Introduction

Modernism—the term is still brash and unstable—signifies a range of aesthetic tendencies that erupted in part as a response to transformative shifts in transportation, technology, communication, and production. An art of cities, modernism spread across Europe during the first decades of the twentieth century—especially in Paris, London, Vienna, and Berlin—and found expressions in many other global capitals from Buenos Aires to Beijing. Whether modernism began before the First World War or after is the subject of scholarly debate. To be sure, modernism was catalyzed by the unprecedented violence and psychic trauma that were the result of modern military technology.

In America, modernism expressed itself with dramatic flair in the bohemian enclaves of New York City, especially areas of Greenwich Village and Harlem. Densely populated urban environments fundamentally altered how individuals perceived the world, whether from the vantage of a train, factory floor, skyscraper, or the teeming streets below. If the writers of modernism took a perspective, then it was a vision of multiplicity.

In Chicago, artists and writers were also drawn into the sweeping transformations of the first half of the twentieth century, producing work that was well informed of the most avant-garde expressions in Europe as well as the vernacular cultures of America. The very reasons that have made this city lesser known in the narratives of modernism are also what defined the nature of its art. Located in the Midwest, a region overlooked or habitually patronized by the rest of the country, Chicago was often unknown abroad. Many of the city’s cultural institutions were founded around the time of the Chicago World’s Fair in the 1890s. By European standards, these new institutions could hardly set aesthetic standards. But Chicago’s distance from a European and an East Coast critical establishment could be intellectually liberating. Chicago’s lack of tradition allowed writers freedom from the eyes of critics and competitors. Journalist and screenwriter Ben Hecht—who moved from Chicago to New York and Hollywood—looked back on his time in Chicago with deep nostalgia: “We were all fools to have left Chicago,” Hecht reminisced. “It was a town to play in; a town where you could stay yourself, and where the hoots of the critics couldn’t frighten your style or drain your soul.”

Despite—or perhaps because of—critical neglect, geographic remoteness, and the city’s industrial identity, writers and artists in Chicago produced works that were vital to the emergence and expression of modernism. They experimented with how to register the unsettling yet often thrilling sense of transience and change. Some artists embraced the power of machines, speed, and violence, or the oddity of composing on a new piece of technology, the typewriter. Other artists decried the age by emphasizing hand-made craft. Indeed, the very growth of a literary culture in Chicago coincided with the advent of modernism: its writers and artists were born into a moment of transformative possibility.

The following collection of documents approaches the complexities of modernism by taking Chicago as an exemplar, with a focus on literature and the visual arts. There were many other modes of modernist expression in Chicago, including the vernacular ballets of Ruth Page and Katherine Dunham and the virtuosic improvisations of Chicago’s blues and jazz performers. Architecture, of course, is Chicago’s most celebrated modernist art form, from the steel-frame construction of the 1890s to the commercial architecture of the New Bauhaus at mid century. Writers and artists often took architectural modernism as a metaphor for their own experiments, for example the metaphors of space and structure that suffuse the 1920s poetry of Mark Turbyfill, and America’s first jazz-ballet, “Skyscrapers” (1926), by John Alden Carpenter. But modernism in Chicago—like everywhere—was always many things.

Please consider the following question as you review documents:

- How did cities—especially Chicago—influence and inspire the art and literature of the modernist movement?

- What social and aesthetic conventions did modernism challenge?

- What was distinctive about modernism in Chicago?

Cities

The rise of industrial capitalism, the expansion of machine-based production, and innovations in transportation—especially the railroad—contributed to the growth of modern cities, especially Chicago. The population of Chicago quintupled between 1870 and 1900, from around 300,000 to over 1.5 million inhabitants: it outstripped other boomtowns in America to become the exemplary gateway city. In the decades following the First World War, Chicago was a key destination for thousands of African Americans fleeing the South, who were pushed by white supremacy and pulled by opportunities in the Northern, industrial economy—especially in the stockyards, railroads, and steel mills.

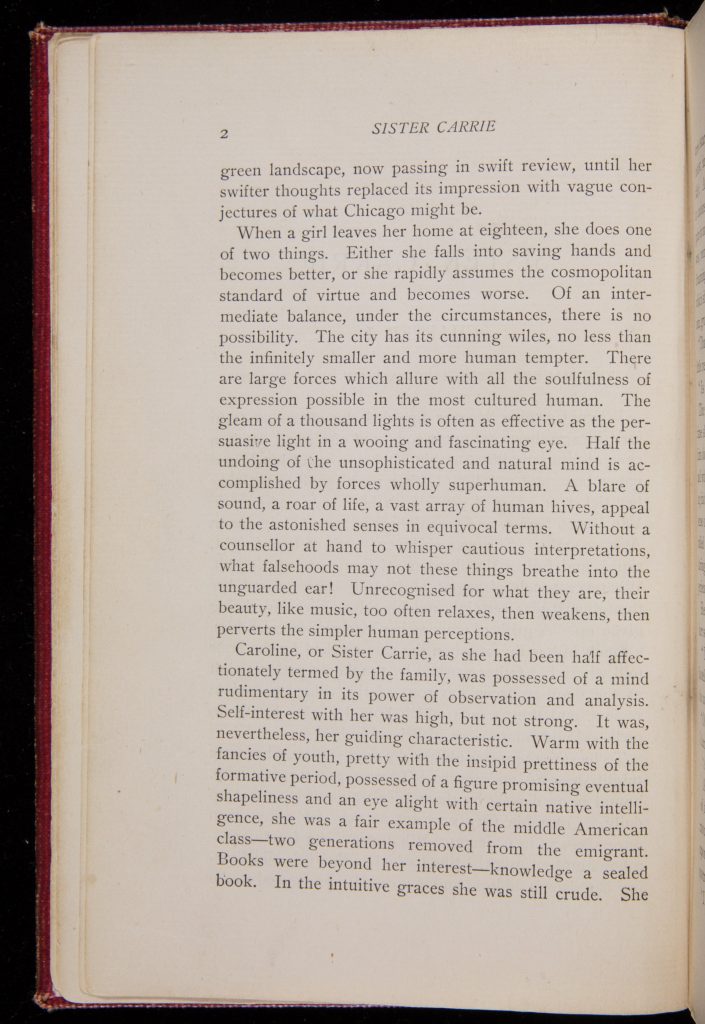

Selection: Theodore Dreiser, Sister Carrie, title page, 1-2 (1900).

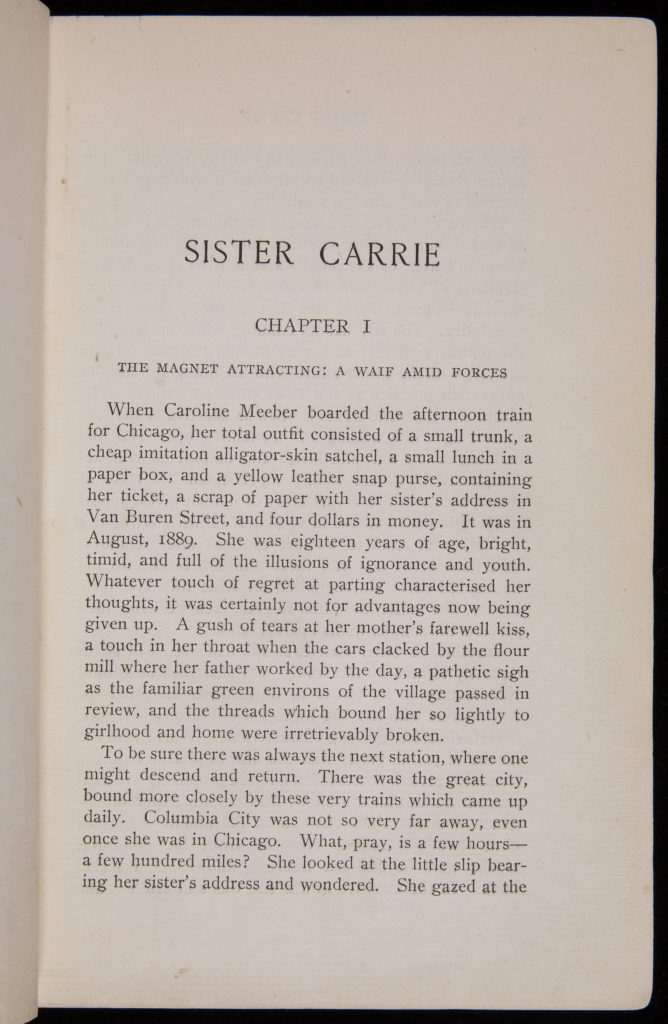

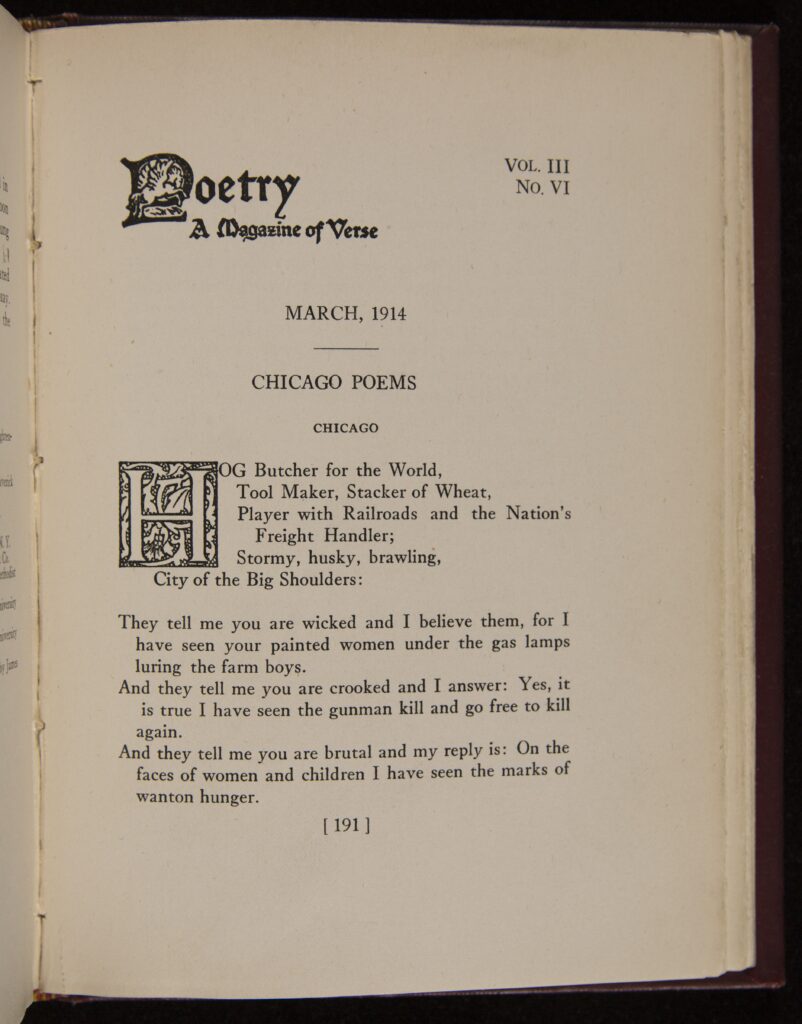

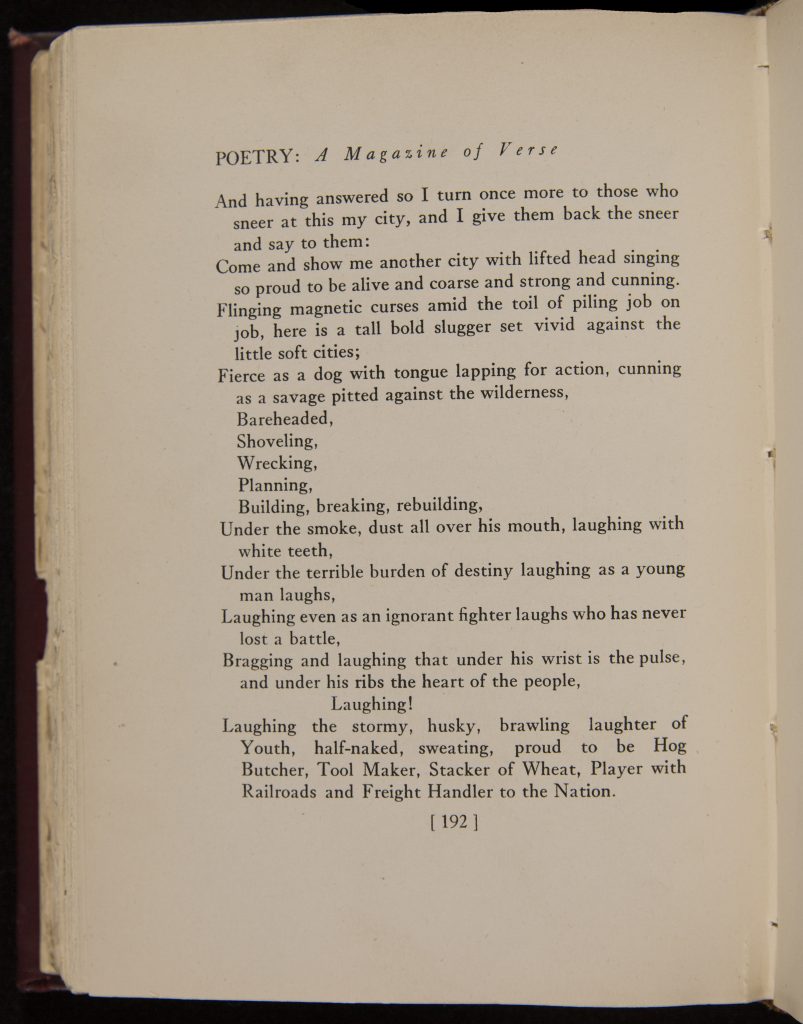

The modernist city became not simply a backdrop for many writers and artists but also an experience that shaped modern psychology and demanded aesthetic interpretation. In the following literary excerpts, Chicago is both alluring and overwhelming, a place that inspires wonder and disillusionment. In the first excerpt from chapter one of Theodore Dreiser’s Sister Carrie (1900)—the first major novel set in urban America—eighteen-year-old Carrie boards a train from a small town in Wisconsin to Chicago. The novel describes how Carrie becomes irrepressibly attracted to the material, erotic, and artistic power of the big city, a situation that many of Dreiser’s readers found scandalous. Controversy also erupted over Carl Sandburg’s 1914 series of “Chicago Poems,” first published by editor Harriet Monroe in Poetry magazine. Sandburg depicted the city’s industrial ferocity, its corruption, racism, and filth—in blunt language and unconventional meter. Many readers at the time did not think these lines were real poetry. And in the third excerpt, Richard Wright describes the shock of his 1927 arrival into Chicago from rural Mississippi. Wright arrived in the cold, and was stunned by the extremity of Chicago’s weather. Echoing Dante and T. S. Eliot, Wright describes how Chicago was an intimidating grid of steel and stone, a “machine-city,” an “unreal city,” “wreathed in palls of gray smoke.” For him, Chicago was hardly the Promised Land but rather a kind of living hell.

Selection: Carl Sandburg, “Chicago,” Chicago Poems, 191-192 (1914).

Selection: Richard Wright, Black Boy: A Record of Childhood and Youth, title page, 223-228 (1945).

Questions to Consider

- Do the opening paragraphs of Sister Carrie offer any reasons for why Carrie wants to go to Chicago?

- Think about the title of the first chapter of Sister Carrie. What does it suggest? Does Dreiser’s language in the opening pages of the novel support or contradict the idea behind his title?

- How is the city of Chicago personified in the opening stanza of Carl Sandburg’s “Chicago”? Why do you think these lines are repeated at the end of the poem?

- Is Sandburg’s “Chicago” a celebration or a critique of the city?

- What does Richard Wright notice about race relations when he first arrives in Chicago? How would you describe his psychological condition?

Gender

First wave feminism—bound up in the fight for women’s suffrage—was a major catalytic influence upon the modernist movement. For women to live productive lives in the public sphere, including the pursuit of creative professions, they must first slay the “angel in the house,” claimed modernist writer Virginia Woolf, by which she meant the pious, self-sacrificing Victorian wife, devoted to her home and family. Artists and writers of the modernist movement also ironized the rhetoric of masculinity and military honor in response to the devastating losses of the First World War. Working as a journalist in Chicago after the war, Ernest Hemingway began writing stories and poems that took the formation of manhood as a central concern, as did Hemingway’s mentor Sherwood Anderson. Many of modernism’s revolutionary ideas and aesthetic forms were part of a larger discourse about the construction of gender itself. From representations of the female nude during the 1913 Armory Show—cubist and abstracted—to controversies over female sexuality as depicted in novels like D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928) and Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood (1936), modernism challenged conventions of ideal femininity, and also depicted less clear-cut distinctions between women and men. Many new “types” turned up in modernist art and literature, including the New Woman, the Flâneur, the Dandy, and the Flapper.

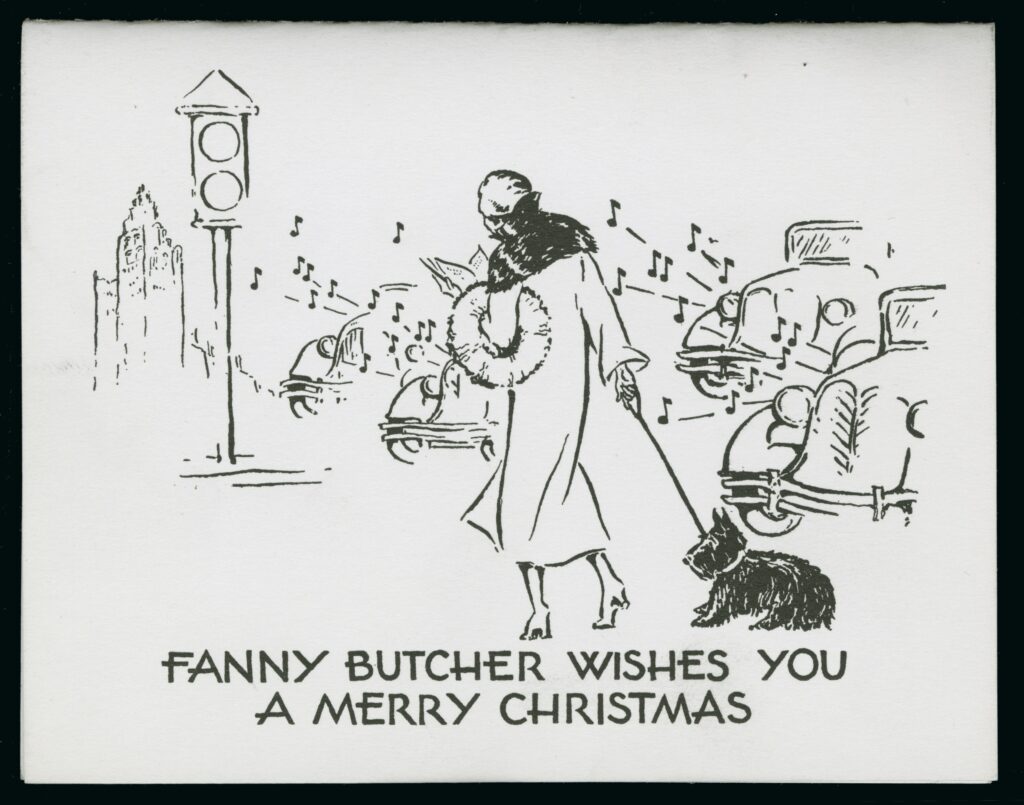

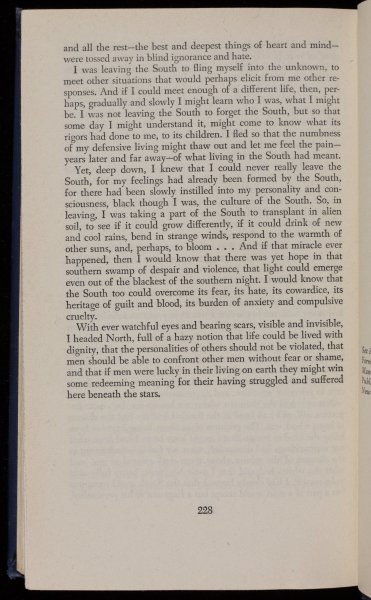

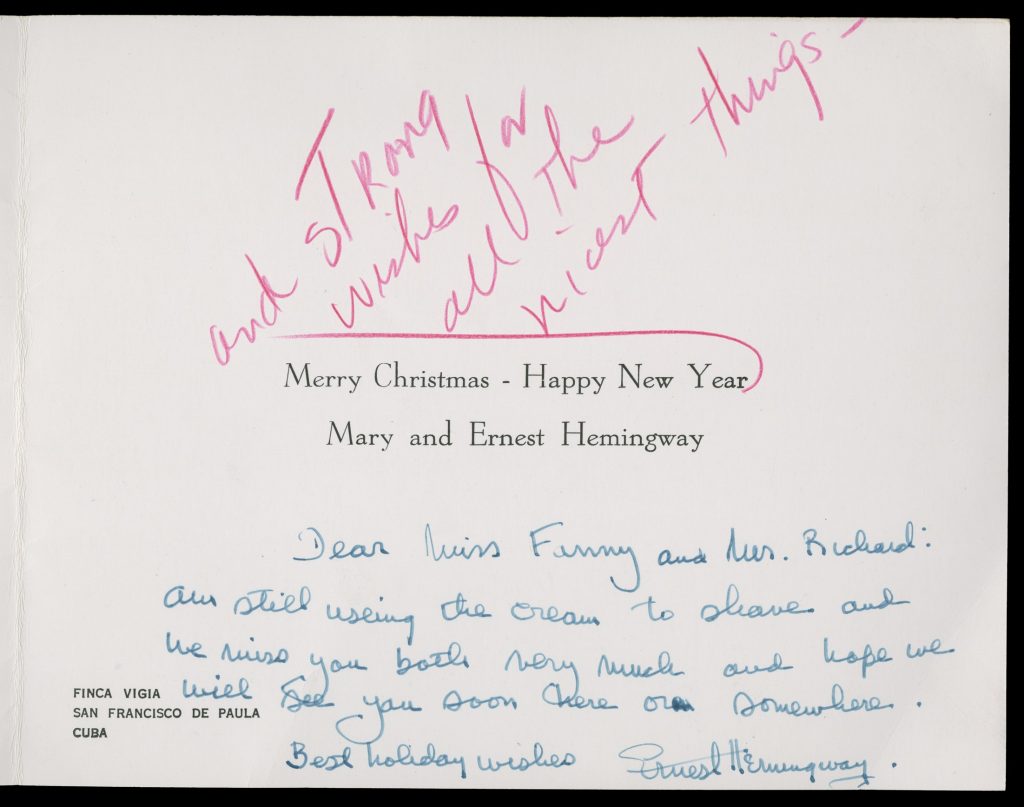

The documents in this section include stylized images of literary critic Fanny Butcher—who worked at the Chicago Tribune for over fifty years, and also ran a popular bookshop from 1919 to 1927. Butcher became friends with many twentieth-century writers, including H. L. Mencken, Willa Cather, Sinclair Lewis, and Hemingway. Though Butcher panned Hemingway’s first novel The Sun Also Rises (1926), they eventually developed a friendship and correspondence. Hemingway found in Butcher an important register for how his books might appeal to a Midwestern and mainstream readership. Although Butcher may not have called herself a feminist, she was a trailblazing figure, who navigated Chicago’s male-dominated newspaper culture, and acquired vast influence over what books were bought and read in Chicago and the larger Midwest. Her annual Christmas cards—sent out to a long list of friends and colleagues—were composed in black and white and orange, and almost always featured her reading a book, with her small dog nearby. (After 1935 when she married, the cards depict her husband too.) Butcher was given books by many poets and writers, including Eunice Tietjens, whose poem “A Plaint of Complexity” is contained in her 1919 collection Body and Raiment. A constant traveler, Tietjens served as a World War I correspondent in France for the Chicago Daily News in 1917-1918, and worked on staff at Poetry magazine for more than twenty-five years.

Selection: Eunice Tietjens, Body and Raiment, “A Plaint of Complexity,” 13-16 (1919)

Questions to Consider

- The photograph of Fanny Butcher aboard the steamship S. S. Paris is affixed upon a souvenir pocket mirror. It was taken during Butcher’s second trip to Europe in 1931, after she sold her bookshop and was able to travel abroad. Her Christmas card depicted here is from the 1920s. What do you notice about how Butcher presents herself? How would you characterize her style?

- What does Butcher’s Christmas card suggest about the act of reading?

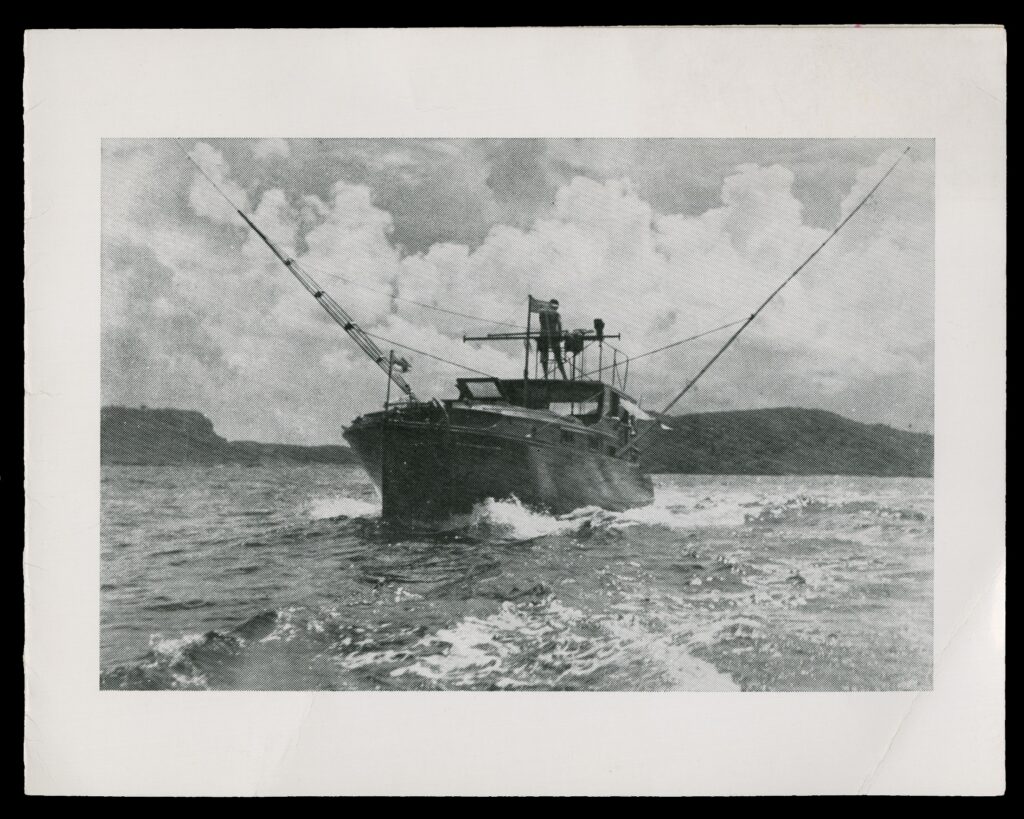

- The cards that Butcher saved from Ernest and Mary Hemingway include one with Ernest sailing his fishing-boat Pilar off the coast of Cuba. Inside, Hemingway thanks Butcher for her gift to him of shaving cream—for his chronic sensitive skin. How does the photograph on the cover of Hemingway’s Christmas card contrast with Butcher’s Christmas card? What does the inside note tell us about their friendship?

- Eunice Tietjens’s poem “A Plaint of Complexity” suggests that the speaker contains multitudes, an idea that harkens back to American poet Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself.” What kinds of selves does she contain? Which of these selves would you consider traditional or radical?

- What is the cause of the speaker’s “complexity”? And what kind of “self” is attributed to Chicago?

Movements

During the first half of the twentieth century, modernism encompassed many ideological, political, and aesthetic movements—or isms—including Symbolism, Cubism, Dadaism, Futurism, Vorticism, Imagism, Surrealism, and Expressionism. Each movement had its own set of ideas put forth in manifestos and periodicals, and celebrated at salons and parties. The cohorts of artists and writers that coalesced around these movements sometimes lasted for a few years or just a few months, but they left an indelible mark on the artistic production of the era.

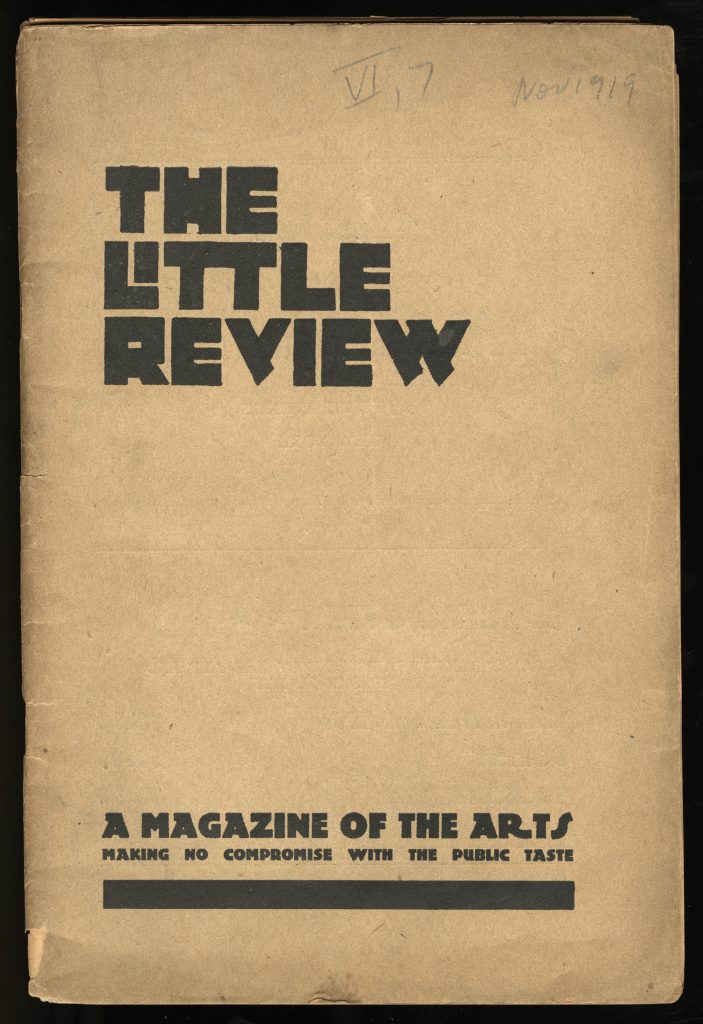

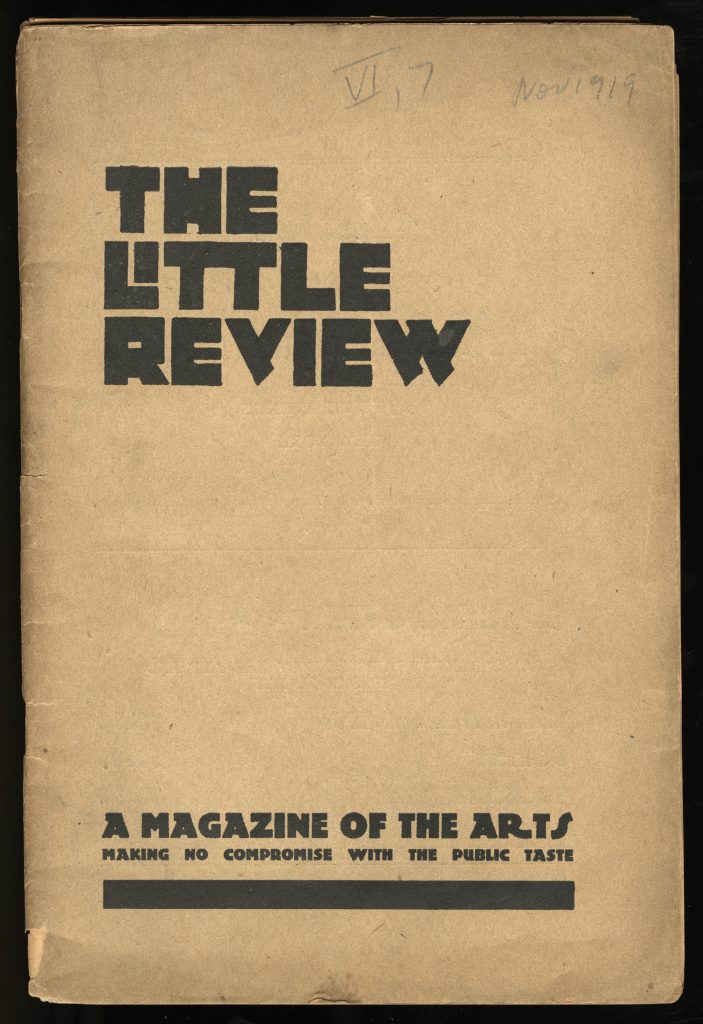

In Chicago, the word “little” was often used to describe avant-garde artistic groups, even though “little” is precisely what Chicago is not. It started with “The Little Room,” founded in the 1890s, an informal community that included poet and critic Harriet Monroe, novelists Henry Blake Fuller and Hamlin Garland, and the sculptor Lorado Taft, among many others. The desire for “littleness” was purposefully at odds with the big business of the city in which these artists and writers found themselves. Chicago’s “little theaters” and writer Margaret Anderson’s periodical of arts, literature, and politics, the Little Review, launched in 1914, similarly and self-consciously stood apart from the commercial drives of the city.

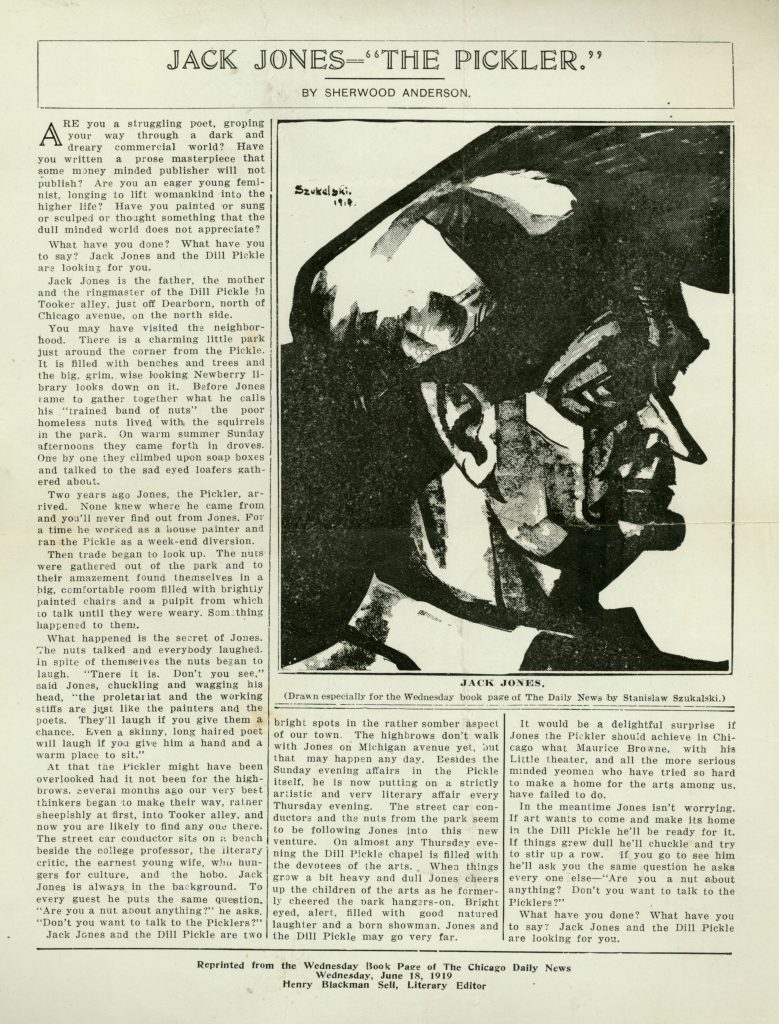

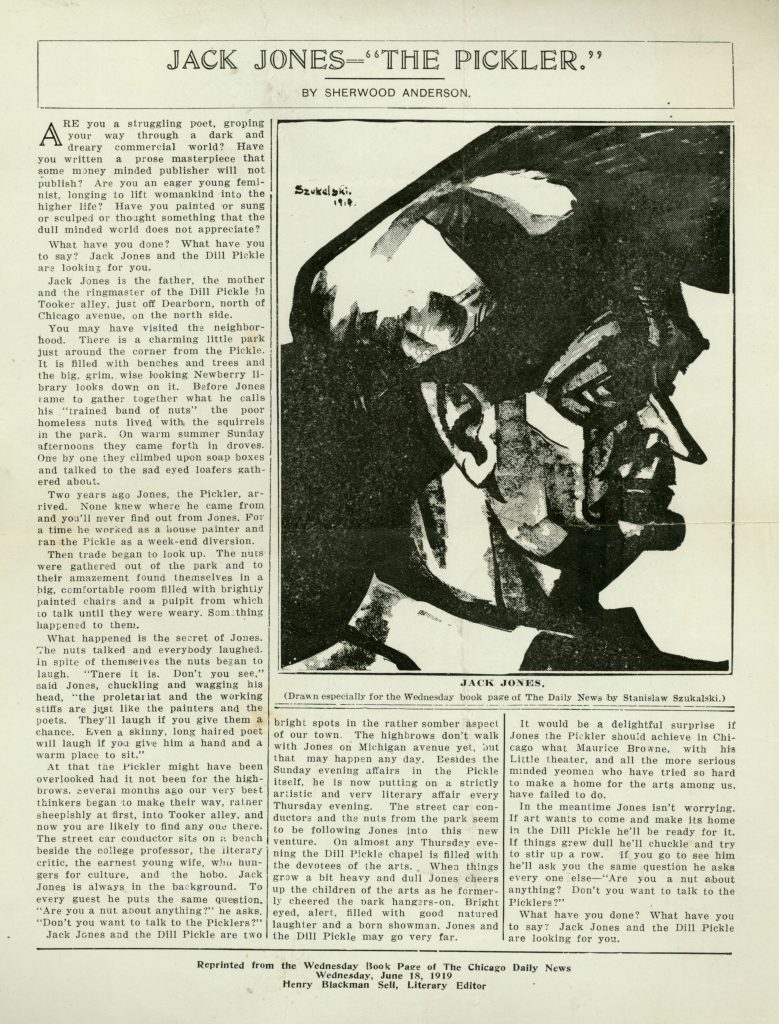

The Dill Pickle club was one of many key sites in Chicago for artistic, literary, political, and social exchange. Located down a narrow alley on the near north side, and announced on its door: “Step High, Stoop Low, Leave Your Dignity Outside.” Founded in 1914 by Jack Jones, an organizer for the Industrial Workers of the World, the club presented speakers who debated modern art, free love, Marxism, and psychoanalysis, among many topics, and also staged the plays of Henrik Ibsen, George Bernard Shaw, Susan Glaspell, and Eugene O’Neill. Writer Sherwood Anderson, a regular attendee at the Dill Pickle, claimed it was a place where “the street car conductor sits on a bench beside the college professor, the literary critic, the earnest young wife, who hungers for culture, and the hobo.” The Dill Pickle’s frequent masquerade balls—where cross-dressing was rife—were especially popular and fostered an underground gay culture. The club lasted until the mid 1930s.

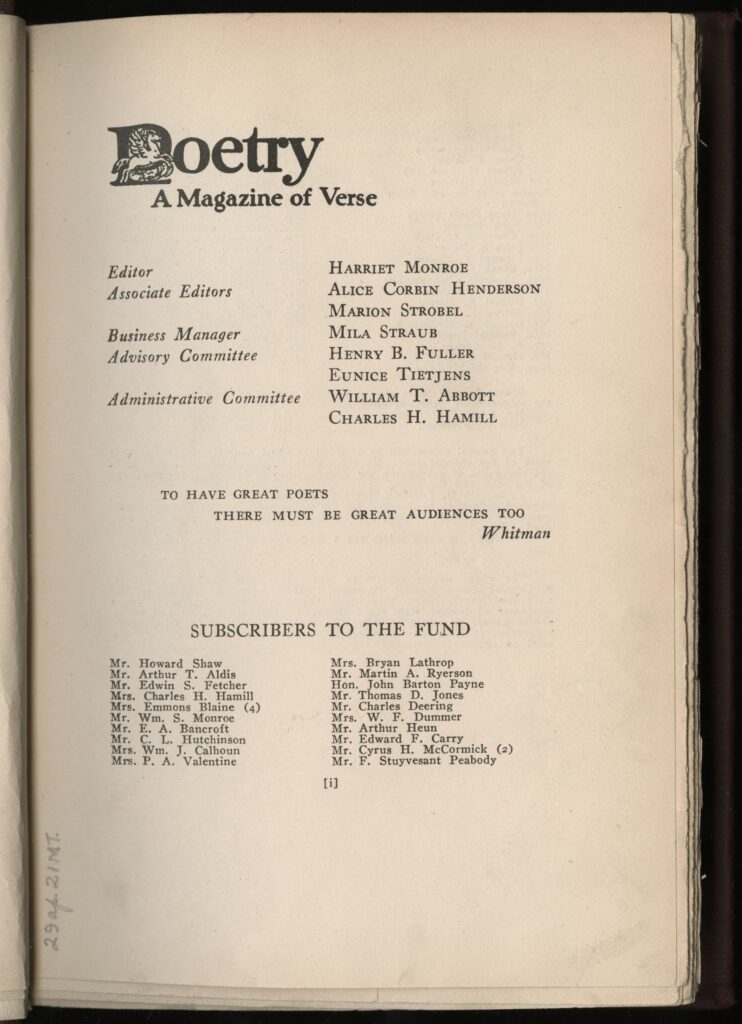

Another important and lasting literary movement in Chicago also emerged out of Harriet Monroe’s Poetry magazine, which began publishing in 1912 as a periodical of free verse. Monroe was an avid supporter of modernism and spent many years working as a freelance art critic. When the Armory Show of 1913 came to the Art Institute of Chicago (drawing double the number of visitors than in New York), Monroe was one of the few voices of support for the show’s explosive, radical works by the European and American avant-garde, from those by Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Gauguin to examples by the Fauves and Cubists. As an editor of Poetry, Monroe cultivated an eye for the modern, selecting such poems as T. S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” Wallace Stevens’s “Sunday Morning,” Carl Sandburg’s “Chicago,” H. D.’s “Hermes of the Ways,” and Ezra Pound’s early cantos. International in scope, Monroe also promoted poets of the Midwest, including Sandburg, Vachel Lindsay, and Edgar Lee Masters—who scorned ornate language, and emphasized poetry’s oral qualities, which suited their work for large-scale performance. Indeed, Monroe aimed to build audiences for modernist poetry, just as her friend Arthur Jerome Eddy—a lawyer and art collector—aimed to build an audience for modernist art.

Selection: Poetry: A Magazine of Verse, “Subscribers to the Fund,” i-ii (March 1921).

The first book about modern art in America, Cubists and Post-Impressionism (1916), was written by Eddy, a Chicago lawyer and art collector. Written in a deliberately non-technical style, the book explained the theoretical underpinnings of modernist art, and drew deeply from Eddy’s own extensive collection and correspondence with artists.

Selection: Arthur Jerome Eddy, Cubists and Postimpressionism, 4-6 (1914).

Questions to Consider

- Consider the motto that Margaret Anderson affixed on the cover of the Little Review, “Making No Compromise with the Public Taste.” How does this epigraph compare with the quotation from Walt Whitman that Harriet Monroe printed in Poetry magazine, “To have great poets there must be great audiences too”?

- In Sherwood Anderson’s newspaper advertisement for the Dill Pickle Club, who does he suggest should come to the Dill Pickle? How does nightlife at the Dill Pickle contrast with other aspects of Chicago?

- Polish-born, Chicago artist Stanislaw Szukalski created the striking woodcut of the Dill Pickle’s founder, Jack Jones. How would the advertisement be different if the image of Jones was a photograph?

- In this passage from Arthur Jerome Eddy’s Cubists and Post-Impressionism, how does Eddy describe the relationship between the collector and the works of art in his collection? Who does he think modern art is for?

- Several works by the cubist painter Amadeo de Sousa-Cardoza appeared in the 1913 Armory Show, and were purchased by Arthur Jerome Eddy. A reproduction of Sousa-Cardoza’s Marine appears in Cubists and Post-Impressionism, one of the book’s twenty-two illustrations in color and forty-seven illustrations in black and white. What does Arthur Jerome Eddy suggest is the appropriate response to a cubist work like Marine?

Form

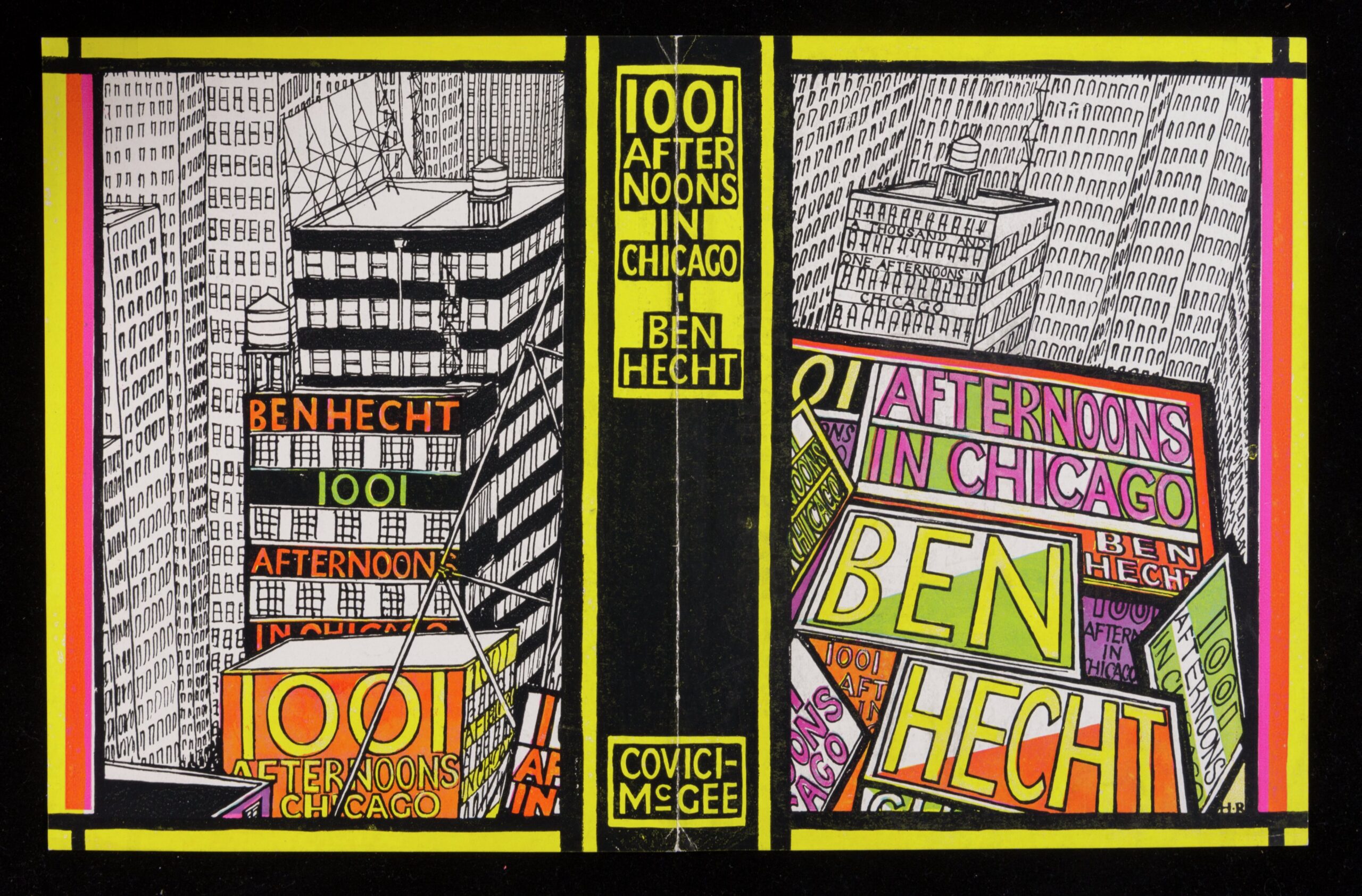

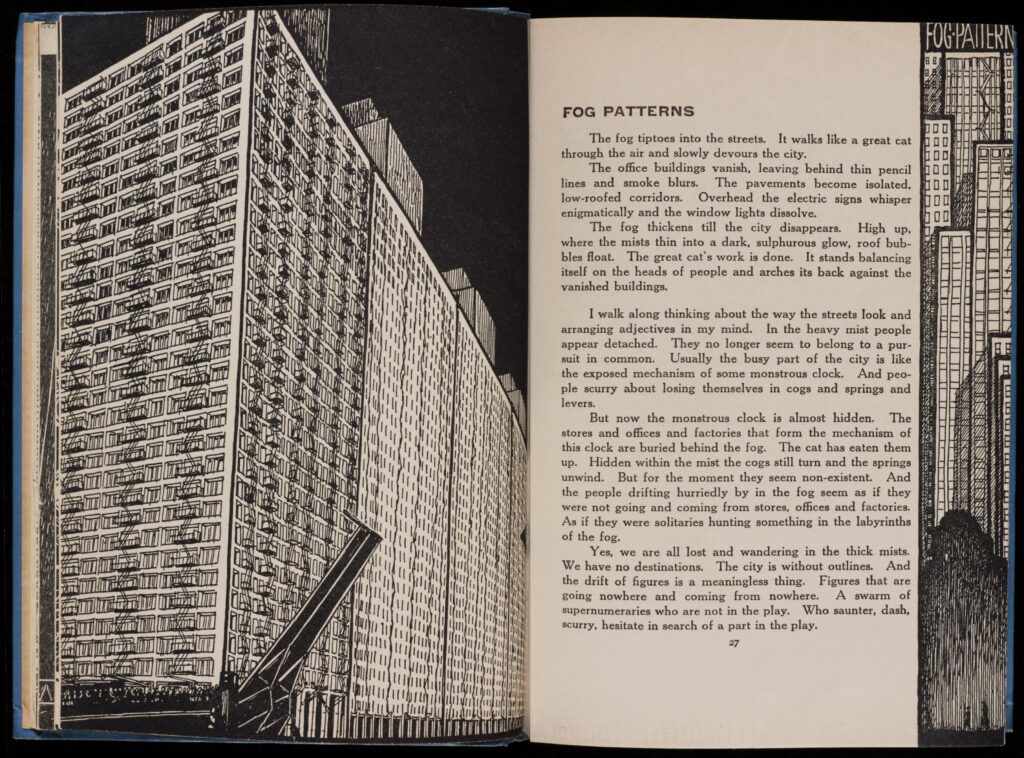

Modernism was characterized by an unprecedented experimentation with literary and artistic form. Often with playfulness and irony, modernist writers broke with poetic meter and narrative conventions, including the idea that a story’s structure should include a beginning, middle, and end. Plotlessness was modernism’s great revolution. Artists and writers also experimented with how to represent subjective consciousness, including the non-linear experience of time, the work of memory, and the expansion and contraction of moments. Multiple perspectives, fragmentation, pastiche, and allusion characterize some of the most well known literature of the modernist movement. If these techniques produced styles that were famously difficult, then in Chicago modernism was tempered by a desire to reach the common reader. Carl Sandburg, for instance, forged an accessible modernism that was partly informed by his leftist political impulses. He not only wanted to write about the working classes, he also wanted to be read by them. For many Chicago writers, journalism was good training ground, a daily discourse of words composed under deadline. Nearly every writer in Chicago had some experience with newspapers. Other modernist metropoles like New York, London, and Paris, were also centers of journalistic culture, but Chicago’s newspapers functioned as an incubator for the literary when there were not always other sites. Perhaps the best material came from Ben Hecht, who captured Chicago’s multitudinous array like a young urban flaneur—from jazz-age corruption to back alley slums—in his 1921 vignettes for the Chicago Daily News, published in a collection titled 1,001 Afternoons in Chicago. To put it another way, journalism was not always modernism’s obvious fall guy: newspapers were not the commercial sell-out against which “real” literary pursuits were measured.

Selection: Ben Hecht, 1,001 Afternoons in Chicago, 26-30 (1931).

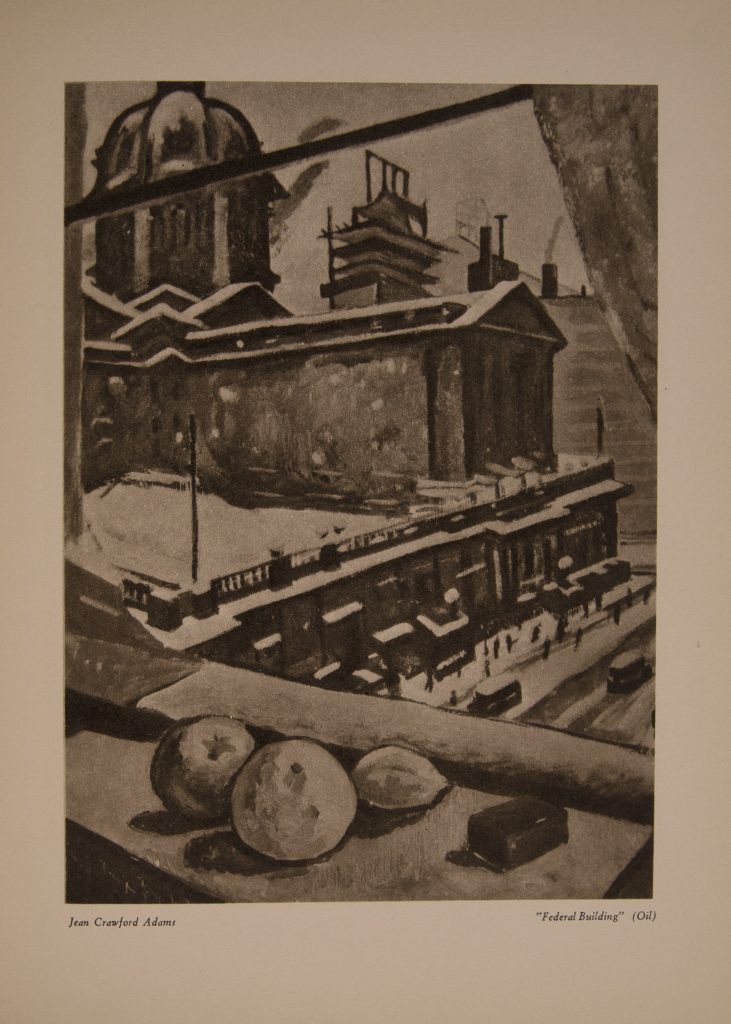

The documents in this section include one of Hecht’s newspaper columns included in 1,001 Afternoons in Chicago, and a poem by Eunice Tietjens, who also worked as a journalist. The last items is from J. Z. Jacobson’s Art of Today, Chicago, 1933, a groundbreaking compilation of work by fifty-two Chicago artists—over half of whom were recent immigrants from Europe—which was published to coincide with the 1933 Century of Progress Fair in Chicago.

Selection: J. Z. Jacobson, Art of Today, Chicago, 1933, “Jean Crawford Adams” (1932).

Questions to Consider

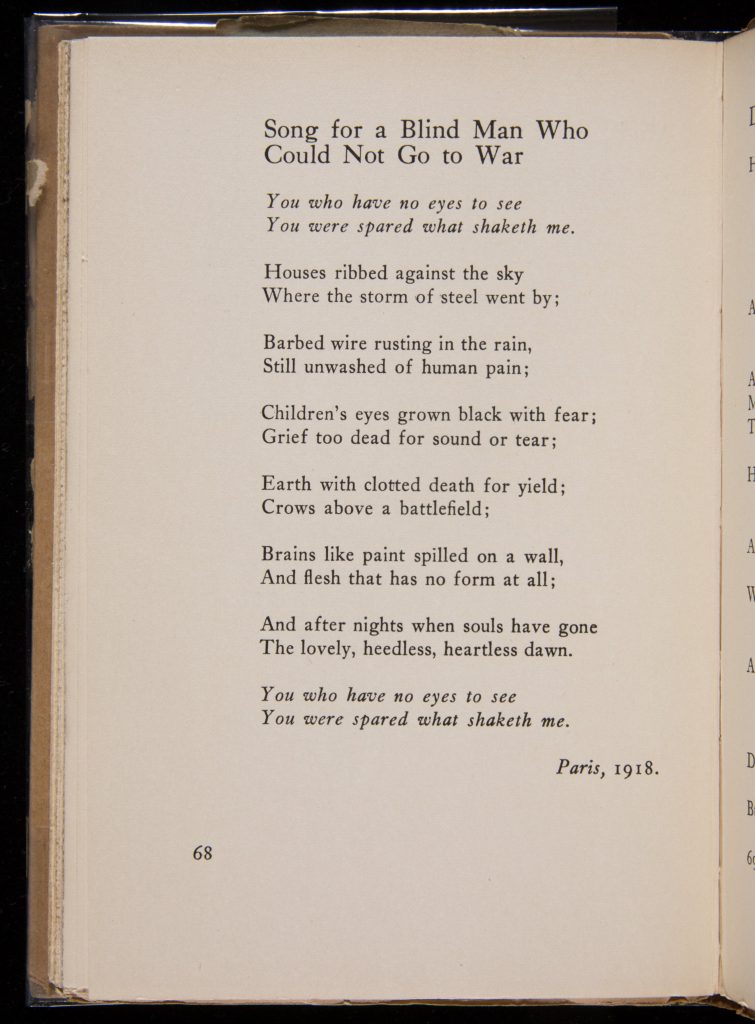

- In the poem by Eunice Tietjens, “Song for a Blind Man Who Could Not Go to War,” what has the speaker seen that the blind man cannot see?

- Consider some of the metaphors in “Song for a Blind Man Who Could Not Go to War,” especially language that describes bodies on the battlefield. What language resonates most powerfully with you?

- Why do you think Eunice Tietjens decided to write this poem in rhyming couplets?

- Consider Ben Hecht’s narrator in “Fog Patterns.” What kind of person is he? What effect does the fog have on his sense of downtown Chicago? How does it make the people of the city behave towards one another?

- Why do you think Hecht’s piece is called “Fog Patterns” rather than just “Fog”? How do the images by Herman Rosse contribute to the writing?

- The advertisement for 1001 Afternoons in Chicago states that the “daring design and heroic coloring” is a “departure” from conventional book making. What do you think is daring?

- In her artist’s statement included in Art of Today, Chicago, 1933, how does Jean Crawford Adams explain Chicago’s influence upon her aesthetic sensibility? Why do you think Chicago is “genuinely and distinctively American” to her?

Further Reading

Butcher, Fanny. Many Lives—One Love. New York: Harper & Row, 1972.

Bone, Robert, and Richard Courage. The Muse in Bronzeville: African American Creative Expression in Chicago, 1932-1950. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2011.

Hecht, Ben. Charlie: The Improbable Life and Times of Charles MacArthur. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1957.

Olson, Liesl. Chicago Renaissance: Literature and Visual Art in the Midwest Metropolis. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017.

Smith, Carl. Chicago and the American Literary Imagination 1880-1920. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984.

Virginia Woolf, “Professions for Women,” Death of the Moth and other Essays. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974.