Introduction

On his first day in office in 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt told the American people, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

But Americans had much to fear in 1933. The Great Depression had entered its fourth year, and 25 percent of Americans were unemployed. Americans worried about Communist agitators and other subversives undermining democracy at home. Widely held beliefs in eugenic “science” and pervasive fear of foreigners led the US Congress to pass quota laws that had severely restricted immigration to the United States since 1924. Public facilities, schools, and churches were racially segregated, with discrimination against African Americans enforced both by law and violence, including lynching. Anti-Catholic and antisemitic prejudices were commonplace, and on the rise.

Some Americans also worried about increasingly unstable political conditions abroad. Just five weeks before FDR told Americans not to be afraid, democracy gave way to fascism in Germany as Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler became Chancellor.

These documents from the Newberry Library’s collection reveal some of the many ways that the US government and the American people responded to Nazism during this time of deep uncertainty. Many observers today assume that Americans knew little about Nazi Germany, especially its plan to destroy Europe’s Jews. This assumption is not correct. On the contrary, Americans had access to a great deal of information about the dangers of Nazism, including knowing much about the persecution of Jews as it was taking place.

During the 1930s and ‘40s, however, the vast majority of Americans did not think of Nazism primarily as a threat to Europe’s Jews, as we do today. Most Americans thought of Nazism first as a threat to democratic nations and democratic values, rather than to Jews, and the United States ultimately mobilized 16 million troops to join the Allied effort in a war to save democracy. Rescuing Jews targeted for murder by Nazi Germany was never a priority for the United States as it fought this war.

Despite the steady flow of information into the United States about the desperate plight of Europe’s Jews, many Americans simply couldn’t imagine that the news was true. The American people may have had trouble believing the extent of Nazi Germany’s crime because they did not have a name for it. As British Prime Minister Winston Churchill told radio listeners on August 24, 1941, “We are in the presence of a crime without a name.”

Raphael Lemkin, a Jewish refugee from Poland who immigrated to the United States in 1940, coined the word “genocide” in 1944 to name this crime. The word “genocide” had not existed before then, and the destruction of Europe’s Jews was not called “the Holocaust” while it was occurring. It was not until well after the end of World War II that the word “Holocaust” was used regularly to describe Nazi Germany’s crimes.

Without a name for the crime—whether it be “genocide” or “Holocaust”—Americans also had trouble believing the scale and scope of such a crime against civilians, especially because it was committed by what was perceived to be one of Europe’s most civilized nations. Pointing out Americans’ failure of imagination in this instance should not be misinterpreted as excusing American inaction in the face of Nazi Germany’s genocidal crimes, but instead should be considered as we acknowledge the fact that human beings often have trouble making sense of historical events without the benefit of hindsight.

A critical challenge as you approach this collection of documents, then, is to try to put hindsight aside. As historian Walter Laqueur explained, “Nothing is easier than to apportion praise and blame, writing many years after the events. . . .It is very easy to claim that everyone should have known what would happen once Fascism came to power. But such an approach is ahistorical.” Taking Lacquer’s warning to heart means trying to empathize with Americans of the 1930s and ‘40s as you read these documents, and considering carefully what Americans knew about Nazism, as well as what they believed and how these beliefs were shaped.

During the twelve years that Nazis were in power (1933–1945), Americans disagreed vehemently about how significant a threat German Chancellor Adolf Hitler posed to the world. Americans also debated whether to admit refugees, intervene in war, or rescue Jews targeted for murder. Each section of this digital collection includes documents that are intended to both demonstrate what Americans knew about Nazism at a particular moment in time, and what they thought the US government and individual Americans should do to respond.

Please consider the following questions as you review the documents:

- What did Americans know about Nazism during the 1930s and ’40s?

- What actions did Americans take in response to Nazism?

Early Views of Hitler

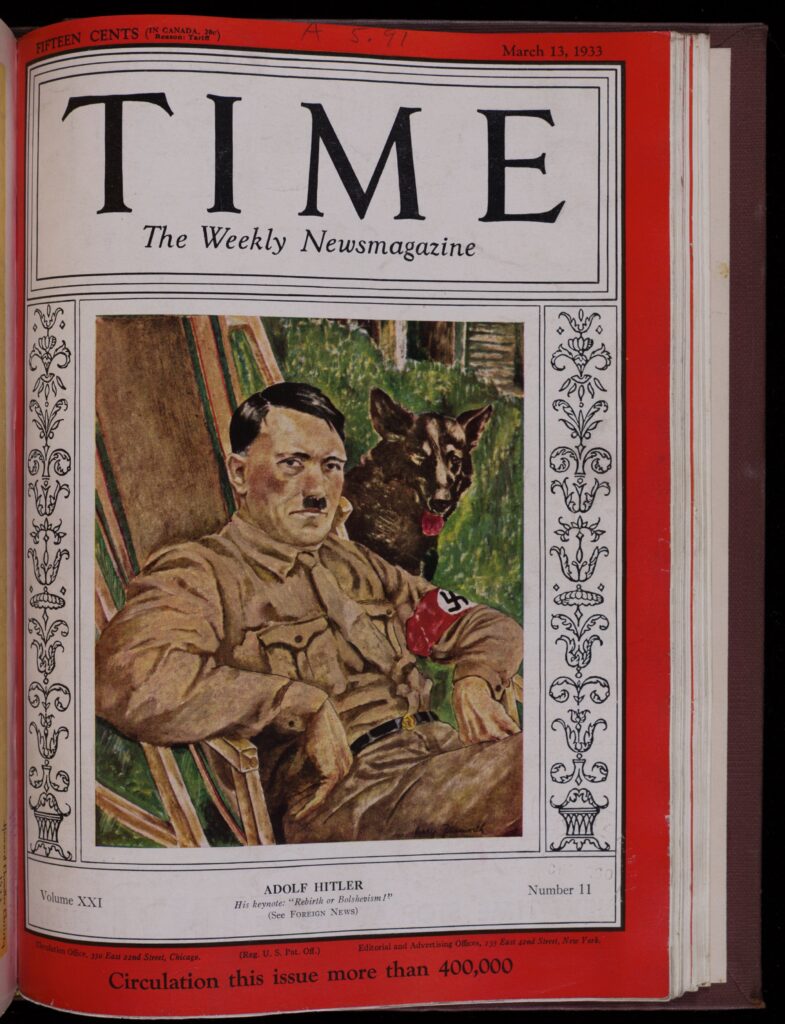

American reporters and politically engaged citizens took great interest in the dismantling of democracy and the rise of fascism abroad during the 1930s. Foreign leaders Benito Mussolini, Francisco Franco, and Adolf Hitler received regular coverage in the American press.

The earliest American press coverage of Hitler often focused on his rabid, obsessive antisemitism. Reporters noted that he blamed Jews for the ills of Germany and of the world, while also imagining international Jewish conspiracies secretly controlling communist and democratic nations alike.

Selection: Horace J. Bridges, Hitlerism and the German Jews: An Address (1933)

When Hitler became Chancellor in 1933, President Roosevelt told his nominee for US Ambassador to Germany William Dodd that Nazi Germany’s persecution of Jews was troubling, but the President also emphasized that the US government had to respect Germany’s sovereignty in dealing with its own Jewish citizens. Some Americans, including Horace J. Bridges of Chicago’s Ethical Society, disagreed with this premise, and encouraged Americans to raise their voices in protest against Nazi Germany.

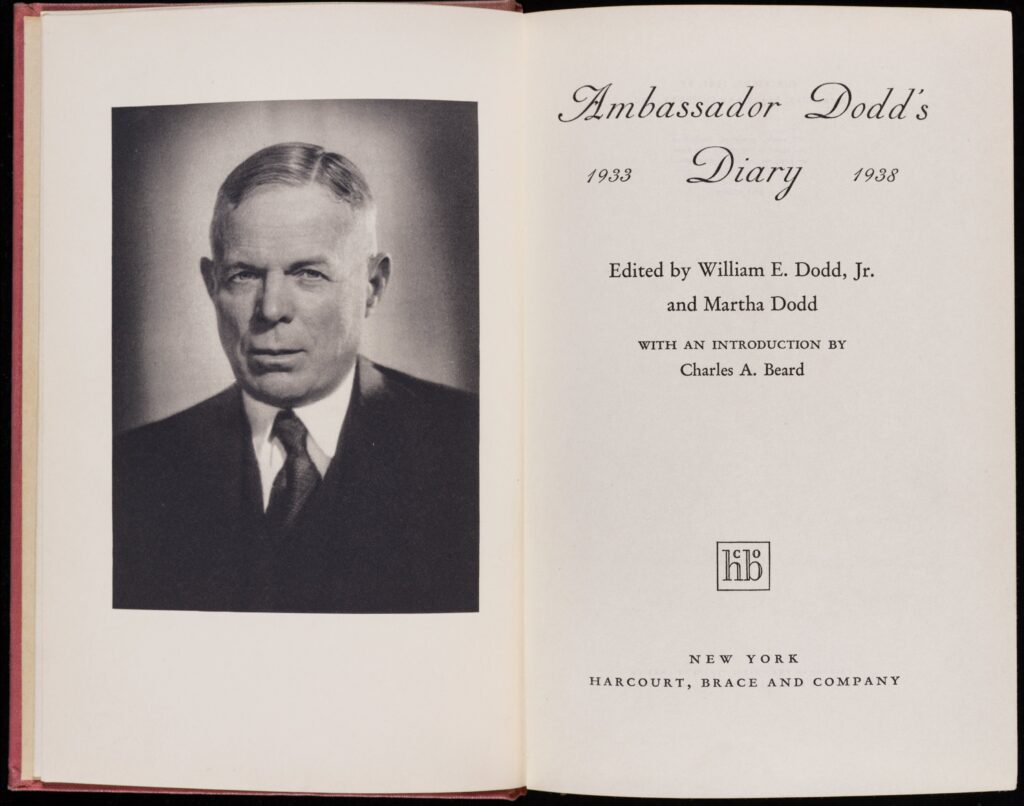

Selection: William Edward Dodd, Ambassador Dodd’s Diary (1941)

Questions to consider:

- How do these documents portray Adolf Hitler? How do they understand the dangers of Nazism?

- What do these documents teach us about how Americans understood their responsibility to respond to Nazi Germany in the early years of Hitler’s rule?

Nazis in America

During the 1930s, Americans struggled through the devastating Great Depression and witnessed fascism solidify its hold in Italy, Spain, and Germany. Some Americans worried that fascism might come to the United States as well.

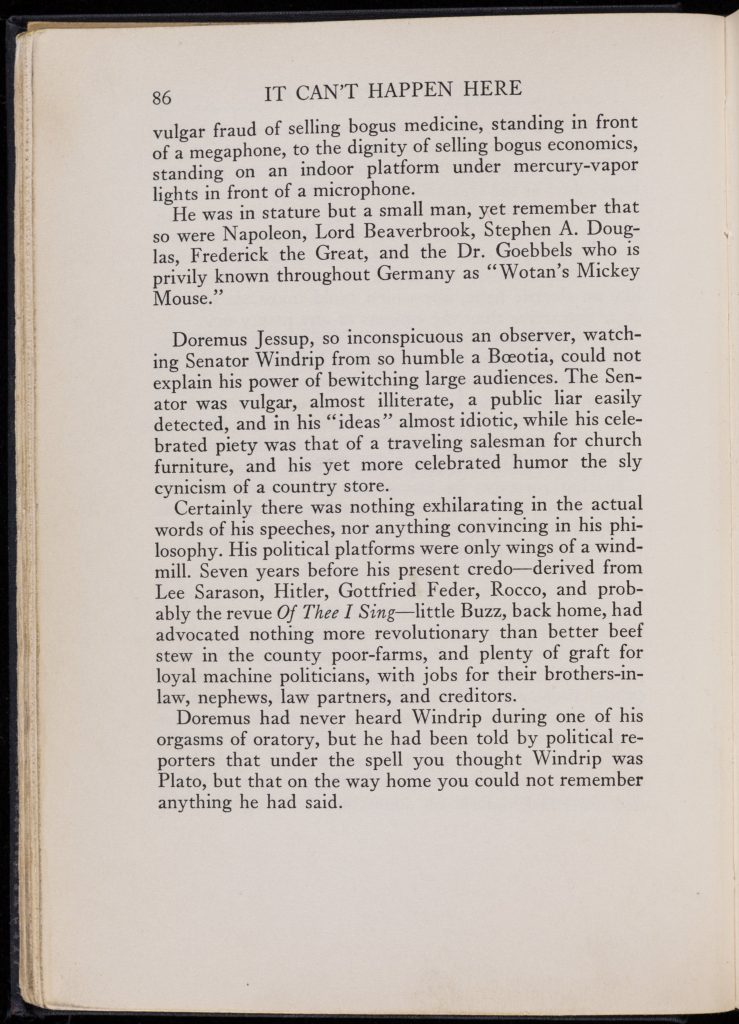

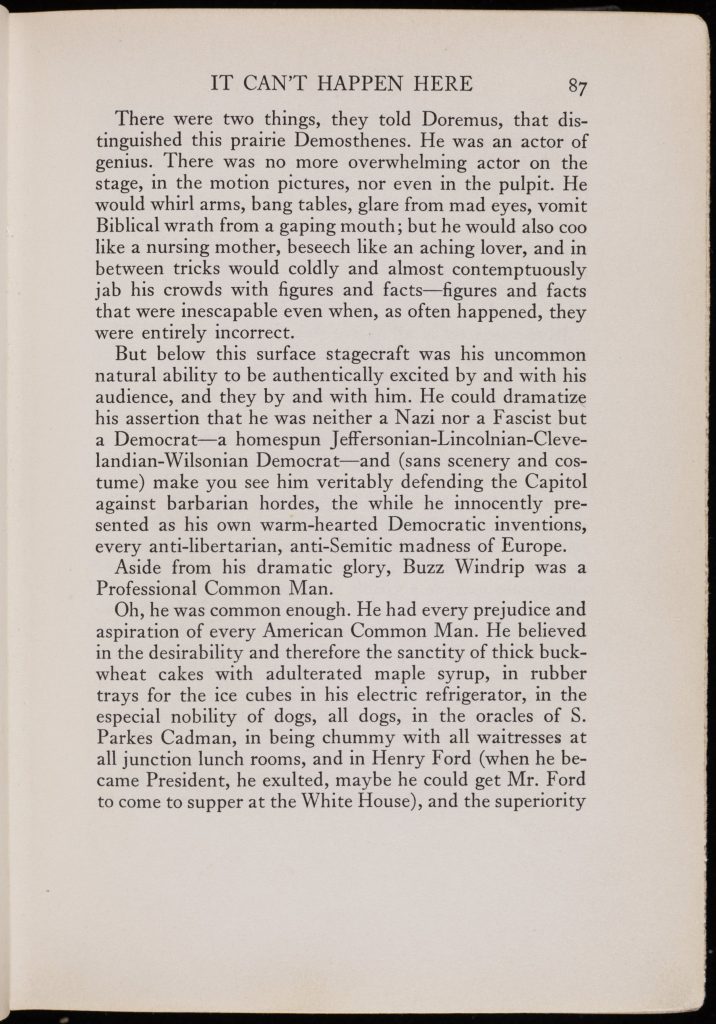

Sinclair Lewis’s 1935 novel It Can’t Happen Here captured Americans’ anxieties about fascism at home. Protagonist Doremus Jessup is a “somewhat sentimental Liberal” who is slow to realize the dangers of American fascism. Berzelius Windrip—a folksy New Englander with characteristics reminiscent of Louisiana Senator Huey Long, radio priest Charles Coughlin, and Adolf Hitler himself—becomes President of the United States and ushers in totalitarianism. It Can’t Happen Here became a national bestseller and was dramatized and performed in many US states by the New Deal Works Progress Administration.

Selection: Sinclair Lewis, It Can’t Happen Here (1935)

A small number of Americans did hope to see Nazism come to the United States. The German American Bund, a pro-Nazi organization established in 1936, revered Hitler. Its members, most of whom were ethnic German-American citizens, were deeply antisemitic and anti-Communist. Fritz Kuhn led the German American Bund, but the organization never received the attention or respect from Hitler that Kuhn hoped it would. In 1937, reporters working undercover for the Chicago Daily Times newspaper infiltrated the German American Bund and wrote a series of articles exposing the organization’s pro-Nazi activities.

Questions to consider:

- How does Sinclair Lewis characterize the political rise of Berzelius Windrip in this passage? What techniques does Windrip use to appeal to Americans? Which Americans find his message most appealing?

- What symbols are evident in the photograph of the 1937 German American Bund banquet? What messages is the German American Bund seeking to communicate through the use of these symbols?

Americans and the European War

Nazi Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. Two days later, Great Britain and France declared war on Germany. World War II had begun.

The US government responded to the war in Europe by confirming its policy of neutrality in international conflicts. On September 3, 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt assured Americans in a fireside chat that the United States would remain “a neutral nation.” As he told radio listeners that evening: “I hope the United States will keep out of this war. I believe that it will. And I give you assurance and reassurance that every effort of your government will be directed toward that end.”

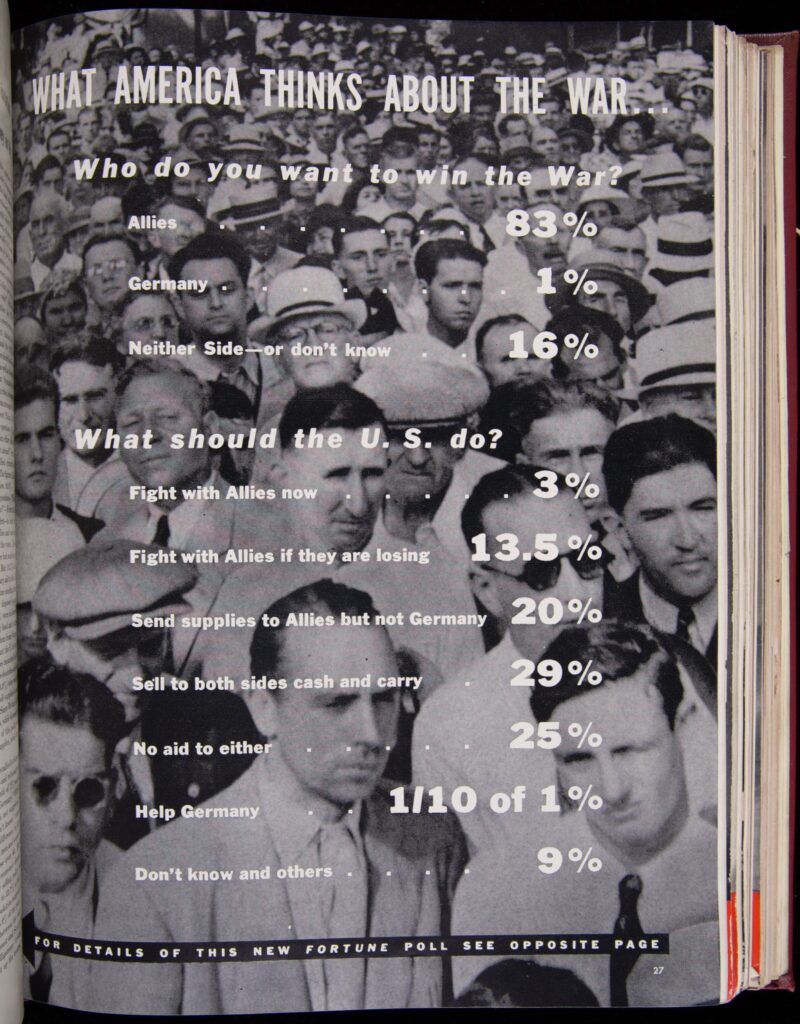

The President’s promise reflected the majority of Americans’ opinion. Public opinion polls throughout 1939 and 1940 showed that most Americans hoped to stay out of the war in Europe. Many thought back to World War I—a significant portion of the population believed that entering the war had been a mistake and that their sacrifices had not been worth it.

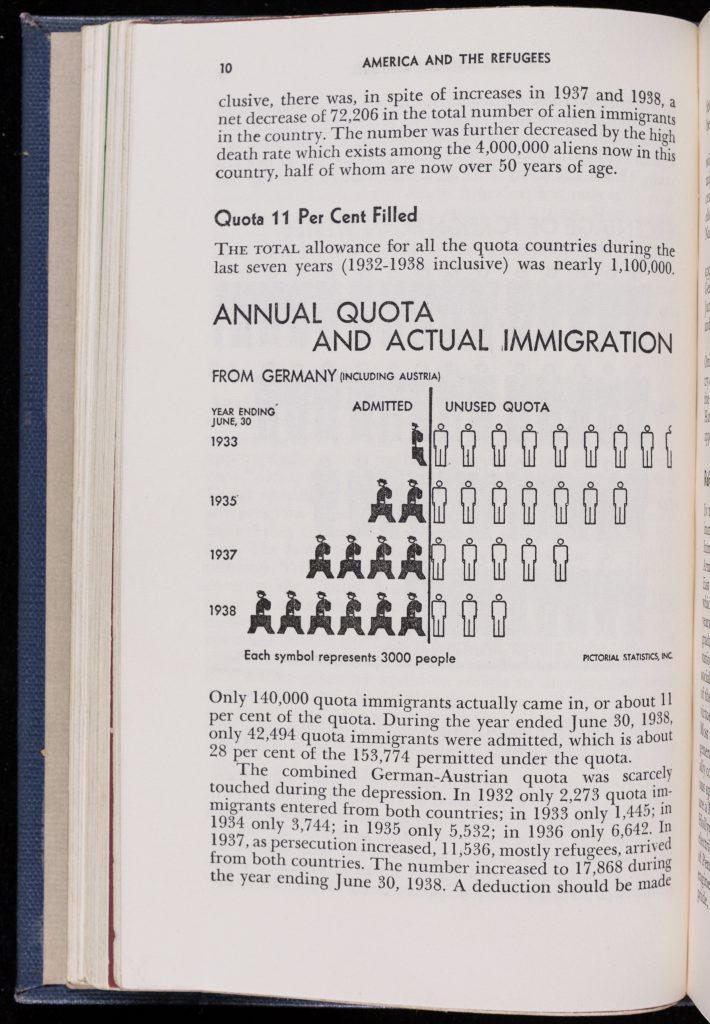

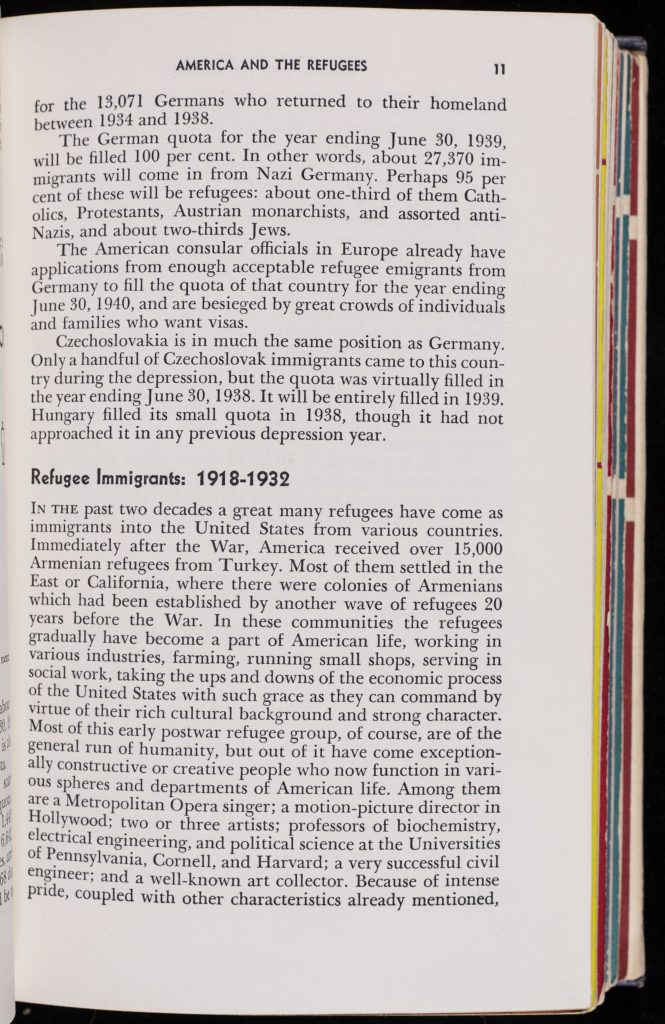

By the time the war in Europe began, Americans understood that European-Jewish refugees faced a crisis as they tried to flee Germany and Nazi-occupied areas. Yet immigration to the United States was severely restricted by quota laws that had been in place since 1924. In the immediate aftermath of terror attacks against Jews across Germany on November 9–10, 1938, (known as “Kristallnacht”), the US government issued the maximum number of immigration visas permissible for Germany under the quota laws. Officials in the US State Department, however, would not admit additional refugees beyond those allowed under existing immigration laws. And the US Congress would not consider liberalizing the nation’s restrictive immigration laws.

Selection: Louis Adamic, America and the Refugees (1939)

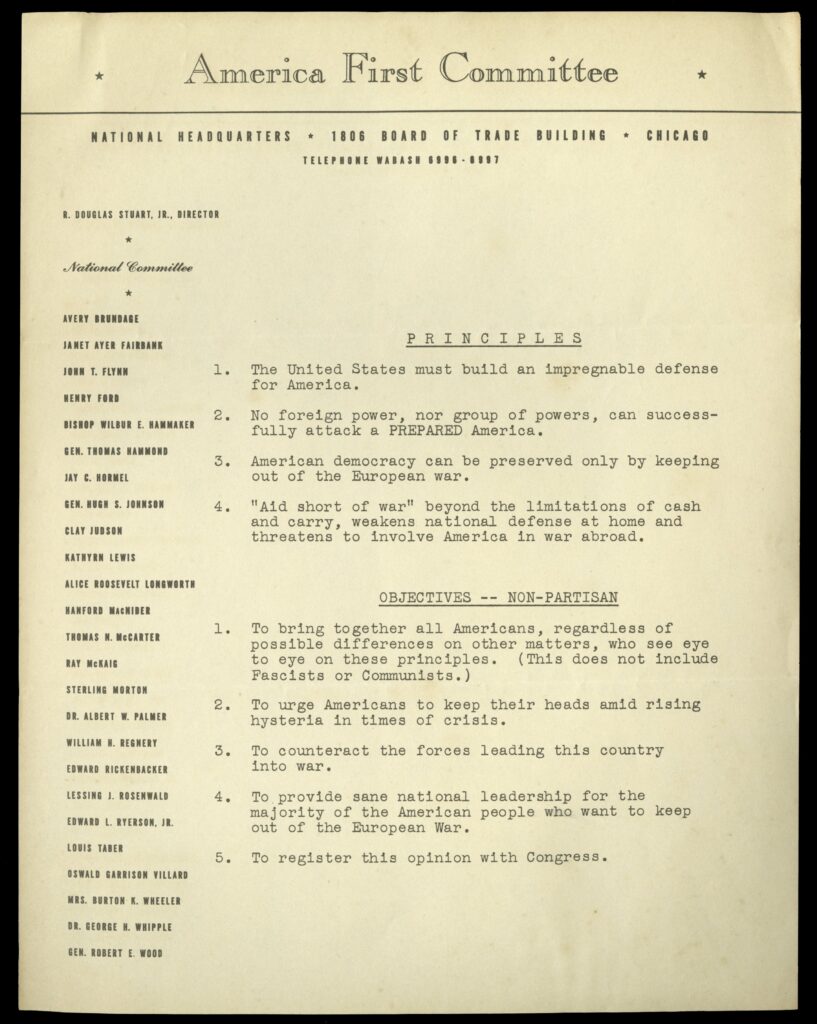

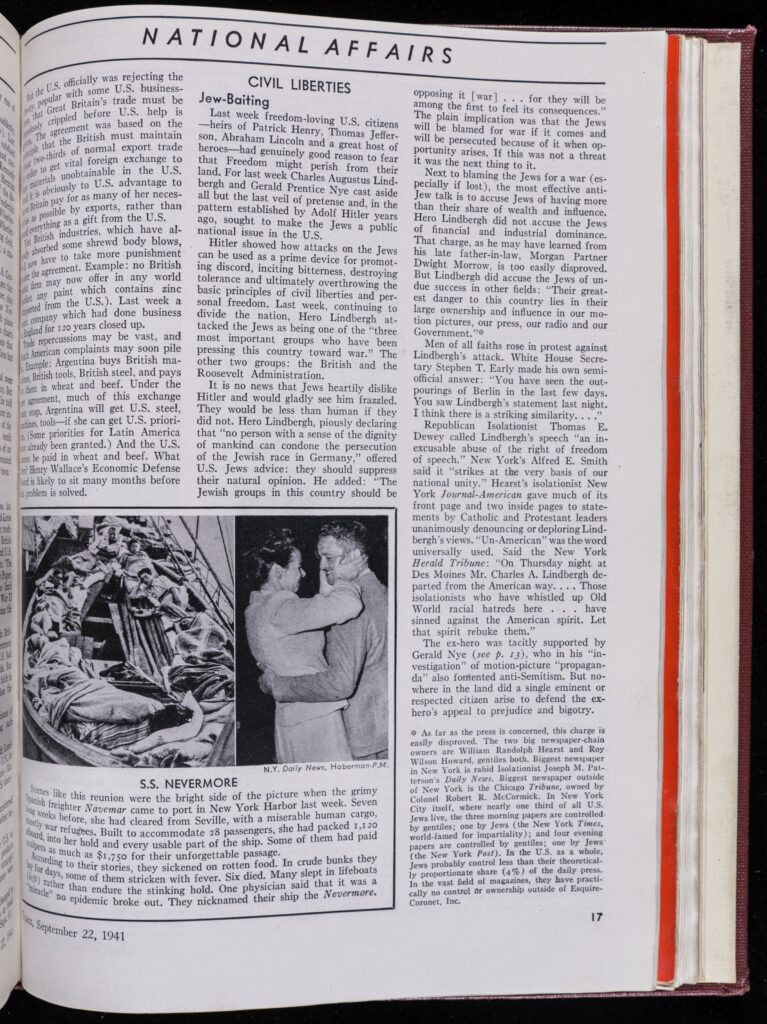

As the war in Europe raged on, Americans’ organized to protest the possibility of the United States entering the war. Students at Yale University founded the isolationist America First Committee in 1940. The organization soon moved its headquarters to Chicago, and the famous aviation hero Charles Lindbergh became its most outspoken supporter. Lindbergh’s antiwar rhetoric took an increasingly antisemitic turn in autumn 1941. The America First Committee disbanded almost immediately after the United States entered the war, following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

Questions to consider:

- What does this Life magazine graphic reveal about Americans’ opinions regarding the threats posed by Nazi Germany? What does it reveal about Americans’ willingness to go to war?

- What did the America First Committee stand for? How did the America First Committee think Americans should respond to the crisis in Europe?

- How does Time magazine report on Charles Lindbergh’s speech for the America First Committee? Why might Lindbergh have been such a divisive figure in 1941?

“We Will Never Die”

In June 1941, Nazi Germany began mobilizing killing squads to murder Jewish civilians in the Soviet Union. By the end of 1941, the first killing center opened in Nazi-occupied Poland. Although Germany’s leaders wanted to keep what they called the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” secret, information about the killing operations reached the US State Department in summer 1942. By November 1942, the “Final Solution” was public knowledge, reported in many American newspapers.

American Jews were always divided about how to respond to Nazi Germany. Some Jewish leaders felt that they should work quietly, behind the scenes, to try to influence government officials. Peter Bergson—an outspoken critic of US government inaction and advocate for rescue of Europe’s Jews—was different. He enlisted a group of like-minded activists, including Hollywood stars and writers, to publicly and forcefully challenge the US government to initiate a policy to rescue Europe’s Jews.

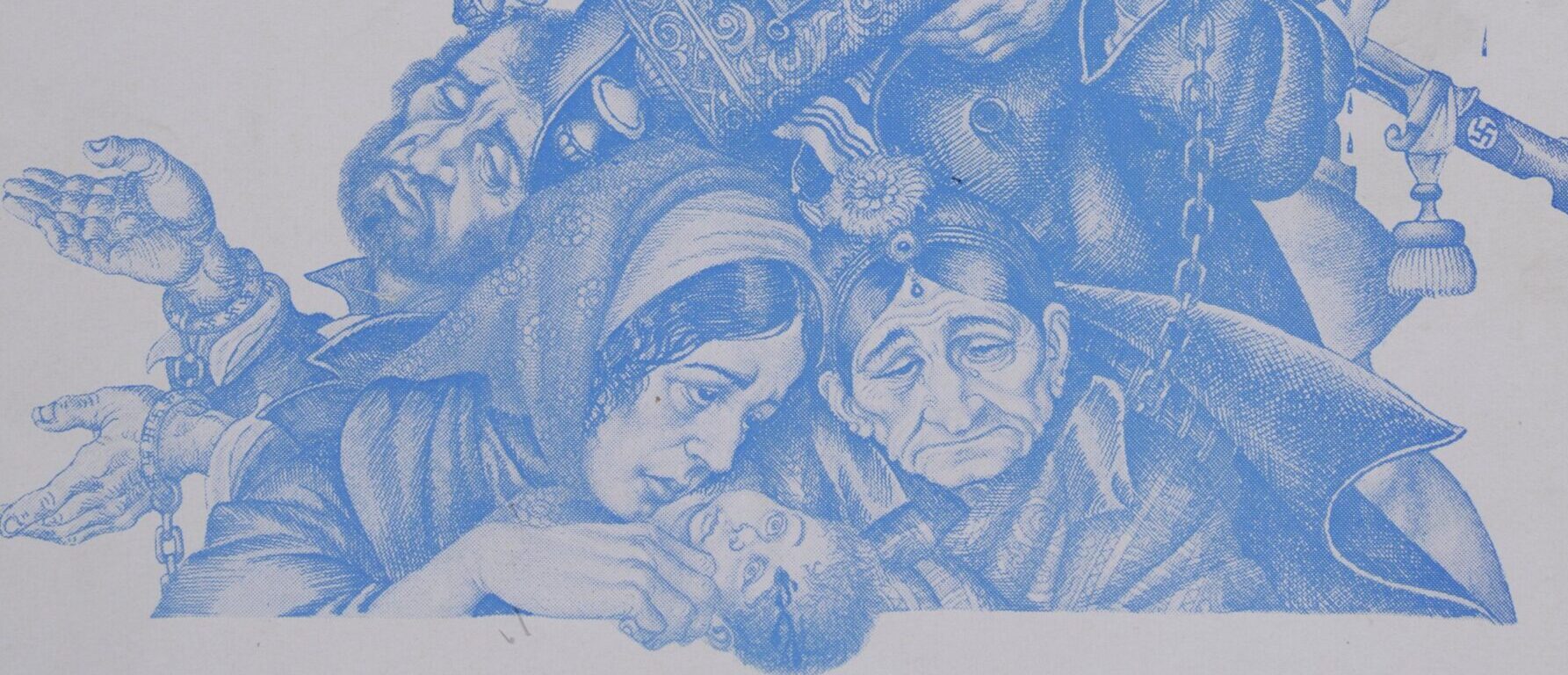

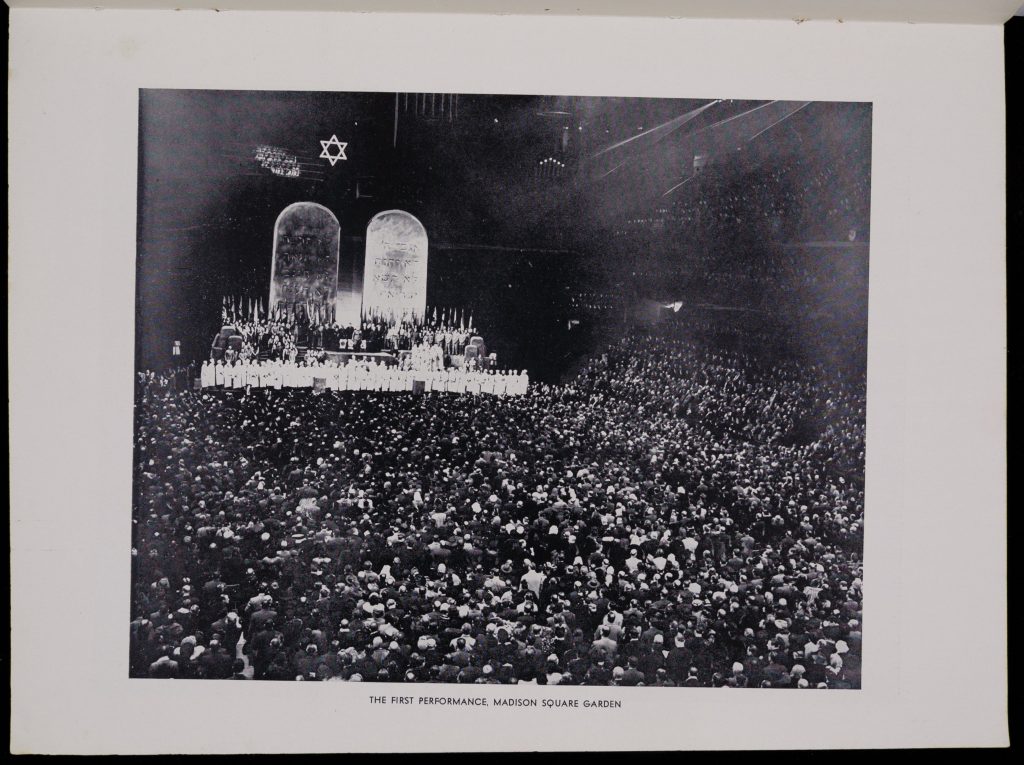

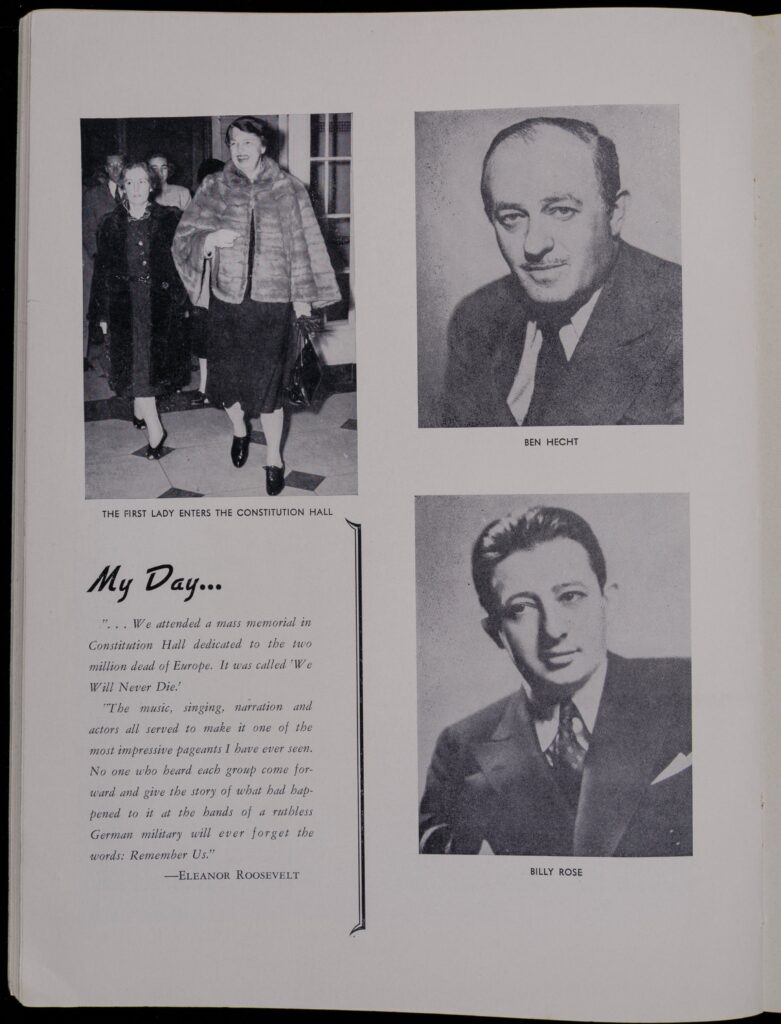

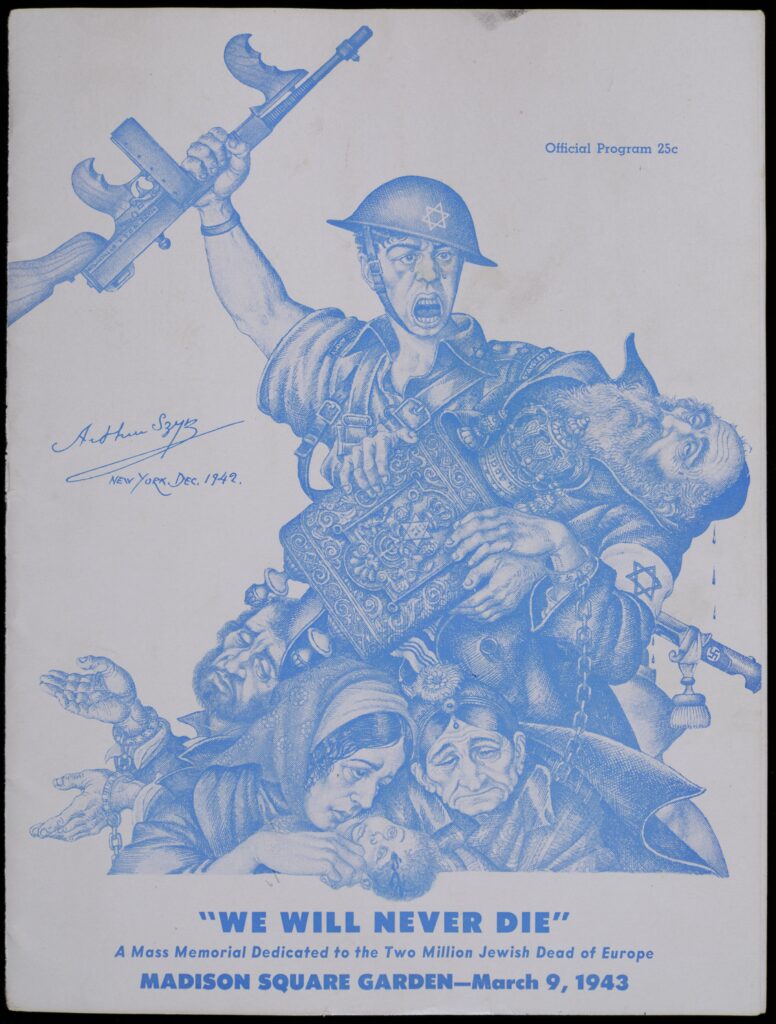

Selection: Photographs from “We Will Never Die” (1943)

Ben Hecht, a Chicago journalist who became an Academy Award–winning screenwriter, found many opportunities to support Bergson’s cause. Hecht wrote numerous full-page newspaper ads intended to shock American readers out of complacency about the massacre of European Jewry. In April 1943, “We Will Never Die,” a melodramatic pageant written by Hecht, was staged in half a dozen US cities. The pageant told the story of Jewish history and warned that all the Jews of Europe would be destroyed if no nation stepped in to stop Nazi Germany’s slaughter.

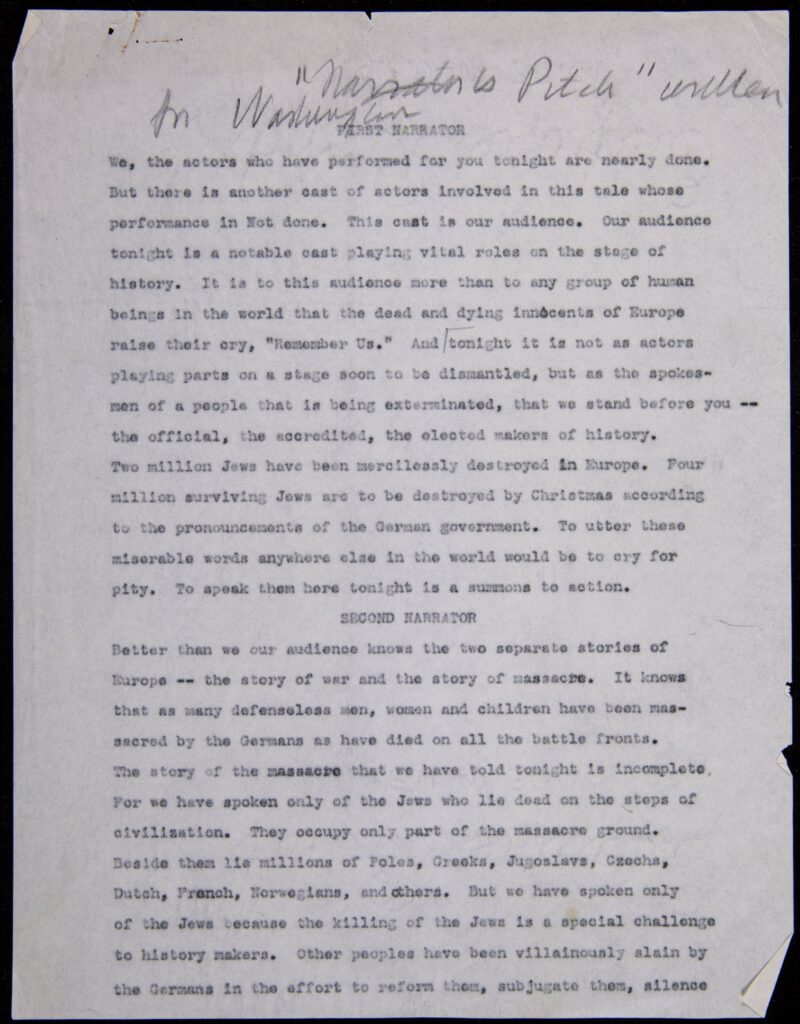

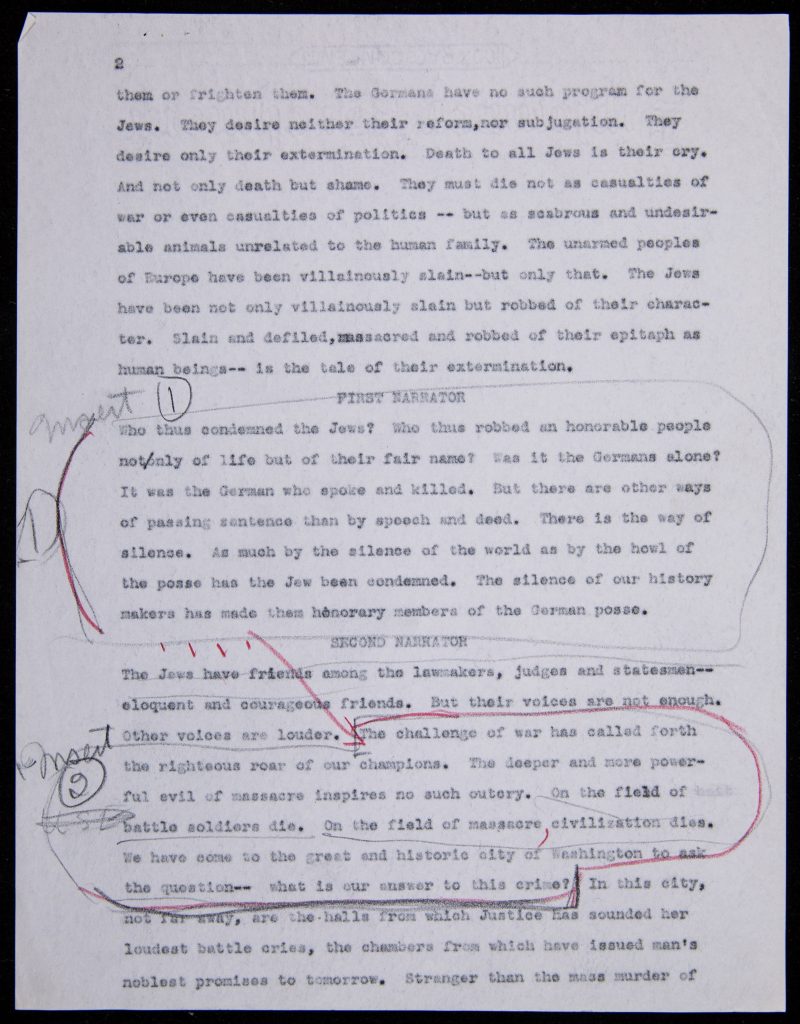

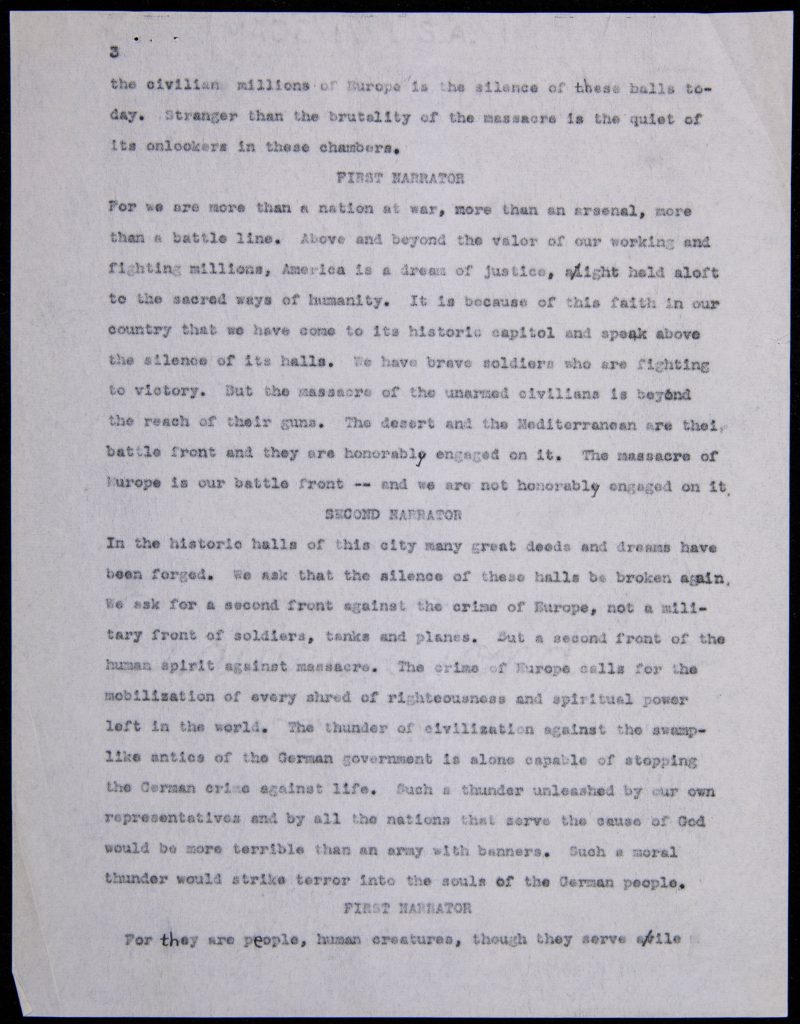

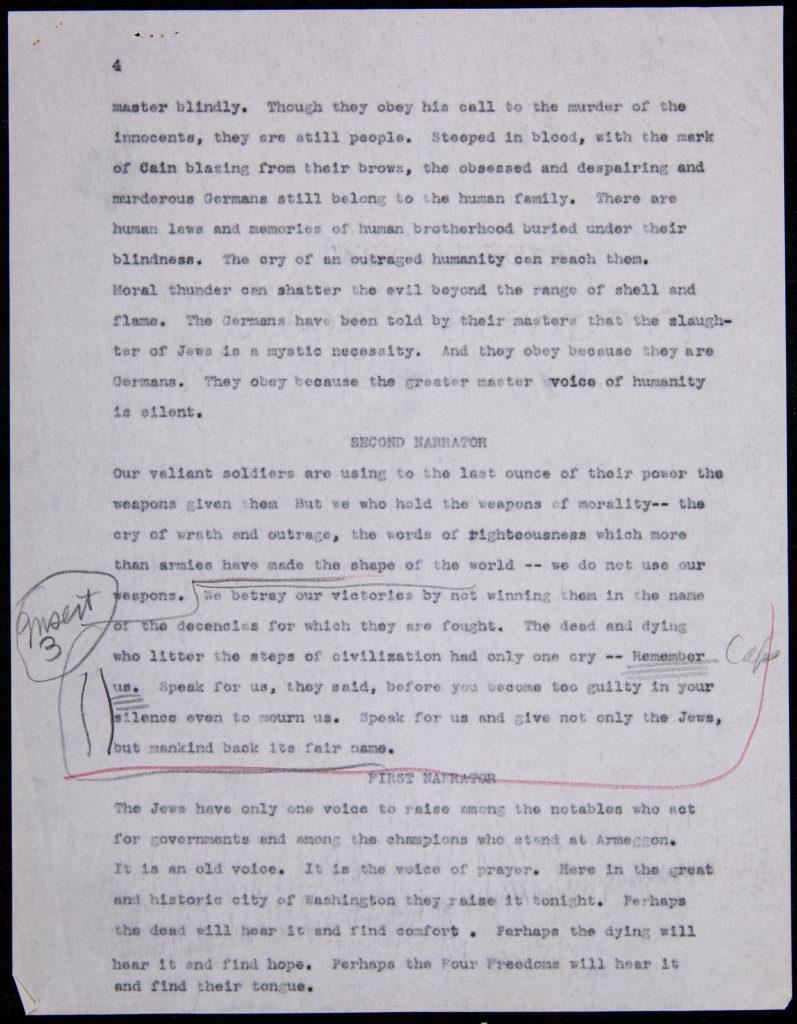

Selection: Ben Hecht, “Narrator’s Pitch” for “We Will Never Die” (1943)

Questions to consider:

- What images and symbols do you see in Arthur Szyk’s cover illustration for the “We Will Never Die” pageant? Which elements of the illustration that stand out?

- How does Hecht’s “Narrator’s Pitch” for the Washington, DC, performance of “We Will Never Die” confront the audience? How does Hecht try to persuade audience members to act?

War’s End

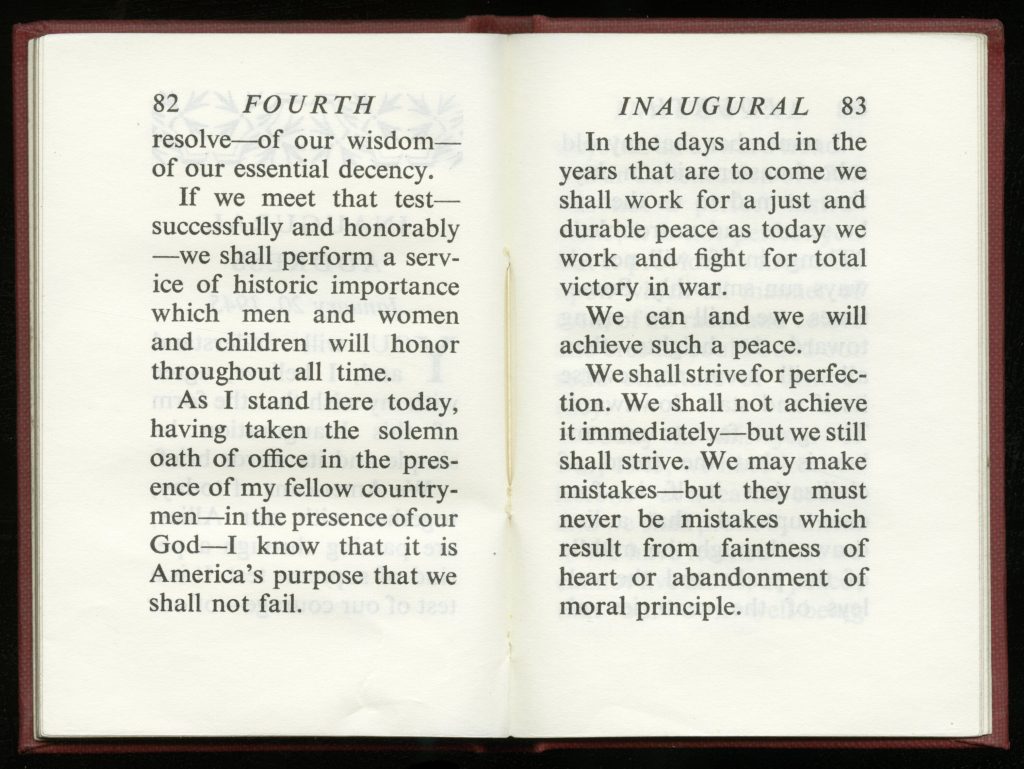

As the war neared its end in 1945, US government officials focused on how to shape the postwar world. In January, President Roosevelt delivered a very brief fourth inaugural address from the White House portico, rather than from the US Capitol, as is traditional for most inaugurations. FDR spoke of the “supreme test” that Americans had faced in war and hoped to impart lessons that could be drawn from the great sacrifices Americans had made in their fight against fascism. The President emphasized the new role of the United States in the world, telling Americans: “We have learned that we cannot live alone, at peace; that our own well-being is dependent on the well-being of other nations far away.”

Selection: Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Fourth Inaugural Address (1945)

One month later, FDR made an arduous trip to Yalta, where he met with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin to shape the coming postwar peace. Just two months later, on April 12, 1945, FDR died.

War in Europe ended with the defeat of Nazi Germany in May. The war against Japan ended in August, after the United States dropped atomic bombs on both Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Questions to consider:

- What was President Roosevelt’s message for Americans as the war drew to a close? Why might he emphasize these messages above all others in an inaugural address?

- What do you notice about President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill in the photograph of the two men at Yalta?

American responses to Hitler and Nazism

The selection of documents below demonstrates a range of responses – literary, personal, and organizational – to the rise of Hitler and Nazism from within the United States.

Americans and the European War

During the 1930s and ‘40s, the vast majority of Americans did not think of Nazism primarily as a threat to Europe’s Jews, as we do today. Most Americans thought of Nazism first as a threat to democratic nations and democratic values, rather than to Jews, and the United States ultimately mobilized 16 million troops to join the Allied effort in a war to save democracy.

“We will never die”

Ben Hecht’s pageant “We will never die” told the story of Jewish history and warned that all the Jews of Europe would be destroyed if no nation stepped in to stop Nazi Germany’s slaughter. This was one example of how American Jews responded to Nazi Germany, responses which included a range of perspectives and strategies.

Further Reading

Abzug, Robert H. America Views the Holocaust, 1933–1945: A Brief Documentary History. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 1999.

Breitman, Richard, and Alan M. Kraut. American Refugee Policy and European Jewry, 1933–1945. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987.

Breitman, Richard, and Allan J. Lichtman. FDR and the Jews. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2013.

Larsen, Erik. In the Garden of Beasts: Love, Terror, and an American Family in Hitler’s Berlin. New York: Crown, 2011.

Wyman, David S. Paper Walls: America and the Refugee Crisis, 1938–1941. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1968.