Introduction

The Mexican Revolution began quietly on November 20, 1910, when Francisco I. Madero issued a manifesto calling for the overthrow of the military dictator Porfirio Diaz who had ruled the country for three decades. Madero had been defeated in a rigged presidential election and wrote from exile in the United States. Few people seemed to notice his manifesto. But two of his followers, Pancho Villa and Pasqual Orozco, took up arms in the northern state of Chihuahua and began attacking federal troops. A year and a half later, the rebels captured the large port city of Ciudad Juarez and suddenly the regional rebellion blossomed into a national revolution. Diaz resigned in May 1911.

The documents that follow offer different perspectives on the meaning and experience of the revolution. Many of these sources were created by people who lived through or participated in the revolution.

Over the next two decades, the country endured intense political upheaval and widespread violence. Madero was overthrown and executed in 1913 by the military dictator Victoriano Huerto, who was himself overthrown the next year by revolutionaries who then turned to fighting each other. This pattern continued into the 1930s: short-lived regimes ended in assassination and rebellion, with no mechanism for peaceful succession. Historian William H. Beezley writes that “one in seven of the nation’s population died in the fighting, from wounds, or from disease or deprivation or fled into exile as a result of the revolution in just the decade after 1910 (nearly two million people in all).”

The revolutionaries themselves were a diverse group, representing different class and ethnic backgrounds, including subsistence farmers, small-scale ranchers and miners, and craftsmen. But, as Beezley explains, they shared the goal of limiting the economic and political power of foreigners and Mexico City elites. They sought “to create a nation that offered social mobility to all its citizens, the opportunity to participate in their government, the prospect of economic justice, and the promise of legal equality.” The decades of revolution and civil war brought the nation closer to these goals, though at great human cost.

The documents that follow offer different perspectives on the meaning and experience of the revolution. Many of these sources were created by people who lived through or participated in the revolution. A number of the authors are American and reflect the United States’ deep political and economic involvement in the affairs of its neighbor to the south. For additional sources on the history and culture of Mexico, see Caste and Politics in the Struggle for Mexican Independence and Art and Exploration in the American West and Mexico.

Essential Questions

- What social conditions and conflicts contributed to the revolution? How do the writers and artists represented in this collection explain their support of or opposition to the revolution?

- How did the United States seek to influence events in Mexico? How did Americans in Mexico represent their experience of the revolution?

- How did Mexican artists respond to the revolution? What visual record did they create of the people who led and participated in the war?

Picturesque Mexico

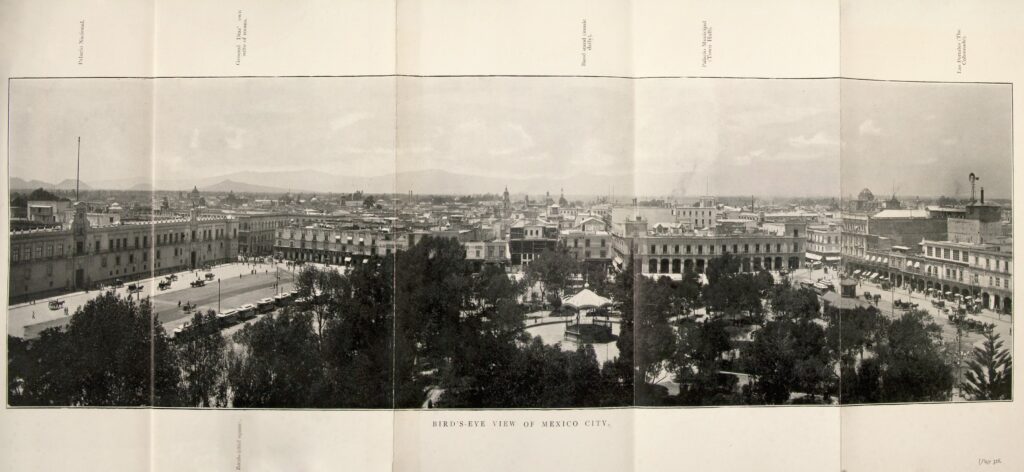

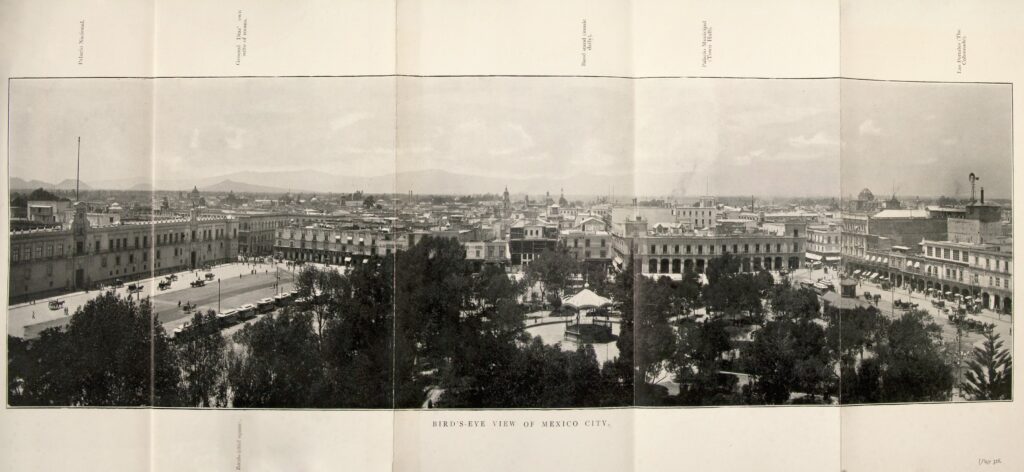

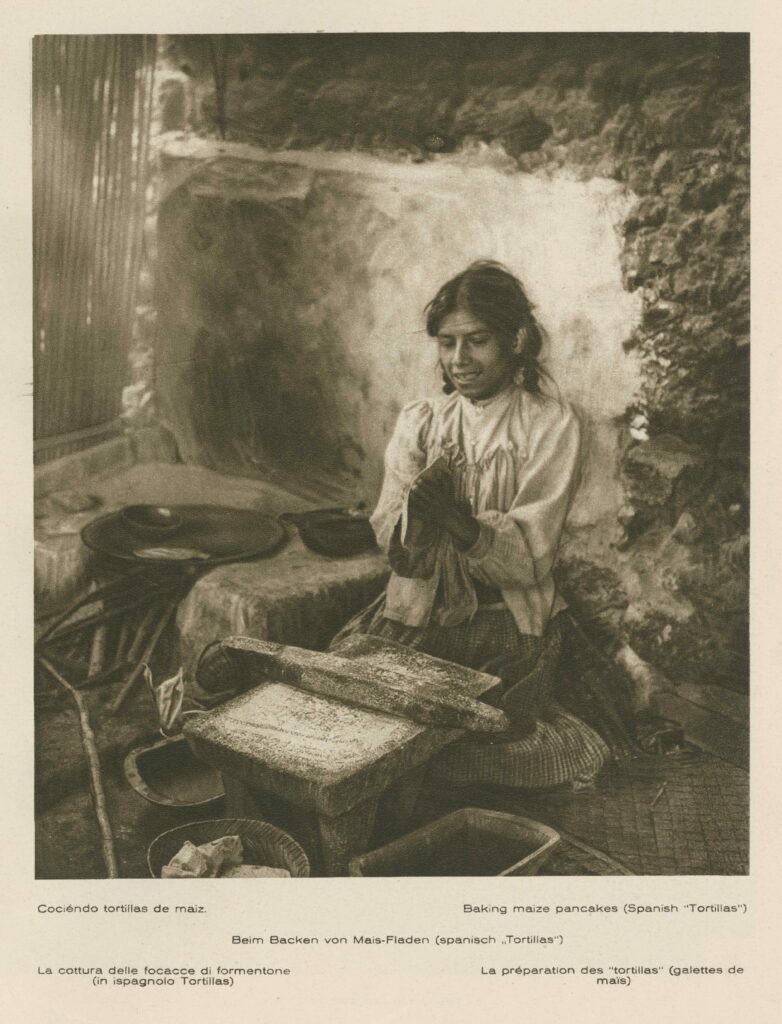

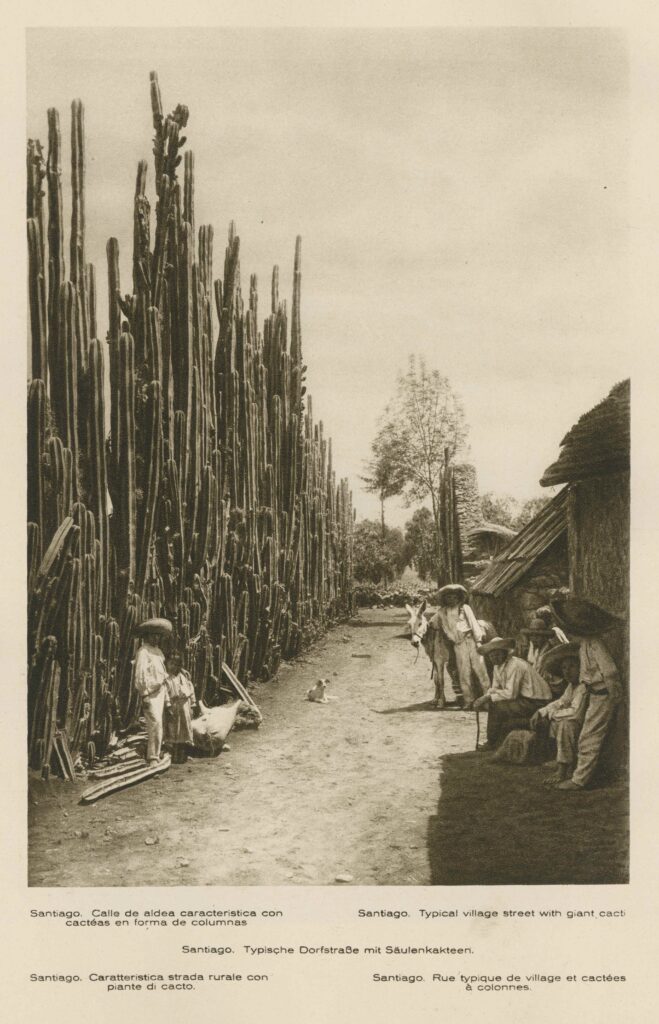

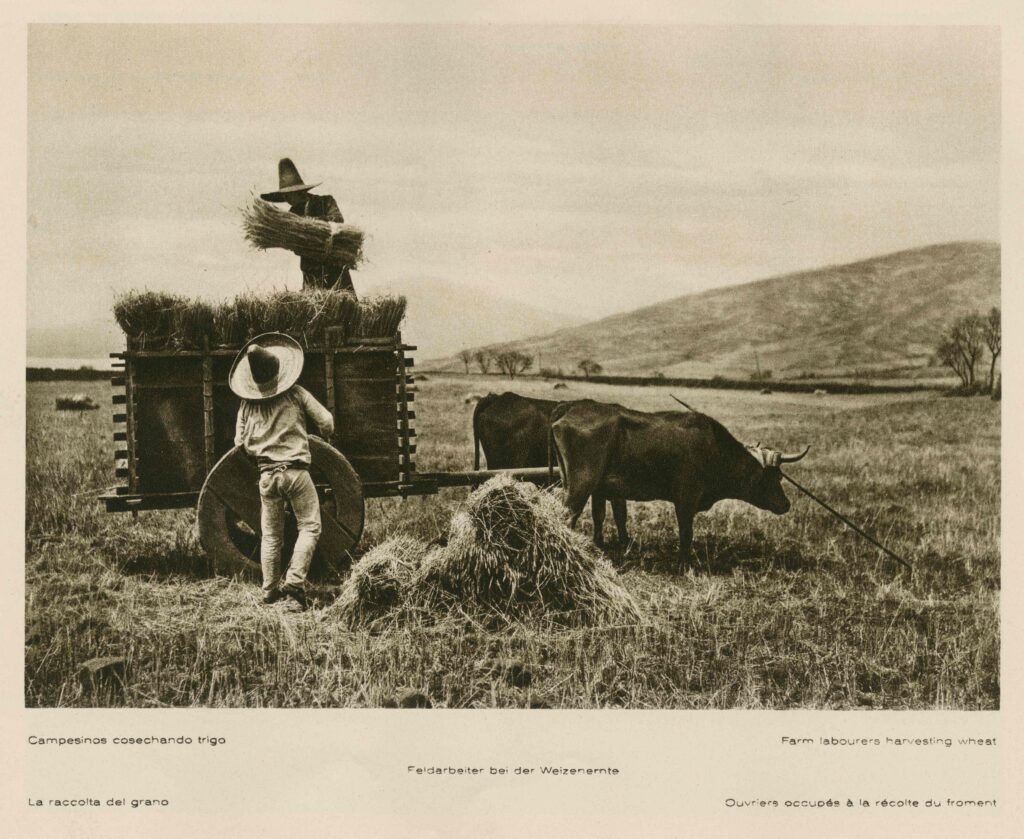

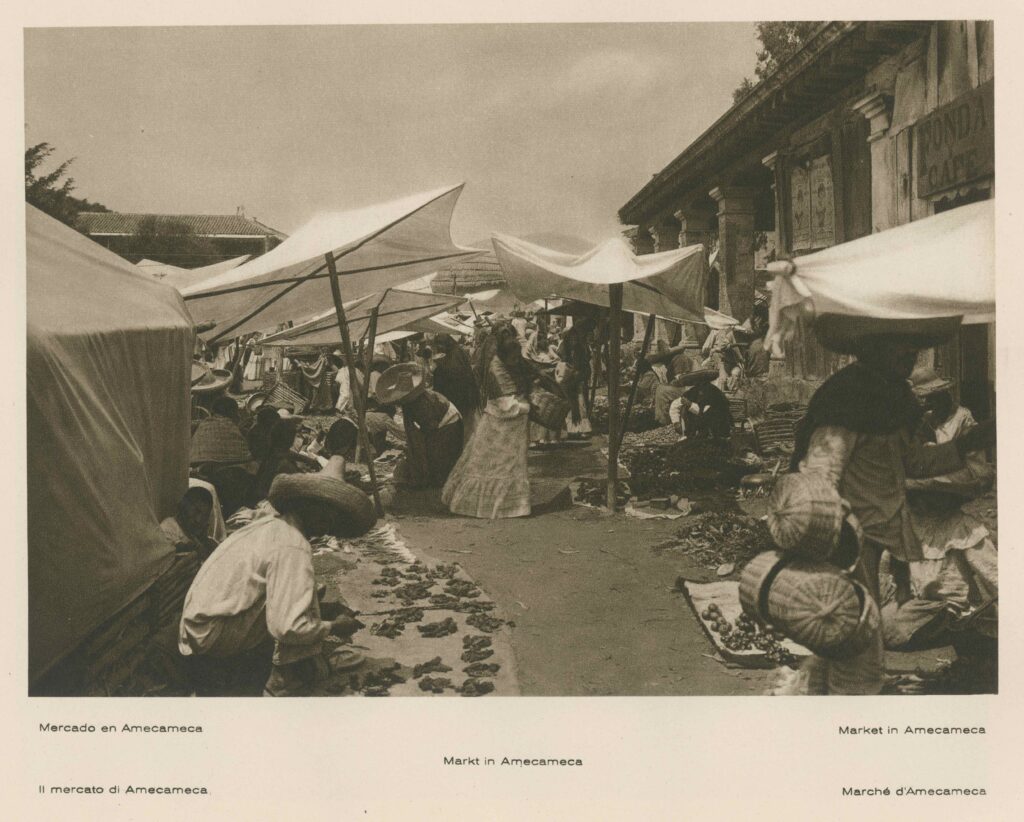

In the decades leading to the revolution, Mexico attracted a large number of foreign visitors. President Porfirio Diaz encouraged foreign investment in the country’s natural resources and Great Britain and the United States, in particular, had significant financial interests in Mexico. Mexico also held, in the words of the English author Ethel Tweedie, a reputation for “history, romance, picturesqueness, beauty.” The photographs below offer visual testimony to the beauty of Mexico’s urban and rural landscapes at the start of the twentieth century.

The photograph above is from Tweedie’s biography of Diaz, the military dictator who was defeated by Francisco I. Madero’s supporters in April 1911 in the second year of the revolution. Tweedie writes glowingly of Diaz as “a great ruler, the maker of a nation, just a fine, strong, handsome man.”

Subsequent photographs appeared in a book by Walther Staub and Hugo Brehme, published in the mid-1920s, fifteen years into the revolution. While the work is largely concerned with Mexico’s topography and natural resources, Staub takes time in his preface to describe Diaz as “Mexico’s greatest statesman” who brought 33 years of peace and the highest economic development to the country. The photographer, Brehme, was born in Germany in 1882. He arrived in Mexico in 1906 and spent the rest of his life there. The market portrayed in the last photograph is in Amecameca, a town in central Mexico that was known as a Zapatista stronghold.

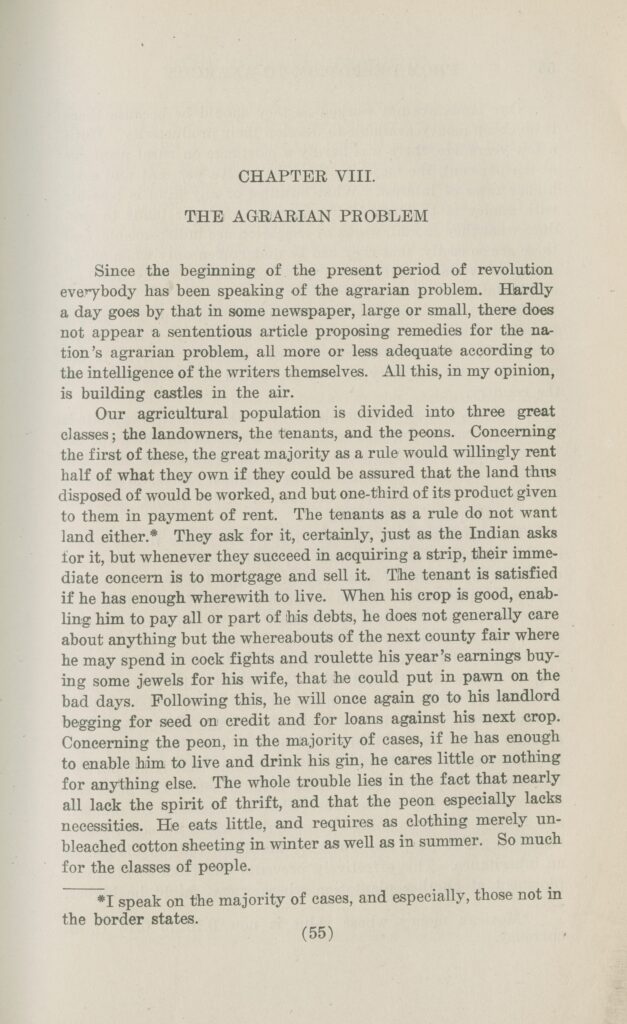

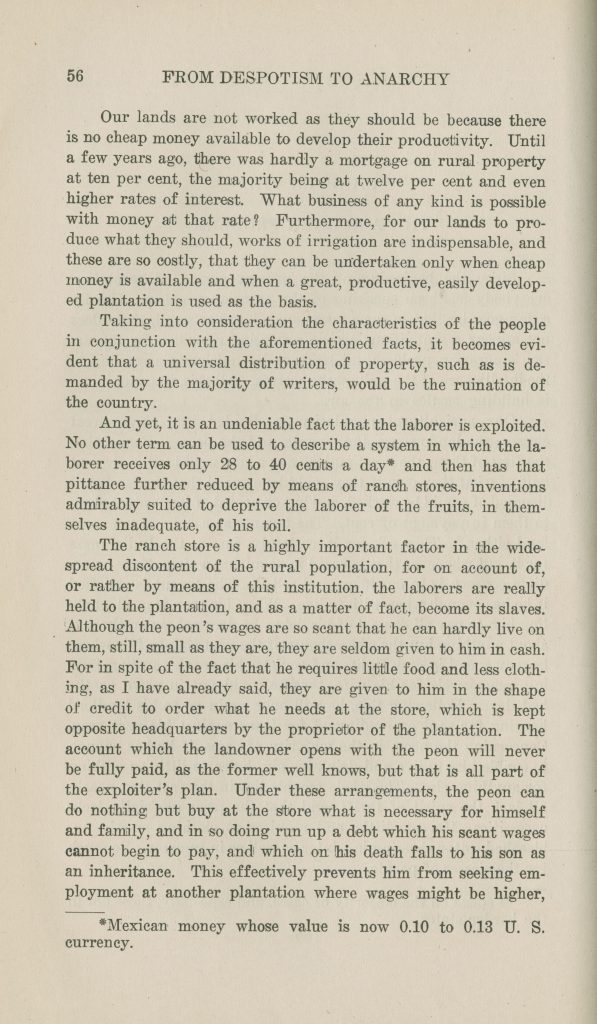

Mexican legislator Ramón Prida offers an account of the complicated social conditions, particularly in the countryside, that underlie these “picturesque” photographs. Writing in 1913, Prida was deeply critical of both the “iron hand” of the Diaz regime and the “catastrophe” of the revolution, as his title—From Despotism to Anarchy—suggests. In the passage below, Prida analyzes “the agrarian problem,” that is, the concentration of wealth and land in the hands of a few.

Selection: Ramón Prida, “The Agrarian Problem,” 55-57, in From Despotism to Anarchy (1914).

Questions to Consider

- Examine the photographs of Mexico City and of rural Mexico. What makes these scenes “picturesque” or beautiful? How would they compare to the landscapes that these authors and photographers would have known from England, the United States, and Europe?

- What do the photographs suggest about the differences between urban and rural life in Mexico in the first decades of the twentieth century?

- How does Prida portray the agricultural population in Mexico? Why does he write that renters, like Indians, don’t actually want land, even though they ask for it? What is his tone? How would you characterize Prida’s perspective or biases based on this passage?

- Why does Prida write, “it is an undeniable fact that the laborer is exploited”? What are the conditions of the agricultural workers’ exploitation?

Mapping the War

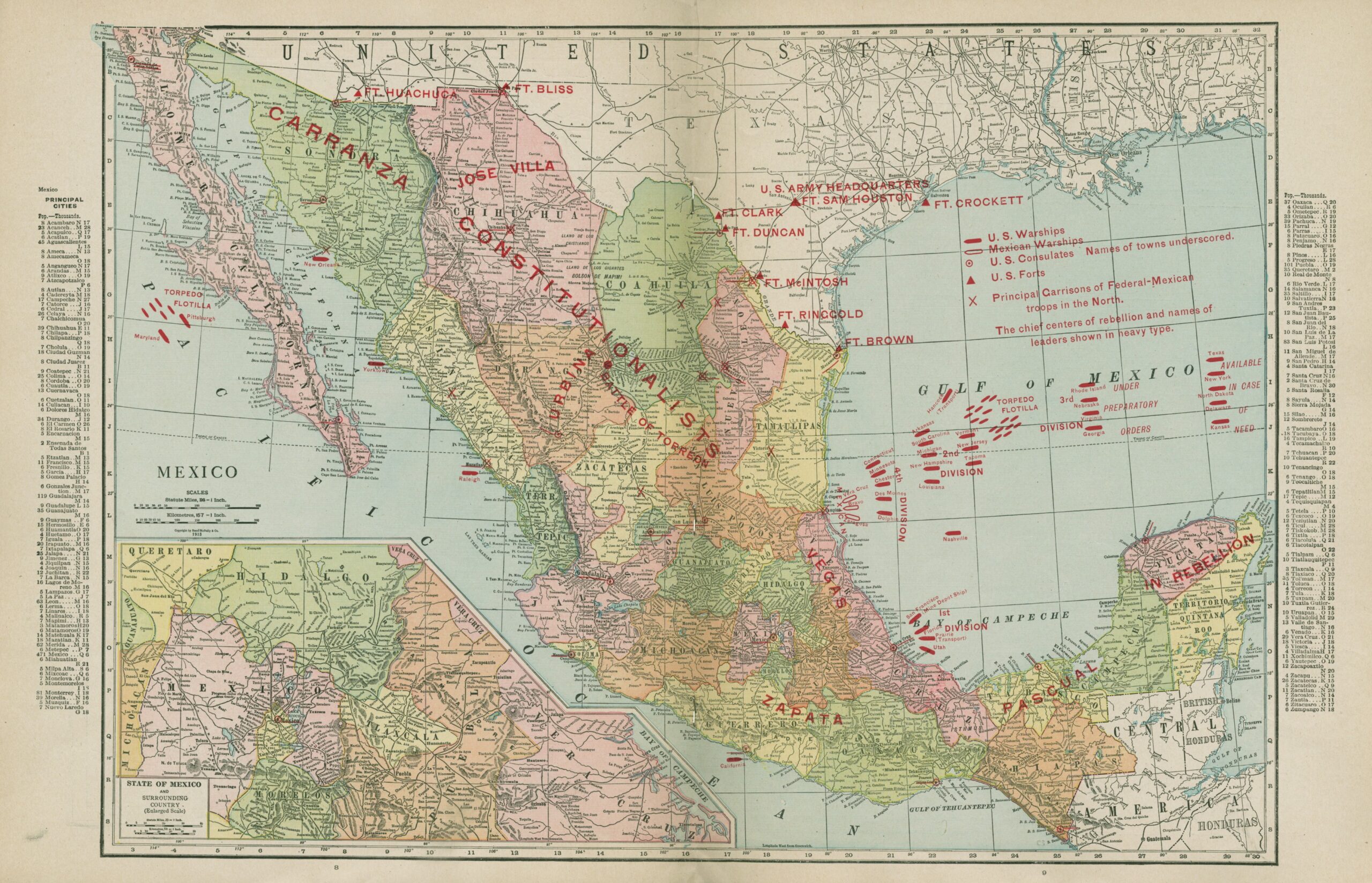

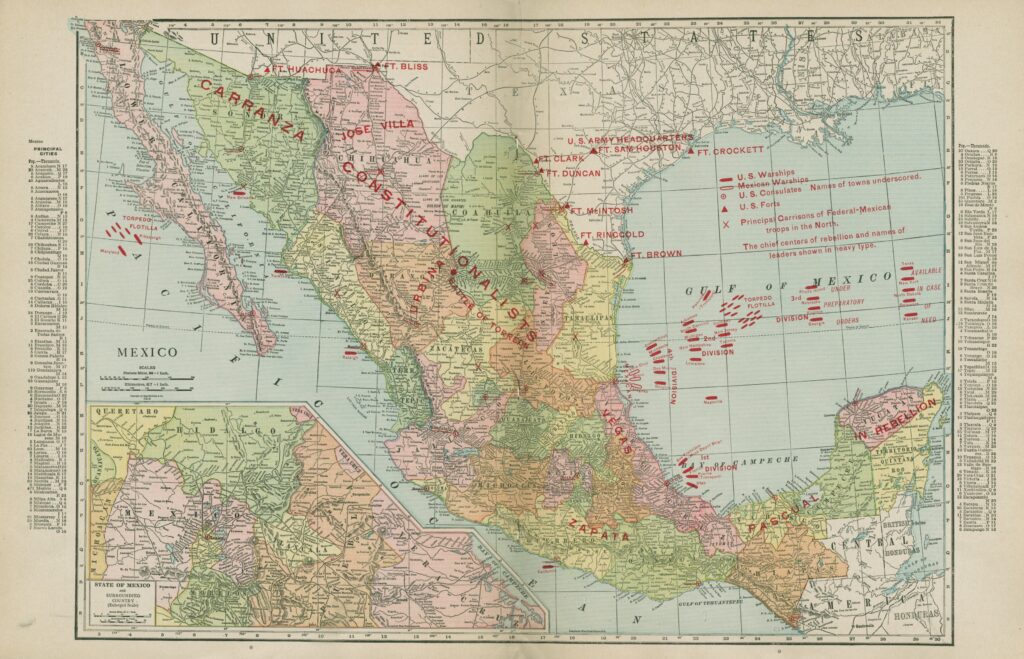

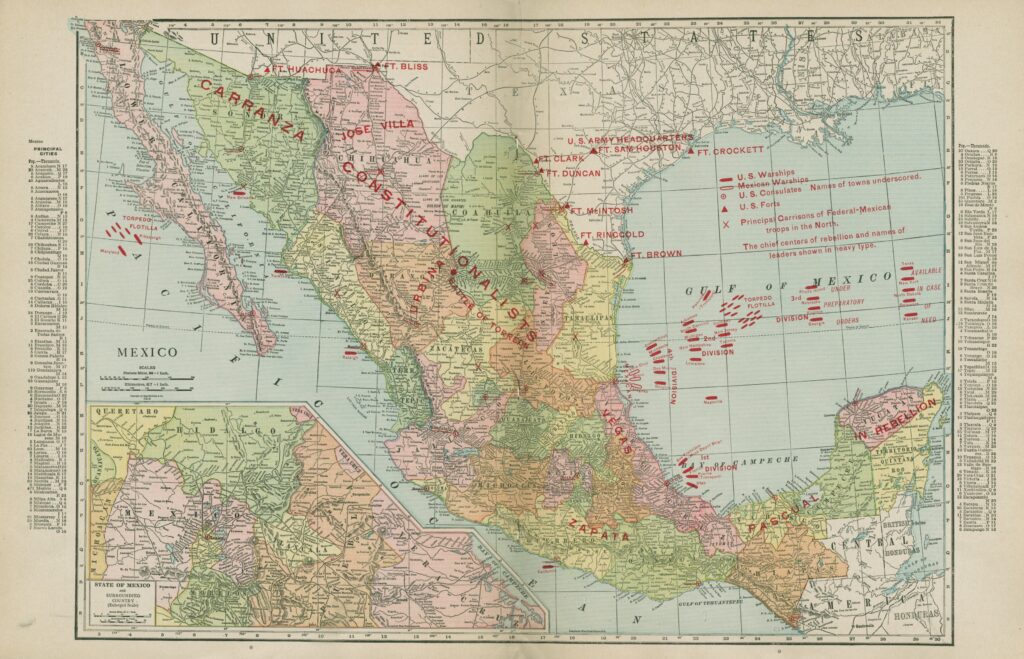

The Chicago-based mapmaking and printing company Rand McNally published this representation of the Mexican Revolution in 1914. That year, revolutionary leaders, including Emilio Zapata, Pancho Villa, and Venustiano Carranza, organized as the Constitutionalists and overthrew the military dictator Victoriano Huerto. During the two years that followed, Constitutionalist leaders fought with each other and the revolution developed into a civil war. The United States military became increasingly involved, invading Mexico in 1916 at Vera Cruz and Tampico and pursuing Villa through the state of Chihuahua.

Although we more commonly associate Rand McNally with road and railway maps, the map here identifies the locations of U.S. and Mexican warships, forts, and garrisons as well as the geographic regions associated with each Constitutionalist leader.

Questions to Consider

- Locate the regions on the map that are associated with specific Constitutionalist leaders. How many are there? Which regions do they control?

- Identify U.S. forts and warships on the map. Where are they located? What does the map tell you about U.S. military strategy?

The U.S. Presence

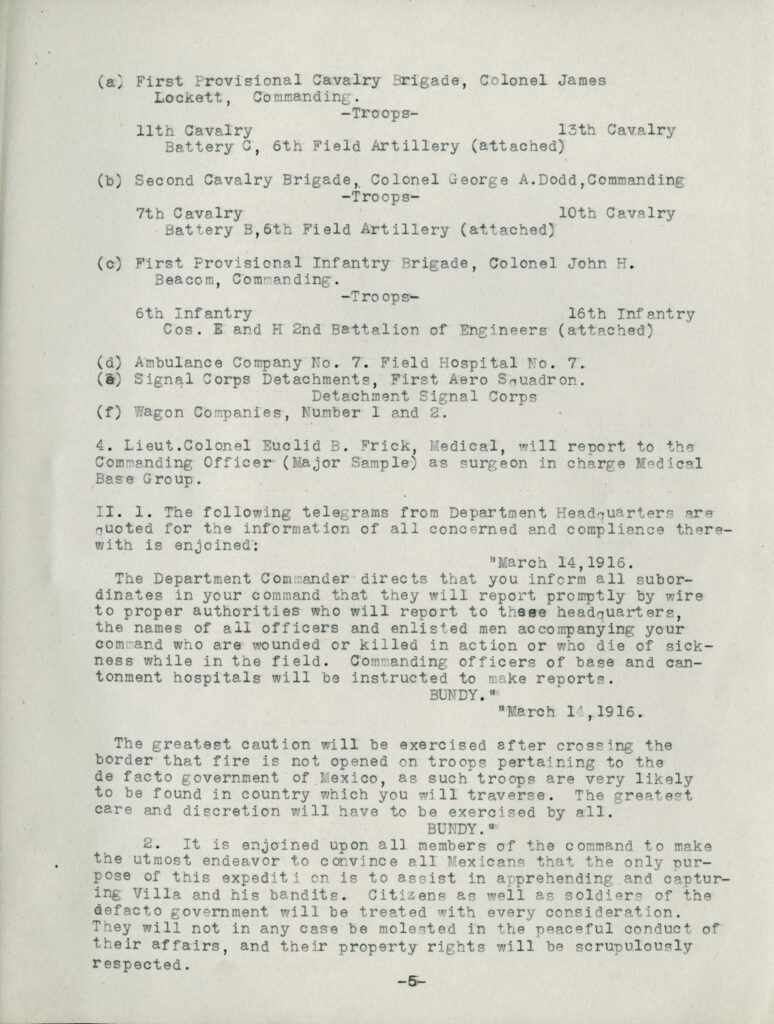

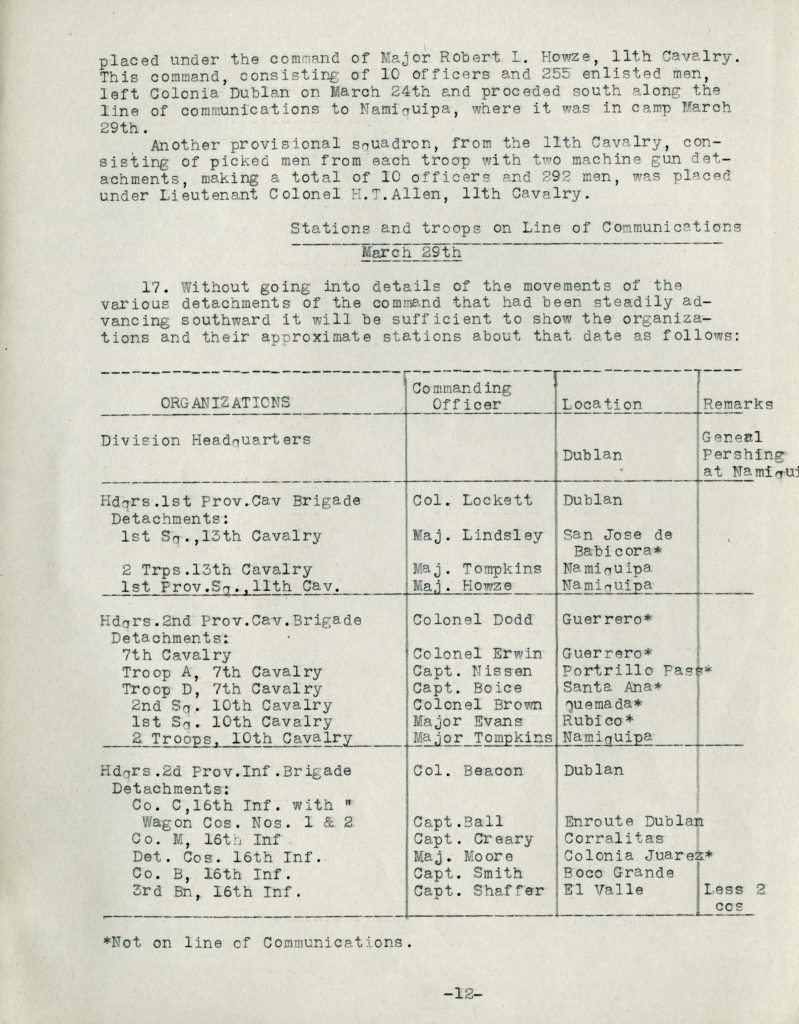

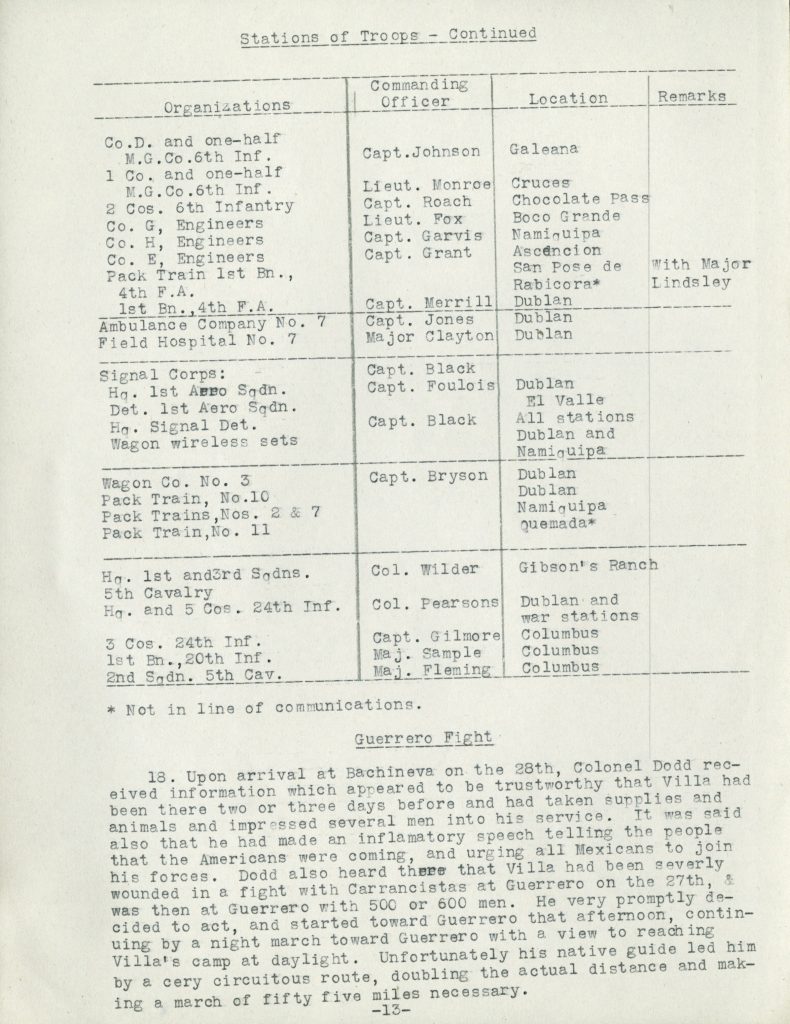

The United States had strong economic interests in Mexico before 1910. Once the revolution began, President Woodrow Wilson’s administration tried to influence events to protect these interests and the large number of U.S. citizens in Mexico. The documents below reference two especially notorious instances of U.S. intervention: First, in 1913, the U.S. ambassador to Mexico, Henry Lane Wilson, plotted with Victoriano Huerta in his successful coup against the democratically-elected Francisco I. Madero. Huerta established a harsh military dictatorship. Woodrow Wilson soon turned against him and recalled Henry Lane Wilson from his diplomatic post. Second, U.S. General John J. Pershing led 10,000 U.S. troops hundreds of miles into Mexico in an unsuccessful quest to capture Pancho Villa. The United States had backed Villa in 1913 and 1914 and provided him with weapons. But in 1916, after the Constitutionalists defeated Huerta and turned to fighting each other, the United States shifted its support to Carranza. In retaliation, Villa and his soldiers attacked the border town of Columbus, New Mexico. The United States then ordered Pershing’s “punitive expedition” against Villa. (Soon after, Pershing became famous for his military leadership in World War I.) This document is an excerpt from General Pershing’s report on the punitive expedition into Chihuahua in pursuit of Pancho Villa.

Selection: John J. Pershing, “Report by Major General John J. Pershing, Commanding, of the Punitive Expedition,” 5, 12-13 (1916).

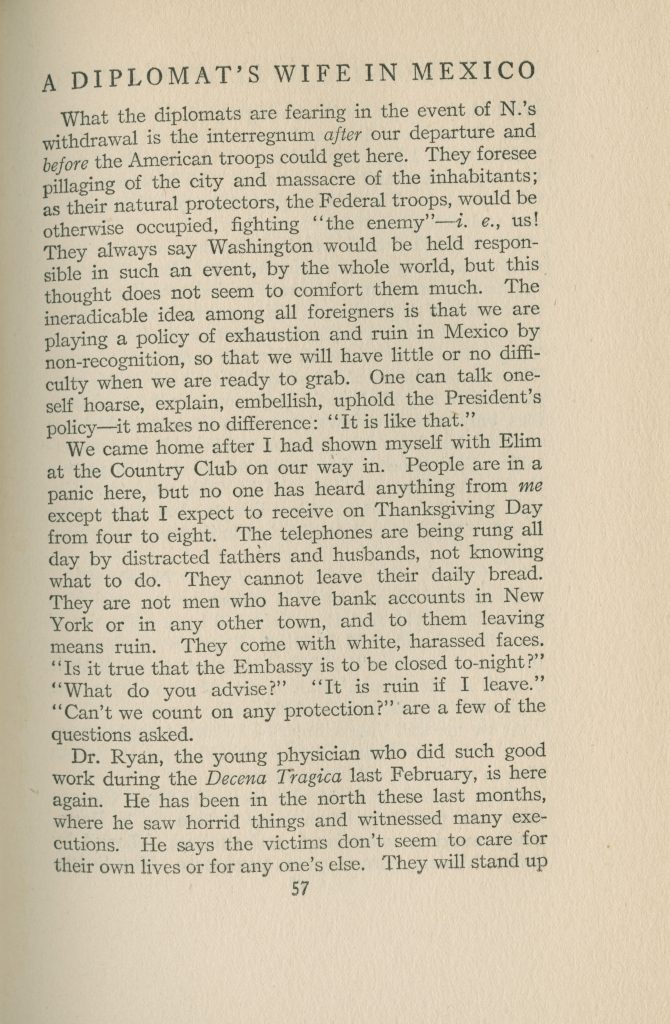

In the selection of texts below, American writer Edith O’Shaughnessy provides an account of her experiences in Mexico under the Huerto regime. O’Shaughnessy was married to a U.S. diplomat, Nelson O’Shaughnessy, and lived among Mexico’s foreign elite. She and her family fled Mexico when the Constitutionalists overthrew Huerta in 1914. In the book’s forward, written from the safety of New York, O’Shaughnessy laments the damage the war has inflicted on Mexico: “As for beautiful Mexico—her industries are dead, her lands laid waste, her sons and daughters in exile.”

Selection: Edith O’Shaughnessy, A Diplomat’s Wife in Mexico: Letters from the American Embassy at Mexico City, Covering the Dramatic Period Between October 8th, 1913, and the Breaking Off of Diplomatic Relations on April 23rd, 1914, frontispiece, title page, 57-59, 184-185 (1916).

In contrast, Mexican legislator Ramón Prida criticizes U.S. military interventions in Mexico. Prida spent some years in exile in the United States and returned to Mexico after the revolution.

Selection: Ramón Prida, “American Policy,” in From Despotism to Anarchy, 245-247 (1914).

Questions to Consider

- How does Edith O’Shaughnessy portray life in Mexico under Huerta’s rule? In what ways does ordinary life seem to continue and in what ways does she observe the impact of the war?

- How would you characterize O’Shaughnessy’s relationship to Mexican people? What evidence is there to suggest that her experiences, as a wealthy foreigner and the wife of diplomat, are quite different from those of ordinary citizens?

- How does O’Shaughnessy describe the two sides of the conflict (Huerta’s federal troops and the Constitutionalist rebels) and the violence that each inflicts?

- According to Prida, what have been the reasons for U.S. intervention in Mexico? What does Prida criticize and what does he find to praise about U.S. policy toward Mexico? Why does “the spectre of U.S. intervention…strike terror to all Mexican politicians”?

- Why does Pershing instruct U.S. commanders “to convince all Mexicans that the only purpose of this expedition is to assist in apprehending and capturing Villa and his bandits”? What other purposes might Mexicans suspect the U.S. troops of?

- Examine Pershing’s account of the Guerrero fight. What light does it shed on Villa’s actions and on popular sentiment toward the American soldiers?

Portraits of the Revolution

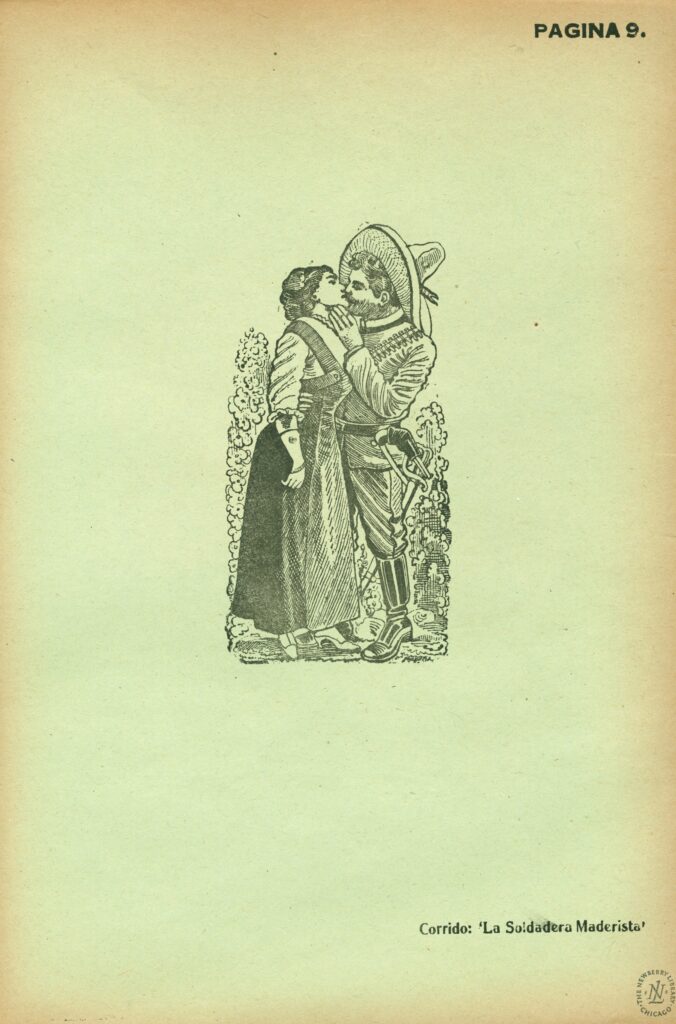

The images in this section suggest the rich visual culture—and dramatic figures—associated with the Mexican Revolution. José Guadalupe Posada was a popular artist in Mexico City in the decades leading up to the Mexican Revolution. His engravings appeared on thousands of broadsides that circulated throughout the streets of Mexico City. The broadsides often responded to current events and scandals and served as a kind of pictorial journalism. Posada died in 1913, but his engraved plates continued to be printed throughout the twentieth century. These examples were printed in Mexico City in 1943.

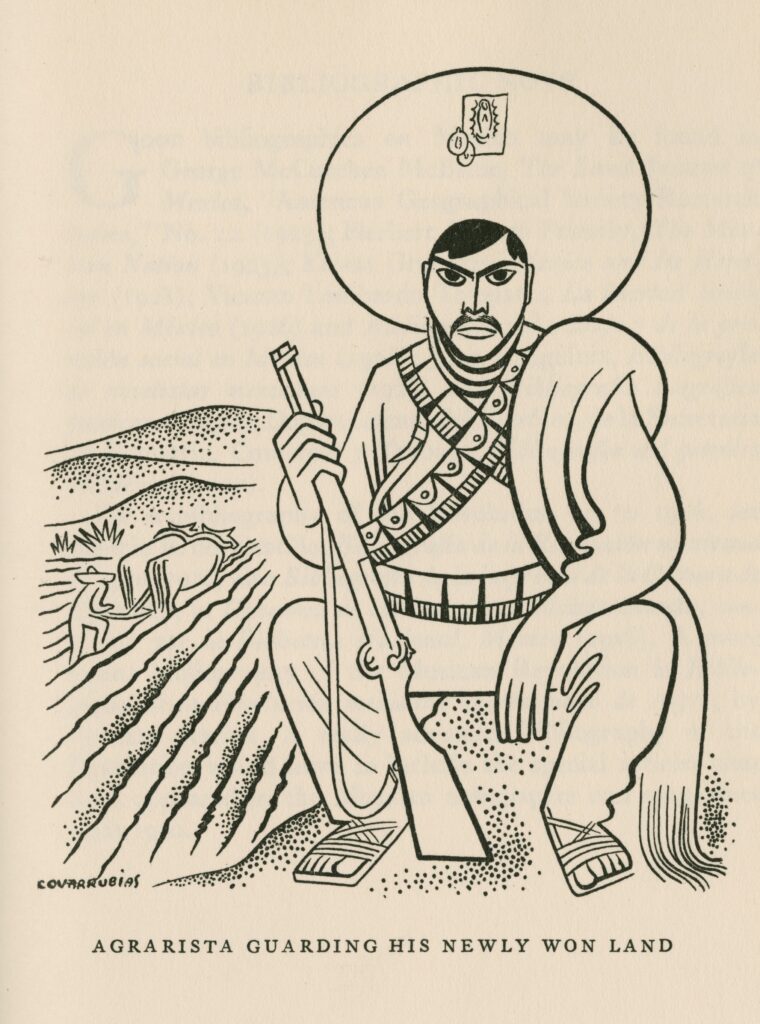

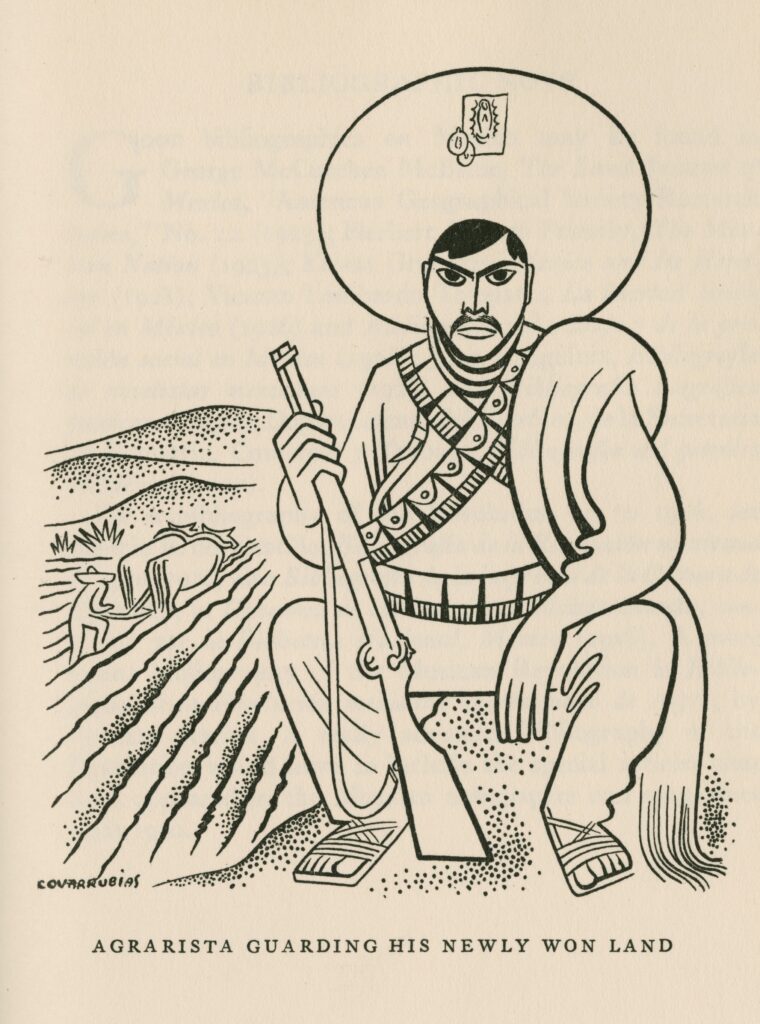

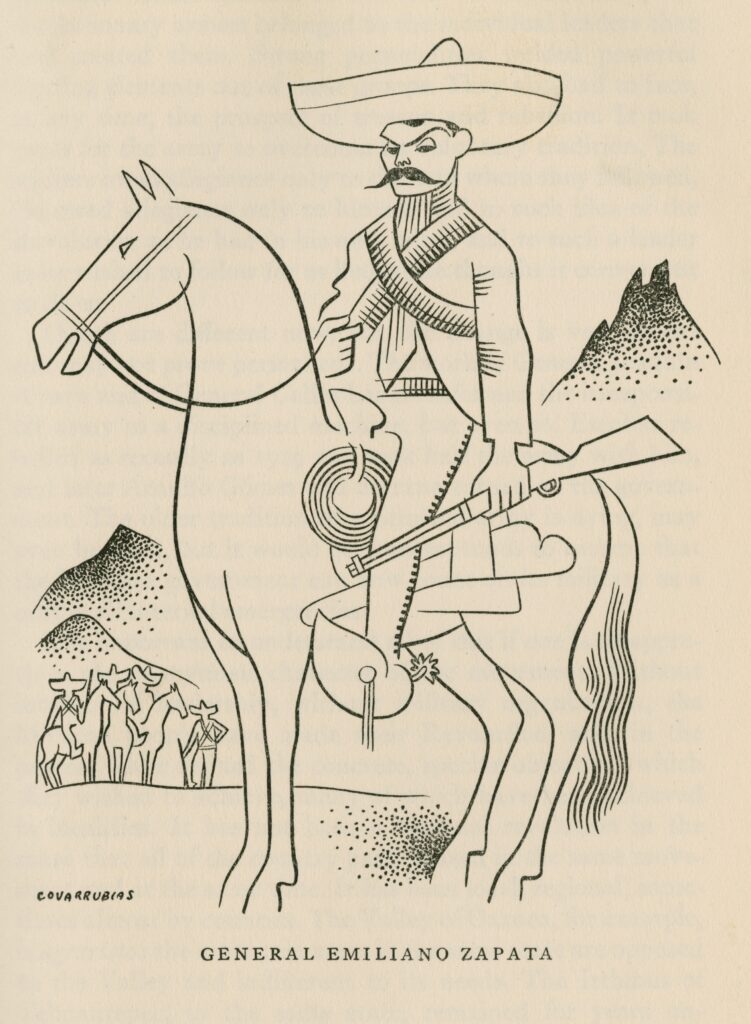

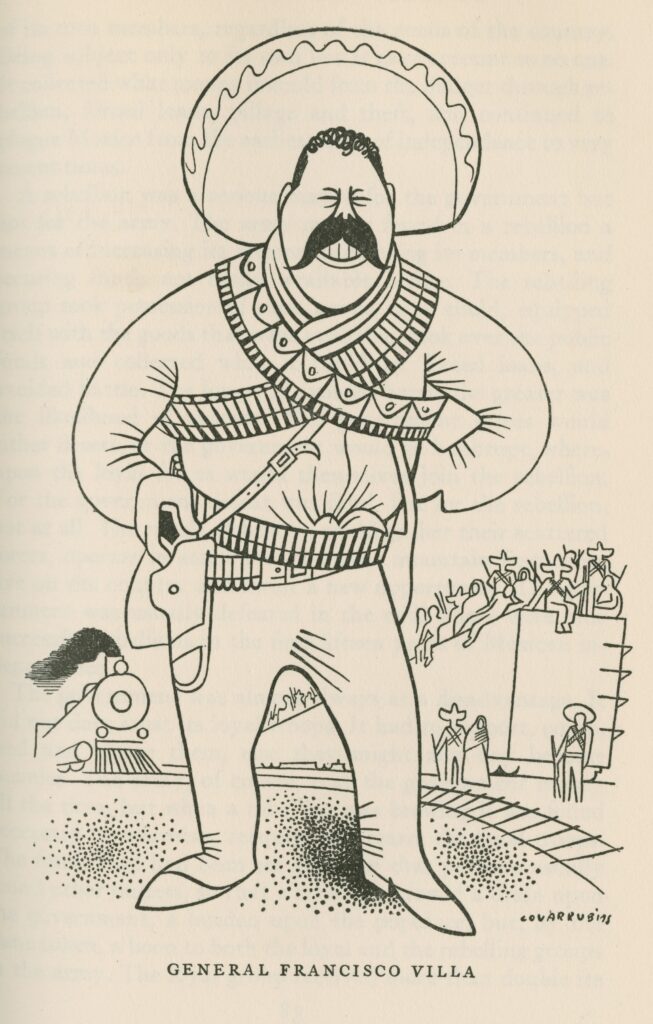

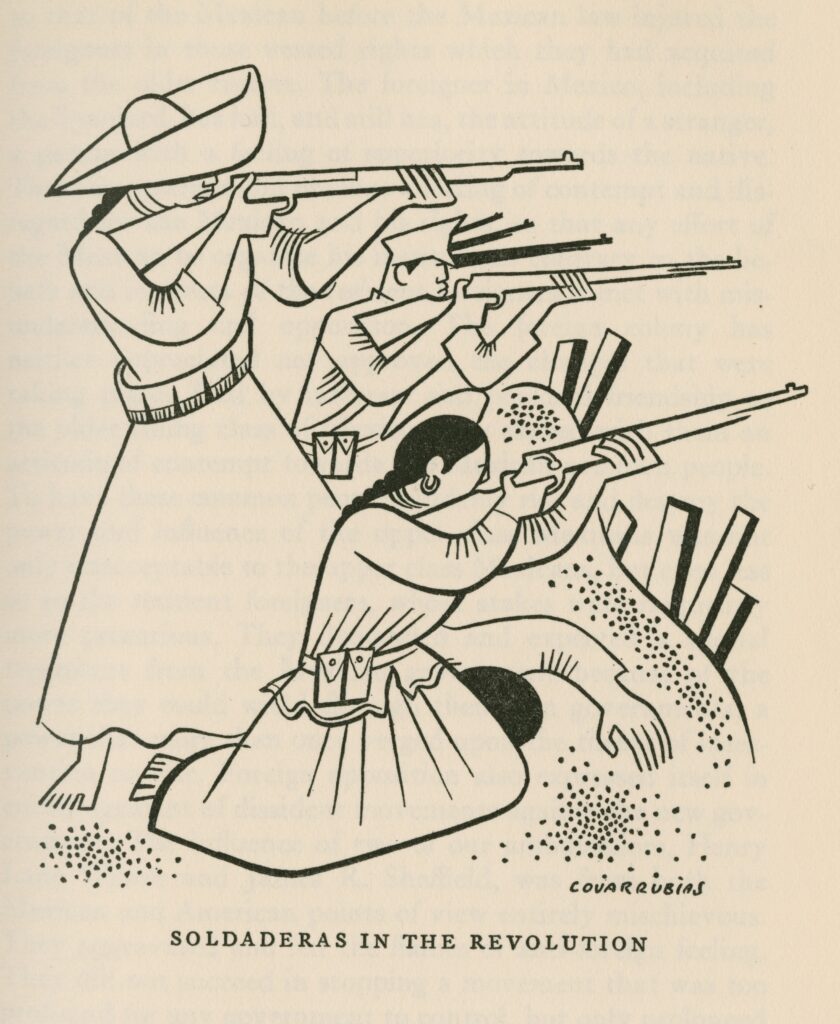

Miguel Covarrubias was a Mexican-born artist and writer who lived in New York in the 1920s and became known for the skillful caricatures that he published in magazines such as the New Yorker and Vanity Fair. Covarrubias created the drawings below to accompany American Frank Tannenbaum’s 1933 history of the Mexican Revolution, Peace by Revolution. Tannenbaum’s book was the first to interpret the revolution as a populist, agrarian, and nationalist movement by rural citizens to free themselves from the elitist Díaz regime.

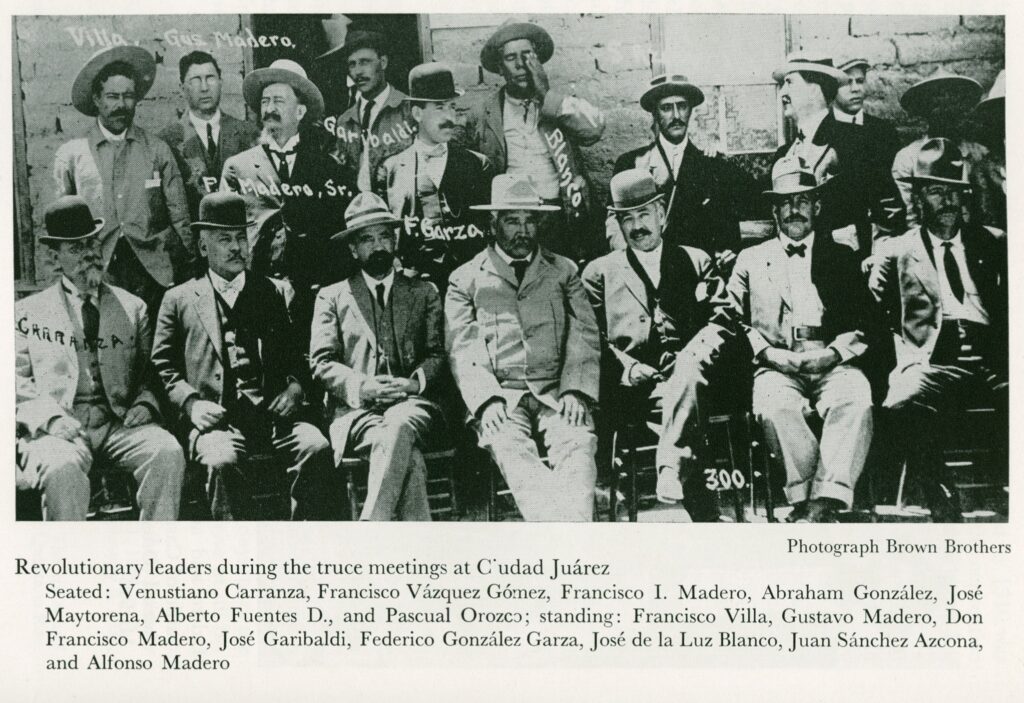

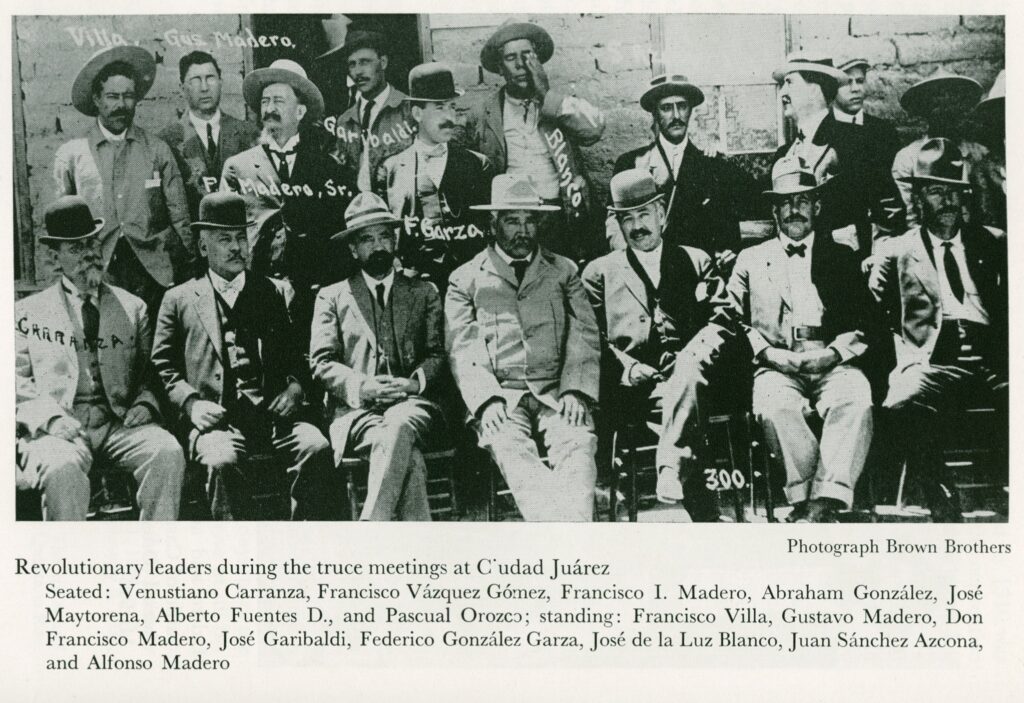

Posada’s and Covarrubias’s illustrations call attention to some of the revolutionary personalities and figures that caught the imagination of people in both Mexico and the United States. The first photograph below shows revolutionary leaders, including Venustiano Carranza, Francisco I. Madero, and Francisco (Pancho) Villa, meeting in Ciudad Juarez in May 1911. Rebel troops had just defeated General Porfirio Diaz’s federal troops to capture the city. The Treaty of Ciudad Juarez led to Diaz’s resignation at the end of the month and enabled Madero’s election as president later that year.

Covarrubias’s drawings capture two of the most mythologized and controversial leaders of the revolution: Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa. Zapata lived in the southern state of Morelos, where many people endured brutal working conditions on large sugar cane plantations controlled by hacendados, or wealthy landowners. He and his supporters suffered and also inflicted terrible violence, particularly under the military dictator Huerta, who ordered his troops to wipe out the peasant population of Morelos. Villa began life as a bandit in the northern state of Durango, but proved himself a brilliant military tactician during the revolution. Both men were popular heroes and, in 1914, famously joined forces and led their troops into Mexico City together. But neither wanted to rule the country and both came into conflict with Carranza after the Constitutionalist victory. Zapata was assassinated on Carranza’s orders in 1919. Villa was assassinated in 1923 on the orders of then-President Álvaro Obregón.

Finally, the images below feature soldaderas, a term that could refer either to women soldiers or to “camp followers,” women who travelled with troops and provided food, ammunition, and medical care. Historian Andrés Fuentes argues that federal armies under Diaz and Huerta as well as northern Constitutionalist forces relied heavily on women who accompanied the troops and provided essential support. Some of these women joined the armies voluntarily, out of ideological commitments, or for protection, or to remain close to their families. Others were conscripted or abducted into service. Female fighters participated in all of the revolutionary armies, often dressed as men, and were the subject of great fascination and sensationalist reporting in Mexico and the United States.

Questions to Consider

- Describe the men portrayed in the photograph of revolutionary leaders at Ciudad Juarez. How are they dressed? What differences do you notice in their appearances? How do they seem to relate to one another?

- Examine Posada’s engravings. How do they portray the war and, specifically, the revolutionary soldiers? How would you characterize the style of these engravings? What is their tone or mood? Do they seem to express support for one side or another in the revolution? Why do you think they were popular at the time?

- How does Covarrubias portray the leaders and fighters of the revolution for Tannenbaum’s book? Compare his illustrations to Posada’s and the Brown Brothers’ photograph.

Further Reading

Beezley, William H. “Revolution: 1910–1946.” In Mexico in World History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011. 104–119.

Fuentes, Andrés Reséndez. “Battleground Women: Soldaderas and Female Soldiers in the Mexican Revolution.” The Americas 51, No. 4 (April 1995): 525–553.

Newberry Library. Approaching the Mexican Revolution: Books, Maps, Documents. 2011.

PBS. The Storm That Swept Mexico. 2012.