Introduction

What is dissent? What role has dissent played in the development of American democracy? The Oxford English Dictionary helps us begin to answer the first question. The OED defines dissent as “difference of opinion or sentiment; disagreement” and the “opposite of consent.” This document collection encourages teachers and students to elaborate that definition and to develop answers to the second question by examining four case studies in dissent from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These case studies represent four very different forms of dissent: the mass demonstrations and violence of Haymarket, the parades and petitions of the women’s suffrage and anti-suffrage movements, the pamphlets and clinics of Margaret Sanger’s birth control crusade, and the free-speech forums and masquerade balls of the Dill Pickle Club. These case studies, in their variety, allow us to consider the different forms that dissent might take, and the different paths that these movements could follow within national history.

This document collection explores the role of dissent in the development of American democracy through four case studies from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

U.S. historians and political scientists often classify dissident movements along a spectrum from left to right, with the left side encompassing Communists, socialists, and others committed to greater economic and political equality, often achieved through government intervention, and the right side including those who embrace capitalist economics with little or no state regulation. However, these categories become more difficult to define in the area of civil liberties, which both the left and the right claim to embrace. For example, today, the civil rights and reproductive rights movements are both identified with the left, while the gun rights and pro-life movements are both identified with the right. In regard to these movements, neither the left nor the right can be characterized as simply for or against government intervention.

In American Dreamers: How the Left Changed America, Michael Kazin identifies two axes through which to interpret the history of leftist dissent in the United States. One axis concerns the relationships—and differences—between the political left and the cultural left. By political left, Kazin refers to movements and individuals, which advocate significant changes to national laws and, even, to the structure of government. Examples from this document collection include the Workingmen’s Party platform and the suffragists’ efforts to change voting laws. By cultural left, Kazin means the more amorphous, and often more widely accepted, set of artistic and literary practices that express dissent from prevailing cultural norms. Examples from this collection include the Dill Pickle Club records of “bohemian” life. As Kazin notes, there are plenty of moments when political and cultural activity intersect, however there are also many moments when they diverge and, as historians, it is useful to be able to distinguish between them. The second axis that Kazin identifies describes a tension within the goals of leftist movements, whether they are primarily political or cultural. That tension lies between, on the one hand, the desire to extend or protect individual liberties and, on the other hand, the desire to achieve social equality and justice. There are times when achieving collective good seems to require the sacrifice of individual freedoms and vice versa. Although Kazin writes specifically of the left, his terms provide a useful framework for many of the documents presented here and can help us formulate terms and questions for right-wing as well as left-wing movements.

Please consider the following questions as you review the documents

- Develop a definition of dissent based on your reading of these documents. What do the documents have in common? How does the concept of dissent allow us to bring together documents that are, in many ways, quite different?

- What forms has dissent taken in U.S. history? What are the objectives of the writers and organizations represented in these documents? In what ways do they dissent from the political and social conditions of their times? What are their methods for advocating change? What are their relationships to mainstream American politics and culture?

- What is the role of dissent in a representative democracy such as the United States? Why have groups of Americans chosen to go outside of official channels (e.g., elections) in order to try to reform government and society? How have traditions of dissent changed the ways that Americans practice democracy?

- In what ways does the pursuit of individual liberty conflict with the quest for social equality and justice? In what ways are these goals compatible?

Mass Demonstrations and Violence: The Haymarket Affair

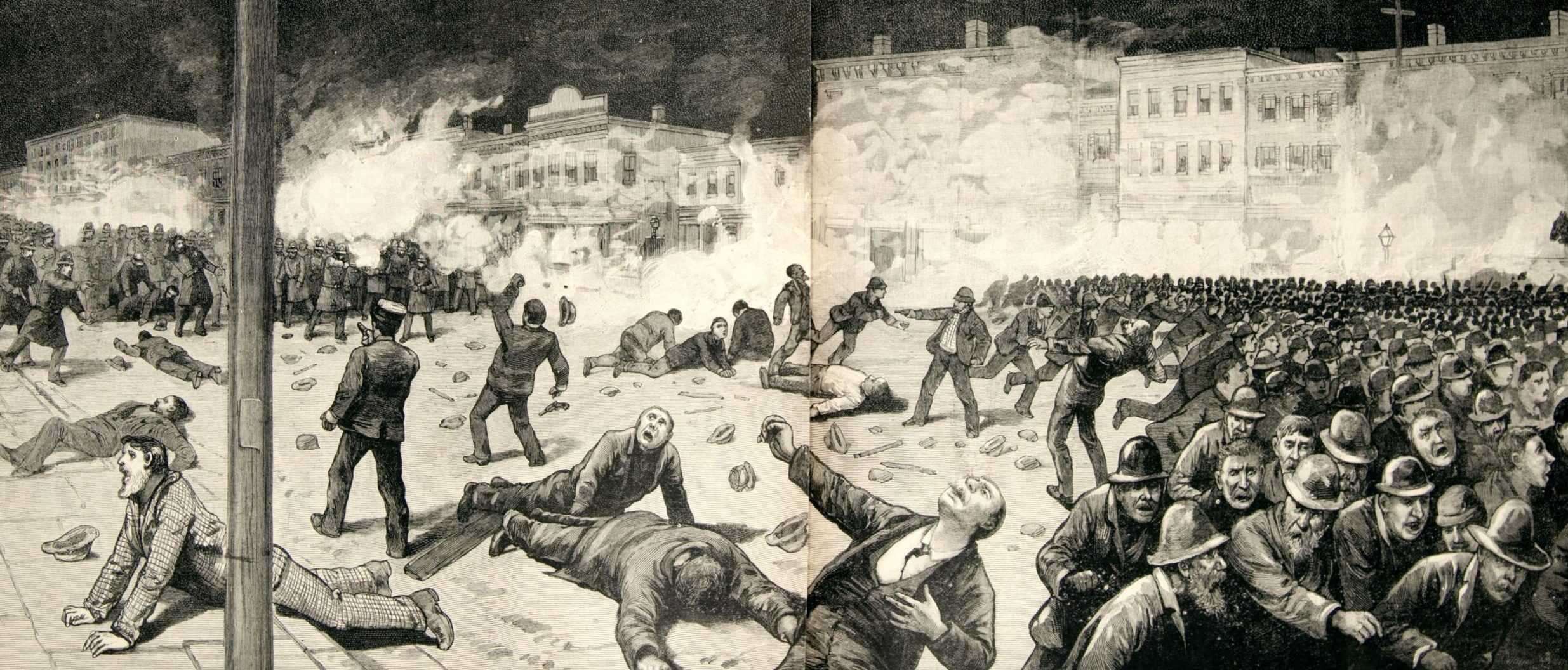

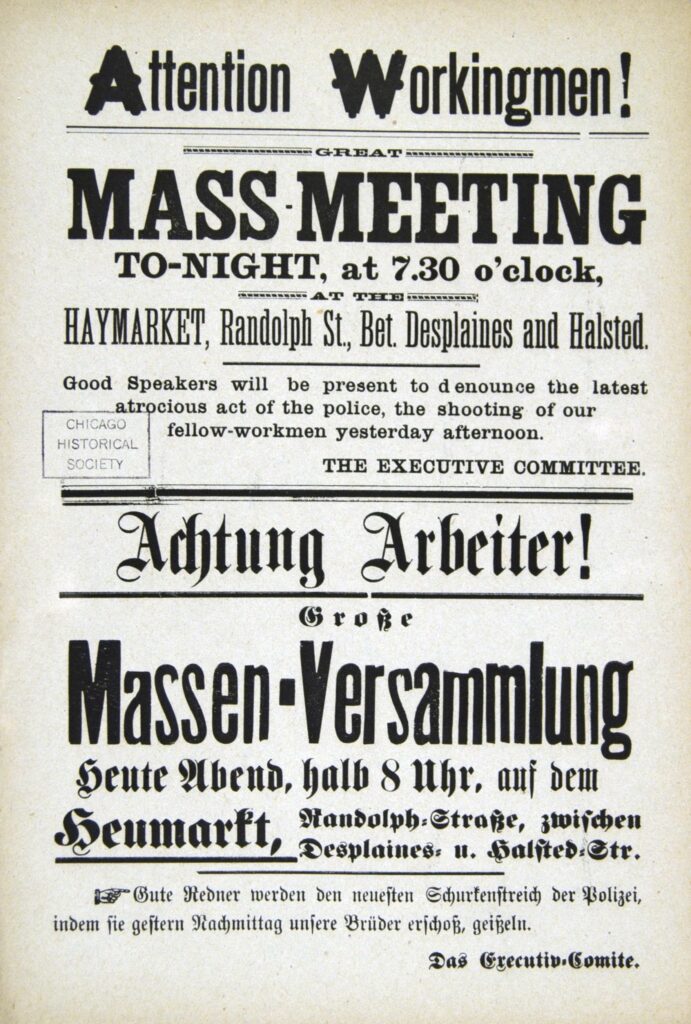

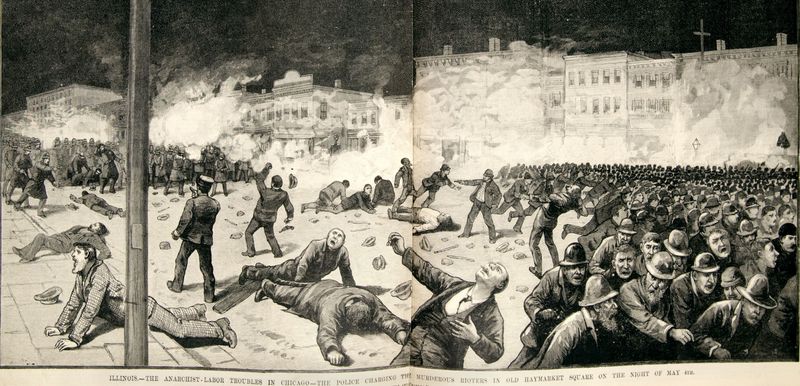

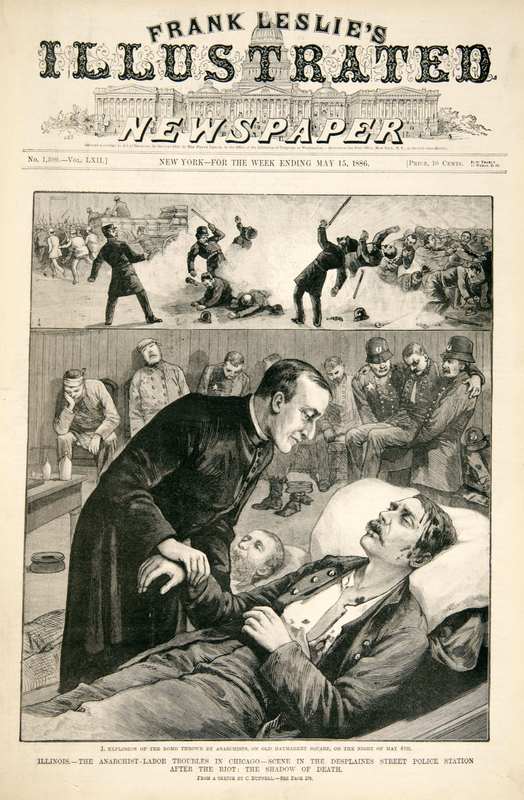

Nineteenth-century employers often expected workers to spend 12 to 14 hours a day, six days a week on the job. In the 1880s, anarchists, unionists, socialists, and reformers organized a national effort to demand an eight-hour workday. During the first week of May 1886, 35,000 Chicago workers walked off of their jobs in massive strikes to protest their lengthy work weeks. Some of these strikes involved violent skirmishes with the police. At least two strikers were killed on May 3. In response, the next evening, roughly 1,500 people gathered at the West Randolph Street Haymarket, a market on the edge of the city where people bought hay for their horses.

Although the May 4 rally featured fiery speeches from the city’s leading anarchists and labor leaders, it was a peaceful gathering. As the rally drew to a close, hundreds of policemen moved in to disperse the crowd. Someone threw a bomb at the police brigade, killing one officer instantly. The police responded with a barrage of bullets. An unknown number of demonstrators were killed or wounded. Sixty police officers were injured and eight eventually died. Politicians and the press blamed anarchists for the violence. Although there was no evidence linking specific people to the bomb, eight men were convicted of murder on the basis of their political writings and speeches. Four men were executed; one committed suicide. The trial was later considered grossly unjust and, in 1893, the Illinois governor granted absolute pardon to the three, remaining imprisoned defendants. The labor organizations, however, were severely damaged and the anarchist movement never recovered from the trial.

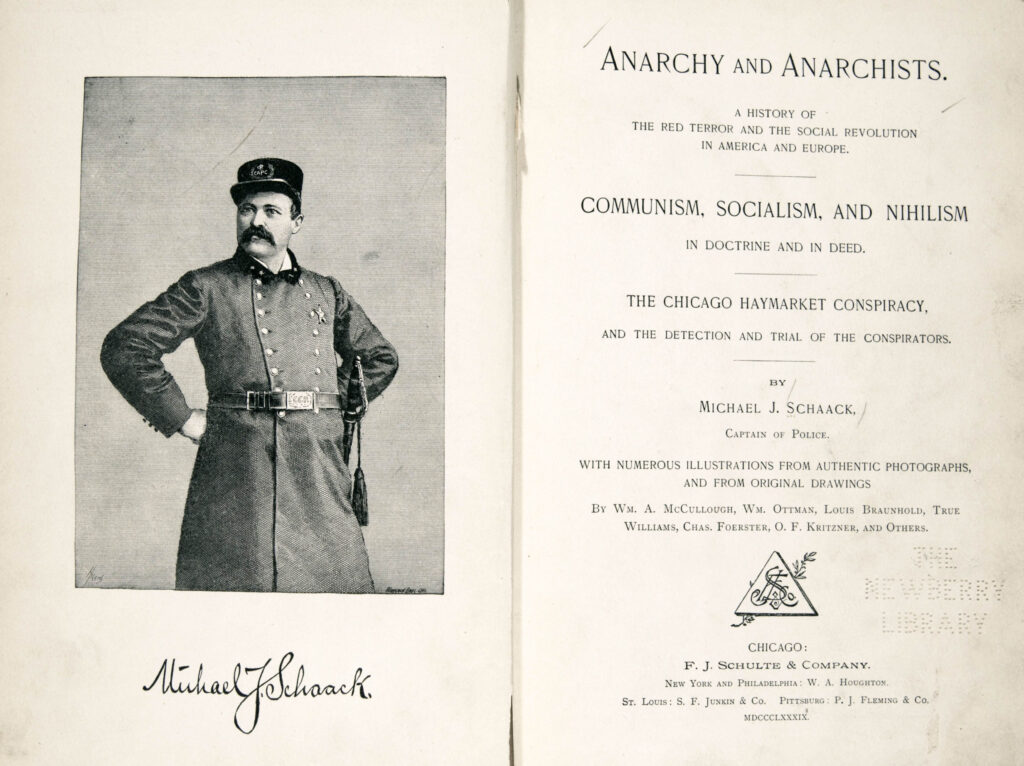

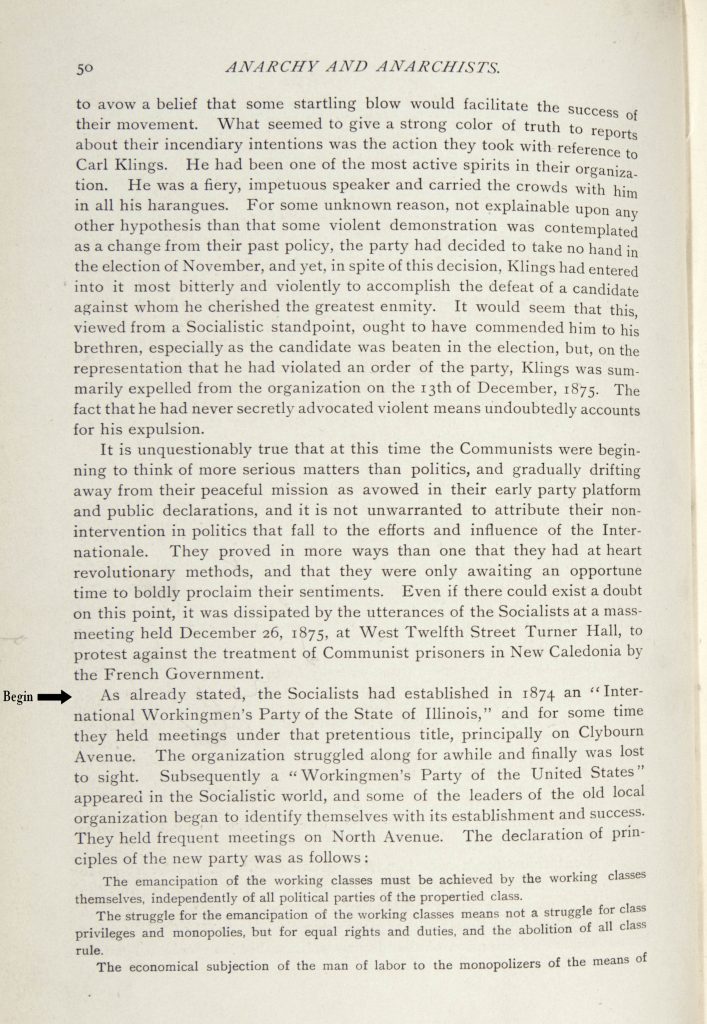

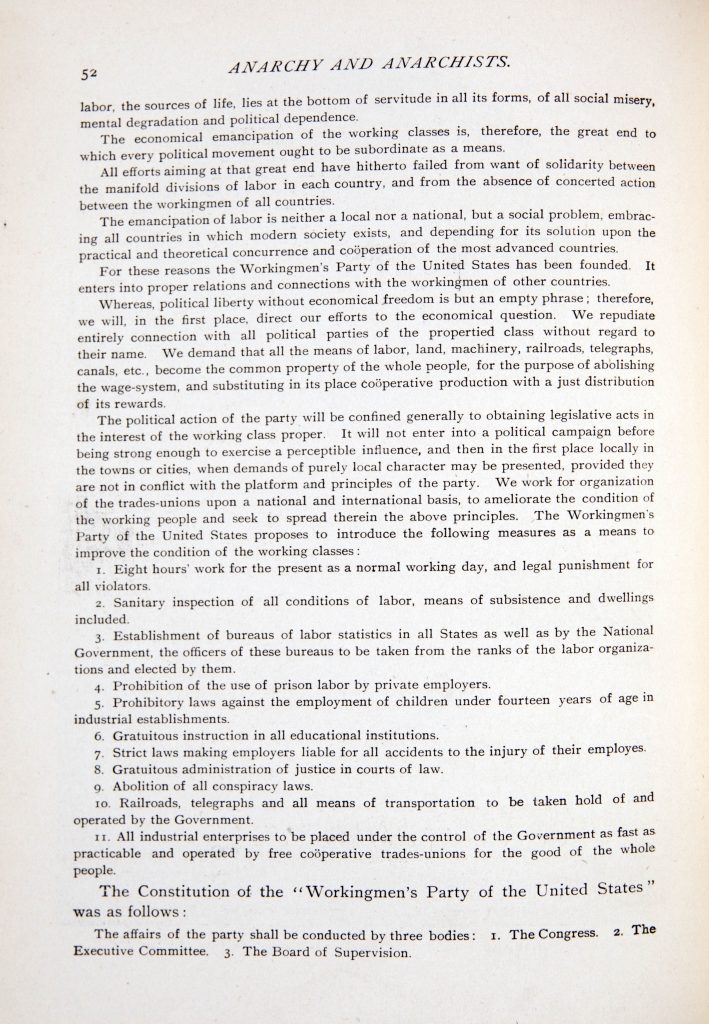

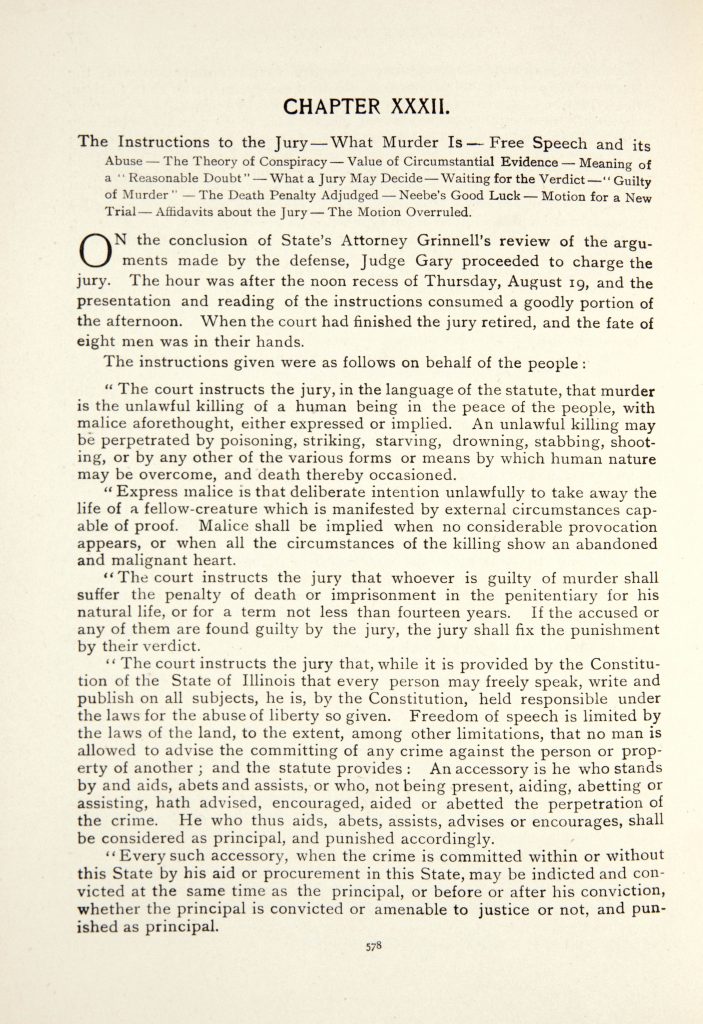

The documents in this section include representations of the Haymarket events in a New York newspaper and passages from a history written by Captain Michael Schaak. Schaak commanded a Chicago Avenue police station in 1886 and played a large role in the arrests and prosecutions of anarchists following the Haymarket violence. Schaak included in his book the published principles and constitutions of several radical parties, such as the Workingmen’s Party of the United States, excerpted below. He also reproduced Judge Joseph E. Gary’s instructions to the jury, or guidelines on reaching a verdict.

Selection: Michael J. Schaak, Anarchy and Anarchists: A History of the Red Terror and the Social Revolution in America and Europe, title page and frontispiece, 50, 52, 578 (1889).

Questions to Consider

- Examine the broadside advertising the Haymarket rally. What can you learn about the rally’s audience and purpose from this broadside?

- Examine the illustrations of the Haymarket events from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. How did this newspaper portray the events to a national audience? Do the illustrations encourage readers to sympathize with the police or the demonstrators? On what grounds?

- What are the principles and goals of the Workingmen’s Party, as outlined in this document? Which, if any, of their goals do you consider reasonable? Which, if any, do you consider unreasonable?

- How does the judge instruct the jury to consider the constitutional right to freedom of speech? What are the limitations on this right, according to the judge? How does he define accessory? To what extent does he consider accessories culpable for a crime?

- Does Schaak’s position as police chief appear to affect his presentation of the issues and events?

Parades and Petitions: Women’s Suffrage

In 1920 the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution granted the right to vote to women throughout the United States. The amendment represented the culmination of a long and uneven campaign to achieve women’s suffrage. Women had not possessed the right to vote (or, for the most part, to own property) under British colonial rule and, following the American Revolution, federal and state governments kept those restrictions in place. (The one exception was New Jersey, which allowed women to vote until 1807, when an amended voting law barred them.) A persistent, if small, minority advocated for women’s suffrage throughout the first half of the nineteenth century and gained prominence with the 1848 Seneca Falls convention on women’s rights. However, the suffrage movement stalled during the Civil War and, afterwards, split over support of the Fifteenth Amendment, which extended suffrage to African American men, but not to any women. The movement overcame its divisions in the late 1880s and moved forward through the following decades by pursuing both state and federal reform. Residents of Illinois saw the results of this incremental approach: in 1891, the Illinois state legislature granted women the right to vote in school elections and, in 1913, it extended this right to presidential and local elections.

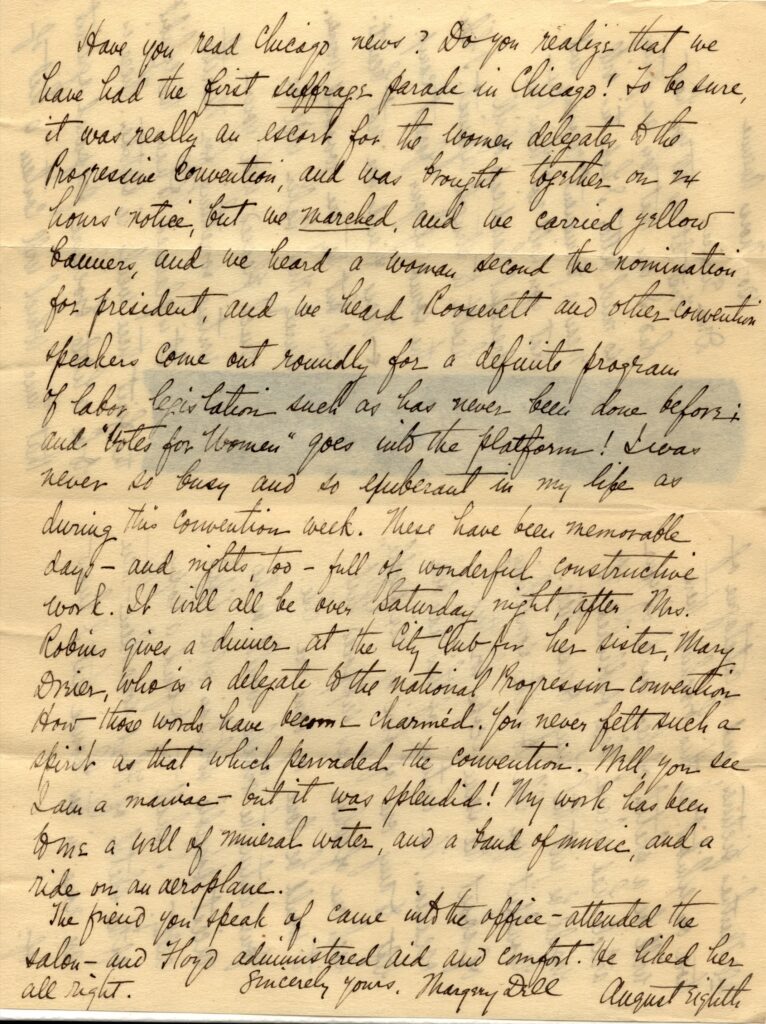

Transcription of Currey’s letter:

Have you read Chicago news? Do you realize that we have had the first suffrage parade in Chicago! To be sure, it was really an escort for the women delegates to the Progressive Convention, and was brought together on 24 hours’ notice, but we marched, and we carried yellow banners, and we heard a woman second the nomination for president, and we heard Roosevelt and other convention speakers come out roundly for a definite program of labor legislation such as has never been done before; and “Votes for Women” goes into the platform! I was never so busy and so exuberant in my life as during this convention week. These have been memorable days—and nights, too—full of wonderful constructive work. It will all be over Saturday night, after Mrs. Robins gives a dinner at the City Club for her sister, Mary Dries, who is a delegate to the National Progressive Convention How those words have become charmed. You never felt such a spirit as that which pervaded the convention. Well, you see I am a maniac—but it was splendid! My work has been to me a well of mineral water, and a band of music, and a ride on an aeroplane.

The friend you speak of came into the office—attended the salon—and Floyd administered aid and comfort. He liked her all right.

Sincerely yours,

Margery Dell

August Eighth

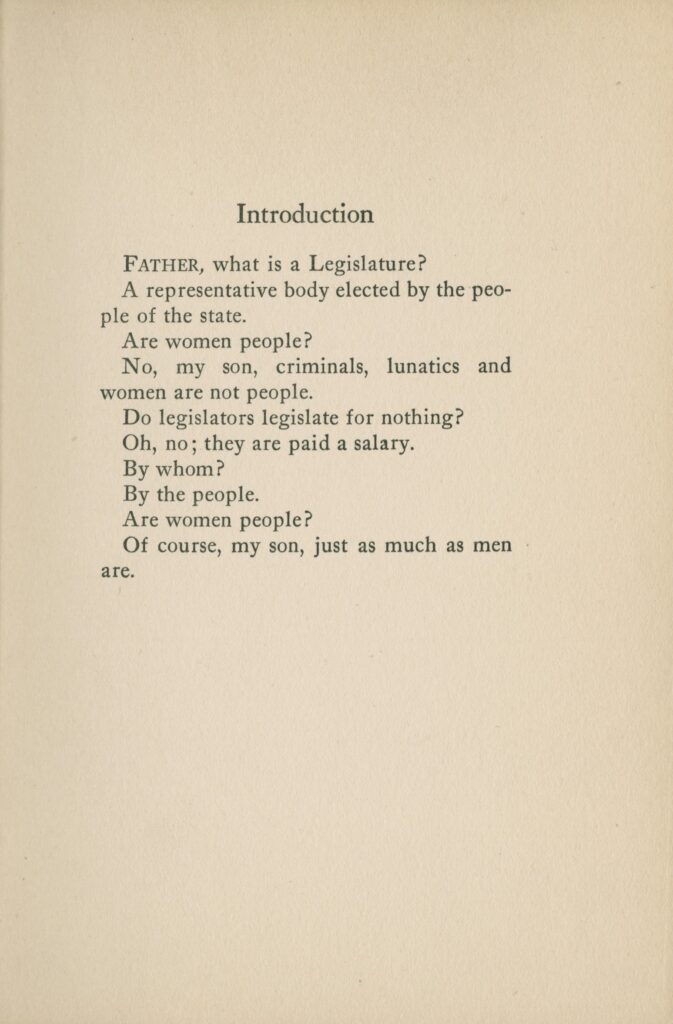

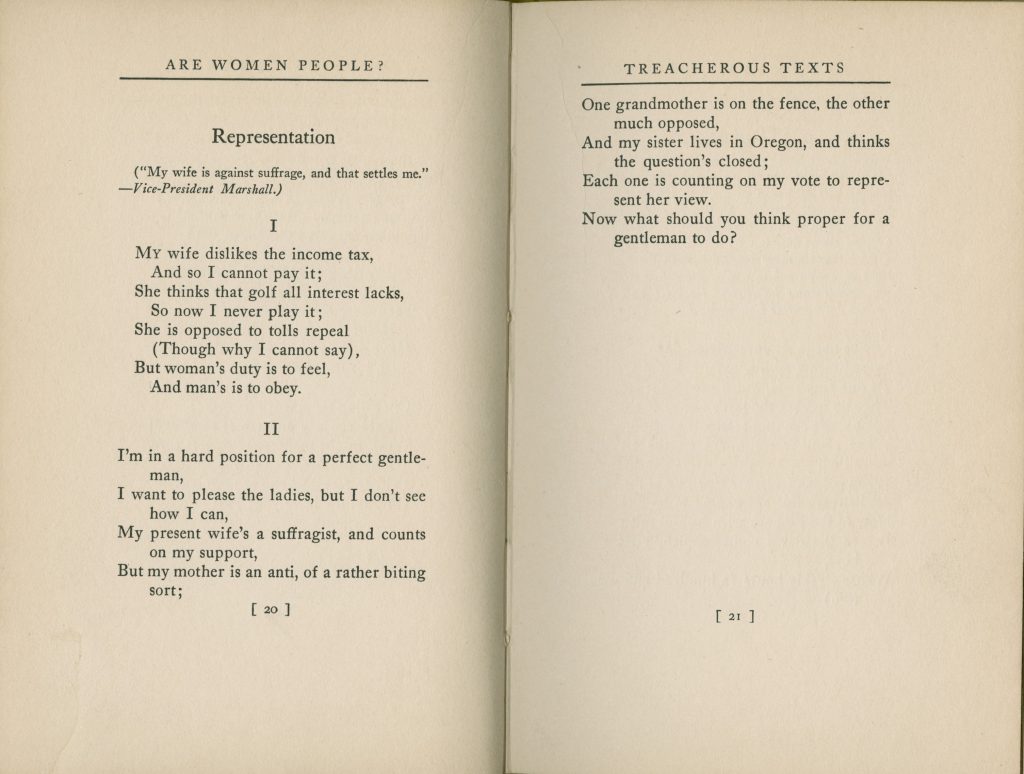

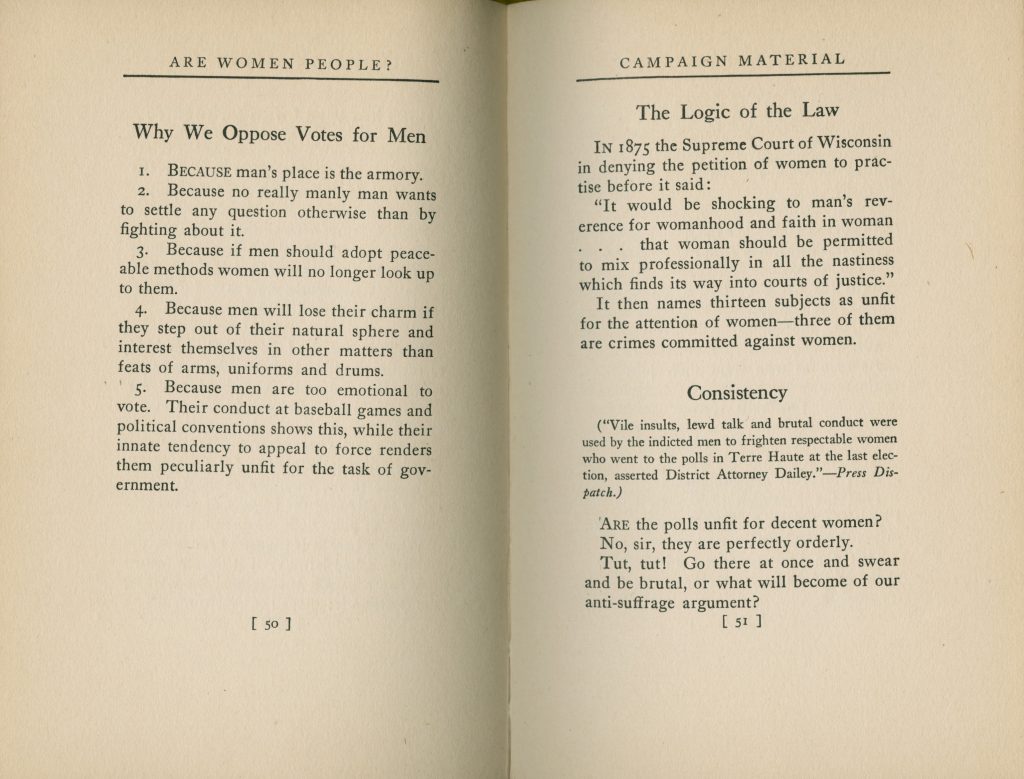

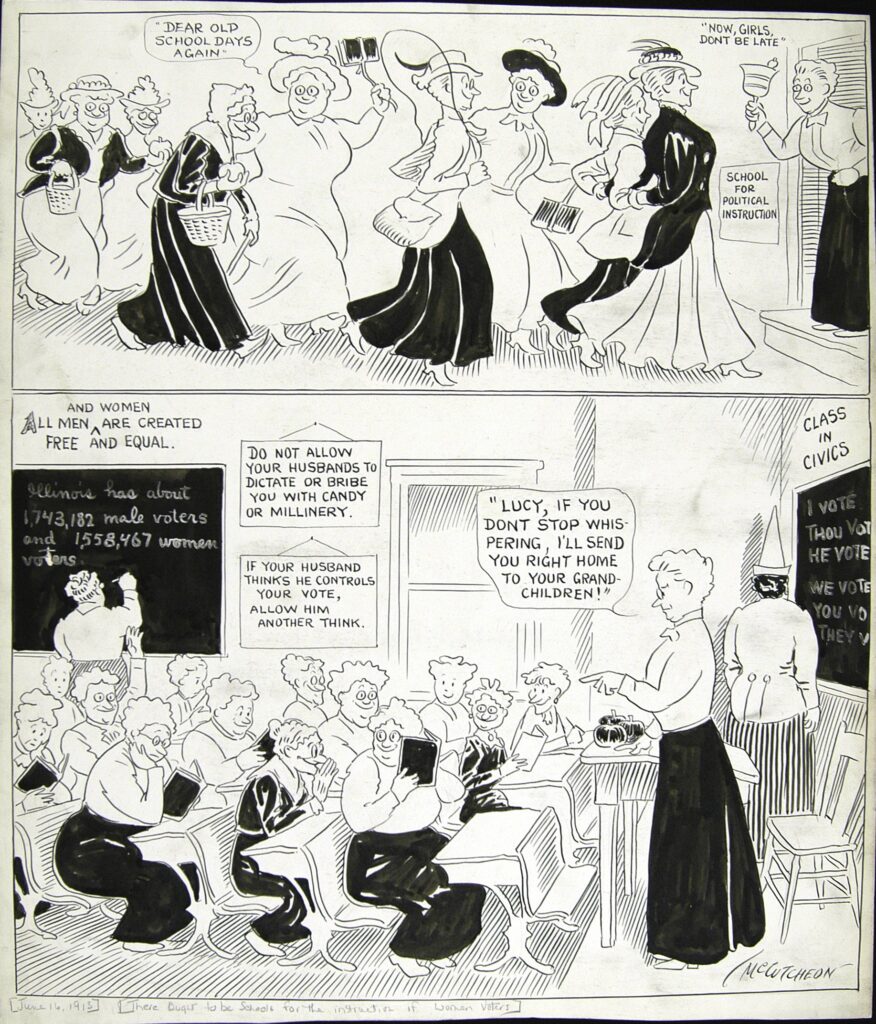

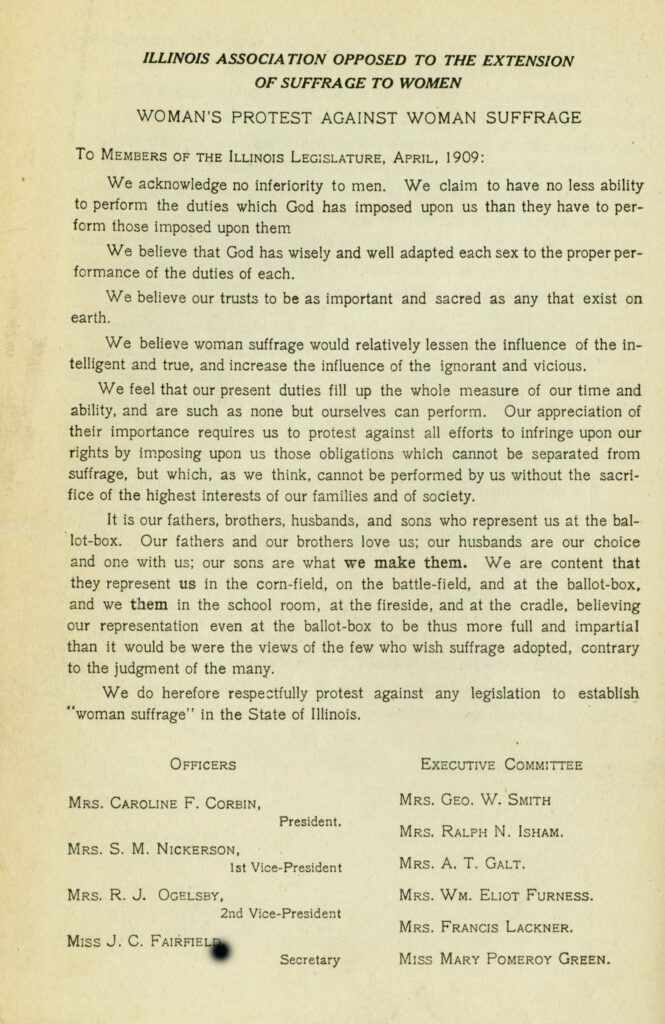

The documents in this section represent both pro- and anti-suffrage positions. Chicago novelist Caroline F. Corbin led the fight against suffrage in Illinois. She established the Illinois Association Opposed to the Extension of Suffrage to Women (IAOESW) in 1897 and, in this 1909 letter to state legislators, makes the case against suffrage. On the other side of the debate, Margery Currey writes to her friend Eunice Tietjens about marching in a suffrage parade during the Progressive Party convention in August 1912. (Former U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt had formed the Progressive Party that summer after losing his bid for the Republican Party presidential nomination. Roosevelt agreed, with some reluctance, to support women’s suffrage in his campaign. But in any case, he lost the election to Democrat Woodrow Wilson.) The cartoon by John T. McCutcheon appeared in the Chicago Tribune five days after the Illinois House of Representatives approved women’s suffrage in Illinois. Finally, Alice Duer Miller’s book of poetry Are Women People? featured work that she had published the previous year in the New York Tribune. Miller skewered the self-proclaimed populism of President Wilson and others who professed a commitment to representative democracy yet opposed women’s enfranchisement.

Selection: Alice Duer Miller, Are Women People: A Book of Rhymes for Suffrage Times, Introduction, “20-21, 50-51 (1915).

Questions to Consider

- What reasons do the anti-suffrage petitioners give for opposing women’s suffrage? What do they fear will be the consequences of extending the vote to women?

- Describe Currey’s account of marching in the suffrage parade. What is her tone? What made the experience so significant and, in her words, “splendid”?

- Examine McCutcheon’s cartoon. What makes the cartoon funny? What arguments does the cartoon implicitly present?

- How does Miller make the case for women’s suffrage in her poems? What is her tone?

- Compare the different forms of political dissent represented by these documents. Which do you find most effective? Why are they effective?

Pamphlets and Clinics: Margaret Sanger’s Birth Control Crusade

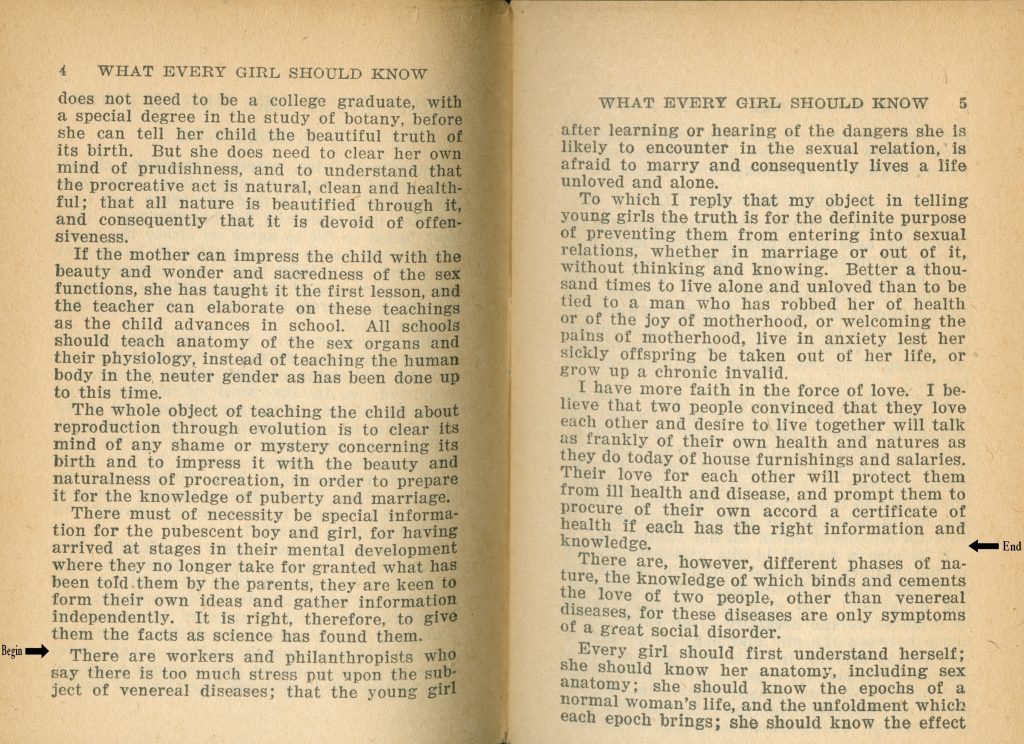

Margaret Sanger led the twentieth-century movement to make birth control and sex education legal and accessible to women in the United States. Sanger was born in New York State in 1879. At that time, the Comstock law (1873) made it a federal crime to distribute or sell birth control devices or to send information about birth control through the mail. The law was named for Anthony Comstock, a devout Christian who was appalled by the amount of prostitution in New York City following the Civil War. Comstock argued that birth control led to promiscuity and, therefore, should be banned. Sanger reached the opposite conclusion. She watched her mother suffer and eventually die from the physical toll of eleven childbirths and seven miscarriages. When she later became a nurse in New York City, she saw countless other women experience similar physical and emotional problems due to unwanted pregnancies. To Sanger, a woman’s right to determine whether and when she became pregnant was a fundamental condition of her freedom and humanity.

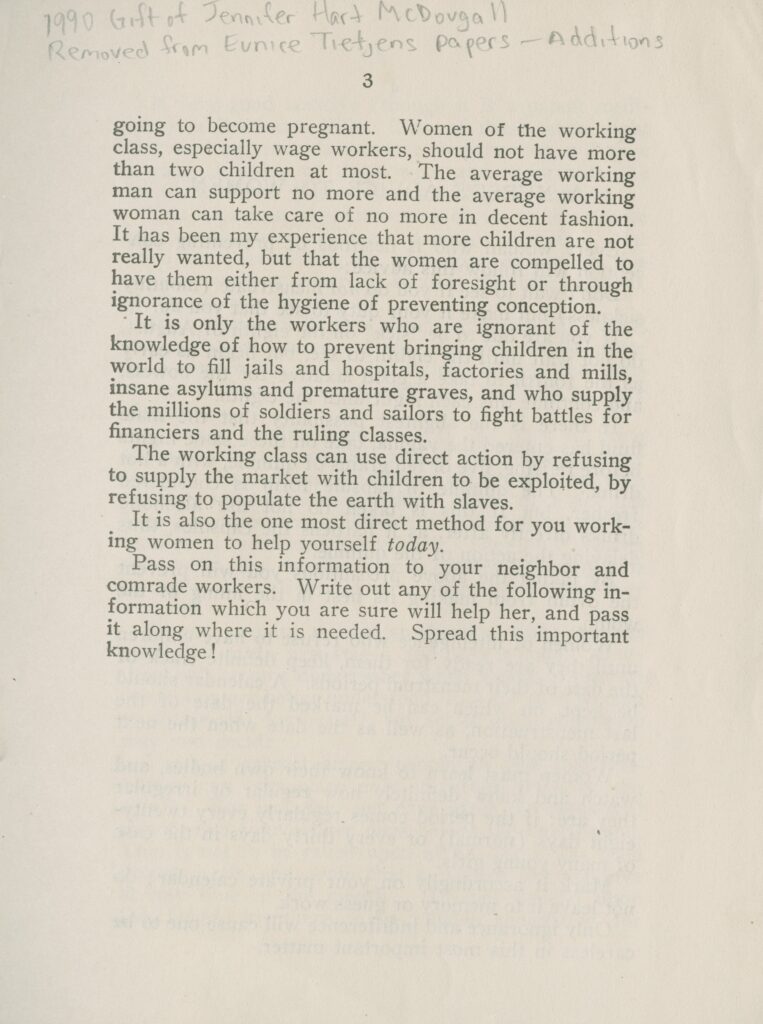

In the 1910s, Sanger published a series of essays on reproduction and birth control and found herself indicted for obscenity. Those charges were eventually dropped. So Sanger pushed the envelope further by opening a clinic in Brooklyn to instruct women in the use of contraceptives. Neighborhood women, mostly Italian and Jewish immigrants, many accompanied by their children, formed long lines down the sidewalk. In nine days, the police had shut down the clinic and arrested Sanger on charges of distributing contraception. She was sentenced to 30 days in the county penitentiary. Over the following decades, Sanger continued her campaign to legalize birth control and sex education in the United States and abroad. Her organization eventually became Planned Parenthood. The Comstock law remained in effect until 1965, when the Supreme Court’s decision in Griswold v Connecticut made birth control legal for married couples. Sanger died the following year. The Court declared the remaining provisions of the Comstock law unconstitutional in 1983.

Sanger’s birth control crusade offers an example of dissent that does not fit neatly into the familiar political spectrum. Sanger was a Socialist. However, historian Jill Lepore argues that her campaign to legalize birth control and promote sex education was not, during her lifetime, primarily identified with either the left or the right. It had supporters as well as critics from both the Democratic and the Republican parties. Only in the 1980s, when the legalization of abortion became a defining issue for both Republicans and Democrats, did birth control and sex education become consistent targets of conservatives. Right-wing groups have recently vilified Sanger as promoting eugenics, the now discredited, often racist, science of improving the human race through breeding. Sanger did entertain some eugenics ideas, but she denounced Nazi eugenics programs and insisted that individuals—not the state—should have the power to make reproductive choices. During her lifetime, Sanger enjoyed the support of many members of the African American and immigrant communities. African American leaders invited her to open a clinic in Harlem in 1929 and both W. E. B. DuBois and Martin Luther King endorsed her work.

Questions to Consider

- Why does Sanger believe that it is important for women to have accurate information on reproduction, birth control, and venereal disease? What relationships does she perceive between birth control and women’s freedom?

- Why does Sanger believe that working women should not have more than two children? How is economic class relevant to the issue of birth control?

Bohemian Culture: The Dill Pickle Club

The Dill Pickle Club was established by the labor activist Jack Jones around 1914 on Chicago’s Near North Side. It was a social club in the broadest sense of the term, by turns coffeehouse, nightclub, lecture hall, art gallery, and performance space. The club hosted lectures and debates (some serious, some not), concerts and plays, dances and parties. It attracted free-thinking, nonconformist artists and intellectuals known as Bohemians. (The term Bohemian comes from the association of “gypsies,” or Romani people, with an anti-establishment, vagabond life and with the Eastern European region of Bohemia, now part of the Czech Republic.) The Dill Pickle Club was not an elite or exclusive environment, but instead offered patrons the thrill of meeting people from different economic, educational, ethnic, and racial backgrounds. Socialites could mingle with factory workers, professors with activists, writers with prostitutes.

The Dill Pickle was not alone in promoting nonconformist thought and expression; rather, it was one of about 200 free-speech forums that flourished in Chicago during the first half of the twentieth century. A random selection of lecture titles from the 1910s and ‘20s gives a sense of the club’s wide-ranging topics: “Is Jazz Better than Opera?” “Is Monogamy a Failure?” “Nuts I Have Known,” “Evolution and Revolution,” “Who’s Responsible for the Depression,” “Why Bolshevism Succeeded in Russia.” Some of these lectures were given by local professors and doctors, others by popular nonacademic speakers, such as attorney Clarence Darrow and anarchist Emma Goldman. The club was popular with celebrated writers such as Sherwood Anderson, Carl Sandburg, and Ben Hecht. However, the Dill Pickle struggled to survive the Great Depression and closed in the mid-1930s under pressure from tax auditors and moralists.

Questions to Consider

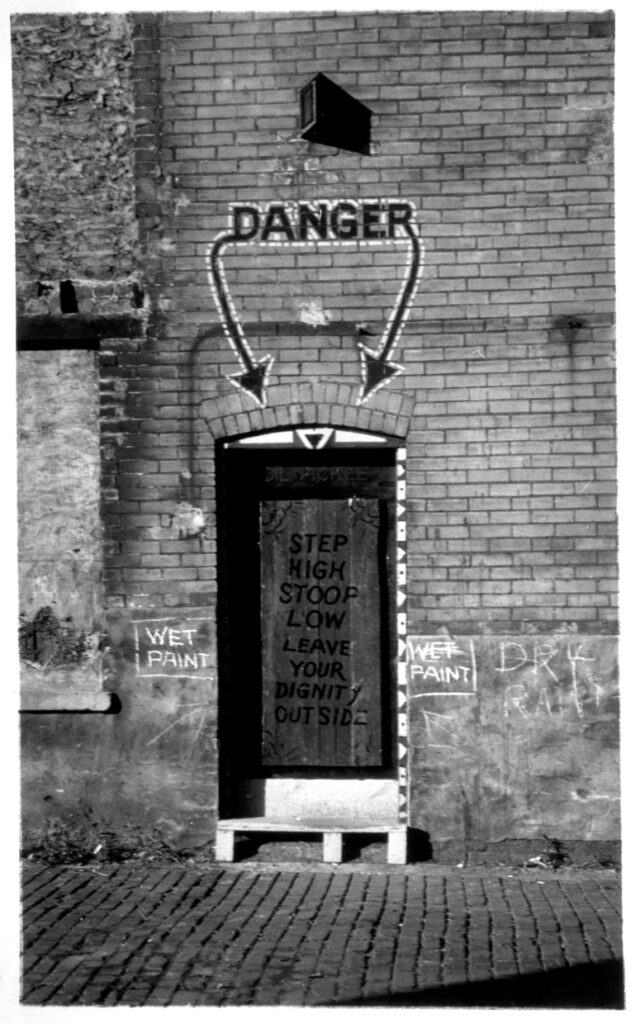

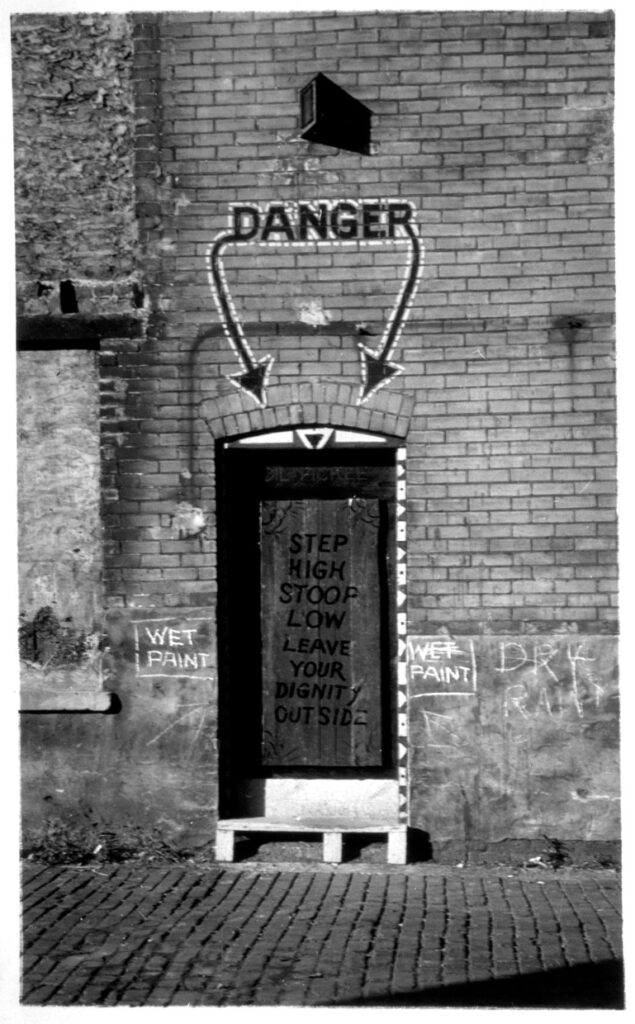

- The Dill Pickle Club changed sites a few times, but settled in this basement on Tooker Place, off Dearborn, not far from the Newberry Library. What does this photograph of the entrance tell you about the club? What does the door’s famous inscription, “STEP HIGH STOOP LOW LEAVE YOUR DIGNITY OUTSIDE,” suggest about the atmosphere that Jack Jones wanted to create?

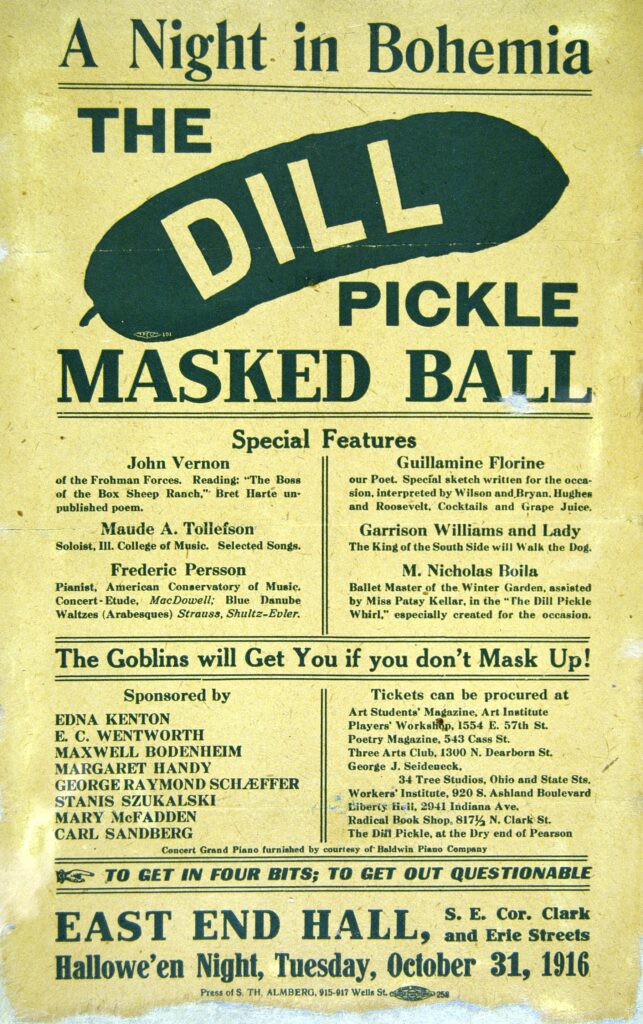

- Examine the flyer for the Dill Pickle’s Masked Ball. Masquerades were among the clubs most frequent and most popular events. What will be the ball’s special features? What do you think the promise of “A Night in Bohemia” might have meant to people who went to the dance? Why do you think costume balls were so popular among Dill Pickle patrons?

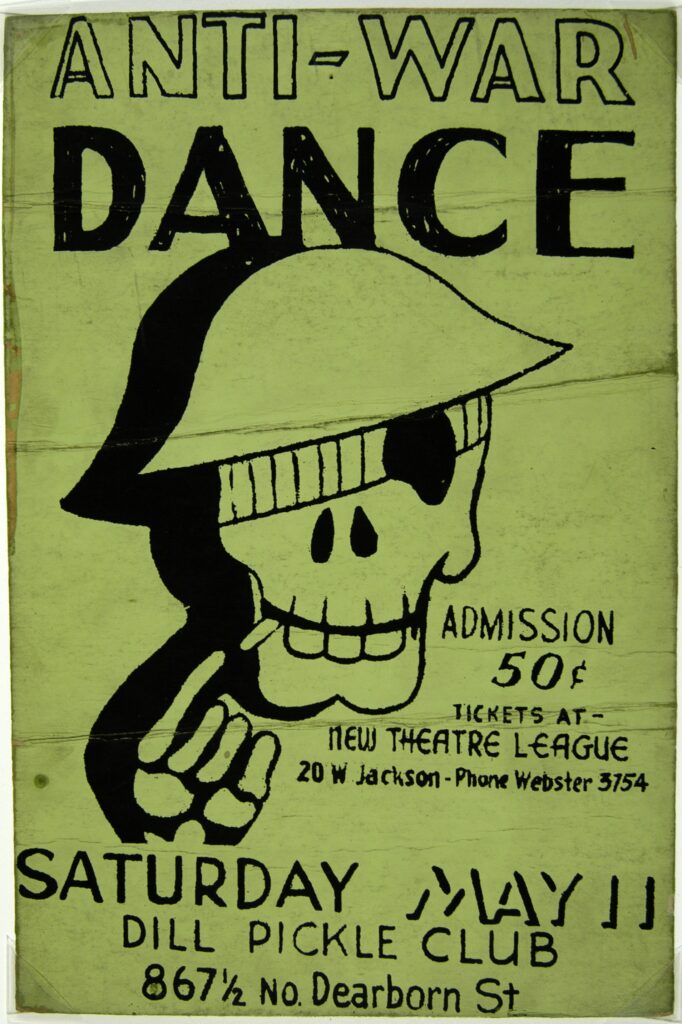

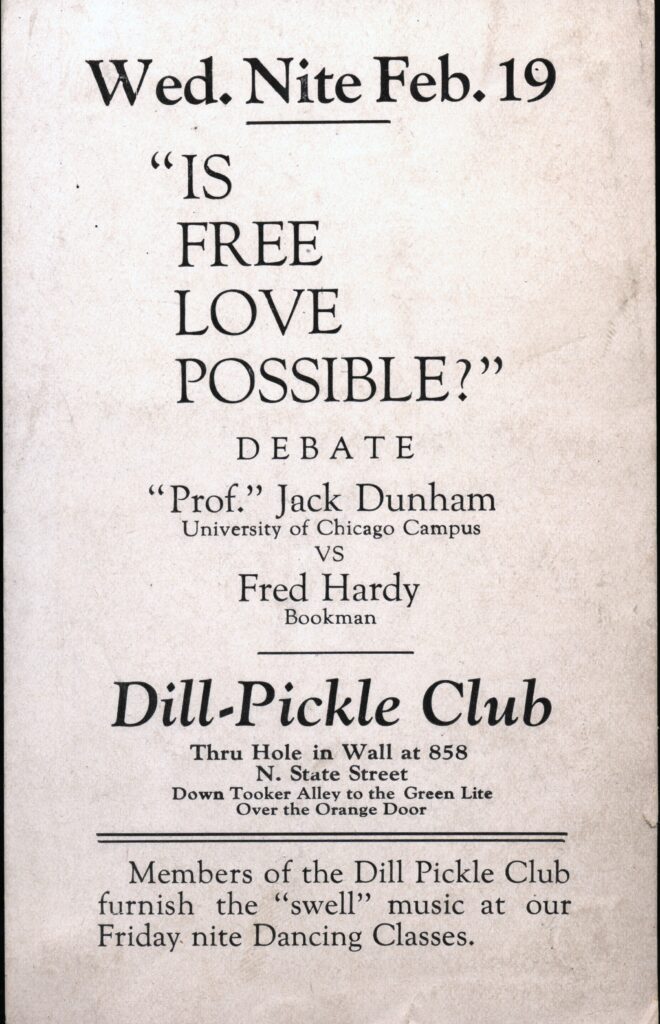

- Examine the flyers for the anti-war dance and the free love debate. What do these flyers suggest about bohemian culture, or the culture of dissent, in Chicago during these decades?

- What are some of the relationships and differences between political and cultural forms of dissent, as suggested by these documents?

Mass Demonstrations and Violence: the Haymarket Affair

During the first week of May 1886, 35,000 Chicago workers walked off of their jobs in massive strikes to protest their lengthy work weeks, with some of these strikes involving violent skirmishes with the police. See below for some of the coverage of these events, as well as political material that was circulating around the time.

Women’s Dissent: Seeking Suffrage and Margaret Sanger’s Birth Control Crusade

See below for material related to the debate around women’s suffrage and Margaret Sanger’s fight to make birth control and sex education legal and accessible to women in the United States.

Bohemian Culture: The Dill Pickle Club

The Dill Pickle Club was a social club on Chicago’s Near North Side that operated between roughly 1914 and 1935. It was established by labor activist Jack Jones and attracted free-thinking, nonconformist artists and intellectuals.

Further Reading

Mary Chapman. “‘Are Women People?’: Alice Duer Miller’s Poetry and Politics.” American Literary History 18:1 (Spring 2006).

James R. Green. Death in the Haymarket: A Story of Chicago, the First Labor Movement, and the Bombing That Divided Gilded Age America. 2006.

Michael Kazin. American Dreamers: How the Left Changed a Nation. 2011.

Jill Lepore. “Birthright: What’s Next for Planned Parenthood?” New Yorker Nov. 14, 2011.

“Margaret Sanger.” MMWR Weekly. Dec. 3, 1999. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm4847bx.htm.

Newberry Library. Outspoken: Chicago’s Free Speech Tradition. 2004. http://publications.newberry.org/outspoken/index.html.

PBS. American Experience: The Pill. www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/pill/index.html.

Janice L. Reiff, Ann Durkin Keating, James R. Grossman, eds. The Encyclopedia of Chicago. 2004. www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org.