Introduction

Once described by historian David Potter as “the most majestic champion of error since Milton’s Satan,” John C. Calhoun (1782-1850) played a central role in the sectional conflict over slavery that divided the United States during the first half of the nineteenth century and that would eventually result in the Civil War after his death. This digital collection includes materials held by the Newberry Library related to Calhoun and the sectional crisis from a variety of different perspectives.

It was during his term as Jackson’s Vice-President that Calhoun drew on arguments first made Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the Virginia an Kentucky Resolutions to craft his doctrine of “state interposition” or nullification”

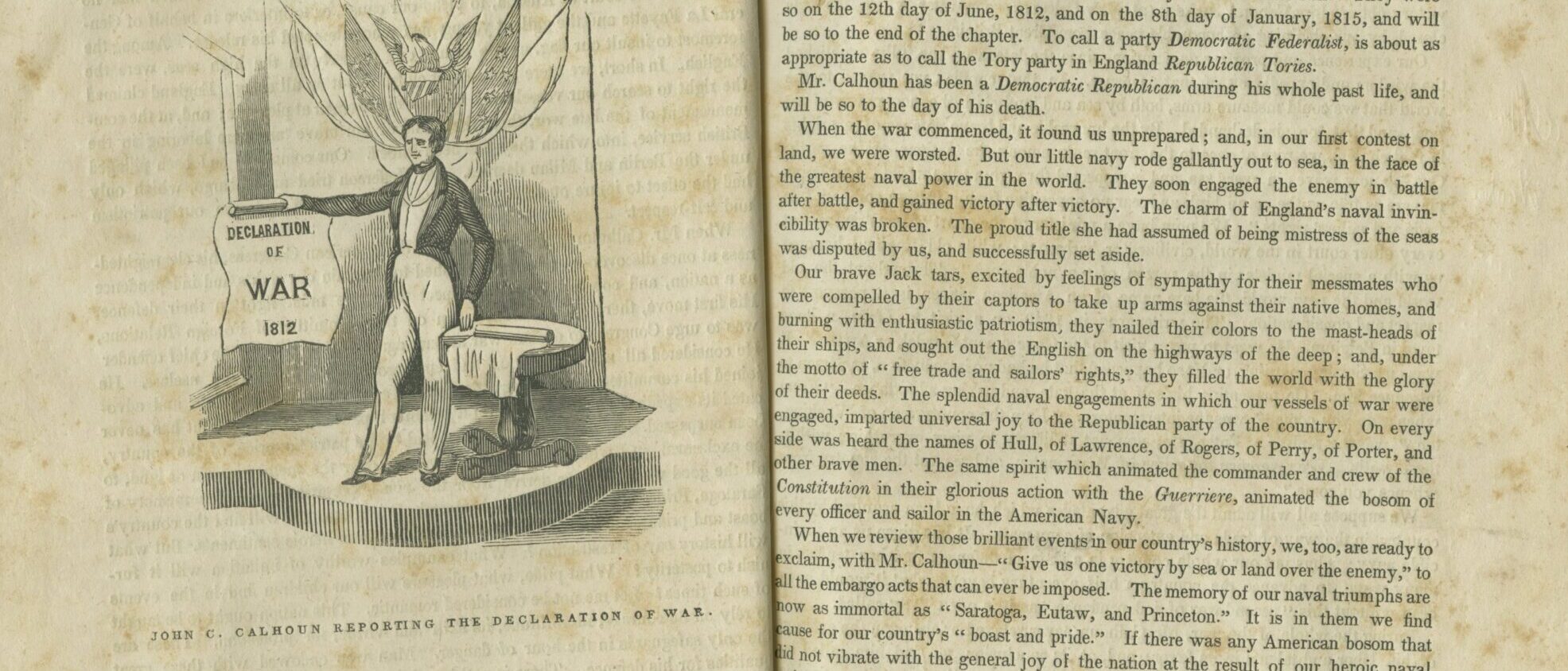

Born to Scots-Irish immigrants in the backcountry of South Carolina in 1782, Calhoun was educated at Yale and elected to Congress in 1810. He played a central role in the War of 1812 as one of the “War Hawks,” a nationalistic group of young politicians who favored a vigorous defense of American sovereignty against the British. After the war Calhoun served as Secretary of War in the Monroe administration from 1817 until 1824. During his tenure as Secretary of War Calhoun was responsible for modernizing the United States military and for dealing with Indian relations. While harboring his own presidential ambitions, and initially entering the presidential race in 1824, Calhoun eventually served as Vice-President under both John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson.

It was during his term as Jackson’s Vice-President that Calhoun drew on arguments first made by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions to craft his doctrine of “state interposition” or nullification, provoking a showdown between South Carolina and the national government in 1832. The immediate cause of the crisis was a tariff passed in 1828, the so-called “Tariff of Abominations,” which many southerners viewed as violating the constitution’s requirement that all taxation be applied equally since it protected northern manufactures at the expense of southern plantation owners, who had to buy manufactured goods at artificially inflated prices while they sold their cotton on an open market. As Calhoun argued, first in his South Carolina Exposition and Protest (1828) and then in his Fort Hill Address (1831), South Carolina had the right to nullify the tariff because the federal Union was a “compact” of sovereign entities, the states, who had reserved for themselves any powers not expressly given to the federal government. Calhoun argued that since the states preceded the creation of federal government by the United States Constitution, and since they had agreed to it only for the purposes expressed in the constitution, they had the power to reject as unconstitutional laws passed by Congress. Many of Calhoun’s contemporaries, including Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, strongly disagreed with Calhoun’s arguments in a series of the most famous debates in American history. The crisis only ended when a compromise, brokered by Henry Clay, emerged in which South Carolina agreed to a revised tariff in which duties on imported goods would decrease steadily.

Although slavery was also the proximate cause of the constitutional debate over tariffs, Calhoun soon focused his energy directly on the issue of slaveholders’ rights in the Union. Parting with an earlier generation of southerners who viewed slavery as a necessary evil, as a U.S. Senator during the 1830s Calhoun formulated a defense of the peculiar institution as a “positive good” in a white democracy and became the foremost advocate of slaveholders’ right to carry their peculiar form of property into the new territories added by American imperialism in Mexico and the West. Responding to increasing pressure from a coalition of anti-slavery forces, including abolitionists and free soilers, Calhoun committed the South to a position on slavery that allowed little room for compromise.

At the end of his life, as the revolutions of 1848 raged in Europe and arguments over California statehood revealed a stark sectional divide in the United States, Calhoun set down his political philosophy in two of the most controversial and consequential treatises in American history, A Disquisition on Government and A Discourse on the Constitution and Government of the United States, both published posthumously. In these, Calhoun laid the philosophical groundwork for secession and made the argument that every group in a society should possess ironclad veto power in any legislative process, an idea that he called the concurrent majority. After his death, Calhoun’s ideas became central to southern arguments for secession during the 1850s.

Calhoun is often portrayed in American history textbooks as an outmoded, if brilliant, reactionary who made arguments about states’ rights, secession, and slavery that had no place in a modern world that progressed steadily toward nationalism and broad definitions of human rights and freedoms. And yet still today secession remains one of the most explosive issues facing modern constitutional democracies. As recently as 2017 Catalonia, a region of Spain, voted to secede, sparking a constitutional crisis. And according to the Harvard historian David Armitage, of the 484 separate wars that were fought between 1816 and 2001, 296 were civil wars, and 109 of those were fought for the right to secede from an existing state in order to create a new one. Some contemporary philosophers, such as Washington University’s Christopher Wellmon, have argued for a right to self-determination as a primary right that should privilege the desire of groups or regions within existing nation-states to peacefully secede if they fulfill certain criteria. In this context, Calhoun’s arguments seem frighteningly relevant and strikingly modern. Indeed, he was one of the first political thinkers in the era of the modern nation state to struggle with the question of how a modern nation can be unmade.

Furthermore, the legacies of Calhoun’s arguments about slavery, like the legacy of slavery itself, are still very much with us today. Calhoun’s argument for slavery as a positive good, based on the racial inferiority of black people, continued to be defended long after the Civil War ended the actual institution of slavery, helping to justify legalized segregation in the South and the North. And while Calhoun’s arguments about slavery as a “positive good” may seem positively medieval, recent historians like Sven Beckert have shown that in the decades after Calhoun’s death similar arguments were used to justify European domination of dark-skinned peoples in far-flung parts of the globe as part of a global “Empire of Cotton” that created modern capitalism and lasted into the twentieth century. So, whether we like it or not, John C. Calhoun is still very much with us today.

Essential Questions:

- What are some of the key issues that seem to recur in these documents and speeches?

- How do these different documents portray Calhoun from different points of view (a campaign biography, a speech by a political opponent, a eulogy, etc.)?

Early Career

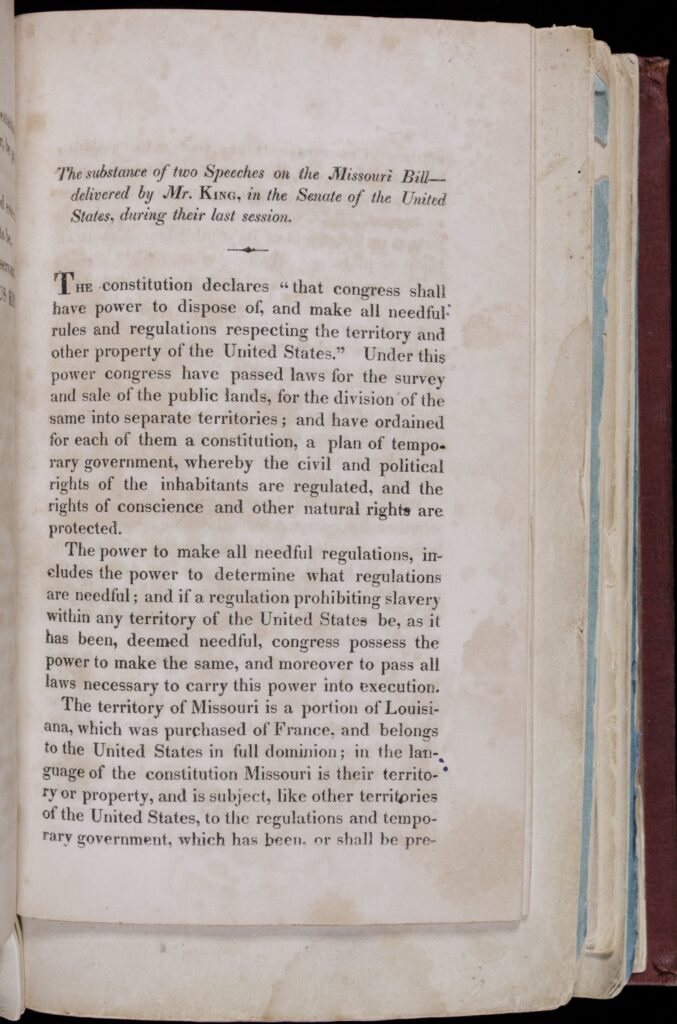

After graduating from Yale University in 1804, Calhoun studied law at the famous Litchfield Law School under Tapping Reeve before returning to South Carolina, where he was elected first to the South Carolina Legislature and then, in 1810, to the U.S. House of Representatives, where he achieved national prominence as a “War Hawk” during the War of 1812. Calhoun was serving as Secretary of War in James Monroe’s cabinet when the crisis over Missouri statehood erupted in 1819, and so he did not publicly debate the question of whether Congress could restrict slavery in states joining the Union, but the debate (represented here by a speech from New York Senator Rufus King) would shape the rest of his career.

Selection: John C. Calhoun, The Life of John C. Calhoun: Presenting A Condensed History of Political Events from 1811 to 1843, 3-5 (1843).

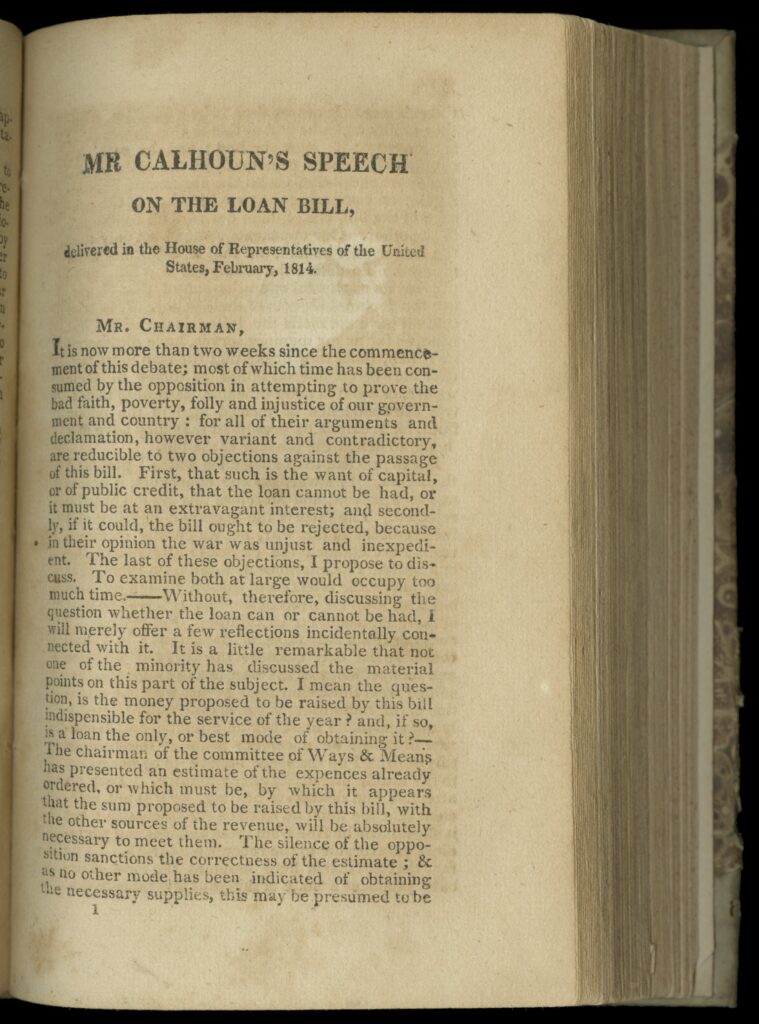

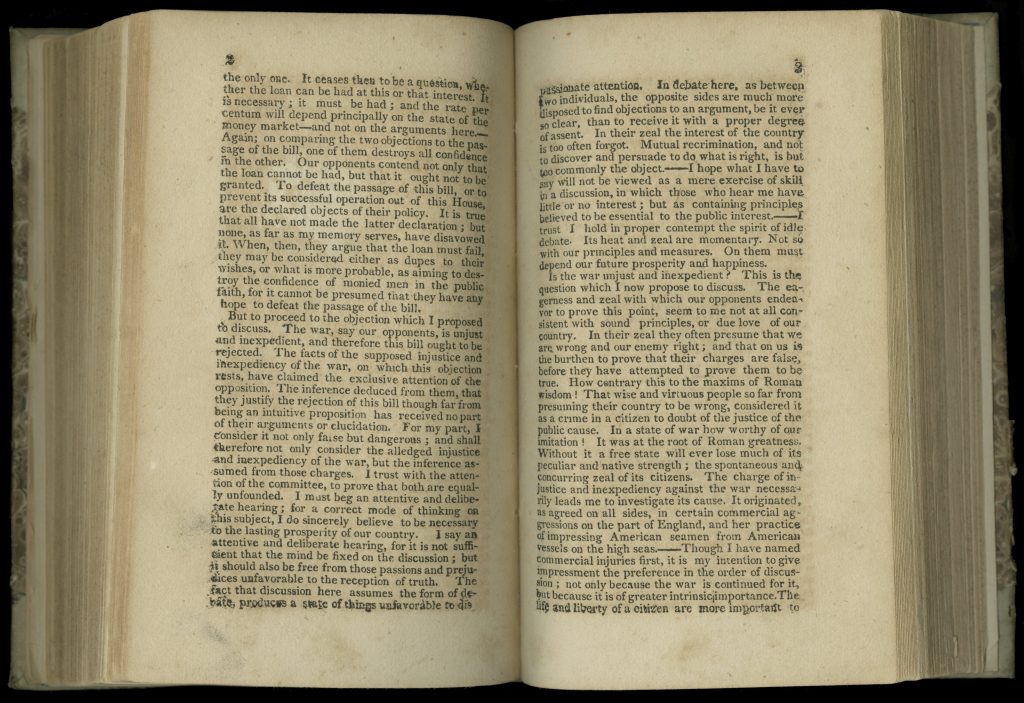

Selection: John C. Calhoun, “Mr. Calhoun’s speech on the loan bill: delivered in the House of Representatives of the United States, February, 1814, 1-5 (1814).

Selection: Rufus King, Substance of two Speeches, delivered in the Senate of the United States, on the Subject of the Missouri bill (1819)

Questions to Consider:

- What seems to be John C. Calhoun’s attitude toward his country in these documents? Can you see any hints of his future career?

- Why does Rufus King argue that the federal government has the right to limit slavery in the territories?

Nullification

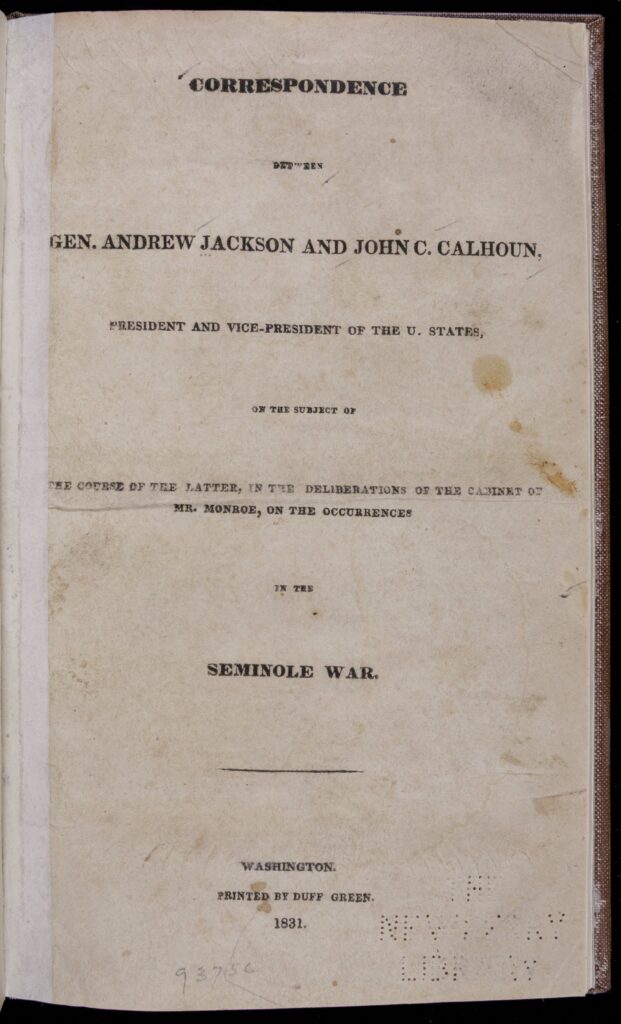

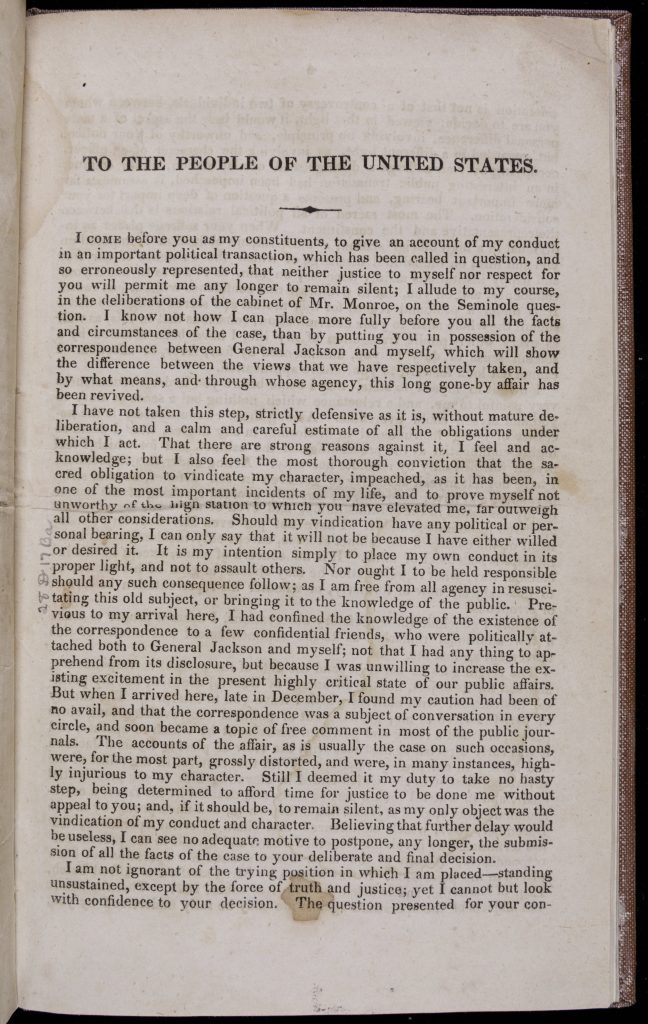

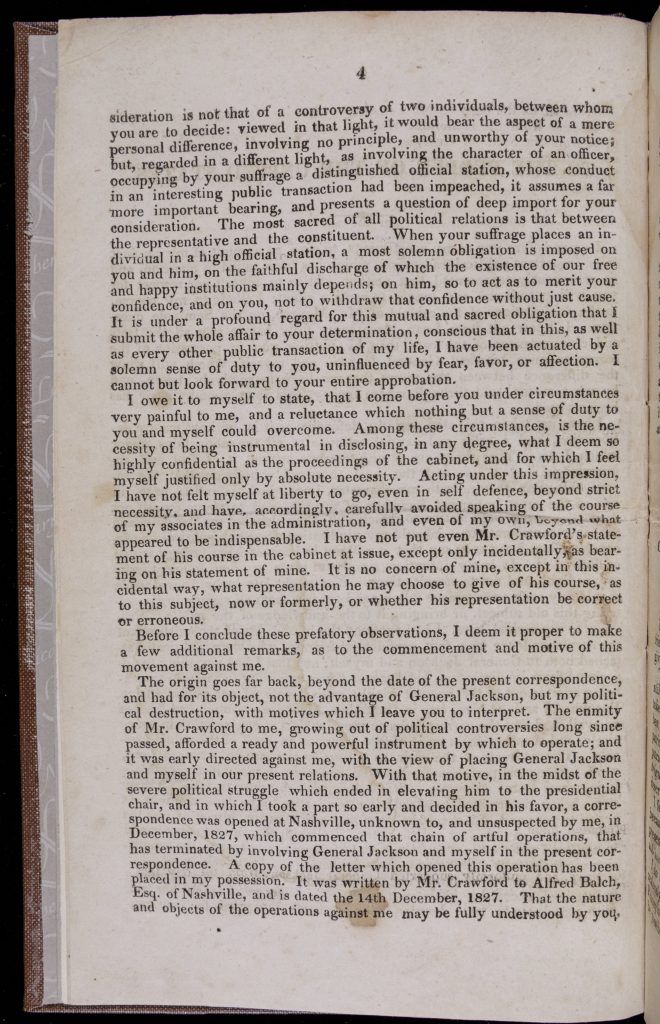

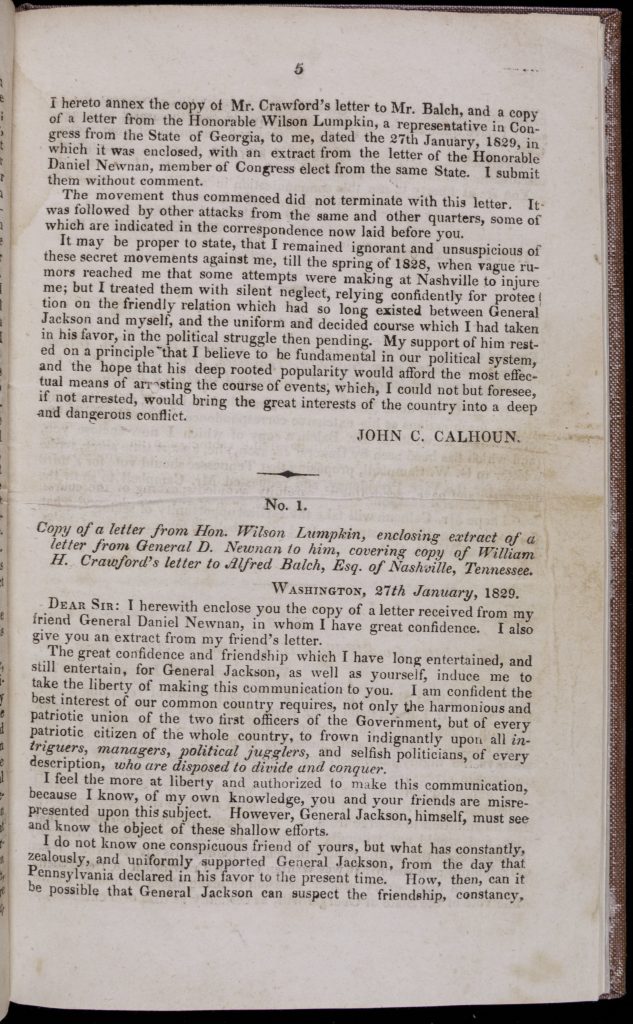

During Andrew Jackson’s first term as president, a constitutional crisis erupted over an 1828 tariff, called the “Tariff of Abominations” by its opponents, which many white southerners viewed as unconstitutional since it protected northern manufacturers against foreign competition, thereby ensuring that the export economy of the South would pay higher prices for manufactured goods. While still serving as Jackson’s Vice-President, Calhoun secretly authored the South Carolina Exposition and Protest, in which he drew on ideas first put forth by James Madison and Thomas Jefferson to argue that a state could “interpose” itself between the federal government and its citizens, nullifying an unconstitutional law. He further elaborated this idea in his Fort Hill Address in 1831, after he had resigned as Jackson’s vice-president. One of the central features of the nullification crisis was the antipathy that developed between Andrew Jackson and Calhoun, owing partly to Jackson’s belated discovery in the midst of the crisis that as Secretary of War in James Monroe’s administration Calhoun had condemned Jackson’s actions during the Seminole War and advocated that Jackson be punished for overstepping his authority. Accused of duplicity by William H. Crawford, another member of Monroe’s cabinet at the time, Calhoun took the unusual step in 1831 of publishing, with the help of his ally Duff Green, the correspondence between himself and Jackson concerning events that happened a decade earlier (see below). The publication of this correspondence marked a public rupture between Calhoun and Jackson that would have enduring political consequences for Calhoun.

Selection: Correspondence between Gen. Andrew Jackson and John C. Calhoun, then President and Vie-President of the U. States, on the Subject of the Course of the Latter, in the Deliberations of the Cabinet of Mr. Monroe, on the Occurrences in the Seminole War, title page, 3-5 (1831).

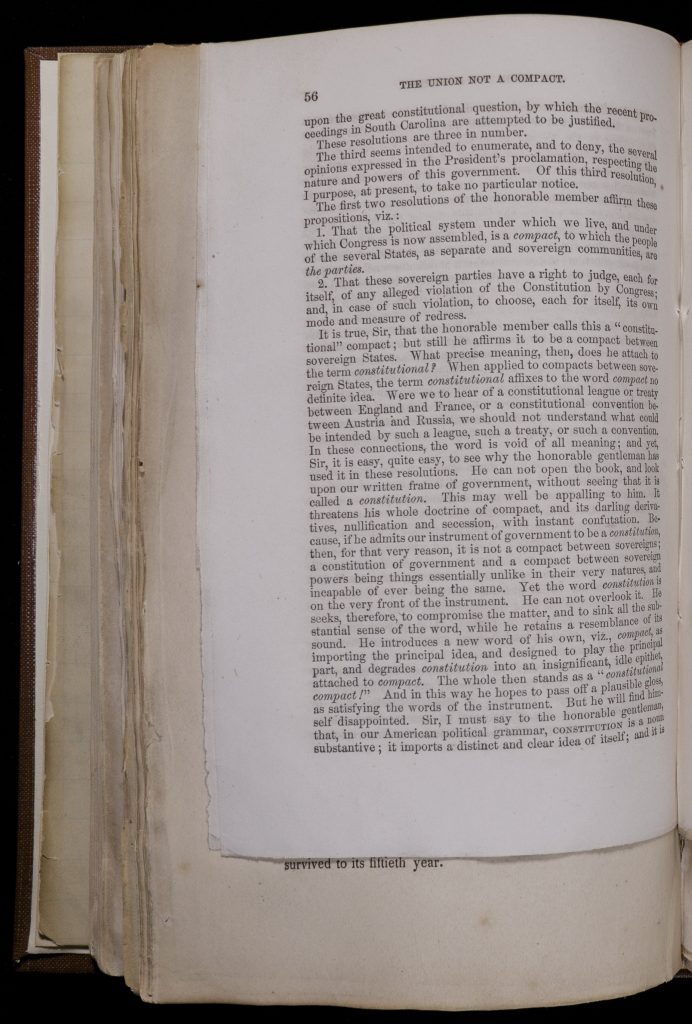

By early 1833, still in the midst of the nullification crisis, Calhoun had returned to Washington as a U.S. Senator. He lost no time offering a series of resolutions stating “That the people of the several states, composing these United States are united as parties to a constitutional compact, to which the people of each state acceded as a separate sovereign community, each binding itself by its own particular ratification…” Viewed by many as a dangerous and unworkable idea, Calhoun viewed nullification as a means of preserving the balance of power between state and federal governments within a constitutional “compact” in which states retained their sovereignty, an idea that other such as Daniel Webster (below) thought ridiculous.

Selection: George McDuffie, Mr. McDuffie’s speeches against the prohibitory system; delivered in the House of Representatives, in April & May, 1830, title page, 3-6 (1830).

Selection: A Catechism on the Tariff: for the Use of Plain People of Common Sense, title page, preface, 3-5 (1831).

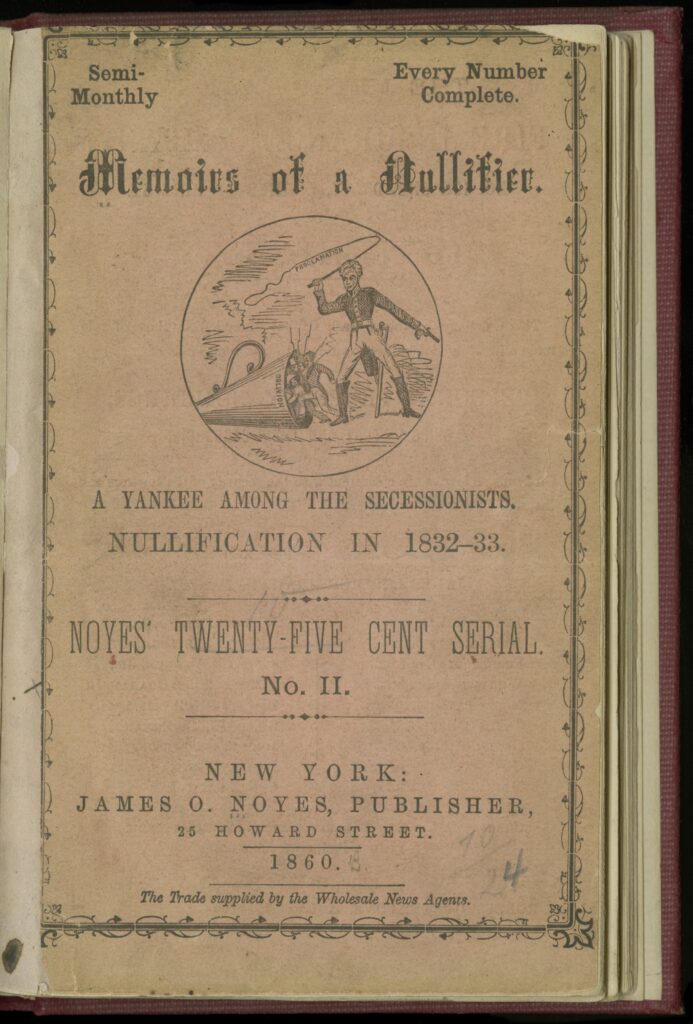

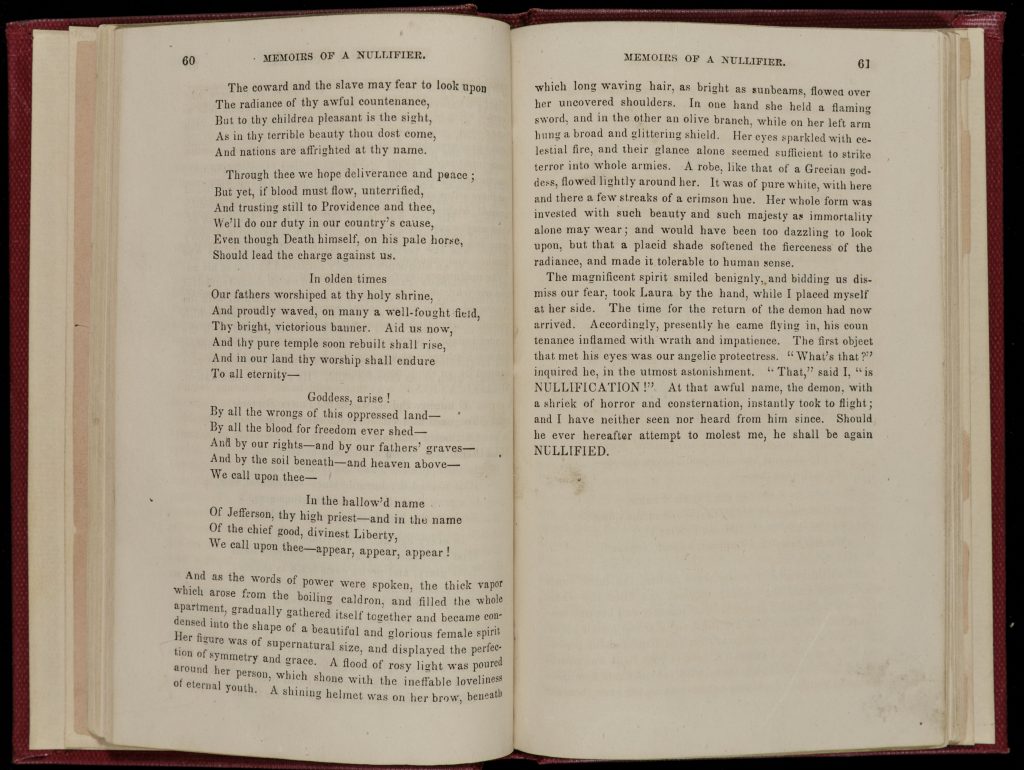

Selection: Algernon Sidney Johnston, Asa Greene, and Thomas Cooper, Memoirs of a Nullifier: A Yankee Among the Secessionists. Nullification in 1832-33. title page, 58-61 (1860).

Selection: Proceedings of the state rights celebration, at Charleston, S.C., July 1st, 1830. Containing the speeches of the Hon. Wm. Drayton & Hon. R.Y. Hayne, who were the invited guests; also of Langdon Cheves, James Hamilton, Jr., and Robert J. Turnbull, Esqrs., title page, 1 (1830)

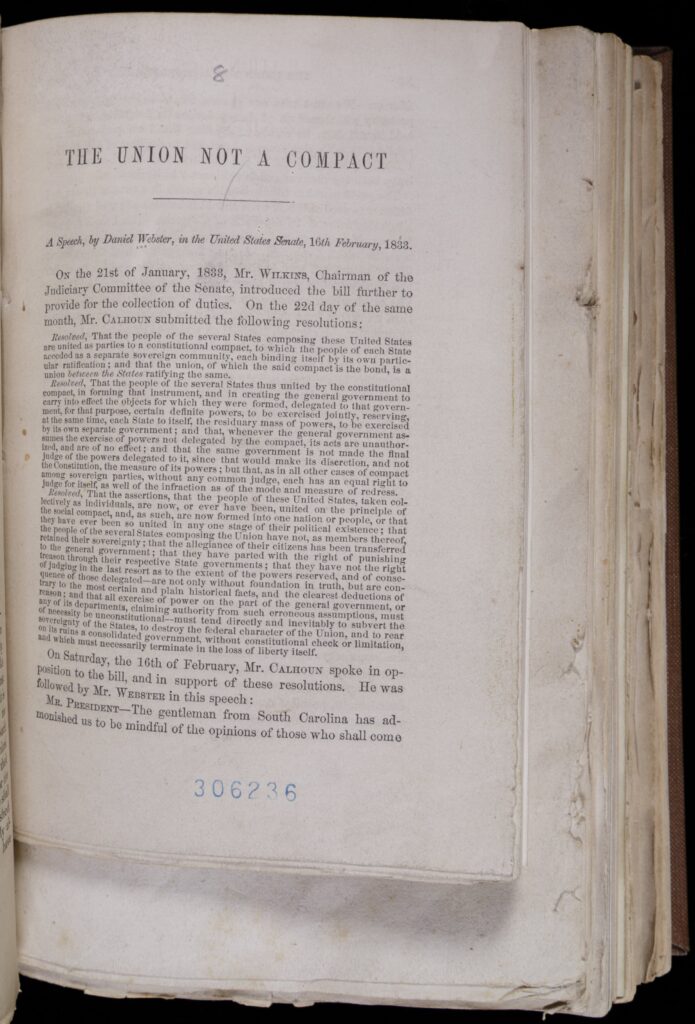

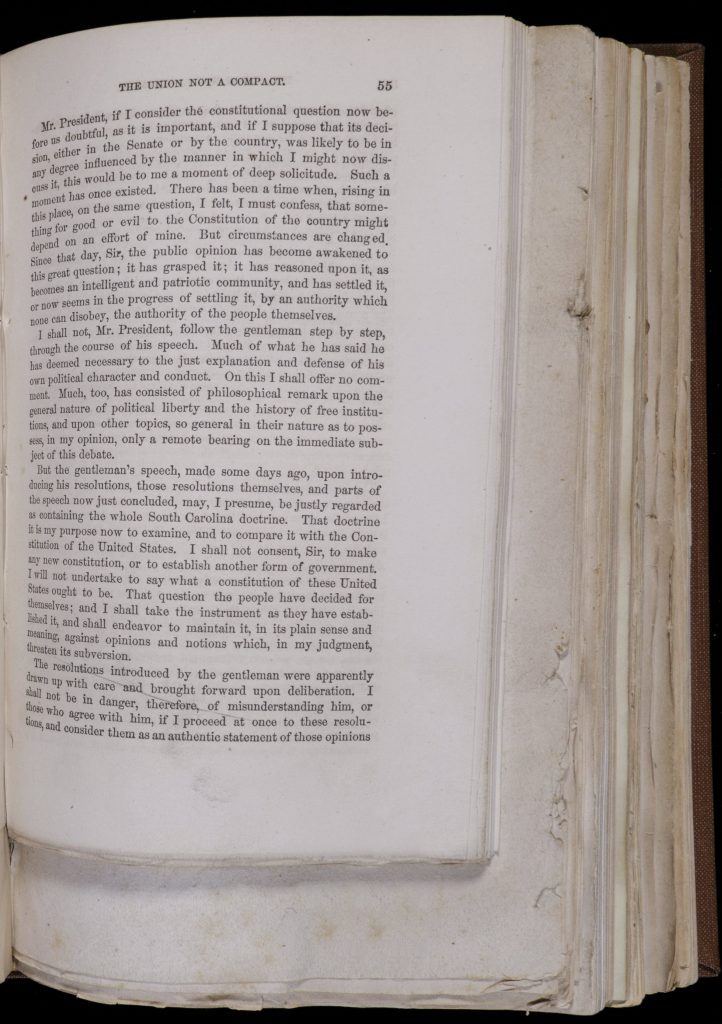

Selection: Fletcher Webster, The Union is not a Compact, A Speech…on the Force Bill in the United States Senate, 53-56 (1860).

Questions to Consider:

- How does Calhoun justify publishing the correspondence between himself and Jackson on the Seminole War?

- What are the different attitudes and arguments towards nullification or “state rights” found in the documents in this section?

Secession and Memory

Calhoun died on March 31, 1850, in the midst of the debate over California’s admission into the Union that would result in the Compromise of 1850. In his final speech in the Senate, Calhoun warned that if slaveholders were not allowed an equal stake in the new territories gained from Mexican-American War, they would have no choice but to secede. After Calhoun’s death in 1850, his ideas continued to animate the sectional debate over slavery and secession. Even after the Civil War ended, Calhoun continued to represent for many white southerners the ideas and principles that they claimed were at stake in the Civil War, which many Americans, North and South, were soon willing to deny was about slavery at all.

Selection: William Lowndes Yancey, An address on the Life and Character of John Caldwell Calhoun, title page, 5, 47-48 (1850).

Selection: H. Von Holst, John C. Calhoun, title page, 1 (1888).

Selection: Ladies’ Calhoun Monument Association, A History of the Calhoun Monument at Charleston, S.C., title pages, 41-43, 58-60 (1888).

Questions to Consider:

- How is Calhoun remembered differently in the documents below? Is one more accurate than the others? Is one less accurate? Why?

- Does the context of each remembrance, as well as who is doing the remembering, seem to influence how Calhoun is portrayed?

Further Reading

Margaret L. Coit, John C. Calhoun – American Portrait (Amberg Press, 2007).

Gustavus M. Pinckney, The Life of John C. Calhoun (Walker, Evans & Cogswell Co., 1903).

John Niven, John C. Calhoun and the Price of Union: A Biography (Louisiana State University Press, 1988).