Introduction

To twenty-first-century Americans, the case against slavery may appear self-evident. Most of us have no doubt about the profound injustice of a system in which some people are the property of other people. However, nineteenth-century opponents of slavery faced a quite different social consensus on the issue. They had to make the case for abolishing an institution that dominated the economic and social structure of the Southern states. They also had to address widespread anxiety about how the nation would integrate freed slaves into its social, political, and economic fabric. The documents that follow bring together arguments for emancipation written before, during, and after the Civil War. The collection allows students to trace the evolution of abolitionist arguments as well as to examine conflicts among writers over what emancipation would entail.

- What arguments did writers make before the Civil War for the abolition of slavery? How did they frame their appeals in moral, social, political, and economic terms?

- How did the war’s purpose shift from “saving the union” to destroying slavery?

- What would freedom mean for former slaves, for Southern society, and for the nation as a whole, according to various writers both before and after the war?

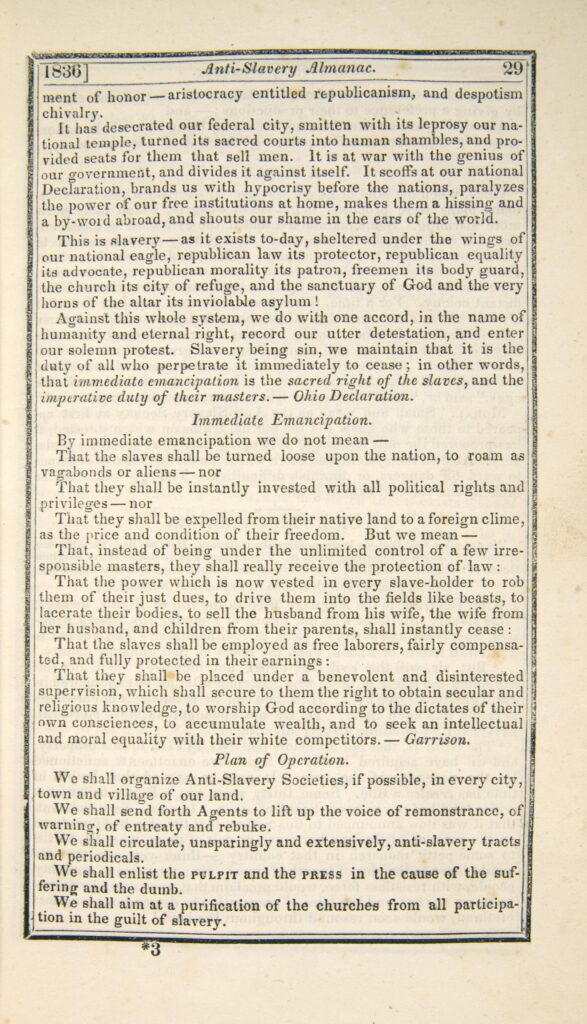

William Lloyd Garrision’s Call for Immediate Emancipation

During the nineteenth century, almanacs were very popular publications, widely read and used by literate Americans. Each year, the American Anti-Slavery Society distributed an almanac containing poems, drawings, essays, and other abolitionist tracts. The intent of the almanac was to instruct readers in the horrors of slavery and to persuade them to join the abolitionist cause. William Lloyd Garrison was a prominent abolitionist and the founder and publisher of the Liberator, an antislavery newspaper published between 1831 and 1865.

Questions to Consider

- Garrison begins his description of “immediate emancipation” by telling his audience what the term does not mean. Why would he use this rhetorical device? What objections to emancipation does Garrison anticipate from his readers?

- According to Garrison, what will be the results of emancipation? Would freed slaves achieve full equality with whites?

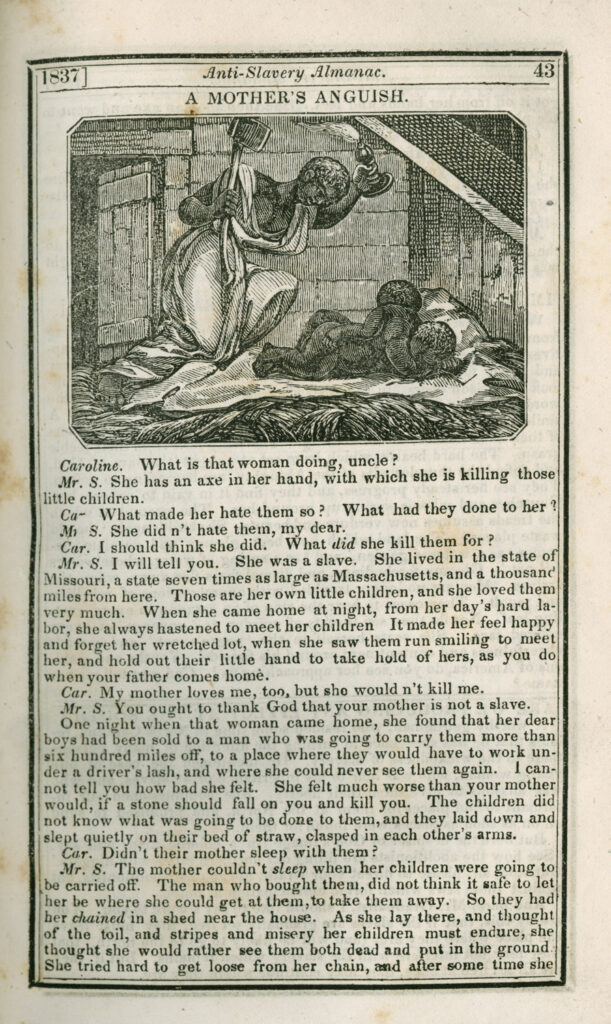

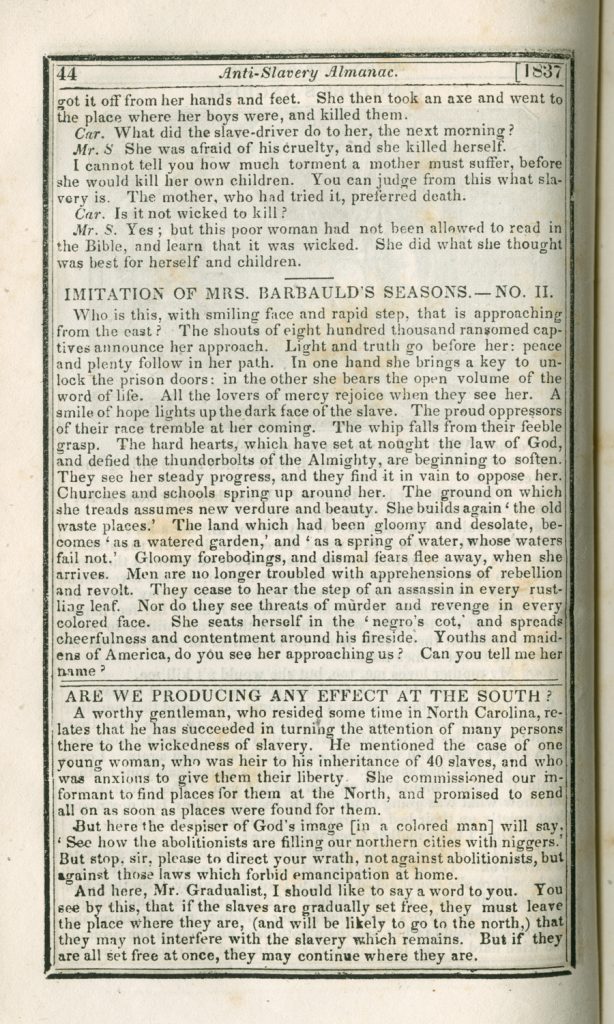

Anti-Slavery Literature

Antislavery literature often portrayed the deliberate destruction of black families under the institution of slavery. Slaves’ marriages were not legally recognized and people could be sold away from their spouses, children, and siblings at their owners’ wills. The following piece addresses the trauma that slavery inflicted on families through the story of a slave who murders her children to prevent their being sold. A similar story served as the basis for Toni Morrison’s contemporary novel, Beloved.

Selection: Anti-Slavery Almanac, “A Mother’s Anguish,” 43-44 (1837).

Questions to Consider

- Describe the portrayal of the slave mother in both the story and the image.

- How does the story represent the choices faced by the mother and the decision that she makes?

- While he acknowledges the horror of infanticide, Mr. S attempts to justify to his niece—and the readers—the actions taken by the slave mother. What arguments does he make?

- How does this story support the arguments for emancipation voiced by groups such as the Anti-Slavery Society?

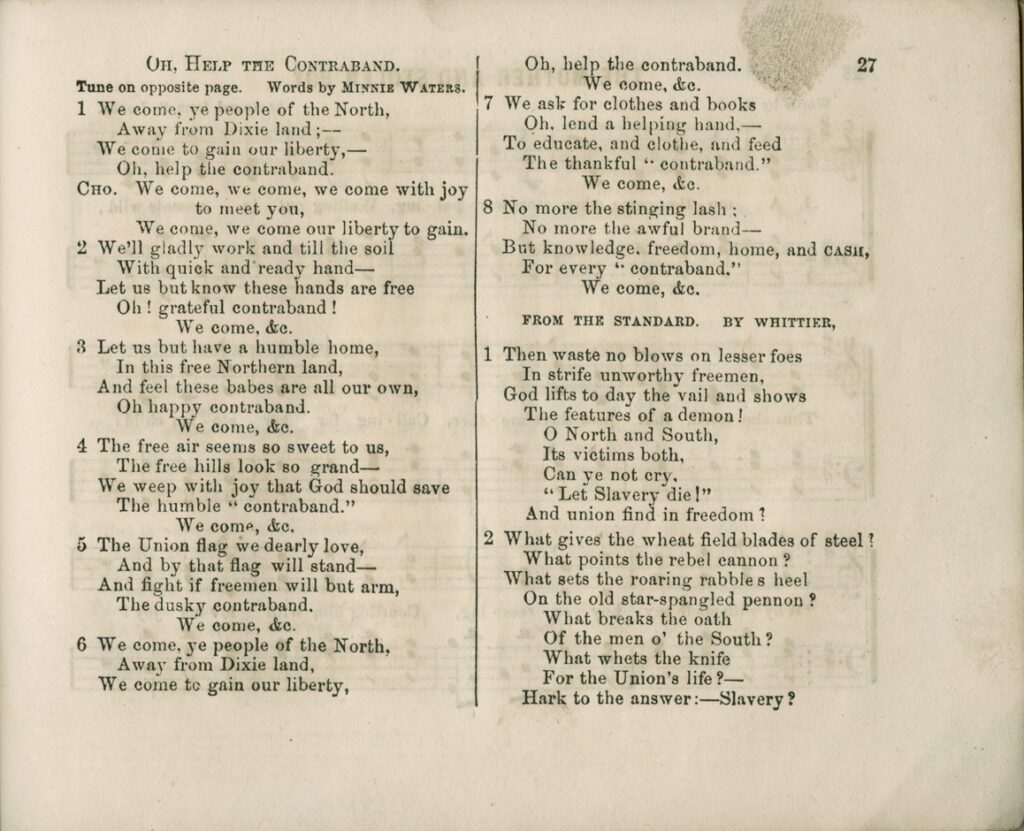

Anti-Slavery Songs

In 1861 the Confiscation Act declared that property used by the Confederate military, including slaves, could be confiscated by Union forces. This act was followed in March of 1862 with the Act Prohibiting the Return of Slaves. Together, these acts not only created a new legal category for certain escaped slaves, but also provided a common term, contraband, for referring to these slaves.

Questions to Consider

- Who is the intended audience for this song?

- According to the lyrics, what do the contraband desire from the “people in the North”?

- What assurances do “the contraband” make to the people in the North in exchange for their freedom?

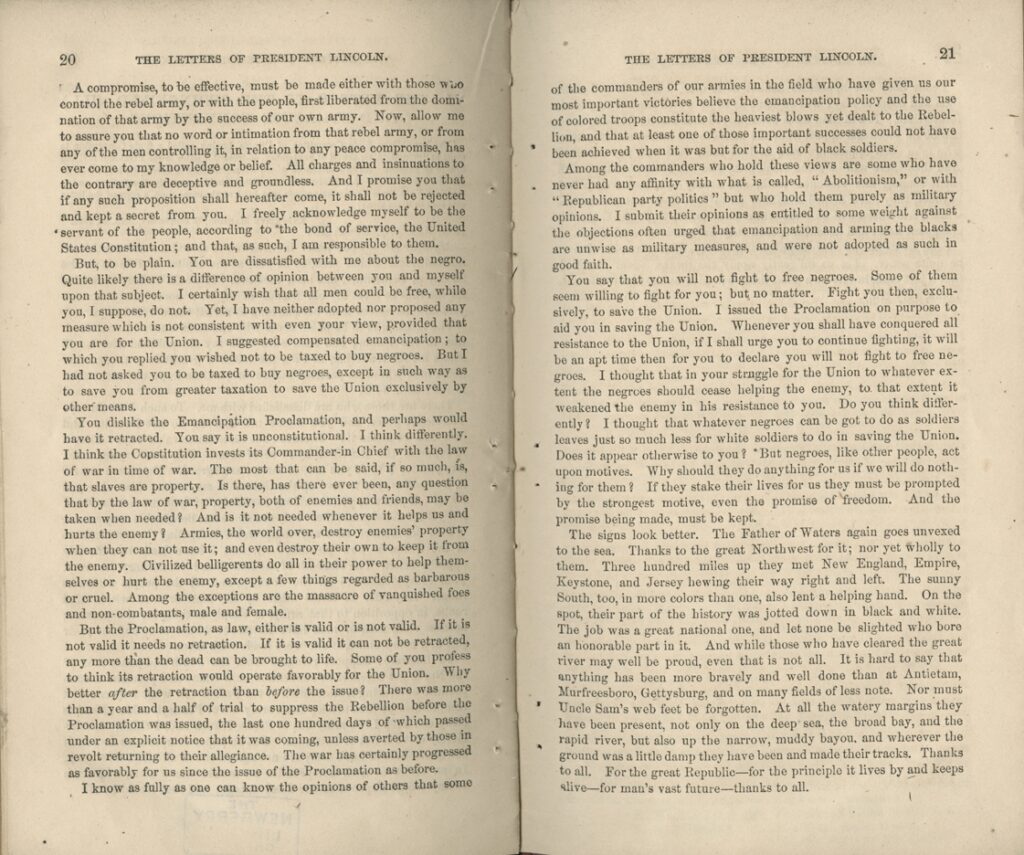

Lincoln Defends his Emancipation Proclamation

During the Civil War, Union supporters in President Abraham Lincoln’s hometown of Springfield, Illinois, asked him to speak at a rally on September 3, 1863. Lincoln could not attend, but wrote this letter to be read at the gathering by his longtime friend, James C. Conkling. This letter was also sent to the New York State Union Convention, which was held at the same time. In the letter, Lincoln defends his emancipation policy. At the beginning of that year, Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that “all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” The proclamation also established that freed slaves would be allowed to serve in the Union army.

Questions to Consider

- What arguments does Lincoln make for his authority to issue the Emancipation Proclamation?

- How will the Emancipation Proclamation contribute to the goal of saving the Union, according to Lincoln?

- How does Lincoln present the Emancipation Proclamation as serving a military purpose? Why do you think he felt compelled to make this argument? Does this rationale for the Emancipation Proclamation support or conflict with the document’s moral significance?

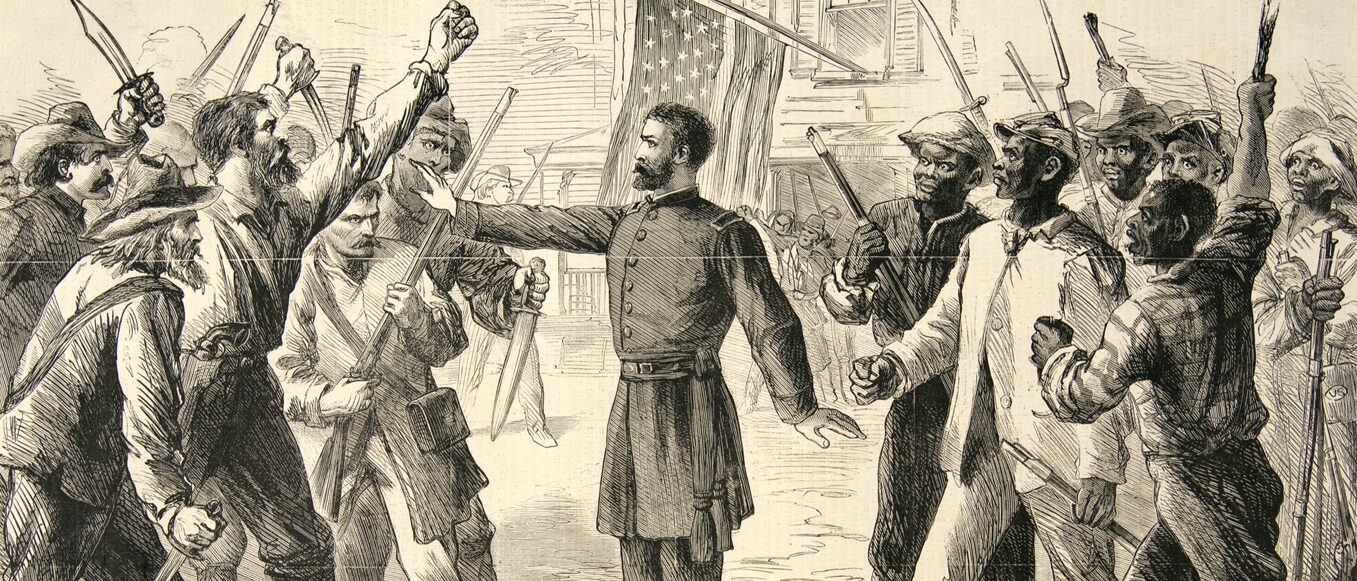

Former Slaves Join Sherman’s March to the Sea

Between November and December of 1864, Major General William Tecumseh Sherman conducted what came to be known as “Sherman’s March to the Sea.” As his army marched through Georgia, it destroyed crops, land, and equipment that could aid the Southern cause. Along the way, hundreds of former slaves joined the “rear guard” of the Union forces. The campaign ended when Sherman’s troops reached Savannah, Georgia, on December 21st.

Questions to Consider

- Describe the different ways that African Americans are portrayed in the image.

- What kinds of relationships does the image represent between freed slaves and Union soldiers?

- How might this image have been used to further the arguments in favor of emancipation?

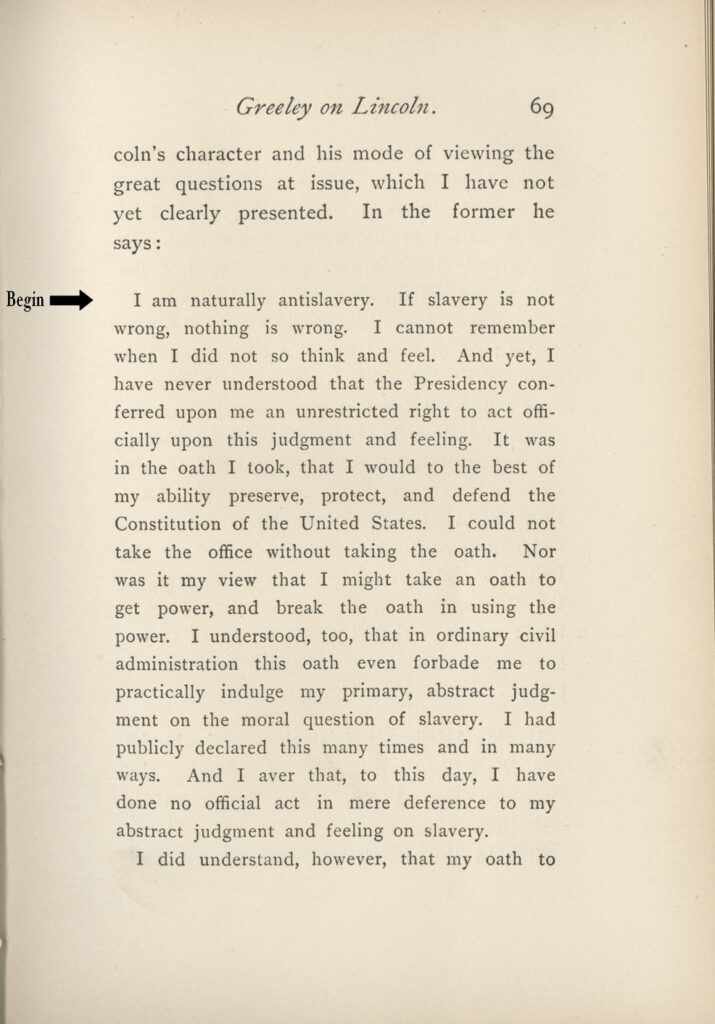

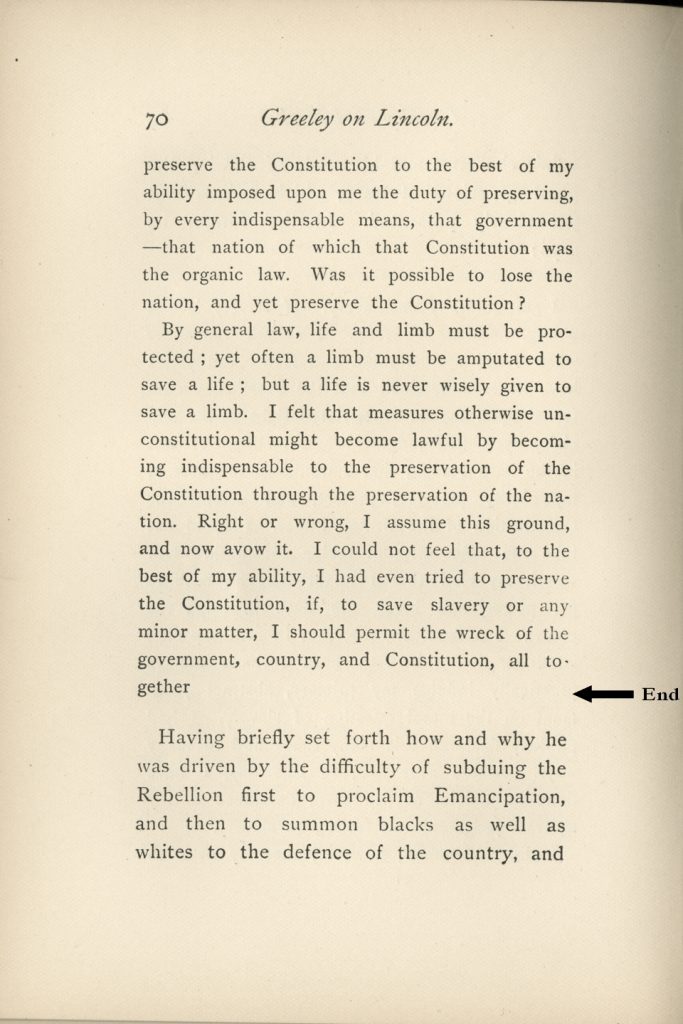

Lincoln’s Changing Position on Emancipation

Abraham Lincoln wrote this letter at the request of Albert Hodges, a Kentucky newspaper editor. In it, Lincoln restates thoughts that he had voiced in conversation with Hodges and two prominent Kentucky politicians. The letter illuminates Lincoln’s changing position on the question of emancipation.

Selection: Abraham Lincoln to Albert Hodges in Greeley on Lincoln, 69 (April 4, 1864)

Questions to Consider

- What differences does Lincoln present between his personal position on slavery and the position that he takes as the president of the United States? Why does he make this distinction? What does he see as his primary obligation as president?

- What does Lincoln mean by the metaphor of amputating a limb to save a life? Why do you think he chooses a metaphor of the body?

Challenges of the Freedman’s Bureau

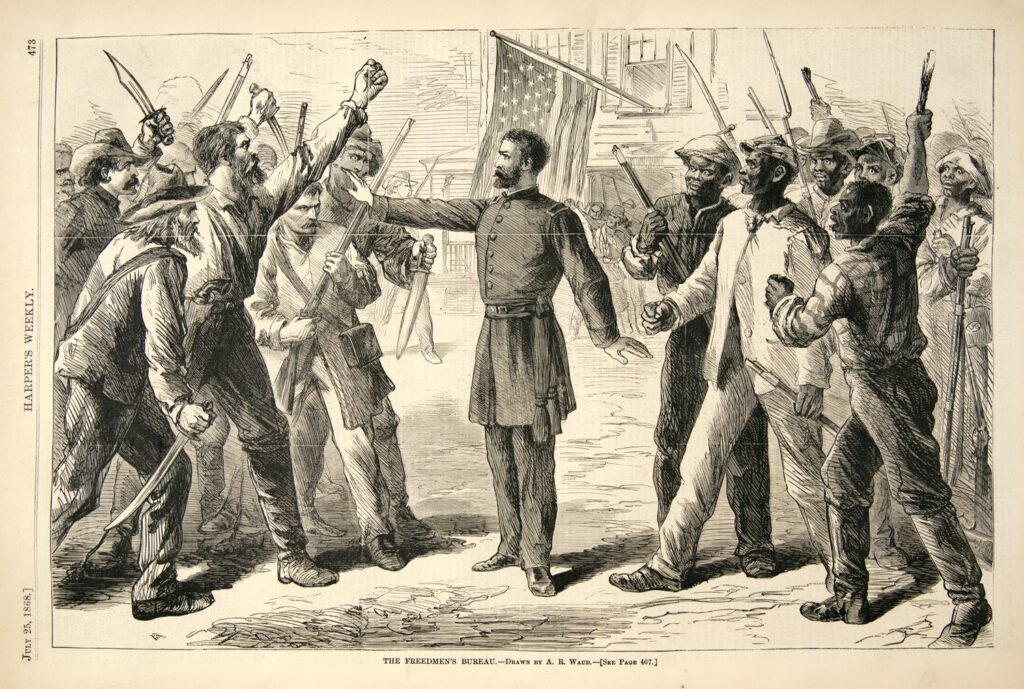

The Freedmen’s Bureau was a U.S. federal agency established at the end of the Civil War to aid freed slaves and refugees in the South. The agency assisted newly freed slaves in obtaining clothing, food, jobs, and housing. It also established schools for freed slaves. The Freedmen’s Bureau faced significant opposition from white Southerners, especially for establishing its own court system to bypass Southern civil courts, which were presumably biased against African Americans. In 1869 the Freedmen’s Bureau was disbanded.

Questions to Consider

- Describe and compare the appearances of the men on the left side and the right side of the illustration. What emotions do their faces and postures express?

- How does the man in the middle, the representative of the Freedmen’s Bureau, appear? What is he doing? What is the role of the Freedmen’s Bureau, according to this image?

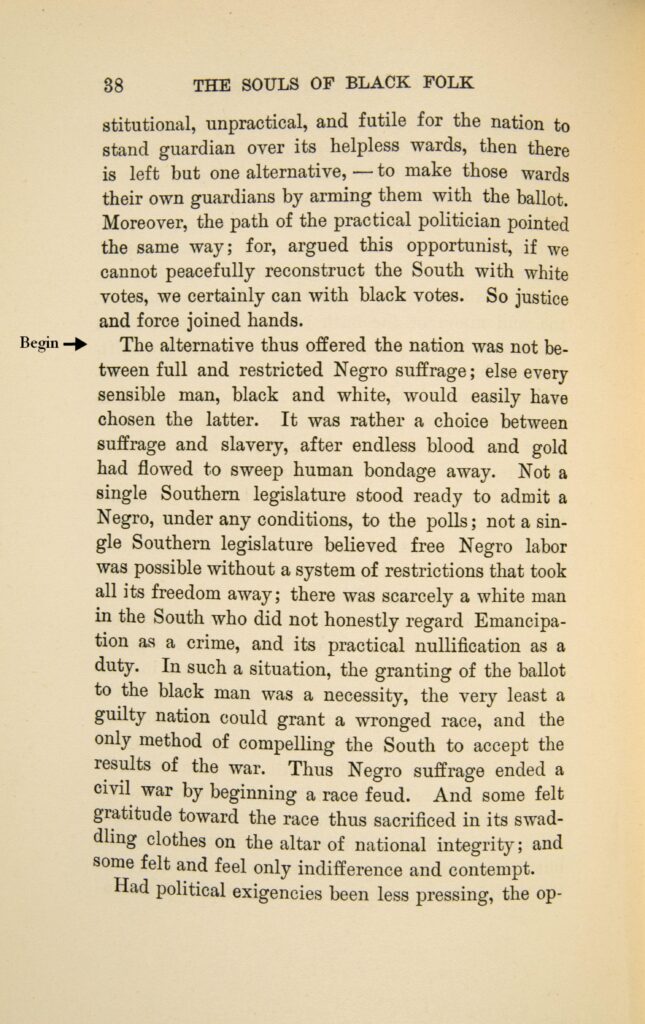

W.E.B. DuBois Challenges the Idea of the Freedman’s Bureau

W.E.B. Du Bois was a prominent black intellectual, writer, and activist who famously declared, “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line.” He criticized the position of another important black leader, Booker T. Washington, who had argued that accommodation of post-Reconstruction racial segregation would bring incremental progress to the race. Du Bois, in contrast, advocated immediate, full political and social equality for African Americans. “Of the Dawn of Freedom” provides a history of Reconstruction and, specifically, the Freedmen’s Bureau. Du Bois explains that many whites, particularly in the South, questioned the necessity as well as the constitutionality of the agency. Their arguments inadvertently bolstered the case for black enfranchisement: If African American men could vote, they would not need the protection of the Freedmen’s Bureau. They could defend their own interests.

Questions to Consider

- According to this passage, what were social conditions like in the South following the Civil War?

- Why did the nation face “a choice between suffrage and slavery”? What would be the effects of “the granting of the ballot to the black man”?

- What are the ramifications, according to Du Bois, of the dissolution of the Freedman’s Bureau and the enactment of black male suffrage? Why does he see the black race as “sacrificed in its swaddling clothes on the altar of national integrity”?

Calls for Abolition

These abolitionist materials, pieces from the Anti-Slavery Almanac and the song “Oh, Help the Contraband” make arguments for the abolition of slavery, framing their appeals in moral, social, economic, and political terms.

Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation

These two letters, written less than a year apart, capture Lincoln’s changing views on the question of emancipation following the Emancipation Proclamation.

Freedmen

The newly acquired freedom of several million formerly enslaved people prompted new questions and debates about their position in society and politics.

Further Reading

Thomas C. Holt. “Ch. 4: ‘A New Birth of Freedom’: The Destruction of Slavery and Reconstruction of Black Life.” In Children of Fire: A History of African Americans, 2010. 133-83.