Chicago in 1900: An Industrial, Immigrant City with a Strong Baseball Tradition

In the early twentieth century, Chicago, along with a number of other American cities, experienced dramatic social dislocations caused by industrialization, an influx of European immigrants, and the growth and political corruption of industrialized cities. Against this backdrop of social turmoil, a number of white middle-class Americans propagated the idea of sport as a possible antidote to the societal changes plaguing the country. As the country’s sole professional sport, baseball occupied a prominent place in efforts to “Americanize” immigrants.

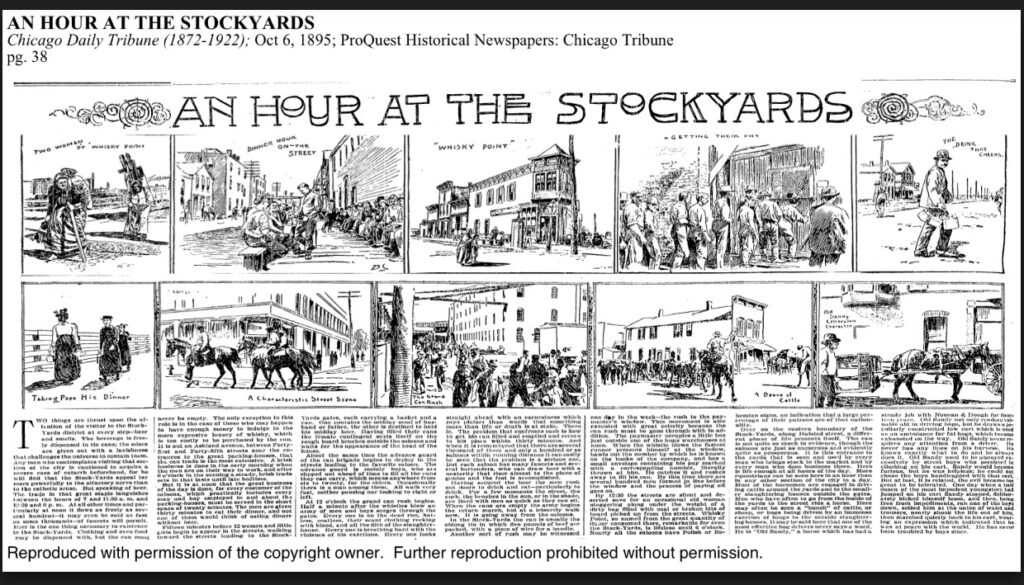

Between 1850 and 1890, Chicago grew from a tiny city of 4400 residents to the nation’s second largest city, sporting a population in excess of 1 million by 1890. By 1900, the city boasted of nearly 1.7 million residents. As rail and water shipping enabled merchants and manufacturers to sell their goods in greatly expanded markets, Chicago’s geographical location enabled it to become a major transportation hub, particularly for the exploding railroad industry. Nearly one-half of Chicago residents over the age of 10 had a job in 1900, including nearly one-quarter of the city’s women. The manufacturing sector of the city’s economy employed nearly 36 percent of the workforce, as Chicagoans found jobs with the railroad, in the steel mills, and in the stockyards. The average worker in one of these industries worked at least 5 ½ days (55-60 hours) per week and could expect to earn between $500 and $600 per year.

Many of these dangerous jobs went to immigrants or their children. By 1900, 8 out of 10 Chicago residents were either foreign born or the children of at least one foreign born parent. Racially, the city was 98 percent white, with a tiny black population of below 2 percent. This small black population lived primarily in 8 of the city’s 35 wards, concentrated on the south and near west sides. Compared with other U.S. cities, Chicago had much higher percentages of both foreign-born residents and residents with at least one foreign-born parent.

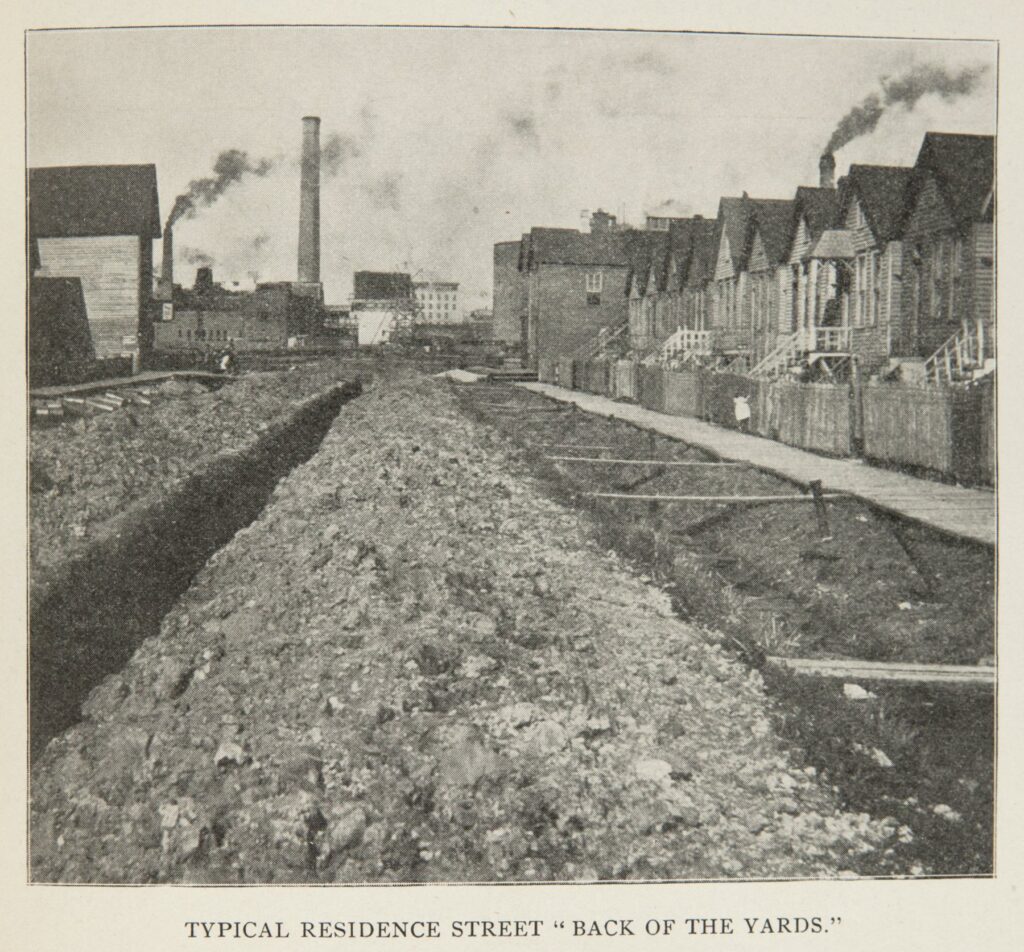

The lives of almost all of these people were devoid of the conveniences we take for granted today. Their wages gave them little disposable income. They would not own an automobile, and their homes would not have electricity, sewer, or water. One historian described working-class neighborhoods thus: “dirt roads without drainage or sanitary hookups, gasoline street lights, piles of garbage and putrid air were all-too-common features of working-class districts in the city of the early twentieth century.” Working-class men and women in 1900 had little time or money for leisure activities.

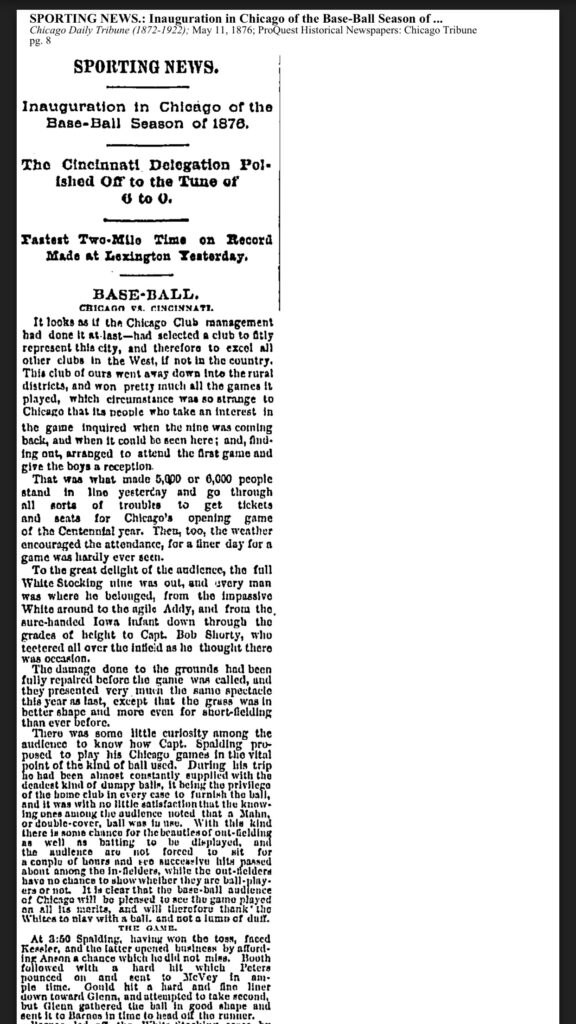

One of the leisure activities some Chicagoans could enjoy was a day at the ballpark. In 1876, William Hulbert, owner of the Chicago White Stockings, provided the impetus for the founding of the National League. Under Hulbert’s leadership, the National League prohibited Sunday baseball, set ticket prices at 50 cents, and prohibited alcohol in ballparks. Historians have argued that Hulbert desired to “cater to the middle-class fan” and discourage working-class fans from attending games. While the other major leagues of the era: the American Association, Union Association, and Player’s League, all scheduled Sunday games, in the National, the Sunday prohibition continued until 1892, when teams in Cincinnati, Louisville and St. Louis, the latter two joining the National League that year from the American Association, began playing on the Christian Sabbath. The first season of Sunday baseball in Cincinnati resulted in the club more than doubling its 1891 attendance. When the National League admitted 4 American Association clubs in 1892, it relaxed its rules on alcohol on Sunday baseball for those 4 teams. In the words of one historian, “by the end of the decade, those looser moral practices had spread to the other National League clubs, where inebriation in the seats became a more common sight.”

In Chicago, with high admission prices and no baseball games to attend on their only day off, not many working-class residents attended games early on, although they may have followed the club. The team did not play on Sunday until 1893, and attendance that year, as it had in Cincinnati the previous year, more than doubled. It seems reasonable to infer that some of that increase is attributable to the attendance of working-class fans. Overall, between 1876 and 1900, the team’s attendance exceeded the league average in all but two years, cresting at 424,352 in 1898, an average of 5,584 per game. Clearly, the club was a financial success.

Questions to Consider:

- Why did Chicago have a higher immigrant population than other U.S. cities?

- How did daily life in 1900 compare with daily life today?

- How would the ballpark experience of 1880 differ from the experience today?

- In the October 6, 1895 Tribune article on the stockyards, what is the author’s attitude toward working-class Chicagoans? Toward immigrant workers?

Chicago, 1901-10: “Americanizing” the Immigrants, Poor Children Playing in the Alleys

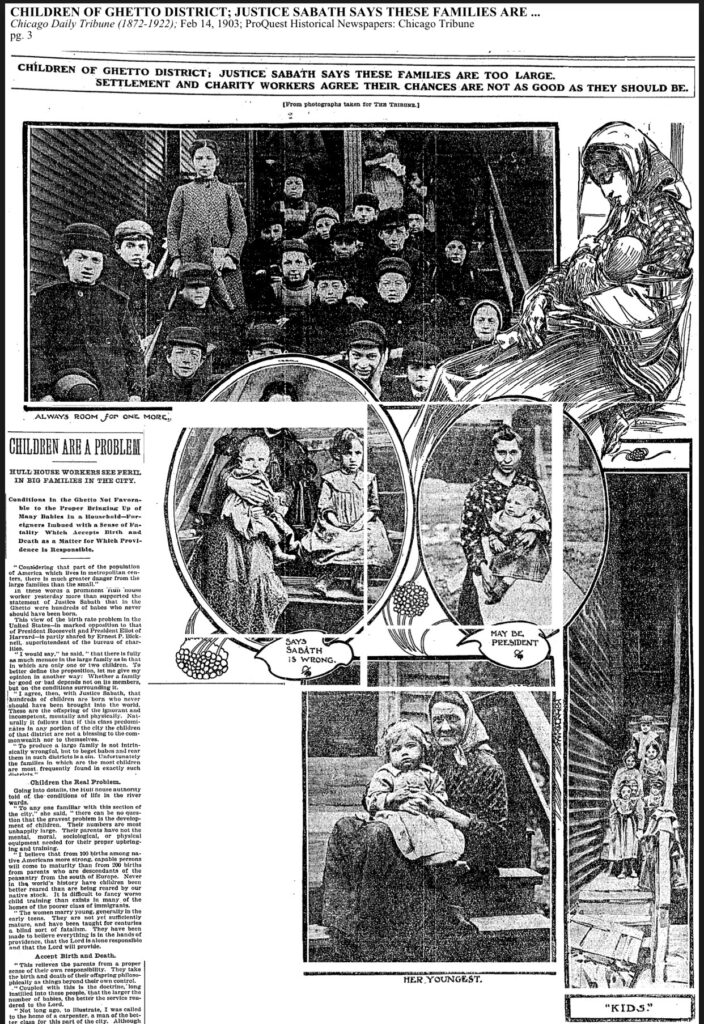

Social turmoil and dramatic changes marked the years 1901-10. Nationwide, immigration to the United States peaked at nearly 9 million. By 1910, nearly 13.5 million people residing in the United States had been born outside the country, with nearly 12 million coming from Europe. The number of foreign born persons from places like Italy, Hungary, Poland, and Russia increased dramatically, nearly tripling from 1.4 million to nearly 4 million between 1900 and 1910.

Many of these immigrants settled in Northern and Midwestern industrial cities in the United States. They worked at a variety of unskilled, dangerous, sometimes deadly, jobs. They came from Europe poor, speaking little or no English, and many practiced Catholicism or Judaism. Their growing presence in American cities caused dismay among the native-born population, particularly the white, Protestant residents of cities with growing immigrant populations. The response to the perceived crisis these immigrants created came in the form of Progressivism, a spate of reforms designed to ameliorate the worst effects of industrialization and immigration. Included among these reforms were efforts to “Americanize” these new arrivals, to curb their perceived excessive drinking, and to address the urban political corruption they made possible. The ultimate goal of these reformers was the “assimilation” of these new arrivals into U.S. society and culture.

The first decade of the twentieth century also saw the emergence of “muckraking” journalism, investigative reports seeking to expose monopolistic corporate practices, urban political corruption, and the ghastly living and working conditions endured by the urban poor and industrial workers. Prominent among these “muckrakers” were Ida Tarbell, who exposed the corporate practices of Standard Oil, Ray Stannard Baker, who investigated coal mining conditions, Lincoln Steffens, who focused on urban political corruption, Jacob Riis, who detailed the urban poor’s horrific living conditions, and Sinclair Lewis, whose novel The Jungle resulted in a Congressional investigation and subsequent action to address unsanitary and unsafe conditions in the meatpacking industry, centered in Chicago.

Chicago experienced all the social stresses of that era. In the city’s poorest neighborhoods, overcrowding and unsanitary conditions led to disease and death. Reportedly, families lived in alleys, particularly in “Little Italy” and “Little Poland,” children played in those same alleys, and mothers neglected their children because they had to take in work to avoid starvation for their families. Drinking in saloons by the men in these families led to domestic squabbles and often to spousal or child abuse. Violence plagued the neighborhoods.

Of course, not all Chicago residents lived in squalor. The city’s middle class of white collar and professional workers, along with working-class residents in skilled trades, lived in a very different world. Electricity became more widely available in the city, enabling some to light their homes and use early labor-saving appliances. In 1900, there were only 20,000 electric customers in the city, mostly businesses. By 1908, more than 31,000 residential customers—most in luxury apartments, affluent neighborhoods, and some middle-class homes—experienced the wonders of electric power. Increasingly, some better-off city residents also enjoyed the luxury of water and sewer hook-ups.

In 1910, nearly1 million Chicago residents over the age of 10 worked, with 42 percent of those workers employed in the manufacturing and mechanical sector. The three largest skilled occupations were machinists, carpenters and painters, logical given the city’s increasing population. The largest white collar occupations included clerks, retail dealers, salesmen, bookkeepers and accountants. The city also boasted a significant professional class; including clergymen, lawyers, and physicians. At the bottom of the occupational ladder were the more than 150,000 unskilled laborers working in a variety of Chicago industries. Nearly 30 percent of the city’s female population over the age of 10 also worked. The vast majority of Chicago’s women worked in five sectors: domestic pursuits/service, the clothing industry, the retail industry, as teachers, or as clerks/cashiers/typists in a range of businesses. Some 20,000 Chicago women worked in professional occupations; nearly 43 percent of those women worked as teachers. By 1909, the average salaried worker in Chicago’s manufacturing sector earned an average of $1047 a year, nearly twice the $592 yearly salary for a wage-earner.

Over 27,000 of Chicago’s African American population over the age of 10 worked. African American men found jobs as janitors, laborers, porters, servants, and waiters. Women worked primarily as dressmakers, servants, or laundresses. A small group of professionals included physicians, lawyers, and clergymen, with the largest segment of African American professionals working as musicians or music teachers. Although a small number of men and women found jobs as clerks or typists, Chicago’s white collar jobs went to whites.

While residential racial segregation kept the city’s African American population confined to a handful of wards, mostly on the south side, the growing immigrant population presented problems Chicago’s white residents were determined to address.

Questions to Consider:

- How does the composition of Chicago’s population today compare to its population in 1901-10?

- How do the jobs a person could expect to find in 1910 compare to the jobs available today?

- How do the conveniences of daily life today compare with those available to Chicagoans in 1910?

- How do contemporary descriptions of working-class and middle-class life in that era compare?

Chicago Baseball 1901-10: An Age of Championships. Baseball and American Values

In 1901, the American League joined the established the National League to create the two league structure that has endured to this day. After a period of teams raiding the rosters of other teams for players, the sport stabilized in 1903. That year, by informal agreement, the Boston Pilgrims and Pittsburgh Pirates met in the first World Series. After the New York Giants refused to play the Philadelphia Athletics for the “world championship” in 1904, the two leagues formalized the post-season championship series, which began in 1905. Until 1953, the sixteen major league teams remained in the same cities they occupied in 1903.

Between 1901 and 1910, play on the field mirrored the sport’s structural stability. The first decade of the twentieth century featured low batting averages, few home runs, little scoring, lots of triples, errors and stolen bases. Part of baseball’s “dead ball” years, strategy in this era emphasized the stolen base and sacrifice to move runners into scoring position. Overall, the decade saw aggregate batting averages around .250 with fewer than 8 runs a game scored by both teams. Home runs were almost non-existent, as major league teams averaged 20 homers a season from 1901 to 1910.

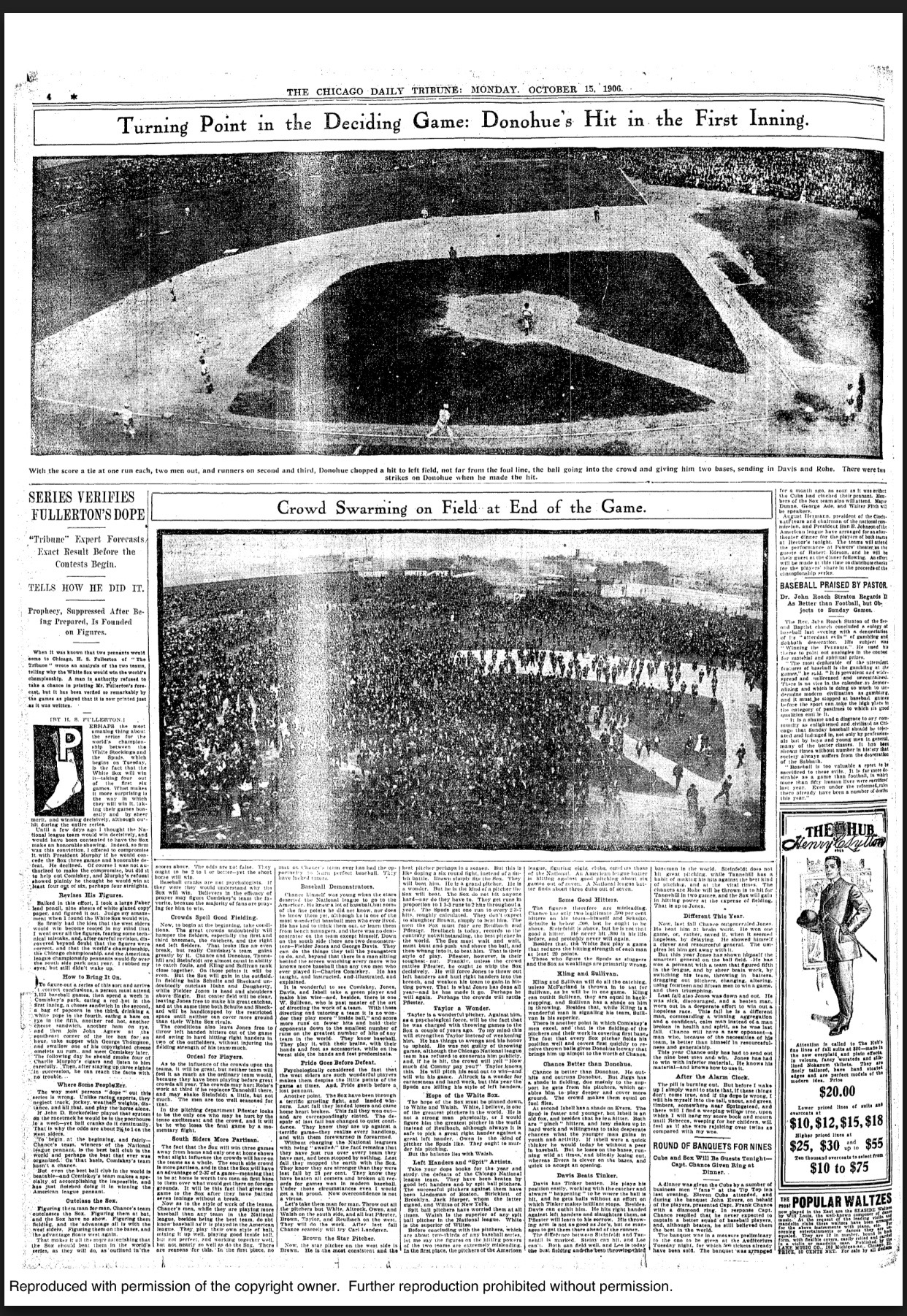

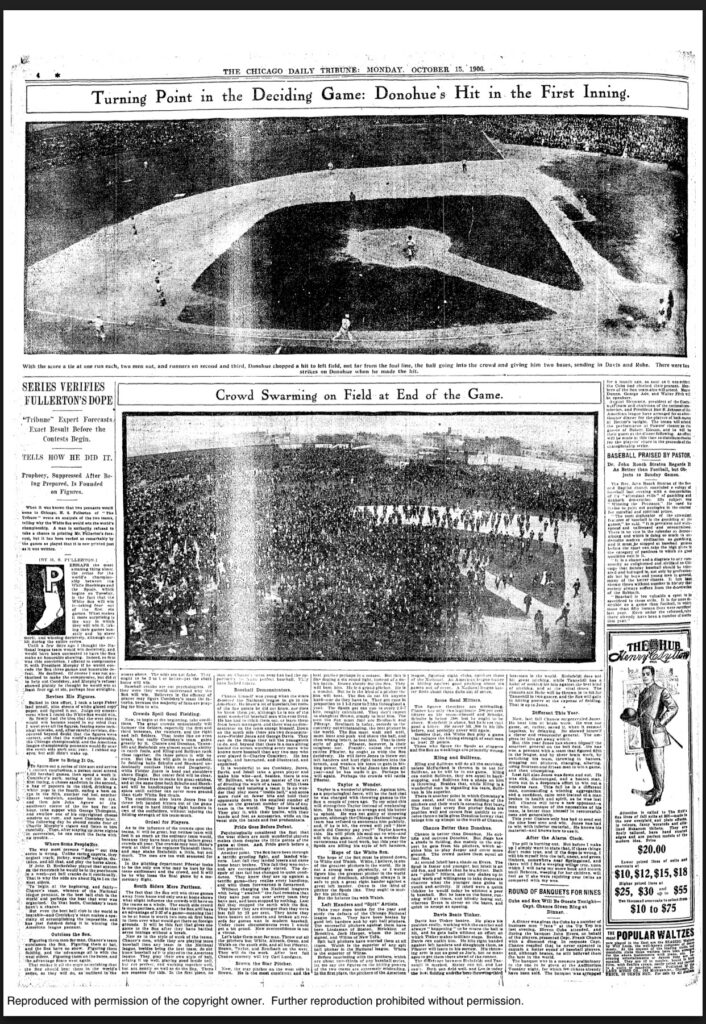

The mid-decade success of the Chicago White Sox demonstrated the unimportance of power hitting in the “inside baseball” era. In 1906, the team won a World Series after hitting .230 with only 7 home runs during the regular season. Two years later, the “hitless wonders” finished only 1.5 games out of first with a team that hit .224 with only 3 homers. In the five seasons from 1906-10, the Sox hit a grand total of 26 home runs yet finished in the first division every year except 1910.

The White Sox 1906 championship over a record-setting Cub team marked the first inter-city World Series in baseball history and began a three season run of success for Chicago teams that made the city the center of the baseball world. The Cubs world championships in 1907 and 1908 gave the city three in a row. During the decade, Chicago teams won pennants in five of the ten seasons, including league championships by the White Sox in 1901 and the Cubs in 1910. No other city won as much.

Beyond the artistic success of the Chicago teams, professional baseball in the city played an important social role in the effort to “Americanize” immigrants. In the early twentieth century, such luminaries as Theodore Roosevelt extolled the value of “manly” sport as a character-building endeavor. Baseball owners, abetted by positive treatment in the news media, advanced the ideology of baseball as an activity that “typified all that was best in our society.” This ideology proposed that baseball would “teach children traditional American values and it would help newcomers assimilate.” As an added bonus, identification with the local team promoted “hometown pride.”

Rooted in a series of myths about its connection to the golden agrarian past, its ability to integrate newcomers into the culture, and the democracy of fans attending games, this ideology taught the importance of sacrificing individual goals for the good of the team, and acceptance of the authority of the umpire. Unfortunately, new immigrants had neither the time nor the money to attend professional games. As had been the case before 1900, owners sought to appeal to middle-class and more affluent city residents. Fans at games might include some respectable women, particularly on Ladies’ Days, but the overwhelming majority of baseball fans were “white collar workers who could afford the expense of going to a game and had the necessary leisure time.”

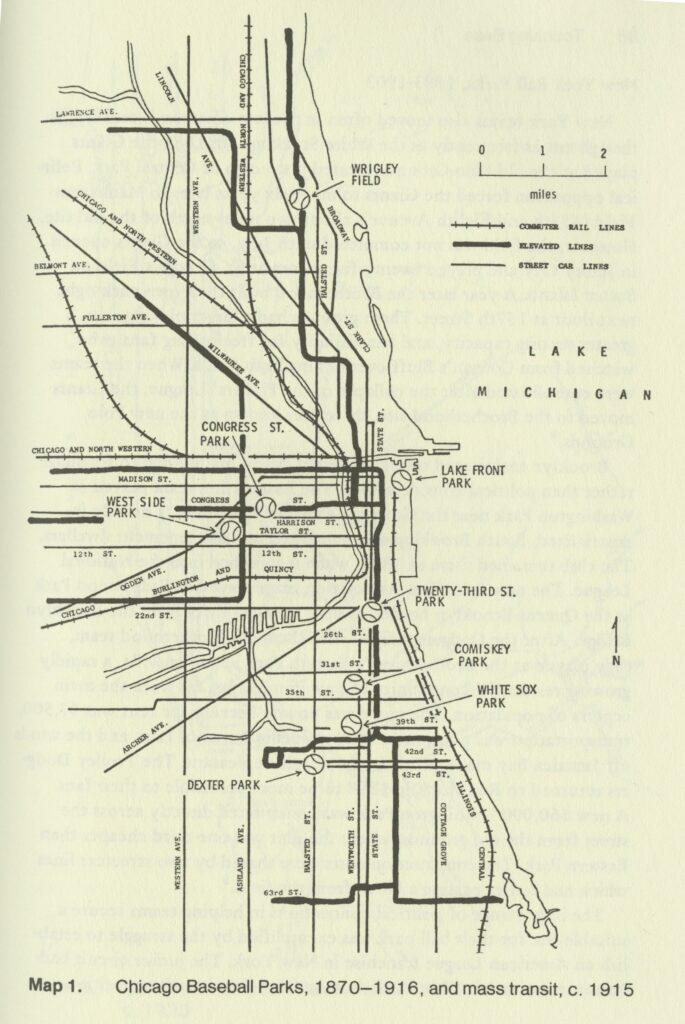

The Cubs played their games at West Side Park, now the site of the UIC medical complex. The neighborhood had a large first and second generation immigrant population, with Russians, Germans, and Irish the largest ethnic groups. The White Sox played first at South Side Park on Pershing Road (then 39th street) between Wentworth and Princeton, then in 1910, opened Comiskey Park four blocks away on 35th Street. The White Sox ballparks were close to the stockyards and the growing African American population west of Wentworth in wards 2, 3, and south of the ballpark in ward 30. Despite their proximity to immigrant working-class and African American neighborhoods, the ballparks attracted few of those residents.

The success of baseball’s efforts to Americanize immigrant residents is impossible to gauge. However, as their children went to school, they developed an interest in the game. Ultimately, cultural and social experiences as these children grew to adulthood Americanized them more effectively than the efforts of either reformers or baseball magnates.

Questions to Consider:

- How does the game on the field in 1901-10 compare to today’s game?

- How does baseball’s early status as an “Americanizing” influence compare with its appeal today?

- How would the ethnic composition of fans in the stands look today compared to fans in 1901-10?

- What does the writer’s attitude toward the German butcher in “The Only Man in Chicago” reveal about the nexus between baseball and Americanization?

Chicago 1911-19: “Americanization” Efforts at Full Force. Segregation and Violence

Between the 1910 and 1920 censuses, Chicago’s population increased by more than 25 percent, to 2.7 million. Nationally, 60 percent of the country’s white population were natives with native-born parents. By comparison, in Chicago, only one-quarter of the white population were native-born with native-born parents. The city was still a city of immigrants. By 1920, nearly 2 million white Chicagoans were either foreign-born, or the children of at least one foreign-born parent. During the decade, large scale European immigration to the U.S. continued through 1914, when World War I virtually shut off the flow of European migration. To fill the void created by the cessation of European immigration, American manufacturers in the northern industrialized cities began to turn to a new source of labor for their factories: migrating southern African Americans. Beginning in 1915, the “Great Migration” reshaped the populations of many U.S. cities. In Chicago, the influx of blacks from the south quickly exhausted the city’s segregated housing available to African Americans, with violent results, particularly in 1919.

Technological advances in industry were reshaping American life. By 1919, due to assembly line production, more than 7.5 million vehicles were registered in the U.S., including nearly 7 million automobiles. Also by 1919, the U.S. mail was being carried by aircraft, which had not existed in 1901. Electricity and indoor plumbing were becoming more available in U.S. urban areas. For example, by 1916, Chicago had nearly 200,000 residential electric customers, about 1/3 of the city’s households. While the city’s less affluent citizens still lived without basic services like water, sewer, and electricity, for middle-class residents, daily life featured these modern necessities.

The first years of the decade in Chicago saw the “assimilation” effort for European immigrants continue at full strength. Settlement Houses and youth clubs in the city assisted immigrants with issues arising in the course of daily life, while recreation and sport introduced children to American games and inculcated them with American sporting values. By the end of 1915, the Americanization effort had become a national movement with the formation of the National Americanization Committee. It urged immigrants to “Learn English, attend night school, and become a citizen.” In Chicago, manufacturers were encouraged to compel non-citizen immigrant workers to “learn something about the language and the government, or make way for other men who will.”

By mid-1915, World War I had raged for nearly a year. Although neutral, the United States benefited from the conflict because of its industrial capacity. Industrial jobs became more plentiful and increasingly difficult to fill, particularly after the American entry into the war in April 1917. Working 48-54 hours per week, wage workers in Chicago saw their yearly earnings rise to around $1250 by 1919, while salaried employees earned about $1800 a year. However, the purchasing power of these wages and salaries barely kept pace with rising prices and inflation.

Of course, World War I convulsed Europe and its devastating effects rippled throughout the world. In late 1918, at the end of the “war to end all wars” a lethal influenza pandemic spread across the globe, infecting an estimated 1/3 of the world’s population and killing at least 20 million people by the end of 1919, including about 670,000 in the United States. An estimated 8,500 Chicagoans died from the disease.

Around 4 million U.S. workers struck against their employers in 1919. These strikes included the Seattle General Strike, the Police Strike in Boston, and the nationwide Steel Strike, which affected steel plants near Chicago. All these strikes proved unsuccessful and along with the hundreds of other strikes in 1919, raised fears of incipient Bolshevism and revolution in the United States and set the stage for the conservatism and nativism of the 1920s.

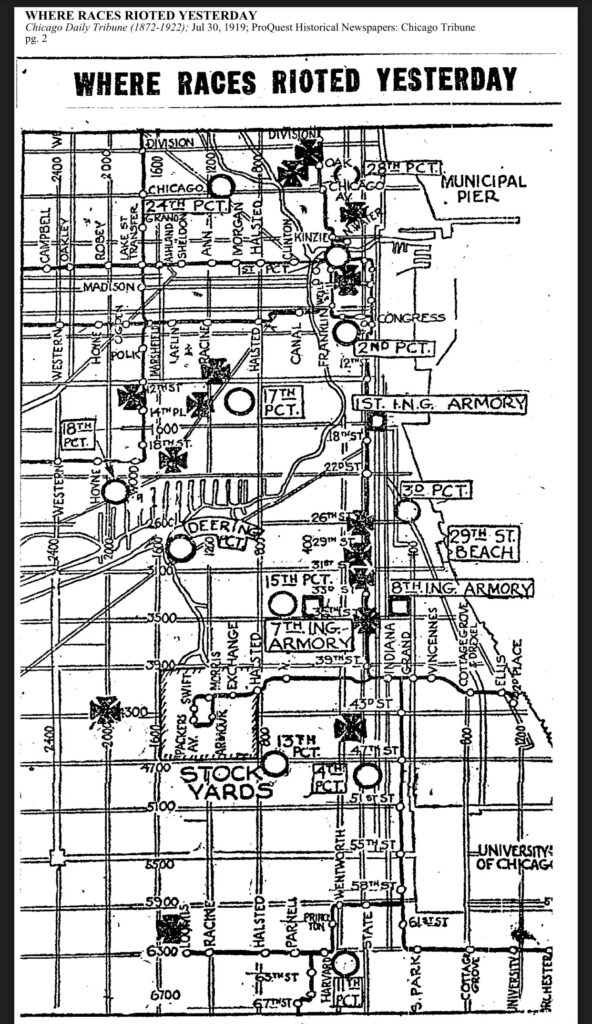

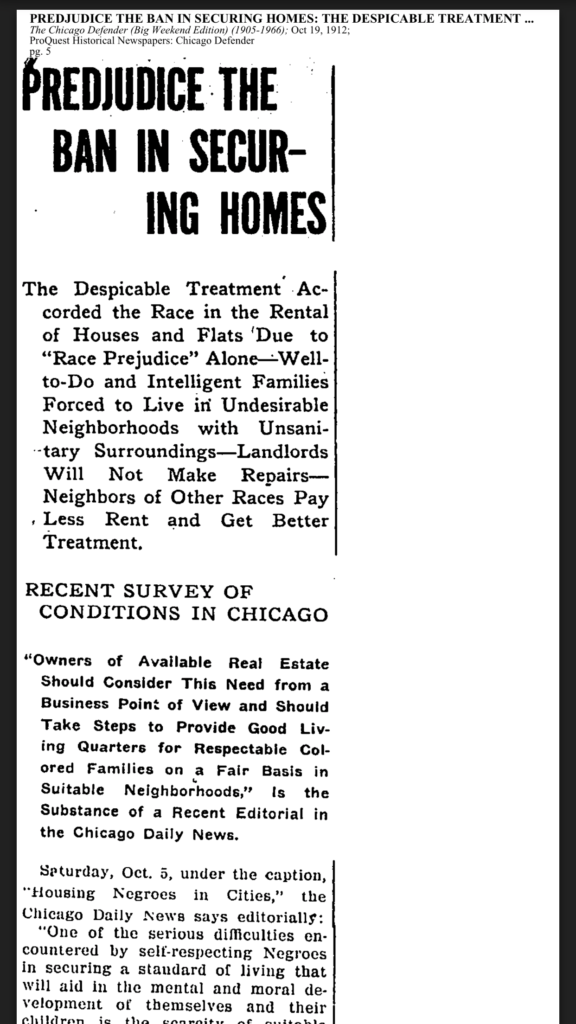

In late July 1919, race riots broke out in Chicago. One of the main causes of the rioting was housing pressure created by the influx of African American laborers migrating to Chicago for wartime jobs. Consigned primarily to sub-standard housing in Chicago’s “black belt,” the 100,000 African Americans living in Chicago by 1919 exceeded the city’s available segregated housing. While African Americans in Chicago demanded “adequate” housing, what was available to them featured “extortionate rents” for overcrowded “old tenements. . . out of repair . . . unsanitary surroundings with poor light and ventilation.”

For a week between July 27 and August 3, 1919, violence raged in the city. At the end of the conflict, 38 persons, 15 whites and 23 blacks, were dead with hundreds more injured. Hundreds of homes had been destroyed. By the end of the year, an uneasy peace obscured continuing problems of adequate employment and housing faced by the city’s growing African American population.

Questions to Consider:

- How do the neighborhoods in today’s city compare with the neighborhoods in 1919?

- How does residential segregation continue to affect the city of Chicago?

- How does the 1919 race riot compare to subsequent major urban civil disturbances in the U.S.?

Chicago Baseball 1911-19: The “Color of a Man’s Skin”

Between 1911 and 1919, Chicago’s two professional baseball teams continued to be relatively successful. Following their 1910 National League championship, the Cubs had five consecutive first division finishes. After two years of fifth-place teams, the club won again in 1918, losing the series to the Boston Red Sox, and bringing their championship total since 1901 to 5 pennants and 2 World Series victories. The White Sox enjoyed more success, with 6 first division finishes and 2 pennants, in 1917 and 1919. The Sox won the World Series for the second time in 1917. The performance of the two teams brought the city’s pennant total to 9 in 19 years and its World Championship count to 4. No major league city had won more league championships.

Fans of baseball during those years would see essentially the same game they had watched from 1901-10. Batting averages rose slightly to around .255, but runs remained just under 8 a game, nearly the same as the earlier era. In home runs, the National League increased its output by 50 percent, each team averaged 30 a year. The American League remained around 20 homers per team per season. Even as the game remained the same, the emergence of “sluggers” foreshadowed what it would become in the 1920s and 1930s.

Between 1901 and 1918, no American League player hit more than 16 home runs in a season. However, in the National League, Fred “Wildfire” Schulte of the Cubs hit 21 home runs in 1911 to set a modern (post 1901) record. Between 1913 and 1915, Clifford “Gavvy” Cravath of the Philadelphia Phillies smashed 62 homers, including a modern record 24 in 1915. Cravath would ultimately win or tie for 6 National League home run titles. Of course, these records were eclipsed by Babe Ruth’s electrifying total of 29 home runs in 1919, a new major league record.

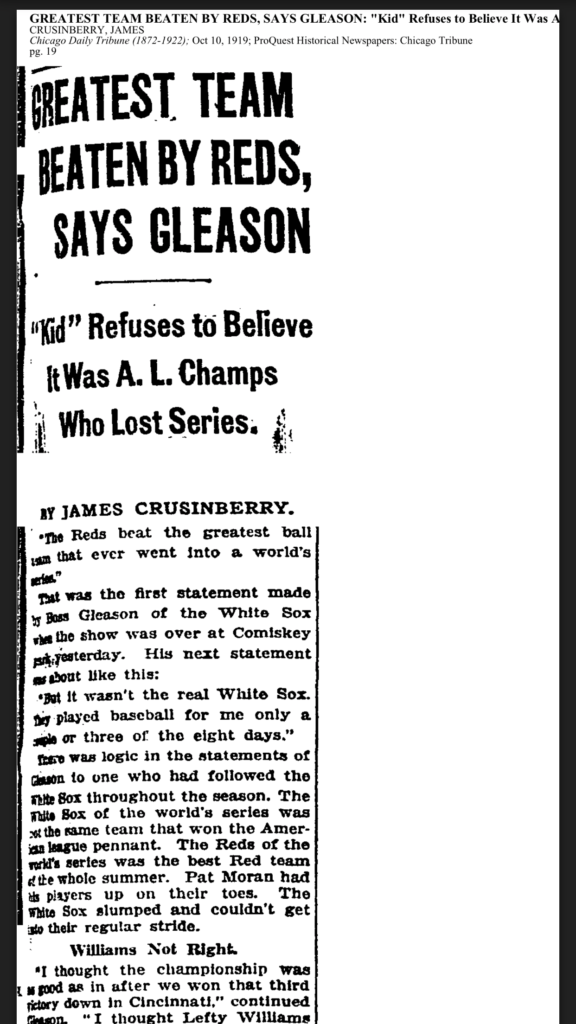

That same season, the Cubs and White Sox were going in different directions. The Cubs failed to defend their 1918 title, finishing third, a distant 21 games behind the champion Cincinnati Reds. The White Sox, however, fielded what many contemporary observers felt was the best team in baseball. The offense, anchored by such stars as Eddie Collins, Happy Felsch, Buck Weaver, Ray Schalk, and Joe Jackson, led the majors in batting average and runs scored. A pitching staff led by Ed Cicotte, Lefty Williams, Dickey Kerr, and Hall-of-Famer Red Faber led the team to a narrow pennant victory over a strong Cleveland team. Although most “experts” felt the team would defeat Cincinnati in the World Series, eight White Sox players conspired to lose the Series to the Reds. Ultimately indicted and acquitted, these 8 were permanently barred from professional baseball in 1920.

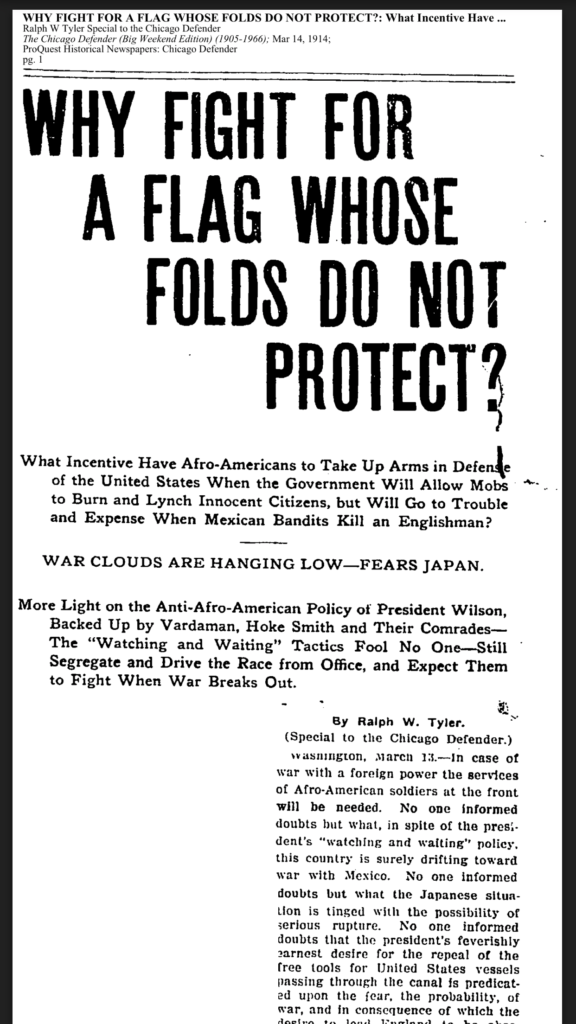

Between 1911 and 1919, baseball continued to play a role in attempts to “Americanize” immigrants, particularly the children of immigrants. Daily newspaper page headers mixed comments like “Baseball Loyalty Springs from the Same Fount as Patriotism,” with their reports of the games. Another encomium to the power of baseball to effect assimilation asserted that “baseball remains . . . (a) growing factor in the friendly democratization of our people.” Naturally, African Americans were excluded from this effort.

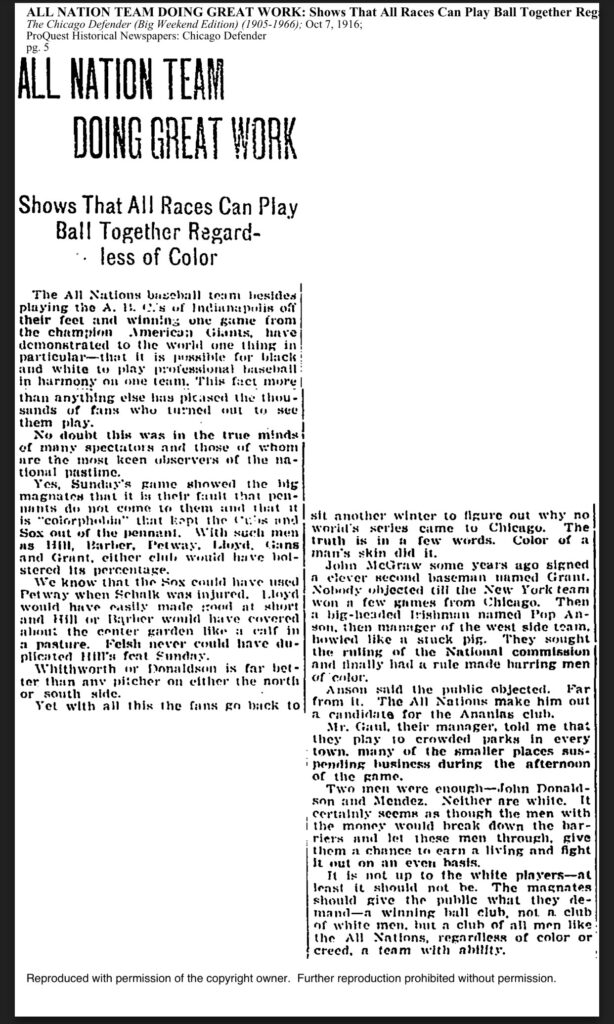

African Americans, barred from white professional baseball, had organized teams in the nineteenth century. By 1919, Chicago had become the center of black baseball in the United States, as Andrew “Rube” Foster in 1911 founded the powerful Chicago American Giants. By 1920, Foster had organized the Negro National League. Acutely aware of the unfairness of the baseball color line, Chicago African Americans excoriated the owners of the Cubs and White Sox for the “colorphobia” that prevented the two teams from winning 1916 league championships. The Chicago Defender reminded the city’s baseball fans that when they contemplated the failures of the 1916 teams, “The truth is in a few words. Color of a man’s skin.”

In 1919, the ethnic and racial fissures that marked the Chicago social relations were reflected in the city’s baseball splits. Although immigrant children likely became baseball fans, their parents had neither the time nor the money for such diversions. For Chicago’s African American population, while some undoubtedly journeyed to the major league parks, they could watch great baseball played by black players at South Side (Schorling) Park, home of the White Sox before their 1910 move to Comiskey Park. In 1919, the Chicago American Giants, playing as an independent team, had a 26-14 record. Hall-of-Famers Oscar Charleston and Cristobal Torriente, a dark-skinned Cuban, played on the team. Charleston hit .406 in 40 games while Torriente batted .324. In 1919, Chicago baseball fans could see great baseball played on the city’s south side.

Questions to Consider:

- How do the ethnic and racial demographics of players on today’s baseball teams compare to players on the field in 1911-19?

- How does the way the game is marketed today compare with its marketing appeals in the nineteen teens?

- How do the pre-1920 “sluggers” compare with today’s power hitters?

- Based on post-series comments, how much do you think the White Sox manager and players suspected their teammates did not give their best in the 1919 World series?

Further Reading

Patrick Mallory, “The Game They All Played: Chicago Baseball, 1876-1906,” Ph.D. diss., Loyola University Chicago, 2013. Available as an open access dissertation.

Steven A. Riess, “Touching Base: Professional Baseball and American Culture in the Progressive Era,” Champaign-Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 1999.