Introduction

Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), sixteenth President of the United States, was the subject of both promotional campaign songs and musical critiques. In this regard, Lincoln was similar to many presidents, who at the heights of their political careers have garnered composers’ interests. The posthumous Lincoln repertoire, however, has flourish to a degree that sets him apart from other chief executives. Founding fathers and early presidents have accumulated some volume of postmortem musical tributes. Musical nods to George Washington are good examples of this. Wartime presidents, such as Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt, have had their presidential tenures memorialized in songs. Other assassinated presidents, such as John Kennedy, have had performers and composers mourn them through music. Even still, it is music for and about Lincoln—be it in vernacular traditions, like bluegrass, blues, country, folk, hip hop, and rock and roll, or in cultivate traditions, like art songs, cantatas, operas, and symphonies—that accounts for more than a thousand compositions! Composers from Lincoln’s death in 1865 to the present have contributed new works that both reflect and contribute to American memory of Lincoln and his legacy. Looking and listening to a large swath of this music allows us to see aspects of his legacy that have remained foremost in our minds as well as those that have changed quite dramatically as years have passed. Before we look at examples of the Lincoln repertoire, we should consider music’s advantages and disadvantages as a medium for memorialization.

In many ways, music has profound shortcomings as a commemorative tool. Consider for a moment that a composer might write an elaborate Lincoln symphony, but that work might never find a home in the concert canon, or it might never even secure an initial performance. Canonical works, those compositions that are performed year in and year out over a long period of time, are the gold standard of cultivated music performers and audiences. Alternatively, think about how we praise many of the vernacular (popular) music genres for their ability to quickly change and keep pace with contemporary tastes. Thus, merely composing a Lincoln composition never guarantees its longevity. We can identify fascinating Lincoln operas that have seen single performances as well as highly successful Lincoln rock and roll songs from the 1960s that most twenty-first century audiences do not recognize. To this end, we might describe music as ephemeral: it rarely remains with performers and audiences for years, decades, or centuries. This reality of music performance, reception, and canonization tells us relatively little about Lincoln, but it is an aspect of music creation with which we must be aware if we are to use songs, symphonies, and other genres as sources for historical research.

If we compare musical tributes to physical memorials, like statues of famous people or buildings named in someone’s honor, then we might say that those physical bronze, marble, and steel commemorations—complete with their placement in public squares—remain present and visible to many more people, and over a much longer span of time than the musical works described above. To get to school each day, you might walk down a street named after Andrew Jackson or enter a building named for Franklin Roosevelt, but what percentage of days do you find yourself singing or listening to a song about these presidents? On the other hand, while we might encounter a myriad of buildings, streets, parks, and statues bearing commemorative names, plaques, and likenesses of historical figures, these physical memorials rarely demand our time and attention. Does anyone force you to spend several minutes reflecting on any of the historical people you encounter in street names or building dedications? These physical tributes are so ubiquitous that we often walk past them and pay little, if any, attention. In some instances, a physical memorial that we might consider to be appropriate at one time, may either fall into disrepair or, decades later, we may wish to remove it entirely.

While the physical monuments may appear much more permanent, musical monuments offer a different type of staying power! Music as an artistic medium consumes time. Music’s temporal reality means that unlike a statue, which we can walk past in a matter of seconds, performances often require us to provide our attention for an extended period. That time and focus on a single subject is a potent benefit of musical memorialization. Take for example that you are watching a hip hop musical about U.S. Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. While you are in that theater, you are likely going to spend some sizable portion of that time contemplating the subject. How many Americans have walked past a street, building, or statue for Hamilton and paid absolutely no attention to it? Yet when we find ourselves watching Lin Manuel Miranda’s musical Hamilton, we spent the evening enveloped in his life and legacy. Music might be ephemeral, but when it is performed, it can control attention of large audiences in powerful ways.

A final factor to keep in mind is that musical works require performers who can convert notes, words, ideas, or concepts into sounds that occur in a specific time and place. Because of this, these compositions provide constant invitations for revision and reconceptualization. Consider just how different of a sound and experience it would be if on your birthday one friend sang you a solo rendition of “Happy Birthday,” versus if a huge gathering of your entire extended family and friends sang the same song, or if your favorite singer heard that it was your birthday and showed up to offer a surprise serenade. The composers and performers who have contributed music about Abraham Lincoln have not merely added one work to the repertoire; rather, they have invited endless opportunities for ritual memorialization. They have also opened valuable windows through which we can see American ideas about Lincoln and his legacy at different times and places. Music is a fruitful historical source through which to track how U.S. populations have come to understand Lincoln from his death in 1865 to the present.

Essential Questions:

- Do you know any music that mentions Lincoln? If so, what is the musical genre (a bluegrass tune, pop song, musical, symphony, opera, etc.)? If not, do you have any assumptions about what we may find, see, and hear in this repertoire? Will there be texts (lyrics)? If so, what might the texts contain? Will the instrumental parts attempt to convey that this is music about a president or simply mirror musical tastes of their time?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of using music to commemorate a person or event?

- Of all of the U.S. presidents, why do you suspect that Lincoln has amassed the largest musical repertoire?

- What changes do you suspect we will find in the Lincoln musical repertoire over the past 150 years?

Death & Mourning in 1865

Lincoln’s death in office, coming on the heels of the Confederate surrender, and at the hands of assassin John Wilkes Booth, initiated a lengthy sequence of mourning rituals in which both music and the purposeful lack thereof were key experiences. Music from 1865 provides an essential starting place for understanding Lincoln’s long-term memorialization, since the early compositions and performances established some of the models for the role that music could play in subsequent decades of commemoration.

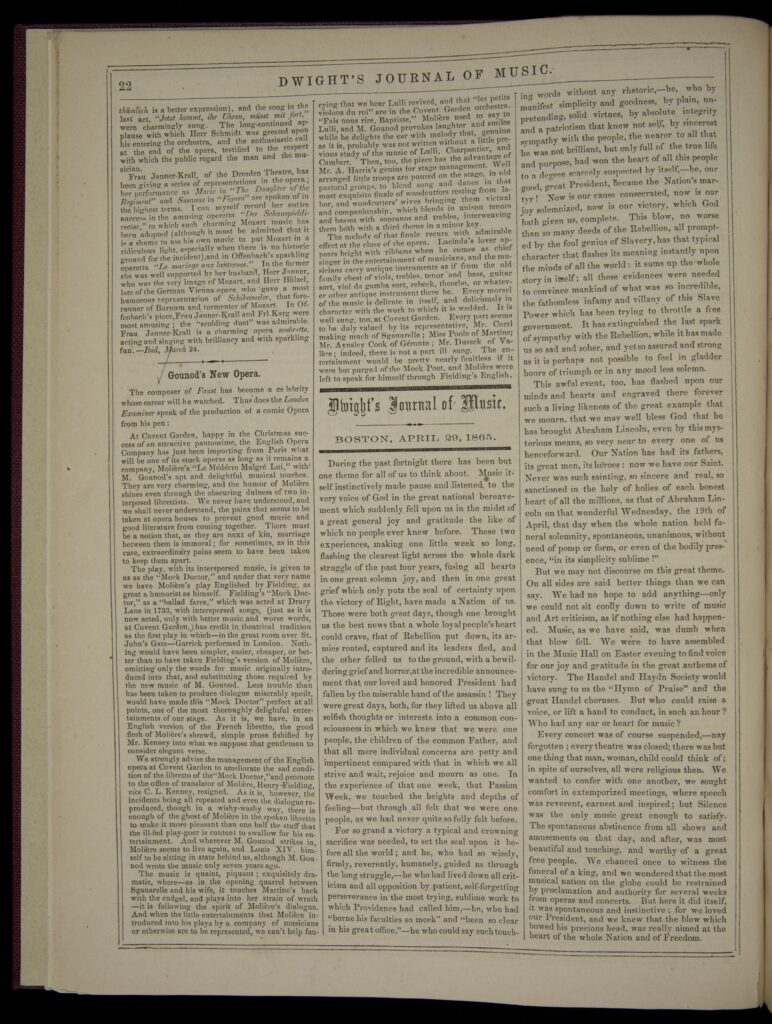

Since so many Americans commented on Lincoln’s death and funeral, we have many sources that tell us about military bands playing slow, somber marches. The popular nineteenth-century music periodical edited by John Sullivan Dwight is one such source for how musicians responded to the assassination. Dwight’s tribute to Lincoln, as you can see here, was unusual for a newspaper that was devoted to the critical analysis of new compositions, premiere performances, and the like. The experience that Dwight documented was one of silence. His beloved concert halls and opera houses halted performances as news spread of Lincoln’s death. That Dwight drew attention to just how quiet concert spaces became in the weeks following the death stands in contrast with experiences at venues in which musical production went into commemorative overdrive.

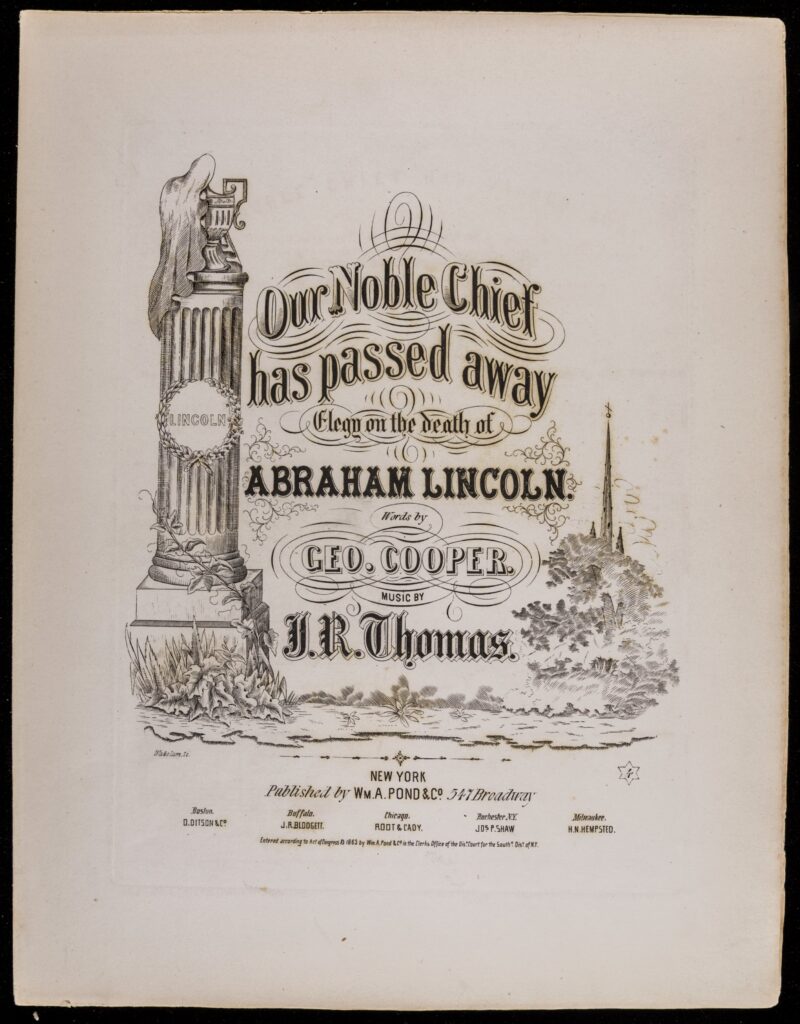

Selection: J. R. Thomas and George Cooper, Our Noble Chief has Passed Away (New York: William A. Pond, 1865).

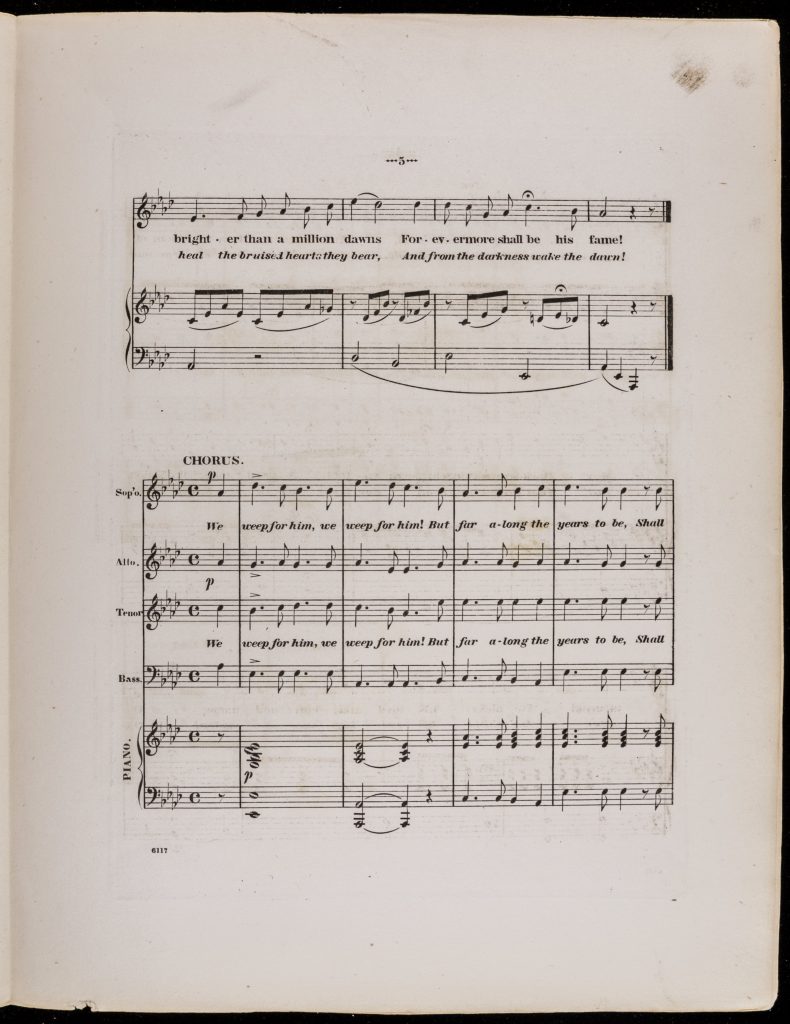

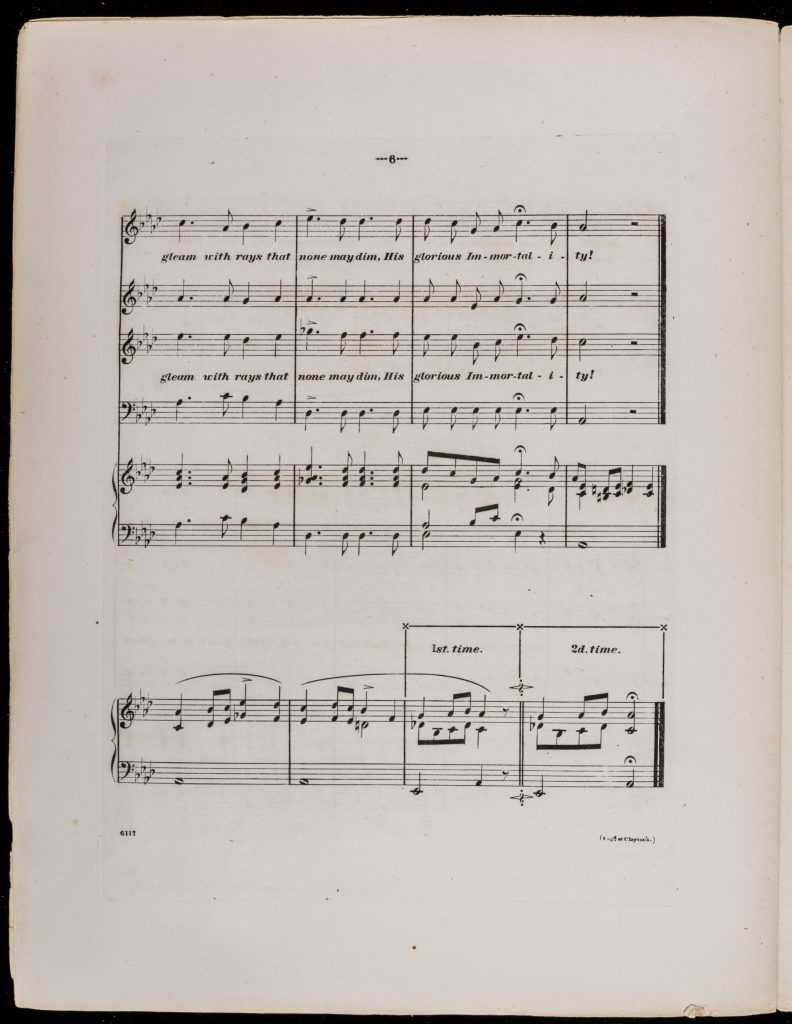

The cover is a memorial image with a column draped in mourning. The distant steeple in the country scene implies that the death was felt in every corner of the nation. The verses are for a single voice, while the refrain provides for a four-part chorus.

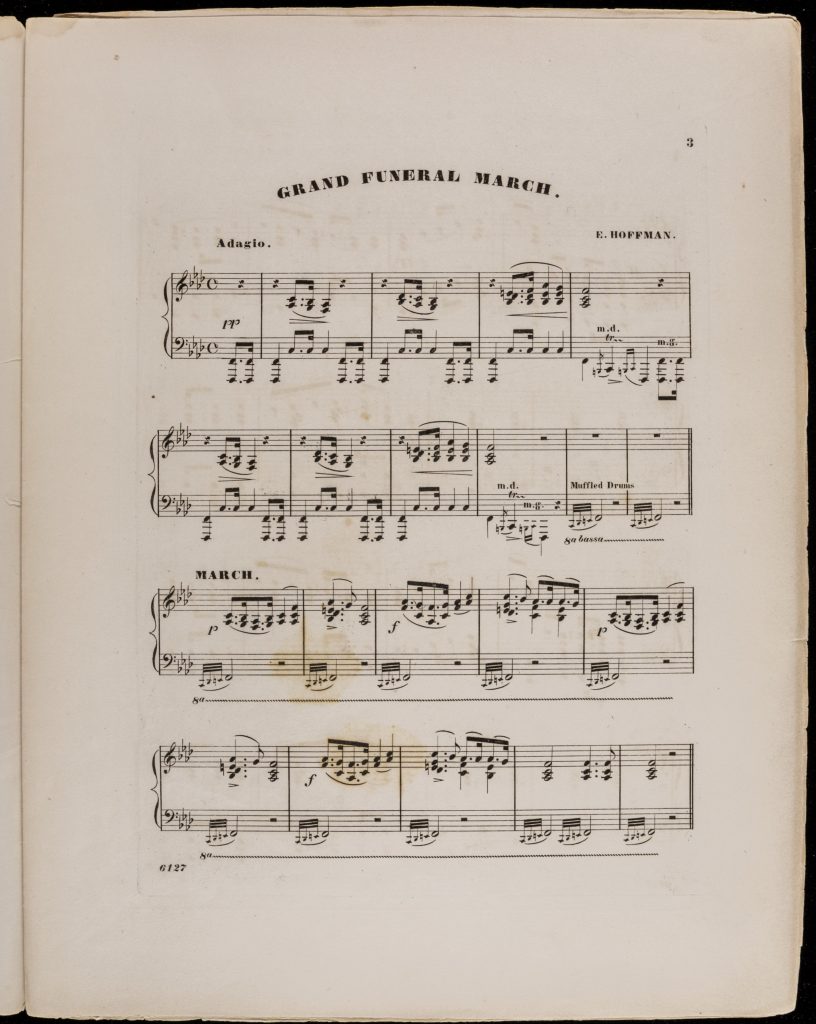

Lincoln was shot on Good Friday and expired on Holy Saturday morning, so most Americans were already busy preparing for an Easter Sunday that was set to take on added meaning—the first large, religious feast to follow the four long and bloody years of the Civil War. This was not only to be a weekend of Christian rejoicing, but one with the added celebration of a national resurrection. Thus, Lincoln’s assassination led church communities to focus intensely on what preachers and commentators of the day described as a national crucifixion. The connection of the sacrificial deaths of Jesus and Lincoln moved swiftly from the pulpits to the choir lofts. Church choirs as well as the choirs associated with social and fraternal organizations quickly mobilized to sing at special, local services and at both the formal stops of Lincoln’s funeral train as well as in ad hoc gatherings alongside the train tracks as the locomotive slowly passed. Along that funeral route other sounds melded with the choirs: church bells tolled, minute guns fired, and drummers performed rolls on their muffled drums.

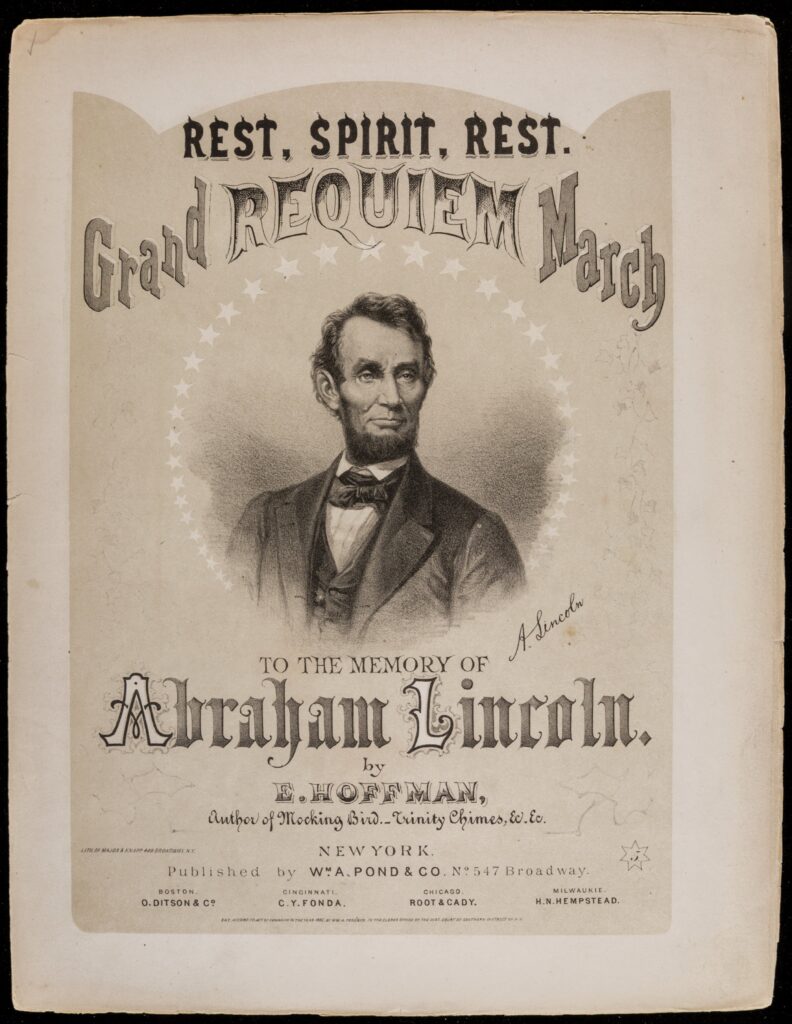

Selection: E. Hoffman, Rest, Spirit Rest. Grand Requiem March (New York: William A. Pond, 1865).

The cover features a bust and a Lincoln signature. Lincoln did not sign autographs from the grave! This addition provides a sense of nearness to the president. The “March” features a gesture in the pianist’s left hand to mimic a muffled snare drum.

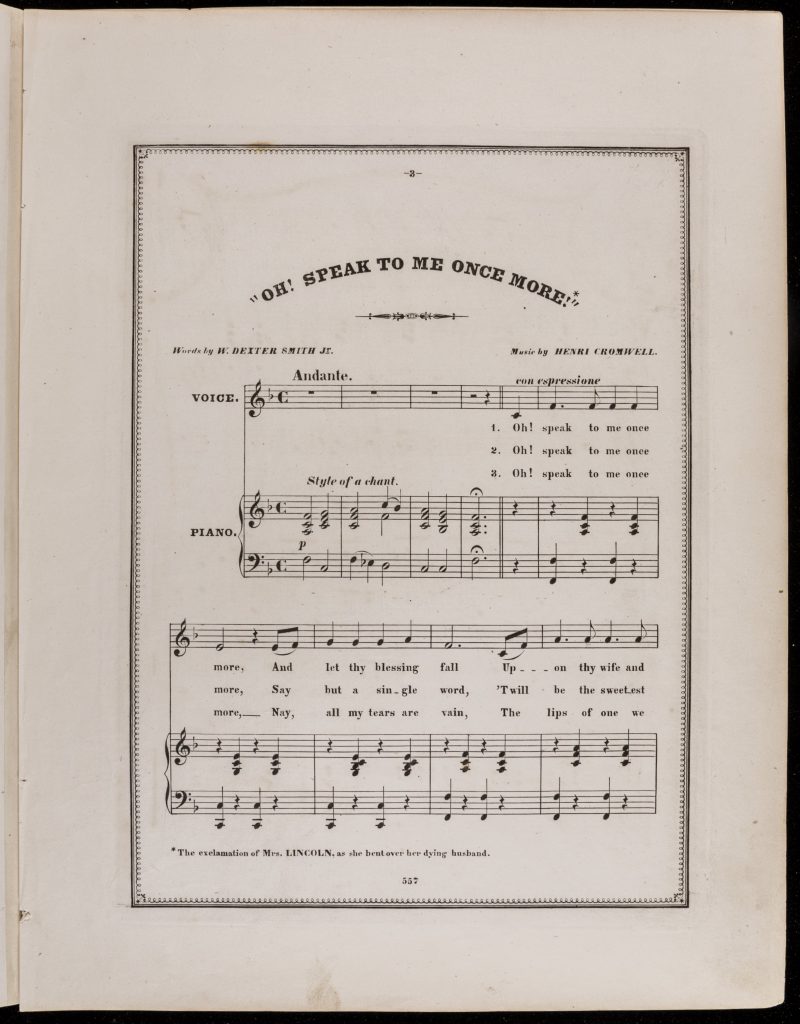

These public displays had a counterpoint in private settings, specifically in home music making. The composition, publication, and purchase of sheet music was a robust industry in the mid-nineteenth century. Home music making was a popular activity for many American families. As we will see, this is not to say that all or even most Americans were professional-quality musicians. To the contrary, the sheet music industry catered to performers with modest skills. Composers crafted tuneful, but simple odes. They were for either solo piano or piano with voice. When lyrics were provided, they often had a single musical line that could be sung either by a solo singer or by all of the singers performing in unison. Then for the refrains, the parts would often break into four-part hymn-like settings. While this type of home entertainment may seem so distant from our current practices, we should attempt to grasp what it may have felt like for a whole family to gather in the evening and sing together as they remembered and mourned their late president. Perhaps one of the older children played the piano accompaniment while another sang the solo verses, but then the whole family joined in and sang the four-part refrains, with the father singing bass, mother singing alto, and the other children rounding out the soprano and tenor parts.

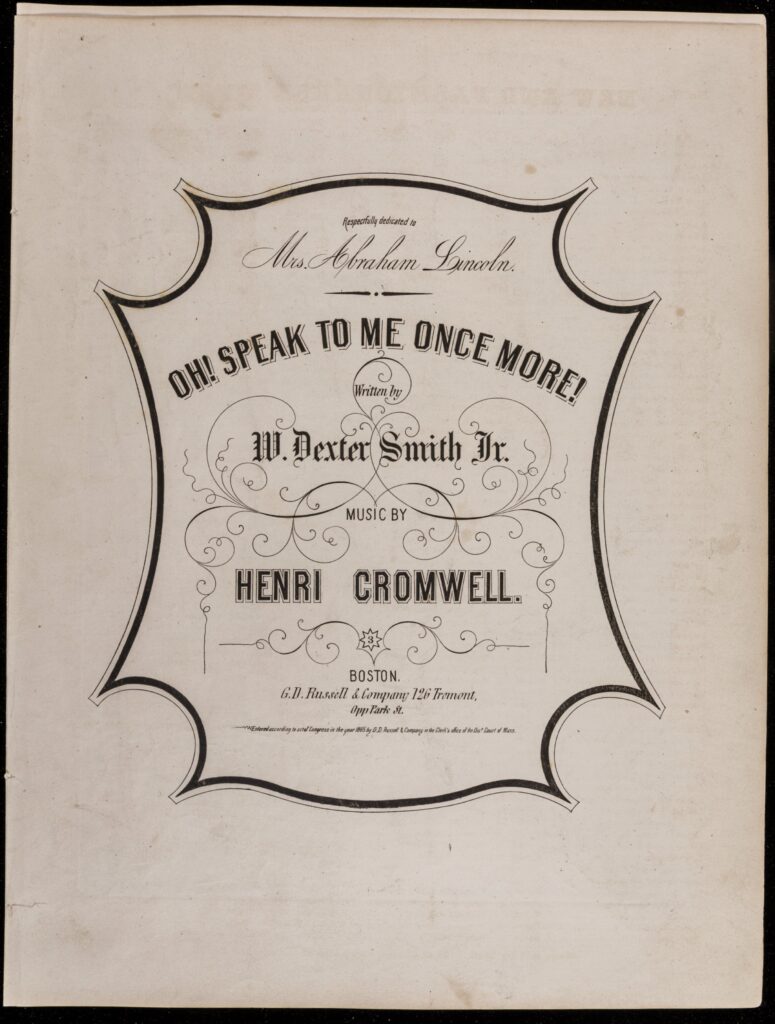

Selection: Henri Cromwell and W. Dexter Smith Jr., Oh! Speak to Me Once More! (Boston: G. D. Russell,1865).

In this song, the cover includes a dedication to the widow, Mrs. Abraham Lincoln, and the first page has a note that the lyric is based on reports of the First Lady’s final words to her husband.

Beyond the practicalities of musical performance, this type of singing—involving a whole family in home music making—had the ability to be its own type of ritual for commemorating the dead. A family could end their day singing some favorite songs including a solemn nod to the late president. This notion of home ritual extends to the elaborate cover art of this sheet music. Dramatic covers were important forms of nineteenth-century marketing. As one paged through new sheet music, they might not sing every melody in their mind, or at least not hear a piece of music with all of its parts, but they could see a vignette on the cover and make a purchase based on a certain connection to that image. Once the sheet music was in the home, however, then that elaborate cover would sit on the piano’s music stand as a visual tribute to the late president, when the family’s performance was not underway. These sheet music publications were combined visual and aural tributes.

Questions:

- Dwight speaks of music falling silent at a time when we know many families and church choirs were singing a lot of music about Lincoln. What does his commentary tell us about where he was looking for music and his musical tastes?

- In reading the lyrics of “Our Noble Chief Has Passed Away,” can you find passages that might have helped families who had already lost sons, brothers, husbands, or fathers in the war to connect their grief to the news of Lincoln’s death?

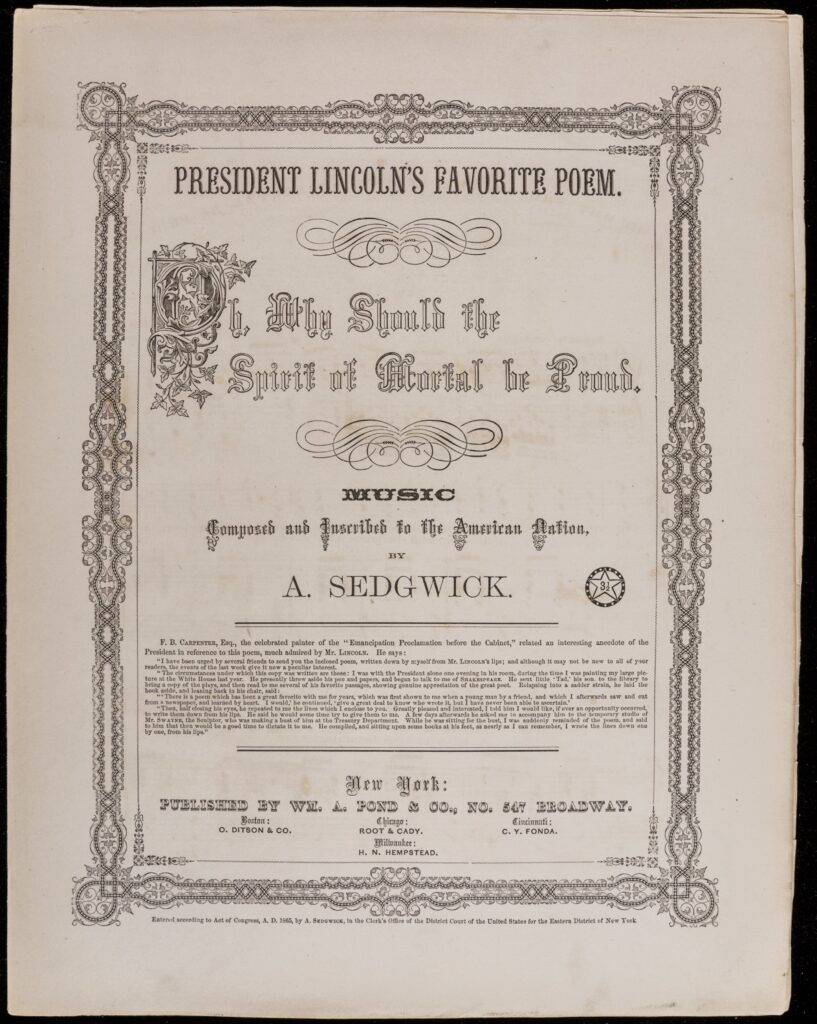

- Think about the various additions to the covers of the songs by Hoffman, Cromwell, and Sedgwick. Which of their techniques to help audiences connect with their songs seem most valuable? Can you think of ways that we attempt to help people connect with music today?

Lincoln at 100

The 1909 centennial of Lincoln’s birth was an occasion for a national reassessment of the sixteenth president. It was a moment in American life sandwiched between the Reconstruction and late nineteenth-century economic turmoil, on one hand, and on the other hand, a desire to take account for the aftermath of the Civil War with the approaching fiftieth anniversary of that conflict. Throughout the closing decades of one century and opening decades of the next, America’s domestic politics faced challenges as waves of European immigrants arrived. Native-born citizens accepted some communities, but many more faced profound discrimination. Simultaneously, there was heightened racial bigotry directed at African Americans, with cycles of extreme violence, such as lynchings and beatings.

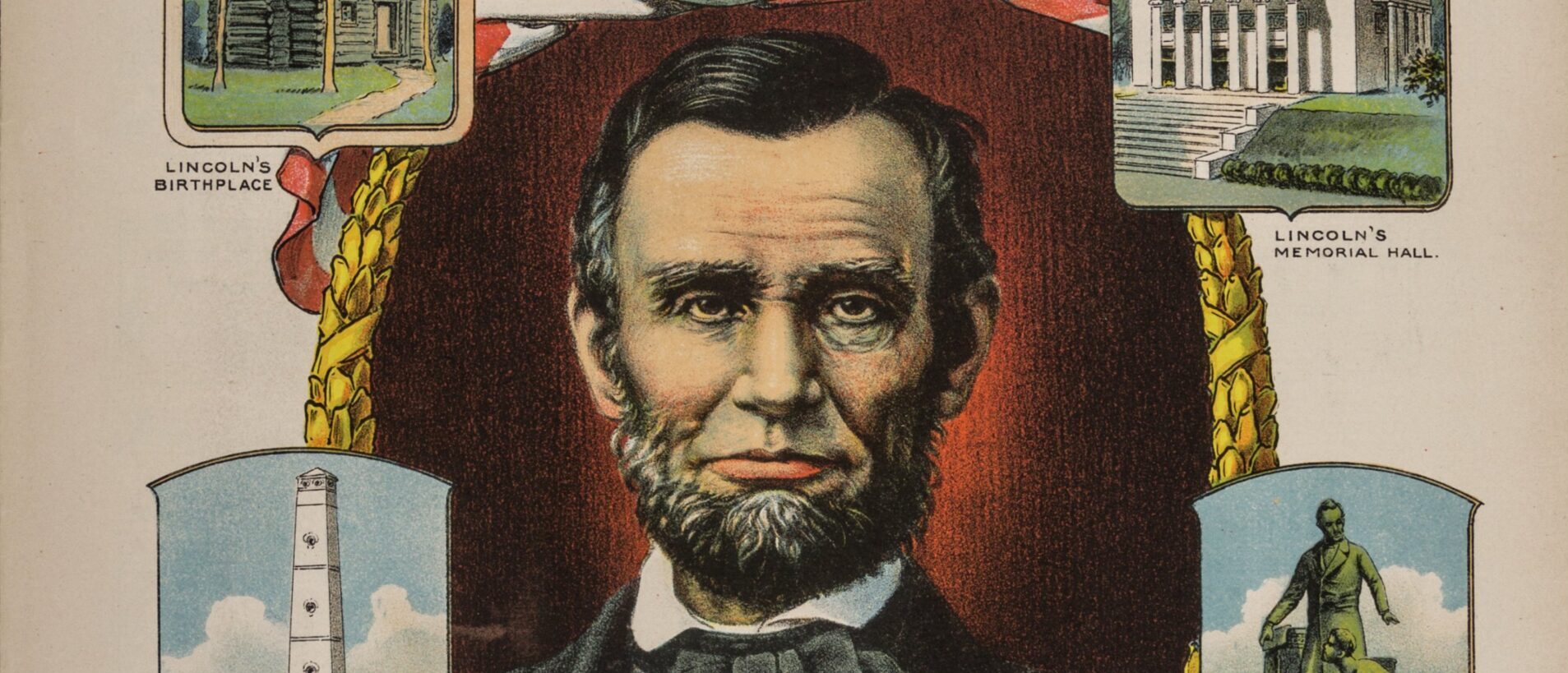

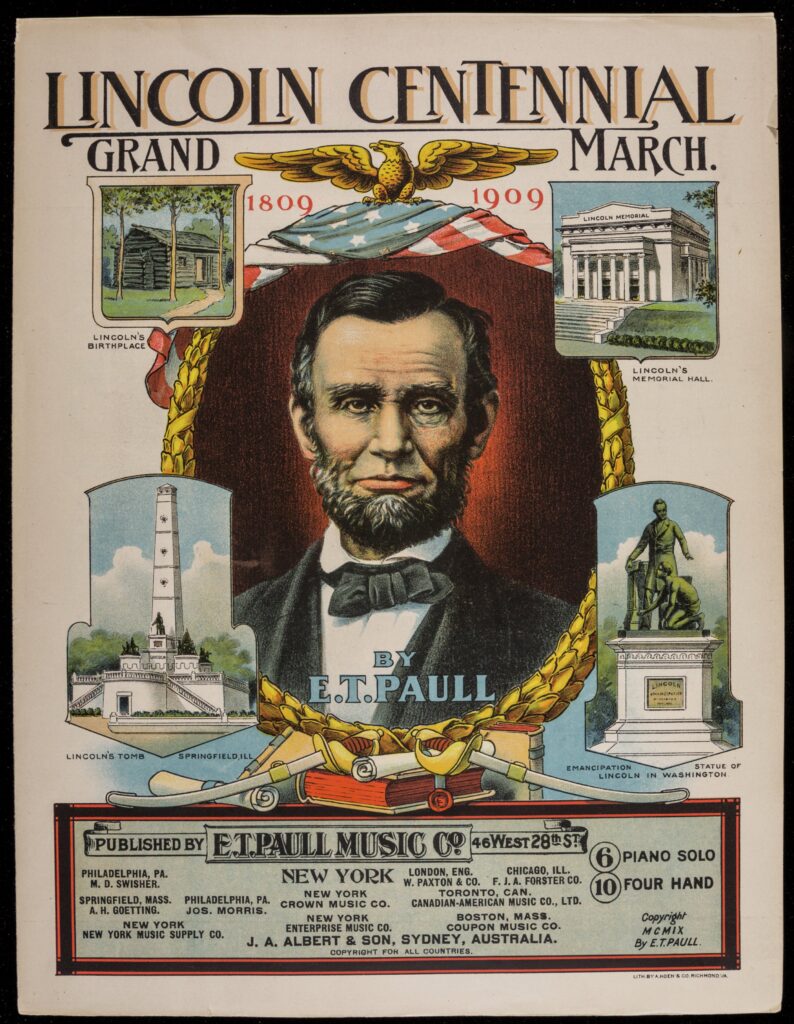

While the 1865 funerary music for Lincoln emphasized his noble, almost religious, status as a national redeemer, composers and publishers of 1909 centennial works emphasized Lincoln’s relationship to broader national tropes. For example, Lincoln’s boyhood poverty became an important point to emphasize. The up-from-the bottom stories were both shared with and embraced by native-born and immigrants, alike. Mentions of his childhood, dirt-floored log cabin and humble work splitting fence rails grew in their frequency. Many heralded that Lincoln provided Americans with a model of ascending from poverty to the presidency.

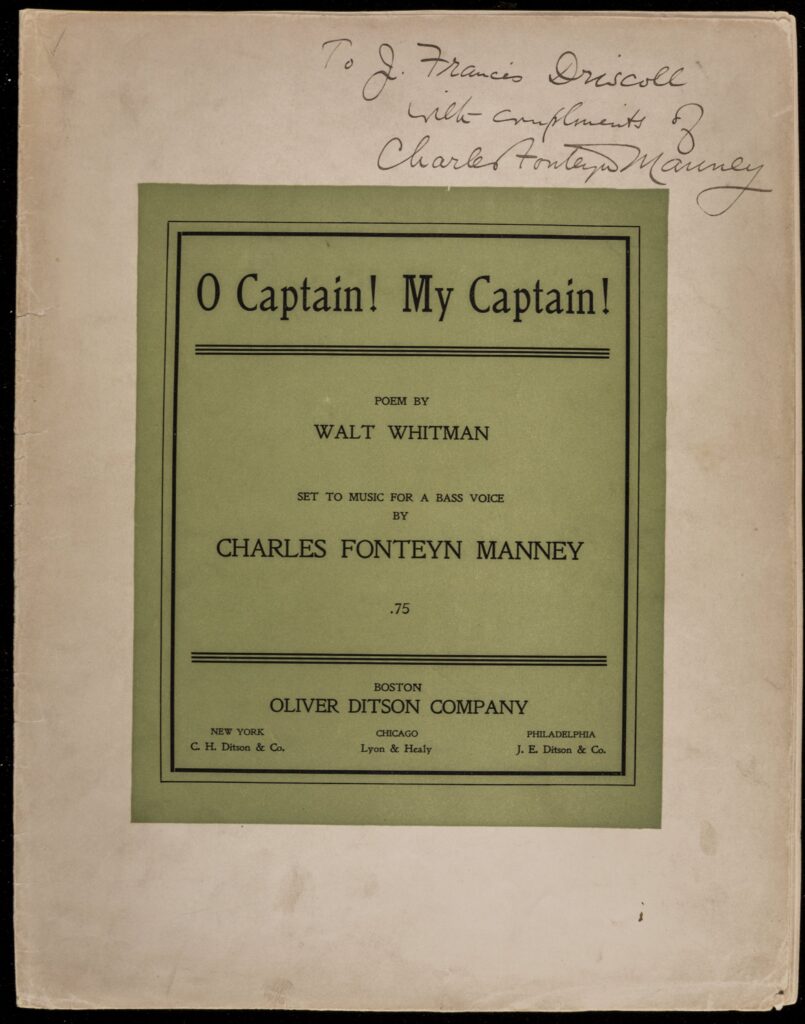

The other source for texts to the turn-of-the-century works were the growing body of poetry and prose that were either newly written or recently reprinted to burnish Lincoln’s legacy. In particular, composers frequently turned to Walt Whitman’s Lincoln poems when they were seeking words to place Lincoln as part of the nation’s story. Even when Whitman provides Lincoln a lofty treatment, as in his most recognized Lincoln poem, “O Captain! My Captain!” the poetry does not present the deity common to texts from fifty years earlier, but a sailor steering the ship of state through turbulent wars. This image of Lincoln was another way to emphasize prudent and altruistic governance.

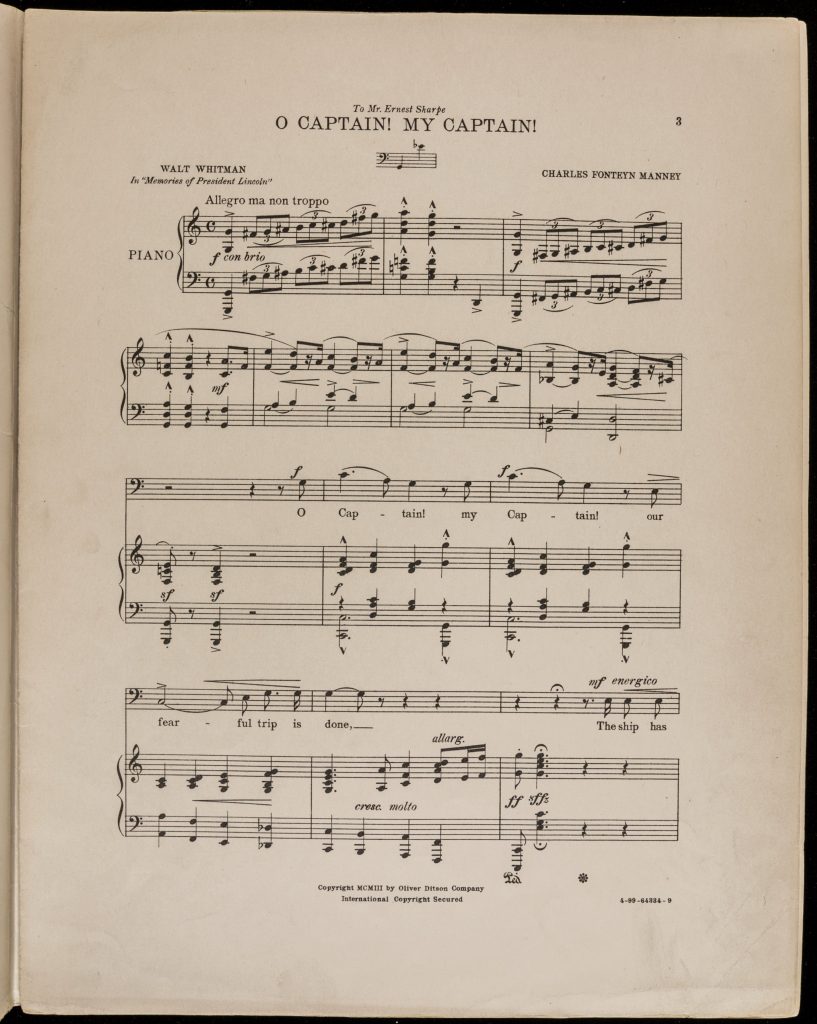

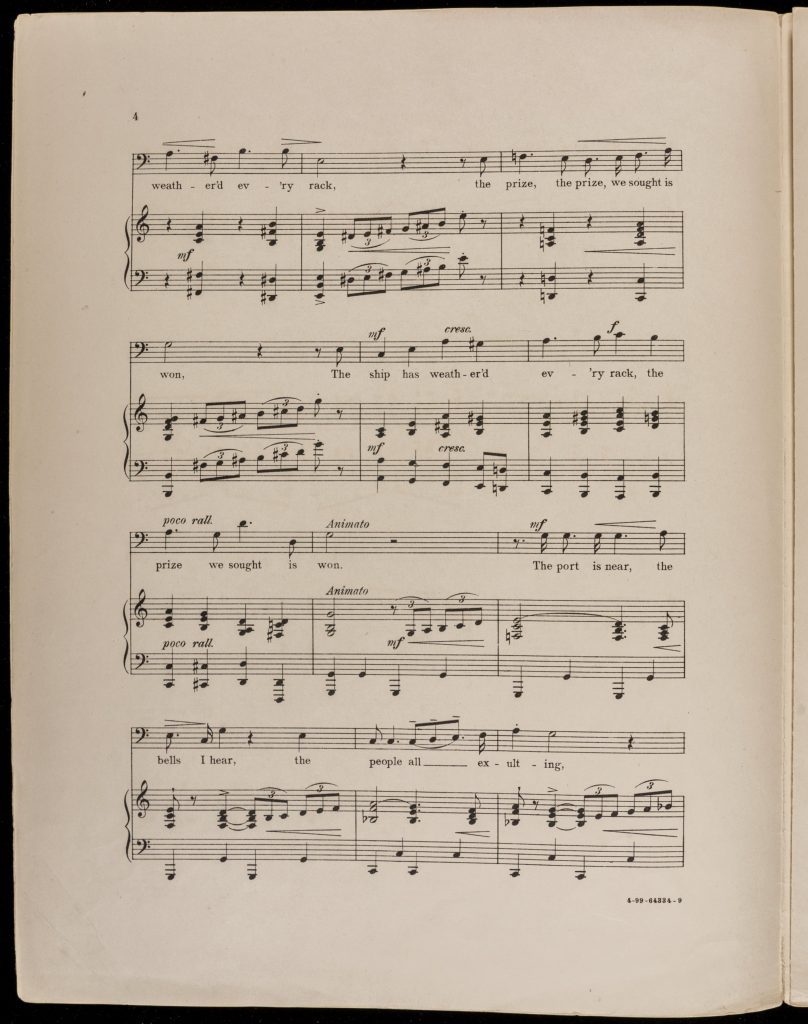

Selection: Charles Fonteyn Manney and Walt Whitman, O Captain! My Captain! (Boston: Oliver Ditson, 1903).

Consider the rhythm of Whitman’s poem and then look closely at how Manney sets it to music. The composer keeps some of the poet’s rhythm, but amends other moments and elects to repeat some passages for the purposes of the musical product.

Questions:

- There are many reasons why Americans in the early twentieth century remembered Lincoln in very different ways from how he was initially commemorated in 1865. What threads of Lincoln’s identity are presented on the cover of the “Lincoln Centennial Grand March?”

- Please consider what factors and issues a composer might need to address when setting a pre-existing poem versus composing his/her own new lyrics. Consider “O Captain! My Captain!” and identify some of the benefits and challenges of working with a recognizable or famous poem as the basis for a new song.

The Popular Front Claims Lincoln

In the instances described above, composers were merely emphasizing different points in Lincoln’s biography or finding different artistic (poetic) languages to pair with different musical languages. However, as Lincoln came to symbolize a universally honest broker in American political life, more composers attempted to ask questions along the lines of “What would Lincoln do?”

Composers who seek to advance a political or ideological message can offer something of a logical proof: if Americans embrace Lincoln, and I believe that Lincoln would have supported my policy proposals, then Americans should also embrace my agenda. In some ways this use of Lincoln to advance causes was present throughout Reconstruction. Historians describe this use of the dead to justify actions of the living as “bloody shirt politics.” In more distant ways than what we might recognize as exclusively Civil War issues or topics, a collection of artists who embraced Lincoln in order to espouse various socialist, communist, or radical leftist beliefs, in the 1930s and 1940s, can be described as members of the “Popular Front.”

Composers in this movement often attempted to draw Lincoln into their corner. Aware that some might be skeptical to think of Lincoln as a Popular Front champion, they were sensitive to use Lincoln’s own words, albeit in selective and decontextualized ways, to make their cases for what they saw as his likely affinity for their ideology.

Composers Earl Robinson and Aaron Copland adopted this approach. Their musical results, however, are strikingly different. Robinson (along with his collaborator on adapting the text, Alfred Hayes) hid very little of his feeling that Lincoln was an all-out political revolutionary. In his Lincoln tributes, Robinson used Lincolnian language in a way to make the late president sound as if he is specifically thinking about twentieth-century battles between democracy and communism.

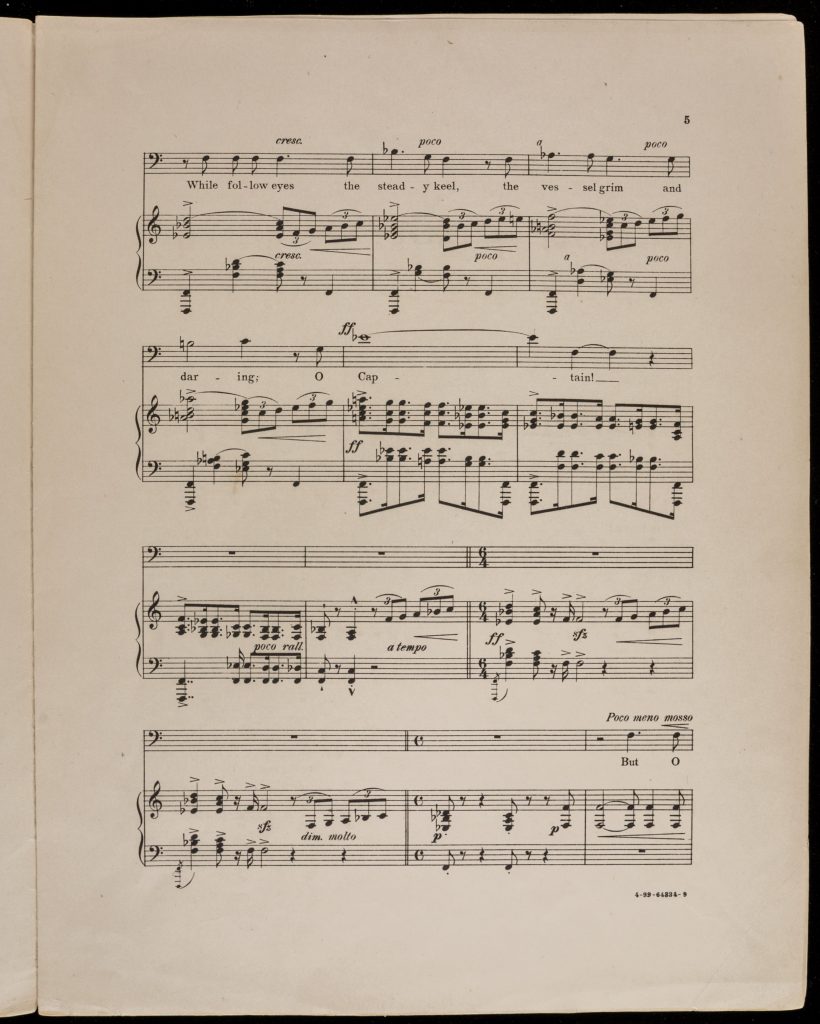

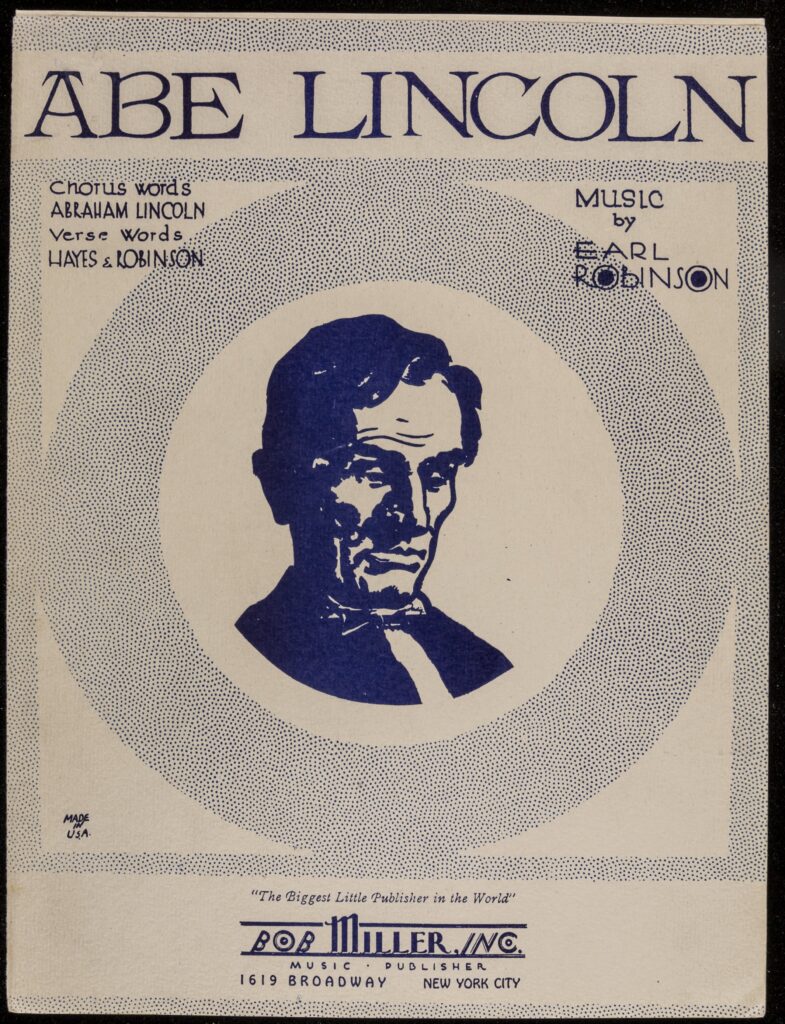

Selection: Earl Robinson and Alfred Hayes, Abe Lincoln (New York: Bob Miller, 1938)

In his refrain, Robinson embraces Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address for the overthrow of tyranny. In the hands of one of America’s most consistent Popular Front voices, this refrain casts a view of the need for a proletariat revolution.

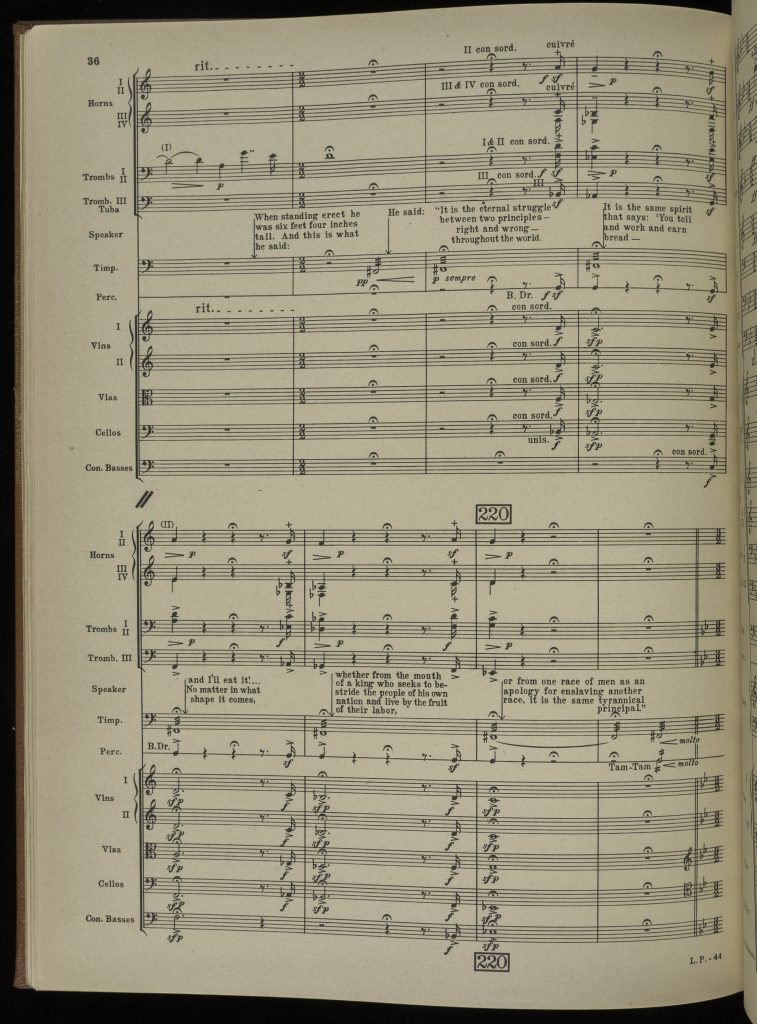

Copland, on the other hand, was far more subtle in his treatment of Lincoln’s words. While he drew attention to ideas that were in keeping with the Popular Front, he also presented the president in heroic terms. This is true in both his text and open and soring musical accompaniment. The musical content and veiled approach of Copland explains why his Lincoln tribute is one of the very few pieces in the overall Lincoln memorial repertoire to have secured a place in the contemporary concert canon. Orchestras (often joined by celebrity narrators) perform A Lincoln Portrait at many national concerts, and it is unlikely that performers or audiences in the twenty-first century hear this music and consider themselves complicit in some form of subversive statement. Quite to the contrary, most audiences hear the work, complete with excerpts from Lincoln’s speeches, as highly patriotic.

Selection: Aaron Copland, Lincoln Portrait (New York: Boosey & Hawkes, 1942).

Copland merged multiple Lincoln texts to craft the spoken content for this work. We find his Popular Front ideology in his dramatic emphasis of passages like, “It is the same spirit that says: ‘You toil and work and earn bread and I’ll eat it.’”

Questions:

- After looking at these two texts, please identify the statements that Robinson and Copland selected to portray Lincoln as sympathetic to the proletariat.

- Does adapting a politician’s language provide a valuable artistic, social, or political exercise? Does it presents specific problems or challenges?

- Do you think contemporary audiences would reject a work like Copland’s “Lincoln Portrait” if they enjoyed the way the music sounded, but opposed the composer’s politics?

Lincoln Goes to War, Again

Part of the Lincoln legacy that composers have emphasized in a particular way, at certain moments, is his role as a commander-in-chief. He was, after all, the leader of the Union forces and was heavily involved in discussions with his generals as they planned and executed the difficult Civil War victory.

That said, thinking of Lincoln as a saintly figure, emancipator, or poor boy from a log cabin is quite different from describing him as a great military commander. Both of the World Wars encouraged even more composers to pay attention to Lincoln as a musical topic. Tracking the volume of compositions about Lincoln produced during the wartime years, shows us just how many composers turned to Lincoln as they wanted to present patriotic topics.

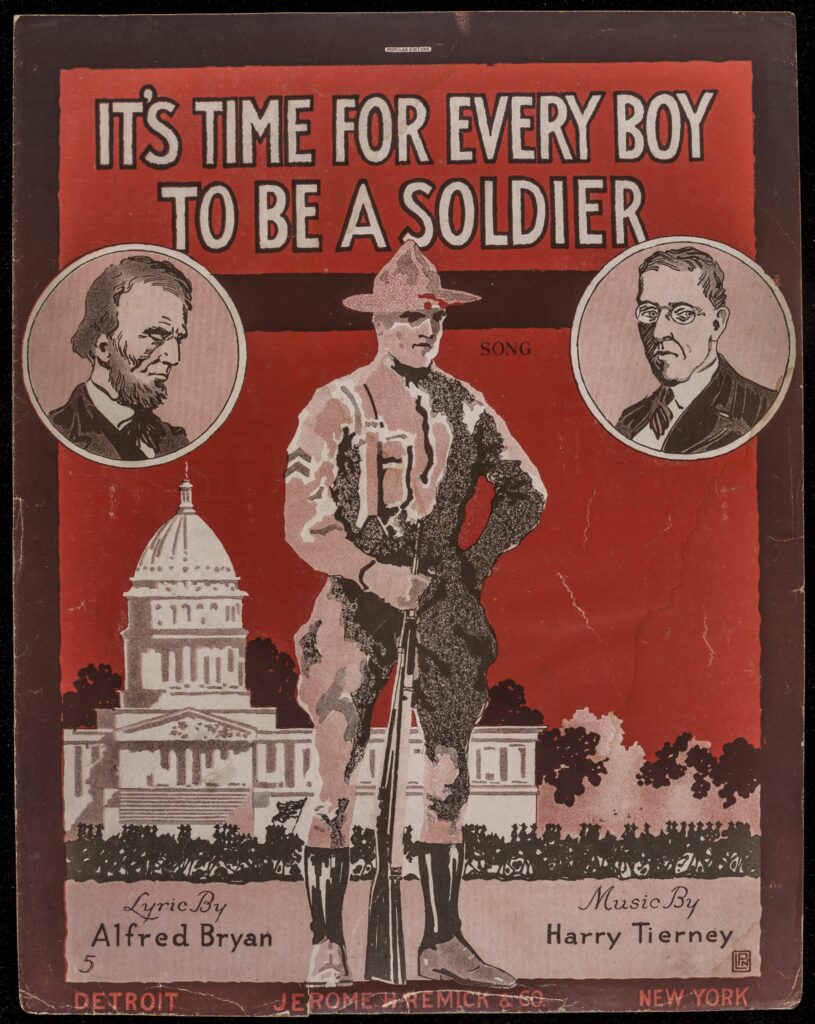

Lincoln was used as the model for the twentieth-century presidents as well as for the soldiers. This type of duality—Lincoln the model for us all, leaders and soldiers, alike—was on display in this example from Harry Tierney and Alfred Bryan. The composer and lyricist team presented Lincoln as the model for Woodrow Wilson on the composition’s cover and then in the lyrics, they tell soldiers to remember Lincoln’s encouraging words to the nation.

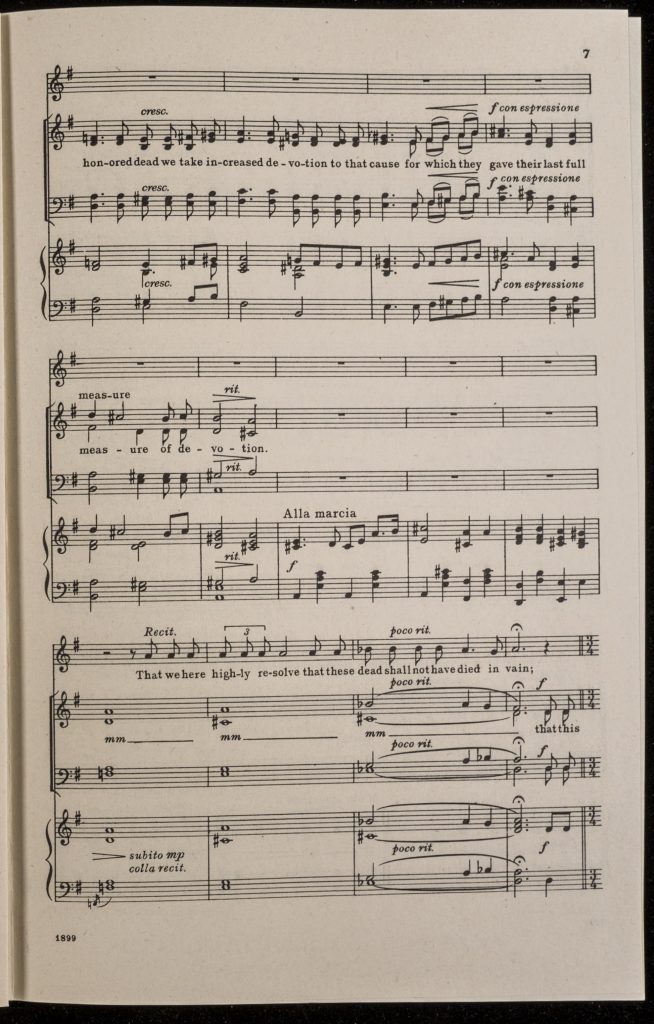

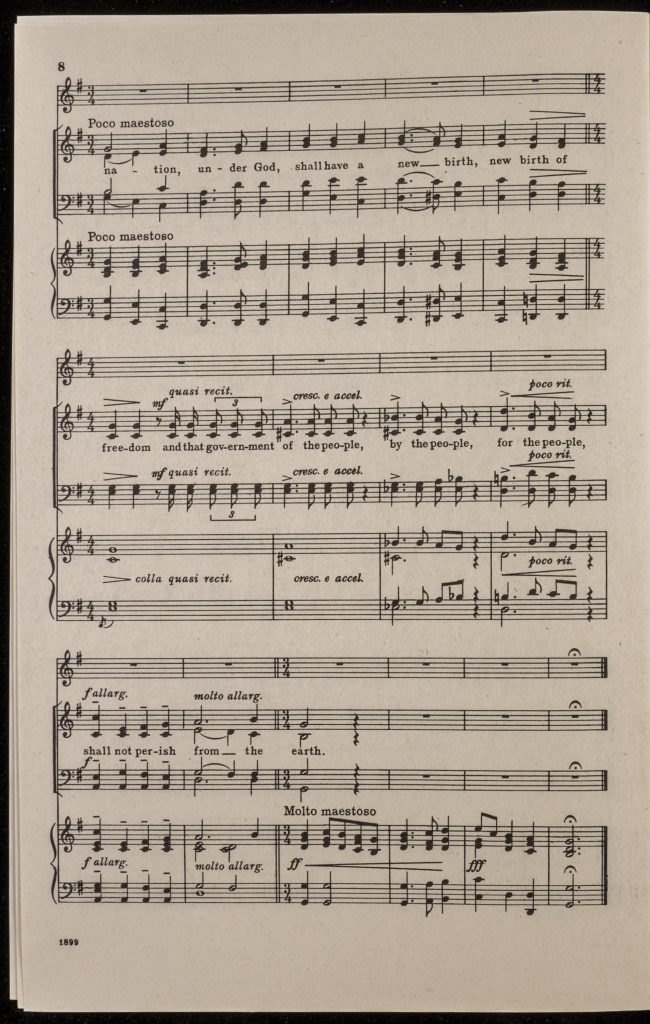

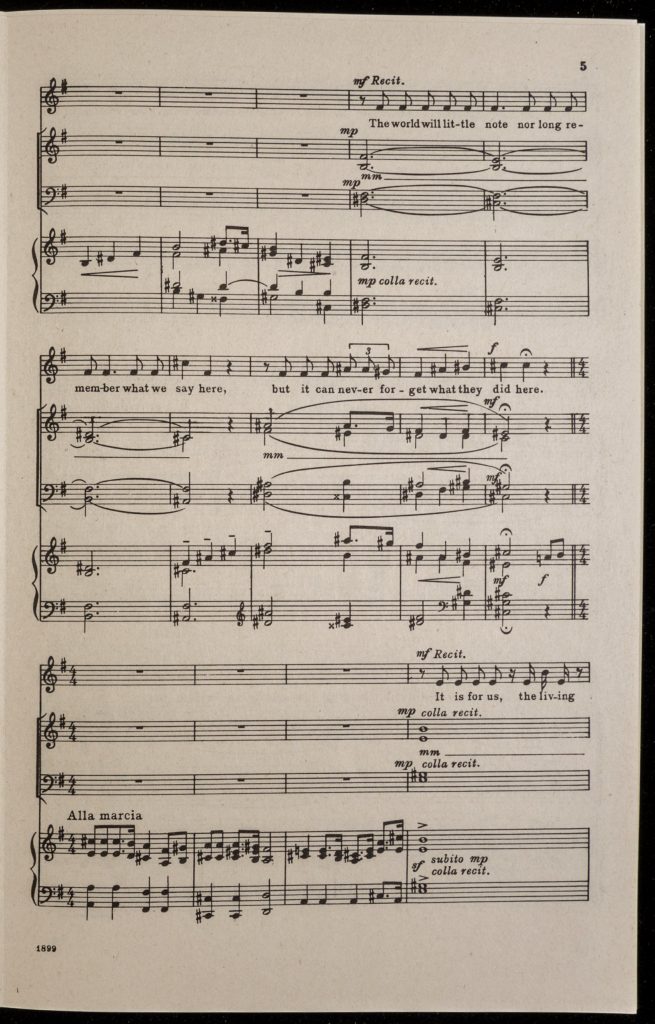

Other wartime connections to Lincoln were less overt—they did not have lines about Lincoln teaching us a lesson—but the implication to draw on the spirit of Lincoln and his ideals was nonetheless clear. Henry Hadley, for instance, is one of many composers who thought the loss of life in the Second World War might lead to something of a second Gettysburg, a new battlefield consecrated by the blood of soldiers. He employed a text-setting device to make it clear that he was not merely presenting us with Lincoln’s speech as some sort of historical relic, but was adapting it to the current moment. In the speech’s dramatic conclusion, Hadley has the soloist—the figure who the audience understands to be singing in Lincoln’s place—drop out and the chorus then steps in to sing the concluding phrase: “A new birth of freedom ….” Indeed, Hadley reminds Americans that in accepting the charge Lincoln provided, we must all step up to the battlefields of our day.

Selection: Henry Hadley, Gettysburg Address (Boston: C. C. Birchard, 1941).

This composition for vocal soloist, four-part choir, and piano has the soloist’s voice (Lincoln) end on “shall not have died in vain,” while the choir (the citizenry) sings the concluding “new birth of freedom” rhetorical flourish.

Questions:

- In looking at the image on “It’s Time for Every Boy to Be a Soldier” please consider why the composer, lyricist, and their publisher specifically compared Wilson and Lincoln.

- The Gettysburg Address is one of the more repeated U.S. presidential speeches. We encounter it in many places. Why is Hadley’s division between the parts sung by Lincoln and the parts sung by everyone else a compelling action?

- What other reasons might Hadley have had for removing some words from Lincoln’s mouth and providing them to the choir?

Lincoln since the World Wars

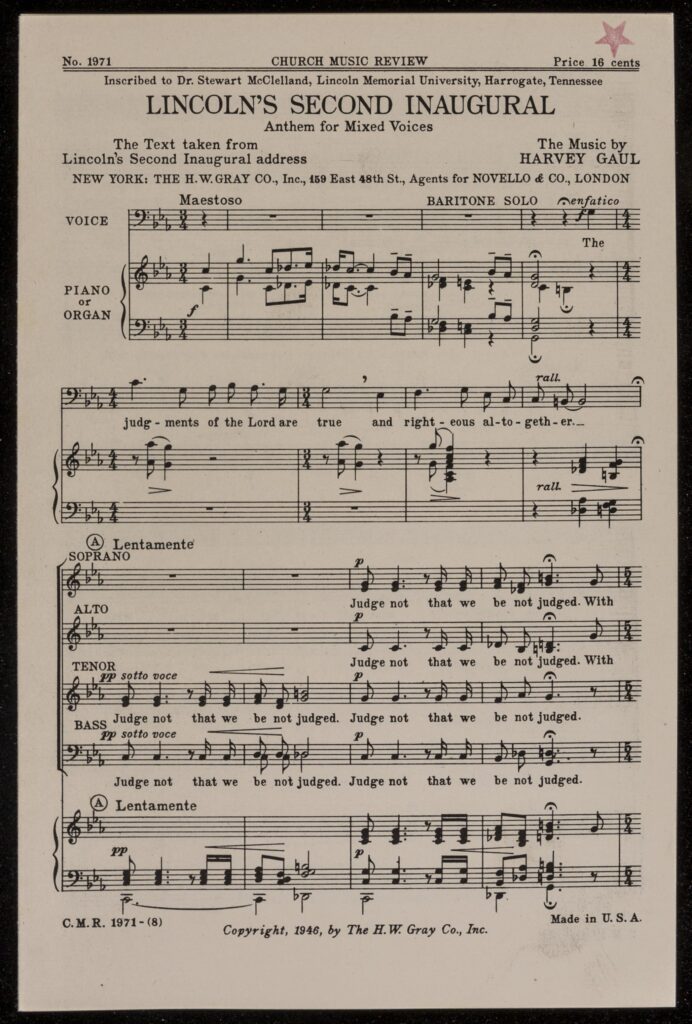

With increasing chronological distance from Lincoln, American composers appear more willing to think of him (and compose him) in abstract terms. There remain composers who embrace certain Lincoln tropes—standard stories and narrative approaches. For example, while historical research tells us that Lincoln’s voice had a high tenor quality, we often see his words placed into the voices of booming baritones. This decision tells us more about our assumption that the lauded oratory of a historical great man is something that should come from a low, deep voice. That is what we see in Harvey Gaul’s setting of a portion of the Second Inaugural Address. We have also only gradually seen the re-emergence of the Civil War’s emancipation narrative, the narrative that documentary research tells us was foremost in the minds of the vast majority of nineteenth-century Americans. If we understand the Civil War as a battle over the future of slavery, then speaking merely of Lincoln as the man who held the Union together is disingenuous. Gaul attempts to set that record straight. In his 1947 composition we see Lincoln as a man reminding the nation of God’s judgement for the sin of slavery. In the decades following the Civil Rights Movement, music proliferated with Lincoln serving as a voice to remind Americans that slavery was at the core of the Civil War.

While some of these works, like Gaul’s composition, show a genuine interest in correcting the historical record, we should avoid the desire to think of the post-World War abstraction of Lincoln as either obviously right or wrong vis-à-vis historical events. These compositions seek relevance on contemporary topics, but they are also the products of artistic freedom. In practice, what the composers are doing in these works is precisely what many citizens do: they build up memory of the past in ways that draw on lots of sources and then ask what it might mean today.

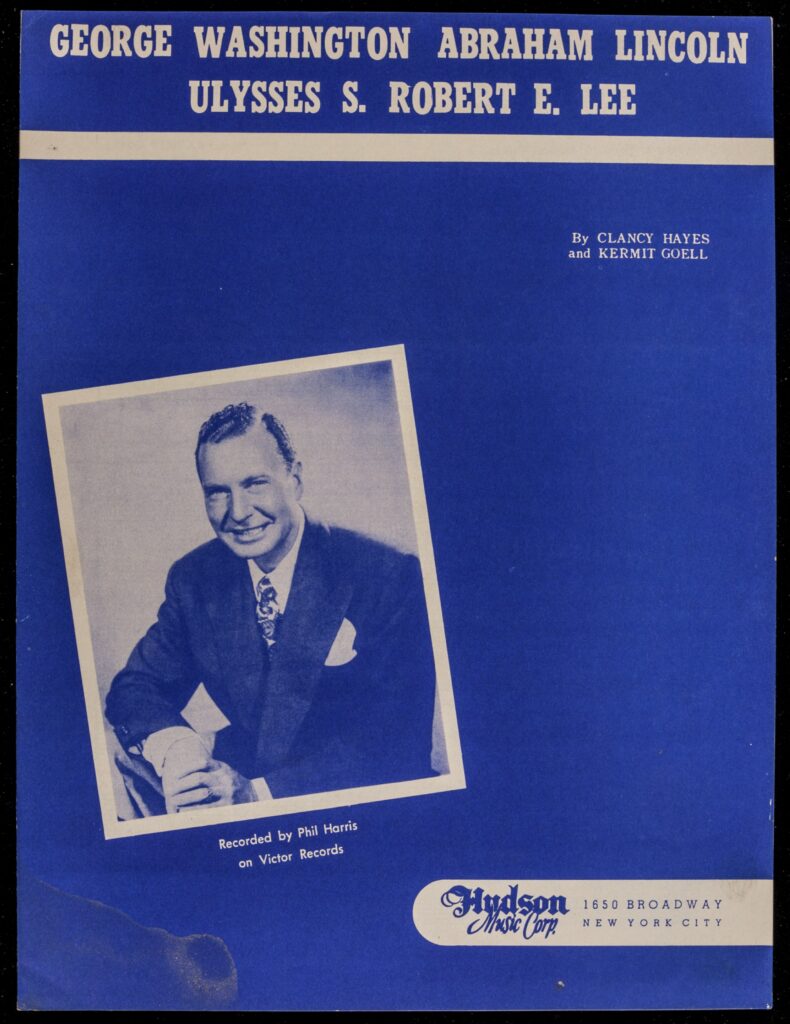

To some, Lincoln has become just another historical figure. This is the way in which Clancy Hayes and Kermit Goell joke about his name—and those of other dead historical men—in their song “George Washington Abraham Lincoln Ulysses S. Robert E. Lee.” For other composers, Lincoln has provided a pathway to address topics that were not on the sixteenth president’s radar. By 2009, the year of his bicentennial, Lincoln songs addressed gay marriage, the Arab-Israeli Conflict, and contemporary feminism. In this way, the very reason that composers in all different musical styles and traditions continue to use Lincoln for his words, his image, or even his name as a mere noun in a rhyme, is because he can still encourage American audiences to conjure many ideas about what the past means for the present.

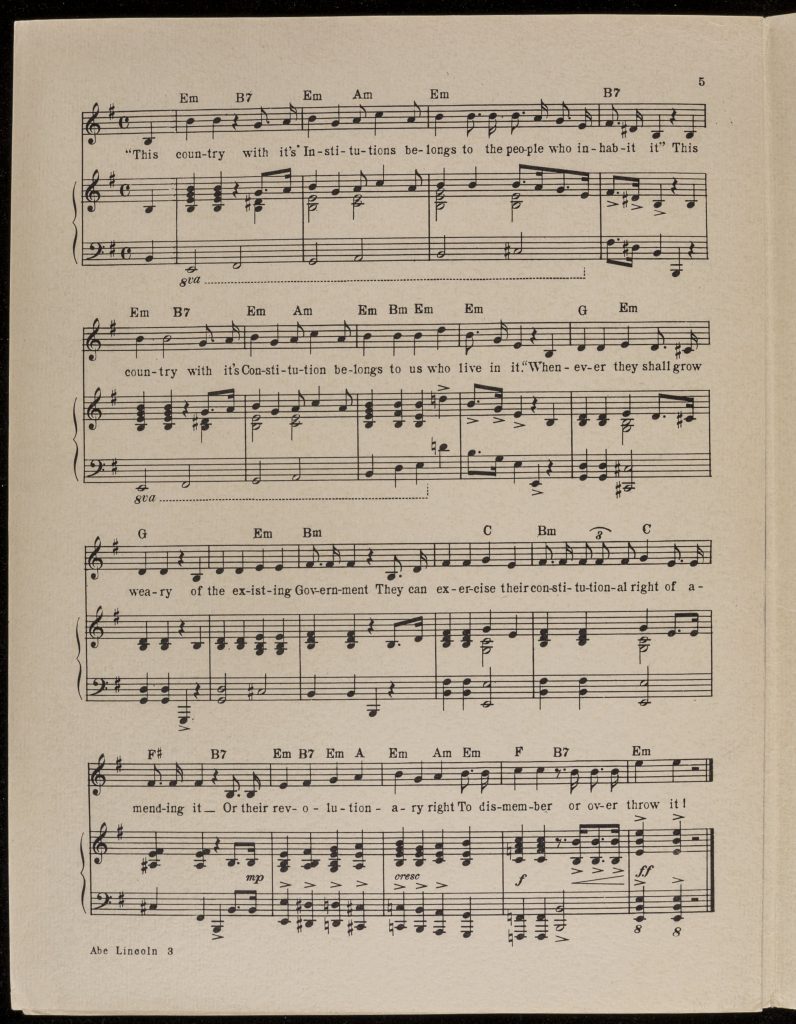

Selection: Clancy Hayes and Kermit Goell, George Washington Abraham Lincoln Ulysses S. Robert E. Lee (New York: Hudson Music Co., 1947).

This song attempts to comically play with the tradition of providing children historically weighty names, however, its particular combination demonstrates the way in which Lincoln is both lumped in with early presidents, such as Washington, and Civil War figures, such as Grant and Lee.

Questions:

- Gaul’s selection of a single passage from Lincoln’s Second Inaugural can be heard as powerful, angry, judgmental, moralizing, critical, paternal, and this list could go on at great length. How do you hear this passage from Lincoln? Why do you think Gaul was attracted to this passage in the immediate aftermath of World War II?

- Hayes and Goell’s song can be heard as a big joke, but some might also hear it as an unfortunate commentary on how Americans garble history and historical figures. Even if this song goes a little far in order to make a joke, are the composers right? Do we often just toss around historical names for the sense of potency that they convey?

Mourning and Commemoration of Lincoln in Music

Music played an important role in mourning and commemorating Abraham Lincoln. Examples of pieces from the time of his death and his birth centennial can be seen below.

The Uses of Lincoln in Music

Lincoln as both person and symbol has been co-opted for various ideological, social, and satirical purposes since his death. Music has been one way in which people have drawn Lincoln into their corner.

Further Reading

Bernard, Kenneth A. Lincoln and the Music of the Civil War. Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers, 1966.

Jordan, Philip D. “Some Lincoln and Civil War Songs.” Abraham Lincoln Quarterly 2 (Sept. 1942): 127–42.

Kernan, Thomas J. “Sounding ‘The Mystic chords of Memory’: Musical Memorials for Abraham Lincoln, 1865–2009.” (PhD diss., U. of Cincinnati, 2014).

McWhirter, Christian. Battle Hymns: The Power and Popularity of Music in the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Peterson, Merrill D. Lincoln in American Memory. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Schmidt, James. “Cenotaphs in Sound: Catastrophe, Memory, and Musical Memorials.” Proceedings of the European Society for Aesthetics 2 (2010): 454–78.

Schwartz, Barry. Abraham Lincoln and the Forge of National Memory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000.