Introduction

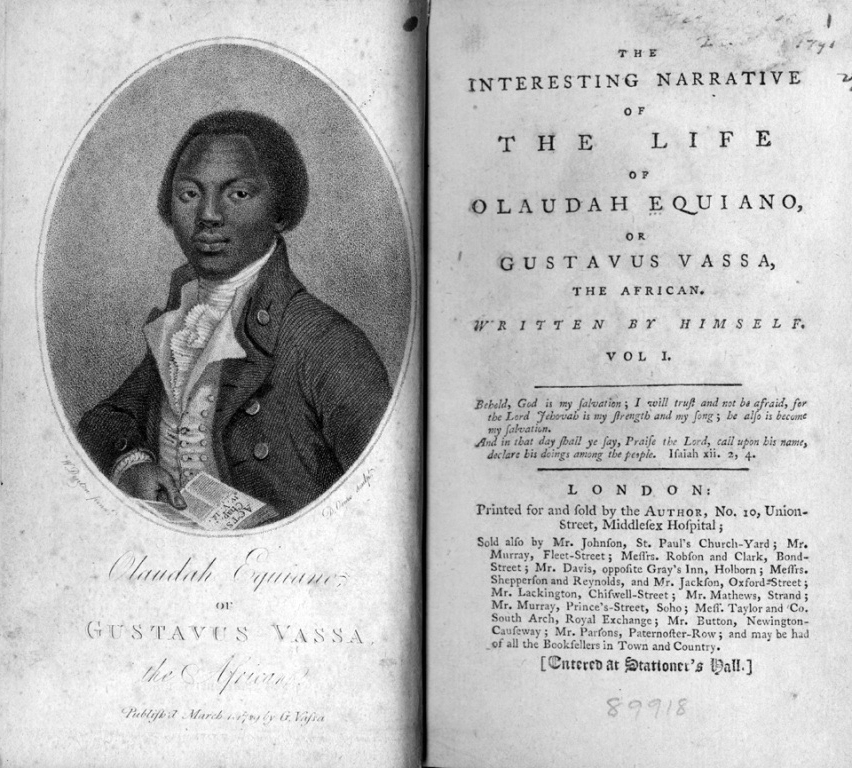

Olaudah Equiano was a British citizen and former slave who, in the 1780s, became a leader of the movement to abolish the slave trade. His autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African, was first published in London in 1789 and went through nine editions in the next five years. It contributed significantly to turning British public opinion against the slave trade. As the title suggests, Equiano was regarded as an authority on the subject of the slave trade, in large part, because he wrote that he had been born in Eboe, a province of the kingdom of Benin, in what is now southern Nigeria. He could recall his African childhood and describe the experience of being captured and sold into slavery.

In the 1790s, supporters of the slave trade sought to undermine Equiano’s credibility and the cause of abolition by questioning his claim to African identity and suggesting that he had been born in the West Indies. These arguments were dismissed as politically motivated until recently, when the scholar Vincent Carretta discovered two eighteenth-century documents that indicate that Equiano may indeed have been born in the British colony of South Carolina. Carretta’s discovery has fueled an impassioned and as yet unresolved debate among literary critics and historians about Equiano’s identity and our evaluation of different kinds of historical evidence. The literary critic George Boulukos recently suggested that we reframe this debate by studying Equiano’s narrative within the context of the eighteenth-century British debate on Africa. As Boulukos observes, debates over the slave trade often “hinged on each participant’s understanding of the state of civilization in Africa.” By exploring this debate, we can more fully appreciate the stakes of Equiano’s representation of his African origins and his contribution to the movement to end the slave trade.

Debates over the slave trade often “hinged on each participant’s understanding of the state of civilization in Africa.”

The Atlantic slave trade began in the fifteenth century, when Portuguese merchants seeking gold and spices realized there was profit in human trafficking and brought the first African slaves to Europe. Other European powers—the Dutch, French, Spanish, and British—soon joined the trade. Over the decades and centuries that followed, a triangular trade route emerged: Europeans brought manufactured goods, such as guns and textiles, to the west coast of Africa. There, they exchanged the goods for enslaved people, who were carried to the Americas to work on plantations growing crops, such as sugar cane, tobacco, and indigo. These raw materials were then shipped to Europe, where they were processed and either consumed or shipped for trade to people in Africa and the Americas.

The practice of slavery itself was not new. Historical records attest to the existence of slaves, or people who were owned by other people, on almost every continent at various times. However, before the rise of the Atlantic trade, slavery was primarily a small-scale, domestic practice. Historically, slaves occupied a familiar status within hierarchical societies in Europe, Africa, and the Americas, a status that was not necessarily very different from other forms of servitude. The Atlantic trade differed dramatically from this historic practice in two ways: it was large-scale and race-based. Scholars currently estimate that 15 million people were taken from Africa to the Americas. (About 80 percent were sent to the Caribbean and Brazil; a half million went to North America.) The trade was large scale in the sense of the numbers of people involved, the distances traveled, and, finally, in the size of the plantations on which the great majority of slaves worked. Second, between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries, slavery became a race-based, hereditary condition in the American colonies. Legal codes and social customs increasingly tied slavery to being African or the descendant of Africans, and there were few opportunities to change one’s own status or the status of one’s children.

The Atlantic slave trade continued for approximately 400 years. In the 1750s, when Equiano would have been taken aboard the slave ship, 50,000 people were being transported each year from West Africa to the Americas. In the late 1780s, when he published his autobiographical narrative, that figure was 80,000. But, by that time, in England, the movement to abolish the slave trade was starting to gain ground. A 1772 court ruling had declared slavery illegal on English soil (though not in the colonies). From 1789 on, abolitionists repeatedly urged the British Parliament to end the slave trade. They finally succeeded in 1807.

This collection of primary sources develops the historical context for the debates over Africa and the slave trade. These documents can help us understand and assess Equiano’s representation of his Afro-British identity and his intervention in these high-stakes debates.

Please consider the following questions as you review the documents

- How did eighteenth-century European and American writers portray Africans? How are these representations shaped by the writers’ own experiences and convictions?

- What arguments did eighteenth-century writers make in support of and in opposition to the slave trade? How are these arguments shaped by each writer’s understanding of African civilization?

- How does Olaudah Equiano contribute to these debates? How does he portray his own experiences of slavery and freedom? How does he define his identity as African, British, and Christian?

European Images of Africans

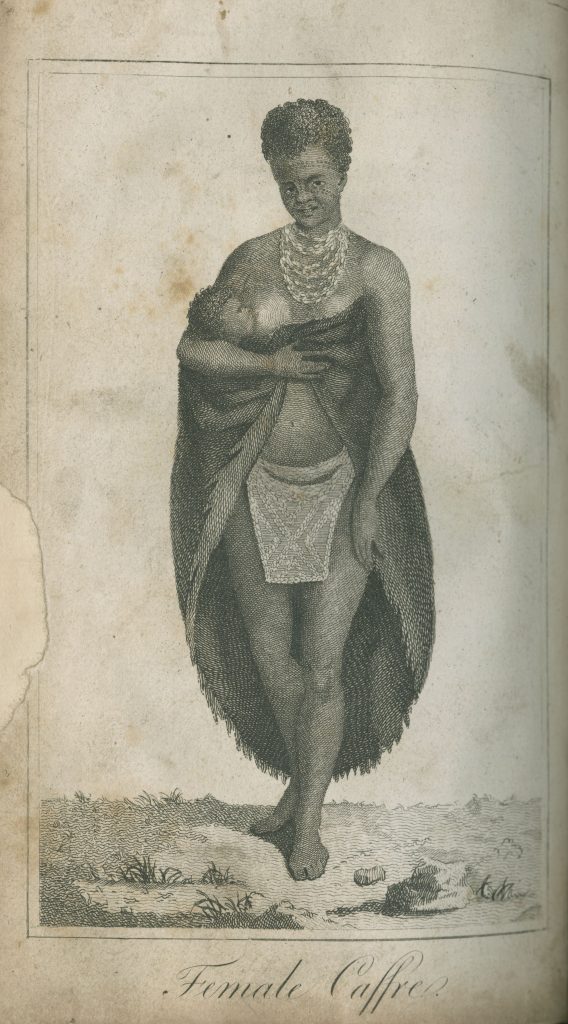

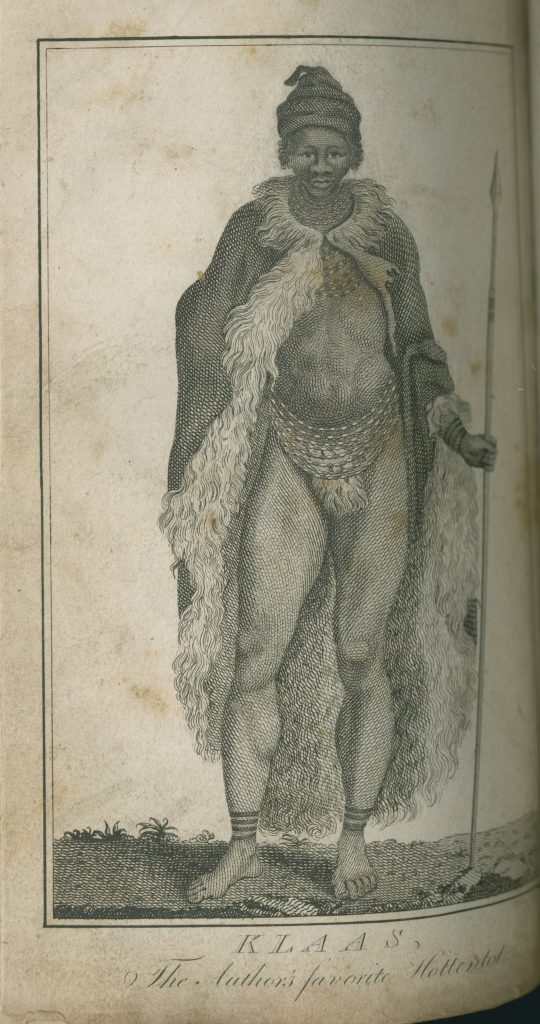

Francois Le Vaillant was a French explorer, naturalist, and writer who traveled through southern Africa in the 1780s. His Travels from the Cape of Good-Hope was published in 1790 in both French and English. The book describes his journey and the people he encountered in vivid, accessible prose, accompanied by beautiful illustrations. It was an immediate, popular success and became one of the most influential eighteenth-century sources on Africa, though scholars later questioned the accuracy of Le Vaillant’s account of his journey as well as his contributions to natural science.

Throughout the book, Le Vaillant refutes the claims of previous European explorers that Africans engaged in human sacrifice and practiced cannibalism. In contrast, he insists that the Africans he met were more virtuous the more isolated they were: “In every part, where the natives live entirely unconnected with the whites, their manners are mild and amiable; on the contrary, an acquaintance with the Europeans, alters and corrupts their natural character, which amazingly degenerates.” The above plates were based on drawings that Le Vaillant created during his journey. The first portrays Klaas, a loyal servant, whom Le Vaillant describes as “my equal, my brother, the confidant of my hopes and fears.” Le Vaillant identifies him as a member of the Hottentot (now known as Khoikhoi) tribe. The second portrays a woman from the region then known as Caffraria.

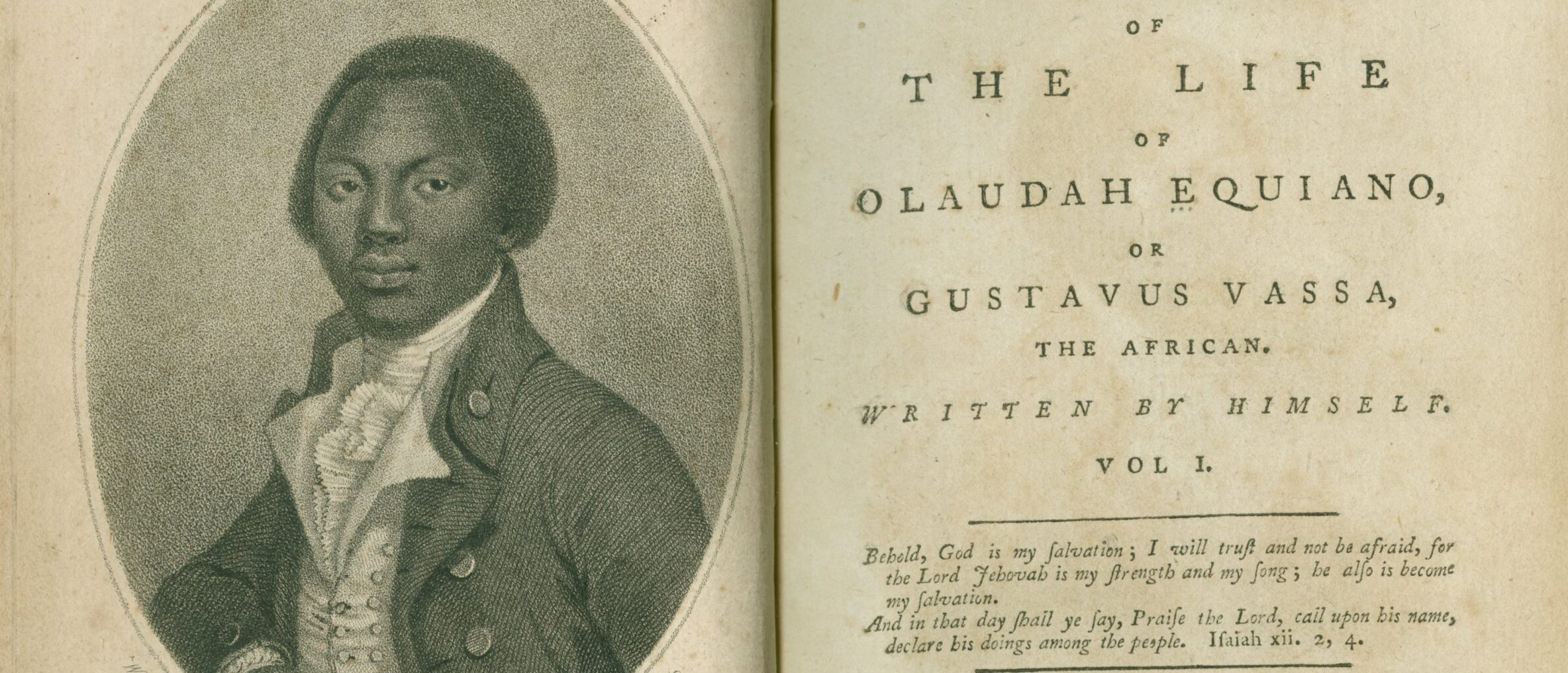

The third document in this section is a reproduction of the frontispiece and title page published with Olaudah Equiano’s Interesting Narrative in 1789. In the narrative, Equiano describes his birth and childhood in the 1740s among the Ibo people in the kingdom of Benin (now southern Nigeria). Equiano was captured and sold into slavery at around the age of 11, he believed. He purchased his freedom from his master in 1766 and became a British citizen.

Questions to Consider

- Describe Le Vaillant’s illustrations of Klaas and the woman from Caffraria. How are they posed? What kind of clothing do they wear? What do the illustrations convey about African cultures and customs?

- How do these illustrations support Le Vaillant’s description of Africans as “mild and amiable” until “corrupted” by Europeans? Do you think that Le Vaillant idealizes Africans?

- Examine the frontispiece of Equiano’s narrative. What is Equiano wearing in this portrait? What is he holding? What cultural affiliations does the portrait convey?

- Examine the title page of Equiano’s narrative. What information does the full title convey about the author and his life? Why do you think the title includes both his Ibo name, Olaudah Equiano, and the name he was given as a slave and which he more commonly used, Gustavus Vassa?

Conducting the African Slave Trade

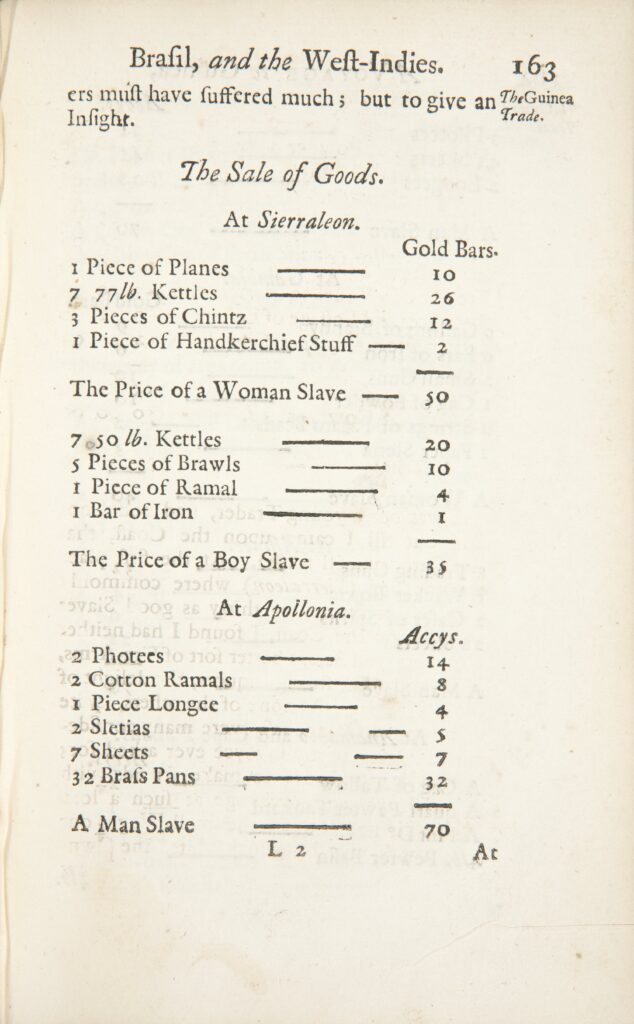

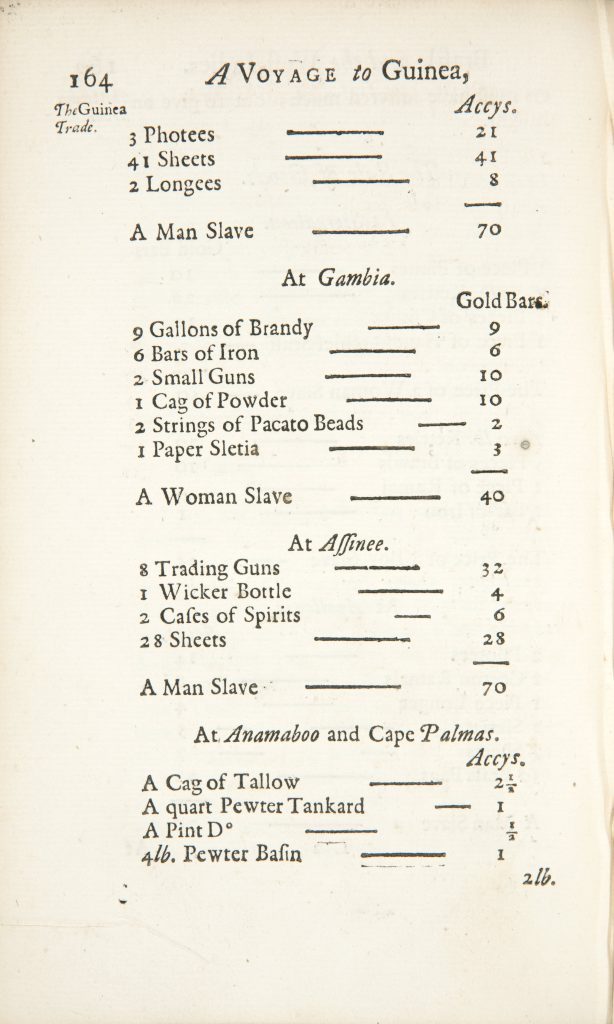

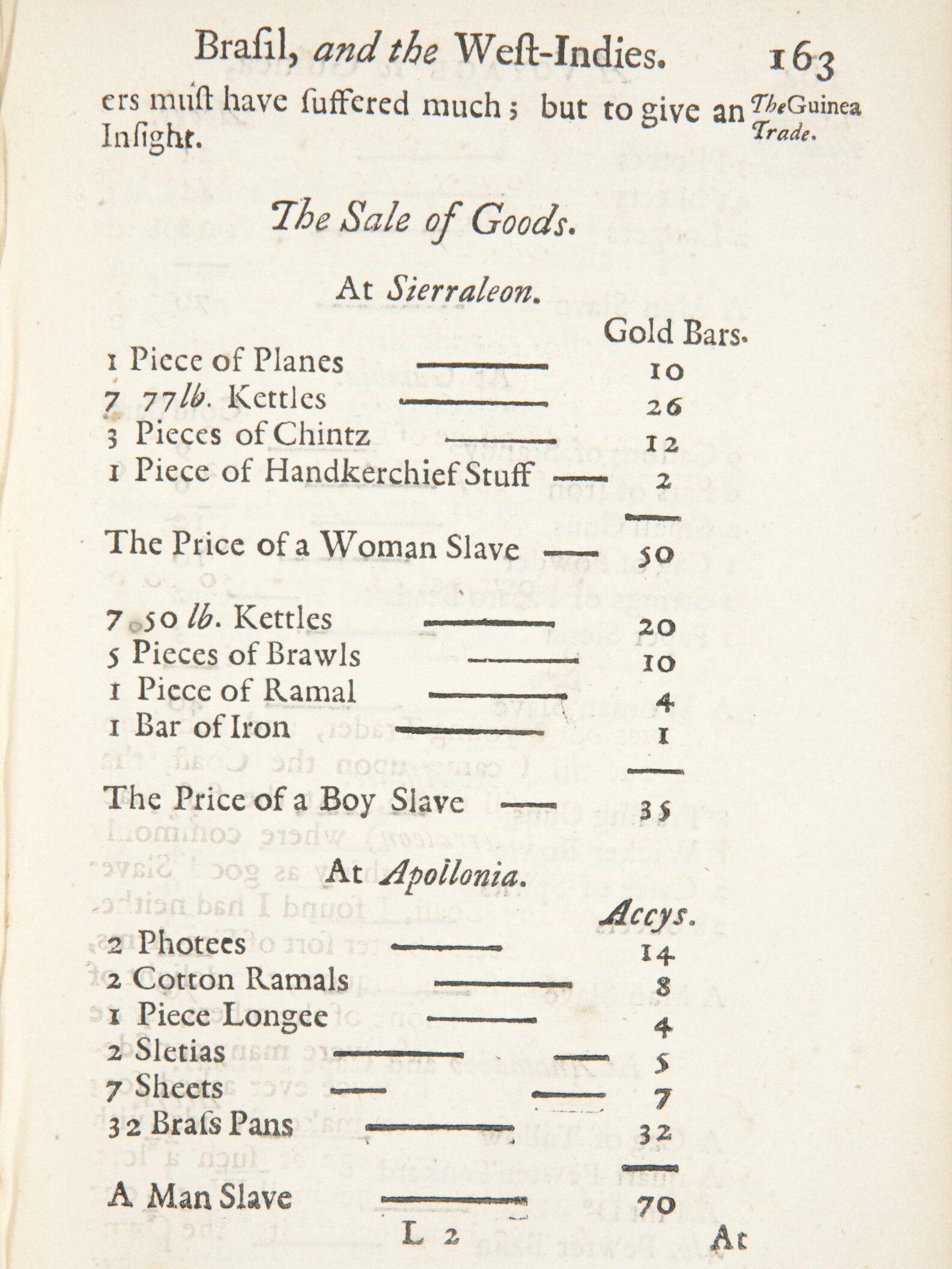

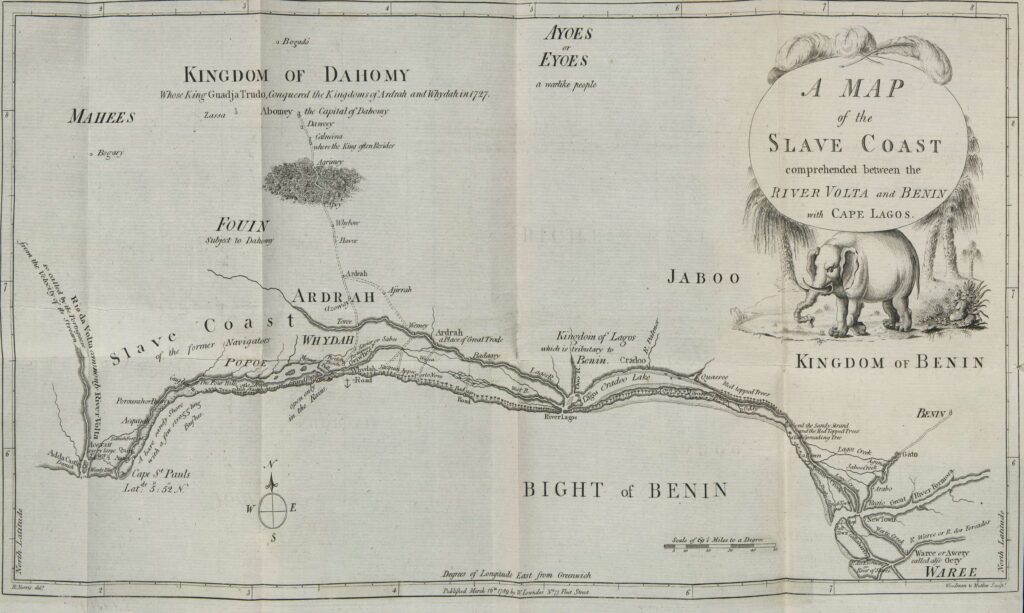

The documents in this section offer insight into how the English conducted their part of the African slave trade. Robert Norris was a slave trader who operated in the West African kingdom of Dahomey. He included this map of the West African coast in his pro-slavery political history of the kingdom, Memoirs of the Reign of Bossa Ahádee. The source of “The Sale of Goods” is John Atkins, a surgeon in the British navy. Atkins sailed to the west coast of Africa in 1721 and, the following decade, published an account of the journey in which he reproduced this 1720 invoice of goods traded for individual slaves. (Please note: photees and ramal are English manufactured cotton goods. Longees are silken handkerchiefs made in India.)

Selection: John Atkins, “The Sale of Goods” in A Voyage to Guinea, Brasil and the West Indies, 163-164 (1735)

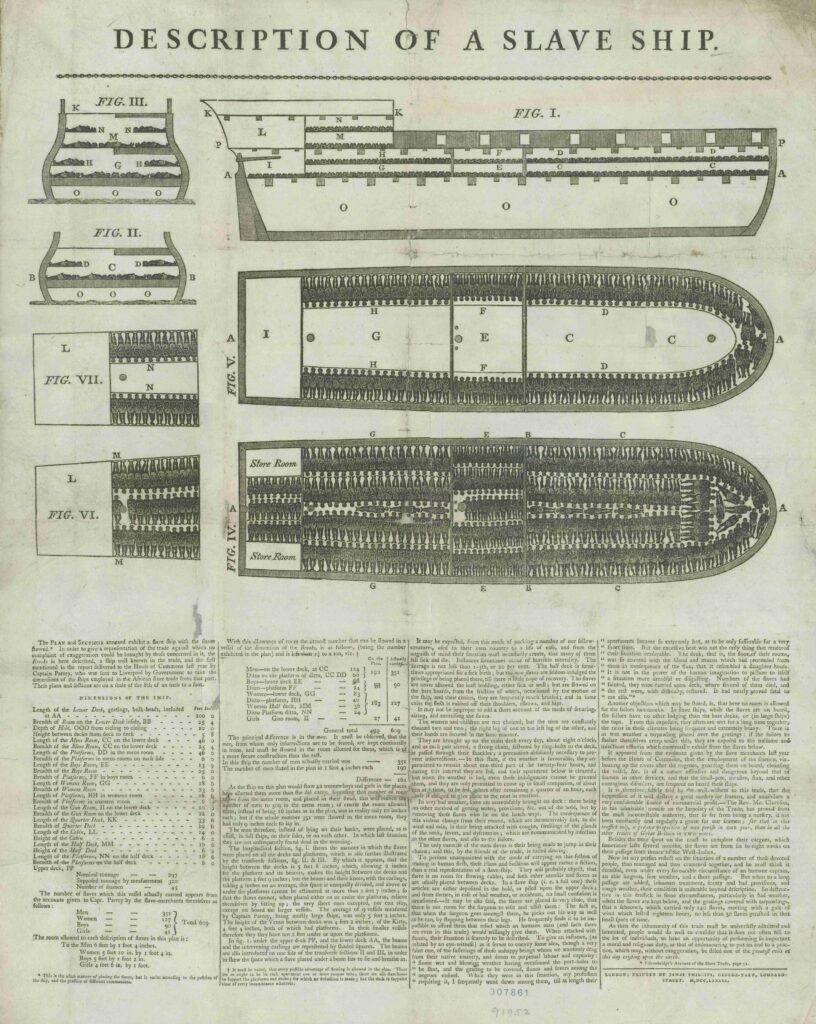

Description of a Slave Ship is a famous antislavery broadside published in London in 1789. The diagram illustrates the layout of a slave ship, while the text that follows describes the physical dimensions, the number of people carried, and the conditions on board.

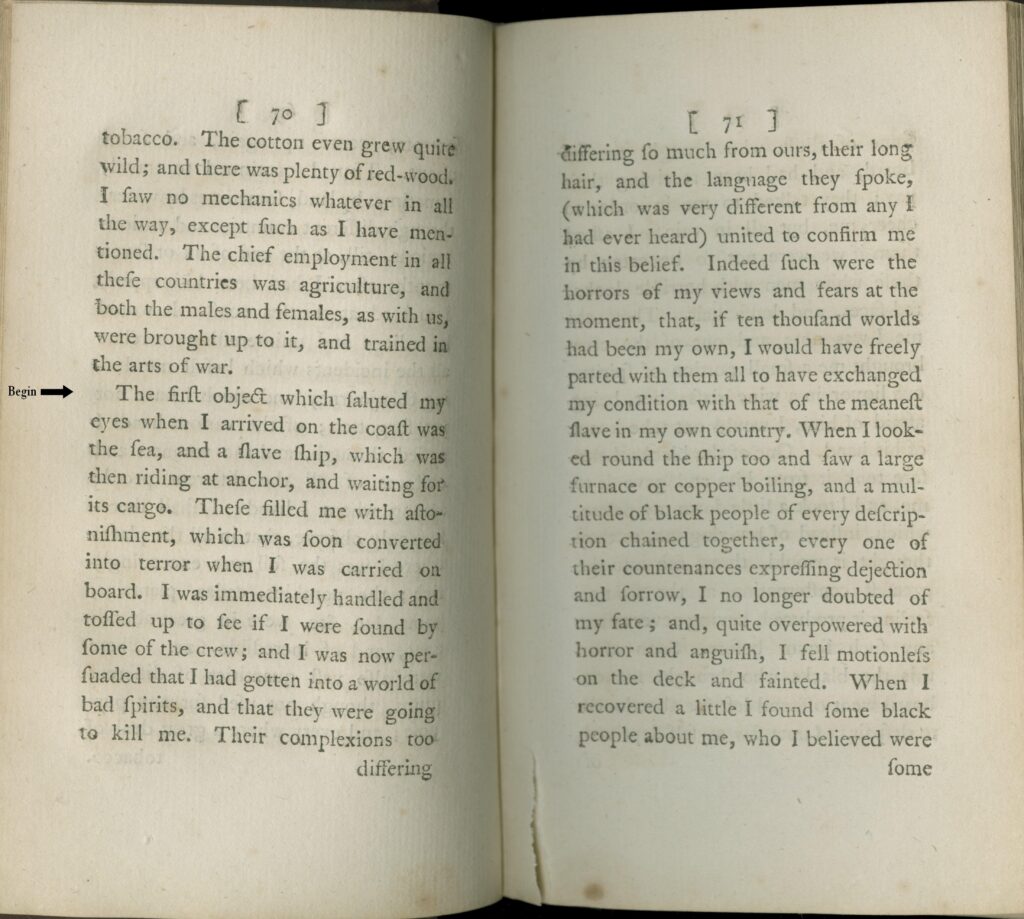

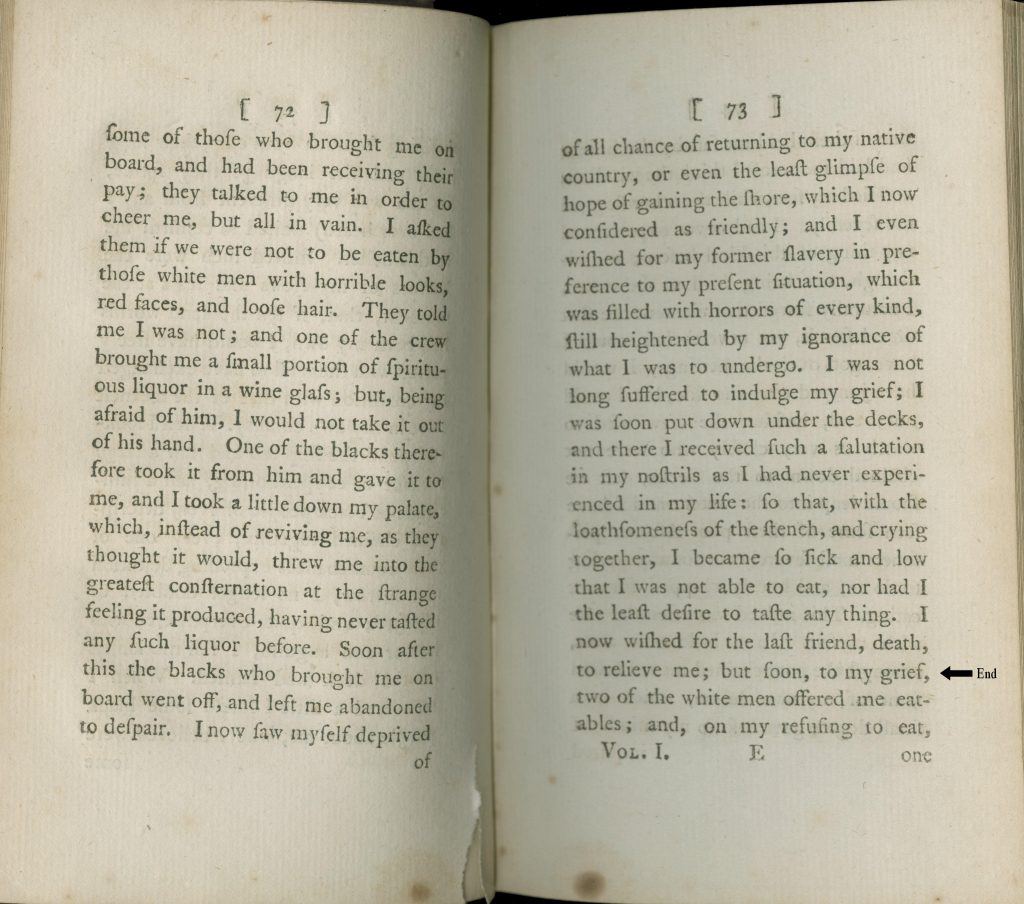

The final document in this section is Olaudah Equiano’s description of being carried on board a slave ship at the age of 11 or 12. At this point in his narrative, he has already spent many months as a slave exchanged between different African tribes.

Selection: Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa, the African, 70-73 (1789).

Questions to Consider

- What information does Norris’ map convey about the West African coast? What kind of information is not included? What does the map suggest about Norris’ knowledge of and interests in West Africa?

- How does the cartouche in the upper right corner contribute to the map? In what ways does it shape the map’s representation of Africa?

- Examine the “Sale of Goods” from Atkins’ A Voyage to Guinea. What kinds of goods did Europeans trade to African people along the coast in exchange for slaves? What other information about the conduct of the slave trade does this document convey?

- Examine the diagram and text from the broadside, Description of a Slave Ship. How do the diagram and the text work together? What do you learn about the slave trade from this document? Why do you think abolitionists believed that it would help their cause to publish this kind of information?

- What are Equiano’s feelings when he is carried on board the slave ship? How does he perceive the Englishmen who work on the ship? How does he relate to the Africans on board?

- Consider that Equiano wrote this scene as an adult and an advocate of ending the slave trade. How might his representation of this experience contribute to the abolitionist cause?

Defending the Slave Trade

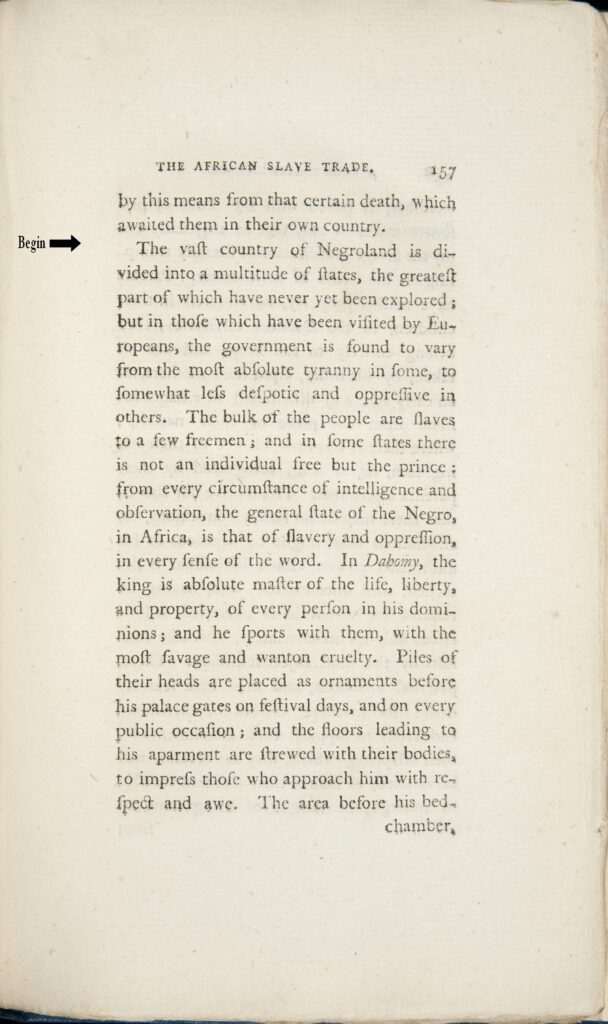

Both William Snelgrave and Robert Norris were English slave traders who operated in Dahomey, a powerful West African kingdom that had been conquering neighboring territories since the late seventeenth century. Snelgrave and Norris both alleged that the Dahomey practiced human sacrifice and cannibalism. Both men also defended the slave trade. Snelgrave’s book was especially influential and provided material for pro-slavery arguments throughout the eighteenth century.

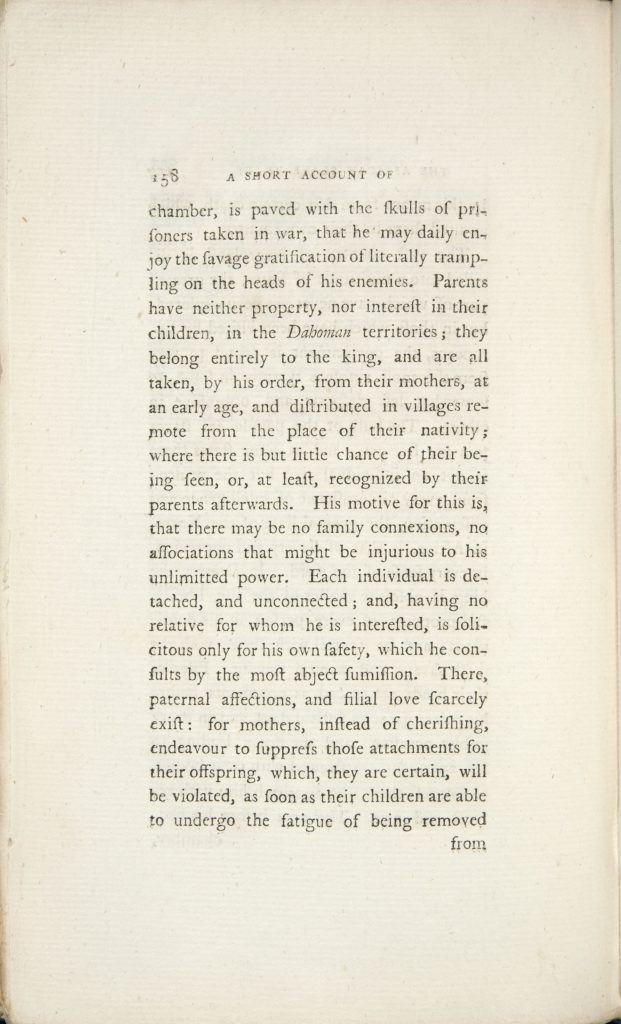

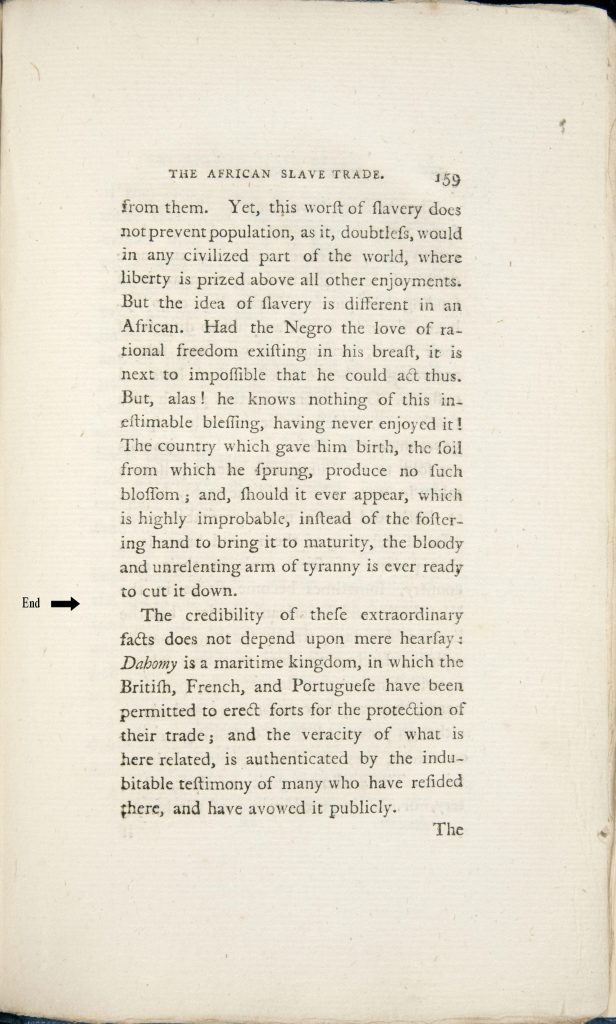

Selection: Robert Norris, Memoirs of the reign of Bossa Ahádee, King of Dahomy, an Inland Country of Guiney, 157-159 (1789).

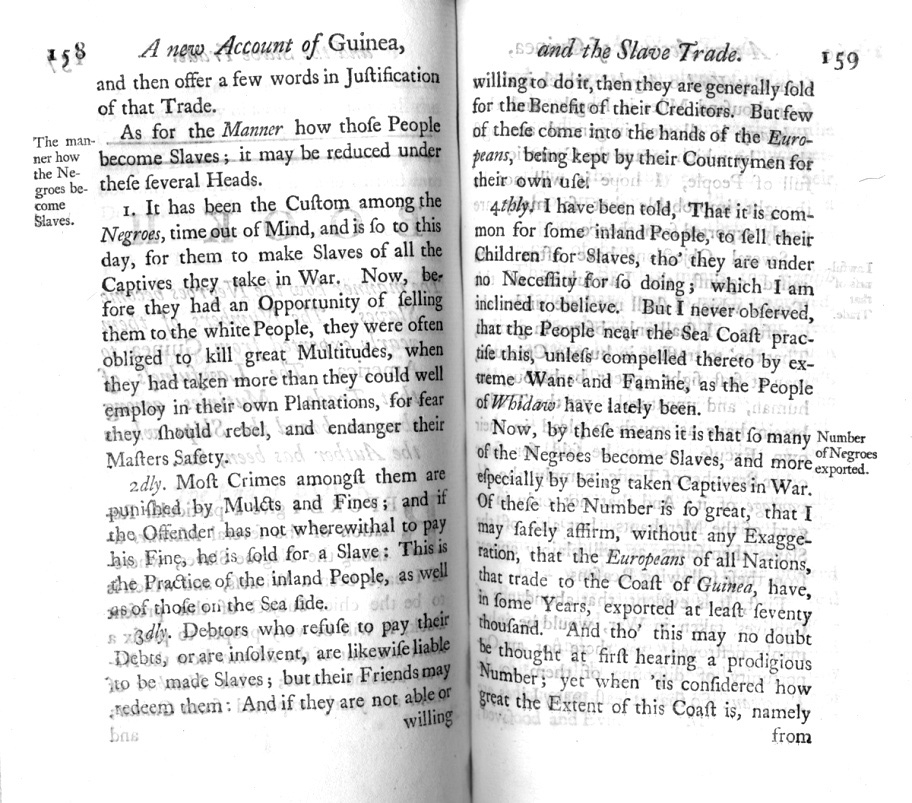

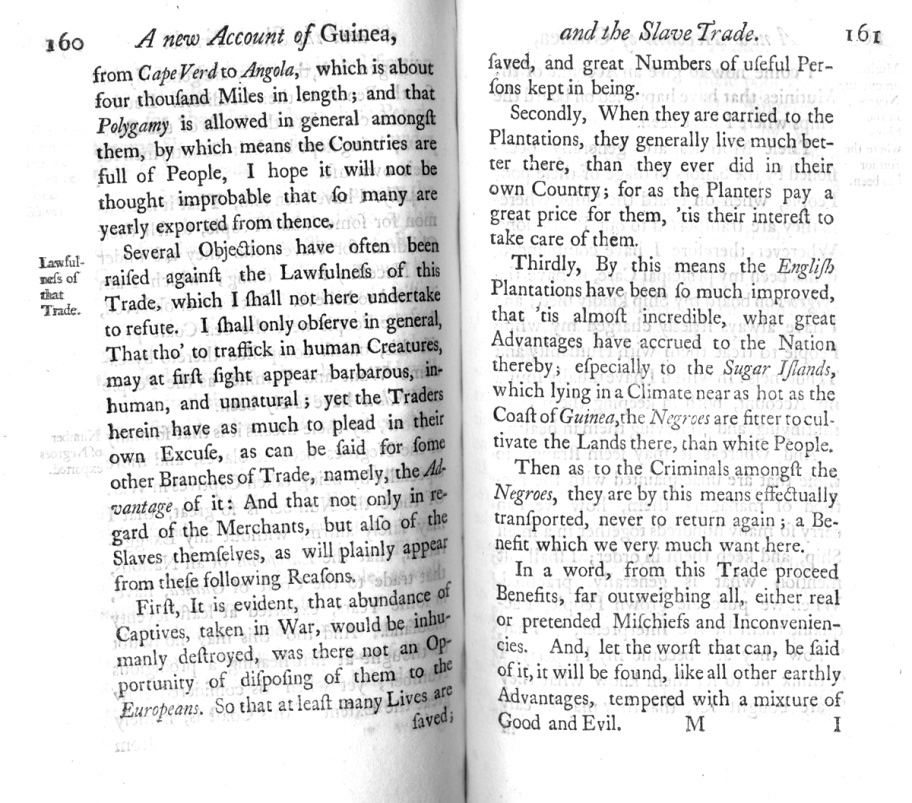

Selection: William Snelgrave, A New Account of Some Parts of Guinea, and the Slave-Trade, 158-161 (1734).

Questions to Consider

- How do people become slaves, according to Snelgrave’s account?

- On what grounds does Snelgrave defend the slave trade? What does he claim are its benefits?

- How does Norris portray political and familial relationships among the Dahomey? How might his description of Dahomey society implicitly support the slave trade and the institution of slavery? Why do you think an English slave trader would want to write a political history of a West African kingdom?

Opposing the Slave Trade

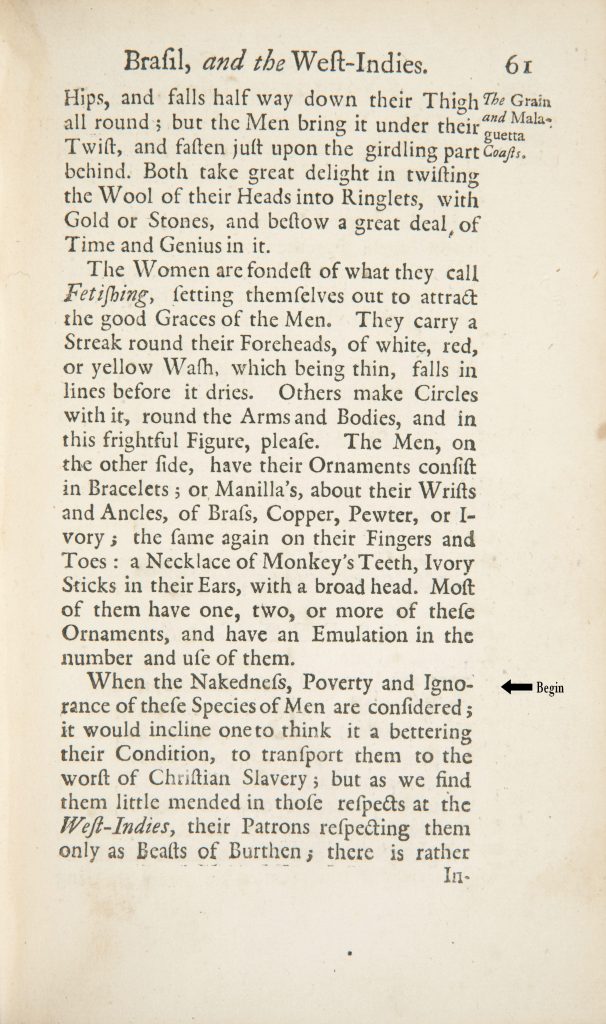

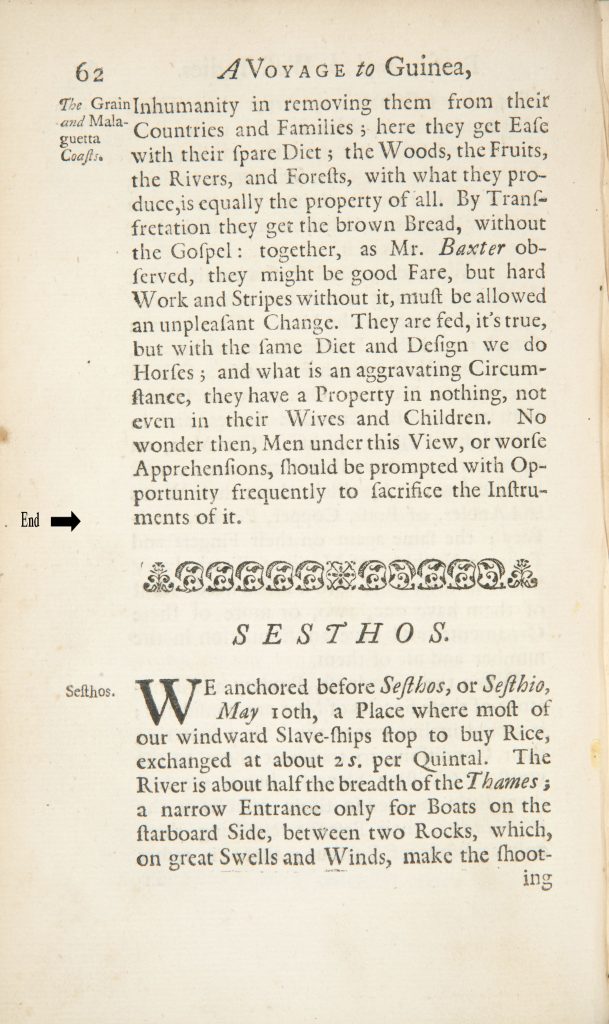

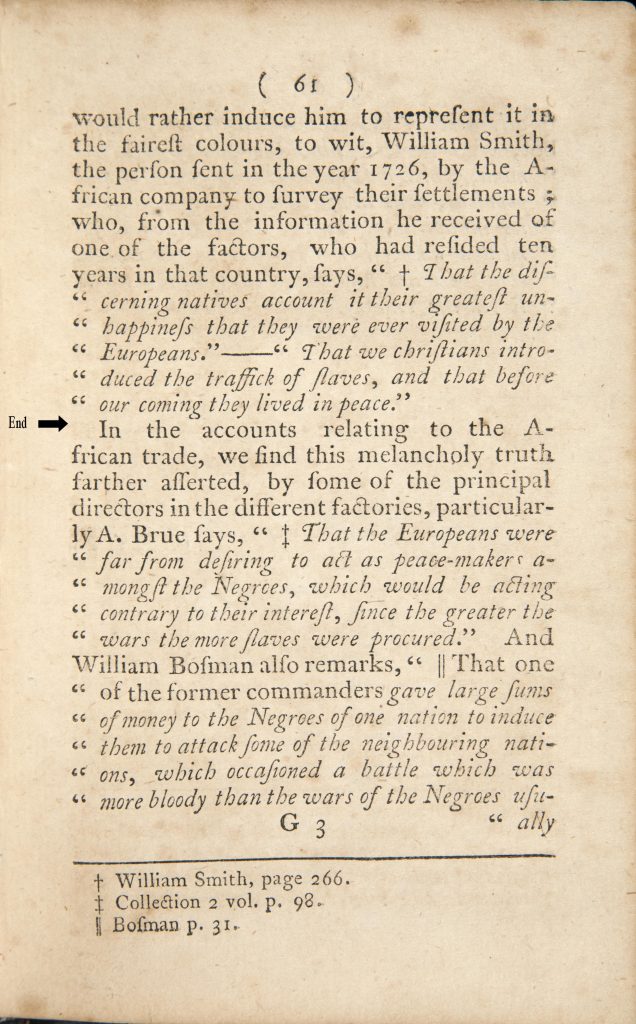

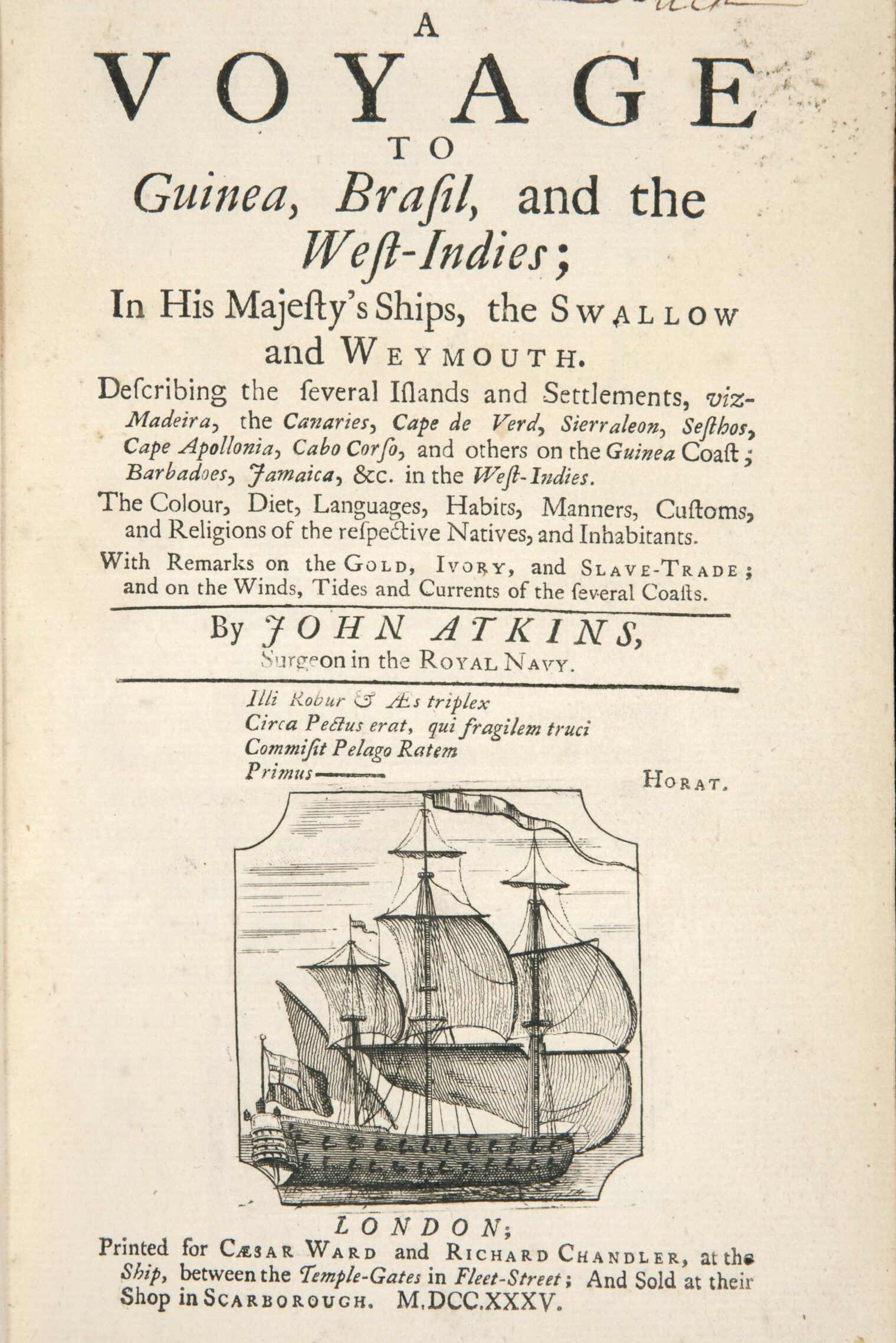

John Atkins was a surgeon in the British navy who participated in an expedition to suppress piracy on the West African coast in 1721 and later published this account of the voyage. Atkins criticizes the slave trade, but also offers practical advice on successfully conducting it.

Selection: John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea, Brasil and the West Indies, title page, 61-62 (1735)

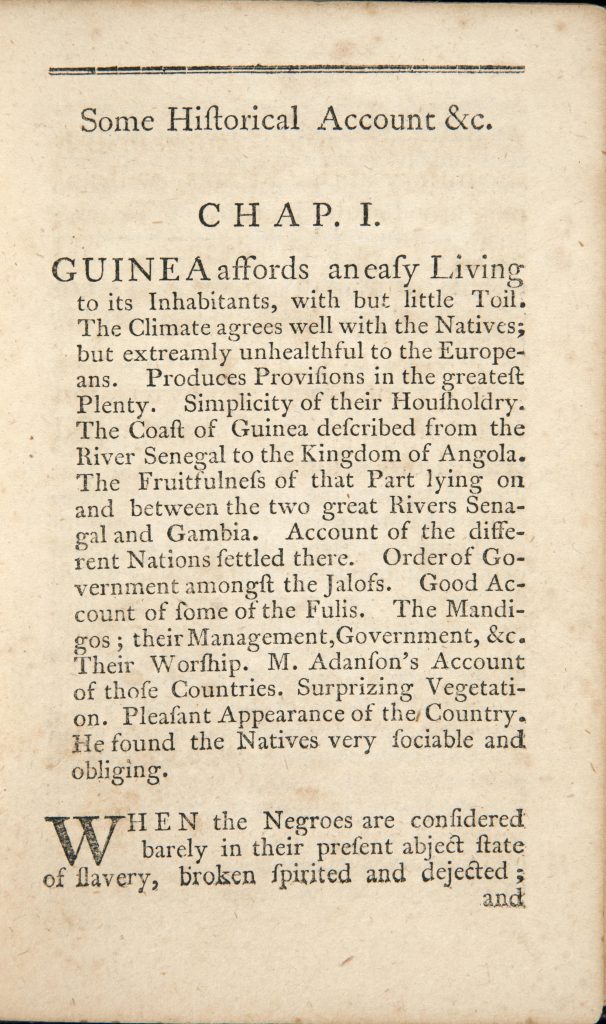

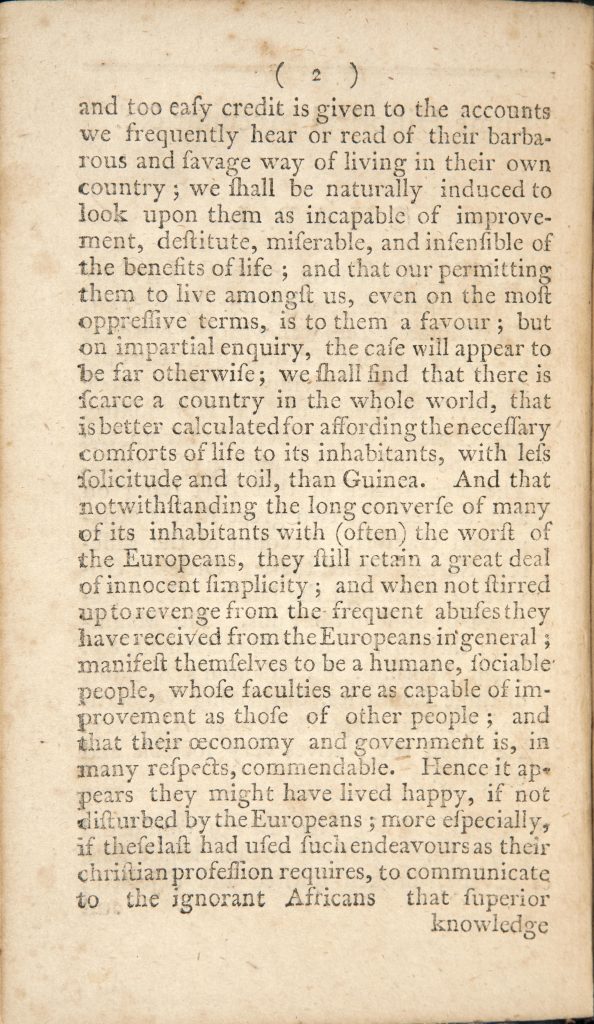

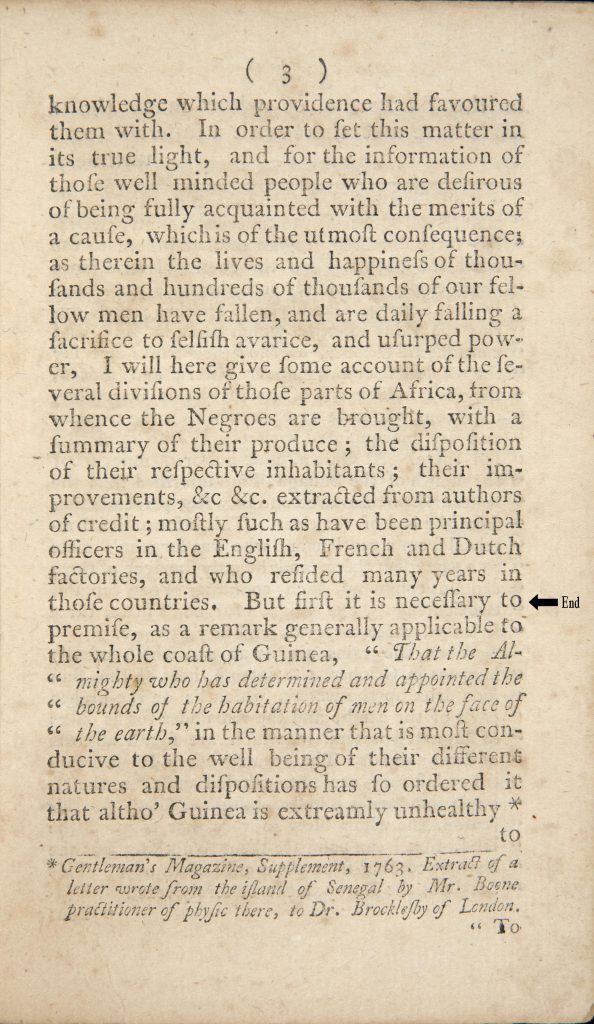

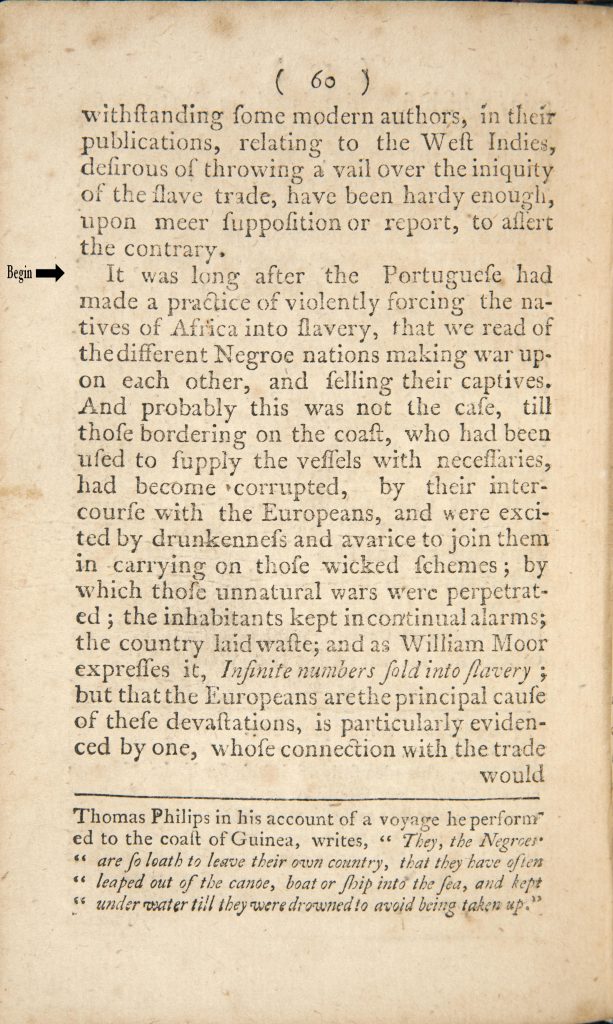

The second author in this section is Anthony Benezet, a Philadelphia Quaker and prominent abolitionist. Benezet’s Some Historical Account of Guinea became a crucial source within the antislavery movement. As the scholar George Boulukos notes, Benezet devotes much of this text to describing African civilization. He had not traveled to Africa himself, but quotes heavily from eighteenth-century travel narratives (including even William Snelgrave’s, excerpted in the previous section).

Selection: Anthony Benezet, Some Historical Account of Guinea, Its Situation, its Produce and the General Disposition of its Inhabitants, title page, 1-3, 60-61 (1771).

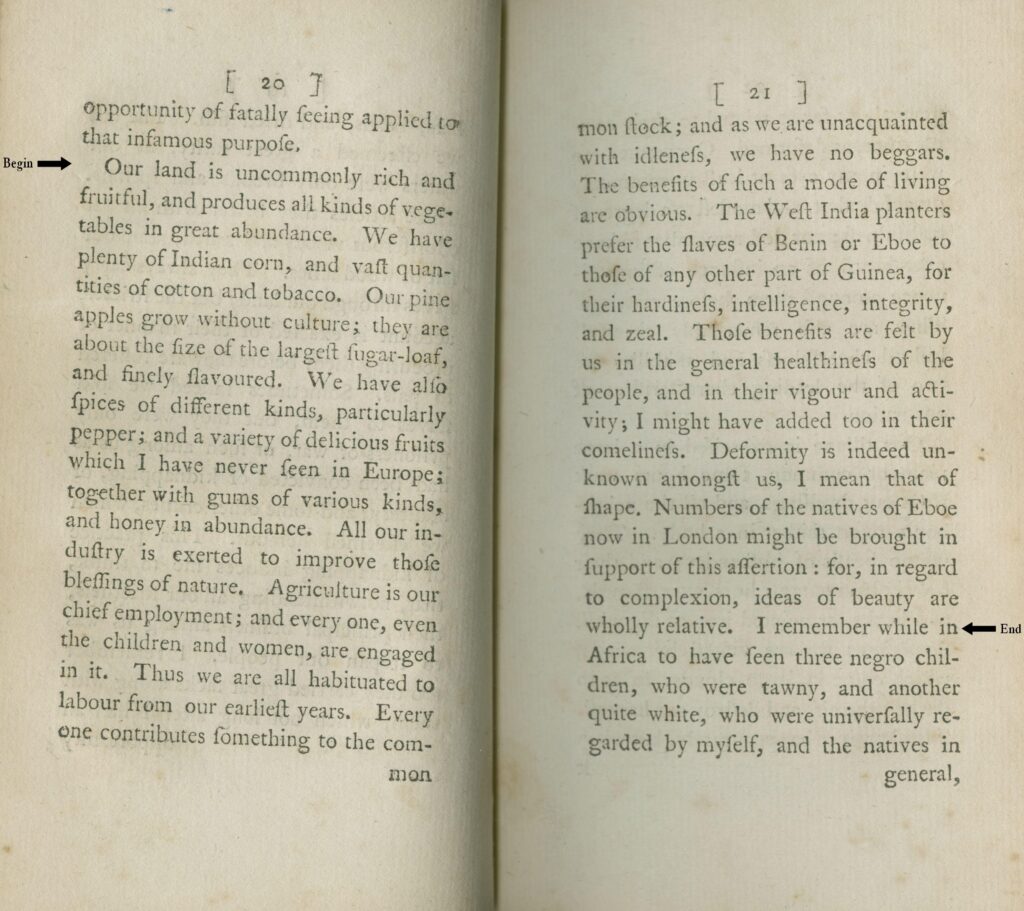

The final document is Olaudah Equiano’s own description of the land of Eboe (now southern Nigeria) where he situates his childhood.

Questions to Consider

- How does Atkins portray African civilization? On what grounds does he condemn the slave trade and slavery?

- Why does Benezet set out, at the very beginning of his book, to refute negative perceptions of Africa? Why would representations of Africa be so central to an antislavery text?

- Who instigated war and the practice of slavery in Africa, according to Benezet? Why might his argument be important to the antislavery cause?

- How does Equiano portray the social organization and natural environment of Eboe? In what ways does his description of the people and land counter Snelgrave’s and Norris’ accounts of West Africa? In what ways does he tailor his discussion for English readers?

- Compare the representations of Africans by both pro–slave-trade and anti–slave-trade writers in this document collection. Do you see consistent patterns within each side’s descriptions of Africans? What differences and similarities do you notice between the two sides? Do you find either side’s representations of Africans reliable? On what grounds?

European Depictions of Africans

In contrast to other portrayals by European travel writers and naturalists, François Le Vaillant depicted Africans as virtuous and contact with Europeans as a corrupting force on their naturally amiable character.

The Slave Trade

These documents offer insights into how the slave trade was conducted and its conditions for the enslaved.

Debates on the Slave Trade

These writings, authored by two English slave traders, a surgeon for the British navy, and a Philadelphia Quaker, capture eighteenth-century debates on the slave trade, with each making arguments either in defense of or in opposition to slavery.

Equiano and his Narrative

Equiano’s autobiographical book, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African, published in 1789, traced his experiences of being captured and sold into slavery and helped advance the cause of abolitionism in Britain.

Further Reading

Boulukos, George E. “Olaudah Equiano and the Eighteenth-Century Debate on Africa.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 40, no. 2 (2007): 241–255.

Carretta, Vincent. Introduction. In Unchained Voices: An Anthology of Black Authors in the English-Speaking World of the 18th Century. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1996. 1–16.

Carretta, Vincent. “Questioning the Identity of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African.” In The Global Eighteenth Century. Edited by Felicity A. Nussbaum. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003. 226–235.

Carretta, Vincent. “Response to Paul Lovejoy’s ‘Autobiography and Memory: Gustavus Vassa, alias Olaudah Equiano, the African.’” Slavery and Abolition 28, no. 1 (April 2007): 115–119.

Equiano, Olaudah. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African. Edited by Werner Sollors. New York: Norton, 2001.

Law, Robin. “The Slave-Trader as Historian: Robert Norris and the History of Dahomey.” History in Africa 16 (1989): 219–235. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3171786.

Lovejoy, Paul E. “Autobiography and Memory: Gustavus Vassa, alias Olaudah Equiano, the African.” Slavery and Abolition 27, no. 3 (December 2006): 96–105.

Lovejoy, Paul E. “Issues of Motivation—Vassa/Equiano and Carretta’s Critique of the Evidence.” Slavery and Abolition 28, no. 1 (April 2007): 121–125.

Matrix and the African Studies Center, Michigan State University. “The Atlantic Slave Trade.” In Exploring Africa. http://exploringafrica.matrix.msu.edu/students/curriculum/m7b/activity1.php.

Olsen, Penny. “The Independent Ornithologist.” The National Library Magazine 1, no. 1 (March 2009): 18–20. http://www.nla.gov.au/pub/nlanews/2009/mar09/the-independent-ornithologist.pdf.