Introduction

The Ottoman Empire was one of the largest and longest-lasting empires in world history, stretching across the Middle East, Eastern Europe, and Northern Africa at its zenith in the sixteenth century. Many European observers of the time experienced and depicted the Ottomans as a relentless force that not only conquered former Byzantine lands, but also lay siege to Vienna in 1529 and threatened further expansion into the heart of the European continent. At the same time, powers like France, Venice, and England actively engaged the Ottomans as partners in diplomatic and commercial projects connecting Europe and the Middle East. After the second failed siege of Vienna in 1683, the Ottomans gradually began to lose territory in the eighteenth century while at the same time intensifying their political and cultural connections with European states.

Going beyond the conventional image of the Turks as the Western “Other,” this collection of documents reveals a variety of European encounters with the Ottomans in the early modern period. Such sources show the multiple ways in which Ottomans and Europeans shaped each other’s histories: as military foes as well as trading partners, as religious rivals and as well as cultural interlocutors.

Essential Questions:

- How did European leaders, observers, and artists perceive the rise and expansion of the Ottoman Empire?

- What recurring themes emerge from the documents in this collection? What is the intended audience of these works?

- What does the changing nature of European perceptions of “the Turks” suggest about the relationship between the European states and the Ottoman Empire?

A View of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman state emerged in the early fourteenth century as a small but enterprising principality located on the Byzantine frontier in northwestern Anatolia. As Osman (the eponymous founder of the Ottoman dynasty) and his successors led lucrative raids and built a series of regional alliances, they assembled an impressive military force as well as an evolving administrative structure. The Byzantine and Balkan states became deeply familiar with the Ottoman state as it grew into a formidable empire by waging war, negotiating diplomatic relations (including strategic marriages), and forging a variety of local alliances.

The Ottoman conquest of the Byzantine capital of Constantinople in 1453 marked a major moment in the evolution of the Ottoman state into a powerful empire. To Mehmed II, the sultan who orchestrated the unrelenting siege and eventual sack of the city, the taking of Constantinople was a crowning achievement. To many European observers of the time, it signaled the establishment of the Ottomans as a monumental threat that they had fight on every front. Indeed, over the next three centuries, European states developed several ways to reckon with the specter of “the Turks” (a broad label often applied to both rulers and Muslim subjects of the Ottoman Empire; the Ottoman dynasty itself did not use this name in its titles).

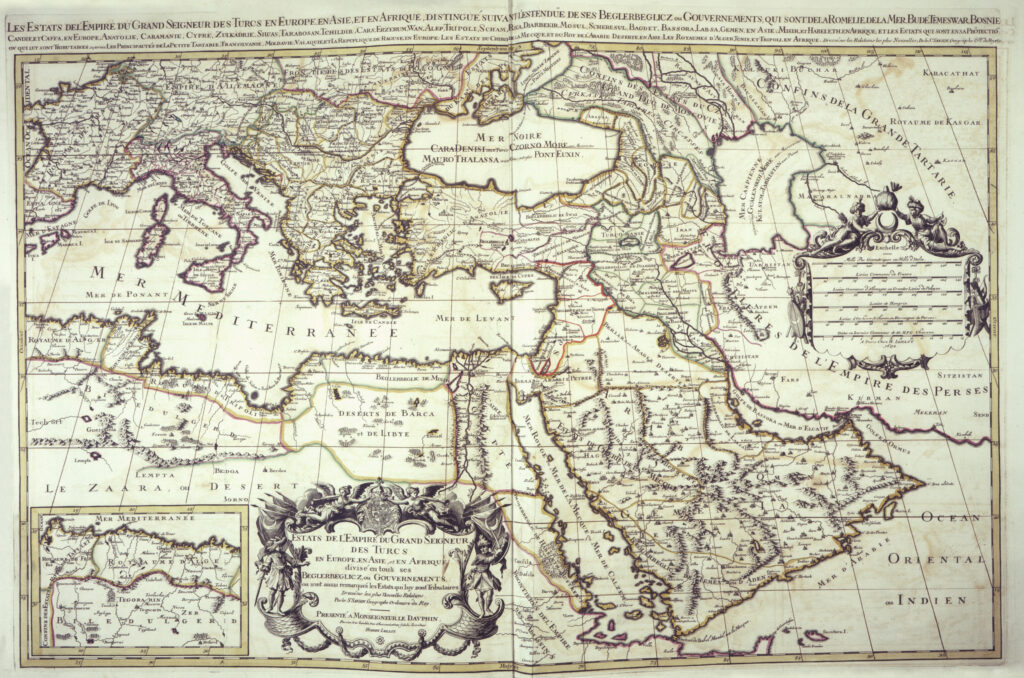

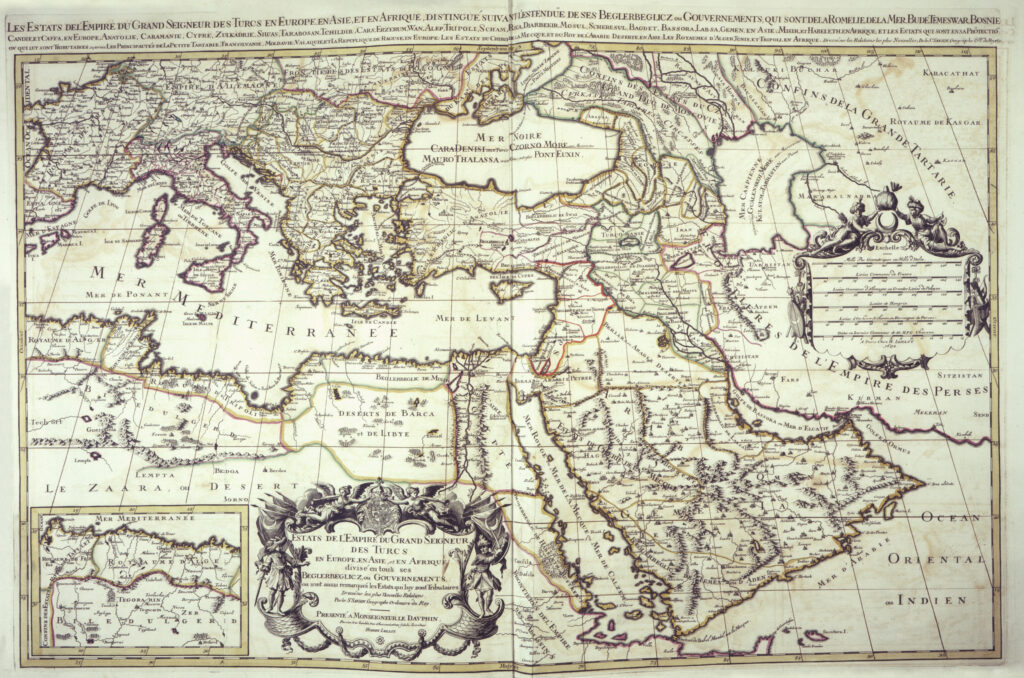

The map in this section gives a sense of the reach of various Ottoman domains in the seventeenth century. The French cartographer Nicolas Sanson (1600-1677) went beyond the earlier European depictions of the Ottoman Empire by providing an influential new perspective. Sanson not only clearly demarcated Ottoman borders in different colors, but he also subdivided the imperial domains by continents, helping shape new geopolitical terms like Turkey-in-Europe and Turkey-in-Asia.

Questions to Consider:

- Examine the map’s depiction of Ottoman domains. What features are emphasized in the map?

- What does the territorial reach of the Ottoman Empire across three continents suggest about its political importance?

- What are the potential audiences and purposes for this map?

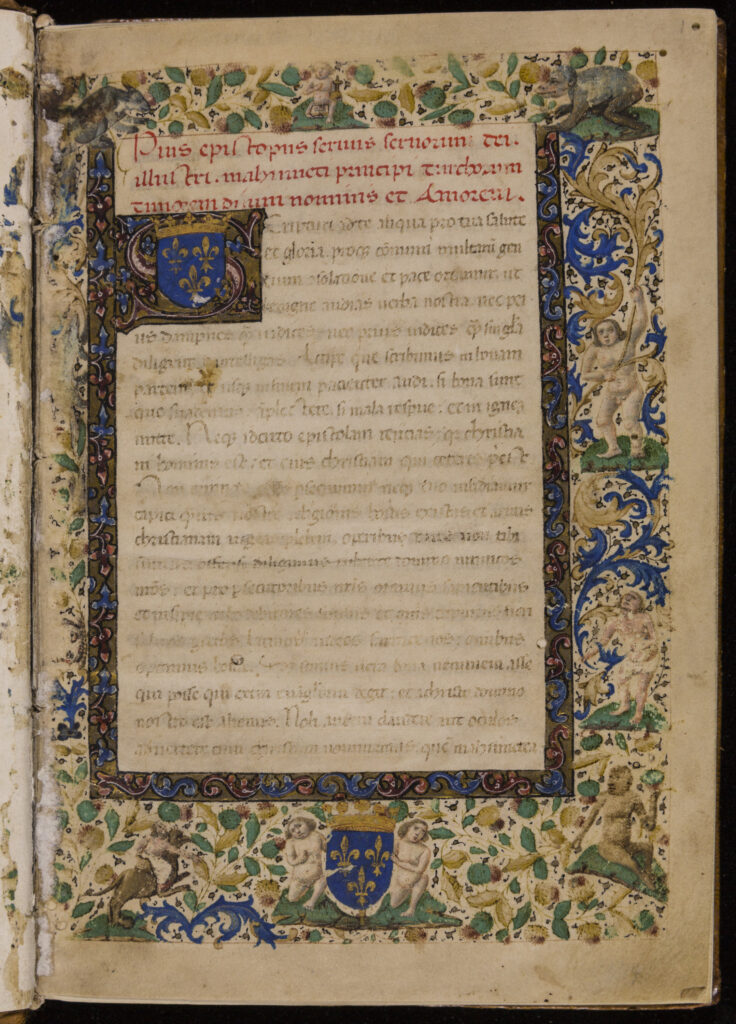

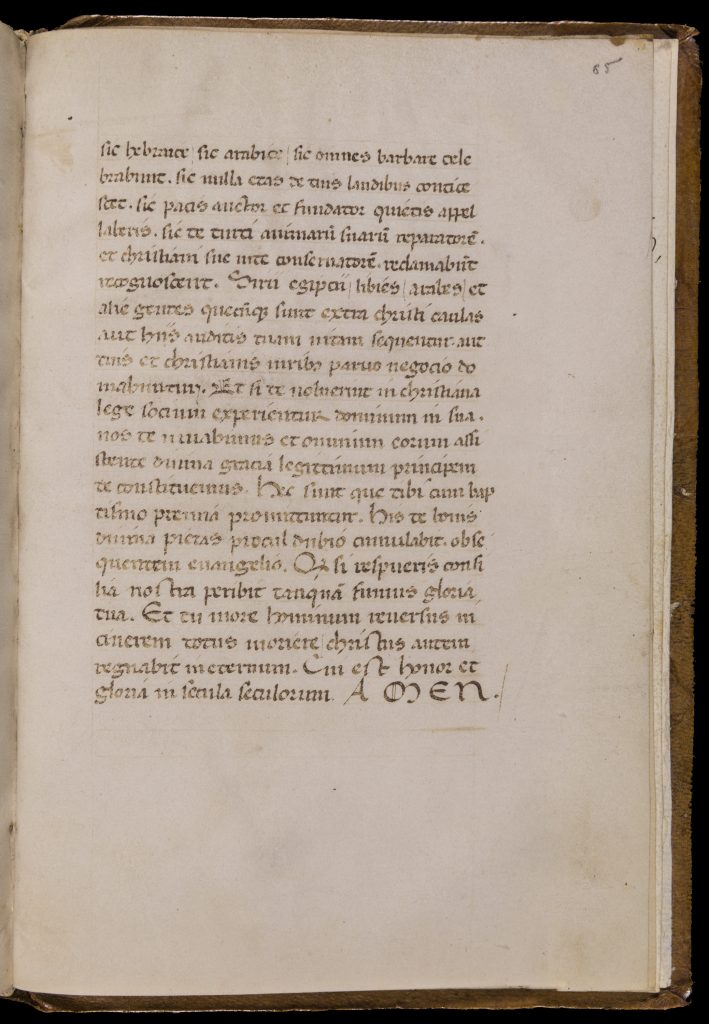

Early Encounters

Alarmed by the fall of Constantinople, Pope Pius II (1405-1464) composed a long letter to sultan Mehmed II (1432-1481). While styled as a missive addressed to “the illustrious prince of the Turks,” this document from 1461 was more of a theological treatise on Christianity and Islam than a conventional letter between two dignitaries. Throughout the letter, Pope Pius II urged Mehmed II to abandon Islam and convert to Christianity, pointing to “the errors of Muhammed’s teachings” and extoling the superiority of the Christian faith. Given the high likelihood that Mehmed II never read this letter (and the fact that he never converted), the content of this papal document continues to invite questions about its purpose, style, and appeal.

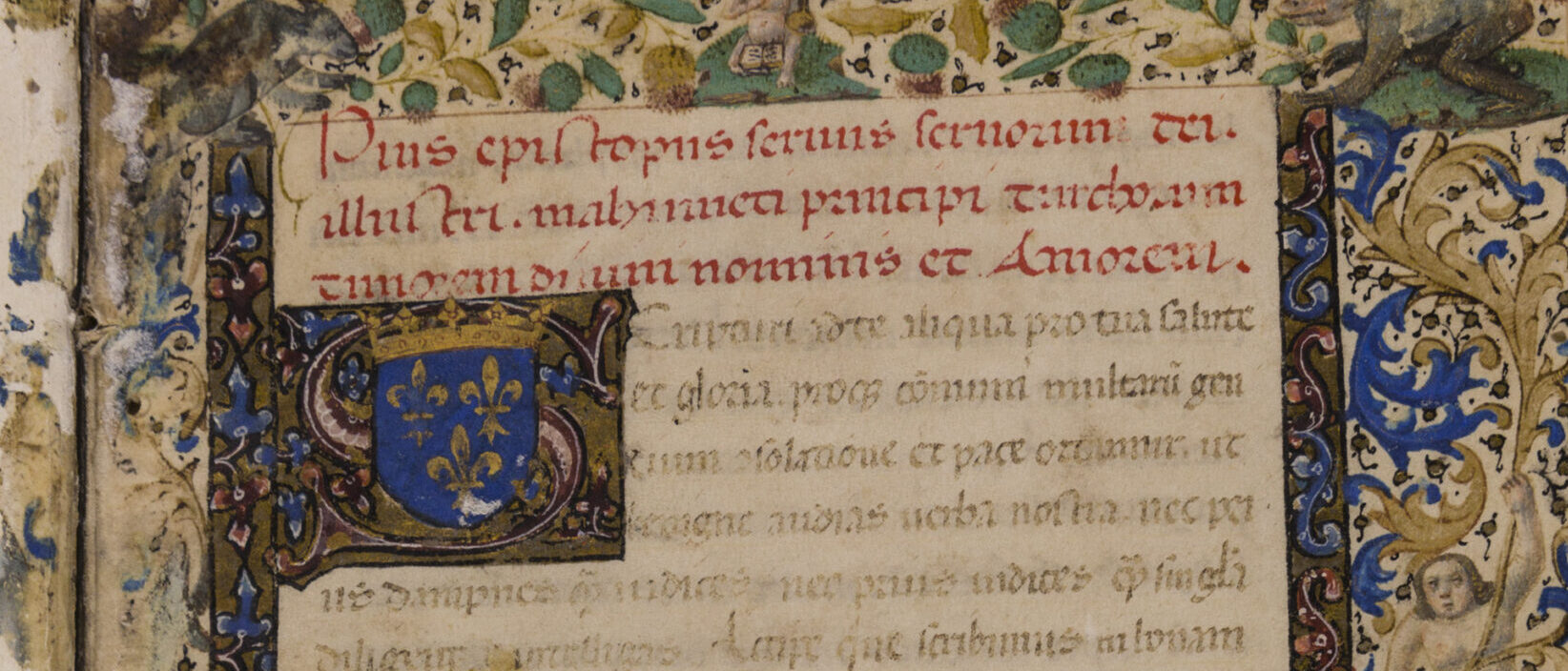

Selection: Pope Pius II, Pius episcopus seruus seruorum dei illustri mahumeti principi turchorum timorem diuini nominis et amorem (1462-1470).

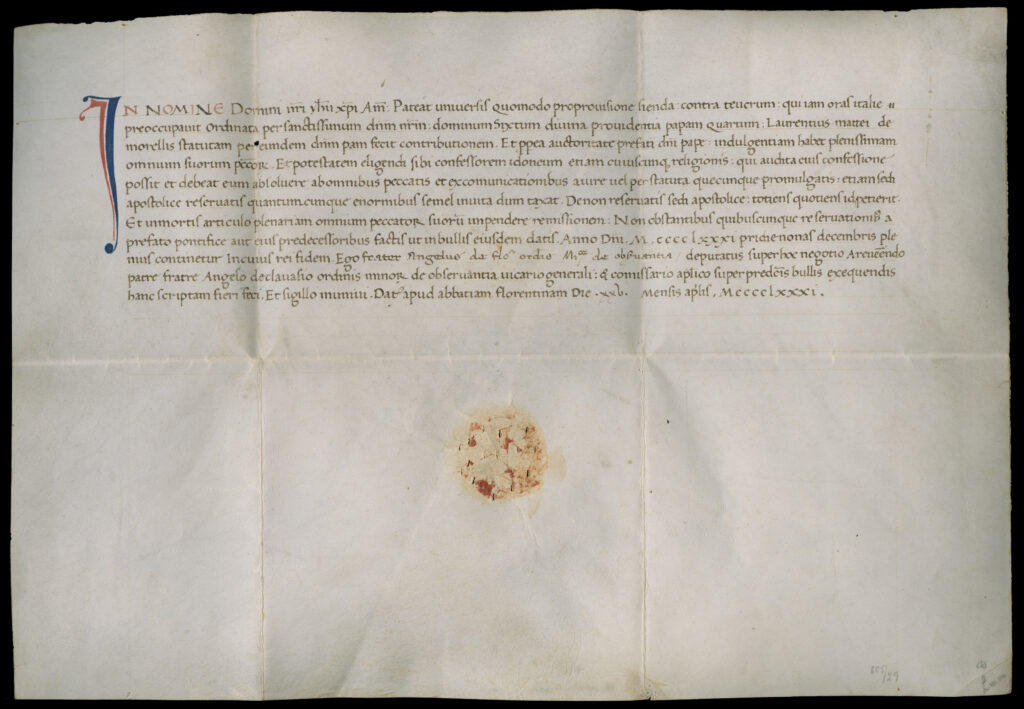

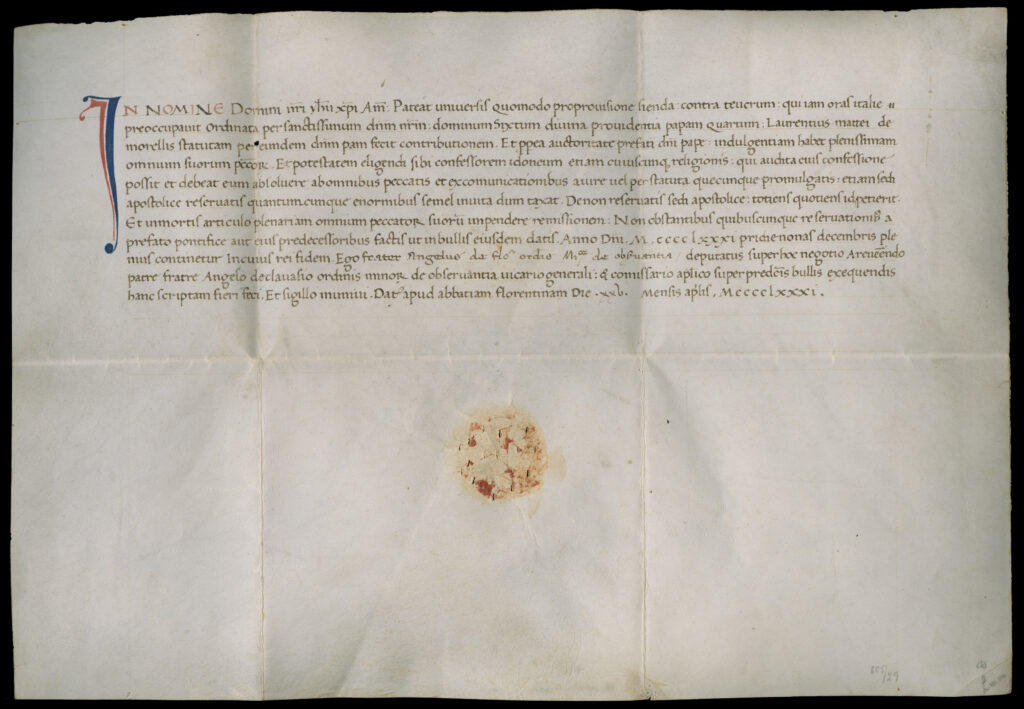

The continuing Ottoman advances spurred other Catholic bishops to issue calls for a renewed crusade against the Turks. During the brief Ottoman occupation of Otranto in southern Italy in 1480, many clergy across Europe preached sermons and issued indulgences in order to recruit soldiers and collect money for a war against the Turks. While not as popular as the earlier crusades, these efforts nonetheless mobilized a number of important European religious and lay figures. A 1480 letter of indulgence, issued by the noted theologian Angelo Carletti da Chivasso, absolved a Florentine citizen of his sins in exchange for a contribution in a war against the Ottomans, commonly depicted as “barbarians,” “Scythians,” or, in this document, “Trojans seizing the shores of Italy.”

Questions to Consider:

- What kinds of arguments did Pope Pius II advance in his letter to sultan Mehmed II? What could be some intended and assumed audiences for this appeal?

- What kinds of terms do the two documents use to refer to the Ottomans? How did the Ottoman conquests of the fifteenth century shape religious life in Europe?

Worlds of Captivity & Slavery

As Ottoman sultans directed new military campaigns in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, they seized not only land, but also tens of thousands of mostly Christian captives across the Mediterranean and Eastern Europe. These men, women, and children were taken into the Ottoman society in a wide variety of ways. Many were sent to cities like Istanbul as domestic servants and concubines; others worked as masons, weavers, scribes, translators, or musicians; others still were sent to farms and mines as laborers. Across the Mediterranean, many captives were kept as galley slaves.

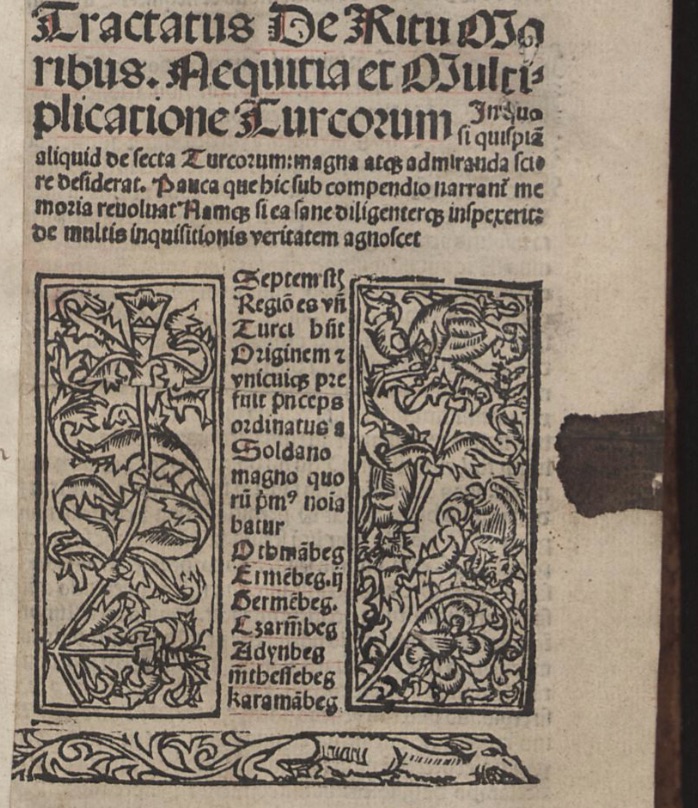

Frequent trade, religious conversion, ransom exchanges, manumission, and escapes meant that many captives crossed Ottoman-European boundaries. The first item below presents a glimpse into these intertwined histories. When the Ottoman army conquered southern Transylvania in 1438, they captured a young man who came to be known as Georgius of Hungary (1422-1502). Georgius spent some twenty years as a slave in the Ottoman Empire, serving several Muslim masters in different roles before finally making a successful escape in 1458, eventually settling in Rome. His much-cited book provided Europeans with new information about Ottoman social and especially religious life. Georgius of Hungary stressed the dangers of conversion to Islam, a religion that he appears to have studied closely through his everyday interactions with Muslim merchants, dervishes, and urban dwellers.

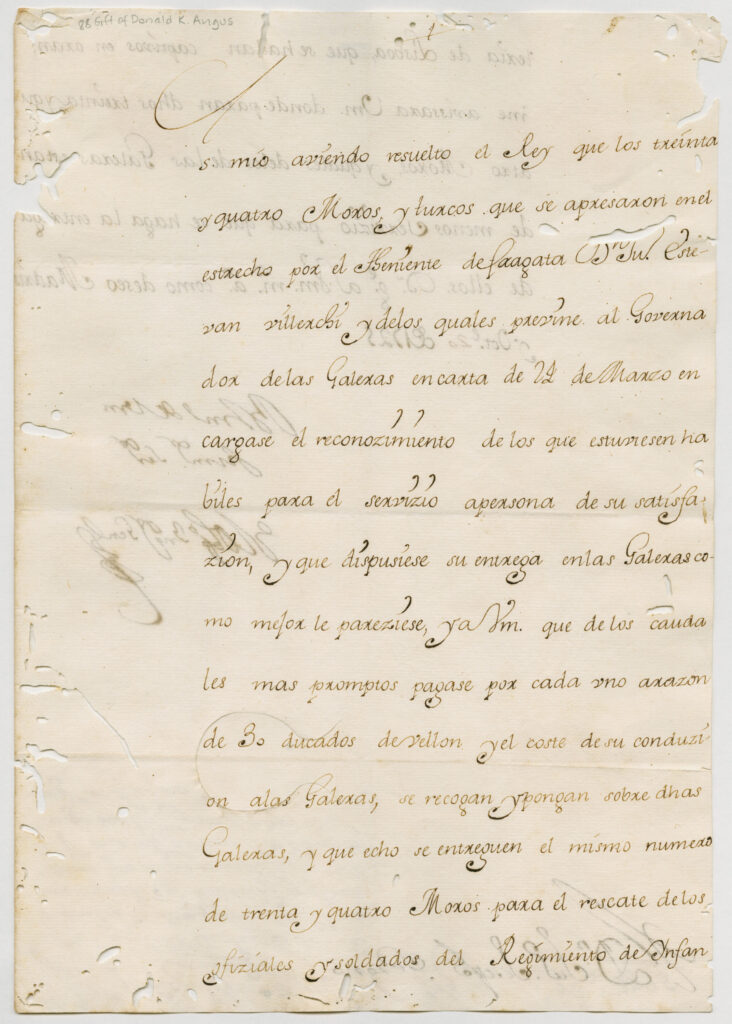

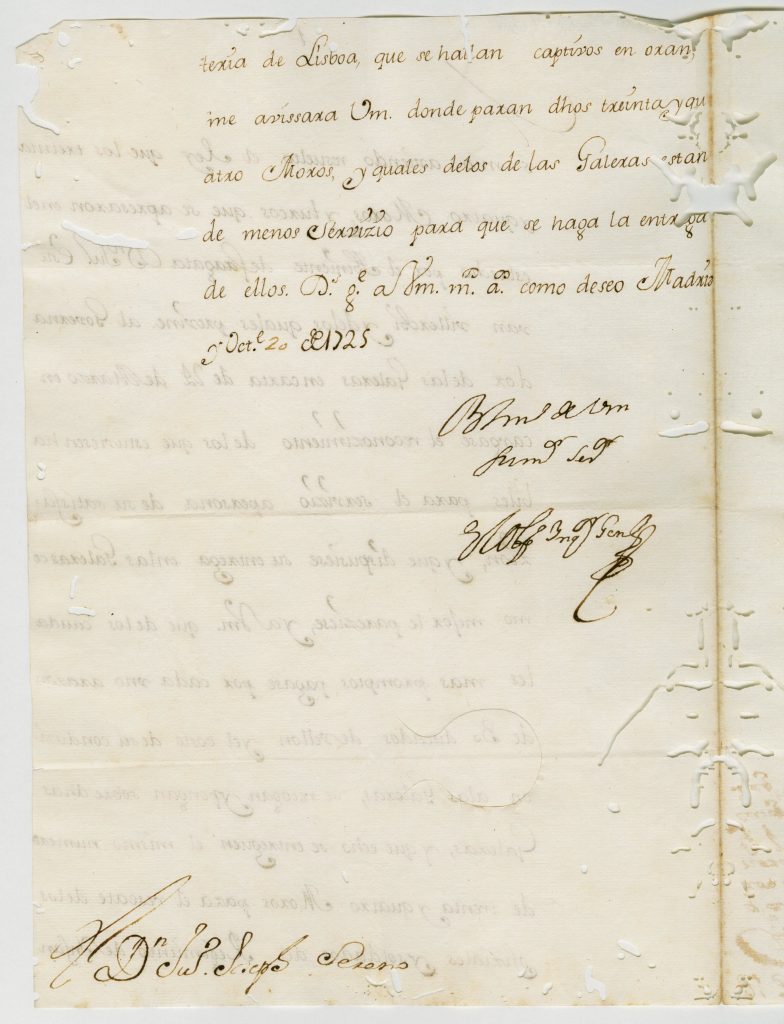

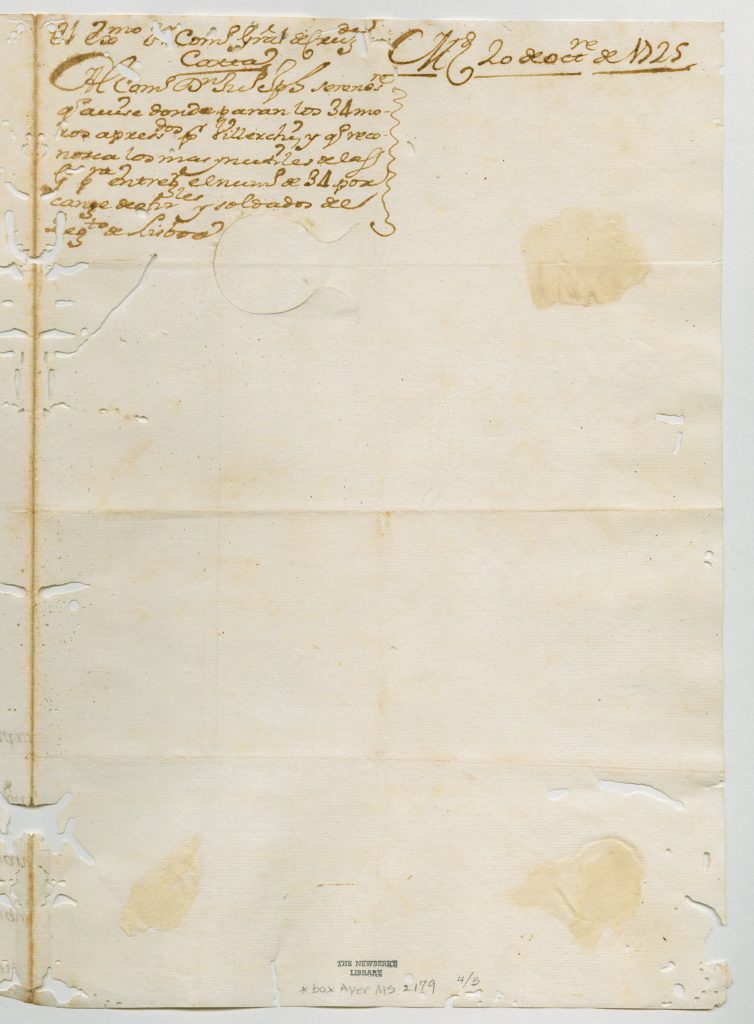

In border areas like Hungary and especially in the Mediterranean, European and Ottoman actors continued to engage in slavery and prisoner-of-war exchanges throughout the early modern period. Venetian, French, Spanish, and other Western European ships often captured, enslaved, and traded Muslim captives across the Mediterranean. For example, a series of Spanish letters from the 1720s and 1730s shows the discussions between the Spanish royal and naval officials regarding some thirty to fifty “Moorish and Turkish” captives. The document below discusses the sale of some Muslim slaves while considering others for ongoing ransom exchanges.

Selection: Letter concerning Muslim and Turkish Prisoners (1727-1737).

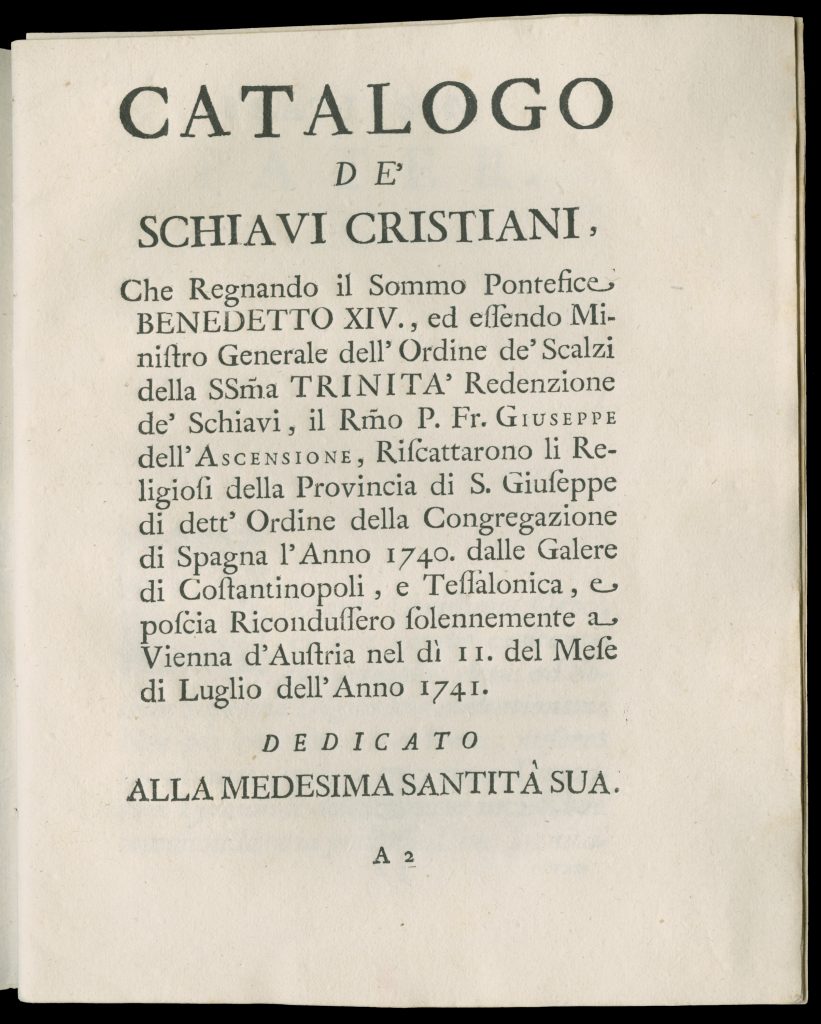

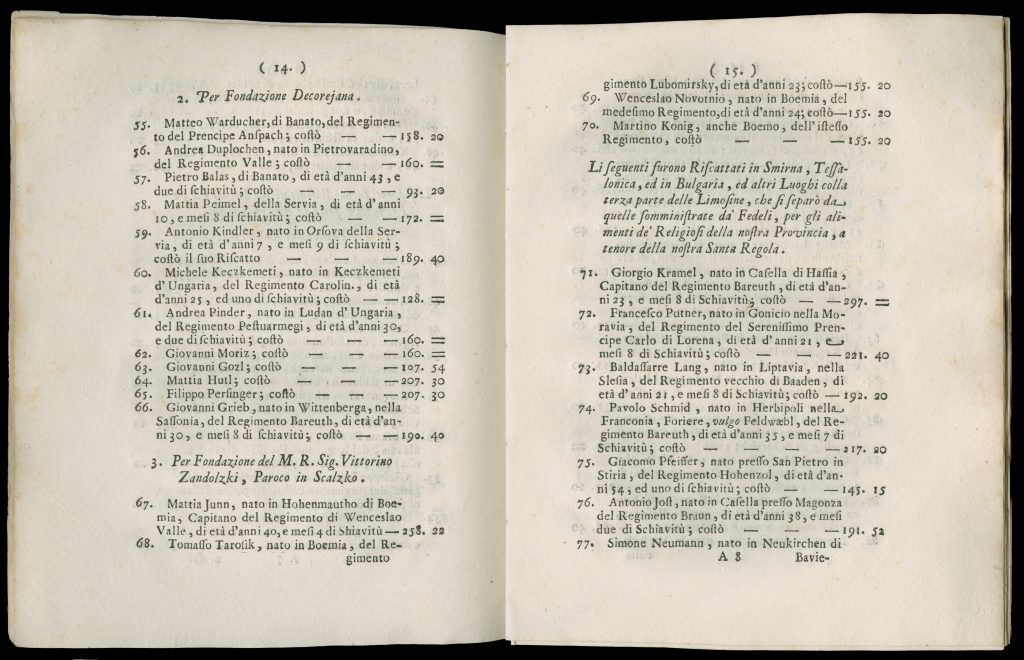

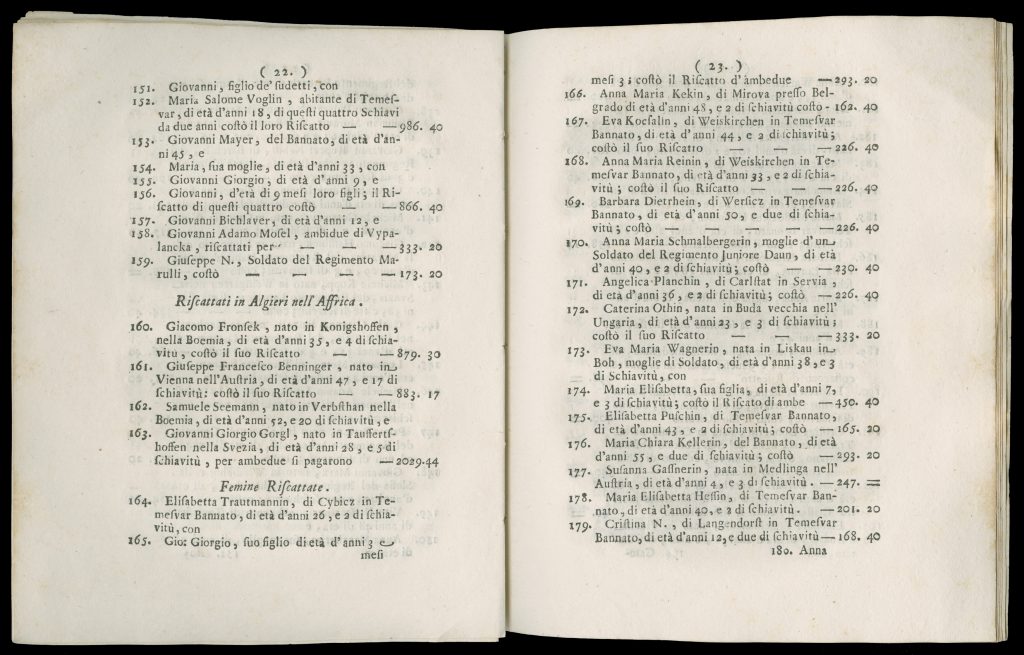

In the Ottoman Empire, European Christian captives were sometimes freed through diplomatic negotiations and redemption campaigns by religious orders. In the third document, the Trinitarian religious order published a list of Christian prisoners redeemed from captivity in Constantinople, Thessaloniki, Smyrna, and other Ottoman cities in 1740 (shortly after the conclusion of a major Habsburg-Ottoman war). The list shows the names, ages, home regions, duration of captivity, and ransom amount paid to the Ottomans. Europeans of prominent rank, such as army commanders or court officials, were prime candidates for such rescue missions; this list also names the women and children included in this campaign.

Selection: Antonius ab Angelis, Catalogo de’ schiavi cristiani (1741).

Questions to Consider:

- What terms does Georgius of Hungary use to depict the Ottoman Empire in the title of his book? What kind of information would Georgius have been to relate to European audiences?

- What kinds of experiences, stories, and knowledge did captives bring with them as they crisscrossed European and Ottoman domains?

- Examine the list of captives from 1740. Are there any patterns that you notice as you look at the names, ages, and ransom amounts on this list?

Depicting the Ottomans

During the Renaissance, many European writers, painters, and intellectuals became keenly interested in documenting the contemporary affairs and the longer history of the Ottoman Empire. Two items below present some common themes in European depictions of the Ottomans.

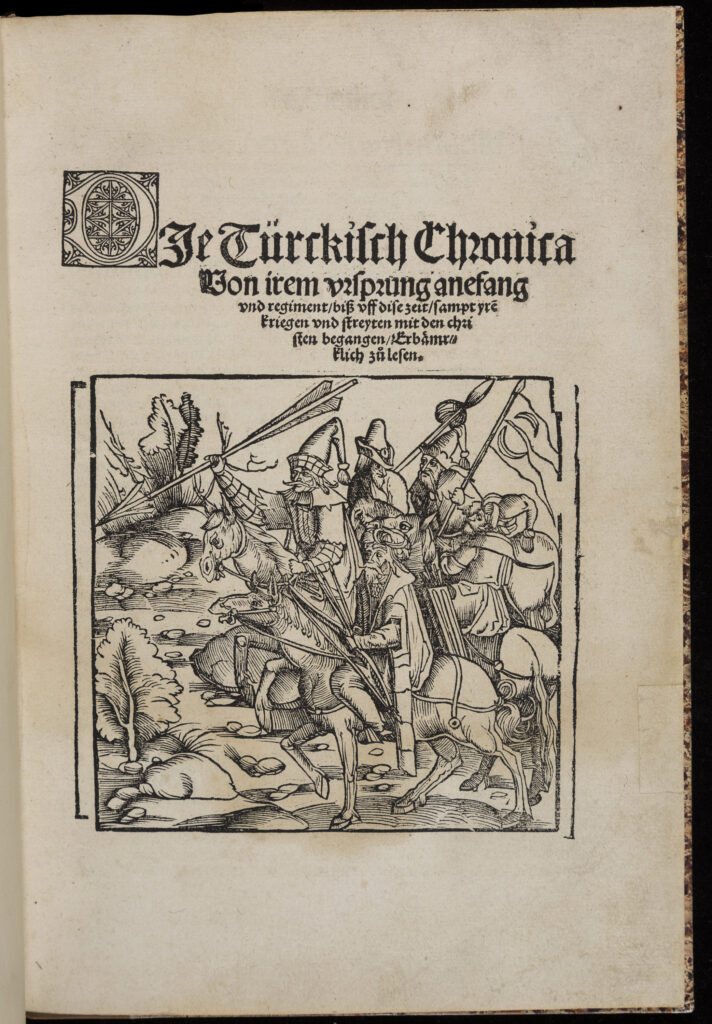

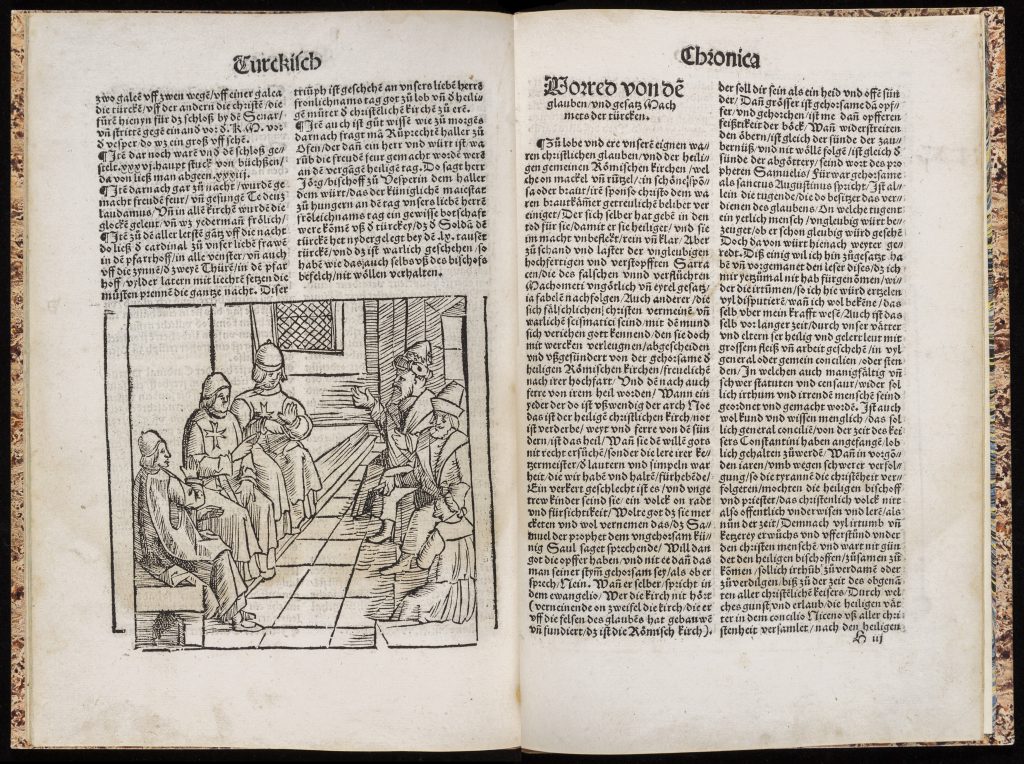

Selection: Johannes Adelphus, Die türckisch Chronica von irem Ursprung Anefang und Regiment (1513).

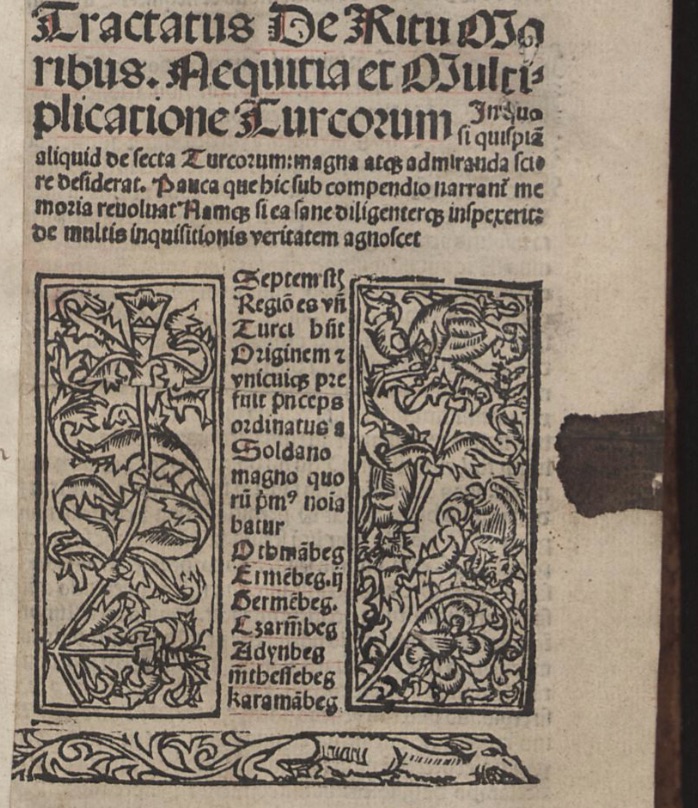

The advancement of the Ottoman armies into Central Europe and the Mediterranean meant that most Europeans usually associated the Turks with war, violence, and conquest. In the first document below, the German physician and chronicler Johannes Adelphus depicted in 1513 the Ottomans primarily as a military force marching on horses or attacking islands with their navy. In other woodcuts, Adelphus also highlighted diplomatic negotiations carried out by Ottoman and Venetian officials.

Selection: Pietro Bertelli, Vite degl’imperatori de Turchi con le loro effiggie intalgiate in Rame (1599).

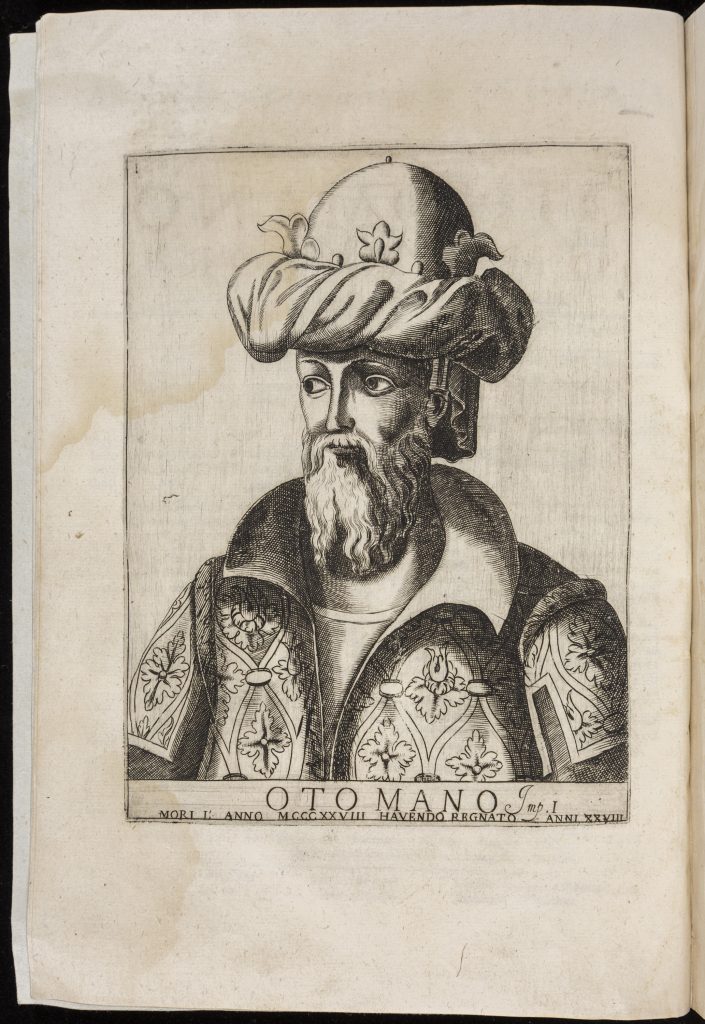

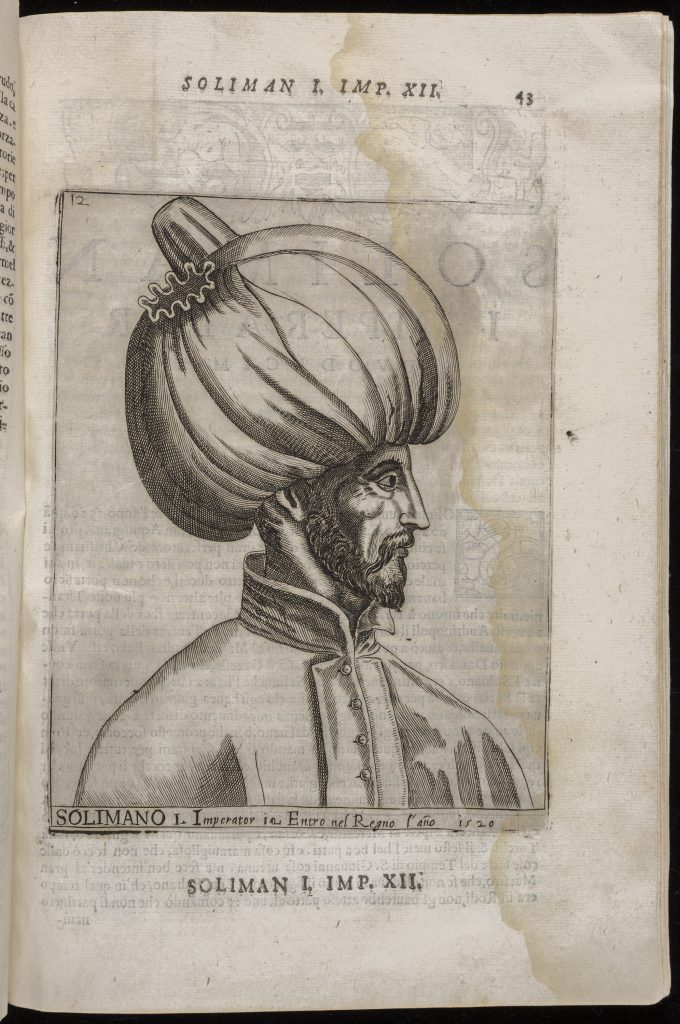

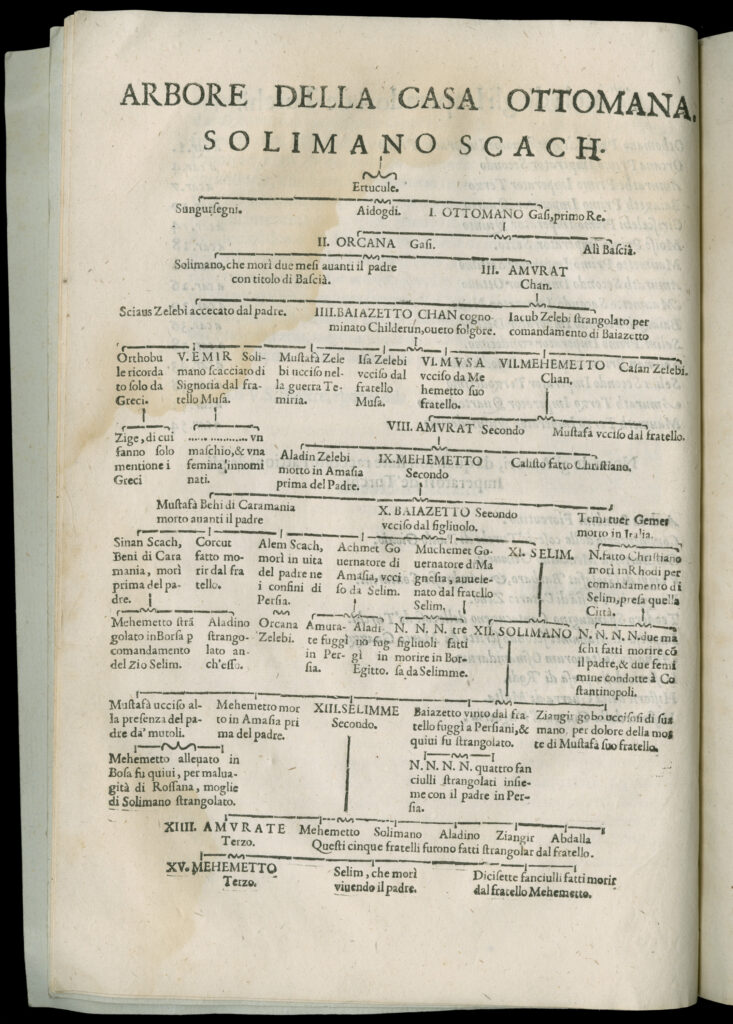

Other works capitalized on the growing European interest in the lives of Ottoman sultans by providing genealogies of the Ottoman dynasty and visual depictions of individual rulers. In the second item, the Italian artist and writer Pietro Bertelli (ca. 1571-1621) composed biographies and full-page portraits of fifteen Ottoman sultans, from Osman, the founder of the Ottoman dynasty, to Mehmed III (1522-1603).

Questions to Consider:

- What kinds of imagery does Adelphus use in his depiction of the Ottomans?

- How do the sultans appear in Bertelli’s portrait? What aspects are emphasized? What is the overall frame or mood of these portraits?

- How do these depictions reflect the interests of the European artists and audiences?

“The Turks” in Fiction and Fact

Building on these long histories of European-Ottoman interaction, many writers in Austria, Italy, France, and England incorporated a variety of “Turkish” characters into their histories, plays, operas, and novels.

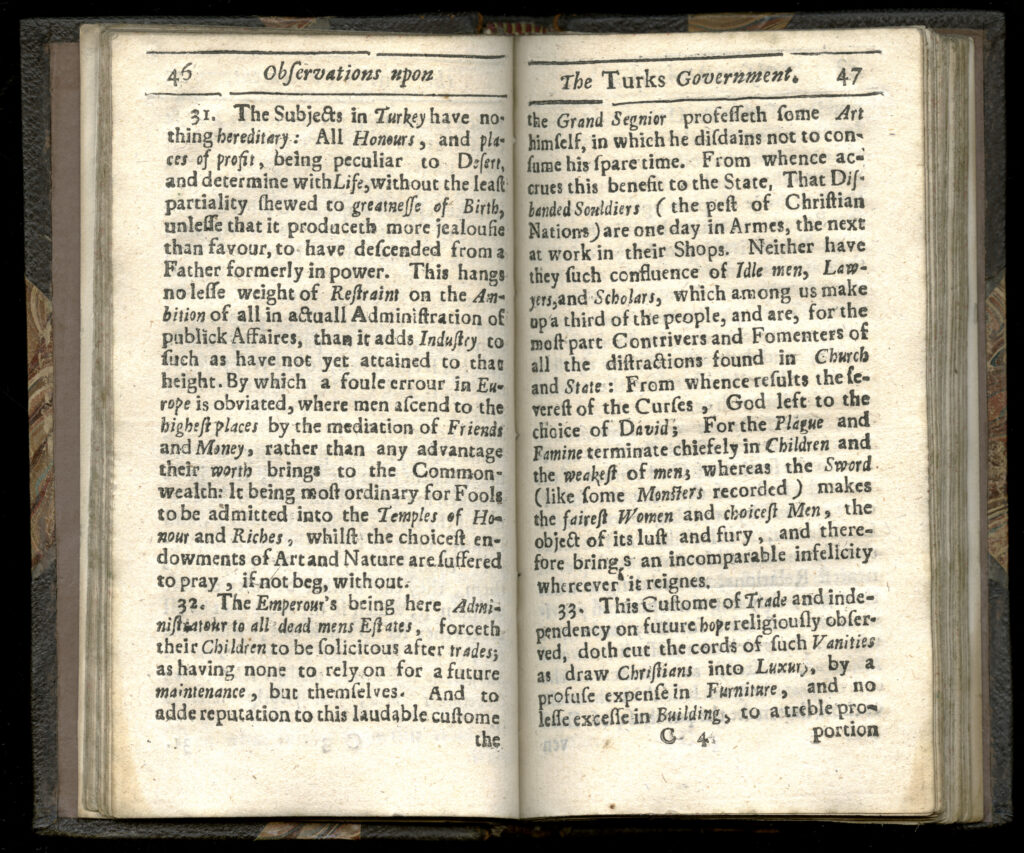

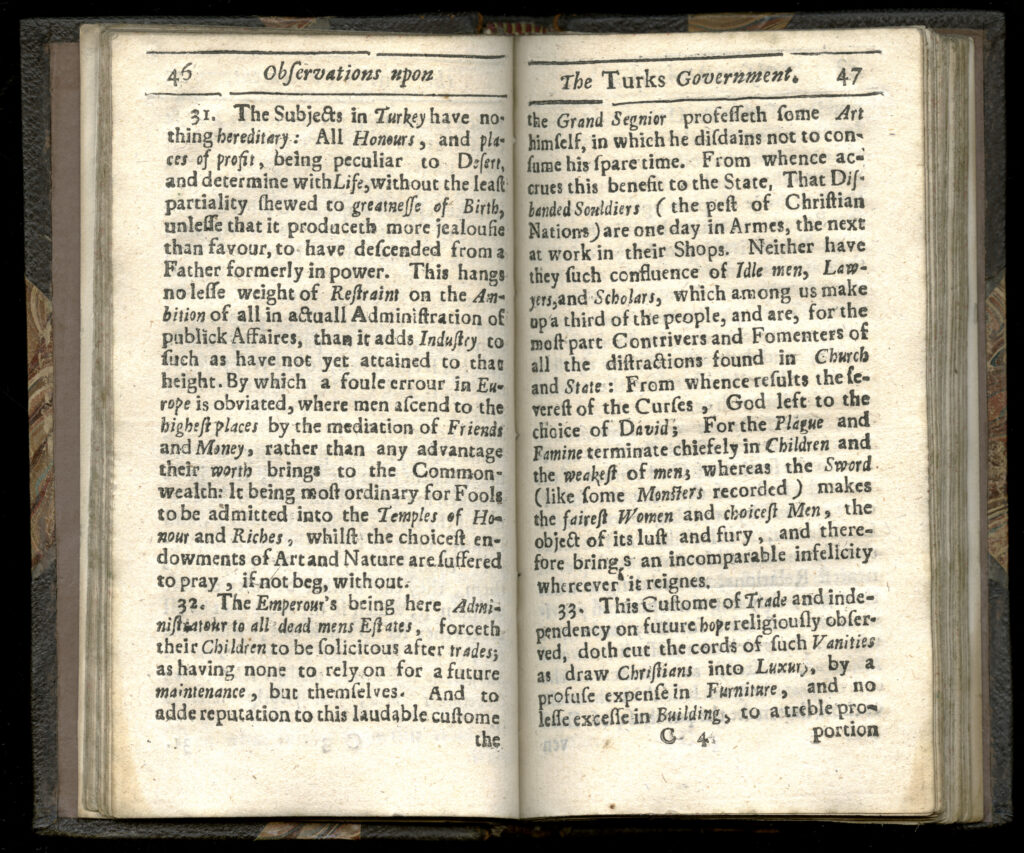

Many commentators in early modern England, for example, used and sometimes invented examples from Ottoman history to advance their own political causes or criticize opposing viewpoints. In the first item below, essayist Francis Osborne used (and misrepresented) aspects of the Ottoman court to make an argument in favor of meritocracy while criticizing governments in Europe, “where men ascend to the highest places by the mediation of Friends and Money, rather than any advantage their worth brings to the Commonwealth.”

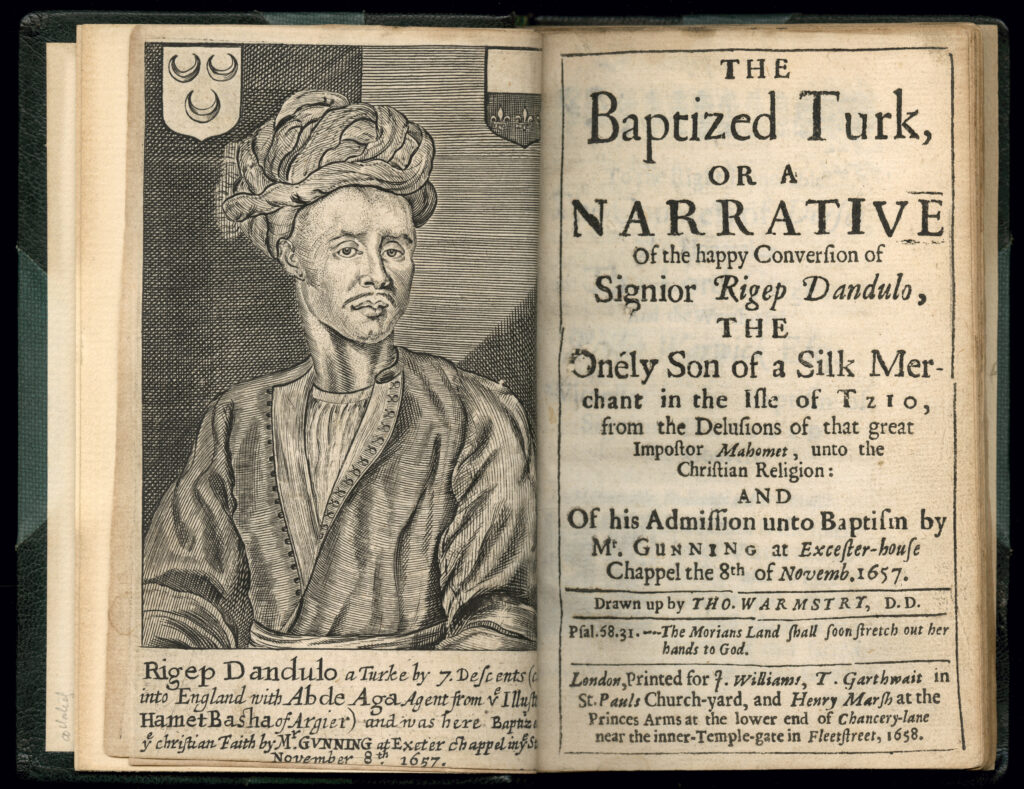

Selection: Thomas Warmstry, The Baptized Turk, or, A narrative of the happy conversion of Signior Rigep Dandulo (1658).

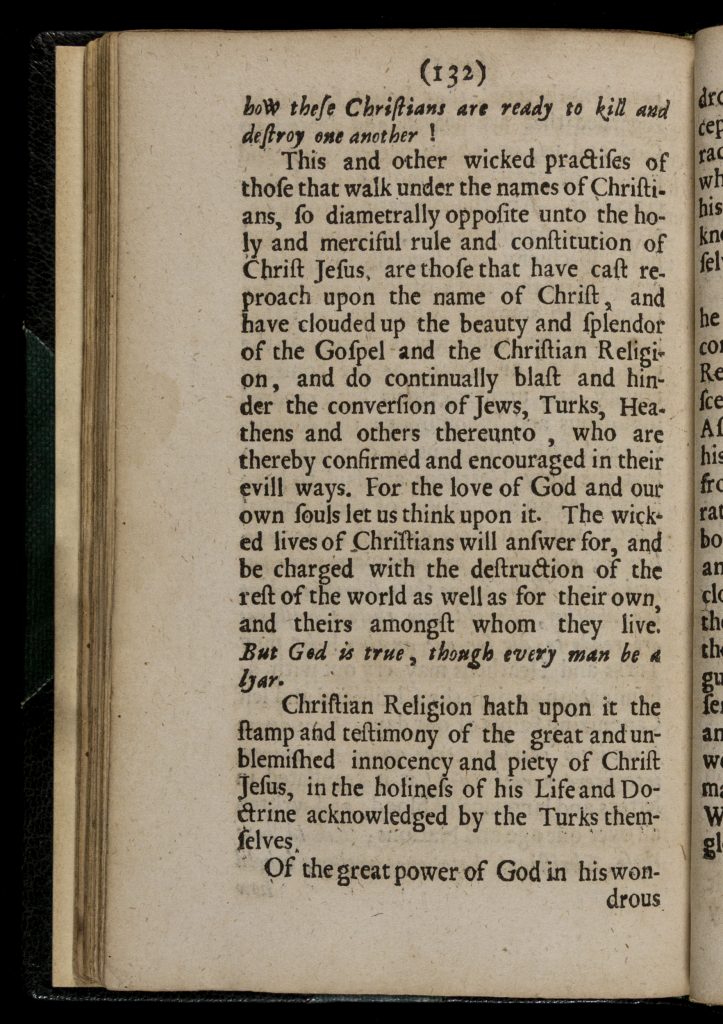

Other English writers spent considerable time debating the conversion of the Turks to Christianity and warning against the dangers of Christians converting to Islam. In the second item below, minister Thomas Warmstry focused on the conversion of one Ottoman Muslim merchant (an event that reportedly occurred in London in 1657) to highlight the advantages of the Anglican faith over its other Christian rivals, an argument that he suggested as relevant for “the conversion of Jews, Turks, Heathens, and others.”

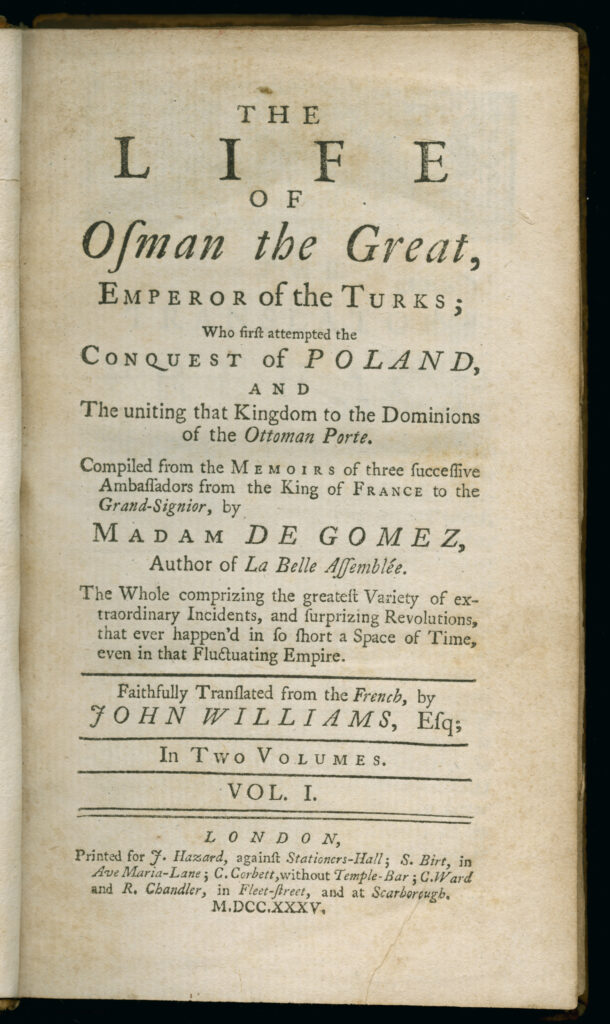

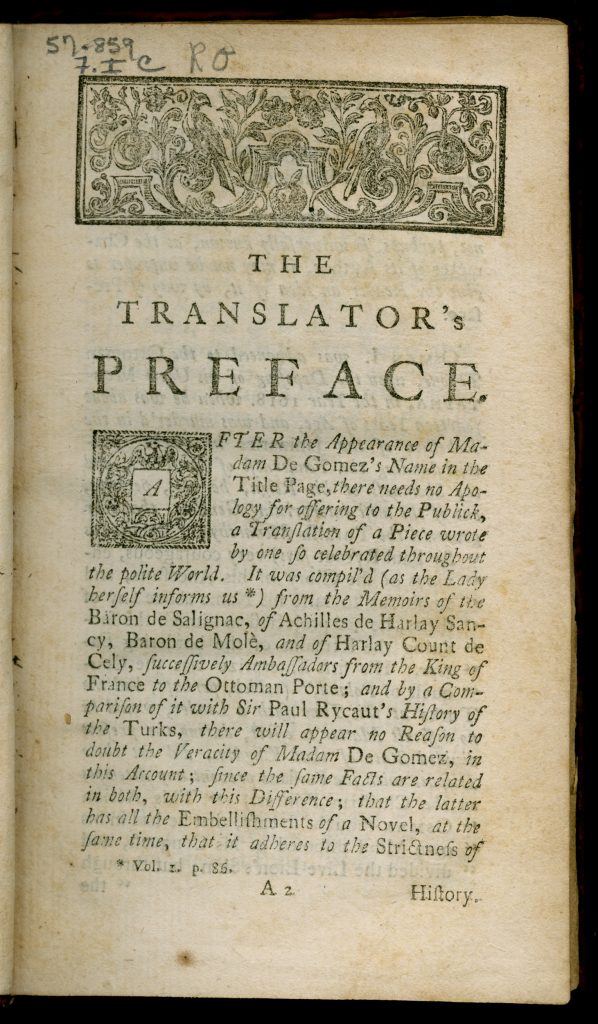

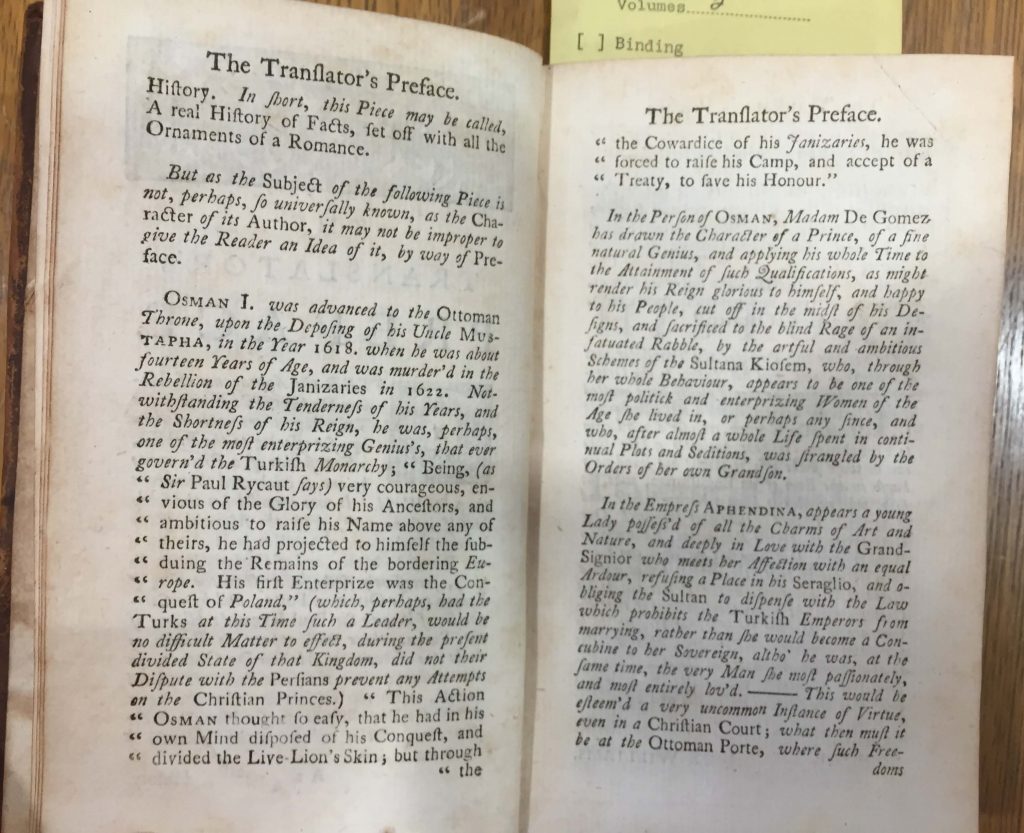

In France, Madame de Gomez (née Poisson, 1684-1770) deftly used real events from Ottoman history as a stage for elaborating numerous romantic and dramatic stories. In her interpretation of the reign of sultan Osman II, presented in the third source below, Gomez repeatedly highlighted the power that Ottoman royal women—like the famous queen mother Kösem (1589-1651)—exercised over political affairs. As the preface to the English translation states, Gomez’s work “may be called A real history of facts, set off with all the ornaments of a romance.”

Selection: Madame de Gomez, The Life of Osman the Great, Emperor of the Turks (1735).

Questions to Consider:

- What historical experiences, stories, and perceptions could European authors draw on in order to create new “Turkish” characters in their works?

- What political and religious overtones can you detect in the writings of Osborne and Warmstry? How did these English authors use examples from Turkish or Ottoman history?

- How does the preface to Madame de Gomez describe the Ottoman queen-mother Kösem? What does Kösem’s fame as “one of the most politick and enterprising Women of the Age she lived in, and perhaps any since” suggest about Gomez’s interest in telling this story?

Further Reading

Palmira Brummett, Mapping the Ottomans: Sovereignty, Territory, and Identity in the Early Modern Mediterranean. Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Margaret Meserve, Empires of Islam in Renaissance Historical Thought. Harvard University Press, 2008.

Géza Dávid and Pál Fodor, eds., Ransom Slavery along the Ottoman Borders (Early Fifteenth – Early Eighteenth Centuries). Leiden: Brill, 2007.