Introduction

Many things about everyday life in today’s America would be strange and bewildering to a person transported from the early modern period (approximately 1500-1800) of European history, but paperwork would not be one of them. In fact what we call “paperwork” was familiar to Europeans even before paper (usually from linen rags) became widely available in the fourteenth century, before Johannes Gutenberg invented the movable type printing press in the middle of the fifteenth century, and before literacy became widespread in the late nineteenth century.

The written word was part of social life, defining people’s legal and economic relationships to each other and bringing them together to read and listen.

Early modern people, like us, had to fill out forms on many occasions in their lives. Big moments like getting married, buying land, and collecting an inheritance were often accompanied by legal documents, some of them written in elegant handwriting on the finest paper or parchment. Documents like these not only served as official records of events, but also revealed the prestige of those involved. In a society where most people were illiterate, trained professionals were needed to make paperwork that was legally valid, grammatically correct, and beautifully designed. These professionals included notaries, who drew up different kinds of legal documents for their clients, and master calligraphers, who taught the art of lovely penmanship. The same skills that went into making impressive bureaucratic forms could also produce books and manuscripts for personal enjoyment, spiritual uplift, and education. Like paperwork, these texts did not exist merely to provide information to readers; they were often meant to be shown and read aloud.

The written word was part of social life, defining people’s legal and economic relationships to each other and bringing them together to read and listen. It depended on a network of experts who made their skills available to paying customers. The following collection of images shows a variety of handwritten documents from early modern France and the neighboring parts of Europe, to paint a picture of everyday life for many different kinds of people.

Essential Questions

- When did early modern people need handwritten documents? What purposes did these documents serve?

- Why did writing by hand still matter after the invention of the printing press?

- How do handwritten documents help us understand different aspects of early modern life? What do they reveal about the changes going on in this period?

Writing Masters and Guilds

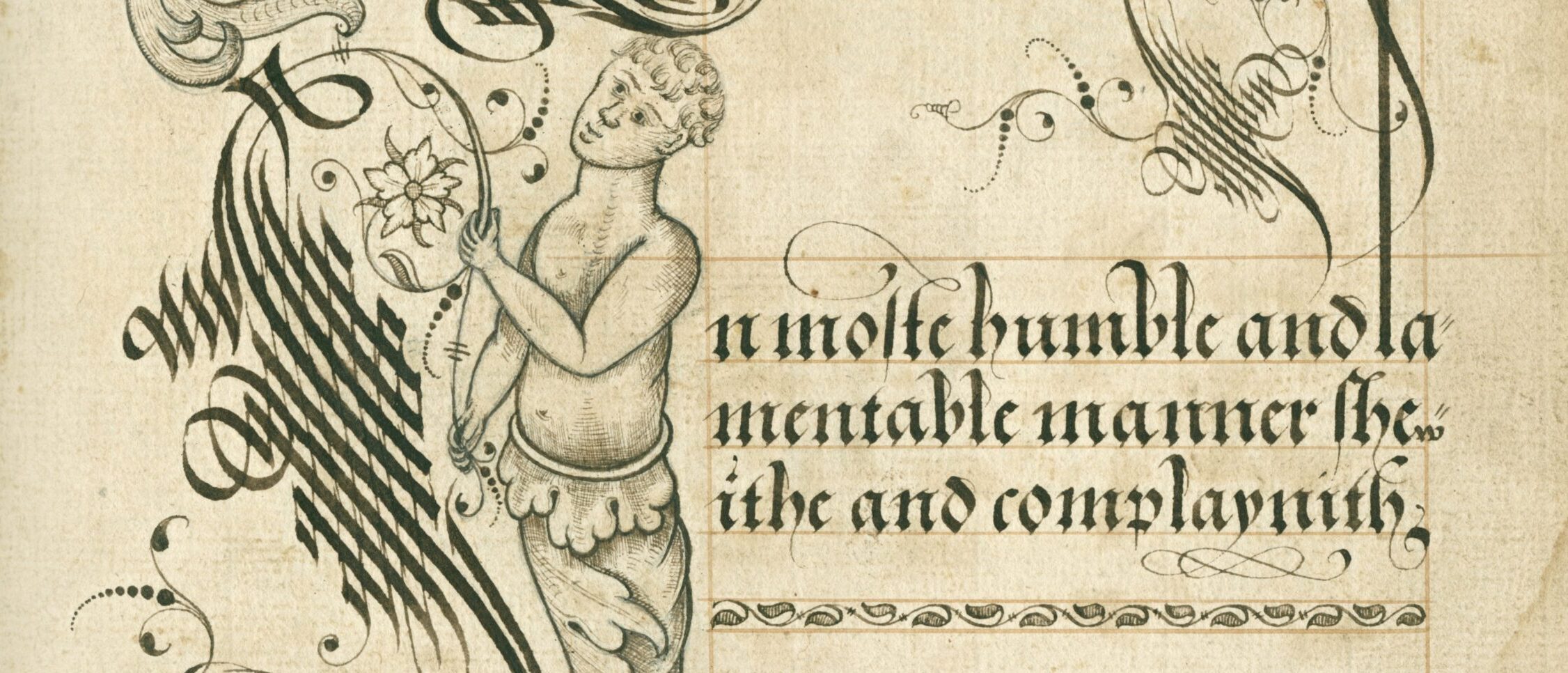

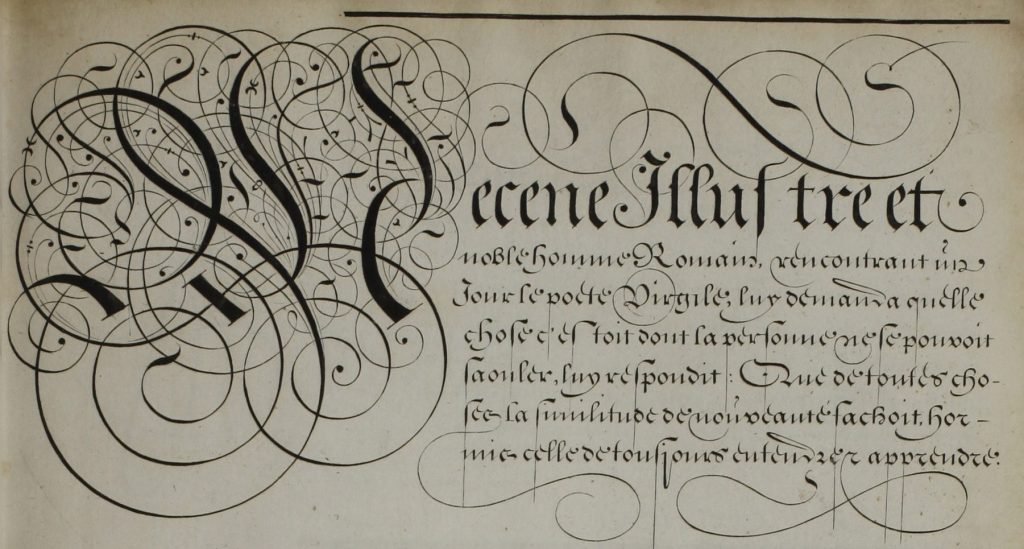

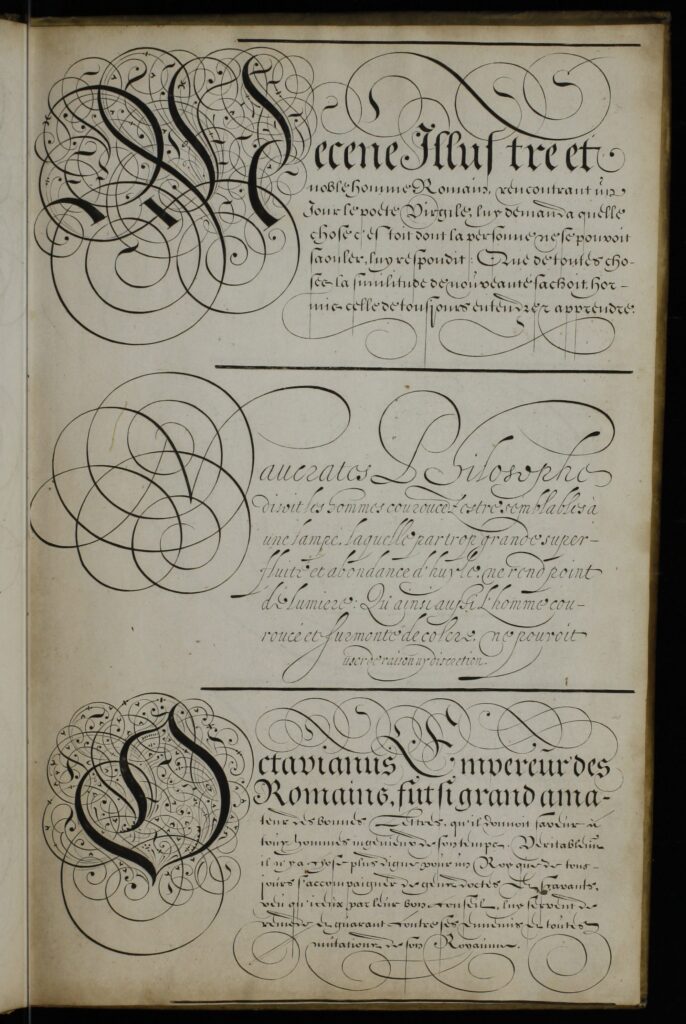

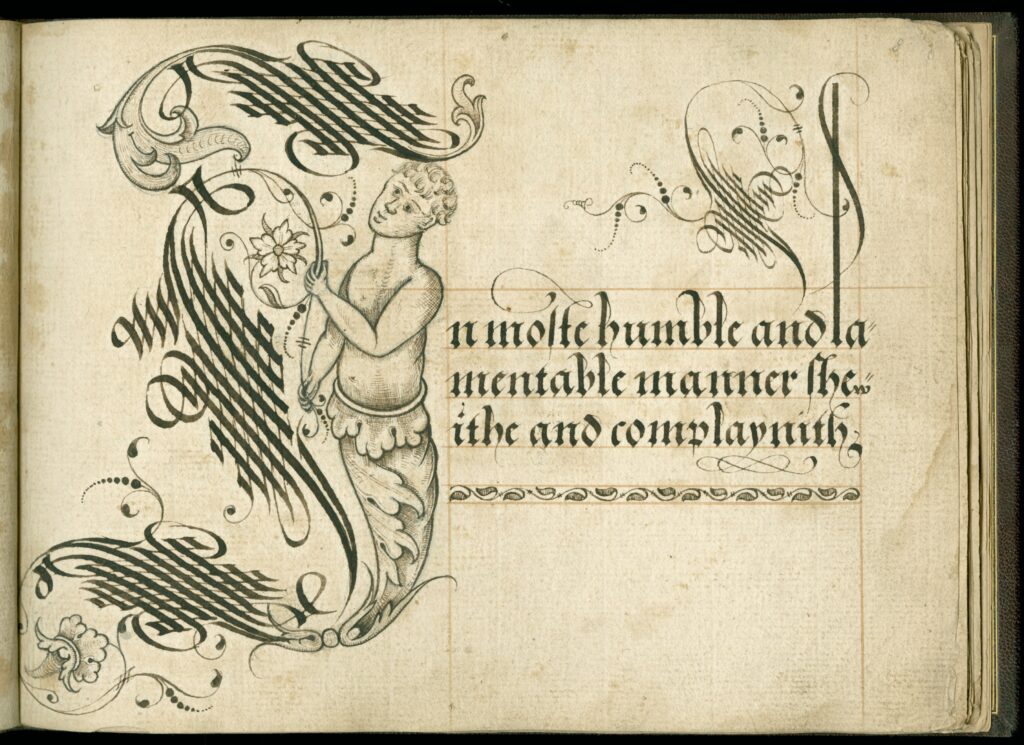

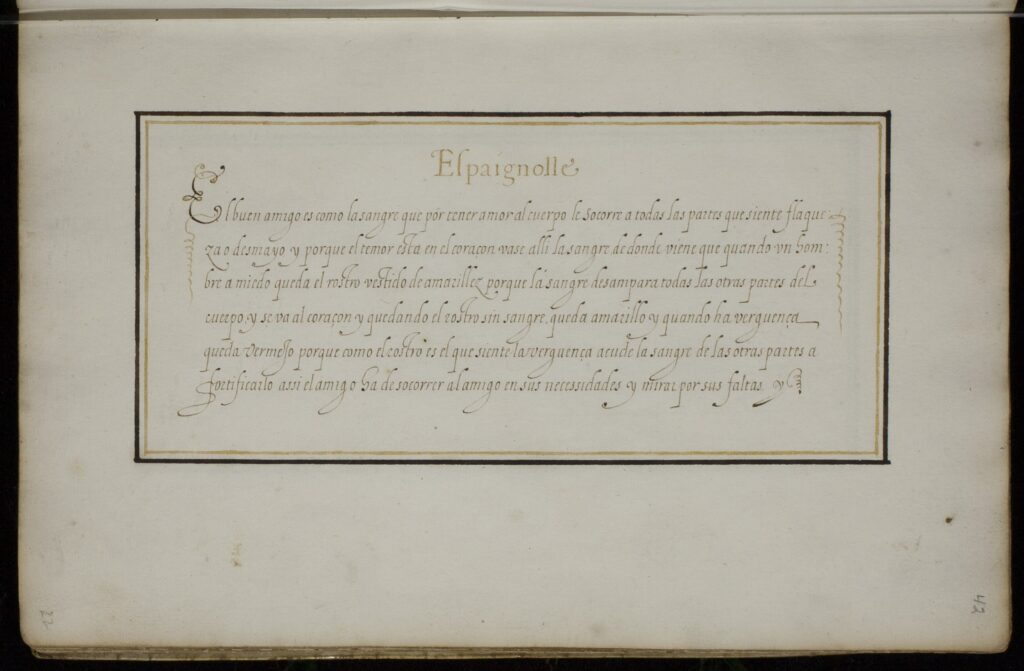

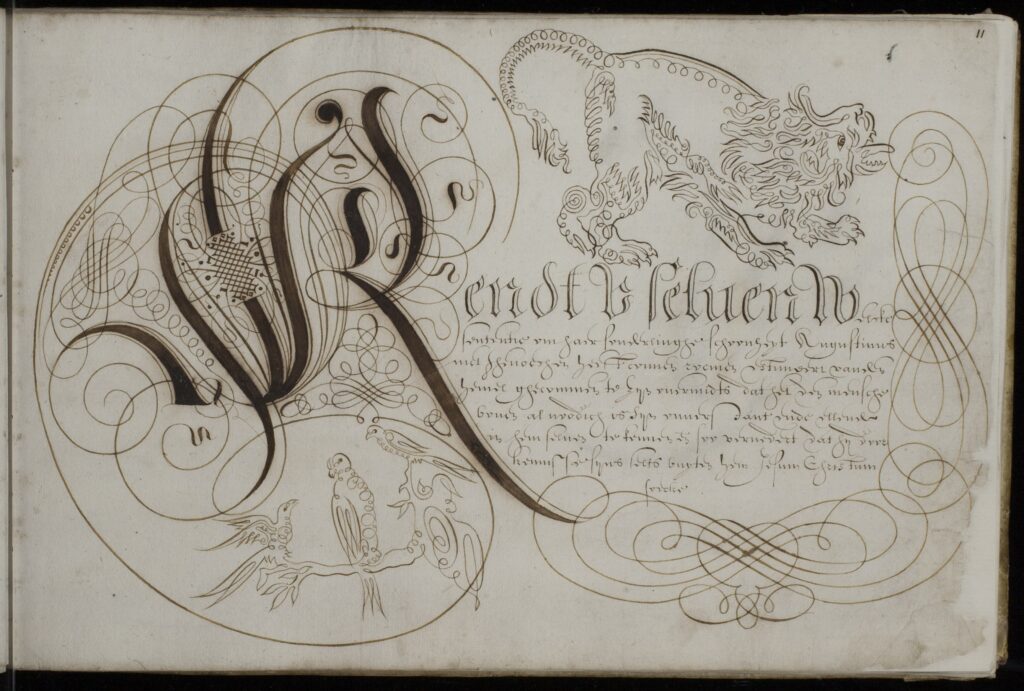

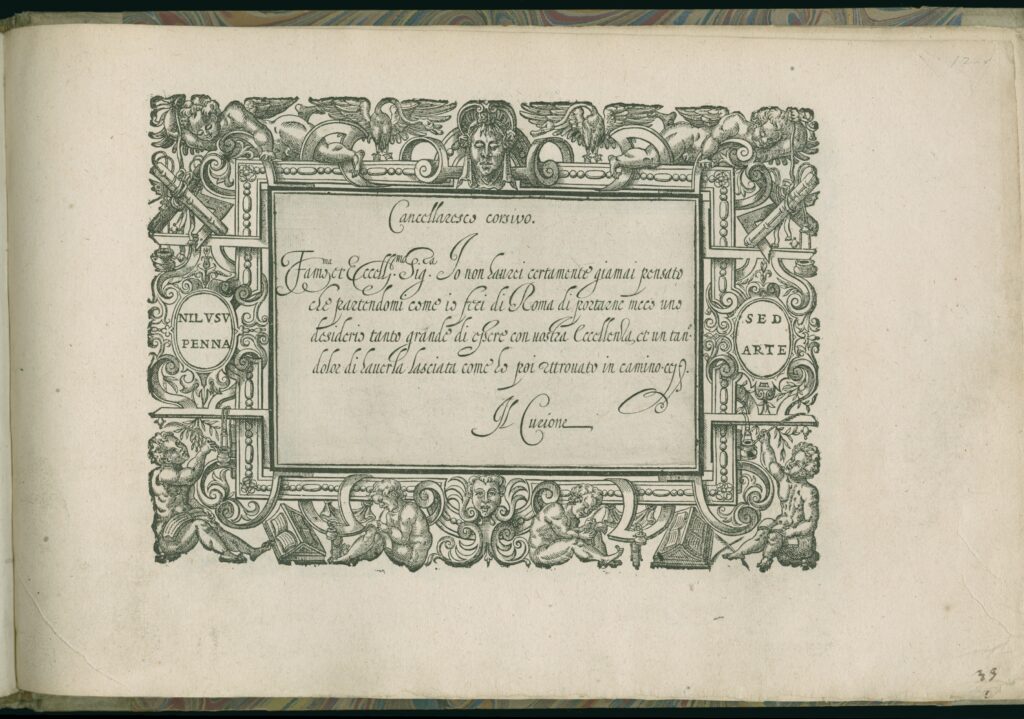

Jan van de Velde (1568-1623) was a French-speaking master calligrapher (maître-écrivain) who lived in Belgium and the Netherlands, where French was the language of elites. Master calligraphers were experts in the art of calligraphy, which literally means “beautiful writing.” Clients would hire them to prepare luxurious documents with ornamental scripts characterized by twirls and spirals known as traits de plume or lineography. Besides giving an ornamental turn to documents, master calligraphers also passed their skills on to others, teaching calligraphy to the children of wealthy families, and publishing books with examples of different styles of handwriting. Writing instructors had existed in France since the thirteenth century. By the fifteenth century, they had begun to use books on calligraphy to teach children how to write in Latin and French. It was not until the beginning of the early modern era, however, that master calligraphers like Jan van de Velde became powerful figures in society, with their own guild and privileges granted by the king of France in 1570.

Transcription of first paragraph from Literary Treasure:

Mecene, illustre et | noble homme Romain, rencontrant un | jour le poete Virgile, luy demanda quelle | chose estoit dont la personne ne se pouvoit | saouler, luy respondit: Que de toutes cho- | ses la similitude de nouveauté fachoit, hor- | mis celle de tousjours entendre et apprendre. |

Translation:

Maecenas, famous and noble Roman man, encountering one day the poet Virgil, asked him about something that no one could have enough of. Virgile replied: all things that appear new [and then are not] are irritating, except learning and understanding.

The story behind the king’s grant to the master writers shows that the skill of fine handwriting remained important even in the late sixteenth century, over a hundred years after the invention of movable type made it possible to print many copies of a document. In 1569, the young French king Charles IX (1550-1574) ruled a kingdom divided by religious tension between Catholics and Protestants. He was also threatened by traitors within his own government. His chancellor—an important minister responsible for keeping all the king’s decrees, treaties, and other documents in order—suspected that one of the king’s secretaries was forging the king’s signature on documents. He assembled a team of the best master calligraphers in Paris to confirm his suspicions; by comparing documents actually signed by the king with the alleged forgeries, they proved that the secretary was guilty. Master calligraphers were the closest thing to forensics experts that the French government could get! This incident seems to have convinced Charles IX that they deserved their own guild, with the exclusive right to instruct children in fine handwriting.

Guilds such as the one Charles IX created out of gratitude to the master calligraphers were a part of everyday life for many early modern people, particularly those who worked, shopped, and lived in towns and cities. Urban residents made up only fifteen percent of the population of France as late as the eighteenth century, and a “large town” of the period (fifty to one hundred thousand people) would not seem very impressive by today’s standards. But towns and those who lived in them had a big impact on early modern society. Towns were centers of trade and industry. The economies of towns, in turn, were heavily influenced by guilds (corps et communautés des métiers), professional bodies that represented the people who worked in a given field, from butchers and bakers to master calligraphers. Peoples’ daily lives were shaped by guilds, whether or not they belonged to one.

Guilds made the rules that determined who was allowed to enter a profession, what kind of goods they were allowed to sell, and how much they were allowed to charge for them. Once the master calligraphers of Paris had their own guild, for example, they could prevent anyone who was not a member from teaching calligraphy within the city limits. But guilds did not exist for every profession or in every city. In Marseille, for example, the second-largest city in France, there was no guild for master calligraphers, who sold their services in an unregulated and competitive market. Nor were guilds all-powerful. Throughout the seventeenth century, the master calligraphers of Paris filed a number of lawsuits with local schoolteachers, who taught writing along with basic literacy and arithmetic. The children taught in these urban schools were members of middle-class families who would need the ability to read, write, and count in order to become merchants or artisans like their parents. Their teachers charged less than wealthy and privileged master writers, who generally served the elites of French society. After several rounds of lawsuits, the courts came to a compromise, allowing ordinary teachers to continue teaching writing as long as they did not use the high-quality books of sample handwriting used by master calligraphers. The judges deciding the case reasoned that writing had become an important part of everyday life for many urban residents, and so the teaching of writing should not be restricted to a rich minority.

Guilds had advantages and disadvantages for urban residents. The early modern state did not give its subjects social security, unemployment benefits, or health insurance. Guilds took on some of these responsibilities, caring for members who were too old or sick to work. In theory, guilds also gave workers a route to upward social mobility, allowing them to become independent, and perhaps even prosperous, shop owners. Apprentices would join guilds at a young age, learning the skills of a particular profession from a master craftsman, and often living in the master’s house with a status somewhere between that of a relative and a servant. After several years of apprenticeship, workers would become journeymen or “companions” (compagnons), still working under a master. Eventually, when journeymen had learned everything there was to know about how to make shoes, clocks, or calligraphy, they would produce a “masterpiece.” This was a high-quality item that was judged by a jury of established masters. If they approved it, the journeyman who made it was allowed to become a master himself.

In practice, guilds shut more doors than they opened. Women were excluded from nearly all guilds in France, as were non-Catholics. Moreover, by the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, guilds increasingly transformed the rank of master into a hereditary occupation passed from father to son, and closed it to anyone who was not already descended from a line of master artisans. These families became rich and powerful, while their workers were denied any opportunity to become masters themselves. The master calligraphers’ guild was a case in point. Within a few decades of being founded, it had become a tool of a few wealthy families from Paris who excluded newcomers.

Question to Consider

- Why did Jan van de Velde choose a story drawn from classical Latin literature as a sample text for his calligraphy book? What does it say about the status of master calligraphers?

Writing Supplies and the “Consumer Revolution”

As the demand for master calligraphers’ services shows, handwritten documents were needed for many sorts of occasions. An early modern printing press could be useful for making many copies of a single text, but it was not practical for making unique documents like personal letters and legal contracts, or for matching the high-end luxury of manuscripts. Printed documents did not replace handwritten ones. In fact, the printed word was often used to advertise the supplies and skills needed for writing by hand. Readers of early modern newspapers could find advertisements for courses in handwriting, guides to composing polite letters, inks of different colors and qualities, etc… As the early modern period went on, writing by hand became more convenient than ever, with the invention in the eighteenth century of a new piece of furniture designed for writing: the desk. It may not seem like a piece of high technology, but the desk was the personal computer of the early modern era, with separate drawers for all the items needed to compose a letter, shelves for books or letters received, and, of course, a large flat space reserved for writing.

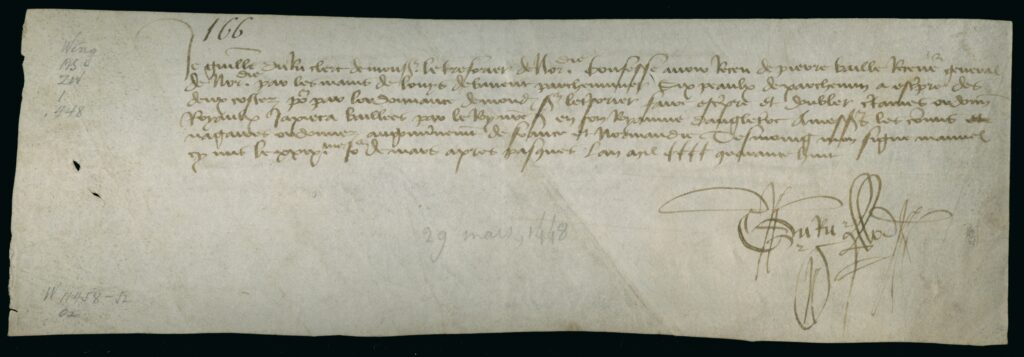

This receipt from 1448 shows that the treasurer of the French province of Normandy had ordered six parchment skins for writing royal decrees. Parchment, made from animal skin, was considered to be more prestigious than paper, and thus more appropriate for the king’s edicts.

Transcription of Duru’s receipt:

Je, Guillaume Du Ru, clerc de monseigneur le tresorier de Normandie, confesse avoir reçeu de Pierre Baille Receveur general | de Normandie par les mains de Louys de Bavent, parcheminier, six peaulx de parchemin à escripre des | deux costés

pourpar l’ordonnance de mondit seigneur le tresorier pour faire escripre et doubler certaines ordonnances | Royaulx ja pieça baillees par le Roy nostre seigneur en son Royaume d’Angleterre à messeigneurs les commiset| nagaires ordonnez au gouvernement de France et Normandie. Tesmoing moy signe manuel |cy mis le xxix.me jour de mars apres Pasques l’an mil cccc quarante huict. ||Translation:

I, Guillaume Du Ru, clerk of monseigneurthe treasurer of Normandy, acknowledges having received from Pierre Baille, Receiver General of Normandy, by the hands of Louis de Bavent, parchment maker, six skins of parchment to write on both sides by the request of my lord the treasurer to write and copy some royal ordinances given by our lord the King in his Kingdom of England to his councilors and regarding the government of France and Normandy. Signed the 29th day of March after Easter the year 1448.

Writing supplies were also more complicated than they looked. Making ink, for example, required global networks of trade, particularly with Africa, where the sap of certain trees was turned into gum arabic, a viscous substance used to thicken ink. Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Britain and France repeatedly fought over access to the gum arabic markets of Senegal, which had a particularly abundant supply. While nations today go to war for oil, early modern countries went to war for ink! The finest paper and wax (used to seal envelopes) were also imported from foreign countries such as the Netherlands and Spain.

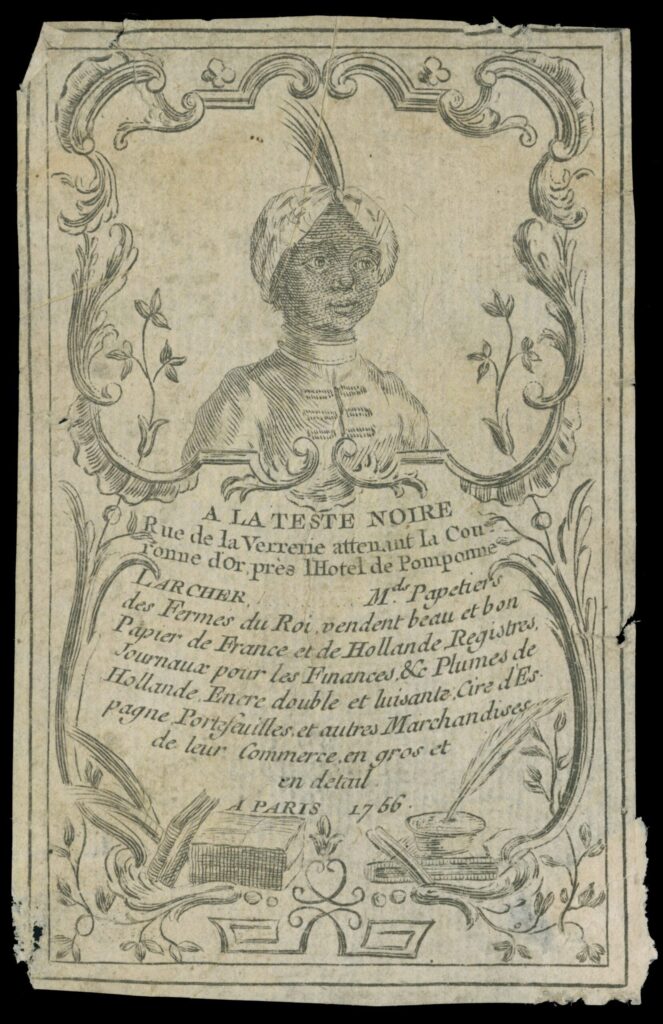

Transcription of the Larcher Advertisement:

A La Teste Noire | Rue de la Verrerie attenant la Cou-| ronne d’Or pres l’Hotel de Pomponne |

Larcher marchands papetiers | des Fermes du Roy, vendent beau et bon | Papier de France et de Hollande, Registres, | Journaux pour les Finances, etc., Plumes de | Hollande, Encre double et luisante, Cire d’Es- | pagne, Portefeuilles, et autres Marchandises | de leur Commerce, en gros | et en detail. | A Paris 1756. |Translation:

At the Black Head.|Rue de la Verrerie adjacent to the Golden | Crown near the Hotel de Pomponne |

Larcher, merchants stationers| to the King’s Farms, sells beautiful and good | French and Dutch paper, registers, | ledgers, etc., Dutch | quills, concentrated lustrous ink, Spanish | wax, wallets and other goods | of their line of business, wholesale | and retail.| In Paris, 1756.|

Pens, ink, desks, and other items associated with writing by hand were part of the “consumer revolution” that scholars have identified in the early modern era. This was the period when ordinary, non-elite people in towns and eventually even villages began to consume an increasing amount and variety of goods. Even as the gap between masters and journeymen grew, standards of living rose in much of eighteenth-century Europe, allowing more and more non-elite people to buy items that were not strictly necessary for survival. Just as importantly, peoples’ attitudes to, and experiences of, consumption also changed. For the first time in European history, many people encountered advertisements for products in their daily lives. These ads not only sold products, but also contained information about the outside world, and images of exotic goods or recent inventions. Advertisements also tried to convince people that they ought to adopt certain habits or learn new skills, including writing beautiful letters.

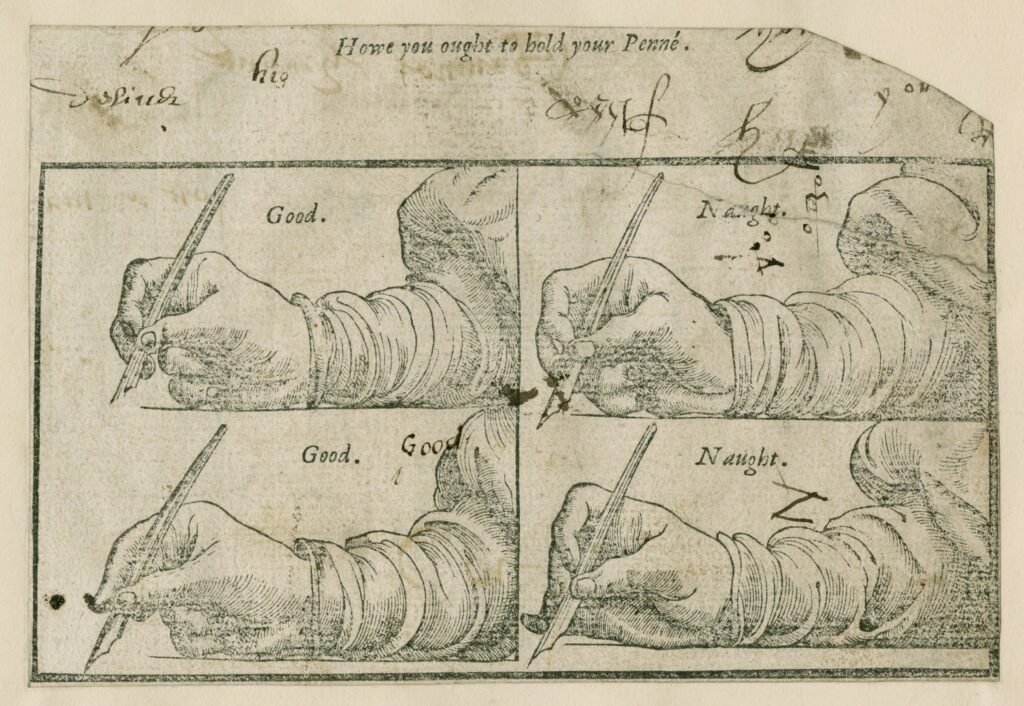

Jehan de Beauchesne’s 1571 guide to writing by hand (above) was designed for an international readership. People throughout early modern Europe were interested in learning to write, starting with the fundamentals of holding a pen correctly.

Questions to Consider

- What does the image of Larcher’s advertisement have to do with writing? Why would he have chosen this “exotic” image of a man in a turban?

- What does Jehan de Beauchesne’s illustration tell us about what he expected the average reader would know already about writing by hand?

Contracts and Rural Life

Paperwork was as much a part of life in the early modern countryside as it was of life in the cities. As the examples below show, handwritten contracts defined the economic basis of rural life. Having access to resources like land, money, and technology required written documents, and so also required professional notaries who could make legally valid contracts. Such contracts from the period also reveal how the society and economy of rural France was being changed by new influences.

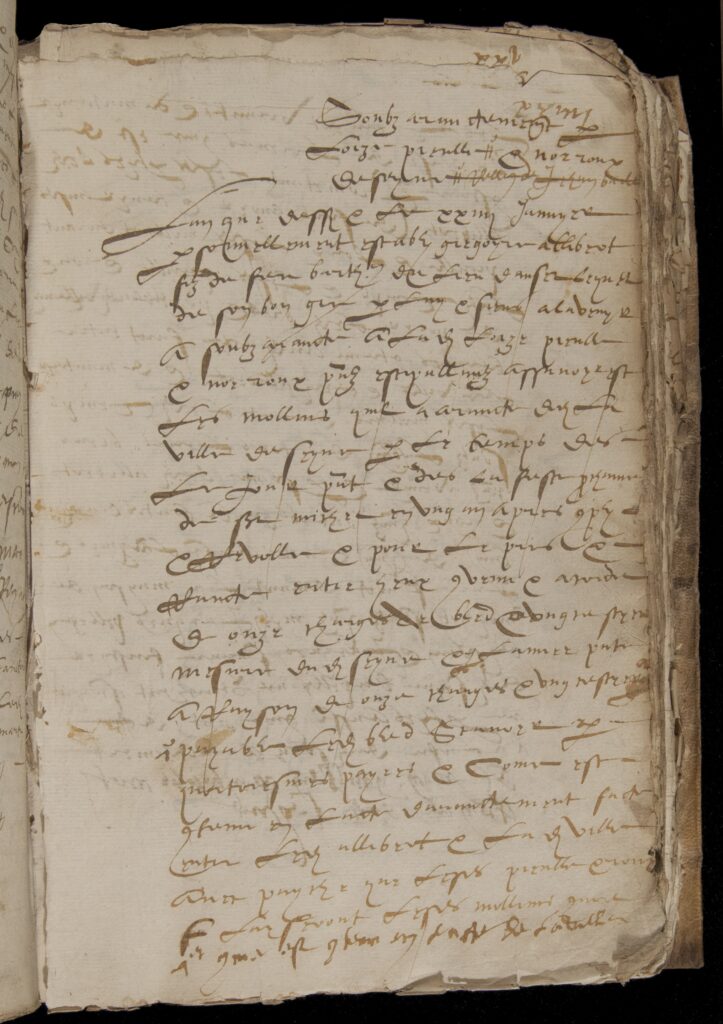

Flour mills were managed by land owners, and could be used by anyone in the community for a certain fee. They were an important part of urban and rural communities alike, and an important element of local commerce. Farmers would harvest wheat and bring it to flour mills, and the flour would then be used to make bread, the staple of French cuisine, then as it is today. In some cases, as in the document above, cities would own flour mills, and rent them to members of the community. This contract, recorded by Guilhem Peytralis, allows a man to sublet a flour mill to a couple to make flour with the wheat they harvested.

Transcription of Peytrails’ contract (starting line 4):

L’an que dessus & le XXIIII janvyer, | personnellement estably Gregoyre Allibert, | filz du feu Barthelemy du lieu d’Auset, lequel | de son bon gré, par luy & siens à l’avenyr, | a soubz arancté à ladite Loïze Pieulle | & Noé Roux, presentz estipullantz, assavoyr est | les mollins qu’il a arancté dedans la |ville de Seyne par le temps des | le jour present & des la feste prochaine | de Sainct Michel en ung an aprés comply | & revollu, & pour le pris & | rancte entre heux convenu & acordé |de onze charges de bled & ung cestyer | mesure dud. Seyne, […]

Translation (starting line 4):

In the same year, on January 24, personally established Gregoyre Allibert, son of deceased Barthelemy of Auset, who, of his free will, by himself and for his future heirs, is subleasing to Louise Pieulle and Noé Roux, here present, the flour mills that he is renting in the town of Seynes, from this day forward, and in a year at the Feast of Saint Michael for the price and rent negotiated between them of eleven charges of wheat and one setier, measure of the city of Seynes, […]

The early modern period, like the Middle Ages, was a time when nobles dominated much of French society, particularly in the countryside, where they owned vast amounts of land. But there were major differences in the roles of the nobility in the two periods. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, at the height of the “feudal system” (a term that was not actually used by people in the medieval period), nobles’ power in the countryside was centered on estates given to them by the king in exchange for military service. France had no permanent army, so when the king went to war he would summon his nobles, who came ready with their own weapons, horses, and soldiers. Wealthy lords might have dozens, even hundreds of armed men at their command. As payment for maintaining these private armies, lords enjoyed many special rights over their estates and the people who lived on them.

These people could be serfs, required to live on the lord’s estate and forbidden to leave, or free peasants who rented land from the lord as tenants. Either way, they were required to pay a number of different taxes to the lord, including banalités, or fees, to use the local mill, oven, wine press, etc., which were usually the lord’s property. The banalités that peasants and serfs paid were so much a part of daily life that “banal” has come to mean “everyday” or “unextraordinary” in both French and English! Those who failed to pay these fees could be taken to the local court, where the lord himself was the judge. Combining military, economic, and judicial power, lords had many advantages over their subjects.

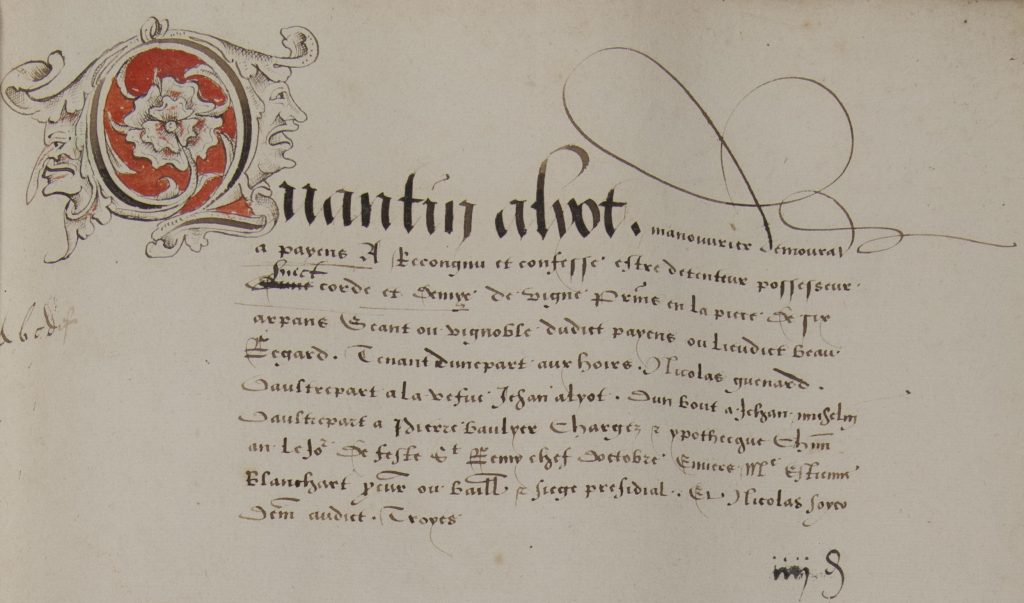

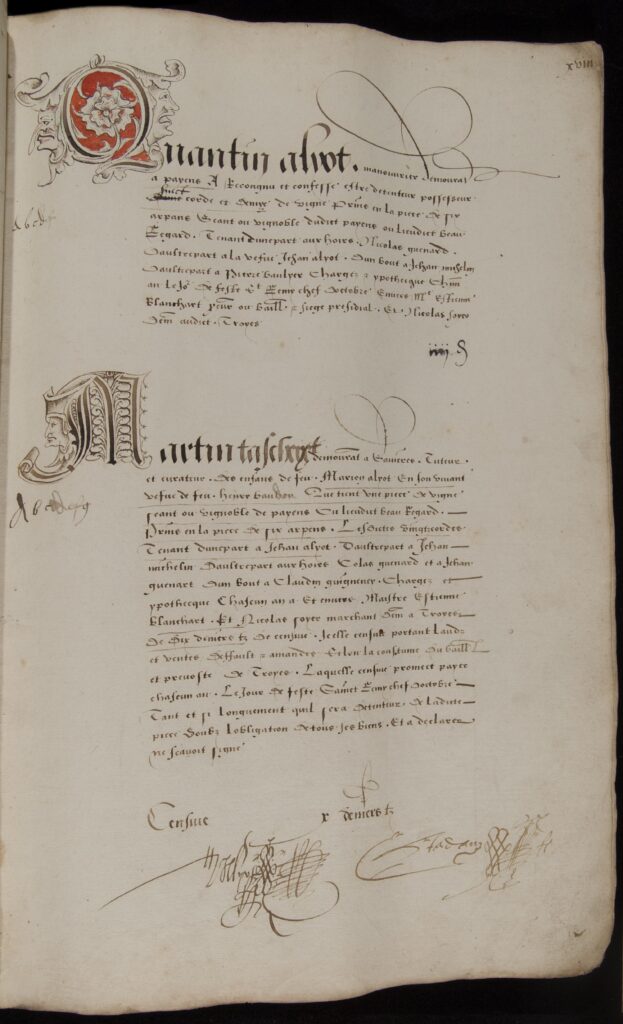

The document above is a censier or rent-roll of tenant farms in the parish of Payens, near the city of Troyes, drawn up when Nicolas Soyer and Etienne Blanchart inherited farm lands in November 1570. When Catherine Guillaume, Soyer’s mother, passed, she bequested the land to her son and her niece Gillette Guillaume, wife to Etienne Blanchart. The document was made to confirm and acknowledge the rights and obligations of owners and tenants. Alyot, here, has free use of a part of a vineyard that he is free to cultivate, for which he owes yearly charges to Blanchart and Soyer.

This censier is particularly beautiful, with its illuminated grotesque initials and high end script. It was signed by every single tenant of Soyer and Blanchart, as well as the notary who made the document. It is clear that this was an item of a certain price, that conveyed the idea that the new owners took the business of administering these farm lands seriously. This item would have certainly made an impression on the tenants who signed it.

Transcription of Payens Rent Roll:

Quantin Alyot, manoeuvrier demourant | à Payens, a recongnu et confesse estre detenteur possesseur | huict corde et demye de vigne prins en la piece de six | arpans seant ou vignoble dudit Payen ou lieu dict Beau | Regard, tenant d’une part aux hoirs Nicolas Guenard, | d’autre part à la vefve Jehan Alyot, d’un bout à Jehan Michelin, | d’autre part à Pierre Baulyre, chargez et ypothecqué chacun | an le jour de feste Sainct Remy chef d’octobre envers maistre Estienne | Blanchart, procureur ou bailliage et siege presidial, et Nicolas Soyer | demourant audict Troyes.

iiii. solz

Translation:

Quantin Alyot, manœuvrer, residing in Payens, recognizes and acknowledges being possessor of eight and a half cords of vines in a six arpents vineyard in Payens in the site called Beau Regard, adjacent to the pieces of the heirs of Nicolas Guenard, of the widom of Jehan Alyot, of Jehan Michelin and Pierre Baulyre, charged and mortgage due every year on the first of October, day of the Feast of St. Remy, to Estienne Blanchart, procureur ou bailliage et siege presidial, and Nicolas Soyer, residing in Troyes.

iiii. solz.

By the early modern period, nobles still enjoyed many privileges, but they now faced increasing competition from the royal government and from non-nobles. The monarchy created a permanent army toward the end of the Hundred Year’s War (1337-1453) against England, and by the early seventeenth century it began to suppress the private armies of the nobility. Their distinctive military role, and the traditional justification of their privileges, was slipping away from nobles. Over the same span of time, the French kings established new courts that reduced nobles’ power to judge those who lived on their lands. In the Middle Ages, ownership of an estate had made lords into nearly independent rulers of personal territories, with their own courts and soldiers. In the early modern era, this was no longer true. Estates were now primarily economic units rather than military or political ones.

While peasants and serfs of an earlier era had few options for protesting against oppressive lords short of violent rebellion, early modern people could take their lords to court, bringing lawsuits against them before new judges appointed by the king. Wealthy peasants who owned their own land were especially likely to sue local nobles. They resented the taxes and fees such as banalités. Often they lodged their suits by working through the “communities of residents” (communautés d’habitants), councils formed by the non-noble landowners of a particular village in order to represent their collective interests. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries particularly, wealthy peasants were sometimes able to take, reduce, or eliminate the privileges of lords, putting an end to local banalités, for example. Mills, wine presses, and other important economic resources passed out of the hands of nobles into those of village communities or individual non-nobles. The contract below from the last sixteenth century shows a mill owned by a non-noble being rented out to two other non-nobles.

The majority of rural people, however, were not wealthy enough to benefit greatly from these changes. Just as in the medieval period, most inhabitants of the countryside did not own their own property. Instead they rented land as tenant farmers, paying an annual rent or cens to the owner, who could be a noble, wealthy non-noble, or even a religious institution.

Questions to Consider

- Examine the contracts for the flour mill and vineyard. On what days are the annual payments due? What does this tell us about the importance of religion in early modern life?

- Compare the two contracts. What elements does the second document include to establish its importance?

Family Papers: Marriage and Inheritance

Marriage and inheritance were two of the most important elements that organized everyday life for early modern people of all social classes. While marriage created a new family unit, as the bride (usually in her mid-to-late twenties) and groom (slightly older) left their parents’ homes to set up a household of their own, inheritance moved wealth between generations of the same family. Marriage and inheritance were also legal matters that required the involvement of literate professionals like priests, notaries, and lawyers—and both could turn into legal battles when spouses or heirs disagreed. Written documents were necessary to make marriages and inheritances officially valid, and could turn into critical pieces of evidence during lawsuits.

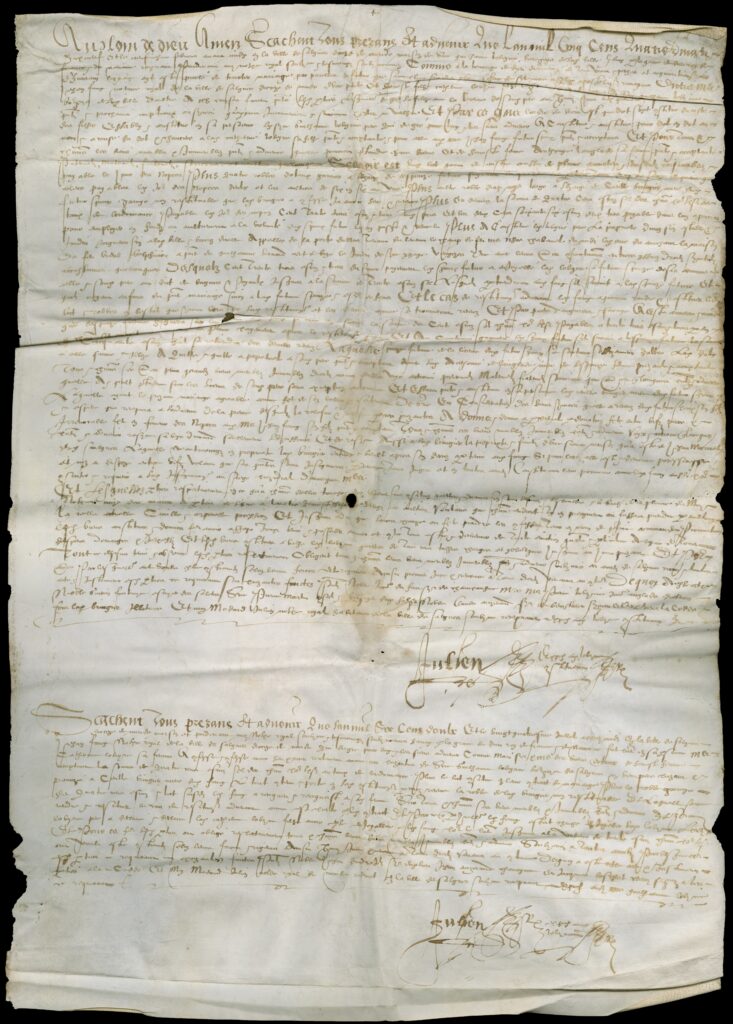

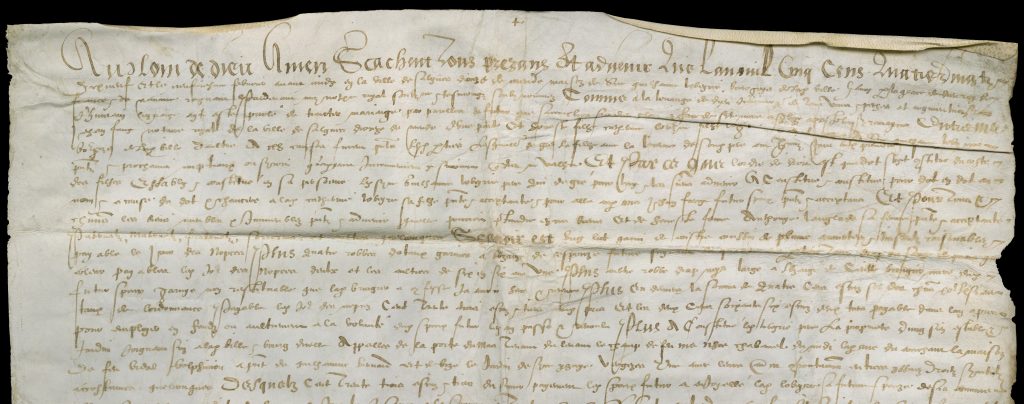

Selection: Marriage Contract of Jean Favy and Catherine Lobeyrie (1599)

Before a wedding would actually take place, the parents of the bride and groom would meet, often along with other family members, to discuss the dowry and other financial matters. They would then have a marriage contract like this one from 1599 drawn up by a notary.

Transcription of the Marriage Contract (first five lines):

Au nom de Dieu, amen. Sçachent tous prezans et advenir que l’an mil cinq cens quatre vingtz | dix neuf et le neufviesme febvrier avant midy en la ville de Salgues, dioceze de Mende, maison de sire Guilhaume Lobeyrie, bourgoys de lad. ville, Hanry par la grace de Dieu roy de | France et de Navarre regnant, par devant moy notaire royal soubzsigné et tesmoings soubznommez, COMME à la louange de Dieu, delivrance de tous vices et pechés et augmentation | d’humain lignaige ayt esté parlé de traicter mariaige par parolles de futur, que s’acomplira si à Dieu plait en face de saincte mere Esglize apostolicque romayne, ENTRE maistre | Jehan Favy notaire royal de la ville de Salgues, dioceze de Mende, d’une part, et honneste filhe Catherine Lobeyrie […]

Translation:

In the name of God, amen. Let it be known to everyone, in the present and in the future, that in the year 1599 on February 9, before noon, in the town of Saugues, diocese of Mende, in the house of Guillaume Lobeyrie, living in this city, in the reign of Henry, by the grace of God King of France and of Navarre, before me, royal notary, who, along with the witnesses named below, signed below, for the praise of God, deliverance from vices and for the continuation of human lineage, has been discussed a marriage contract, that will take place, God willing for his saint catholic church, between Jean Favy, notary royal in Saugues, diocese of Mende, on one hand, and honest lady, Catherine Lobeyrie […]

Laws governing marriage and inheritance reflected the diversity of early modern France. They varied greatly from one part of the country to another. While southern France was influenced by the ancient traditions of Roman law, the north of France was a patchwork of different “customs,” local practices that had developed over the course of the Middle Ages. In some regions, the oldest brother would inherit the largest share of the family property, while in others the inheritance was divided more equally among the brothers, and sometimes among the sisters as well.

But throughout the country, the early modern French state was making it impossible to get married or to inherit without an increasing amount of paperwork. In the medieval era, for example, it was still legally acceptable for young couples to be married “clandestinely,” without their parents’ permission (think of Romeo and Juliet). In 1556, however, the Parlement of Paris (a supreme court responsible for much of northern and central France) ruled that the government would no longer recognize these marriages. In the following decades, French kings made several decrees reinforcing this decision, and ordering priests not to marry couples who did not have their parents’ permission. These decrees show that the state was increasingly present in the everyday lives of French people, even in relationships between parents and their adult (or soon to be adult) children. Where the state went, paperwork followed. In 1639 the monarchy ordered that marriages could not take place unless the couple gave the priest written proof that their parents approved.

The new marriage laws were tied to changes in inheritance that gave parents more power over their children. In 1556, parents not only gained more power to control who, and if, their children married, but also gained the right to disinherit “rebellious” children. On the other hand, couples who married clandestinely would find themselves not only unable to inherit from their parents, but also unable to pass their possessions on to their own children! The monarchy thus offered parents a great deal of power over their children, but in exchange parents would have to respect its idea of a proper marriage, and, of course, fill out the proper forms.

Marriage contracts were not just bureaucratic forms that satisfied the demands of the French monarchy, however. These documents, officially proving that the future bride and groom intended to marry each other, could be used by different people for a variety of purposes. These included forcing a reluctant fiancé or fiancée to marry his/her partner. A person who had signed a marriage contract and then showed reluctance to actually marry the betrothed could find him- or herself brought to court. In fact, even when both members of the couple wanted to break the contract, they could find themselves forced by the local government to marry anyway! Whether this made for happy marriages is another question.

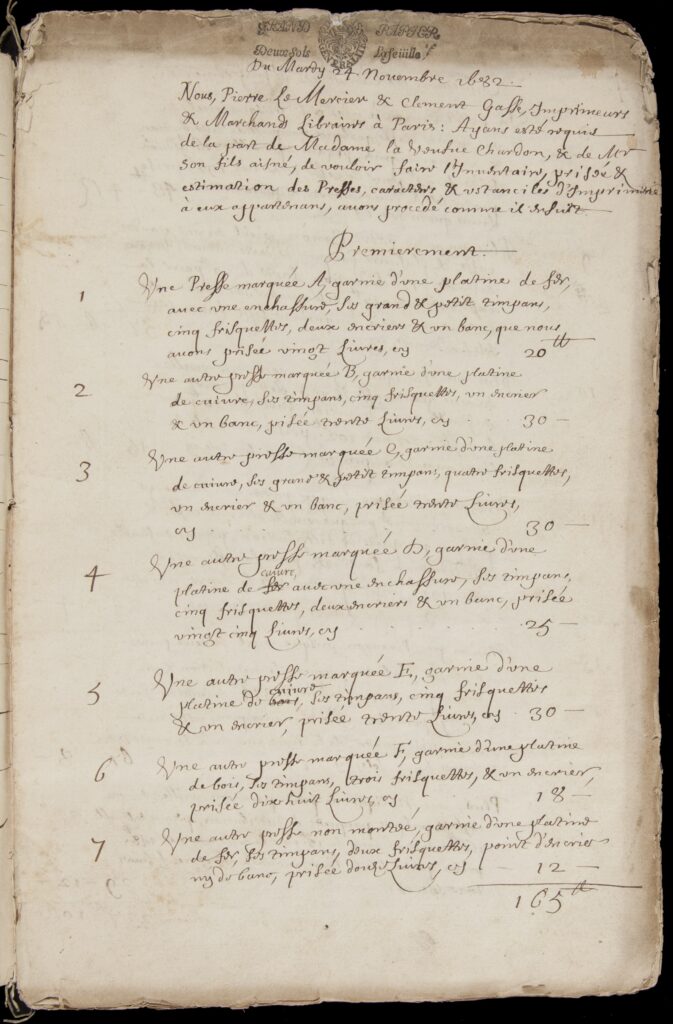

Selection: Possessions of the Printer and Bookseller Jean Chardon (1682)

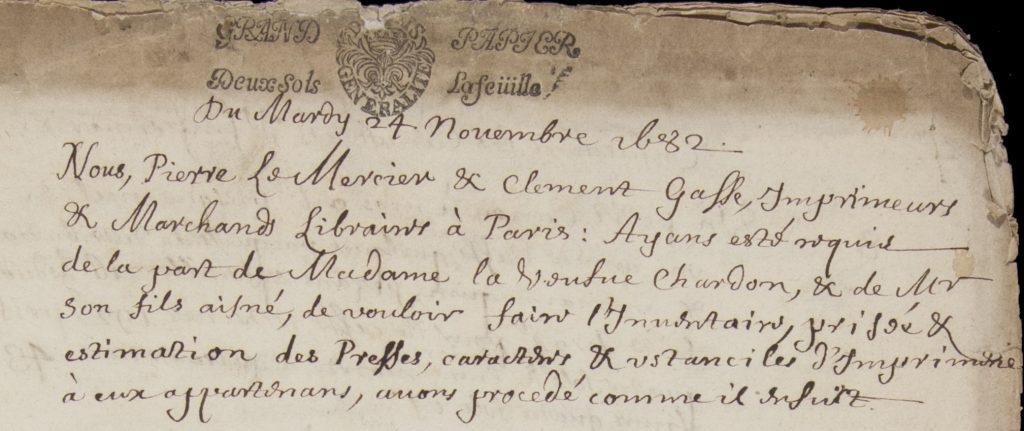

This handwritten inventory of the possessions of the printer and bookseller Jean Chardon was drawn up by two Parisian printers.

Transcription of Inventory (first seven lines):

Du mardy 24 novembre 1682

Nous, Pierre le Mercier et Clement Gasse, imprimeurs | & marchands libraires à Paris: ayans esté requis | de la part de madame la veufve Chardon, & de monsieur | son fils aisné, de vouloir faire l’inventaire, prisée & | estimation des presses, caracteres et ustanciles d’imprimerie | à eux appartenans, avons procedé comme il ensuit.

Translation:

On Tuesday, November 24, 1682

We, Pierre le Mercier and Clement Gasse, printers and booksellers in Paris, having been asked by the widow and the eldest son of Jean Chardon to draw up the inventory & appraisal of their printing presses, types and printing material, we proceeded as follows.

Contracts also defined the status of the dowry, the property that the bride brought into the marriage. Once married, she would not be able to acquire more property in her own name, and anything she earned would be part of the family wealth that was legally under the control of her husband. The dowry, however, would remain under her control and would remain in her hands if she became a widow (while, depending on the regional customs, the rest of the inheritance might be divided among their children). Having a secure dowry, therefore, was essential for brides hoping to keep a degree of independence during and after their husbands’ lifetime. A dowry and a marriage contract also offered wives a way out of marriages where they were unhappy or unsafe. Legally speaking, there was no divorce in early modern France. But husbands and wives who were unable to get along could request a separation, and in some cases their property could be divided up as well, returning the dowry to the control of the wife.

Early modern France was a patriarchal society where fathers had legal authority over their children, and husbands over their wives. But women were not helpless victims. They could, and did, turn to the courts in search of protection against husbands who squandered the family’s wealth or who physically abused them. Early modern judges, however, did not see violence in itself as sufficient reason for separation. Wives seeking separation had to show that their husbands had hurt them or threatened them beyond what people in the community believed were the acceptable limits of domestic violence against women. Within these limits, husbands were able to commit what would today be considered acts of abuse. The increasing legal and bureaucratic regulation of marriage in early modern France gave women a certain amount of power, but only within a larger structure designed to increase the authority of male heads of households.

Questions to Consider

- What does the first paragraph of the marriage contract tell us is the purpose of marriage? Why do you think the document begins in this way? How does this compare to the actual role of marriage contracts in French society?

- How do the opening lines of the deceased printer’s inventory compare and contrast with the marriage contract? What do the similarities and differences suggest about the way these contracts were understood by the parties involved?

Book of Hours: Writing and Spiritual Life

From the late Middle Ages well into the early modern period, no other kind of book was as popular as the book of hours, which listed different prayers along with illustrations. Books of hours allowed individuals to follow the Divine Office, a sequence of prayers said in Latin by monks and nuns at eight times or hours during the day. Without leaving their homes, readers could imitate the holy men and women who had withdrawn from the world. Faithful readers who used books of hours as intended were imposing discipline and order on their spiritual lives by saying the same prayers at the same time as other believers. But these books also offered readers the chance to express their personal views and desires, including ones that were not particularly holy.

Wealthy people could commission books of hours that were written by hand on the finest parchment, using them to showcase both their wealth and their spirituality. The book of hours seen in this collection, for example, with its fine parchment and beautiful illustration, was made for such a client. Printed books of hours, which became available in the late fifteenth century, were more in the budget of ordinary people, but even those who could not afford a custom-made manuscript found ways to personalize their books. Readers might write the prayers they had heard or thought of themselves on the blank spaces of the book, or decorate the book with souvenirs from pilgrimages to saints’ shrines. These prayers—for healing, for children, for the soul of a deceased person—shed light on the private sorrows and joys of early modern life. Books of hours of all kinds had a particular connection to women. Brides often received books of hours illustrated with images of Mary and female saints, and women within a single family would pass down treasured books of hours from one generation to another. While the prayers that made up the hours were in Latin, books of hours also included prayers in French (or other languages, depending on the region), particularly ones to Mary. One of the most popular was the “Joys of the Virgin,” which celebrated happy moments in Mary’s life. Mothers would often use these texts to teach young children how to read. In this way, books of hours not only offered an ideal image of the joys of motherhood experienced by Mary, the mother of God, but also served as a practical tool for earthly mothers.

Questions to Consider

- Examine the illustration in the book of hours below. Is its purpose spiritual, decorative, or both? What does this tell us about the ways books of hours could be used?

- How is Mary represented in the prayer to her? What is her role? How does the document imagine her relationship with Jesus? With the person praying?

The Business of Writing

Throughout early modern France, the business of writing was a large part of daily life. See below for a range of archival examples which demonstrate the variety of functions and importance to social life of what we now think of as “paperwork.”

Contracts and books

Below you can see legal contracts, including a rent roll for tenant farmers and a marriage contract, as well as an example of the Book of Hours, Christian prayer books which played an important role in the social life of early modern France.

Further Reading

Blaufarb, Rafe. “Conflict and Compromise: Communauté and Seigneurie in Early Modern Provence,” Journal of Modern History, vol. 82, n. 3 (September, 2010), p. 519-545.

Desan, Susan & Jeffrey Merrick, ed. Family, Gender & Law in Early Modern France. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2009.

Hanley, Sarah. “Engendering the State: Family Formation and State Building in Early Modern France,” French Historical Studies, vol. 16, n. 1 (Spring, 1989), p. 4-27.

Hardwick, Julie. Family Business: Litigation and the Political Economies of Everyday Life in Early Modern France. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Reinburg, Virginia. French Books of Hours: Making an Archive of Prayer, c. 1400-1600. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.