Chicago in 1871

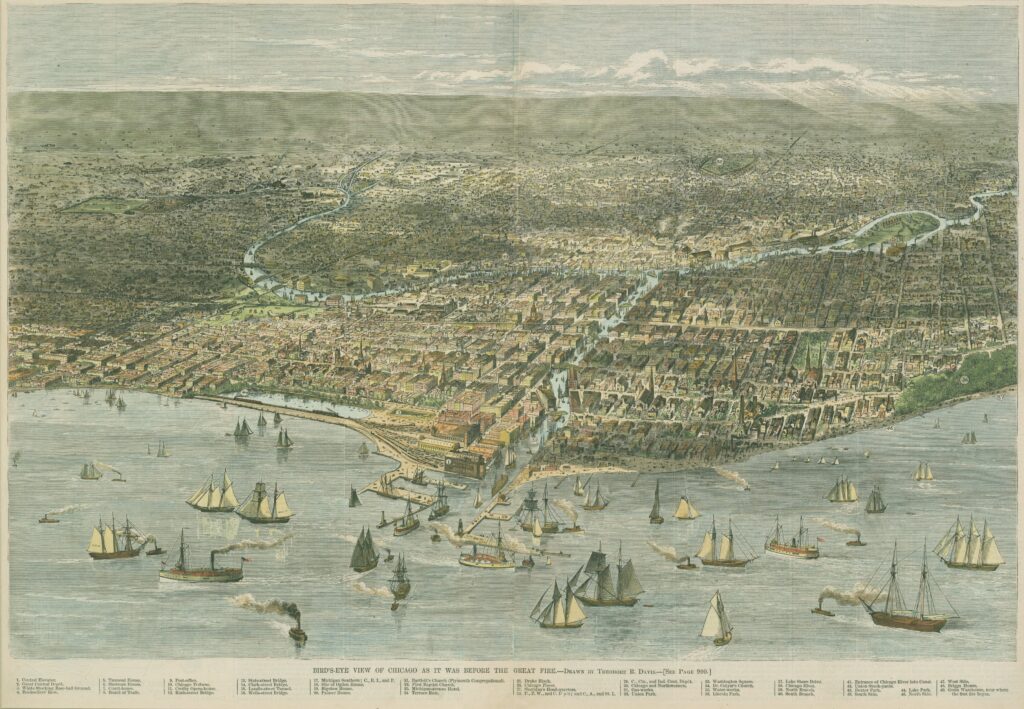

Chicago had grown faster than anyone could have imagined, from a population of 4,170 when it was incorporated as a city in 1837, to a population of nearly 299,000 in 1870. By then, it ranked as the fifth largest city in the United States. Geographically, the city covered the area roughly bordered by Fullerton Avenue on the north, the lake to the east, Pershing Road to the south, and Pulaski Avenue on the west.

No longer a backwater town, Chicago was transforming into the country’s transportation hub and an important commercial and economic center. The city boasted of its art, culture, and educational institutions as a competitor with the more established cities in the east (New York, Boston). This fast and furious growth, along with Chicago’s swampy location, resulted in many wooden structures and raised wooden sidewalks to keep pedestrians out of the mud. Consequently, fire was a continuous threat.

On October 7, a week of repeated small fires culminated in what would become known as the Saturday Night Fire. It began late in the evening and leveled twenty buildings on the city’s near West Side. Damage was estimated at a million dollars. It was not until the following afternoon that the blaze was extinguished, leaving firemen exhausted and their equipment in ill repair. The city was completely unprepared for the Great Fire, which began the next night. The destruction would, however, create a blank canvas in Chicago, and Chicago history would henceforth be divided into “before the fire” and “after the fire.”

Please consider the following questions as you review the documents:

- What were the actual losses from the Great Fire, in human terms and in physical terms (buildings, land damage, etc.)?

- How did the city recover?

- What were some of the long-term impacts of the fire on the growth of the city?

The Fire: The Extent of the Damage

Although the exact cause is still debated, the Great Chicago Fire likely began near the O’Leary family barn on the west side of the city at about 9:00 pm on Sunday, October 8, 1871. The fire continued to tear through the city, destroying everything in its path, until late Monday night, when rain finally extinguished the last of the flames. For nearly 126 years, Mrs. Catherine O’Leary and her cow were believed to have caused the Great Fire. An alternate theory placing the blame on an eyewitness, Daniel “Peg Leg” Sullivan had been proposed by several historians. But the myth of the fire, the cow, and Chicago has proven hard to extinguish. Mrs. O’Leary and her cow provided a clear cause for a complex and catastrophic event. Anti-Catholic, anti-female, and anti-immigrant sentiments also helped fuel the legend. It wasn’t until October 28, 1997, that the Chicago City Council passed a resolution put forward by the Committee of Fire and Police officially exonerating the cow and the O’Leary family of any blame for starting the Fire.

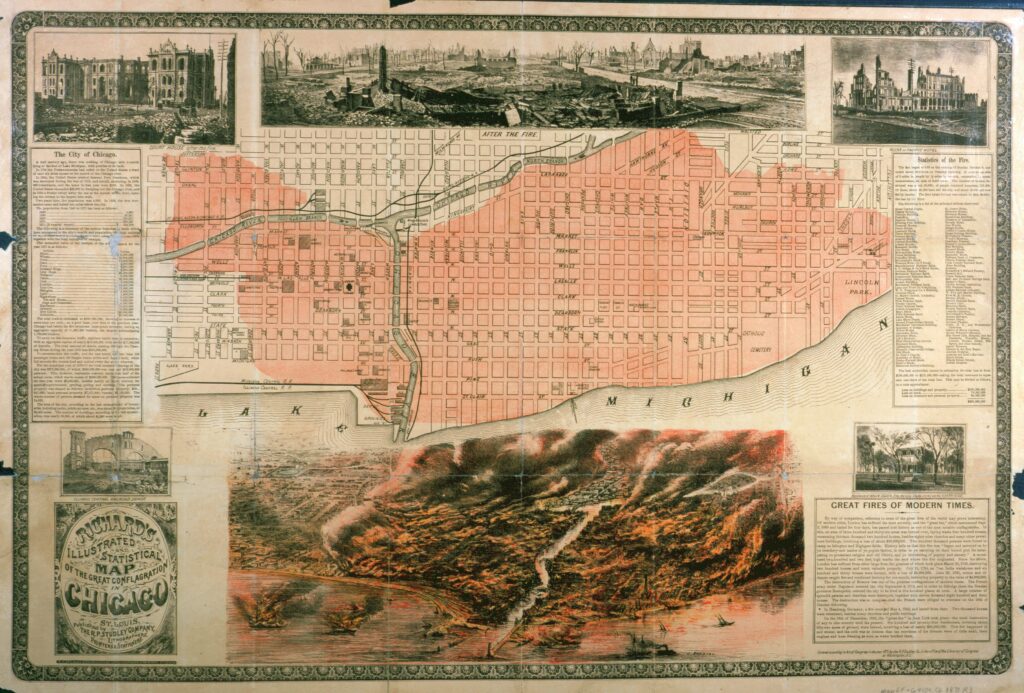

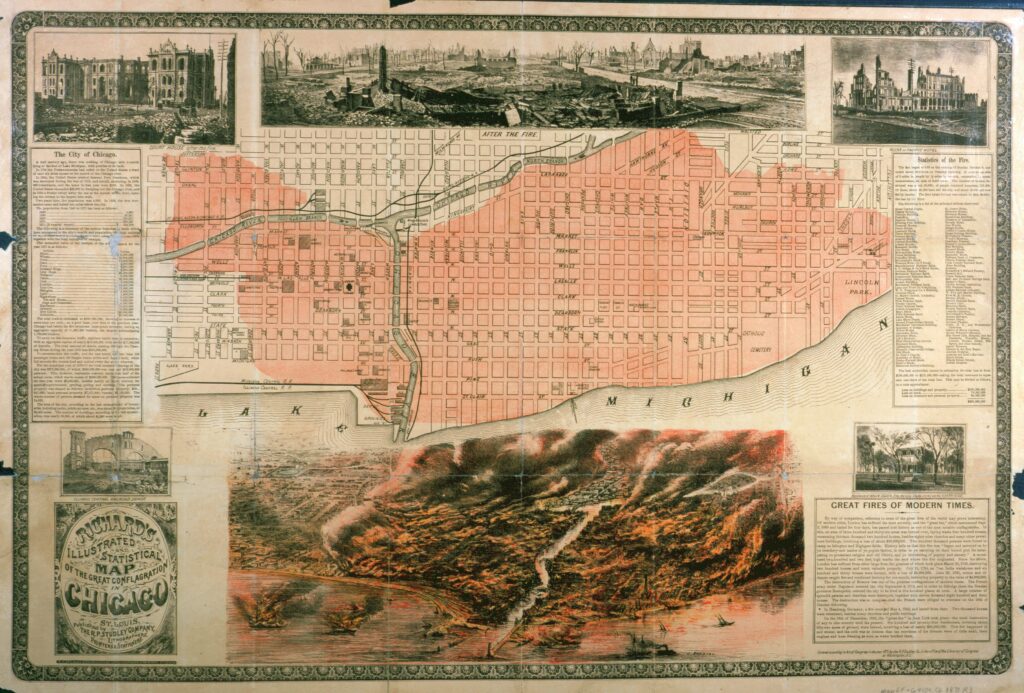

The damage was extensive, however the fire did not destroy the entire city of Chicago. The destruction was about four miles long and an average of three-quarters of a mile wide (more than 2,000 acres in total). Over 120 miles of sidewalks and over 2,000 lampposts burned. Nearly 18,000 buildings were destroyed. Property damage was estimated at over 200 million dollars, at the time about one-third of the valuation of the entire city.

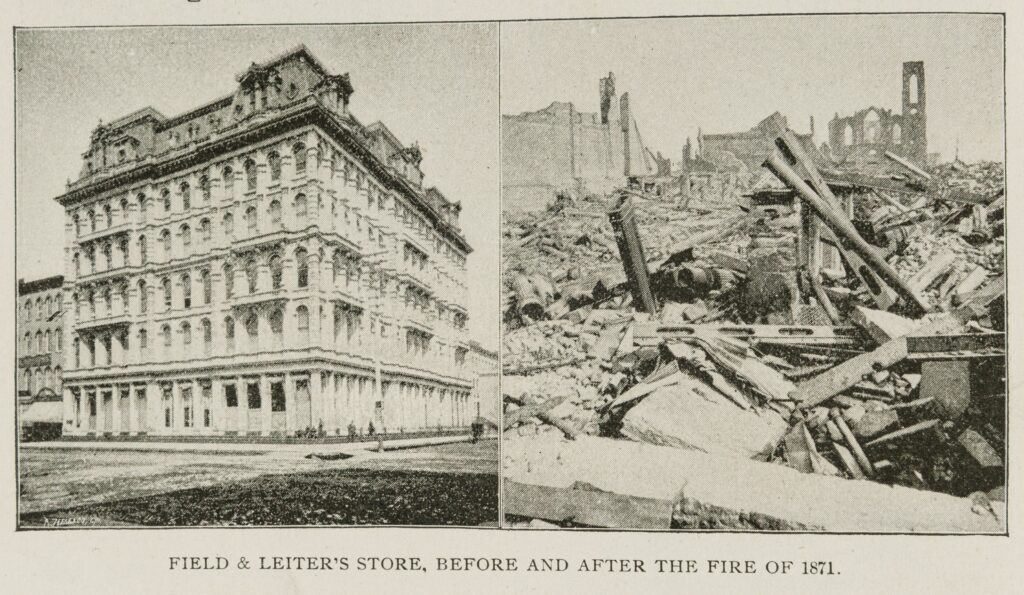

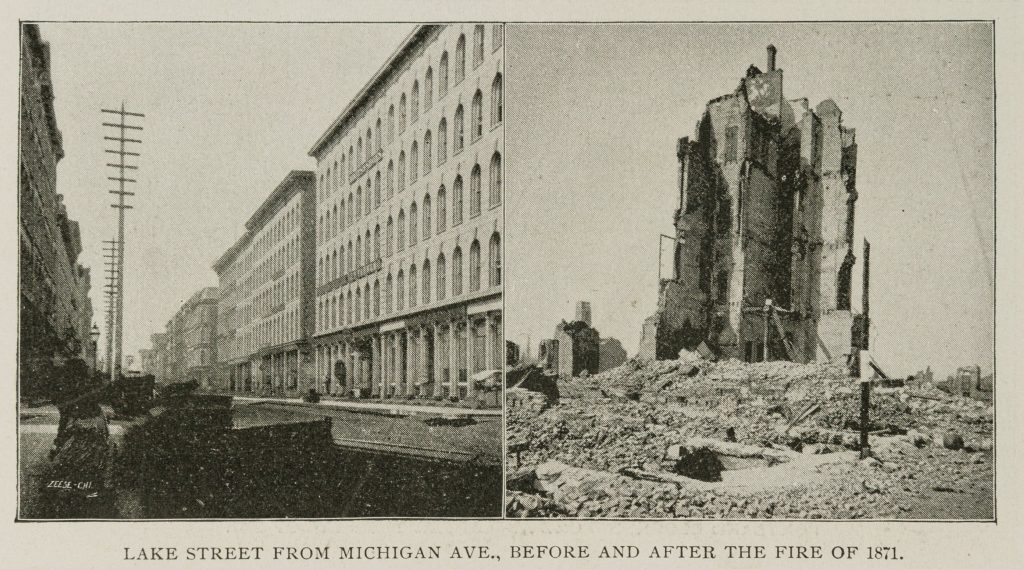

Government buildings, law offices, hotels, stores, banks, churches – significant and expensive buildings in the central business area, south of the river— were leveled. Although the fire ignited on the West Side, that section of the city sustained less damage. The most extensive devastation was on the North Side where about 13,000 buildings, primarily residences and local businesses, burned to the ground.

The bridges linking the South Side to the North and the West Sides were almost all destroyed. The water tower and its pumping station were the only public buildings to survive. Because of the severe damage, however, water supply to the city was cut off for eight days. The South Side gas works exploded. Miraculously, the railroads were relatively unscathed, allowing for critical transportation of goods and people during the recovery efforts.

The fire took a human toll as well. Hundreds of thousands of people had fled the consuming flames in chaos. Some escaped with bundles of clothing or valuables. Many were unable to save anything. Over 100,000 people lost their homes. It is estimated that 300 people died in the fire, and most of the victims were burned beyond recognition. Due to the severity of the fire and the fact that an unknown number of people left the city never to return, a complete list of the dead was never compiled.

The severe destruction of the government and business area downtown meant the loss of city and county records. Vital records, such as birth, marriage and death records, court records, wills, probate, and property records were among the documents that fueled the fire. Even documents that were in locked safes were reduced to ashes.

The ground remained so hot that it was several days before the full extent of the devastation would be realized.

Questions:

- What are some lasting consequences to losing so many critical documents in the fire?

- Who would the Richard’s Illustrated and Statistical Map of the Great Conflagration in Chicago have been created for and why?

- Emma Lander Hambleton, who wrote the letter above, and her family were upper-class. How do you think their experience of the fire and its aftermath compared to those of the immigrant population?

- How does the devastation compare to images of more recent catastrophic events?

The Immediate Aftermath

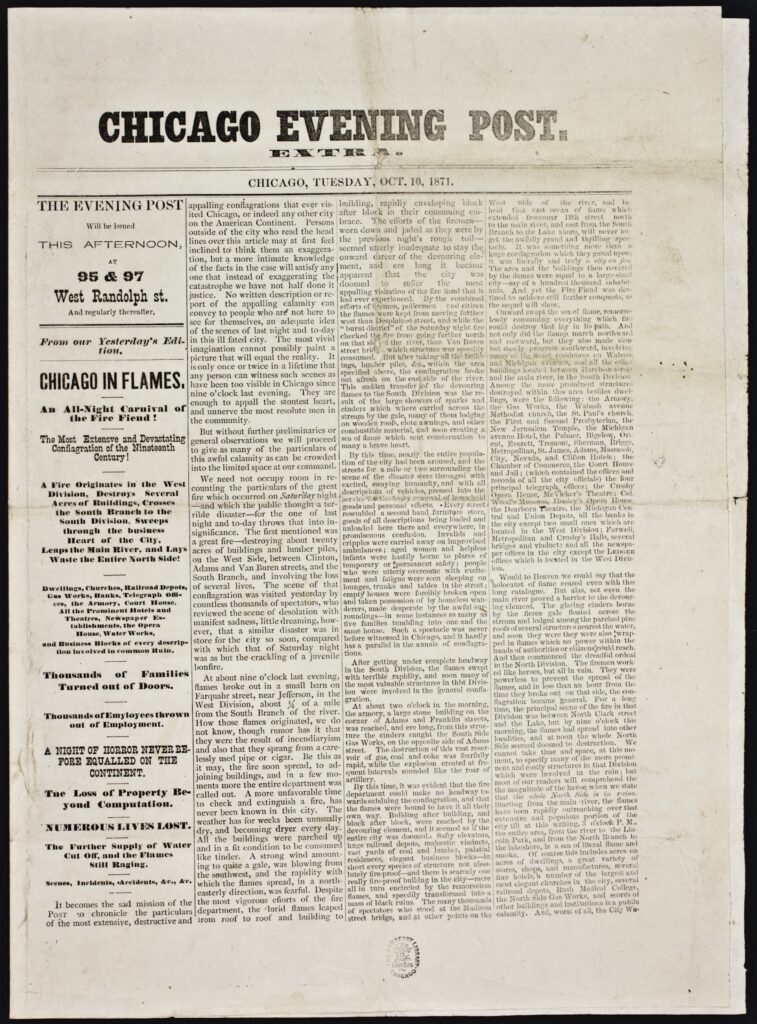

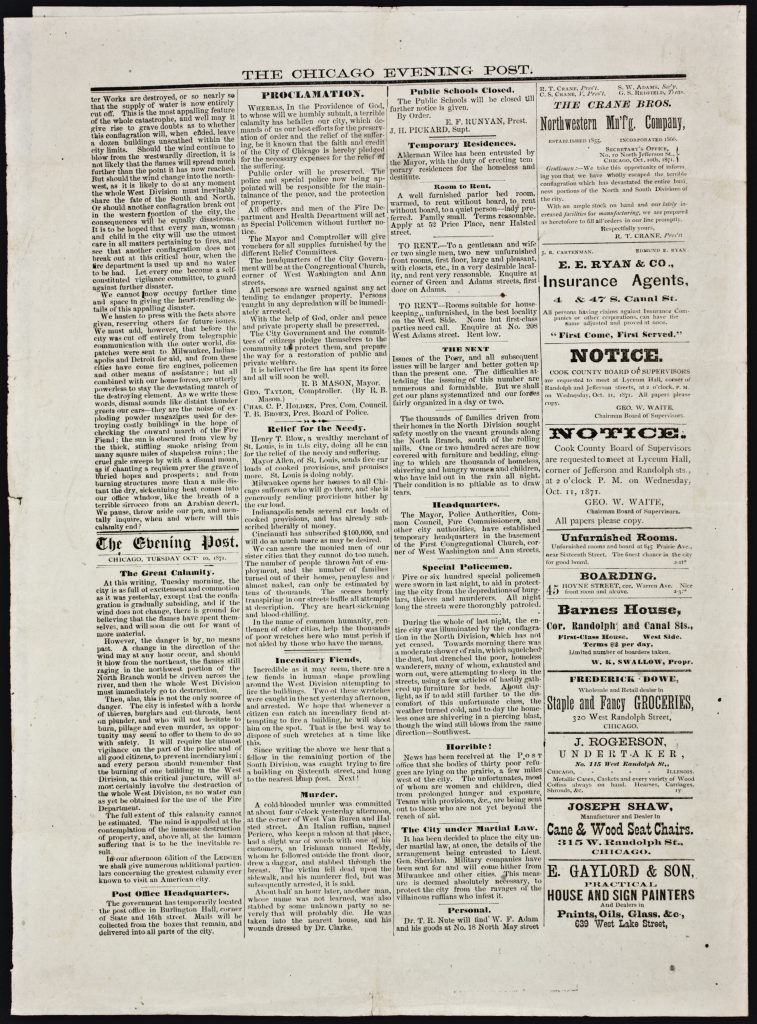

Before the fire was fully extinguished, Chicago residents started to address the damage. Two newspapers, the Evening Journal and the Chicago Post, managed to publish special editions on Monday, October 9. They described the devastation of the city as well as the panic and horror endured by its citizens. Telegrams with the news went to St. Louis, Cleveland, Milwaukee, and other nearby cities requesting assistance. The City Council called a meeting and Mayor Roswell B. Mason issued a proclamation that all stoves in the city should be extinguished to reduce further risk of fire.

Selection: Chicago Evening Post, “Chicago in Flames” (October 10, 1871)

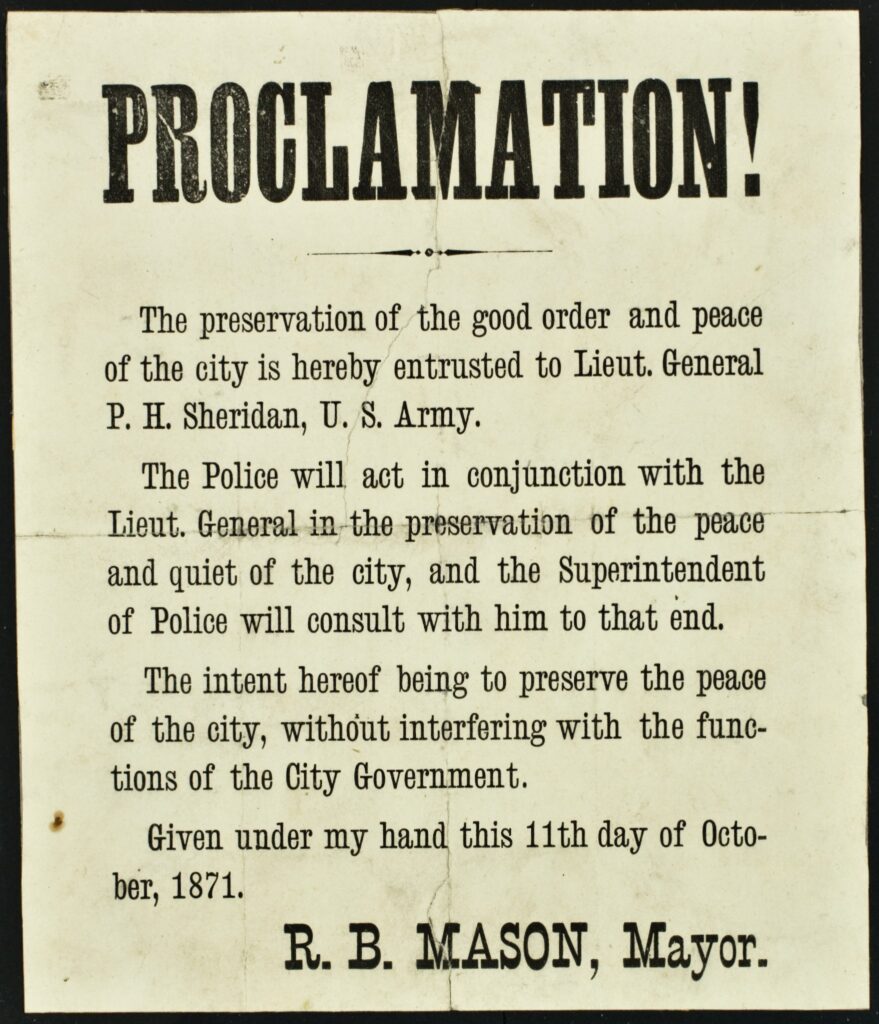

As Chicagoans fled for their lives, reports of looting and robbery spread as fast as the blaze. Although most of these charges were greatly exaggerated, the mayor issued a proclamation placing Chicago under martial law. Civil War hero Lieutenant General Philip Henry Sheridan was in charge. This military oversight lasted for two weeks. It brought comfort to a nervous segment of the population who feared potential crime and violence. They greeted the arrival of “Sheridan’s boys” with relief. Others, however, felt that martial law was unnecessary as Chicago remained peaceful and the anticipated crime wave never occurred.

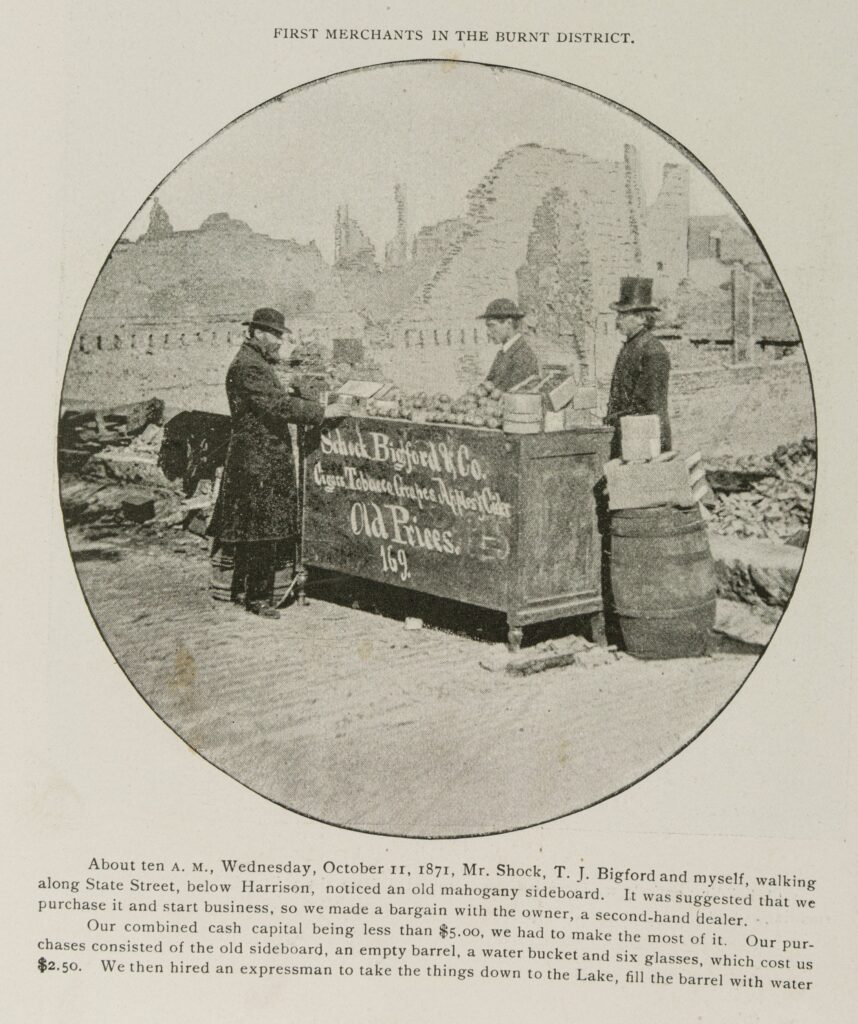

Regardless of who was in authority and despite the devastation, Chicagoans immediately began to provide humanitarian relief and rebuild the city. Vendors sold what little they had. The picture on the right shows T. J. Bigford, Mr. Stock, and H. W. Kennecott, who were quick to combine resources and made a profit of $25 the first afternoon. Residents carried ashes, broken bricks, and rubble to the lake. Workers pulled down ruined walls. Work to repair infrastructure, especially the water tower and pumping station, began at once. Providing water to all the city residents for drinking, cooking, sanitation, and for extinguishing future blazes was the highest priority.

Questions:

- What were the risks facing Chicago in the immediate aftermath of the fire?

- What steps did the city take to lessen these risks?

- Based on the description of the city in the Chicago Evening Post, was the imposition of martial law justified?

Humanitarian Aid

Following the mass destruction of so many homes and businesses, providing basic necessities to the refugees was of the upmost importance. The type of social services that react to disasters today were not yet in existence to manage this process. Food, shelter, and clothing were the immediate issues. Many residents also needed jobs.

On October 17, Mayor Mason issued another Proclamation to coordinate the volunteer groups and manage donations from around the world. He directed the Chicago Relief and Aid Society to coordinate all relief efforts.

Prominent Chicagoans had founded the Relief and Aid Society in 1851. The First Special Report of the Chicago Relief and Aid Society details how the Society organized relief efforts. Members of the Society formed committees on shelter, employment, transportation (people and supplies), reception, and correspondence (to deal with visitors and letters), distribution (food, clothing, and fuel), and health and sanitary issues.

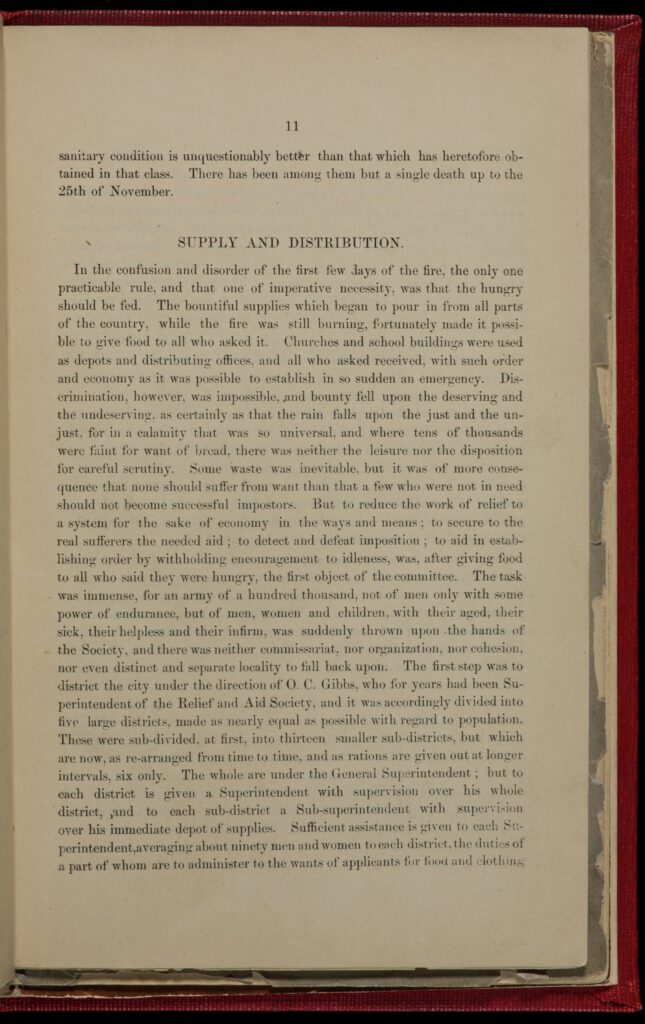

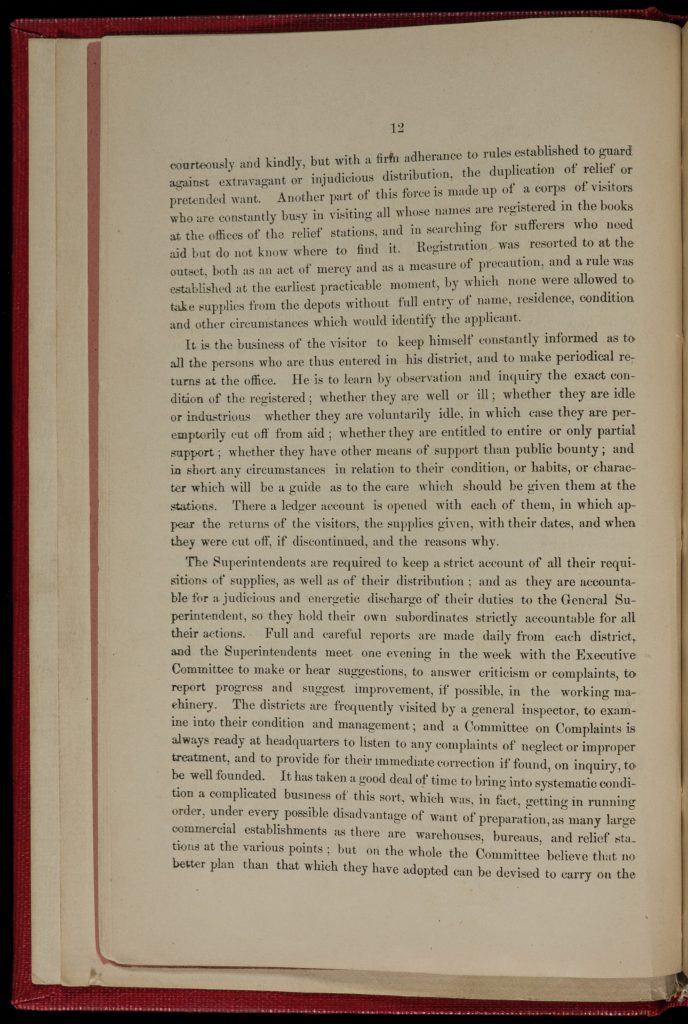

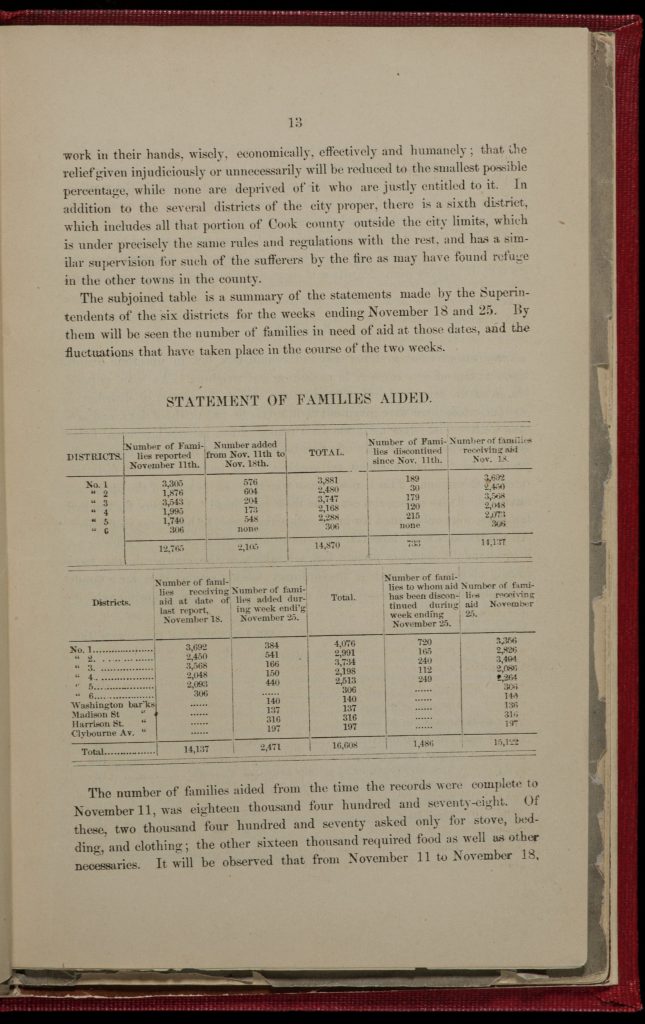

Selection: Chicago Relief and Aid Society, The First Special Report of the Chicago Relief and Aid Society, 11-13 (1871)

Although churches and schools acted as temporary shelters, winter was approaching and the city needed a long-term solution. The Society hoped to provide small but comfortable houses to all those who had owned or leased the lots on which they lived before the Fire. These families received prepared materials and either constructed the building themselves or hired builders. The houses came in two sizes: 20 x 16 feet for families of more than three; and 12 x 16 feet for smaller families. Also included were a cooking stove, utensils, chairs, a table, bedstead, bedding, and crockery. The total cost for house and furnishings was $125. In addition to these individual homes, four barracks were built to lodge an additional one thousand families. There was no systematic process for distributing food during or immediately after the Fire. Relief groups quickly streamlined this process, so that an organized system provided fixed rations on a regular basis. Food and fuel for an average family were provided at a cost to the relief effort of about $3.10 per week.

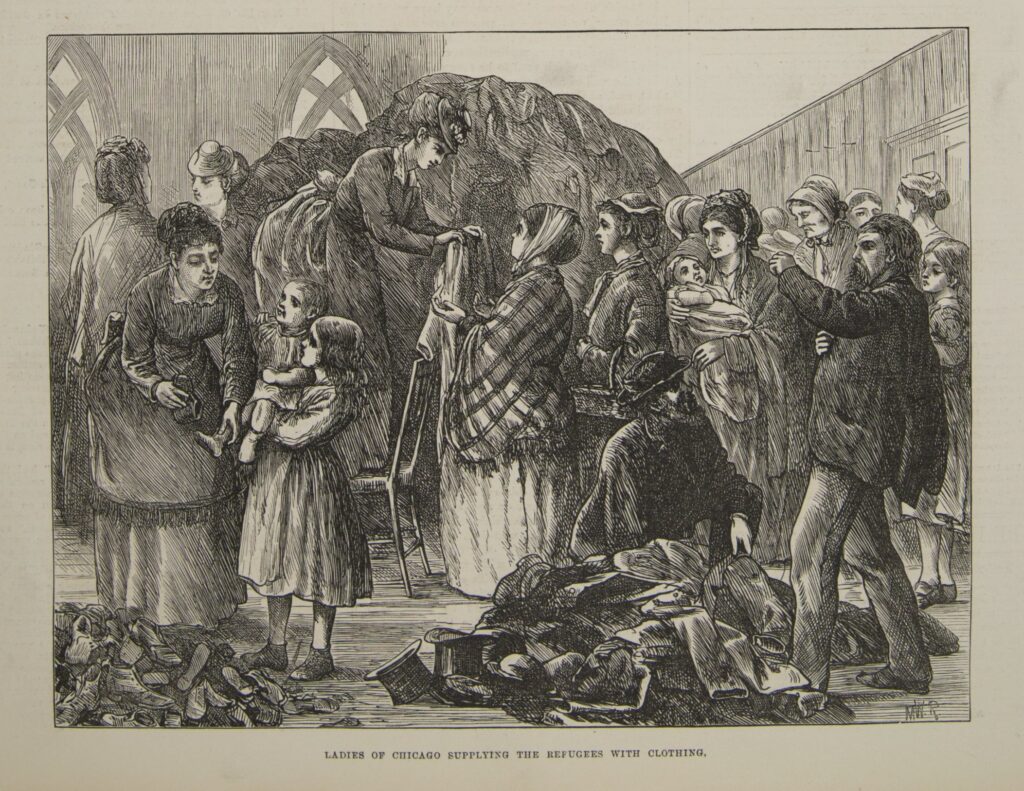

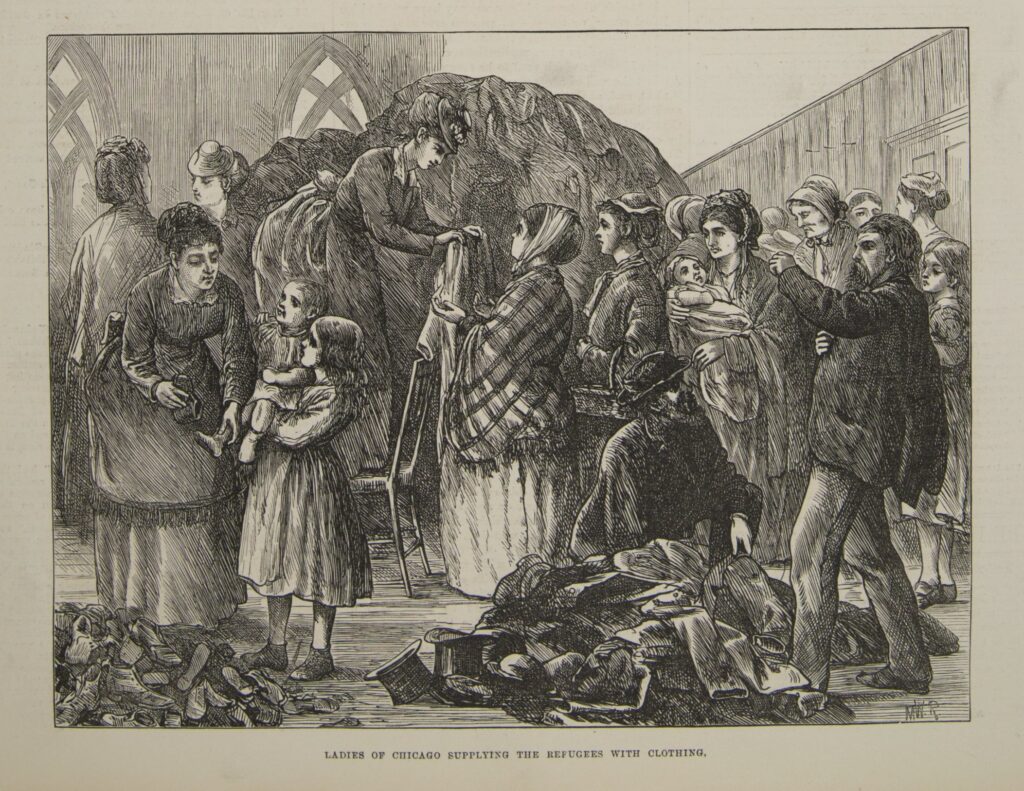

Clothing was another immediate concern. While second-hand summer items were readily available, here again the onset of cold weather was a problem. As ready-made clothing was scarce, ladies’ associations swung into action sewing and providing piece goods so that the victims could make their own clothes.

The city charged the newly created Board of Health with protecting the health of the sick and homeless. The Board established dispensaries at convenient sites around the city where physicians, many of whom had lost everything themselves, volunteered their services in the filth and disorder. Despite such attempts to battle the bad sanitation, over two thousand people contracted smallpox the following year.

The Relief and Aid Society did an extraordinary job in extreme circumstances and was much praised for all it accomplished. There was also room for well-justified criticism, particularly that the elitist views of the prominent men in control of the Society may have contributed to an unfair distribution of food and goods based on the recipients’ social and economic statuses.

Questions:

- How was the distribution of supplies organized? Was the method of distribution equitable?

- What were some of the challenges faced by the Relief and Aid Society?

Rebuilding Chicago

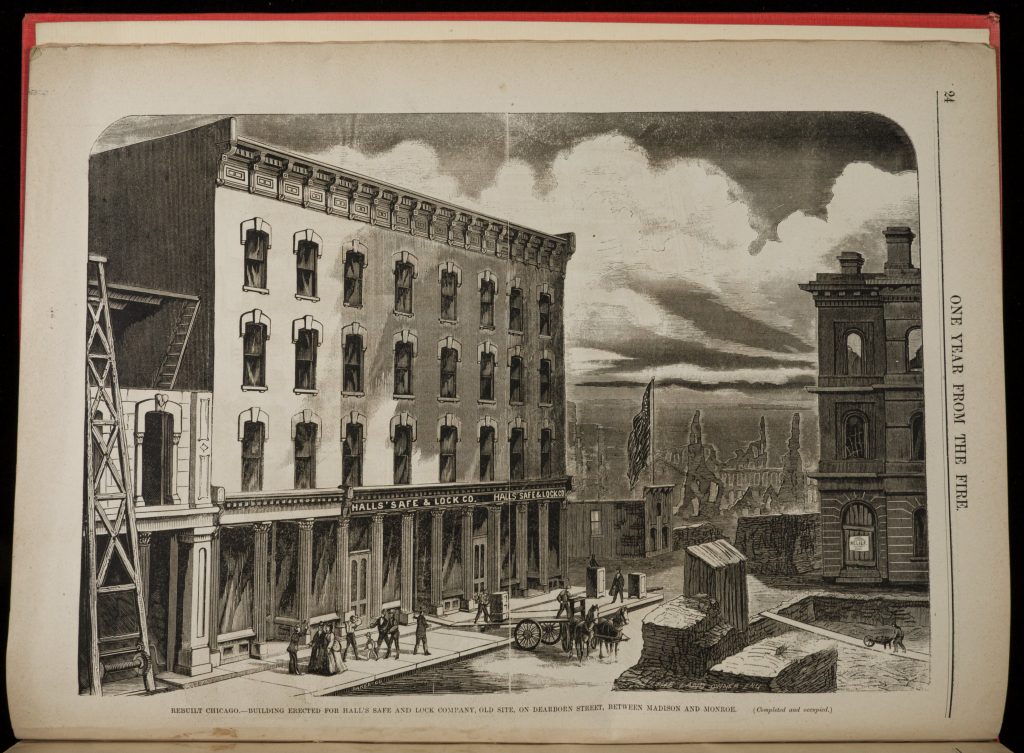

By the afternoon of Tuesday, October 10, the first load of new lumber had entered the burnt South Side. The Union Stockyards meatpacking district and many lumberyards, railroad depots, wharfs, mills, and grain elevators were among the businesses that were located outside of the burn zone. These businesses became critical to the city’s rapid re-building effort.

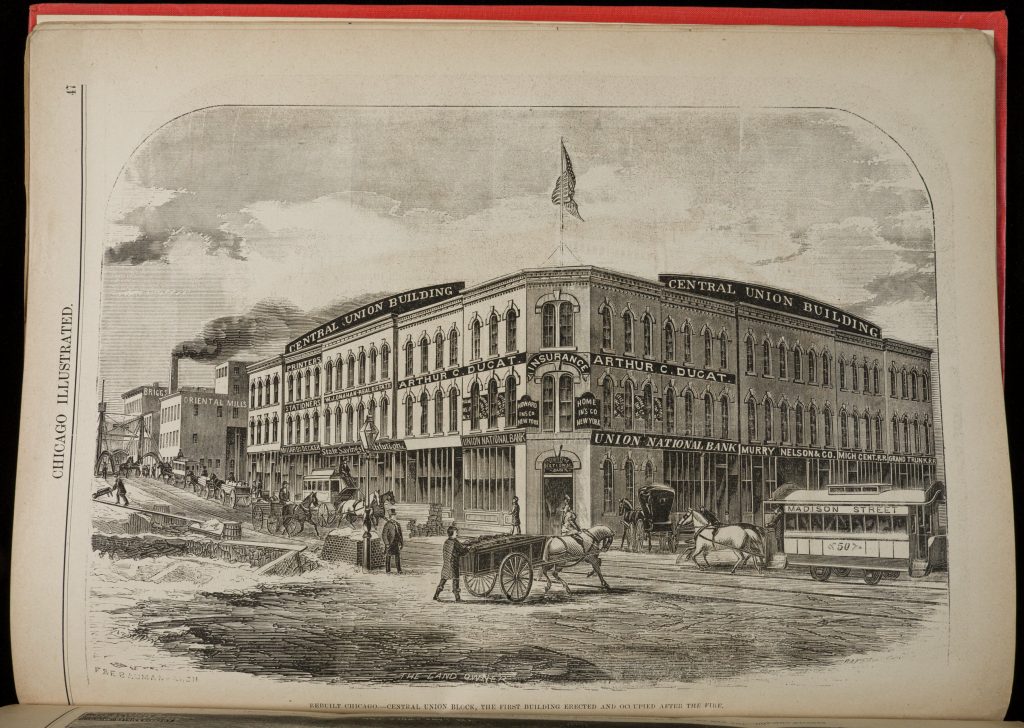

Buildings went up at a furious pace. The years immediately following the fire became known as “Derrick Time” because the burnt area seemed to always be empty ground or covered with stacks of building materials. Smaller wooden structures popped up immediately. The first brick structure to be completed was Central Union Block 1, located on the northwest corner of North Wacker Drive and West Madison Street. It was open for occupancy by December 16, 1871.

Joseph Medill won the Chicago mayoral election on November 7, 1871 by a landslide, running on the “Union-Fireproof” ticket. In his inaugural message to City Council he stated, “If we rebuild the city with this dangerous material [pine], we have a moral certainty, at no distant day, of a recurrence of the catastrophe…the outside walls of every building hereafter erected within the limits of Chicago should be composed of materials as incombustible as brick, stone, iron, concrete or slate” (Andreas, History of Cook County, 58.).

The forerunner of building codes, these fire limits were the boundaries within which buildings had to be built of brick or stone instead of wood to reduce the risk of fire. The location of the fire limit was a source of contention following the Great Fire. While fire limits promised safety from another inferno and were supported by the wealthy and large businesses, immigrants, particularly those on the devastated North and West Sides, depended on cheap wooden construction to build their homes. Even the housing erected by the Relief and Aid Society would not meet strict fire codes. The debate raged. A full-city extension of the fire limits was defeated in 1872 but won approval after the city experienced another major fire in 1874.

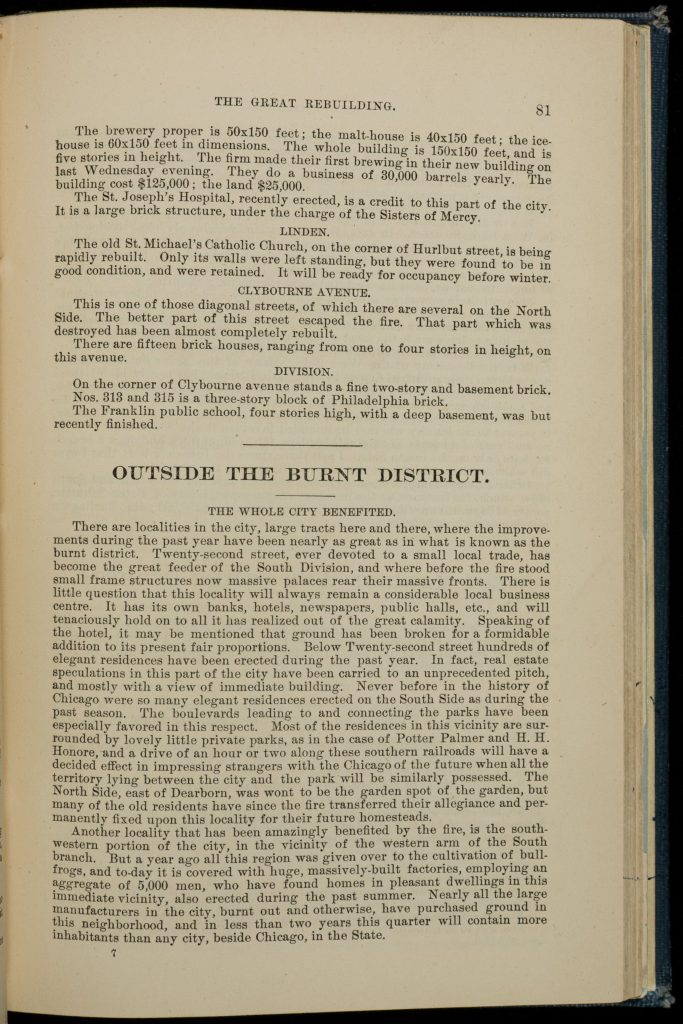

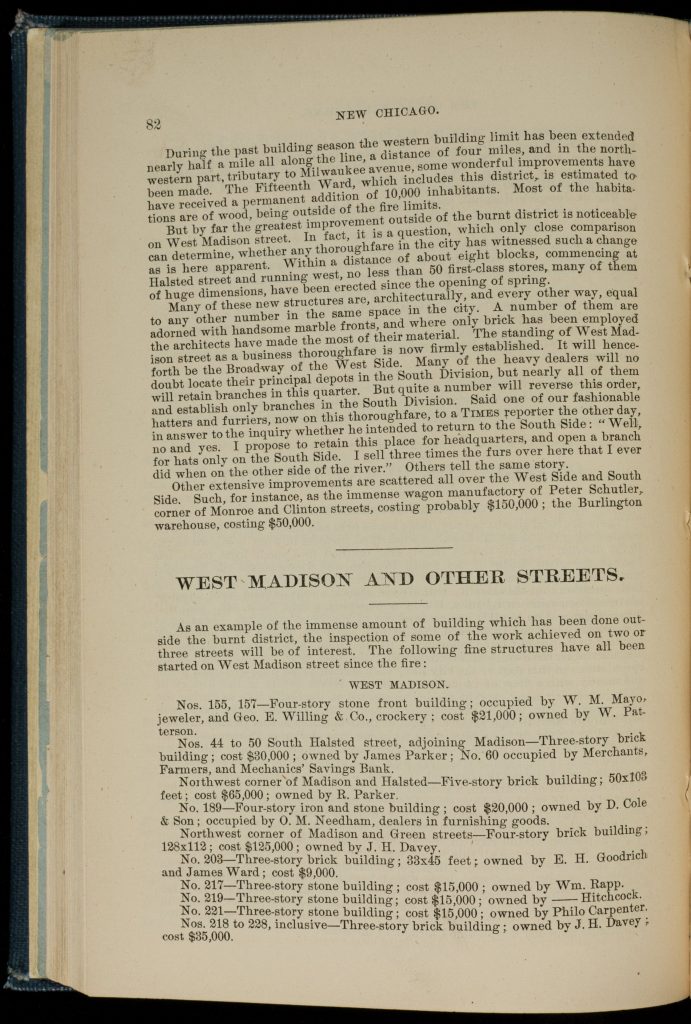

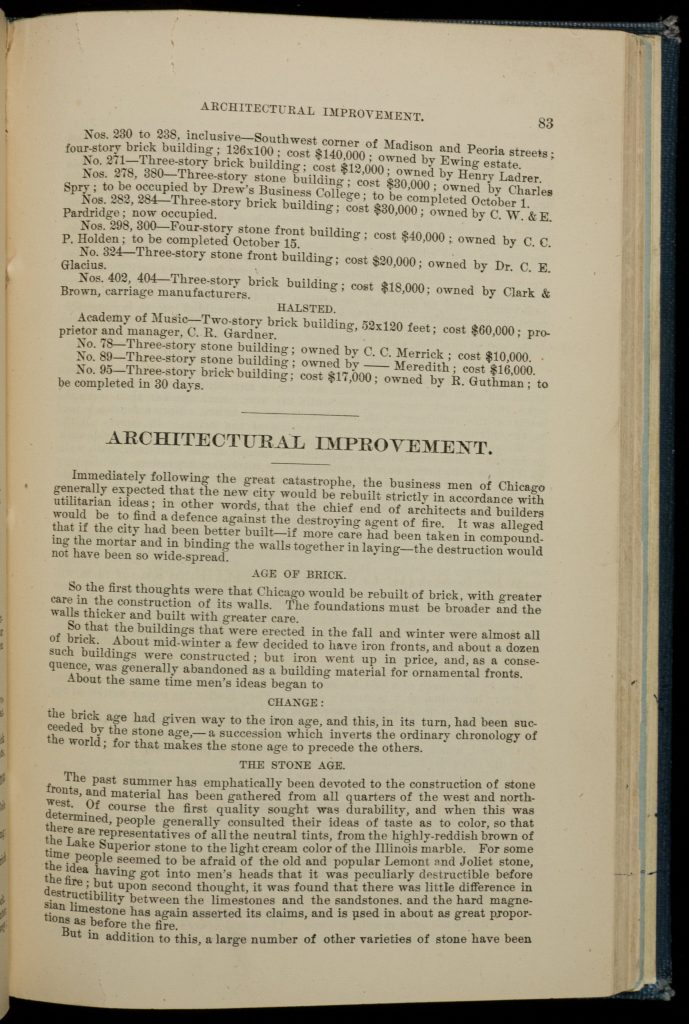

Selection: Chicago Sun Times, New Chicago: A Full Review of the Work of Reconstruction, 81-85 (1872)

During this time, terra-cotta, brick, limestone, and marble became popular and effective building materials. By the mid-1880s, the use of terra cotta tiling made Chicago a national leader in fire prevention. Chicago architects continued to find creative building solutions. For instance, William Le Baron Jenny designed the world’s first steel-frame skyscraper in 1885. Eventually, innovations of the “Chicago School” of architecture—like large plate-glass windows and steel-frame buildings with masonry exteriors—prompted a revolution in architectural design world-wide.

Neither the Great Fire of 1871 nor a national depression, from 1873 to 1878, impeded the growth of Chicago. The 1880 the census recorded 503,000 inhabitants – almost 204,000 more than in 1870. By 1890, there were over a million residents in Chicago and by 1893 Chicago was ready to take its place on the world stage by hosting the World’s Columbian Exposition.

Questions:

- What impact did the fire have on the sections of the city which did not burn?

- What are some of the building techniques and design innovations which developed following the fire?

- How does the recovery from the Great Fire compare to the recovery from current disasters?

About the Author

Ginger Frere, MLIS, MBA, is a professional researcher providing research services to authors, historians, film makers and individuals interested in genealogy. In addition, she is a Newberry Scholar-in-Residence, frequent speaker in the Chicago-land area and instructor in the Newberry Adult Education seminar program.

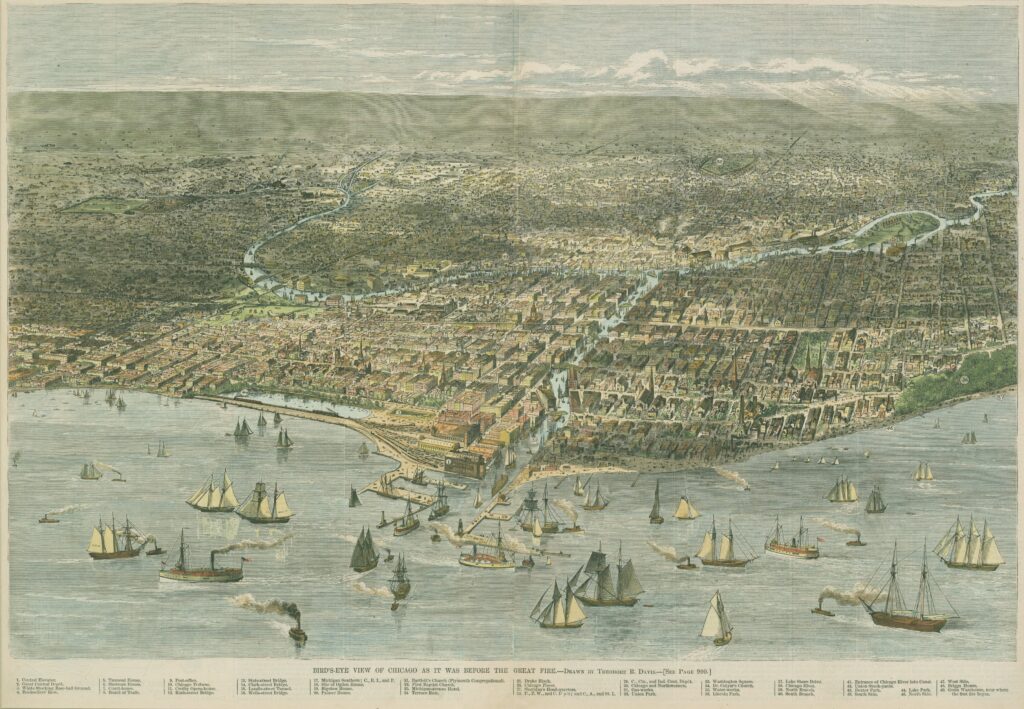

Theodore R. Davis, “Bird’s-Eye View of Chicago as it was Before the Great Fire” (1871)

Richard’s Illustrated and Statistical Map of the Great Conflagration in Chicago (1871)

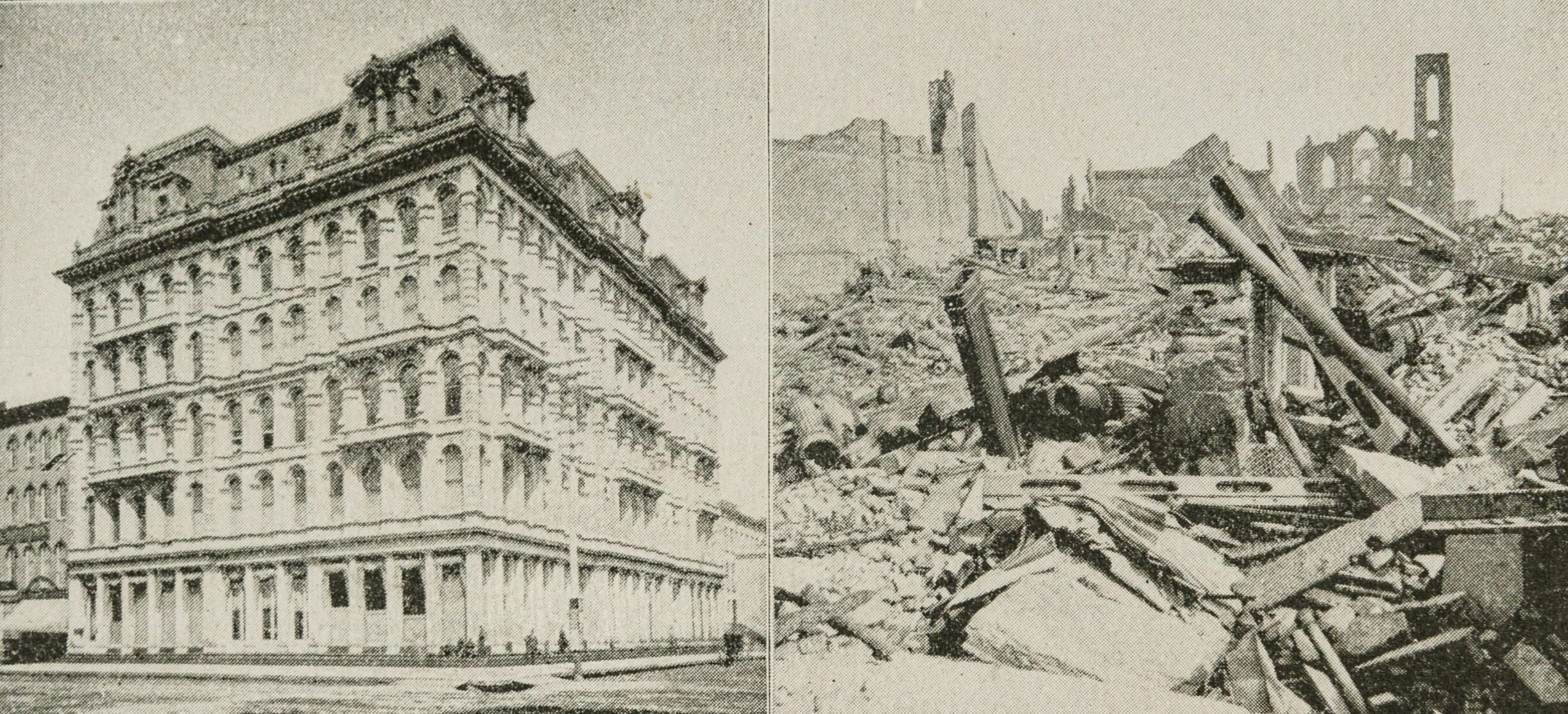

Joseph Kirkland, The Story of Chicago, 310 (1892)

Joseph Kirkland, The Story of Chicago, 311 (1892)

Joseph Kirkland, The Story of Chicago, 333 (1892)

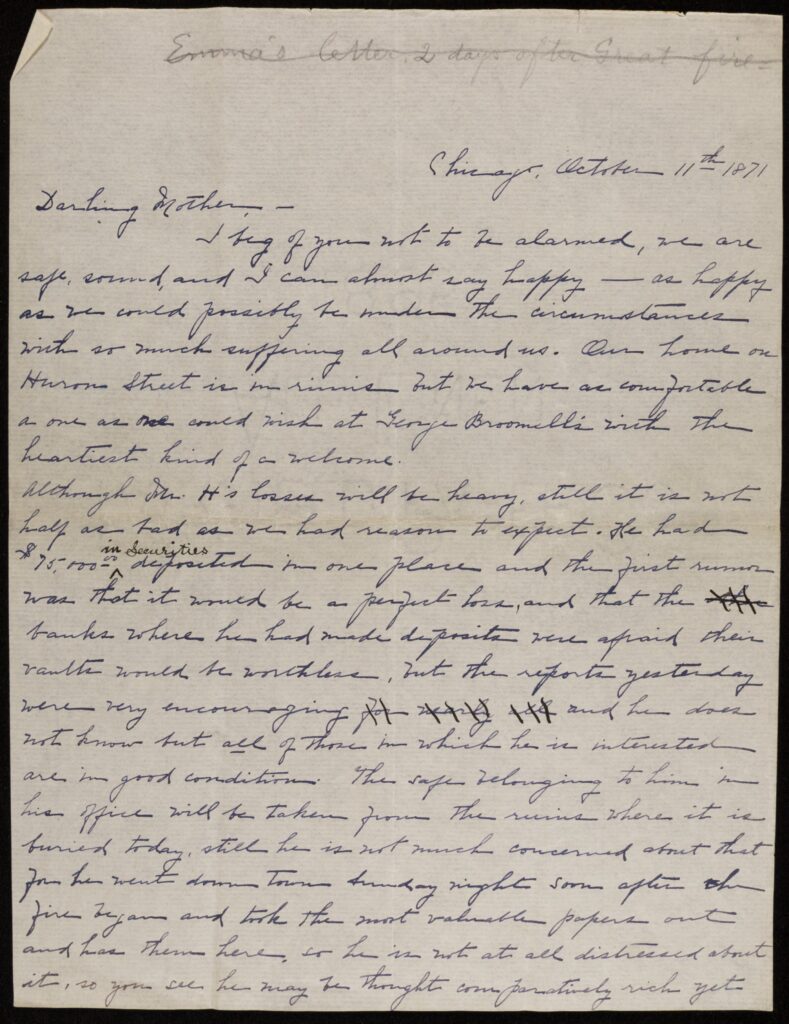

Letter from Emma Lander Hambleton to her mother (October 11, 1871)

Chicago Evening Post, “Chicago in Flames,” 1 (October 10, 1871)

Chicago Evening Post, “Chicago in Flames,” 2 (October 10, 1871)

Proclamation from Mayor R. B. Mason (October 11, 1871)

Charles R. Clark, Photograph of the Aftermath (1871)

Chicago Relief and Aid Society, Chicago Relief: First Special Report of the Chicago Relief and Aid Society, 11 (1871)

Chicago Relief and Aid Society, Chicago Relief: First Special Report of the Chicago Relief and Aid Society, 12 (1871)

Chicago Relief and Aid Society, Chicago Relief: First Special Report of the Chicago Relief and Aid Society, 13 (1871)

Illustrated London News, Great Fire at Chicago: Views of the City, “Ladies of Chicago Supplying the Refugees with Clothing” (1871)

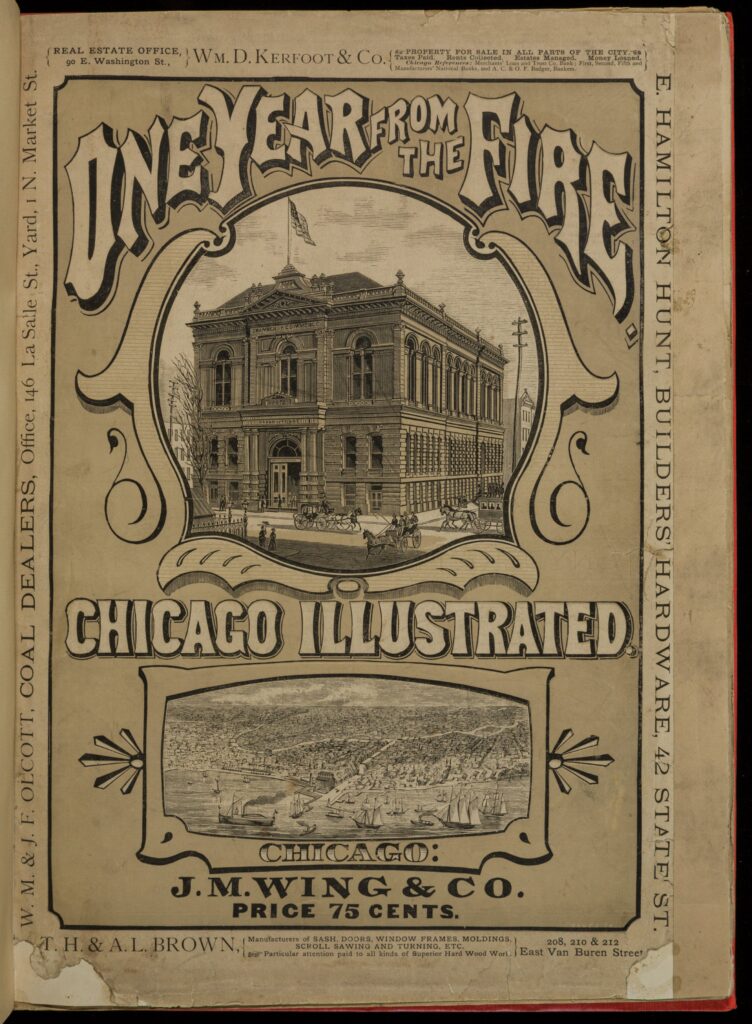

John M. Wing & Co., One Year from the Fire, Front Cover (1872)

John M. Wing & Co., One Year from the Fire, 47 (1872)

John M. Wing & Co., One Year from the Fire, 24 (1872)

Chicago Sun Times, New Chicago: A Full Review of the Work of Reconstruction, Front Cover (1872)

Chicago Sun Times, New Chicago: A Full Review of the Work of Reconstruction, 81 (1872)

Chicago Sun Times, New Chicago: A Full Review of the Work of Reconstruction, 82 (1872)

Chicago Sun Times, New Chicago: A Full Review of the Work of Reconstruction, 83 (1872)

Chicago Sun Times, New Chicago: A Full Review of the Work of Reconstruction, 84 (1872)

Chicago Sun Times, New Chicago: A Full Review of the Work of Reconstruction, 85 (1872)

Selected Sources

Miller, Donald L. City Of The Century: The Epic Of Chicago And The Making Of America. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997, ©1996.

Sawislak, Karen. Smoldering City: Chicagoans And The Great Fire, 1871-1874. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 1995.

Andreas, A. T. History of Cook County, Illinois: From the Earliest Period to the Present Time. Vol 3, Chicago : A. T. Andreas Company. 1886.