Introduction

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the city of Chicago was an increasingly complex urban environment. From 1880 to 1900, the population doubled from 500,000 inhabitants to over one million. Railway lines radiated out from Chicago to deliver a wide array of goods to people throughout the Midwest and beyond. As witnesses to these trends, writers in Chicago often experienced these changes in contradictory ways. On the one hand, there was a prevalent sense that the city was ruled by the spirit of commerce and gain, making it inhospitable to art. To these writers, the city seemed violent and chaotic, in a state of perpetual decline. On the other hand, the city was a place of opportunity and innovation. Many Chicago writers, like Ben Hecht, got their start in the city before moving on to prosperous careers in Hollywood or New York.

Essential Questions:

- What are the different ways that each document describes and depicts the city? How do these different representations of the city compare to one another?

- Which elements of urban life seem to be the most threatening or dangerous? Is the city always portrayed as being violent and chaotic? What are alternatives to these depictions?

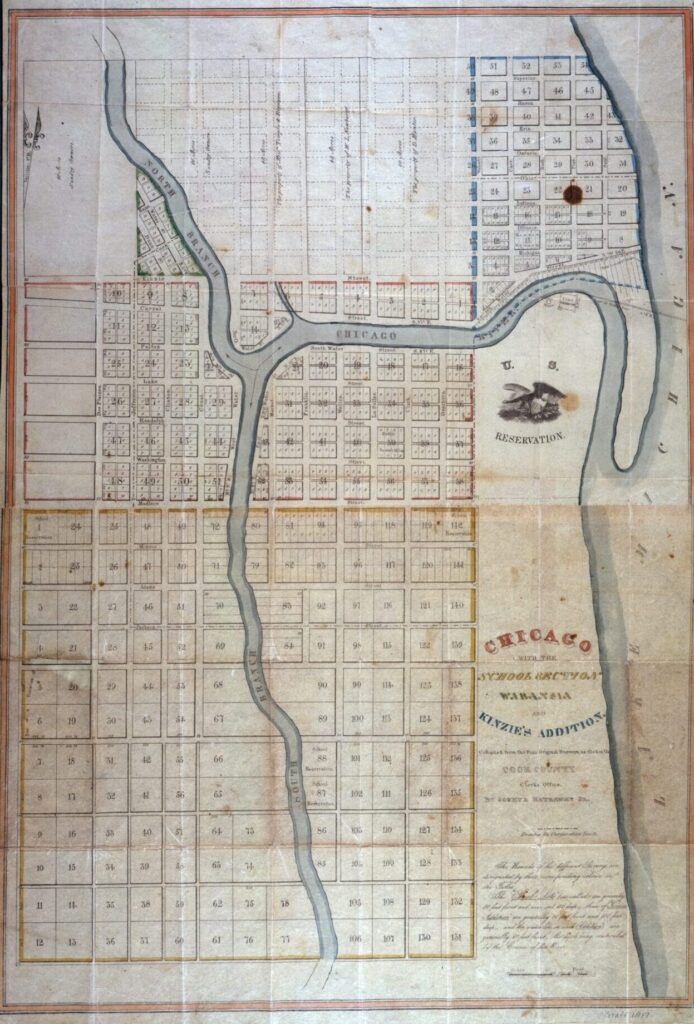

Land Ordinance Map

The Congressional Land Ordinance of 1785 stipulated that land sold in western territories had to be laid out or plated in square parcels to provide an orderly system for purchasing, selling, and taxing property. This led to the “grid system” of streets so common in Chicago and the Midwest. This map was created during a real estate boom in the early 1830s, during which the value of the land rose from $1.60 per acre to $60 per acre in a three-year period.

Questions to Consider:

- How does this map represent the new city of Chicago to make it appealing to potential buyers? Why would this map help in the sale of real estate?

- Given that this map was created to sell real estate, what does the map say about the early origins of the city and the intentions of people who moved here? How does this map relate to Nelson Algren’s vision of the city in Chicago: City on the Make?

- Compare this view of the city to other perspectives you might find in the works of writers like Hecht, Algren, or Brooks. Which perspective provides a more accurate view?

Sensational Literature

Sensational literature was a popular genre of fiction in the nineteenth century often focusing on crime, violence, and the darker side of urban life. This excerpt comes from a short novel in which a retired merchant, Mr. Baldwin, hopes to use his wealth and leisure time to help those in need. A former employee, Harry Harper, leads him through the seedy parts of Chicago to expose him to what life in late nineteenth- century Chicago is really like.

Questions to Consider:

- Harry Harper explains that there are two types of dangerous places in Chicago. What are these two types? Why is one more dangerous than the other?

- How are men and women portrayed in this excerpt? Compare the depiction of women, particularly the old hag in the beginning of the excerpt, to that of the city of Chicago.

- Based on this excerpt, would you say that this text is more interested in instructing the reader, or in exciting his or her curiosity about vice and crime in Chicago? Explain the difference between these two responses.

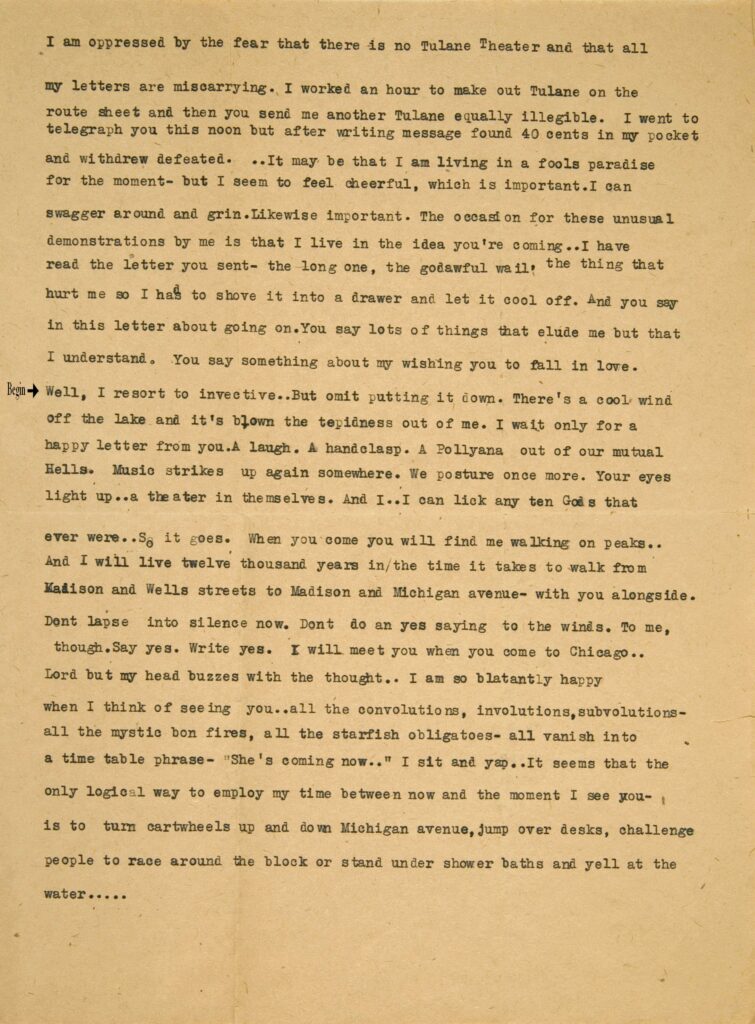

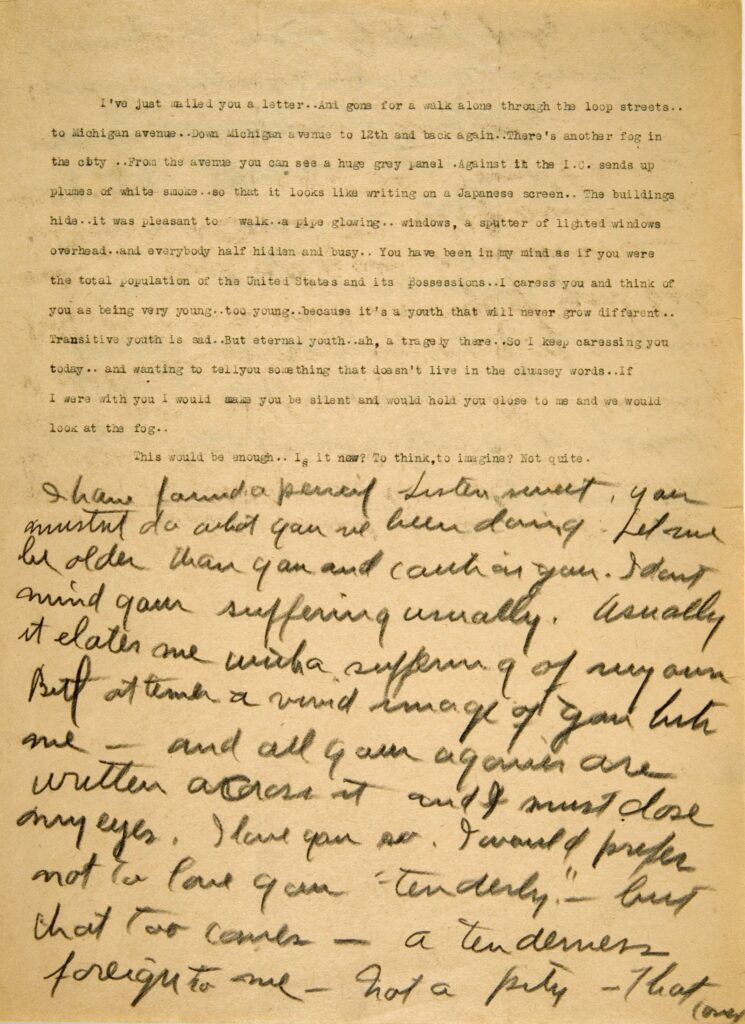

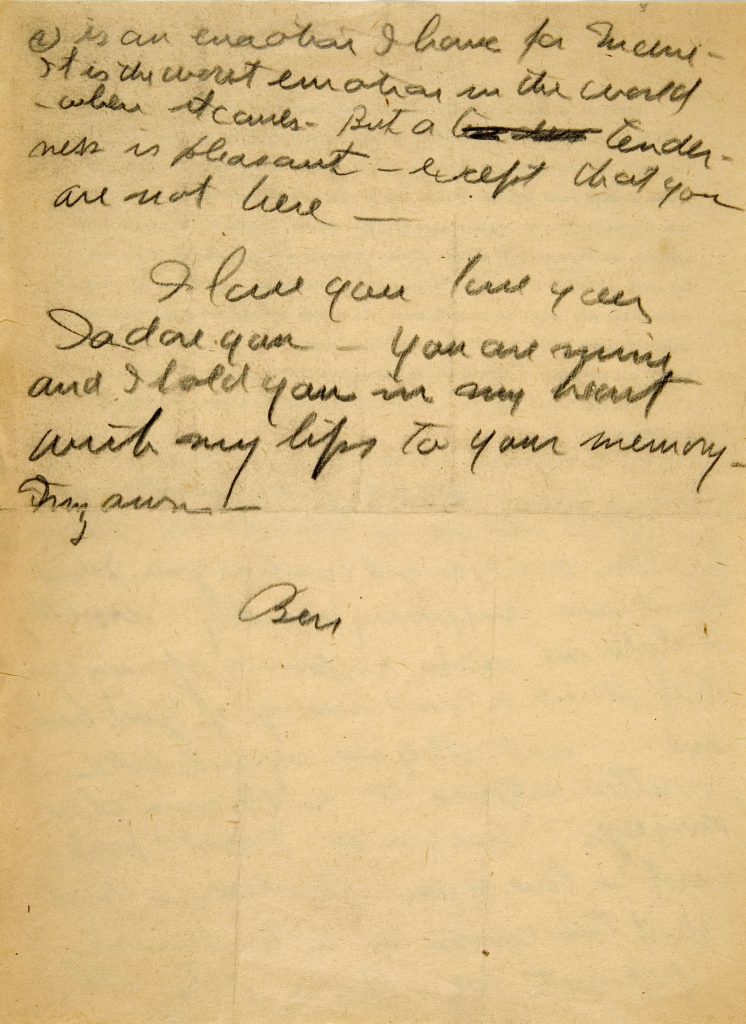

Ben Hecht on Chicago

Ben Hecht divorced his first wife, Marie, in 1925 and married Rose Caylor, a writer living in New York. Hecht and Caylor met several years before the divorce and communicated frequently with letters.

Ben Hecht to Rose Caylor, Letter 1 and Letter 2

Questions to Consider:

- In both letters, how does Hecht describe the environment of Chicago? Which features seem to capture his attention and imagination?

- How would you characterize Hecht’s relationship to the city, particularly in his role as narrator or writer about the city? How does this relationship compare to that of the stories in 1001 Afternoons in Chicago?

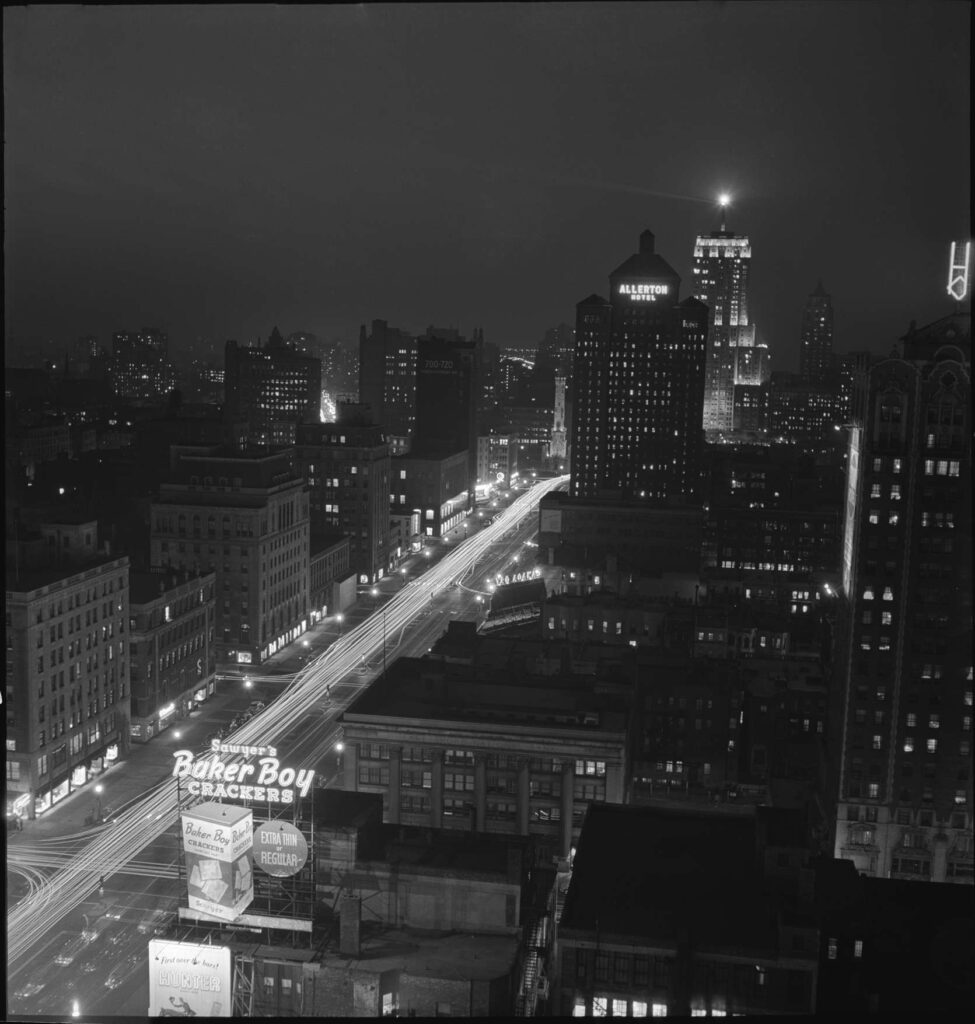

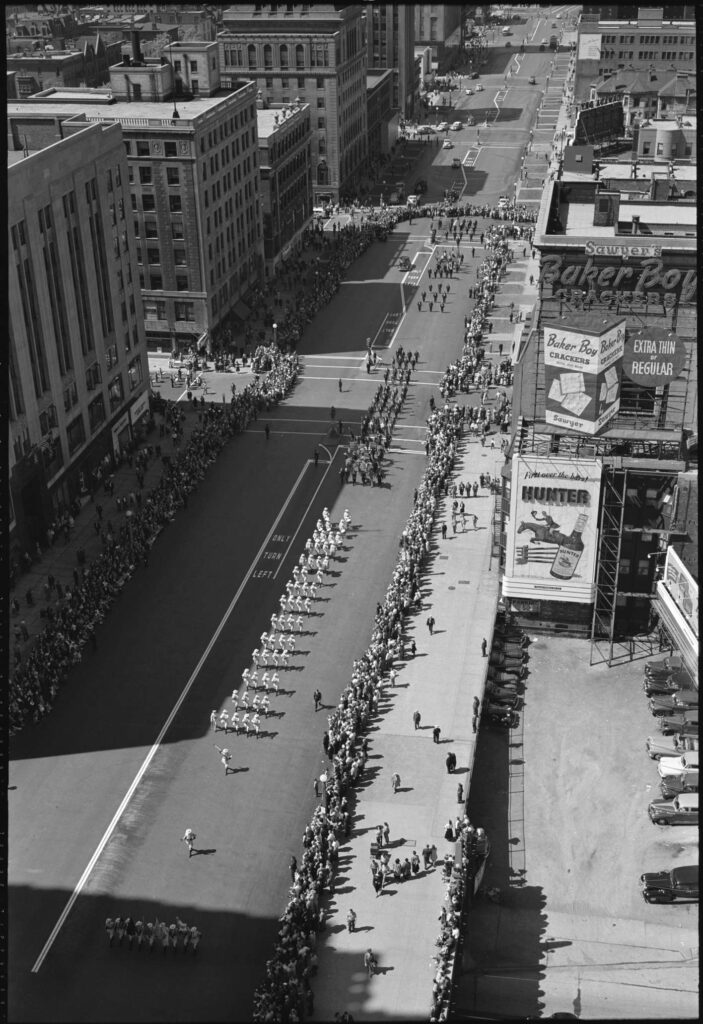

Two Views of Michigan Avenue

The Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad commissioned photographers Esther Bubley and Russell Lee to document the influence of the railroad on the Midwest. Not only did they take pictures of railroad stations, cars, and workers, but they also photographed the cities and towns that the railroad helped to build and supply, including Chicago.

Questions to Consider:

- These pictures both document a specific section of Michigan Avenue from slightly different perspectives and angles. What are some of the features of the city that you notice in these pictures?

- Imagine seeing the two images in isolation. How would you describe the city being pictured in both images? How similar or different do these two portrayals seem from each other?

- Why would Bubley and Lee, who were hired by a railroad company, take these pictures? What do the pictures say about Chicago in the late 1940s?

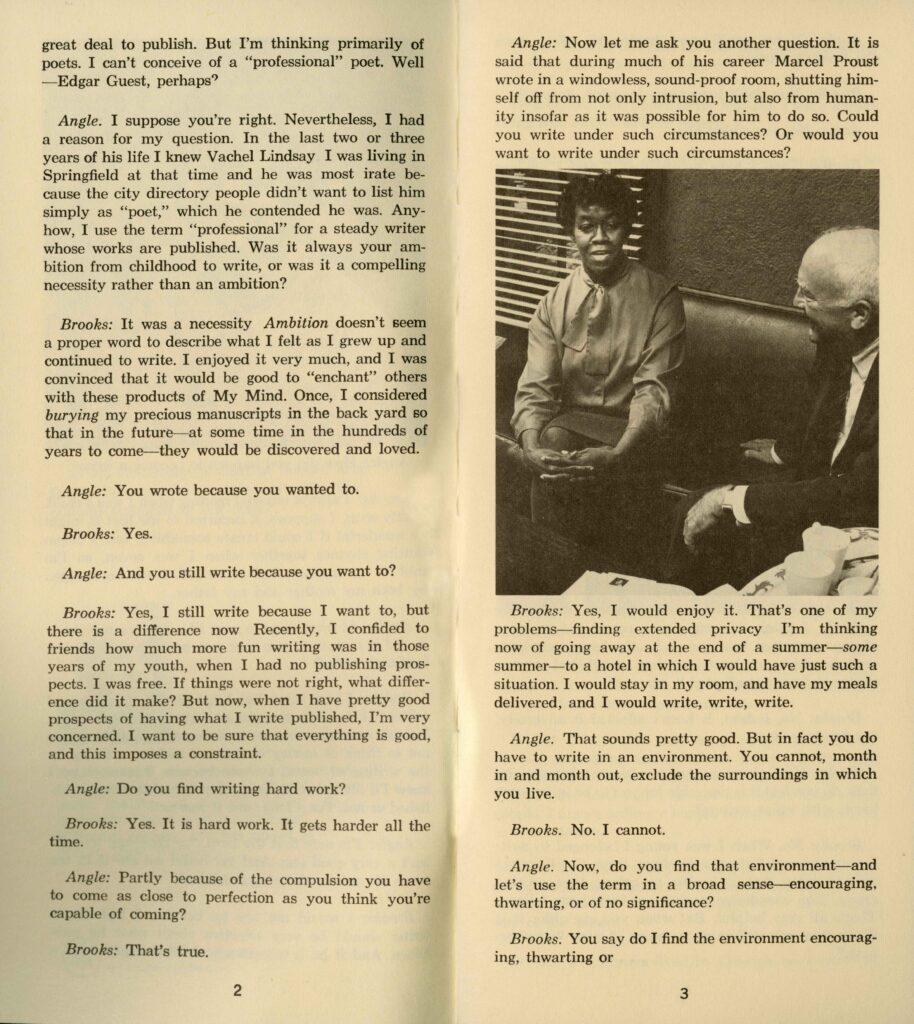

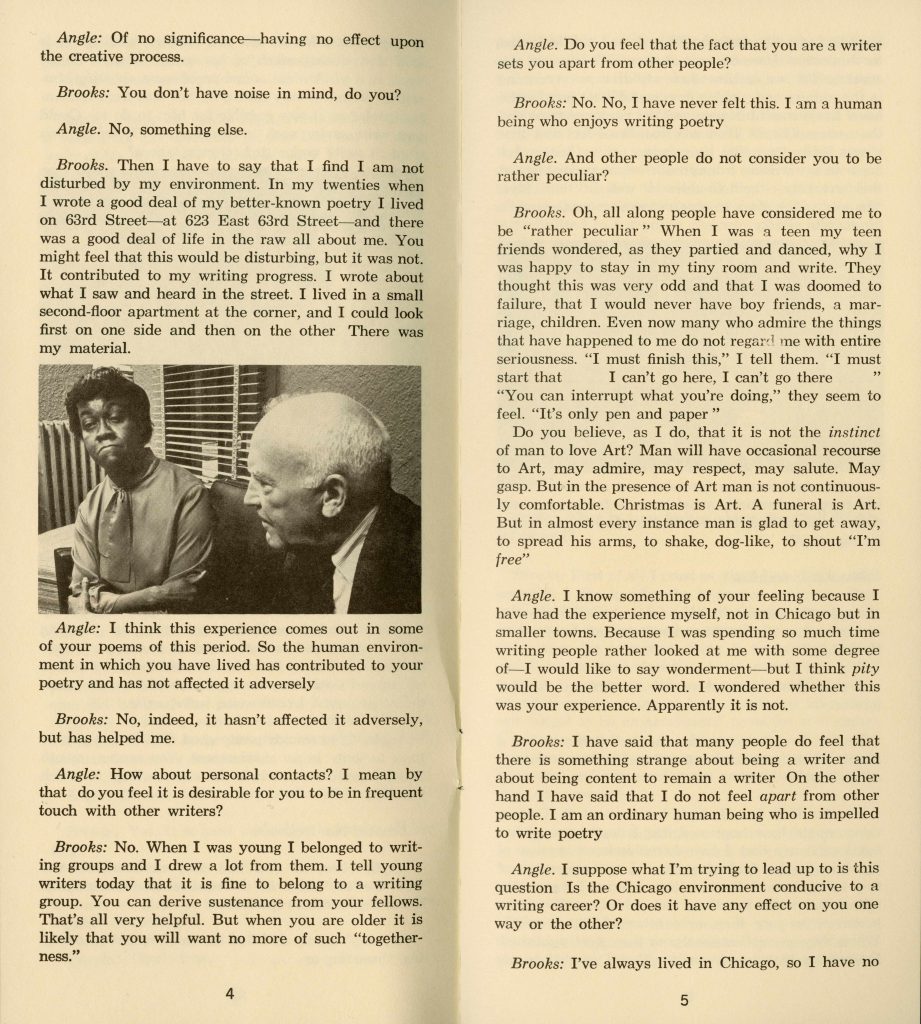

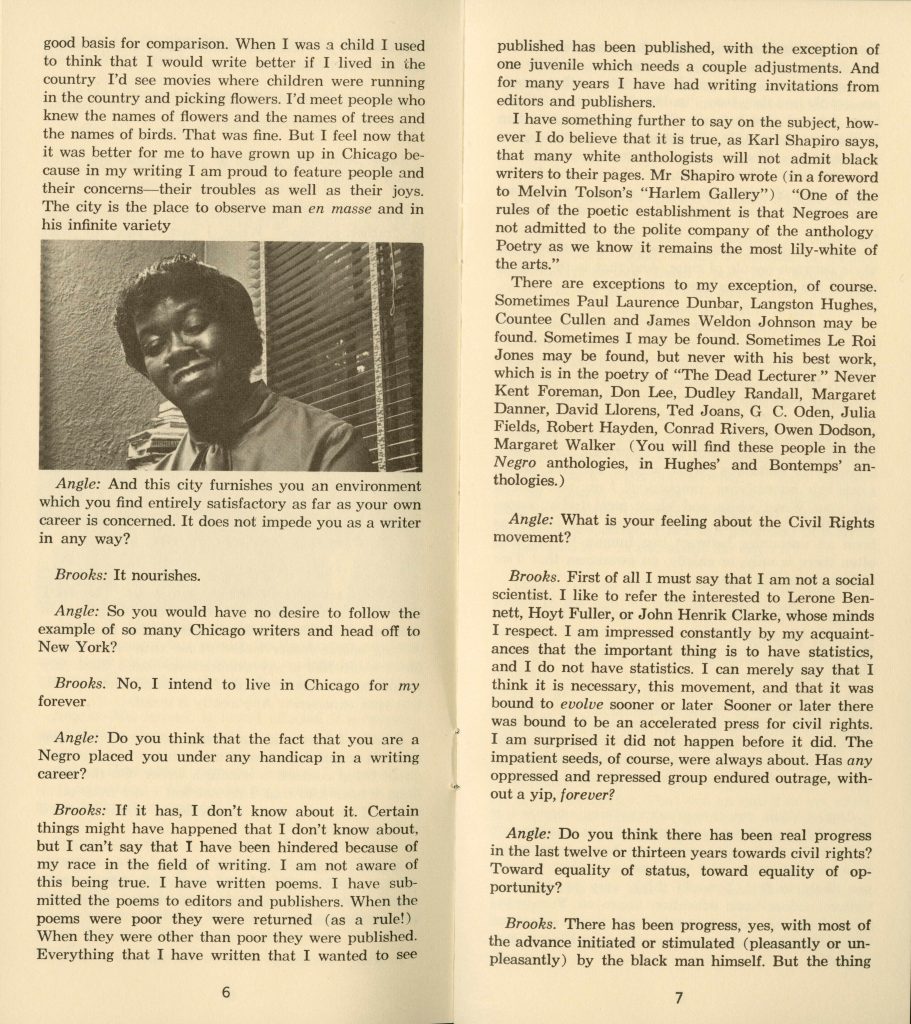

Gwendolyn Brooks on Being a Writer in Chicago

In the 1960s, the Illinois Bell Telephone Company created a series of promotional pamphlets to “present expert testimony on the many resources and opportunities for progress in Illinois.” This particular pamphlet contains an interview with Gwendolyn Brooks conducted by Paul Angle, a well-known Lincoln scholar and former director of the Chicago Historical Society.

Gwendolyn Brooks Interviewed by Paul Angle (1965)

Questions to Consider:

- Explain the tension between “privacy” and “environment,” or noise, in the first part of the interview. How does Brooks talk about these two elements and their affect on her creativity?

- According to Brooks, what has living in Chicago meant for her poetry? What has been beneficial or detrimental about living in Chicago? How does living in the city compare to her idea of living in the country?

- This interview was conducted for a series promoting Illinois. How would you describe Brooks’ characterization of Chicago? Does she “sell” the idea of Chicago? Why do you think she states at the end that she has no desire to leave Chicago?

Early Depictions of Chicago

Ben Hecht to Rose Caylor

Views of Michigan Avenue (1948)

Gwendolyn Brooks Interviewed by Paul Angle (1965)

Further Reading

Mike Royoko. Boss: Richard J. Daley of Chicago, 1971.

Carl Sandburg. “Chicago,” “Child of the Romans,” and “Happiness.” In Chicago Poems, 1992.

Gwendolyn Brooks. “The Vacant Lot,” “Kitchenette Building,” “of De Witt Williams on his way to Lincoln Cemetery.” In A Street in Bronzeville, 1945.

Tony Fitzpatrick. Bum Town, 2001.

Ben Hecht. A Thousand and One Afternoons in Chicago, 2009.

Nelson Algren. Chicago: City on the Make, 2001.