Introduction

For nearly 150 years, the battle for “true” Christianity tore early modern Europe apart. The spiritual divisions created by the Protestant Reformation led to a series of international and domestic conflicts that caused incalculable destruction and tremendous loss of life. These conflicts ranged from international wars – including the Schmalkaldic War (1546-47), the Eighty Years’ War (1568-1648), the French Wars of Religion (1562-1598), and the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) – whose causes were rooted in religious differences. In between these campaigns, religious violence continued in a seemingly endless series of riots, persecutions, and massacres committed by the general populace.

The splintering of the medieval church ushered in a volatile new era of increased anxiety, tension, and religious fervor during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Many adherents of the now-competing Christian churches were willing to defend their faith to the death against all threats. At the same time, secular authorities moved aggressively to control an increasing number of social and political upheavals. The combination of intense religious conviction and stronger political intervention created a wave of violence that touched the lives of people throughout Europe in profound ways.

The primary sources in this collection provide an overview of how people from all walks of life in early modern Europe experienced these devastating conflicts, sometimes directly, sometimes from a distance. Beyond bringing these stories of suffering and survival to light, the sources below will highlight the larger cultural forces driving the surge of religious violence, from political centralization to the development of print culture. In so doing, the documents and images below will reveal how the early modern religious wars played a significant role in shaping European culture’s transition from the medieval into the modern era.

Essential Questions:

- How are religious ideas or beliefs expressed throughout these documents?

- How do these documents reflect the growing mass media culture in the early modern period?

- How does early modern religious violence help us understand violence that claims to be religious?

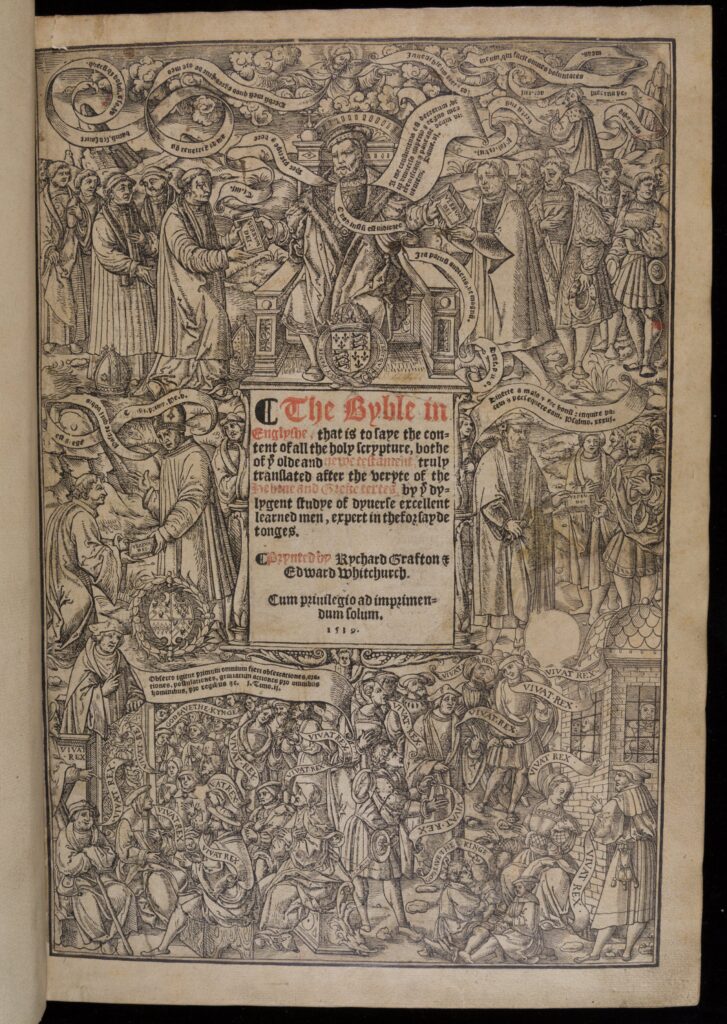

From Reformation to Religious War

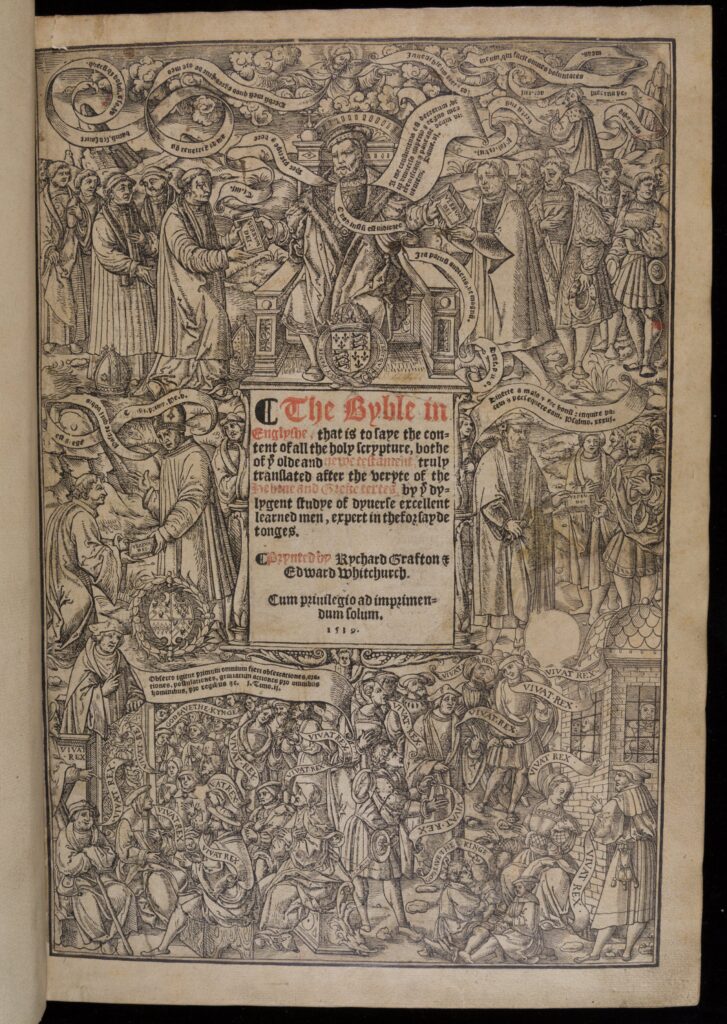

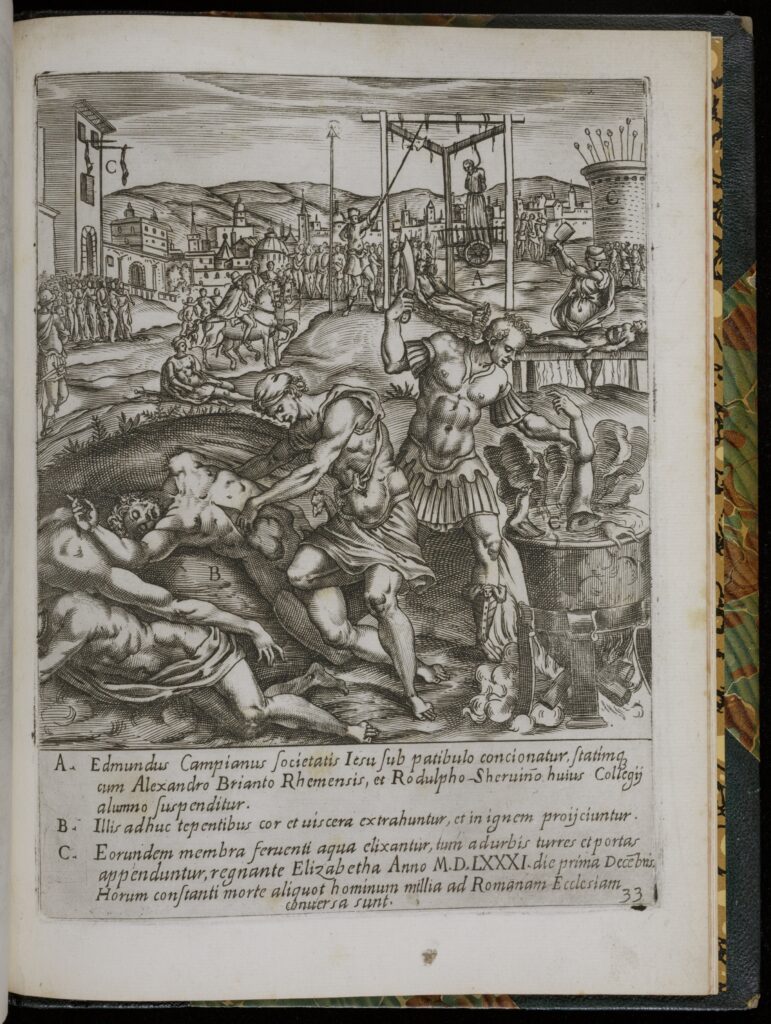

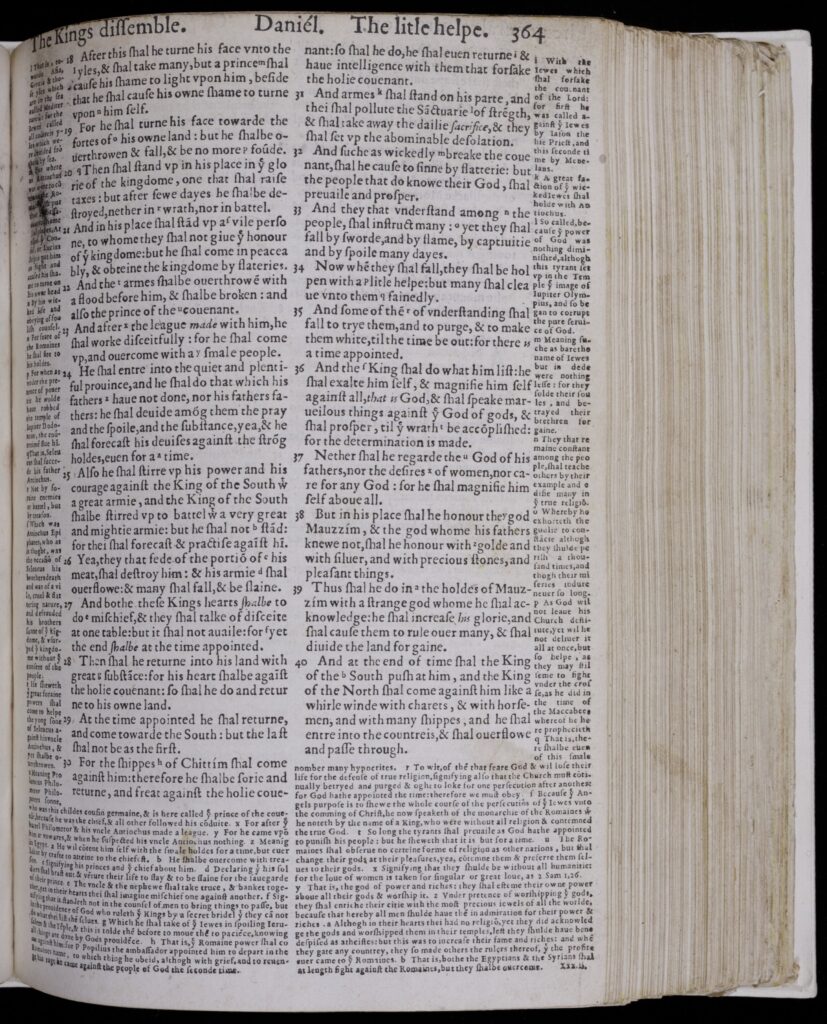

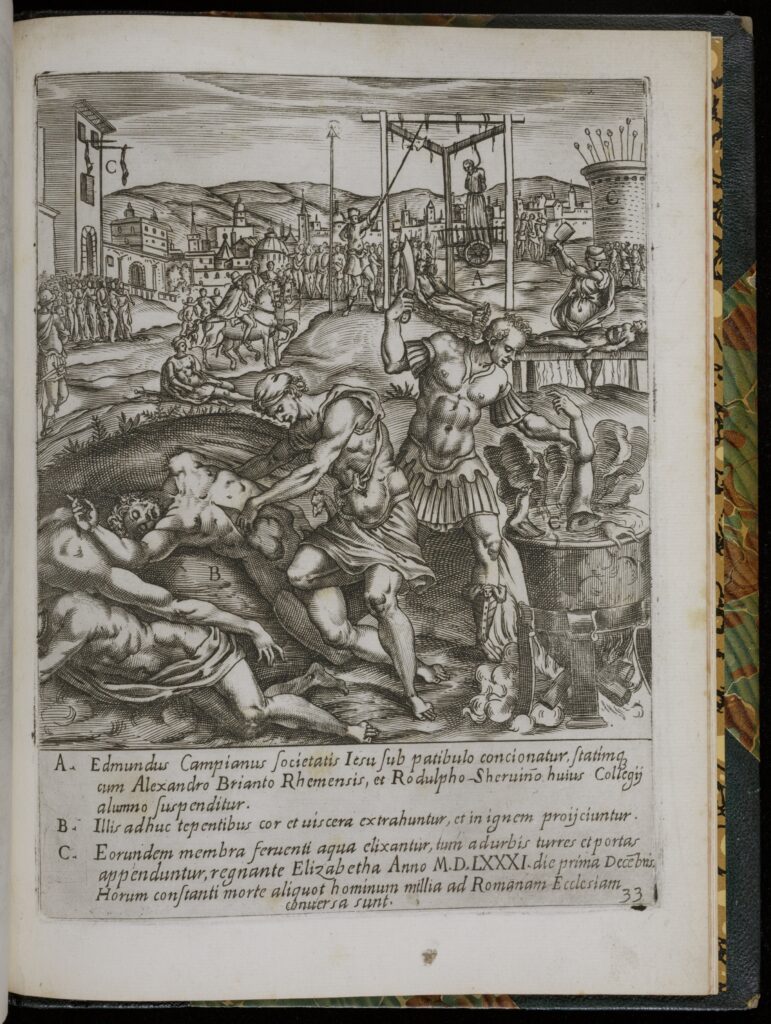

There were many factors fueling early modern religious wars, but perhaps the most potent was the close relationship between religion and politics. In the early days of the Reformation, Martin Luther openly invited the German princes to reform the Church. In the years that followed, secular authorities of all kinds (kings, princes, town councils, etc.) took a direct role in legislating religious matters. Some went so far as to equate political loyalty with the practice of “true” Christianity. Few places better exemplify this trend – and the tensions it created – than England, which underwent a complicated process of religious reform throughout the early modern period. Immediately after his famous break with the Roman Church, Henry VIII did everything in his power to remind his subjects that the king was the head of both church and state. That included this woodcut in the first state-sanctioned English translation of the Bible, which shows Henry personally delivering the Scripture to his people. Try as they might, however, authorities like Henry could never gain complete control over their subjects’ religious convictions. Evidence of their failure can be seen on the pages of the Geneva Bible, the most popular version of the Bible in early modern England. Many of the copious marginal notes in these Bibles, such as this explanation for Daniel 11: 36, encouraged readers to stay true to their faith even if it meant disobeying their rulers. Such a tense atmosphere led naturally to violence; in the early modern period, practicing a faith other than the “official” one was grounds for treason, and thus execution. A famous case for this was Edmund Campion, a English Jesuit priest working to win converts to Catholicism during the reign of Elizabeth I. Campion had attempted to assure the queen and her advisors that he could still be a loyal citizen despite being Catholic, but he ultimately chose to accept the gruesome fate depicted in this engraving rather than betray his faith, a choice shared by thousands more in the early modern period.

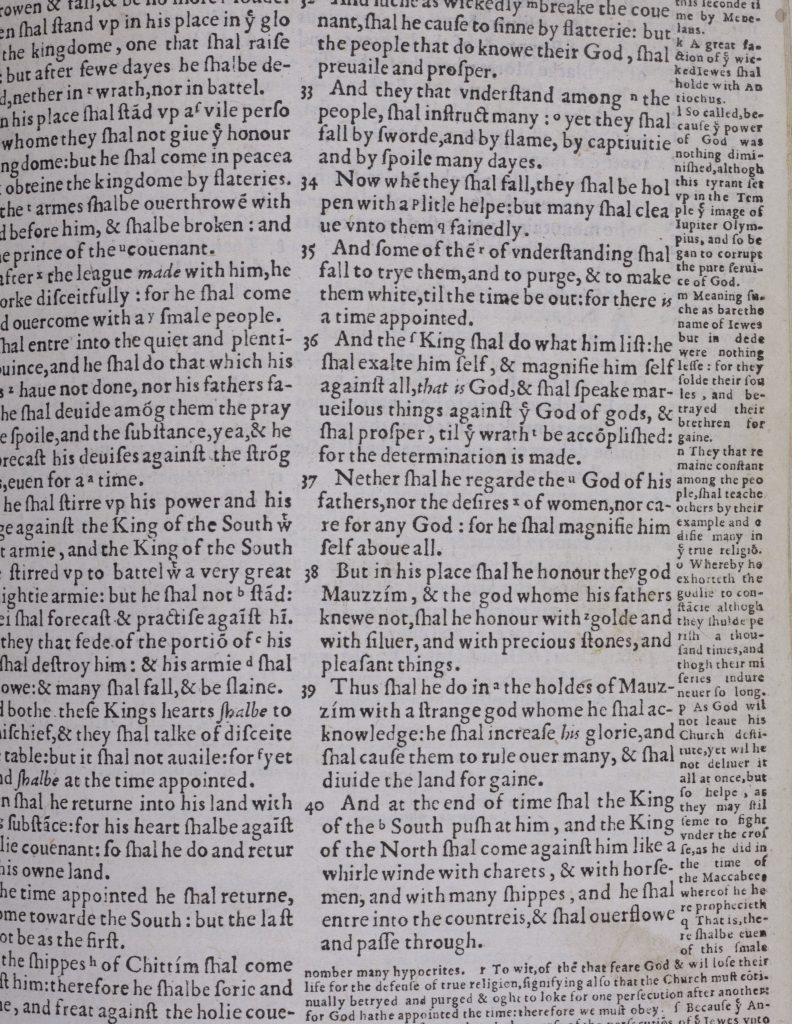

Selection: The Bible and Holy Scriptvres Contyned in the Olde and Newe Testament [Geneva Bible], 364 and details (1560).

Questions to Consider:

- What kind of relationship between the king and the church does the title page of the Great Bible describe? According to the image, how do the common people feel about this relationship?

- Why did the editors of the Geneva Bible include these printed notes in the margins? How might they help explain why the Geneva Bible was the most popular English Bible of the period?

- Who was the primary intended audience for images like the engraving of Campion’s martyrdom?

Collateral Damage

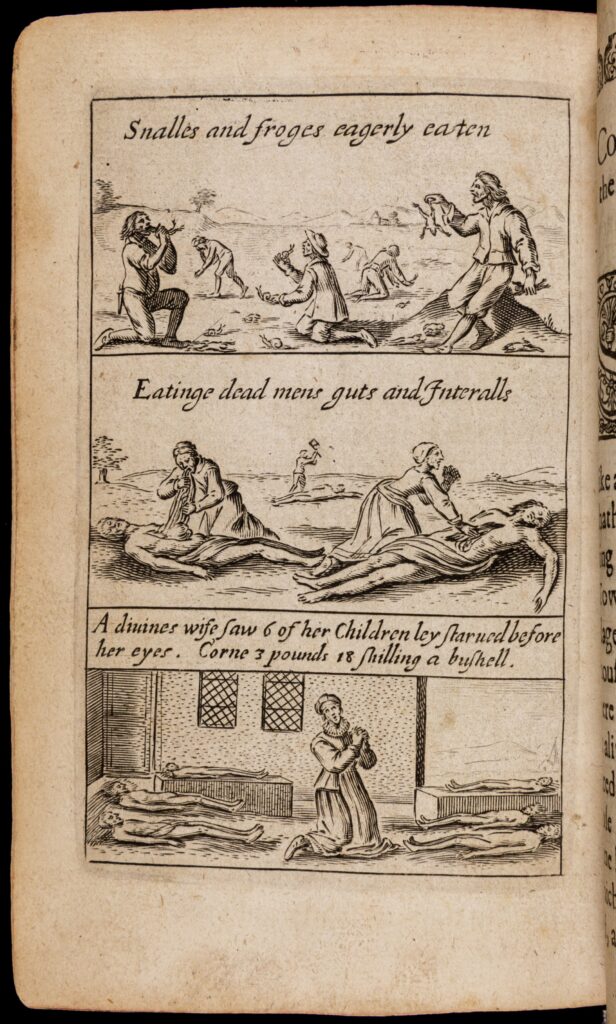

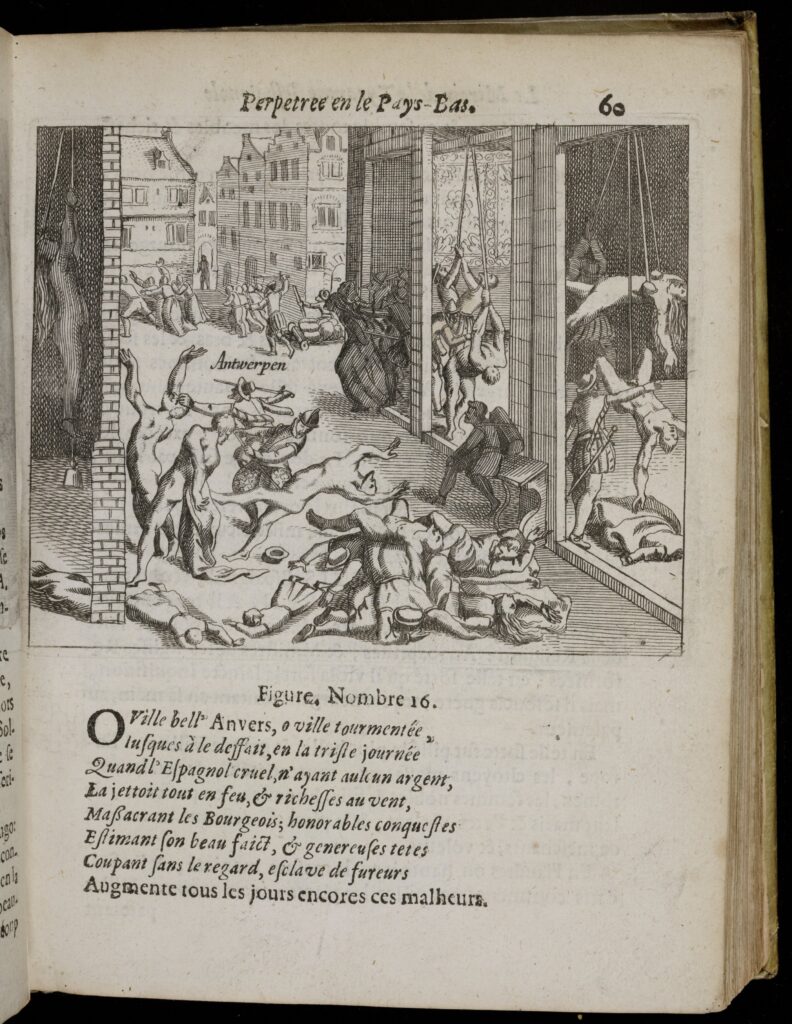

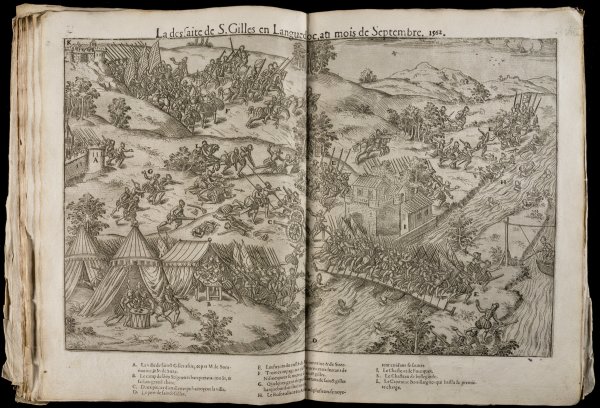

Whether fought between foreign powers or between neighbors, wars of religion approached the modern concept of a total war, in which entire populations were targeted for attack. As a result, they produced an incredible amount of collateral damage. Typically, the force of the violence fell most heavily on ordinary people. This detail from the Siege of La Rochelle, one of the most important sieges during the Thirty Years’ War, shows the pillaging and burning of a village in the countryside, a fairly routine occurrence when the mercenary soldiers who did much of the fighting were not paid. Many others who were not killed outright by soldiers often died from starvation or disease as their lands and food supplies were raided, a fate illustrated in these engravings from The Lamentations of Germany, a contemporary English account of the war. City dwellers fared little better; victorious besiegers often sacked and plundered cities after taking them, killing thousands of citizens and displacing thousands more. The image below, taken from a Dutch book condemning the cruelty of Catholic Spain, shows the devastating sack of the city of Antwerp by Spanish troops in 1576. All the same, wars of religion were difficult for soldiers, as well; this satirical, yet truthful passage from the fantastical Adventures of Simplicius Simplicissimus makes clear that ordinary soldiers too died from starvation, disease, and poverty while the noble officers giving them orders often escaped unscathed.

Selection: Hans Jakob Christoph von Grimmelshausen, The Adventures of Simplicius Simplicissimus, 32-33 (1965).

Questions to Consider:

- The Siege of La Rochelle was designed to celebrate the siege as a triumph for the Catholic king of France. With that goal in mind, why would Callot have decided to include details showing the pillaging and burning of villages?

- Why did Vincent and Cloppenburg include images like these in their books? How do the images help make the authors’ arguments?

- How do the differences between the people in the lower branches of the military, and those in the higher branches in the vision from Simplicius help explain the brutally violent nature of early modern religious wars?

Wartime Media

Print culture was a critical part of early modern religious wars. Throughout the period, authors, artists, and printers created a range of printed works to accomplish a variety of tasks necessary to survive the wars for Christianity’s future. Some publications were intended to inspire one’s supporters. A particularly unique example of this is the anonymous Song for the Landsknechte, which was written for Protestant mercenaries fighting the mostly Catholic imperial armies during the Schmalkaldic War. The song rallies the Protestant soldiers using the political and religious stakes of the conflict, encouraging them to fight “against the pope’s idolatry and Spain’s murderousness.” The immense stakes of religious wars naturally drew the attention of the general public, which followed their progress with a mixture of fear, curiosity, and excitement. To meet this growing need for news, an array of publications were created to bring up-to-date reports of religious wars in close to real time.

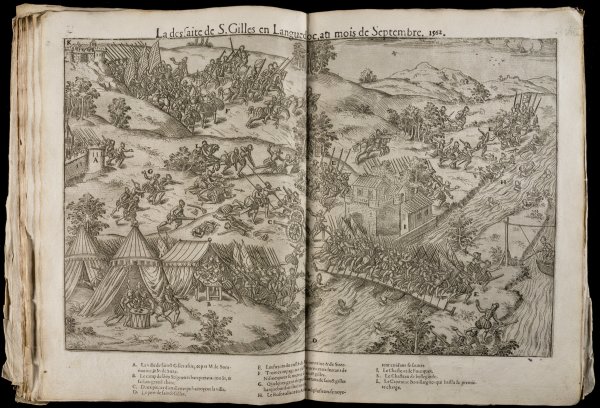

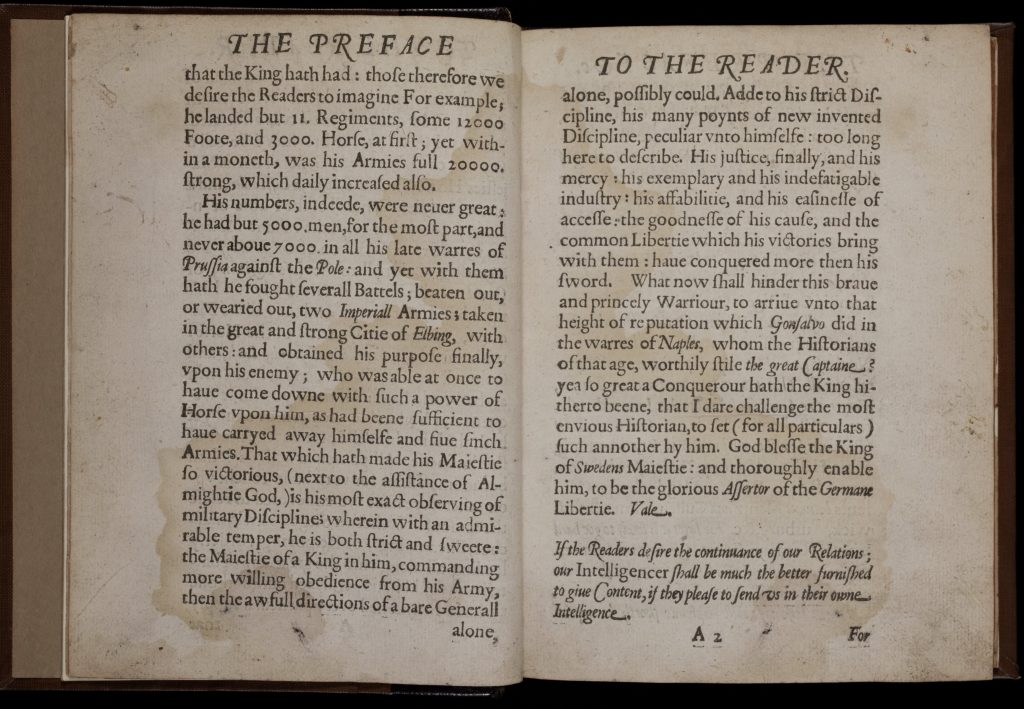

The striking engravings of the battles, massacres, and political events in the French Wars of Religion depicted in the First Volume Containing Forty Tableaus represented one of the earliest attempts to help the general public throughout France visualize (from a Protestant perspective) the wars more-or-less as they were happening. Readers far removed from the battlefields were also eager for reports on religious wars, since their results could have dramatic consequences for Christianity throughout Europe. Protestant England, for instance, eagerly followed the exploits of the Lutheran king of Sweden, Gustavus Adolphus, whose forces turned the tide of the Thirty Years’ War in the early 1630s. The serial publication The Swedish Intelligencer was one place to find this information, offering English readers a detailed account of Gustavus’s activities that was drawn from first-hand accounts and newspapers from Germany.

Selection: William Watts,The Swedish Intelligencer, title page and Av1-Ar1 (1632).

Questions to Consider:

- What does the format and content of the Landsknecht song tell us about the role printers played in early modern religious wars?

- Based on what you see on the print, how were sixteenth-century readers supposed to use the engravings from the First Volume to learn about the French Wars of Religion?

- What does the note at the end of the preface to The Swedish Intelligencer tell us about how news of important contemporary events was created in early modern England?

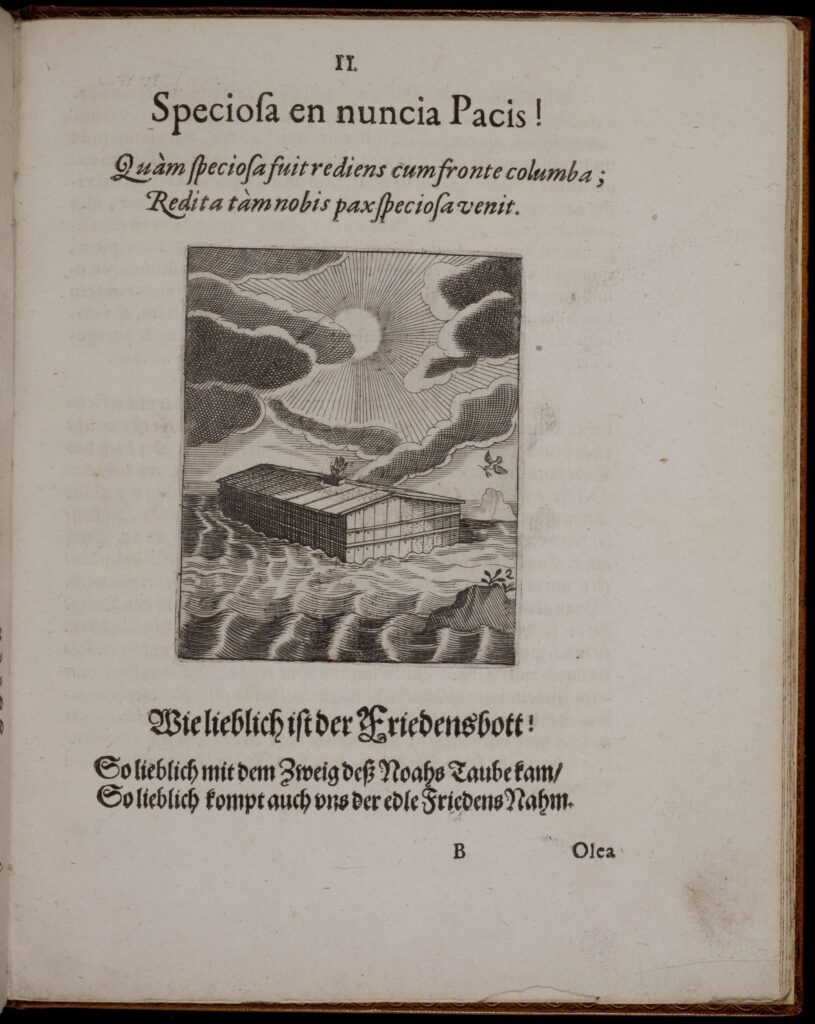

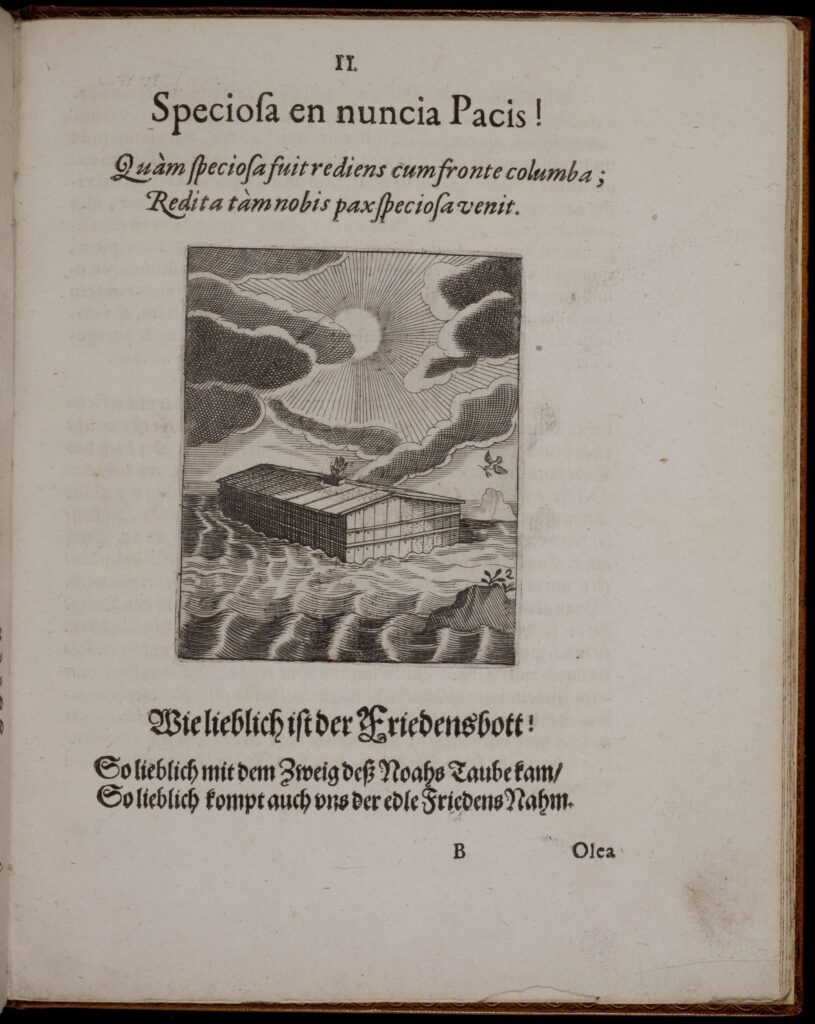

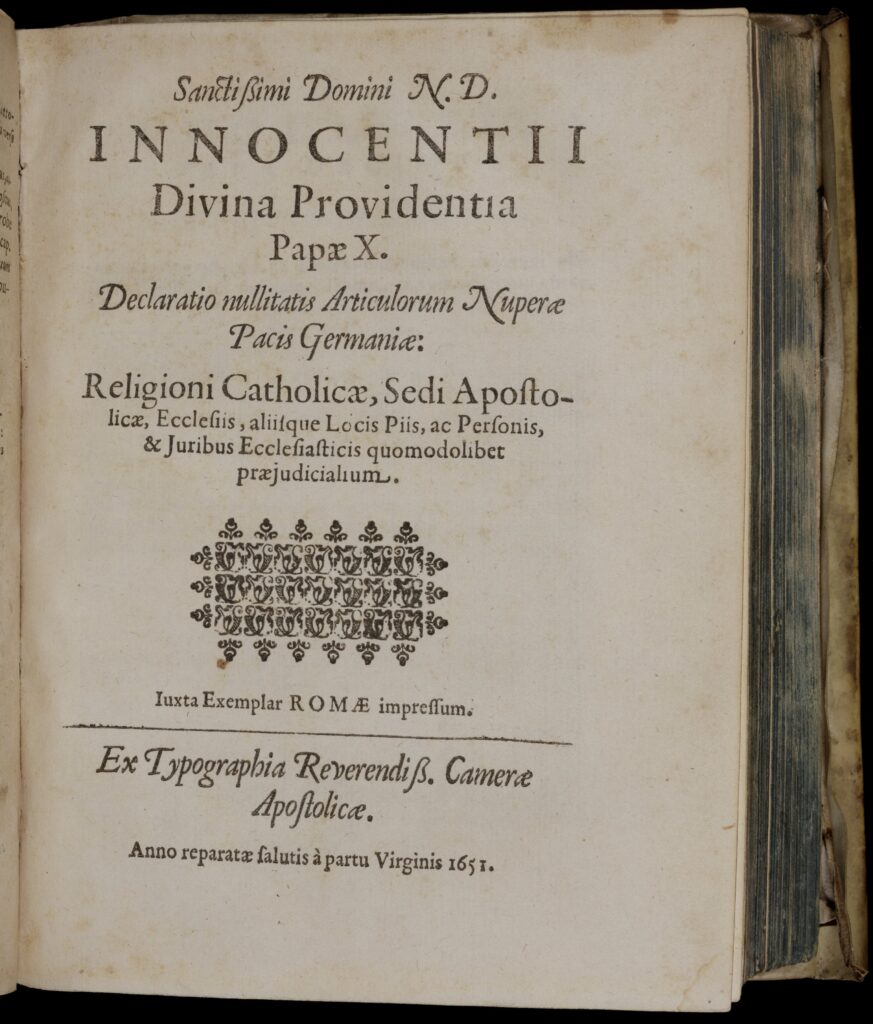

A New Kind of Peace

The conclusion of the Thirty Years’ War in 1648 marked the end of the early modern religious wars. For those who experienced it, the peace was nothing less than a miracle. The Emblematic Meditations on the Restored Peace in Germany portrays the immense sense of relief at the war’s conclusion. Its emblems were designed to project the sense that the people of Germany had been freed from the seemingly endless war by an act of divine intervention. Nearly all of them included visual elements to emphasize that point, such as streaming light, dissipating clouds, and clear religious imagery. The historical significance of the Peace of Westphalia was recognized at the time. Although religion remained a potent cultural force, the various participants in the war agreed to keep religious differences out of the affairs of state going forward. Their decision was met with indignation by Pope Innocent X, who issued the bull Zelo domus dei to protest the treaty and encourage Catholic nations to ignore it, declaring it “null, void, invalid, evil, unjust, damnable, reprobate, and hollow.” The pope’s order caused some uproar as final terms were negotiated, but it ultimately failed to derail the peace process. The years of exhausting collateral damage fighting over “true” Christianity had convinced the peoples of Europe that the close bond between religion and politics that ignited the early modern religious wars was better left in the past.

Selection: Johannes Hoornbeeck, Examen Bullae Papalis, qua P. Innocentius X. abrogare nititur Pacem Germaniae [An Examination of the Papal Bull, with which Pope Innocent X Attempted to Abrogate the Peace of Westphalia], title page and book 3, page 5 (1653).

Questions to Consider:

- Many people were skeptical that the Peace of Westphalia would actually end the Thirty Years’ War. How does the image here attempt to guide the reader to support the Peace?

- How does Innocent X’s opposition to the Peace of Westphalia help explain the separation of church and state in the U.S. Constitution?

Further Reading

Cunningham, Andrew and Ole Peter Grell. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse: Religion, War, Famine and Death in Reformation Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Kaplan, Benjamin. Divided by Faith: Religious Conflict and the Practice of Toleration in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

MacCulloch, Diarmaid. The Reformation: A History. New York: Viking, 2004.

Pettegree, Andrew. The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know about Itself. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014.