Introduction

In the popular imagination of what constitutes the Midwest, the African American presence is often obscured or missing altogether. When the African American presence in the Midwest does get mentioned, more often than not it’s focused on representing black folks as a problem to be solved. Therefore, this digital collection offers a corrective on two separate historical accounts. Between the tendencies of being absent from the narrative or identified as a “problem,” we can locate black Midwesterners—and let their words and experiences speak for themselves. When we do so, the themes of race, respectability, and resilience emerge.

The Midwest is not, nor has it ever been, a place devoid of racial conflict; however, these documents at times point to the Midwest as occupying a middle ground in race relations. For example, the Missouri Compromise placed the Midwest in the “middle” of the controversy over slavery. Culturally and socially, the Midwest also functioned as a liminal space between slavery and true freedom. While the Midwest has been as mired in racial hostilities as any region in the U.S., at times, these documents present racial understandings, interactions, and possibilities, where something new (and perhaps unexpected) was able to thrive and take shape.

How African Americans both navigate and forge this new cultural and racial terrain can be understood through the values they articulate—that of respectability and resilience. While it is tempting to see respectability politics and the need to be resilient in the face of adversity as additional forms of racial oppression, the personal and political agency of African Americans in articulating these values as a means to subvert stereotypes, subjugation, and racial barriers is an important aspect of understanding the experiences of African Americans in the Midwest. The documents in this collection span a great deal of time and distance; nonetheless there are generalizations that can be made about the Midwestern experiences and identities of African Americans.

Questions to Consider While Exploring the Collection:

- In what ways do African Americans featured in this collection articulate a vision of what the Midwest is, or what it can be?

- What measures do African Americans take to shape the region according to their own designs, hopes, and needs?

- How do African Americans in the Midwest experience themselves as in the middle of Southern and coastal (East and West) African American experiences?

- Where are the moments that the idea of white supremacy seems to destabilize or weaken in these documents? In what ways do African Americans exploit these opportunities in their own self-interests?

- In what ways do white Midwesterners resist the new racial paradigm that African Americans seek to create?

Words to Define:

Respectability Politics: Attempts by marginalized groups to demonstrate that their social values are continuous and compatible with mainstream values, rather than challenging the mainstream or its failure to accept difference.

Resilience: The capacity to recover from difficulties; toughness.

Agency: The capacity, condition, or state of acting powerfully or of exerting power.

Manumitted: Released from slavery; set free.

Disdain: The feeling that someone or something is unworthy of one’s consideration or respect; contempt.

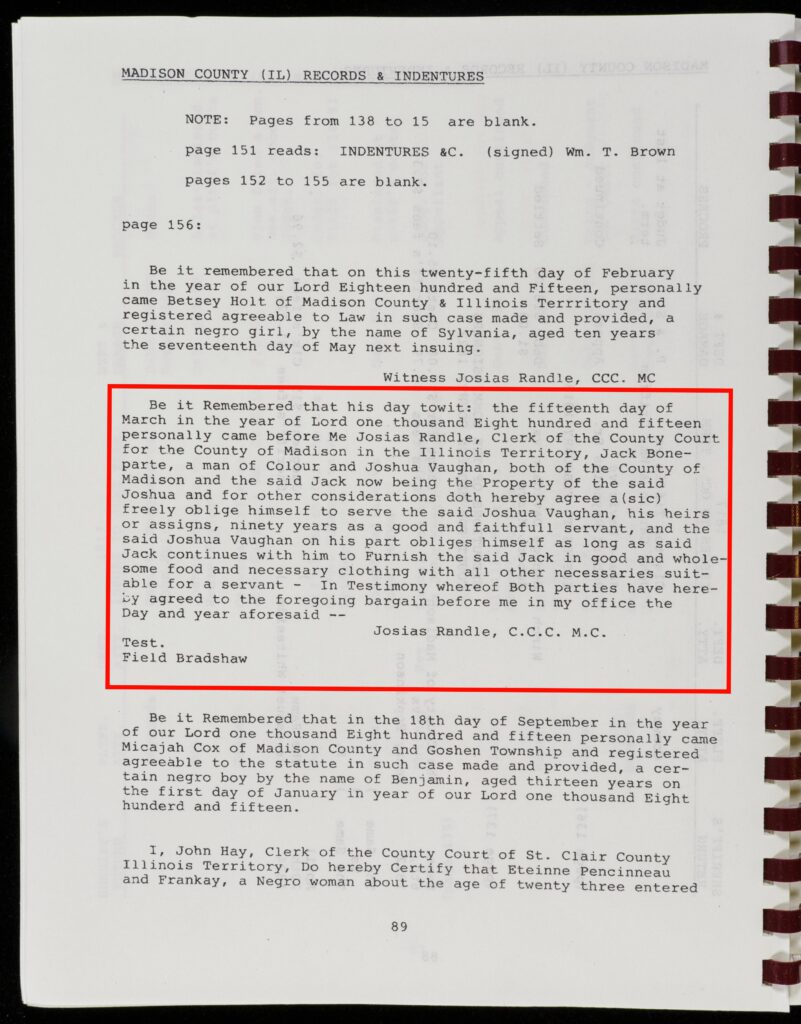

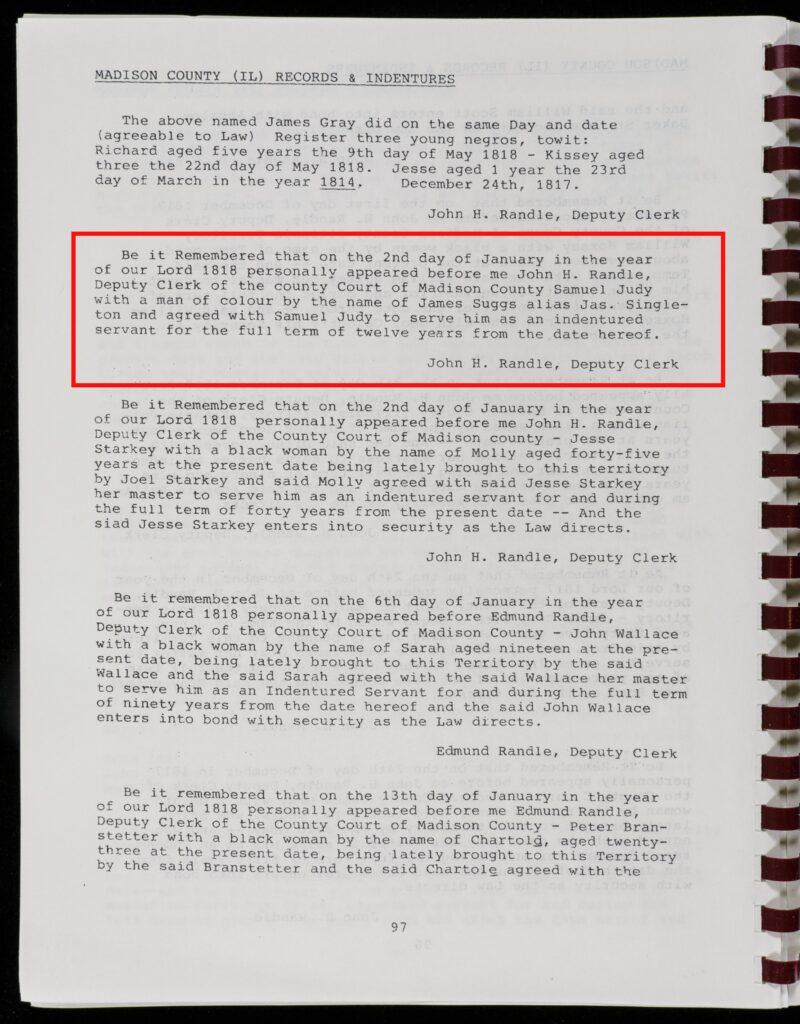

Forging New Identities: Free, Enslaved, and Indentured African Americans in Illinois, 1805-1826

The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 outlawed slavery in the land that would later become the State of Illinois. Some white enslavers tried to get around the new law by re-registering their slaves as indentured servants. Indentured servitude is a kind of unfree labor different from slavery. An indentured servant signs or is forced into a contract to work for an employer for a fixed time, sometimes in exchange for passage to a new place. Unlike an enslaved person, an indentured servant will eventually be freed and may be able to negotiate the terms of their servitude. In parts of the Northwest Territory, indentured servitude became an informal slave trade. Owners sometimes sold their “indentured servants” or attempted to extend contracts to cover servants’ children, just as an enslaved woman’s children were automatically enslaved themselves.

Other enslavers manumitted – or freed – their slaves after the Ordinance. Ultimately, African Americans took advantage of this new ordinance, to gain some control over their lives and exercise their personal agency. As examples of agency, we have records of freed and enslaved people refusing to enter indentured servitude, negotiating their contract, or registering their children as free.

Selections from the Illinois, Madison County, Court Records, 1813-1818 and Indenture Records, 1805-1826: Register of Slaves, Indentured Servants & Free Persons of Colour. Edited by Peggy Lathrop Sapp. Springfield, IL: FolkWorks Research, 1993.

- Image 1a – Page 89: Joshua Vaughan and Jack Boneparte

- Image 1b – Page 97: Samuel Judy and James Suggs Singleton

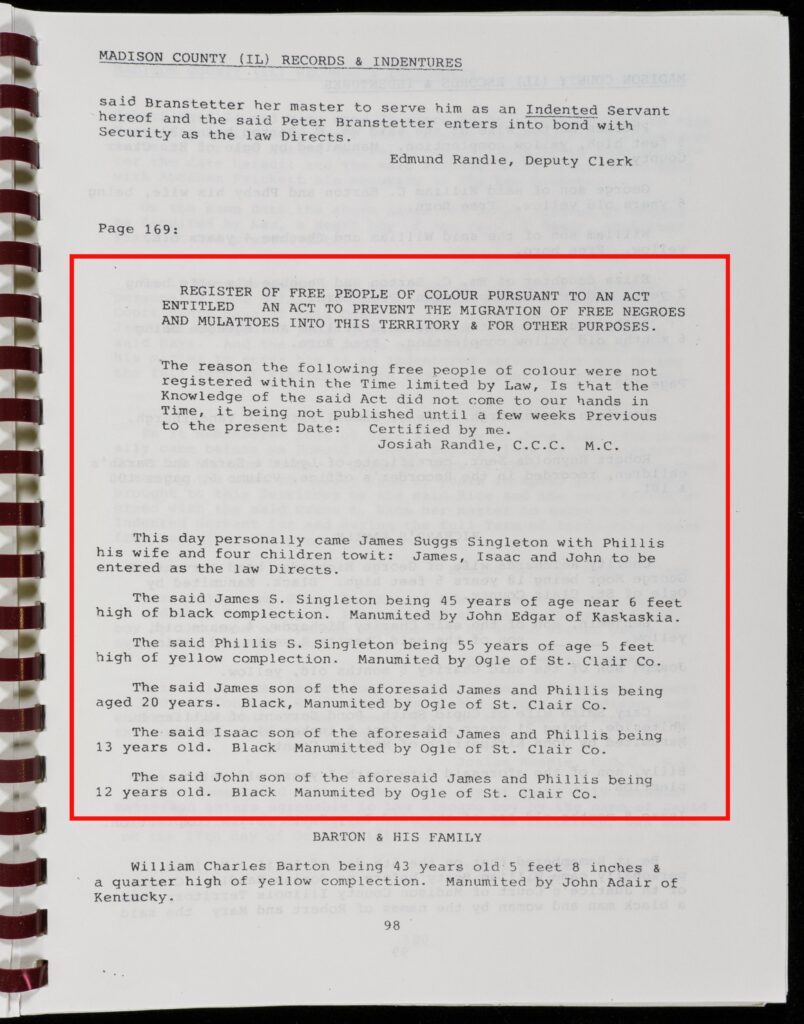

- Image 1c – Page 98: James Suggs Singleton and family

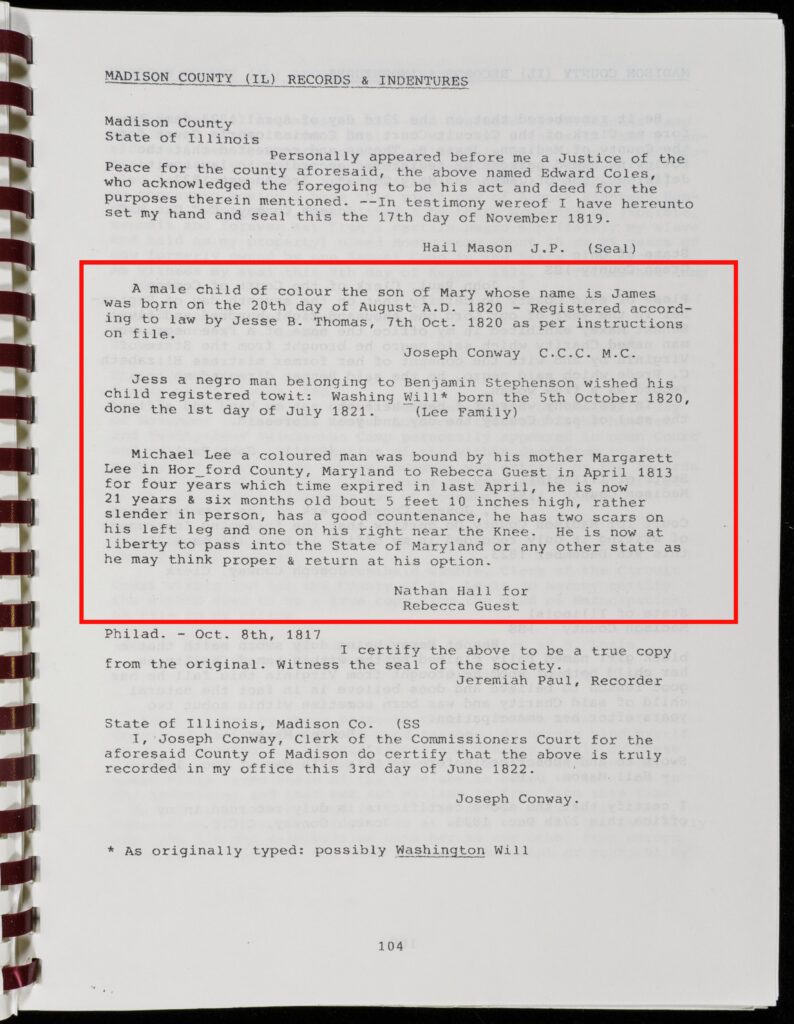

- Image 1d – Page 104: Parents registering children, Michael Lee

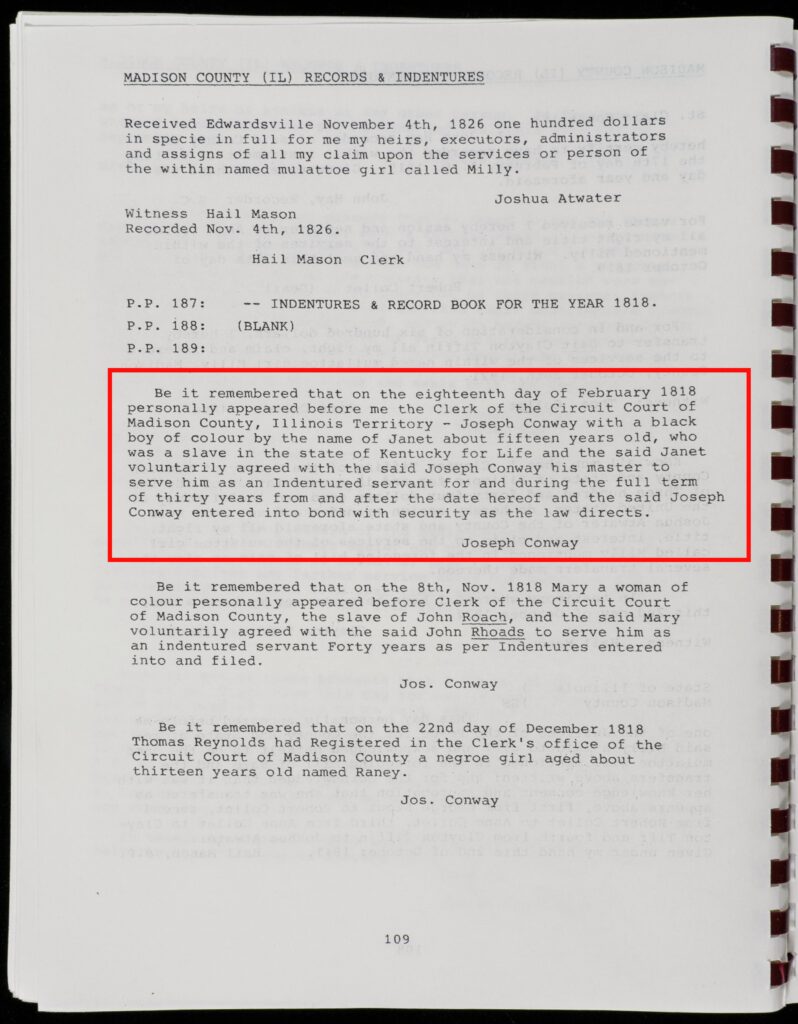

- Image 1e – Page 109: Joseph Conway and Janet

Image 1a – Page 89: Joshua Vaughan and Jack Boneparte

Joshua Vaughan petitioned to commit the enslaved Jack Boneparte and his heirs to indentured servitude for ninety years. (1815)

Page 89 Guiding Questions:

- What did Jack Boneparte agree to, according to this petition?

- What did Joshua Vaughan agree to, according to this petition?

- There are recorded instances in which enslaved men and women refused to agree to indentured servitude when entering the Northwest Territories. What type of agency do you think Jack had in negotiating the terms of his “service?”

- What options do you think Jack may have had?

Image 1b – Page 97: Samuel Judy and James Suggs Singleton

Samuel Judy petitioned to have his enslaved worker James Suggs Singleton’s status converted to an indentured servant for a period of twelve years. (1815)

Page 97 Guiding Questions:

- How does James Suggs Singleton negotiate the terms of his indentured servitude? How are his tactics similar to or different from Jack Boneparte’s?

- How do you see agency working in both accounts?

- What conditions might have resulted in Singleton’s shorter, twelve-year period of servitude? Find evidence in the text.

- How might other African Americans brought into the Midwestern region during this time period have negotiated the conditions of their work and advocated for their own freedom?

Image 1c – Page 98: James Suggs Singleton and family

On December 8, 1813, the Illinois Territory passed an act to prevent free people of color and “mulattoes” (people of mixed race) from entering the territory. Free people of color living in the territory had to register in order to remain. This selection registers James Suggs Singleton and his family. In a note, the clerk explains that the family was registered late because news of the law had not reached Madison county.

Page 98 Guiding Questions:

- The Singletons’ registration proves that they lived in the territory and were manumitted from various enslavers prior to 1813. Therefore, James Suggs Singleton was presumably free in 1815 when he entered into indentured servitude, as recorded on page 97. Based on the two entries, what can we conclude about Singleton’s situation between 1813 and 1815? Why might he be willing go from freedom to indentured servitude?

- Where can you see Singleton’s personal agency at work?

Image 1d – Page 104: Parents registering children, Michael Lee

African American parents registered their free-born children after the 1813 law. Doing so ensured the children could stay in the Illinois Territory and created a legal record of their freedom.

Page 104 Guiding Questions:

- Why would it be important to legally recognize the freedom of African -American children? What does this need suggest about slavery in the territories at this time?

- What does Michael Lee’s situation demonstrate about slavery and servitude in Illinois?

- Why is Rebecca Guest’s testimony that he “has a good countenance” important? What does she mean by this remark, and what is the potential significance?

- How is Guest’s description an example of respectability politics, if at all? Discuss some examples to back up your impression of this passage.

Image 1e – Page 109: Joseph Conway and Janet

Joseph Conway registered Janet, who had been enslaved in Kentucky, as his indentured servant for thirty years.

Page 109 Guiding Questions:

- Do you believe that Janet voluntarily became the indentured servant of Joseph Conway? If so, what evidence suggests the decision to do so?

- Why do you think Conway’s consent is stated in the record?

- Given the historical evidence available in this passage, what possible agency might exist for Janet in these circumstances?

New Racial Terrains: Monroe County, Iowa

Buxton, Iowa was a majority African American, multi-ethnic mining town. By all accounts, Ben Buxton, the president of Consolidation Coal Company, ran a company town in which there was equality among whites and blacks in housing, employment, and education. African Americans came from coal mining areas of Virginia and West Virginia seeking work and the freedom Buxton offered. The town eventually folded along with its coal reserves, but its existence is an example of the complexity of Midwestern race relations and the ways African Americans took advantage of that complexity to achieve their collective goals.

Selections below from the Monroe County History by the Writers’ Program of the Works Projects Administration in the State of Iowa. Des Moines, 1940.

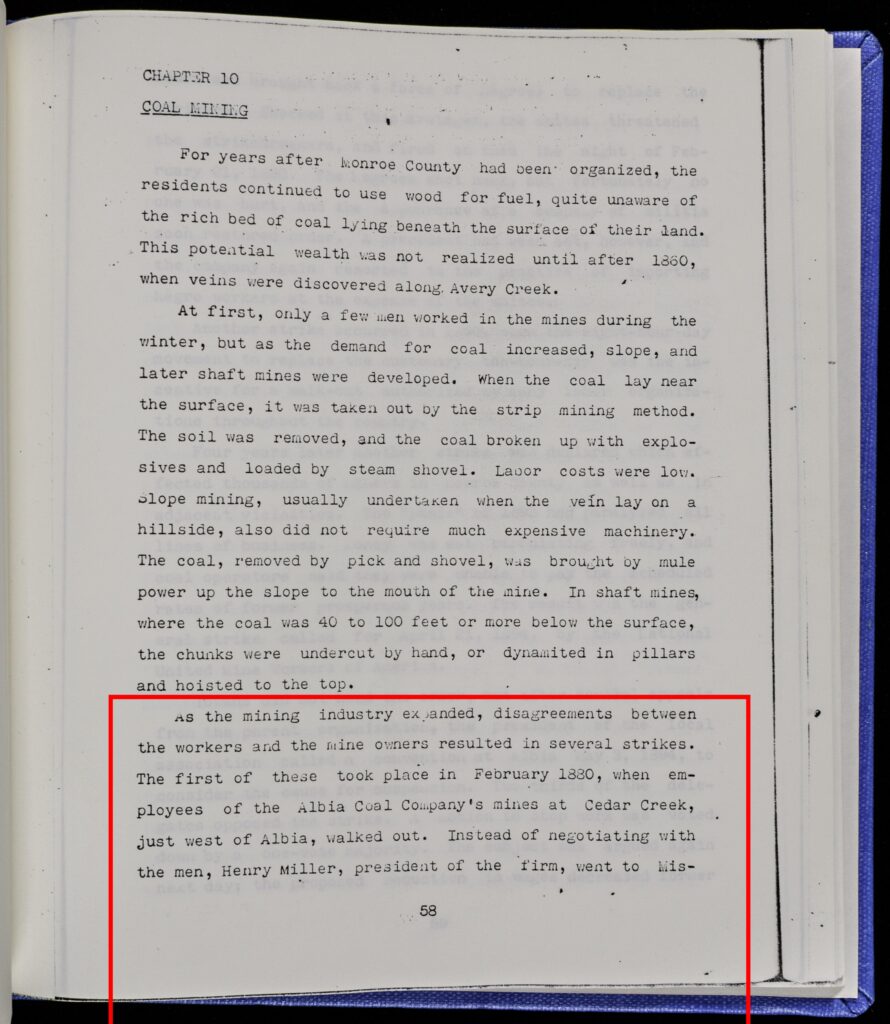

- Image 1a – Pages 58-59: The 1880 strike at Albia Coal Company’s Cedar Creek Mines

- Image 1b – Pages 60-61: Brooker T. Washington’s 1902 speech at Buxton

Image 1a – Pages 58-59: The 1880 strike at Albia Coal Company’s Cedar Creek Mines

Image 1b – Pages 60-61: Brooker T. Washington’s 1902 speech at Buxton

Guiding Questions:

- Why might black workers have been willing to work as strikebreakers?

- How do their actions point to a sense of resilience?

- How might the author’s use of the word “imported” shape the reader’s perspectives on the migration of African Americans to Buxton and their enactment of agency before and after the move?

- Do you trust the author’s take on Booker T. Washington’s speech? In what ways might this speech (as it is presented) serve the interests of white Midwesterners?

- Assuming Washington’s words are well-represented, in what ways might he be engaging in respectability politics? How might his idea of “self-control” support or limit the efforts of African Americans seeking racial justice?

- What expectations do you think that African Americans coming to Buxton brought with them about their possible futures in Iowa?

- As African Americans left Buxton for other areas, what expectations and practices do you think they took with them?

A Hundred Year Journal: Black Residents in Stephenson County, Illinois

The first African American to arrive in Stephenson County, Illinois came from Virginia in 1832. She was a free woman who stowed away with a white family traveling to Wisconsin, after freeing their enslaved workers had made them unpopular in their original home. Unfortunately, she died along the way and was buried near Cedarville, Illinois—free territory.

Over the years, other African Americans sought freedom and justice in what would become known as the Midwest. After the Civil War, small numbers of emancipated people moved north to places like Stephenson County.

Selection from A Hundred Year Journal: A Pictorial History of the Early Black Settlers of Stephenson County, Illinois, 1830-1930 by Joyce Salter Johnson. Freeport, IL, Stephenson County Historical Society, 2010. Section 3: Black Residents in Stephen County, Illinois

Guiding Questions:

- What kinds of jobs did emancipated African Americans hold in Stephenson County? How was this work similar to or different from work they likely did while enslaved? If you identify migrants’ agency in their new positions, what does it look like within their experiences as slaves?

- How would the search for a better life have involved different considerations for African Americans than for white migrants with the same goal?

A Hundred Year Journal: World War I

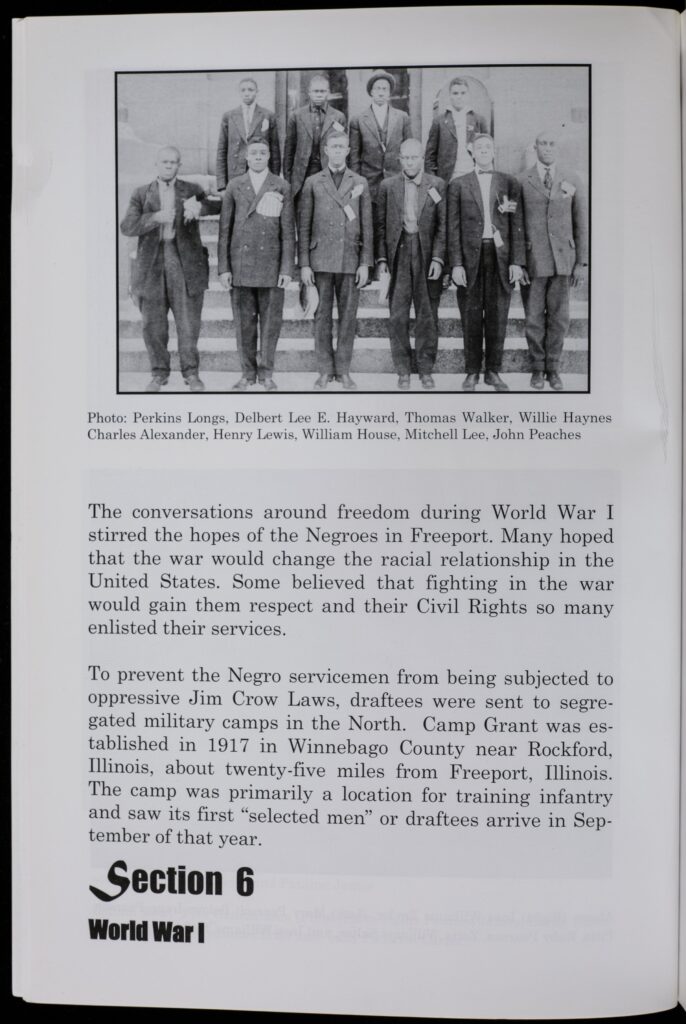

When historical moments of change presented themselves, African American men and women took the opportunity to carve out new racial possibilities. World War I was such a moment. Black men served in segregated military units, which brought them into contact with new places and people. For some, it represented an opportunity to demonstrate their bravery and loyalty. Black women worked in factories, became nurses, and mobilized support for their communities. Some women joined the Red Cross in the hopes of desegregating the Army and Navy Nurse Corps. They succeeded in 1917. Others embraced the United States’ rhetoric of freedom and justice, protested lynching, and demanded that the suffrage movement include women of color.

Selection from A Hundred Year Journal: A Pictorial History of the Early Black Settlers of Stephenson County, Illinois, 1830-1930 by Joyce Salter Johnson. Freeport, IL, Stephenson County Historical Society, 2010. Section 6: World War 1

Guiding Questions:

- Why do you think so many African Americans were willing to participate in the war effort, even though the U.S. denied them full equality?

- Whose decision do you think it was to spare Black recruits from the oppressive Jim Crow Laws? How do you think those same people justified requiring them to serve in segregated camps in the North?

- How does African Americans’ participation in the war demonstrate their resilience in the face of racial discrimination? In what ways does it employ the tactics of “respectability politics”?

A Hundred Year Journal: Freeport, Illinois

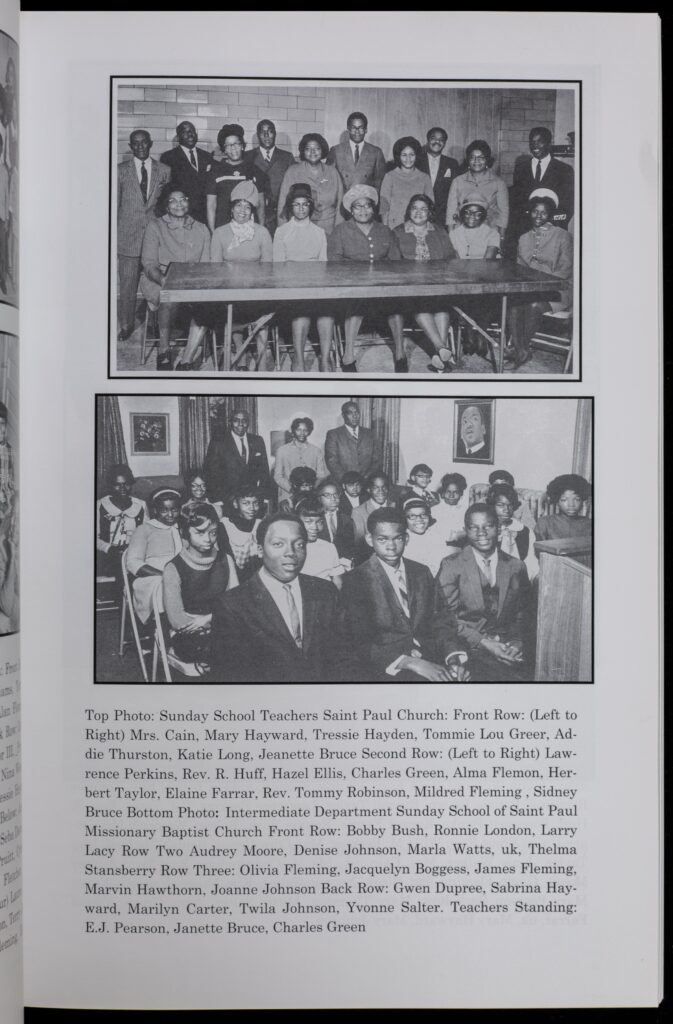

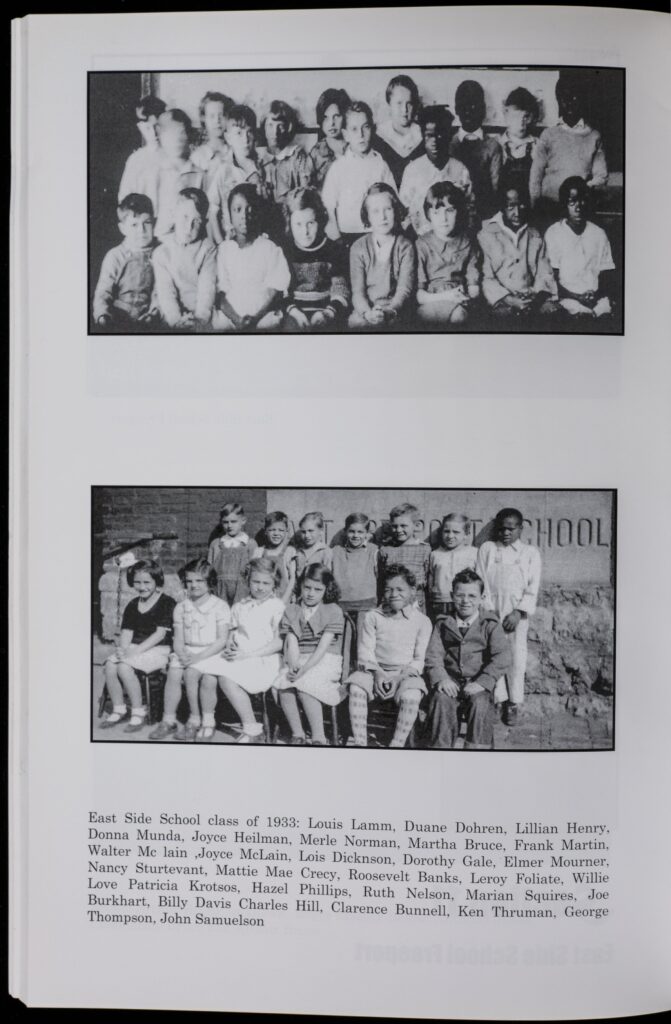

Thousands of African Americans moved north, especially to cities, during and after the First World War. This massive population shift is called the Great Migration. New arrivals in towns like Freeport built or expanded black churches, schools, and community groups. Migrants from the South were used to rural, agricultural ways of life. Moving north, they both adapted to new routines and incorporated parts of their lives – like food, music, and language – into northern culture.

Selections from A Hundred Year Journal: A Pictorial History of the Early Black Settlers of Stephenson County, Illinois, 1830-1930 by Joyce Salter Johnson. Freeport, IL, Stephenson County Historical Society, 2010.

Image 1a – Section 7: The Great Migration

Image 1b – Sunday school teachers and students of St. Paul Missionary Baptist Church

Image 1c – East Side School class of 1933

Guiding Questions:

- After studying images 1b and 1c side by side, what do you notice?

- What possible information do they present about segregation (or the lack thereof) in small Midwestern towns like Freeport?

- Why do you think schools weren’t segregated, but churches were? Why might African Americans opt for segregated churches, but advocate for integrated schools?

- With the above question in mind, who do you think made the decisions to segregate or integrate social spaces? How do these images provide clues to this decision-making process within African American communities?

Black Eden: Idlewild, Michigan

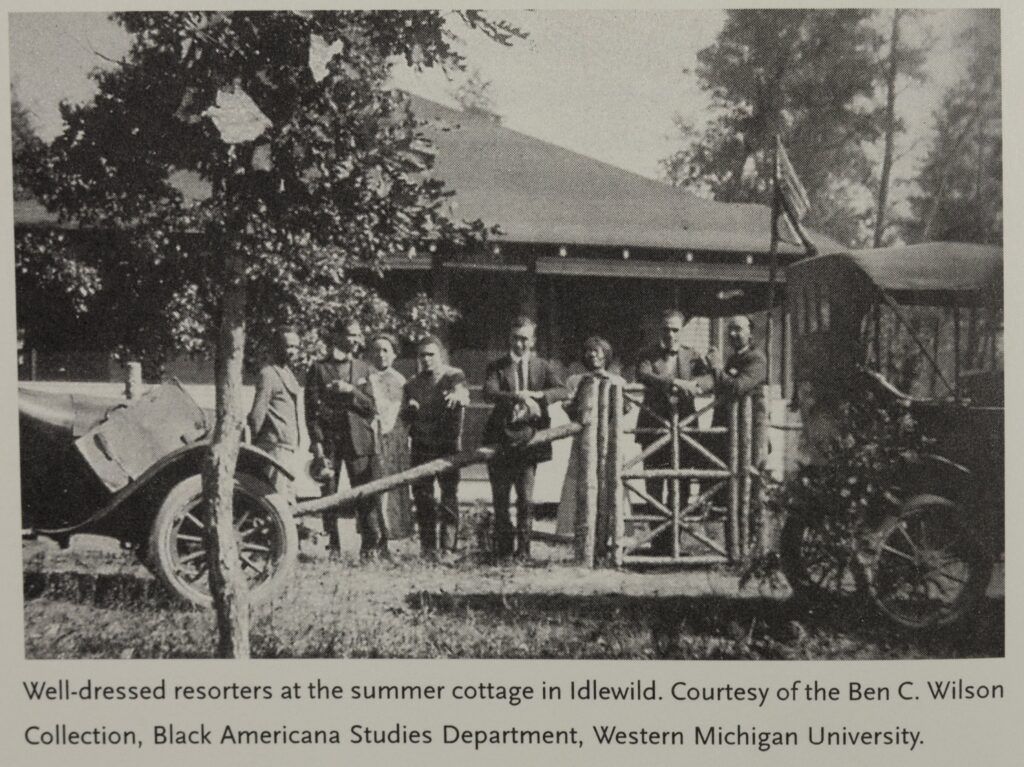

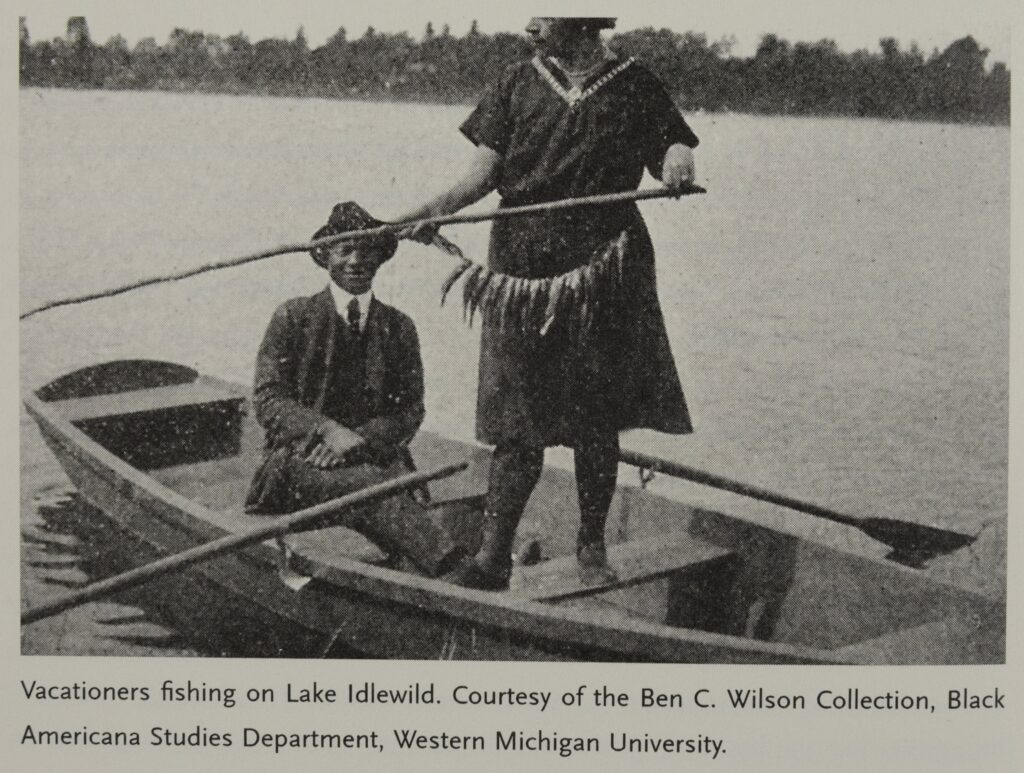

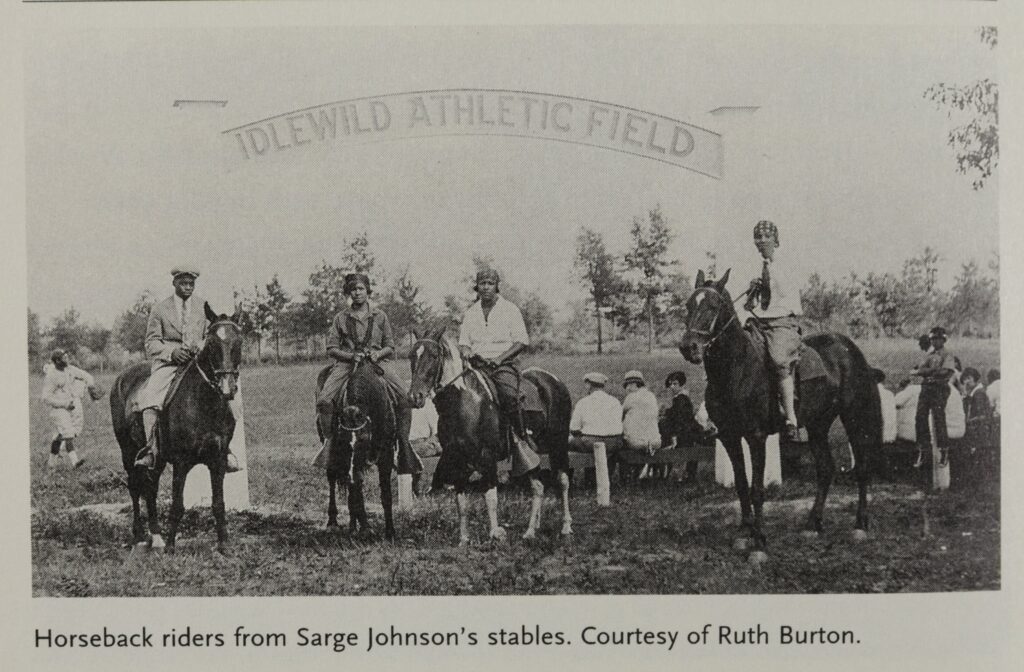

Idlewild was established as a resort community in the state of Michigan. It was founded by affluent African Americans in response to their experience of segregation and discrimination in white social spaces.

Selections from Idlewild: The Black Eden of Michigan by Ronald Jemal Stephens. Chicago, Arcadia Publishers, 2001.

Image 1a – Page 48: “Well-dressed resorters”

Image 1b -Page 104: “Vacationers Fishing on Lake Idlewild”

Image 1c – Page 106: “Horseback riders”

Guiding Questions:

- Why do you think the first caption states that the vacationers are “well-dressed?” How does this description relate to the idea of respectability politics?

- Aside from the vacationers’ clothes, what other examples do you see in the pictures that reflect notions of respectability?

- In what ways do you think the desire to appear respectable influenced African Americans’ cultural expressions (and practices as consumers)? What other values or concerns might have influenced African Americans’ clothing choices?

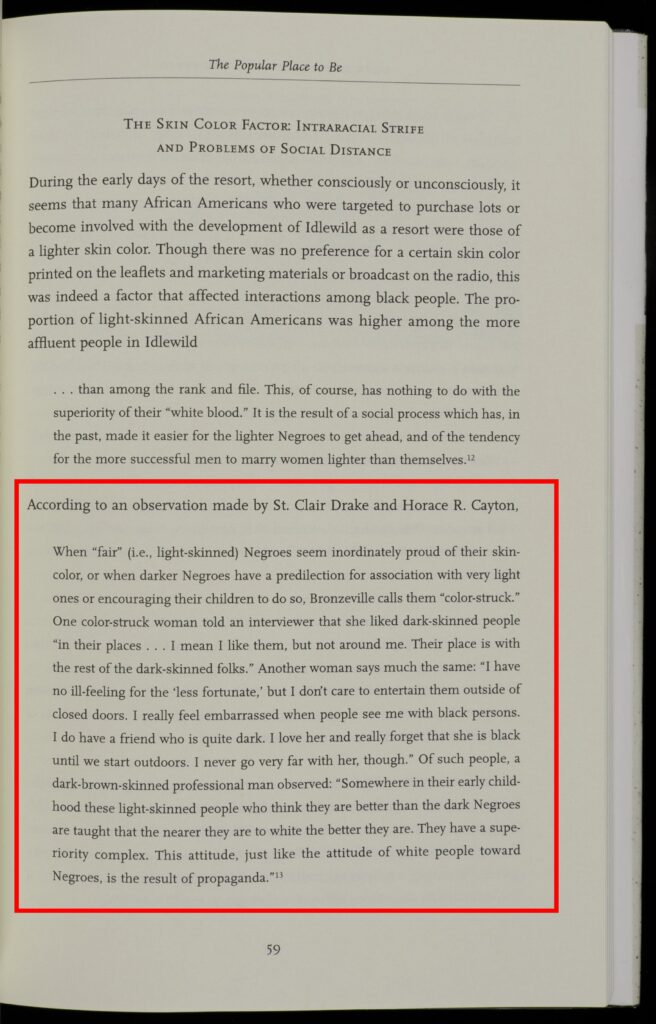

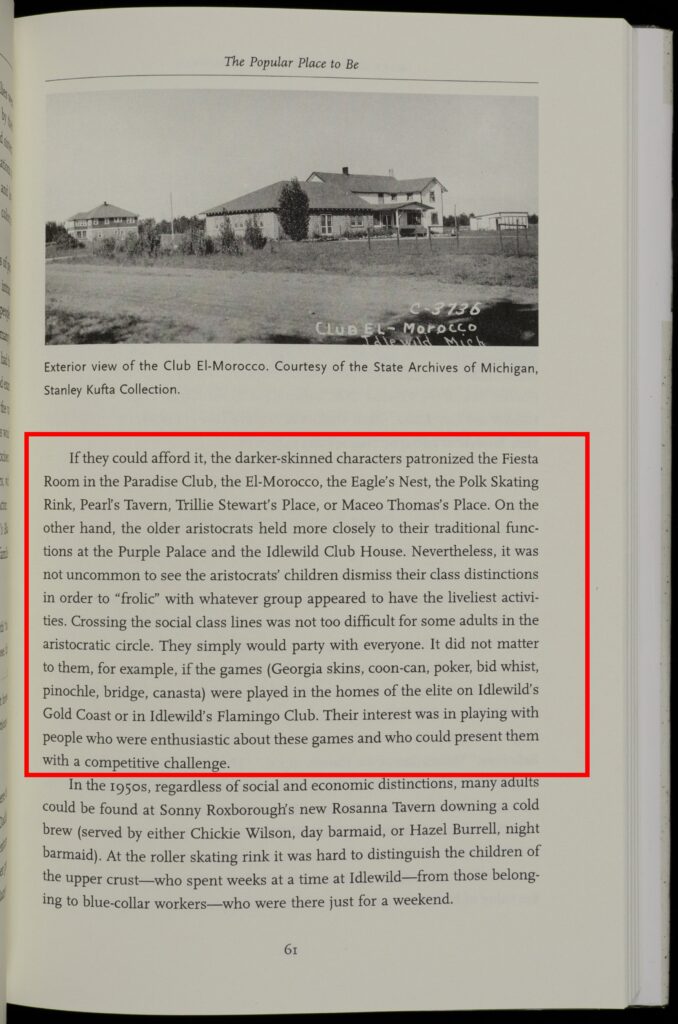

Black Eden: Skin Color Politics

One consequence of racism and the notion of white supremacy is the internalization and reinforcement of these belief systems within African American communities. These selections from Stephens’ Idlewild discuss skin color politics, and opinions within African American communities about the meaning and value of skin color.

At Idlewild, skin color politics connected to class politics, because lighter-skinned members often enjoyed more privilege—resulting in greater wealth and social mobility. Sources that document assumptions made about skin color help us to understand the complexities of social and political agency. For instance, on the one hand, African Americans at Idlewild used their agency to protest the wider order of white supremacy; on the other, their participation in skin politics supported those same values.

Selections from Idlewild: The Black Eden of Michigan by Ronald Jemal Stephens. Chicago, Arcadia Publishers, 2001.

Image 1a – Page 59: Observations of St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton

Image 1b – Page 60: Quote from Lawrence Otis Graham

Image 1c – Page 61: Children crossing class lines

Guiding Questions:

- Why do you think skin color politics became so influential in places like Idlewild?

- In what ways was skin color associated with respectability within this African American community?

- What specific evidence in these sources points to a relationship between skin color and respectability?

Black Eden: Integration

In these selections, Ronald Jemal Stephens argues that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 had negative consequences for Idlewild and other Black spaces. The Act outlawed segregation in public places, integrated public schools, and prohibited racial discrimination in employment. Instead of supporting African American communities or bringing white people into Black spaces, the Act encouraged African Americans to participate in white institutions and abandon black social spaces.

Selections from Idlewild: The Black Eden of Michigan by Ronald Jemal Stephens. Chicago, Arcadia Publishers, 2001.

Image 1a -Page 130: Economic consequences

Image 1b – Page 135: Integration and the Civil Rights Movement

Guiding Questions:

- Why do you think many African Americans left African American social spaces, like Idlewild, after the end of segregation?

- In what ways did white businesses benefit from desegregation?

- How could the decline of Black businesses as a result of desegregation be considered ironic?

- How is the shift towards white spaces an example of the resilience of African American communities? Of the influence of respectability politics? Something else?

American Daughter: Foreign Ideas of Race

Born in Des Moines, Iowa, in 1905, Era Bell Thompson spent most of her life in the Midwest. As a small child she lived in North Dakota and later attended the University of North Dakota, Morningside College in Iowa, and Northwestern University in Illinois. She eventually moved to Chicago and worked as a journalist. Her autobiography, American Daughter, was published in 1946. Her second book, Africa, Land of My Fathers, was published in 1954. As a journalist and author Thompson promoted racial and gender equality.

Selections from American Daughter by Era Bell Thompson. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1946.

Pages 26-27: A white Norwegian couple visited the Thompson family on their North Dakota farm during Thompson’s childhood.

Guiding Questions:

- How does the experience of having white neighbors who were born outside of the U.S. shape Thompson’s experience in the Midwest?

- How do their “foreign” understandings of race create the possibility for new racial interactions?

American Daughter: Race and Employment

Because she grew up in a white town in rural North Dakota, Era Bell Thompson did not have much experience in predominantly black communities. In these passages from her autobiography American Daughter, Thompson recounts how some of her perceptions of race were shaped by her experiences living in Chicago.

Selections from American Daughter by Era Bell Thompson. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1946.

Image 1a – Page 182: Thompson reflects on her views of African Americans from the South.

Image 1b – Page 212: Thompson describes an interaction with a white man from Oklahoma.

Guiding Questions:

- How does Era Bell Thompson’s disdain for less educated African Americans reflect the notion of respectability politics?

- How does her disdain reflect skin color politics similar to those in Idlewild?

- Why does she say she began to adopt this attitude?

- With the text as a guide to your impressions, what other circumstances do you think may have contributed to her feelings and beliefs?

- What does the white man’s response to Thompson’s position of authority show about standard racial interactions in the 1940s and 1950s?

- How do these documents prove that certain racial boundaries could be challenged in the Midwest?

Pi Sigma Delta

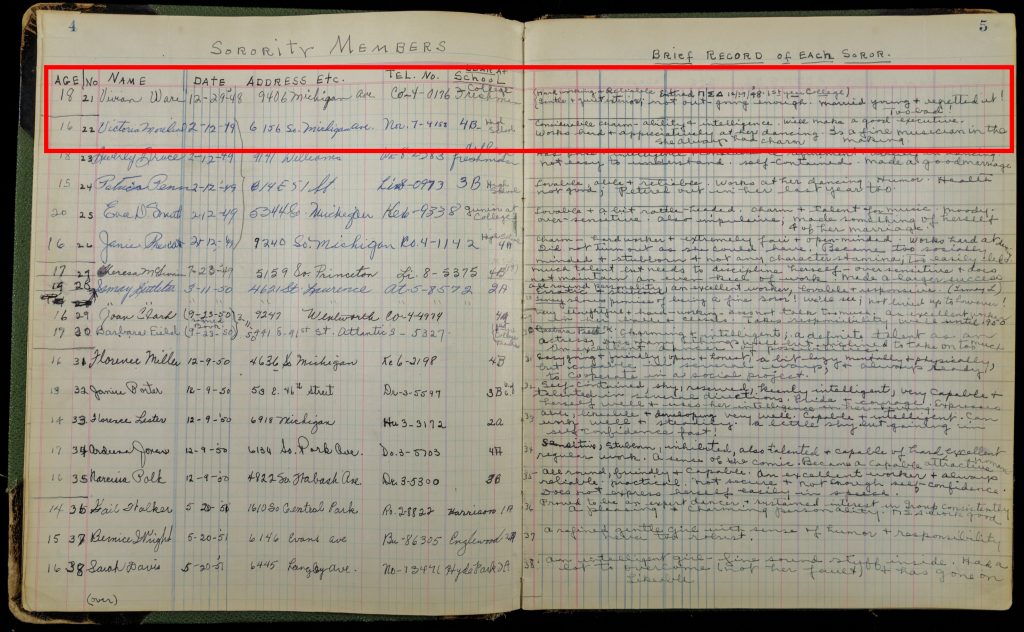

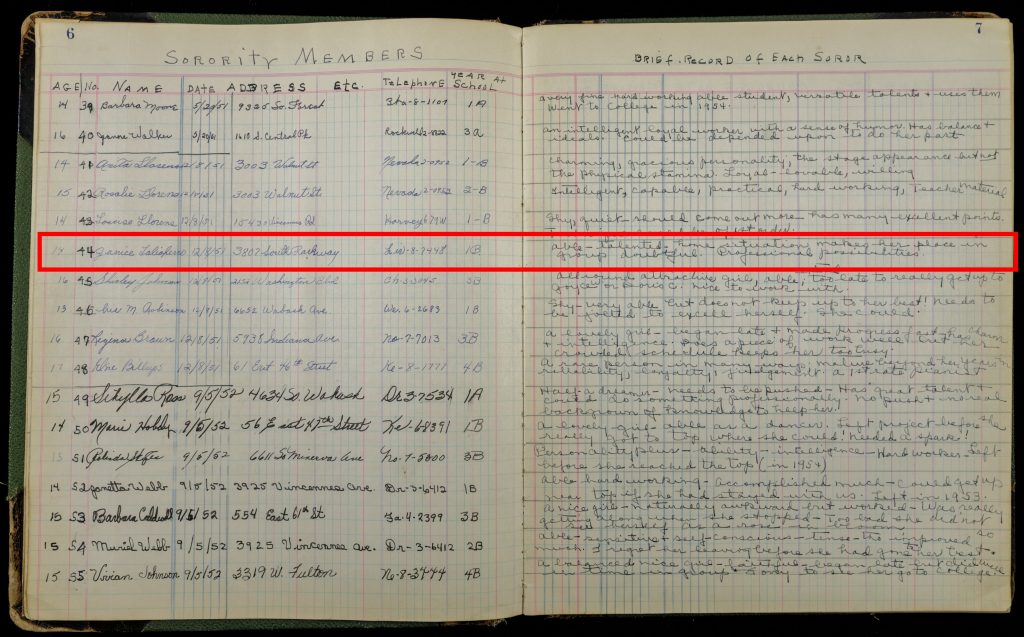

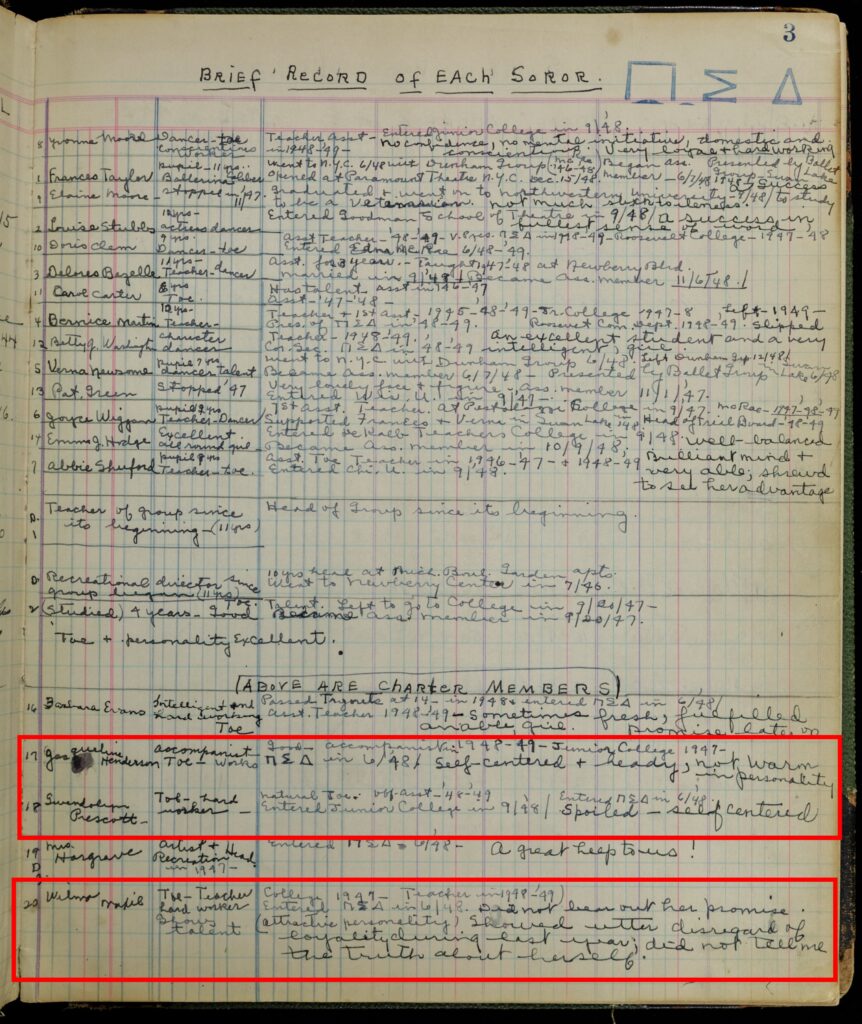

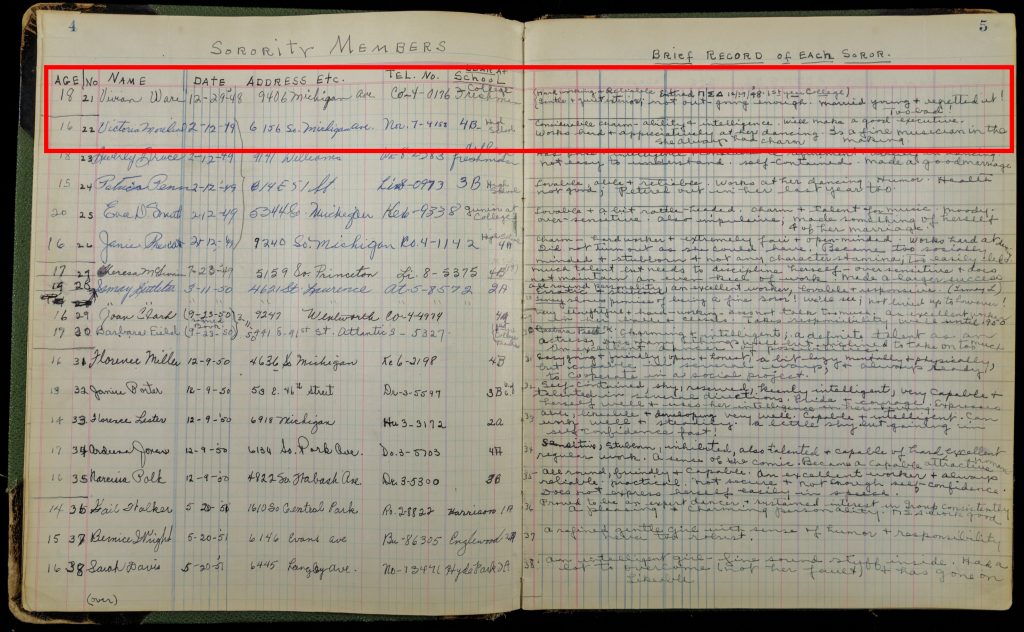

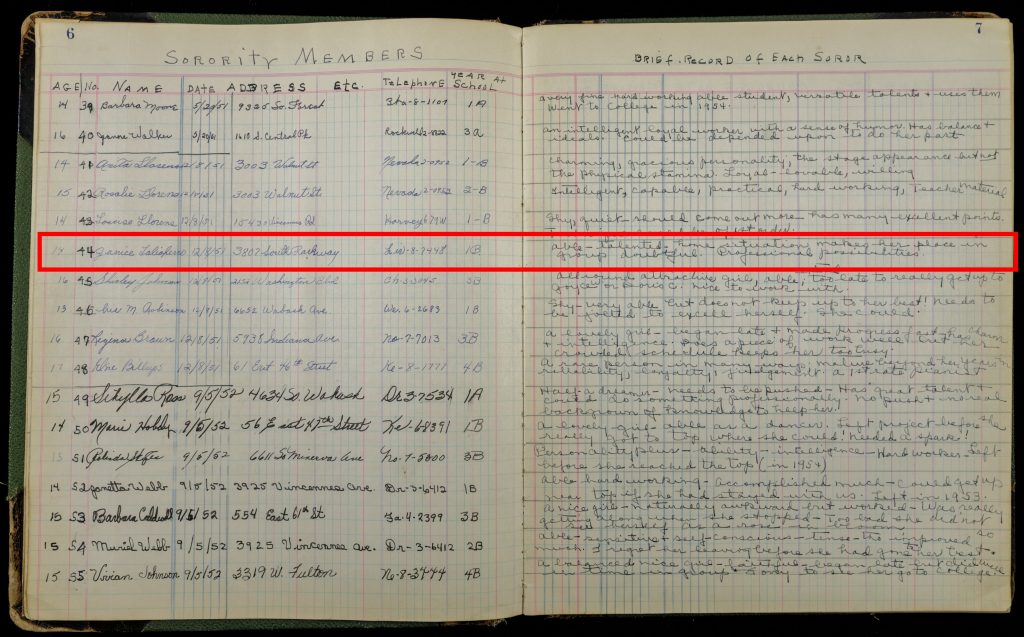

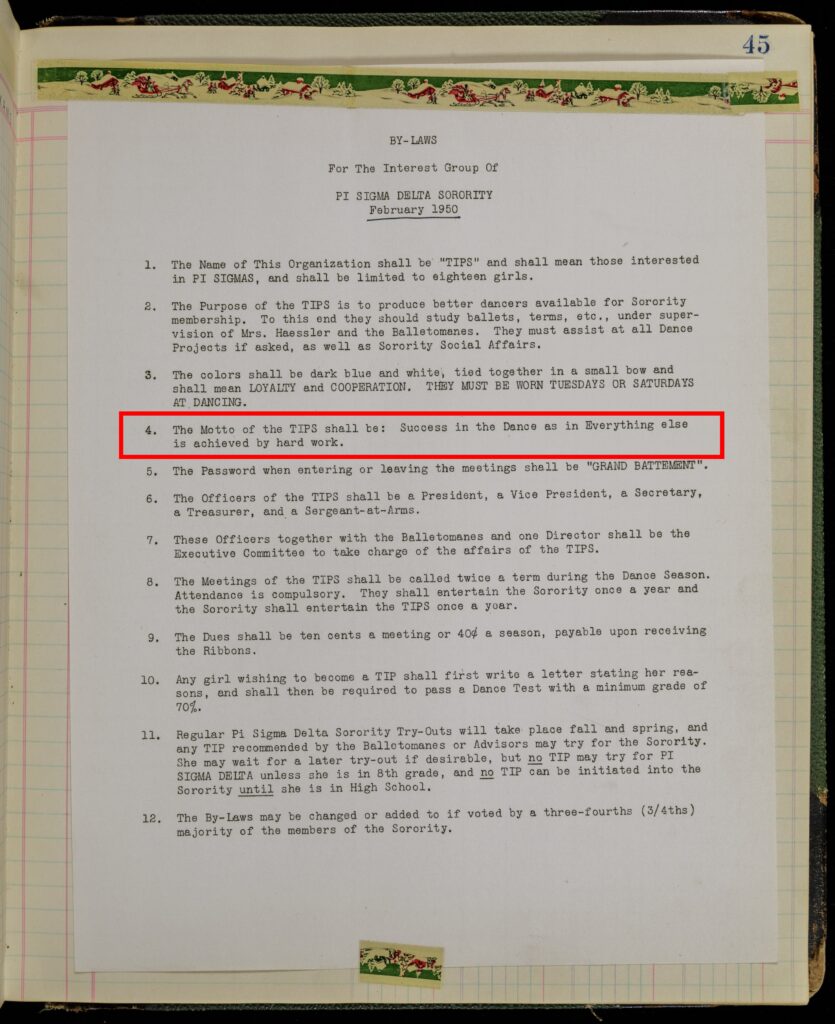

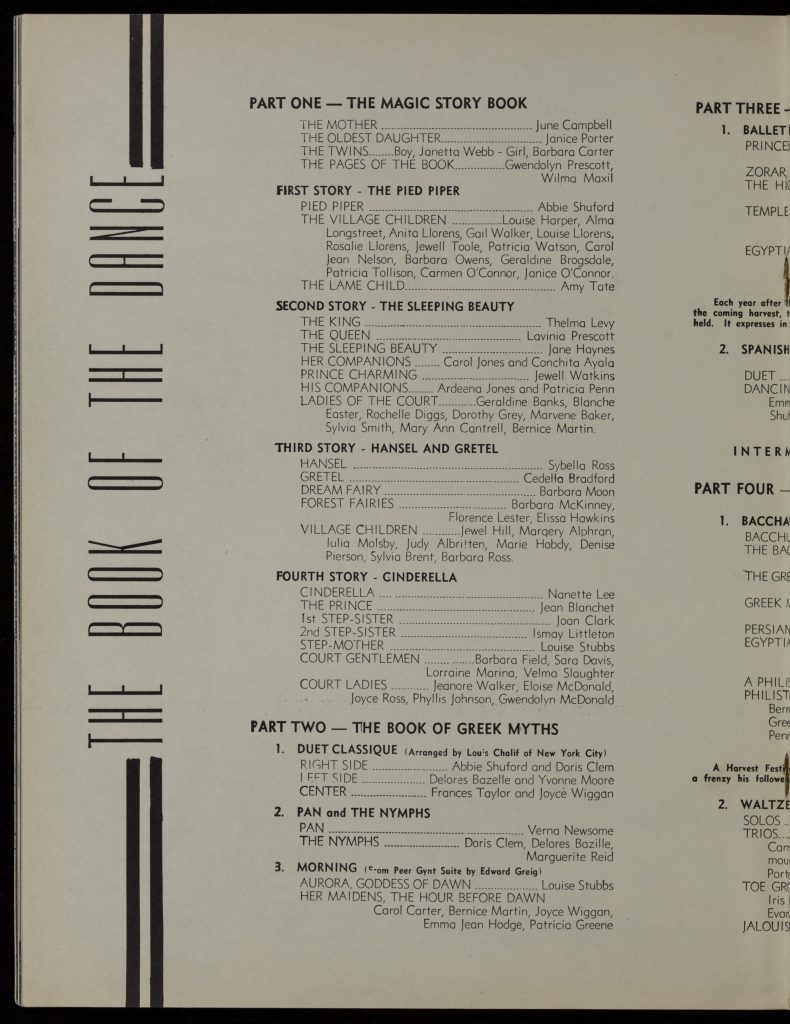

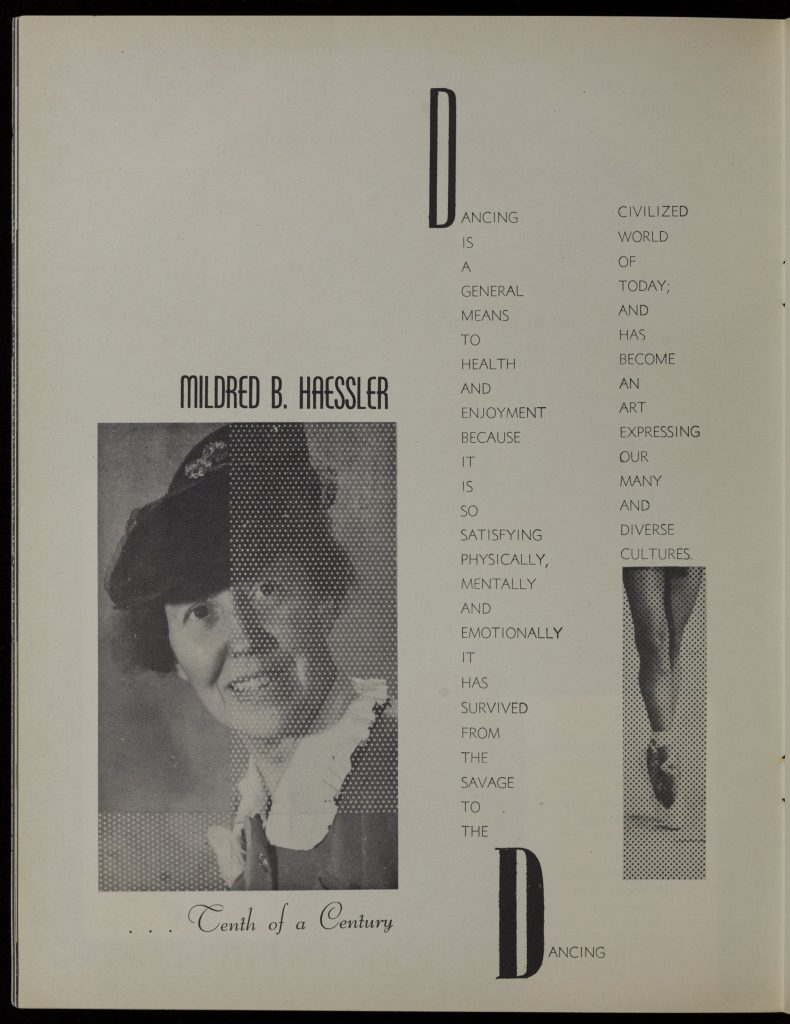

In 1937, Pearl Pachaco Williams, the Recreation Director for the Rosenwald Building (a luxury apartment building in Chicago open to African Americans), designed recreation programs for building residents, including girls’ ballet classes. Mildred B. Haessler, who was white, taught the ballet classes and later helped her students form a ballet sorority. Besides ballet, the sorority promoted other activities that met the standards of respectability, conduct, morality, and the beauty of the dominant culture. The selections included here come from the sorority’s membership ledger, which Haessler maintained. Next to each member’s name, Haessler included notes about poise, ability, and technique.

Pi Sigma Delta Sorority. The Book of the Pi Sigma Delta Sorority. Midwest Manuscript Collection. Newberry Library, Chicago.

Page 3: Jaqueline Henderson, Gwendolyn Prescott, and Wilma Maxie

Pages 4-5: Vivian Ware and Victoria Morehead

Pages 6-7: Janice Lalioferro

Pi Sigma Delta Moto

Guiding Questions:

- What is the tone of these entries? What are some clues indicating that Haessler wrote them, as opposed to a student?

- How could embracing the standards of ballet (aesthetics, discipline, standards of beauty, etc.) and excelling at ballet enhance notions of respectability and social acceptance for black girls and their families?

- In what way is this goal of ballet excellence gendered? Why might the respectability of girls and women be particularly important to furthering the goals of racial progress?

- What values does the sorority’s motto promote? What types of stereotypes might the motto be addressing “between the lines”?

- What common racial stereotypes and myths does Haessler rely on when evaluating these African American teens?

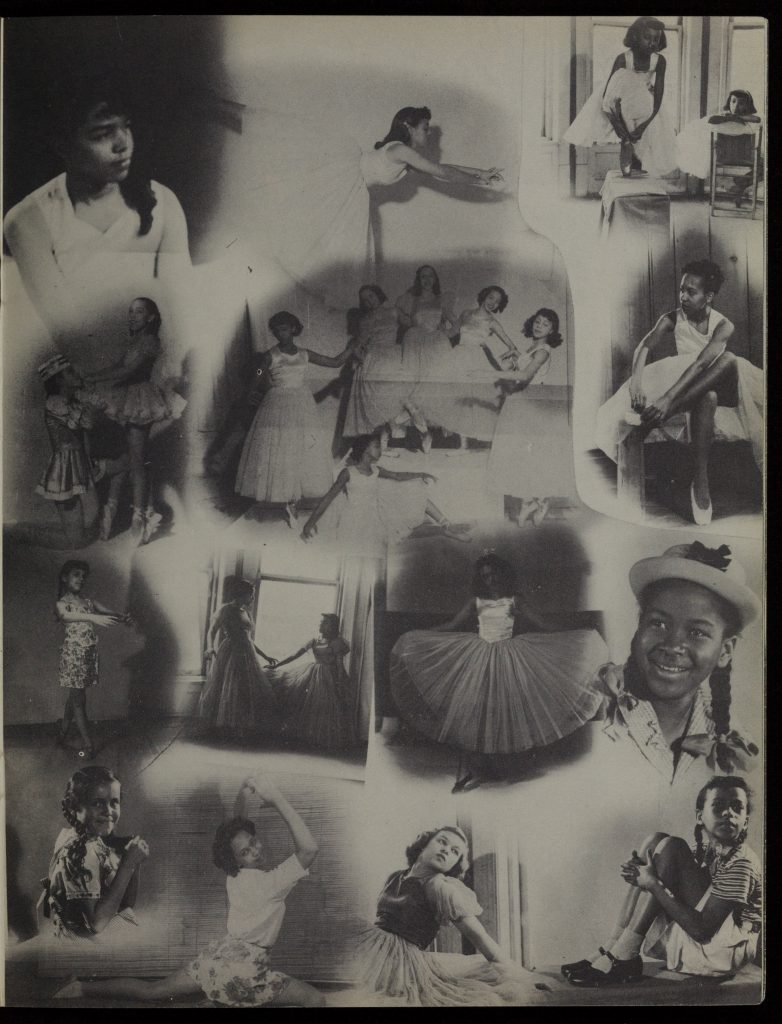

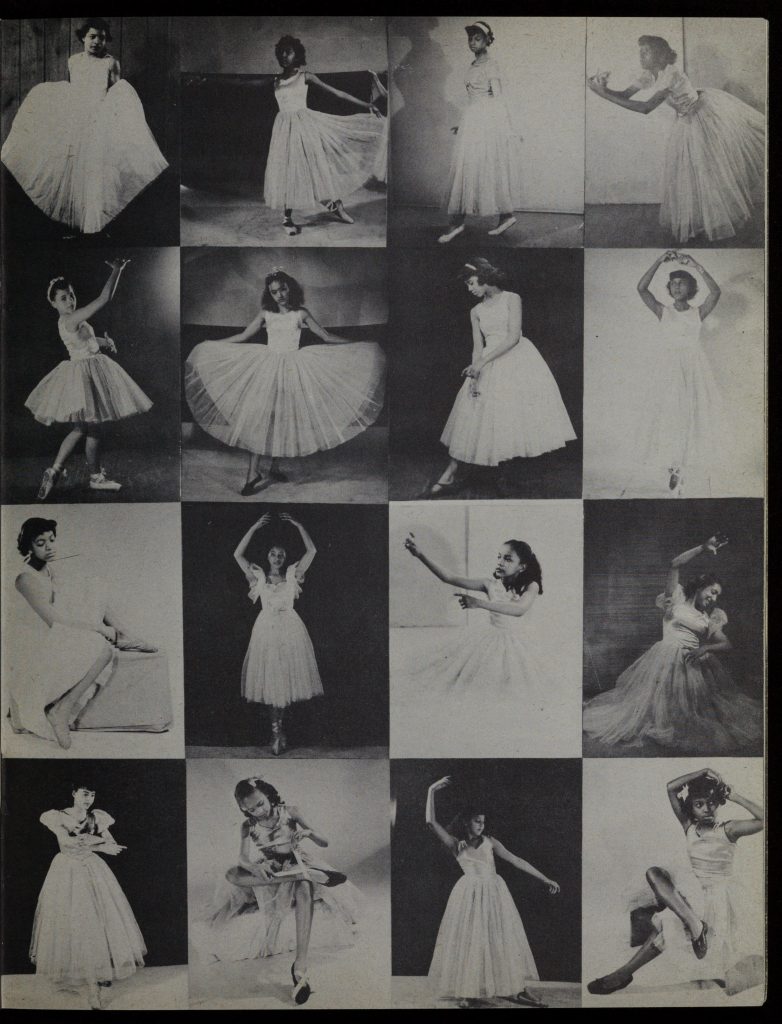

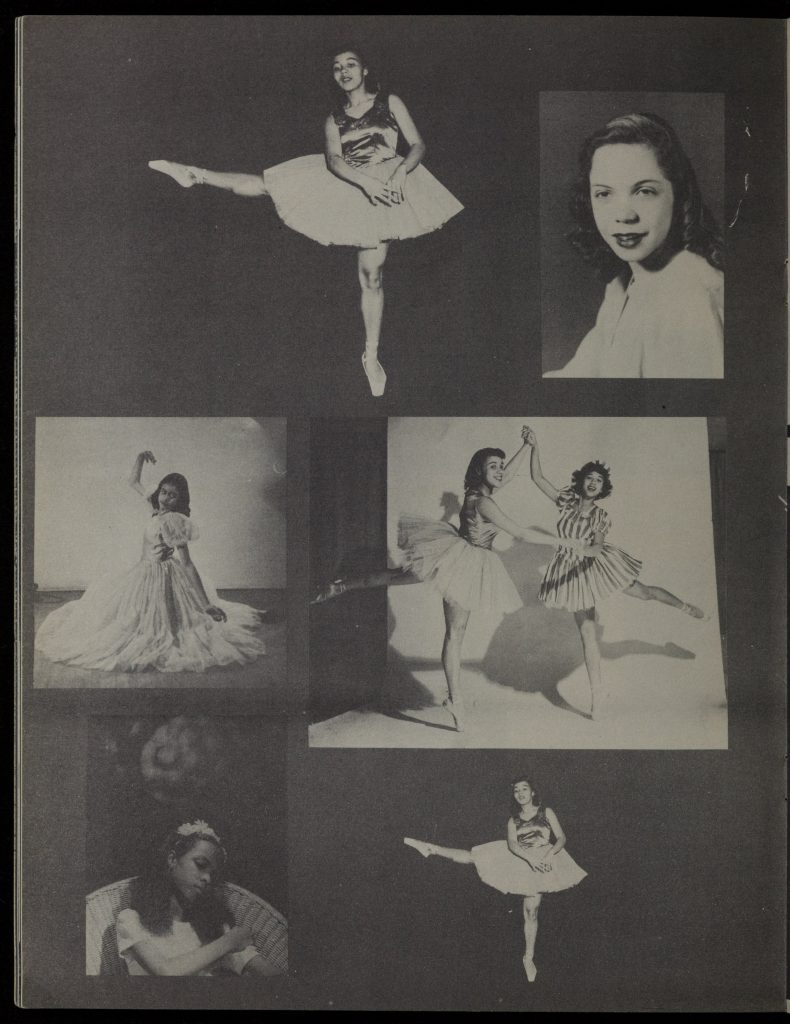

Mrs. Haessler’s Dance Brochure

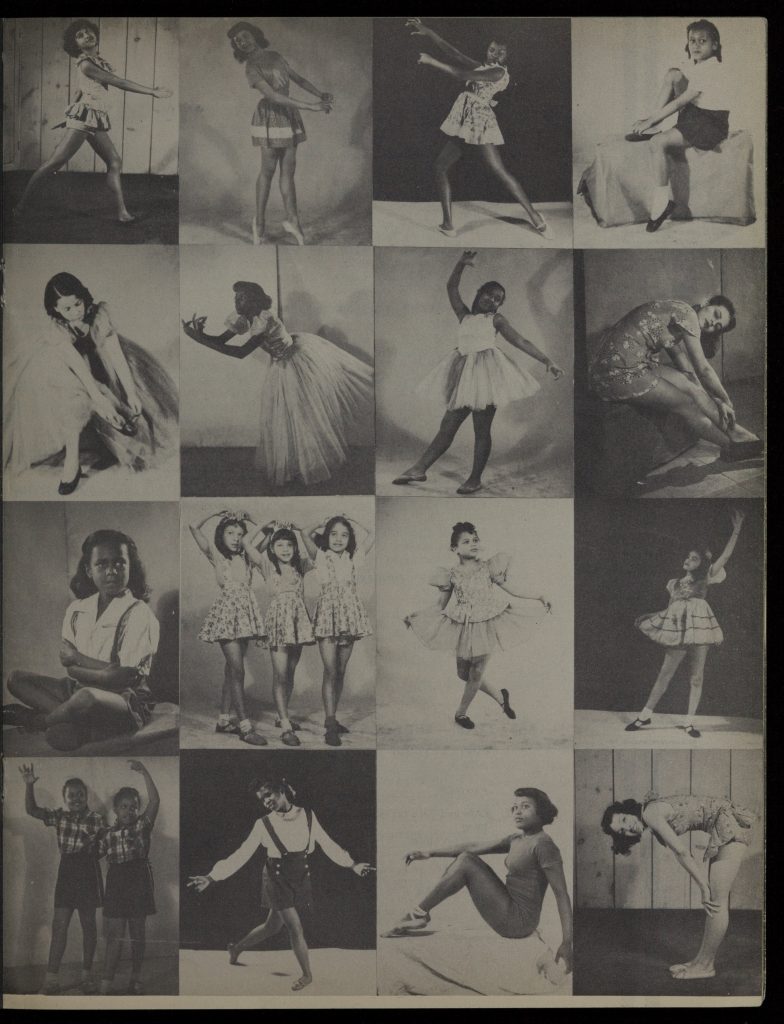

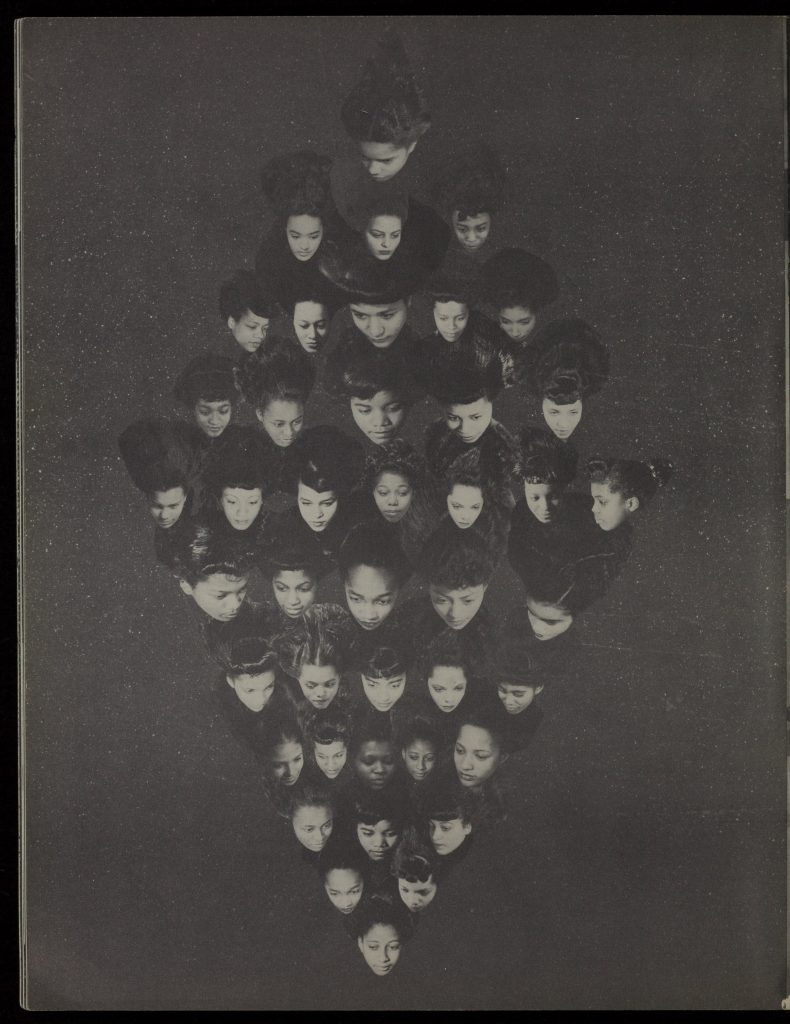

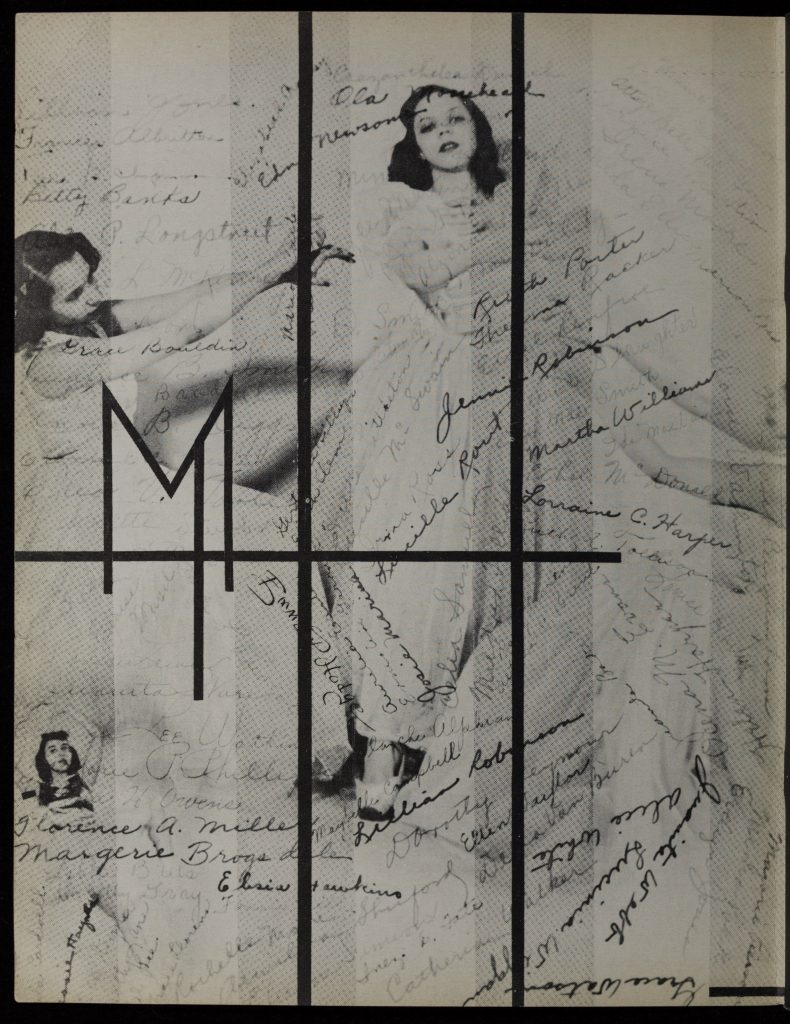

This is a program brochure for a 1947 dance recital directed by Mildred B. Haessler. The brochure contains a lineup of performances, as well as images of girls whose families took out ads to support and promote them. The girls autographed one of the final pages.

Mildred B. Haessler Ballet Group. Tenth of a Century: The Mildred B. Hassler Ballet Group Presents the Book of the Dance. Chicago, Haessler Ballet Group, 1947.

Guiding Questions:

- What surprises you about the photos? Do they challenge any assumptions you may have held about the lives of African American girls in the 1940s?

- In what ways might these pictures reflect the goals of the girls or their families?

- What vision of black femininity do these goals reflect?

- What connections can you find between ballet and respectability politics? Find specific visual clues to reflect these connections.

Chicago Commission on Race Relations

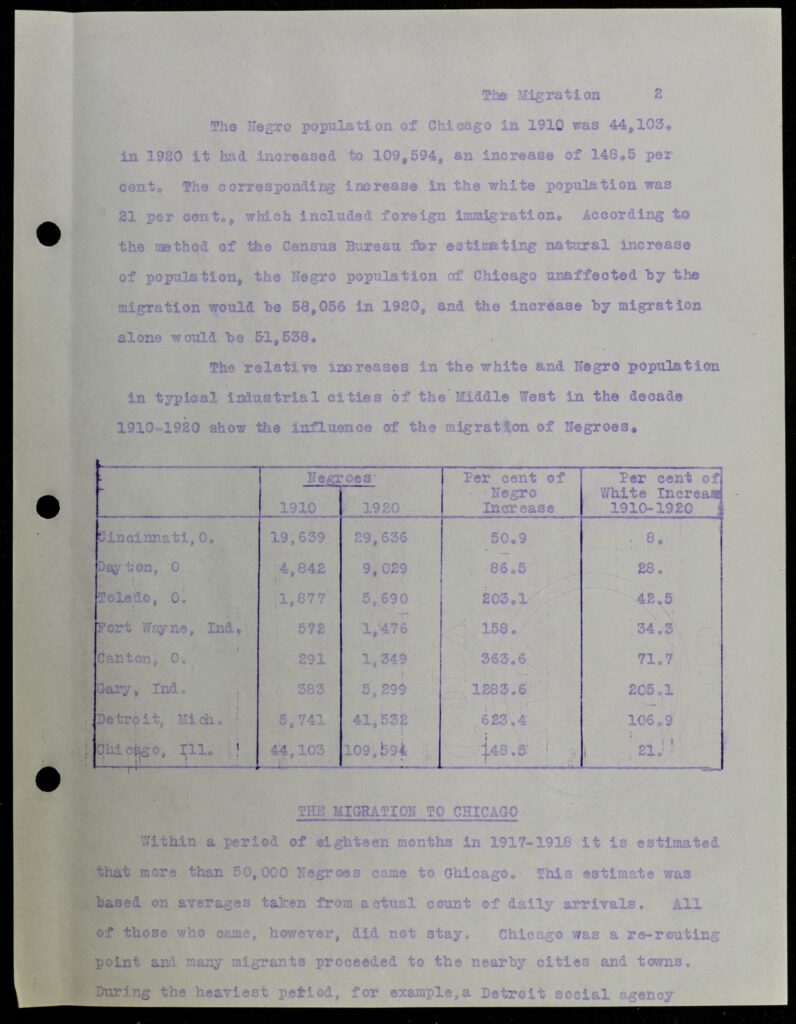

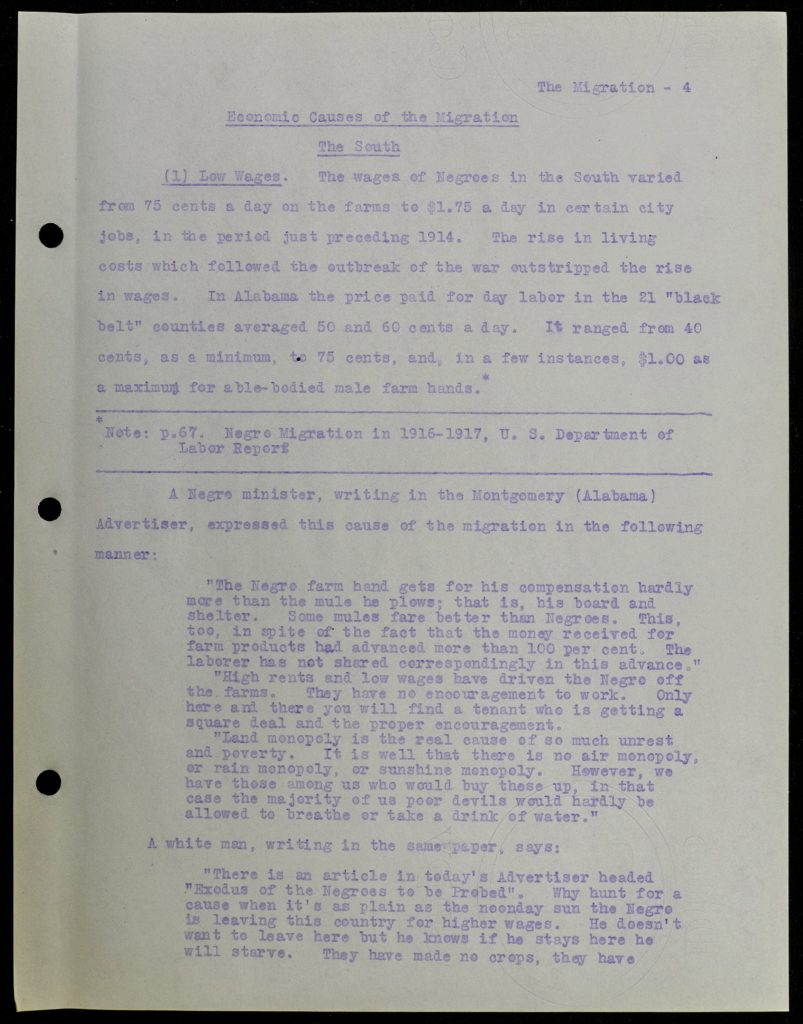

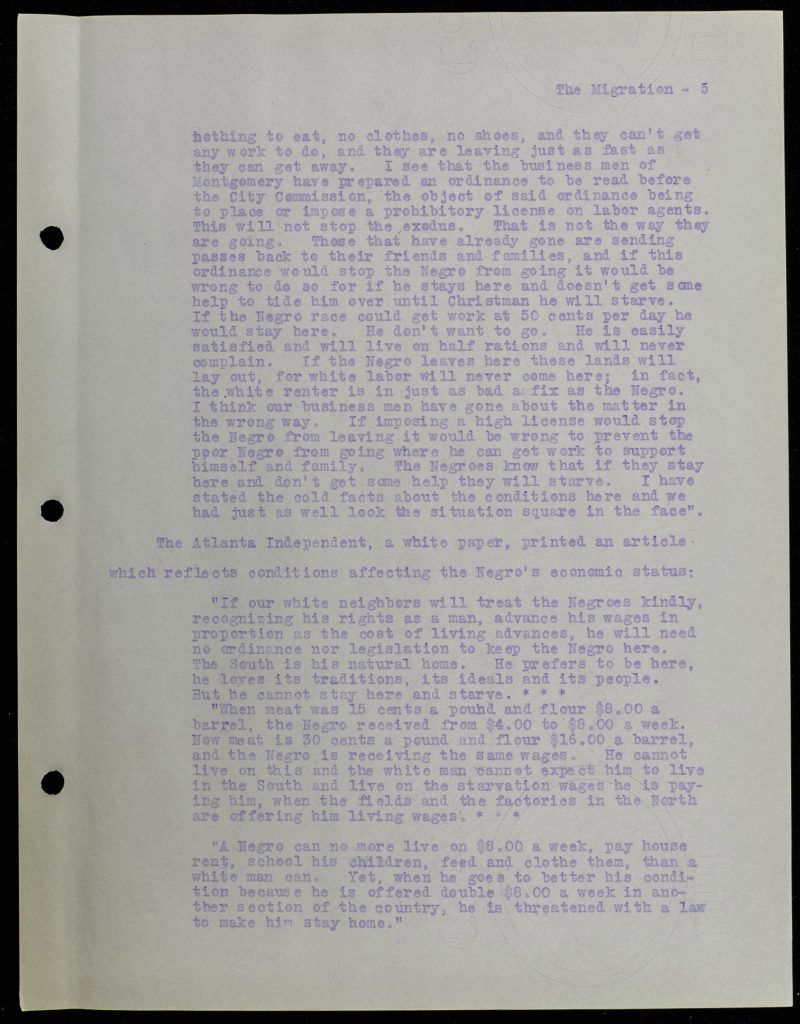

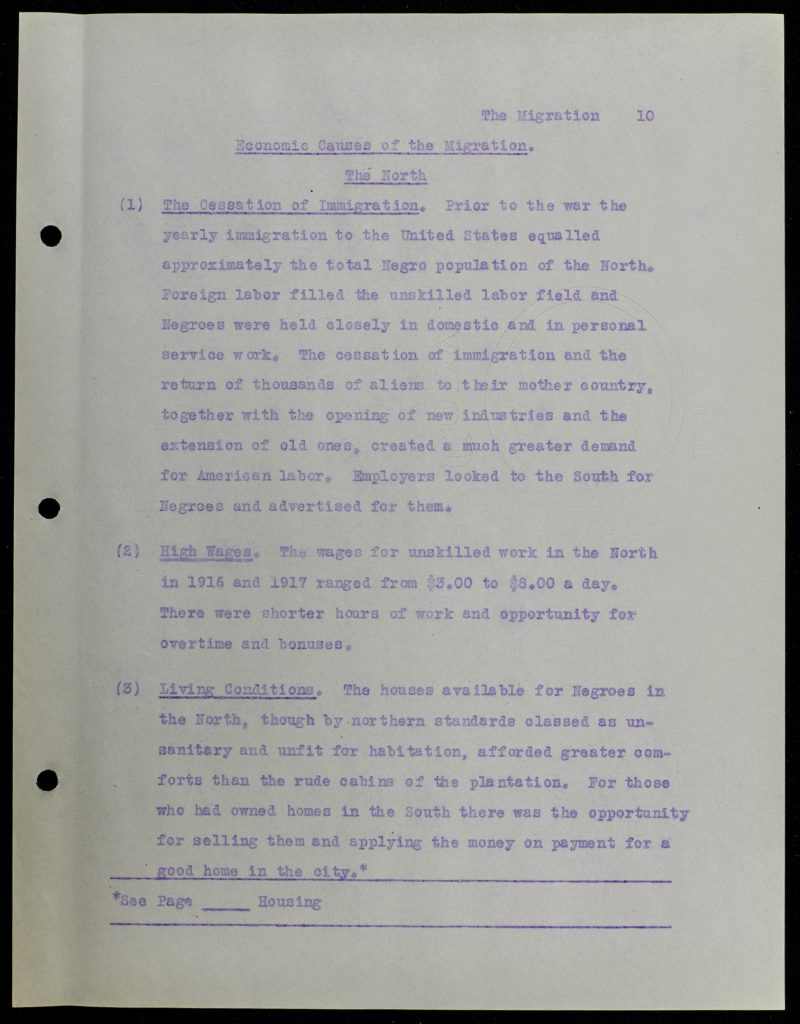

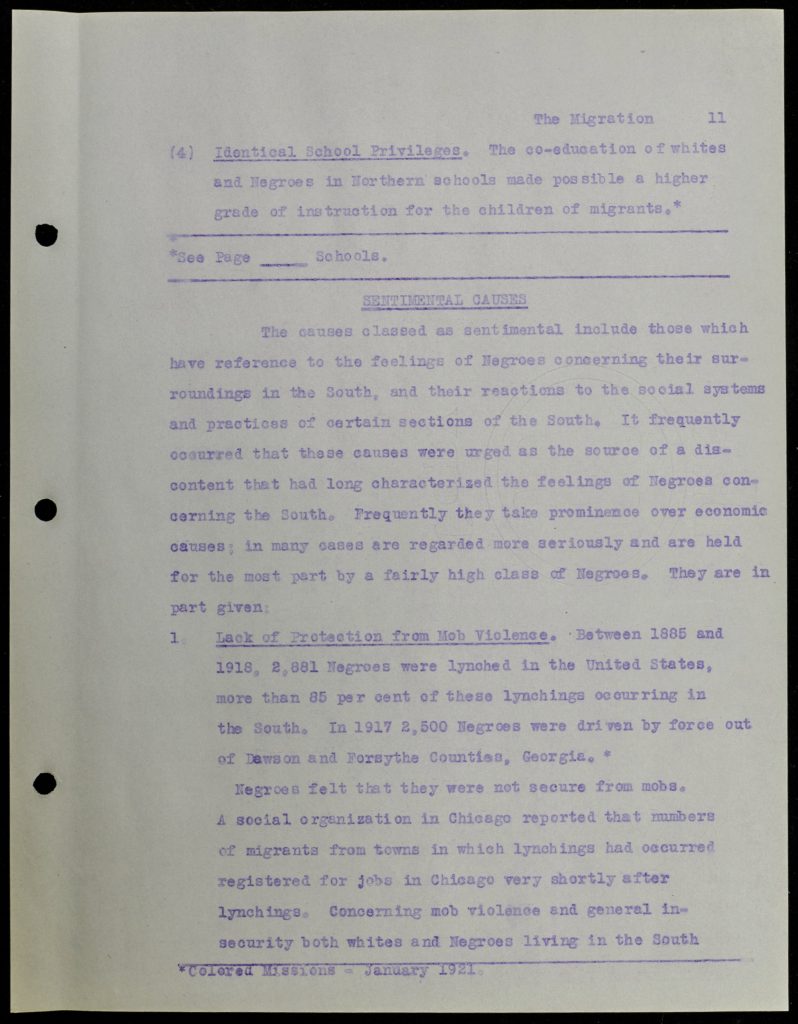

The Chicago Commission on Race Relations was set up after the Chicago Race Riots of 1919 to investigate the causes of the riots and prevent future violence. The primary focus of the investigation, however, became the life and experiences of African American residents of the city. The Commission concluded that widespread discrimination, racist housing policies, and violence against African Americans by white groups were the main causes of the riot. To contextualize why Chicago’s Black population had grown in the early 20th century, the Commission analyzed reasons why Black southern residents moved north. Today historians call this massive movement in the African American population the Great Migration.

Selections from the “Chicago Commission on Race Relations” on the causes of the Great Migration. Victor Lawson Papers. Newberry Library, Chicago.

“I. Introduction”

“II. Causes of the Migration”

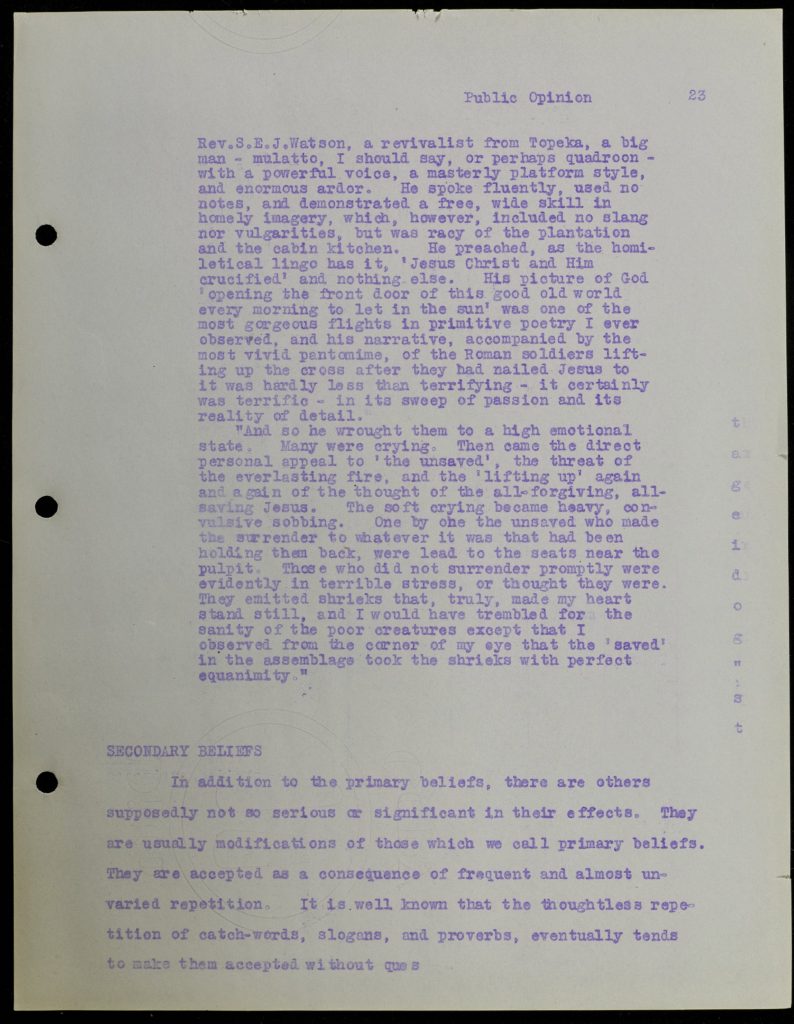

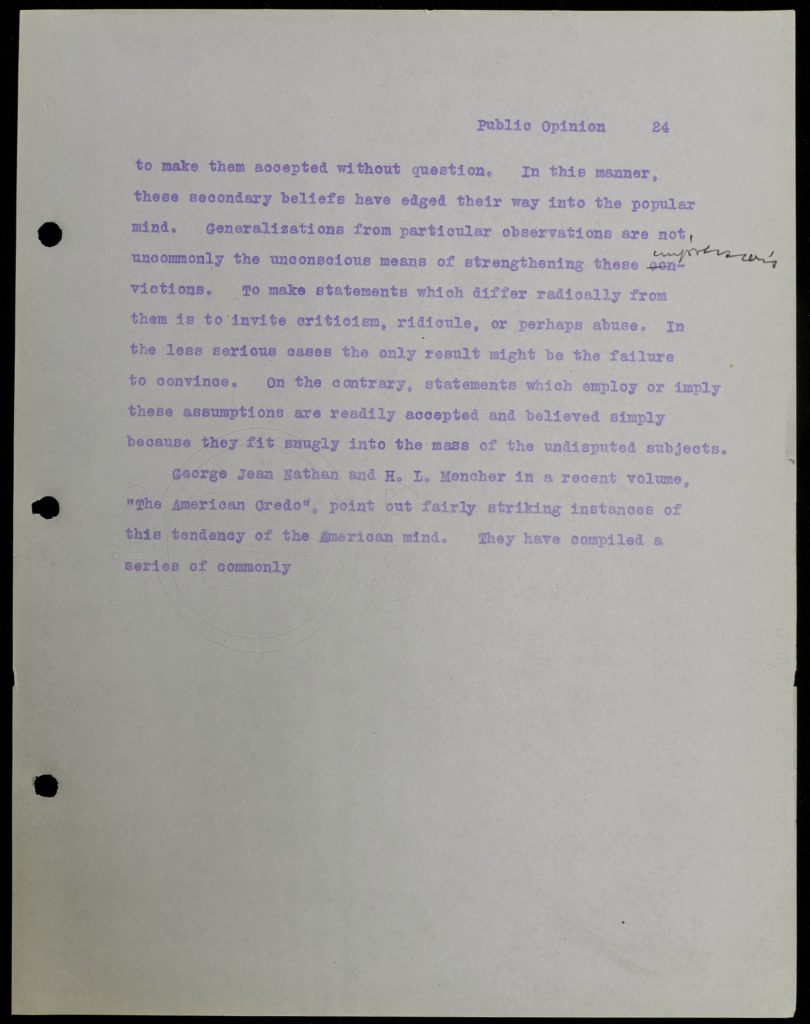

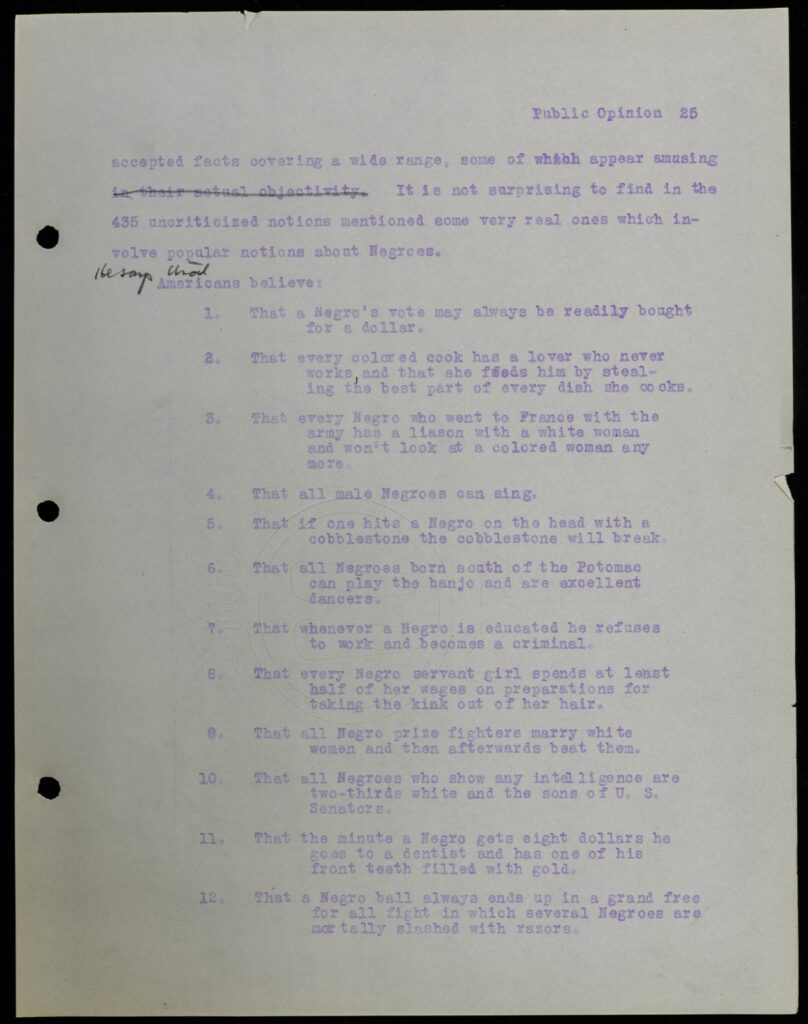

White Public Opinion

Guiding Questions:

- What reasons do the authors give for African American migration north? What interactions between White and Black Americans appear in the document?

- Do you find any of these racial interactions surprising? Why?

- What does this document suggest about the strength or fragility of racial boundaries in Chicago at the time?

Supplementary Curriculum: Race, Respectability, and Resilience

Cathleen Martin, 2018-19 Mellon Foundation-Newberry Teacher Fellow

Essential Questions:

- How have African Americans been shaped by the experience of living in the Midwest?

- How have African Americans shaped the Midwestern experience?

- How have the values of race, respectability and resilience shaped the African American experience in the Midwest?

- How have African Americans’ understandings of race, respectability and resilience helped to shape the Midwest?

Culminating Activity / Assessment

Students will critically analyze the documents provided and answer the document-based question (DBQ): How did the values of race, respectability and resilience both shape and inform the experiences of African Americans in the Midwest?

Content Goals

- To help students to think about the interplay and exchange between race and place in the American cultural experience.

Historical Thinking Goals

These activities help students:

- Think critically about the sources historians use

- Think creatively about how to explore alternative source material

- Differentiate between historical facts and historical interpretations

- Challenge arguments of historical inevitability

- Analyze cause and effect relationships and issues of historical causality—including the importance of the individuals as a historical actor with personal agency

Literacy Goals

- To get students to interact critically with primary sources

- To have students read scholarly materials with clarity and understanding

Connection to Today

- To think about how the experience of African Americans has shaped and been shaped by the Midwestern experience.

Historical Problems

- In the history of African Americans the primary focus has been on the experiences of African American communities in the south and on the east and west coasts. As such, we have ignored (and to some extent rendered inauthentic) the experience of African Americans in the Midwest

- The resulting effect is an unbalanced analysis of “the” African American experience, as well as an un-nuanced treatment of the Midwest.

Unit Plan

Day 1: Lesson Hook

Have students review the case of Michael Brown. (You could either assign this investigation for homework, you could choose an article for the class to read together, or you could refer to the Wikipedia Page on the “Shooting of Michael Brown.”)

Next read the article entitled “Respectability Politics Won’t Save the Lives of Black Americans,” or any similar article about Respectability Politics and the contemporary African American experience.

Ask students the following question:

Why do you think that journalists covering the police brutality against African American youths are so inclined to mention that they were “honor roll students,” planned to attend college and came from “good families?”

Review the definition of Respectability Politics and discuss how that tendency was invoked in this case (or perhaps other cases).

You might assign students to look for counter claims in the media that attempt to indicate that Michael Brown lacked respectability and was therefore not an innocent victim of police brutality.

- How did notions about race and resilience play out in the case of Michael Brown’s shooting?

- In what ways did beliefs about race and racial stereotypes play a role in this case?

- In what ways have notions about African American “resilience” contributed to a justification for their abuse—such as, a false perception that they have a greater capacity for difficulties, abuse, or roughness and are adept at (and therefore well-suited for) handling abuse?

This conversation is a preliminary one that will help students consider some of the ideas that will be presented in the documents. Don’t be concerned about the precision of these ideas/values at this point. The conversation is merely meant to activate some of the ideas that will be presented. You might want to revisit this case/conversation after students have completed the DBQ in order to have a more in-depth conversation about the real- world consequences of how these ideas might currently be playing out in contemporary American life.

Day 2: Preparation/Guided Practice

Read the Introduction with the class and review the document-based question to check for their understanding. Please note: the question already includes the categories of analysis. Therefore this DBQ makes an excellent introduction to DBQs in general. Help students to understand what analytical categories are and how to marshal evidence to build a case for each of the three categories. Most of the documents will fit under more than one category, so help students to identify the categories each document might support as you review them. Emphasize the goal of providing even and equal coverage of each category and explain that students will need to make personal value judgments regarding where and how to use each document.

Have students review the first few documents in pairs. You could either ask them to write the answers to the guiding questions, that accompany the document, or review them verbally.

Next have students share their observations with the class.

Once students have solidified their analysis of the document, ask them to complete the document analysis sheet for the first document. You might want to model how to do so for the first document.

Day 3-4: Individual Practice

Support students in completing a document analysis sheet for each document.

Depending on their current skill level, they can either continue to work in pairs or as a large group. Support them until you feel that they are capable of analyzing documents on their own. You may either assign a few documents for homework and then analyze their conclusions with the general class, or you can have students work individually in class and then compare their conclusions to their partner’s. Either way, continue to work on the process of document analysis until students have reviewed all of the documents.

Day 5-6: Organization and Writing

Have students write out their three-pronged thesis—to include race, respectability and resilience—and list which documents they will use as evidence under each analytical category. If your class time is limited, students can complete this assignment for homework. Once their organizational structure is in place, ask students to write a rough draft of their essay. They should answer the following question:

How were the experiences of African Americans in the Midwest shaped by race, respectability and resilience?

Finish final draft for homework.

Day 7: Reflection

Wrap up the discussion. What does all of this mean? Why is it important? What will you take away from this work?

Additional Resources

Schwalm, Leslie. Emancipations Diaspora: Race and Reconstruction in the Upper Midwest. The John Hope Franklin Series in African American History and Culture. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009. xii, 387 pp.

Blocker, Jack. A Little More Freedom: African Americans Enter the Urban Midwest, 1860-1930. Urban Life and Urban Landscape Series. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2009. xvii, 330pp.