Introduction

Between 1500 and 1800, three empires—Ottoman, Habsburg, and Venetian—competed for the lands and seas of southeast Europe. The arrival of Suleyman the Magnificent to the gates of Vienna in 1529 signaled the consolidation of a new Ottoman world power. The second (and also failed) Ottoman siege of Vienna in 1683 marked an important turning point. After withstanding several crises, the Habsburg state remade itself, creating new alliances and forces that eventually regained most territories once lost to their Ottoman rivals. Along the shores of the Adriatic and the eastern Mediterranean, a fleet of ambitious merchants and diplomats managed a Venetian empire that carved out its own sovereign realm separate from their Habsburg and Ottoman neighbors.

In the borderlands between these three empires, new military conflicts, trade patterns, and cultural exchanges developed in the early modern period. The regional capitals—Vienna, Istanbul, and Venice—became central nodes of extensive commercial, religious, and intellectual networks that extended across the eastern Mediterranean and the Balkans. Knowledge of multiple languages (German, Turkish, Greek, Italian, Albanian, Armenian, and Ladino, to just name a few) was a basic prerequisite for such exchanges across imperial borderlands. Amid increasing contacts, Western European mapmakers, writers, and travelers began to produce new depictions of Balkan realms, their rulers, and diverse inhabitants.

This collection of documents explores the connections that cut across Ottoman, Habsburg, and Venetian empires, from travel and trade to music and multilingual everyday life. Such sources direct our attention to the many ways in states and societies understood, negotiated, and communicated across linguistic, religious, and communal differences.

Essential Questions

- What can the sources tell us about the range of interactions between Ottoman, Venetian, and Habsburg Empires? How would you characterize their relations based on these different sources?

- Who are the intended audiences of these maps, depictions, and texts?

Centers of Empire: Istanbul, Vienna, Venice

The imperial capitals of Istanbul, Vienna, and Venice experienced new patterns of urban and commercial development in the early modern period.

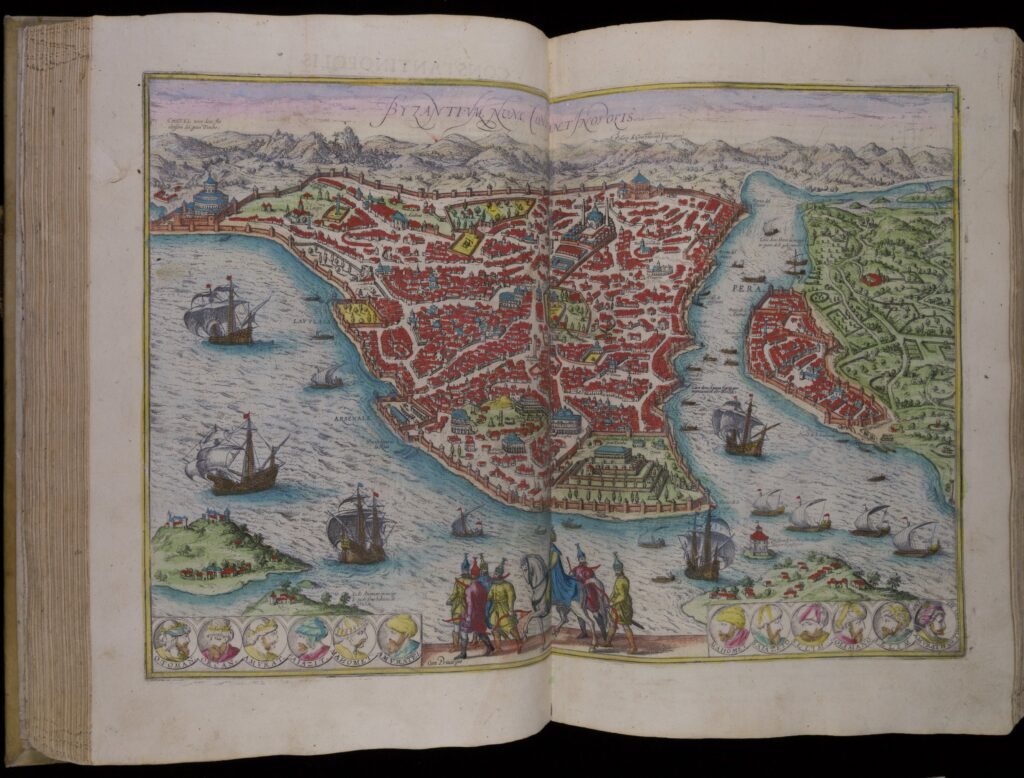

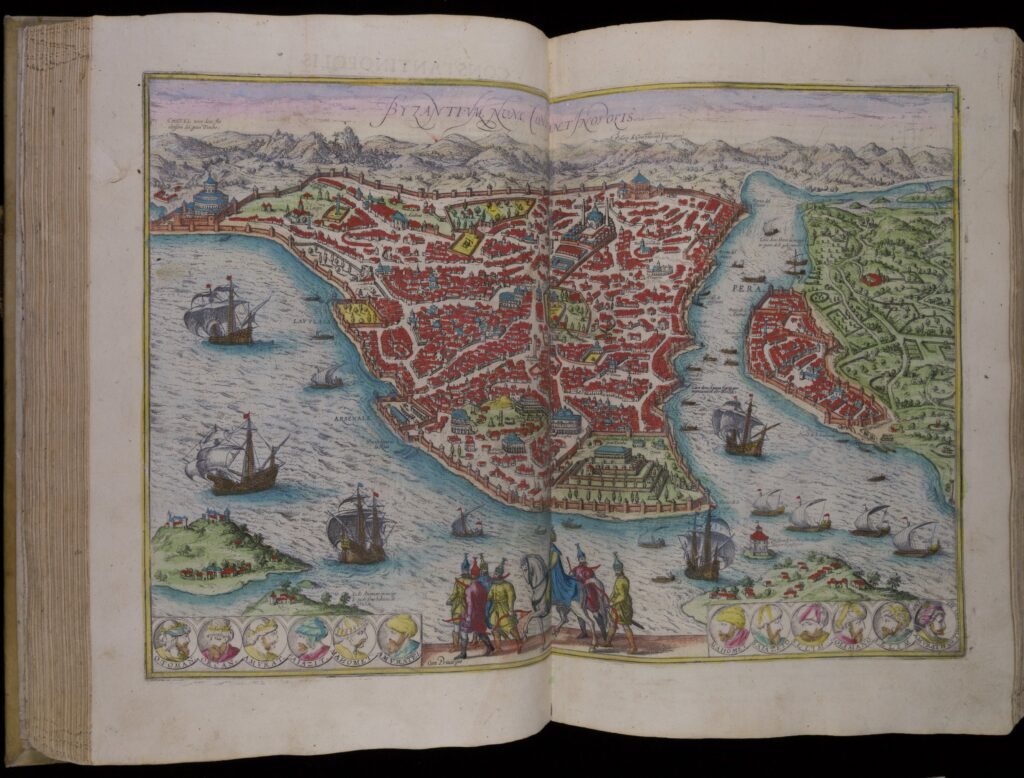

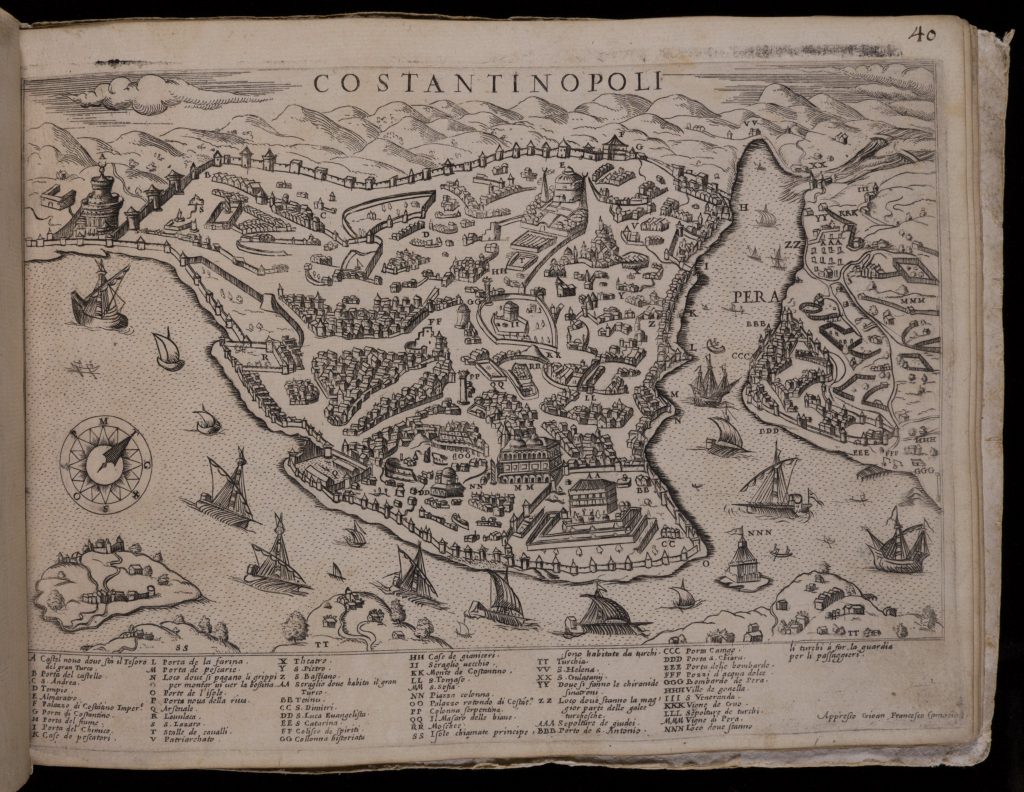

The transformation of Constantinople, once the capital of the Byzantine Empire, was especially striking. After the Ottoman conquest of the city in 1453, the population massively increased, reaching over half a million people by 1550s. Constantinople or Istanbul (the two names were used interchangeably) remained Europe’s largest city until the 1700s. New palaces, marketplaces, fountains, mosques, and other endowments were built as the Ottoman Empire expanded and acquired more wealth. The first item below shows how the European artist Georg Braun depicted Istanbul in 1570s (reproduced in 1620). His engraving showed prominent new Muslim landmarks like imperial mosques, several smaller churches, and locations of European trading outposts. The engraving’s belabored title—“Byzantium, now Constantinople”—reminded the viewer of the city’s Christian heritage while the portraits of ruling sultans illustrated the on-going development of the Ottoman dynasty.

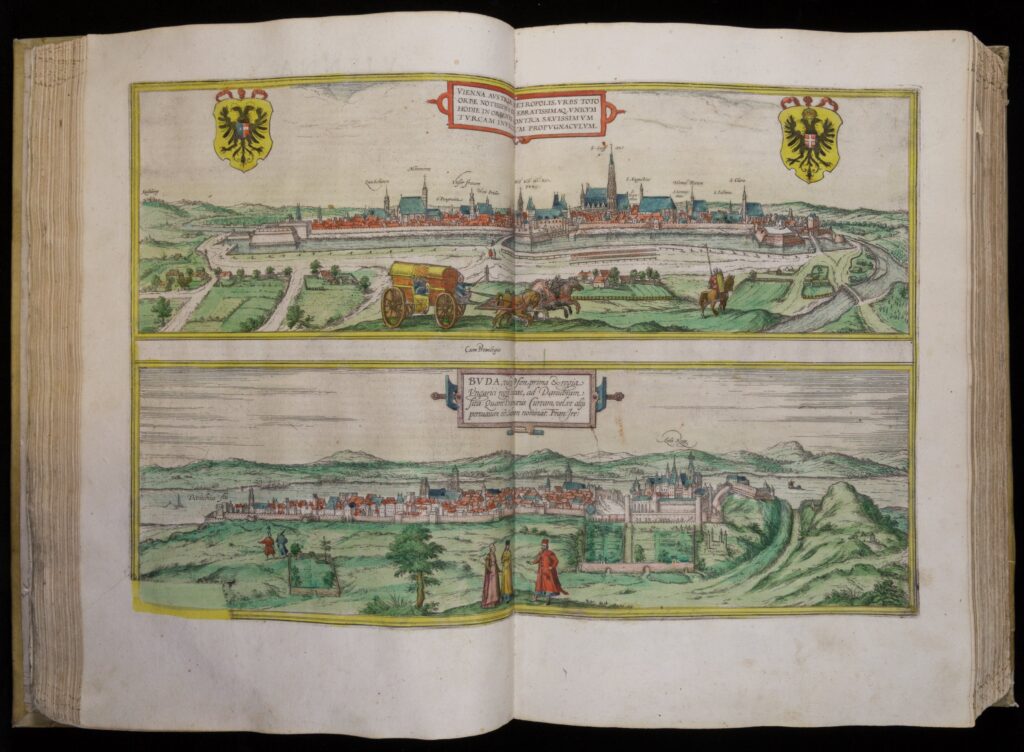

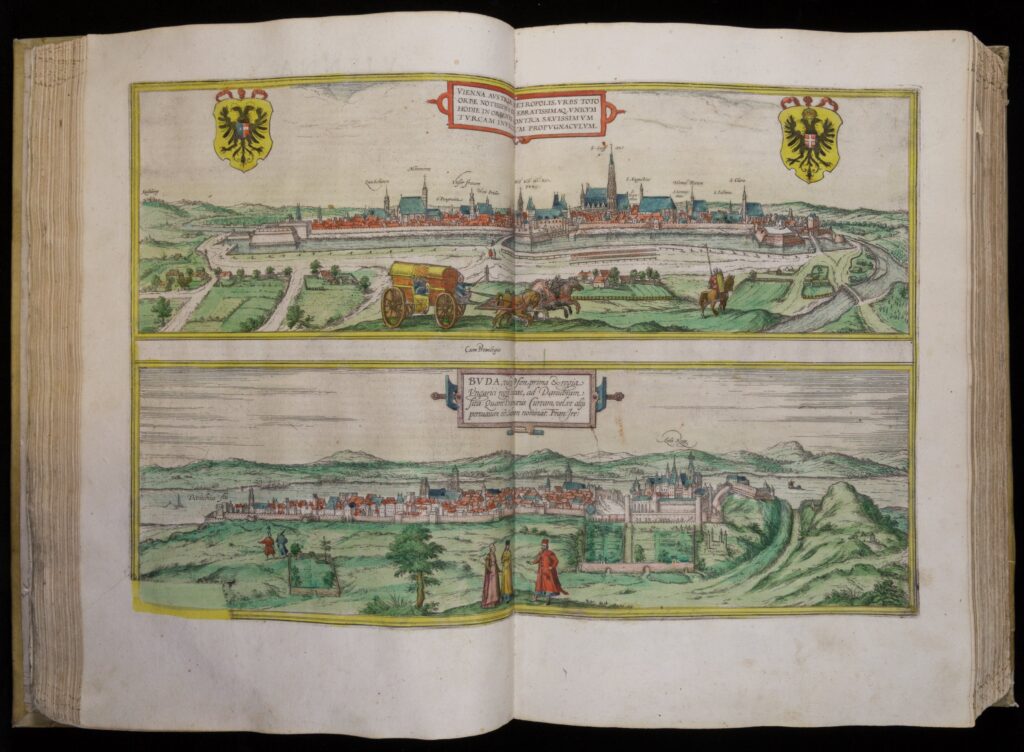

Vienna also established its own initiatives designed to demonstrate Habsburg resilience. The city not only withstood the Ottoman sieges in 1529 and 1683, but also became the seat of the far-flung Habsburg dynasty, with new imperial residences, churches, and public squares marking the urban landscape. Georg Braun, the same artist who produced the Istanbul depiction above, titled his 1573 depiction of Vienna as “the only bulwark against the savage Turks.” Alongside the prominently emphasized church spires towering above the city, Braun’s depiction also foregrounded the massive ramparts bounding the urban landscape.

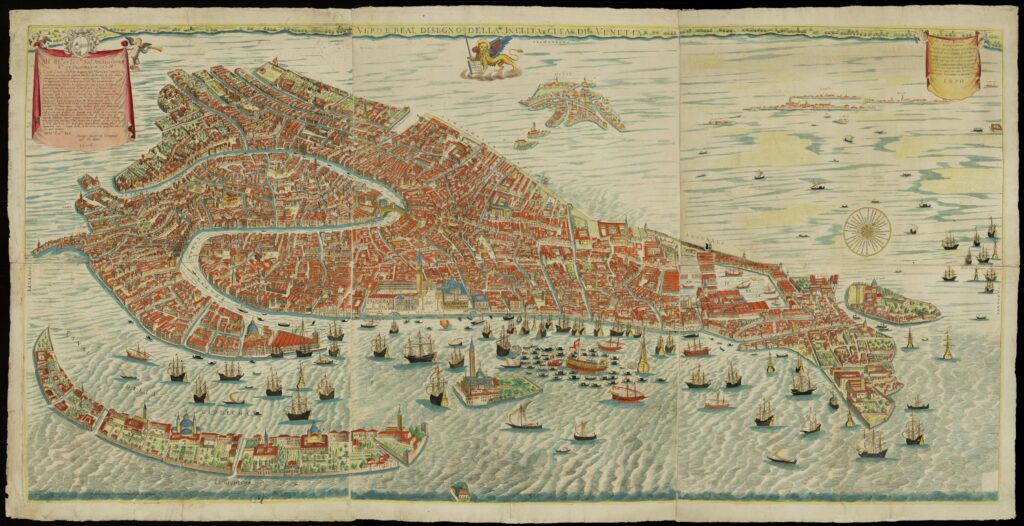

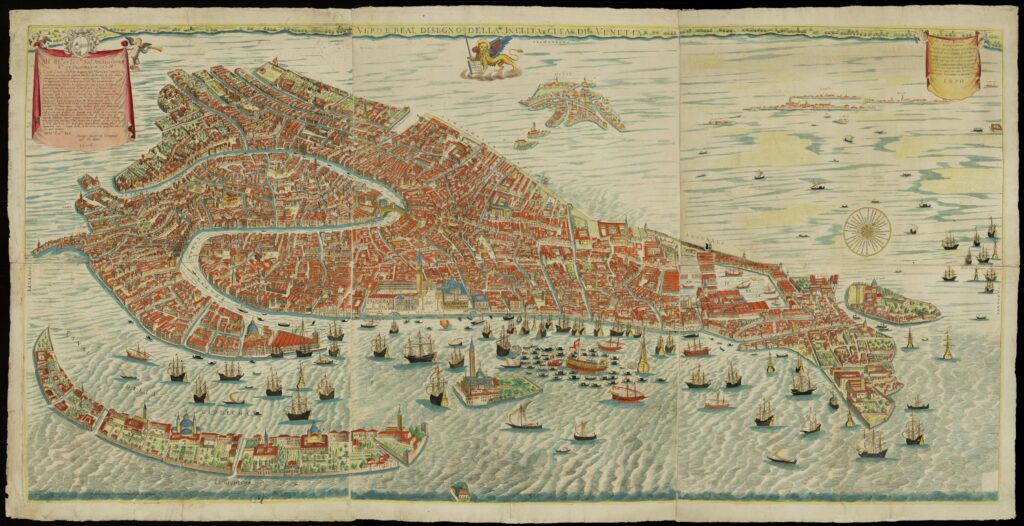

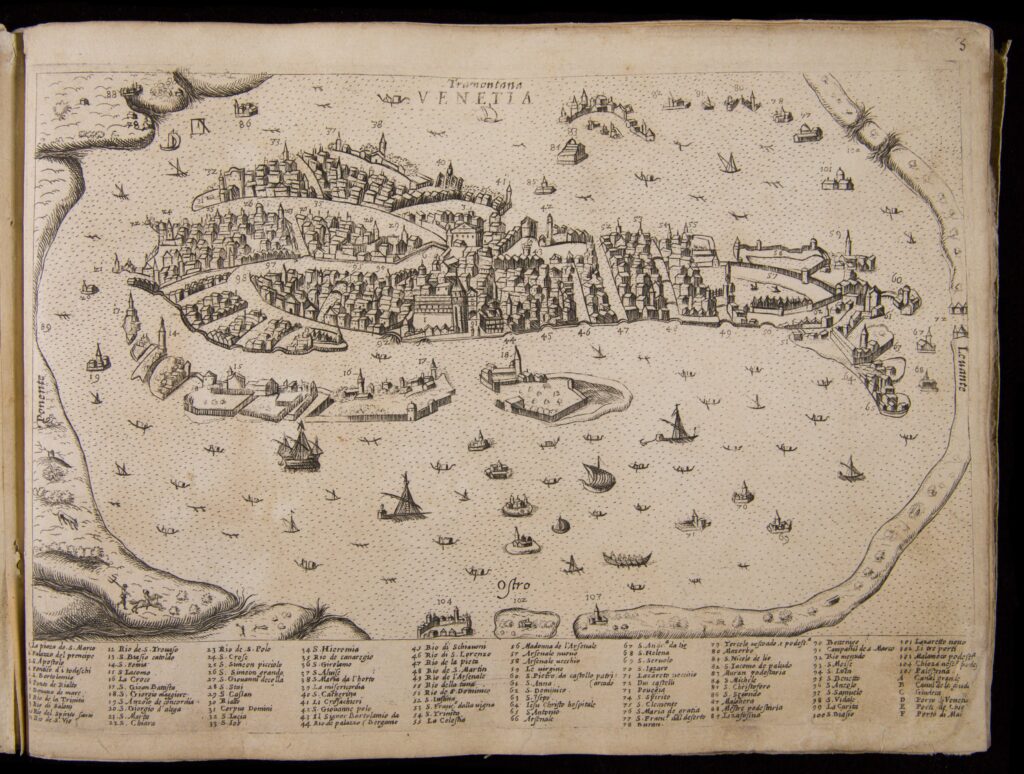

At the edges of the expanding Habsburg and Ottoman realms, Venice found new ways to assert itself as a powerful center of trade, culture, and diplomacy connecting the eastern Mediterranean with Central and Western Europe. Giovanni Merlo’s map (1677) conveys Venetian structures in rich detail. In addition to landmarks like the Piazza of San Marco, Merlo’s depiction also showed places where Jewish residents as well as Turkish, Greek, and German traders lived in this dense urban landscape.

Questions to Consider:

- What are some possible audiences of Georg Braun’s map of Istanbul in particular?

- What kind of impression does Braun’s map of Vienna leave? How do the maps of Vienna and Istanbul describe the Ottomans?

- What kinds of information does Merlo’s map of Venice convey about its urban life?

- Compare the depictions of Istanbul, Vienna, and Venice. Consider each map’s perspective: is it ground-level view, or aerial view, or some other angle? Note the design and the use of symbols and text. What similarities stand out in these maps? What differences do you notice between these depictions? What kinds of information are emphasized, what are not?

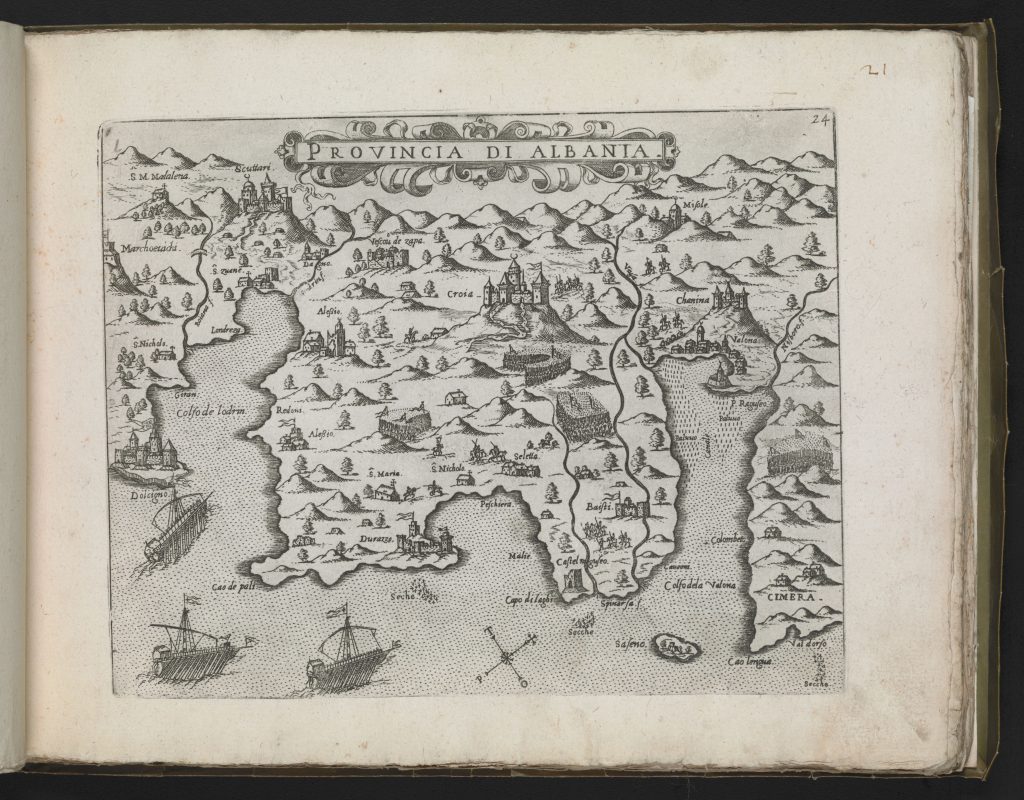

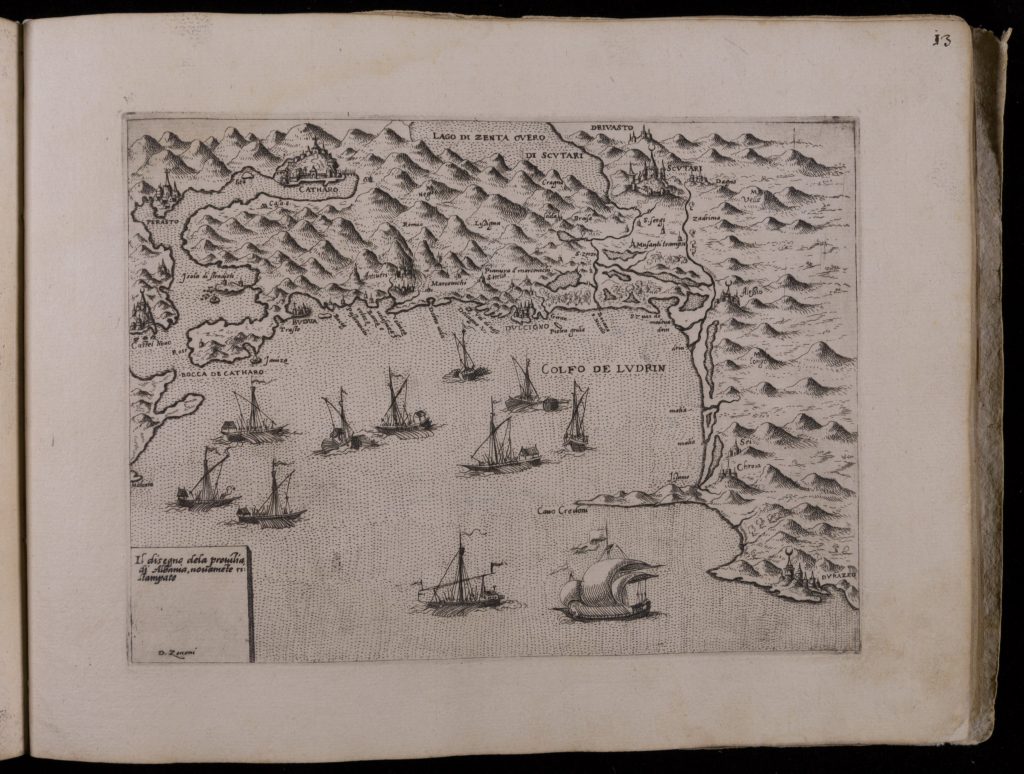

Imperial Wars and Exchanges

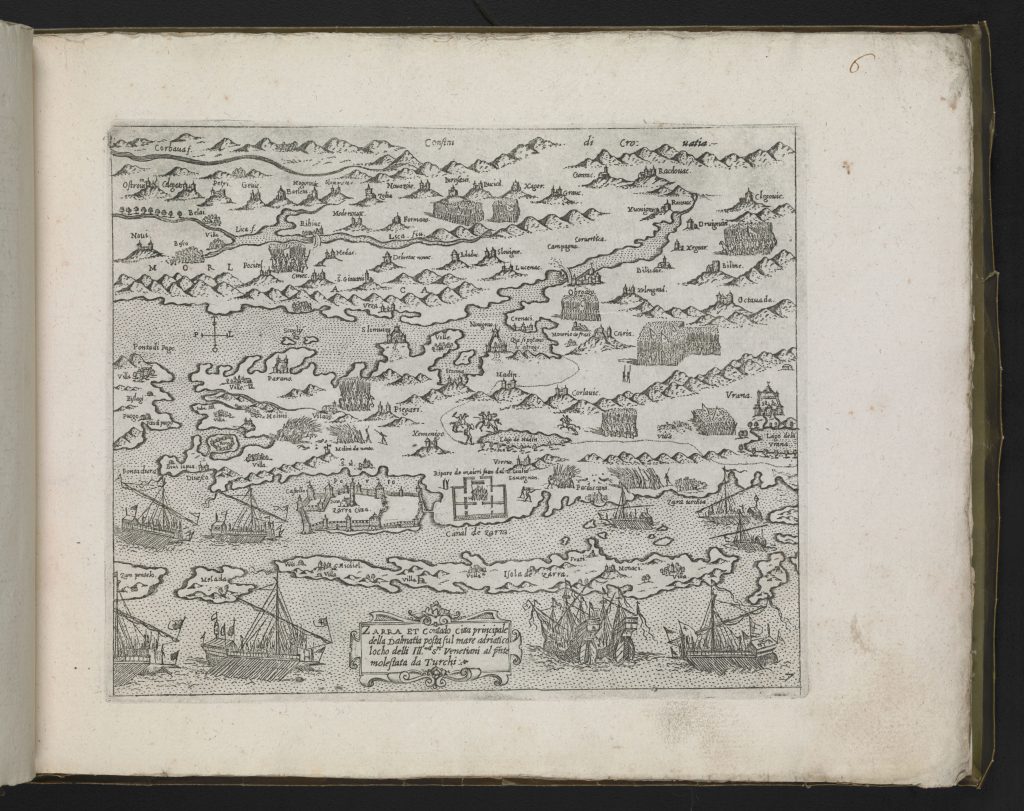

From the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, wars between the Ottoman, Habsburg, and Venetian empires brought these states and their subjects into ever-closer contact with each other. The first item below presents a series of maps of Venetian and Ottoman realms during the Venetian-Ottoman wars of 1571-1573. Composed by Venetian printers and mapmakers led by Giovanni Camocio, the maps begin with a view of the European continent and then zoom in on a series of islands, ports, and cities along the Adriatic and Aegean shores. The scenes show violent Ottoman-Venetian clashes in close confines around Dalmatia and on many Mediterranean islands. The boundaries between the Venetian and Ottoman sides are sometimes shown with faint dots, indicating that the borders in question were porous and subject to frequent revision.

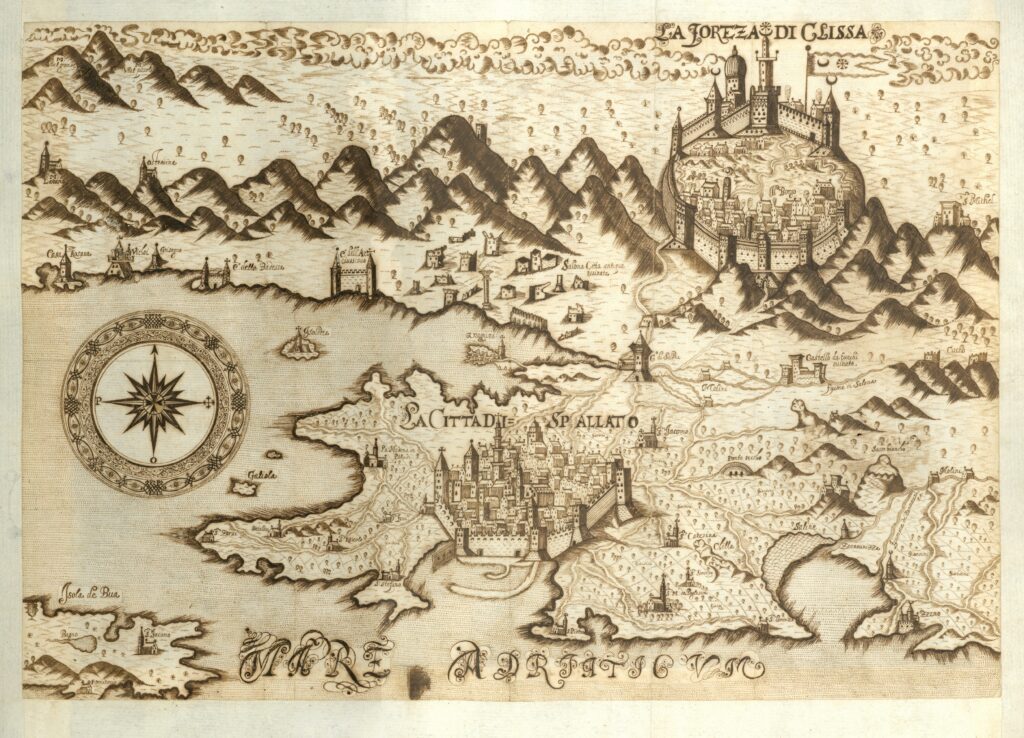

Selection: Giovanni Francesco Camcio, Isole famose porti, frortezze, e terre maritime sottoposte alla Serma Sigria di Venetia (1574)

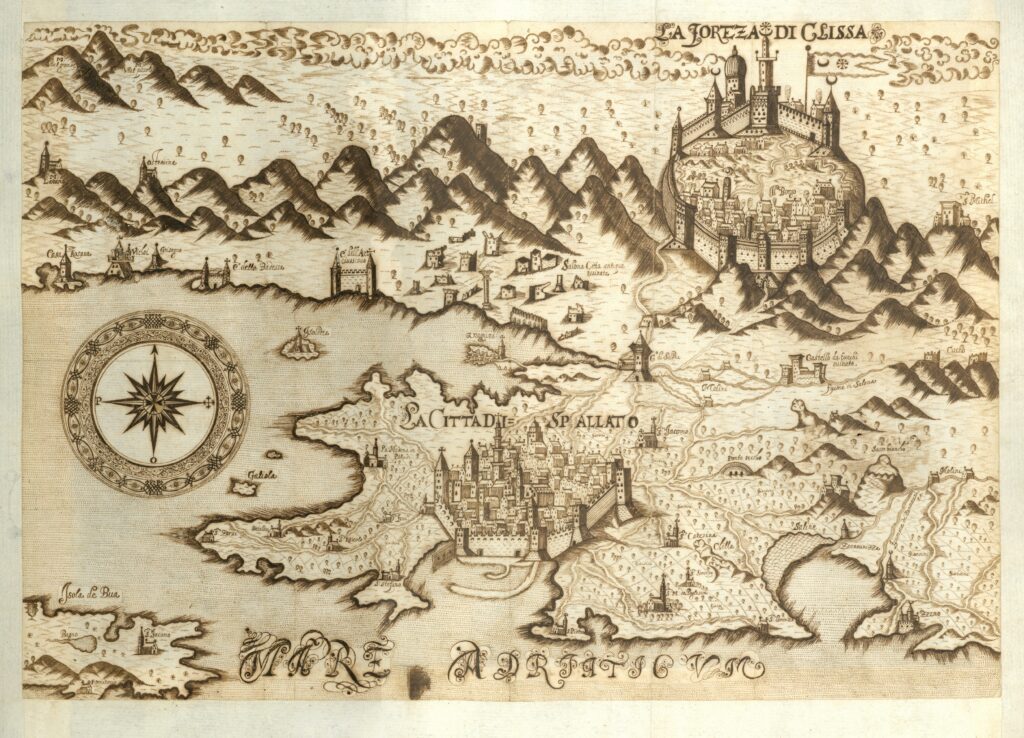

Ottoman, Habsburg, and Venetian subjects continued to live in close contact during and after such wars. Mapmaker Christof Tarnowski’s depictions of the Dalmatian coast shows several Ottoman and Venetian cities next to each other. For example, Tarnowski’s drawing below (1605) shows the Venetian-held city of Split (Spalatto) with roads that directly connect it to the nearby Ottoman town of Klis (Clissa). Each city’s fortifications were conspicuously drawn, but other borders are not emphasized.

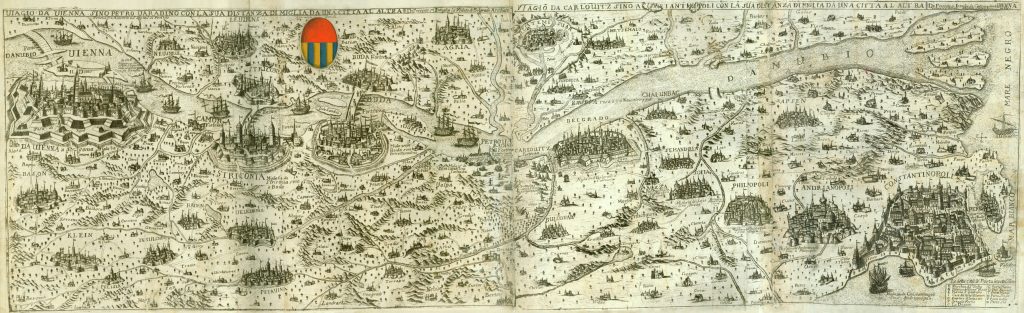

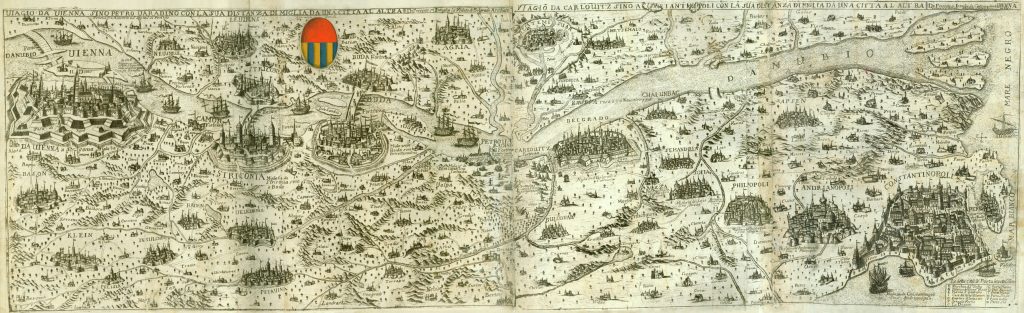

Travel along the Danube formed an especially important passage connecting Central European and Mediterranean domains. The Venetian mapmaker Stefano Scolari sketched how Danubian routes spanned a vast network stretching from Vienna (upper left corner) through Budapest and Belgrade and out to the Black Sea, from where ships could sail to Istanbul (lower right corner).

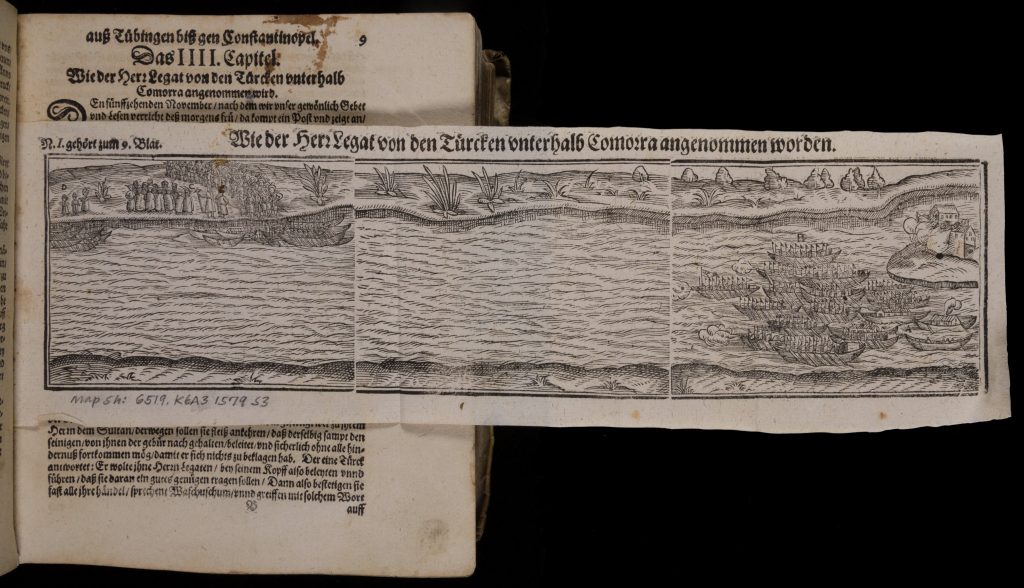

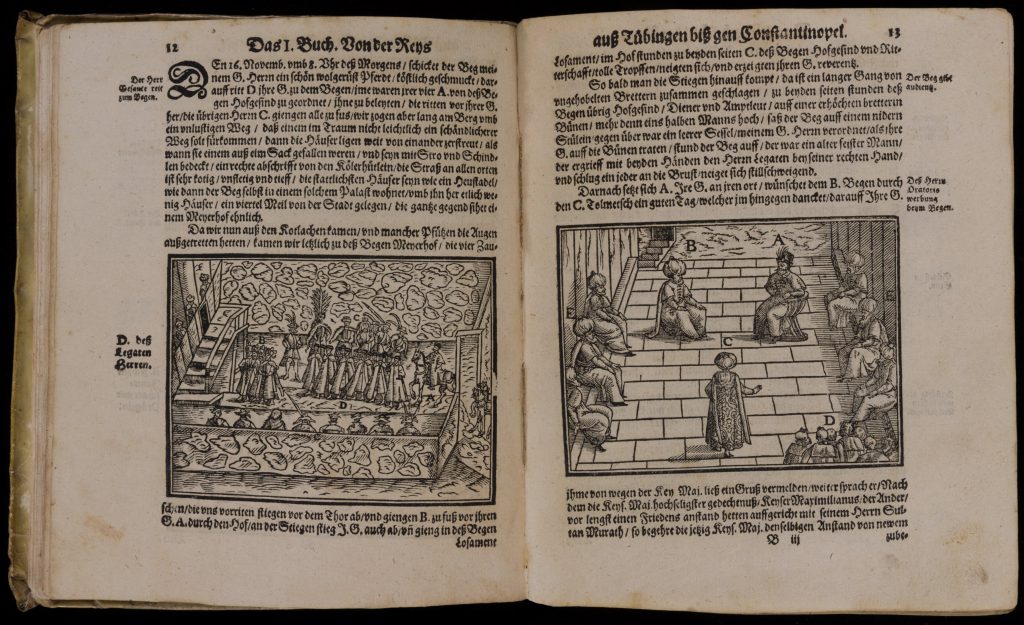

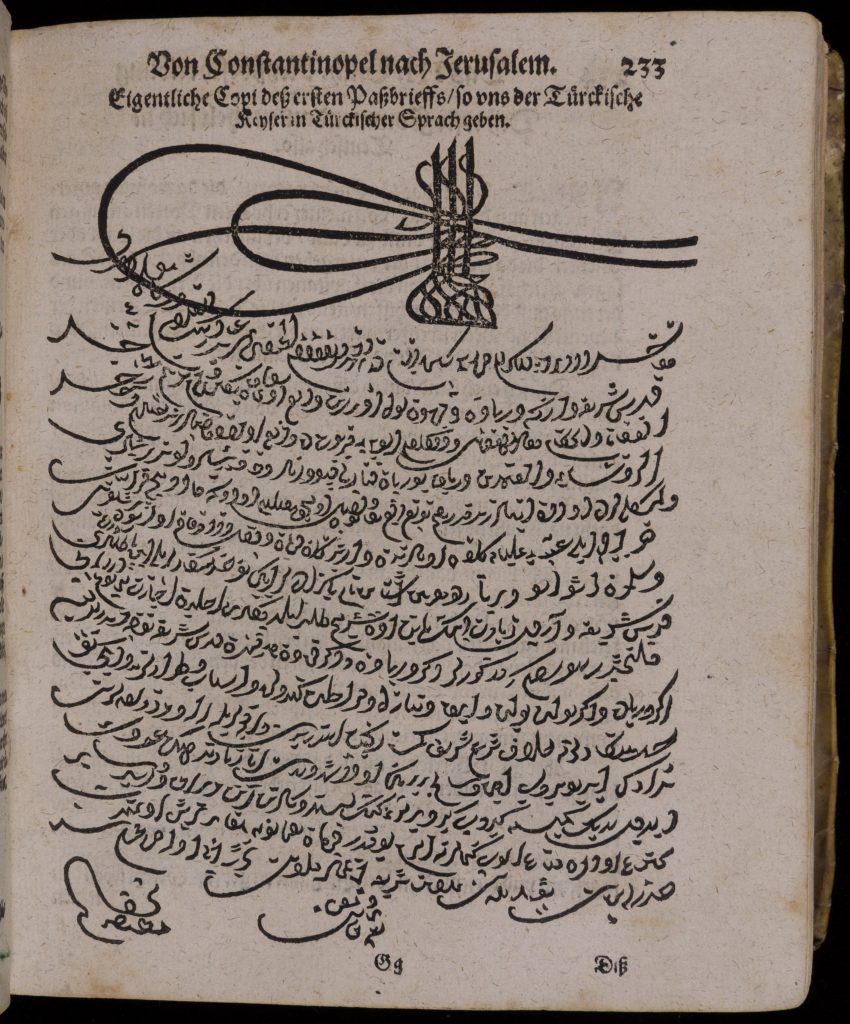

One such journey across the Balkans was undertaken by the German Lutheran priest Salomon Schweigger (1551-1622). His widely-read account included depictions of travel down the Danube and across Balkan regions before settling for years in Istanbul, where Schweigger studied Ottoman languages and customs in politics, trade, art, and music. After returning to Nuremburg, Schweigger published the first German translation of the Qur’an (which he translated from an Italian translation that appeared in Venice). Writings like those of Schweigger were parts of broader exchanges of knowledge connecting Ottoman, Habsburg, and Venetian publics of the early modern period.

Selection: Salomon Schweigger, Ein newe Reyssbeschreibung auss Teutschland nach Constantinopel vnd Jerusalem (1613).

Questions to Consider:

- What kinds of spaces and events stand out as especially important in Camocio’s maps? Why?

- How does Tarnowski depict the Ottoman- and Venetian-held domains in his map?

- Compare the maps of Camocio and Tarnowski. What impression of the Ottoman-Venetian borderlands do these maps convey?

- What uses or purposes could Scolari’s map of the Danube serve? For what audiences?

- What kinds of scenes and events does Schweigger’s account portray? Why were travel accounts like Schweigger’s so important for Central European audiences?

Language use across Ottoman-European borderlands

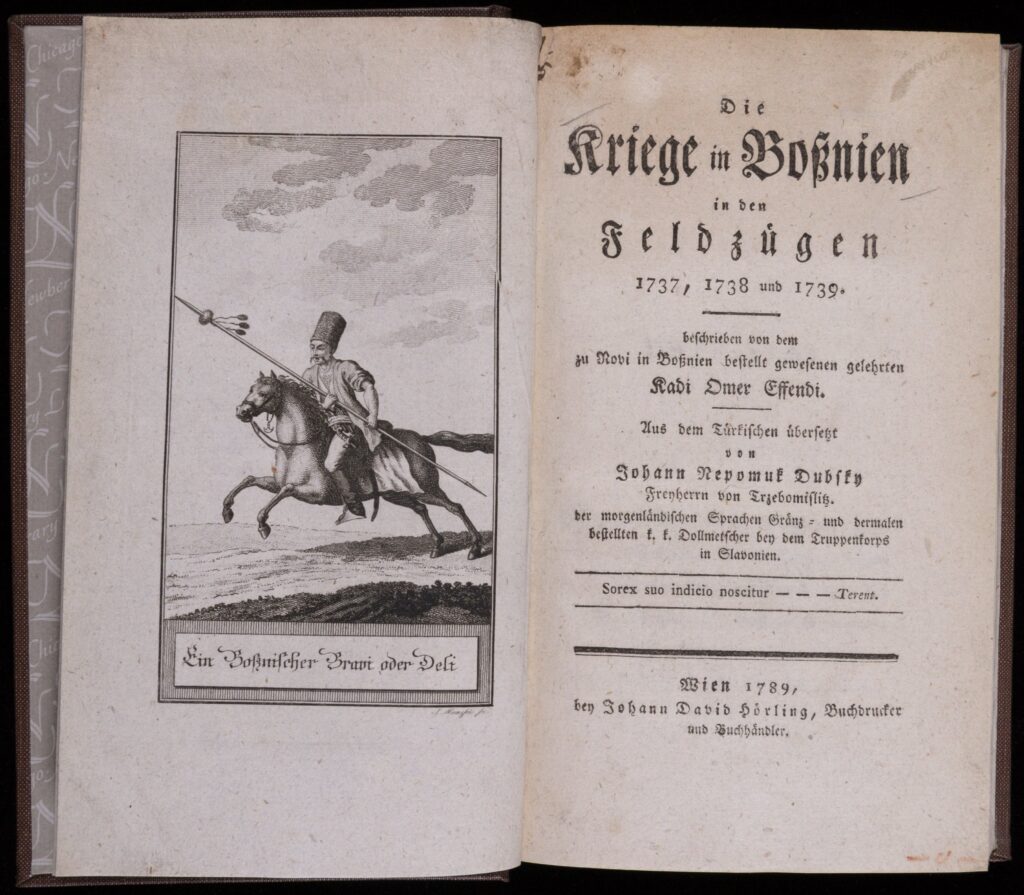

While engaging in wars, negotiations, and trade, Habsburg, Venetian, and Ottoman imperial officials and local subjects began to amass extensive bodies of knowledge about their enemies and partners along the Balkan borderlands. New printing presses began to publish chronicles, maps, travel guides, and multilingual dictionaries for these European borders. As the items below show, when the Istanbul authorities printed an account of the Habsburg-Ottoman fighting in Bosnia in 1737-1739, the Austrian officials translated and published it in the wake of another round of borderland conflict in 1789. Building on this German work, an English translation of the Ottoman chronicle appeared in London in 1830, widening the circulation of works beyond to audiences outside of southeastern Europe.

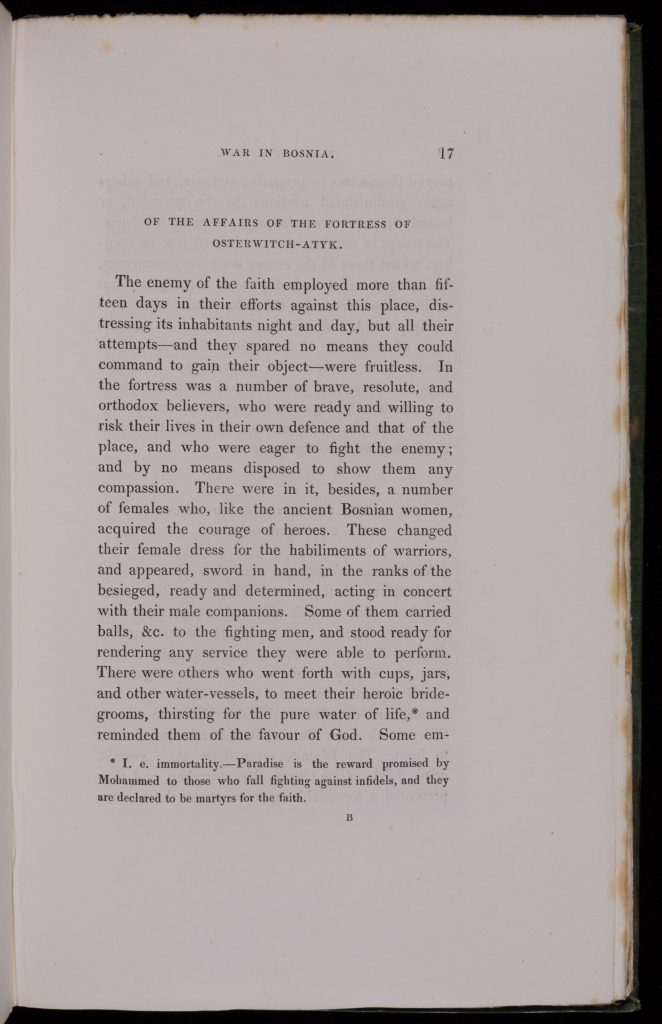

Selection: Kadi Omer Efendi, History of the War in Bosnia, During the Years 1737-1738 and 39, German title page and frontispiece (1789) and English translation (1830).

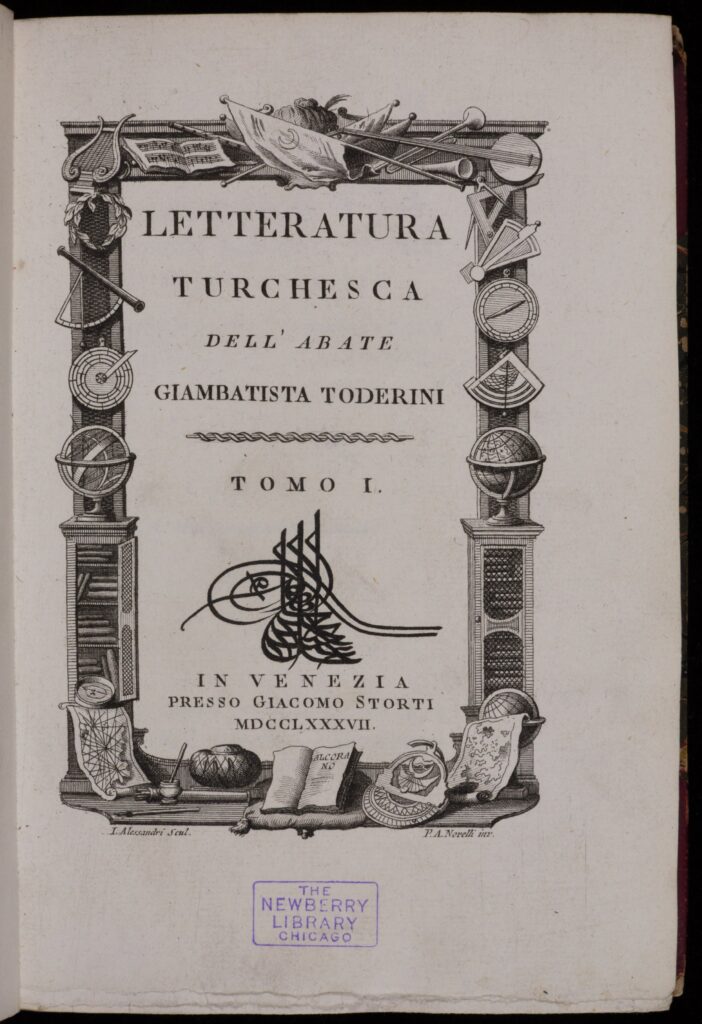

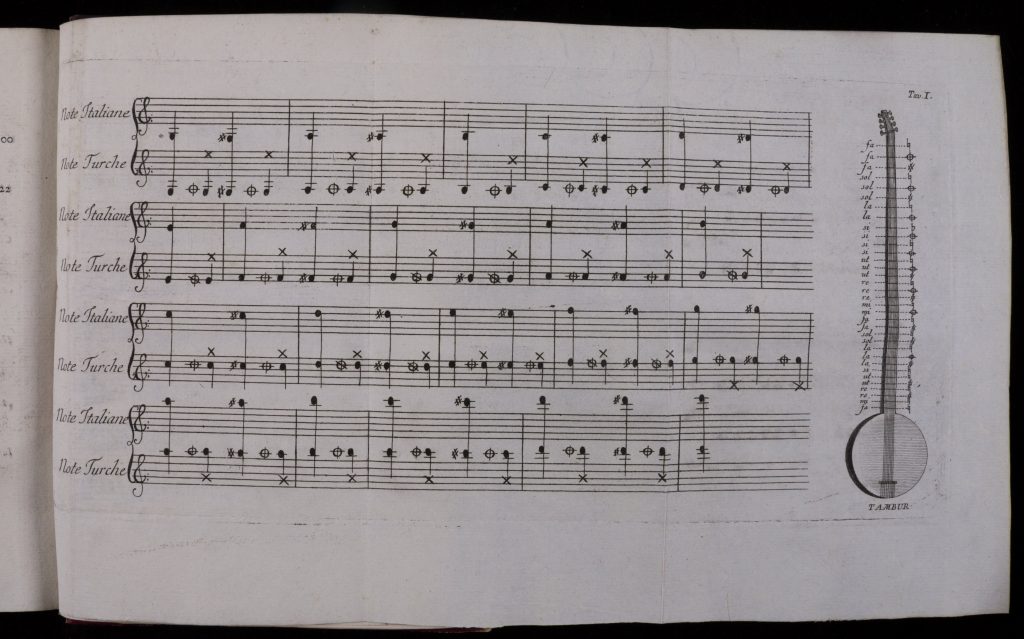

Even as Habsburg power increased at the expense of the Ottomans and Venetians in the eighteenth century, Venice remained a critical point for networks connecting different imperial realms and local languages. The Jesuit abbot Giambatista Toderini, for example, used his five-year-long residence at the Venetian embassy in Istanbul to study Ottoman manuscripts on politics, philosophy, mysticism, and everyday culture. Toderini published his Italian translations of Ottoman works as a three-volume introduction to “Turkish literature” in 1787. The book outlined a broad array of Ottoman subjects, from theology to natural sciences to jurisprudence to music, in which Toderini expressed particular interest.

Selection: Giambattista Toderini, Letteratura turchesca (1787).

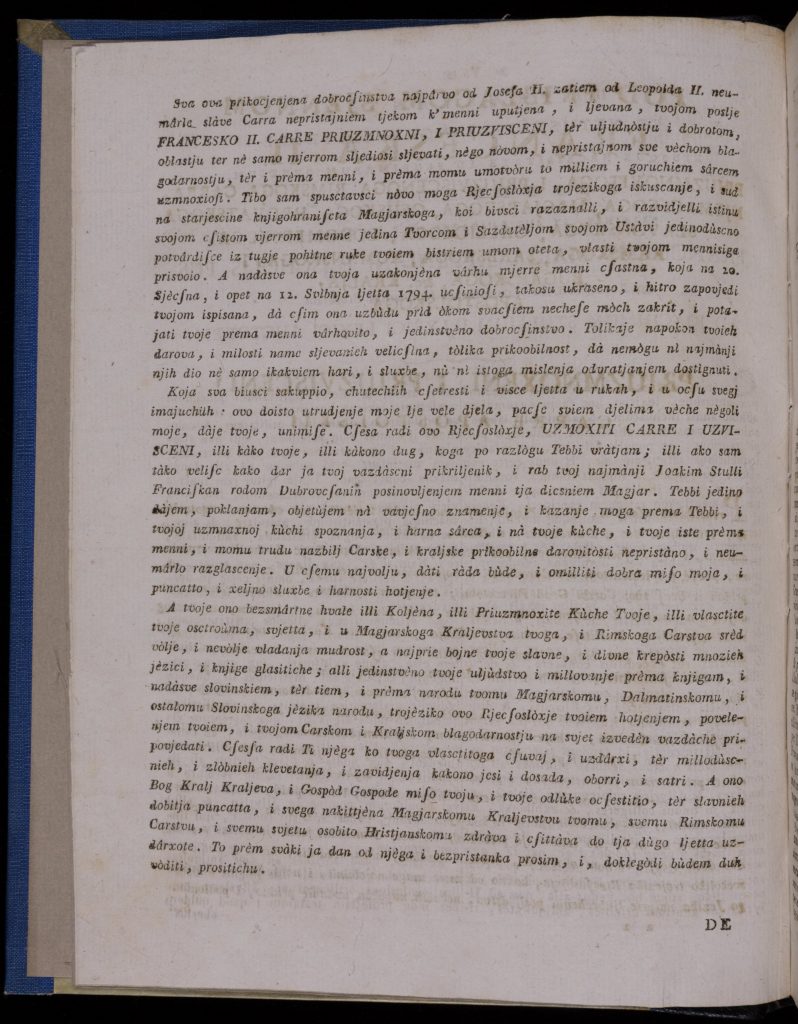

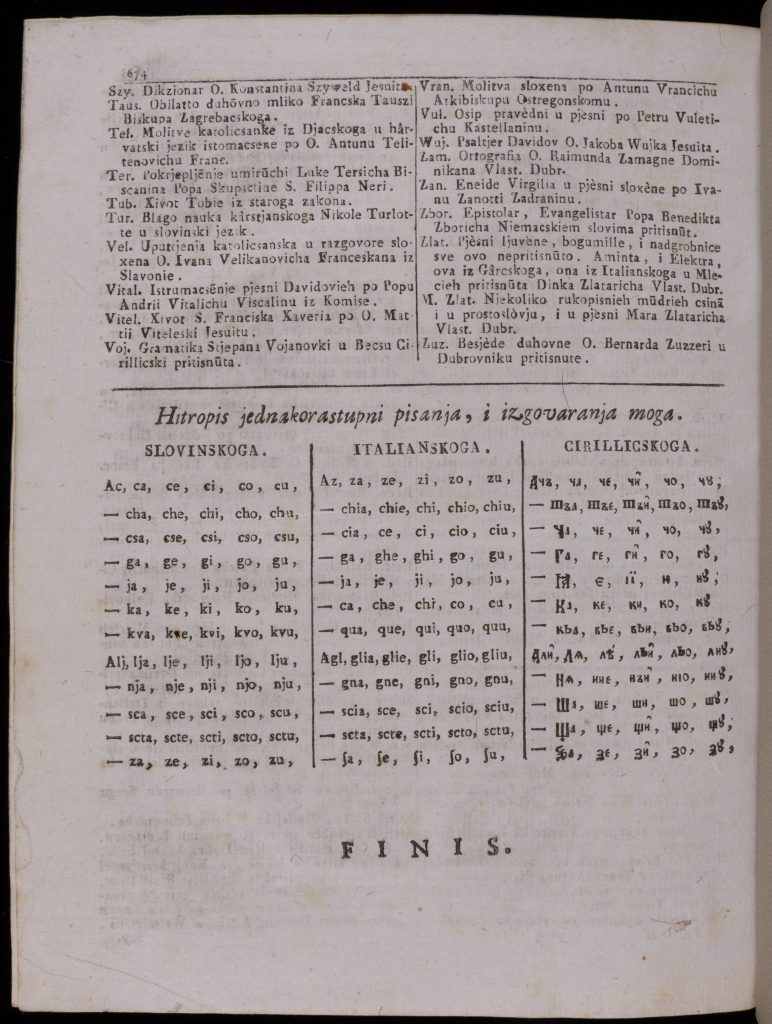

Across southeastern European borderlands, multilingualism was the norm rather than the exception. Publications like dictionaries and prayer books illustrate the wide span of languages in everyday use across Habsburg, Venetian, and Ottoman domains. The Franciscan priest and lexicographer Joakim Stulli, for example, compiled a dictionary reflecting the main literary traditions in his native city of Dubrovnik in Dalmatia: Italian, Latin, and “Illyrian” (meaning the common Serbo-Croatian language of the South Slavs). Stulli secured funds for his lexicographic enterprise in Vienna “by the grace of the Habsburg emperor, Francis II,” reflecting imperial support for multilingual projects across its empire.

Selection: Joakim Stulli, Dubroscania… Rejecsoslòxje ukomu donosuse upotrebljenia, urednia, mucsnia istieh jezika krasnoslovja nacsini izgovaranja i prorjecsja (1806)

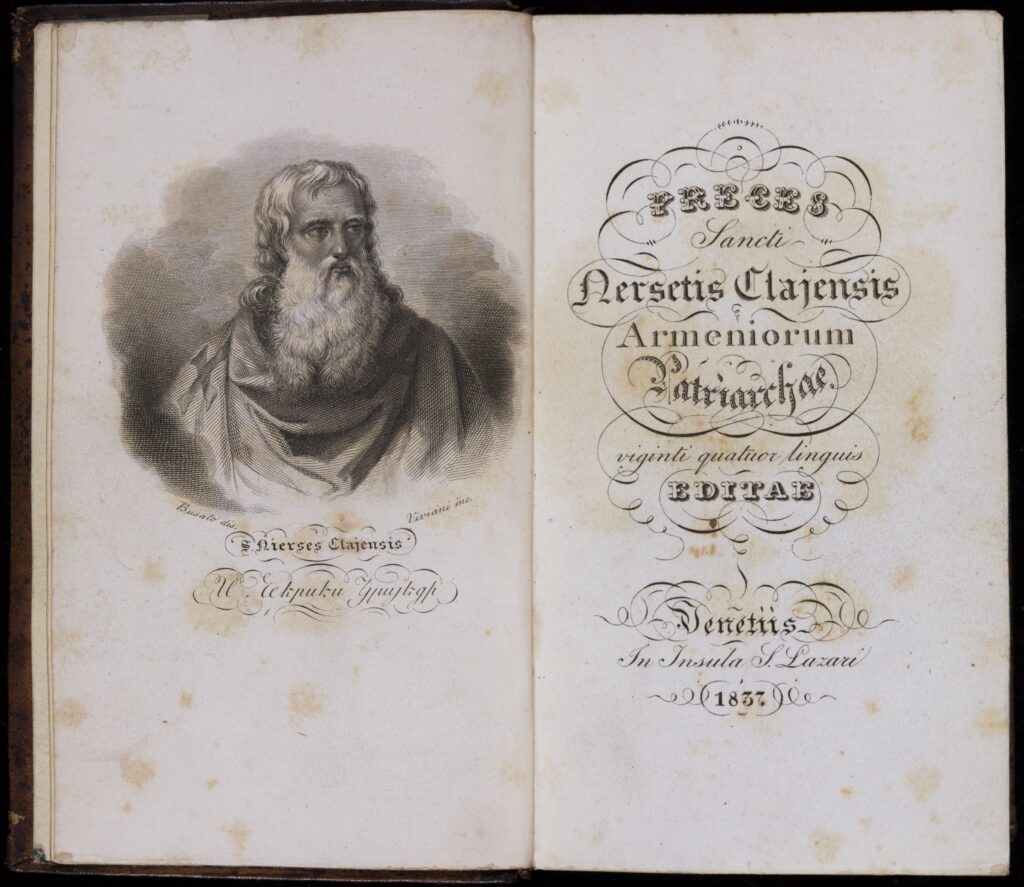

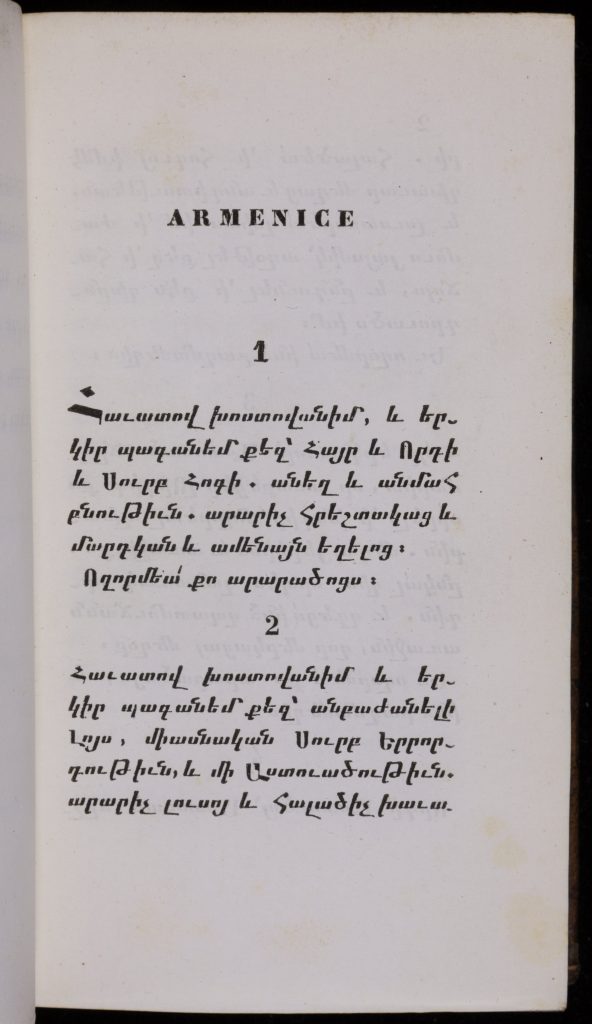

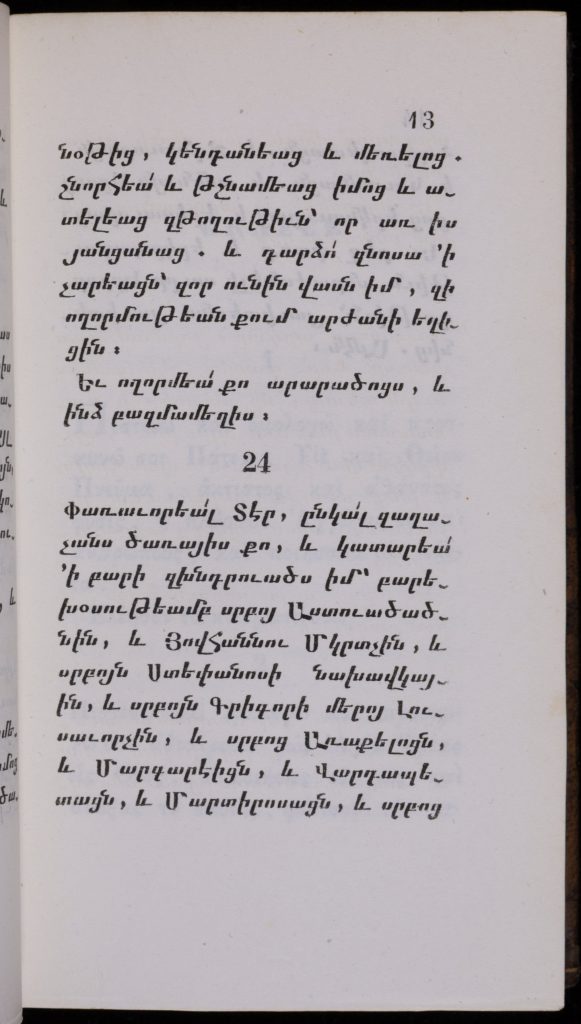

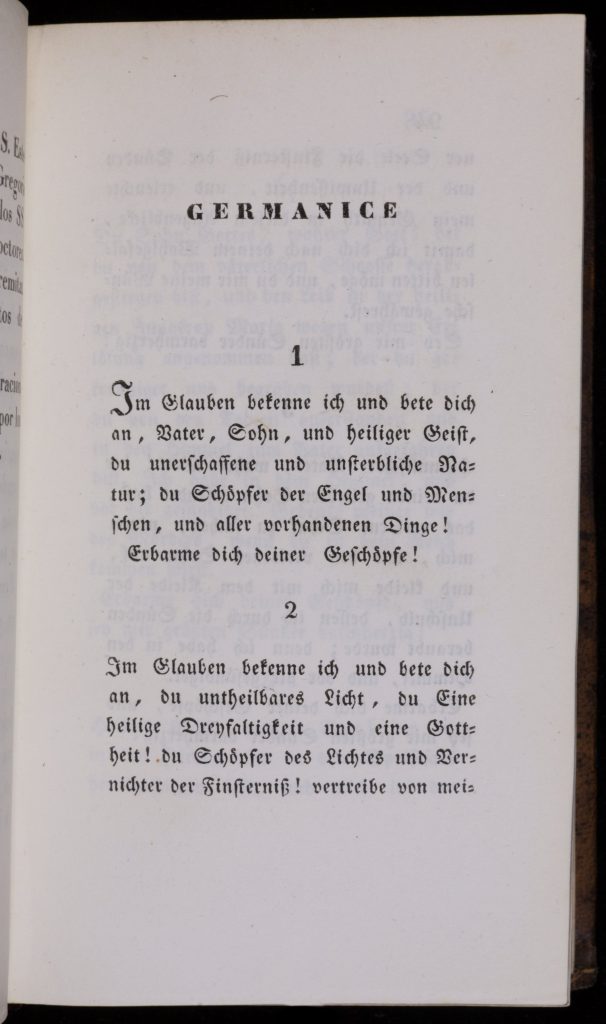

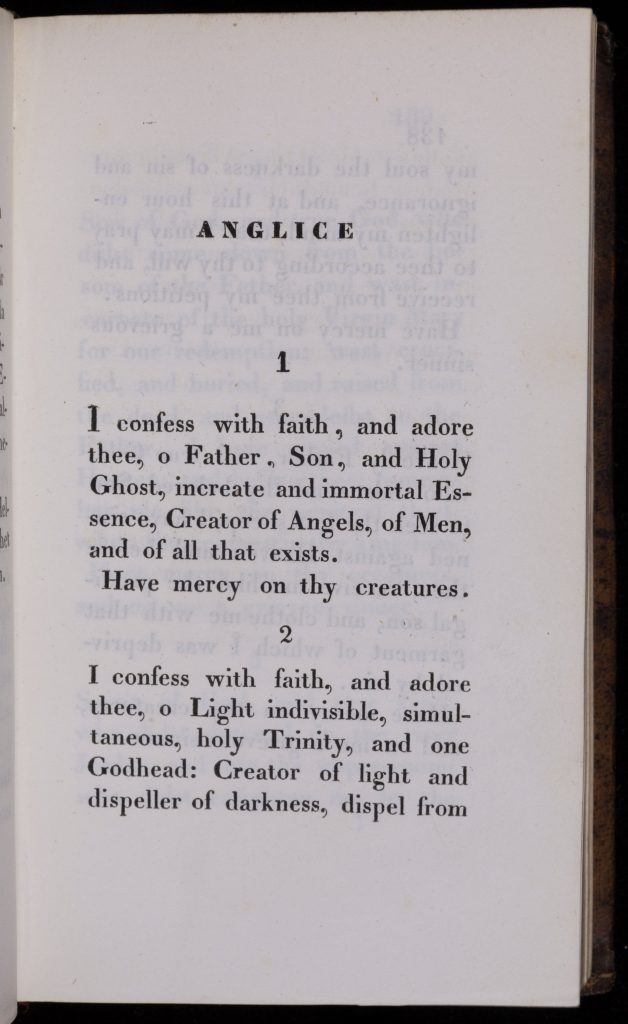

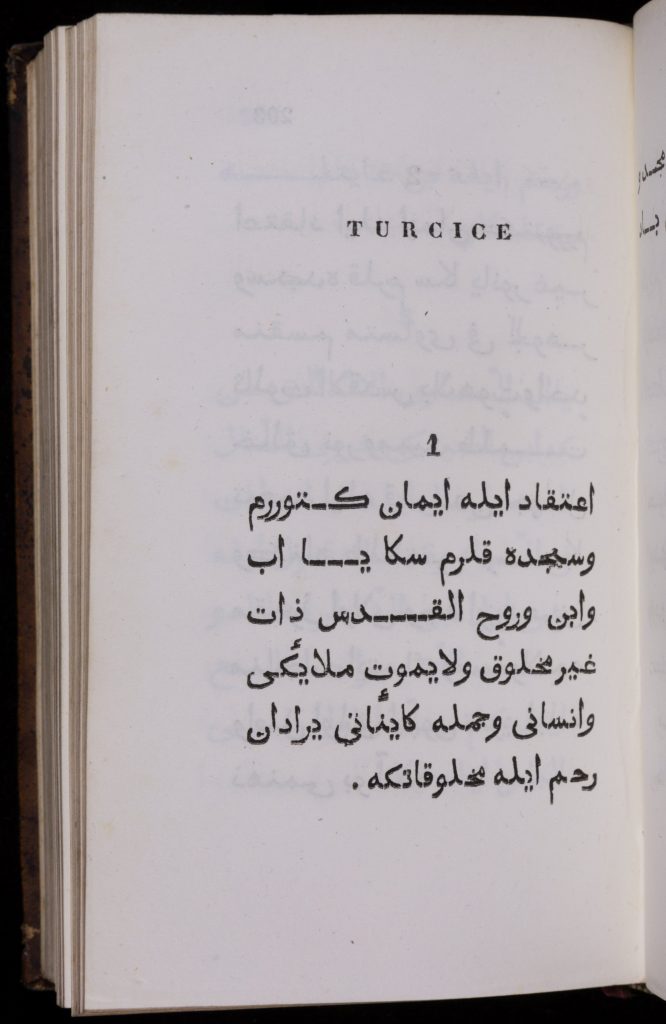

Prayer books were often multilingual. The Catholic monastic order of Mekhitarists began as a movement among Ottoman Armenians before establishing new central monasteries in Venice and Vienna. Reflecting these trans-imperial and multilingual histories, the Catholic Mekhitarist prayer books published in Venice not only contained Armenian (the dominant language of the order), but also a wide array of scripts and languages: Greek, Italian, Spanish, German, English, Russian, Polish, Hungarian, Arabic, and Turkish, to name just a few.

Selection: Preces Sancti Nersetis Clajensis Armeniorum patriarchae, viginti quattuor linguis ed (1837).

Questions to Consider:

- The Ottoman account of the 1737-1739 Ottoman-Habsburg war over Bosnia was first translated into German in Vienna; the German translation was then translated into English. What different audiences can you imagine for each book (the original and the translations)?

- In the excerpt, Omer Efendi describes the Ottoman-Habsburg war in Bosnia from an Ottoman perspective. According to him, who participated in the Ottoman defenses of key fortresses? What kind of conflict does this excerpt depict?

- Why would European audiences be interested in “Turkish literature” (from philosophical to musical) provided by Toderini in 1787? What could they learn from such an account?

- What uses or audiences can you imagine for Stulli’s dictionary? Why would the Habsburg imperial administration be willing to support such publications?

- What does the range of languages in the Mekhitarist prayer book convey about the reach of this Armenian monastic order? How would such multilingual prayer books be used and by whom?

Visualizing Imperial Subjects

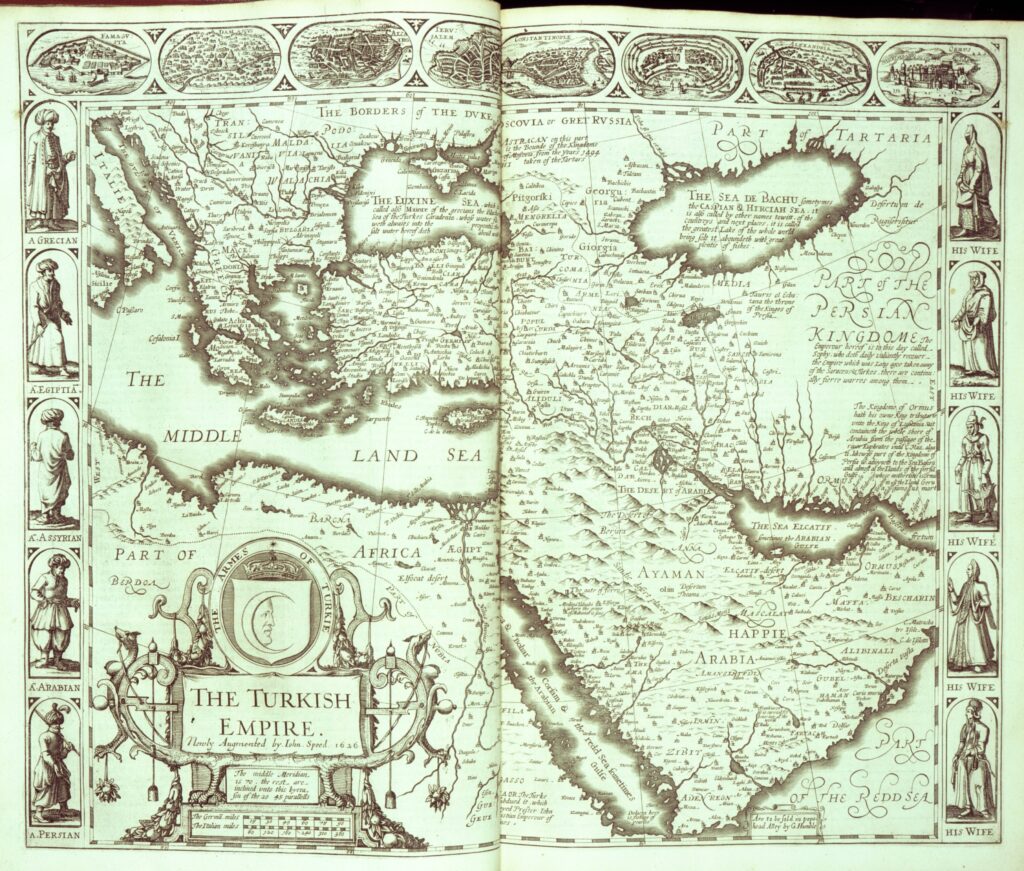

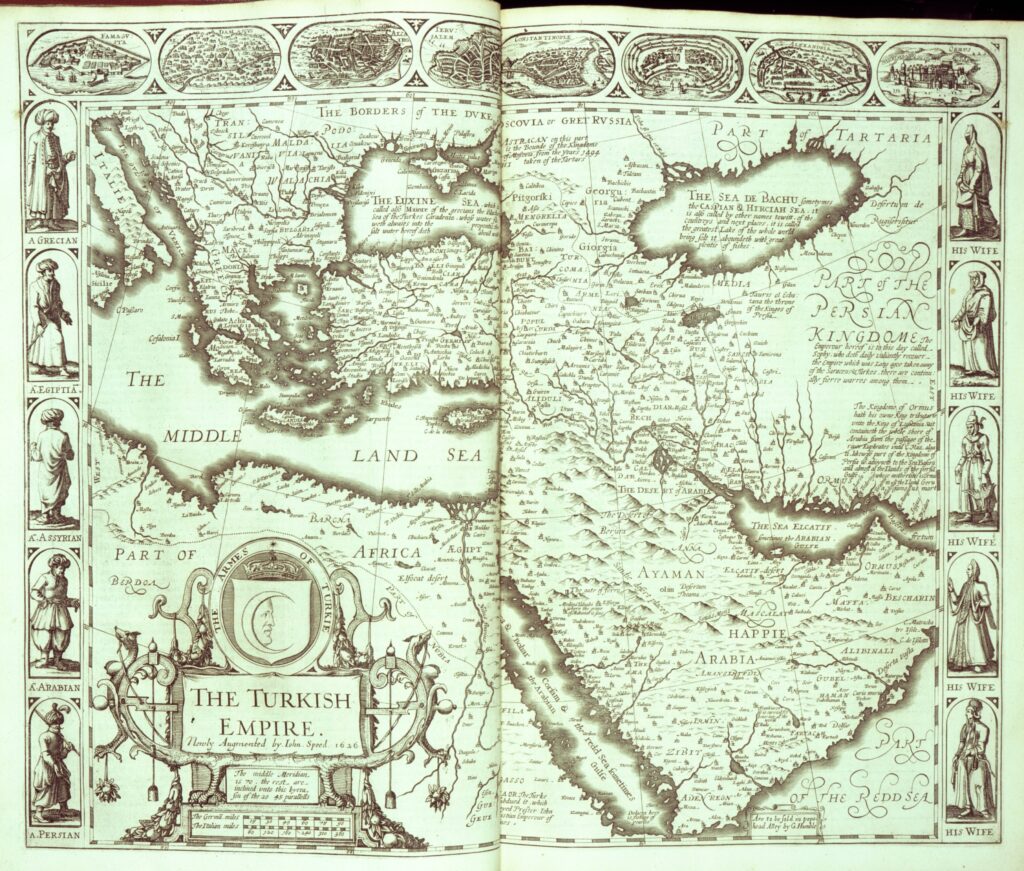

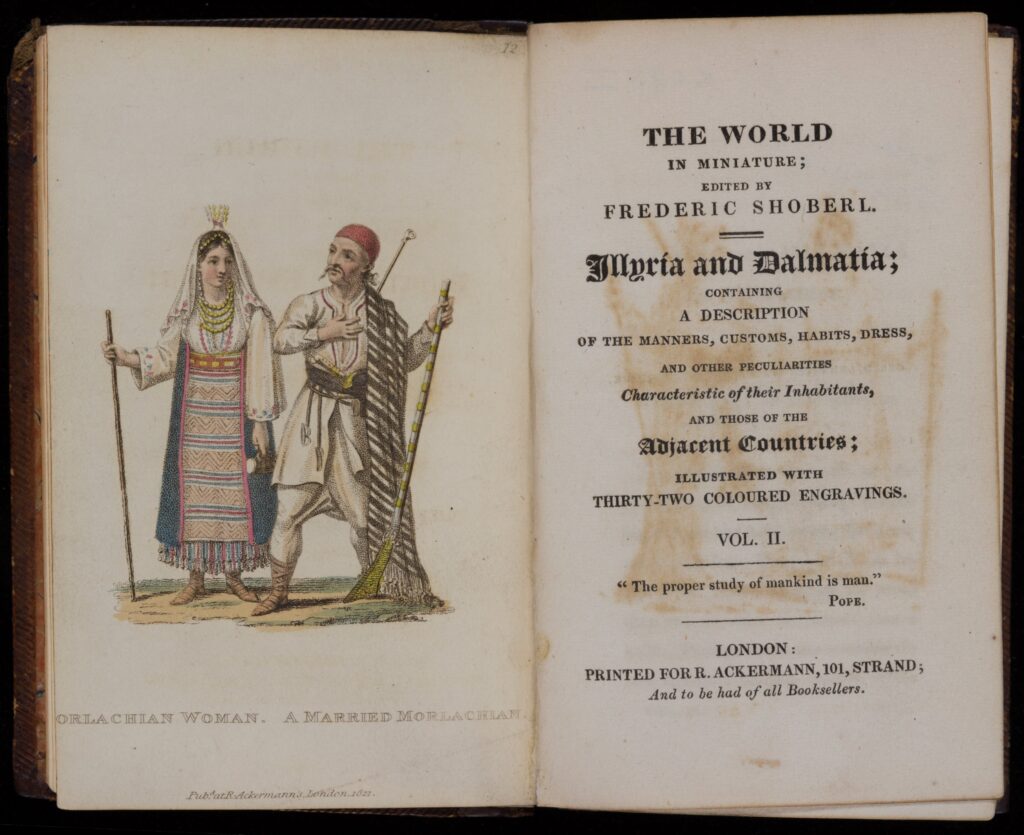

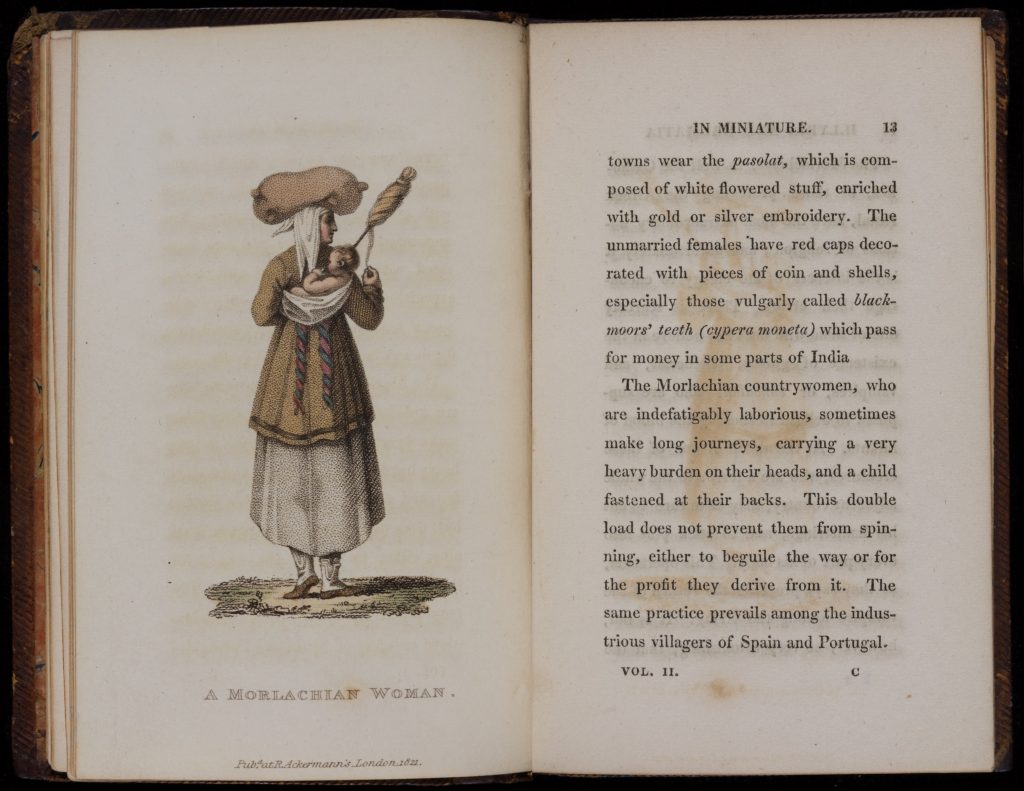

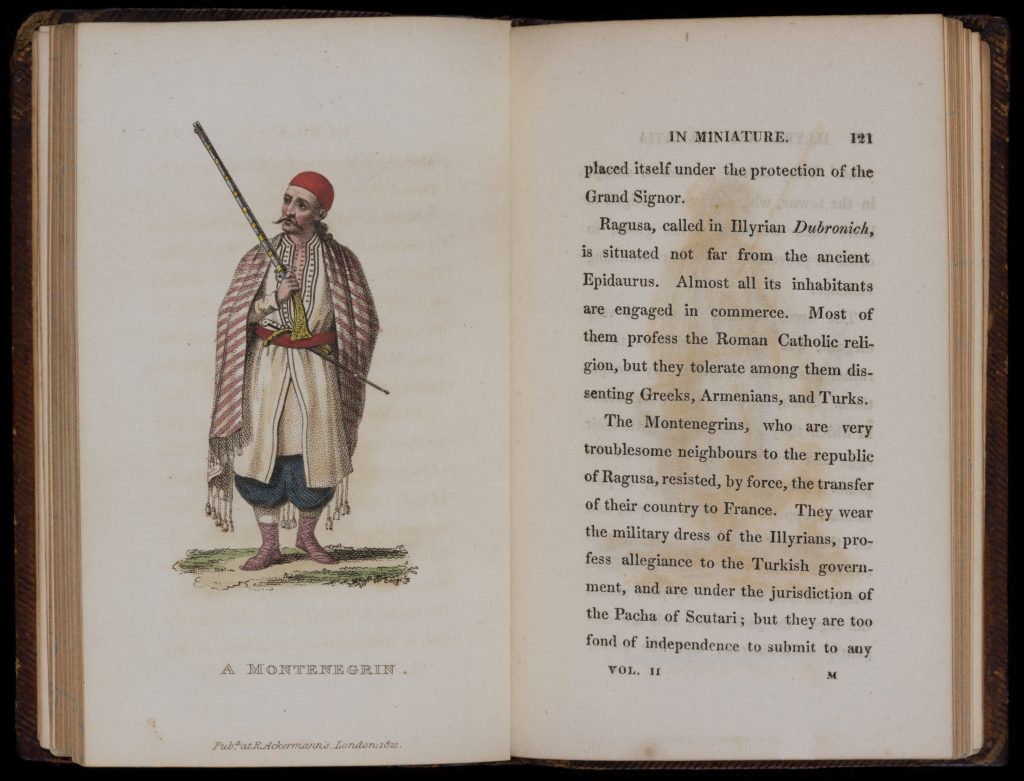

The imperial contestations and cultural exchanges across southeast European borderlands attracted considerable interest in Western Europe. English, German, and French mapmakers depicting the Ottoman Empire often included depictions of imperial subjects in a variety of “Turkish” costumes. John Speed’s 1676 map of the Ottoman Empire, for example, used the margins to display “natives in local costume” (with men on the left and women on the right side of the chart). Travel guides, like those printed by Frederic Shoberl in the 1810s, continued to draw the English reader’s attention to the “peculiarities characteristics” of Dalmatian and Balkan lands and inhabitants, including their “manners, customs, habits, and dress.”

Selection: Frederic Shoberl, Illyria and Dalmatia (1821).

Questions to Consider

- What kinds of imagery does Speed use in his depiction of the Ottomans? What aspects are emphasized?

- How do Shoberl’s depictions reflect the interests of the European artists and audiences? In the excerpt, how does Shoberl describe the relations between the Turks and the Dalmatian residents (“Likanians”)?

Further Reading

Natalie Rothman, Brokering Empire: Trans-Imperial Subjects between Venice and Istanbul (2011).

John Stoye, Marsigli’s Europe, 1680-1730: The Life and Times of Luigi Ferdinando Marsigli, Soldier and Virtuoso (1994).

Robert Dankoff, An Ottoman Mentality: The World of Evliya Çelebi (2006).

Maria Todorova, Imagining the Balkans (1996).

James Krokar. The Ottoman Presence in Southeastern Europe, 16th-19th Centuries: A View in Maps (1997).

Wendy Bracewell, ed. Orientations: An Anthology of East European Travel Writing, ca. 1550-2000 (Budapest, 2009).