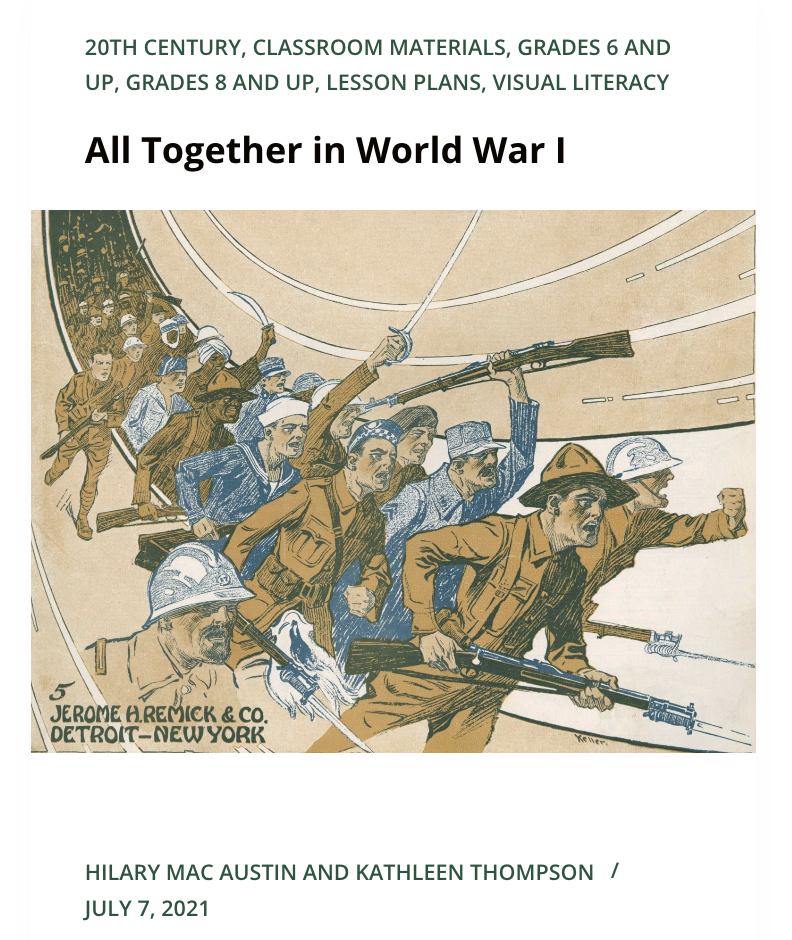

Curriculum Connections: Propaganda, World War I, Visual Literacy

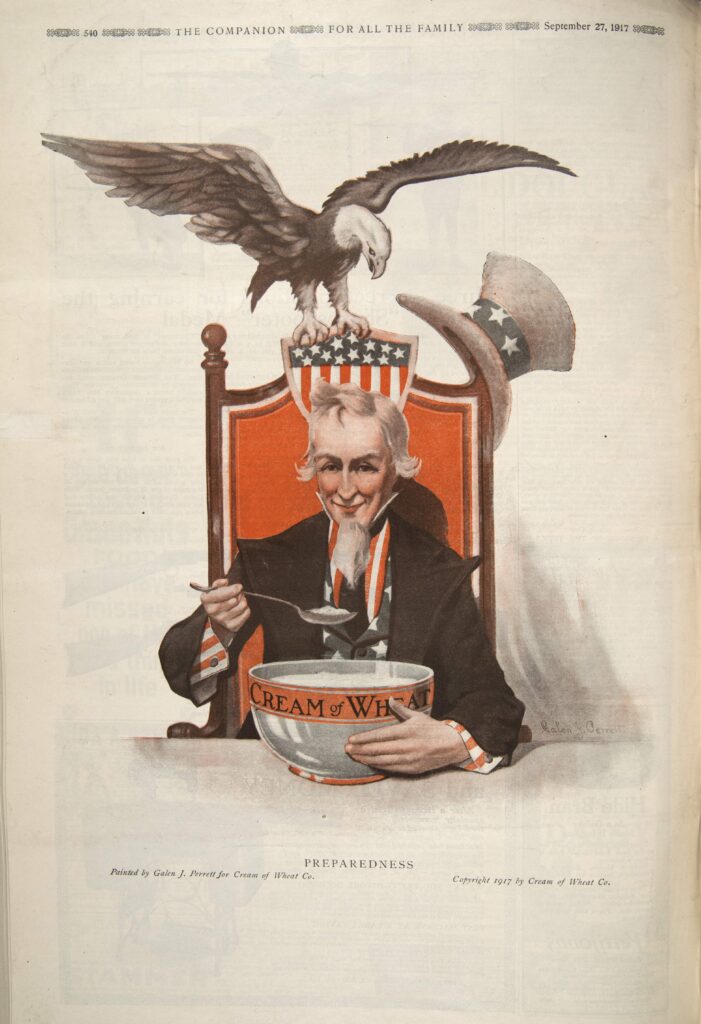

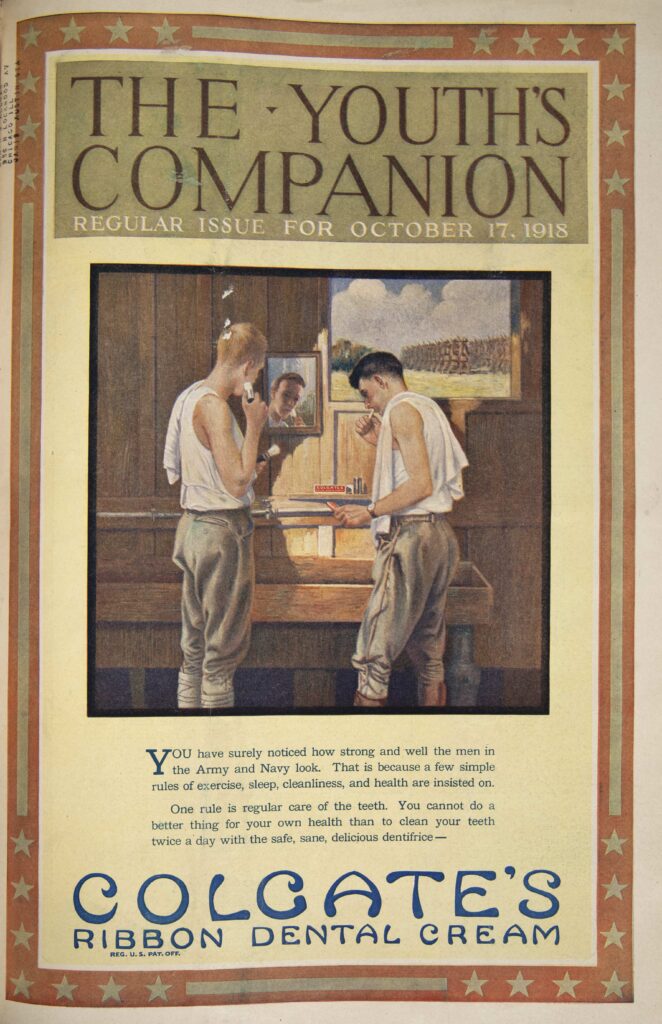

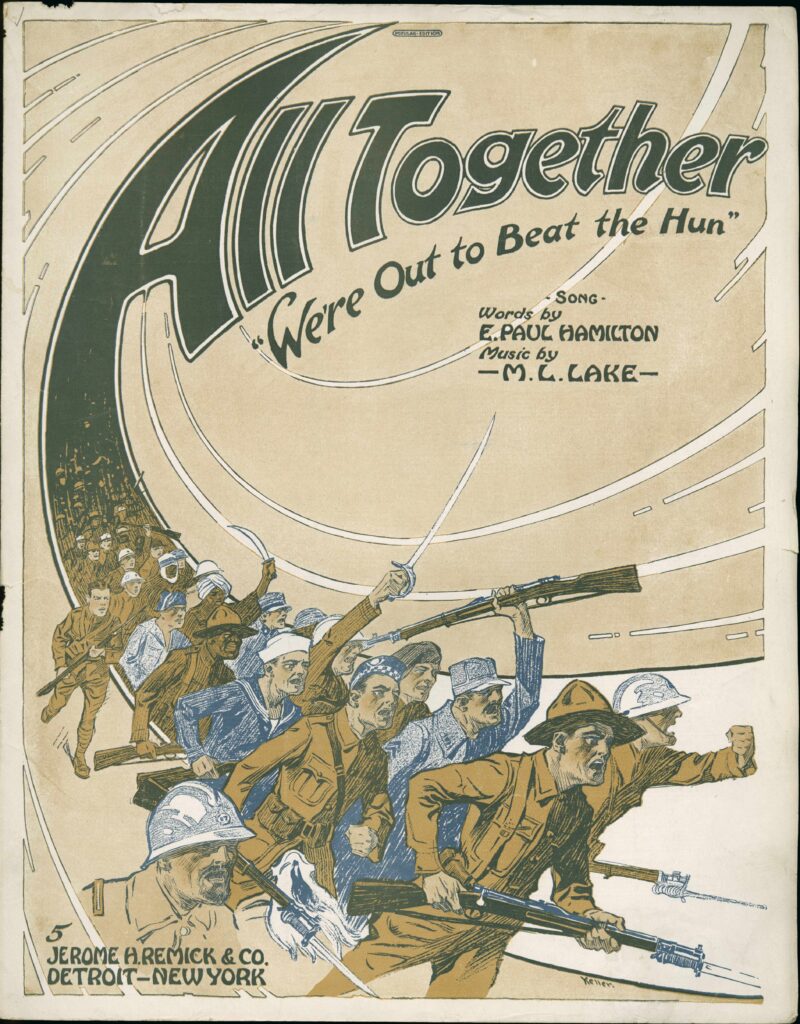

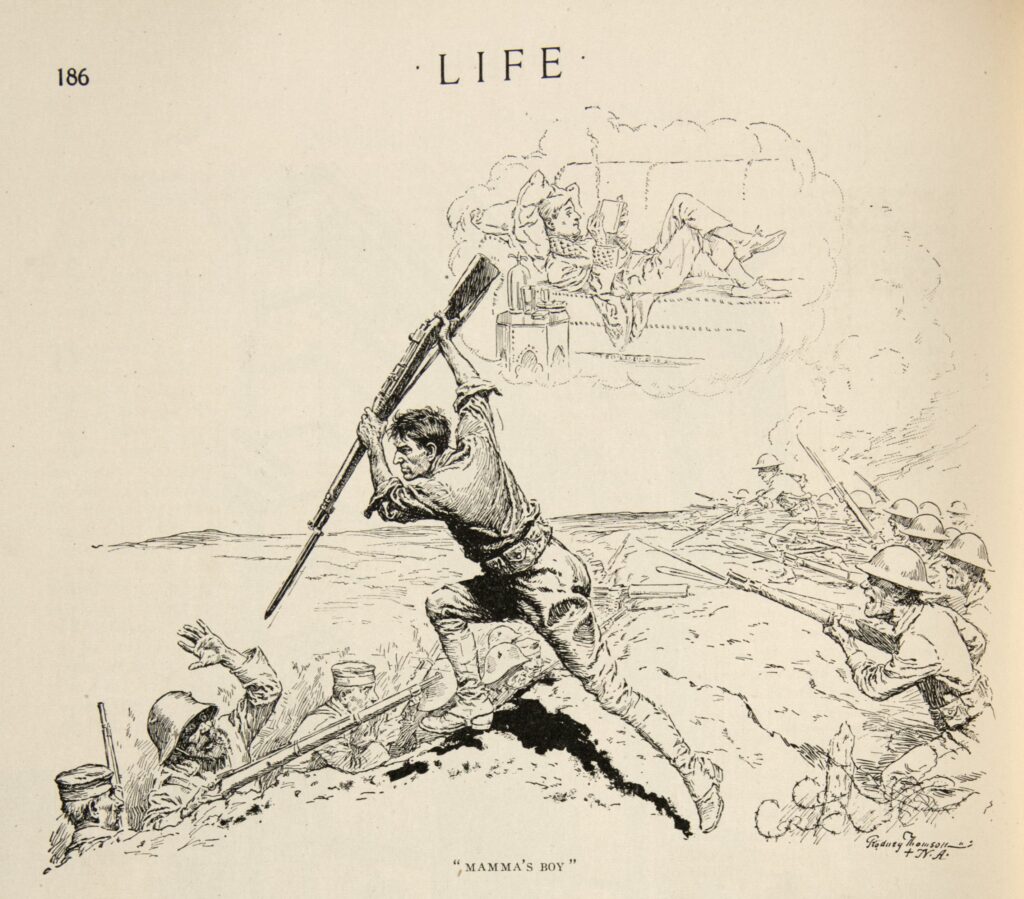

Essential Question: How did popular publications encourage American support for the war effort?

Historical Context

When the Great War (as World War I was known at the time) began in Europe in 1914, few Americans believed that the United States should get involved. President Woodrow Wilson issued a proclamation of neutrality, urged Americans to remain “impartial in thought as well as action.” Public support for neutrality, however, was challenged by the German U-Boat attacks on American ships, including the May 1915 attack on the British passenger ship the Lusitania in which 128 Americans died. As the presidential election of 1916 approached, Wilson emphasized “preparedness” in speeches and parades designed to show that he and the nation were not timid, but ready for war, if necessary. At the same time, he campaigned and won the 1916 election under the slogan “He kept us out of the war.”

By the spring of 1917, the Allies were running low on money and supplies, and Allied troops had been decimated. In March, German U-boats sunk four American merchant ships. On April 6, 1917, the United States formally declared war and, a year and a half later, secured the Allied victory. Ten million soldiers (including 50,000 Americans) and nearly seven million civilians had lost their lives.

While World War I was not fought on U.S. soil, it had an enormous social and cultural impact on the nation. President Wilson made a concerted effort to maintain public support for his policies through propaganda as well as legal prosecution. Americans participated in countless parades and commemorative events to demonstrate, first, preparedness, then support for the war. In April 1917, soon after the American declaration of war, his administration formed the Committee on Public Information (CPI) and hired writers and speakers to promote the war effort throughout the country. People who opposed the war, such as reformer Jane Addams and Senator Robert La Follette, were subject to public ridicule. With the passage of the Espionage Act (1917) and the Sedition Act (1918), critics of the war effort became subject to fines and jail sentences.

Today you will examine a series of documents to answer the essential question: How did popular publications encourage Americans to support the war effort?

To do today:

- Examine the documents, paying particular attention to the source notes and the context of each.

- Close read the documents to determine the purpose of the advertisement or piece of art. What is the author’s message? What strategies does the author use to communicate this message? What evidence do you have to prove that this was the author’s purpose?

- Choose two documents whose message and strategies you will compare in detail, and answer the essential question in a well developed paragraph response: “How did popular publications encourage Americans to support the war effort?”

- Use a word document to write your response. Use spelling/grammar check, proofread your work, be sure to USE EVIDENCE (symbols, quotes, specific details) to support your answer. Then, email your response to your teacher by the end of the period.