Introduction

What is the matter with Shakespeare’s families? Why do so many of his tragic plays involve injuries and betrayals committed between parents and children, husbands and wives, sisters and brothers? How do these plays respond to changes in the understanding and organization of the family during the English Renaissance?

Historians such as Lawrence Stone have identified the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries as a crucial period in the history of the family in Britain. At the beginning of this period, most marriages were arranged, not by the two people getting married, but by their parents and other relatives. The primary purpose of marriage, especially among the upper class, was to transfer property and forge alliances between extended family networks, or kin groups. A marriage might provide a way of combining adjacent estates or of concluding a peace treaty. In fact, people used the term family to refer to all of the people living in one house, under one head, including servants as well as parents, children, and other “blood” relations. Gradually, during these centuries, these understandings of marriage and family changed. The conjugal (or marrying) couple became more important and, increasingly, people came to think of the family as centered on parents and their children—what we refer to as the nuclear family.

In sixteenth century England, most marriages were arranged, not by the two people getting married, but by their parents and other relatives. . . Over the next two centuries, these understandings of marriage and family would change.

Historians attribute these changes, in part, to the Protestant Reformation. Protestant religious leaders rejected the Catholic Church’s policy that clergy could not marry. Instead, Protestants developed the idea of “holy matrimony” and wrote extensively about the spiritual and political as well as personal significance of marriage. As literary critic Mary Beth Rose explains, Protestant writers “equate[d] spiritual, public, and private realms by analogizing the husband to God and the king, the wife to the church and the kingdom.” These Protestant writings provided religious support for changes in family structure that were also due to wider socioeconomic changes, such as population growth, urbanization, increasing mobility, and greater trade.

While historians might look to this period for the emergence of the modern family, it is important to note some distinctly pre-modern legal and social conventions which lasted into the nineteenth century. Under the English system of coverture, a woman’s identity was covered by her husband’s when she married. A married couple was regarded by the law as a single entity and that entity followed the will of the husband. Mothers had no legal rights over the guardianship of their children and any property that a woman possessed at the time of marriage came under the husband’s control. Numerous married women may have found ways to work around the law and to exercise legal and economic power, but these conventions had a significant impact on women’s status, rights, and opportunities.

The social and cultural transformation of the family took place gradually and unevenly. Works by Shakespeare and other Renaissance writers rarely provide a straightforward expression of either older or newer beliefs about the family and marriage. What their texts can show us, instead, are the conflicts and contradictions that emerged as writers examined family relationships during this period. The following collection of documents provides some historical context for Shakespeare’s plays. The documents include advice manuals and crime literature as well as Biblical family trees, all of which shed light on the many ways that Renaissance people thought about and participated in the family.

Please consider the following questions as you review the documents

- How did Renaissance writers define the family? Which relationships seem to them the most important? What makes these relationships important? To what extent do writers seem concerned with emotions like love or happiness and to what extent do they seem more interested in ideas of duty, property, lineage, or Christian faith?

- What are the obligations of family members to one another, according to these documents? How do the writers expect husbands, wives, parents, children, and siblings to behave toward one another? What differences or contradictions appear between these writers?

- What are the perceived threats to the family? How should these threats be addressed?

- What does writing on the family tell us about the history of gender, or the expectations and experiences of women and men during the English Renaissance?

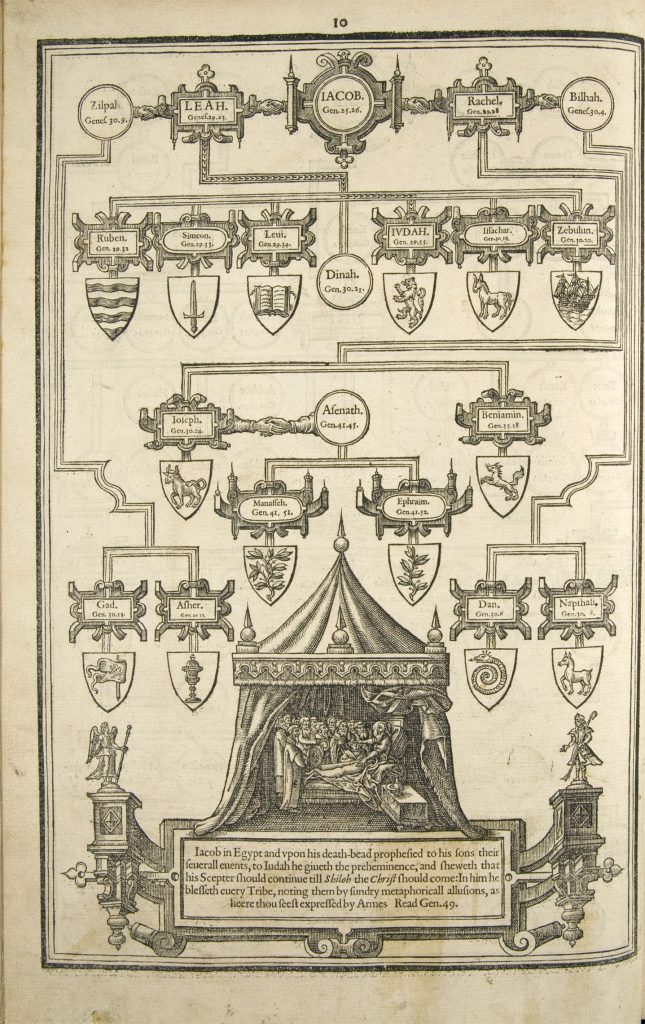

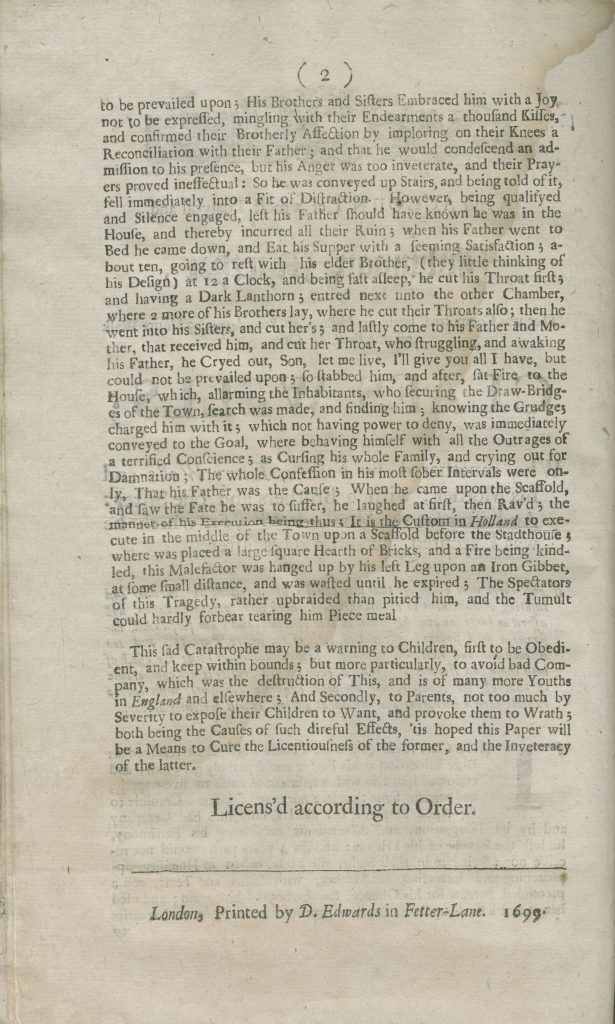

Biblical Genealogies

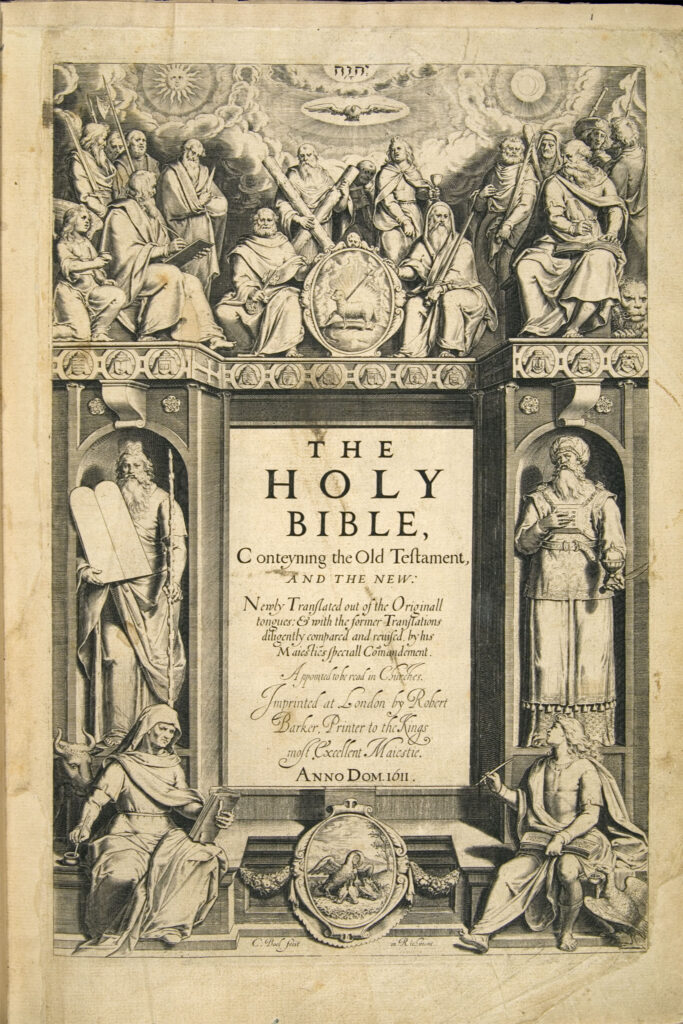

The Protestant Reformation fueled efforts to translate the Bible into modern, vernacular (or spoken), European languages from its original Hebrew, ancient Greek, and Latin. Only the clergy and a small elite knew how to read ancient languages. The lack of modern translations reinforced the Catholic Church’s hierarchical structure, which Reformation leaders opposed. Protestants believed it was important for laypeople (or church members)—including women—to be able to read God’s word themselves. In 1604 King James directed a group of nearly 50 scholars to undertake a new translation of the Bible into English. It was not the first English translation of the Bible—two others had appeared in the previous century—but it was the first designed specifically to conform to the teachings of the Church of England. Their translation, eventually known as the King James Bible, was published in 1611. By the next century, it had become the standard translation used in Anglican and Protestant churches. The edition presented here opens with 34 pages of Biblical genealogy—family trees which trace an unbroken line of descent from God, Adam, and Eve on the first page to Joseph, Mary, and Jesus on the last.

Selection: The Holy Bible, Conteyning the Old Testament, and the New [The King James Bible], title page, family tree of Adam and Eve, family tree of Jacob (1611).

Questions to Consider

- Examine these two pages from the King James Bible’s genealogies—the first portrays God, Adam, Eve, and their immediate descendants, the second portrays Jacob and his immediate descendants. How is the information on each page organized? What does the organization suggest about family structure?

- Why do you think these family trees were included? Why might Jesus’ lineage matter to Renaissance Christian scholars and laypeople?

- What do the family trees suggest about how people thought about the family and lineage during the Renaissance?

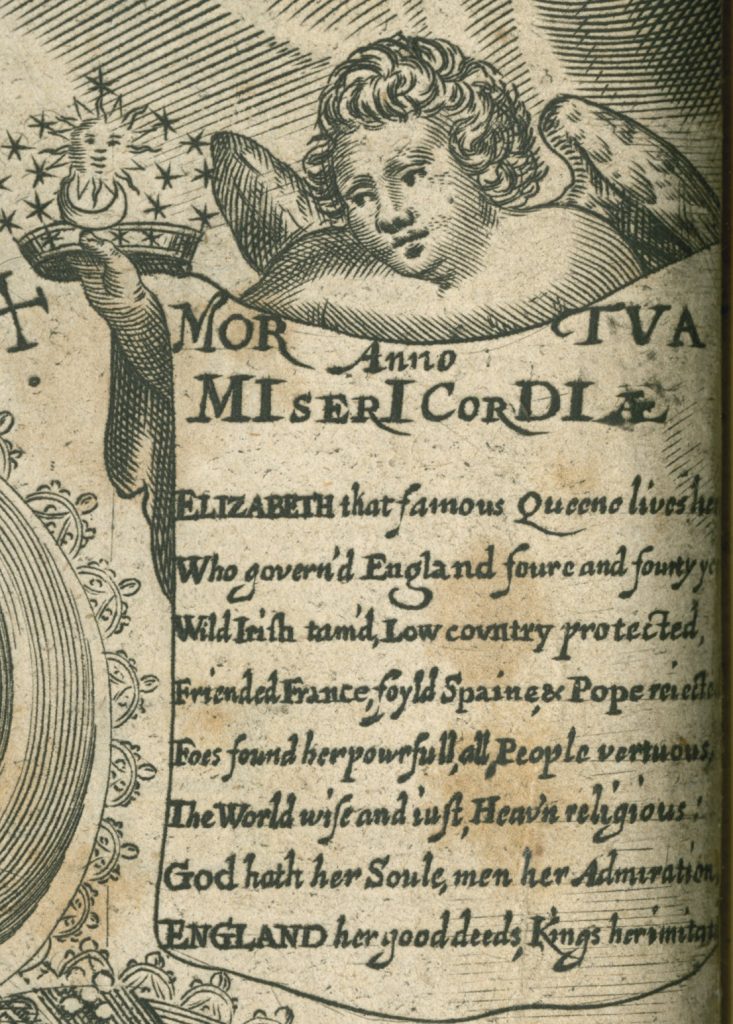

Queen Elizabeth I

Queen Elizabeth I died in 1603 at the age of 70 after 44 years on the throne. Then and now, writers give Elizabeth much of the credit for England’s remarkable prosperity, stability, and cultural achievement during her reign. She shielded the country from the religious wars then tearing apart Europe, and she defeated the Spanish Armada, a great fleet of ships poised to invade England, in 1588. Above all, she was an extraordinarily skillful politician who effectively ruled England in the face of considerable resistance to the idea of a female monarch. Elizabeth did not promote other women to positions of authority or encourage the extension of greater rights to women. But, she provided a powerful model of female independence and self-determination. She carefully crafted her public image, whether as the Virgin Queen devoted to England or as the military commander leading her troops into battle, in ways that provide an important context for Shakespeare’s representations of women and the family. “I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman,” Elizabeth famously declared, “but I have the heart and stomach of a king.”

Selection: Francis Delaram, Annales: The True and Royal History of the Famous Empresse Elizabeth, portrait of Elizabeth I and detail (1625).

Questions to Consider

- How does the frontispiece of William Camden’s Annales portray Elizabeth? In what ways does the image indicate her power? What other attributes does it convey?

- Examine the poem from the frontispiece detail. According to the text, what were Elizabeth’s primary accomplishments and virtues? What role, if any, does her gender play in this tribute?

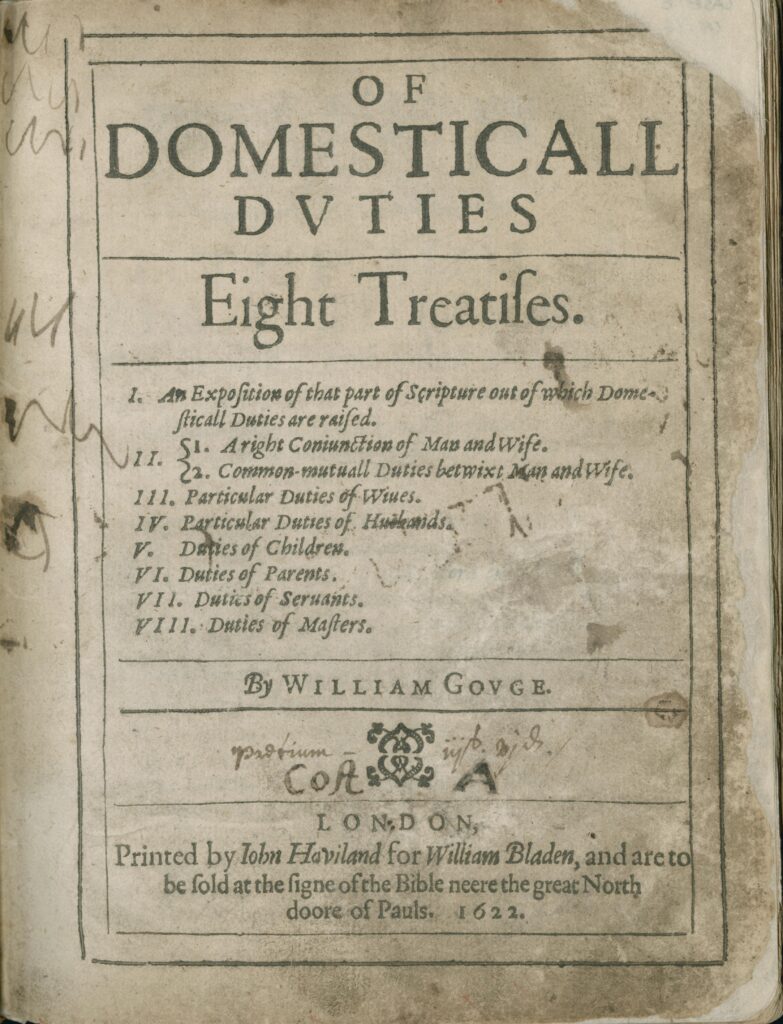

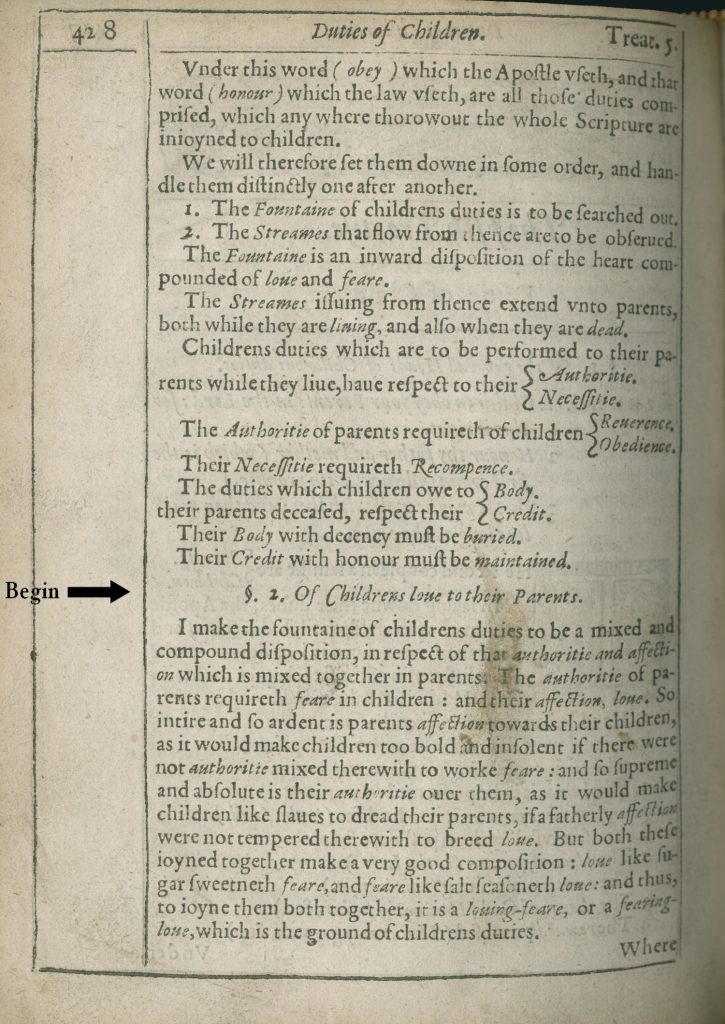

Advice to Husbands, Wives, Parents, and Children

During the Renaissance, as now, advice books were very popular. Following the Protestant Reformation, many of these books (often called conduct manuals) addressed the subject of marriage and the duties of husbands, wives, parents, and children to one another. Some of the most popular are excerpted here. William Gouge was a prominent English Puritan pastor. He explains in the preface to Of Domesticall Duties that the book was based on a series of sermons he delivered to his congregation. He adds, somewhat defensively, that the sermons were criticized as being too harsh on women and seeks to explain his positions at greater length here.

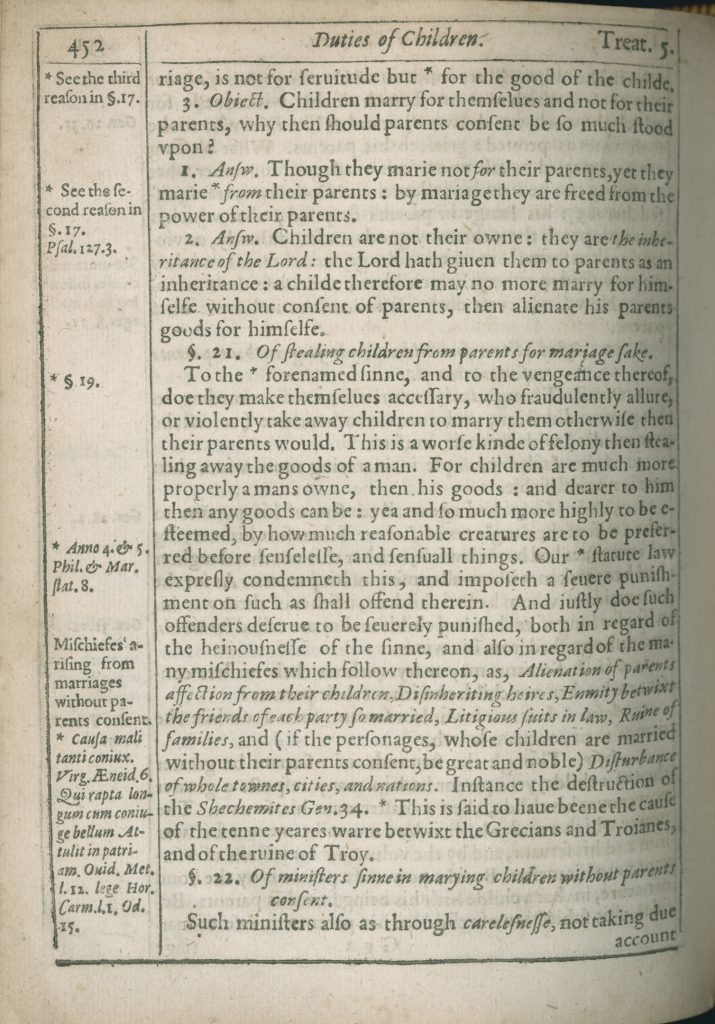

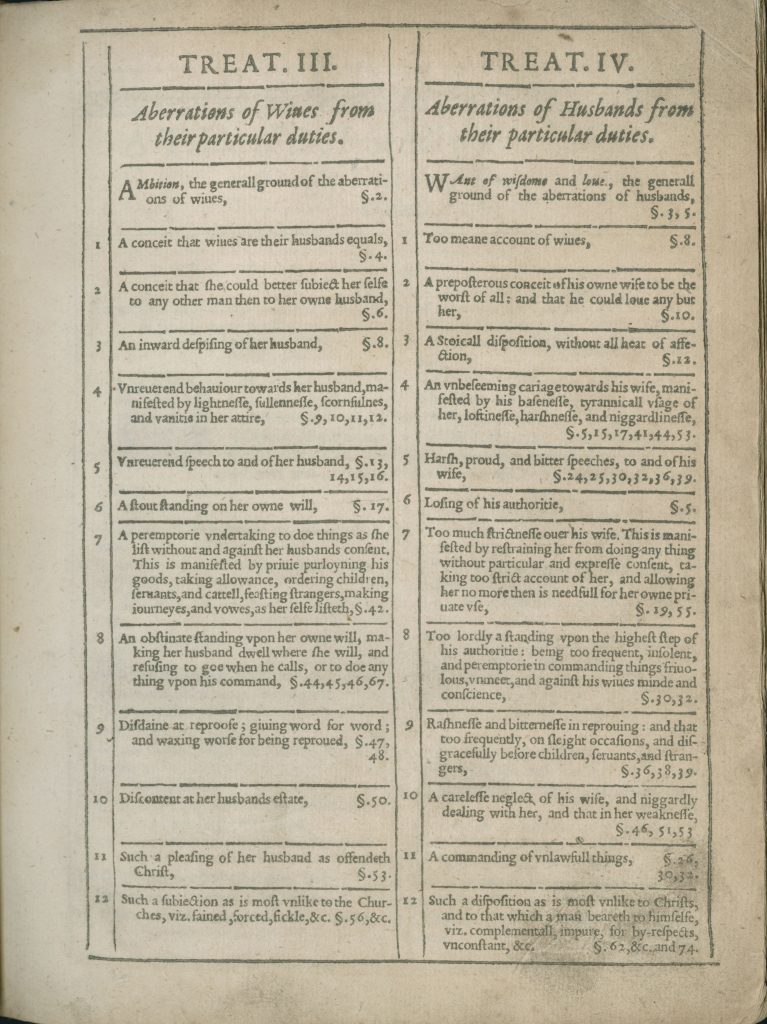

Selection: William Gouge, Of Domesticall Duties: Eight Treatises, title page, 428, 452, “Treat. III – Treat. IV” (1622).

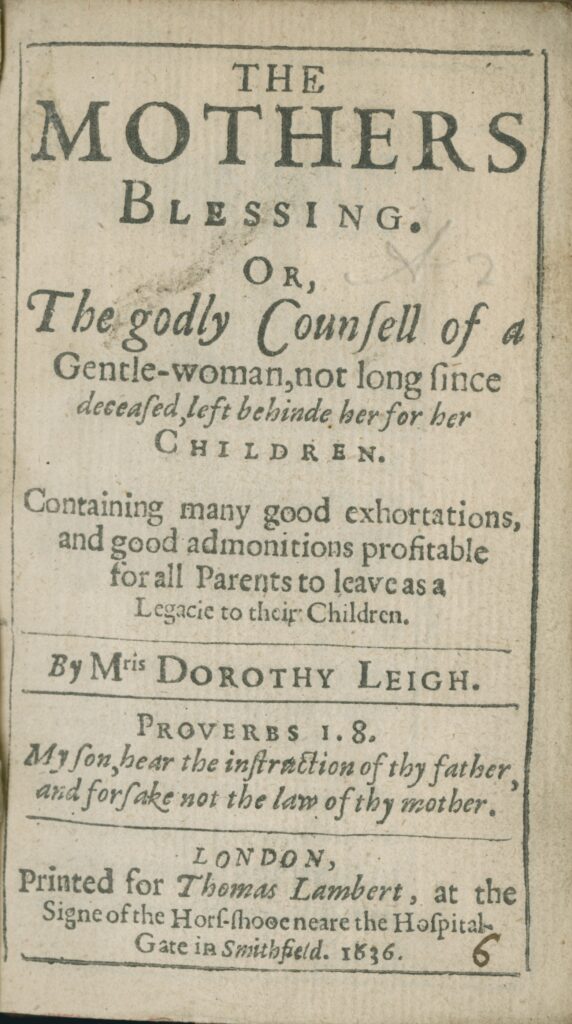

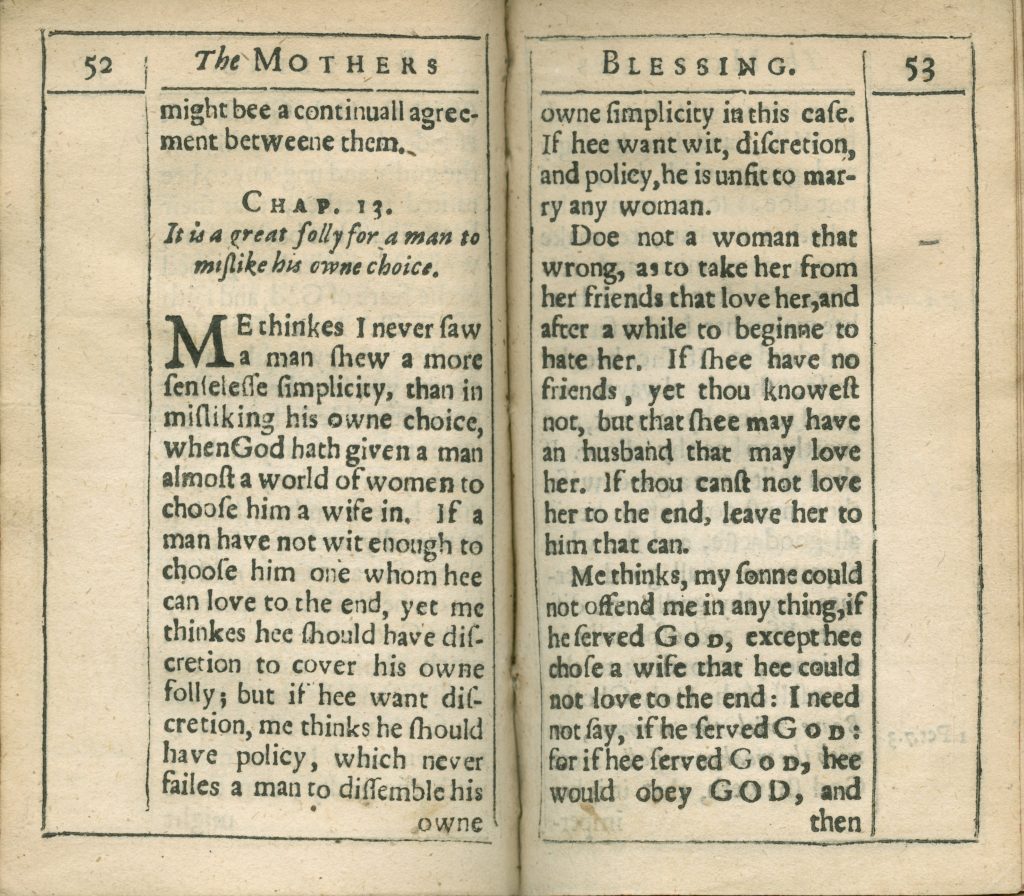

Dorothy Leigh’s The Mother’s Blessing was originally published in 1616 and went through at least 20 editions. The book is addressed to Leigh’s sons from her deathbed, which made the book’s publication more acceptable at the time. It was considered improper for women to publish their writing or to offer moral and religious instruction.

Selection: Dorothy Leigh, The Mothers Blessing: Or, the Godly Counsell of a Gentle-Woman, title page, 52-57 (1636).

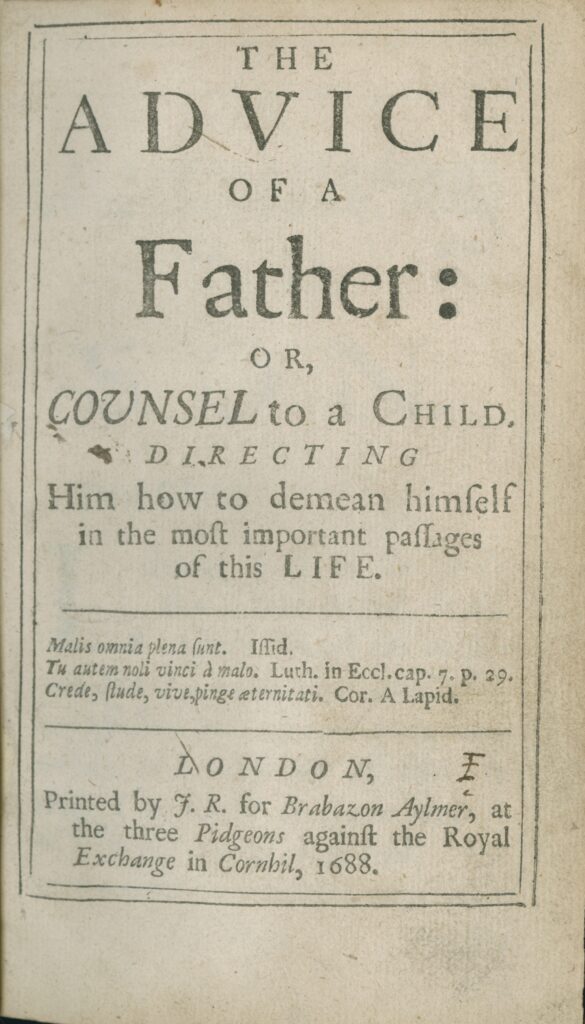

Finally, The Advice of a Father was published anonymously later in the seventeenth century. Like Leigh, this author explicitly addresses his son, but offers plenty of evidence that he had a wider audience in mind.

Selection: The Advice of a Father: Or, Counsel to a Child, title page, 30-33, 36-37 (1688).

Questions to Consider

- What are the duties of wives and husbands according to the table that Gouge provides at the beginning of his book? What are the “aberrations,” or deviations, from those duties? Why is “ambition” the primary quality that undermines the wife’s primary duty of “subjection”? Do husbands have unlimited power over wives according to Gouge’s model?

- What is the child’s duty to the parent, according to Gouge? Why should the child both fear and love his parents? Why do you think Gouge places so much importance on parental approval of a child’s marriage?

- What is Leigh’s advice to her sons concerning marriage? How does she support that advice with evidence from the Bible? Why do you think she places so much emphasis on a husband’s obligation to love his wife? Does her advice on marriage challenge or support Gouge’s?

- What is the author’s critique of the institution of marriage in Advice of a Father? What does he argue is the basis of happiness in marriage? Why does the author caution against having children? In what ways does his advice challenge Gouge’s and Leigh’s?

- What differences do you notice in the advice given by Gouge, Leigh, and the anonymous father? How do these differences between the books shed light on the different experiences and concerns that men and women may have had at this time? Do they suggest areas of conflict or change in the prevailing expectations of women and men?

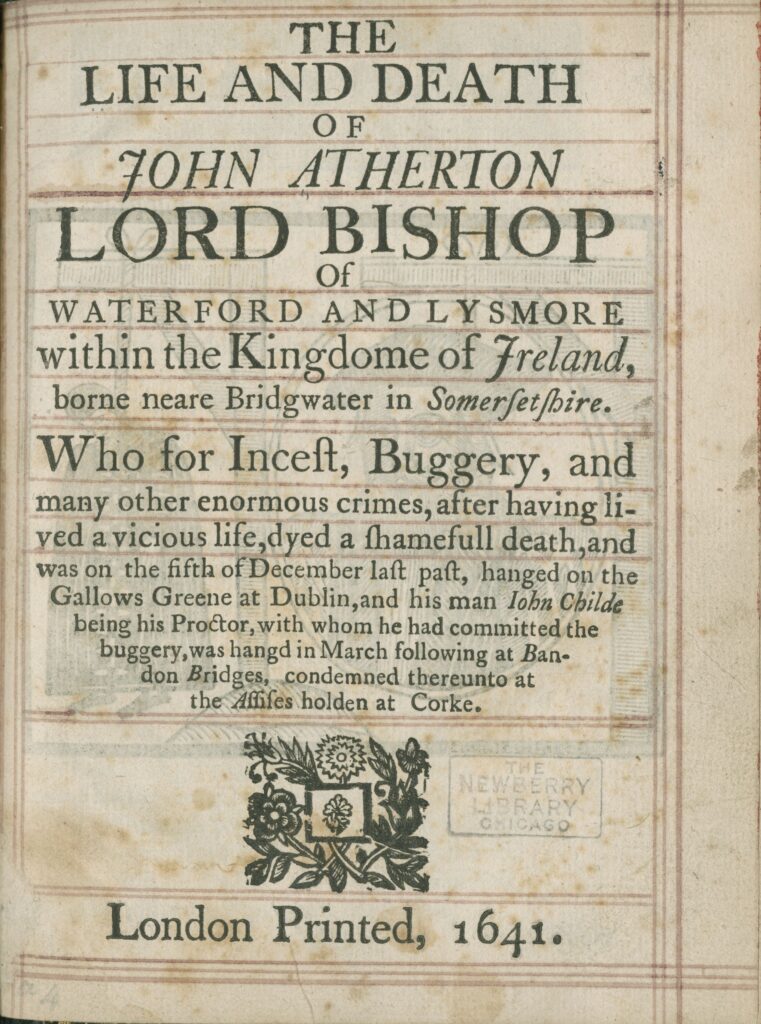

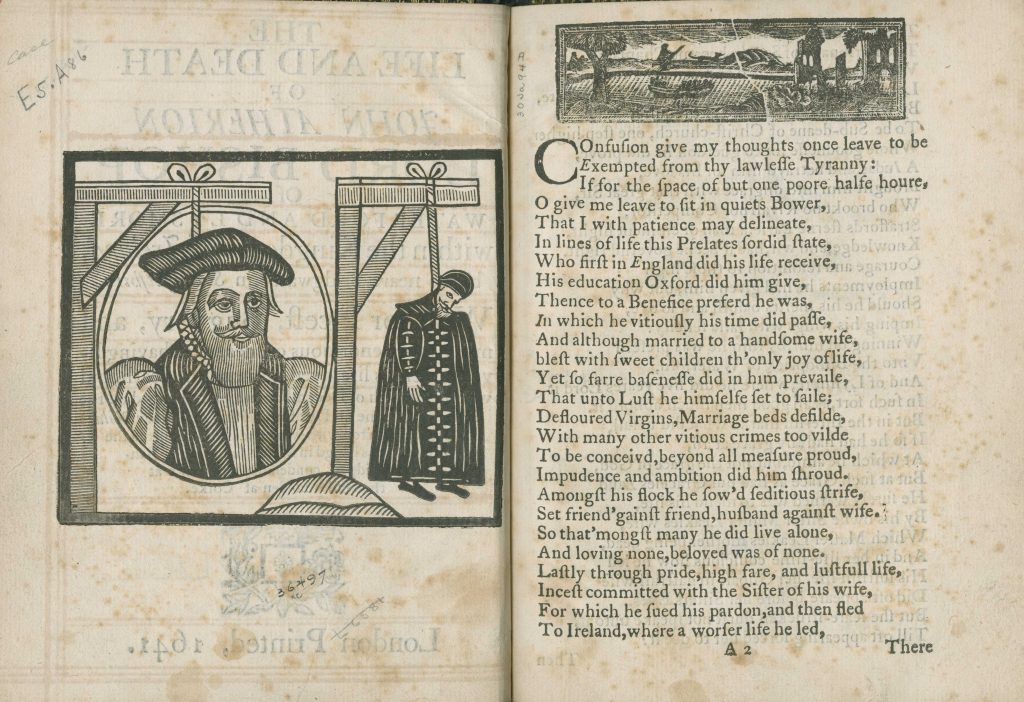

Crimes Against the Family

Seventeenth-century executions were elaborate public rituals attended by hundreds, or even thousands, of spectators. Public officials approached executions as an opportunity to vividly demonstrate the importance of obeying the law. At the moment of death, the condemned criminal was held up as an example of the consequences of crime. Printers increasingly took these events as opportunities to sell inexpensive pamphlets recounting the convict’s life. Like the executions themselves, these publications had a specific, instructional purpose, but also contained sensational elements that could overshadow the intended lesson.

Selection: The Life and Death of John Atherton, title page and frontispiece (1641).

The Life and Death of John Atherton is a pamphlet published several months after Atherton’s execution. Atherton had been a Protestant bishop in the Church of Ireland which was affiliated with the Church of England. Atherton was executed for buggery, or sexual acts with another man, a church official who was also hanged. However, the pamphlet devotes little attention to this crime, emphasizing instead a lifetime of various misdeeds. (Note: A prelate is a high-ranking cleric, or church official. A benefice is financial support provided to a member of the clergy.) A Full Account of a Most Tragycal and Inhuman Murther describes the case from Holland of Claes Wells, who was convicted of murdering his entire family.

Selection: A Full Account of a Most Tragycal and Inhuman Murther, 1-2 (1699).

Questions to Consider

- What does the writer of the pamphlet accuse Atherton of? Why do you think the writer includes so many different examples of unacceptable behavior? What are the relationships between Atherton’s lesser transgressions and the crime for which he is executed? Why does the writer also describe Atherton’s education and clerical positions?

- What does the pamphlet tell us, by negative example, about the expectations for how people should conduct their family and other personal relationships? What kind of behavior is frowned on, but permitted? Why?

- Why do you think London printers found Claes Wells’ case worth publishing, even though it occurred relatively far away, in Holland?

- Based on your reading of the narrative, why do you think Wells committed the murders? What lessons does the writer of the broadside draw?

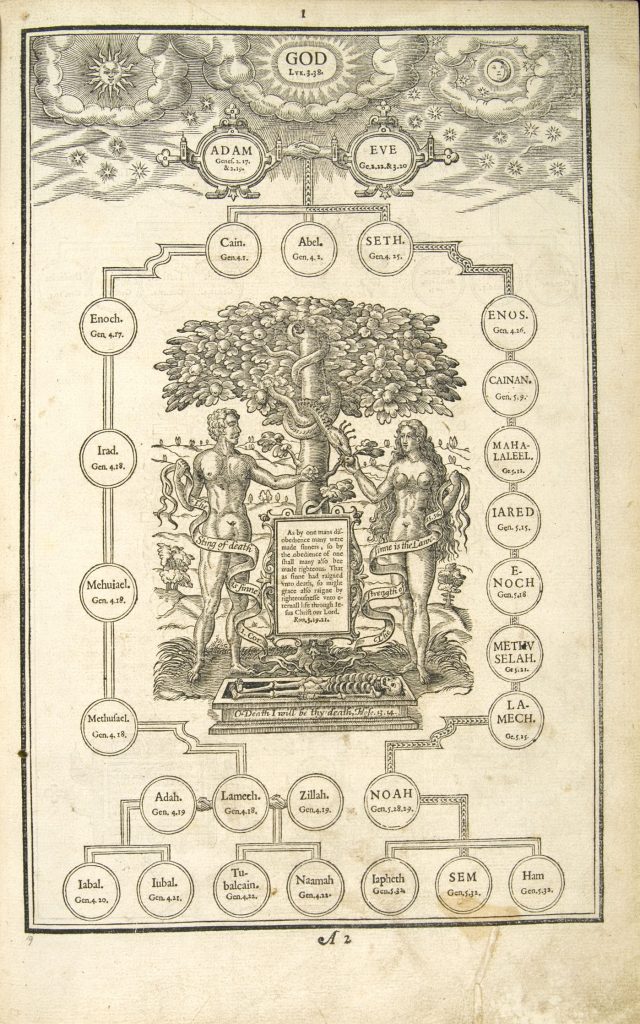

Lear’s Family

Shakespeare’s King Lear remains one of the darkest and most compelling explorations of family relationships in English literature. The play opens with the aging King Lear offering to divide his kingdom between his three daughters according to how persuasively each can express her love for him. Two of his daughters, Goneril and Regan, lavishly proclaim their devotion. But the youngest, Cordelia, refuses to participate in the competition and Lear disowns her. Terrible events unfold as Goneril and Regan betray Lear, he descends into madness, and Cordelia, the daughter who does truly love him, is imprisoned and executed.

The documents presented here include the title page of a 1619 edition of the play (inaccurately identified as 1608 on the title page) as well as an illustration of the first scene, created almost 200 years later. In the late eighteenth century, the London printer and engraver, John Boydell, commissioned artists to create paintings illustrating the works of Shakespeare. He then produced engravings based on their paintings and published them together with Shakespeare’s plays. This plate is based on a work by the Swiss-born Romantic painter Henry Fuseli. The caption quotes Lear’s famous lines to Cordelia: “Thy truth then be thy dower! . . ./ Here I disclaim all my paternal care,/ Propinquity and property of blood,/ And as a stranger to my heart and me/ Hold thee from this for ever.”

Questions to Consider

- Read the title page, a text which may have been used to advertise the play itself. What details about the family drama are included in this early title? What does the title tell us about what this printer thought was most important about the play or would be most useful in selling it?

- Examine each of the figures in the engraving of Act 1, Scene 1. Describe the postures, gestures, and facial expressions of Lear, Cordelia, and others. How does the engraving convey the importance and meaning of Lear’s condemnation of Cordelia? How does Cordelia appear to respond?

- What relationship does the play as a whole have to the instructions included in the advice books and crime literature presented earlier in this collection?

Early Modern Contexts for the Family

Below you will find material related to the social, religious, and political contexts for understandings of the family unit in Shakespeare’s time.

Crimes Against the Family

Below you can see texts documenting family crimes in the Early Modern period, as well as material related to Shakespeare’s King Lear.

Further Reading

Stephanie Coontz. Marriage, a History: How Love Conquered Marriage. 2005.

Clark Hulse. Elizabeth I: Ruler and Legend. 2003.

Mary Beth Rose. “Where Are the Mothers in Shakespeare? Options for Gender Representation in the English Renaissance.” Shakespeare Quarterly 42.3 (1991): 291–314.

Lawrence Stone. The Family, Sex, and Marriage in England, 1500–1800. 1979.