Introduction

Prohibition evokes vivid images from fiction and history: wild parties from The Great Gatsby, the Valentine’s Day gangland murders in Chicago, or presidential candidate Herbert Hoover’s 1928 comment, when he called Prohibition a “great social and economic experiment, noble in motive and far reaching in purpose.” That phrase was nicely judged to reflect his cautious evaluation of a law that had, since the beginning of the decade, polarized Americans. Hoover’s description and these images evoke aspects of Prohibition and the 1920s. But they also stand as isolated events, unmoored from the social and political context of the era. How can Prohibition be more firmly integrated into the period’s historical narrative? One way is to consider its long-term consequences, as historians Lisa McGirr and Michael Lerner have done recently.

By shifting focus from gangsters to the officers who pursued and punished them, we can see that the legacies of Prohibition included an expanded police force, targeted and selective enforcement, and a larger penal system. We can also take a closer look at what flappers, young women who flouted traditional, restrictive standards of female behavior, achieved. Their cultural revolt made possible a larger political rebellion by mainly middle and upper-class women that ended the period’s gendered political alignment that assumed women, as a voting bloc, opposed alcohol. Finally, when we examine the urban electorate that coalesced against the Eighteenth Amendment in urban centers like Chicago, we can see how that political development connected to the New Deal that followed it.

What caused Prohibition and passage of the Eighteenth Amendment? A contemporary political analysis of the 1928 election, which observers largely understood as a referendum on Prohibition, quoted a US senator who quipped that Americans “voted dry and drank wet.” It was an observation that summarized the contradiction within American alcohol policy in the 1920s. How did such a situation develop?

When Congress passed wartime Prohibition in 1917, and then the Eighteenth Amendment in 1919, organizations like the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) had been intensively educating Americans about temperance and warning them about drinking for more than a generation. A disciplined and coordinated political organization, the Anti-Saloon League (ASL), had fully extended its influence nationwide. By 1912 the ASL had pushed its “local option” strategy–the idea that alcohol policy decisions were left to local voters–as far as it could. Where the ASL could win dry territory in the states, it had done so; most of the Old South and the West were dry and much of the West. In Missouri, for example, 97 of its 115 counties were dry under local option by 1912. The general popular opinion was that temperance was a social and public good. At the same time, however, alcohol consumption rose between 1900 and 1906 for the first time in 30 years, from 16 gallons of beer per capita to 21 gallons, and per capita consumption of spirits rose to their highest levels since the 1840s. These higher drinking rates remained through the next decade. The increase in consumption accompanied changes in drinking patterns as well. Both middle and working class women began to drink more and in public, and overall, there were more moderate drinkers.

When people were drinking more and the temperance movement seemed to have reached its limit, the United States entered World War I. In a frenzy of wartime enthusiasm for sacrifice, and for food and fuel conservation, Congress passed a national wartime Prohibition law in 1917. A well-organized and -financed Anti-Saloon League pressed its advantage and submitted an amendment to the Constitution for prohibition later that year. It quickly passed and was sent to the states for ratification, which was completed by January 1919. Prohibition went into effect one year later.

Essential Questions:

- What caused Prohibition and passage of the Eighteenth Amendment?

- What are the legacies of Prohibition?

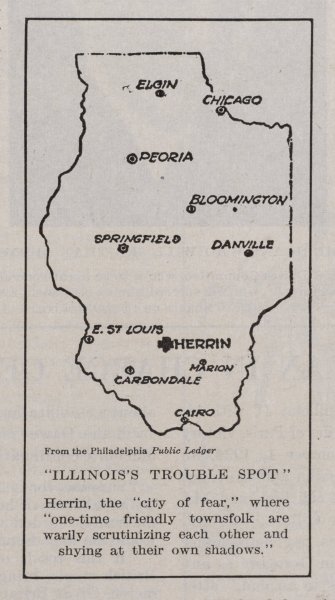

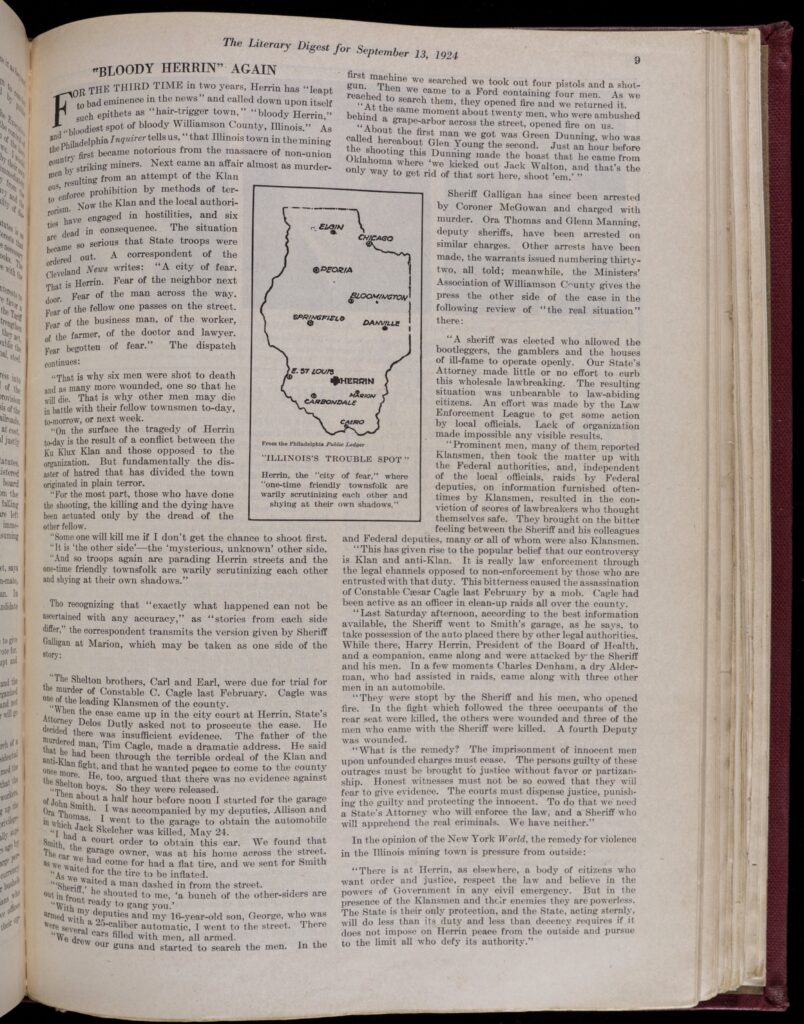

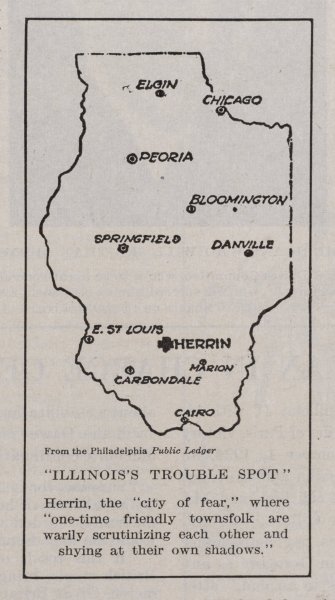

Perils of Enforcement: The Example of Herrin, Williamson County, Illinois

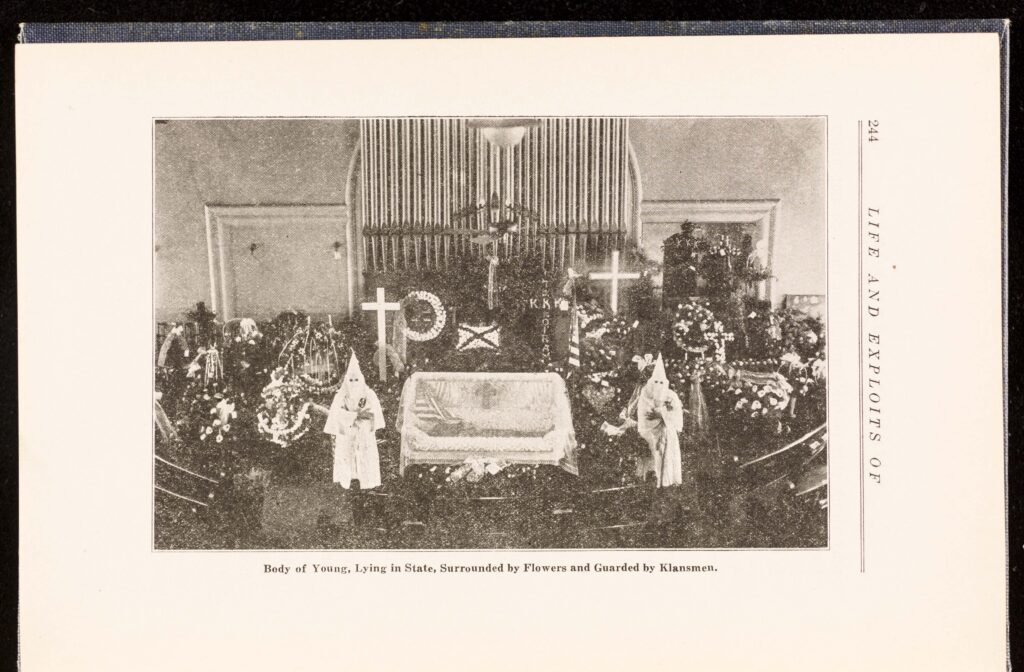

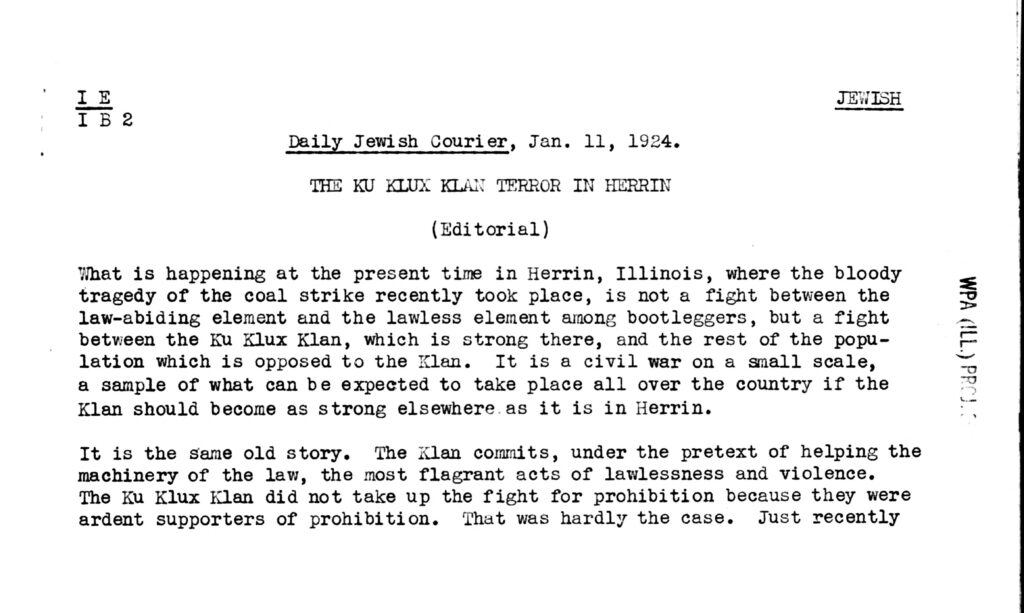

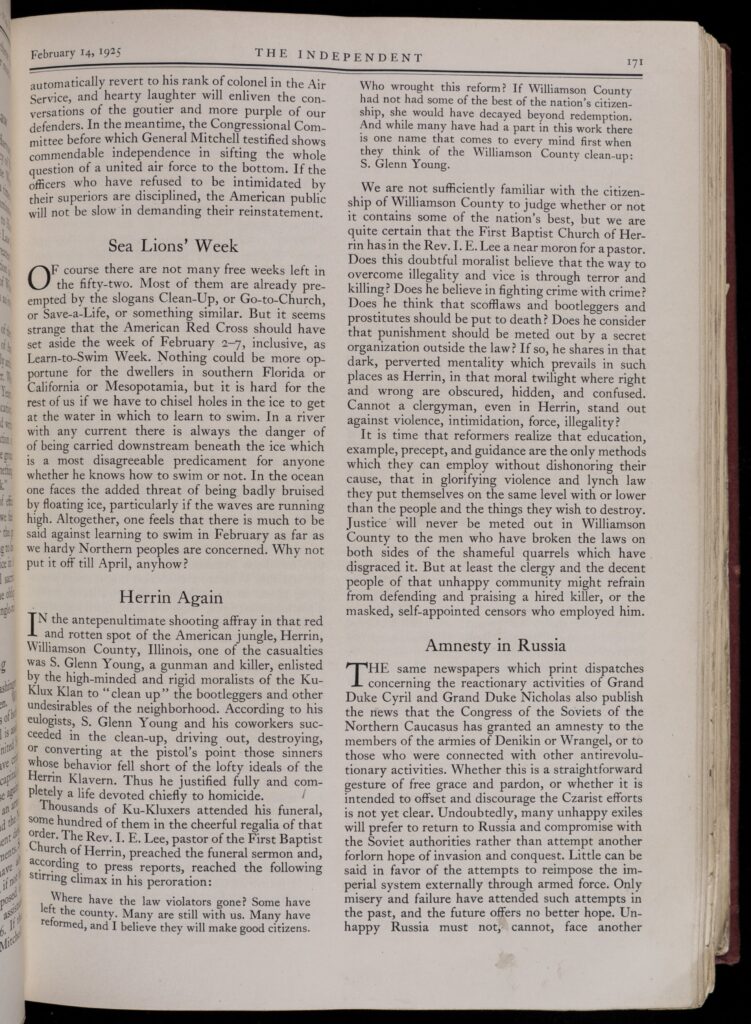

Historian Lisa McGirr has traced the problems with Prohibition enforcement and its long-term effects in her recent book, The War on Alcohol: Prohibition and the Rise of the American State. As early as 1922, President Warren Harding criticized the “national scandal” of non-compliance with Prohibition. The Ku Klux Klan saw an opportunity in the new law to pursue its anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant, anti-Semitic, white supremacist agenda. Promising to cleanse communities of bootleggers, moonshiners, and “vice operators,” the KKK attracted two to five million Americans to its ranks by 1925. Wherever the Klan gained significant political power, they prioritized Prohibition enforcement, particularly against what they called “foreign bootlegging.”

Williamson County, located in the state’s southern region known as Egypt, had had a particularly bloody and violent recent past. Settled by old-stock whites from Virginia, the Carolinas, and Kentucky, the county was culturally more like its rural southern neighbors than cosmopolitan Chicago, 300 miles to the north. Rich in coal, the county was a center for mining; its workers defended the tenuous economic security they had won through membership in the United Mine Workers of America. Still, the mining industry was mechanizing in the 1920s and eliminating jobs; in many outlying mining communities in the county, people lived in primitive conditions and grinding poverty.

Most recently, the town of Herrin had been the site of a labor strike that had turned violent. In June 1922 the Southern Illinois Coal Company brought in strikebreakers to load and ship coal. When mine guards killed two striking miners who had attempted to stop the process, a group of union miners surrounded, captured, and killed the mine guards, strikebreakers, and managers. In all, nineteen men were killed in what became known as the Herrin massacre. Although an investigation resulted in more than forty indictments, the five men tried for murder were acquitted by local jurors.

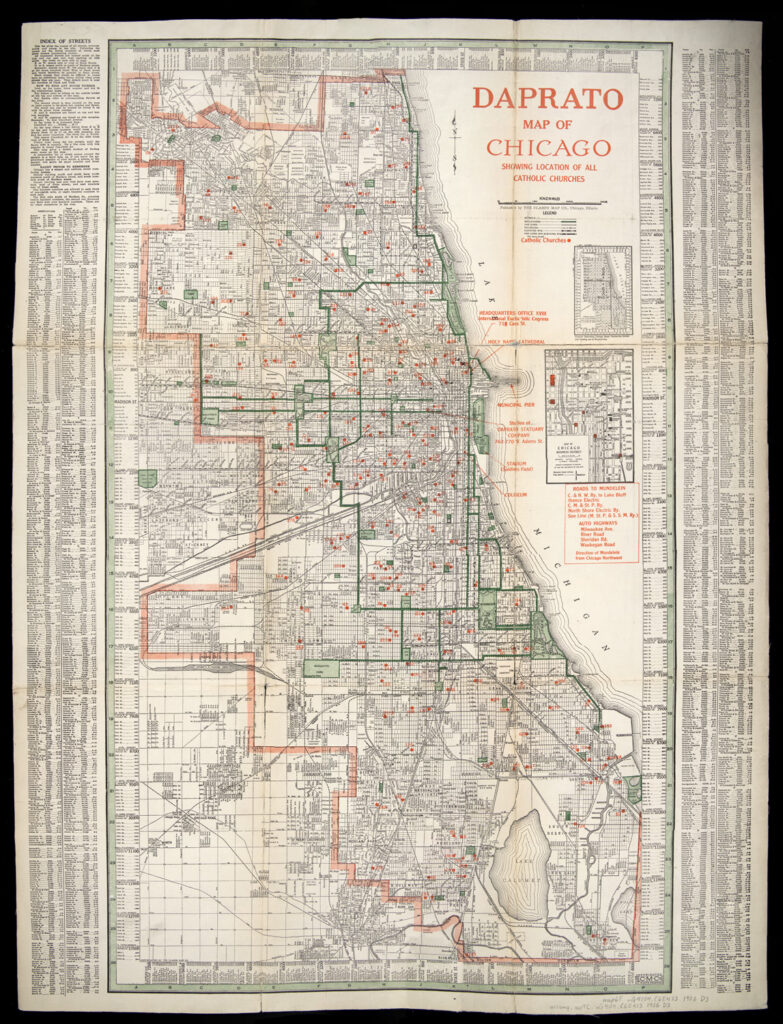

The massacre left the town with a scarred national reputation and the community deeply divided. The strike revealed miners’ fears about their fragile economic position. At the same time, Protestant ministers and their allies, many of whom were local businessmen, shop keepers, and reformers, focused their community’s attention on what they considered another stain on Williamson County: its public vice. With high hopes that as the Eighteenth Amendment eliminated alcohol it would clean up saloons, gambling dens, and brothels as well, these community leaders pushed for stringent enforcement of the Volstead Act, the Eighteenth Amendment’s enabling legislation. In the spring of 1922, even before the strike had ended in violence, businessmen and ministers formed a local Law Enforcement League. They drew upon racial, ethnic, and religious divisions that existed in Williamson County’s working class to target the county’s Italian Catholic immigrant community.

Foreign-born Italian Americans and their American-born children made up nearly 20% of the county’s population in 1920, and 35% of neighboring Franklin County. They had moved to the area in the early twentieth century to find jobs in and related to mining. Distinct from their Protestant neighbors religiously, Italian Americans also differed in their drinking culture, practices that were largely beyond the influence of Protestant pastors. Motivated by a desire to rehabilitate their community’s reputation after the massacre, ministers and their reform allies joined forces with an expanding KKK in Illinois. Although the county’s Law Enforcement League was led by Protestant ministers, by the summer of 1923 its foremost supporter was no longer the Anti-Saloon League, but the KKK. Williamson County Prohibitionists unleashed an enforcement campaign that targeted Catholics and immigrants. In a public address one minister labeled all members of the local Catholic parish “bootleggers” and promised to jail them.

The Law Enforcement League followed its rhetoric with action. It bypassed apathetic state officials and secured authorization from the federal Prohibition commissioner to organize local raids and pursue prosecutions. The League hired Seth Glenn Young, a former Prohibition agent, who spent the fall of 1923 gathering evidence. On the night of December 22, 1923, three Prohibition agents sent to Williamson County deputized Young and five hundred men, mostly Klansmen. They formed into small, armed groups and raided more than 100 places that night, arresting more than seventy-five alleged Volstead violators. Two weeks later a second raid targeted private homes in Herrin’s Italian community, which enforcers assumed was a source of illegal liquor. Raiders meted out rough treatment, including theft and planted evidence. Outraged Italian American Herrin residents appealed to their consulate, which reported the raids to the State Department. National Guard troops were called in to quell the chaos. Although Federal Prohibition officials promised no further raids in the county, local dry enforcers were not deterred. On February 2, Young led more than one thousand men in raids that covered much of the county. More than 138 people were arrested, transported to nearby Benton, IL, and marched through town with streets lined with Klan supporters. Some homes and business were set ablaze during the raids.

Selection: Reporting on ‘Bloody Herrin’ from The Daily Jewish Courier (January 11, 1924), The Outlook (February 20, 1924), The Literary Digest (September 13, 1924), and The Independent (February 14, 1925).

The violence sparked anti-Klan opposition, notably the Knights of the Flaming Circle–a group organized by a miner who had been charged with bootlegging–and the local sheriff. When the two forces confronted each other in a shootout in Herrin, civil order broke down. Young jailed the mayor and sheriff and appointed himself the town’s authority. Illinois’ governor declared martial law in Williamson and returned the National Guard to Herrin. Young’s vigilantes were disarmed and Young himself faced charges for assault, battery, and theft.

Although the large raids ended, conflicts between drys and wets, and between anti-Klan and Klan forces, continued, encouraged by Williamson’s Protestant ministers, who praised Young as a hero. The dry militant was killed in a shootout with a leader of the Knights of the Flaming Circle in January 1925.

Although Young’s death marked the decline of local Klan power in Williamson, it accomplished some of its goals, both immediate and long-term. Around 50 soft-drink parlors (which sold alcohol illegally) permanently closed. More significantly, the raids and the terror they created pushed immigrants and African Americans out of the county. More than one-third of immigrants and their children left, as did between one-quarter and one-third of African Americans.

The chain of events that led to enforcement in places like Williamson County permanently changed and expanded the national penal system. The number of federal prisoners quadrupled between 1915 and 1930 (from 3,000 to 12,000). A larger prison population required organized administration and more record keeping. President Hoover created the Federal Bureau of Prisons in 1930. Although the Census Bureau had kept track of the number of prisoners, the new bureau took over this task, with increasing sophistication and professionalization. More prisons were built, and the parole system was expanded. By 1929 the Prohibition Bureau appropriated more than $15 million, which was more than three times what it had been in 1920, and equivalent to over $200 million today. This spending created the first significant national police force.

As Lisa McGirr argues, in the longer term, today’s “War on Drugs” is, in many ways, Prohibition’s policy legacy. Begun in 1971 by Richard Nixon, the modern campaign against narcotics has been even more selectively enforced than Prohibition was. Race has played a much more central role in sentencing and enforcement, leading to such discriminatory sentencing that some states have been cited for violation of international human rights agreements.

Questions to Consider:

- In the aftermath of so-called clean-up raids to enforce Prohibition, Herrin and Williamson County found national attention in 1924 and 1925 from publications like The Outlook and The Independent, as well as in national-level newspaper coverage. What opinions did these sources hold about Prohibition enforcement? Did they consider Prohibition a success or failure as policy?

- What did The Independent mean by the phrase, “cheerful regalia” about the KKK’s cloaked appearance in public?

What about Gangsters and Organized Crime?

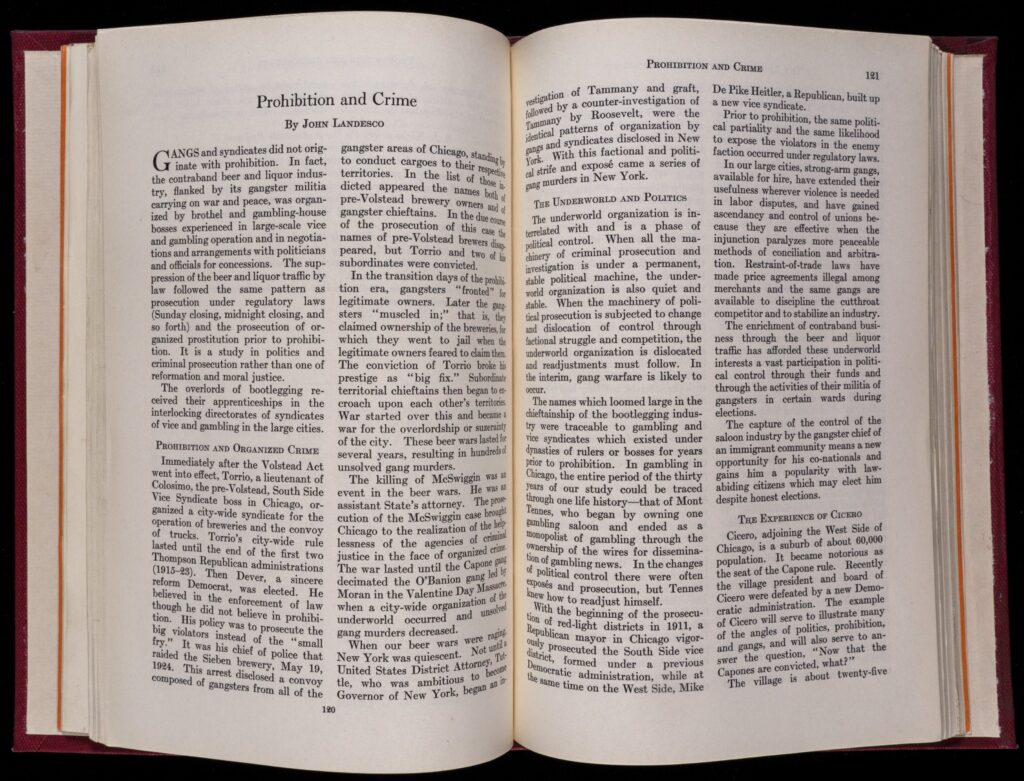

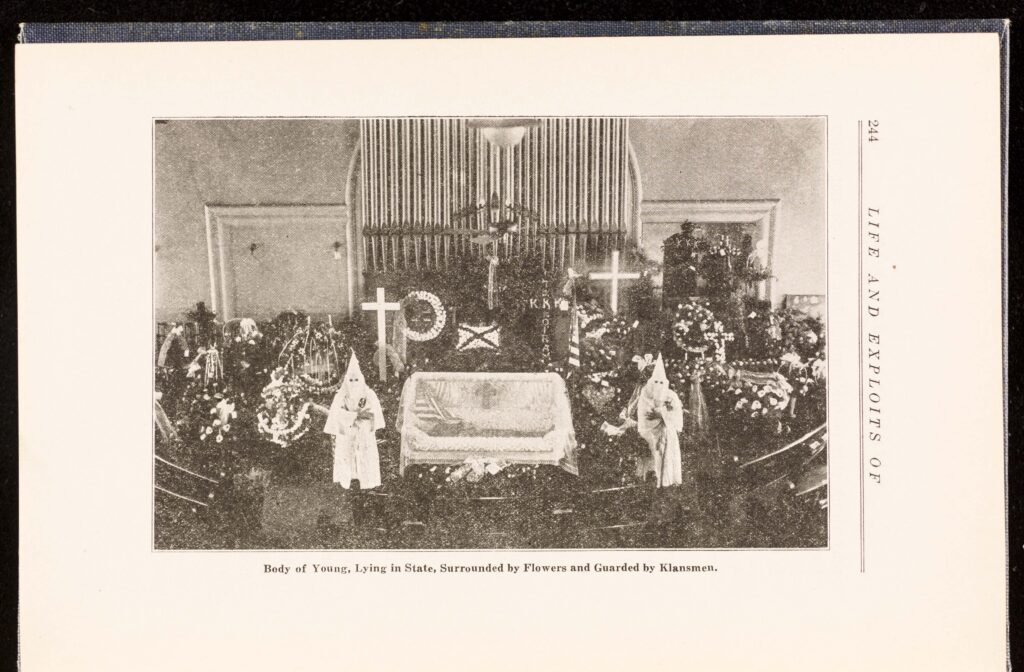

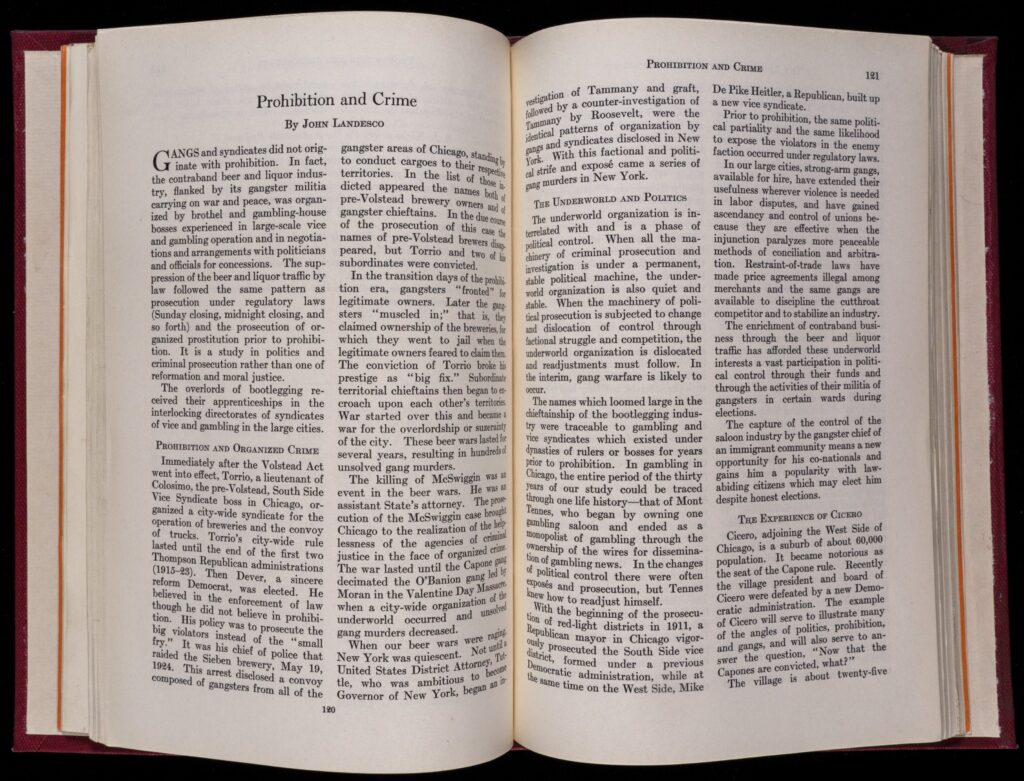

Focusing on Prohibition enforcement, like the example in Williamson County, rather than crime, compels us to reexamine a central, but incorrect, narrative about Prohibition: that it led to the creation of organized crime. John Landesco, a University of Chicago sociologist, and others, investigated this question during the 1920s. He published his findings as part of a landmark study in 1929, The Illinois Crime Survey. In 1932 he published a short article, “Prohibition and Crime,” in a professional journal, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, which is included here.

Landesco compared the homicide rate during Prohibition (when Chicago gangs battled over control of bootlegging in the notorious “beer wars”) with earlier decades and found that in the ten years between 1900 and 1910 the murder rate actually increased sharply, while it remained steady for much of the 1920s. Using statistics and crime data he also showed that organized crime existed before Prohibition, although it expanded during this period. Regulatory laws against prostitution, alcohol, and gambling had created the corrupt system of paying off officials and controlling territory, which continued under Prohibition. The Eighteenth Amendment also did not create gangsters; they already existed. Prohibition simply provided them another opportunity, which they exploited. These young men, most of whom, Landesco pointed out, were American-born, did so because they lived in neighborhoods without better alternatives to crime, which were already controlled by criminal gangs. Furthermore, Landesco argued that all of the institutions that should have helped them–the home, the church, schools, vocational education, government, the playground, and settlement houses–had failed them. For the “gangster chief of an immigrant community” to capture the saloon industry, as Landesco put it, meant upward social mobility for him and his community. Lastly, he pointed out that Prohibition created two kinds of special homicides. Gang war deaths were well known, but Landesco realized that Prohibition also led to liquor law enforcement killings. Between 1920 and 1930 more than 1,500 people (police officers and civilians) died during violent clashes over Prohibition enforcement.

Questions to Consider:

- We take for granted that crime and criminality increased markedly because of Prohibition and its widespread violation. At the end of his essay Landesco suggests causes other than Prohibition for this rise, although no data existed for him to confirm his theories. Do any of his ideas seem plausible, especially with the benefit of nearly ninety years of hindsight?

Flappers, Rebellion, and Repeal

“While the Prohibition era yielded numerous surprises, few were as startling as women’s rebellion against the noble experiment,” declared historian Michael A. Lerner recently. Flappers started the revolt.

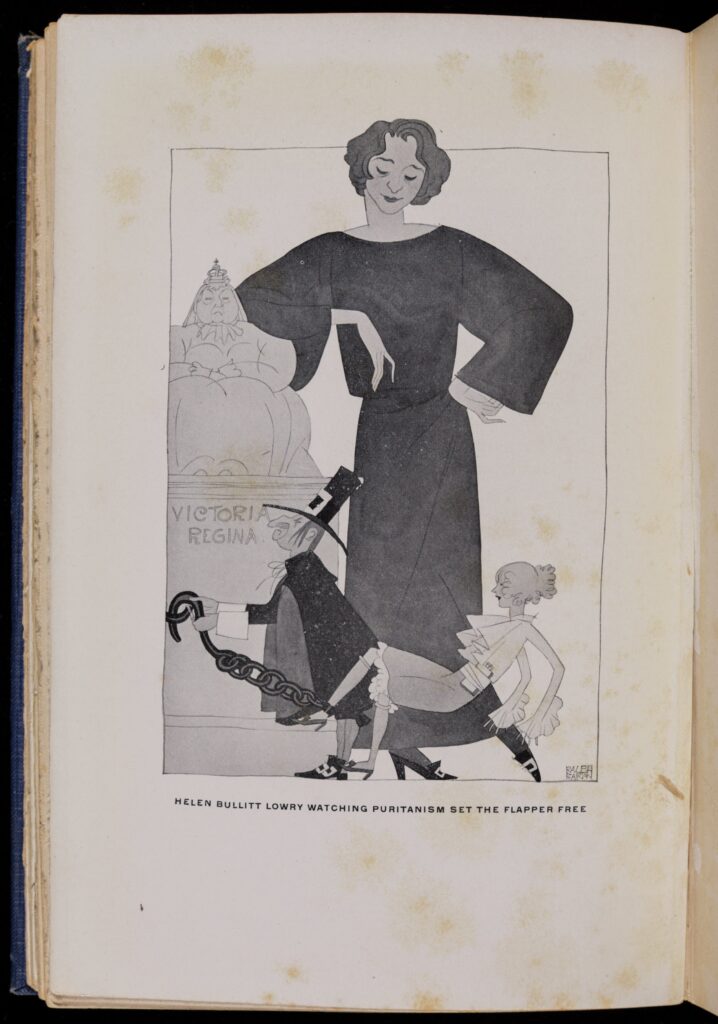

In a 1922 essay, “The Uninhibited Flapper,” journalist Helen Bullitt Lowry characterized the flapper’s revolt by her flask. “The flapper is released from the strangle hold that is throttling the rest of us,” she wrote. “If somebody makes a law for her, she promptly and blithely breaks it, the pocket flask for the moment being the outward and visible sign of the spirit—and spirits—of her wide-flung rebellion.” Lowry understood the flapper’s goal–to destroy the sexual double standard:

“So that for the reformers and the prohibitionists, the censors and the woman’s club resolutionists! Their bi-product is Miss Twentieth Century Unlimited, the one uninhibited creature in Volsteaded civilization. Controls—of liquor and of birth—have given us The Flapper. The official reformers, reinforcing the sagging inhibitions and corsets of the nineteenth century, were just the final impetus needed to drive her out into the open.”

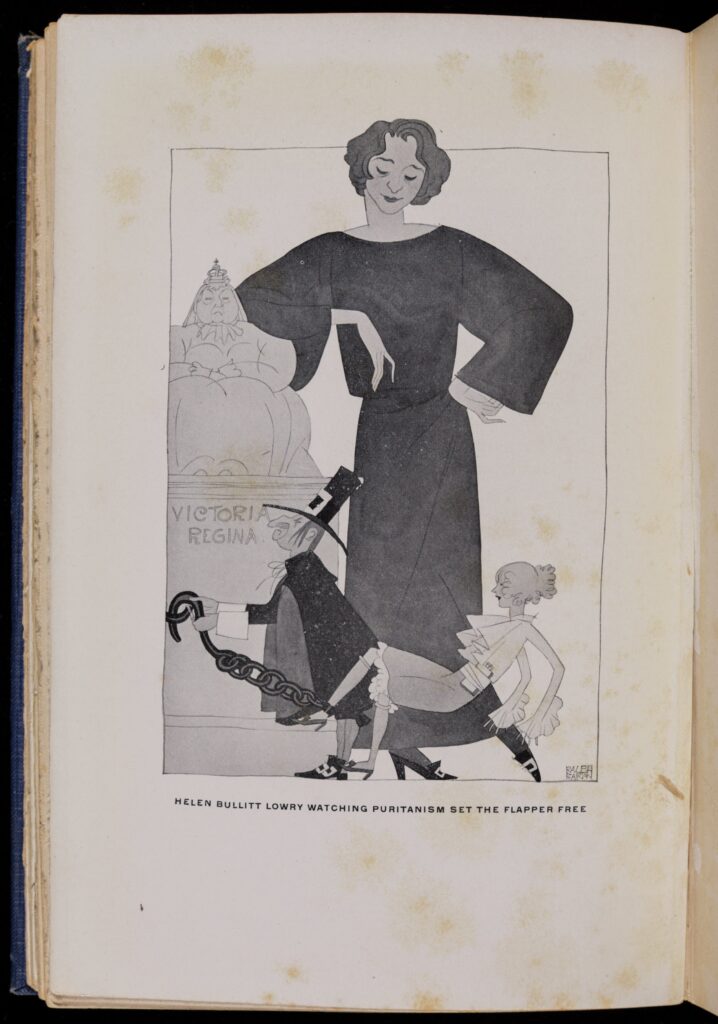

The lessening of controls on young women’s sex and drinking, Lowry observed, allowed them to bring their behavior closer to men’s, eliminating the need for a double standard, a state of affairs Lowry called “Puritanical.” Young women no longer had to act more innocent than they were, and young men didn’t have to pretend all their intentions were honorable or to hide certain behaviors from women. In the cartoon that accompanied her essay, a larger-than-life Lowry leans on a statue of Queen Victoria while supporting a young flapper sprawled against her feet. As Lowry watches, a middle-aged Puritan releases the flapper from a chain attached to the base of Victoria’s pedestal.

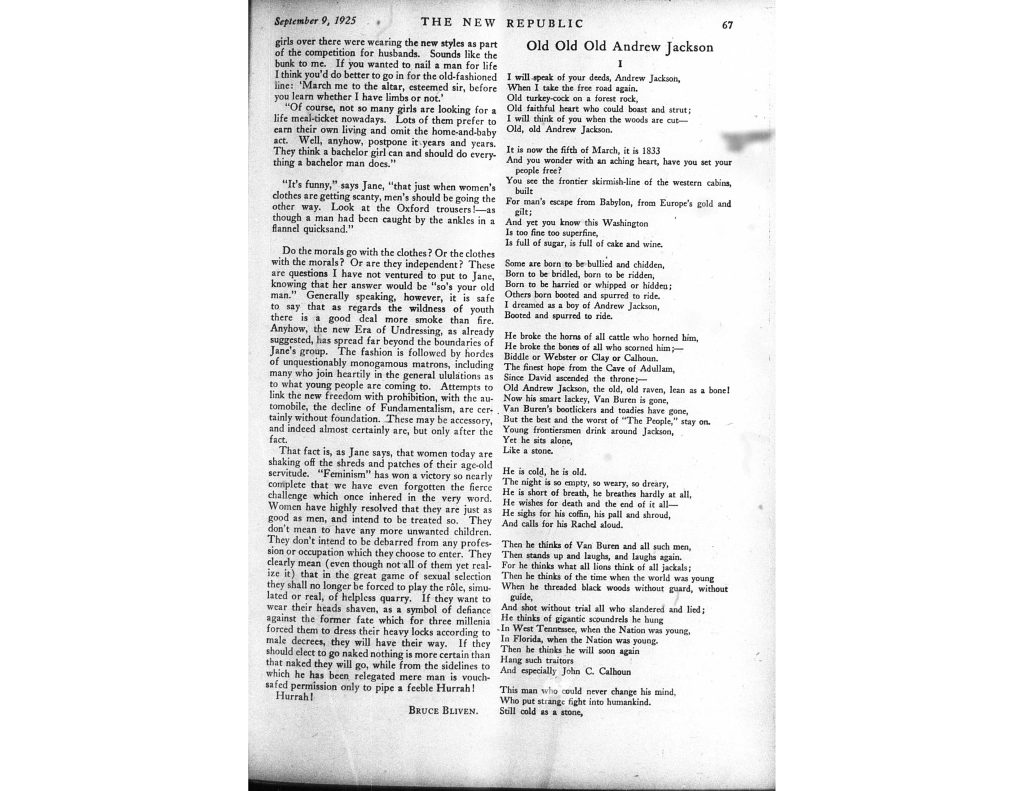

Bruce Bliven, a writer for The New Republic and its future editor, wrote much the same thing a few years later in a 1925 article, “Flapper Jane,” although he used a more restrained tone: “They [flappers] clearly mean . . . that in the great game of sexual selection they shall no longer be forced to play the role, simulated or real, of helpless quarry.”

Selection: Bruce Bilven, “Flapper Jane,” in The New Republic, 65-67 (September 9, 1925).

Caricaturist Miguel Covarrubias also portrayed flappers as central actors in American culture in his circa 1930 double portrait of New York night club owner Texas Guinan and Woman’s Christian Temperance Union President Ella Boole. It appeared in Vanity Fair in January 1933 as part of a regular feature, “Impossible Interviews.” This one paired Guinan and Boole by pointing out how both women benefitted from, and needed, Prohibition. Between 1924 and 1931, Guinan became New York City’s most successful club owner, opening and managing a series of spectacular night clubs, and the city’s most exuberant example of flapper culture. She was also a symbolic leader in the rebellion against Prohibition, according to Michael Lerner. Boole, as head of what had been to that point the largest women’s reform organization in US history, represented the political counterpoint to Guinan. By 1933, when this article appeared, repeal was around the corner and the WCTU’s political star was in serious decline.

Flappers rejected the moral authority earlier generations of women had adopted to effect social and political change. This rejection broke apart deeply-held cultural and religious assumptions about gender, morality, and behavior, and separated the issue of temperance from women’s political identities. Politically it destroyed any lingering, post-suffrage illusions that women would vote as a unified (and moral) political bloc.

Writer Margaret Culkin Banning captured this political turn. In a 1930 article in Vogue, she identified a shift in opinion among young, urban women away from the excessive, rebellious drinking of the flapper on the one hand, and toward Prohibition law reform on the other. While she implicitly gave the flapper her due, in helping to destroy “artificial restraints,” Banning assumed her readers accepted moderate drinking for women. She normalized a new drinking standard for women and redefined temperance in the process, which she still called “a good and lovely thing.” Yet, she unequivocally insisted that women could not go back to an earlier attitude that “regarded liquor as a sin and wanted to forbid and prohibit.” Banning also praised Pauline Morton Sabin, a socially prominent New Yorker (heiress to the Morton Salt fortune), who was a relatively new player in Prohibition politics.

Although Sabin had not been a suffragist or worked for the Eighteenth Amendment, when she entered party politics in the early 1920s, she rose quickly. By 1923 she was appointed to the Republican National Committee. Like many women during the 1920s, Sabin changed her mind about Prohibition. Originally supporting it as a policy that would improve the world and help her sons, she grew disillusioned with the hypocrisy of Prohibition supporters who personally used alcohol and began to resent temperance leaders’ insistence that all women supported the Eighteenth Amendment. In a later interview, Sabin recounted the moment she realized her own political rebellion. Upon hearing WCTU President Ella Boole state in front of Congress, “I represent the women of America!” Sabin said to herself, “Well, lady, here’s one woman you don’t represent.” She held back until after the 1928 election, which took Republican Herbert Hoover to the White House, then resigned from the Republican National Committee and formed the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform (WONPR), a national, bipartisan women’s group to change and then repeal the law.

Sabin took Guinan’s revolt and turned it into political independence. As historian Michael Lerner put it, “[she] . . . showed American women that they were no longer bound to support the Prohibition movement politically, just as flappers had shown women that they were not obligated to uphold outdated social mores.” Sabin and the women of the WONPR were not flappers; however, the press and public embraced them as having an iconoclastic spirit, and portrayed them as smart, sophisticated, modern women. By the end of 1931 the WONPR had attracted more than 400,000 members and it soon surpassed 1.3 million, making it the largest repeal organization in the nation and Sabin the de facto leader of the movement. At the end of the Prohibition decade women’s position on the issue had reversed: where before women had learned to consider alcohol their enemy, by 1930 they, as a whole, no longer believed that.

Questions to Consider:

- Were flappers rebels? If so, what did they reject? Or, as Lowry and perhaps Covarrubias suggested, were flappers less free than their behavior appeared? How or how not?

- What is the meaning of the cartoon caption, “Puritanism set the Flapper free”? Lowry offered a similar idea in her essay: “[t]he real interstate joke on Puritanism is that the flapper, who flaps because Puritanism has driven her to it, will automatically bring about its cure” (p. 79). What would the flapper cure in American society, according to Lowry? Did the flapper change anything in the United States during the 1920s? Or afterwards?

Chicago, Anti-Prohibition, and a New Coalition

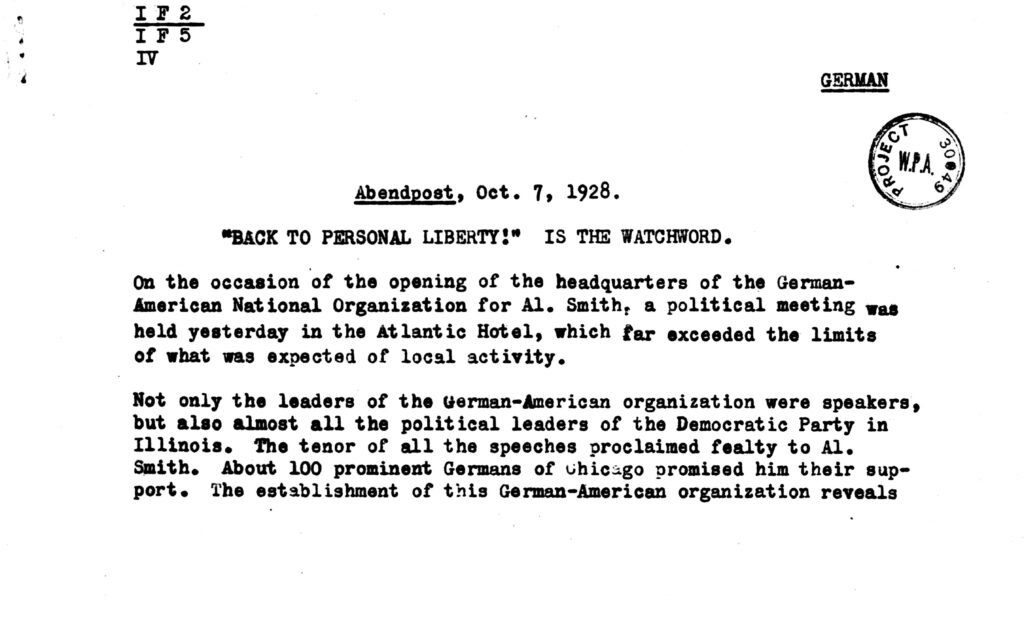

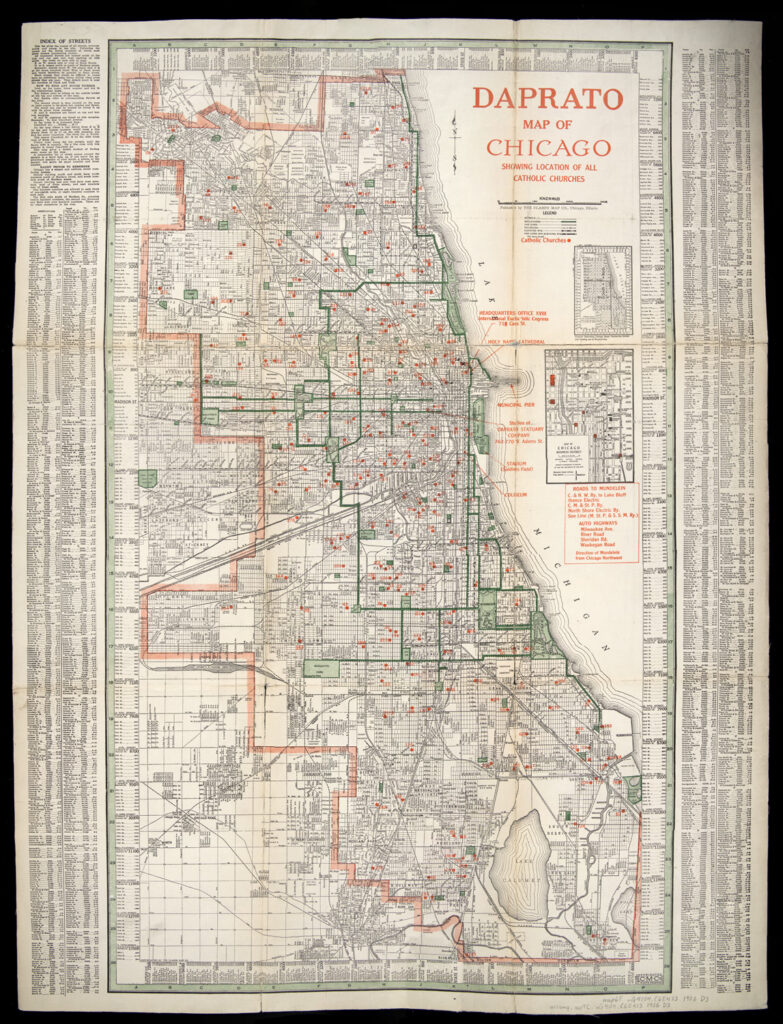

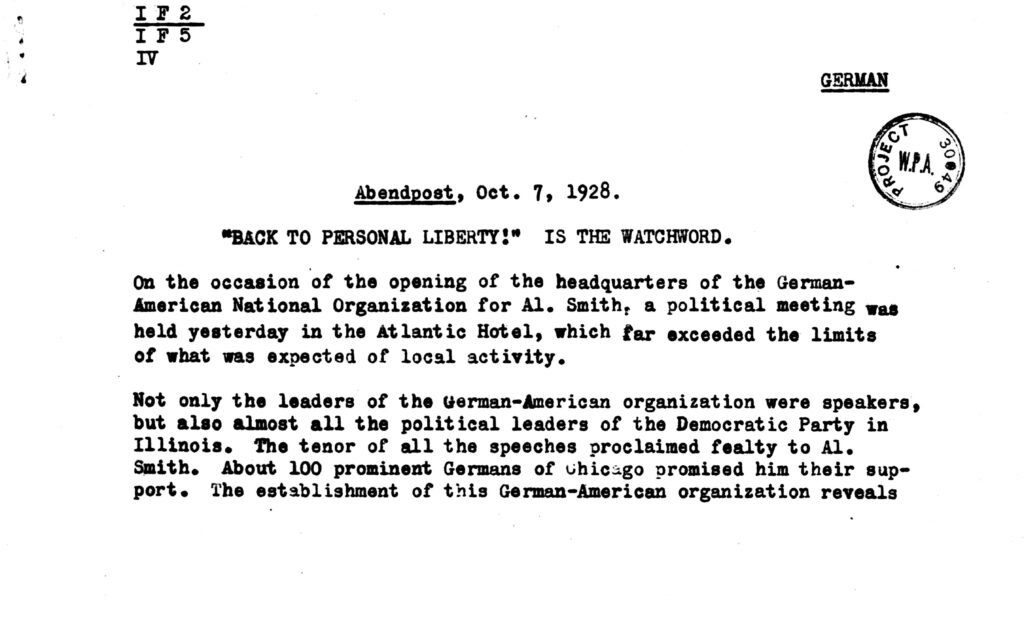

Although Prohibition seemed to end with the beginning of the New Deal—repeal being one of FDR’s economy-boosting measures during his first 100 days—in fact, politically, Prohibition’s end had come sooner. As the Abendpost, the largest German-language newspaper in Chicago, put it in 1928, “it [opposition to the Eighteenth Amendment] isn’t foremost about thirst.” Rather, it was the rejection of “morality through police handcuffs” and “the dictatorship they [Prohibitionists] seek to establish.” As historian Lisa McGirr has shown, Prohibition led to the political mobilization of ethnic, working class people into the Democratic Party for the 1928 election—four years earlier than most historians have generally understood this new coalition to have occurred, and well before the Depression and the New Deal. Repeal happened because of wide and organized opposition to Prohibition; middle and upper-middle class women in the WONPR (as we saw in the previous section) and working class ethnic people who moved from the Republican to the Democratic Party.

The New Republic sensed part of this political change during the 1927 Chicago mayoral election, a contest that the frankly corrupt and rascally Bill Thompson, a Republican, won easily over the Democratic incumbent, William Dever. In “Why Did Chicago Do It?” the magazine recognized that voters who had responded to Thompson’s ability to build a political coalition were a new, up-and-coming coalition of “polyglot Americans.” They were “a class-conscious sub-community which is just beginning to get together in large American cities and to find itself out. . . . they are creating a new urban America . . . which is divorced from the old America of rural and middle-class Puritanism.” Dever’s mistake (although not his only one) was to try to enforce Prohibition on a wet city.

The next year’s presidential contest, between dry Republican Herbert Hoover and wet Democrat Al Smith, unleashed a torrent of Democratic Party mobilization among Chicago’s ethnic groups. Independent Polish, Czech, Italian, and German groups worked for Smith. As one Czech daily paper announced, it was “Governor Al Smith or Prohibition.” Polonia, the city’s major Polish newspaper, called the election one of the nation’s most important because at stake was “religious tolerance, the victory of personal freedom . . . .” As the Abendpost’s editors put it in an October 1928 headline about the organization of German-Americans for Al Smith, “‘Back to Personal Liberty!’ Is the Watchword.” By incorporating the anti-Prohibition slogan, “Personal Liberty,” into the headline, the paper made its position on Smith and the 1928 election clear.

The mobilization worked. Before 1928 Chicago’s Polish community had pretty nearly divided its vote between Democratic and Republican presidential candidates. But in this election, Poles voted overwhelmingly for Smith; nearly 80% of them voted for the governor from New York. The pattern in Chicago–of immigrant, ethnic communities rallying to Smith’s banner—occurred in major, industrialized cities throughout the Northeast and Midwest, from Boston and New York, to Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, and Milwaukee. Although before this election one could not generalize about an ethnic vote in the United States, after it the idea had taken shape. In 1932 this coalition would sweep Roosevelt into office and inaugurate the New Deal and its realignment of national policy.

Questions to Consider:

- What did The New Republic writer mean when he said that the explanation for Thompson’s victory in Chicago “is not economic or moral. It is social”?

- In the December 1926 Abendpost article about Candidate Thompson’s speech, the reporter seemed to agree with Thompson’s assumption that Volstead violators were not “criminals.” Do you agree? According to how Thompson described Mayor Dever’s enforcement policies, what were Thompson’s audience’s main objections to how the Eighteenth Amendment was enforced?

- “Personal Liberty” was the slogan of the wets. How might have this phrase have resonated with ethnic voters beyond alcohol?

Prohibition and Twentieth Century US History

As late as 1930 a Progressive as significant as Eleanor Roosevelt declared, “I believe in Prohibition,” although she did aver “some difficulties about enforcement.” It was a statement with which many of her fellow women Progressives agreed. A 1928 Outlook magazine poll reported that 77% of American women under age 45 who were polled still supported Prohibition, a percentage that had not moved appreciably for eight years. (For men of the same age, the approval rate had dropped from 67.5% to 58%.) Drinking rates after repeal did not return to pre-Prohibition levels until the 1960s, more than a generation after the end of the Eighteenth Amendment. These facts in themselves can only suggest that Prohibition had a longer, more significant effect on American society than is usually realized. Events in Williamson County, Illinois, New York City, and Chicago reveal how deeply Prohibition reshaped American culture and social processes, from social behavior, to the shape of the justice system, to presidential politics and national social policy.

Further Reading

Angle, Paul M. Bloody Williamson: A Chapter in American Lawlessness. New York: Knopf, 1952.

Blocker, Jack S., Jr., American Temperance Movements: Cycles of Reform. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1988.

Kyvig, David E., ed. Law, Alcohol, and Order: Perspectives on Prohibition. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1985.

Lerner, Michael A. Dry Manhattan: Prohibition in New York City. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007.

Green, Paul M. and Melvin G. Holli, eds. The Mayors: The Chicago Political Tradition, revised ed. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1995.

McGirr, Lisa. The War on Alcohol: Prohibition and the Rise of the American State. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2016.

Peel, Roy V., and Thomas C. Donnelly. The 1928 Campaign: An Analysis. New York: New York University Book Store, 1931.