Introduction

In November and December of 1904, the New York writer Upton Sinclair spent seven weeks in Chicago’s meatpacking district—the Union Stock Yard and the surrounding neighborhood, known as Packingtown or Back of the Yards. Sinclair arrived in the city in the wake of a labor strike that had ended disastrously for the workers: Thirty thousand packinghouse workers and their allies in other trades had walked off their jobs in order to demand a minimum wage of 20 cents an hour ($5.32 in today’s dollars). But, as historians David M. Katzman and William A. Tuttle explain, the strike “was hopeless from the beginning. The nation was in a depression, unemployment was rampant, and, caught up in their own woes, as many as 5,000 people lined up outside the stockyards each morning to replace the strikers. After 10 weeks, the strikers, sullen and beaten, drifted back to work.”

Working-class neighborhoods drew the attention of sociologists and reformers who became directly involved in efforts to improve workers’ quality of life.

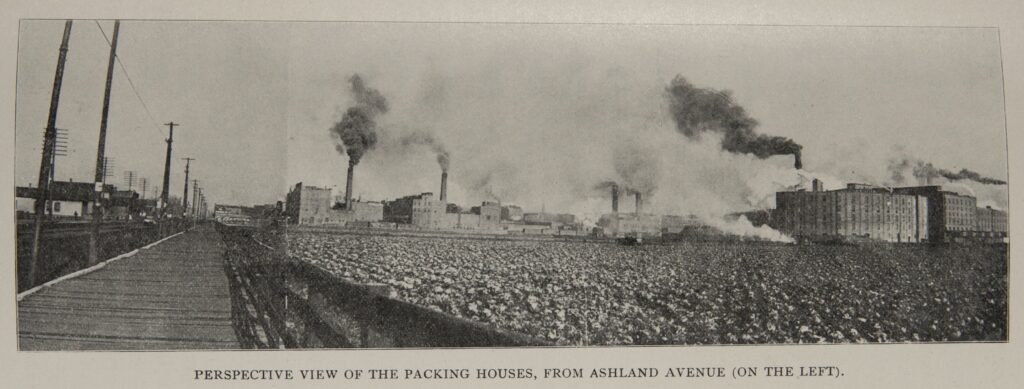

Sinclair wanted to take up the workers’ cause by writing an exposé of the brutal conditions they endured. These conditions were the result of a few decades of rapid changes in food manufacturing in the late nineteenth century. Following the end of the Civil War in 1865, Chicago’s various, scattered livestock markets consolidated into one large market, the Union Stock Yard, on the South Side. This market was uniquely well situated to benefit from changes taking place across the nation: During the 1870s and 1880s, the United States wrested new territory from American Indians west of the Mississippi. Railroads extended their reach throughout the West, allowing farmers and ranchers both to settle new lands and to ship their cattle, sheep, and hogs to national markets. Chicago became the transfer point where the agricultural produce of the West reached buyers for consumer markets in the East.

With the consolidation of the stockyard, the work of processing meat itself changed dramatically. Meatpacking was one of the first industries to implement modern, “rational” production methods. As historian James R. Barrett explains, into the 1880s, butchers were skilled, well-paid craftsmen. Technological advances in refrigeration and preservation allowed entrepreneurs like Philip Armour and Gustavus Swift to turn butchering into a large-scale operation. They introduced the division of labor into their meatpacking plants, replacing the skilled “all-around butcher” with a “killing gang of 157 men divided into 78 different ‘trades,’ each man performing the same minute operation a thousand times during a full workday.” These unskilled workers were paid a fraction of the craftsman’s former wages. As Sinclair vividly illustrates in The Jungle, they were driven at an unrelenting pace that led to frequent accidents and were hired and fired according to the employers’ needs with no guarantees of steady employment or compensation for workplace injuries.

Sinclair wanted to reveal this systematic exploitation of workers and to galvanize reform. He published The Jungle, first, in installments in the Socialist newspaper Appeal to Reason in 1905, then, the following year, as a freestanding novel. It became an international bestseller within weeks, embraced most famously by President Theodore Roosevelt. While Roosevelt rejected Sinclair’s Socialist politics, he suspected there was truth to Sinclair’s account of conditions in the meat-processing plants and, following a federal investigation, pushed Congress to pass the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act in June 1906. The novel did not have the same tangible, political effect on Sinclair’s real cause: workers’ rights. Meatpacking workers did not even try to form a union again until World War I, a decade later.

Teachers and students can explore the social and political context for Sinclair’s novel through several Newberry Digital Collections for the Classroom, including, Chicago Workers during the Long Gilded Age, Immigration and Citizenship in the United States, and Subversives in the City: Political Radicalism in Chicago. The collection of documents below focuses on neighborhood and community life for workers such as the ones Sinclair portrays in The Jungle. Back of the Yards and other working-class neighborhoods drew considerable attention from sociologists and reformers at the turn of the century. They used maps, tables, and photographs to document conditions in the neighborhoods, and they became directly involved in efforts to improve the workers’ quality of life. Often they saw real change: according to most reports, living conditions in Back of the Yards had improved significantly by the end of World War I.

Essential Questions

- What did it mean to live in the neighborhood of the Union Stock Yard around 1900? What conditions did workers experience outside of the packing plants, in their homes and streets?

- How did the Back of the Yards neighborhood compare to other Chicago neighborhoods at this time? In what ways was the neighborhood connected to or cut off from the rest of the city?

- Who lived in Back of the Yards around 1900? What was the neighborhood’s demographic makeup?

- How did researchers and reformers approach the stockyard neighborhood? What problems did they identify? What solutions did they propose? Does it matter that, like Sinclair, they came from outside the communities they wanted to change?

- In what ways do the documents created by sociologists and urban reformers reframe or complicate Sinclair’s representation of the lives of meatpacking workers?

Mapping the Stockyard Neighborhood

The University of Chicago established the nation’s first department of sociology in 1892, when the university itself was founded. The department pioneered the academic study of urban life, making innovative use of surveys and maps. Many of its members, particularly during the first decades, were deeply involved in progressive reform movements. Charles J. Bushnell wrote his U of C doctoral dissertation on the community that lived around the Union Stockyard, and published it in 1901 in the American Journal of Sociology.

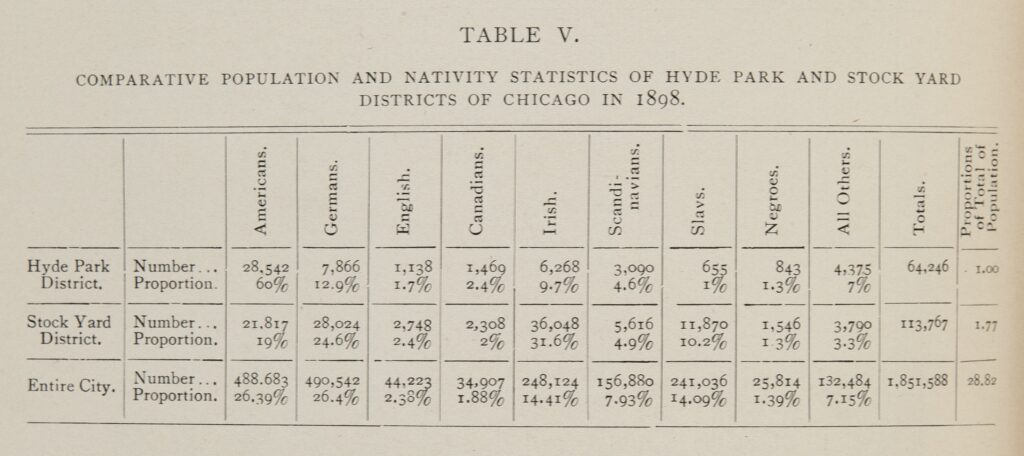

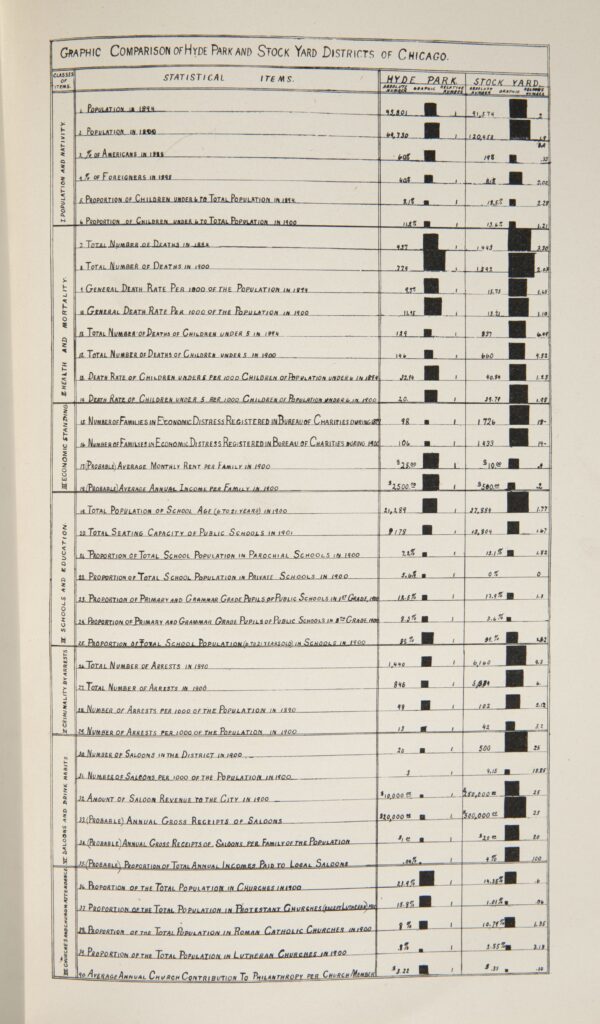

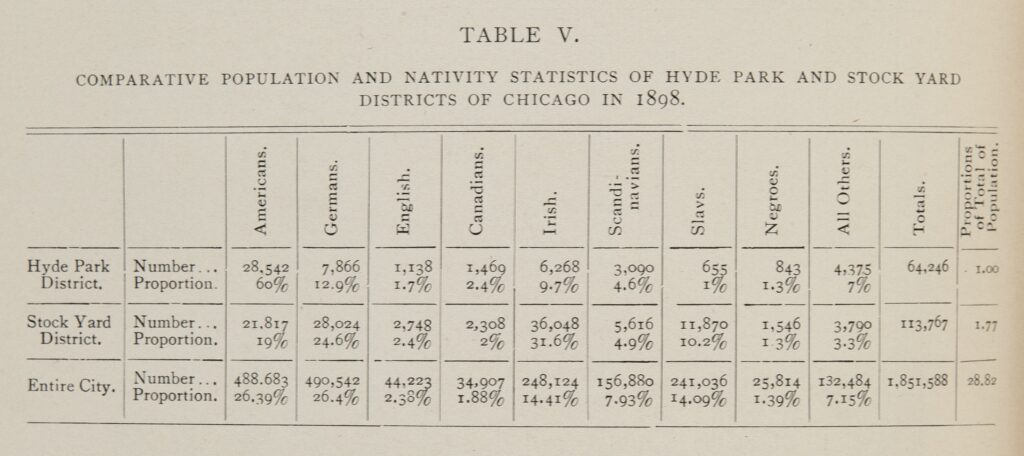

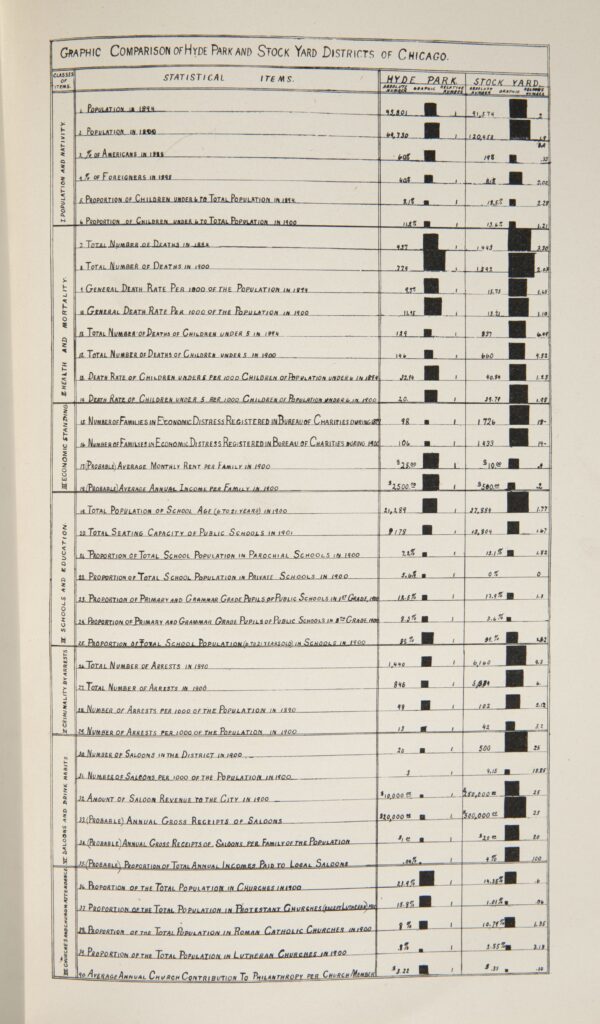

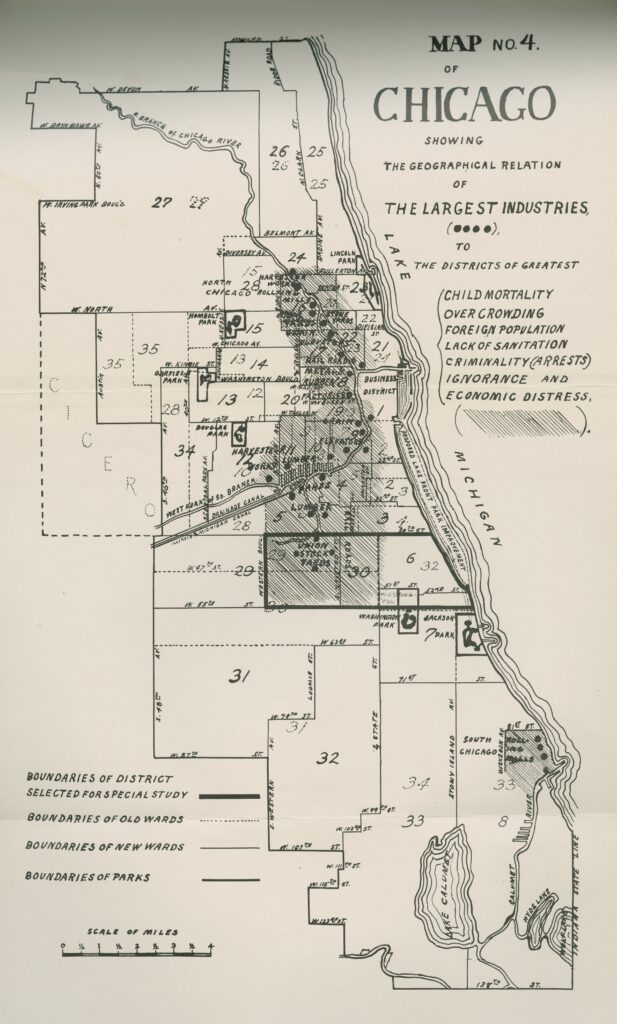

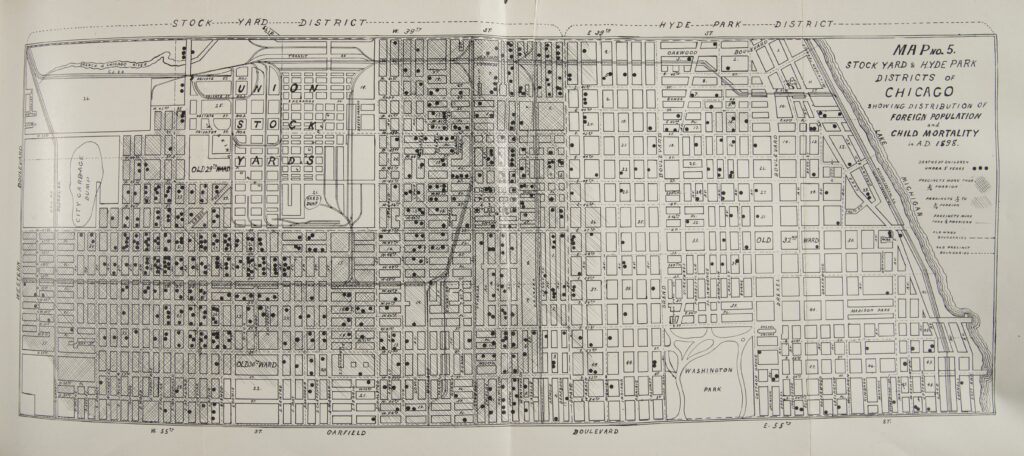

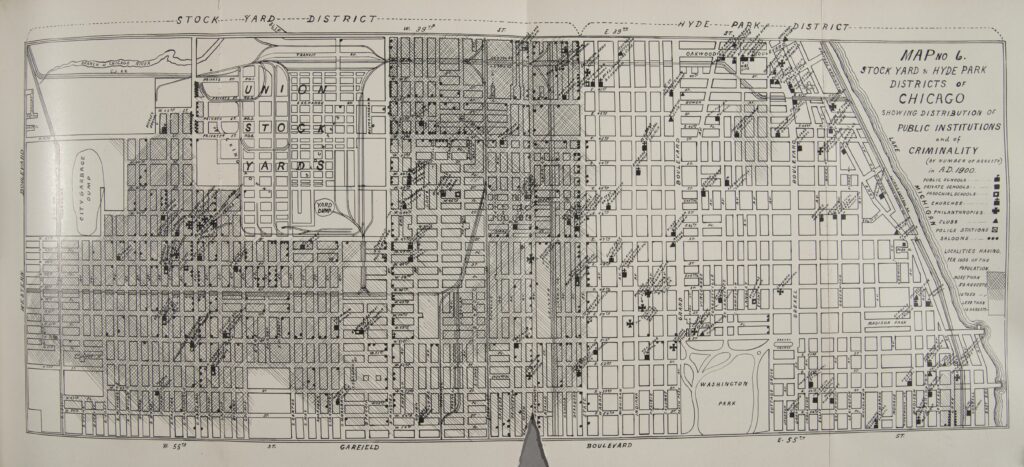

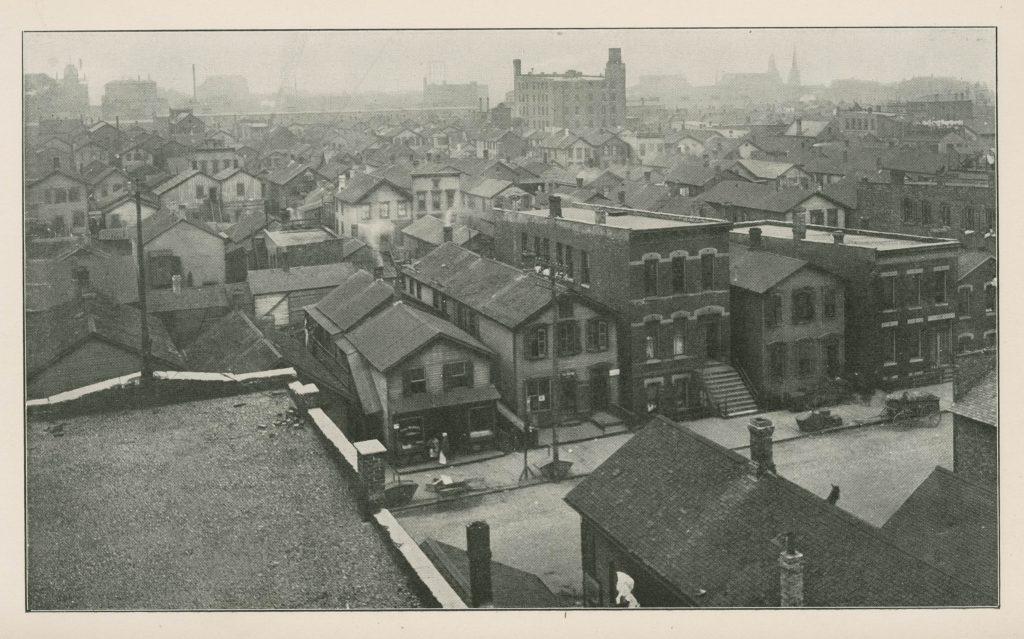

In the maps below, Bushnell offers visual representations of the stockyard area’s demographic makeup and draws a striking contrast between this working-class enclave and the nearby neighborhood of Hyde Park, where the University of Chicago was located. Unlike some of his contemporaries, he did not attribute the neighborhood’s problems to its heavily immigrant population but argued that the contrast to Hyde Park could “often be accounted for by municipal neglect, insufficient public revenue, and scales of wages inadequate to furnish the comforts, and sometimes even the decencies, of life.”

Though not noted on Bushnell’s map, the stockyard area was itself divided into two neighborhoods: Back of the Yards, to the west and south of the Union Stockyard, consisted largely of Eastern European meatpacking workers. Canaryville, to the east of the stockyard, included more Irish and middle-class residents who worked as clerks, managers, and cattle buyers. Historian Robert A. Slayton notes that residents of Back of the Yards drew further distinctions within the neighborhood: The newest immigrants lived in the least desirable location, closest to the yards. Those with more means moved south of 47th Street.

Charles J. Bushnell, “Map No. 4 of Chicago Showing the Geographical Relations of the Largest Industires”, “Map No. 5 Stock Yard & Hyde Park Districts of Chicago Showing Distribution of Foreign Population and Child Mortality in A.D. 1898,” and “Map No. 6 Stock Yard & Hyde Park Districts of Chicago Showing Distribution of Public Institutions and of Criminality in A.D. 1900” (1901)

Questions to Consider

- Examine the maps in this section. Identify the street boundaries of the stockyard neighborhood and of Hyde Park. What are the major physical features of each neighborhood, as shown in these maps? Where are they in relation to downtown Chicago? Why do you think Bushnell chose to include this comparison to Hyde Park in his study of Back of the Yards?

- How do the neighborhoods compare in their ethnic compositions; their rates of criminality, child mortality, and poverty; and their public institutions? Do the maps suggest variations within each of the neighborhoods?

- Why do you think Bushnell chose to feature this information? Is there other information about these populations that you would like to see represented here? Why?

- Do you think that a resident of the stockyard neighborhood would map it in the same way? What are the advantages and the limitations of Bushnell’s perspective as a sociologist and an outsider?

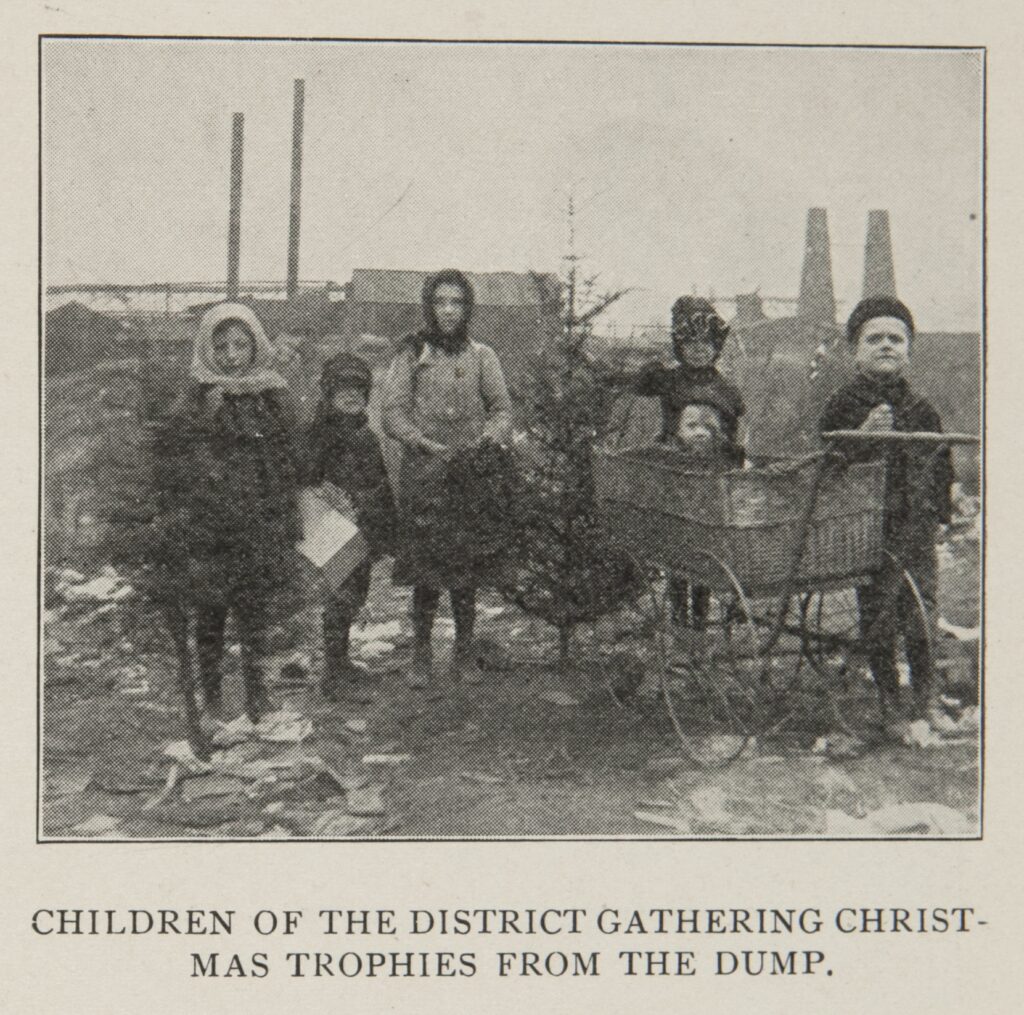

Living Back of the Yards

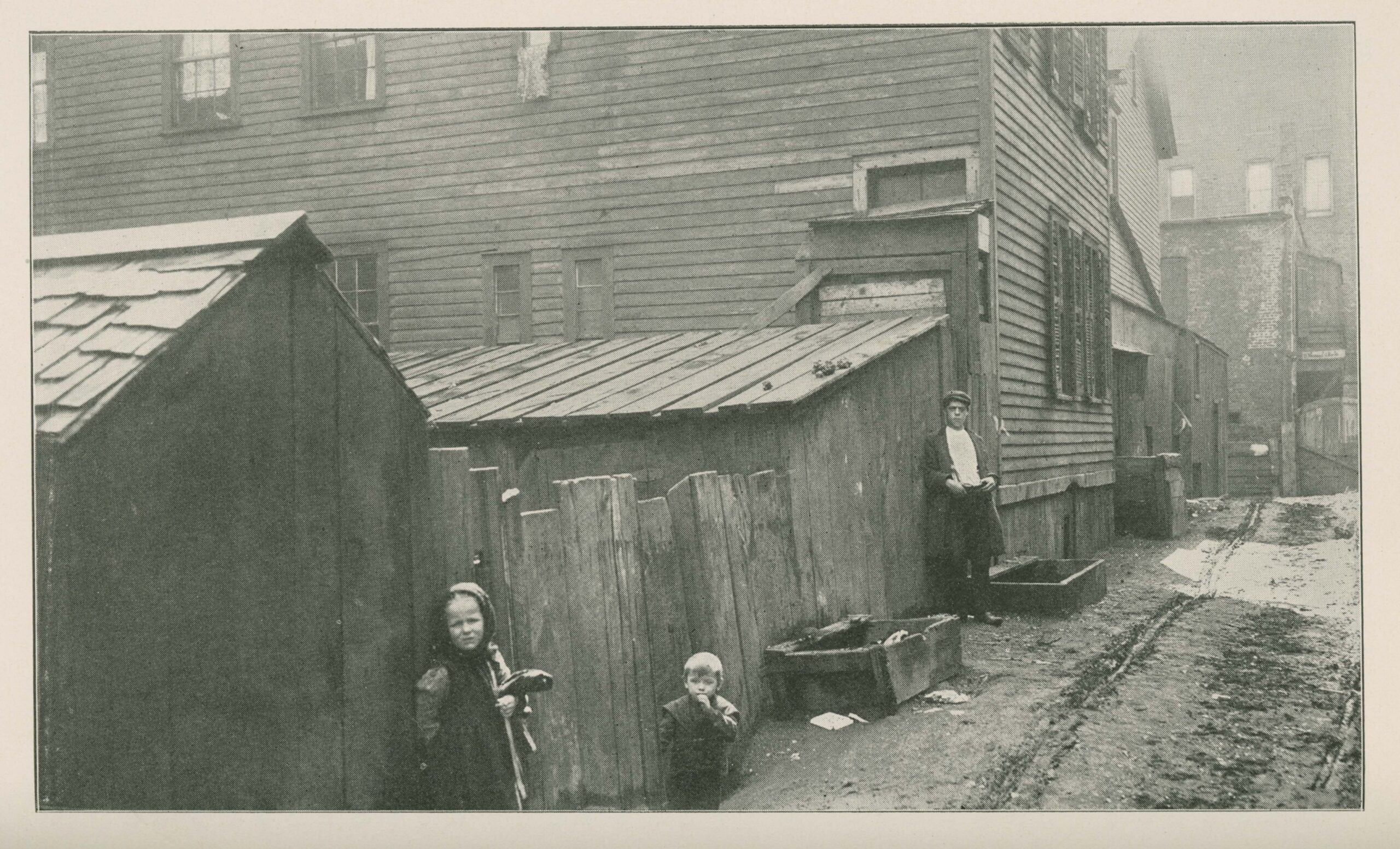

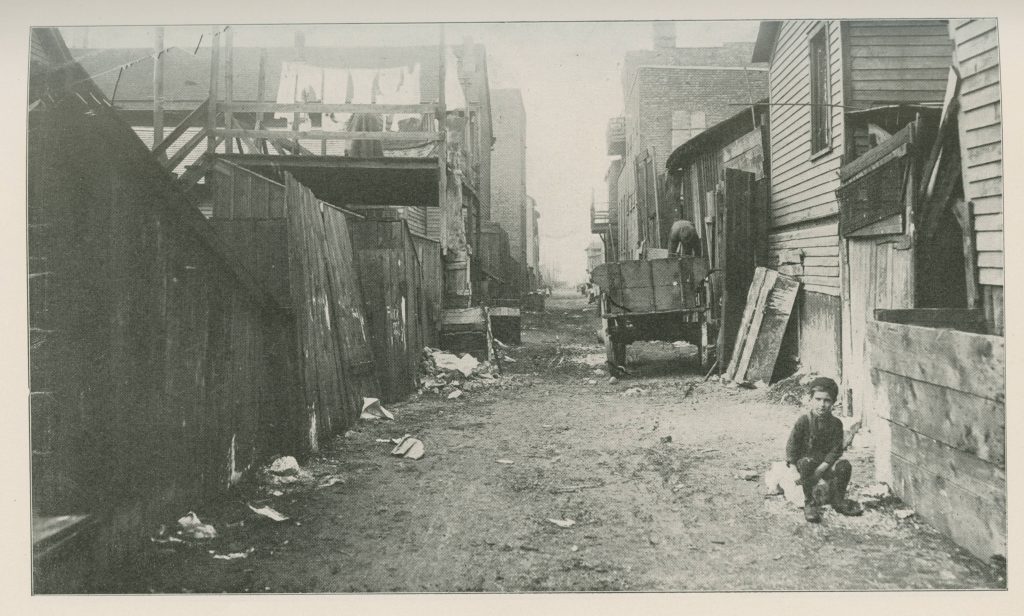

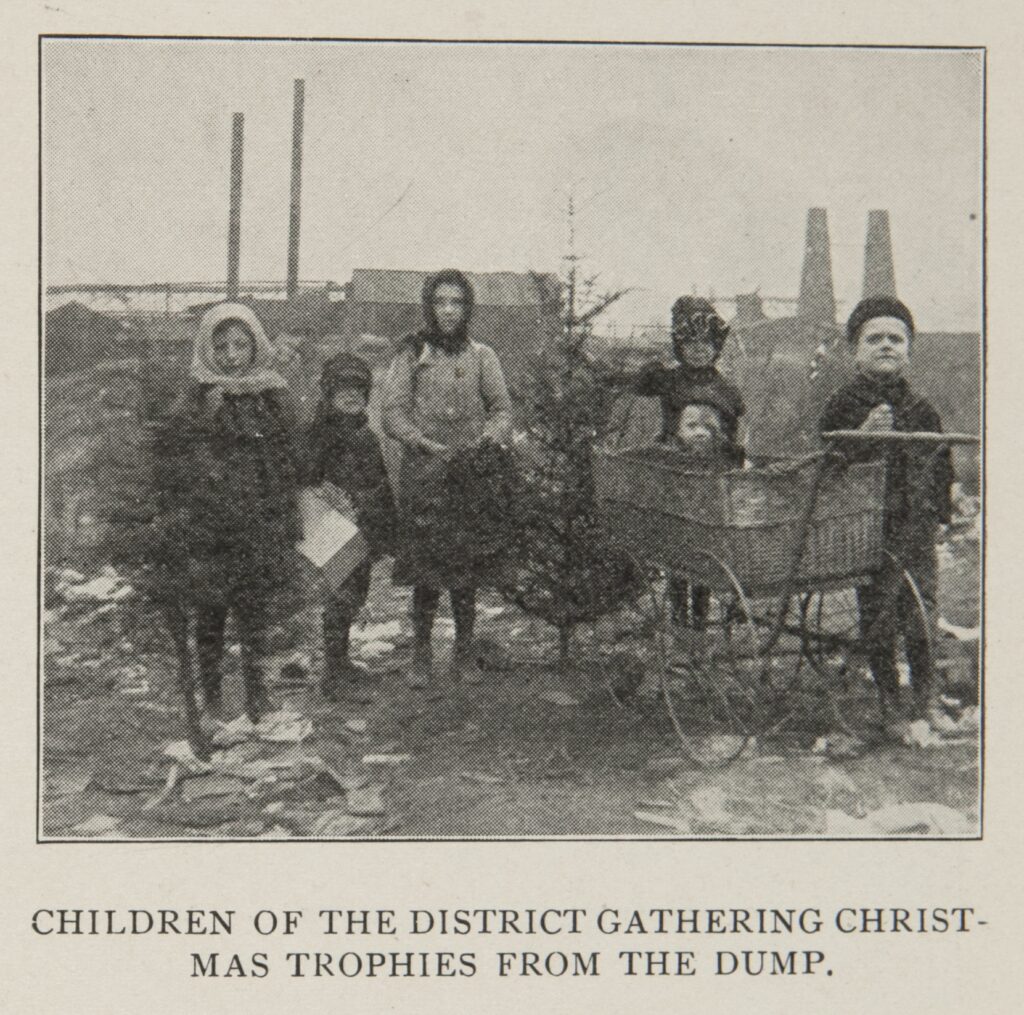

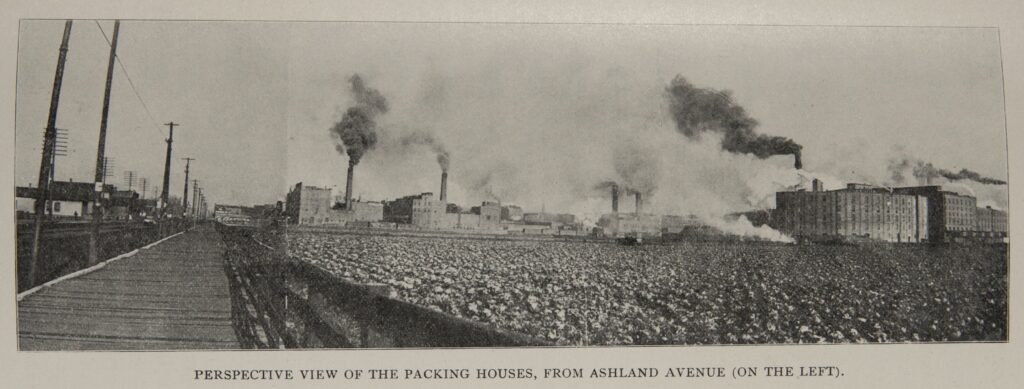

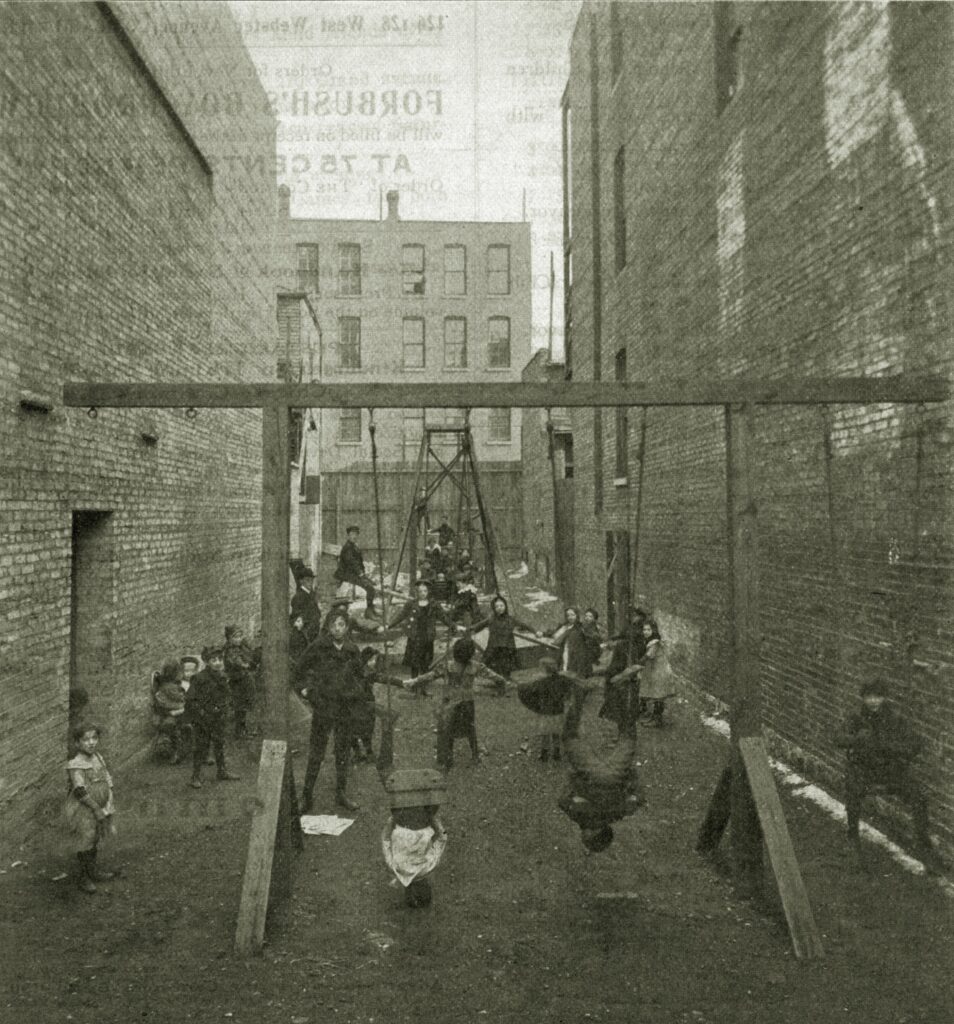

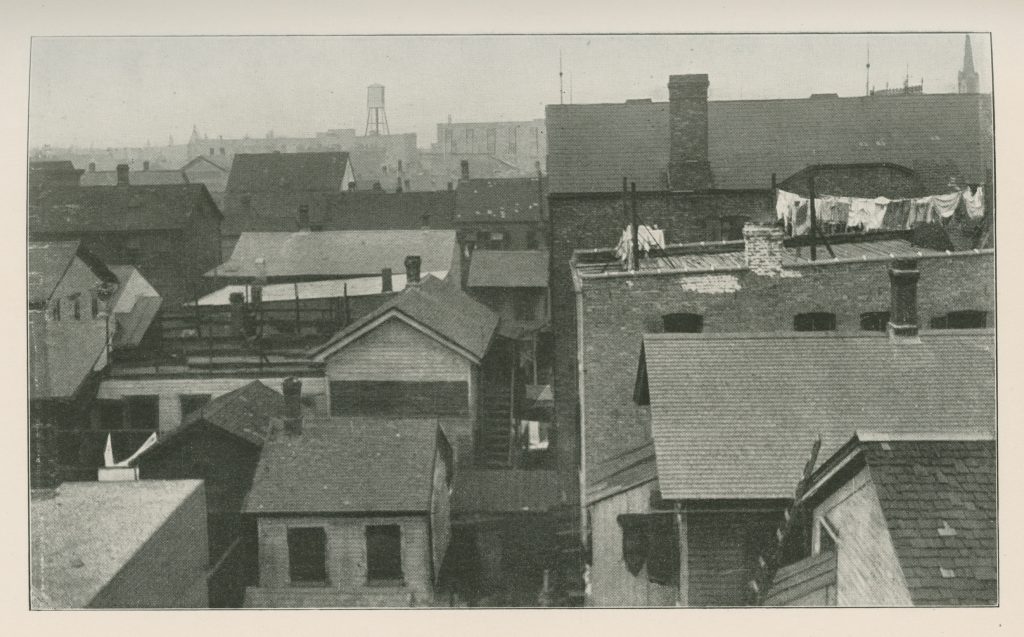

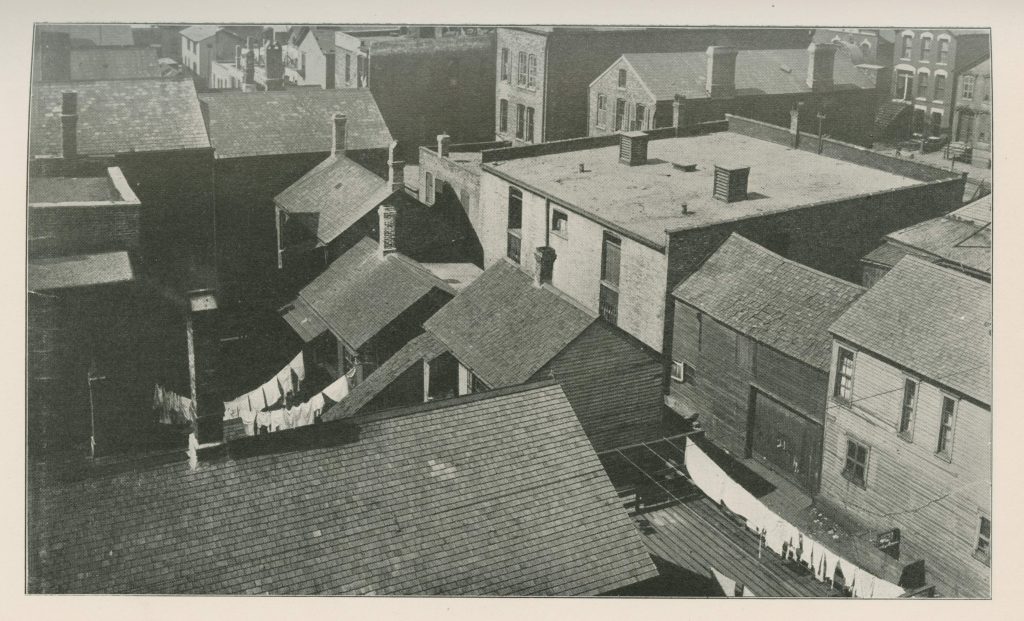

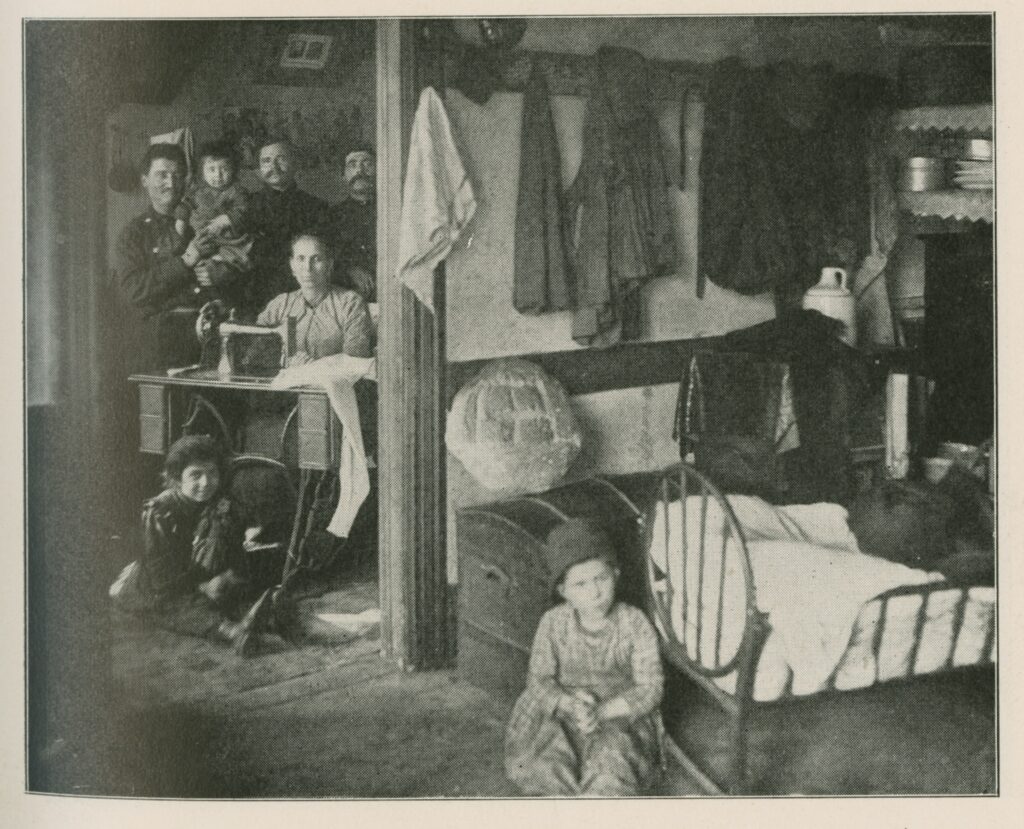

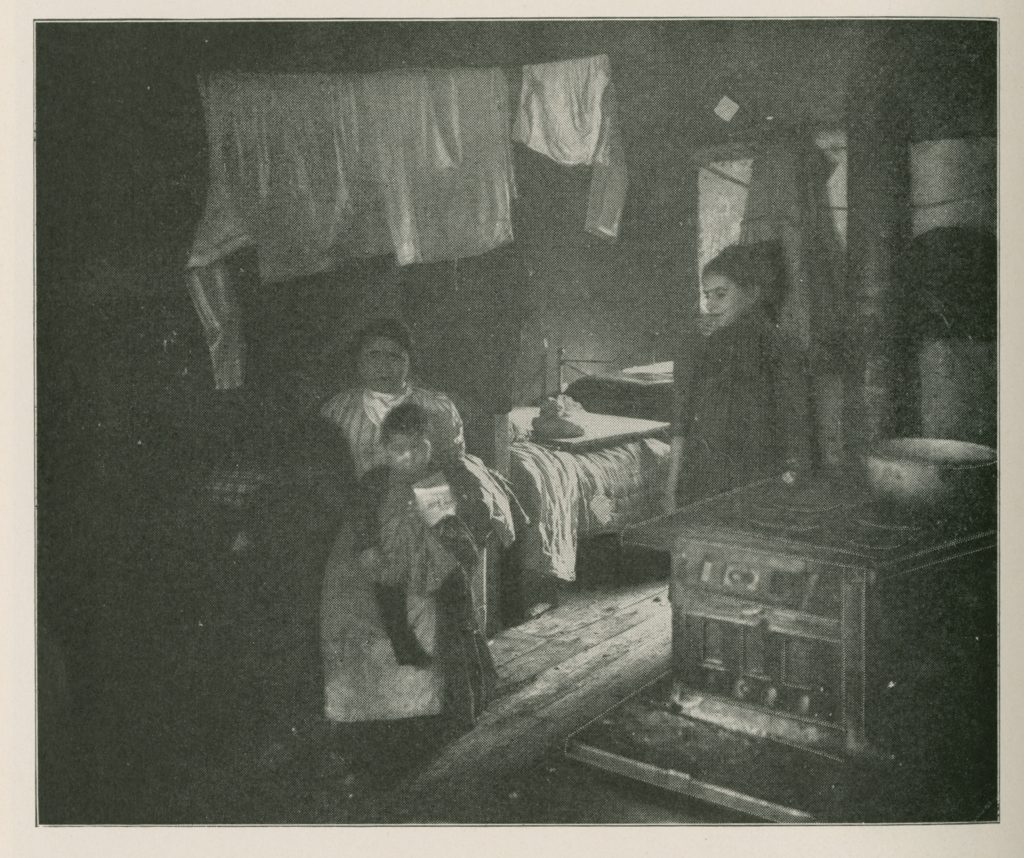

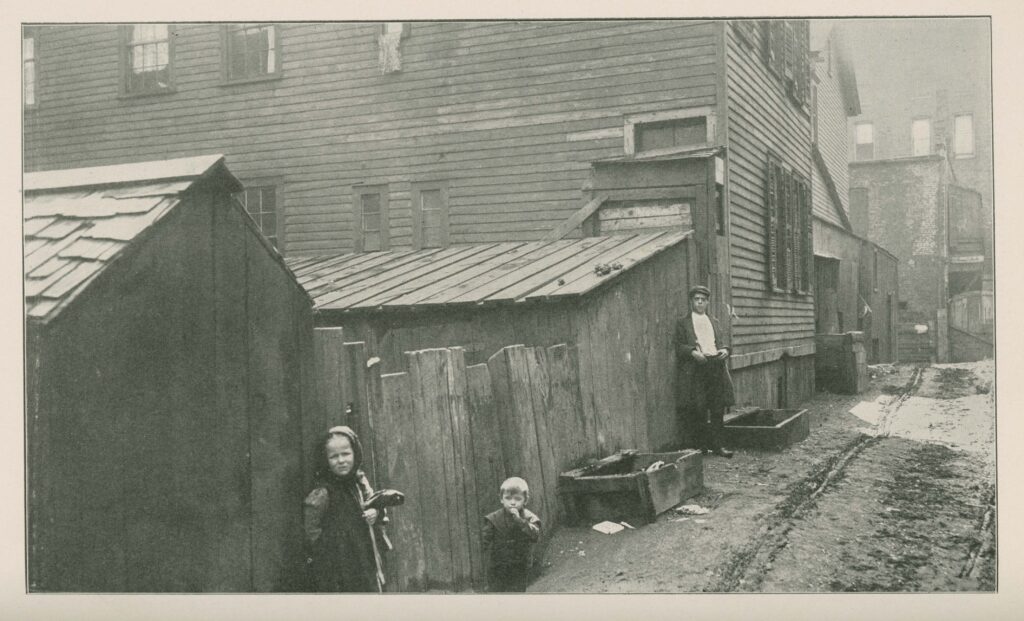

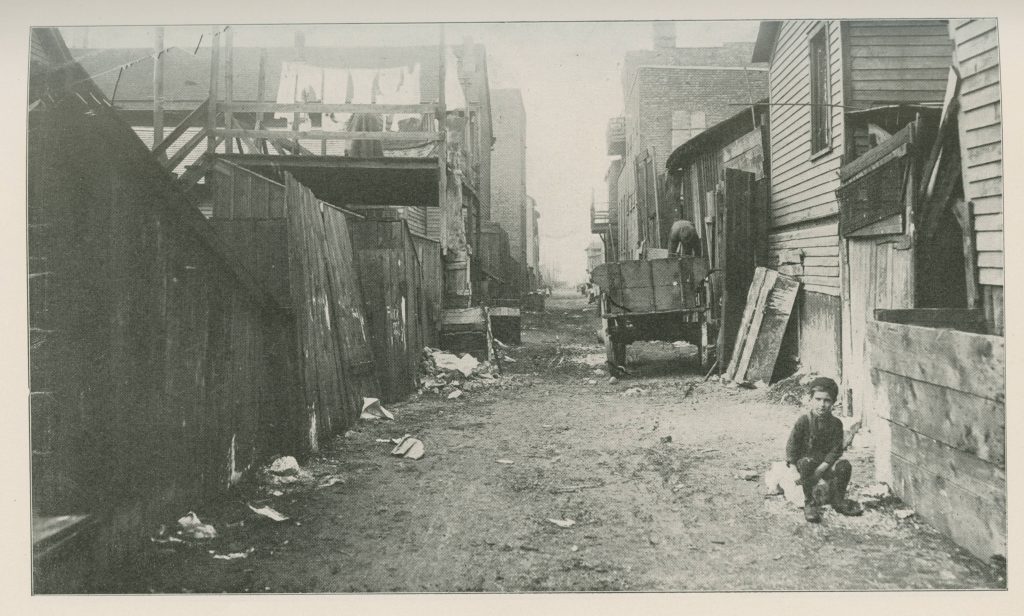

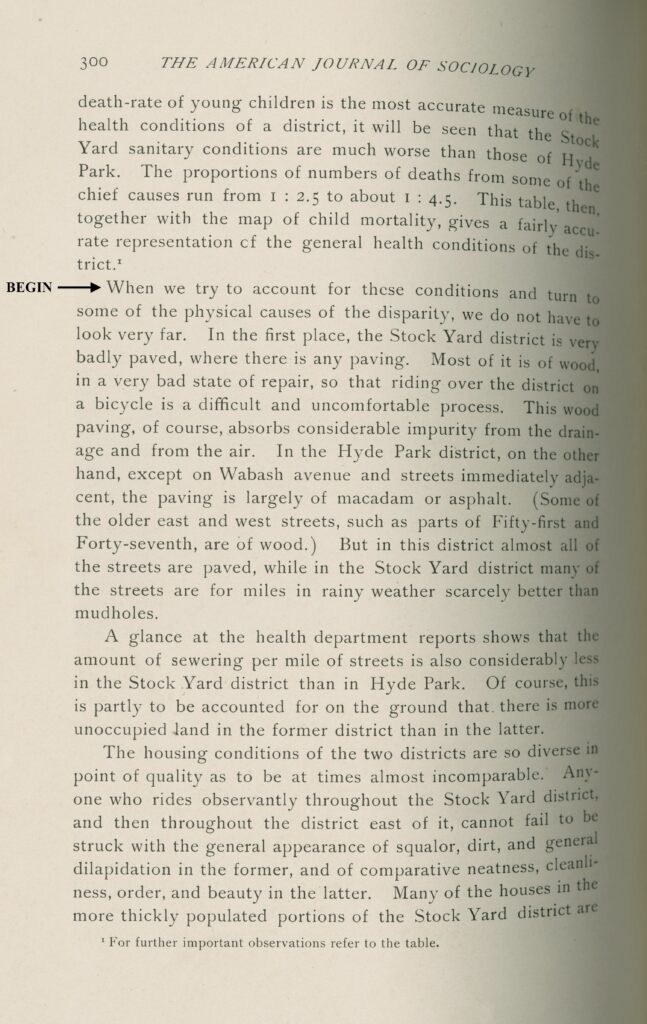

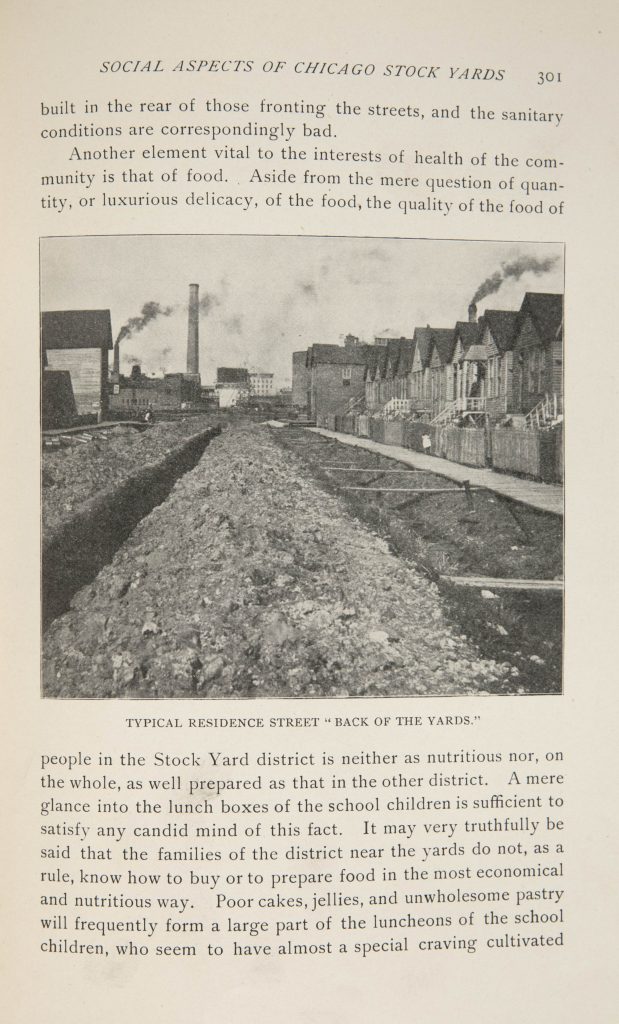

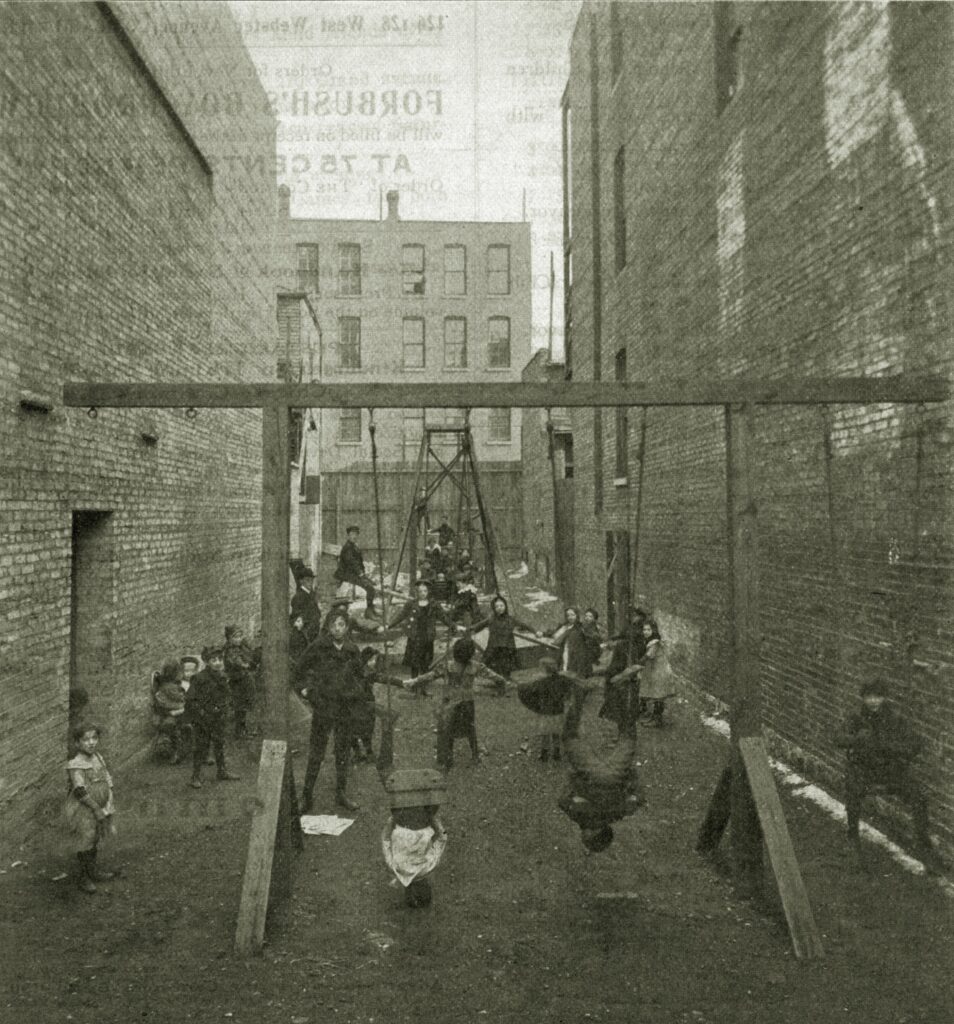

Historian James Barrett writes, “One became aware of Packingtown long before stepping down from the streetcar near the great stone gate of the Union Stockyards. The unique yards smell—a mixture of decaying blood, hair, and organic tissue; fertilizer dust; smoke; and other ingredients—permeated the air of the surrounding neighborhoods.” Turn-of-the-century sociologist Charles J. Bushnell could not capture the smells, perhaps, but his photographs offer visual evidence of the area’s streets and its crowded apartments, or tenements. Robert Hunter documented conditions in tenements in other parts of the city in order to advocate for housing reform. His report focused on other neighborhoods because he considered Back of the Yards housing so bad that it could not fairly represent conditions throughout the city. Read an excerpt here.

City Homes Association and Robert Hunter, Tenement Conditions in Chicago, 27, 28, and 29 (ariel views); 63 and 70 (interiors); and 38, 39, and 167 (street scenes) (1901)

Charles J. Bushnell, Some Social Aspects of the Chicago Stockyards, Chapter II: The Stockyard Community at Chicago” (1901)

Questions to Consider

- How do Bushnell and Hunter portray the streets and tenements of Back of the Yards and other immigrant neighborhoods? What do they identify as these neighborhoods’ greatest hardships?

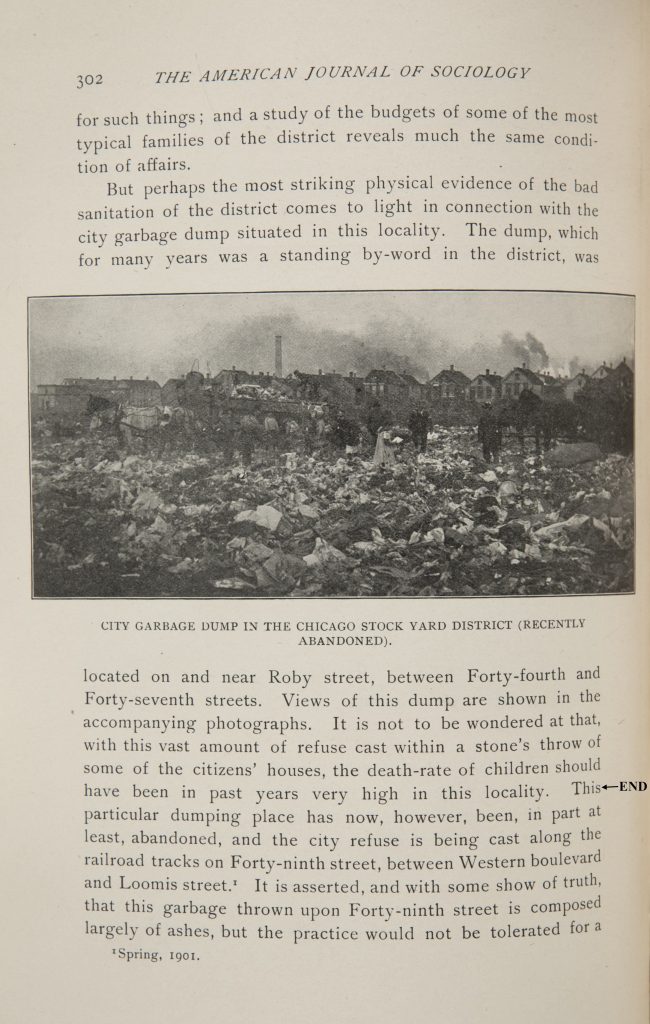

- Describe the people and places portrayed in Bushnell’s and Hunter’s photographs? What activities are they engaged in? How do the people seem to relate to their surroundings?

- Compare these photographs and descriptions to Sinclair’s representations of the neighborhood and people in The Jungle. Do they confirm or contradict each other?

Creating New Urban Communities: Graham Taylor and the Chicago Commons

One of the urban reformers who attempted to improve conditions in Chicago’s poor and working-class neighborhoods was Graham Taylor. Taylor, a Congregational minister, objected to the rising income inequality he witnessed in late nineteenth-century America and, especially, to the hardships experienced by the urban communities in which he worked. Taylor collaborated with Jane Addams and others to develop the settlement-house movement. The movement attempted to redress the widening gulf between the poor and the affluent in America’s cities by bringing middle-class women and men to live in poor neighborhoods and provide services, classes, and organizational support to the people who lived there.

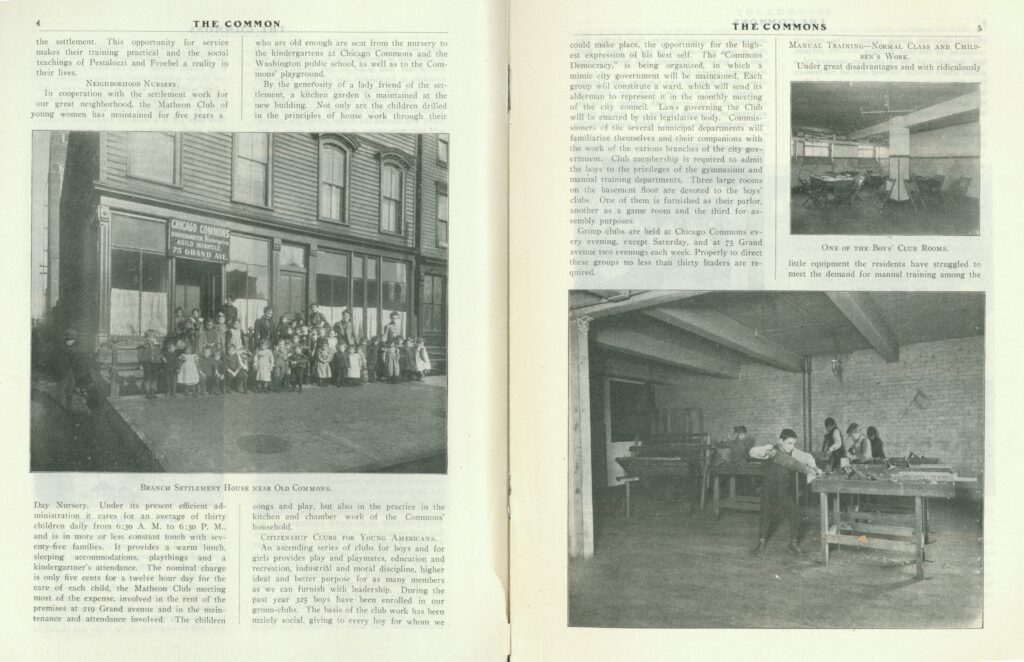

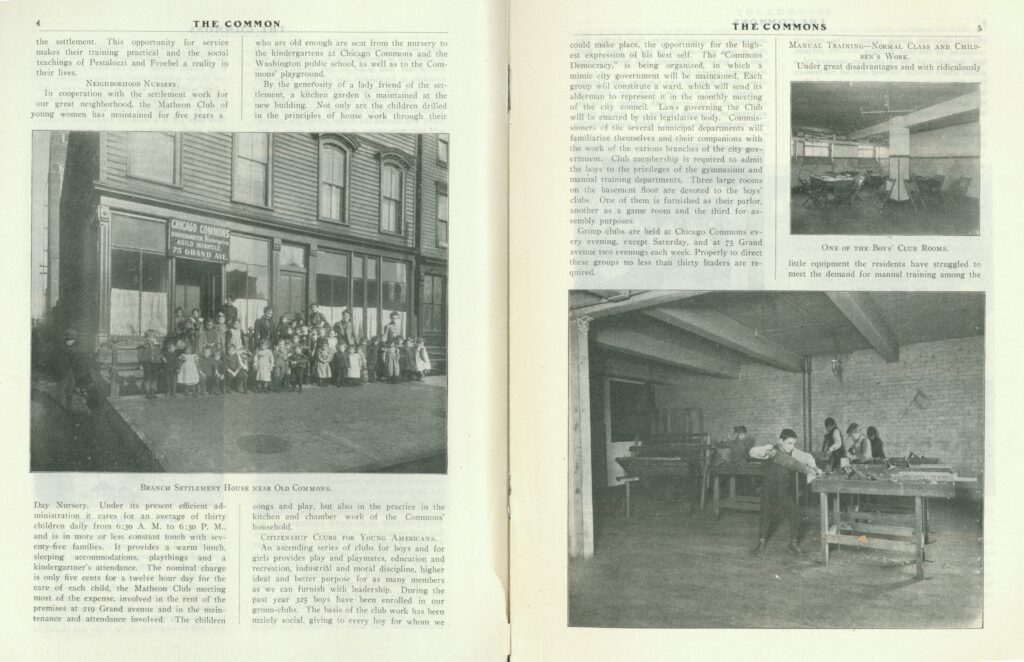

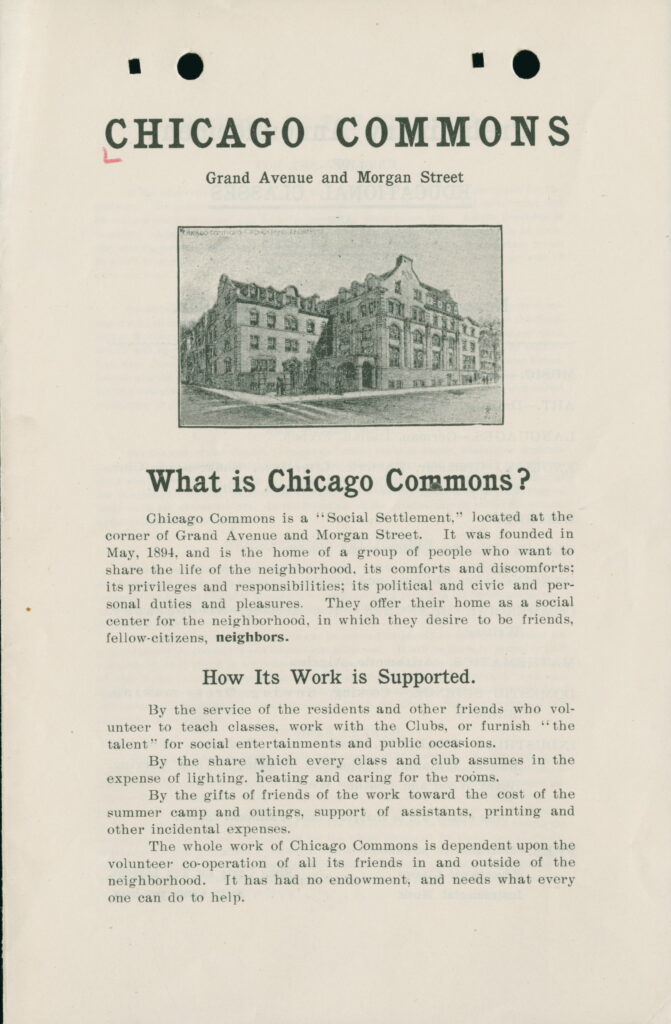

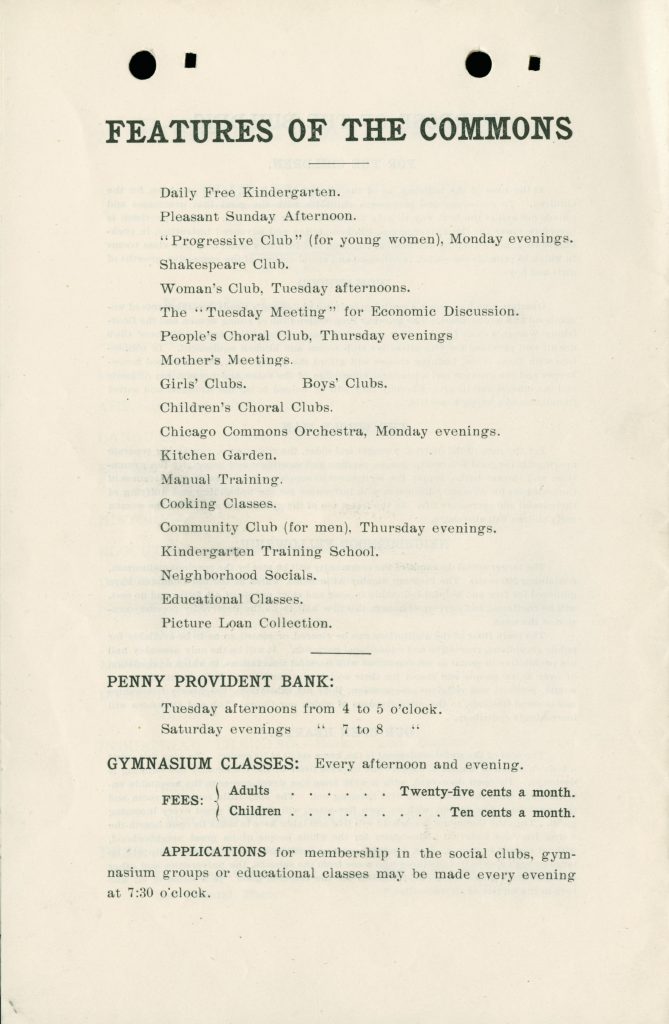

In 1894, the same year that the University of Chicago established a settlement house in the Back of the Yards neighborhood, Taylor opened the Chicago Commons on the city’s Northwest side. The neighborhood was working class, with large populations of Scandinavian, Irish, German, and Italian immigrants. Taylor and his family lived at the Chicago Commons with other Seminary teachers and students. The settlement ran a kindergarten and a day-care center as well as many programs for adults. It was open to all faiths, economic levels, and ethnic groups.

“What is Chicago Commons?” (1901)

Questions to Consider

- Examine the pamphlet, “What is Chicago Commons?” published soon after the opening of a new, larger building. Who does the brochure address? What programs does the settlement offer?

- Based on this document, describe the settlement house’s philosophy. What is the settlement trying to achieve through its programs?

- Do you think that access to a settlement house like this would have made a difference in the lives of Upton Sinclair’s characters in The Jungle, Jurgis Rudkus and his family?

- How do Chicago Commons and other settlement houses compare to the political responses that Sinclair advocates? Which approach do you believe was more effective?

Public Health and Working-Class Communities

Upton Sinclair famously complained that, in writing The Jungle, “I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach.” While he intended to gain support for workers’ rights and the cause of Socialism, the novel’s most tangible political effect was to advance food safety legislation. Even so, the issues were not unrelated. Labor advocates understood that working people suffered both from the dangerous conditions of factories and from unhealthy living conditions, including the food they consumed.

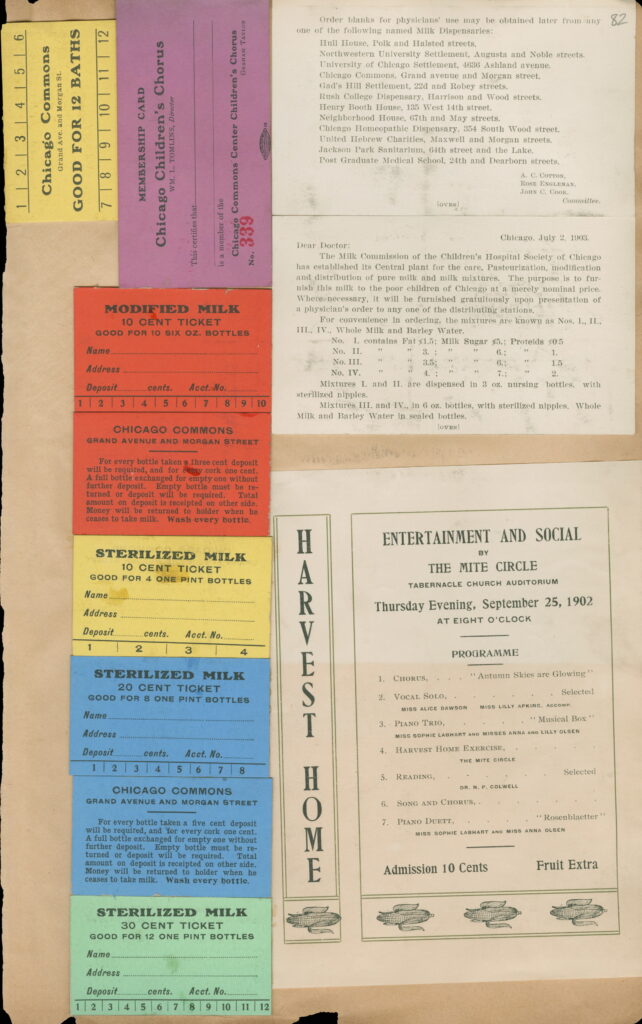

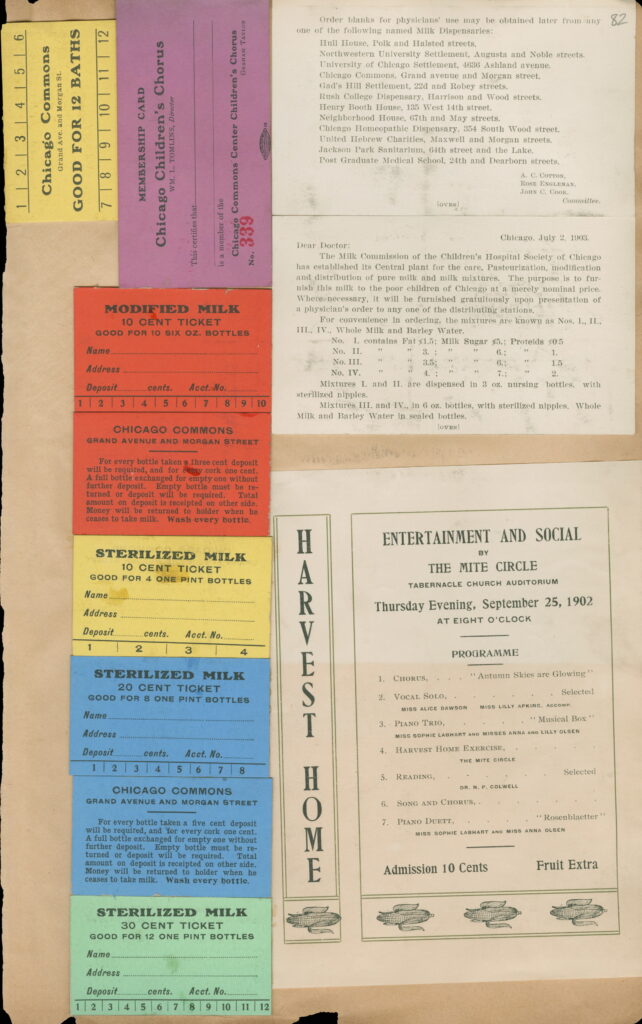

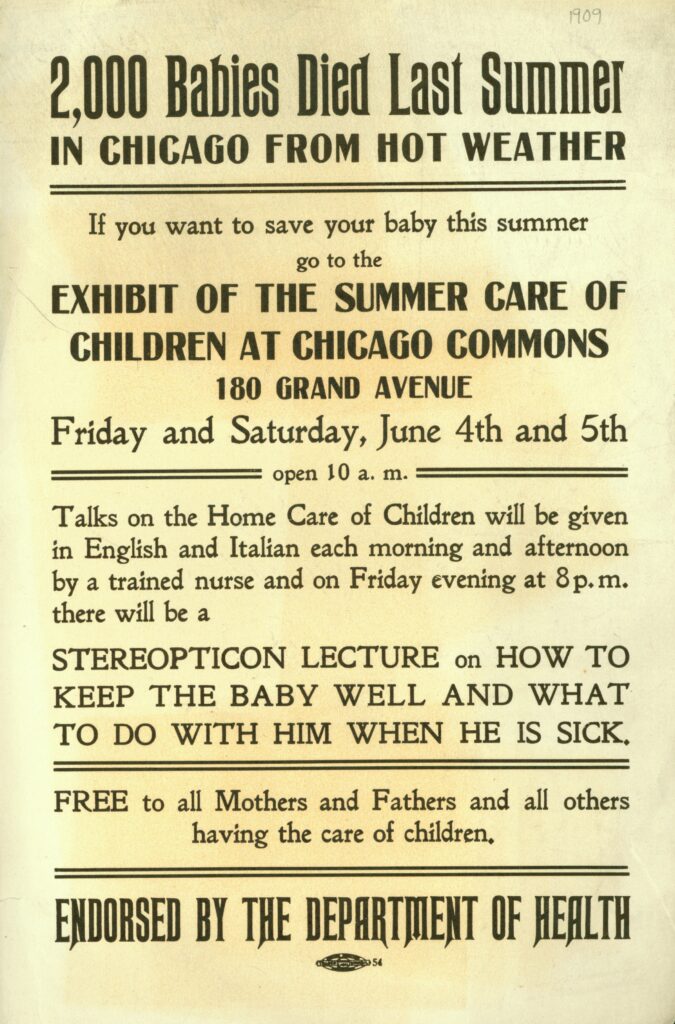

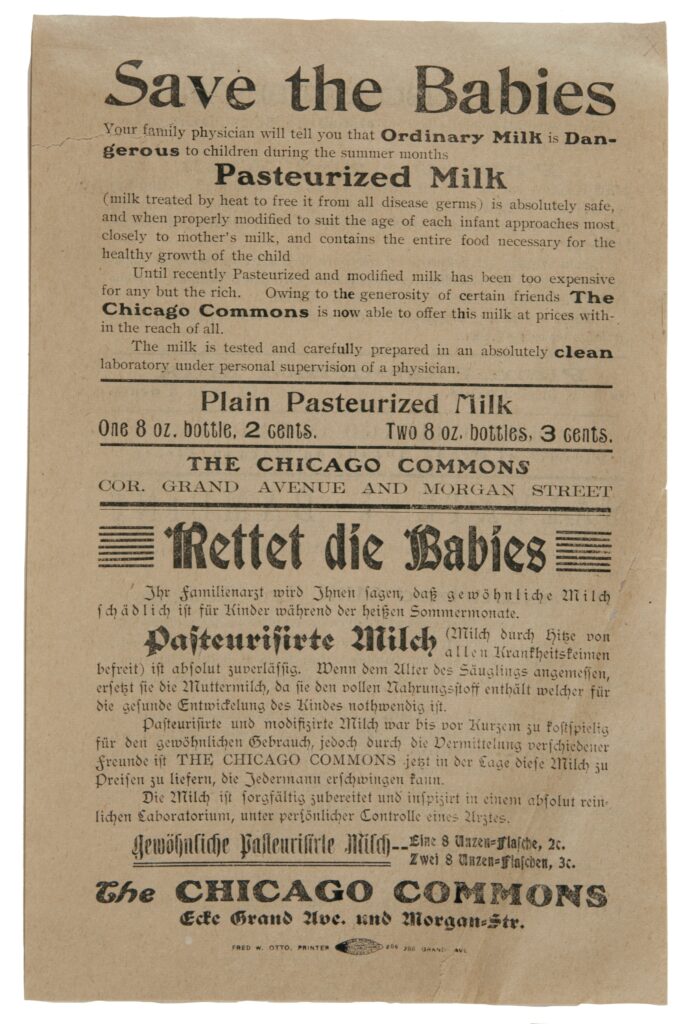

The first three documents in this section suggest some of the ways that workers from the Chicago Commons settlement house promoted public health. As historian Rachel E. Bohlmann explains, “During brutally hot summers, food and milk spoiled quickly, and infants and small children were most vulnerable to death from spoiled milk… To combat the problem, Commons residents collaborated with colleagues at the Northwestern University Settlement, Hull-House, and other similar institutions in the city to offer inexpensive, pasteurized milk to families with young children.”

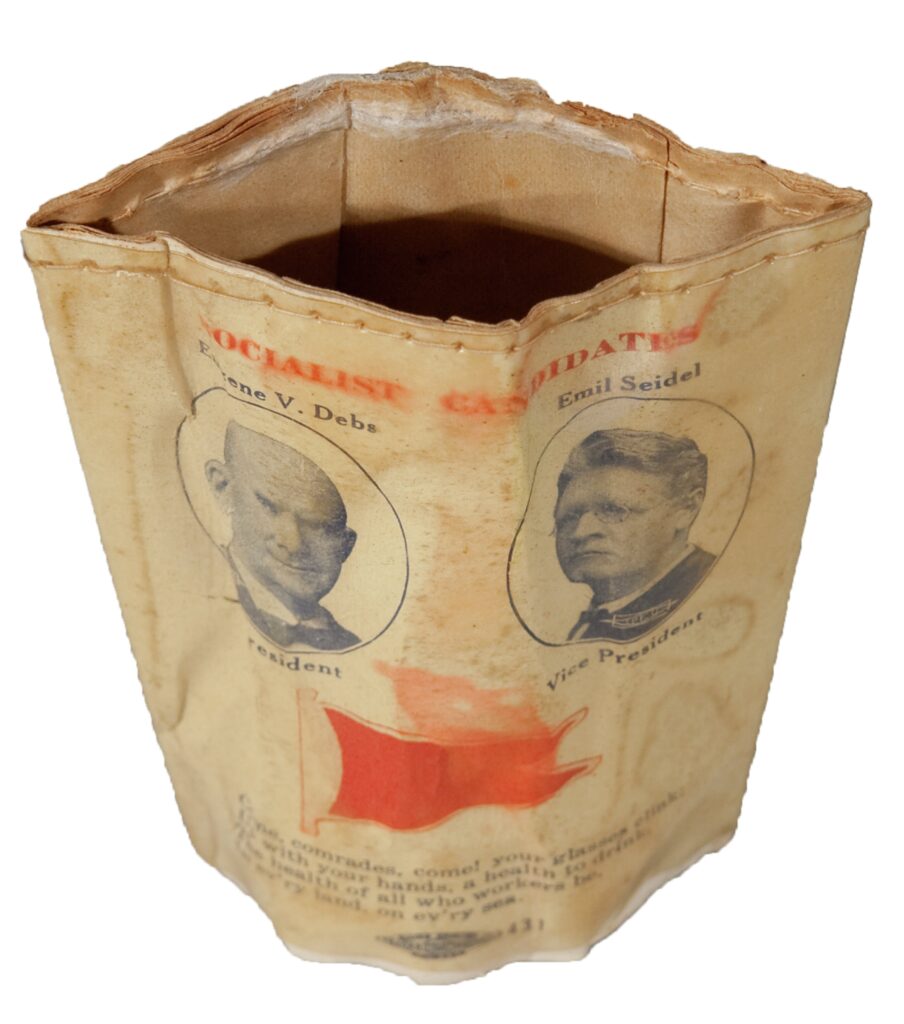

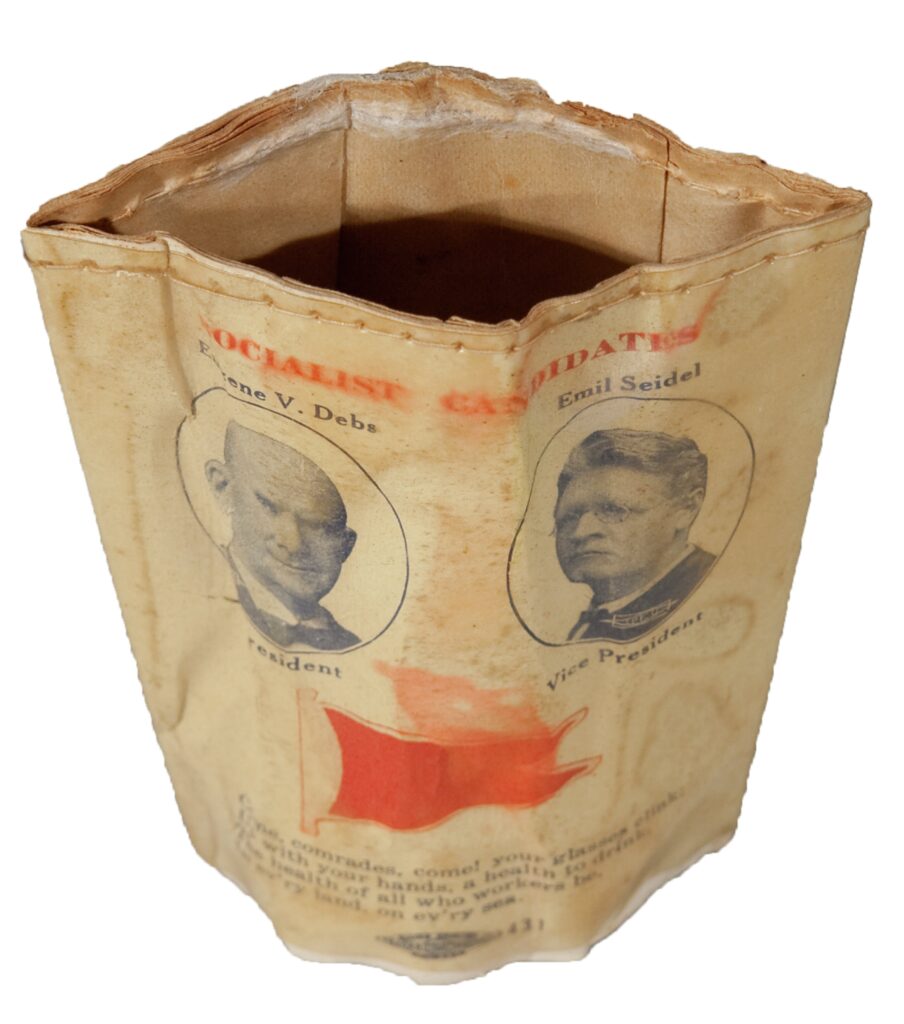

The final document here is a photograph of a novelty item from Socialist candidate Eugene V. Debs’ 1912 presidential campaign. The portable cup features photographs of Debs and his vice-presidential candidate, Emil Seidel, on one side. The reverse side offers the slogan, “A Clean Cup for Clean Politics.” At the start of the twentieth century, shared drinking cups were common in public places, such as saloons, trains, and schools. As scientists developed a better understanding of the role of germs in transmitting disease, reformers began to campaign to end the practice of using communal cups. Socialist Party organizer May Walden proposed these collapsible campaign cups because, she later wrote, “Hygiene was the word.”

Questions to Consider

- Based on these documents from the Chicago Commons safe milk campaign, which communities in Chicago do you think were most vulnerable to illness and death from contaminated milk? Why would some communities be harder hit? What do you think were the obstacles to food safety?

- What do these documents tell you about how settlement house workers organized public health campaigns? How did they reach out to people? What kinds of practices did reformers want to change?

- Think of public health campaigns today. Do they take similar approaches to educating people and changing behavior?

- What is the symbolism of the Socialist Party portable drinking cup? What positive associations between hygiene and Socialism were party members trying to promote by advertising their candidates on drinking cups? Do you see connections between issues of public health and workers’ rights?

Further Reading

Barrett, James R. Work and Community in the Jungle: Chicago’s Packinghouse Workers, 1894–1922. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1987. 25, 67.

Bohlmann, Rachel E. “Pure Milk Campaign Notices from Chicago Commons Scrapbook” and “May Walden, Explanation of Eugene Debs Campaign Novelty Drinking Cup; Debs Campaign Drinking Cup.” In The Newberry 125: Stories of Our Collection. Chicago: Newberry Library, 2012. 78–79, 82–83.

Chicago Historical Society and Newberry Library. Encyclopedia of Chicago. www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org.

Katzman, David M. and William A. Tuttle. Plain Folk: Life Histories of Undistinguished Americans. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1982. 99.

Sinclair, Upton. The Jungle. Introduction by Ronald Gottesman. New York: Penguin, 1985.

Slayton, Robert A. Back of the Yards: The Making of a Local Democracy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986.