Introduction: Experiencing the Great War

The First World War lasted over four years, from August 1914 through November 1918. The Allied powers of Great Britain and its dominions and colonies, France and its colonies, Russia, Japan, Italy, the United States, and numerous smaller powers fought against the Central powers of Germany and its colonies, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria. The cost of the war was unprecedented in terms of money, property, and human lives. Over ten million soldiers died and twenty million were wounded. Though the war was fought on three continents, the war in Europe accounted for most of these losses.

Europe’s “western front” stretched from the English Channel through Belgium and France to the Alps. This front transformed the war from a regional confrontation between Russia and Austria-Hungary into a continental struggle. The bulk of the fighting between four global empires and economic world powers – Great Britain, France, Germany, and, after 1917, the United States – took place along the western front. The war also ended there on November 11, 1918. All of our sources focus on the western front.

Through acts of experiencing and remembering, the influence of the war lasted well into the twentieth century.

Fifty million soldiers and numerous medical, clerical, and intelligence personnel experienced the war first-hand. People on the “home front” – residents of warring countries who lived away from the fighting – formed their own experiences of the war through newspapers, maps, illustrated magazines and films. While most wartime governments restricted descriptions of casualties and battlefield conditions, soldiers wrote poems and works of fiction about the realities of battle.

After the war, generals and politicians defended their decisions during the conflict in memoirs about war strategy and high politics. Soldiers and others contributed more personal narratives of life on the front and in the hospitals. As veterans and their loved ones settled into their postwar routines, the war remained a part of their lives. For some, this meant dealing with lingering injuries, disabilities, and “shell shock” (now called Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder). Others visited cemeteries, memorials, and war sites. Most people commemorated the anniversary of the end of the war on November 11 as “Armistice Day,” “Remembrance Day,” or, after the Second World War, “Veterans Day.” Through these acts of experiencing and remembering, the influence of the war lasted well into the twentieth century. In many ways, the First World War defined that century and still affects us today, over one hundred years later.

Essential Questions:

- How does the experience of war differ from person to person? Does a general know more about the war than a soldier or nurse? Why or why not?

- How did the presentation of the war change with the passage of time?

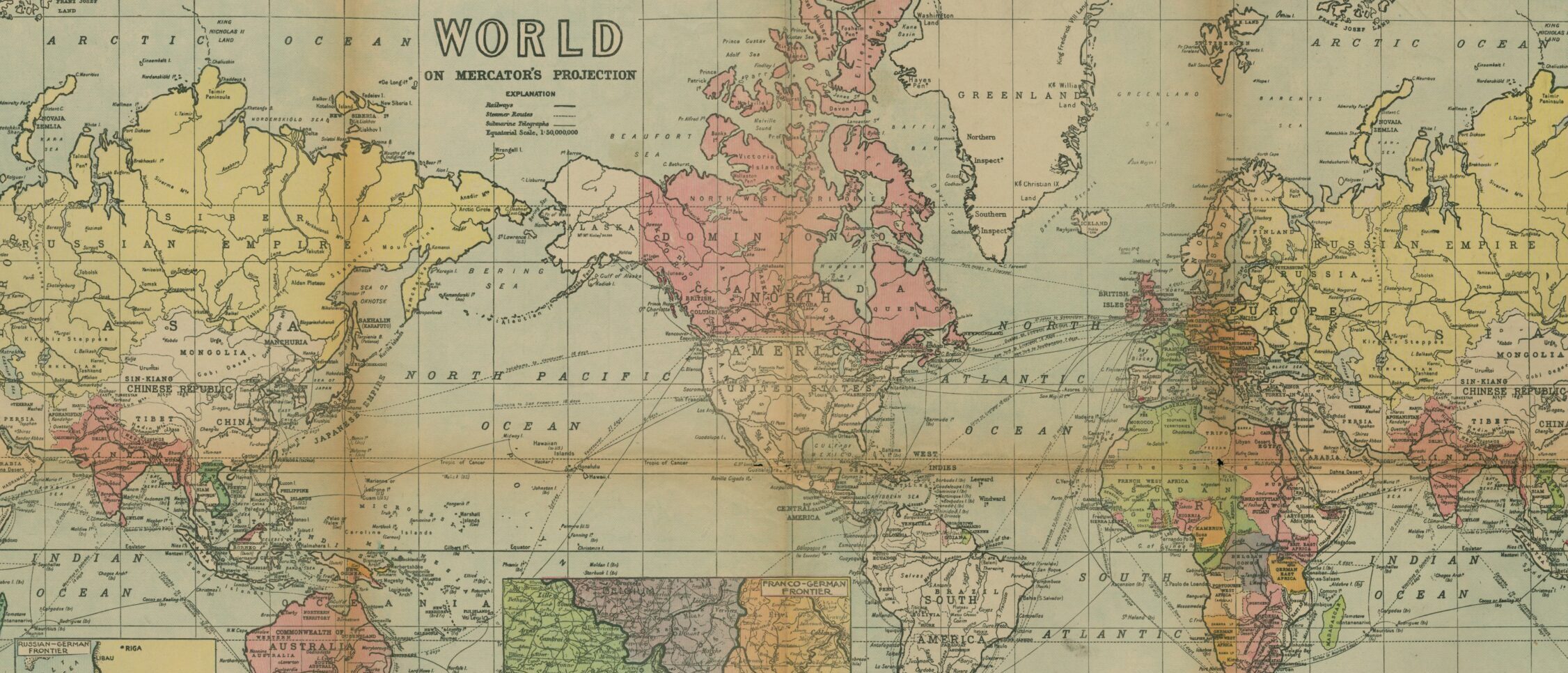

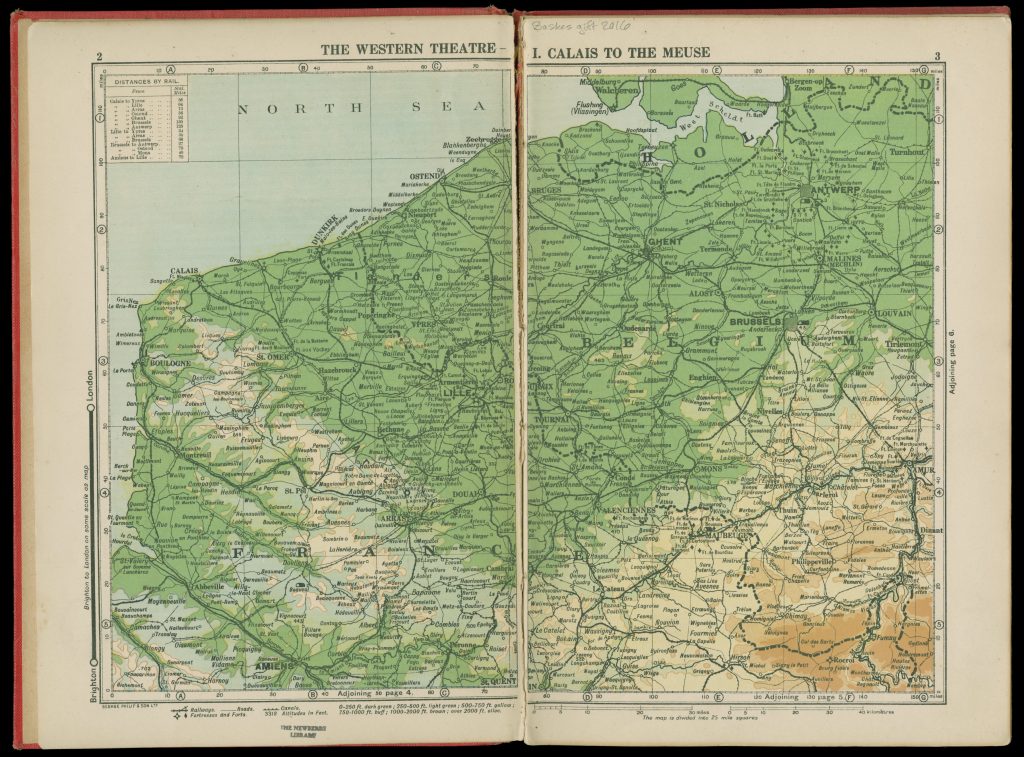

- How do maps help us understand or situate the war? What kinds of information help you understand a map? Would you make any changes to how the maps here display information?

Comprehending the Early Course of War

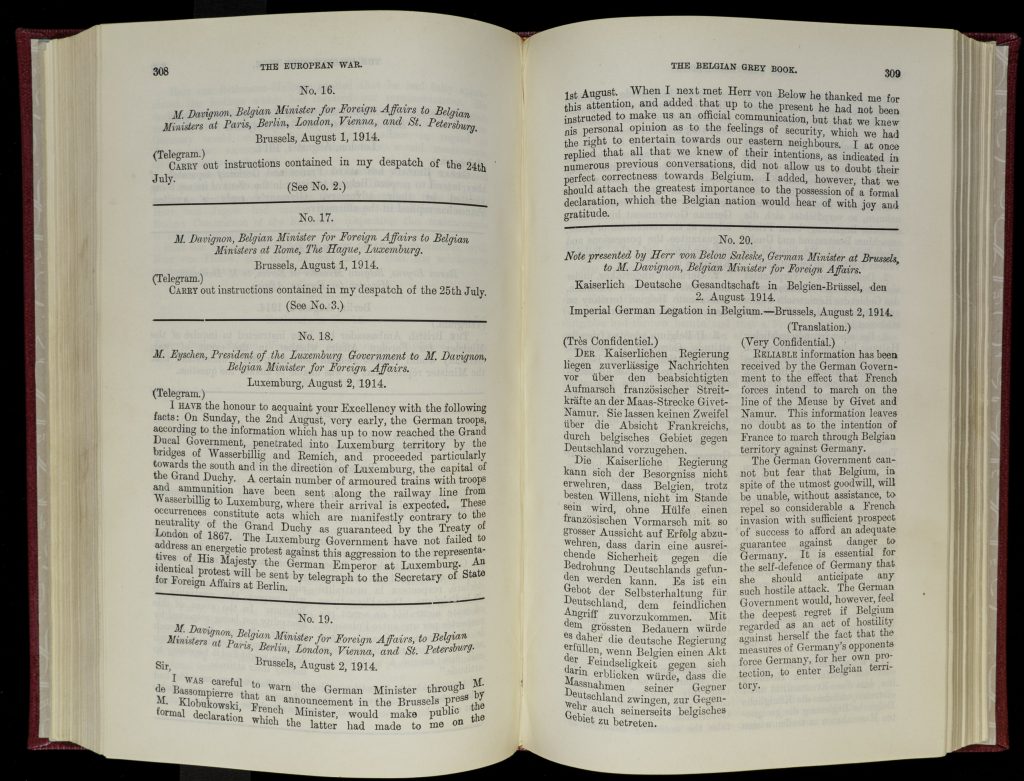

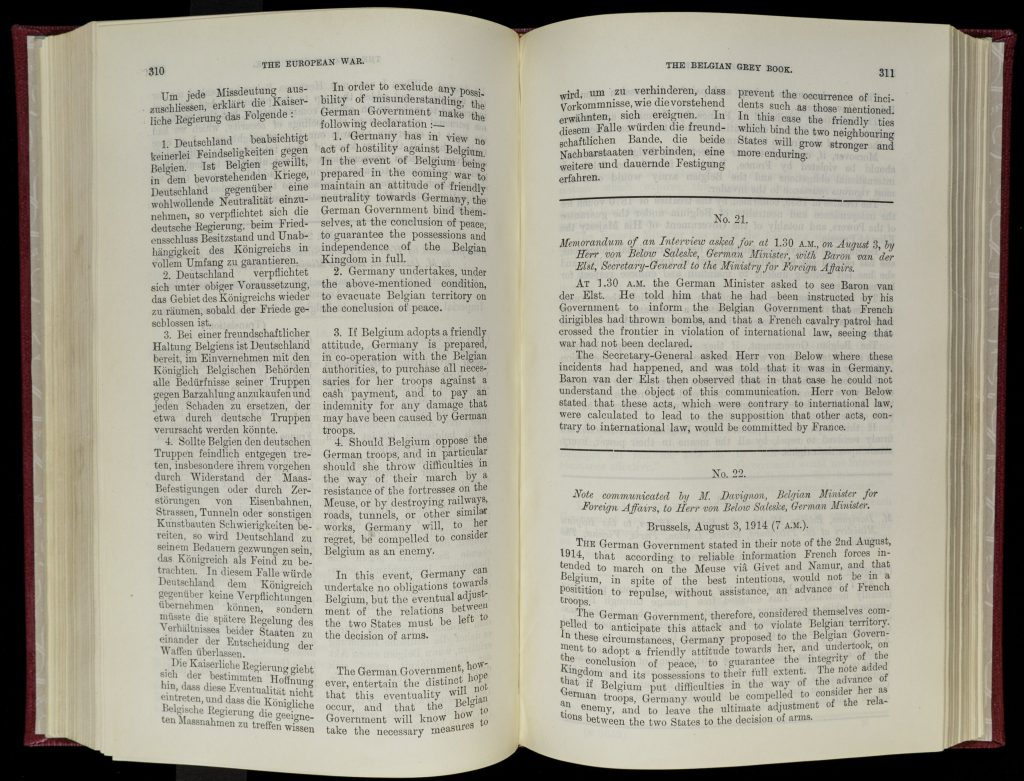

The crisis that started the First World War began in July 1914, when the heir of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Franz Ferdinand, was assassinated in Serbia. Austro-Hungarian leaders claimed that members of the Serbian government were complicit in the assassination and declared war on that country. Through July and August, other European states joined the war because of treaty promises and the opportunity to win new territory. Russia mobilized its army to pressure Austria-Hungary to delay invading Serbia. Germany, Austria-Hungary’s main ally, demanded Russia stop its mobilization and declared war when Russia did not. Germany then preemptively invaded France through neutral Belgium in order to avoid a two-front war against both France and Russia. Finally, Britain declared war on Germany and its allies, ostensibly because of its treaty obligations with Belgium.

The actions of Austria-Hungary, Russia, and Germany during this “July Crisis” were aggressive, even outwardly belligerent. Though monarchs could command these countries to go to war, they worried that their subjects might not support the conflict. To improve public opinion, leaders portrayed their countries as the wronged parties, threatened by aggressive foreign coalitions. France and Britain were essentially democratic in comparison with the continental monarchies. These governments waited on events to join the war.

In order to justify the war, governments published edited volumes of diplomatic notes and correspondence. Because different countries’ books had different colored covers, these books are called the “rainbow books.” The rainbow books claimed to present authentic documents, but all of them sought to persuade readers to a certain point of view. Some documents appeared to illustrate key decision points. Other documents were heavily edited. Even though the rainbow books are not a complete record, they are a valuable source. They provide insight into the intentions and motivations of the governments that published them.

Selection: Rainbow Book Example: Great British Foreign Office, Collected Documents Relating to the Outbreak of the European War (1915)

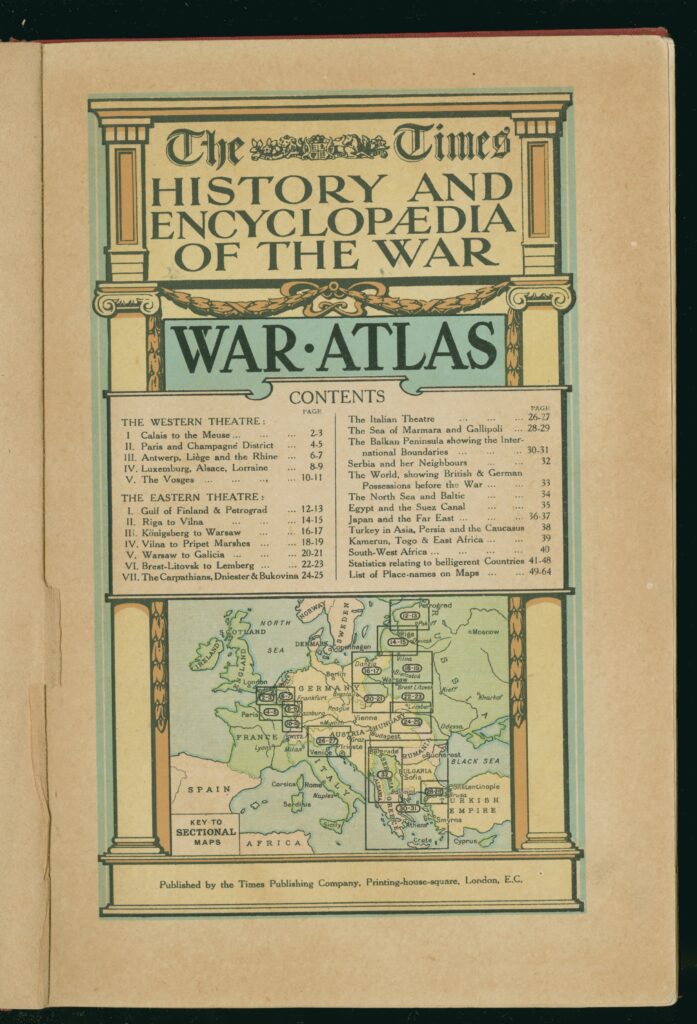

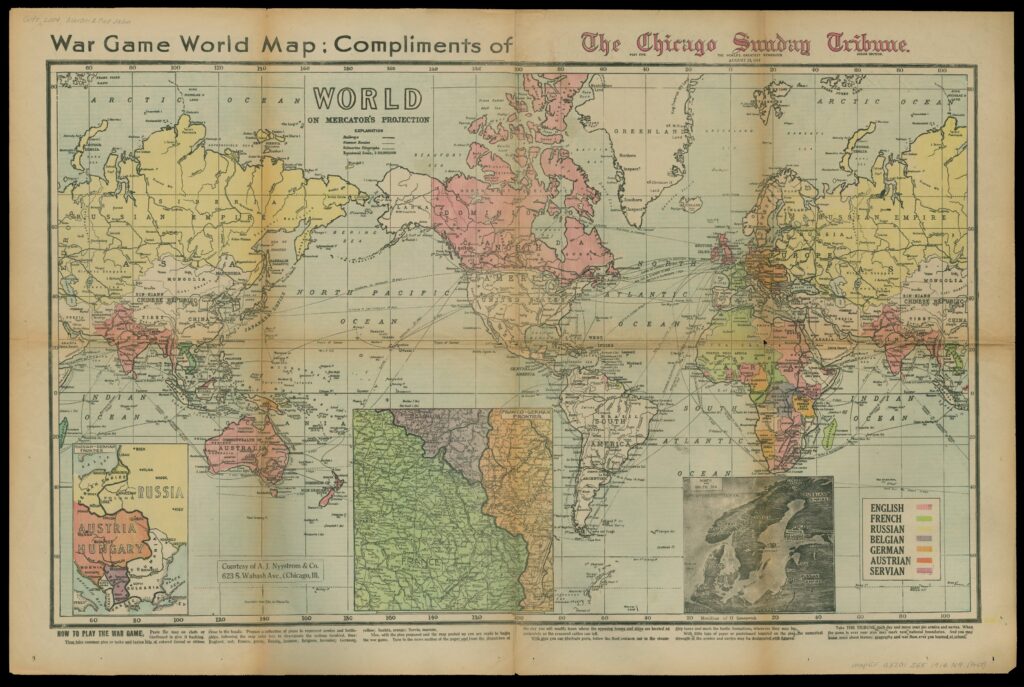

The public was eager for information once war broke out. Governments used propaganda and censorship to shape public opinion, while newspapers published reports and “special supplements.” A supplement from the Chicago Sunday Tribune pictured in the introduction. Readers could mount this map on a wall and follow the war with pins representing troop and ships. The map centered the United States, making the battle zones in Europe look small. The Times of London published its own collection of war maps in a bound edition, selected below. Its high-quality plates focus on the western, eastern, and southern fronts and include place names, coastlines, and river systems. Daily newspaper readers could use these maps to accurately follow the movements of armies on any given day.

Selection: The Times’ History and Encyclopaedia of the War: War Atlas (1916)

Both publications demonstrate the ways in which newspapers and publishers responded to the demands of their reading publics for information on the progress of the war.

Discussion Questions:

- What is the German government requesting of Belgium in this selection from the “Belgian Grey Book”? Why? What evidence does the German government present to support its request?

- How might you use these maps to follow the war? In what ways might the Tribune map be more or less useful than the Times maps? Why?

- How might the Times atlas assist readers in understanding the documents in the “rainbow books”?

The War from the Top: The Battle of the Books

The war on the western front began with a German offensive through Belgium in August 1914. This offensive pressed within 25 miles of Paris, then stabilized into a war of attrition fought from static trench lines. In a war of attrition, opposing sides try to wear down their enemies’ soldiers, supplies, and morale over a long time. Allied forces attempted to break the lines and push back German troops, but these offensives were costly and unsuccessful. The German Army attempted only two other massive offenses during the war – in 1916 at the Battle of Verdun and in the spring of 1918 during the “Ludendorff Offensive.”

The Battle of Verdun was the longest continuous struggle on the western front. In February 1916 German forces attacked a French fortress system near the city of Verdun. The defense of the fortress was a point of national pride and military necessity for the French. Around 200,000 French and German soldiers had been killed by the end of June. The front’s main fighting shifted to the Battle of the Somme in July, but Verdun remained an active battleground. When the offensive ended in December 1916, French soldiers had recovered much of the ground originally lost to the Germans.

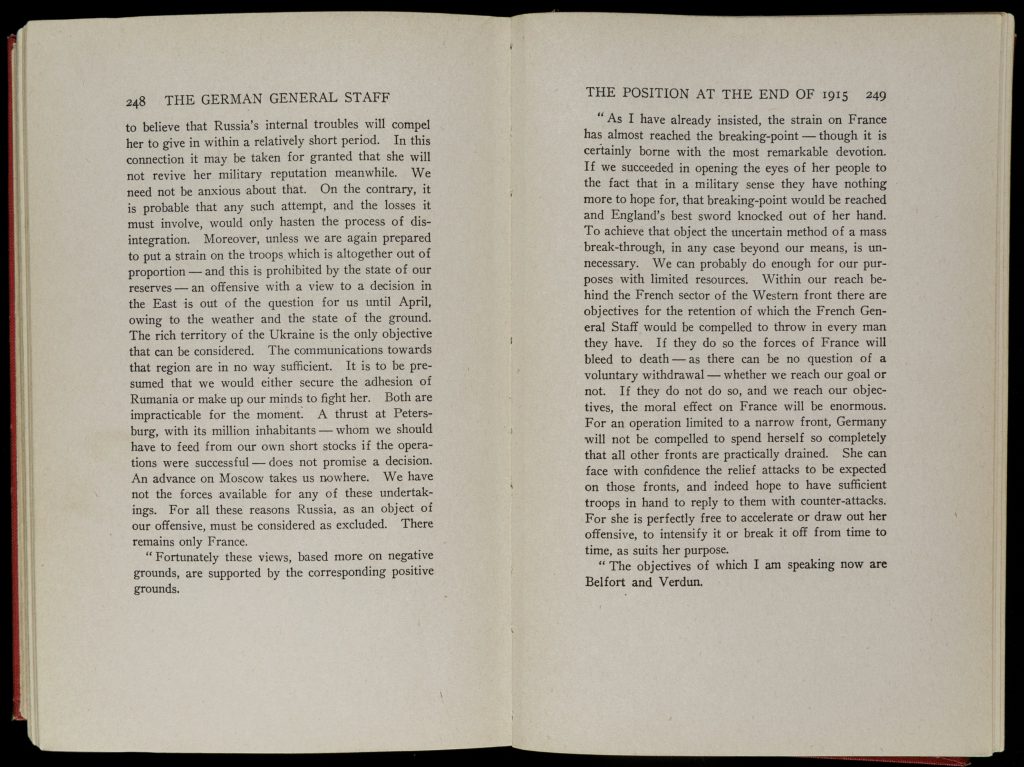

People on both sides questioned the Battle of Verdun’s purpose, conduct, and cost. When the war ended, politicians and generals addressed Verdun and other aspects of the war in their “battle of the books.” Usually the generals defended their actions while the politicians criticized them. Most of these books ignored the experiences of soldiers who fought the campaigns, medical personnel who treated the wounded, and relatives on the home front.

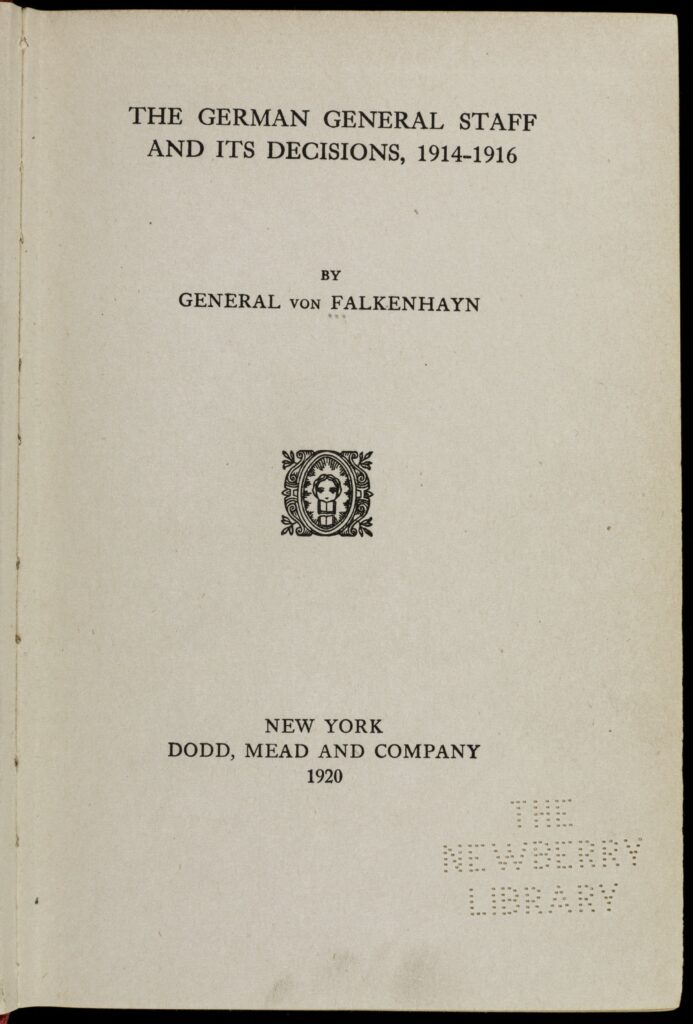

Selection: Erich von Falkenhayn, The German General Staff and its Decisions, 1914-1916 (1920)

In his memoir, selected above, German Chief of the General Staff General Erich von Falkenhayn defended his actions at Verdun. He claimed his goal was never a decisive battlefield victory. Instead, he wanted to “bleed the French Army white.” In other words, he planned to wound or kill as many French soldiers as possible to break the will of the French Army and people. He hoped Verdun would force France to surrender and leave Britain without its major ally.

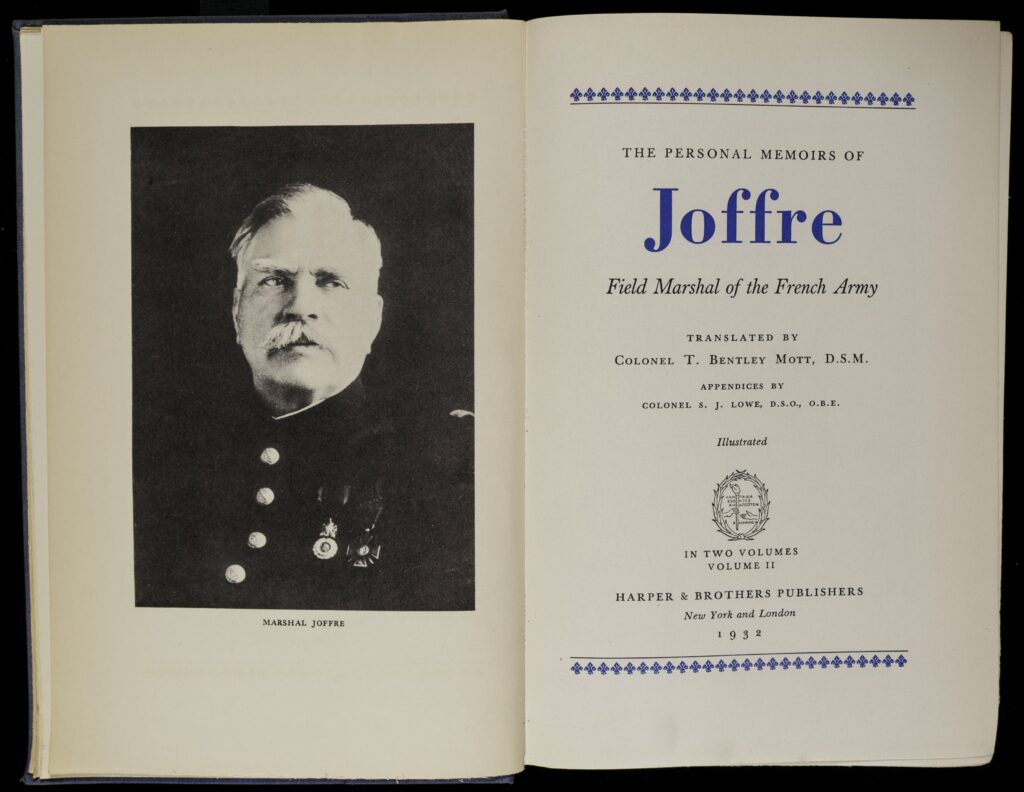

Selection: Joseph Jacques Joffre, The Personal Memoirs, of Joffre, Field Marshal of the French Army (1932)

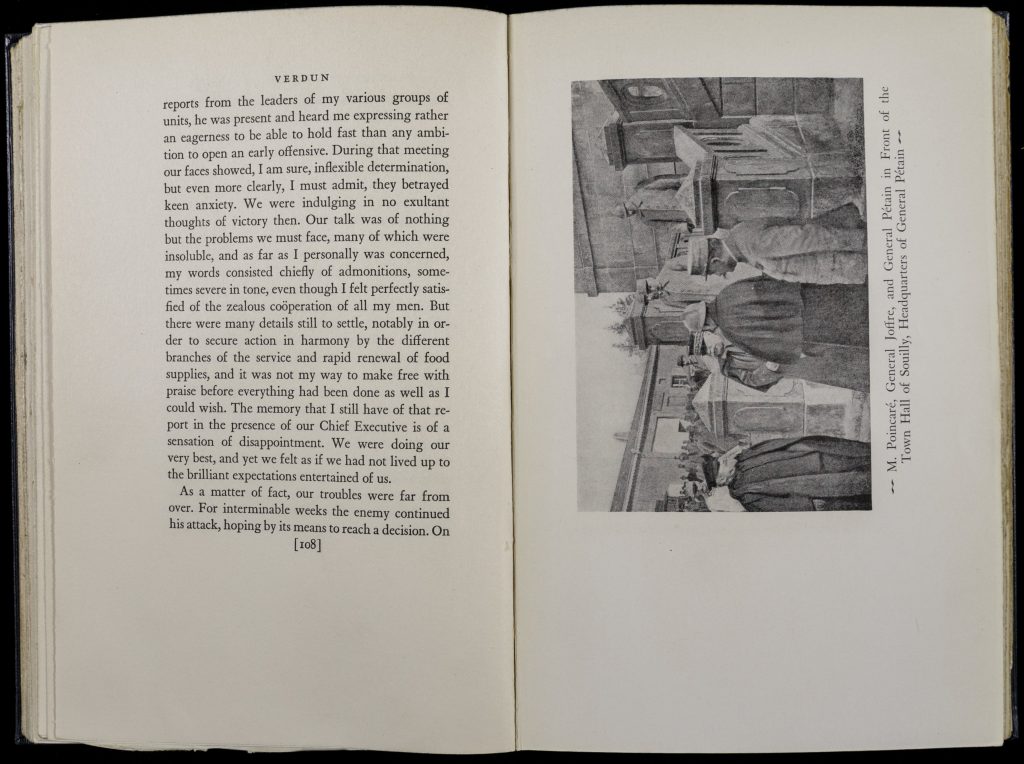

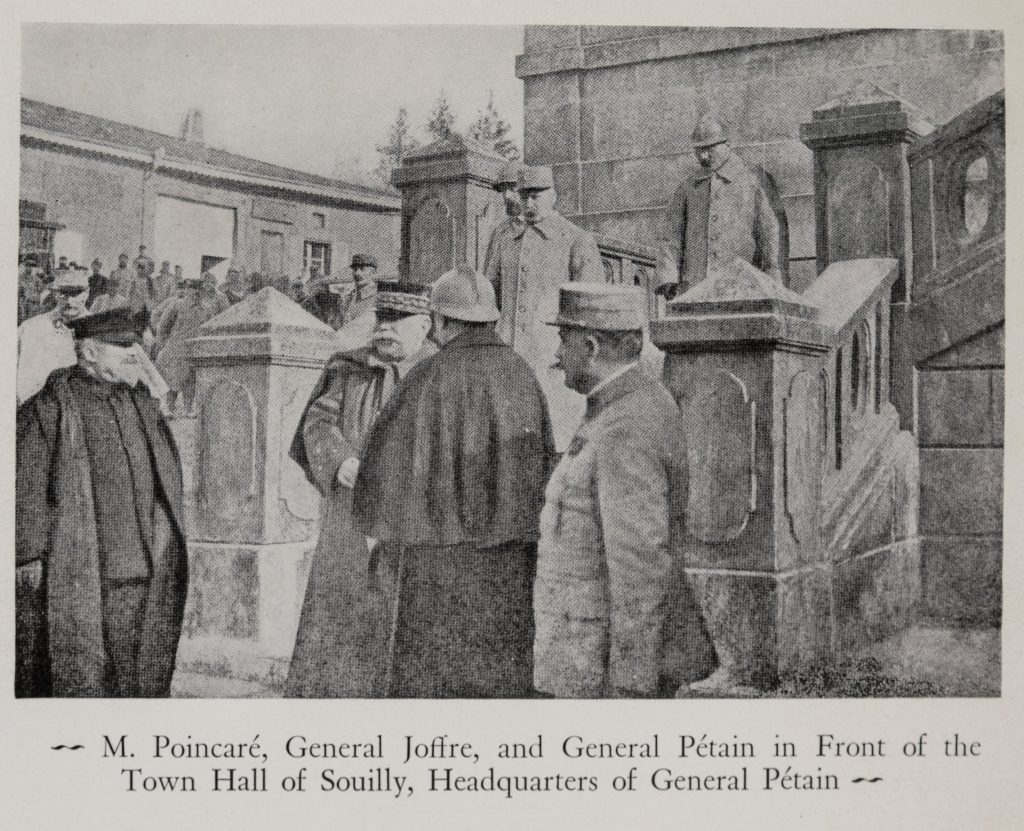

The French Commander-in-Chief, General Joseph Joffre, appointed General Philippe Pétain to lead the French defense at Verdun during the worst of the French losses. Pétain stabilized the lines, reorganized defensive positions, and restored morale. In his postwar memoirs, Pétain was modest about his efforts. He credited his soldiers and staff with securing the successful results and defended his decision not to retreat despite heavy losses.

Selection: Philippe Pétain, Verdun (1930)

Joffre used his memoirs to explain his initial support for Pétain and his later decision to transfer Pétain away from the Verdun. Joffre had transferred Pétain because he refused to initiate counteroffensives at Verdun and release units for the Somme offensive. Joffre’s decision to transfer Pétain was controversial in 1916 and became more so over time. The postwar memoirs of von Falkenhayn, Pétain, Joffre, and others show the ongoing public interest in the war and the continuation of wartime controversies.

Discussion Questions:

- How does Falkenhayn justify his strategy for attacking Verdun in 1916?

- What is Pétain’s rationale for his defensive strategy at Verdun? How does he balance his appreciation of support from Joffre and the French president with his insistence on resisting their views? Does his defensive strategy play into or foil Falkenhayn’s plans? How so?

- How does Joffre describe his relationship with Pétain? What reasons does he give for his views? Does his counteroffensive strategy play into or foil Falkenhayn’s plans? How so?

The War from the Trenches: War Stories in Photos and Poems

During the war generals and politicians dealt with “big picture” issues like strategy, supplies, and discipline. They continued to focus on these themes in their postwar memoirs by defending and attacking others’ wartime decisions. Their books and official military histories usually recreated the movements – or lack thereof – of infantry, artillery, and air forces.

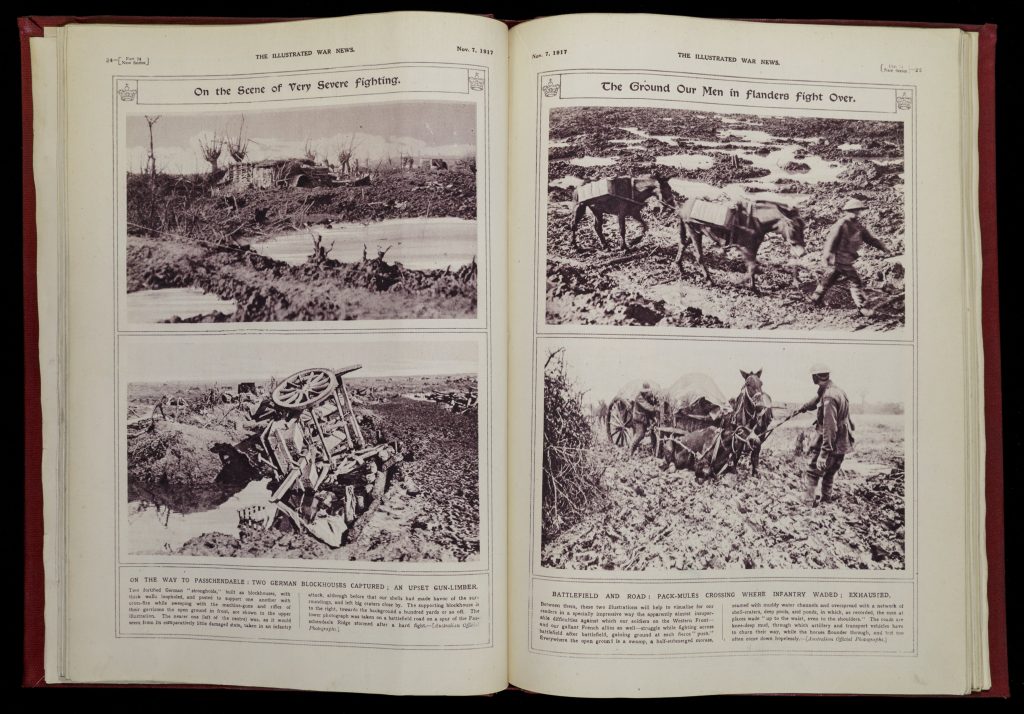

People on the ground wrote about war differently. Most soldiers commented on how the weather and living conditions left them cold, wet, thirsty, hungry, tired, sick, hurt, and emotionally raw. Battles were horrifying, but they offered a break from the boredom of life in the underground trenches.

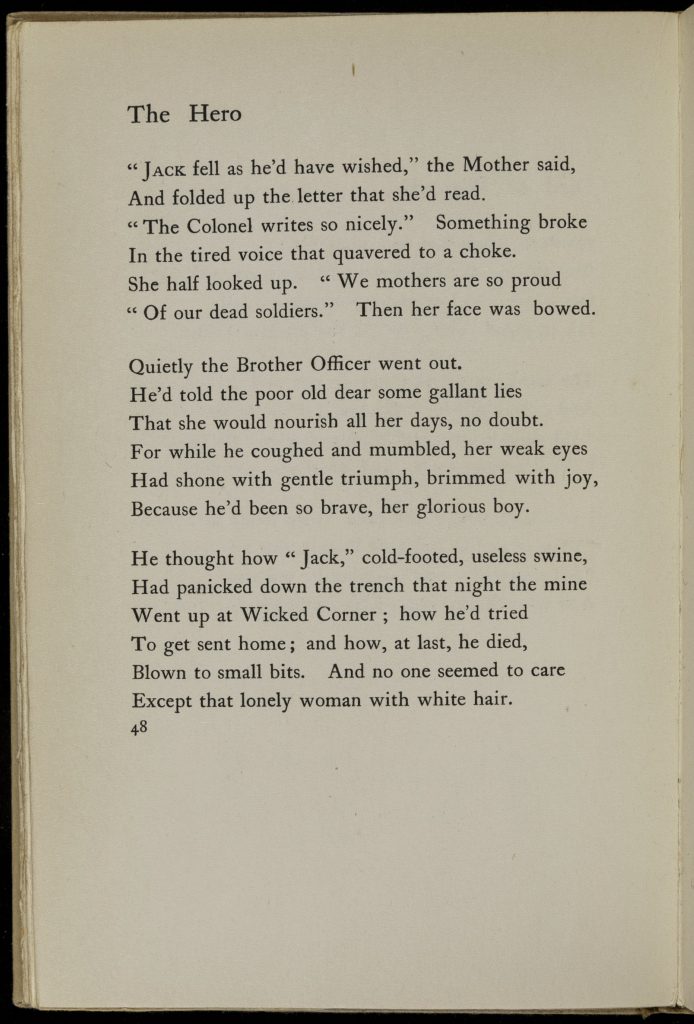

Selection: Siegfried Sassoon, The Old Huntsman and Other Poems (1917)

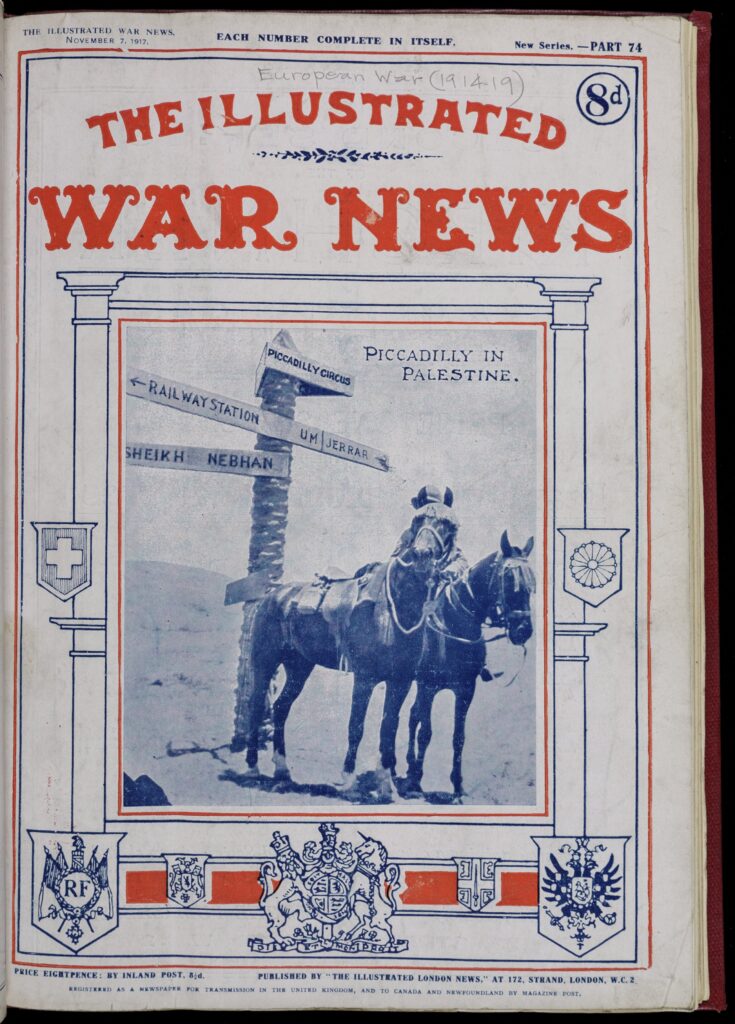

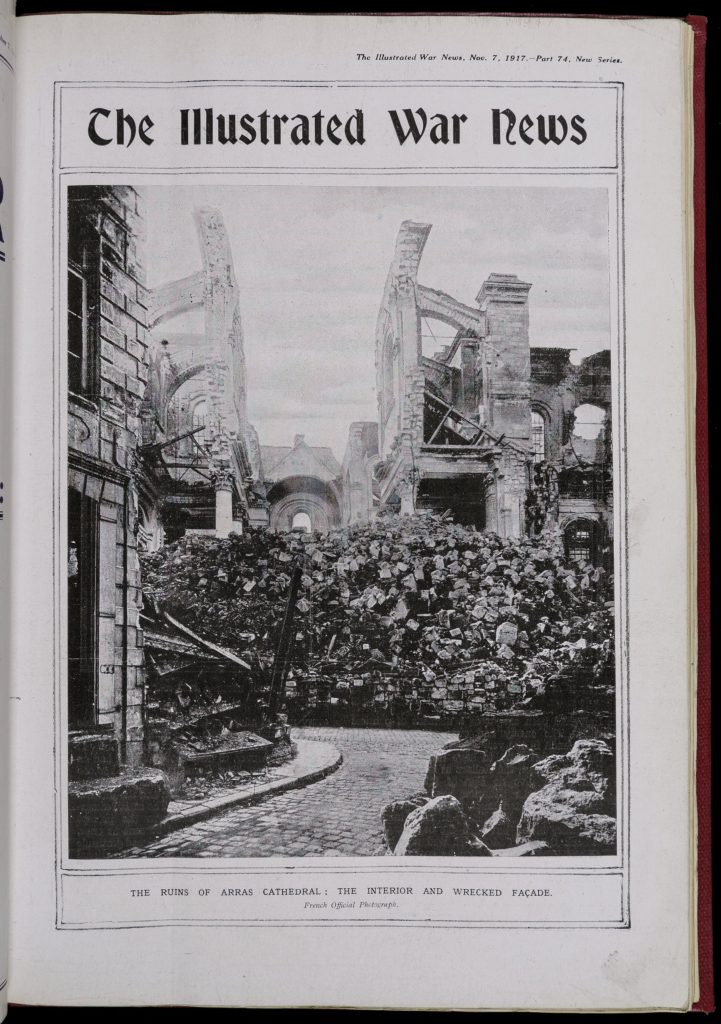

Those at home learned about the war from letters, newspapers, and illustrated magazines. Illustrated magazines were particularly popular because readers could “experience” the war’s battlefields, depots, and factories through their photographs. Although these photographs promised accurate depictions of the front, some of them were censored or even explicitly designed as propaganda. One magazine, the British Illustrated War News, offered both sanitized war images and graphic photographs of battle. The Illustrated War News is an example of the possibilities and limitations of photojournalism during wartime.

Selection: Illustrated London News, Illustrated War News (November 7, 1917)

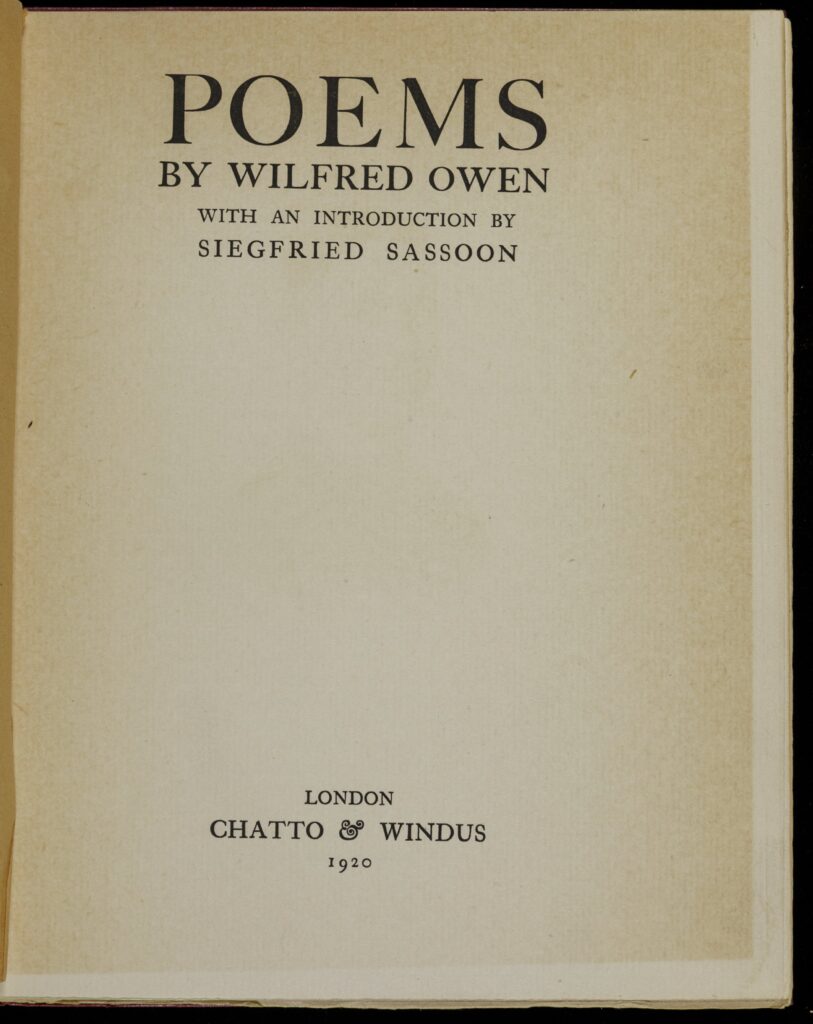

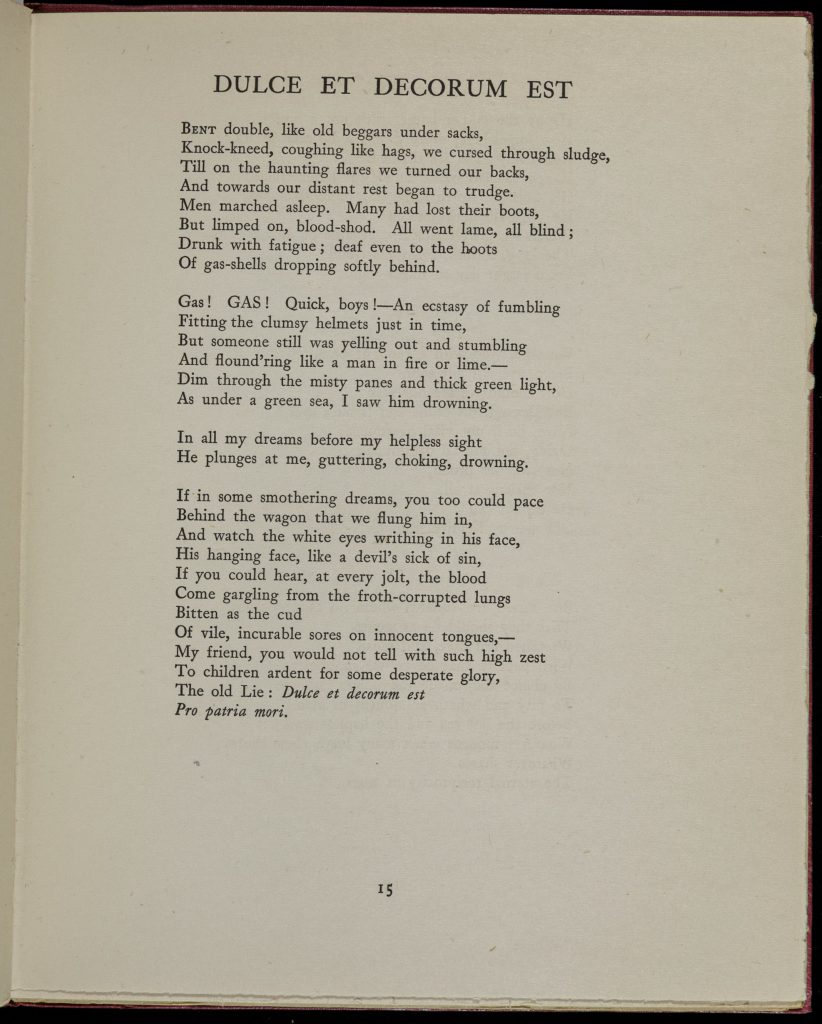

Soldiers and other participants in the war documented it through art and literature. Early war novels focused on acts of heroism and the glories of war. Henri Barbusse’s 1916 novel Le Feu (translated into English as Under Fire in 1917) changed the tone. Under Fire is a gritty, often brutal series of vignettes about a squad of French infantrymen. The book was a literary success and inspired authors like Erich Maria Remarque, Ernest Hemingway, and Siegfried Sassoon to write about the war’s realities. Sassoon was also a poet and encouraged others such as Edmund Blunden, Robert Graves, and Wilfred Owen to publish their poetry. Owen was killed in battle one week before the war ended, and most of his poems were published posthumously. The honesty and brutality of Owen’s work and the tragedy of his death make his poems an important part of the canon of war literature.

Selection: Wilfred Owen, Poems (1920)

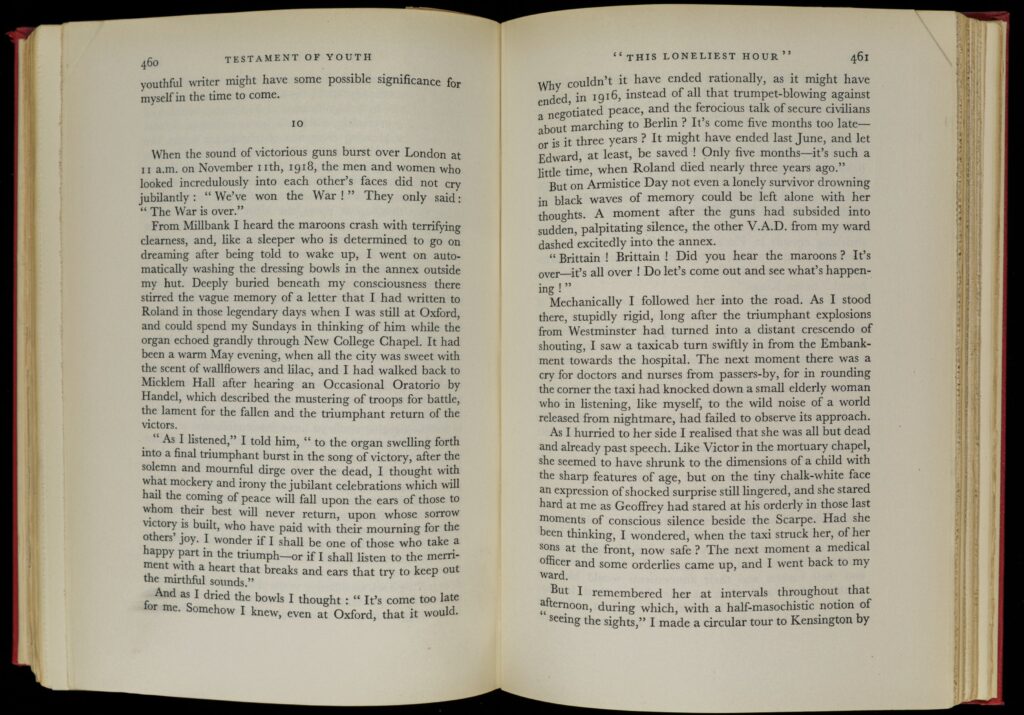

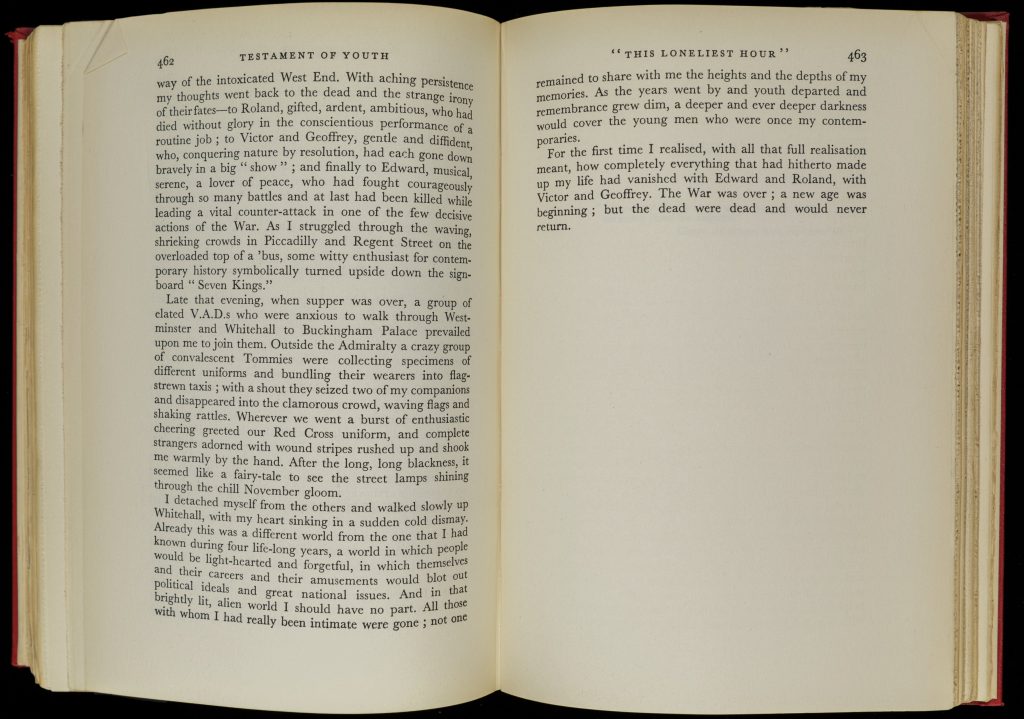

Though women could not enlist and appeared to be on the war’s sidelines, they actively participated as military personnel, relief workers, nurses, factory workers, equipment technicians, and more. They also created works of art and literature about their wartime experiences. Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth, for example, detailed her time as a volunteer nurse and remembrances of her friends.

Selection: Vera Brittain, Testament of Youth (1933)

The photographs from news magazines and the work of authors and poets gave people on the home front powerful visual images and unforgettable literary representations of the war. These works of photojournalism, art, and literature continue to shape our understanding of World War I today.

Discussion Questions:

- How do the pictures and captions in the Illustrated War News help you visualize the conditions on the western front?

- Why might the image of the heroic fallen soldier be important to those who survived the war? How does Sassoon use ironic humor to challenge that image? Why would he want to do so?

- How does Owen challenge the idea that it is sweet and glorious to die for one’s country? Is he effective? Why would he want to expose “the old Lie”?

The End of Conflict: Memorializing War

The end of the First World War came in stages. In 1917, the Bolsheviks, revolutionary communists led by V. I. Lenin, overthrew the Russian government. The revolution seemed to ensure Germany victory on the eastern front, but the county faced widespread food shortages through the winter of 1917-1918. In the spring, German military leadership launched a massive offensive in the west designed to break Allied trench lines before another difficult winter. The offensive pushed the Allies back, but U.S. troops and supplies prevented the Germans from breaking through. In October and November 1918 Germany’s allies signed armistices, legal agreements that temporarily halted fighting during peace negotiations with the Allies. Alone, German leaders signed an armistice with their Allied counterparts that took effect at 11:00 a.m., on November 11. The war was over.

Allied leaders planned to base the peace deal on U.S. President Woodrow Wilson’s “Fourteen Points.” This statement proposed new principles for international conduct, including open diplomacy, freedom of the seas, free trade, disarmament, and the establishment of an international organization to arbitrate future disputes. Allied leaders believed that smaller European groups’ desire for nationhood was a major cause of the war. They hoped that breaking up the Russian, German, Austro-Hungarian, and Ottoman Empires would create new nations, resolve tensions, and prevent future wars. Though the 1919 Versailles Peace Treaty created new states, it did not eliminate European territorial disputes or allow imperial colonies to become independent.

Selection: Rand McNally and Company, Concise Peace Atlas (1919)

The opportunity to “fix” the flawed prewar borders and create a “new” Europe meant reconceptualizing the continent’s map. During the war, maps illustrated battle lines and alliances, charted the movements of armies and navies, and informed the public of new developments. As the peace conference progressed, leaders, diplomats, and members of the public used maps like those in the Rand McNally Peace Atlas to follow the on-going deliberations.

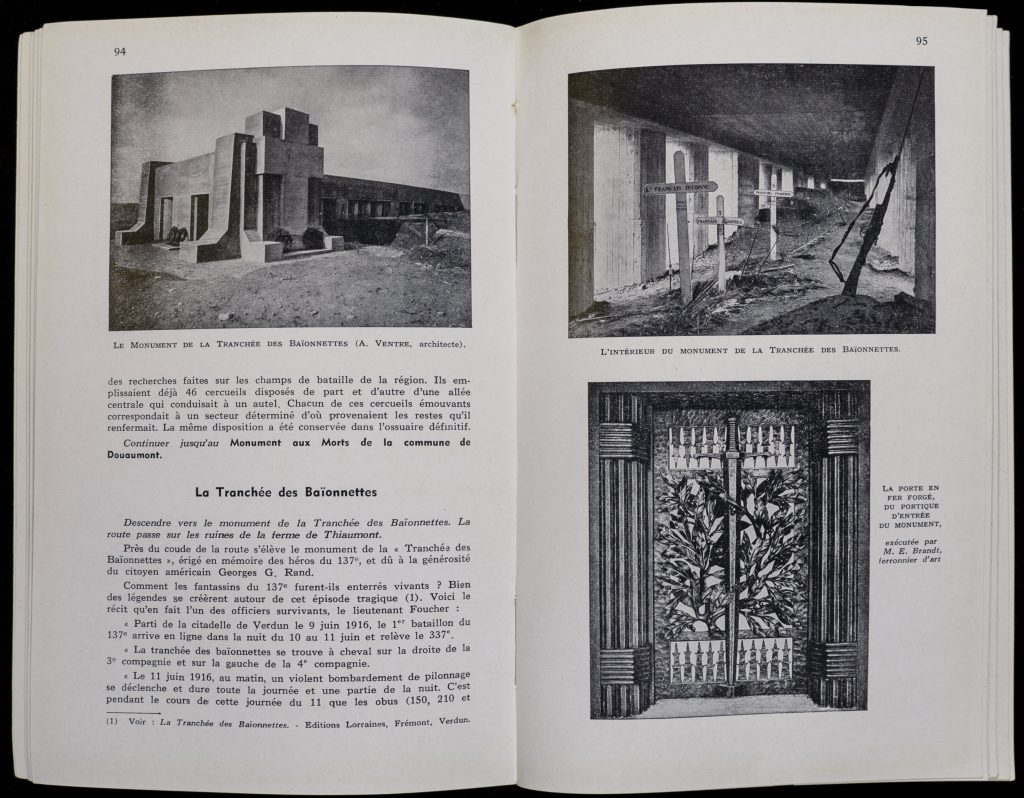

Maps also provided information for those who wished to visit the war’s battlefields. Family members of veterans or of those killed in battle visited the places where their loved ones suffered or died to understand and commemorate them. Others sought out these new historic sites as a form of sightseeing. Maps and travel guides provided useful information for all of these individuals. The Michelin tire company published some of the most important postwar travel guides. Michelin published these guides to promote automobile travel (and their tires), but visitors found their maps, photographs, and battle descriptions to be useful as a means of remembrance of the war.

Selection: Pneu Michelin, Verdun: guide historique illustré (1927)

Vera Brittain, who served as a British volunteer nurse in the war, was one of those who visited memorial sites to honor fallen loved ones. Her memoir, Testament of Youth, is itself a commemorative act. By remembering those she lost to war – a brother, fiancé and two other friends – Brittain provided comfort to others who had suffered loss. While some sought to understand the war by visiting public war sites or memorials, others found peace with books like Testament of Youth in the quiet of their own homes.

Discussion Questions:

- According to the potential map of postwar Europe, what opportunities did the dissolution of Austria-Hungary have for neighboring states like Italy, Serbia, and Romania? What could happen to the Poles, Czechs, and Slovaks of the former empire?

- How does the Trench of the Bayonets convey information and emotion about the soldiers buried there? Why might the memorial be important to the French people today?

- What observations does Brittain make about Londoners’ initial responses to the end of the war? Why is the juxtaposition between the general revelry over the end of the war and her own thoughts so poignant?

- How would readers of the Illustrated War News in 1917 differ in their understanding of the war and the appearances of battlefields compared to sightseers at Verdun using a Michelin Guide in 1928? (Think about the impact of the passage of time, as well as the “reality” of seeing a battlefield in a photograph or in person.)

The Early Course of the War

Once war broke out, governments used propaganda and censorship to shape public opinion in their favor, while newspapers published reports and maps that allowed readers to follow the war and the movement of armies, as these materials demonstrate.

The War from the Top

After the war ended, politicians and generals addressed the Battle of Verdun and other aspects of the war in their “battle of the books,” in which generals often defended their actions while politicians criticized them. These writings largely ignored the experiences of soldiers, medical personnel who treated the injured, and relatives on the home front.

The War from the Trenches

Soldiers and other participants of the war documented their wartime experiences through art and literature, while news magazines published war photographs. These works gave people on the home front powerful images and representations of the war.

Memory and Commemoration

As the peace conference progressed following the end of the war, leaders, diplomats, and members of the public used maps like those in the Rand McNally Peace Atlas to follow the deliberations. Maps and guides, like those published in Verdun, also provided information for those who wished to visit the war’s battlefields to commemorate their killed loved ones or as a form of sightseeing. Works like Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth also capture the personal and collective postwar commemoration and reckoning.

Further Reading

Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane and Annette Becker. 14-18: Understanding the Great War. New York, Hill and Wang, 2002.

Beiriger, Eugene Edward. World War I: A Historical Exploration of Literature. Santa Barbara, CA, Greenwood Press, 2019.

Ferro, Marc. The Great War 1914-1918. London, Routledge, 1995.

Keegan, John. The First World War. New York, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1998.

Strachan, Hew. The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War. New York, Oxford University Press, 2000.

The Great War in History: Debates and Controversies, 1914 to the Present. Edited by Winter, Jay and Antoine Prost, Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press, 2005.