Introduction

The islands of Zanzibar and Pemba off the East coast of Africa have long been part of a cosmopolitan Indian Ocean trading world. On these tropical islands, as well as the nearby coast, the ancient African civilization of the Swahili grew wealthy on trading links with India, Arabia, Egypt and China. By the 10th century, Islam was well established on the East African coast, and the ancestors of today’s Swahili had organized themselves into a series of city-states dotting the East African coastline. In the 14th century, Kilwa, off the coast of modern day southern Tanzania, was the center of the East African gold trade. Another famous 14th century city, Mombasa, exported spices, gold and ivory. Both were visited by the famous North African traveler Ibn Battuta. In the late 15th century, the newly arrived Portuguese fought for control over Mombasa and sacked Kilwa. Eventually the Omanis chased out the Portuguese and ruled Mombasa. Two Omani clans, the Mazruis and Busaidis, then fought for control of the coast in the 18th century.

By the mid-nineteenth century East Africa was in the middle of several profound economic transformations. On the islands of Zanzibar and Pemba, a line of sultans from the Busaidi family had established a state. The Busaidi ruler Seyyid Said bin Sultan had brought the other city states of the Swahili coast under his rule and united Oman and Zanzibar. Said’s power was dependent on British military support (who wished to use him to check French expansion) and Indian, especially Gujarati, financial capital. His subjects obtained wealth through plantations of slave-tended clove and coconut trees. On the opposite coast to the islands, slaves grew grain and other provisions to supply Said’s state.

The wealth from these plantation enterprises was used to fund expeditions of exploration and trade into the East African interior. Ivory was the primary commodity sought, as its global price rose continuously throughout the nineteenth century. Coastal merchants traded cloth and firearms for ivory. The expansion of firearms imports into East Africa created opportunities for political and economic entrepeneurs to create independent sources of wealth, by raiding for ivory and slaves. The slaves were then often sold to the coast, where they worked on the burgeoning plantations.

Traditionally, slavery in Africa differed from what we know as slavery in the United States in that the enslaved were more like kin than chattel. Women were often in higher demand as slaves than men, as powerful men could more easily incorporate them into their lineages as wives or concubines. The children of enslaved women who married a free man would be free. On the coast, Muslim slaveholders often manumitted their slaves, and many slaves converted to Islam before gaining their freedom. But slavery in nineteenth century Africa underwent a series of transformations. On the coast, slaves began to be used more and more to produce cash crops for sale on the world market, while in the interior, more and more societies began to sell slaves to gain access to firearms, which were then used to raid for ivory and slaves.

The economy of 19th century Zanzibar was thus largely dependent on slavery and the slave trade. Throughout East Africa, the vulnerable, especially women, children, orphans, and all those on the lower rungs of society, were at the most risk of being sucked into the trade. Through this process many ended up thousands of miles from their interior homes, on the Swahili coast, or further abroad in Oman or India.

Questions to Consider

- What were the links between abolition and imperialism in East Africa?

The Abolitionist Movement in East Africa

An abolitionist is someone committed to the end of slavery globally. By the early nineteenth century, the abolitionist movement in the Atlantic world had successfully abolished the slave trade, both in Great Britain itself and then later in the broader Atlantic world. In the middle decades of the nineteenth century abolitionists turned their attention to East Africa; this move coincided with a heightened interest by European explorers in mapping the frontiers of East Africa and finding the source of the Nile River.

Abolitionist history makes abolition look like a triumph of European modernity and human rights, but the truth is more complicated. The abolitionist movement in East Africa was both a humanitarian and an imperialist endeavor. It was humanitarian in that it viewed slavery as a moral crime against human dignity. Abolitionists believed slavery was a hindrance to civilized progress; they saw their own societies as vanguards of that progress. As historian Jonathon Glassman has written, “Colonial rulers imagined the suppression of slavery as but the first of a series of steps undertaken in the name of a moral obligation to free Africans from barbarism and bring them into the age of civilization and modernity.” (Glassman, “Racial Violence, Universal History” in Abolition and Imperialism in Britain, Africa, and the Atlantic, 175)

But abolitionism was also imperial and colonial. Imperialists believed in the necessity and benefit of establishing overseas colonies, creating an empire in the process. The colonies were to supply both resources for industrial Europe, and new markets for Europe’s finished goods. Abolition overlapped with and helped justify imperialism, culminating in European conquest of most of East Africa by the first decade of the twentieth century. The abolitionist movement, whose goal was bringing peace to a violent slavery-ridden land, helped accelerate violent conquest in the form of the European scramble for Africa.

The following documents were all written by European men committed to an ideology of abolition. While you may agree with their abolitionist views, you will need to interrogate the cultural biases they held against Africa and Africans. In most cases, they had a very limited understanding of the language and culture of the Africans they encountered. The selection of these sources demonstrate one of the central difficulties of writing African history in this period. Since European travelers more commonly wrote down their accounts of encounters with Africa, we are often left with little more than their viewpoint from which to write history. To recover the African viewpoint, historians often have to read these texts “against the grain,” analyzing the dominant reading of the text and scrutinizing its beliefs, attitudes, gaps, silences and contradictions.

Use the following documents to read “against the grain” about the humanitarian project of abolition and its overlap with colonialism. Try to imagine how different groups of Africans in the nineteenth century might have perceived the abolitionist cause. Finally, try to answer the following question: How, step by step, did a humanitarian project culminate in military intervention and occupation?

David Livingstone and his Journeys

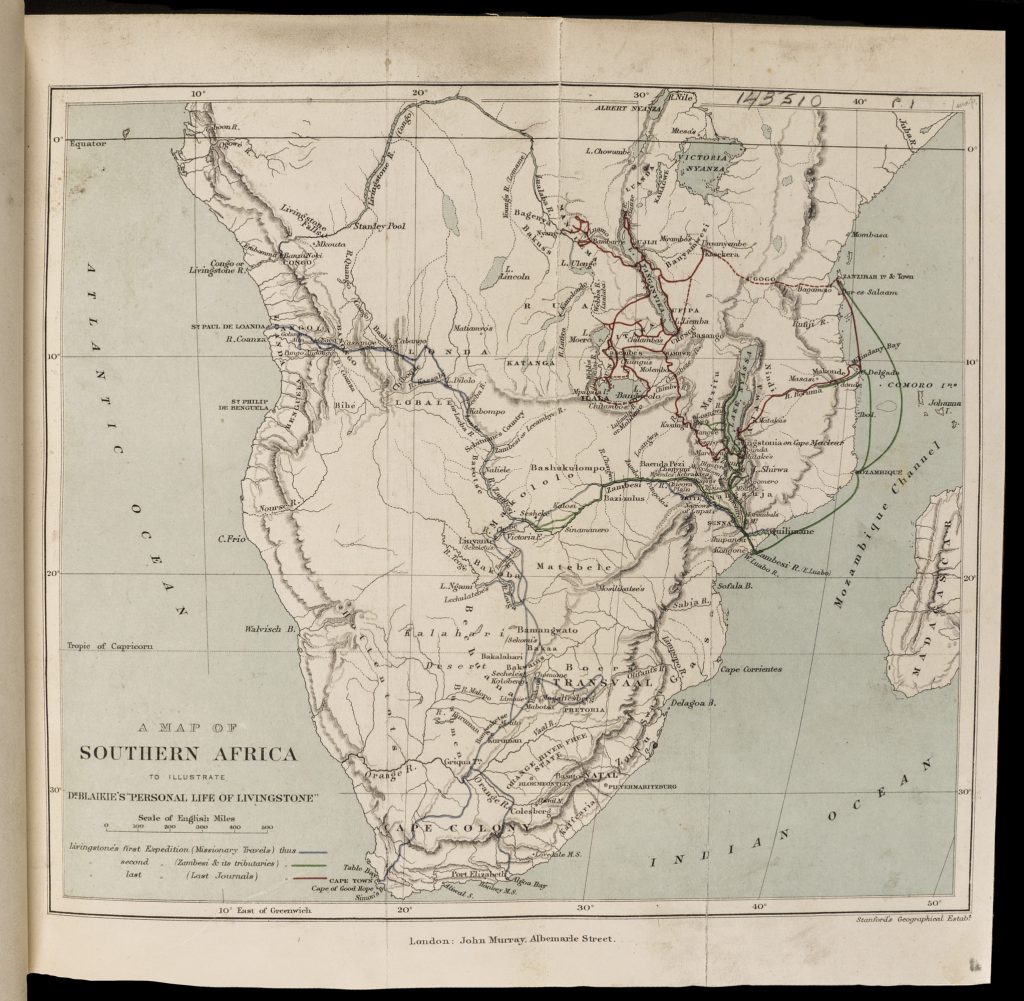

Many early European explorers of East Africa were abolitionists, beginning with David Livingstone. Livingstone was the first missionary to successfully undertake multiple trips across eastern and southern Africa. He traveled without military escort, using his medical skills to gain entry into the various societies and states of the region. He helped spur explorers like John Speke and Richard Burton to find the source of the Nile river. He, more than anyone, was responsible for disseminating ideas and images of Africa to a generation of Britons. In particular, he emphasized the importance of Christianity, commerce and civilization for developing Africa. Slavery, he believed, had underdeveloped Africa, and only capitalism and Christianity together could end that scourge and bring Africa to a higher stage of civilization. Livingstone envisioned a series of mission stations across Africa, financed by European capital, and staffed by missionaries trained to work within African societies.

Livingstone left several personal observations of slavery, most of which blamed the slave trade on ‘Arabs’. His stark descriptions of the cruelty of slavers galvanized public opinion. Although Livingstone himself did not advocate military intervention and imperialism, the following documents show that those inspired by him came to the conclusion that abolition could only be effective through a European led-campaign to break the military power of the East African Arabs. In spite of his condemnation of East African Arabs as slavers, Livingstone had to rely on them for safe passage, supplies, and guidance at almost every turn.

Questions to consider:

- Examine Livingstone’s journeys on the map, and notice how many of them began in Zanzibar. Why do you think this was? Who controlled Zanzibar at this time?

- Go to the Livingstone Project and click on the letter from Bambarre. What does Livingstone say about slaves and ivory in Central Africa? Why are so many Zanzibaris in Central Africa?

Henry Stanley’s Journeys

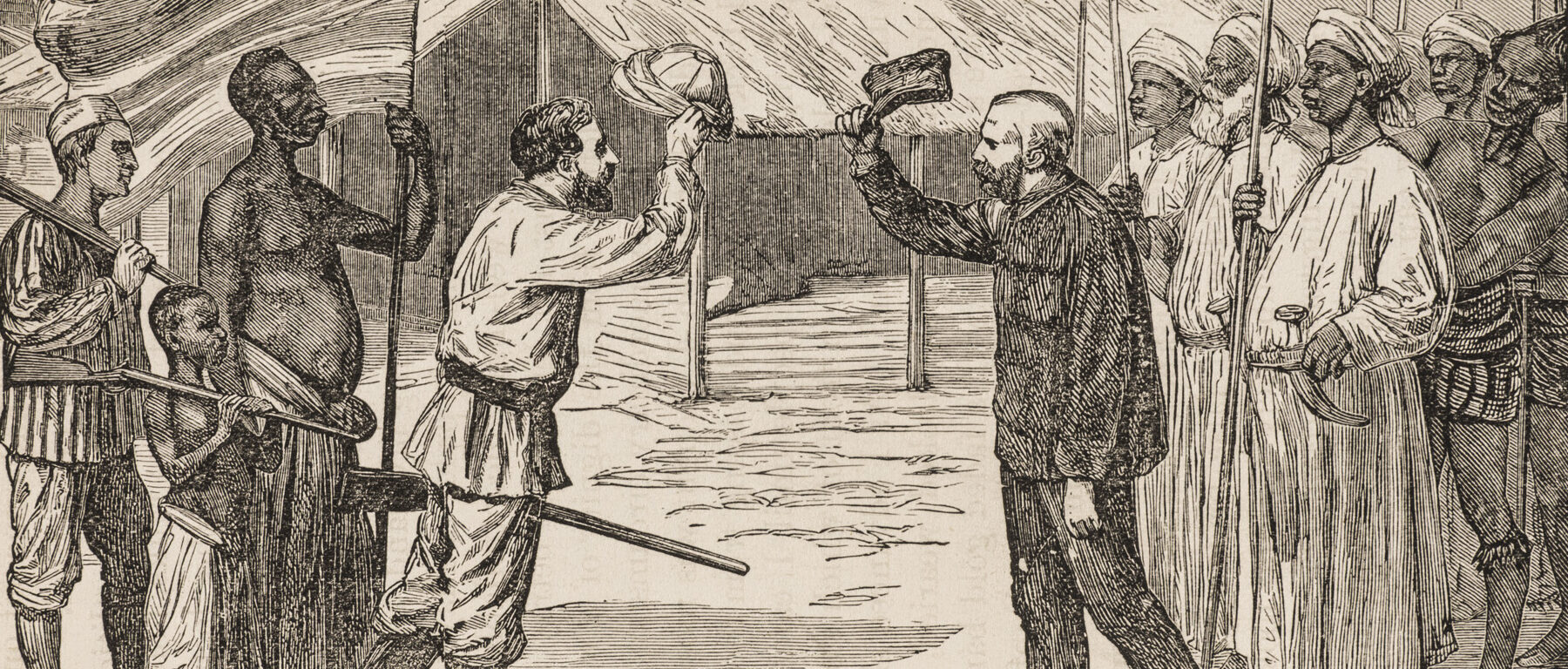

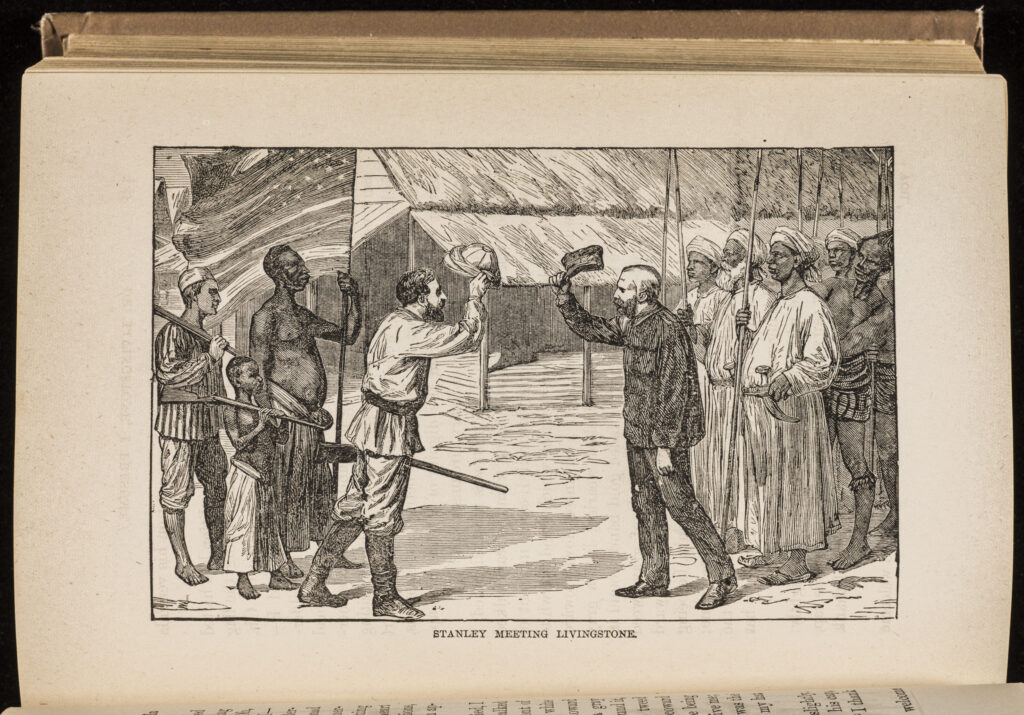

Henry Stanley was the illegitimate son of a young Welsh woman who abandoned him as a baby. He eventually emigrated to America and had a tumultuous life there, fighting in the Civil War on both the Confederate and Union sides. Stanley gained international fame when he was dispatched in 1869 to find David Livingstone, who had been traveling in Africa. He found Livingstone in 1872 (above). After being feted in Europe for his accomplishments, Stanley returned to Africa with a commission from King Leopold of Belgium to map the lakes and rivers of central Africa and claim additional territory for Leopold’s African colonization project. King Leopold cleverly hid his intentions underneath the cloak of abolitionism and development, and Stanley was a willing participant in Leopold’s schemes.

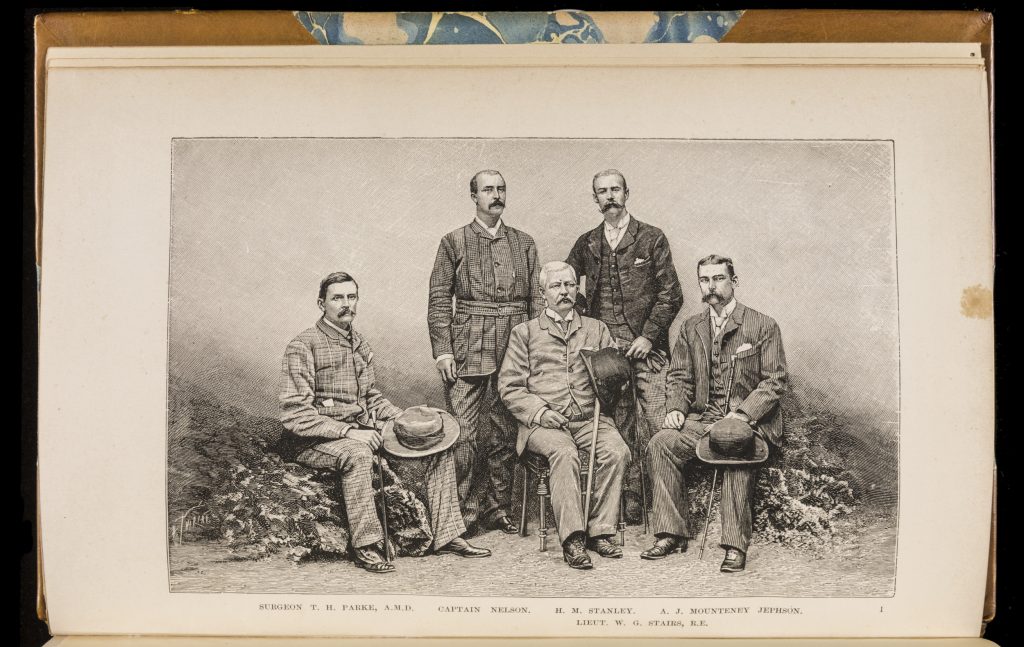

Selection: H. M. Stanley, In Darkest Africa: or, The quest, rescue and retreat of Emin, governor of Equatoria, title page, frontispiece, 9 (1890).

Stanley’s actions in Africa provoked controversy. He associated himself with the abolitionist cause and the ideals of legitimate commerce. Yet he traveled at the head of large heavily armed caravans and was not afraid to use violence when he felt mistreated. This makes his comments on civilization and human rights in the excerpts below all the more interesting. He was accused on several occasions of exploiting those in his employ, and at one point, he and the famous Zanzibari merchant and slave-trader, Tippu Tip, had a public falling out, after he felt Tippu Tip had reneged on their agreement. Stanley, as well as other European explorers had an ambiguous relationship with powerful Africans like Tippu Tip. They relied on Tippu Tip for guidance and safe passage, even as they recognized that he was a part of the system of slavery that they wished to destroy.

Questions to Consider:

- How did Stanley’s journeys into Africa differ from Livingstone’s journeys?

- What does the word ‘abid’ mean? Where does the word come from?

- When does Stanley say true civilization will be established in Africa?

British Naval Blockade of the East African coast

The British faced significant obstacles in their attempts to control the slave trade; foremost among them were the demands of the French. Though the British attempted to impose a naval blockade on the coast and prevent dhows filled with human cargo from departing, slave dhows still left Portuguese controlled ports in Mozambique bound for French colonial plantations in the Mascarenes. Lyons McLeod, the British consul in Mozambique, reported with furious outrage on this trade in human beings. McLeod believed that, were the slave trade to be suppressed, British led capitalism would bring peace and prosperity, “hidden sources of industry will gradually be brought to light” and “Zanzibar may become a second Singapore.” (McLeod, 47) But as staunchly abolitionist as McLeod was, he relied totally on slave labor for his domestic needs. When the Portuguese pressured him and his wife, going so far as to have his landlord deport him and take away his domestic servants. Eventually, Portuguese pressure forced him to flee Mozambique. James Frederic Elton began his East African career assisting in the suppression of the slave trade. He, like McLeod, was eventually appointed British consul to Mozambique, and also like McLeod, he observed with frustration how slave traders evaded British attempts at interference. Elton assisted in liberating slaves held by Indians, who, under new laws passed by the British, were considered British subjects and therefore could not own slaves. His many tense encounters with coastal merchants show that the merchants thought of the British not as humanitarians, but as imperialists bent on taking their territory and property.

Selection: Lyons McLeod, Travels in Eastern Africa; with the narrative of a residence in Mozambique, frontispiece, 38-39 (1860).

Questions to Consider:

- How do you think frustration at being unable to interfere in the slave trade influence British diplomats and men of influence to believe in the necessity of imperialism?

Verney Cameron and the Commercial Development of Africa

Verney Lovett Cameron was a British navy officer who was chosen to lead an expedition in 1872 to find Livingstone. Although he failed in this, as Livingstone had already passed, Cameron did succeed in traversing equatorial Africa from east to west. Cameron was a passionate anti-slavery advocate. In the memoir of his travels, Across Africa, he links the ending of slavery to Africa’s colonization by Europeans. He is often credited with being the first to put forth the idea of a railway to run across Africa from Cape Town to Cairo, often known as the ‘Cape-to-Cairo’ railway.

Selection: Verney Lovett Cameron, Across Africa, 535-541(1885).

Questions to Consider:

- What is Cameron’s belief about indigenous African rulers and African society in general? How are they to be treated in this commercial development he envisions?

- What is the role of the Kongo and Zambezi rivers in Cameron’s vision for East African development? What about railways? What role would Mombasa play in this railway project?

- What does Cameron mean by ‘the choicest gifts of nature by which he is now surrounded…the value of which he is at present ignorant’?

- What is the ‘question now before the civilized world’ regarding Africa? What does Cameron see as the answer to that question?

- Notice the praise Cameron has for King Leopold of Belgium. Why does he believe King Leopold’s rule over the Congo is a positive sign for the future?

- Do you see any parallels between Cameron’s project and the contemporary movements to ‘help’, ‘save’, or ‘develop’ Africa? List some similarities and differences.

Cardinal Lavigerie and the Crusade Islam, Arabs and slavery

Cardinal Lavigerie was a French Catholic priest and staunch abolitionist. In 1868, he founded the ‘White Fathers,’ an order who founded numerous missions to Africa and became famous for their confrontation with slave owners in East Africa. He gave rousing speeches to rapt audiences about the abolitionist cause in Africa, portraying himself as a humble servant on the frontlines of a great struggle for justice in what he called a ‘half-civilized continent.’ His 1888 speech in London was attended by some of the most powerful men in England, including Lord Granville, former Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs.

Selection: Cardinal Lavigerie, Slavery in Africa: A Speech, title page, 6, 18-21 (1888).

Questions to Consider

- What is noblesse oblige, and how does it relate to Lavigerie’s argument against slavery?

- Why does Lavigerie praise European explorers of Africa?

- Why does Lavigerie call himself an ‘African of long standing’?

- What praise does Lavigerie have for David Livingstone?

- Appendix I and II are included with Lavigerie’s speech. What purpose might they serve to the English reader of this pamphlet? Who is appendix I written by?

- Why does the author of Appendix I see military force as necessary to end slavery in Africa?

- Explore the language of Appendix II. How are slavery and the slave trade portrayed?

- How are Muslims [Mussulmans], Arabs, and Africans portrayed in Appendix I and II? Discuss some of the stereotypes.

Frederick Lugard and the Labor Question in East African Colonies

Frederick Lugard was born in the India under the British empire. He had a distinguished career in the British military before serving on several military expeditions against slavery around Lake Nyasa (another area originally explored by Livingstone, see map above). Lugard became known in Africa for his military conquest of Uganda, delivering the region to the British empire as a protectorate. Lugard believed that colonialism and imperialism were necessary to protect missionaries, traders and other agents of ‘civilization’ in Africa. He later became renowned for elaborating the theory of ‘indirect rule,’ a method of colonial governance which was supposed to enlist local Africans to govern themselves under British imperial tutelage. With Lugard, we see the full scale implementation of a strategy of military and colonial conquest in the service of abolition and other humanitarian aims.

Selection: Frederick Lugard, The Rise of our East African Empire: Early Efforts in Nyasaland and Uganda, title page, frontispiece, 487-488 (1893).

Questions to Consider:

- What does Lugard think the role of European colonialism in Africa should be? What is needed to make European colonies in Africa profitable?

- What does Lugard think about the link between abolition and labour? What does he say Europeans should do if Africans were to refuse to labour for Europeans?

- What does Lugard mean by ‘we must find the means to do so in spite of them’?

- What is the concern Lugard mentions about how abolition will affect the labor market? What does this suggest about the shifting goals of abolition as it became tied to the project of European imperialism?

Abolitionists in East Africa

A number of European abolitionists traveled widely in East Africa during the late nineteenth century, for a variety of social-political reasons and personal motivations. See below for some examples of texts and images concerning these figures.

Further Reading

Hochschild, Adam. King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1999.

Jeal, Tim. Stanley: The Impossible Life of Africa’s Greatest Explorer. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007.

Nwulia, Moses D.E. Britain and Slavery in East Africa. Washington DC: Three Continents Press, 1975.

Peterson, Derek (ed.) Abolition and Imperialism in Britain, Africa and the Atlantic. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2010.

Sherrif, Abdul. Slaves, Spices and Ivory in Zanzibar: Integration of an East African Commercial Empire into the World Economy, 1770–1873. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1987.