Introduction

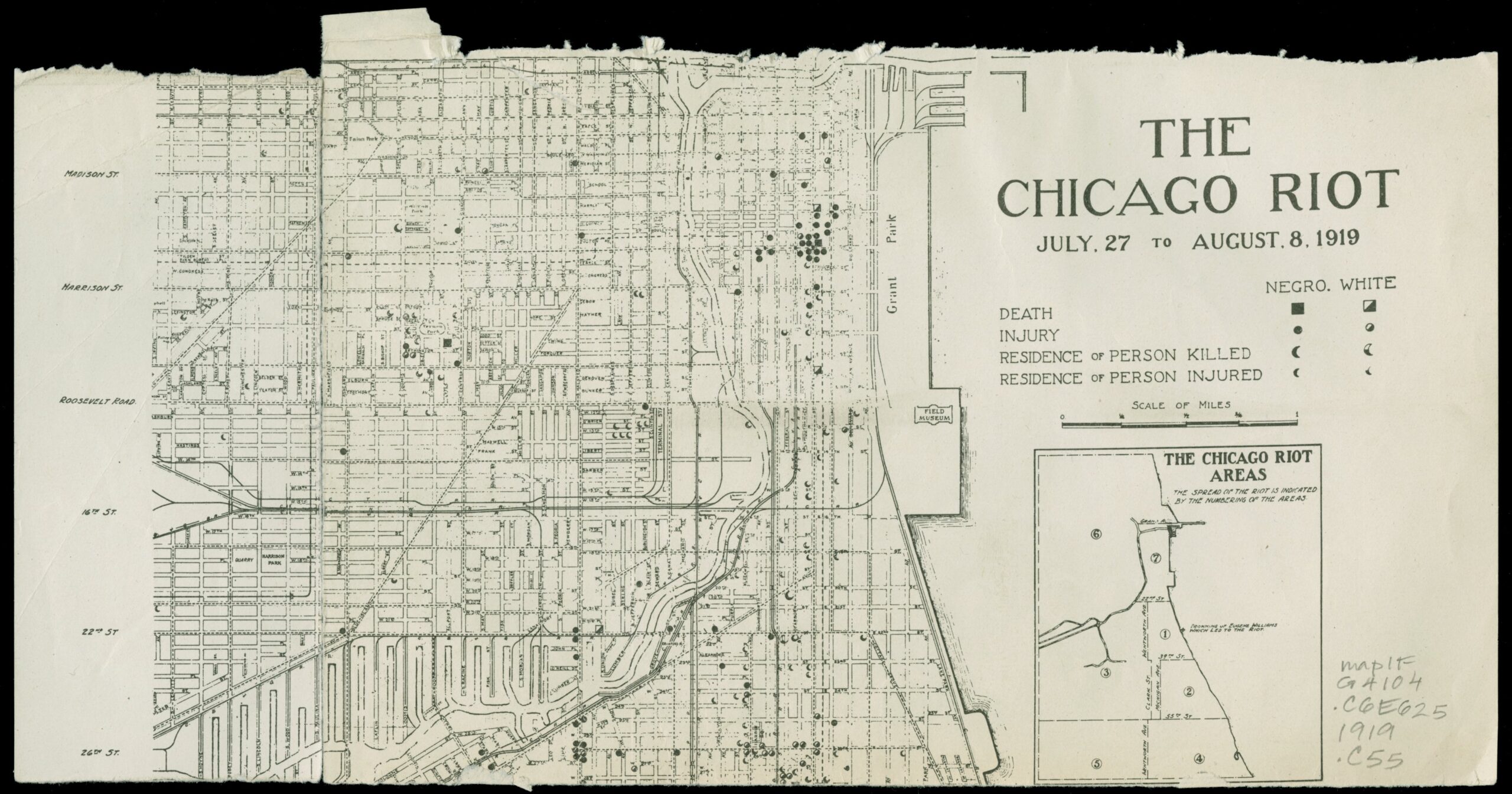

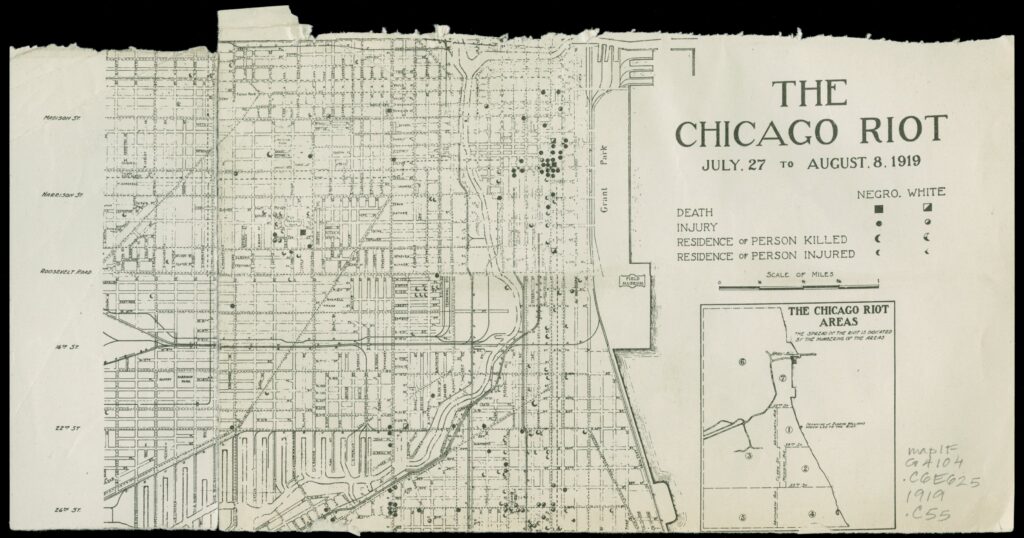

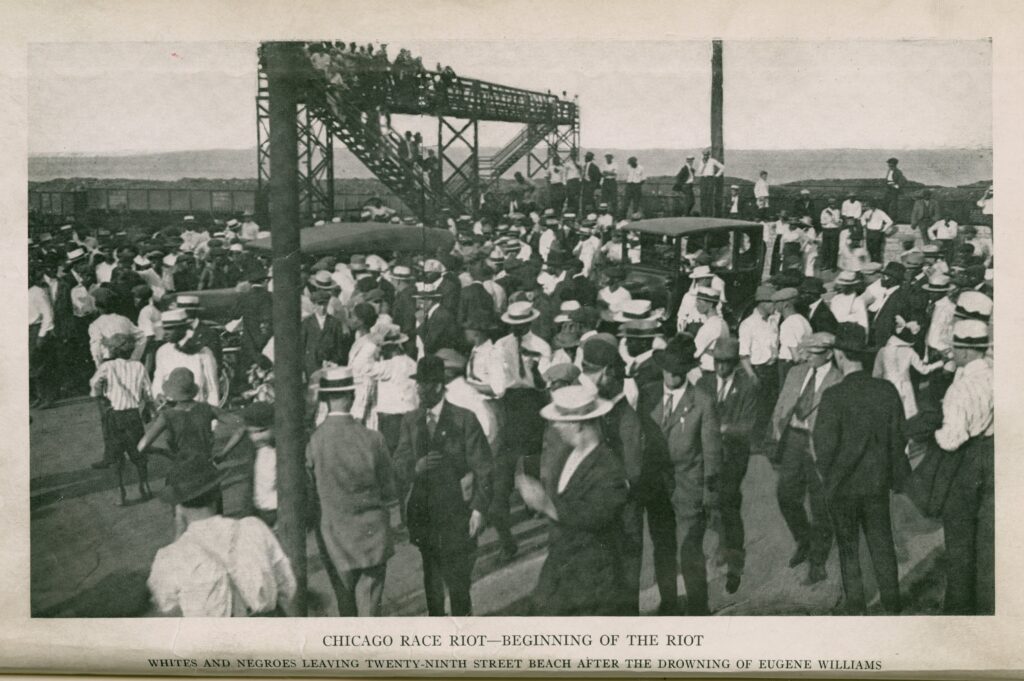

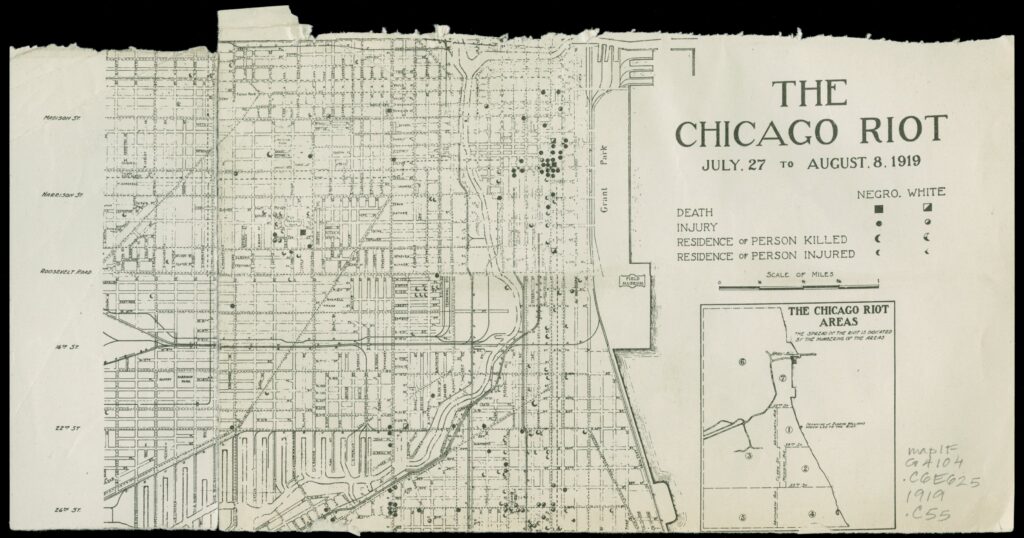

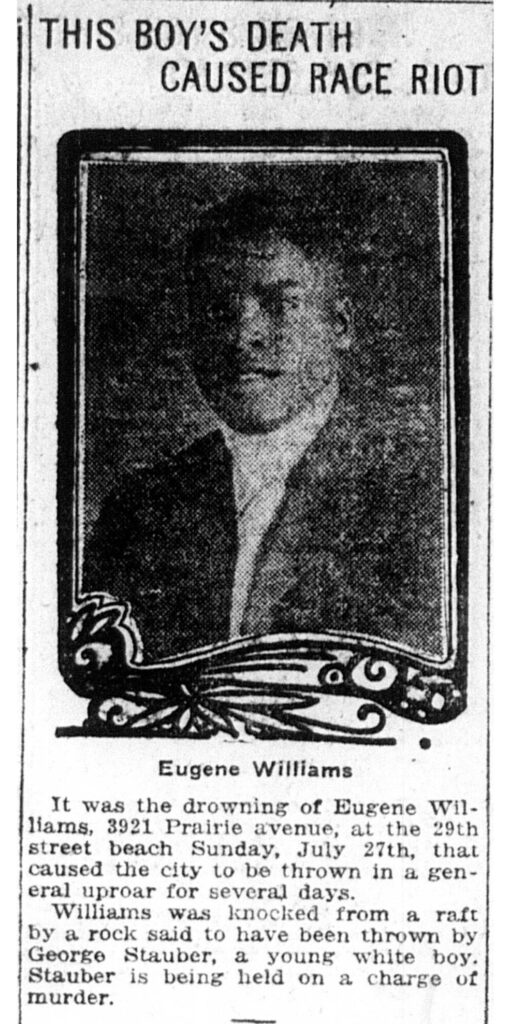

Between July 27th and August 4th, 1919, Chicago erupted in violence. The moment that caused this violence was when a white beachgoer threw a rock at a black teenager in Lake Michigan, after the teenager had floated over the invisible segregation line separating the white beach from the black beach. Legally, all beaches were open to all Chicagoans, but in practice, Chicago beaches were segregated. The teenager drowned. Witnesses identified the man who threw the rock, but the Chicago police officer on the scene refused to make an arrest. A group of African Americans from the community gathered at the beach to demand justice. Soon, mobs of white and black Chicagoans were throwing punches, committing arson, pulling one another off of streetcars, and shooting at each on the lakefront and all over the city. Thirty-eight people died, hundreds of Chicagoans were injured, and the city sustained thousands of dollars’ worth of property damage. Most of this damage occurred in the Black Belt, the area of town in which white property owners permitted black renters and businesses. Several groups—including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)—demanded a formal investigation into these incidences of violence, which were deemed “race riots.”

Archival items held at the Newberry Library tell a deeper story, one about racist housing and labor policies, incendiary newspaper articles, roving bands of violent white youths, and a pivotal moment when black Chicagoans demanded equal protection under the law.

Newspapers, public figures, and family stories have crafted lasting explanations of the violence that are still popular. One account suggests that the riots were the result of white ethnic working-class Chicagoans feeling vulnerable in the wake of the Great Migration; in other words, white immigrant laborers felt threatened by black workers as they vied for jobs, housing, and cultural influence in the city. This narrative is an apology for white supremacy, however, and fails to account for the decades of black prosperity in Chicago prior to 1919 that did not result in violence. As this digital collection will show, archival items held at the Newberry Library tell a deeper story, one about racist housing and labor policies, incendiary newspaper articles, roving bands of violent white youths, and a pivotal moment when black Chicagoans demanded equal protection under the law.

Essential Questions:

- Why did Chicagoans live in segregated areas, even though the city did not mandate segregation legally? What role did segregation play in the riots?

- What conditions before the summer of 1919 helped spark this event?

- The dictionary definition of the term “race riot” means violence between two or more races. However, the underlying meaning–or connotation–of the term frequently erases white participation in the violence. How or why is the term “race riot” an appropriate or inappropriate label for the incident?

A Segregated Chicago

Perhaps contrary to popular belief, African Americans were welcome in nineteenth-century Chicago. The first non-indigenous resident of Chicago was a black fur trader, Jean Baptiste Point du Sable. The city was a beacon for free blacks and a terminus for the underground railroad. Furthermore, Chicago’s neighborhoods were racially integrated before the 1871 Great Fire.

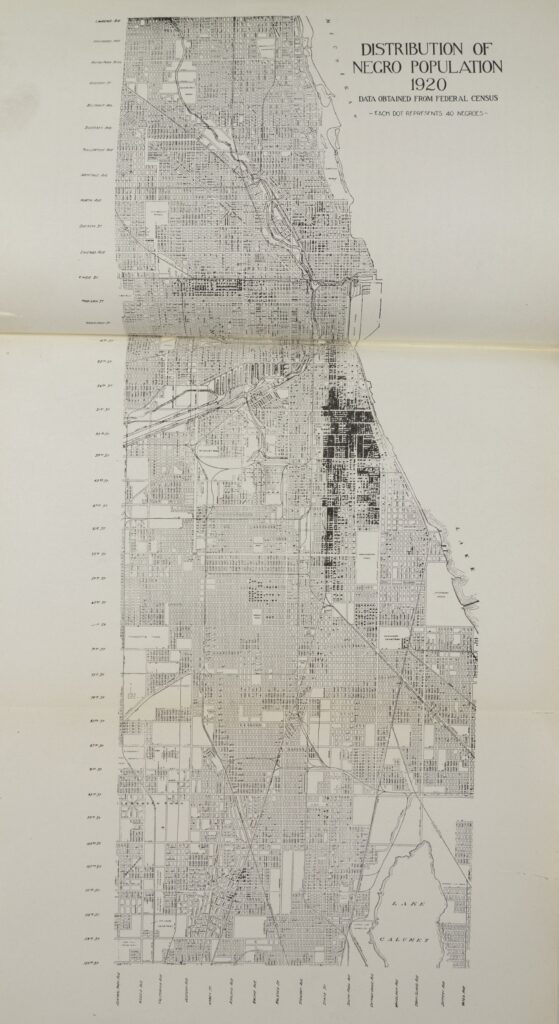

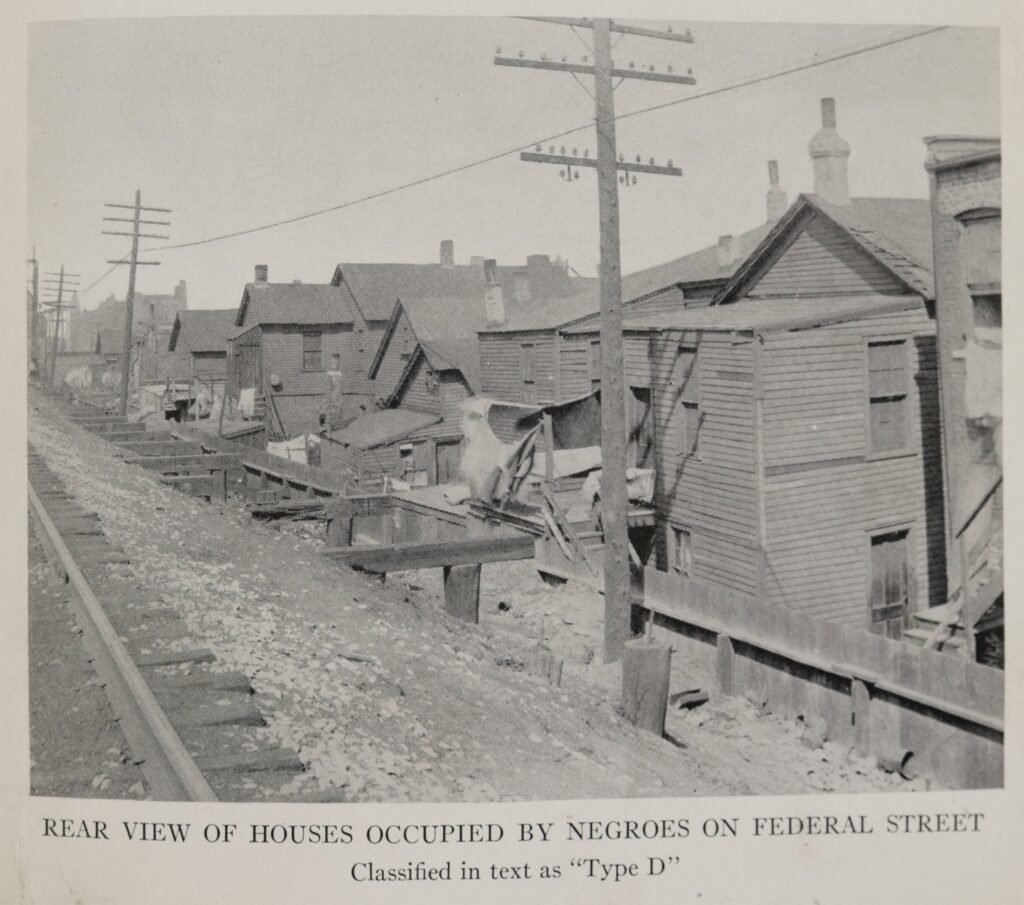

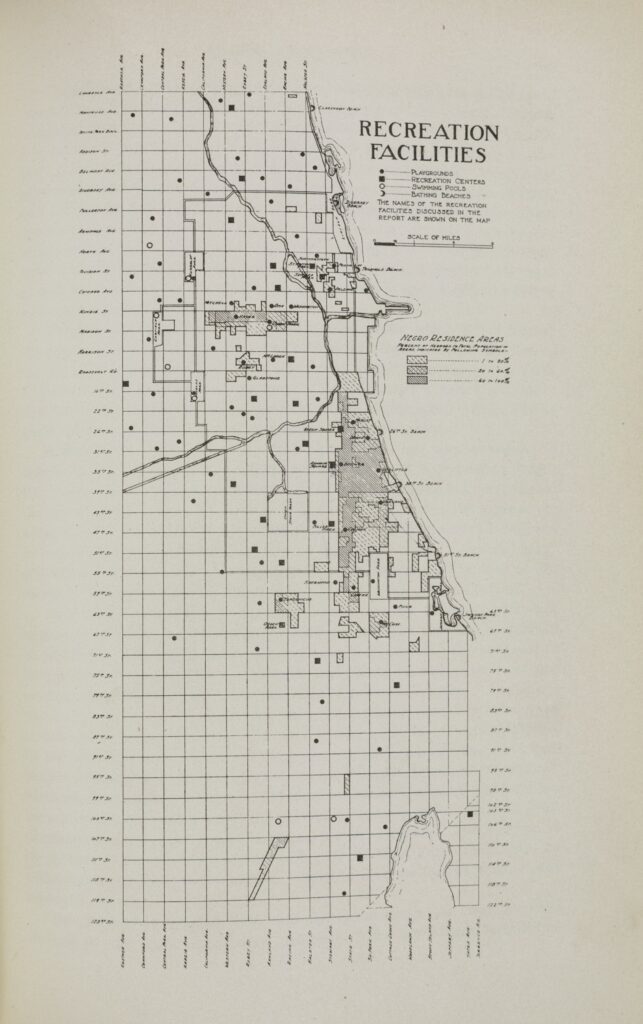

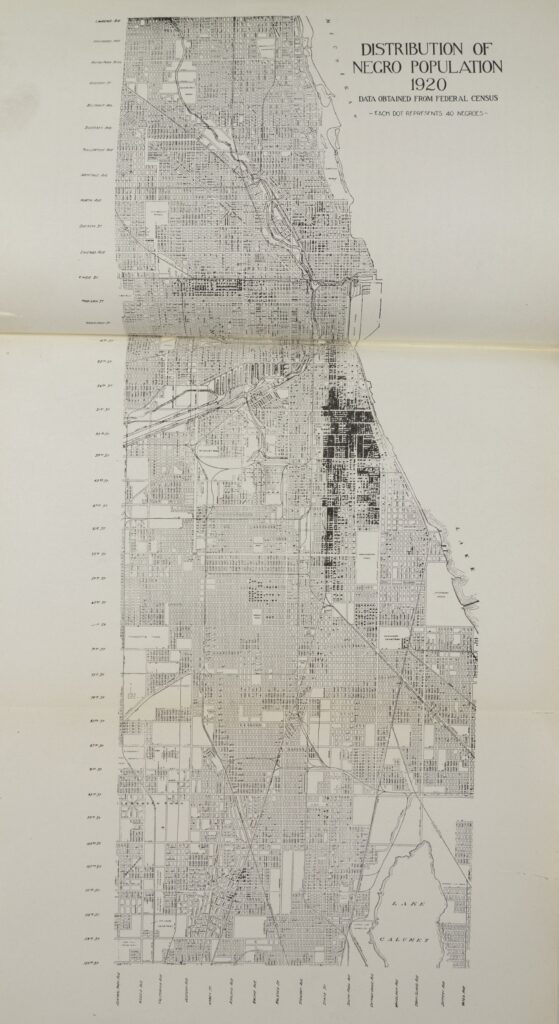

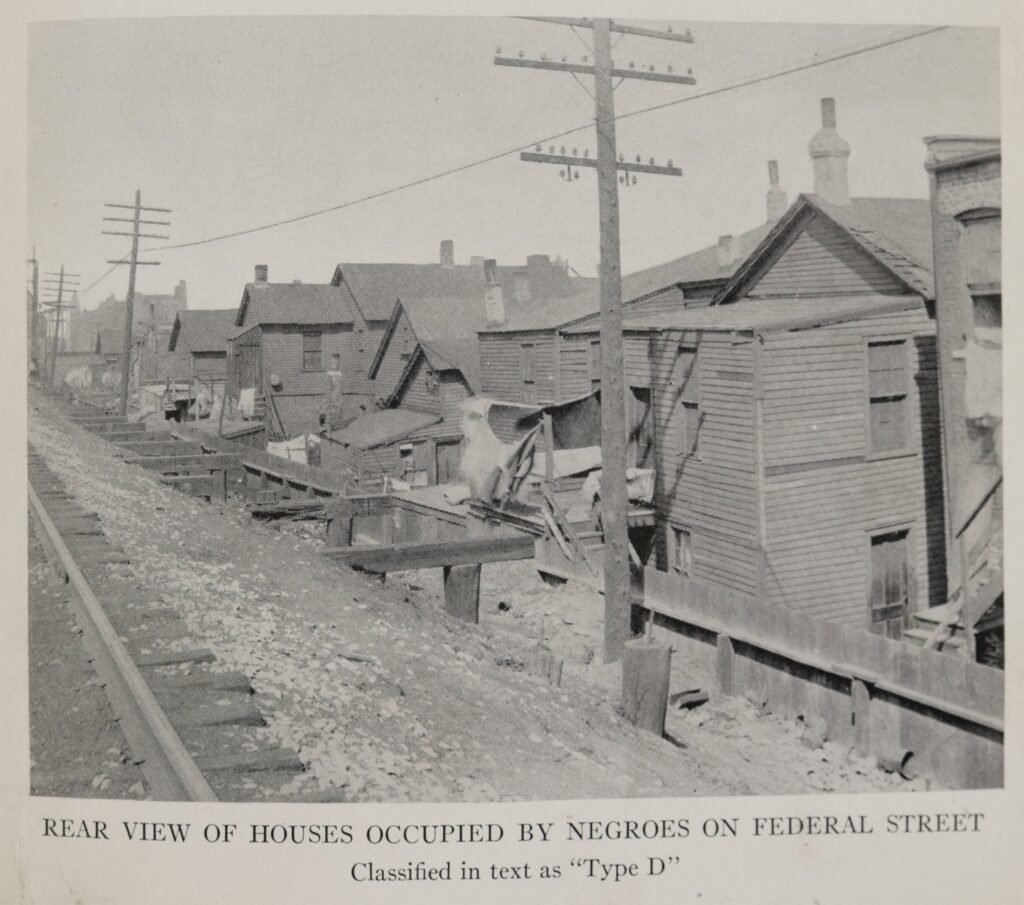

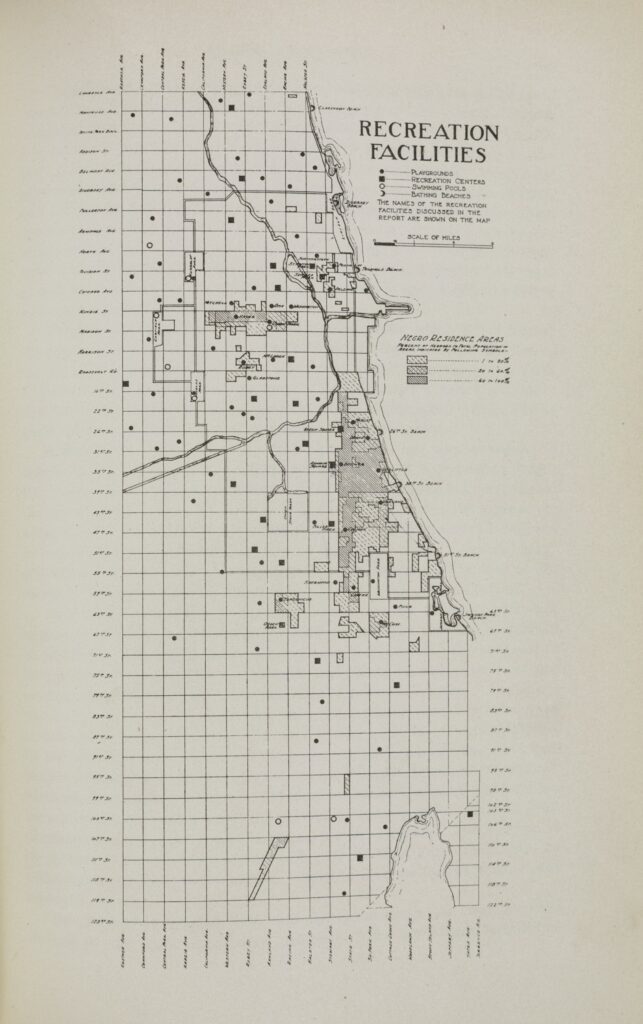

By the early twentieth century, though, discrimination against black Chicagoans was commonplace. Generally, the African-American community was restricted to the Black Belt, with 29th Street and 47th Street forming the north and south borders, and Wentworth Avenue and Cottage Grove Avenue forming the west and east borders. As the community grew, this small area could not accommodate its size. However, restrictive neighborhood covenants (contracts created by neighborhood associations that prohibited homeowners from selling or renting their houses to certain groups of people, most frequently African Americans), violence, and white landlords’ policies meant that most new arrivals lived in cramped, overpriced, and dilapidated housing. Labor opportunities for African Americans were also limited. Most black Chicagoans worked in service jobs as doormen, laundry workers, servers in restaurants in the Loop, maids and chauffeurs in wealthy homes, and maids or porters for the Pullman sleeping car company, among other occupations. But a few had secured work at the steel mills and stockyards, two major industries in the city. White unions refused to accept black laborers, however, so these industries often hired black workers as strikebreakers (workers hired to take the place of laborers on strike).

Despite these limitations, the community prospered, and the city became a center of black culture in America. Between 1909 and 1919, Chicago’s black population increased from 44,000 to 100,000. These surging African-American communities developed cultural institutions and businesses—theatres, cabarets, beauty salons, churches, social service and mutual aid associations, and banks. They also made use of municipal spaces such as public schools, parks, and the local armory, home of the celebrated Eighth Regiment and the first armory built for an African-American military regiment. Oscar de Priest became the first black man to serve on Chicago’s City Council in 1915. Legions of black Pullman porters, although serving white patrons in the railcars, were powerful missionaries for one of the most important black newspapers in the country, The Chicago Defender.

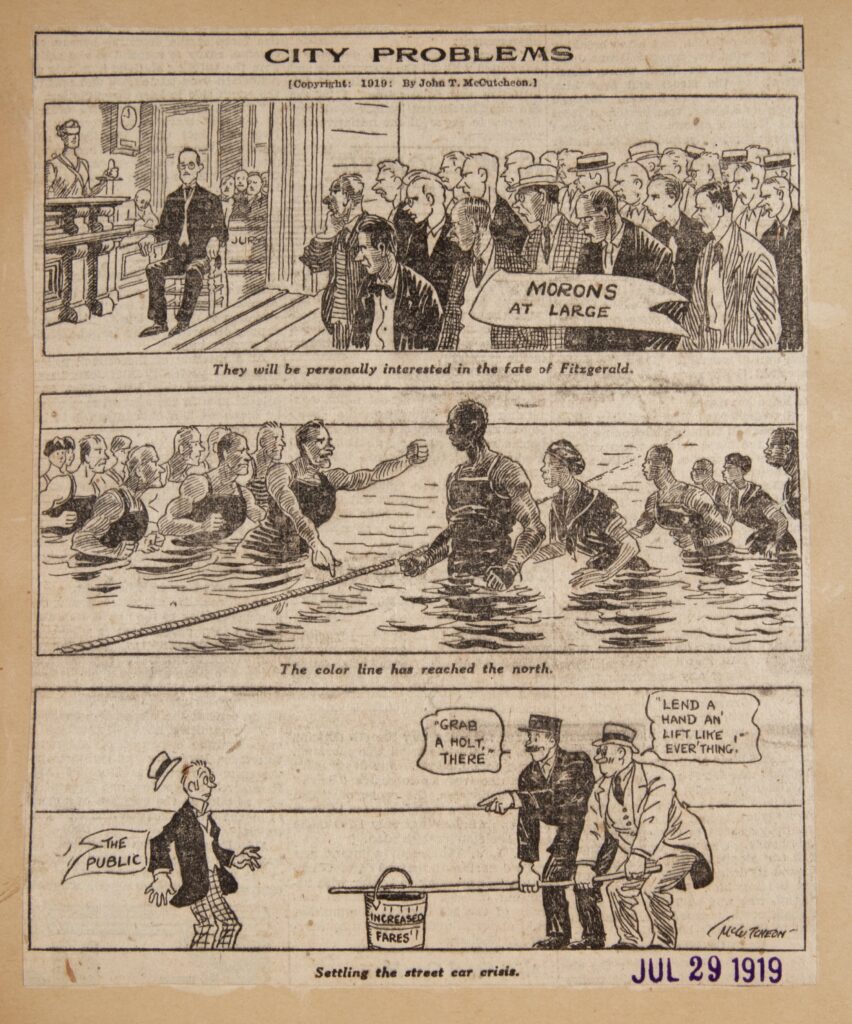

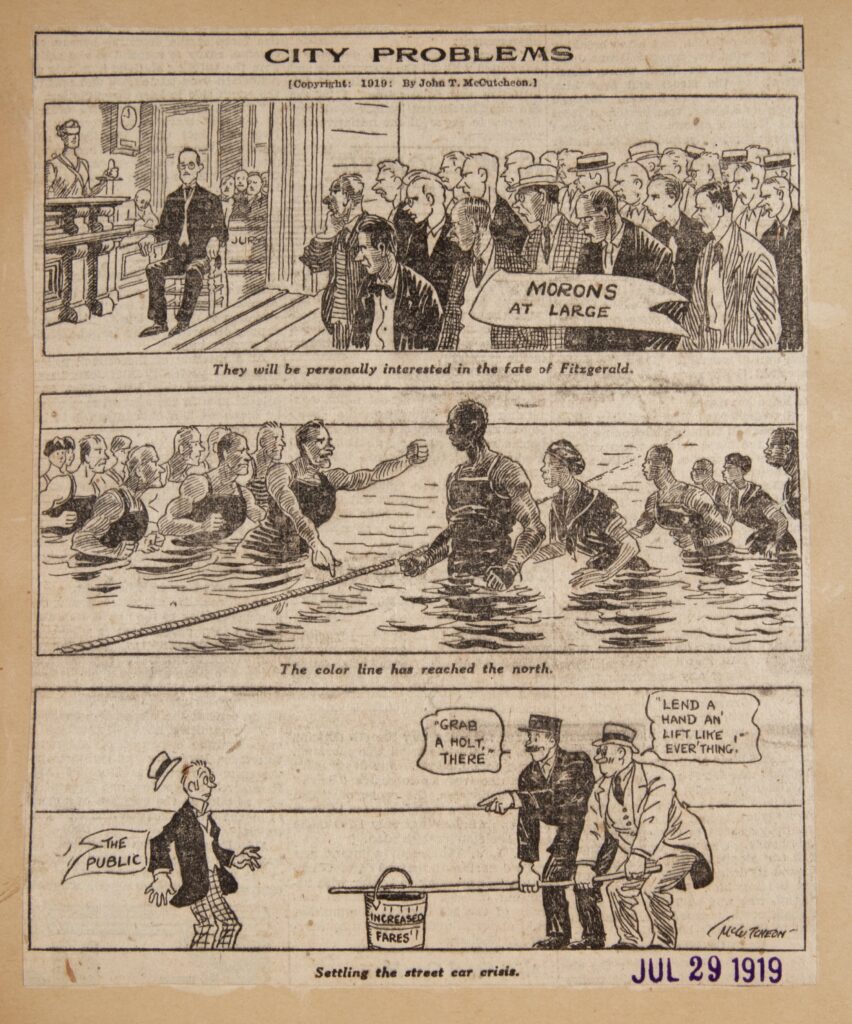

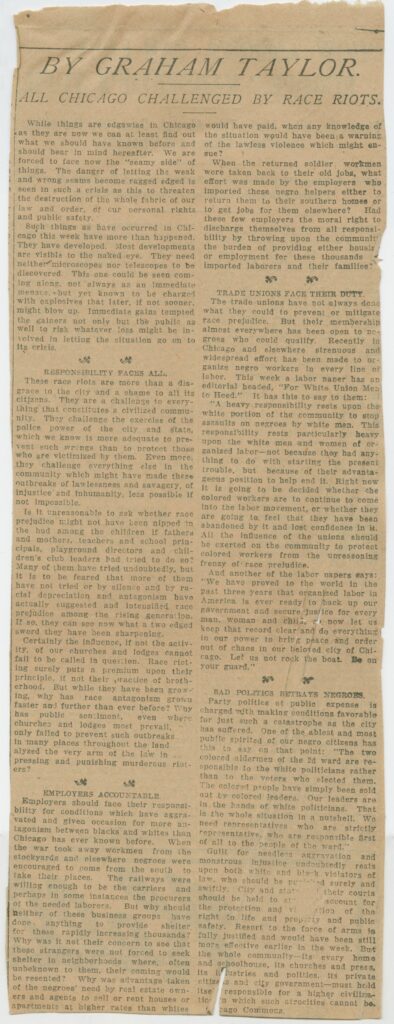

Some white Chicagoans reacted badly to this surge in black life. Two of the most popular newspapers in the city—The Chicago Daily Tribune and The Chicago Daily News—ran biased articles and racially insensitive cartoons, such as “Call from Dixie.” Content like this affected how their readership viewed the African-American community.

Discussion Questions:

- Why did black migrants from the South come to Chicago at the beginning of the twentieth century? What types of hardships did they face?

- Analyze the two cartoons published in the Chicago Tribune. What kinds of messages do they communicate about the African-American community and the City of Chicago at large?

The Riot

By 1919, several recent events had set the stage for the violence in July and August. First, black World War I veterans returning from war faced inequality and hostility across the nation. Additionally, white mobs lynched hundreds of African Americans in the South and across the nation in the first few decades of the twentieth century. Also, as black Chicagoans attempted to expand beyond the Black Belt, white gangs beat them and bombed their houses. The nation saw racial violence in East St. Louis, Illinois in 1917 and in Washington D.C. and Omaha, Nebraska in July of 1919. This violence caused the NAACP to demand that President Woodrow Wilson and Congress protect African Americans, although this call was futile.

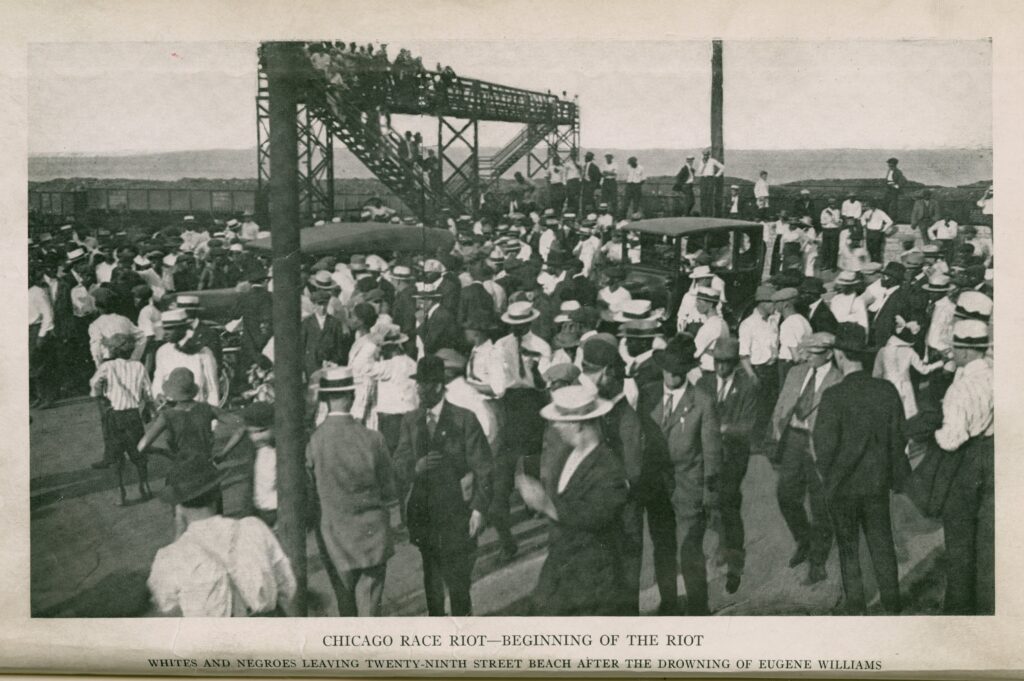

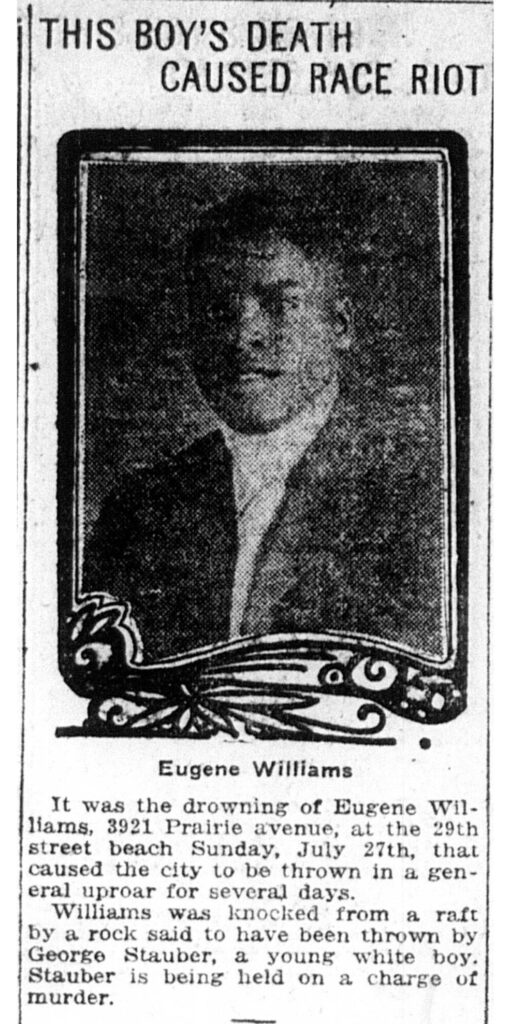

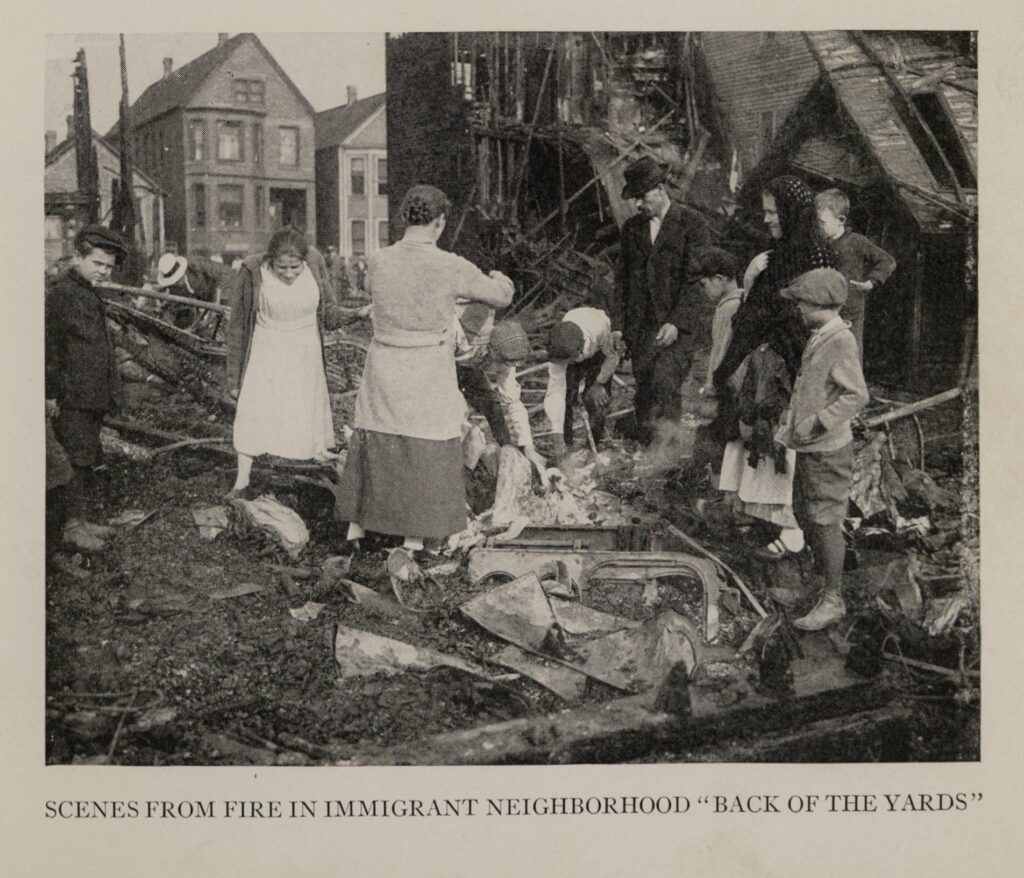

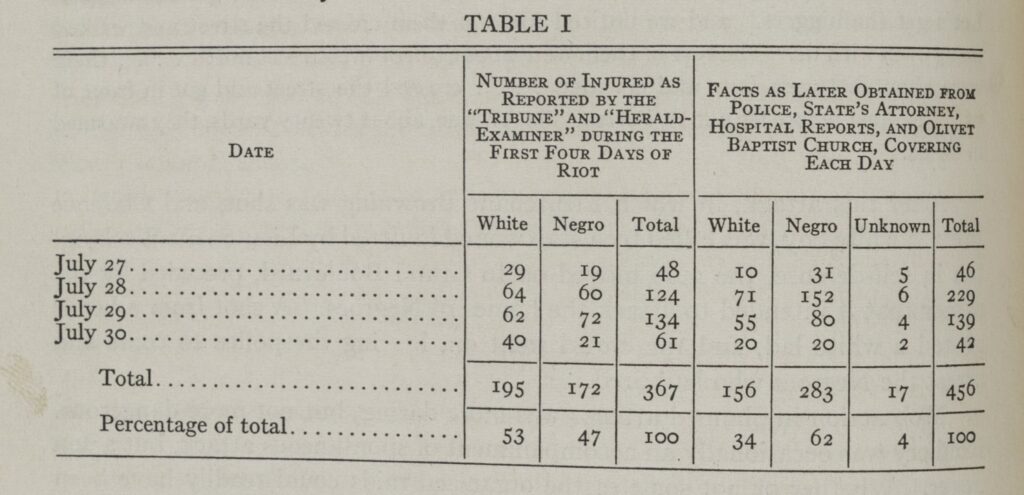

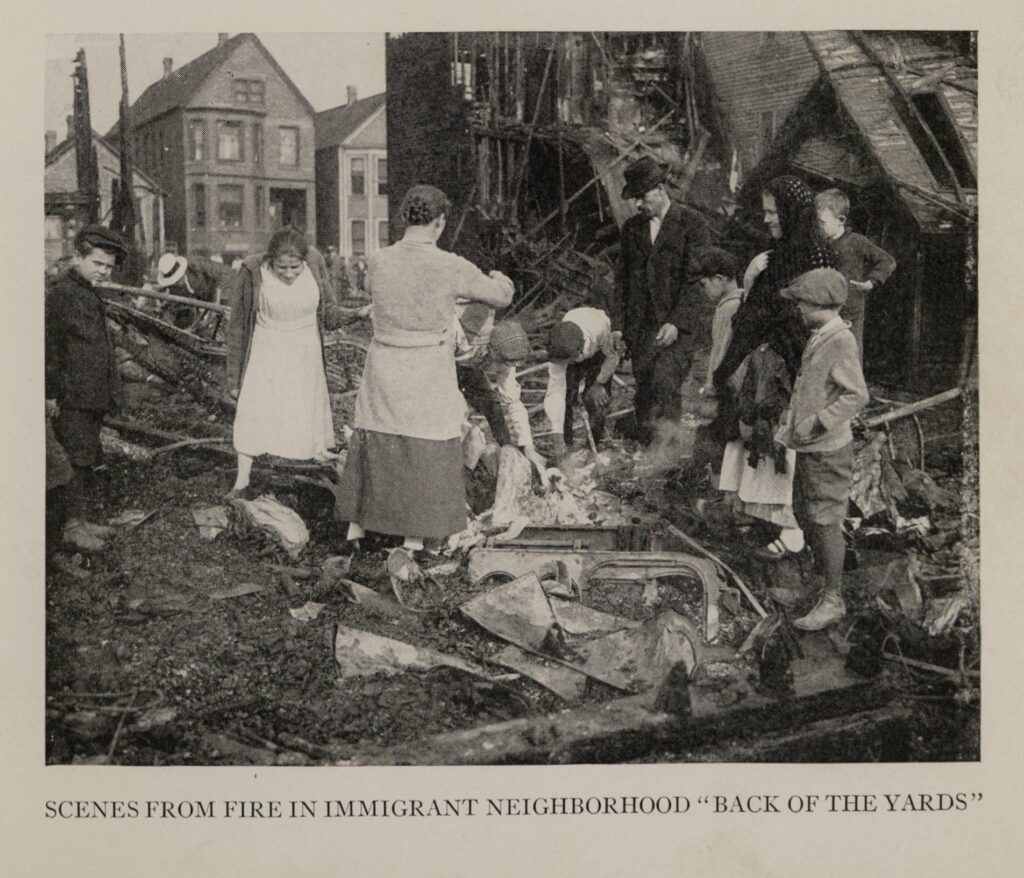

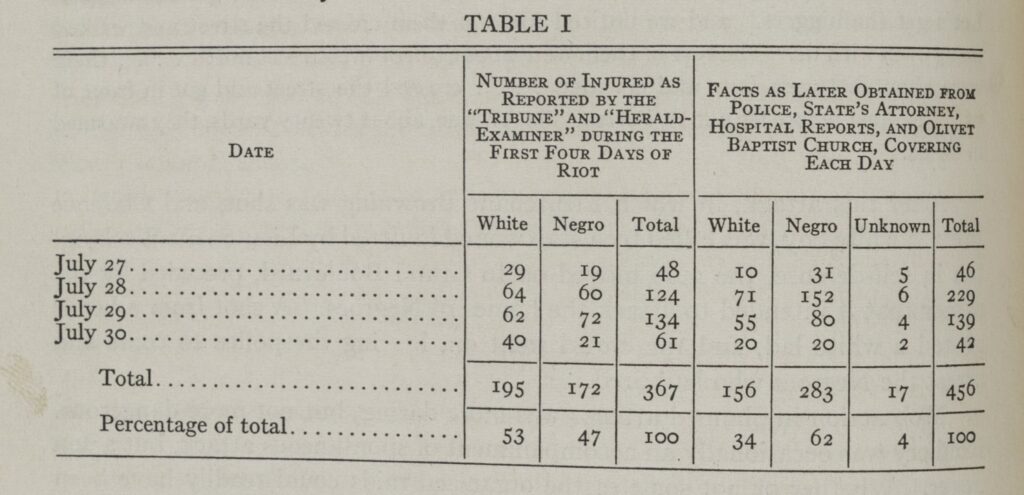

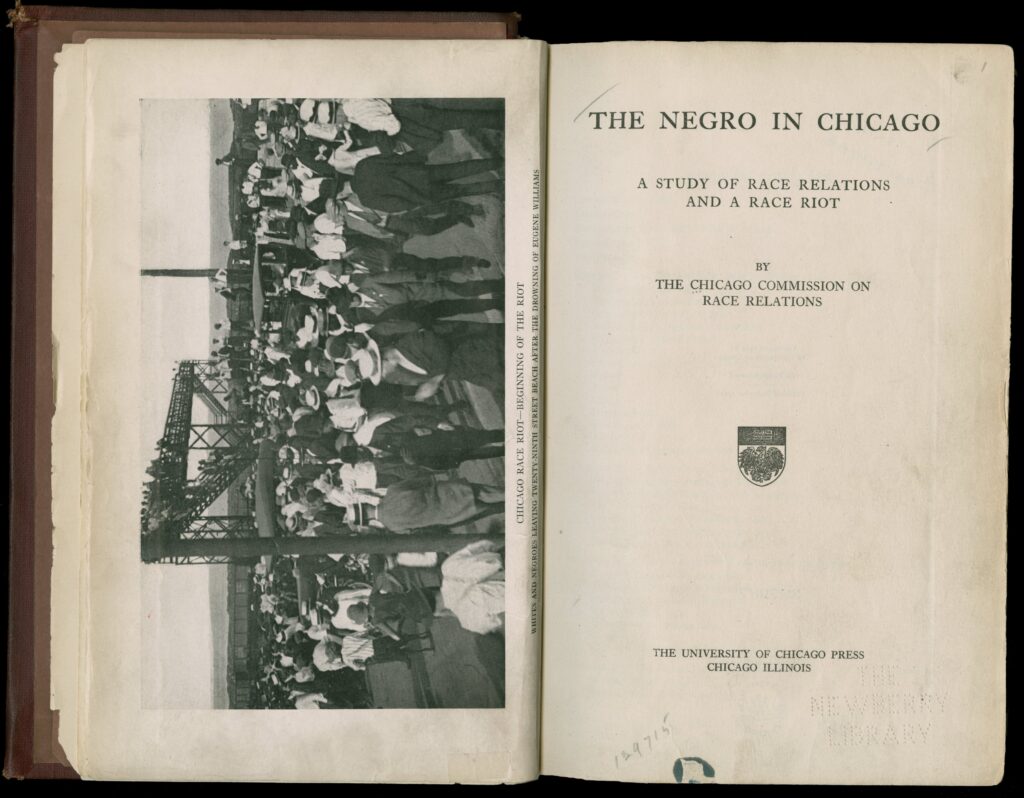

On July 27th, 1919, seventeen-year-old Eugene Williams was swimming in Lake Michigan when he crossed the unofficial racial barrier separating the 26th Street Beach (black) and the 29th Street Beach (white). George Stauber, a white beachgoer, threw a rock that hit Williams in the head. The boy drowned as a result of the attack. Although Williams’ friends identified Stauber, Officer Callahan of the Chicago Police Department refused to arrest him. Seeing this as the last straw, hundreds of black Chicagoans gathered at the beach to demand the police turn over both Stauber and Officer Callahan. The police refused and tried to disperse the crowd. Members of the African-American community refused to leave and rushed the perpetrator and the officer. This conflict resulted in fighting between whites and blacks across the city for days. Rumors spread that blacks were stockpiling weapons, breaking into armories, and drowning whites. For days, whites chased blacks down streets, pulled them off streetcars, set their houses on fire, and beat and killed them. Blacks killed whites in perceived and real instances of both retaliation and self-defense. In the end, thirty-eight people were killed, more than five hundred were injured, and a thousand black families were left without homes.

Discussion Questions:

- What events began the violence in July 1919? What are some underlying reasons why these events occurred?

- Looking at the photographs published in the Chicago Tribune and the Chicago Daily News, what kinds of damage do the newspaper accounts show? What kind of effect do you think this representation of the violence had on white readers of these newspapers? On black readers?

Quelling the Violence

In the last days of July 1919, both Chicago Mayor William Hale Thompson and Illinois Governor Frank Lowden refused to declare martial law. Each man planned to run for President of the United States and thought such a declaration would garner bad press and hurt a future campaign. Major Thompson increased the police presence in the city, shut down the major sites of integrated industry—such as the Chicago Stockyards—and declared a city-wide curfew. Civic groups, both black and white, called on those involved in the violence to stop. Several groups, including the Chicago Medical Association, the Urban League, and the Chicago Women’s Club, held a meeting at the Union League Club on August 1st to discuss ways to prevent this type of violence in the future. The Eighth Regiment, Chicago’s celebrated African-American army unit recently returned from World War I, campaigned to end the riots. But the violence did not stop, and the damage and casualties mounted as the riots continued into the week.

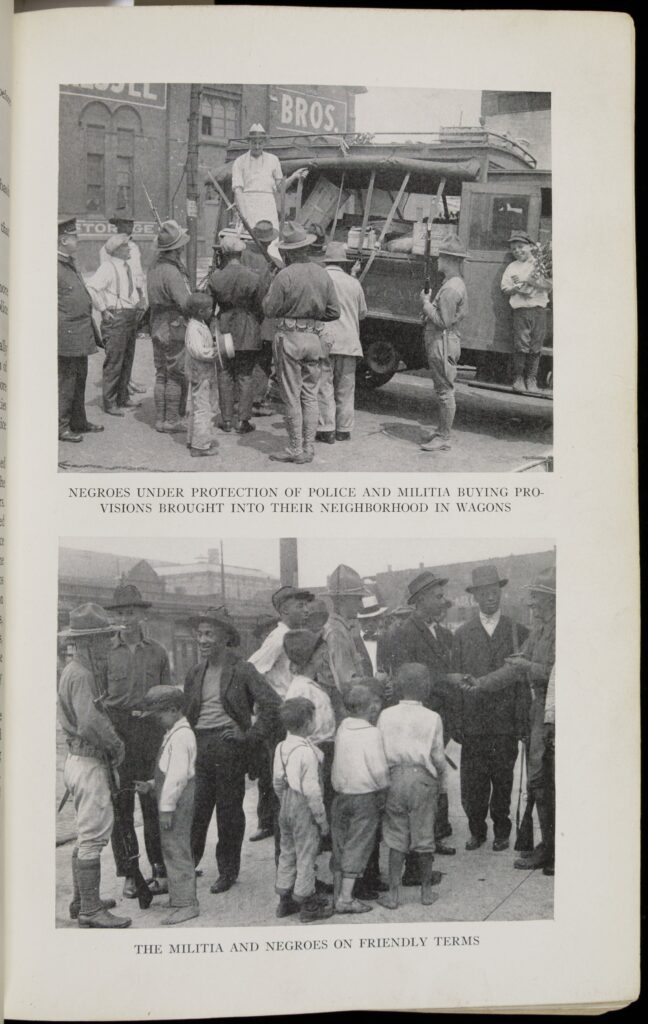

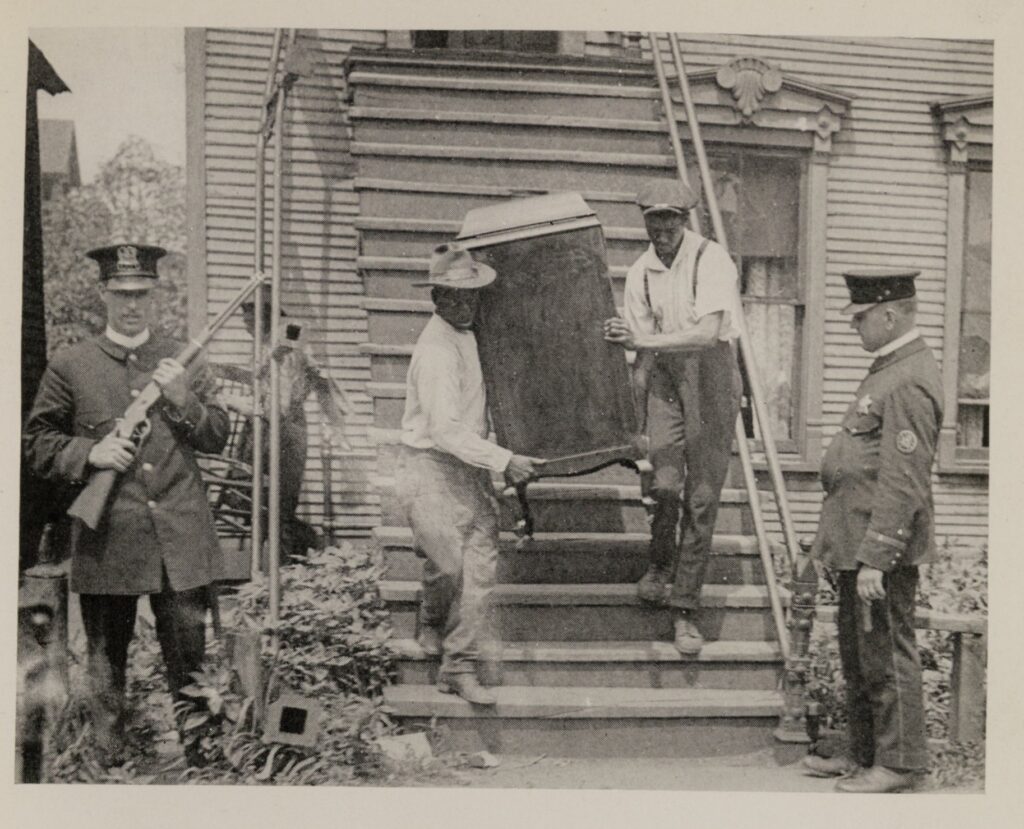

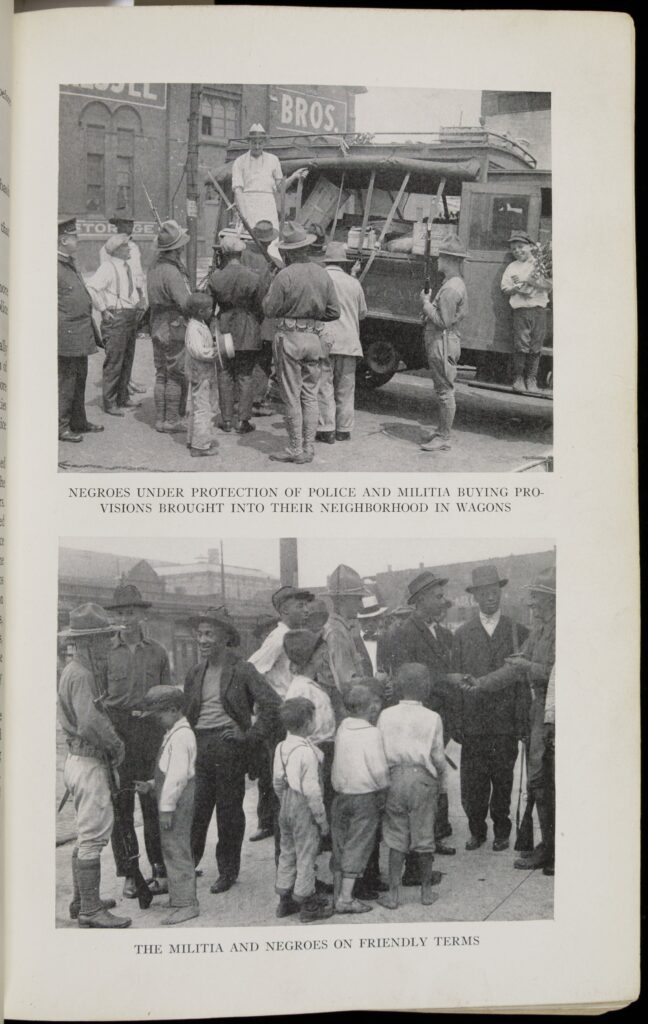

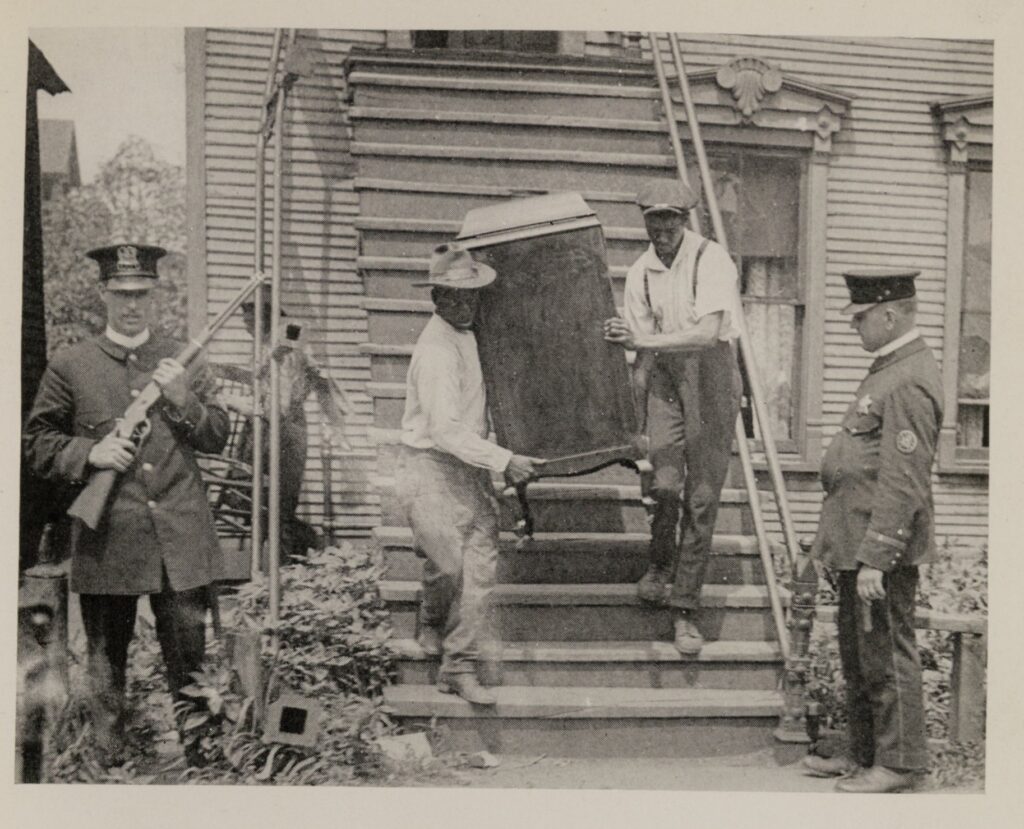

By the evening of July 30th, Mayor Thompson and Governor Lowden saw that military intervention was necessary. Governor Lowden sent in 6,000 troops from the Illinois National Guard. The troops sent in to disperse the riots in East St. Louis and Washington D.C. had terrorized black citizens. They assumed African Americans were the exclusive cause of the violence. In contrast, the troops in Chicago protected the black community. They refused to allow white Chicagoans into the Black Belt; they brought aid and supplies into the neighborhood; they helped black Chicagoans move from their damaged homes; they dispersed white gangs; and they negotiated with the management and workers at the Stockyards to coordinate black workers’ return to work. By and large, the riot was over by Friday, August 1st.

Discussion Questions:

- How did the militia react to being called in to quell the violence?

- Looking at how the troops were represented in these pictures, what kinds of support did they provide?

The Chicago Commission on Race Relations

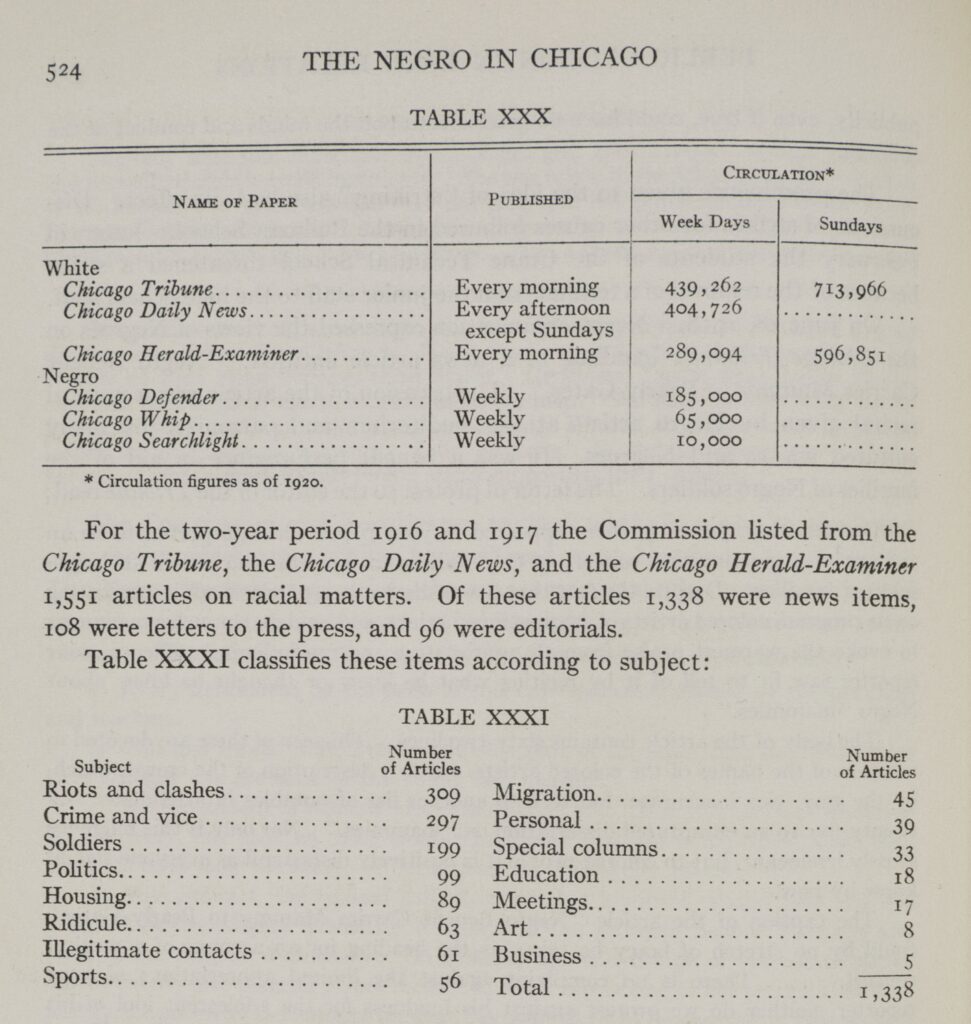

These charts from The Negro in Chicago

depict the biased reporting on the African-American Community in the Chicago daily newspapers.

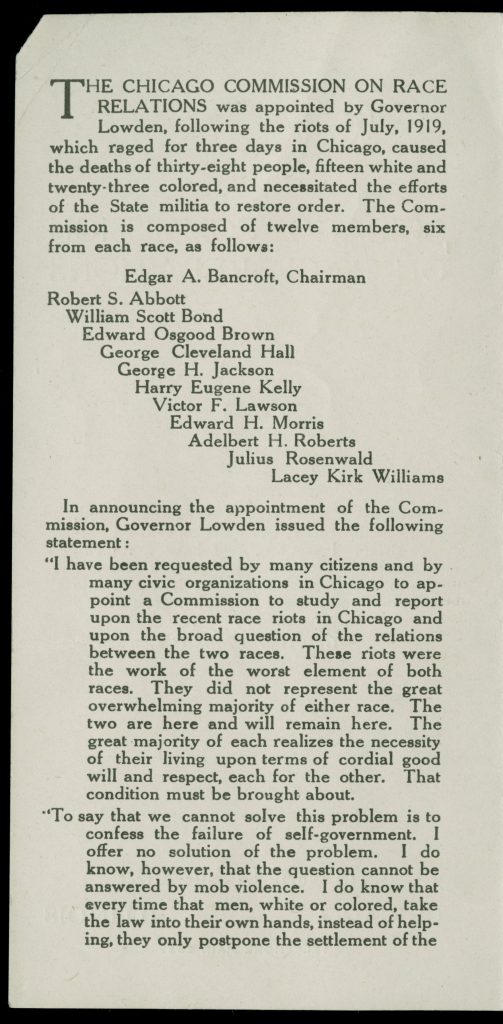

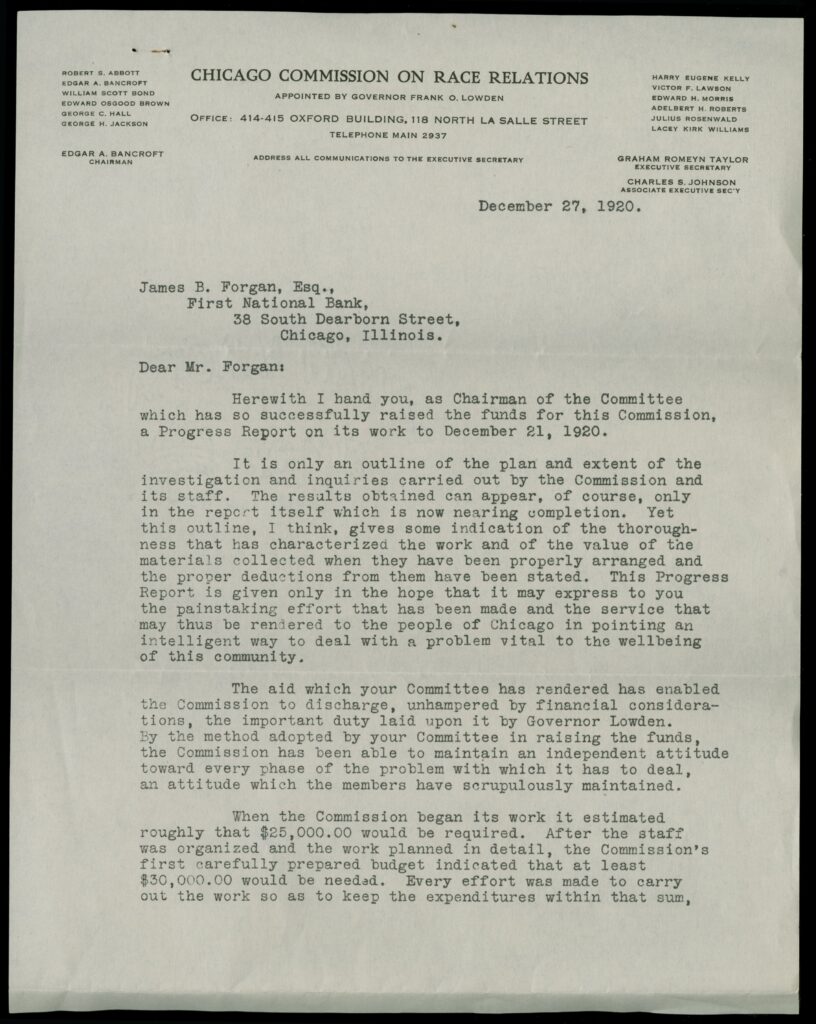

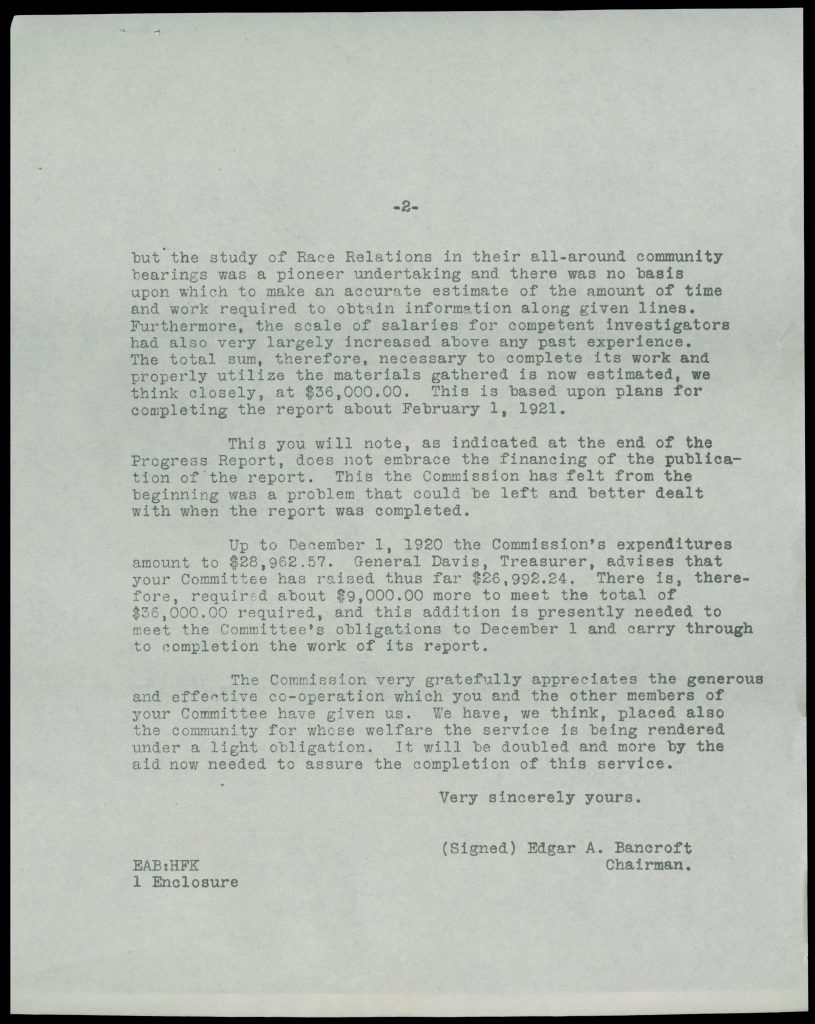

During and after the 1919 race riots in Chicago, multiple groups called for a formal investigation into the event. Responding to these requests, Governor Lowden commissioned a mixed-race committee to investigate. The twelve members were Edgar A. Bancroft (a white lawyer), Robert S. Abbott (the black founder and editor of the Chicago Defender), William Scott Bond, Edgar Osgood Brown (a white judge), George Cleveland Hall (a black physician), George H. Jackson (the black NAACP treasurer), Harry Eugene Kelly (a white lawyer), Victor F. Lawson (the white manager of the Chicago Daily News), Edward H. Morris (a black lawyer), Adelbert H. Roberts (a white Illinois congressmen), Julius Rosenwald (the white CEO of Sears Roebuck, and Co.), and Lacey Kirk Williams (a black minister). These men organized themselves into subcommittees to explore race conflict, housing, industry, crime and police administration, and public opinion. The group studied the issues for two years, and the University of Chicago Press published the final report in 1922.

Selection: Pamphlet issued by the Chicago Commission on Race Relations (1921)

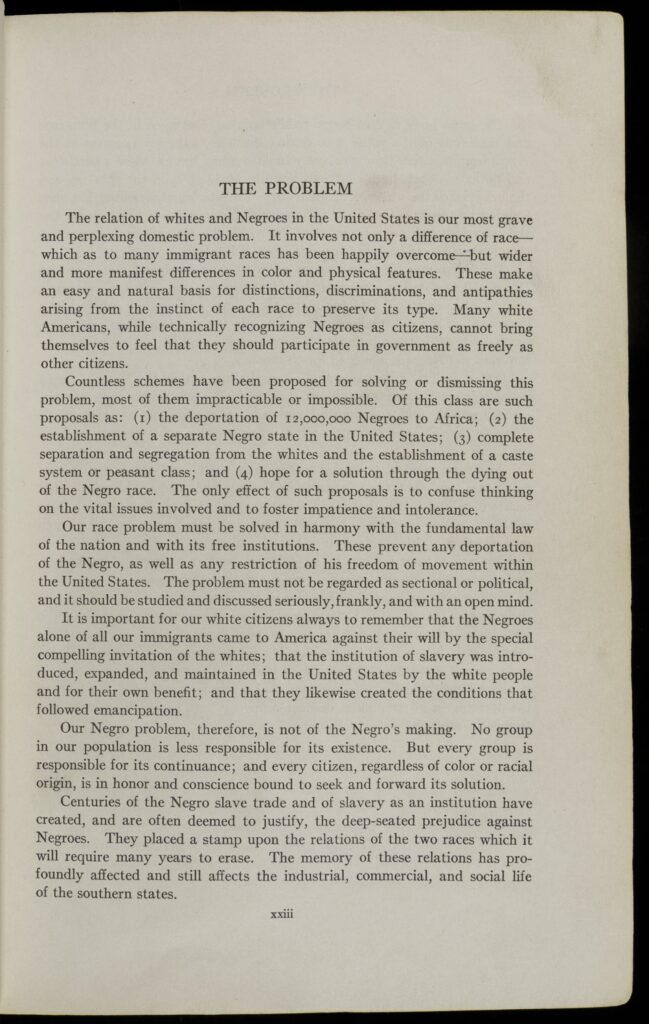

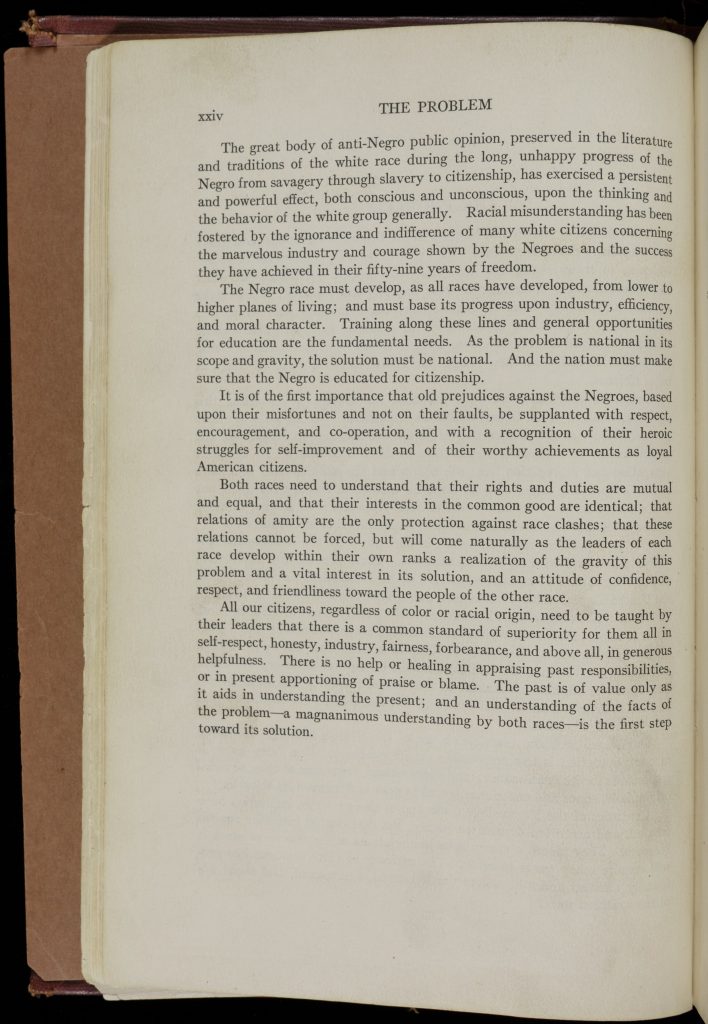

Titled The Negro in Chicago: A Study of Race Relations and a Race Riot, this report was over six hundred pages long and was a detailed account of early twentieth century Chicago African-American history. In addition to reporting on the lives, successes, and hardships of African Americans in Chicago, the report catalogued disparity between white and black Chicagoans in areas like city resources, housing, work conditions, job opportunities, and public opinion. Ultimately, the report demonstrated that the city’s neglect of its African-American population, coupled with some white Chicagoans’ extreme acts of exclusion, racism, and violence against the black community, caused the violence that summer. The findings of the report differed substantially from the major news outlets’ portrayal of the events in real-time, including the Chicago Tribune’s and Chicago Daily News’ multiple articles about unbridled and baseless black violence. The Negro in Chicago made clear that the race riots were the result of decades of inequality.

Selection: Chicago Commission on Race Relations, The Negro in Chicago, frontispiece and title page, frontispiece detail, “The Problem” (1922)

Discussion Questions:

- Why was the Chicago Commission on Race Relations established? Given the information we have about the Commission members, what kinds of expertise and perspectives do you think each contributed to this work?

- What is the significance of creating a committee comprised of both white and black members?

- What are some important contributions that the final report made to Chicago and the effort towards understanding race relations in the city?

Selection: Letter from Edgar Bancroft on the progress of the Chicago Commission on Race Relations (1920)

The Legacy

The violence in Chicago between whites and blacks in the summer of 1919 illustrated the realities of life for African-American migrants and suggested that white supremacy was an issue in the North as well as the South. Sadly, the legacy of the race riots suggested that black urban life in Chicago was connected directly to violence. But the violence and the city’s reaction to it—particularly that of the Illinois National Guard and the Chicago Commission on Race Relations—also showed a resilient African American community. At stake in the legacy of the event is the public negotiation of Chicago’s identity and the definition of municipal citizenship. Although the violence resulted in deaths, injuries, and destruction, it also showed that the African American community in Chicago had recourse to the government—be it local, state, or national—to demand full protection under the law. Because the National Guard honored the dignity of the African-American community and protected them during the riot, the violence ended. Furthermore, because the Chicago Commission on Race Relations took its task seriously, municipal leaders had to deal with the inequity blacks faced in Chicago in the early twentieth century. The Negro in Chicago not only recorded a pivotal moment in Chicago and American history, but it also endures today as a record of black life in a major American city.

The Commission’s recommendations called for more integration, black inclusion in labor unions, job opportunities for blacks, equal housing, and less biased press coverage. Chicago industries did integrate their unions. Furthermore, in 1925, Chicago’s Pullman Porters created the first all-black union: The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. But many of the Commission’s other recommendations took years to implement or were never implemented. For example, housing discrimination against African Americans remained until the Equal Housing Act in 1968. The Act did not result in a fully integrated city, however; once black homeownership became possible citywide, many white homeowners left the city for the suburbs to avoid having black neighbors (a phenomenon called “white flight”). Urban renewal policies in the 1960s and 70s further segregated Chicago neighborhoods by race, with two interstates (I-90 and I-94) creating a barrier between traditionally white and black neighborhoods on the city’s South Side. Despite the advances African Americans in Chicago made after the race riots, one hundred years later, Chicago remains segregated.

Discussion Questions:

- How do we talk about the 1919 race riots today? Why does it matter how we remember them?

- In what ways could The Negro in Chicago be used for further research?

Chicago Commission on Race Relations, The Negro in Chicago, “Distribution of Negro Population 1920″ (1922)

Chicago Commission on Race Relations, The Negro in Chicago, “Rear View of Houses,” 202-203 (1922)

Chicago Commission on Race Relations, The Negro in Chicago, “Recreation Facilities,” 272 (1922).

“A Call from Dixie,” Chicago Daily Tribune (August 4, 1919).

“City Problems,” Chicago Daily Tribune (July 29, 1919).

Chicago Commission on Race Relations, The Negro in Chicago, “Chicago Race Riot–Beginning of the Riot,” frontispiece (1922).

Chicago Commission on Race Relations, “The Chicago Riot: July 27 to August 8, 1919” (1922).

“This Boy’s Death Caused Race Riot,” The Chicago Defender (August 30, 1919)

“Action in the Black Belt–Some Riot Pictures,” Chicago Daily Tribune (July 31, 1919)

“Colored Injured and Traveling Refugees; House Wrecked by Rioter,” Chicago Daily News (July 30, 1919)

“Torch, Bullet, and Hoodlumism,” Chicago Daily Tribune (July 31, 1919)

“Veterans Campaign to End Race Rioting in Chicago,” Chicago Daily News (August 1, 1919)

Chicago Commission on Race Relations, The Negro in Chicago, “Scenes from Fire in Immigrant Neighborhood ‘Back of the Yards’“ (1922)

Chicago Commission on Race Relations, The Negro in Chicago, 40-41 (1922)

Chicago Commission on Race Relations, The Negro in Chicago, 16-17 (1922)

Chicago Commission on Race Relations, The Negro in Chicago, 252 (1922)

Chicago Commission on Race Relations, The Negro in Chicago, 26 (1922).

Chicago Commission on Race Relations, “Chicago Commission on Race Relations,” 1 (1921)

Chicago Commission on Race Relations, “Chicago Commission on Race Relations,” 2 (1921)

Chicago Commission on Race Relations, “Chicago Commission on Race Relations,” 3 (1921)

Chicago Commission on Race Relations, “Chicago Commission on Race Relations,” 4 (1921)

Chicago Commission on Race Relations, The Negro In Chicago, title page and frontispiece (1922)

Chicago Commission on Race Relations, The Negro in Chicago, “The Problem”, xxiii (1922)

Chicago Commission on Race Relations, The Negro in Chicago, “The Problem,” xxiv (1922)

Edgar A. Bancroft to James B. Forgan, 1 (December 27, 1920)

Edgar A. Bancroft to James B. Forgan, 2 (December 27, 1920)

Graham Taylor, “All Chicago Challenged by Race Riots,” Chicago Daily News (August 2, 1919).

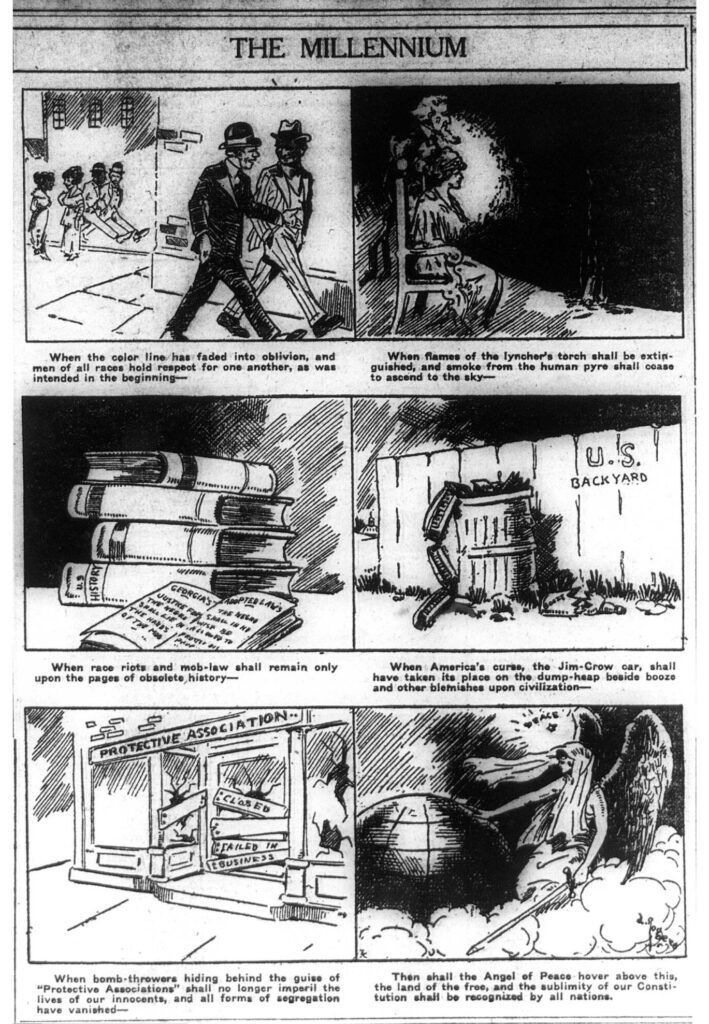

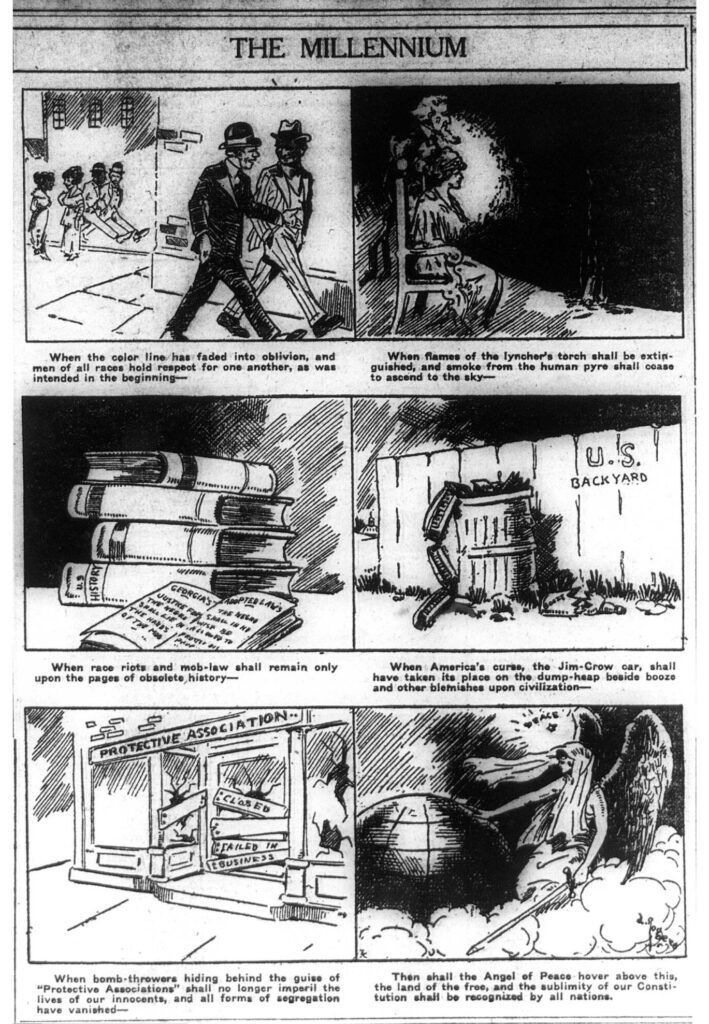

“The Millennium,” The Chicago Defender (January 17, 1920).

Further Reading

Baldwin, Davarian L. Chicago’s New Negros: Modernity, The Great Migration, and Black Urban Life. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Hartfield, Claire. A Few Red Drops: The Chicago Race Riot of 1919. New York, Clarion Books, 2018.

McWhirter, Cameron. Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black Americans. New York, St. Martin’s Griffin, 2011.

NAACP, “Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States.” Dallas, 1919.

Sandburg, Carl. The Chicago Race Riots, July 1919. New York:, Harcourt, Brace & World, 1969.

Tuttle, William M. Race Riot: Chicago in the Red Sumer of 1919. Champaign, University of Illinois Press, 1970.