Introduction

In the early and mid-nineteenth century, Chicago was a commercial town without the cultural amenities of large East Coast cities like New York, Boston, and Philadelphia. The late nineteenth century saw the establishment of many of the city’s large cultural institutions such as the Art Institute of Chicago, the Field Museum, and the Chicago Symphony. When the Art Institute of Chicago was built, few cities in the United States had an art museum of similar standing. The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries witnessed a rise in cultural philanthropy as the children of gilded age magnates came of age, and directed their considerable wealth and influence towards the cultural life of their home cities.

The city’s elites invested heavily in building a cultural life in Chicago influenced by education and travels in other parts of the United States and Europe. Local cultural philanthropists played a key role in supporting the development of the arts in Chicago through museums, clubs, support of artists and art schools. While perhaps the most obvious example, the Art Institute of Chicago was by no means the only venue for visual art in Chicago. While Chicago’s incredible architecture has often overshadowed its arts scene, Chicago had a thriving artistic community in the early twentieth century.

The early twentieth century was an exciting time in the art world with the emergence of modern art. The 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art, more popularly known as the Armory Show, was a watershed moment in the direction of Chicago’s arts scene. The Armory Show started in New York City, and was hosted at the Art Institute of Chicago. The show featured works by artists such as Vincent Van Gogh, Henri Matisse, and Claude Monet to a curious public. The show elicited strong opinions from viewers, and protests from students at the School of the Art Institute. However, showing a range of avant garde art in a museum setting opened the doors to do what was possible in art. The incredible success of the Armory Show inspired not only Chicago artists, but also philanthropists and arts groups such as the Art Club of Chicago to bring new art to Chicago.

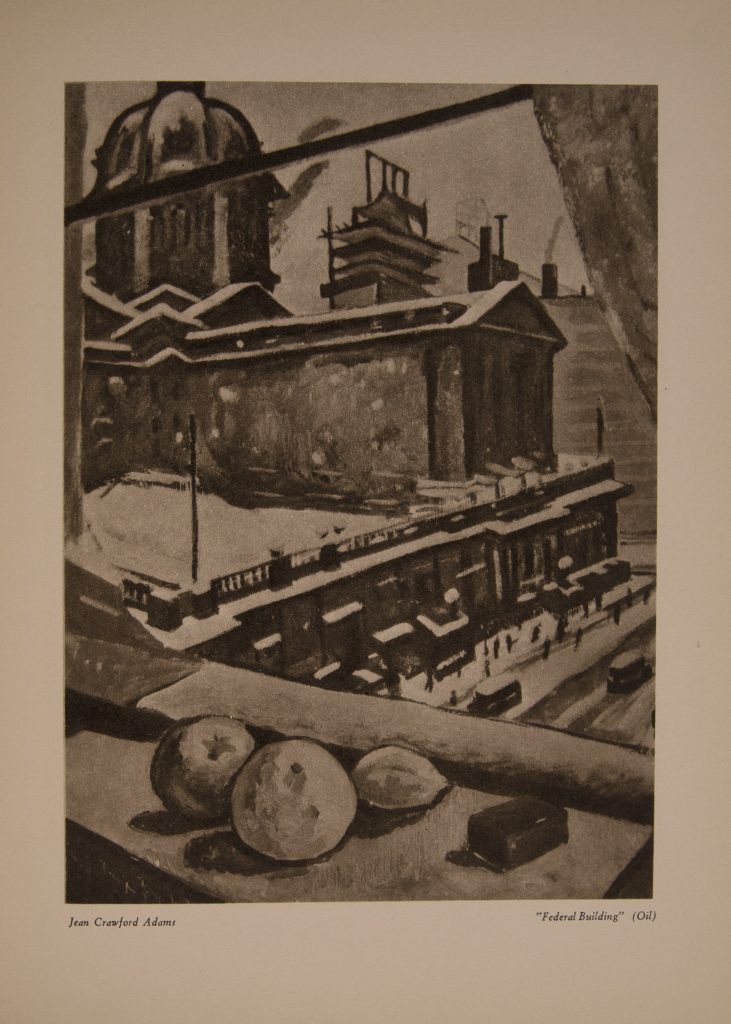

In the early twentieth century, Chicago was a thriving center for arts education. Perhaps the most famous art school was the School of the Art Institute. Artists came to Chicago from other states and countries, and some made Chicago their home. Other artists such as Grant Wood and Georgia O’Keefe studied at the School of the Art Institute, but did not stay in Chicago. One of the challenges in telling the story of Chicago art is defining Chicago art. What makes an artist a Chicago artist, and what makes a piece of art Chicago art? Is it where someone studied art? Is it the subject matter of the artwork, or where it was produced? However one chooses to define what fits under the umbrella of Chicago, art, art played an important role in Chicago’s cultural life.

Essential Questions

- What is the value in art?

- How has art shaped Chicago, and how has Chicago shaped visual art?

- What groups, organizations, and individuals influenced the arts in Chicago in the early twentieth century?

Chicago Art

Charles Hutchinson was the first president of the Art Institute of Chicago, serving from it’s founding into the 1920s. A wealthy businessman and prominent Chicago citizen, the Art Institute of Chicago was Hutchinson’s passion project. Hutchinson believed that building a museum like the Art Institute was an exercise in democracy because art could be appreciated by people of all classes. Hutchinson believed in the mass appeal of art, because all people, regardless of social background, can appreciate the beauty of art. Many museums in the late nineteenth century were founded by cultural philanthropists to serve as vehicles for community uplift through the education of the working classes. Hutchinson similarly believed that art had the capacity to serve as an agent of community uplift. To make the museum accessible to working class, the Art Institute offered free admission several days a week, including Sundays.

Nine years after Hutchinson’s death, it was the Art Institute that hosted the legendary Armory Show that opened up new possibilities for Chicago artists. The years following the Armory Show saw a gradual acceptance of modern art from both the public, and Chicago’s more conservative arts institutions. By 1933, the year of the Century of Progress International Exposition, modern art’s place in the wider art world, and the Chicago’s art scene was secure. The book, Art of Today: Chicago 1933, published in 1932, was a groundbreaking book because of its focus on modern art, and its attention to Chicago artists. It was the first book to focus on contemporary art in Chicago.

Selection: Art of Today: Chicago 1933, Introduction (1932).

Questions to Consider

- How do the introduction of Art of Today and Charles Hutchinson’s speech characterize the purpose and value of art? According to Hutchinson, who is art for?

- How does Jane Crawford Adams describe the influence of Chicago on her art?

Arts Clubs

Large arts institutions like the Art Institute of Chicago played a starring role in establishing Chicago’s arts and culture scene. In addition to these cultural institutions, Chicago boasted a number of arts clubs and organizations that also contributed to the rich artistic life of the city. This section contains documents related to three of these clubs: the Three Arts Club, the Dill Pickle Club, and the Art Club of Chicago.

The Three Arts Club building opened in 1914 to provide safe and affordable accommodations for young female artists to live and pursue education and work in the arts. The club’s name refers to the three arts of music, painting, and theater that residents were expected to pursue. There were similar three arts clubs in other cities including New York, Paris, and London. The club attracted female artists to Chicago, and made it possible for women to develop their careers in the arts.

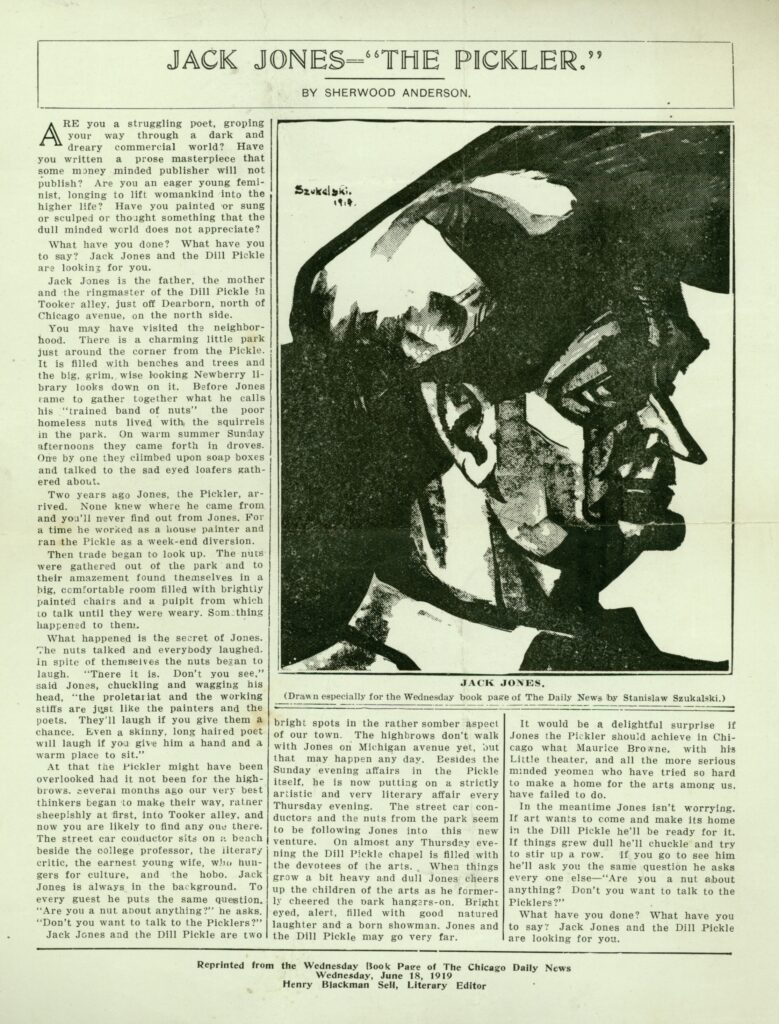

The Dill Pickle Club was a bohemian club popular with Chicago activists, writers, intellectuals, and other nonconformists from the 1910s to the 1930s. The Dill Pickle was founded by labor activist and former Industrial Workers of the World organizer, Jack Jones. In addition to fostering the exchange of new and radical ideas through debates and lectures, the Dill Pickle also hosted theater presentations, poetry readings, musical performances, and art classes.

The Art Club of Chicago was founded in 1916 as a private club to bring international and modern art to Chicago. Inspired by the success of the Armory Show in 1913, the Art Club of Chicago focused on bringing in cutting-edge and international artworks, and hosting lectures and performances for elite art lovers. Rather than creating a large permanent collection like the Art Institute, the Art Club of Chicago focused on curating and hosting a variety of shows. The Art Club of Chicago’s membership included many of the city’s prominent cultural philanthropists as well as artists. Unlike the Dill Pickle Club and the Three Arts Club which are now defunct, the Art Club of Chicago remains an active organization promoting the arts in Chicago.

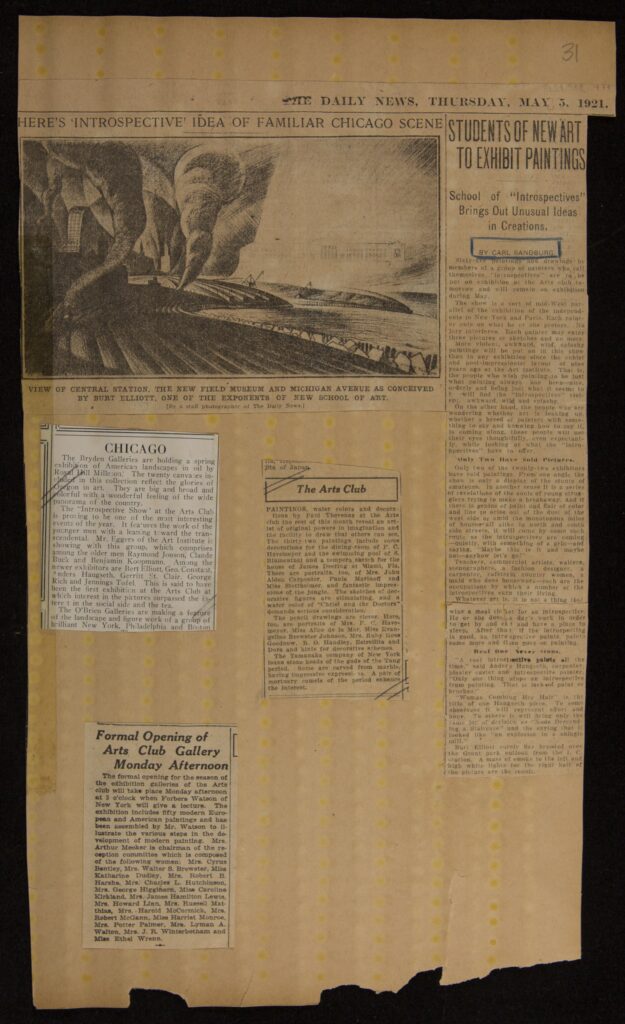

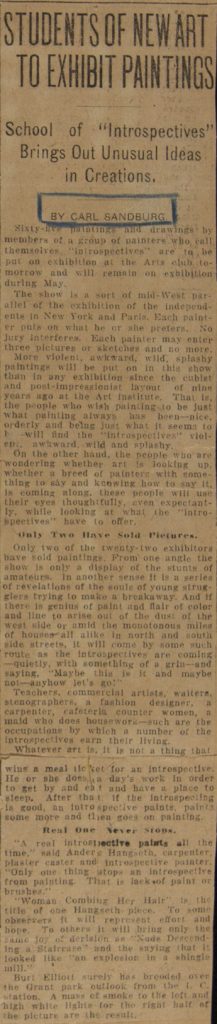

Selection: Arts Club of Chicago, Scrapbook Page, detail: Carl Sandburg, “Students of New Art to Exhibit Paintings” (1921).

Questions to Consider

- According to Carl Sandburg’s article in the Art Club scrapbook, how did clubs and arts groups shape the art scene in Chicago?

- Look at the photograph of the Three Arts Club building. What elements of the building indicate the building’s purpose?

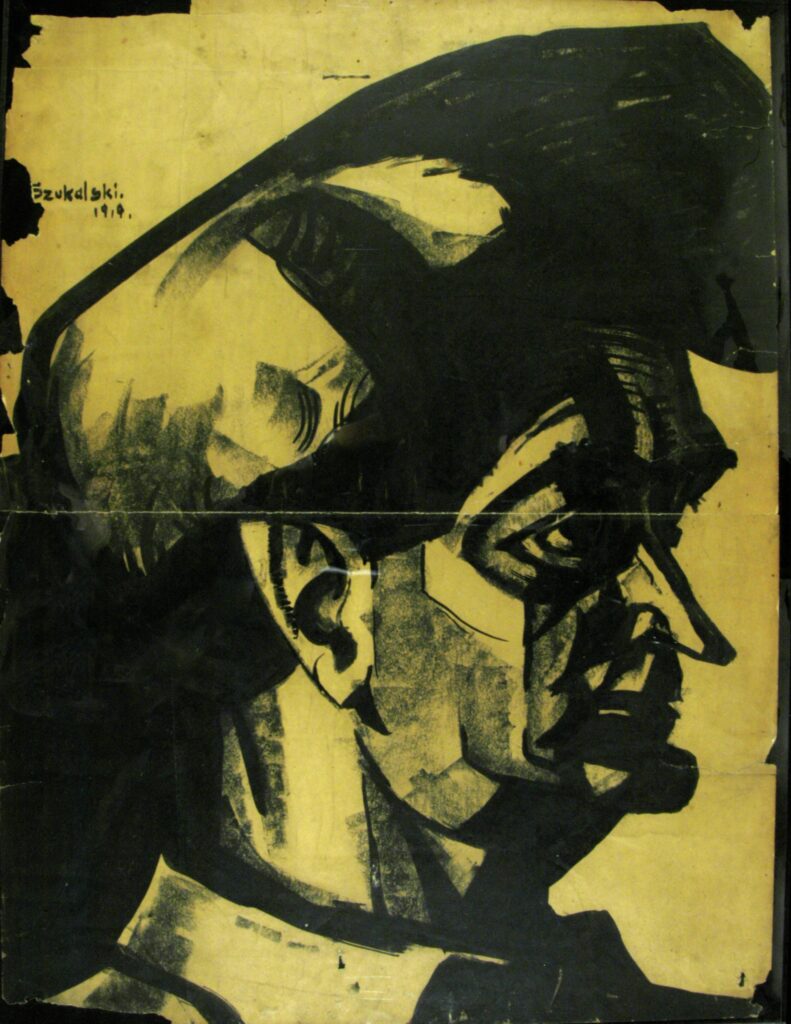

- Compare the original portrait of Jack Jones, and the portrait as it is printed in the article. How does the medium change the effect? What about Jack Jones was the artist trying to convey through the style of his portrait? Does it match the message in the article?

- What do the Carl Sandburg and Sherwood Anderson pieces indicate about the relationship between the visual arts and Chicago’s literary community?

Public Art

Local philanthropists contributed to the arts both financially, and through the donation of artworks. Their collection and patronage of the arts brought important pieces of art to Chicago, and shaped the development of collections of arts institutions. While many of these philanthropists were private collectors, there was also an emphasis on art for the public.

In 1905, Chicago philanthropist and lumber magnate, Benjamin Ferguson left in his will one million dollars for the creation of public art around Chicago. The fund was administered by the Art Institute of Chicago which was instructed to use the funds for, “The erection and maintenance of enduring statuary and monuments, in whole or in part of stone, granite or bronze in the parks, along the boulevards or in other public places.” The Ferguson Fund sponsored the creation of well-known sculptures around Chicago such as the Statue of the Republic in Jackson Park, and The Bowman and The Spearman at Congress Plaza.

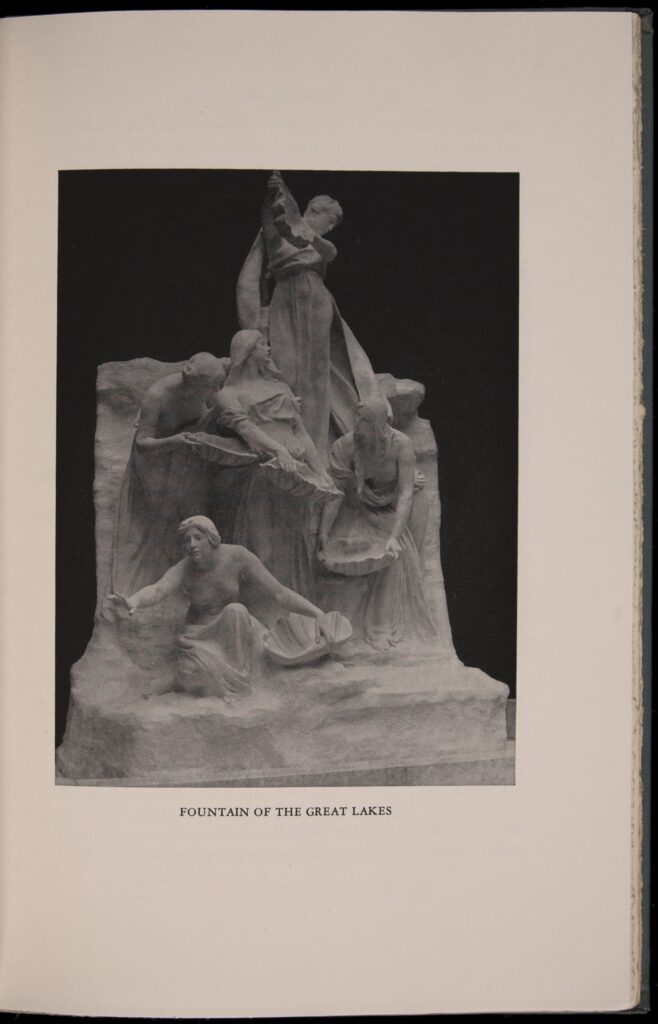

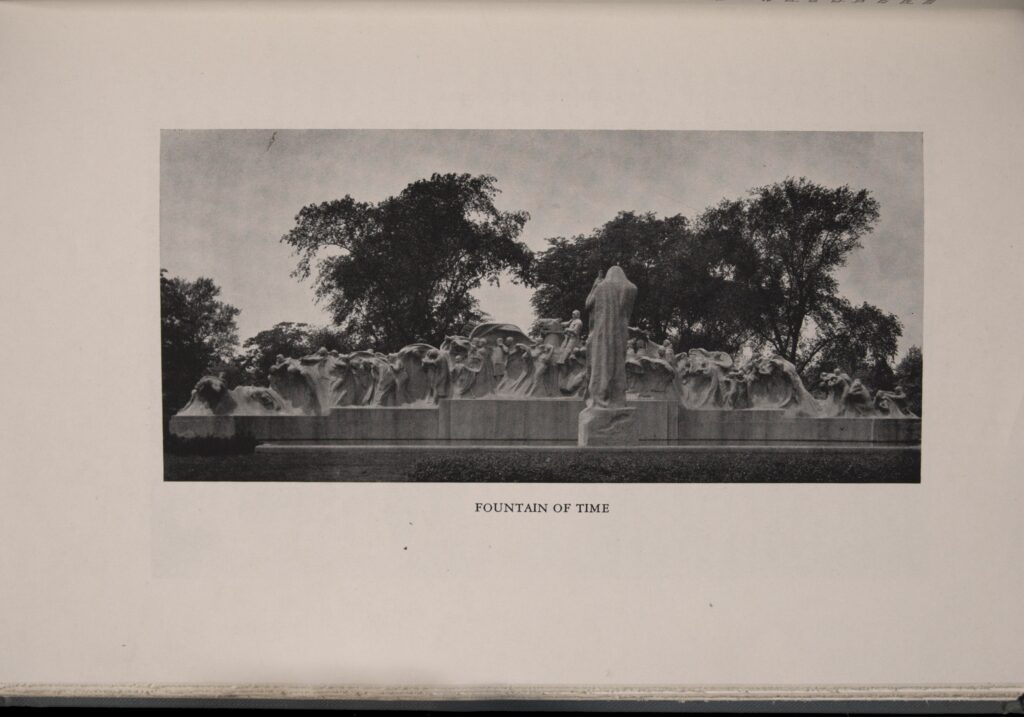

The first work commissioned by the Ferguson Fund was Lorado Taft’s allegorical Fountain of the Great Lakes with five women representing each of the Great Lakes, and they was the lakes flow into each other. Lorado Taft was a sculptor and writer from Illinois who is perhaps best remembered for the fountains and sculptures he created. Taft’s studios were located on the Midway Plaisance on Chicago’s South Side, close to where another Ferguson Fund project was erected, The Fountain of Time. The inspiration for The Fountain of Time was the opening line of English poet, Henry Austin Dobin’s poem, “Paradox of Time,” “Time goes, you say? Ah no, Alas, time stays, we go.” The fountain was commissioned to commemorate the hundred years of peace between the United States and Great Britain since the 1814 Treaty of Ghent. The fountain was meant to be part of a much larger Midway beautification plan, but by 1922 when the fountain was dedicated, the plan for further work at the Midway had been scrapped.

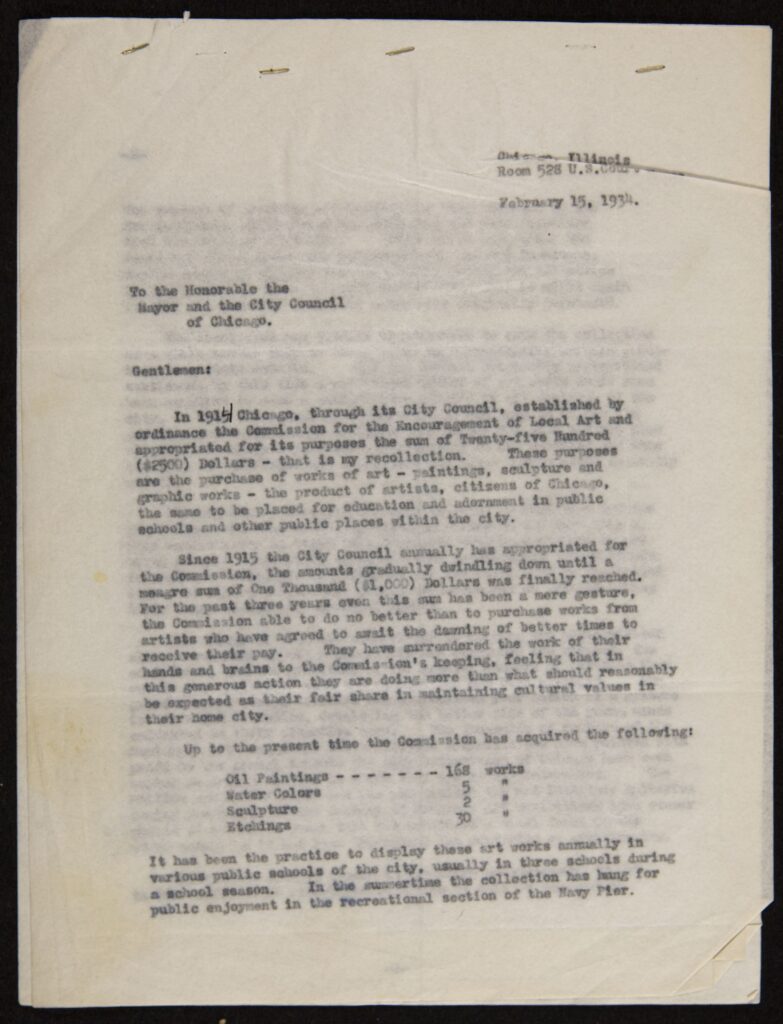

In addition to the Ferguson Fund and gifts of other philanthropists, the city of Chicago also contributed to the advancement of public art. Carter Harrison was a five term Democratic mayor of Chicago, and a supporter of the arts. In 1914, Harrison oversaw the formation of the Chicago Commission for the Encouragement of Local Art. The purpose of the Commission was to purchase and display works of Chicago artists in Chicago Public Schools and other municipal buildings. The Commission had seven members; three were selected by the Art Institute of Chicago, one by the Mayor of Chicago, and one each by the Palette and Chisel Club, the Municipal Art League, the Friends of American Art. The Great Depression caused a severe reduction in funding for acquisitions by the Chicago Commission for the Encouragement of Local Art, and even saw artists struggle receive payment for their work. While city funding for public art was greatly reduced, as Harrison noted in his letter, the 1930s saw enormous support for the arts through the federal funding of the New Deal.

Selection: Carter Harrison to the Chicago City Council (February 15, 1934)

Questions to Consider

- Lorado Taft’s Fountain of Time and Fountain of the Great Lakes are allegorical fountains, which means they symbolically represent abstract ideas. Look closely at each fountain, what do you think the message of each fountain is? Support your answer with visual clues from the fountain.

- Draw your own example of a fountain inspired by Dobson’s line, “Time goes, you say? Ah no, Alas, time stays, we go.”

- According to the letter from Carter Harrison, why should cities invest in public art? What kind of art did Chicago invest in, and who decided on the pieces?

Chicago Art and its Institutions

Chicago’s arts scene grew rapidly in the early twentieth century as a result of cultural philanthropy and the city’s recently established arts clubs and institutions.

Public Art in Chicago

Local philanthropists also contributed significantly to the increase in public art in Chicago.

Further Reading

Bluestone, Daniel M. Constructing Chicago. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991.

Brown, Milton W. The Story of the Armory Show. Joseph H. Hirshhorn Foundation; distributed by New York Graphic Society. Greenwich, Conn., 1963.

Garvey, Timothy J. Public Sculptor: Lorado Taft and the Beautification of Chicago. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988.

Hilliard, Celia. The Prime Mover: Charles L. Hutchinson and the Making of the Art Institute of Chicago. Chicago, Ill: Art Institute of Chicago, 2010.