Introduction

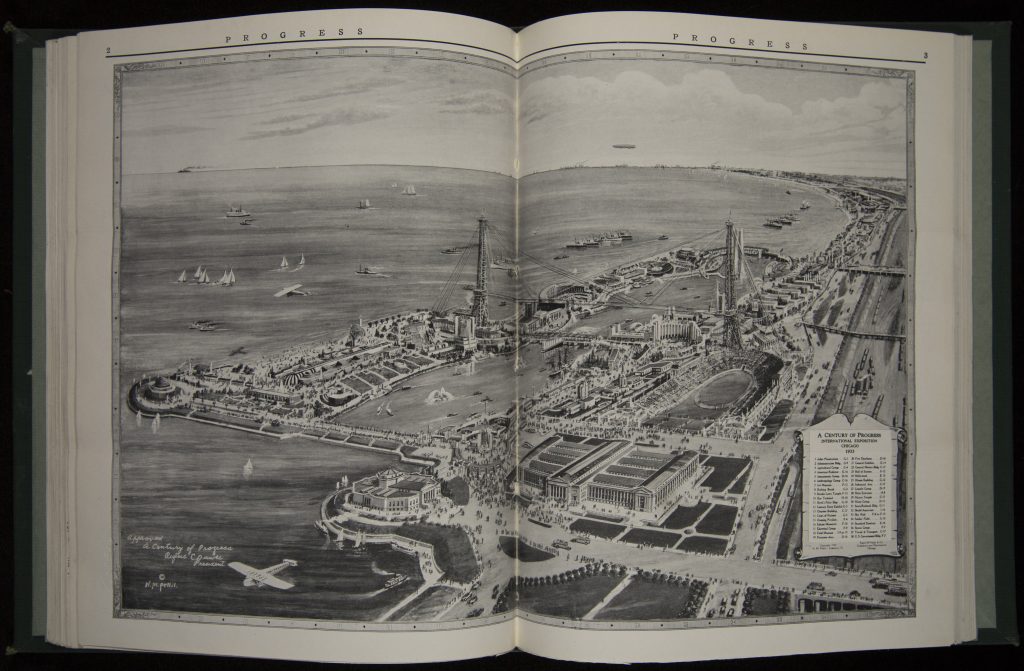

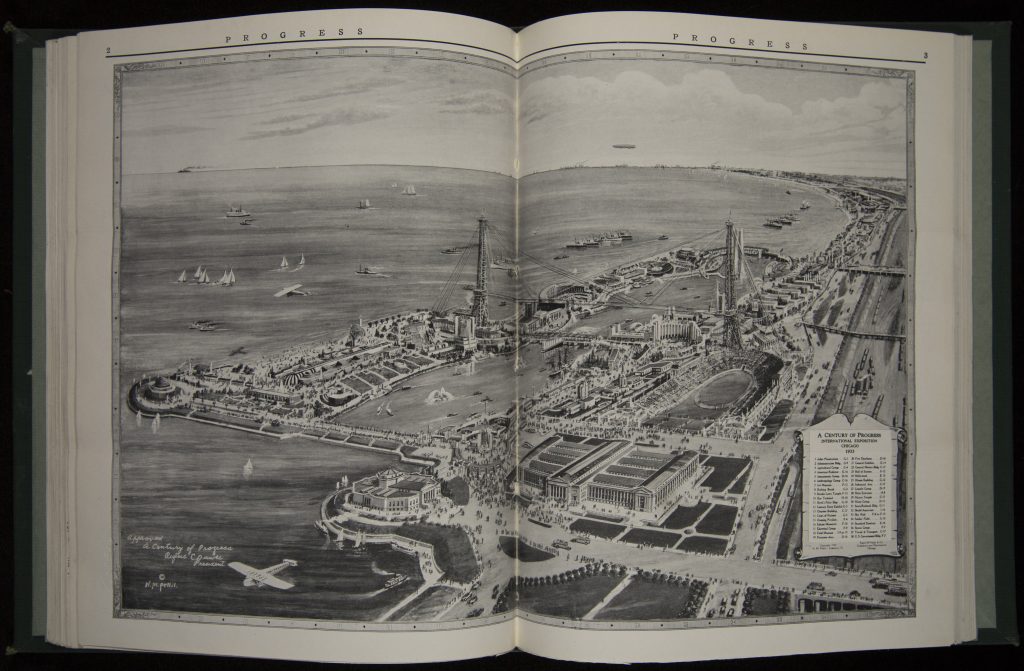

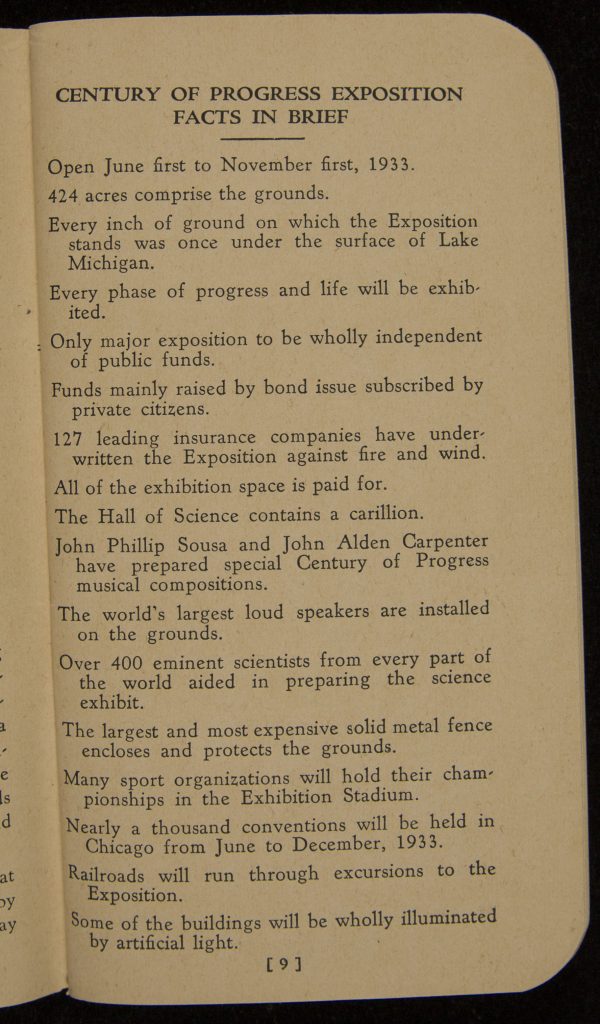

Just forty years after the 1893 Columbian Exposition brought visitors from around the world to Chicago for a world’s fair, Chicago hosted its second world’s fair, A Century of Progress International Exposition. The fair was situated on 424 acres near the museum campus, and almost the entire fairground was filled in lake shore. According to A Century of Progress promotional materials, the exposition was within a day’s ride of 75% of the United States population. Over the course of the fair’s 1933-34 run, the world’s fair welcomed over thirty nine million visitors from Chicagoland and beyond, breaking world’s fair attendance records.

1933 may seem like an odd choice of year for a fair called a Century of Progress, but the name comes from the fair coinciding with the celebration of the centennial of the founding of Chicago. In the forty years since the Columbian Exposition, a lot had changed in Chicago, and in the rest of the world. In the intervening years, World War I and the Great Depression shaped society in new ways, and the world’s fair reflected some of the new attitudes and changes. Progress was the unifying theme for the world’s fair, and A Century of Progress offered a new idea of progress. Rather than focus on, and put faith in people to create a better world, the fair’s organizers looked to technological innovation as progress.

Planning for the Century of Progress began during the heady days of the Roaring Twenties, before the crash of the stock market in 1929 ushered in the Great Depression. The timing of the fair during the Great Depression influenced the development and reception of the fair. Given the tough financial times, some people thought the fair should not proceed for financial reasons, and that participation and visitation would be limited. However, A Century of Progress was remarkable for many reasons, not the least of which was that it turned a profit, even in the midst of the Great Depression. The fair was originally scheduled to run only in 1933, but due to the fair’s popularity, and the desire to turn a profit on the fair, it remained open for a 1934 season.

Unlike previous world’s fairs, the 1933-34 Chicago World’s Fair was funded by private money rather than extensive municipal and government funding. The economic crunch caused a number of countries to opt out of participating in the fair, or to focus on smaller exhibits rather than full exhibit pavilions. The limited funds also led to greater cooperation between exhibitors as in some cases, industries and other interests groups opted to share thematic buildings rather than hosting their own. Another new and unique feature of Chicago’s second world’s fair was the emphasis on science, industry, and the level of corporate participation. Companies like Havoline, Sears, and General Motors sponsored large corporate pavilions and fair landmarks, to use the fair as part of new marketing efforts.

As is the nature of world’s fairs, A Century of Progress was temporary. At the close of the 1934 season, fair buildings were torn down, and fair memorabilia scattered across the country. A Century of Progress served as a beacon of optimism and hopefulness during the Great Depression, and for many fair visitors, it provided memories that would last a lifetime.

Essential Questions

- What was unique about the 1933-34 Chicago World’s Fair?

- How did the creators of the Century of Progress illustrate and enact the fair’s theme of progress?

Building the Future

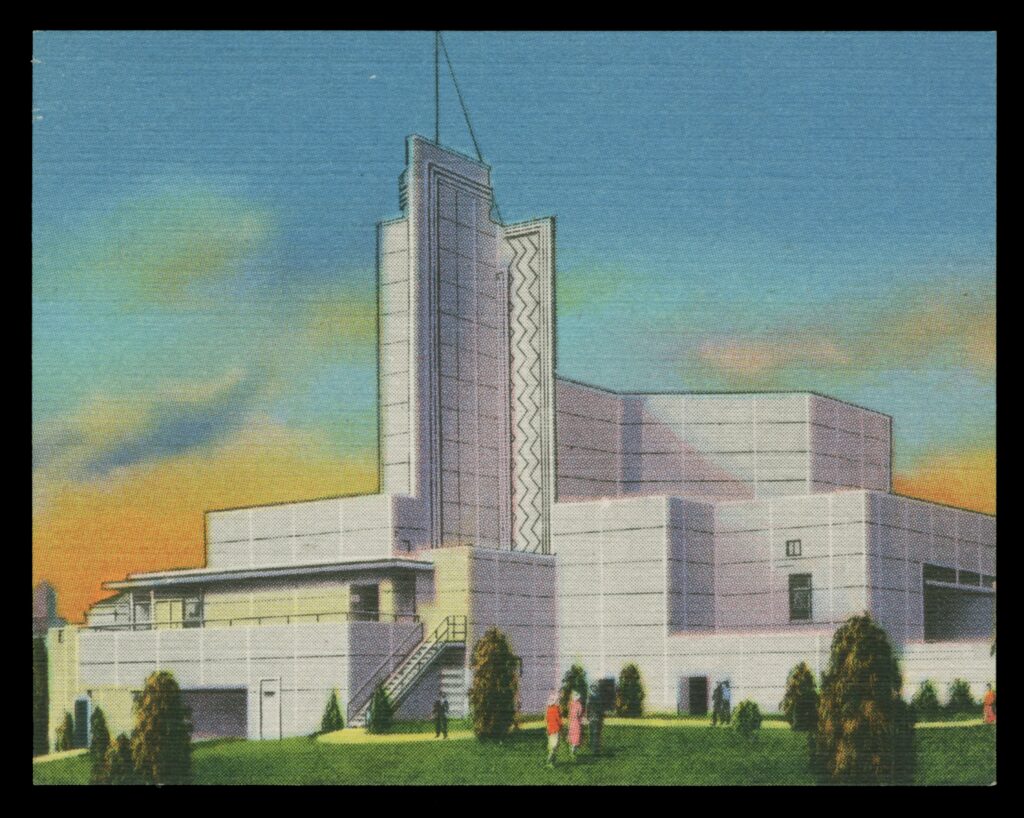

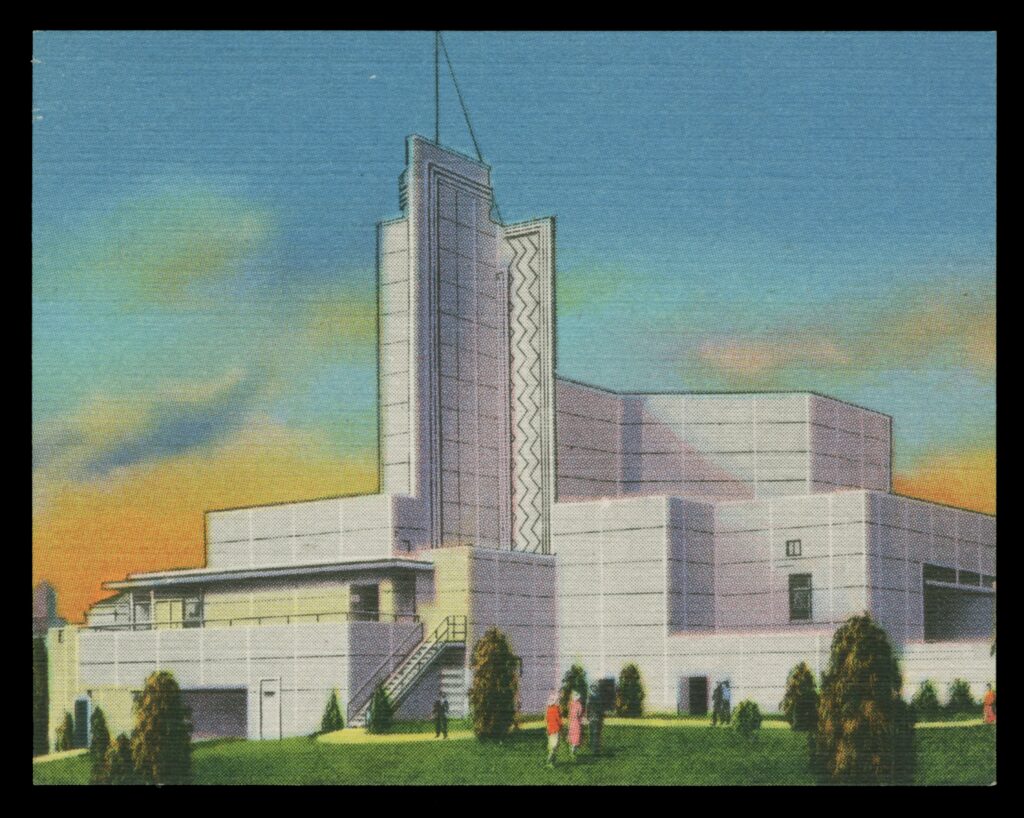

The architectural plan of the 1933-34 Chicago World’s Fair drew heavily on modern design. One of the defining characteristics of modernism in architecture was its anti-historicism. Rather than drawing inspiration from the past, modernist architecture endeavored to create something new. The clean lines and the comparatively unadorned exteriors of modernist fair buildings were very functional and dovetailed nicely with the scientific and industrial emphasis of the fair.

Unlike the White City of the 1893 Columbian Exposition, the Century of Progress embraced bold color choices for the buildings. To showcase the buildings at night, a large number of buildings featured specially designed dramatic exterior lighting. Many of the buildings also featured Art Deco elements. Art Deco designs favor bold geometric patterns, symmetry, stylized natural forms, and strong colors. The Art Deco style was a popular style during the 1920s and 1930s.

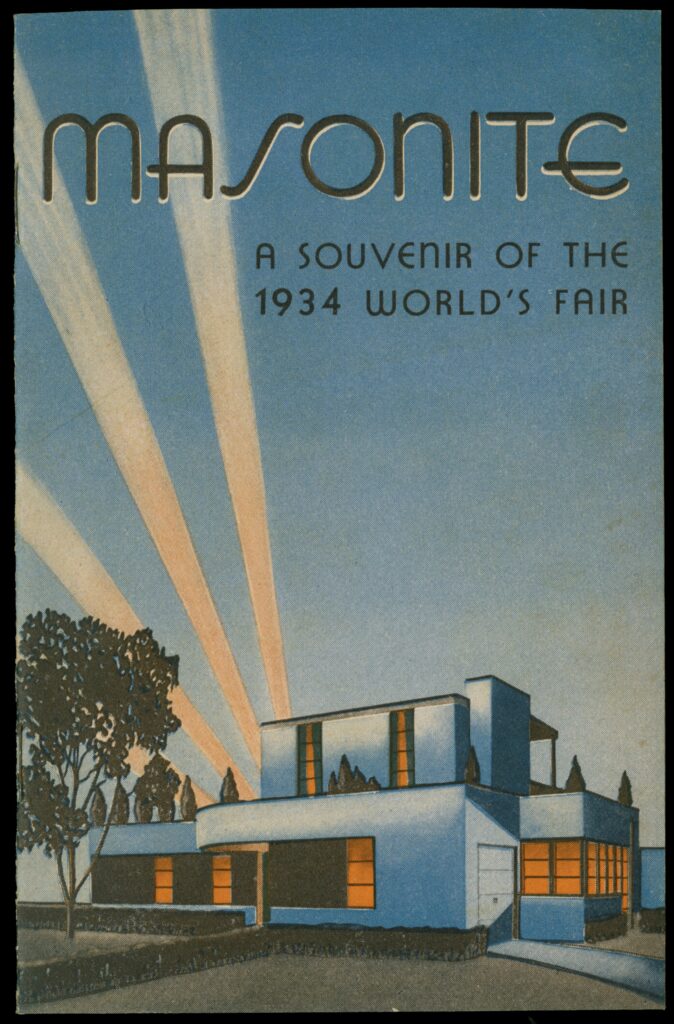

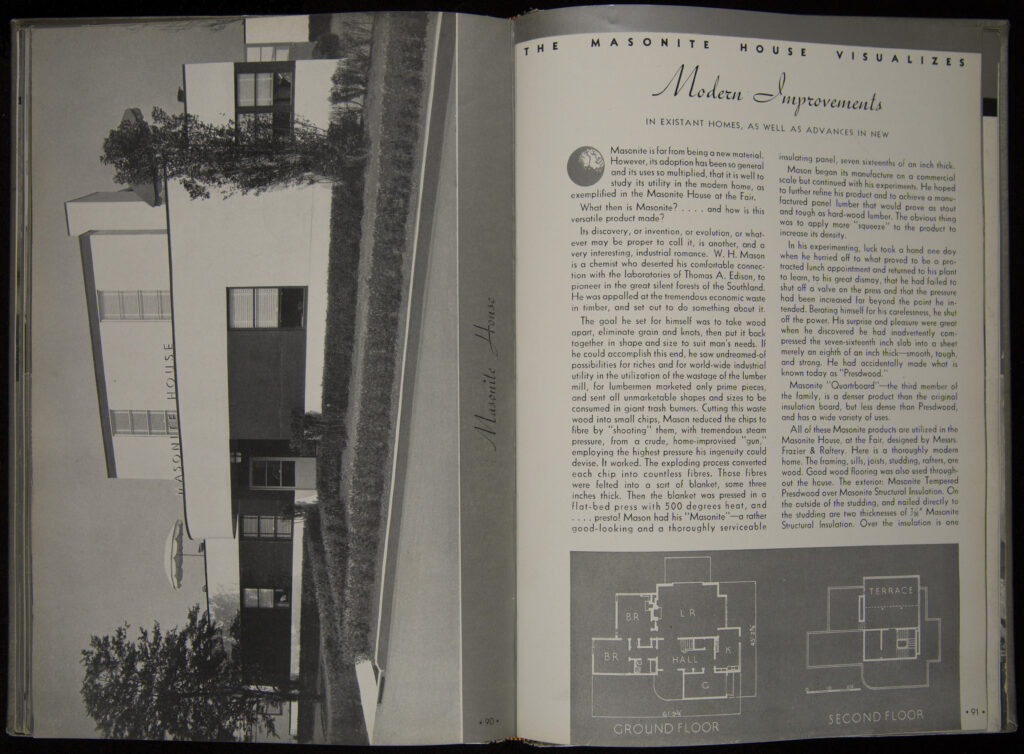

The expression of new ideas in architecture was not limited to large fair buildings, but was on full display at the fair’s popular Homes of Tomorrow. The exhibition that featured prototype houses showcasing new building techniques, building materials, and design ideas for a curious public. The homes featured a range of the most modern conveniences from central air conditioning to mechanical dishwashers. The exhibit really connected the fair ideas of science and industry to the modern home.

Selection: The Masonite House

Questions to Consider

- How does the architecture of the buildings illustrated in these documents relate to the fair’s themes of science and progress?

- Select an image of a building from the 1893: Chicago and the World’s Columbian Exposition digital collection. Compare the image from the 1893 World’s Fair to the buildings from 1933. What differences do you notice?

- What new design or construction solution does the Masonite House present? According to the text, what were the benefits of Masonite, and how was Masonite used in the construction of the house?

Art and the Fair

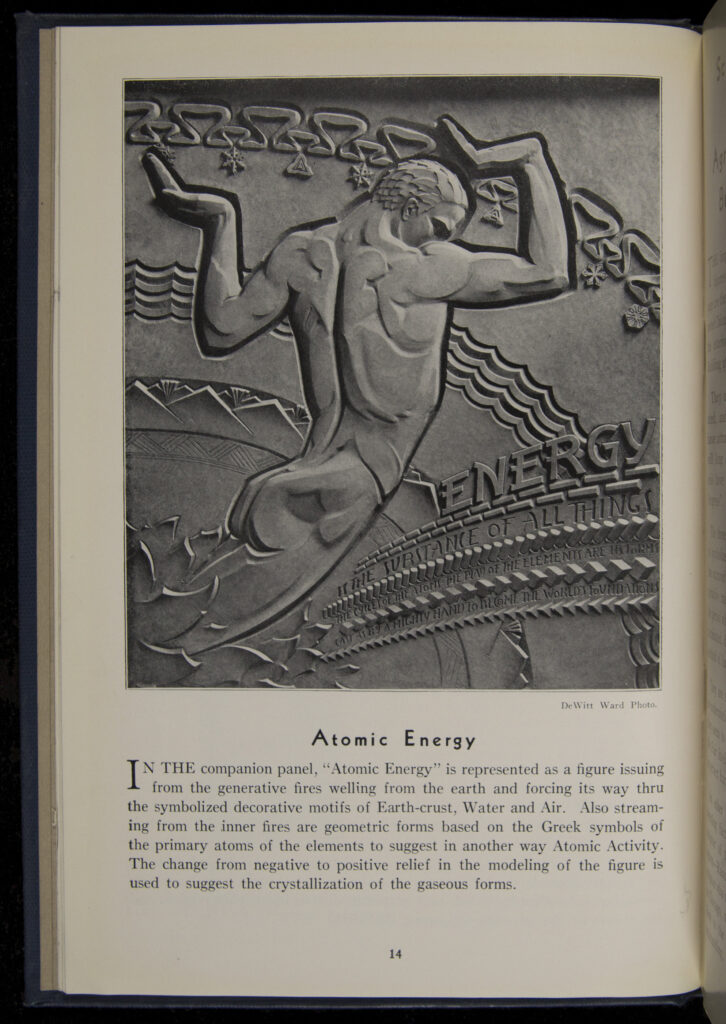

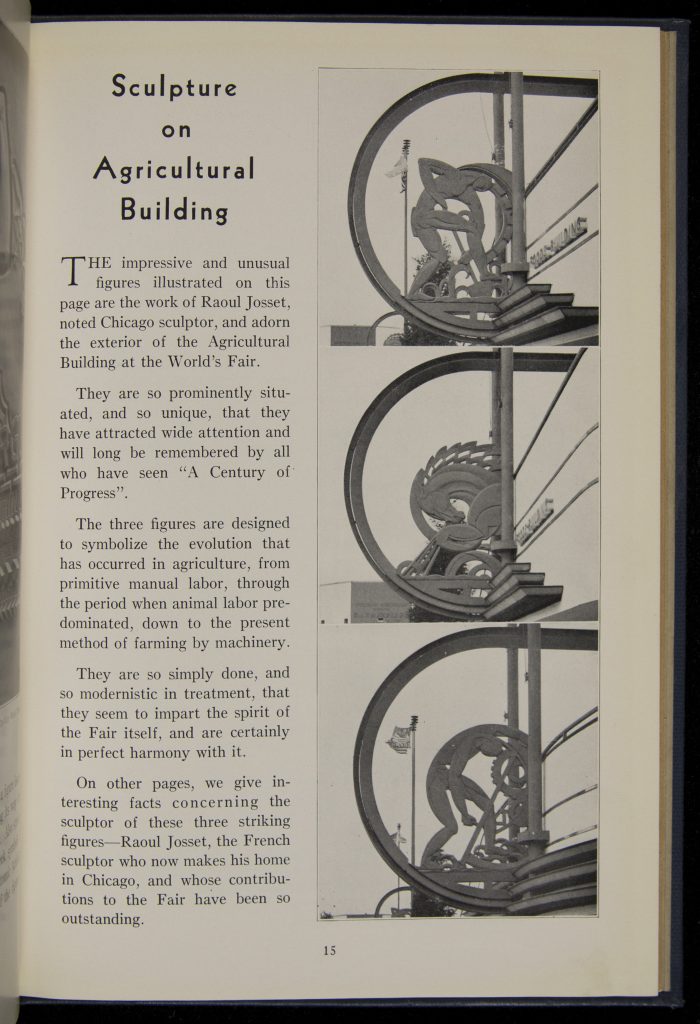

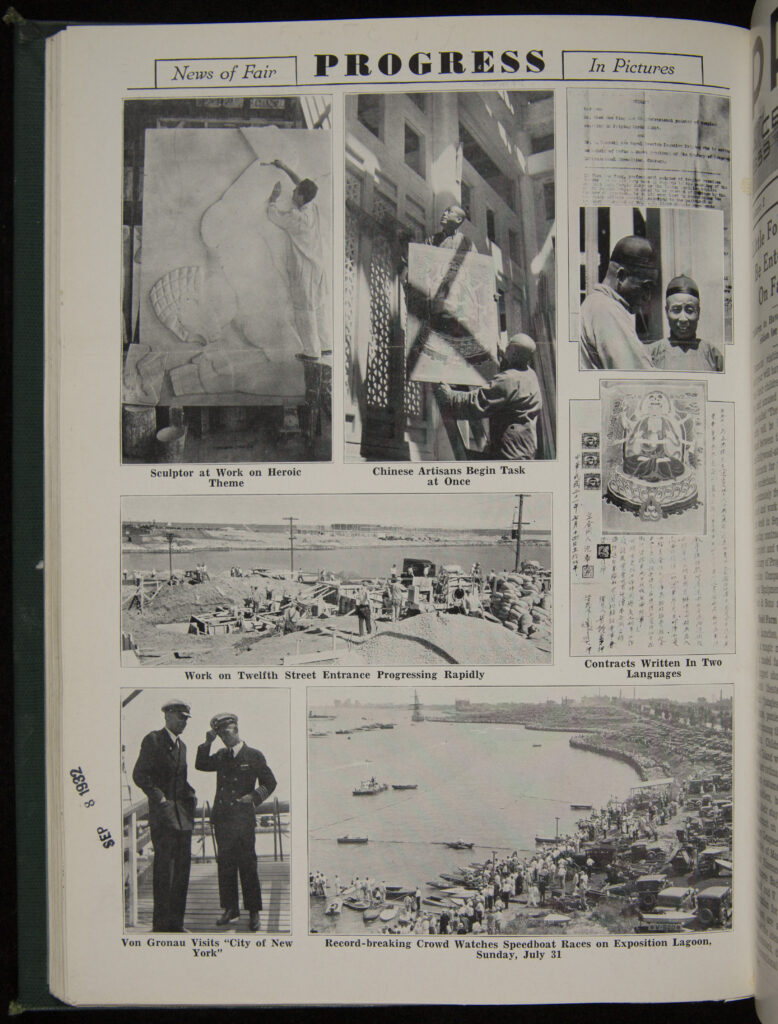

Visitors to the 1933-34 Chicago World’s Fair viewed art all around the fair, through sculptures, paintings, and other artworks created specifically for fair buildings, as well as in exhibits. Neighboring institutions like the Art Institute of Chicago hosted a range of shows featuring loaned works from American museums and collectors, as well as special exhibits for the fair of photography, printmaking, and sculpture. Original artworks also adorned many fair buildings. Much of the art commissioned for the buildings was allegorical in nature, such as these artworks from the Agricultural Building and the Electrical Building. While numerous sculptures, murals, and other artworks were created for the 1933-34 Chicago World’s Fair, little of the fair’s art exists today.

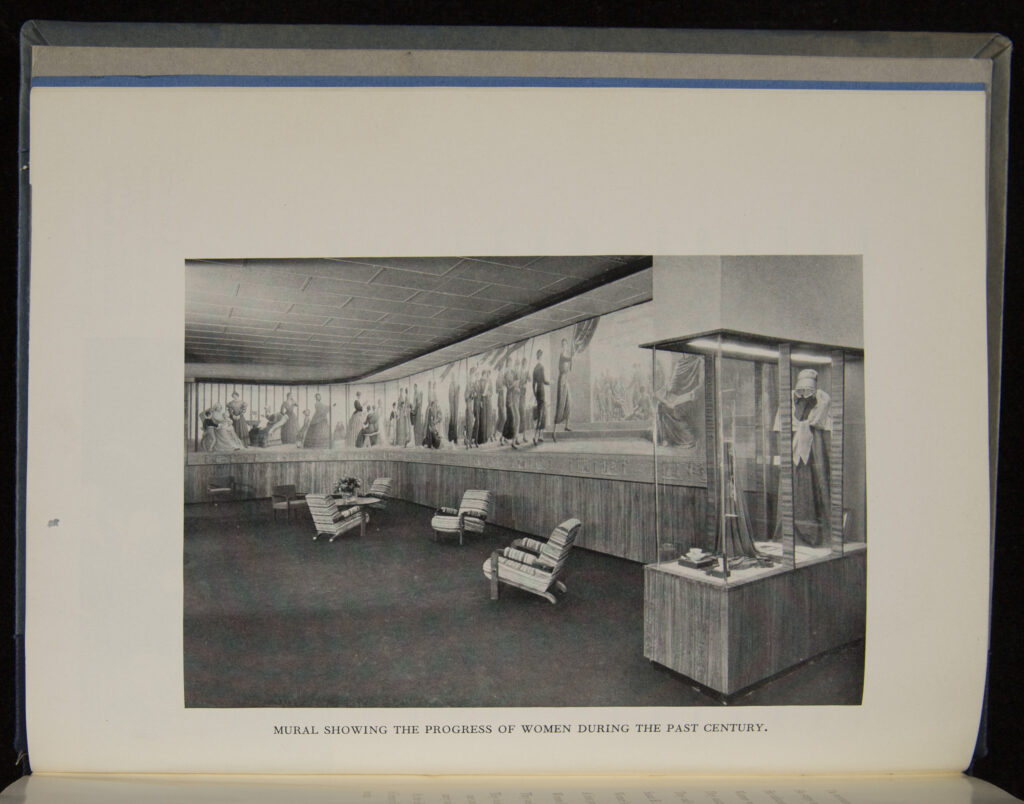

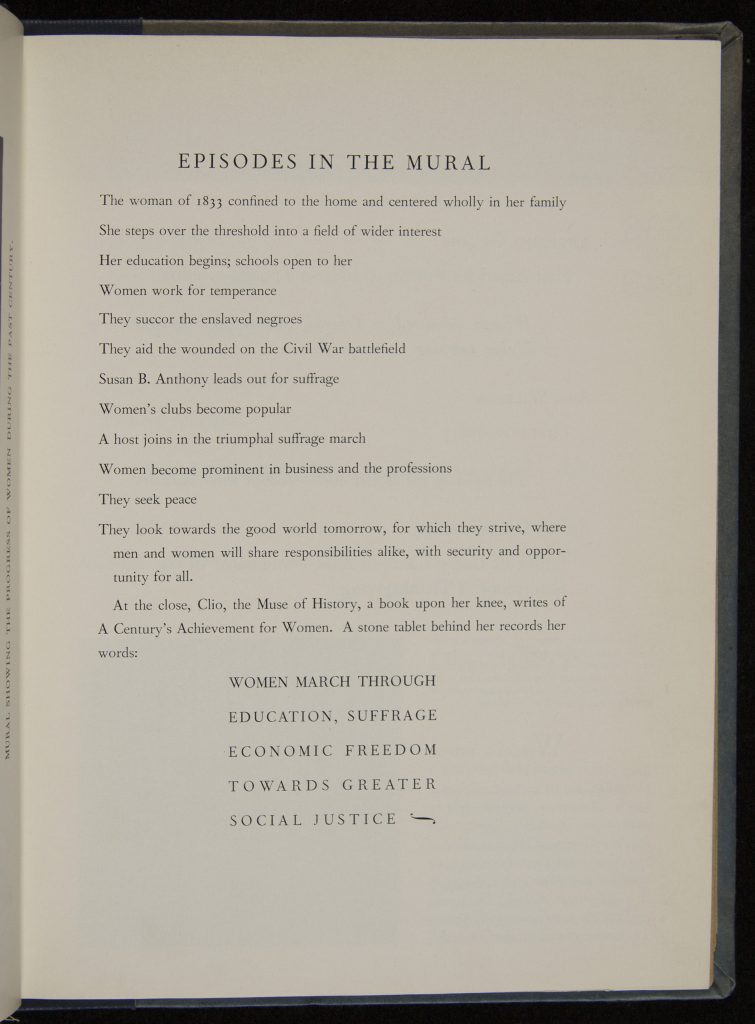

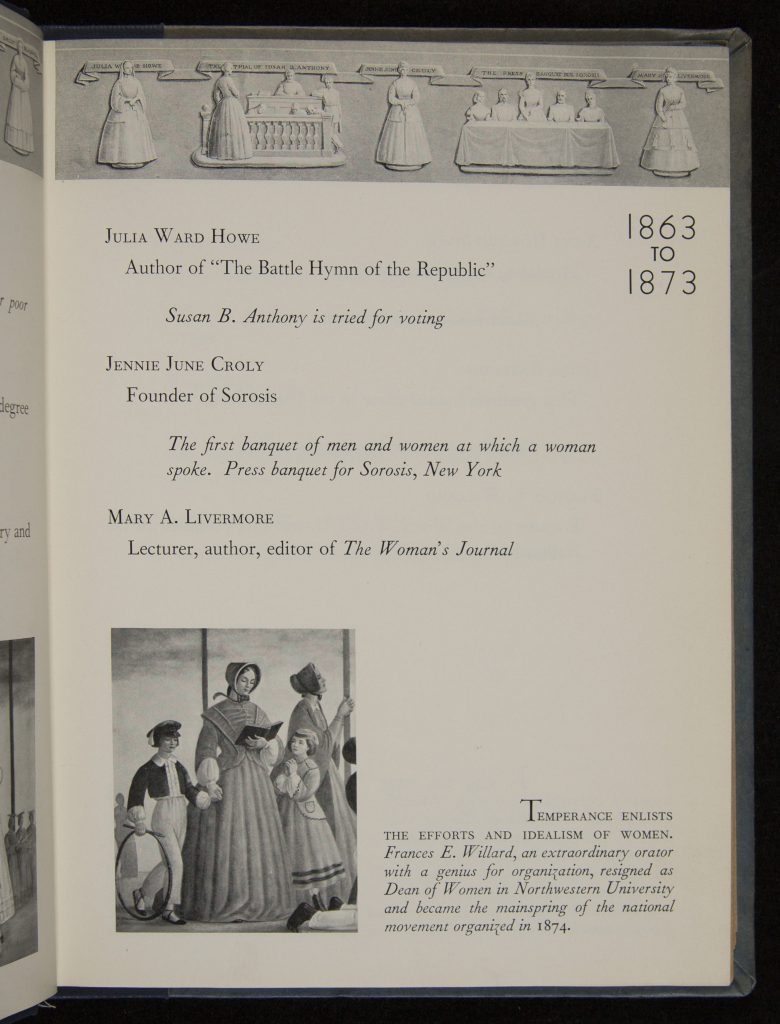

The fair also featured works of art within its buildings and exhibition halls. The sixty foot Progress of Women, or The Onward March of Women mural commissioned for the National Council for Women exhibit in the Social Science Hall is one example. The mural was painted by Hildreth Meière, a mural artist and mosaicist associated with the Art Deco style. The left side of the mural has prison bars painted in the background spaced progressively farther apart until they disappear at the illustration of women’s suffrage. Objects and documents associated with the famous women depicted in the mural rounded out the exhibition. Notably, women of color and working class women were not represented in the mural.

Selection: National Council of Women of the United States, Women Through the Century: A Souvenir of the National Council of Women Exhibit (1933).

Questions to Consider

- Before reading the explanatory text, look at picture of the three sculptures from the Agricultural Building. What do you think the sculptures represent? How does the context of the sculptures as artworks on the Agricultural Building influence your interpretation? How does the textual explanation compare to your interpretation of the images?

- Before reading the explanatory text, look at picture of the relief from the Electrical building. What do you think the sculptures represent? How does the textual explanation compare to your interpretation of the images? Sketch your own allegorical work for the fair’s electrical building, and write an accompanying explanation.

- What episodes in women’s history are depicted in the mural of the progress of women? What groups of women are included in the mural, and what groups of women are not represented?

Chicago and the Fair

The Century of Progress World Exposition got its name from the centennial celebration of the incorporation of the city of Chicago. One of the ways Chicago represented its history at the fair was through a reconstruction of Fort Dearborn, an early nineteenth century United States fort built along the Chicago River. Fort Dearborn holds an important enough place in the history of the city, that it is represented by one of the four stars in the city flag of Chicago. By 1933 Chicago was no longer a frontier outpost, but had become a major national transportation center thanks to the railroads, an industrial meat-processing center, and the second largest city in the United States.

The fairgrounds were built near the museum campus, so in addition to the buildings built specifically for the fair, sites like Soldier Field, and the newly built Adler Planetarium were available for fair events and exhibitions. Institutions across the city capitalized on the interest in the fair such as the newly formed Museum of Science and Industry that opened its doors in 1933. The world’s fair was a huge draw for visitors to Chicago during 1933-34, but Chicago also hoped to attract visitors to see the city as well. During the depths of the Great Depression, the income generated by visitors to the Century of Progress exposition provided a valuable boost to Chicago’s economic well-being.

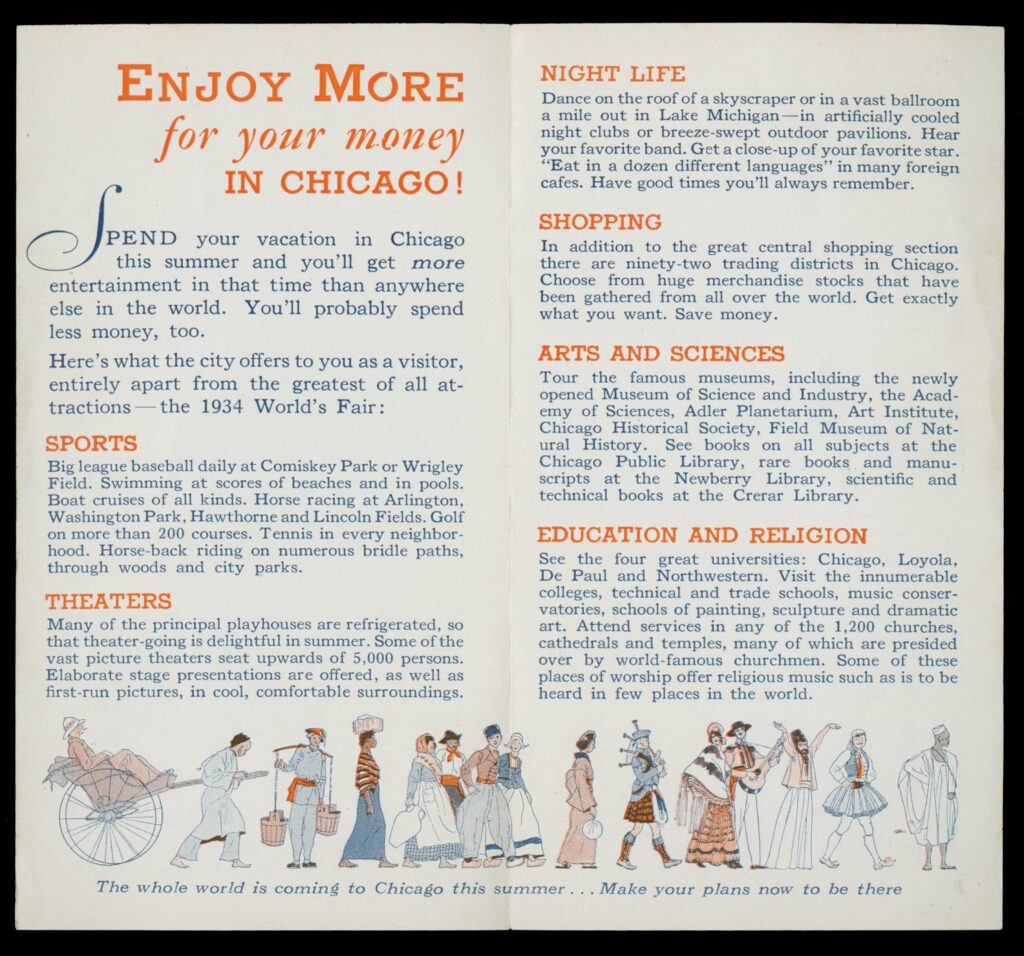

Documents such as Enjoying your vacation days in Chicago provide a sense of the range of opportunities for visitors to spend money in Chicago. The city encouraged visitors to explore the city’s theaters, sports, nightlife, as well as the city’s industrial side such as the Union Stock Yards and the Board of Trade. Tourist information also highlights what a city is proud of. Maps and other types of tourist information were sent to towns across the country to drum up interest in the World’s Fair, and the railroads that hoped to bring visitors to Chicago for the fair helped greatly with distribution of travel information about the exposition.

Selection: Enjoying Your Vacation Days in Chicago (1933).

Questions to Consider

- What types of sightseeing does the brochure, Enjoying your vacation days in Chicago suggest? What does this document illustrate about travel to Chicago during the Century of Progress?

- How does a recreation of Fort Dearborn, an early settlement near Chicago, illustrate the fair’s theme of progress?

- Compare the panoramic view and the map of the fair from the second page of Progress; a Century of Progress International Exposition to a current picture of Chicago in the same area. What buildings and sites remain? What current landmarks can you identify?

Remembering the Fair

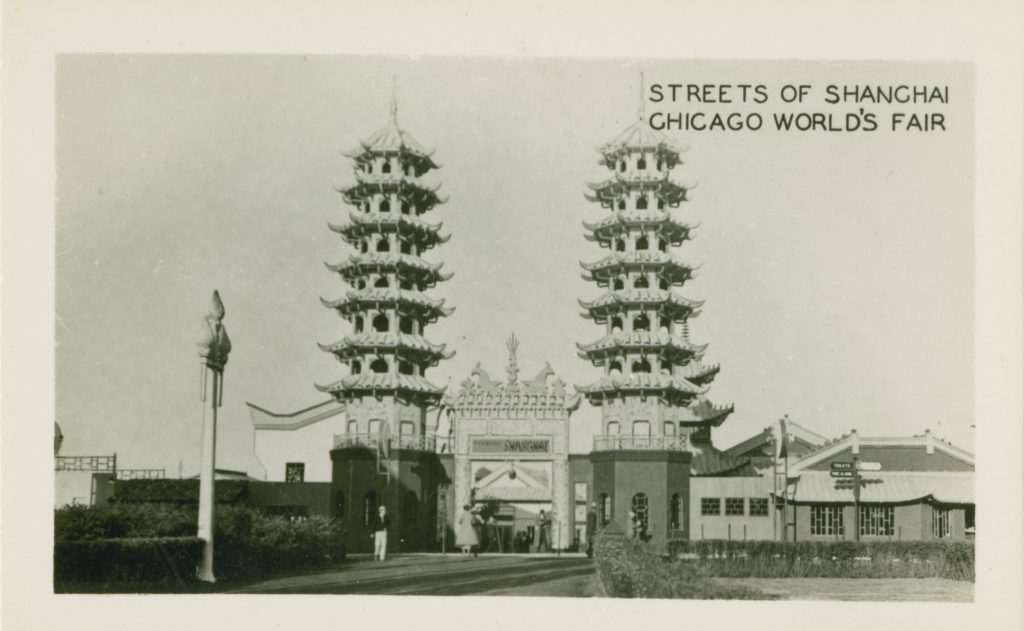

While over 39 million people visited the Century of Progress between 1933 and 1934, many other people experienced the Century of Progress secondhand through promotional materials, news, as well as postcards and letters from friends and family who made the trip to Chicago. Many fair goers purchased souvenirs to remember their trip to the 1933-34 Chicago World’s Fair. The range of souvenirs available from toys and puzzles, to thermometers, stamps, postcards, and buttons was extensive. The souvenir booklet in this section belonged to a couple from Sommerville Ohio. In addition to all of the information about the fair, the booklet includes space for fairgoers take notes and write about their experiences, which the owners of this booklet did.

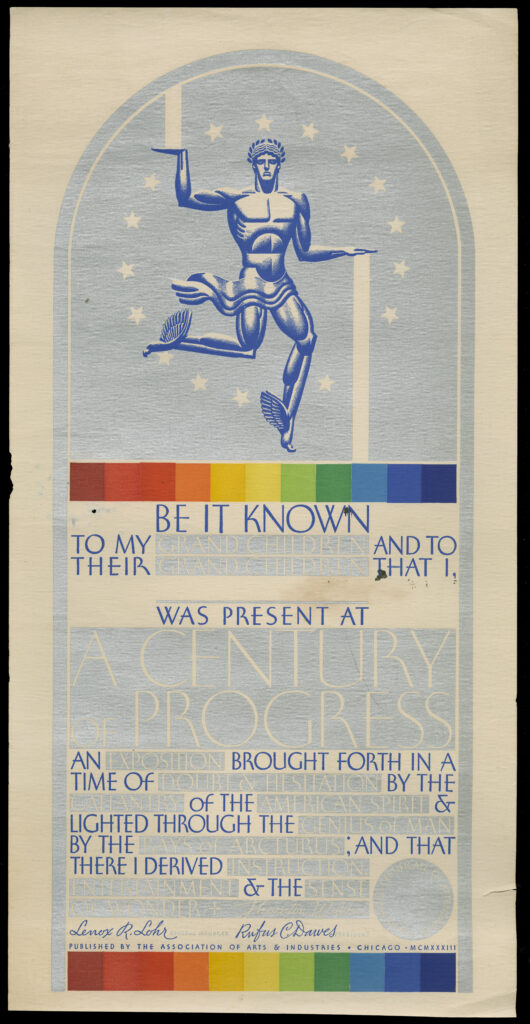

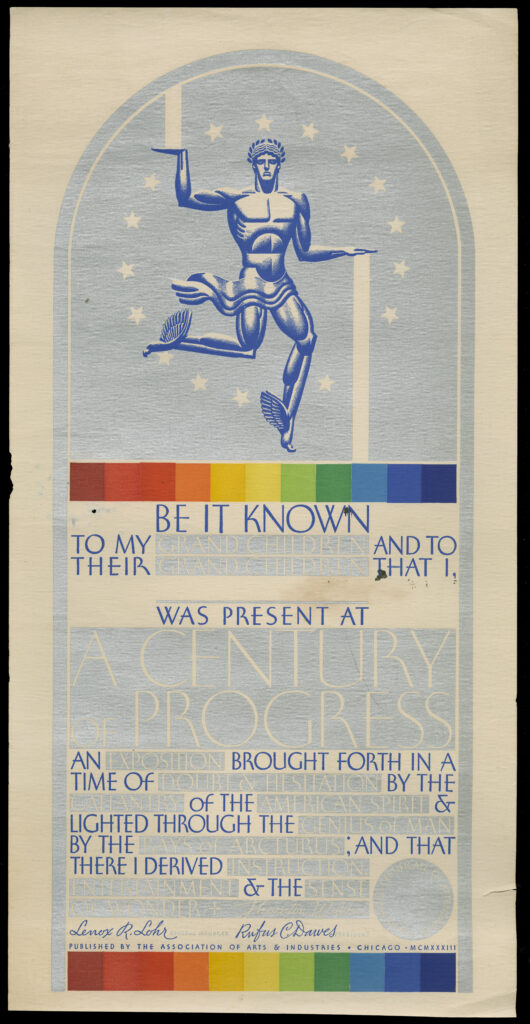

For many fair visitors, visiting the Century of Progress exposition was not only an once-in-a-lifetime experience, but as the broadside in the section suggests, something worthy of telling one’s children and grandchildren about. Although most of the art, buildings, and exhibit pieces from the fairground are gone or scattered across the country, the fair lives in through the material and documentary record, as well as in Chicago memory as one of the four stars in the Chicago city flag.

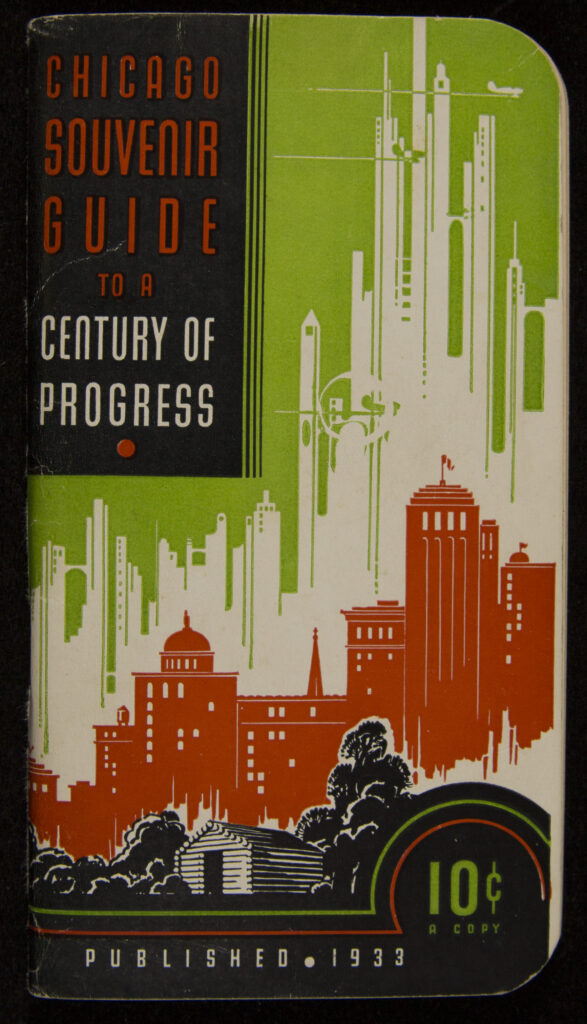

Selection: Chicago Souvenir Guide to a Century of Progress (1933)

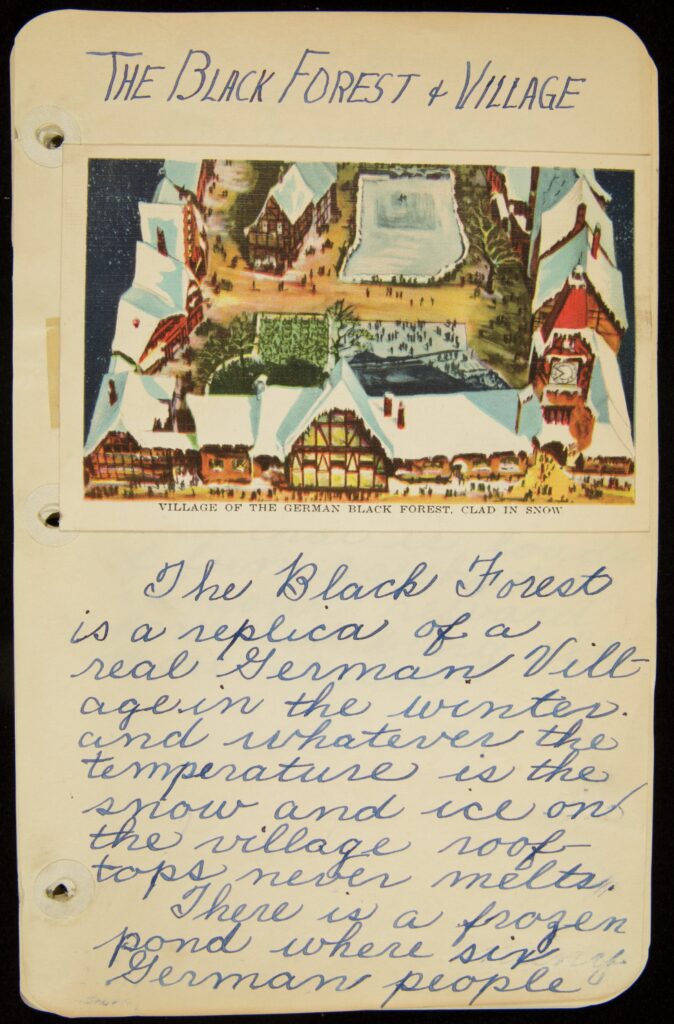

Selection: Claire Lieber Crews Century of Progress Notebook

Questions to Consider

- Look at the souvenir documents in this section. What did the makers want people to remember about the fair?

- Read Claire Crews journal entry. What stood out to Claire, a child visiting the fair, about her experience in the German Village exhibit?

- Look at the cover of the souvenir booklet, how does the cover illustrate the theme of progress? According to the text, what are some of the most noteworthy things about the exposition?

Further Reading

Ganz, Cheryl. The 1933 Chicago World’s Fair: A Century of Progress. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008.

Rydell, Robert W, Laura B. Schiavo, and Robert Bennett. Designing Tomorrow: America’s World’s Fairs of the 1930s. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

Sokol, David M. “Building a Century of Progress: the Architecture of Chicago’s 1933-34 World’s Fair by Lisa D. Shrenk.” The Journal of American Culture. 31.2 (2008): 211-212.