Introduction

In 1789 the people of France began a revolution that would bring profound changes to their country’s political and social order. These changes came especially fast during the first six years: The Revolution started with the establishment of the National Assembly and plans to write a constitution that would limit, but not overthrow, the monarchy. A few years later, the king and queen, Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, would not only be deposed, they would be executed as traitors to the republic. Their fate was shared by hundreds of other leaders and activists, across the political spectrum, who were sent to the guillotine during the Reign of Terror in 1793 and 1794.

These tumultuous political events both reflected and contributed to fundamental shifts in notions of identity and authority in late-eighteenth-century France. Before the Revolution, the authority of the king derived from a centuries-old belief in “divine right.” As historian Lynn Hunt explains, most Europeans believed that “monarchs ruled because God had chosen them for their positions… Kings occupied the highest positions among humans on the great chain that stretched from God down through humans to all the lowliest creatures on earth.” Being closest to God, kings held the top rank in a hierarchical social order. Beneath them were aristocrats (people of noble birth), then merchants, then servants, and so on. Women held the rank of their fathers before marriage and their husbands afterward.

During the Revolution, political leaders attempted to persuade the French people that they were no longer subjects of the king, but citizens who had the right to participate actively in their own government.

In eighteenth-century France, Enlightenment thinkers such as Denis Diderot and Jean Jacques Rousseau introduced an entirely different way of thinking about rights and authority. Their ideas were not based on a sense of divinely ordained hierarchy. Instead, they drew on the concept of natural law: rights that people held simply because they were people. As Diderot wrote, “I am a man, and I have no other true, inalienable natural rights than those of humanity.” Enlightenment philosophers did not always specify what those rights were, but many seem to have shared a belief in the rights to life, liberty, and property. Most importantly, the idea of natural law depended on a sense of fundamental human equality. According to natural law, no one, including the king, was born innately superior to anyone else. Before the Revolution, such ideas were considered threatening to the monarch and could lead to censorship, imprisonment, exile, or execution. During the Revolution, political leaders attempted to implement these ideas by establishing political structures which followed natural law and by persuading the French people that they were no longer subjects of the king, but citizens who had the right to participate actively in their own government.

The following collection of sources speaks to some of the ways that French people brought about—or resisted—the transition from monarchy to republic and from subject to citizen. The press played an enormous role during the Revolution, despite ongoing censorship. From the beginning, writers of all political persuasions expressed themselves in pamphlets that shaped public opinion and subsequent political events. The Revolution also had implications for how people understood social customs that we don’t notmally associate with politics: fashion, music, and even baby names. The documents below convey some of these less predictable areas of experimentation and change alongside the explicitly political debates.

Please consider the following questions as you review the documents:

- How did French writers and artists represent the king and the country’s traditional hierarchy before and during the Revolution?

- What did citizenship mean in the new republic?

- How did ordinary people as well as the government use print publications to influence events during the Revolution?

- What impact did the political ideals of the French Revolution have on social customs?

Representing the Monarchy and Aristocracy

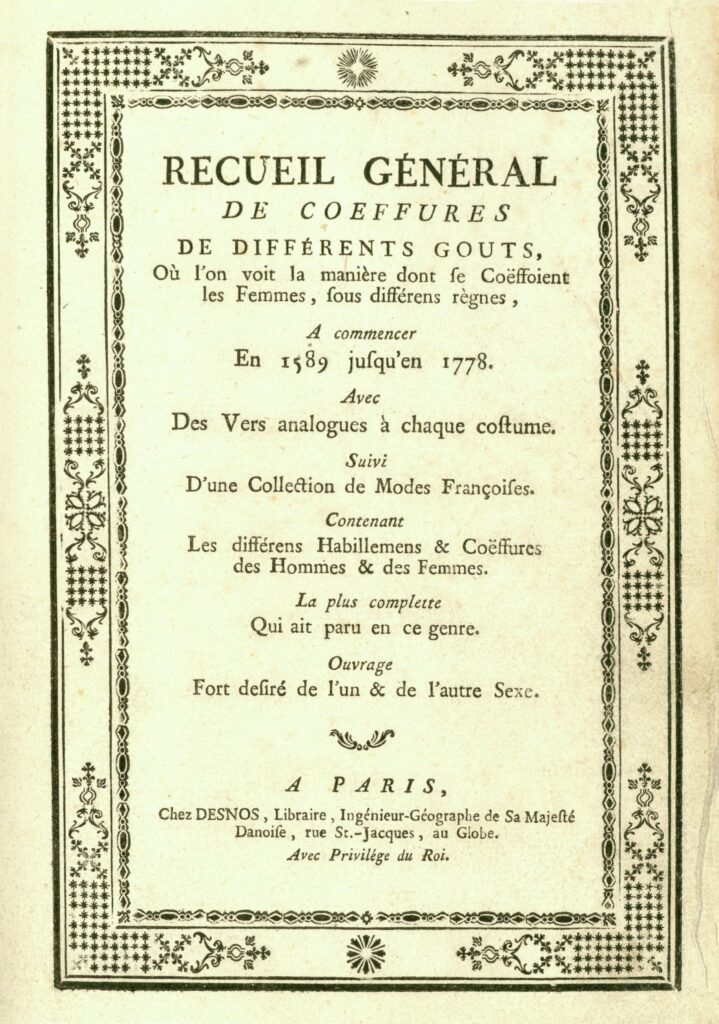

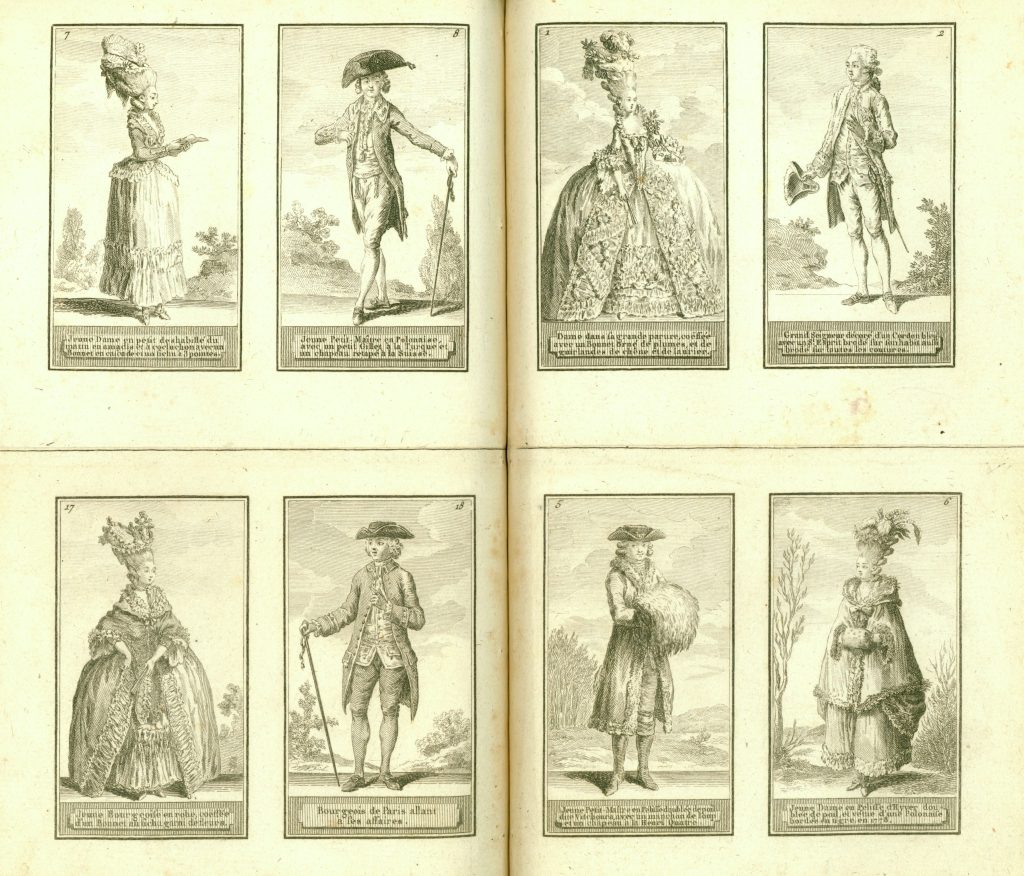

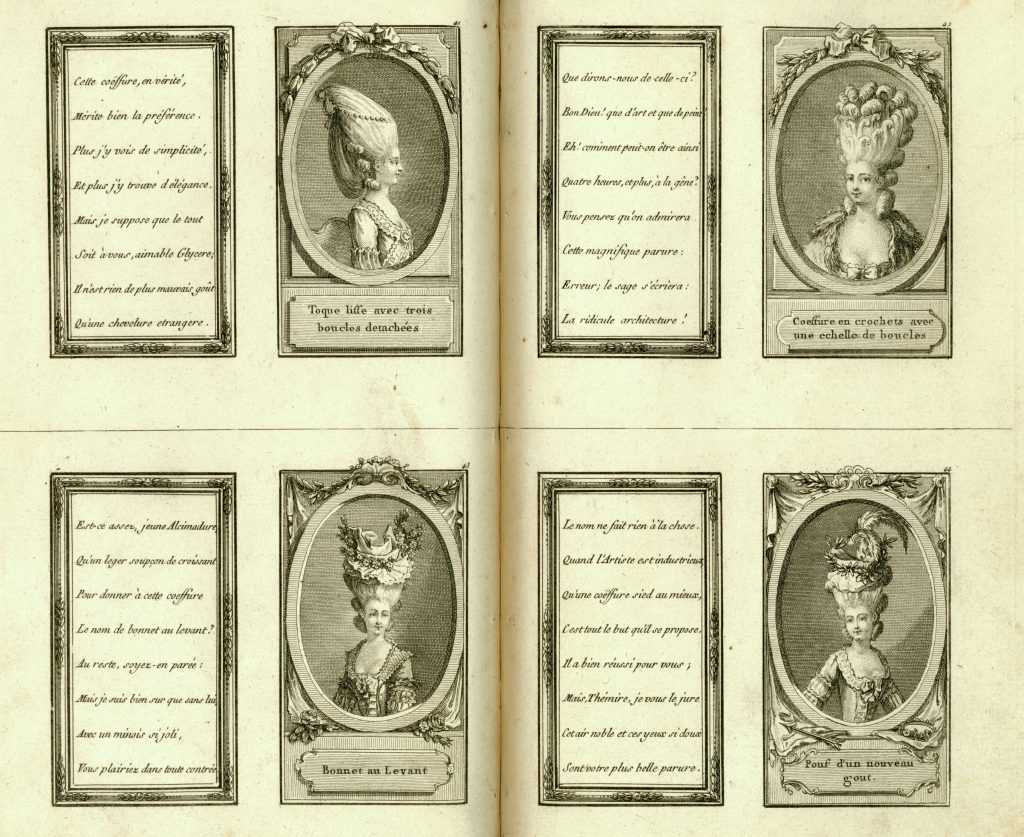

French monarchs and aristocrats were the subject of both reverence and derision in the years before and during the French Revolution. The following documents offer vivid contrasts in how they were portrayed. The first illustrations were published in 1778 in Recueil Général De Coeffures De Différents Gouts (“General Collection of Different Tastes in Hairstyles”), a work that devoted special attention to fashions at the court of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette.

Recueil général de coeffures de différents gouts [Collection of Hairstyles of Different Tastes], title page, 23, 27 (1778)

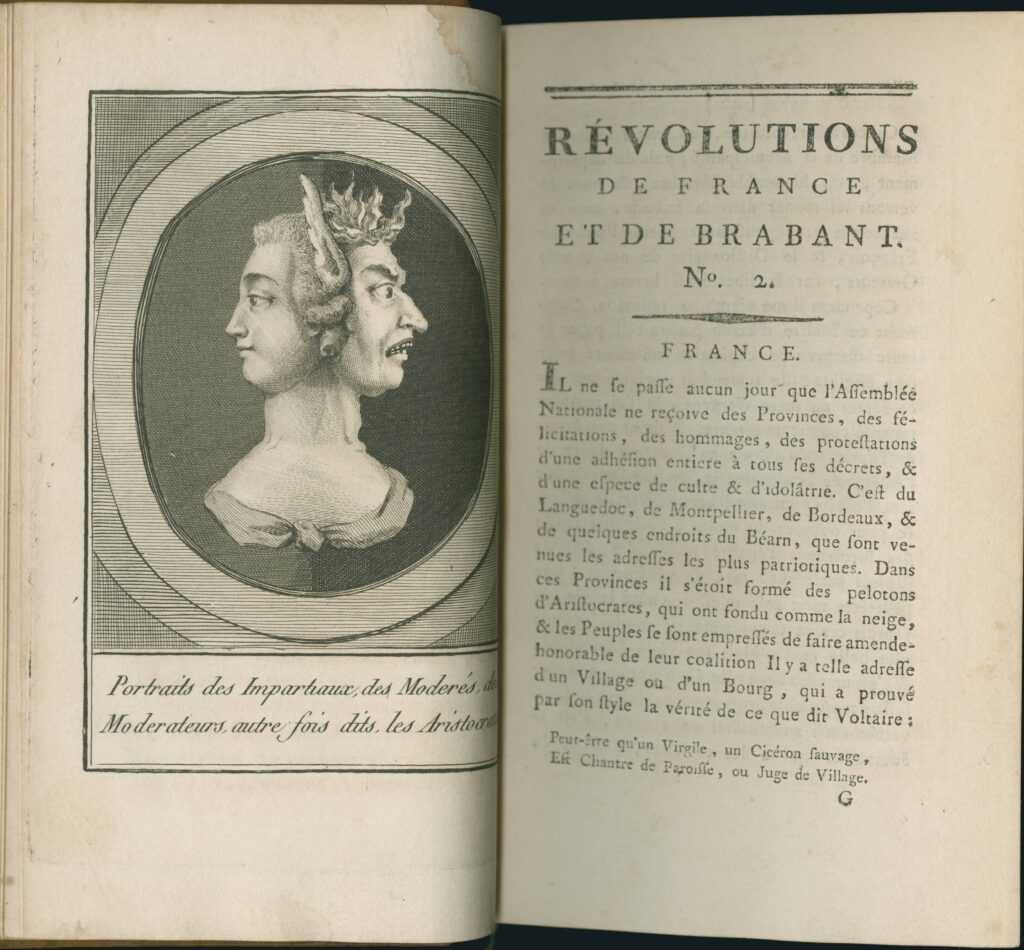

The second document is taken from a lively republican newspaper, entitled “Revolutions in France and Brabant,” published during the first years of the Revolution. Brabant refers to a Belgian province that was part of the Austrian Netherlands and revolted against Habsburg rule at the same time as the French Revolution. The author, Camille Desmoulins, was one of the Revolution’s leading pamphleteers, and was later guillotined during the Reign of Terror. The caption under the illustration reads: “Portraits of the Impartial, the Moderates, and the Moderators, also known as the Aristocrats.”

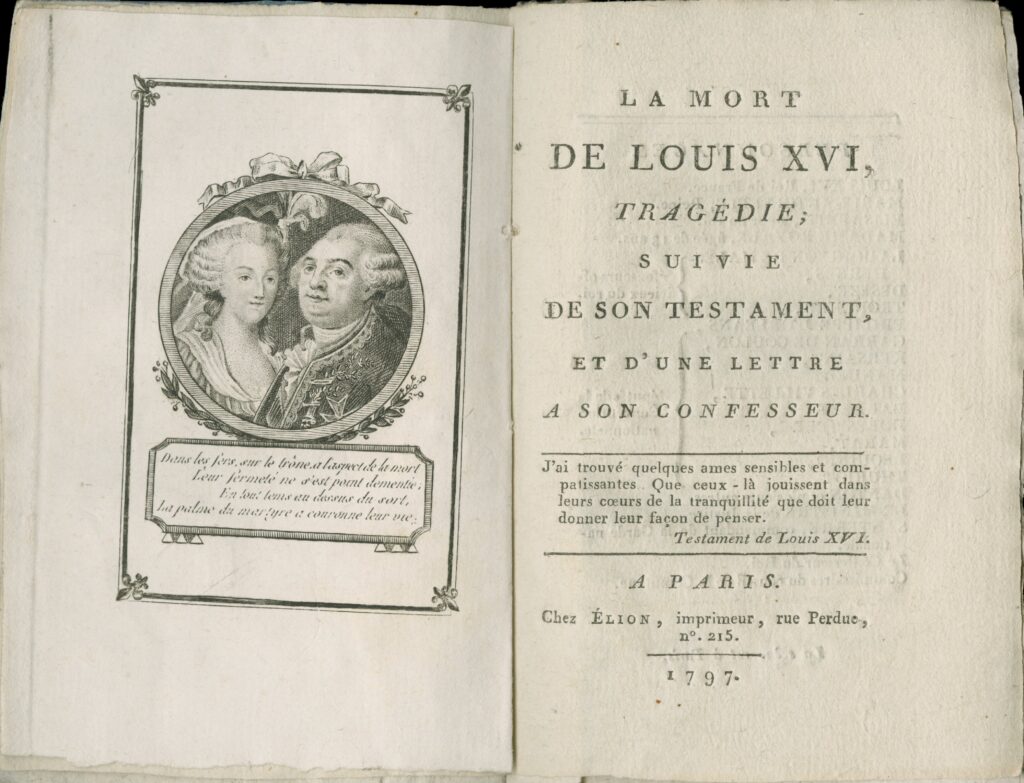

The final document is an anonymously written play, “The Death of Louis XVI: Tragedy,” that portrays the trial and execution of the king. This edition includes the text of Louis XVI’s will as well as an account of the 1795 trial and acquittal of two booksellers who had been charged with trying to harm the National Assembly by selling works such as this.

Questions to Consider:

- Describe the hairstyles and fashions portrayed in the “General Collection of Hairstyles.” What kind of time and effort do you think would be involved in creating one of these styles? What would it be like to wear one? How would it affect your ability to move around? Why do you think such styles were popular under Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI’s reign? What would wearing such a hairstyle communicate to other aristocrats or to other people in general?

- Why does the aristocrat portrayed in Revolutions de France et de Brabant have two faces? What is the significance of the association made in the caption between aristocrats and moderates? What political argument does this illustration make?

- How do Louis and Marie Antoinette appear in the engraving and caption in La Mort de Louis XVI (“The Death of Louis XVI”)? How does this representation compare to those in the previous two documents?

Women and Citizenship

In the summer of 1789, the deputies of the Third Estate (that is, everyone who was not a noble or a cleric) declared themselves the true representatives of the nation. They established, for the first time in French history, a National Assembly. The first task of the National Assembly was to write a constitution that would form the basis of a new government. However, many believed that even before the constitution could be drafted, the assembly needed to lay out the fundamental principles of government. After six days of debate, the assembly produced “a solemn declaration [of] the natural, unalienable, and sacred rights of man.” It would be four more years (and many political lifetimes) before the National Assembly published the constitution and founded the First French Republic in 1793. But the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen was enormously influential—and widely debated—from the time of its creation.

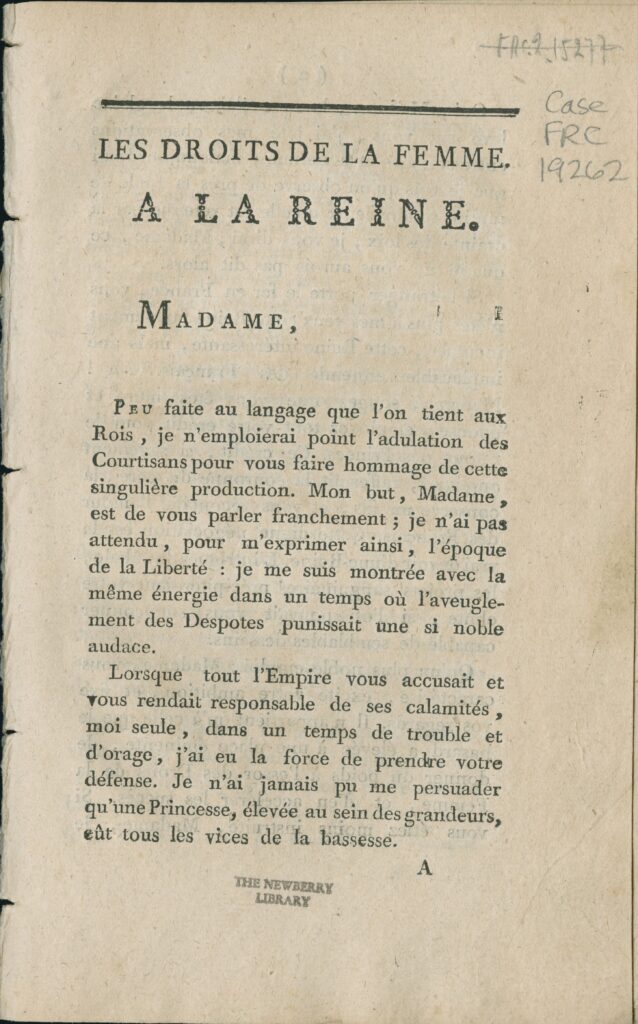

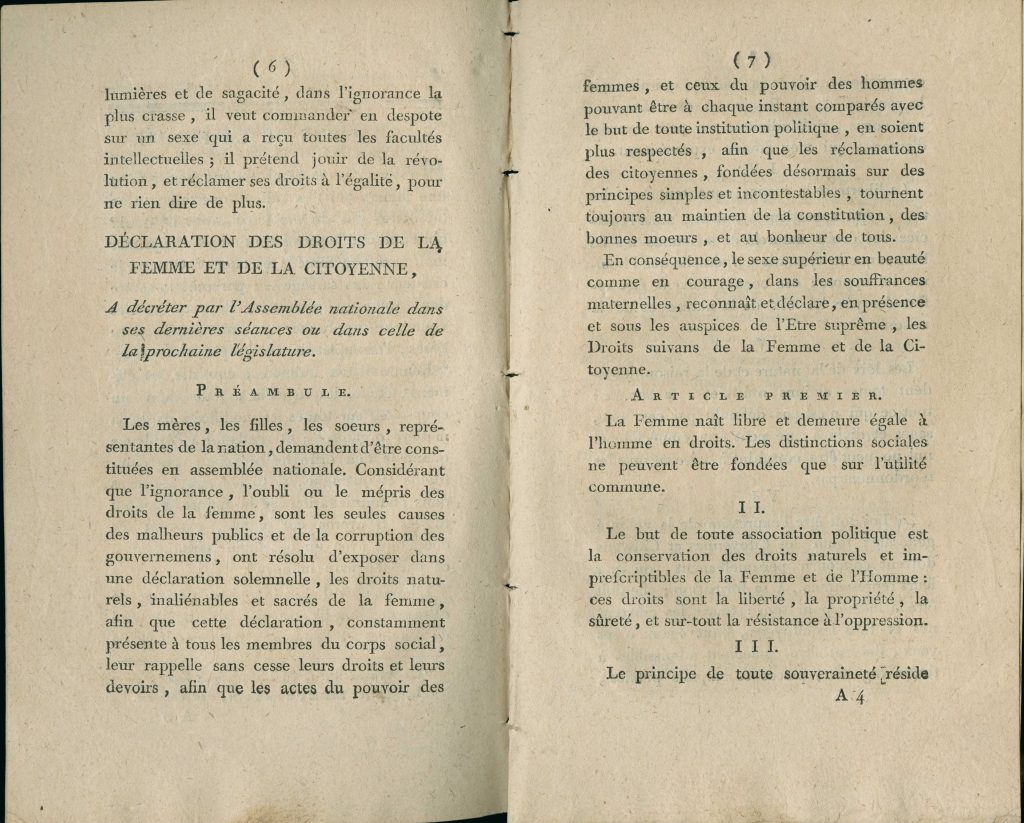

The Declaration’s first article reads, “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights.” As historian Lynn Hunt notes, this first statement frames the Declaration’s principles as universal and, as a result, immediately raised the question, “Who was included in the definition of a ‘man and citizen’?” Over the next five years, French writers and politicians engaged in passionate debates over the status of people who had, historically, been excluded from the rights of citizens: slaves and free blacks in the French colonies; religious minorities, such as Jews and Protestants; members of disreputable professions, such as executioners and actors; and women. Marie Gouze (known by the pen name Olympe de Gouges) offered a succinct response to this question on behalf of the last group. In 1791 she published The Rights of Woman. While Gouges was not the only one to argue for including women in the “rights of man,” most political leaders and writers strongly disagreed. Two years after publishing The Rights of Woman, Gouges was executed as an opponent of the government during the Reign of Terror.

Olympe de Gouges, Les droits de la femme: à la reine [The Rights of Woman: To the Queen], 5-7 (1791)

Above are excerpts from The Rights of Woman, which Gouges dedicated to the queen and prefaced with questions such as, “Man, are you capable of being just?… What has given you the right to oppress my sex?”

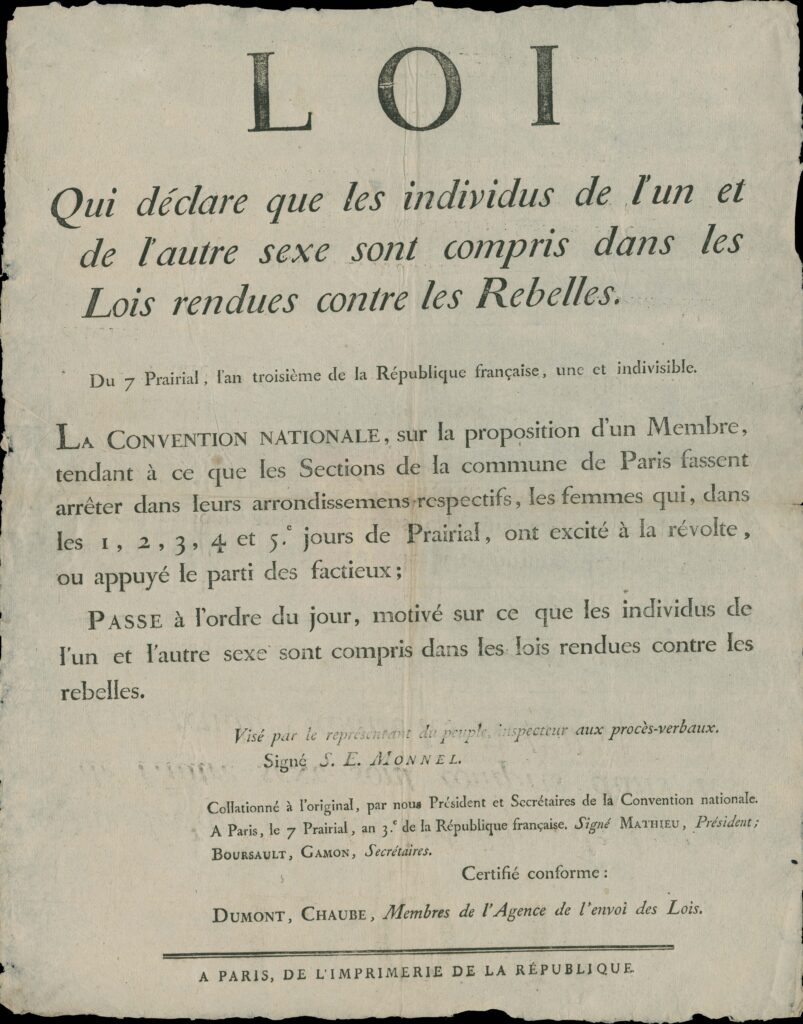

The document below is a broadside, issued by the French Republic in 1795. It proclaims a “Law Declaring that Individuals of Both Sexes are Included in the Laws against Rebels.” As Gouges’ experience shows only too well, women’s exclusion from political rights did not save them from prosecution for political crimes.

Questions to Consider:

- What changes does Gouges make to the original Declaration of the Rights of Man? Why do you think she chooses to adhere so closely to its form?

- Why do you think Gouges chose to dedicate her declaration to Marie Antoinette?

- Why would the republican government have felt compelled to announce that both women and men could be prosecuted as rebels? What does this suggest about women’s activities during the Revolution?

Pamphlet Wars

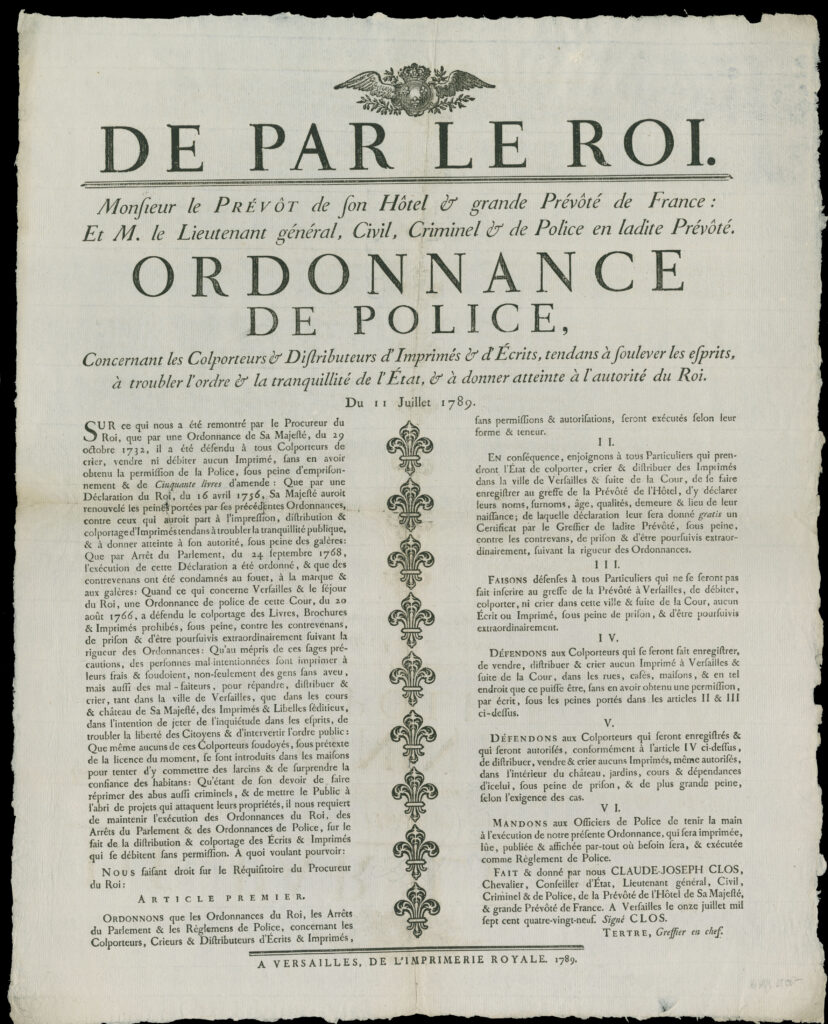

The documents in this section offer a glimpse of the vigorous use of the press by all political groups during the French Revolution. Through the broadside, “On Behalf of the King…Police Ordinance about Hawkers and Distributors of Printed Materials,” the French police attempted to stanch the flow of unregulated publications, which, they believed, “trouble[d] the order and tranquility of the State.” Published on July 11, 1789, this ordinance was posted just three days before the storming of the Bastille prison, a critical turning point in the early French Revolution.

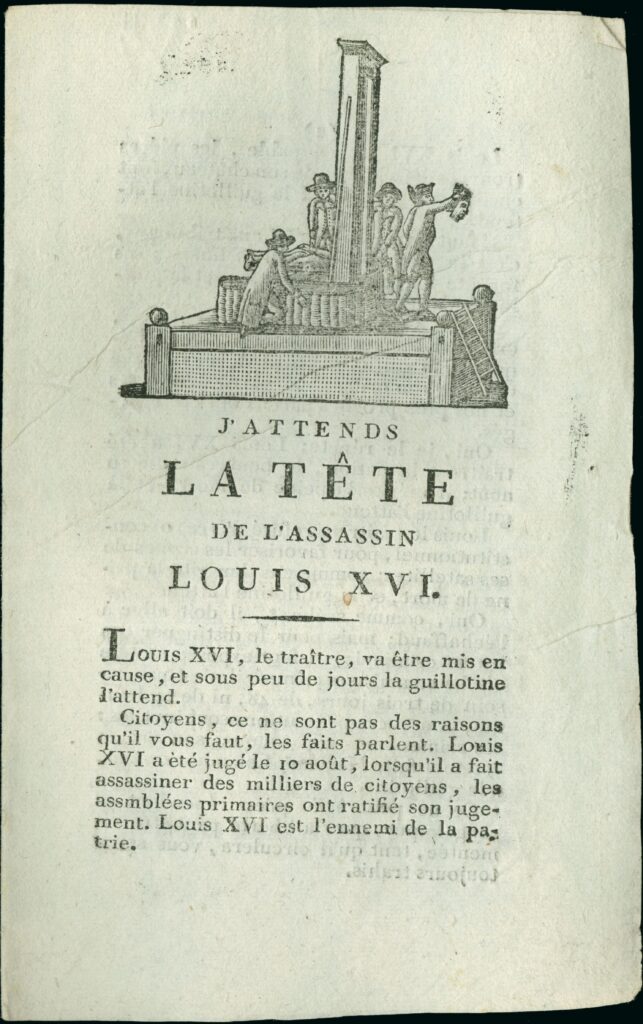

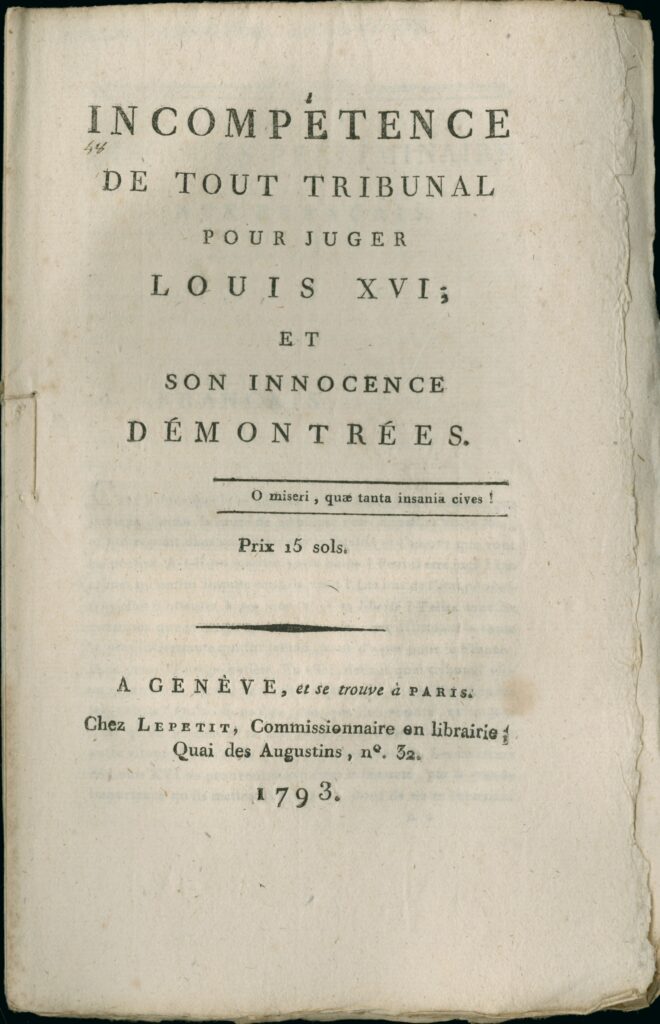

The two pamphlets that follow offer contrasting assessments of Louis XVI’s trial and execution. The National Assembly abolished the monarchy at the end of 1792. The following year, the deputies tried the king for treason and sentenced him to death. The first, “J’attends la tête de l’assassin Louis XVI,” translates as “I Wait for the Head of the Assassin, Louis XVI.” The second pamphlet asserts the “Incompetence of Any Tribunal to Judge Louis XVI” and offers to demonstrate his innocence.

Questions to Consider

- What are some of the different purposes that publications served during the Revolution, as demonstrated by these documents?

- Examine the illustration at the top of “I Wait for the Head of the Assassin, Louis XVI.” What does this anti-Louis pamphlet suggest about the political climate in 1793? Could you imagine a similar document being published—or posted on a website—today?

- Why might the author of the last pamphlet consider “any tribunal” unqualified to judge the king?

Revolutionary Style

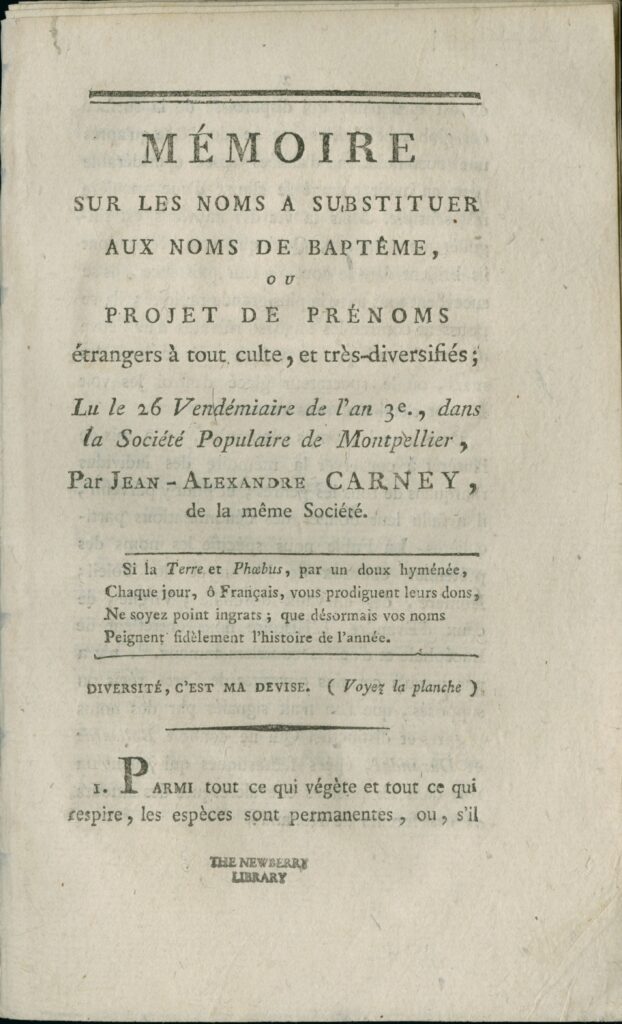

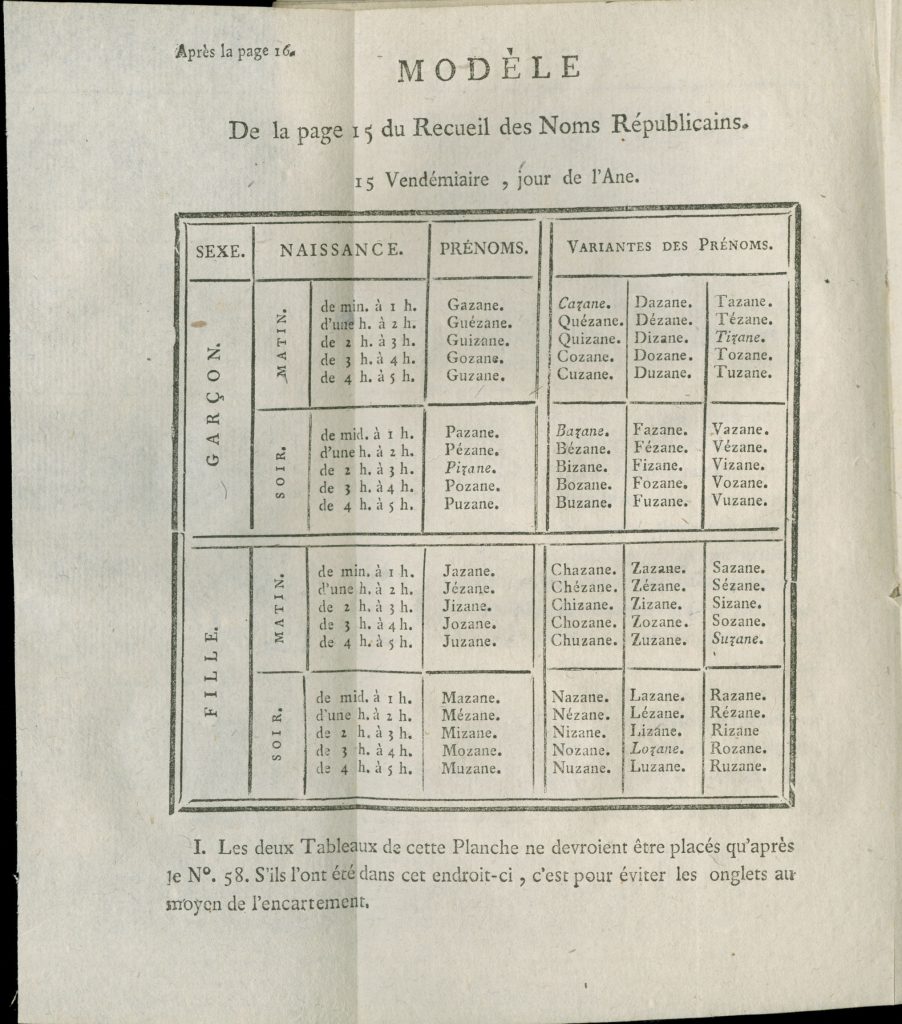

Many supporters of the Revolution believed that the fulfillment of republican political ideals required a transformation of social practices not normally associated with politics. Some of the most radical republicans urged a de-Christianization of French life. In 1793 the National Assembly voted to discard the Gregorian calendar and establish a new dating system, based on the founding of the republic rather than the birth of Jesus Christ. In a similar spirit, Jean-Alexandre Carney of Montpellier offered a system of naming to replace the French custom of naming a baby for the saint whose name was associated with the day of the year on which the baby is born. Carney argued that his system would allow for greater creativity and individuality in naming.

Jean Alexandre Carney, Mémoire sur les noms a substituer aux noms de baptême [System of Names to Replace Baptismal Names], title page and “Modèle” 1794

Names in this system are based on the day and the hour when the baby was born as well as on the child’s gender. The pamphlet includes tables which set up model naming schema for certain days of the year, such as 14 fructidor, otherwise known as the day of the nut. The names designated for each hour all contain the suffix “noix” for nut, and the table shows the appropriate name for each hour when the baby is born. For example, a boy born between 3 and 4 in the morning should be named Gonoix while a girl born between 4 and 5 in the afternoon should be named Munoix. It’s not clear whether anyone embraced Carney’s naming system. The Republican calendar was discarded by Napoleon in 1806.

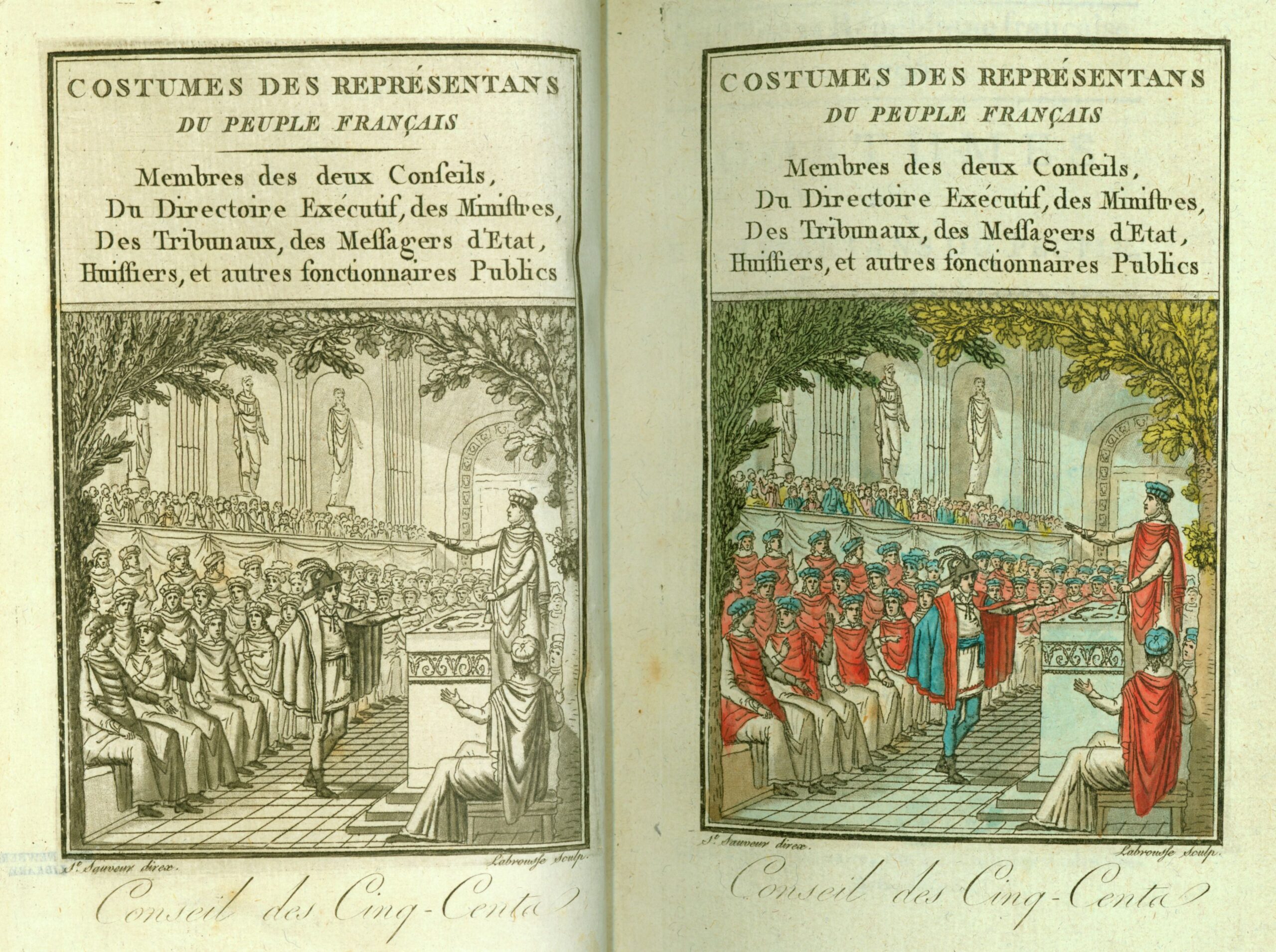

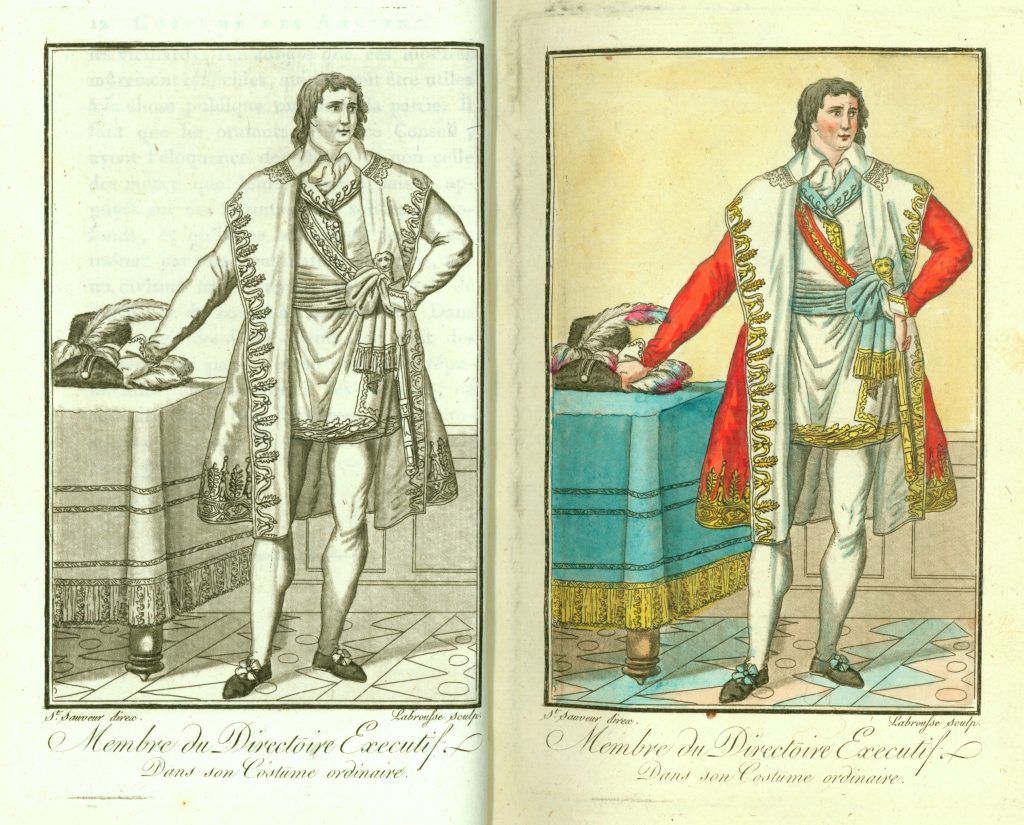

The illustrations by Saint-Saveur in “Costumes of Representatives of the People, Members of the Two Councils, the Executive Director…” suggest how, even after the Revolution, the notion that dress marked the ruler persisted. Neoclassical robes were considered ideal for the officers of the republic.

Jacques Grasset de Saint-Sauveur, “Costumes des représentans du peuple [Costumes of Representatives of the People]” and “Membre du Directoire Executif [Member of the Executive Board]” (1796)

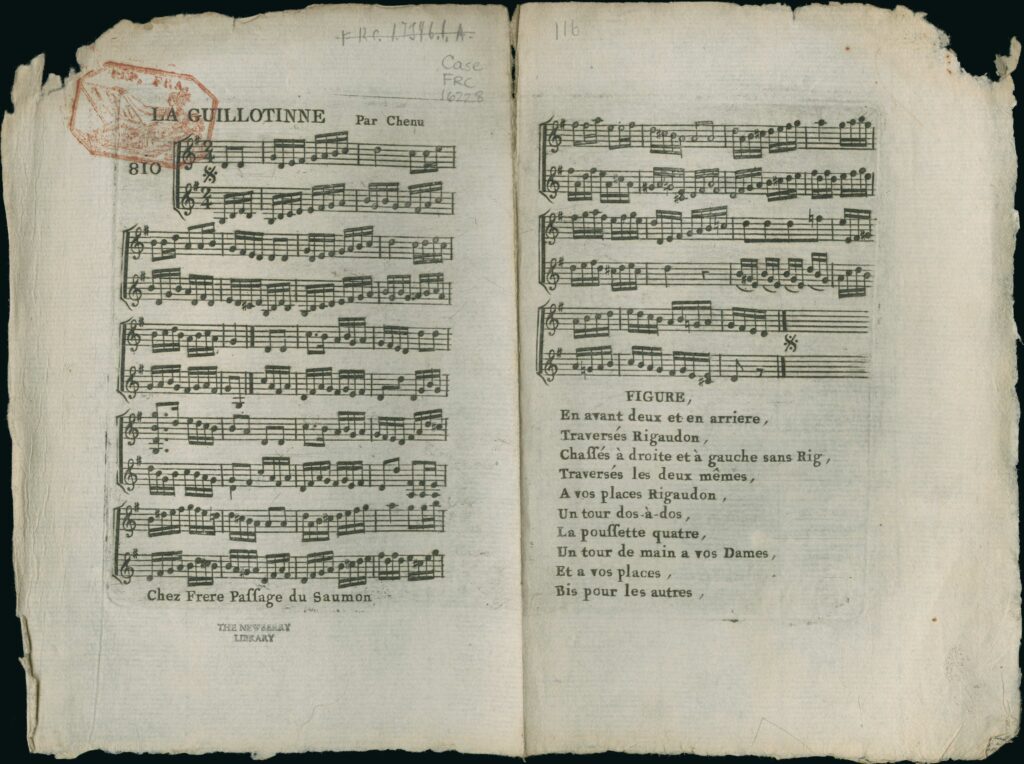

Finally, “The Guillotine” is an example of French sheet music from the 1790s. The text on the lower right side describes dance steps.

Questions to Consider:

- Why were some participants in the Revolution interested in changing such everyday and apparently nonpolitical customs as the calendar and baby names? Do you think that changes to these aspects of social life could make people better citizens?

- What do the costumes of the National Assembly members tell us about political ideals in 1796? Why would French republicans emulate the styles of ancient Greece and Rome? How do these styles compare to those worn by aristocrats in the “Collection of Hairstyles,” the first document in this collection?

- What does the song “The Guillotine” suggest about popular attitudes toward this widely used method of enforcing political control? What relationships do you see between the existence of this song and the pamphlet, “I Wait for the Head of the Assassin, Louis XIV,” included in the previous section?

Representations of the Monarchy and Aristocracy

These documents offer contrasting illustrations of how French monarchs and aristocrats were portrayed in the years leading up to and during the Revolution.

Women and Citizenship

Olympe de Gouges’s The Rights of Woman argued for the right of women to be extended the rights of citizens set forth in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. Despite their exclusion from political rights, as this broadside issued by the French Republic in 1795 made clear, women could be prosecuted for political crimes.

Pamphlets and Public Opinion

These documents provide a glimpse into the robust use of the press by political actors during the Revolution and the important role of print culture and public opinion to the Revolution’s unfolding.

Revolutionary Attitudes

As these documents reveal, some supporters of the Revolution viewed altering various aspects of social life and maintaining political control by violent means as necessary for the fulfillment of republican political ideals.

Further Reading

Bell, David A. “National Language and the Revolutionary Crucible.” In The Cult of the Nation in France: Inventing Nationalism, 1680-1800. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Gehl, Paul F., curator. Newberry Digital Exhibitions: The Many Faces of Marie Antoinette. http://publications.newberry.org/digitalexhibitions/exhibits/show/marie/intro.

Grzegorski, Jessica and Jennifer Thom, curators. Newberry Spotlight Exhibit: Politics, Piety, and Poison: French Pamphlets, 1600–1800.

Hunt, Lynn. “Introduction: The Revolutionary Origins of Human Rights.” In The French Revolution and Human Rights: A Brief Documentary History, edited and translated by Lynn Hunt. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 1996. 1–32.