Introduction

In 1941, when Harvard scholar F. O. Matthiessen published American Renaissance: Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman, he defined the canon for the period that many regard as the most important in American literary history. Matthiessen argued that, from 1850 to 1855, five writers developed a distinctively American literature—“a literature for our democracy”—of extraordinary philosophical and aesthetic merit. The writers that Matthiessen chose were Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, and Walt Whitman. The books that he chose include Representative Men, Walden, The Scarlet Letter, Moby-Dick, and Leaves of Grass, most of which still feature prominently on high school and college reading lists. These writers had come to be admired during the nearly 100 years that passed between 1850 and 1941. But Matthiessen was the first to trace their influences on one another, to produce an in-depth study of the 1850–1855 works, and to declare this half-decade a distinct period in American literary history.

How did a handful of writers in New England and New York come to represent the literature of the entire nation?

Matthiessen opened up rich terrain that many critics have explored in the decades since he published American Renaissance. His work also invited numerous questions and challenges, many of them related to the process and effects of forming a canon. Were there no women writers or writers of color who produced works of comparable merit? How did a handful of writers in New England and New York come to represent the literature of the entire nation? What is missed when works are studied in isolation from their historical and cultural context?

The following digital collection explores the wider, literary context for the canonical works of the American Renaissance. Matthiessen acknowledged that none of the works he discussed in his book were widely read at the time of their publication. The selection of texts below provides an introduction to popular literary culture around 1850 and suggests some of the ways that canonical writers engaged that culture.

Essential Questions

- What was the literary context in which canonical American Renaissance writers wrote and published?

- What kinds of literature were popular in the mid-nineteenth-century United States?

- How did now-canonical writers engage or respond to popular literary forms?

Publishing Transcendentalism

Students today may associate mid-nineteenth-century American literature most strongly with Transcendentalism, the philosophy espoused by Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and numerous other New England intellectuals. In works such as Nature and Walden as well as on the lecture circuit, Transcendentalists criticized Americans’ social and religious conformity and materialism. They valued individual intellectual and spiritual growth, or “self-culture,” and located God within the individual soul and within nature. Yet, while these and other ideas became associated with the Transcendentalists, their philosophy was and remains difficult to define. They did not produce a unified doctrine and were, in fact, known to disagree a great deal with each other. They were also notorious for writing and speaking in language that others found unintelligible. Their obscure style and unconventional ideas meant that, even as they developed an influential intellectual movement, Transcendentalists were not popular among nineteenth-century readers and often had trouble getting their works published.

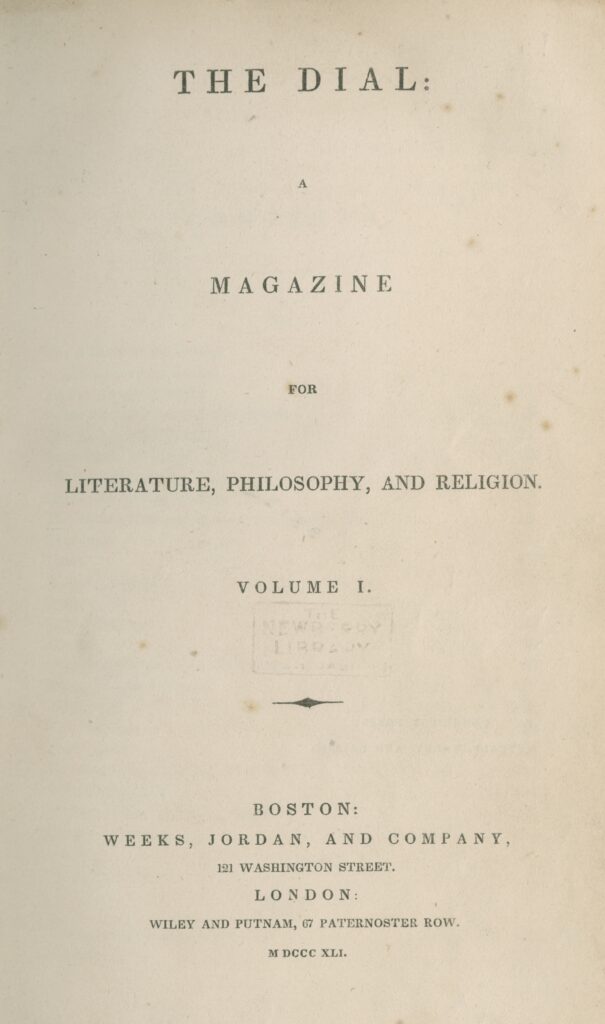

In 1840 Emerson, Margaret Fuller, and George Ripley addressed this situation by founding a journal to promote Transcendentalist thought. It was called The Dial: A Magazine for Literature, Philosophy, and Religion. As Ripley declared in a prospectus that accompanied the first issue, the journal would publish writers committed to “the love of intellectual freedom, and the hope of social progress; who are united by sympathy of spirit, not by agreement in speculation; whose faith is in Divine Providence, rather than in human prescription; whose hearts are more in the future than in the past; and who trust the living soul rather than the dead letter.”

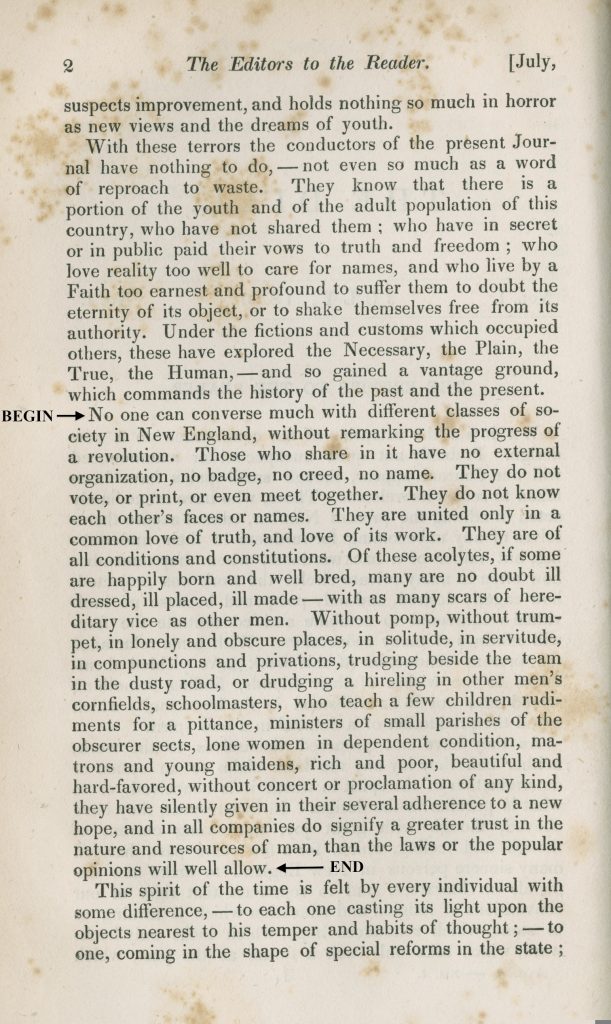

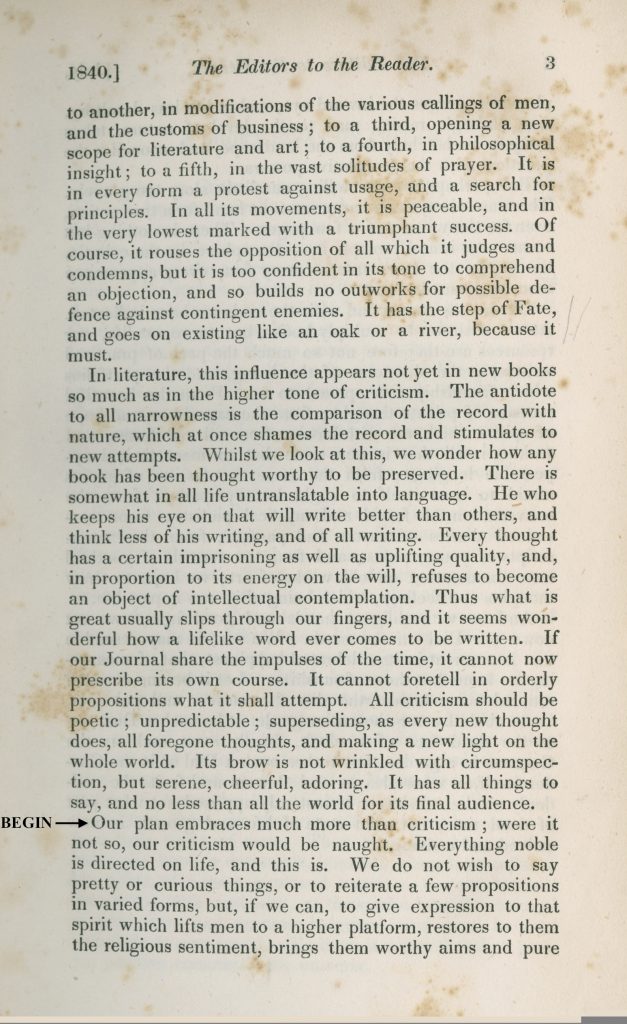

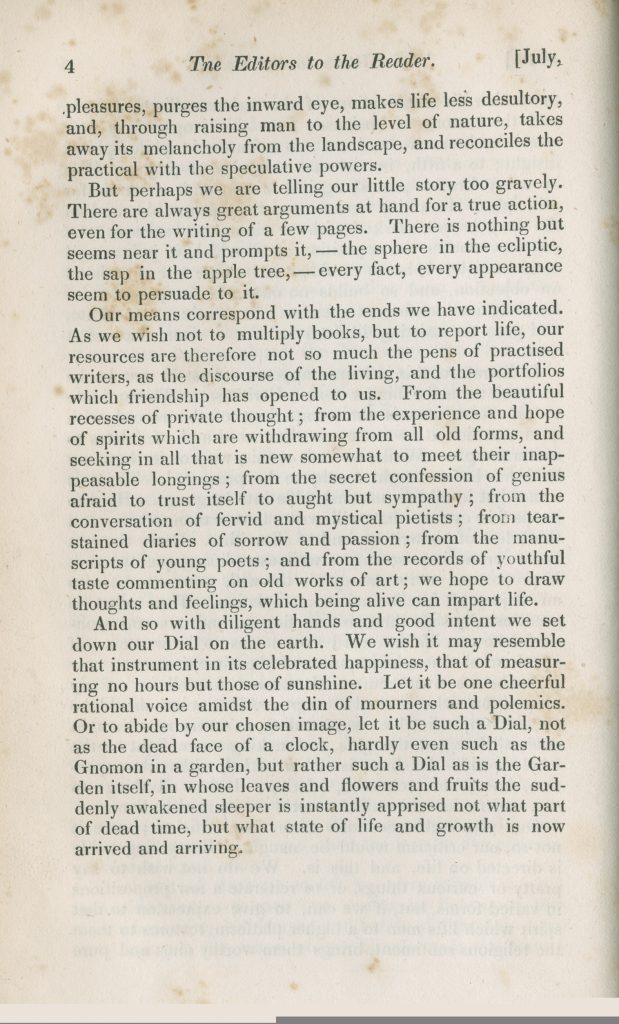

Selection: Margaret Fuller, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and George Ripley, “The Editors to the Reader,” in The Dial: A Magazine for Literature, Philosophy, and Religion, 2-4 (1840).

Emerson, Fuller, and Ripley embarked on publishing the Dial at a time when American print culture had exploded. Scholar Robert Michael Ruehl notes that there were over 1,500 magazines in print in 1840. Many of these magazines opened and folded within a few years or even months and the Dial’s four-year life—it closed in 1844—represents a respectable run. The excerpts below are from the letter from the editors that appeared in the first issue. Fuller drafted the letter, then saw it largely rewritten by Emerson.

Questions to Consider

- What is the “revolution” that the Dial’s editors believe they see taking place in New England? Who is participating in this revolution? What does this paragraph suggest about the kind of audience the editors hoped to find for the Dial?

- What should literature and a literary journal be, according to the Dial’s editors? How will their essays differ from standard criticism?

- What do these writers mean by “life” and “the living soul” in this letter and the quote from Ripley’s prospectus above?

- Why did Emerson, Fuller, and Ripley decide to name their journal after a sundial? (Note: the gnomon is the pin or blade on the face of the sundial that casts a shadow and indicates the hour.)

Sensational Literature

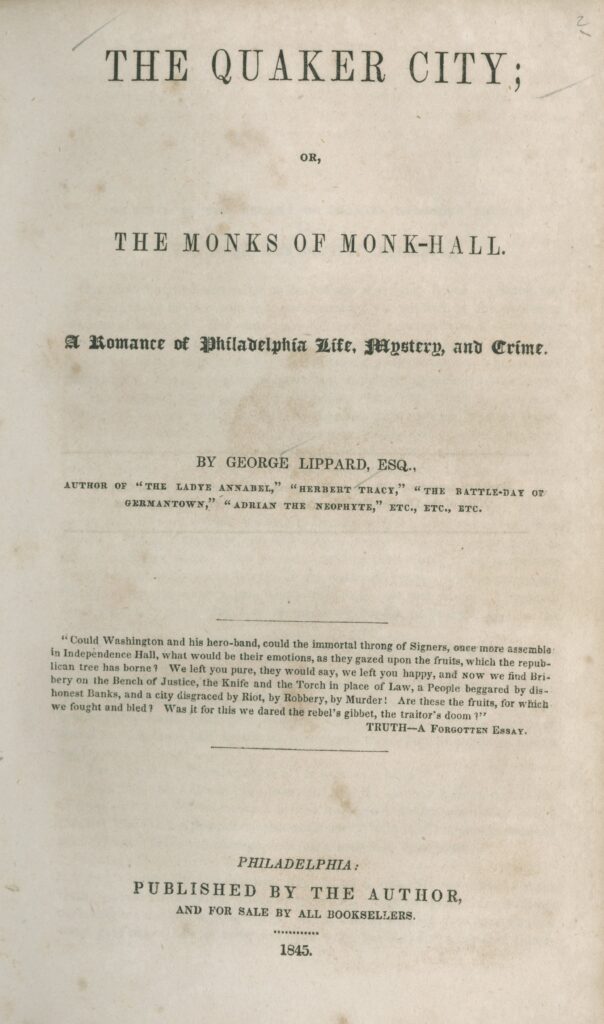

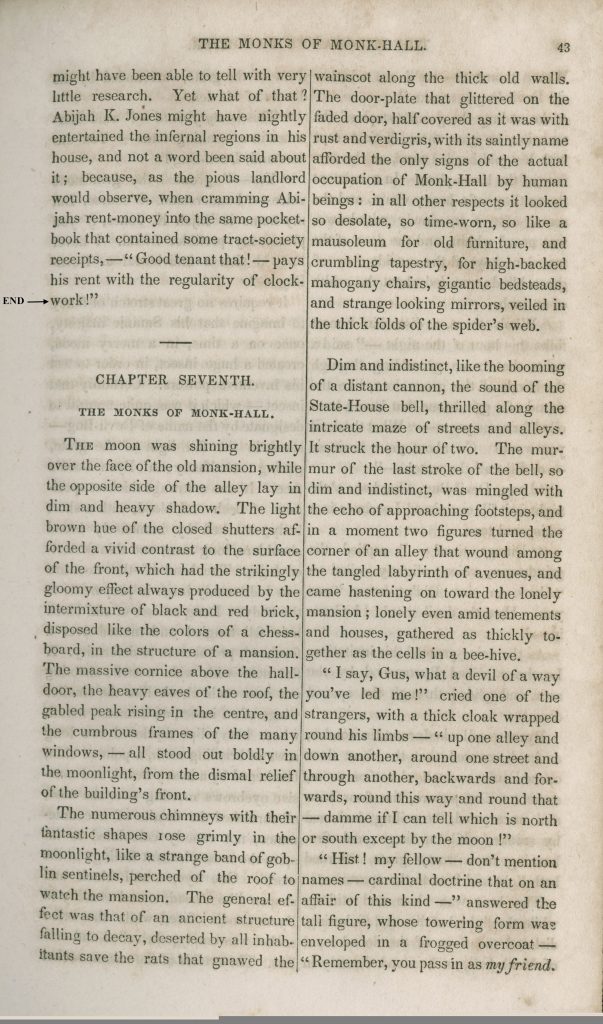

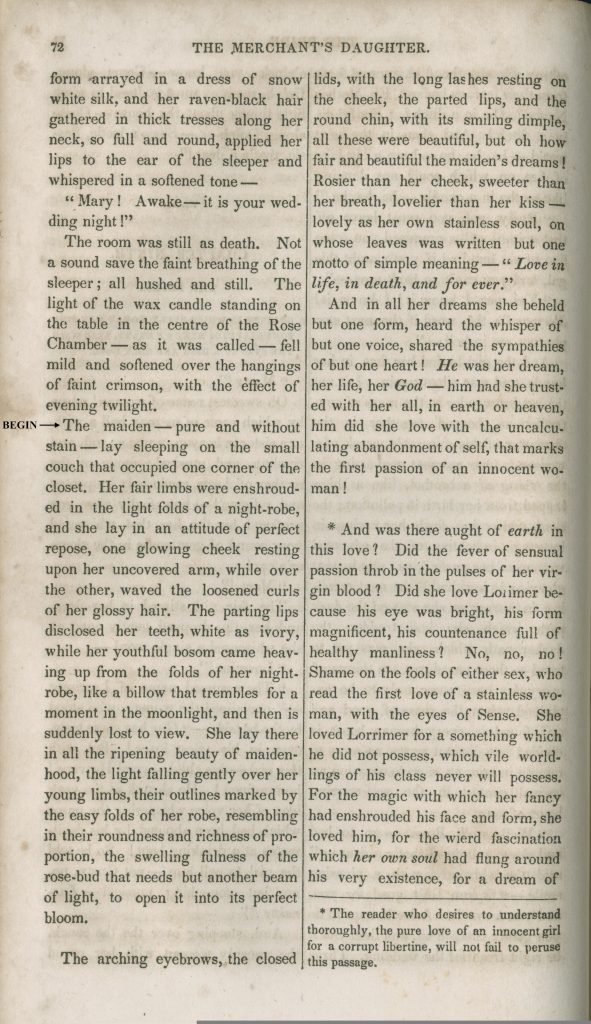

George Lippard’s works probably occupy the opposite pole from abstract, spiritual, Transcendentalist writing. His exposés of crime and corruption among the urban elite were vivid, sensational works, very much mired in the material world. Lippard possessed what critic David S. Reynolds has called a “radical-democrat sensibility.” He was harshly critical of economic inequality and the unjust treatment of women and of workers in nineteenth-century America. From 1842 until his death in 1852, at the age of 31, he wrote feverishly, producing roughly one million words a year in novels, lectures, and essays for Philadelphia’s penny newspapers. Lippard often attacked “respectable” Philadelphians, such as businessmen, politicians, and clergymen, accusing them of participating in a lurid underworld of gambling, prostitution, rape, and murder. His work was controversial—many editors considered him libelous and obscene—but it was enormously popular. His novel The Quaker City: Or, the Monks of Monk-Hall sold more copies than any novel before Uncle Tom’s Cabin: 60,000 in 1845, the year it was published, and 10,000 each year for the decade that followed.

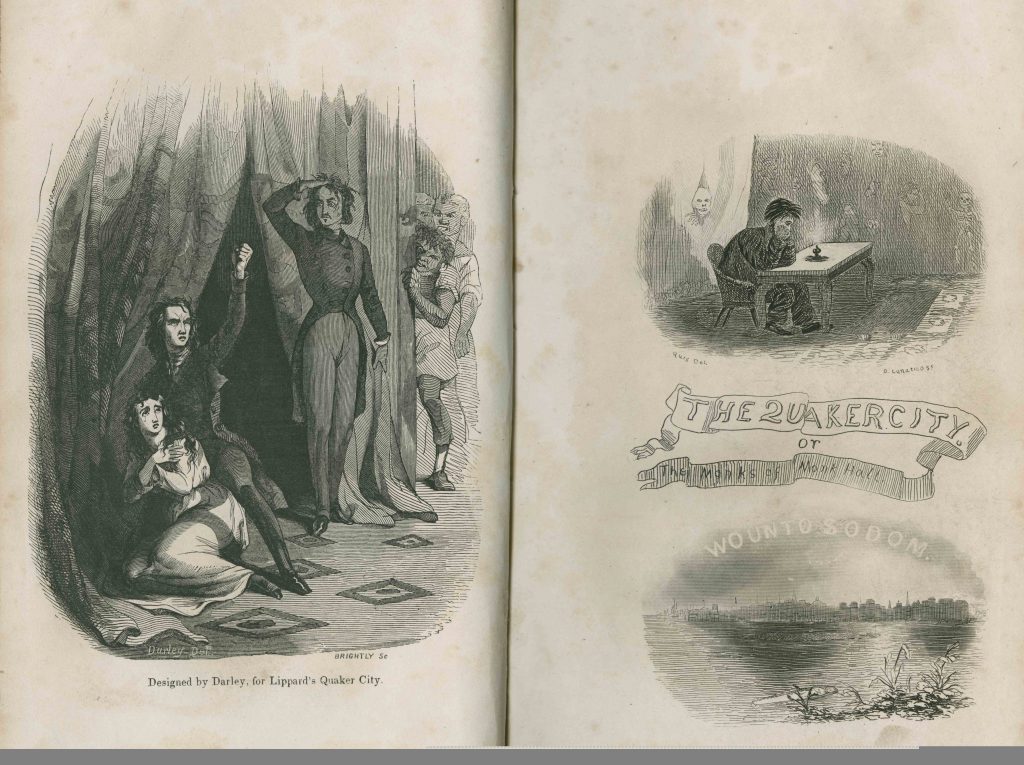

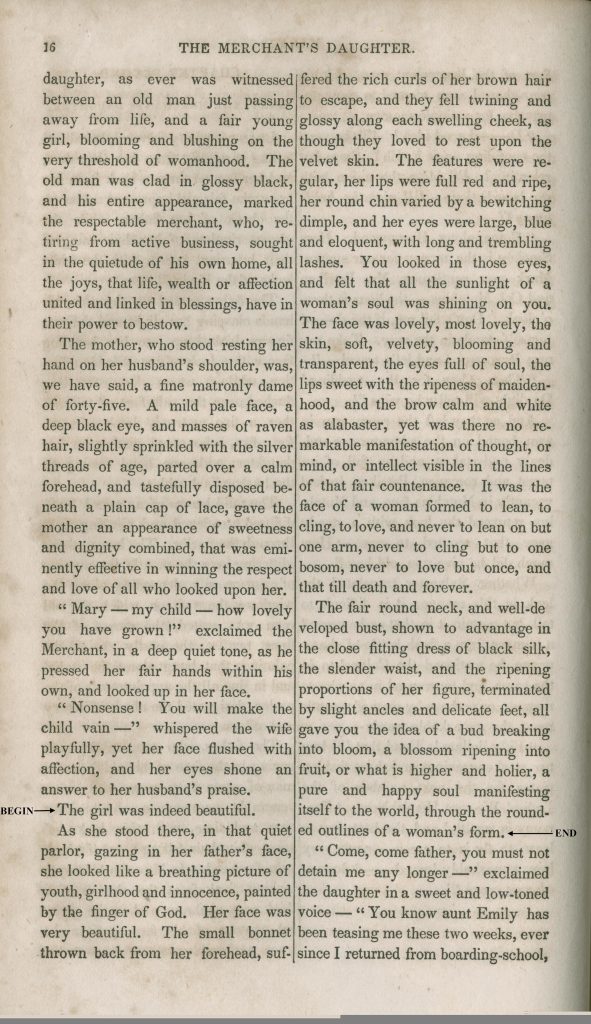

Selection: George Lippard, The Quaker City: Or, the Monks of Monk-Hall: A Romance of Philadelphia Life, Mystery, and Crime, 16, 41-43, 72-73 (1845).

Quaker City centers on events at Monk-hall, a secret club in the heart of the city, over the course of three days. It weaves together several main plots. The excerpts in this section portray Mary Arlington, a merchant’s daughter, who elopes with Gustavus Lorrimer under the promise of marriage. Lorrimer takes her to Monk-hall and rapes her. Mary’s brother Byrnewood then murders Lorrimer in revenge. (Reynolds notes that the plot is loosely based on an 1843 scandal in which a Philadelphia man was acquitted of murdering his sister’s seducer.)

Questions to Consider

- Examine the title page and frontispieces to Quaker City. How do they introduce the novel and picture the Mary/Byrnewood/Lorrimer plot?

- How does Lippard portray Mary in these passages? What beliefs does he express about the nature of women, men, and sexuality?

- The chapter on Monk-hall traces the obscure history of the mansion, from its obscure origins—its construction by an unknown “wealthy foreigner” sometime before the Revolution—to its mysterious existence in Philadelphia in 1845. How has the city changed in the roughly 60 years since the Revolution? How is an institution like Monk-hall, a site of countless crimes, able to exist in mid-nineteenth-century Philadelphia? What does its existence say about the city?

- What is the tone of this writing? What makes it “sensational”? Why do you think it was so popular and so controversial? Do you think his writing would promote social reform, as he seemed to intend? In what ways?

- How would you compare Lippard’s style to the language of the Transcendental and sentimental works elsewhere in this collection?

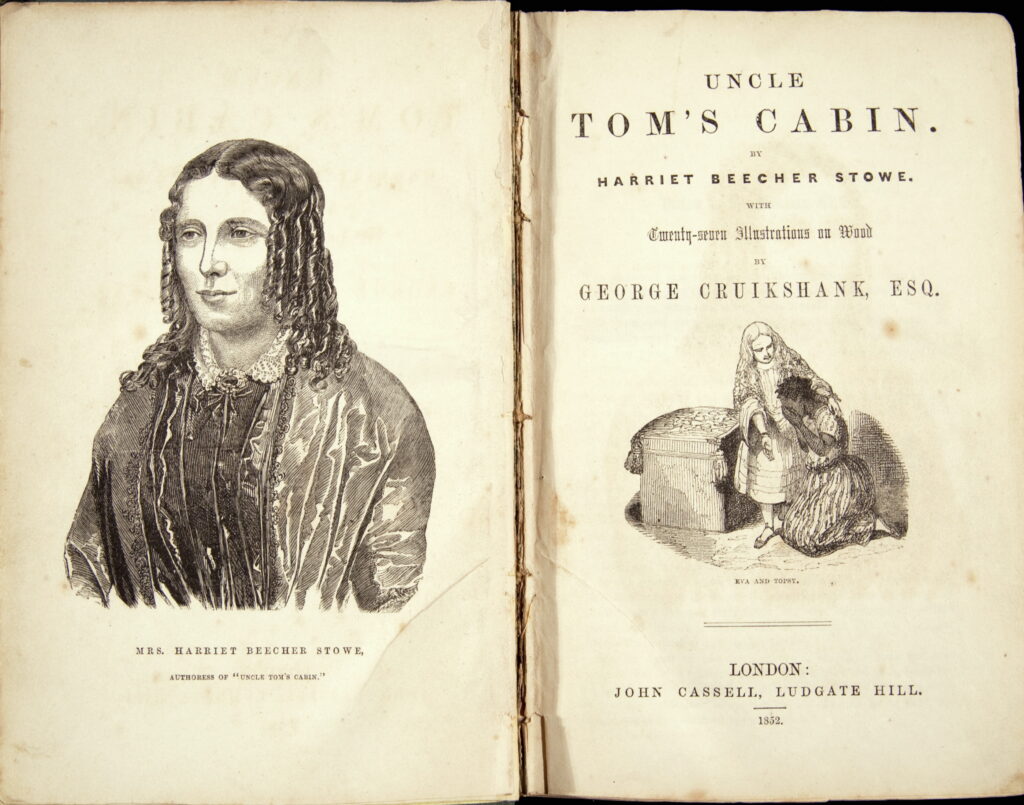

Sentimental Literature

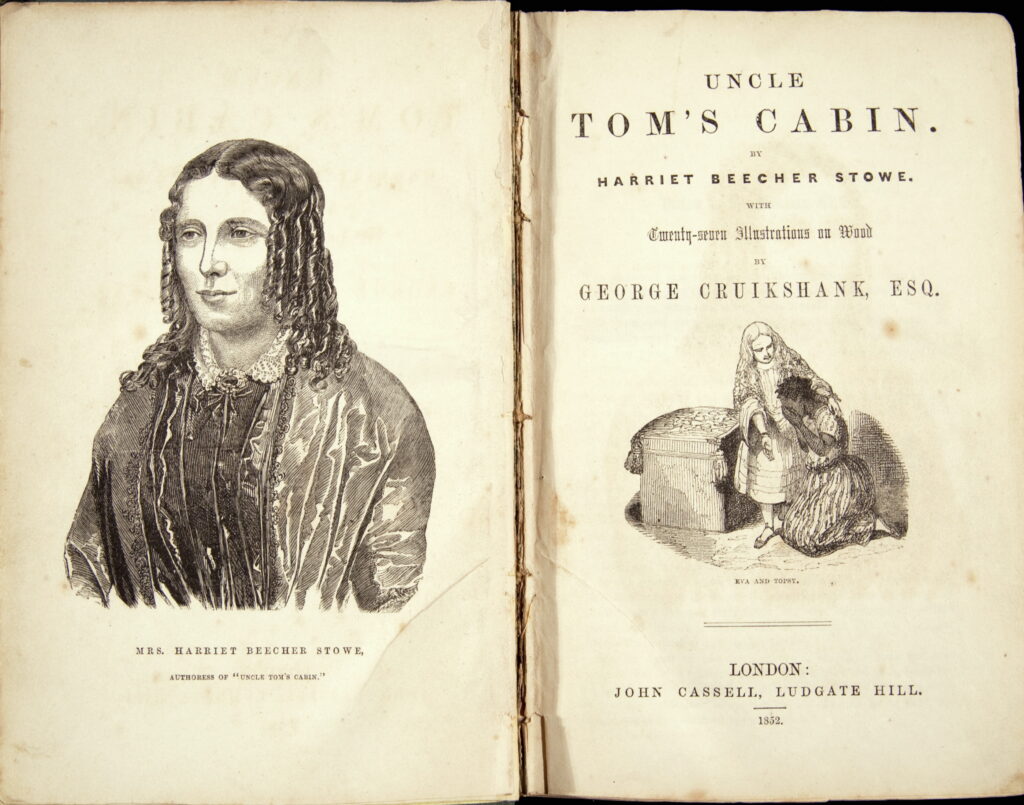

The most widely read authors of the 1850s were not men, such as Hawthorne and Melville, associated with the canon of American Renaissance literature or even the sensational George Lippard, who died in 1852. Instead, they were women writers such as Harriet Beecher Stowe and Fanny Fern. While Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter sold fewer than 12,000 copies in the 1850s, Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin sold over 300,000 in six years, “more copies than any book in the world except the Bible,” according to critics Susan Belasco Smith and Elizabeth Ammons. Fern’s Fern Leaves from Fanny’s Port-Folio, a collection of her periodical essays and fiction, sold 70,000 copies in the United States and 29,000 in England within a year of its publication in 1853. Hawthorne famously complained to his publisher, “America is now wholly given over to a d—d mob of scribbling women, and I should have no chance of success while the public is occupied with their trash.” (Smith notes that he later amended that blanket indictment, writing that he had “enjoyed [Fern’s novel Ruth Hall] a good deal” and did “admire her.”)

Critics often characterize literature by Stowe, Fern, and other women as “sentimental,” meaning that it addressed women readers, featured female protagonists, and explored romantic and familial relationships. But sentimental literature reached many male readers as well and certainly had a good deal to say about men’s role in family and society. Furthermore, sentimental writers often had broad ambitions for promoting social and political reform. Uncle Tom’s Cabin with its powerful antislavery message is only the most obvious example of these ambitions.

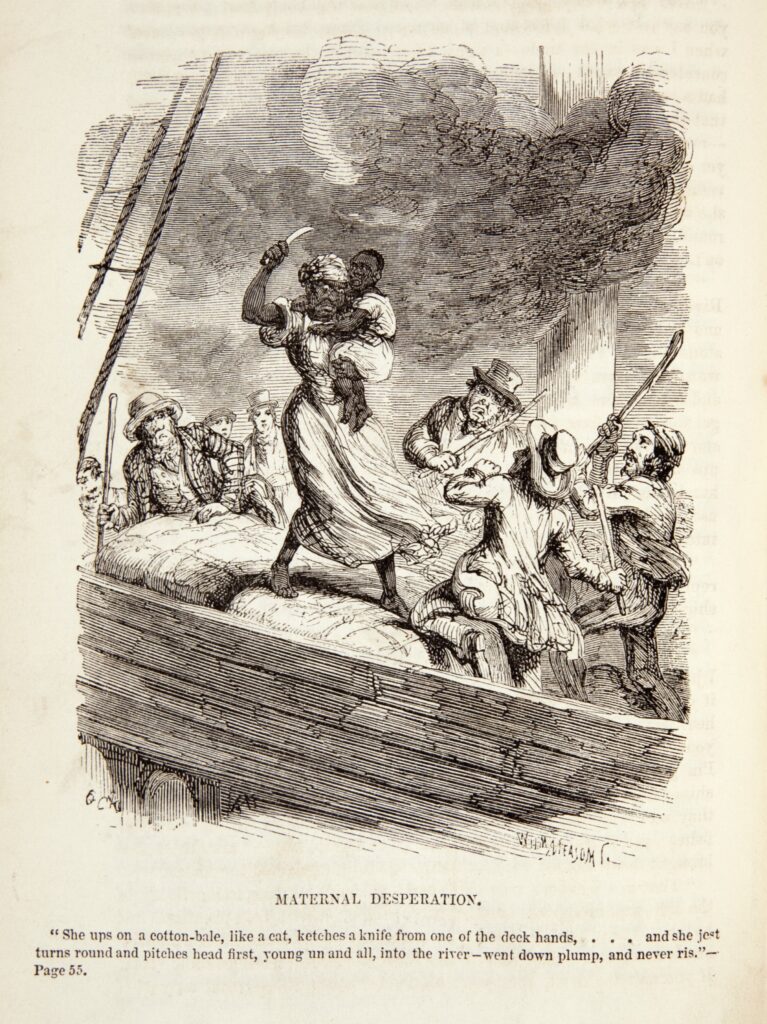

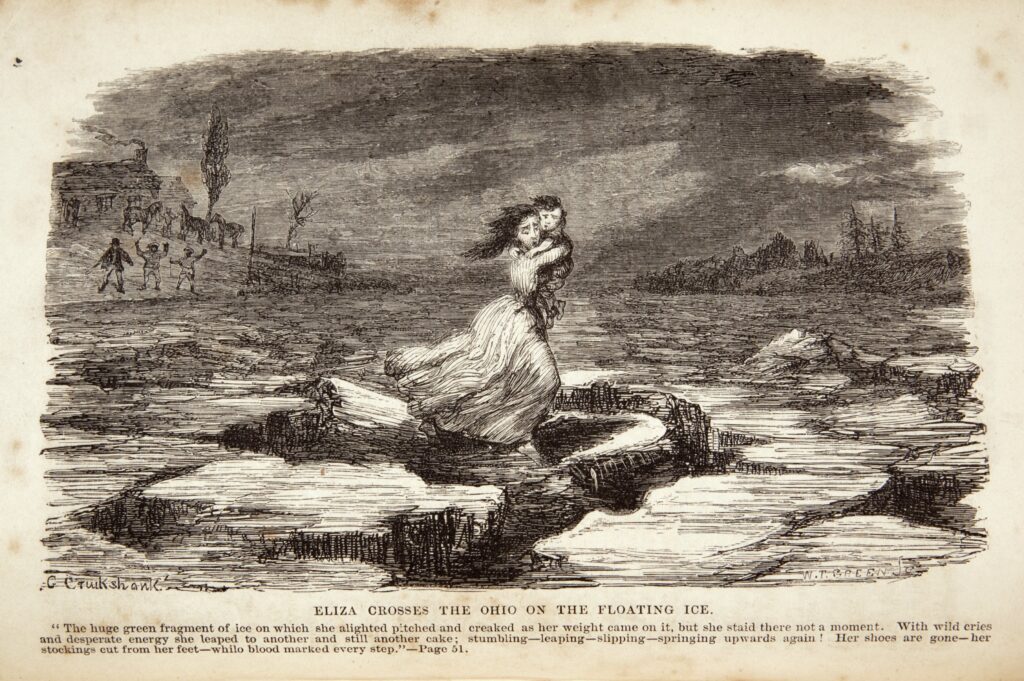

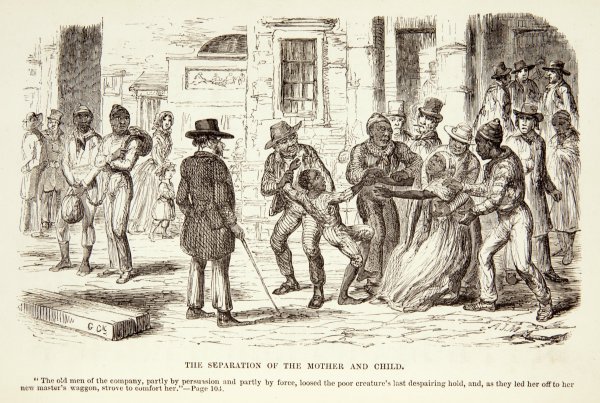

Selection: George Cruikshank’s illustrations in Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852): “Maternal Desperation,” “Eliza Crosses the Ohio on the Floating Ice,” and “The Separation of the Mother and Child”.

What unifies sentimental literature is the idea that virtue and justice come into the world through changes in people’s hearts and the operation of sympathy. At the end of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Stowe asks, “But, what can any individual do [about slavery]? … They can see to it that they feel right. An atmosphere of sympathetic influence encircles every human being; and the man or woman who feels strongly, healthily and justly, on the great interests of humanity, is a constant benefactor to the human race.” Social reform begins as something like an individual conversion experience, an emotional and spiritual experience of sympathy for another, that leads to a deeper understanding of truth and justice. Sentimental literature itself, with its strong didactic (or instructive) currents, attempts to bring such conversions about in readers.

Consistent with this view, the figure of the redemptive child is a common trope in sentimental literature. As literary critic Jane P. Tompkins has observed, these characters evoke the life of Christ: “they enact a philosophy in which the pure and powerless die to save the powerful and corrupt, and thereby show themselves more powerful than those they save.” Fern’s Lily and Stowe’s Little Eva offer examples of such characters, who bring redemption, or spiritual salvation, to others. (Uncle Tom himself is also a figure of Christ-like virtue and suffering.)

The documents in this section include illustrations and captions from the first London edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published in 1852, the same year as the first U.S. edition. These illustrations by the celebrated English artist and caricaturist, George Cruikshank, suggest the novel’s immediate, international appeal—critic Jo-Ann Morgan notes that 14 different versions of the novel appeared in England that year alone. Compare them to illustrations from the first U.S. edition and popular sheet music.

Fern’s Fern Leaves includes fiction, poetry, and essays that she had previously published in magazines and newspapers, as well as illustrations. The name Fanny Fern was a pseudonym adopted by Sara Payson Willis Farrington.

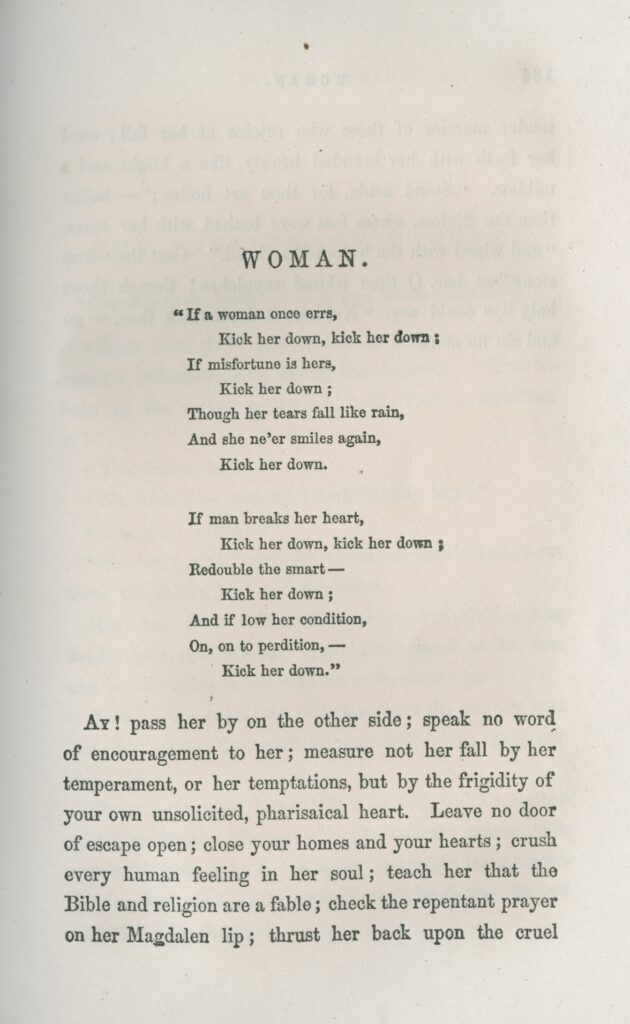

Selection: Fanny Fern, “Woman” and “The Transplanted Lilly,” in Fern Leaves from Fanny’s Port-Folio, 133-134, 254-256 (1853).

Questions to Consider

- Examine the illustrations and captions from Uncle Tom’s Cabin. They portray scenes in which slave women go to extraordinary lengths to save their children from slavery. Why do you think Stowe included so many scenes showing strong maternal devotion? How would these scenes contribute to the novel’s antislavery message?

- Fern’s story, “The Transplanted Lily,” moves quickly from Lily’s adoption by Mrs. Gray, a wealthy society woman, to their lives together, to Lily’s death. What does Mrs. Gray learn from Lily? What does the narrator mean by “Lily’s mission now is over”?

- Fern’s story can be so concise and efficient, in part, because its readers would have recognized its conventions. Why do you think nineteenth-century readers found such stories so appealing? Do you find the story moving? Why or why not?

- Examine the illustrations from Fern Leaves (including the one in the Introduction). How do they portray girls and women? How do they complement the written text?

- What is the message of Fern’s essay “Woman”? Who does she criticize in this piece? How would you characterize the essay’s tone? How does this essay differ from or resemble the voice and message of “Transplanted Lily”?

- Compare these works to Hawthorne’s novels and short fiction. What are the relationships between them? How does Hawthorne adopt, revise, or repudiate the sort of sentimental conventions that you see in Stowe’s and Fern’s writing?

Moby-Dick in Context

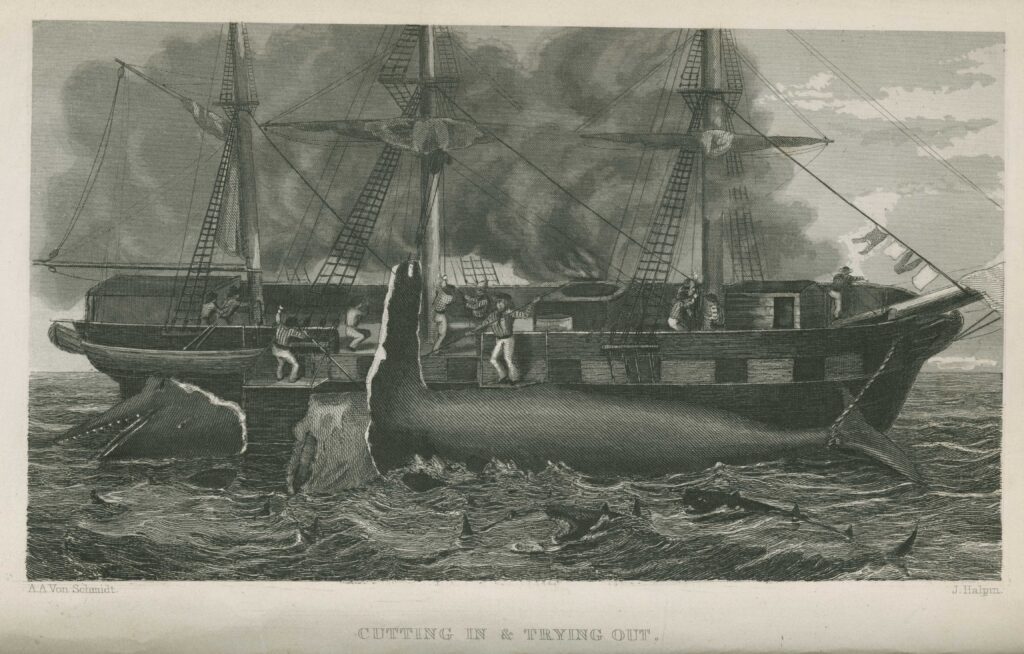

Herman Melville published relatively popular sea adventures, such as Typee and Omoo, in the 1840s before he wrote Moby-Dick. He also reviewed J. Ross Browne’s Etchings of a Whaling Cruise in the March 1847 issue of the Literary World, suggesting it may have been one of his sources for Moby-Dick, which he published in 1851, and, less directly, for Billy Budd (1891). Browne’s book was one of several first-person, nineteenth-century narratives to portray the experiences of sailors and whalemen. Melville began this review whimsically, observing, “From time immemorial many fine things have been said and sung of the sea. The days have been, when sailors were considered veritable mermen; and the ocean itself as the peculiar theatre of the romantic and wonderful.” He proceeded to lament the “many plain, matter-of-fact details” included in works like Browne’s, which robbed “saltwater” of its “poetry.” That said, Melville found much to praise in the rawness and truthfulness of Browne’s narrative.

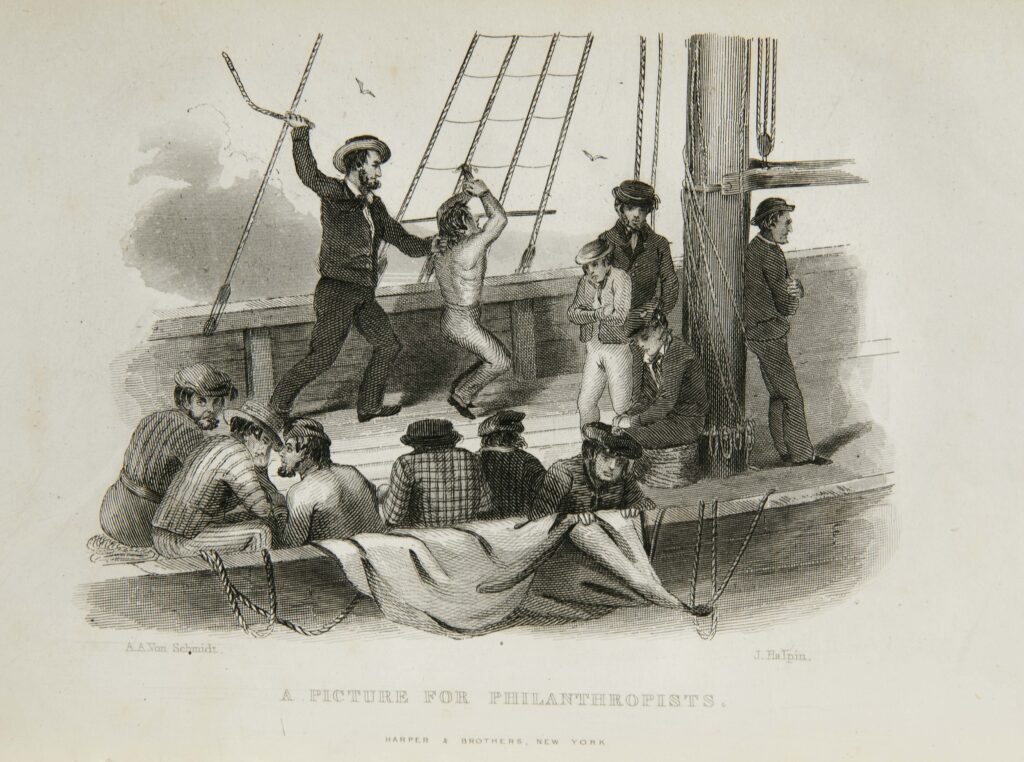

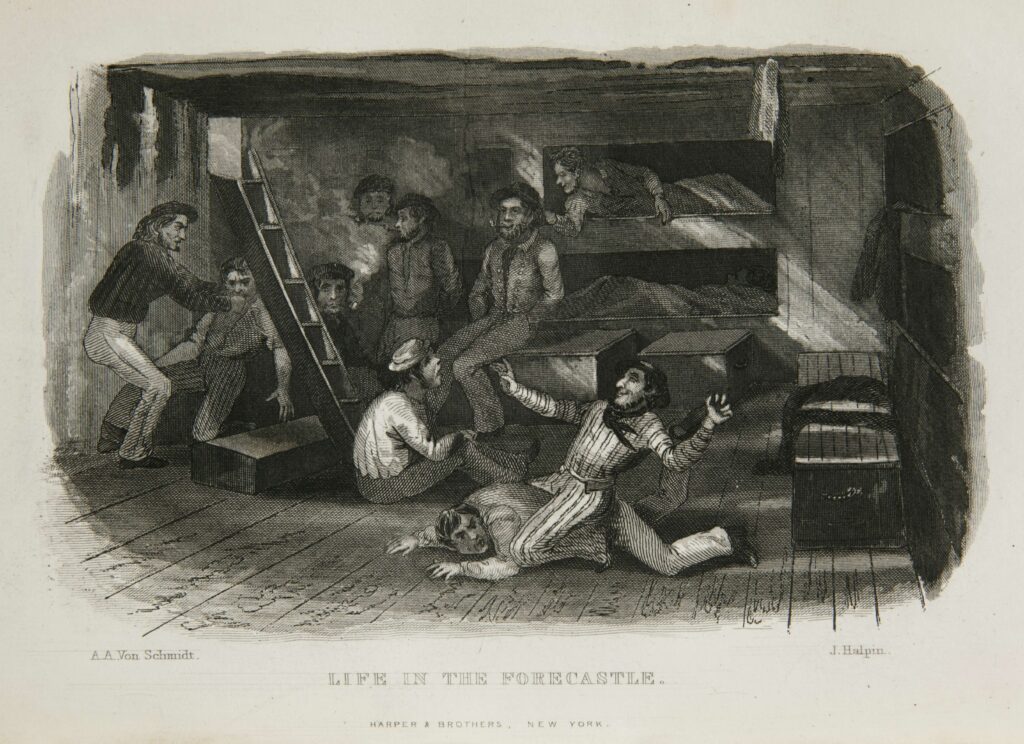

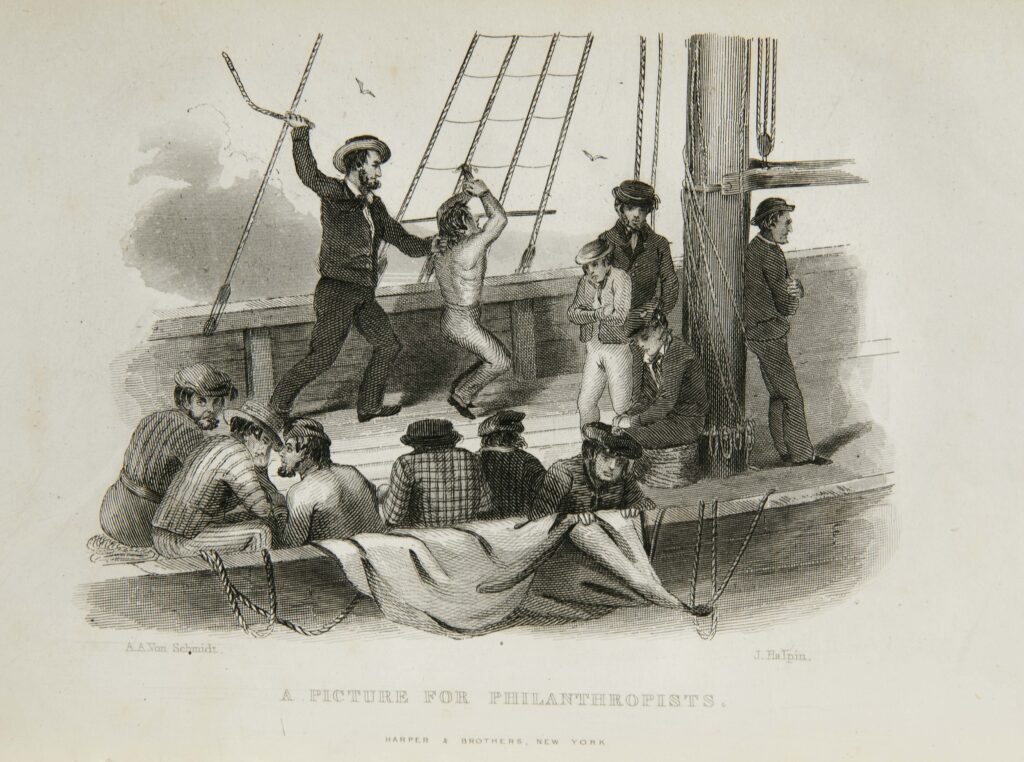

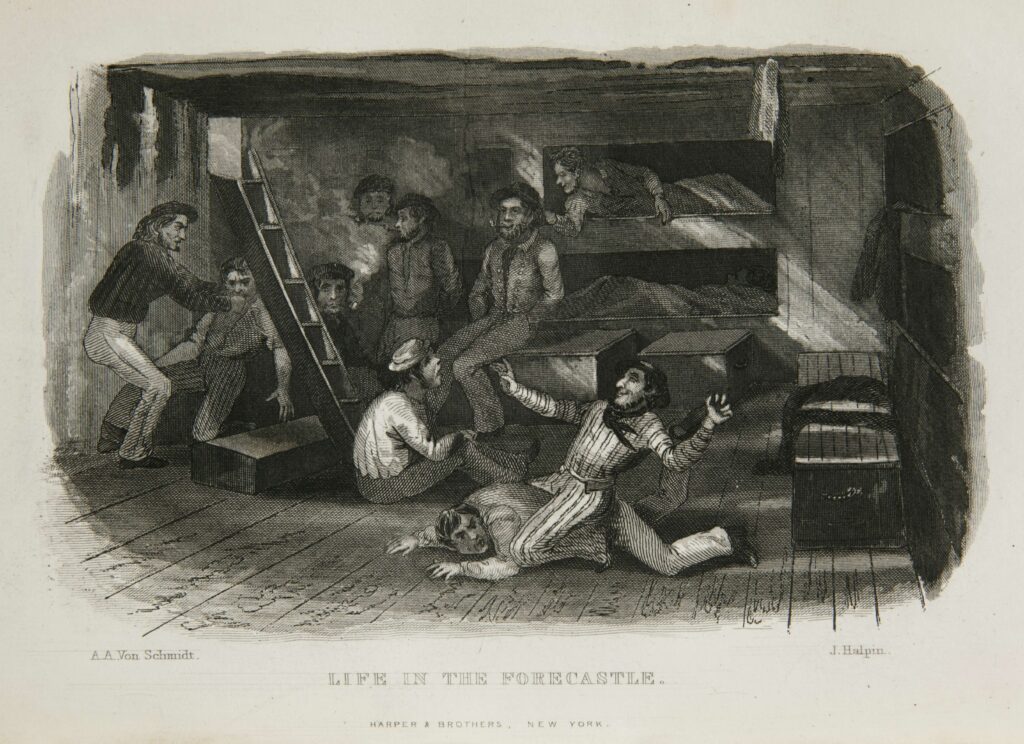

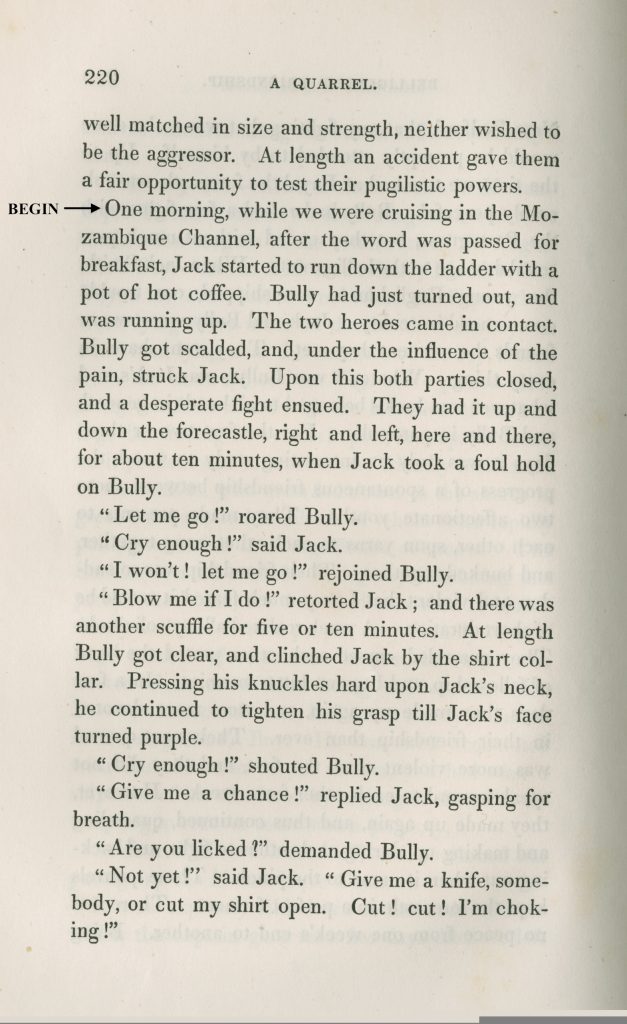

Selection: J. Ross Browne, Etchings of a Whaling Cruise: With Notes of a Sojourn on the Island of Zanzibar: And a Brief History of the Whale Fishery, in its Past and Present Condition, “Cutting in and Trying Out,” 220-224 (1846).

Excerpts from a two-part review of Moby-Dick appear below. This review by Melville’s friend Evert A. Duyckinck is one of the more generous reviews the novel received. It appeared in the New York–based magazine Literary World.

Selection: Evert A. Duyckinck, “Melville’s Moby-Dick, or The Whale,” and “Melville’s Moby-Dick, or The Whale. Second Notice,” in Literary World (1851).

Questions to Consider

- Examine the illustrations and excerpt from Browne’s Etchings (including the one pictured in the Introduction). How does Browne portray life on a whale ship? In what ways do these scenes resonate with or differ from scenes in Moby-Dick or any of Melville’s other stories of life on board ship?

- Duyckinck begins his review of Moby-Dick with an account of a whale-hunt, reported in the newspapers, that he believes is the basis for Melville’s narrative. How does Melville draw on this reported whaling episode in Moby-Dick? Why might he choose to embed this news story in his novel?

- On what grounds does Duyckinck criticize or praise Moby-Dick? Do you agree with his assessment? Why or why not? How would you approach Moby-Dick differently if you read it, as Duyckinck does, before it became known as a great American novel?

Further Reading

Ammons, Elizabeth. Preface. In Uncle Tom’s Cabin. By Harriet Beecher Stowe. New York: W.W. Norton, 1994.

Gura, Philip F. Transcendentalism: A History. New York: Hill and Wang, 2007.

Matthiessen, F. O. American Renaissance: Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman. New York: Oxford University Press, 1941.

Melville, Herman. Moby-Dick. Edited by Harrison Hayford and Hershel Parker. New York: W.W. Norton, 1967.

Morgan, Jo-Ann. Illustrating Uncle Tom’s Cabin. 2007.

Morgan, Jo-Ann. Uncle Tom’s Cabin as Visual Culture. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2007.

Reynolds, David S. Introduction. In The Quaker City or, the Monks of Monk Hall: A Romance of Philadelphia Life, Mystery, and Crime. By George Lippard. Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 1995.

Ruehl, Robert Michael. “Transcendental Disseminations: How a Movement Spread Its Ideas.” American Transcendentalism Web 2011.

Smith, Susan Belasco. Introduction. In Ruth Hall: A Domestic Tale of the Present Time. By Fanny Fern. New York: Penguin, 1997.

Tompkins, Jane. “Sentimental Power: Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the Politics of Literary History.” In Uncle Tom’s Cabin. By Harriet Beecher Stowe. New York: W.W. Norton, 1994. 501–523.

Woodlief, Ann. “The Dial: A Magazine for Literature, Philosophy, and Religion. History.” American Transcendentalism Web.