Introduction

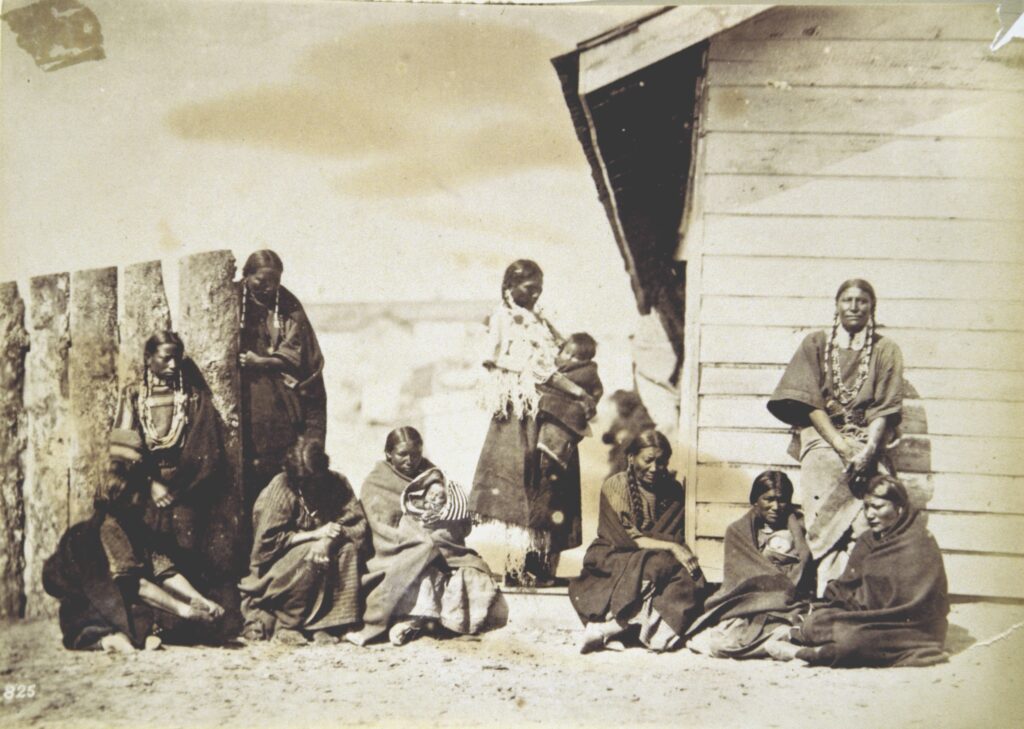

From early contact periods through the nineteenth century, artists, anthropologists, soldiers, and travelers produced representations of Indian peoples in a variety of media including drawings and paintings, mass-produced prints, photographs, and illustrations for books and periodicals. These images were extremely popular with American and European audiences, and these various visual representations shaped American national identity and perceptions of America’s indigenous peoples.

This collection focuses on artwork from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and includes works by both American Indian and Euro-American artists.

While examining the artwork in this collection, consider the following questions:

- Who is the artist?

- Who is the intended audience?

- What is the purpose or message of the artwork?

- What is the historical context surrounding the piece?

Essential Questions:

- How have Euro-American and American Indian artists portrayed indigenous people through various forms of artwork?

- What can we learn about our past and ourselves from artworks that portray indigenous peoples?

- What makes something American Indian art; is it the background of the artist, the style, technique or materials used, the subject of the artwork?

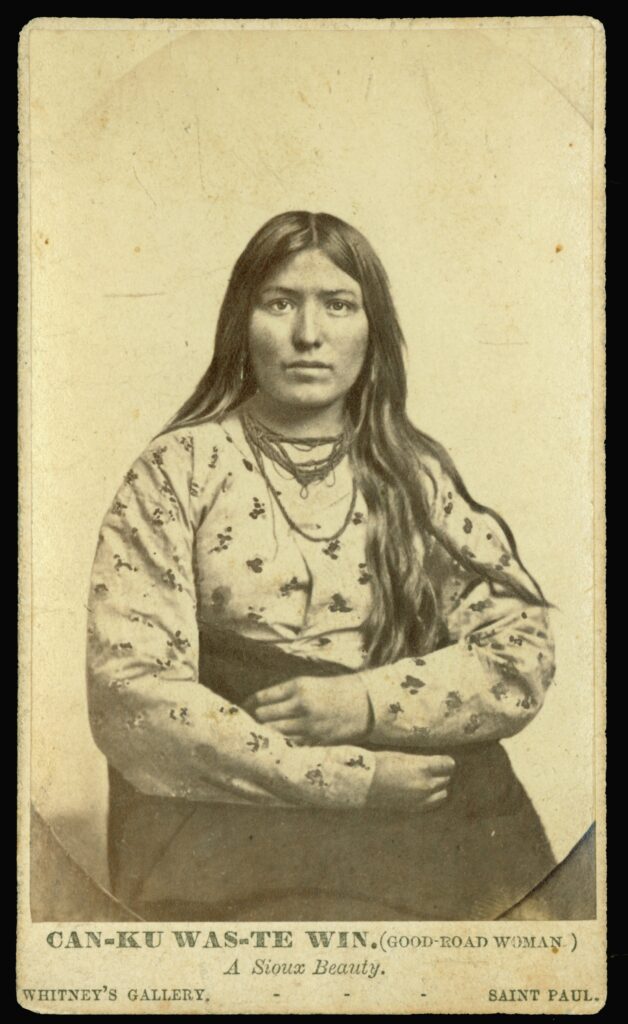

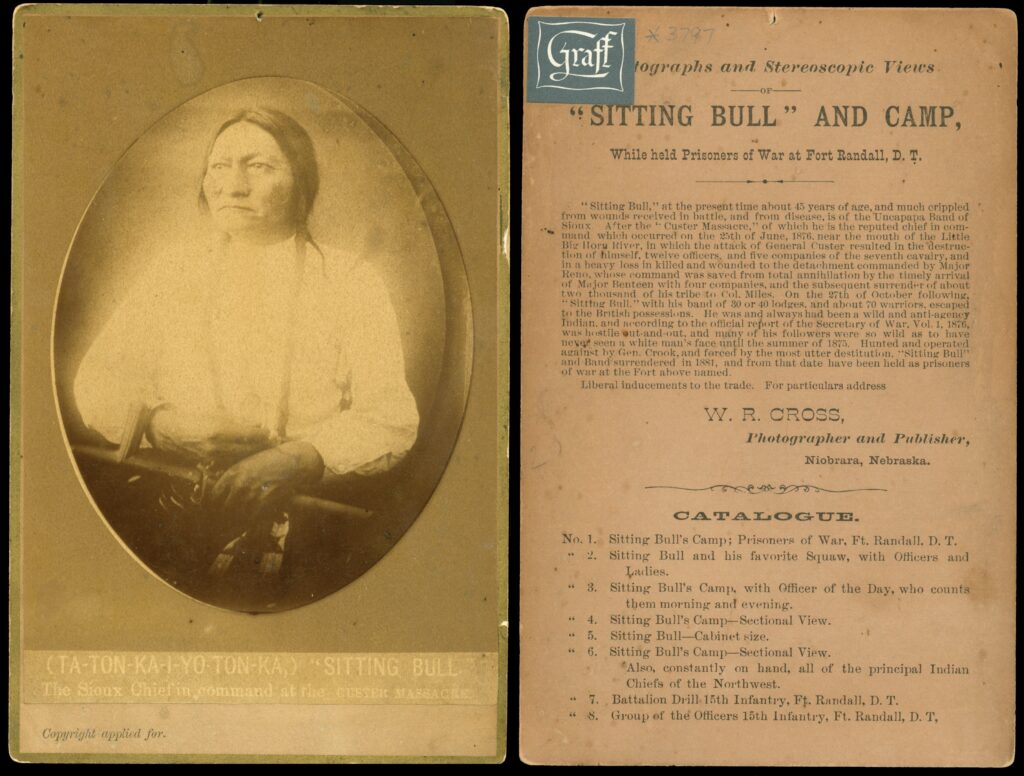

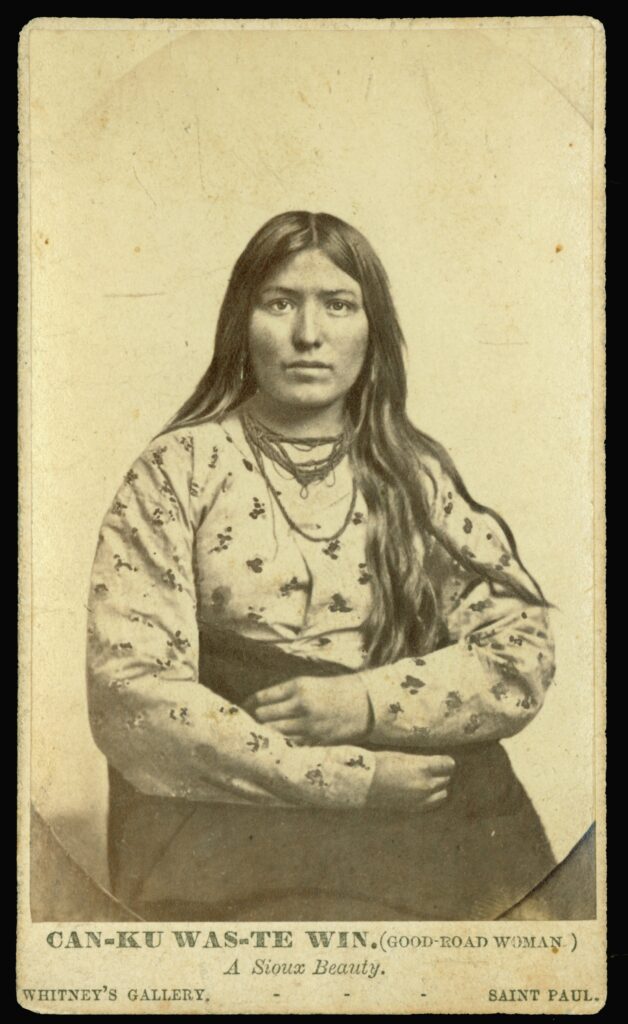

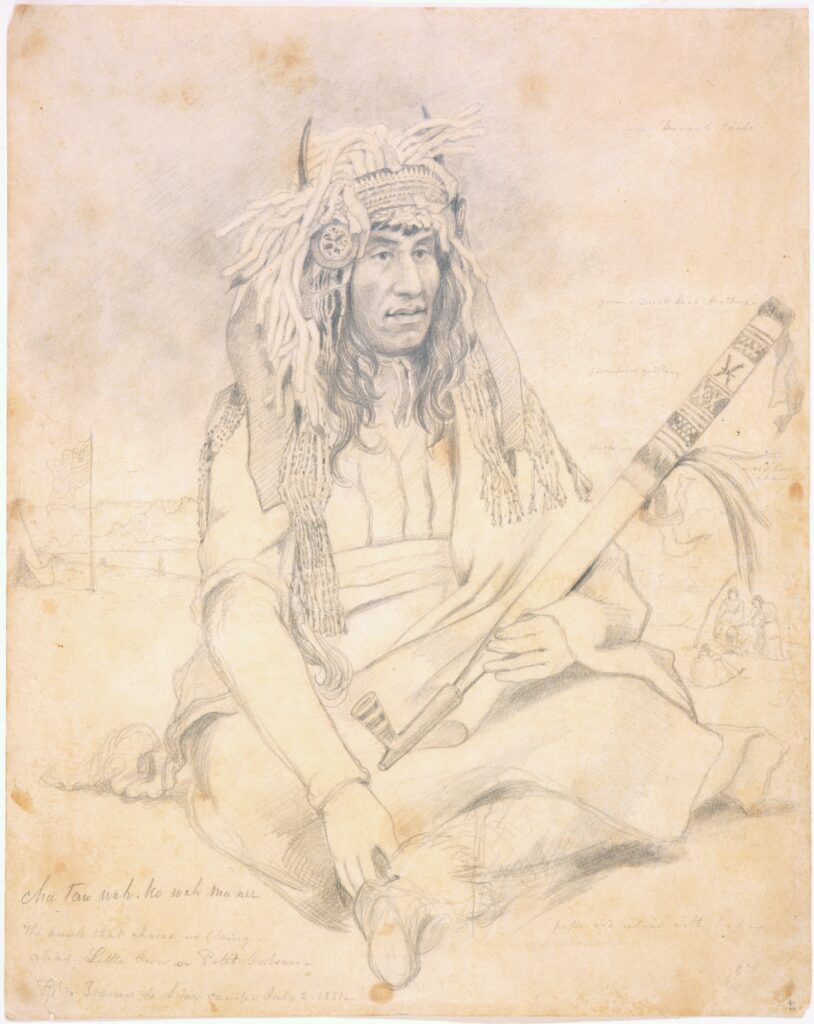

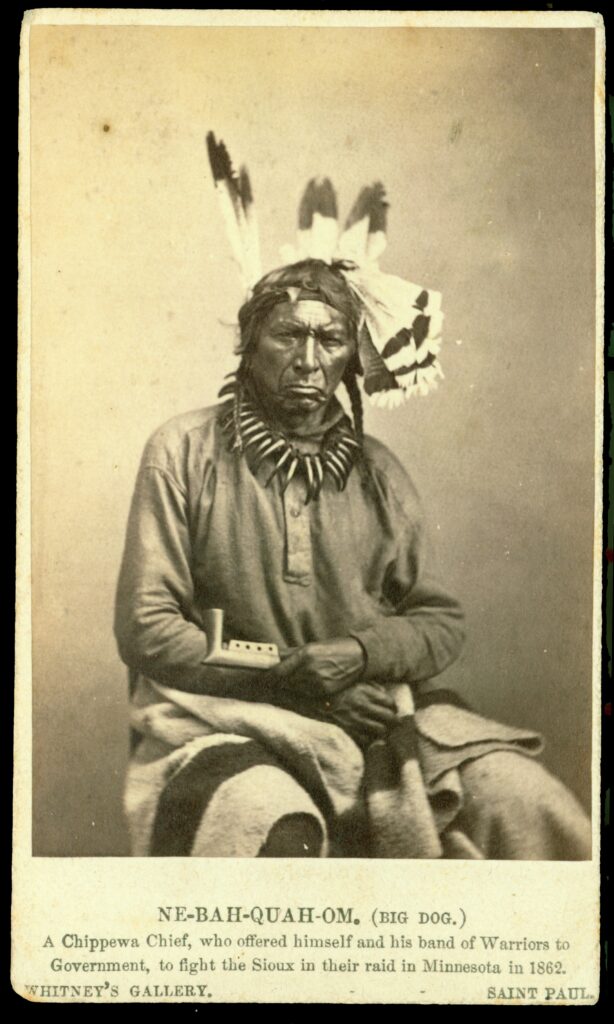

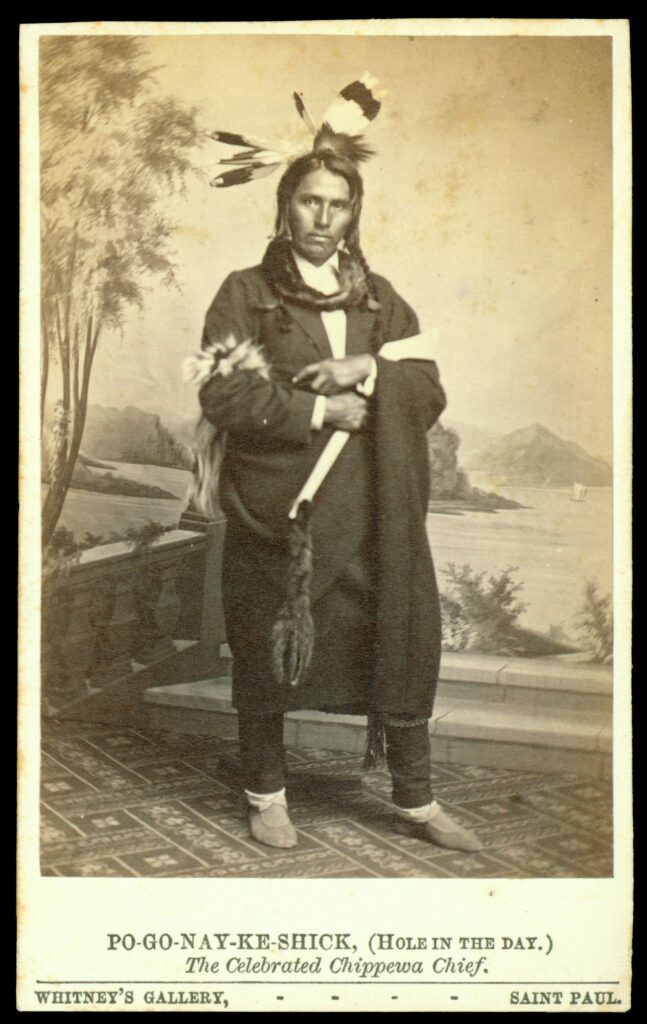

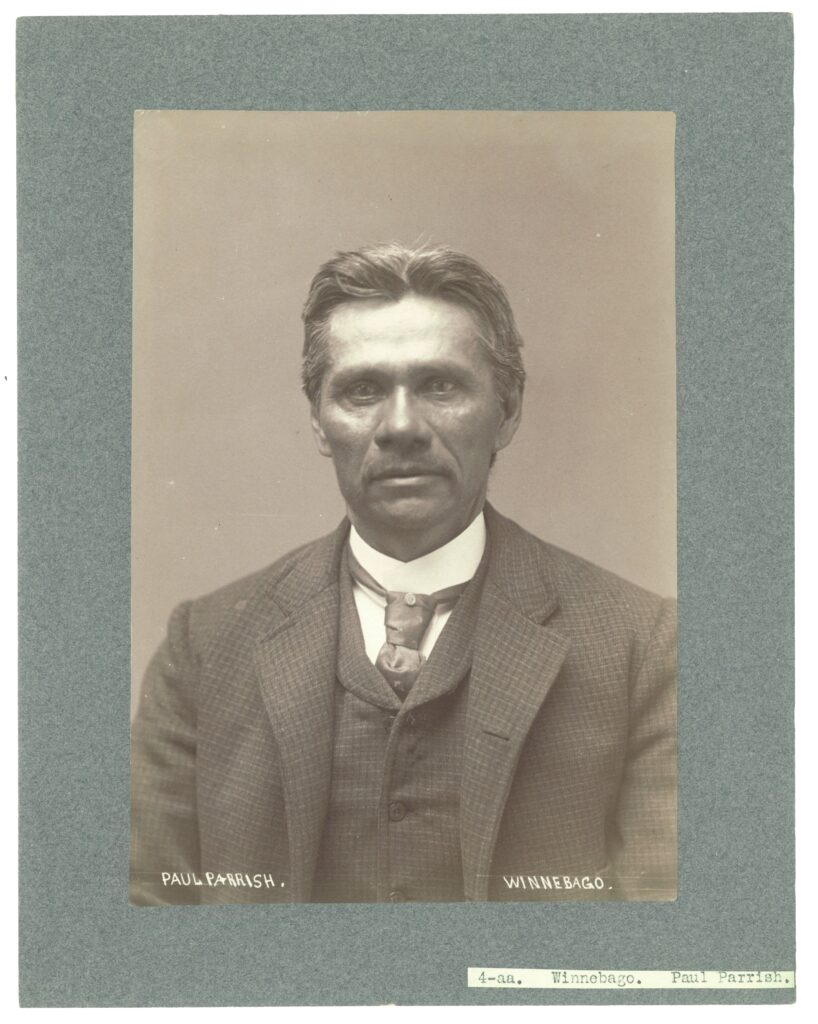

Portraits

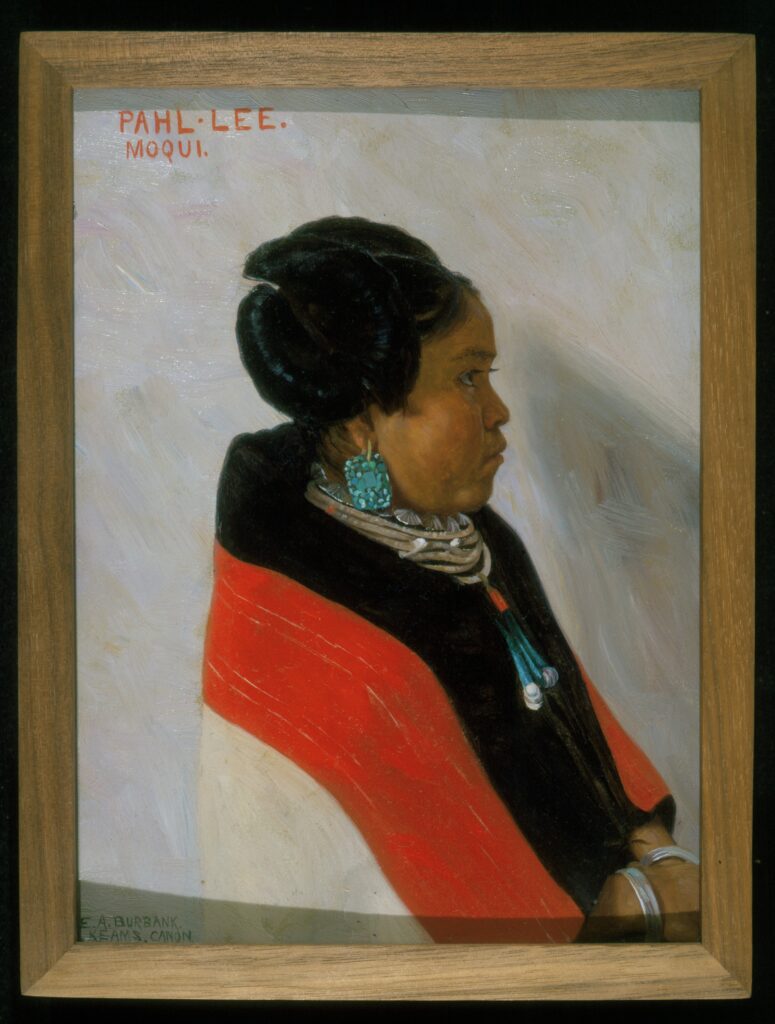

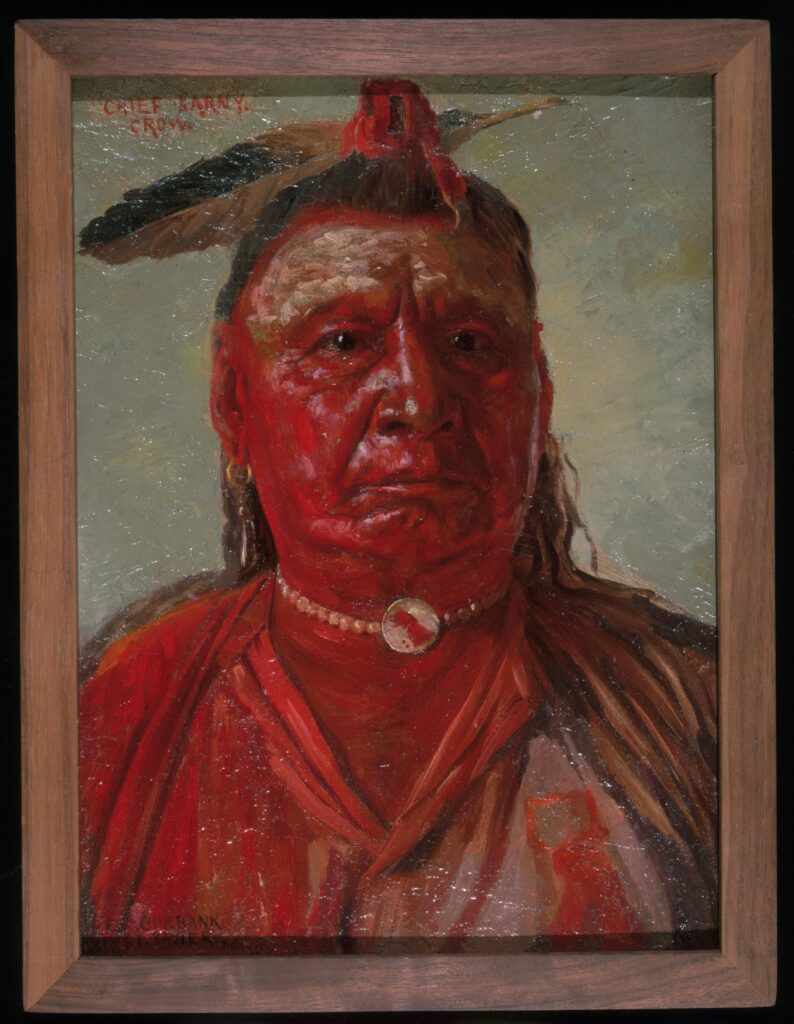

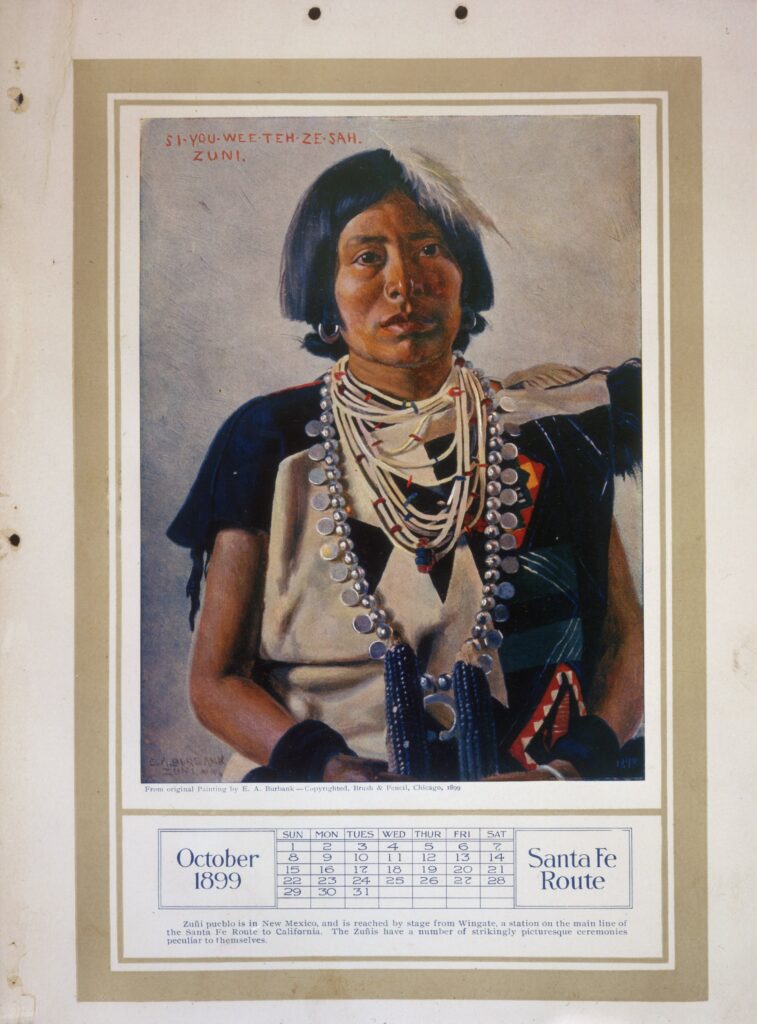

One of the core tenets of frontier mythology in America was the idea of the vanishing Indian. In the early nineteenth century, many Euro-Americans subscribed to the belief that American Indians were disappearing. As settlers pushed further west of the Mississippi River into already inhabited lands, they came into conflict with American Indians. With the efforts to forcibly remove American Indians from desirable lands and on to reservations, and to force assimilation through Indian boarding schools, it seemed to many Americans as if American Indians and their ways of life were “vanishing” both physically and culturally. The concerns over the vanishing Indians influenced artists of the nineteenth century who sought to preserve American Indian ways of life before they disappeared forever.

George Catlin was a self-taught and prolific artist who embarked on multiple trips to the Western United States to create a visual record of American Indians ‘’to rescue from oblivion their primitive looks and customs,’’ which were being ‘’blasted and destroyed by the contemporary vices and dissipations introduced by the immoral part of civilized society.’’ Before the era of photography, the painting and sketches of artists were the only means by which many Euro-Americans had ever seen an American Indian.

Images of American Indians were popular with the American public, so for some artists there was a strong commercial motivation to create these portraits. While artists like Karl Bodmer tried to create accurate representations of American Indians, other artists conceived their works to capitalize the public’s imagination, mixing and matching elements from different tribes to achieve a desired aesthetic. The commercial market reflected and reinforced a particular view of American Indians, and contributed to the image of Plains Indians as representative of all American Indians.

Questions to Consider:

- Select one of the portraits from this section. What do you think the artist wanted to communicate about the subject? Was the subject trying to communicate something about his or herself? What might be important to know about the artist when using this portrait as a source? How does the meaning and purpose of the portrait change when viewed by a twenty-first century audience?

- Select one of the studio portrait photographs and a non-studio photograph from this collection. How do the background and perspective change the information in, or context of, the photograph? Do you think one type of photograph is a more accurate primary source, why or why not?

- In many of these portraits, the sitter is identified. Why might that be important?

- How might these images look different if the creator was American Indian rather than Euro-American?

Museums and Collecting

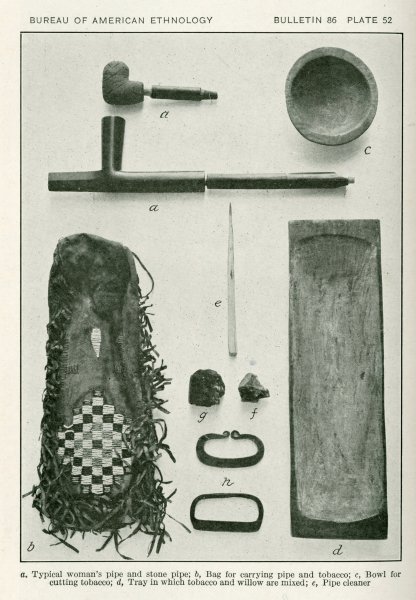

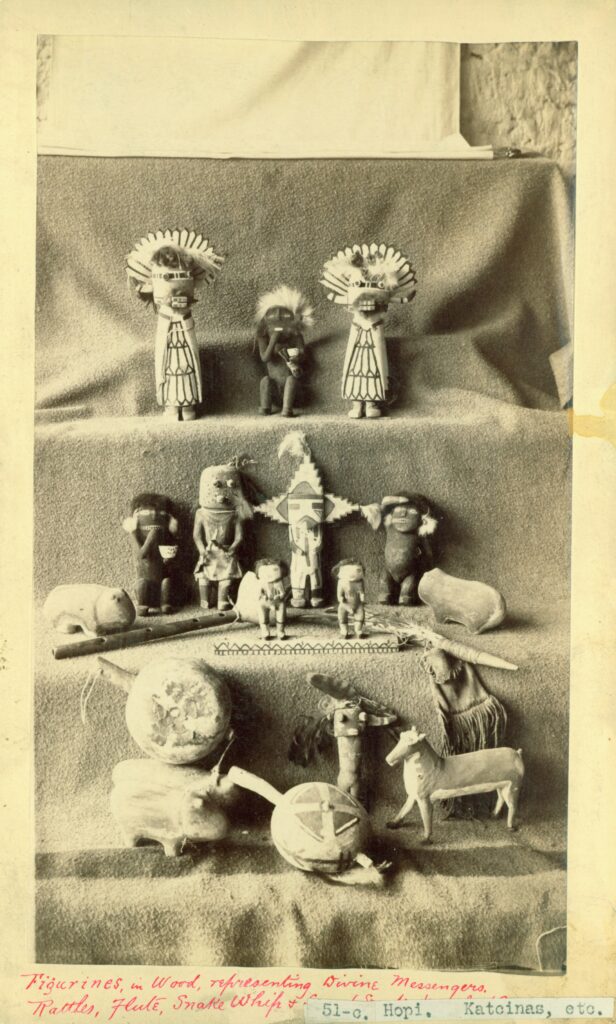

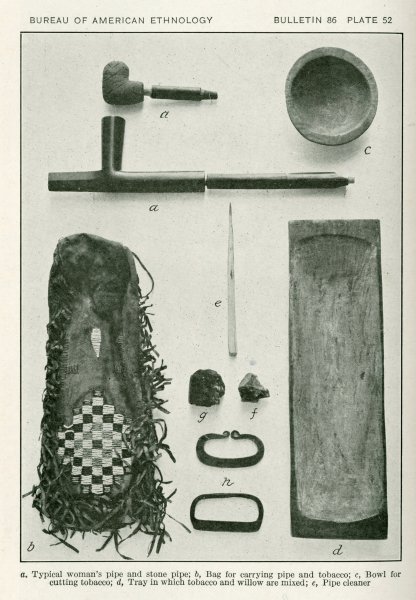

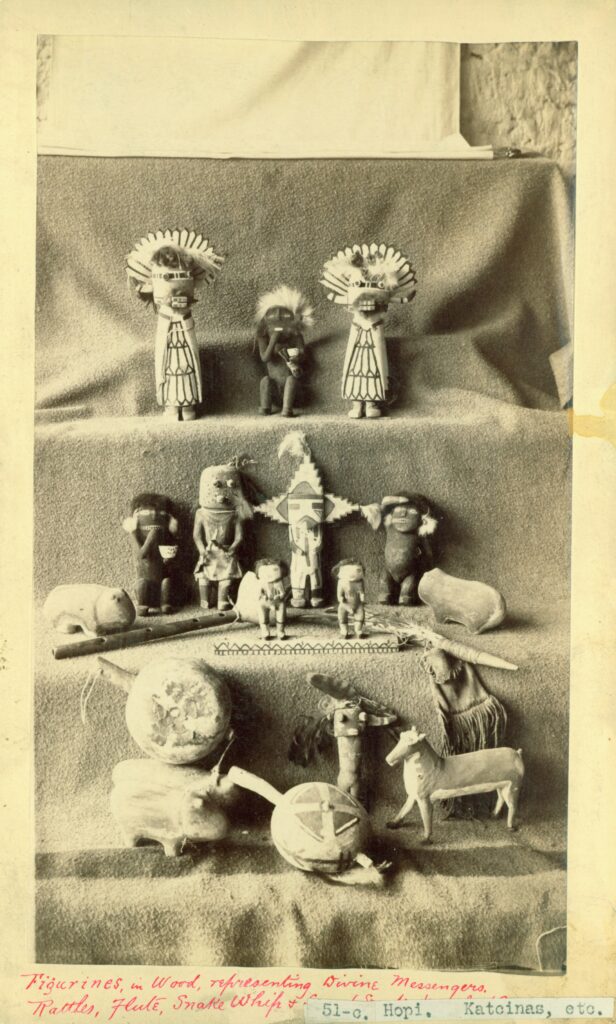

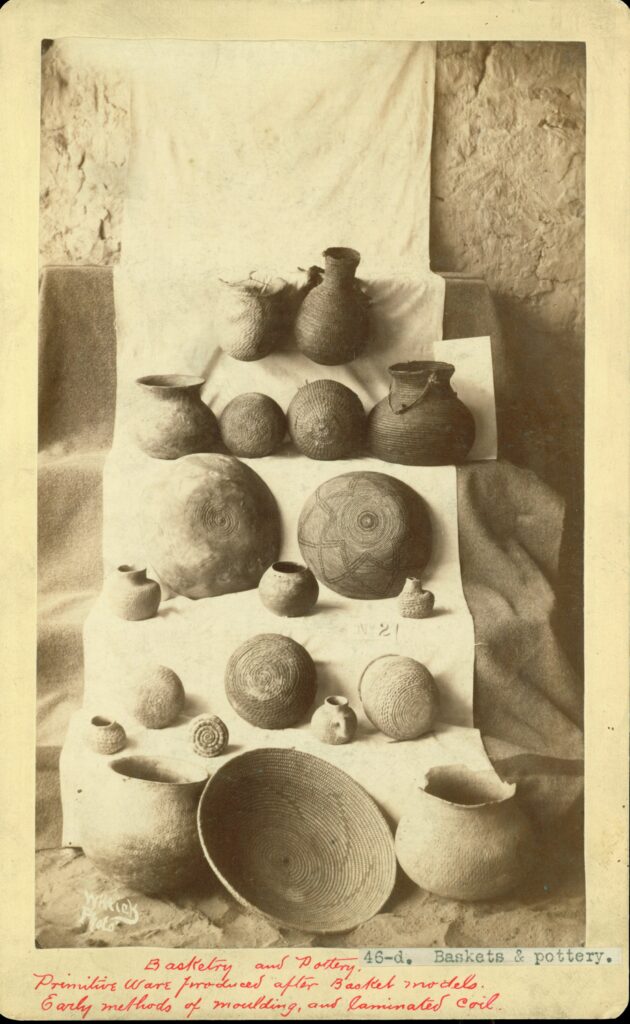

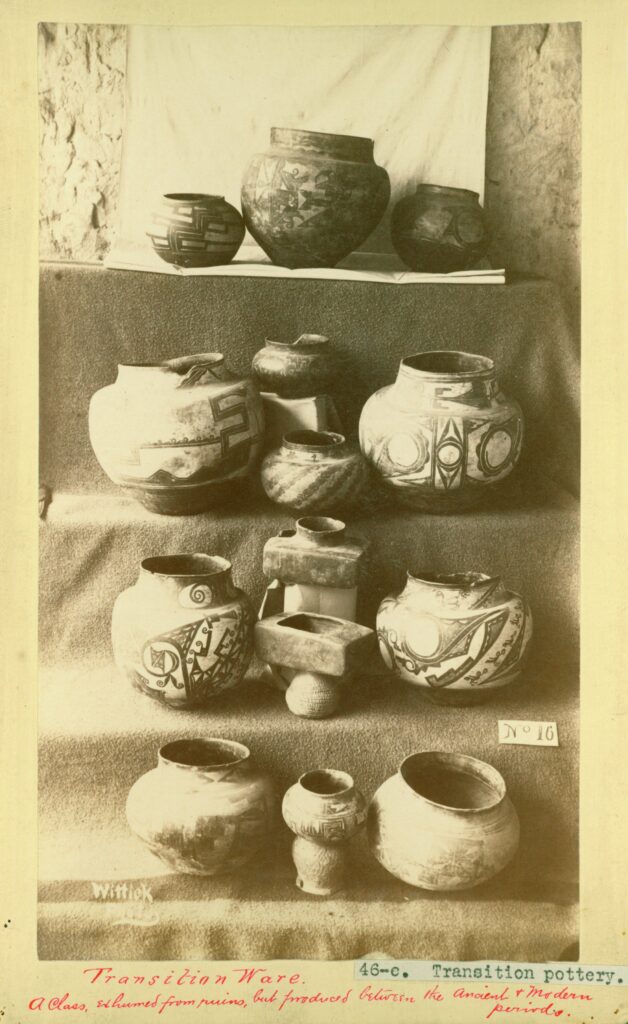

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there was a growing interest in collecting American Indian heritage. Scientists, scholars, and collectors gathered stories, conducted linguistic research, and amassed collections of material items such as baskets, pottery, beadwork, and hide paintings.

American Indian material culture was often displayed in natural science and anthropology museums, rather than art museums. Curators labeled American Indian art, as well as the art of other indigenous peoples from around the globe, as primitive art. The labeling of objects made by American Indians as primitive, and its placement in anthropology museums instead of next to Amerian and European art in art museums, reinforced stereotypes and beliefs about Euro-American superiority.

Museums such as the Field Museum in Chicago and the Smithsonian’s American Bureau of Ethnology participated in collecting and exhibiting American Indian art. Such efforts undertaken by collectors and scholars were intended to preserve American Indians’ past. Ideas about tradition and authenticity guided the collecting strategies of individuals and institutions. Much of the collecting and research frenzy was fueled by a salvage mentality, linked to the myth of the vanishing Indian. Curators and collectors believed that it was critical to save American Indian cultural artifacts for scientific study.

American Indian cultures and traditions have continually changed over time in response to new opportunities and challenges. The collected objects and visual art pieces that formed the basis of these collections are representative of a certain period of American Indian history, a period characterized by an extreme level of conflict and change. However, these objects were typically treated by curators and collectors as defining examples of what is traditional and authentic in American Indian art.

The focus on certain types of objects and styles as authentic excluded other types of American Indian art. While American Indian artists and artistic traditions continued to adapt to a radically different world and explore new forms of artistic expression, the institutional determination of authenticity limited what was collected and exhibited to the public. For anthropologists with a focus on ethnology, American Indian cultures were frozen in time.

Questions to Consider:

- What does the context of displaying American Indian art and artifacts in anthropology and natural science museums indicate about the way Euro-Americans understood and valued these cultures and items?

- How did the preferences of past collectors influence the material and documentary record, and why does that matter to historians in the twenty-first century?

- Look online or in a book for three examples of twenty-first century artwork by American Indian artists. How has American Indian art continued to change, and how is it linked to traditional art forms?

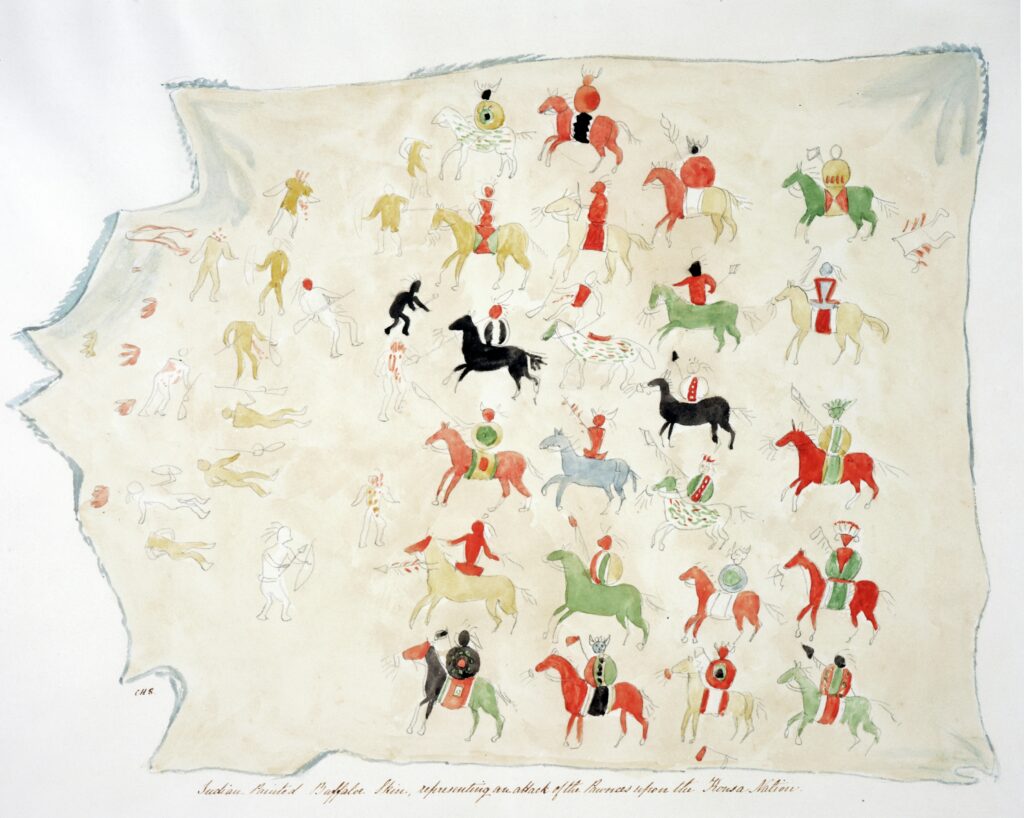

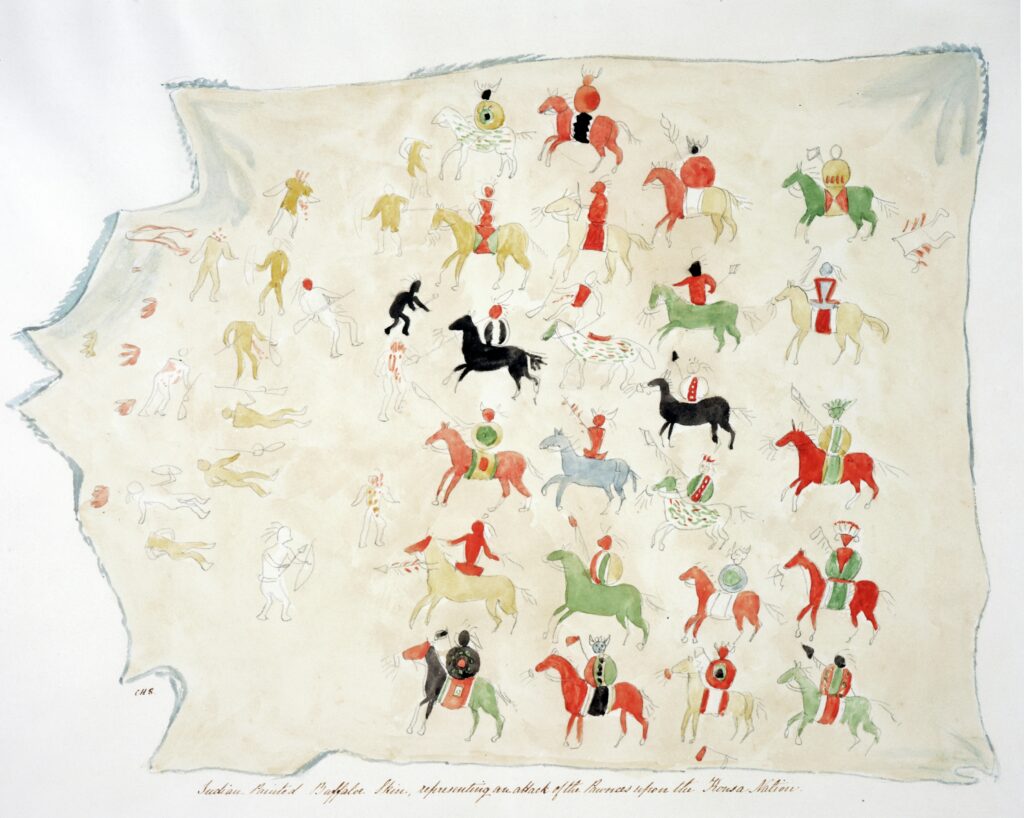

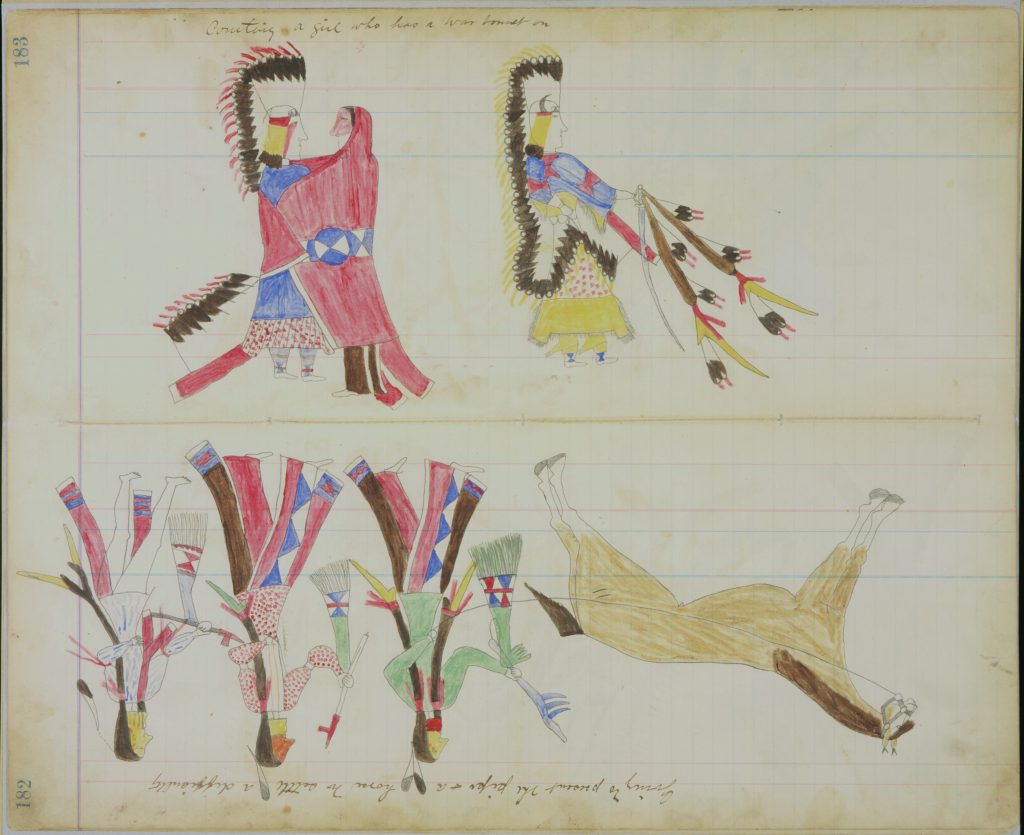

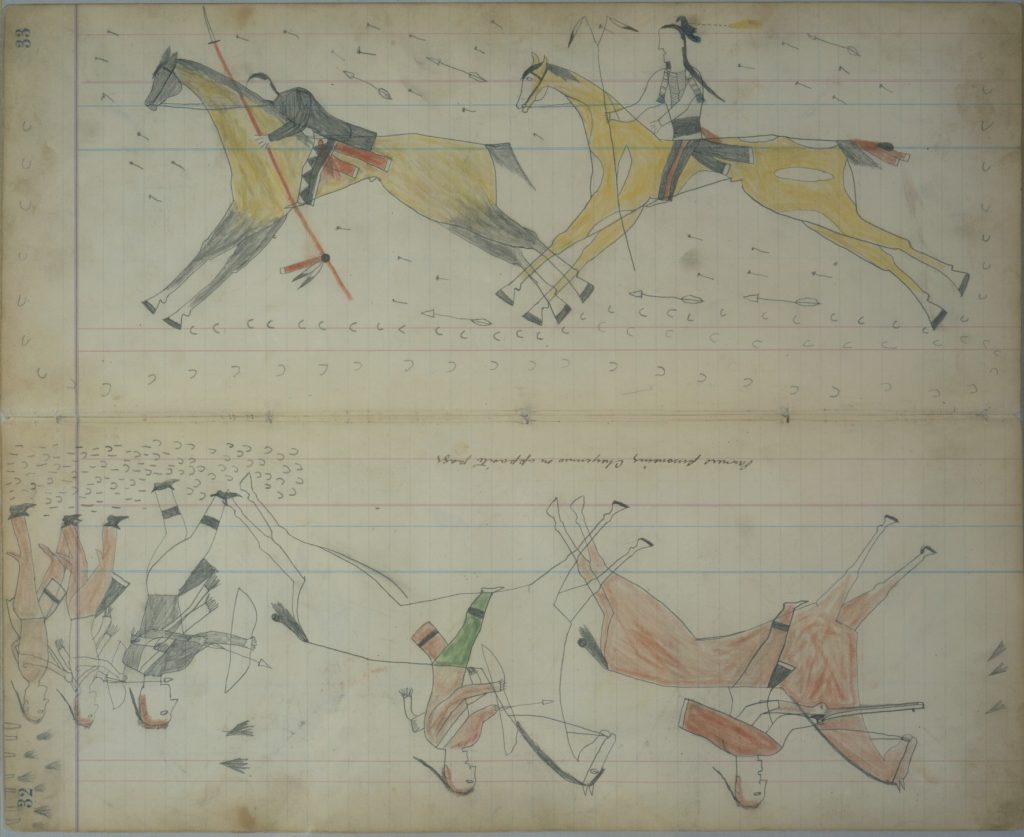

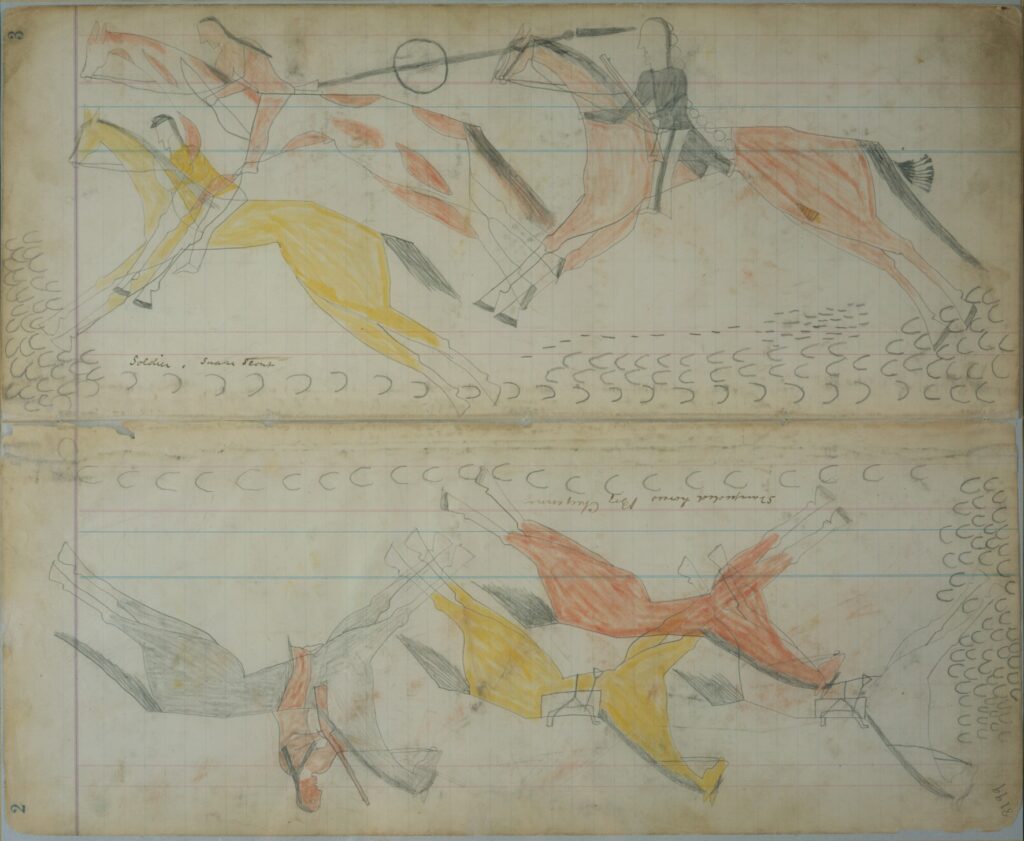

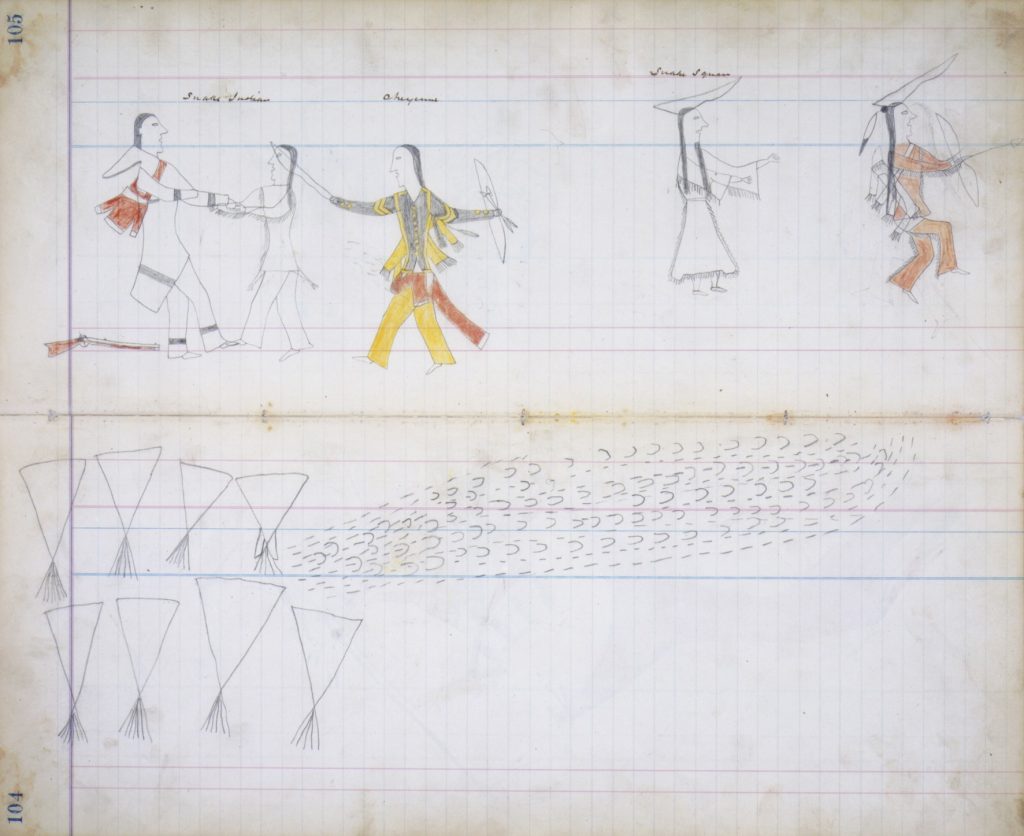

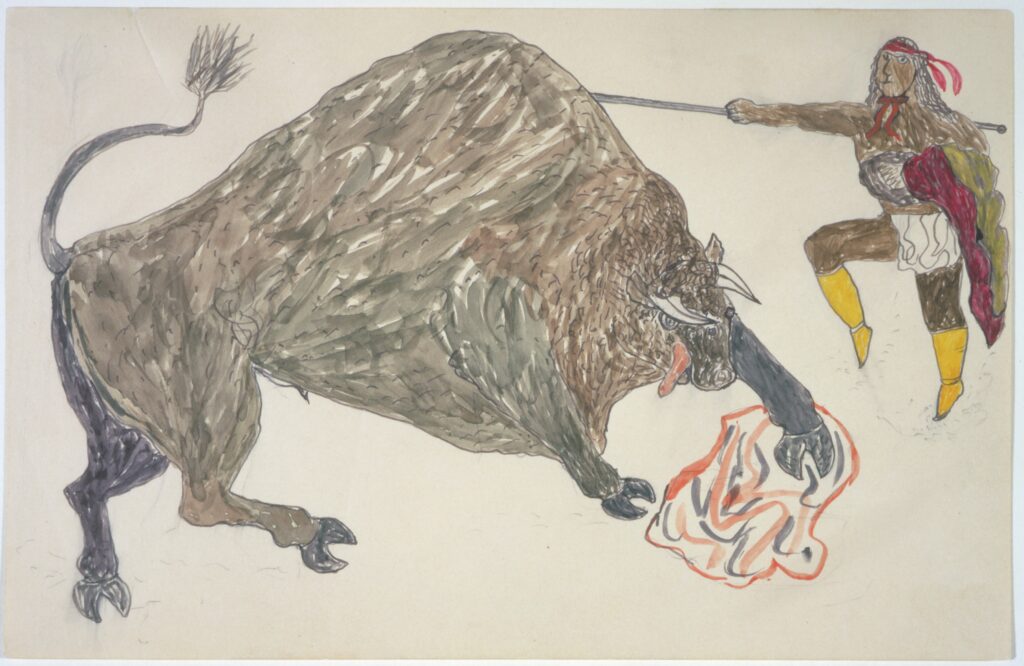

Ledger Art

American Indians created and beautified objects for use in everyday life, and tribes across the Western United States developed their own decorative styles and motifs based on the materials in their environment and in response to external events. American Indians of the Great Plains developed a unique form of narrative art, or artwork that tells a story. Initially, Great Plains tribes recorded stories and histories through visual representation on animal hides. In the second half of the nineteenth century, as availability of animal hides decreased, and American Indians were increasingly confined to reservations, a new genre of artwork developed: ledger art. Ledger books are accounting books, and Plains Indians began recording their stories in these ledger books. Exchanging hides for paper resulted in changes to the art form as the paper of ledger books provided a smaller surface than an animal hide, and the artist could no longer tell the entire story on a single surface. The materials used to create images on paper were different from the tools used to illustrate animal hides; artists used supplies like pencils and crayons to create their ledger book artworks.

Selection: Black Horse Ledger (1877)

Ledger art was largely created by male artists who illustrated events such as battle scenes and heroic exploits, but as more American Indians were confined to reservations, scenes from everyday life before the reservation entered into the genre. Some of the best-known ledger art was created by American Indian prisoners held at Fort Marion in Florida. Because of the focus on story-telling, there is often no background in ledger art unless it provides important information for the story. Some pieces of ledger art have notations and alterations that were not made by the original artist, so care must be taken when interpreting ledger art.

Questions to Consider:

- How does ledger art use visual cues to tell a story? Which elements of the drawings appear realistic, and which elements appear symbolic?

- Compare the illustration of buffalo hide artwork with a piece of ledger art. What similarities and differences do you notice? How do the materials impact the style?

- What are the challenges of using these artworks as primary sources? What kind of information might these sources offer that would be unavailable otherwise?

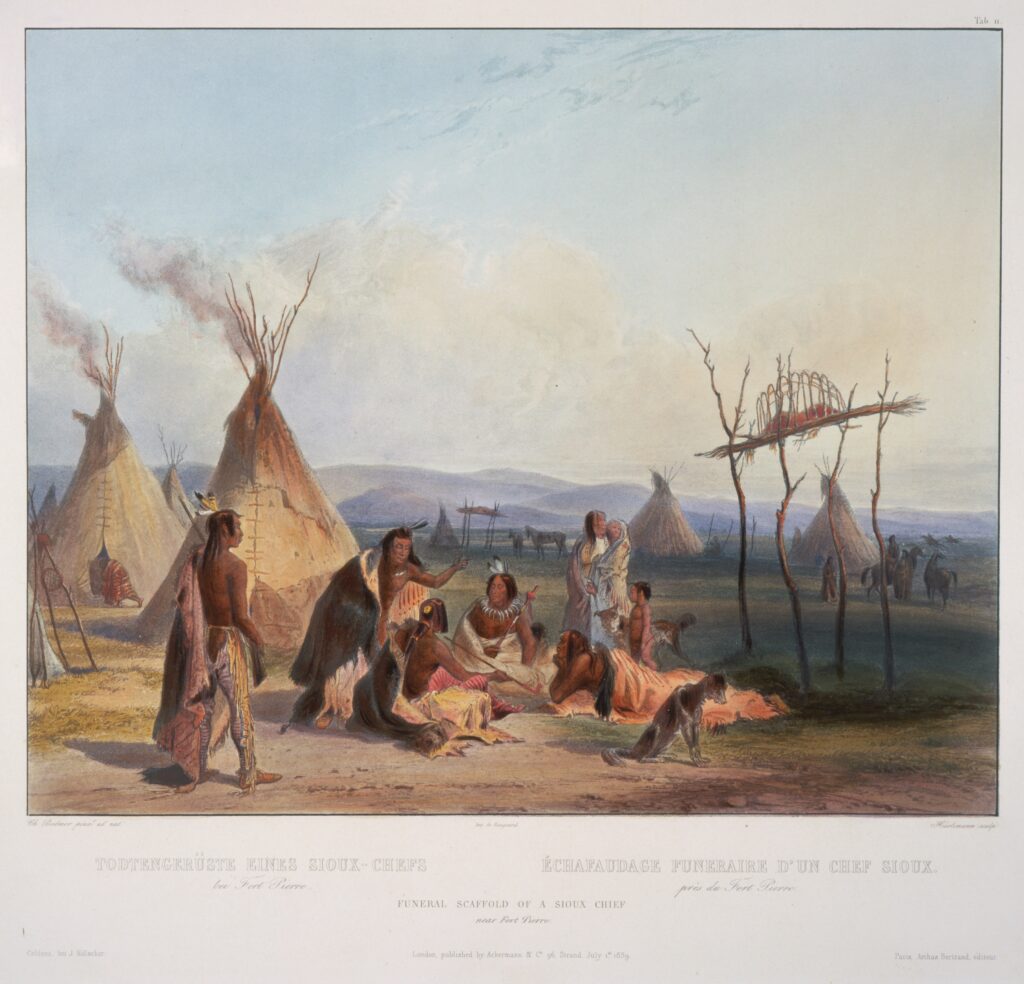

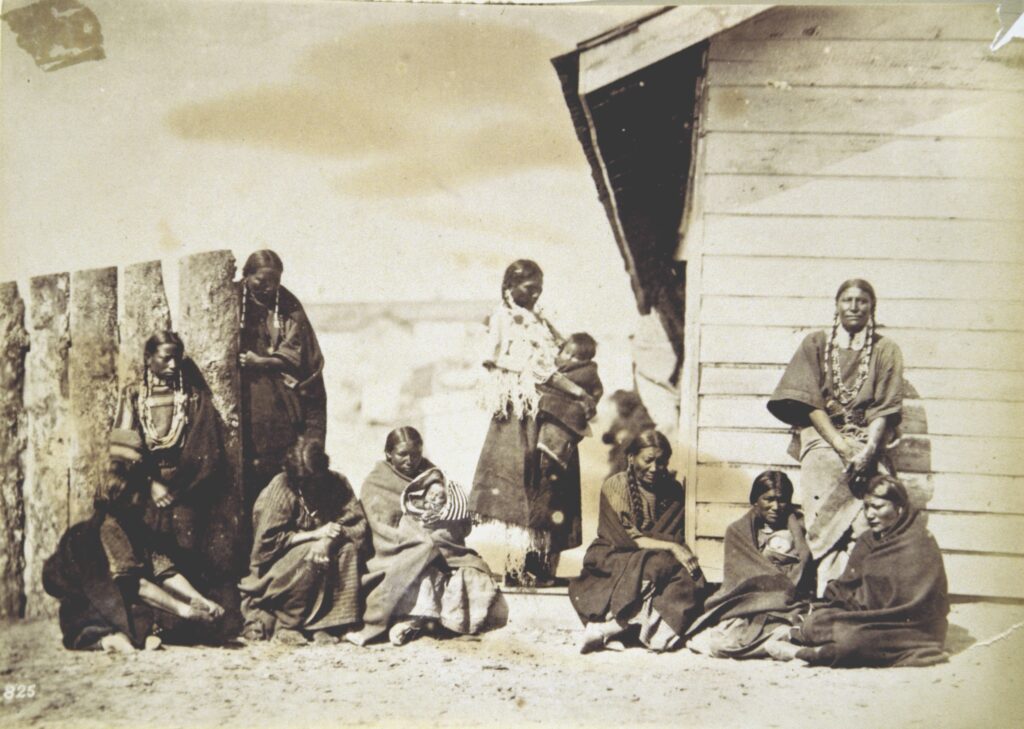

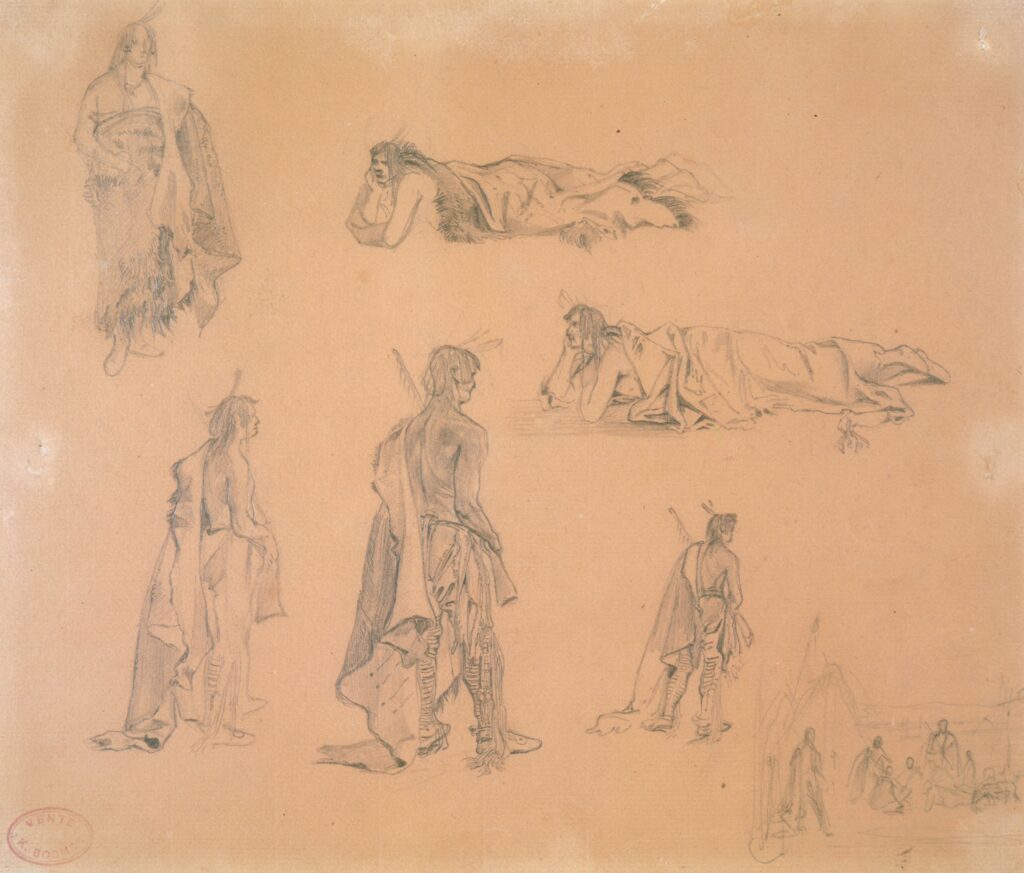

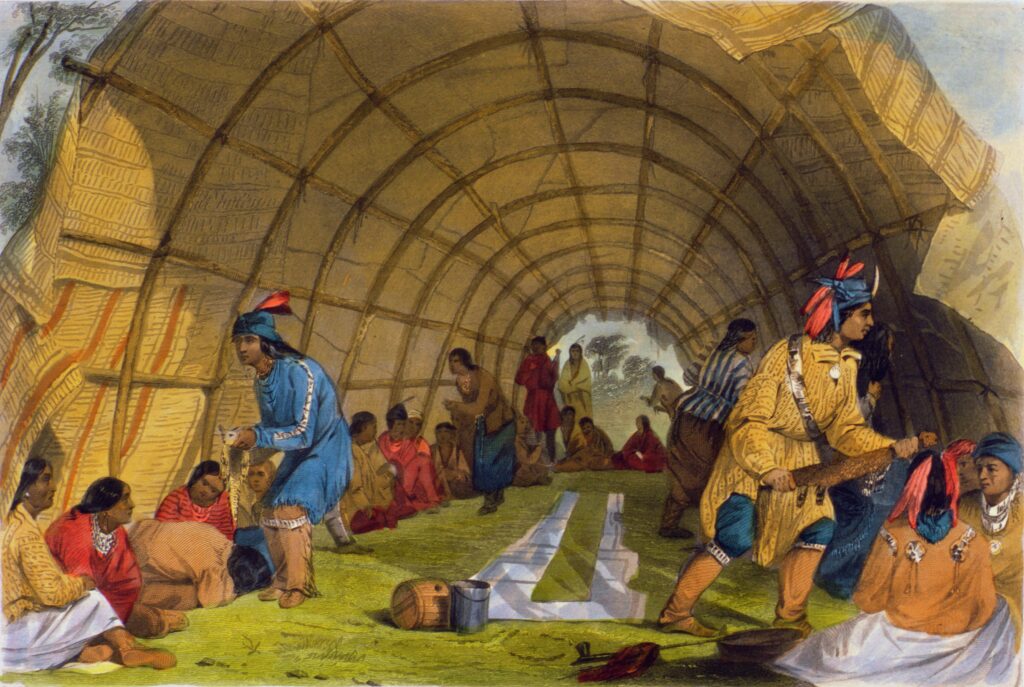

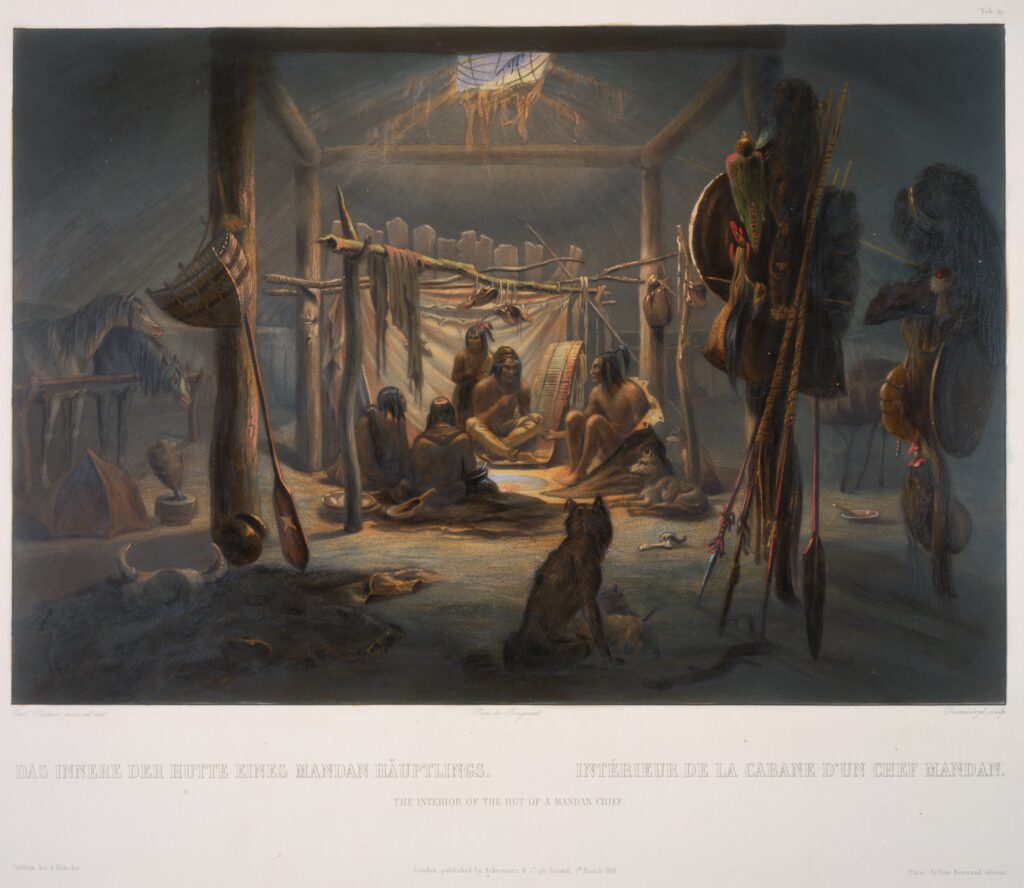

Daily Life

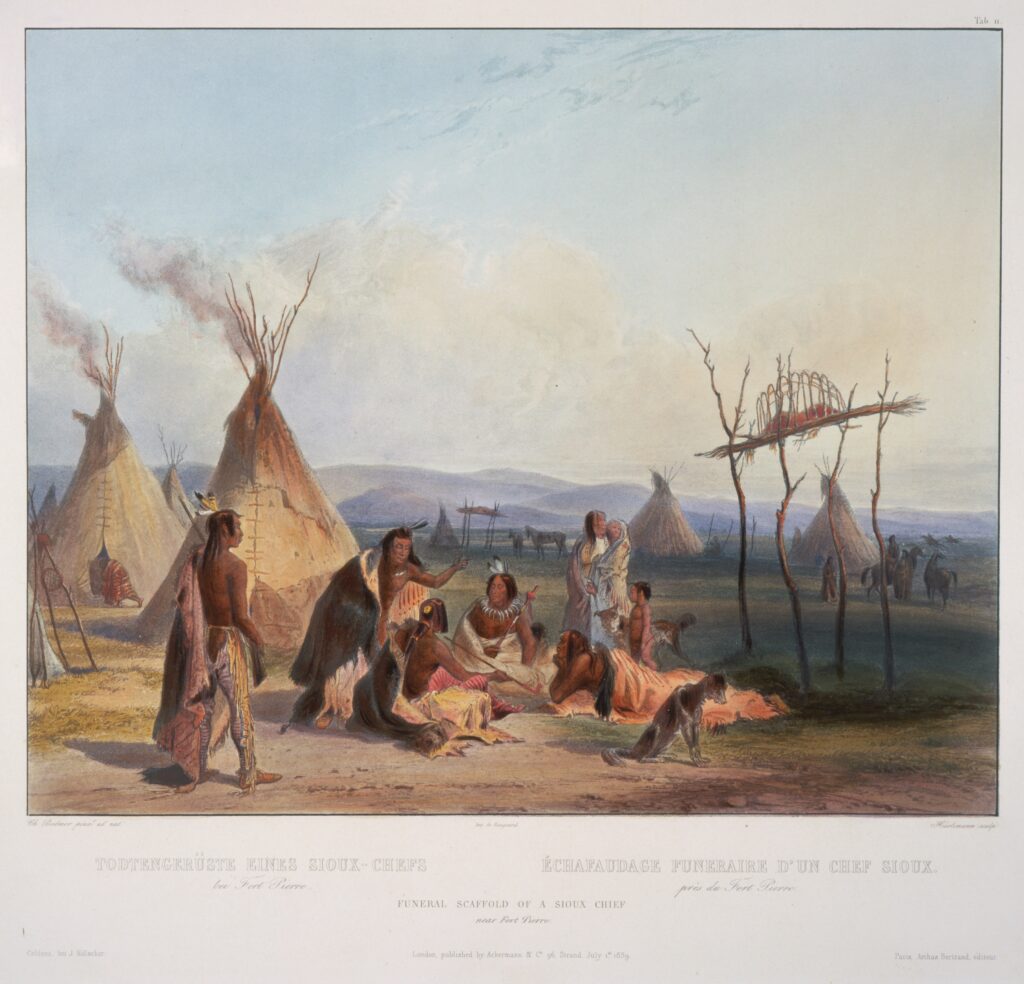

The artworks in this section are illustrations by Euro-American artists and photographers of everyday life among different groups of American Indians, a popular theme explored by non-indigenous artists. Karl Bodmer was a Swiss artist known for his detailed depictions of landscapes and indigenous peoples in the nineteenth century American West. In the 1830s, Bodmer accompanied the Prussian Prince Alexander Maximillian on his travels thought the American West as an illustrator for Maximillian’s atlas of his travels, Travels in the Interior of North America 1832-1834. Bodmer created sketches and watercolors that were engraved and printed upon his return to Europe. In the winter of 1833-34, Bodmer and Maximillian spent several months with the Mandan in present day North Dakota. Not five years later, the Mandan were decimated by small pox. Bodmer’s illustrations from travels in the Upper Mississippi provide a glimpse into American Indian life before widespread Euro-American settlement of the West.

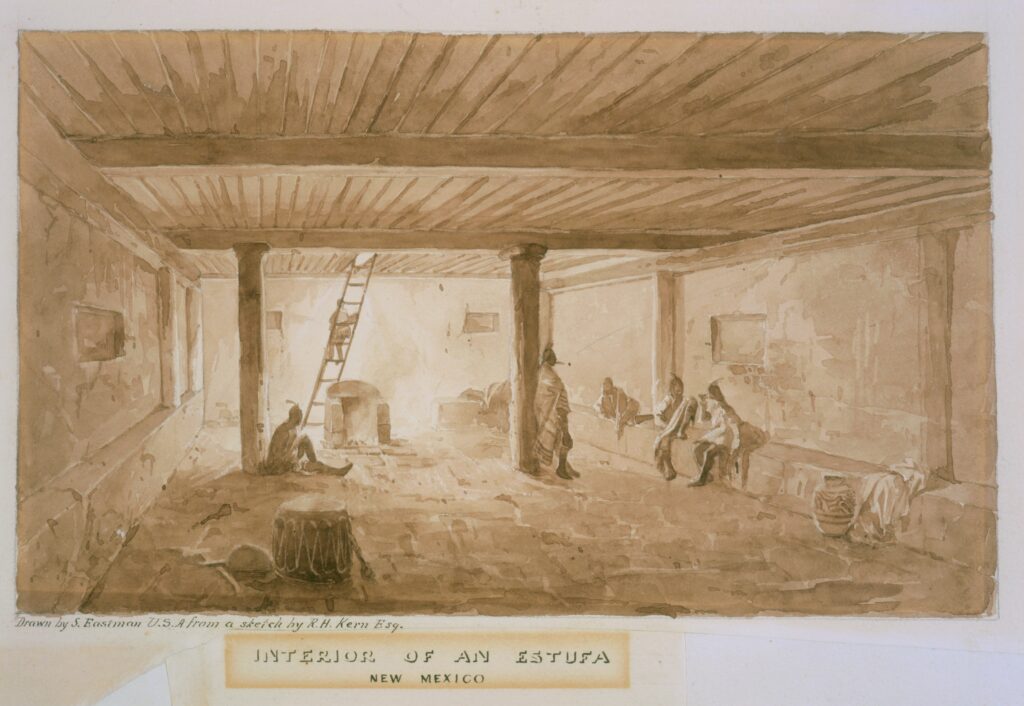

Seth Eastman, a soldier in the United States Army created hundreds of illustrations of American Indian life in the mid-nineteenth century. Unlike some artists, who hurriedly captured images before returning to their studios in the East, Eastman spent considerable time living in the West where he illustrated scenes from everyday life from several tribes of the Great Plains region. Many of these works were ultimately published in a government-funded six-volume work, Information Regarding the History, Conditions, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States. The range of Eastman’s images offers insights into daily life, and hints at the cultural diversity of American Indians.

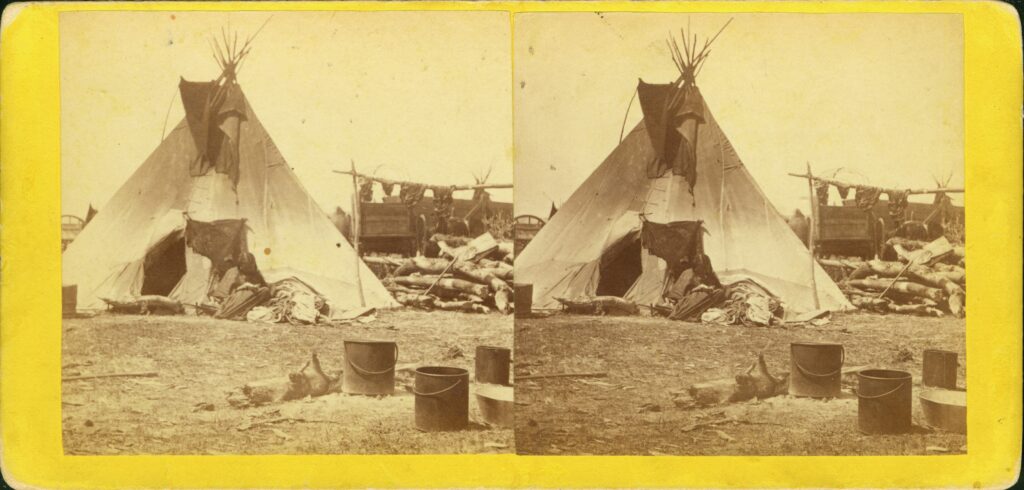

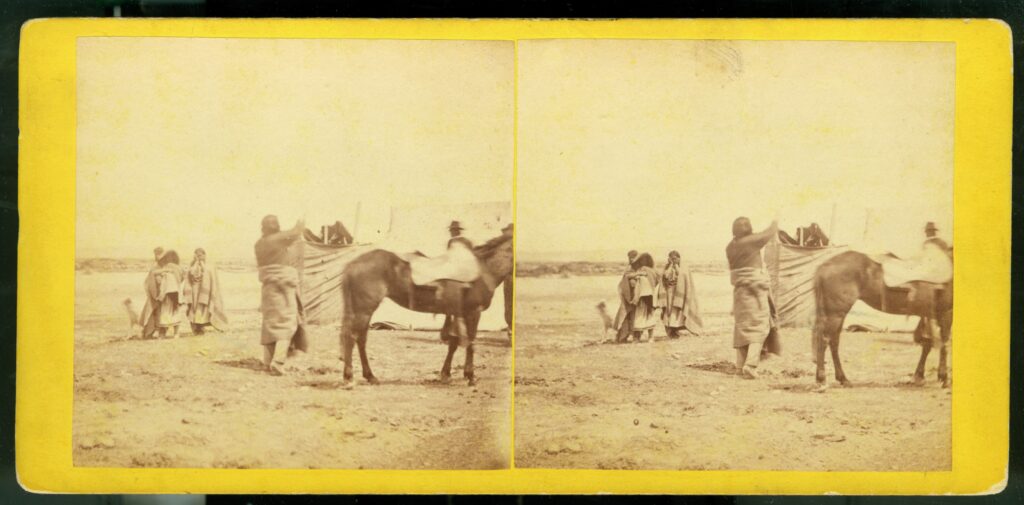

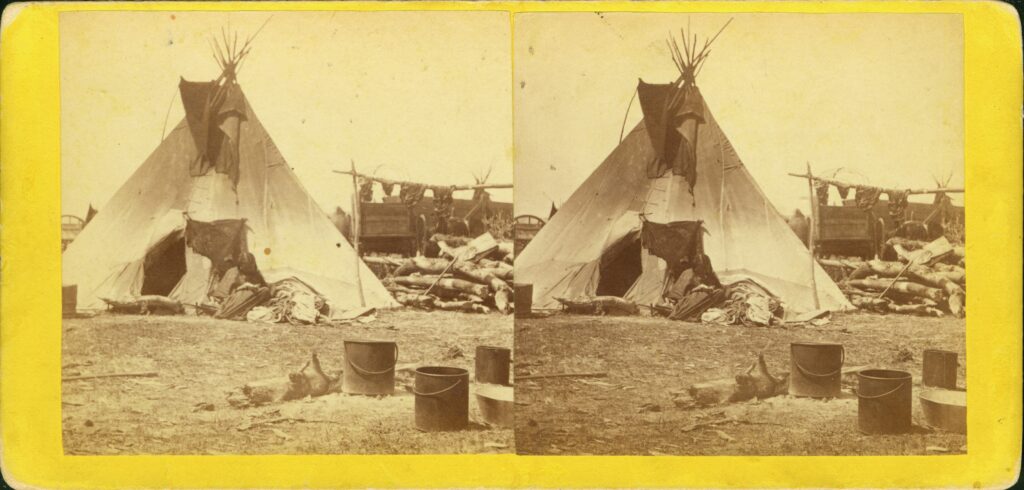

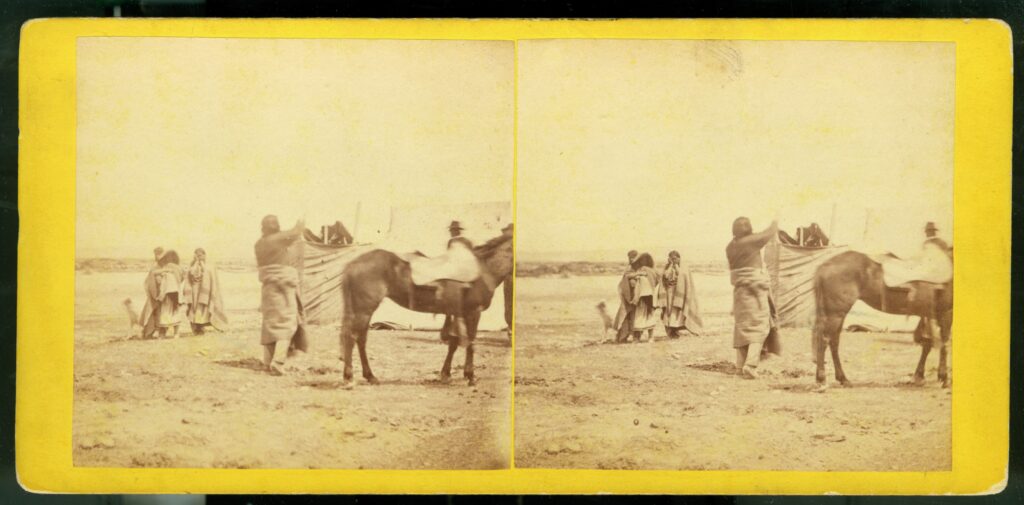

In addition to artists like Seth Eastman and Karl Bodmer, photographers also endeavored to record American Indian life. Photographs with two side-by-side duplicate images are stereographs. When the images are viewed through a stereoscope, the images appear three dimensional. Stereographs added an element of realism to the photographs, and were accessible to people at all levels of society. American Indians and images of the West and faraway lands were popular choices for stereographs.

Questions to Consider

- What kinds of scenes and images are represented by these artists? Who is the intended audience for these artworks? How might the intended audience have influenced the selection and creation of images?

- How did images like these inform Euro-American perceptions of American Indians?

- Look at Bodmer’s funeral images. What can these documents illustrate about the process of creating a final printed product? What challenges might Bodmer and other artists have faced in recording these images?

- What are the challenges of using these artworks as primary sources? What kind of information might these sources offer that would be unavailable otherwise?

American Indian Artists in the Southwest

What makes a piece of art traditional? Is it the designs and motifs, the method of creation, the materials used? While rooted in various traditions, American Indian artists have adapted artistic traditions, explored new media and techniques, and influenced the art world.

Frederick Gokliz was a Chiricahua Apache artist from the San Carlos Indian Reservation in Arizona. Gokliz, along with other Chiricahua Apache, was moved to Fort Marion in Florida as a prisoner of war, and he ended up in Fort Sill in Oklahoma. Historians believe these drawings were created in the 1890s.

Awa Tsireh, who also went by the name Alfono Roybal, was a Southwestern artist with a national reputation for his richly-colored watercolor paintings depicting Pueblo life and culture. Tsireh’s paintings reflect not only his own pueblo, San Ildefonso Pueblo, but also those of nearby tribes such as the Hopi and Navajo. Tsireh’s work features flat figures with no background, and they were primarily created for non-indigenous audiences. The colorful and detailed paintings also served as a form of activism. In the 1920s, the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs attempted to suppress American Indian dances, especially those of the Pueblo. The captivating images painted by Tsireh not only captured the ceremonies and dances in exquisite detail, but also created an interest in Pueblo culture among a broader audience. Tsireh’s watercolors were largely created for a Euro-American audience, including patrons and collectors, and the watercolors were exhibited across the United States. In the 1920s, the Newberry in Chicago hosted an exhibition of Tsireh’s work.

Tsireh’s work has been identified as culturally sensitive and removed. Learn more about the Newberry’s policy on Access to Culturally Sensitive Indigenous Materials here.

Questions to Consider:

- What subjects and scenes are represented in these pieces of art?

- How does Gokliz make use of colors and patterns in these works?

- How does Gokliz illustrate movement and relationships through his drawings?

- How do you think the intended audience influenced each man’s work?

- Compare Gokliz’s Two Men in Costume and one of Tsireh’s watercolors. What similarities or differences in colors, style, and materials do you notice?

- What other art traditions do Tsireh’s paintings remind you of?

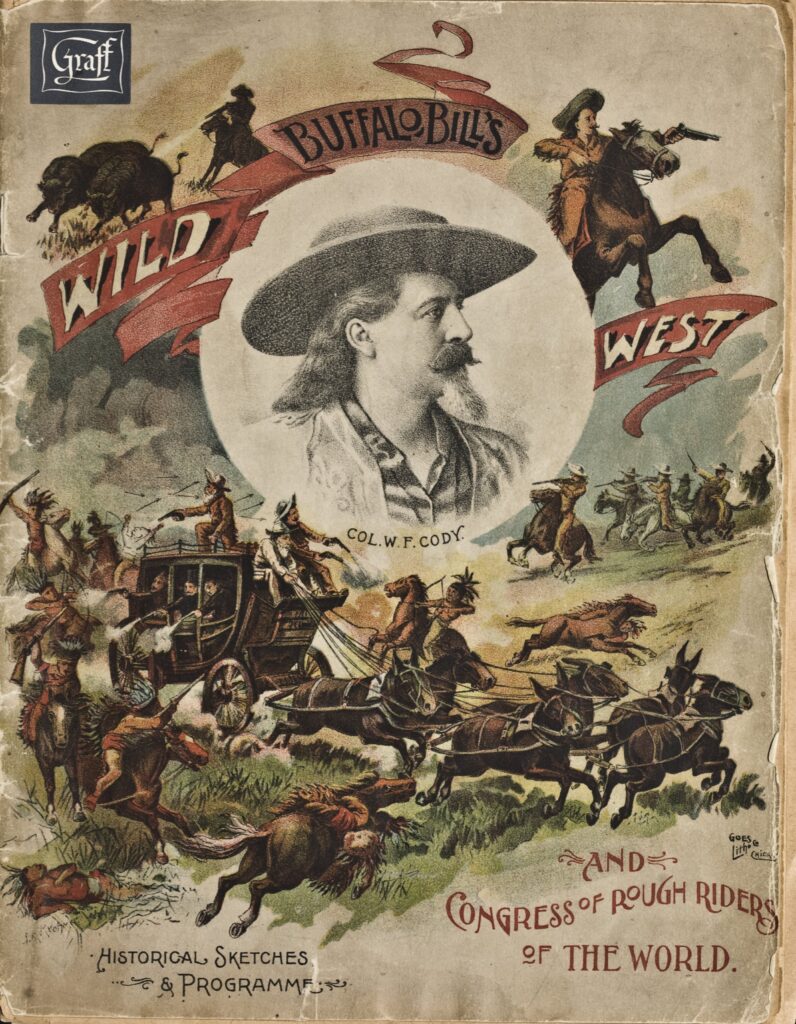

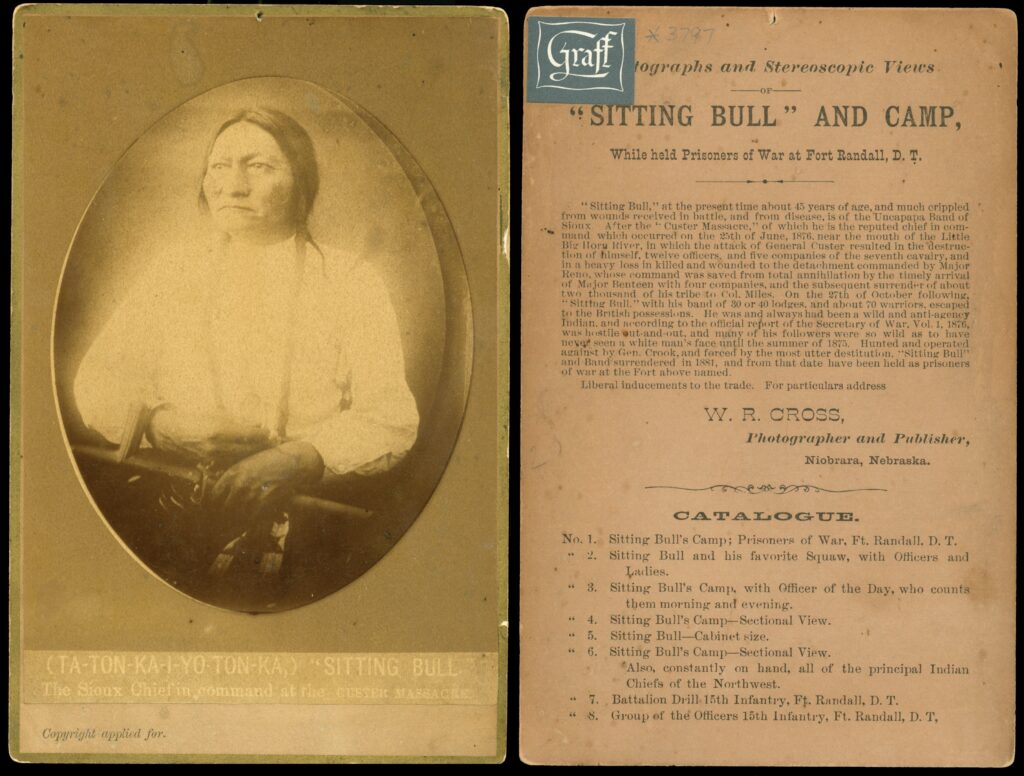

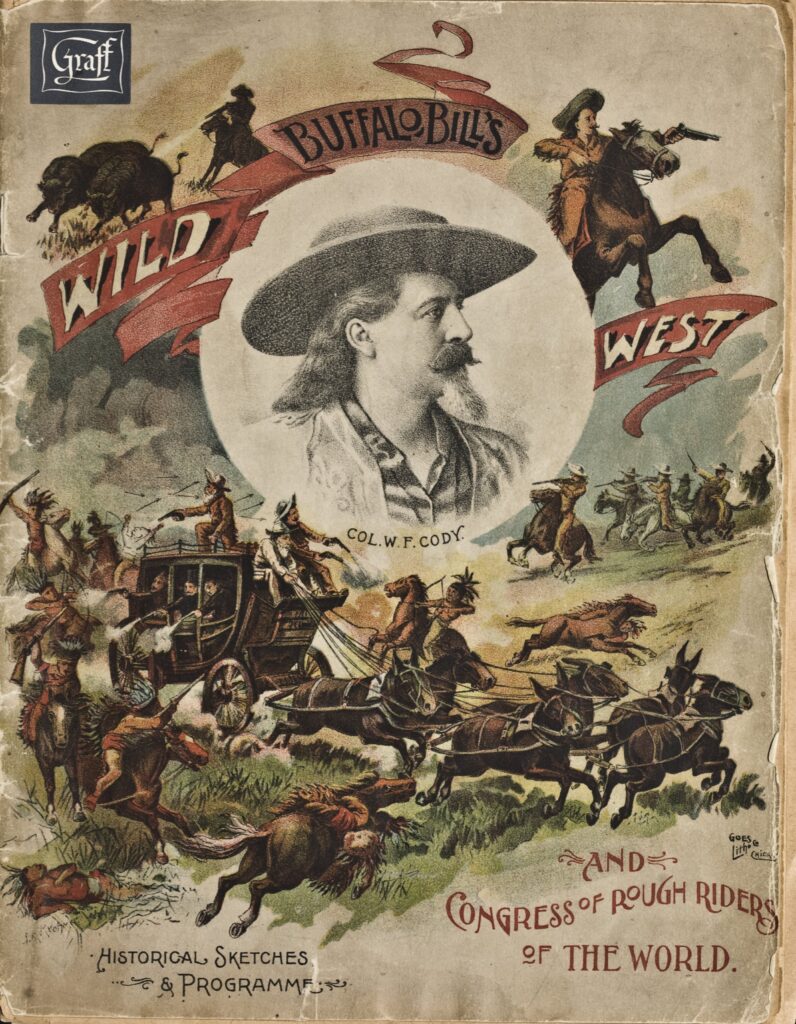

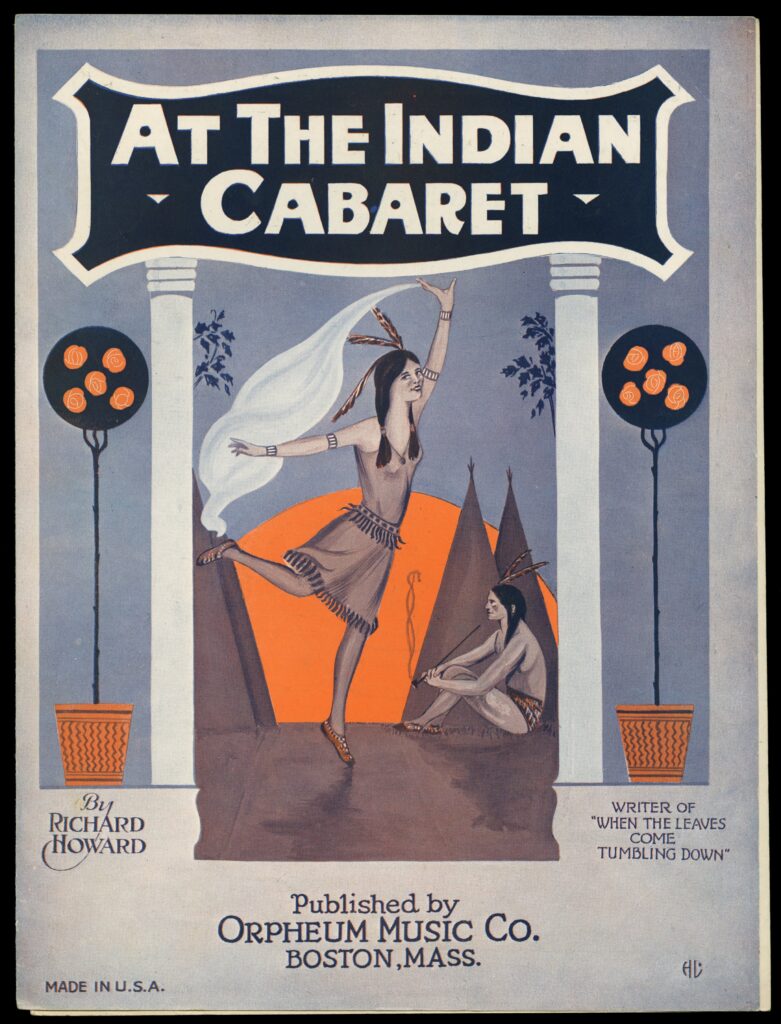

Representation of American Indians in Popular culture

These documents look at representations of American Indians in popular culture in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. At the end of the nineteenth century, the decades of armed conflict in the West between American Indians and the United States government and its settlers came to a close. By the end of the Indian Wars, American Indians who had lived across the West were confined to reservations, held as prisoners of war, or assimilated into local communities.

Decades of Indian Wars in the West contributed to the blurring of distinctions between American Indian cultures. In spite of the rich cultural, historical, artistic, and linguistic diversity among American Indians, for many nineteenth century Euro-Americans, stylized images of Plains Indians warriors became a stand-in for all American Indians. Cultural phenomena such as Buffalo Bill’s immensely popular Wild West show offered audiences a dramatic and romanticized version of the West. The Wild West show employed American Indian performers for theatrical reenactments of events like the Battle of Little Big Horn. For many attendees, these performances further cemented the limited idea of the American Indians of the Great Plains as the visual representation of all American Indians.

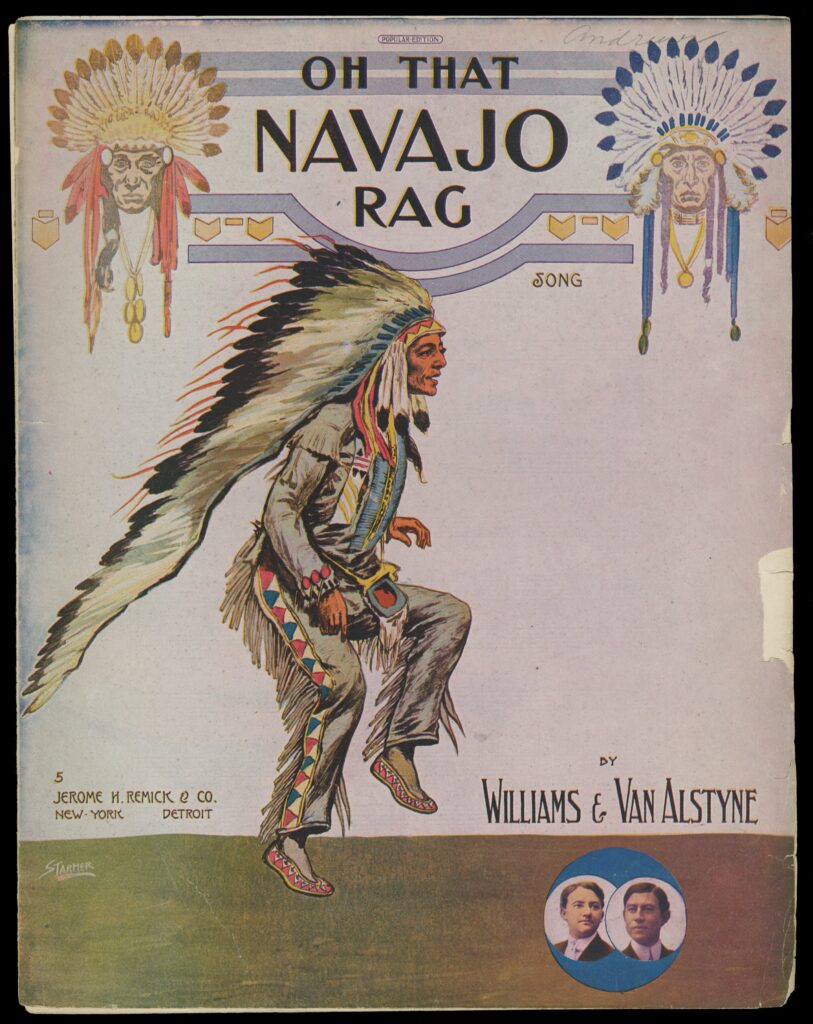

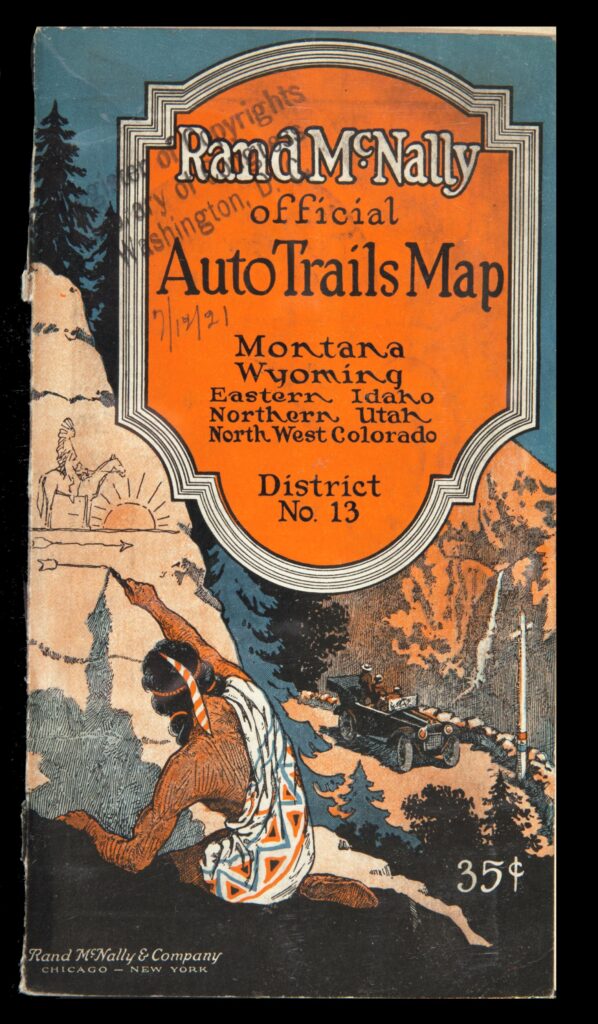

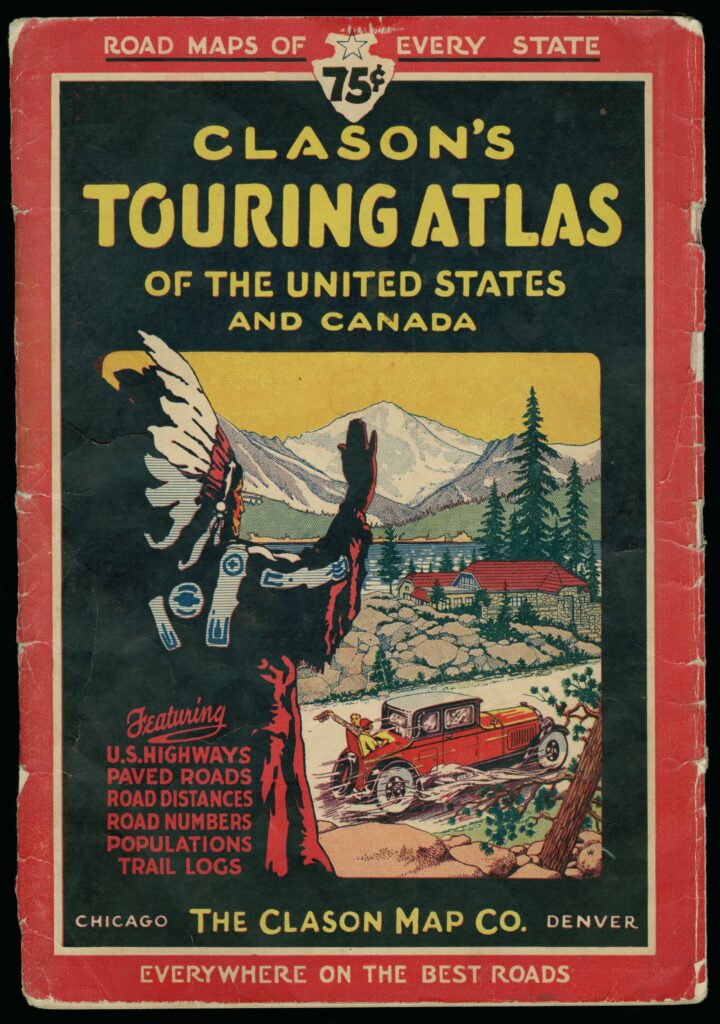

At the close of the nineteenth century, in spite of efforts to remove, contain, and assimilate American Indians, the American public remained fascinated with them. Stylized and stereotypical images of American Indians appeared on products from food packaging to sheet music to road maps.

Questions to Consider:

- How are American Indians represented in these documents? Are there changes over time? If so, what historical shifts would account for the difference?

- How are male and female American Indians depicted?

- What everyday products today include images of American Indians, and how are American Indians portrayed?

Further Reading

Bol, Marsha. “The Early Years of Native American Art History: The Politics of Scholarship and Collecting.” Museum Anthropology 17 (1986–87).

“Keeping History: Plains Indians Ledger Drawings.” Smithsonian, National Museum of American History. 2009. http://americanhistory.si.edu/documentsgallery/exhibitions/ledger_drawing_1.html

Wood, W.R., Karl Bodmer, Joseph C. Porter, and David C. Hunt. “Karl Bodmer’s Studio Art: The Newberry Library Bodmer Collection.” Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002.

Related Newberry Resources

A custom curriculum hosted by the Newberry and centered on Chicago as a Native Place.

Created in alignment with Illinois State Standards and to support the HB1633 mandate to teach Native history.