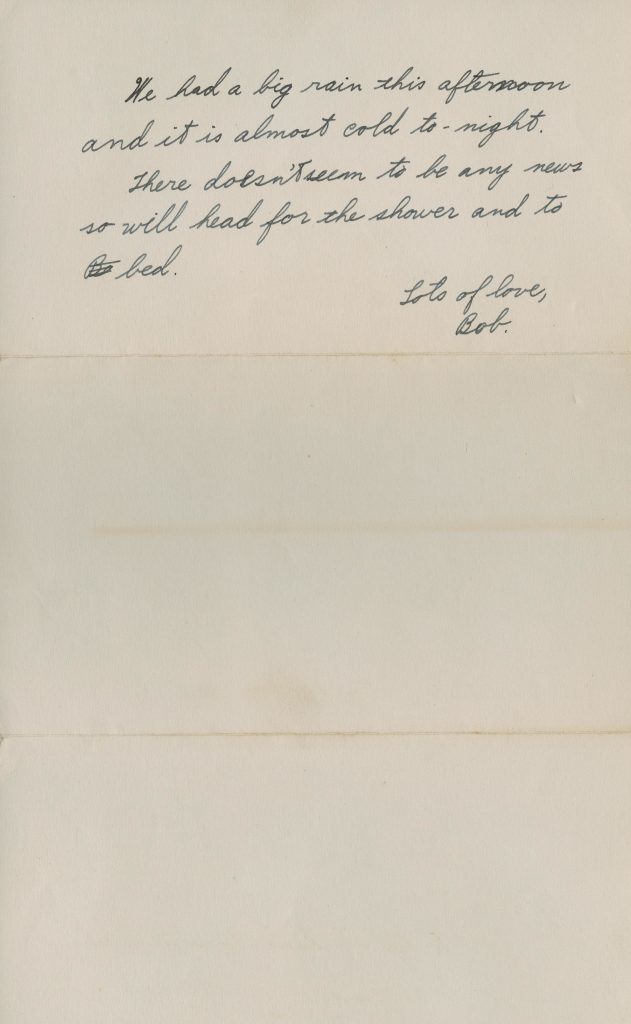

This series introduces Bob Winters and Helen Steele, a couple that came of age in the throes of the Great Depression. In 1934, after graduating from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Bob, like thousands of other young men, could not find a job. In 1935 he turned to the federal government, applying for work as a CCC officer in Wisconsin. With a background in engineering and leadership, he got the job. Throughout his tenure as a CCC officer in various Wisconsin camps, Bob kept up a correspondence with his fiancé Helen, recounting his daily life in the camp, and his feelings about the New Deal initiative. In the summer of 1935, Bob and Helen married in her hometown of Princeton and enjoyed a honeymoon in Dunes State Park. They went on to raise five children together. Their correspondence offers a rare look into the lives of young people and their attitudes toward work aid during the Depression.

The two letters in this collection were drafted by Bob in CCC Camp Sawyer in Sawyer, Wisconsin. In the first, dated July 23, 1935, Bob notifies Helen that he has received leave the following week for their wedding, but that he will have to return after a week. On the second page, he goes on to recount the shame he feels at being unable to support Helen with “nothing but an old relief job.” In the second letter, which Bob sent the following day, he seems to be in higher spirits, yet he begins with “I didn’t have hardly a thing to do today,” a common theme throughout his letters. While Roosevelt intended to create relief jobs in order to avoid this type of melancholy thinking, and convince young people they were providing a service to their nation, Bob seems to feel ashamed he is on federal relief, and time and time again, notes the futility and monotony of his work.

Bob Winters to Helen Steele, July 23, 1935, and July 24, 1935

Questions to Consider:

- Many urban youths, especially from Chicago’s steel yards and working-class neighborhoods found work in CCC camps. Relocating from an industrial center to a rural place like Camp Sawyer must have come as quite a shock to these young men. How do you think new CCC recruits might have viewed the camps? What do you think they thought upon their arrivals?

- Bob stands to the far right next to fellow officers at Camp Loretta, Wisconsin. All four wear their CCC uniforms. In an earlier letter to Helen, Bob mentioned how proud he was of his uniform, noting the time it took him to polish his boots and the care with which he often pressed his jacket. Do these officers remind you of U.S. military officers? Why do you think the federal government might have required CCC workers to wear uniforms and stand in formations? How might the uniforms influence people’s perception of relief work?

- Read through Bob’s letters to Helen and the photograph of their wedding. How does he speak to her? What does he notice and recount about his daily life as a relief worker? Think about how reading Bob’s kind words to his future wife might make the black-and-white photograph come alive.

Including the Excluded

The Works Progress Administration (WPA), a group often conflated with the Public Works Administration (PWA), and Civil Works Administration (CWA), formed the largest, and by far most ambitious, part of Roosevelt’s New Deal programs. The WPA’s main initiative employed millions of Americans building public works across the nation including highways, bridges, buildings, and parks. The WPA sought to jump-start the economy with jobs and improve the national psyche of workers depressed by job loss and destitution. By 1939 Congress had spent 13.4 billion dollars on WPA projects, and nearly every city in the nation had a building, road, or public structure built by WPA workers.

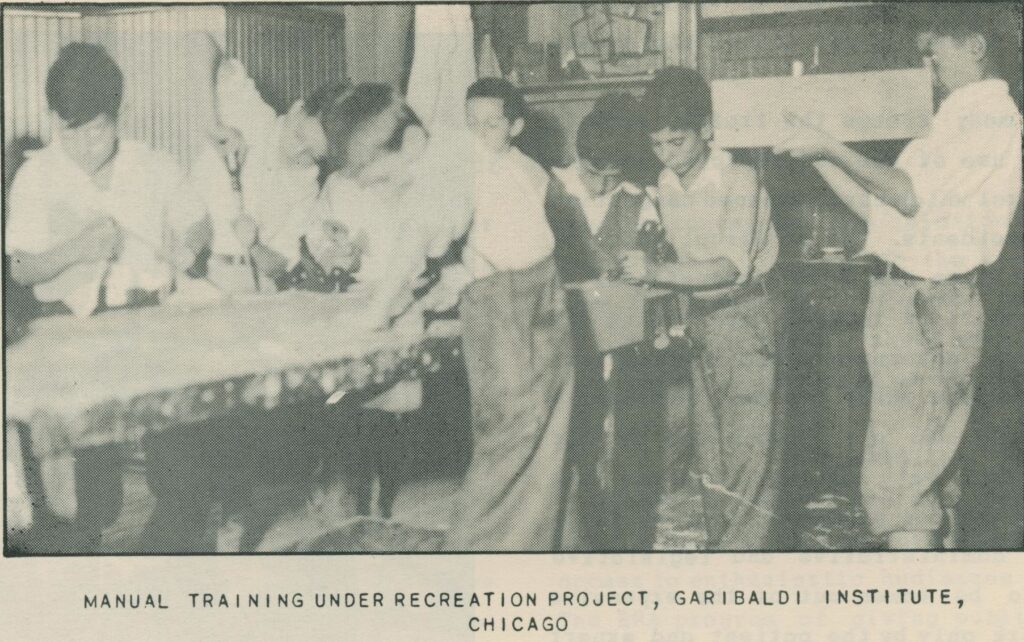

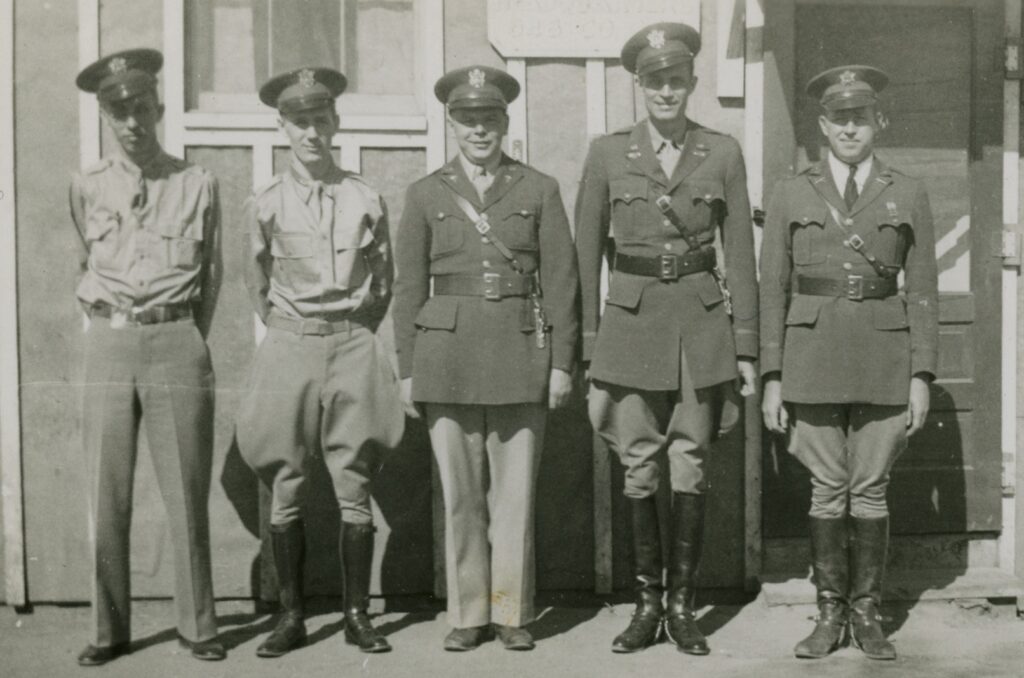

In Chicago the WPA employed tens of thousands of workers. The city had a large population of immigrant and African American industrial workers. When meatpacking, railroad, and steelyard jobs downsized during the Depression, the WPA’s manual labor program provided an appealing alternative. For Italians, Poles, Czechs, and Hungarians, the WPA represented the first time many of their national groups had turned to the federal government for help. Instead of local churches or ethnic societies, which had run charities for their members, ethnic workers began to rely on construction jobs funded by Congress and mandated by President Roosevelt himself. This gave many ethnic workers a new allegiance to the American state. However, in 1939 national WPA programs expelled all non-citizen workers (regardless of legal status) from its rosters, leaving thousands of ethnic workers without a way to feed their families. Thus, the WPA left a complicated legacy for the thousands of immigrants who had yet to take out formal citizenship papers.

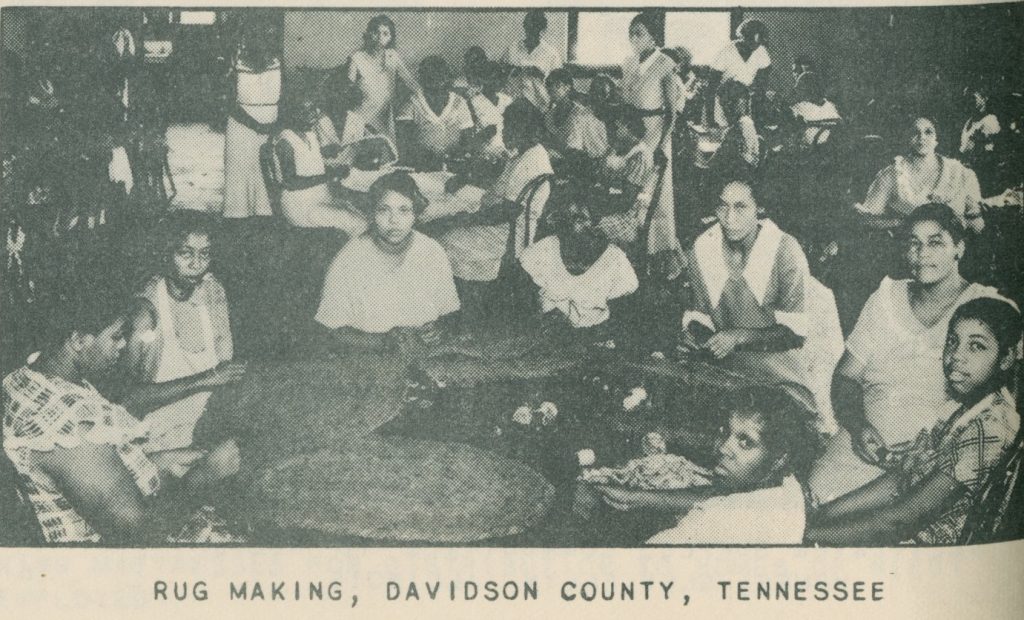

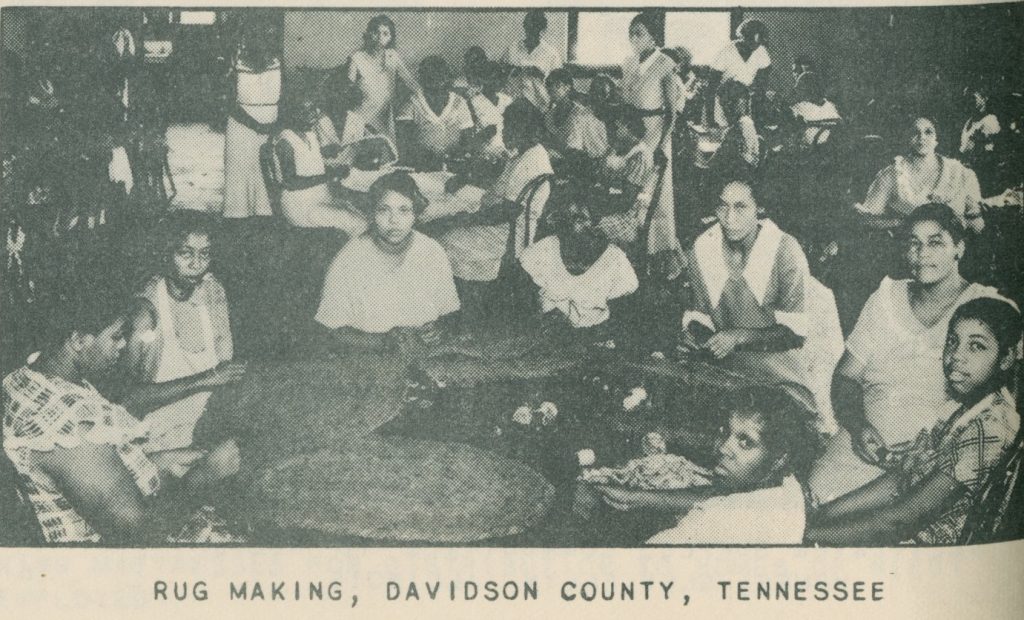

For Chicago’s African Americans, the WPA had an equally complicated history. In Chicago, one-third of all people employed by the WPA were African American. In fact, African Americans depended on WPA jobs more than any other ethnic or national group. However, many blacks experienced discrimination on the job, and reported that they received the most menial, difficult tasks. But fifty-five dollars a month, guaranteed by the federal government at a time of widespread unemployment, proved too appealing for many to pass up. Like immigrant workers, African Americans developed an allegiance toward the federal government and FDR’s Democratic Party that would carry into the next decades.

African Americans engaged in projects to the one in the photograph above across Chicago’s South and West Side, where WPA programs were so popular that thousands of residents began to endorse the Democratic Party. Historian Lizabeth Cohen uncovered this song, popular with black audiences during the 1936 presidential campaign:

You all better vote right on ’lection day

And keep this good ole WPA

Ain’t no ifs ands about it

How you gonna get ’long widdout it?

Questions to Consider

- America’s immigrant communities lent overwhelming support to FDR’s New Deal. Was this for economic reasons alone, or did other factors influence this loyalty?

- African Americans faced discrimination in New Deal programs. In fact, many black Chicagoans claimed the NRA (National Recovery Act) should be renamed the Negro Removal Act. Why, then, was the New Deal so popular in Chicago’s black community?

The Growth of the Arts

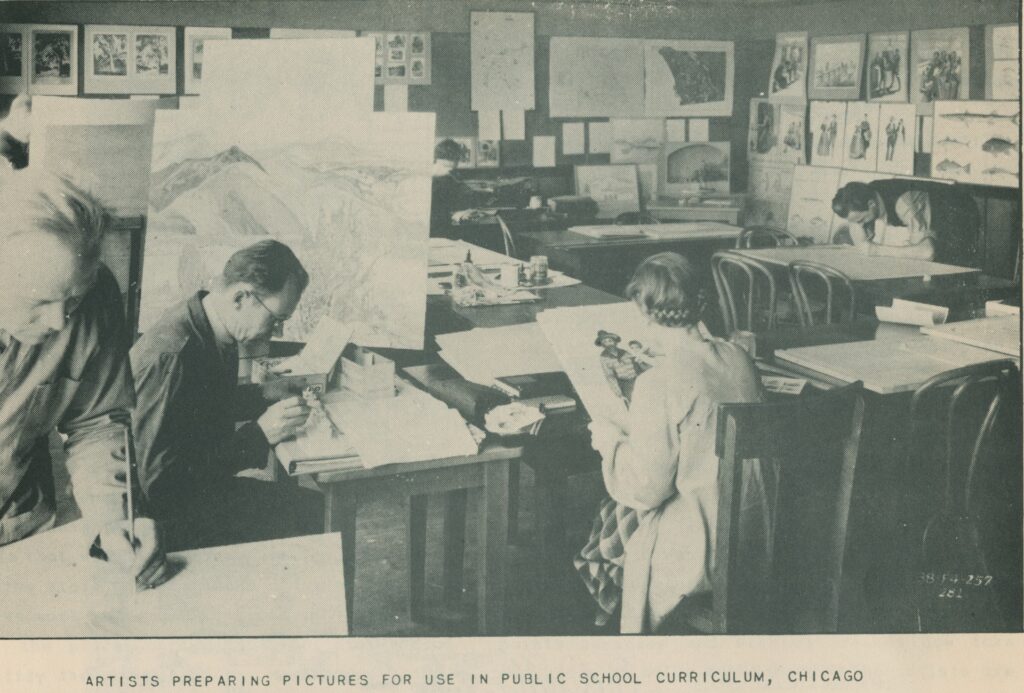

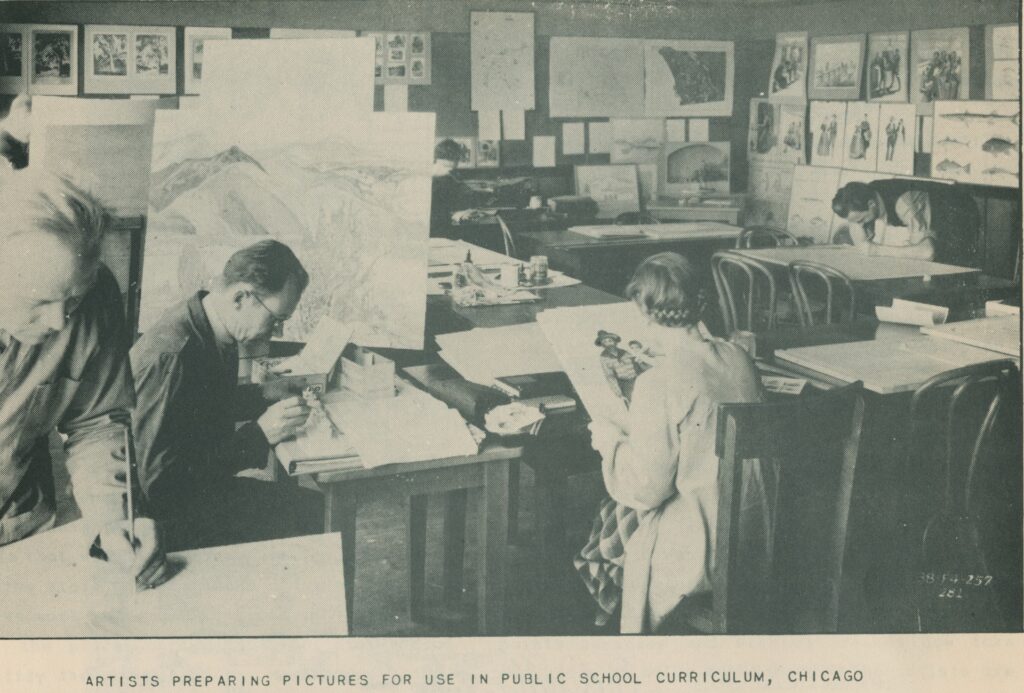

Perhaps the WPA’s most famous program was its cultural initiative, Federal Project Number One, which employed musicians, actors, writers, dancers, and directors in projects meant to create and preserve cultural heritage. Never before or since in American history has the federal government devoted more funds toward the arts, a fact that has left its mark on American cities. United States Post Offices across Chicago, from Lakeview to Clinton to Decatur to Evanston, are decorated with murals. These scenes, which typically depicted scenes of settlers, pioneers, and farm life in the Midwest, gave unemployed artists something to work on. The project also supported arts education, employing local artists in high schools and elementary schools. Just outside Chicago, Deerfield Grammar School features an impressive mosaic mural crafted by WPA artists and Bloom Township High School has scenes depicting possibilities in aviation, agriculture, medicine, and industry, no doubt meant to inspire American youths as they entered into an uncertain economic landscape.

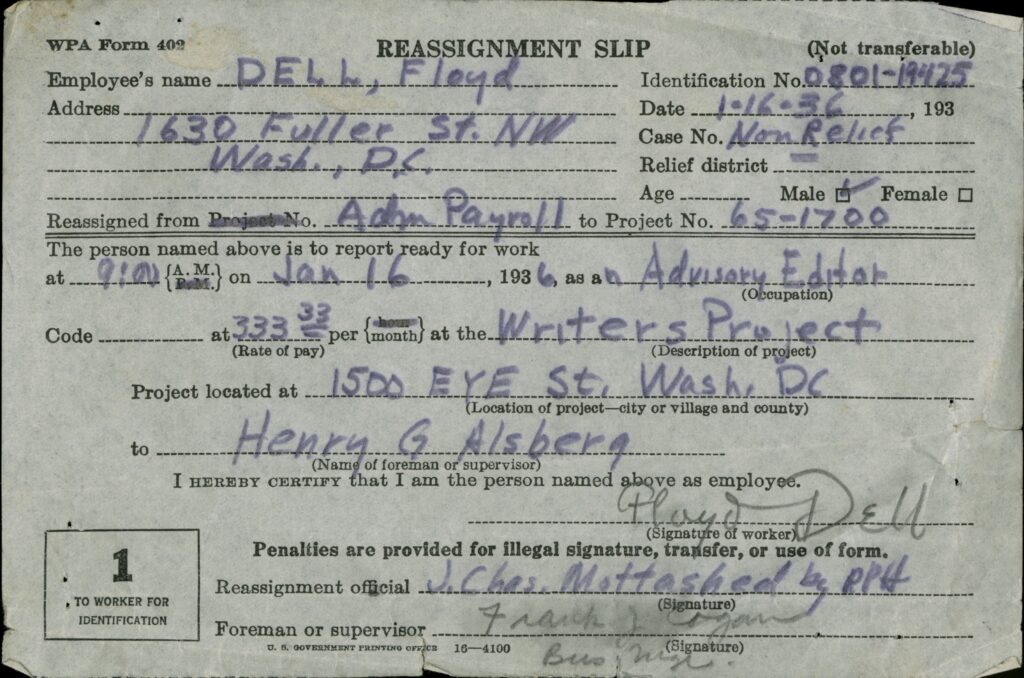

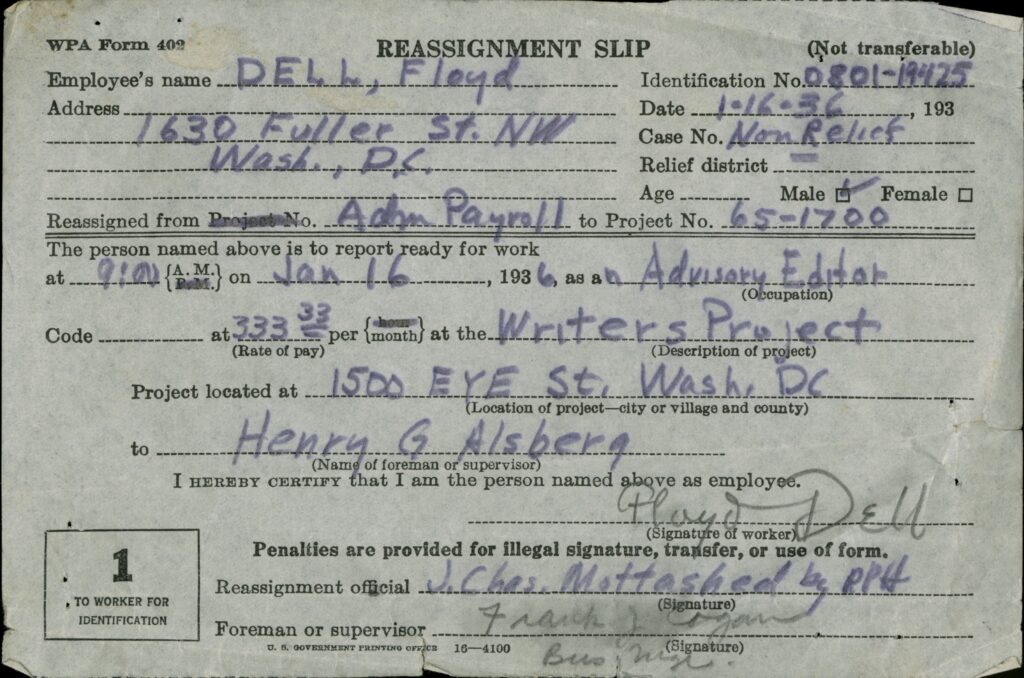

WPA arts programs also benefited writers such as Floyd Dell, an influential American newspaper editor, critic, poet, playwright, and novelist. Dell was born in Barry, Illinois, and spent much of his childhood in poverty, yet reading voraciously at the Quincy, Illinois Public Library. In 1908, Dell escaped to Chicago, where he began his literary career as a book reviewer and editor for the Chicago Evening Post’s Friday Literary Review. In 1919 Dell relocated to New York, where he thrived as an editor for the leftist New Masses and cultivated friendships with influential writers like Theodore Dreiser, Max Eastman, and Edna St. Vincent Millay. Throughout the 1920s, he wrote novels and poetry, but in the economic turmoil brought on by the Great Depression, his work stopped selling, and like many artists, dancers, and fellow writers, Dell turned to the federal government. In 1935 he took a job as a speechwriter and ghostwriter for the WPA, where he remained a steadfast advocate for the federal works program.

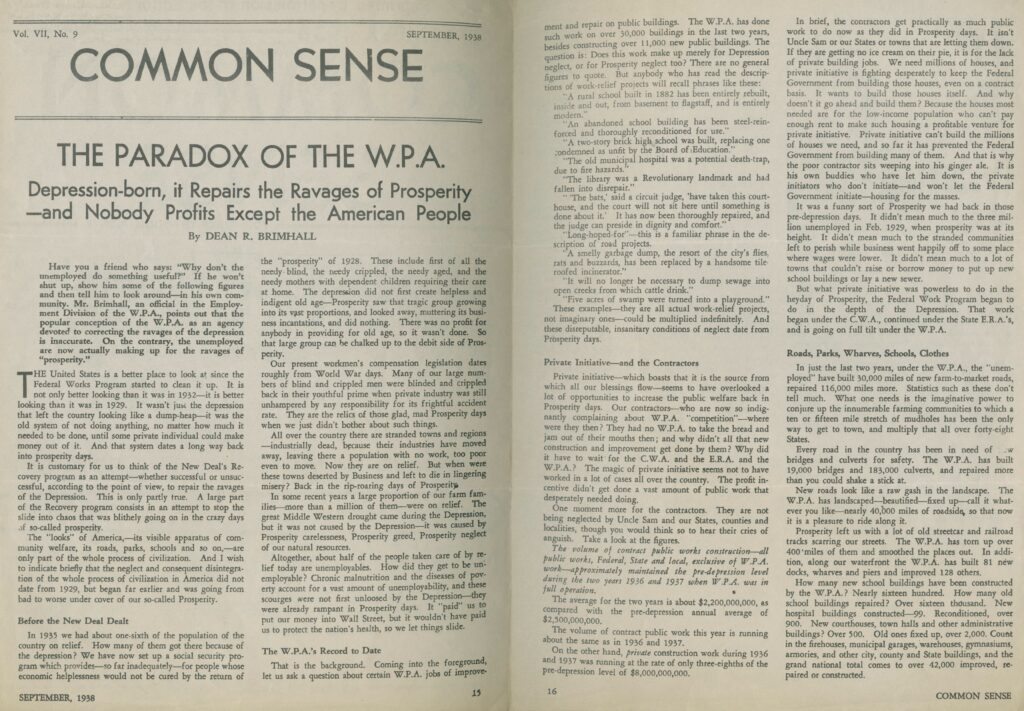

Dell credited the WPA with his economic salvation and remained loyal to the program until 1947. He claims to have ghostwritten the featured article, “The Paradox of the WPA” for the journal Common Sense in September of 1938 in which he enumerates the benefits of the works program for American civilization. Far from a mere recovery plan, Dell reminds readers that WPA programs, which repaired roads, improved parks, and built schools, benefited the “whole process of civilization in America.” For instance, WPA workers built 30,000 farm-to-market roads, repaired 116,000 miles of road, and beautified 40,000 miles of roadside. Far from an exercise in busywork, Dell reminds his readers and critics that these tasks needed to be undertaken for the advancement of the quality of life of all Americans.

Dean R. Brimhall (ghostwritten by Floyd Dell) “The Paradox of the WPA,” Common Sense, vol. 7, no. 9 (September 1938)

Questions to Consider:

- A federal publication on the FERA features Chicago artists hard at work producing art for the Chicago Public School curriculum. How do you think these artworks benefited local schools? How might artists have felt when the federal government suddenly offered them money to develop and share their craft? Do you think artists always viewed WPA programs positively?

- In “The Paradox of the WPA,” Dell urges readers to consider WPA programs as necessary programs. After reading the article yourself, are you convinced? Was the WPA initiative a fortuitous program that saved the crumbling infrastructure of America? What would the nation look like if there had been no WPA program?

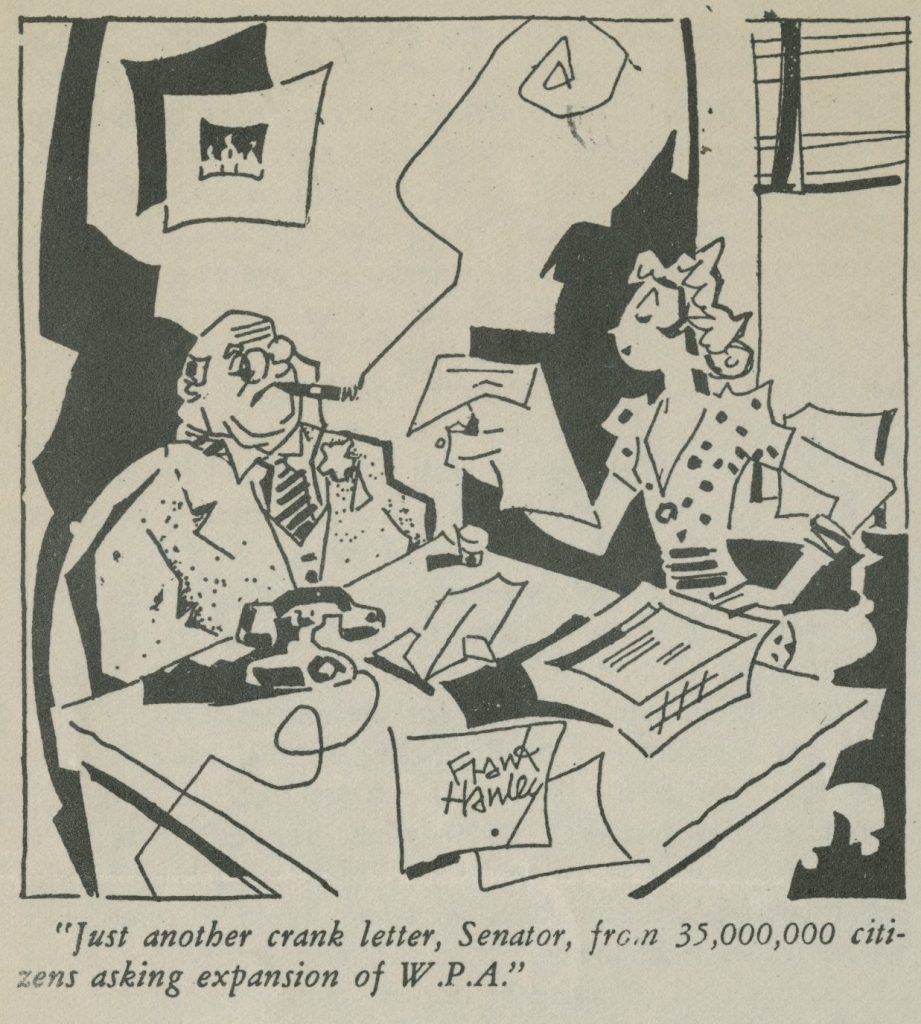

- Now look at the political cartoon, which ran alongside Dell’s article in Common Sense in September 1938. What does this suggest about how many Americans and legislatures thought of the WPA?

- Finally, examine Floyd Dell’s reassignment slip to the WPA, an excellent example of a New Deal artifact. What is his title? How much did Dell make as a writer? How do you think his salary corresponded with pre-Depression paychecks?

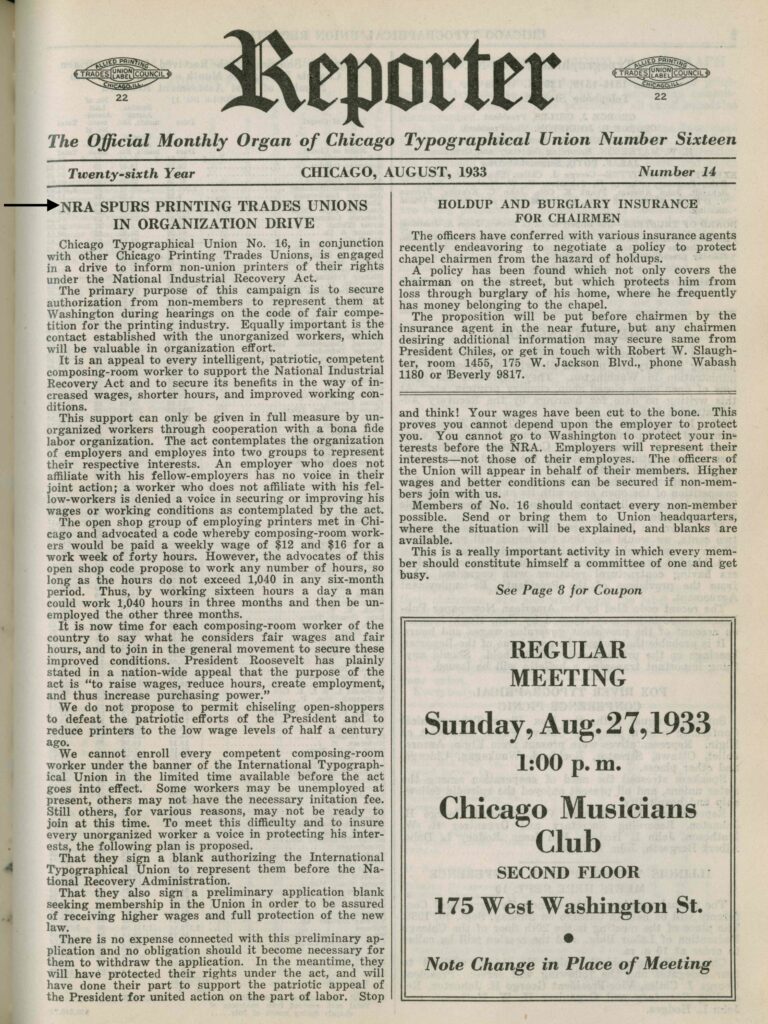

A Space for Unions

The New Deal changed the game for organized labor in America. In 1933, Roosevelt’s National Recovery Administration (NRA) brought industry and labor together to write “codes of fair competition.” The codes helped workers by setting minimum wage and maximum working-hours for the first time. While the Supreme Court declared the NRA unconstitutional in 1933, many of its provisions reappeared in the National Labor Relations Act (also known as the Wagner Act) in 1935. The Wagner Act set up the government as the final arbiter in all disputes between unions and business. Under its terms, a three-member National Labor Relations Board protected the power of most workers to form unions and collectively organize. Most importantly, the Act made it illegal for businesses to fire employees engaged in union activity.

The NRA and the Wagner Act paved the way for America’s age of unionism, which would come to characterize industrial cities across America’s Rust Belt after World War II. Workers in cities like Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Detroit, Toledo, and of course Chicago jumped at the opportunity to organize steelworkers, meatpackers, and automobile workers. The legislation made it possible for the rise of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), a powerful union that arbitrated victories for thousands of unskilled workers across the nation. While the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act reversed many of the provisions set in place by the Wagner Act, historians and scholars view the New Deal as the dawn of America’s age of unions, and the heyday of America’s working class.

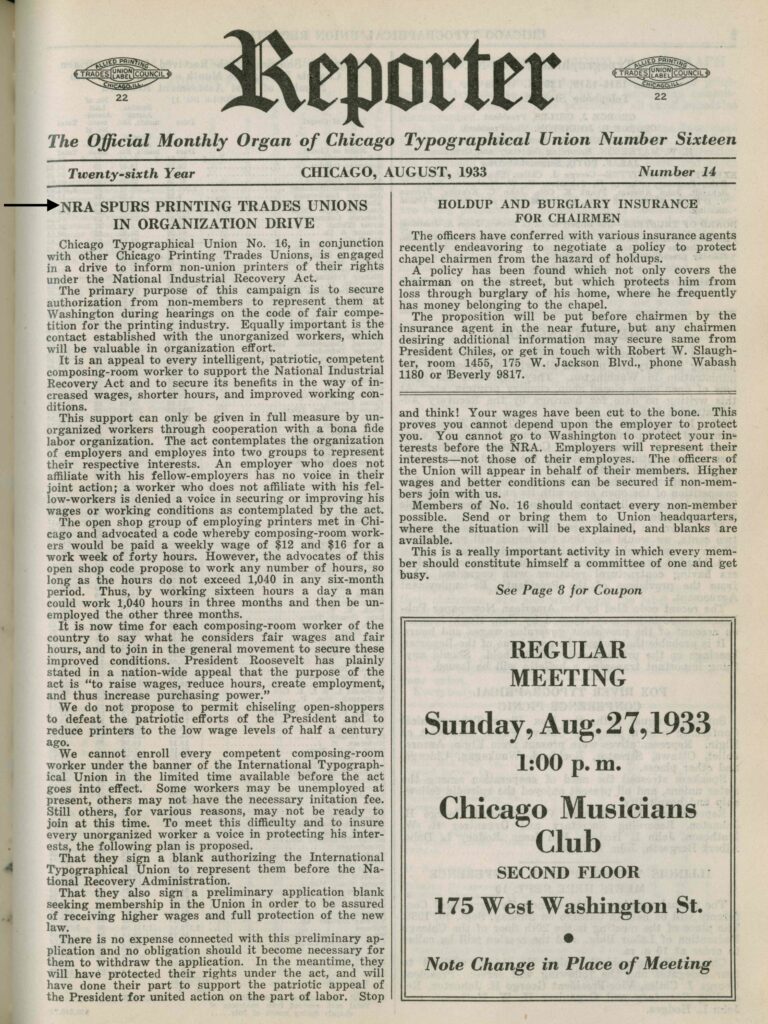

Here we see an article featured in the Reporter, the Chicago Typographical Union’s official paper that emphasizes the importance of New Deal initiatives to early unionization. The Typographical Union printed this August 1933 issue immediately after Congress enacted the NRA in order to inform other printers of their rights under new labor laws. In the article, “NRA Spurs Printing Trades in Organization Drive,” unionized printers encourage “intelligent, patriotic, competent” printers to support Roosevelt and join some type of union. This reveals that before the New Deal, many workers remained “open shop” (non-unionized) because they were afraid employers and large companies would exclude unionized workers.

Questions to Consider:

- Read the Reporter’s article on the NRA. What does the article want from non-unionized typographical workers? What does its focus imply about the understanding many workers have of emerging New Deal programs?

- Think about Chicago unions today. Which unions are the most powerful in Chicago? Who do they affect the most? How might the New Deal have set the stage for their rise?

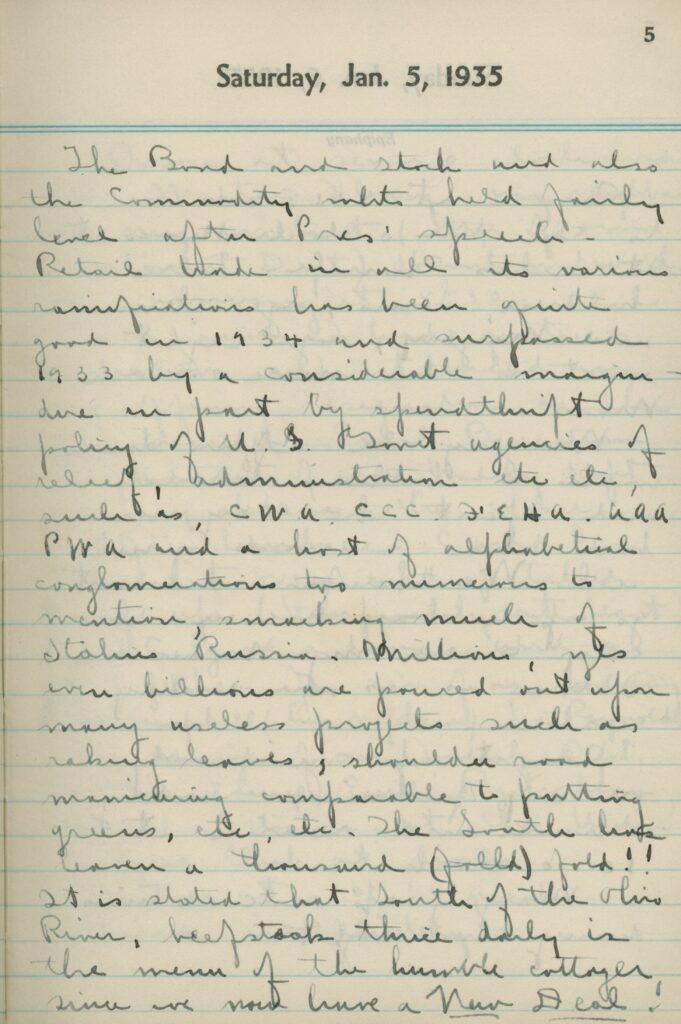

Opponents of the New Deal

With a radical new administration and an expansion of federal programs came a host of opponents. Most working people, especially immigrants and African Americans supported the New Deal and idolized Roosevelt, but many of Chicago’s moneyed elites became intensely critical of the president’s new programs. They argued that the president had begun to abuse his executive power, and feared their own success might be in jeopardy if welfare programs, which required steep taxes, continued to increase.

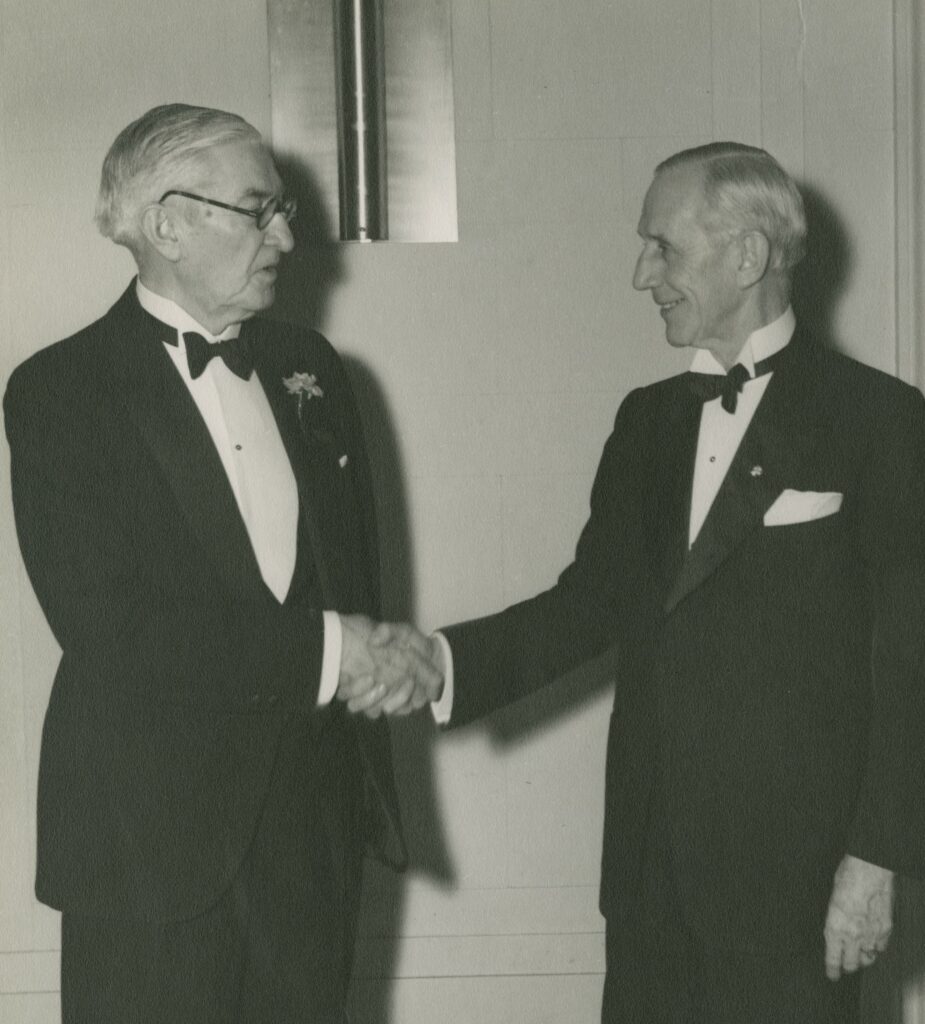

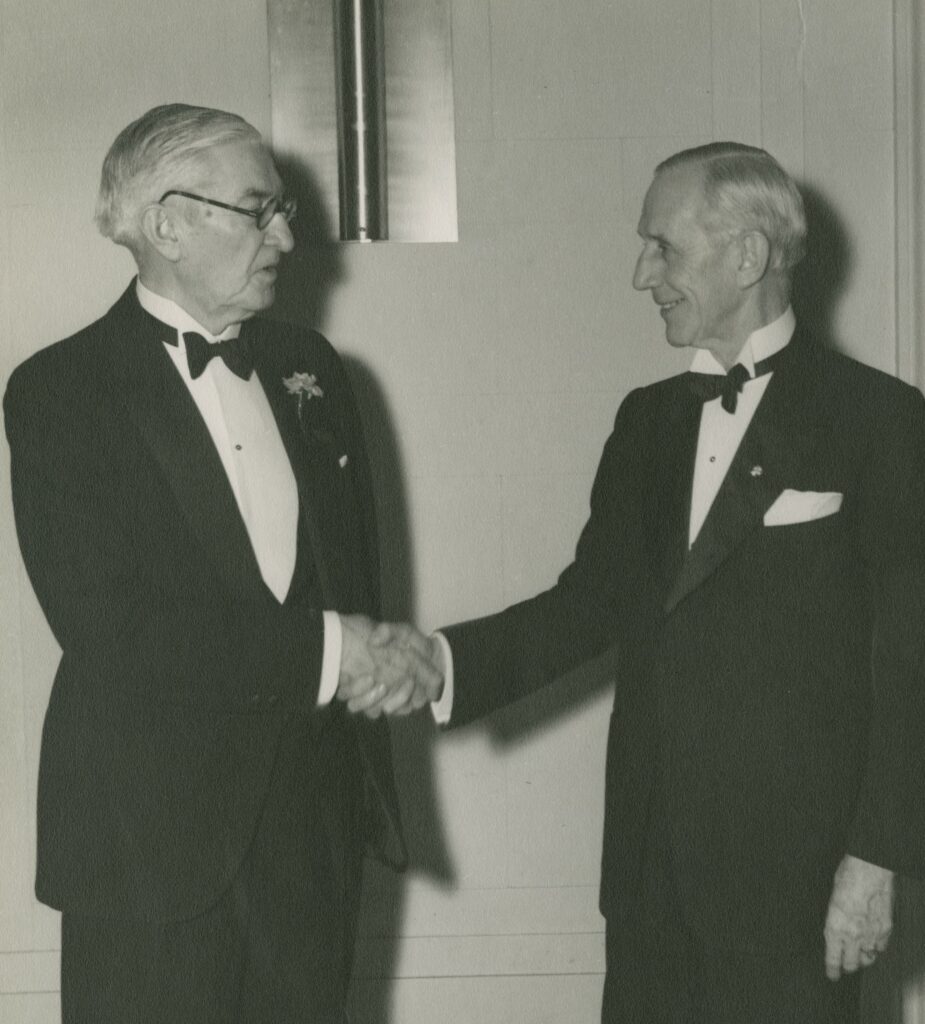

John McCutcheon and George Ade represented two powerful and influential Chicagoans who became deeply critical of Roosevelt’s New Deal. Both published for the Chicago Tribune and became voices of opposition to the growing welfare state. Ade met McCutcheon at the Chicago Record in 1896, where the two became friends and worked together on satirical human-interest stories and political cartoons. In 1904 Ade retired to an enormous estate in Indiana named Hazledon, and kept regular contact with McCutcheon who remained at the Chicago Tribune. McCutcheon drew cartoons for the paper, exposing his critical views on New Deal politics, regularly questioning whether or not new programs had actually stimulated the economy. Meanwhile, Ade continued to publish from Hazledon. In March of 1938 he authored an article in Forum entitled “The Implications of the New Deal,” a critique of Roosevelt’s programs for implying “that our fellow-citizen who has arrived somewhere is probably a bad egg while the down-and-outer is on his uppers because some one has deliberately robbed him.” Standing up for businessmen and employers, Ade reminded the American people not to believe that “every man who sits at a desk and is making an effort to protect the interests of certain stockholders is a villain, while the man on relief is a hero who has been robbed of his heritage.” The words of Ade and cartoons of McCutcheon revealed that a segment of Americans were beginning to resent relief and recovery programs.

Louis J. Cross was precisely one of these Americans. Cross was born in 1898 in rural Illinois to poor immigrant parents, yet he excelled in school and by 1929 be began a career as a stockbroker at Chicago’s Paul H. Davis & Co.

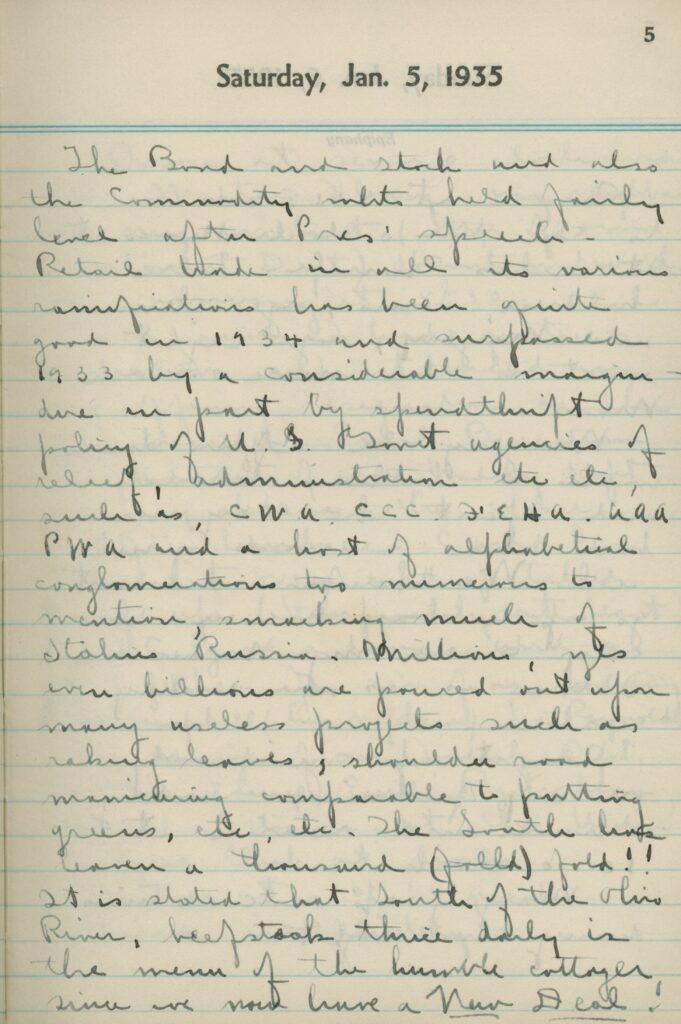

A successful stockbroker and investment banker, Cross kept a daily diary of his engagement with elite organizations like the Chicago Yacht Club, the Saddle and Cycle Club, and the Germania Club along with his ideas about politics. His views about Roosevelt and the New Deal were extremely critical. In January of 1935, he even accused Roosevelt’s “alphabet soup” programs of “smacking of Stalinist Russia.”

Questions to Consider:

- Based on the photograph and diary entry, why do you think someone might oppose the New Deal? What do you find persuasive or not persuasive about their critique of New Deal policies?

- Think about current political debates on CNN, Fox News, and MSNBC. What similarities do you see between criticisms and arguments of the 1930s and those raging in contemporary politics?

Further Reading

Margot Canaday. The Straight State: Sexuality and Citizenship in Twentieth Century America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Lizabeth Cohen. Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919-1939. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Steve Fraser and Gary Gerste, eds. The Rise and Fall of the New Deal Order, 1930-1980. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.