Introduction

“Riots and Protest: Chicago’s Legacy of Conflict” explores Chicago’s past through one of its defining characteristics: conflict. This Digital Collection for the Classroom examines five different eras of conflict spanning more than 150 years of the city’s history. In addition to exposing complex local dynamics, stories of protest in Chicago illuminate broad themes in United States history. Explosive tensions along ethnic and class lines in nineteenth-century Chicago reveal the impacts of the United States’ growing industrial capitalism. The resulting wealth inequalities elicited a range of responses in America, ranging from reform to revolution. The International Workers of the World—headquartered in Chicago—represented one of the nation’s more radical movements in the early twentieth century. As the Great Migration of African Americans to Northern cities accelerated after World War I, Chicago provides a case study of how Black communities encountered rampant, enduring racism and responded with civil rights activism and uprisings. Then, Indigenous activism in 1970s Chicago reflected the consequences of United States policies of displacement and genocide against American Indians as well as continued Indigenous survival and resistance. How do primary source documents tell stories about the past? Whose voices are elevated and whose are silenced? When do we call a conflict a “riot” or “protest,” and why?

In addition to revealing local stories and broad trajectories in United States history, the sources in this collection offer an opportunity to compare and contrast dissent over time. Many protest actions—both violent and nonviolent—aimed to challenge the status quo, such as ethnic and racial discrimination and economic inequality. At the same time, groups that challenged dominant powers in Chicago often experienced distinct histories of oppression and resistance that shaped their approach to protest. In different times and situations, protest could emerge as planned events, strategic organization, or as urgent uprisings. Many movements produced a distinct visual culture to further communicate a movement’s message. Meanwhile, the responses of the powerful in Chicago in defense of the status quo sometimes varied, but often involved deploying police to violently subdue protesters.

Finally, this collection allows us to ask how sources shape our memory of past conflict. How do primary source documents tell stories about the past? Whose voices are elevated and whose are silenced? When do we call a conflict a “riot” or “protest,” and why? The questions apply to the current day, as we continue to document, process, and remember protests in the twenty-first century.

Guiding Questions:

- How do protests in Chicago connect to broader conflicts in United States history?

- What are the similarities and differences between the protests presented in this collection? Consider the causes of conflict, protests’ goals, messages, and visual culture, the response of Chicago leaders, and the role of police.

- How are Chicago protests remembered? How do primary source documents inform our understanding of past conflict? When and why are conflicts labeled protests, riots, or otherwise?

Ethnic and Labor Conflict in Nineteenth-Century Chicago

The growth of two major transportation networks—canals and railroads—fueled the expansion of the United States across Indigenous land in North America in the nineteenth century. By 1855, Chicago emerged as a crucial intersection for both networks. With the completion of the Illinois and Michigan Canal in 1848, ships could pass between the Mississippi River and the Great Lakes through Chicago. Meanwhile, Chicago businessmen and leaders promoted the city as the ideal hub for an expanding system of railroads. Constructing canals and railroads demanded heavy labor that was fulfilled by the city’s growing German and Irish populations. Germans in particular settled on the North Side of the city and established taverns where the community could come together to eat, drink, and share news.

Some elite Chicagoans viewed German newcomers with suspicion, blaming them as the cause of disorder and crime in the city. In a thinly veiled attack on the city’s immigrant communities in 1855, Mayor Levi Boone attempted to close saloons on Sundays, raise liquor fees, and shorten liquor licenses. Many Germans were arrested for violating the new laws. On April 21, a group of German protesters from the North Side marched to City Hall in defense of their arrested neighbors. In anticipation, Boone placed cannons in front of the government building, deputized additional policemen, and sent them to intercept the march. The mayor’s forces confronted the protesters on the Clark Street Bridge, and the ensuing brawl left one protestor dead and dozens more arrested. The conflict proved empowering for the city’s German immigrants and devastating for the mayor’s career. Boone did not run for re-election, liquor licenses returned to normal, and saloons reopened on Sundays. In the coming years, German Chicagoans used the so-called Lager Beer Riot as a rallying call to assert their role in the city’s politics. Elite Chicagoans, meanwhile, fearfully remembered the Lager Beer Riot as an example of the power of the city’s working class.

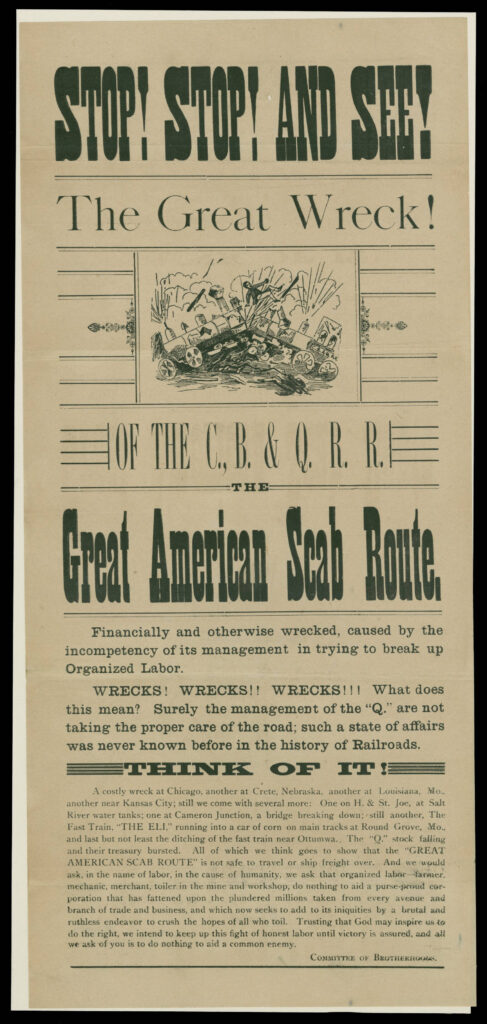

By the 1880s, railroads spread across North America and shipped livestock, grain, and other raw resources to Chicago. There, immigrants from across Europe and migrants from rural America worked in meatpacking plants and other factories to process goods and ship them to the East Coast. Businessmen, railroad barons, and factory owners grew incredibly wealthy from this new industrial capitalism, while workers held dangerous, exhausting, and low-paying jobs with little security. Throughout the late nineteenth century, workers routinely organized into unions, went on strike, and encouraged boycotts in efforts to demand better pay and working conditions. For example, engineers and firemen who worked on the CB&Q railroad went on strike in 1888 for better wages. The strike began in Chicago and spread throughout the region. The CB&Q responded by hiring replacements for strikers—called “scabs” by protesters—and hiring police and private detectives to violently defend their property. Like so many other worker protests during the era, the CB&Q ultimately refused to acknowledge unions and the strike failed. Nevertheless, industrial workers in Chicago and beyond continued to fight for the right to organize and demand better wages and working conditions well into the twentieth century.

Guiding Questions:

- In the 1856 image of Chicago, where are representations of the two major transportation networks that contributed to Chicago’s growth? Where in the illustration would German neighborhoods be located? Where is the Chicago River? Where is the Clark Street Bridge?

- How does the 1856 illustration of Chicago (pictured in the Introduction) look similar or different to how you think of Chicago today?

- What evidence does the broadside use to argue that the CB&Q’s use of scabs is irresponsible?

Radical Protest in the Early Twentieth Century

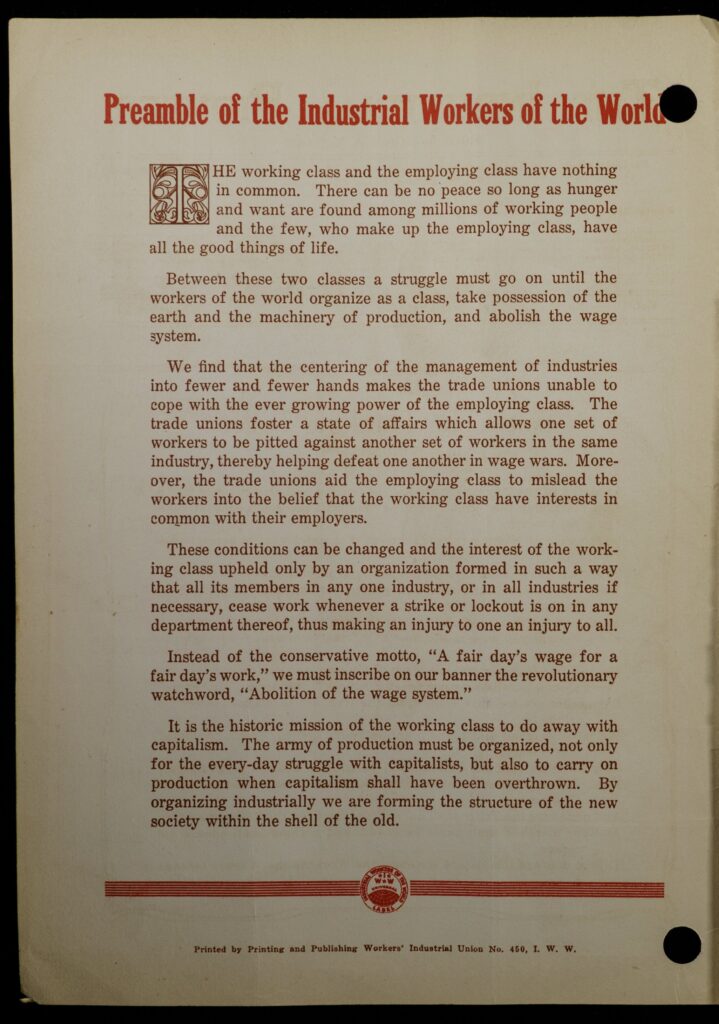

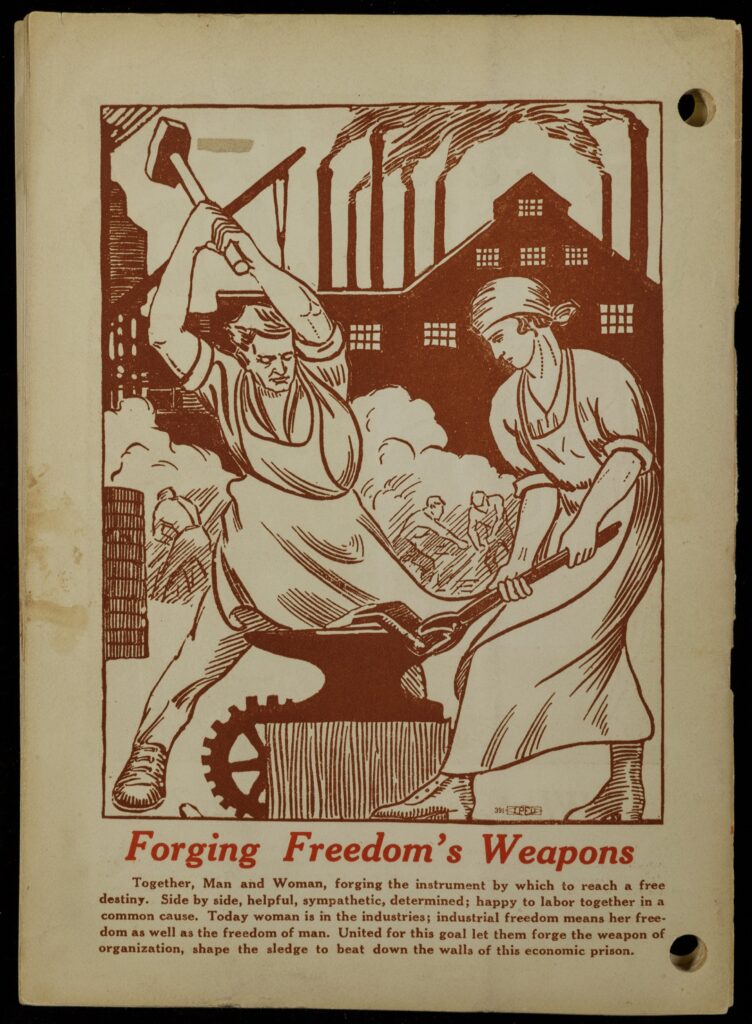

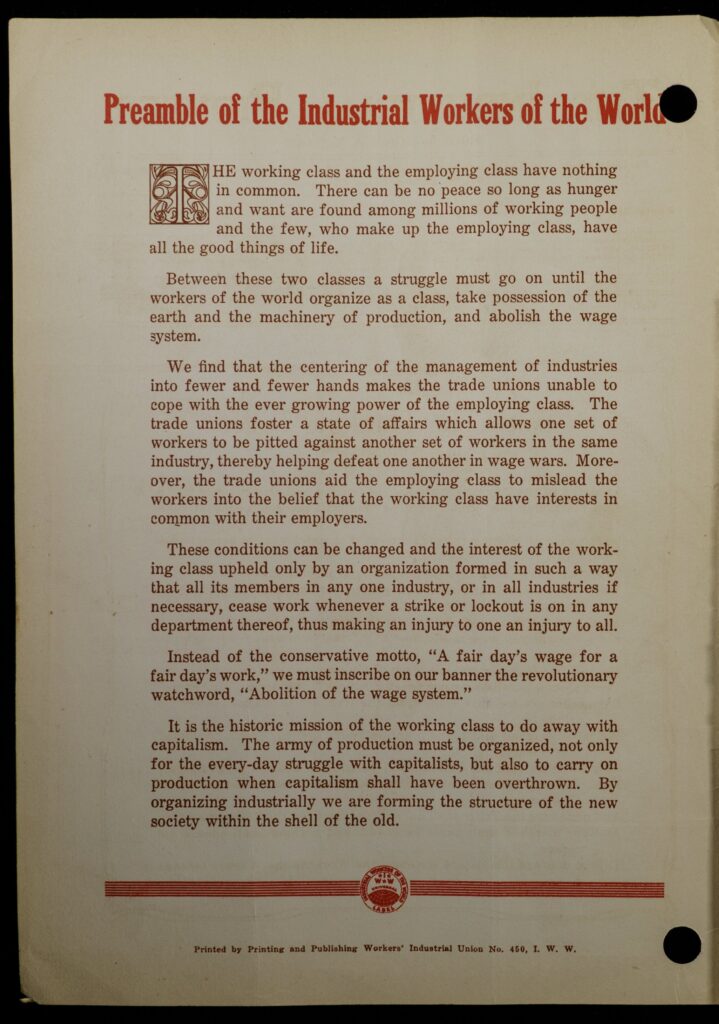

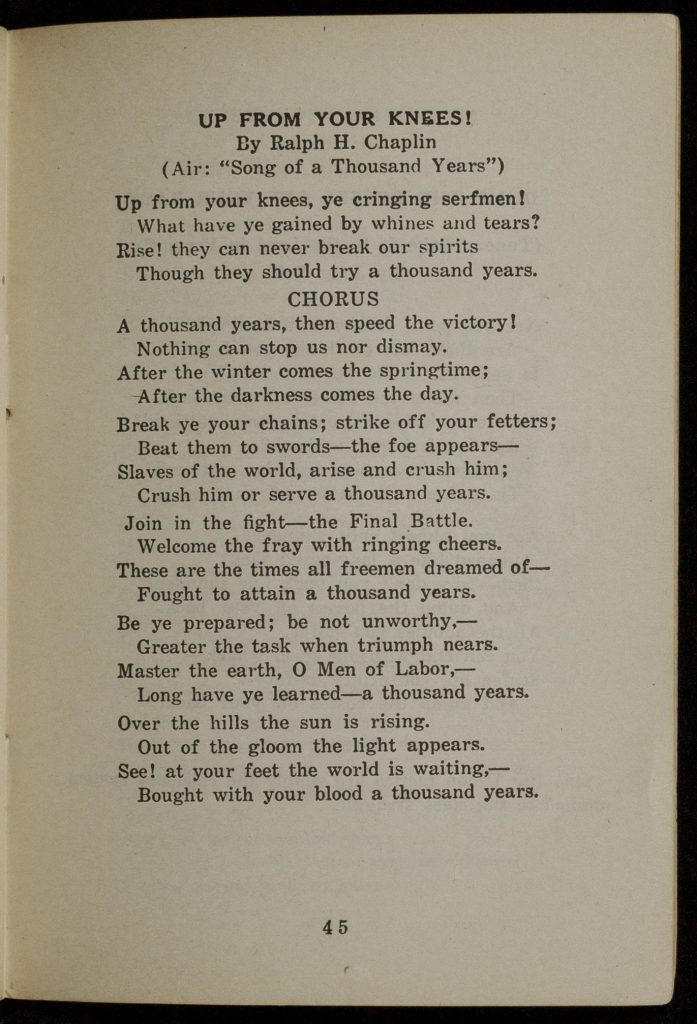

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, industrial capitalism in the United States continued to produce a few very wealthy businessmen and masses of poor, underpaid workers. Some Progressive Era activists responded by encouraging economic reform, increased social services, and a larger role for local and federal government to curb the excesses of industrial capitalism. Other labor organizers continued to form unions like the American Federation of Labor that advocated for modest gains like improved wages and working conditions. In contrast to reform efforts, more radical groups like the International Workers of the World (IWW)—commonly called Wobblies—agitated for a worker revolution to fully uproot the causes of social and economic inequality.

The IWW was founded in Chicago in 1905 and remained headquartered in the city, organizing workers and publishing periodicals like The Industrial Pioneer. The city remained a hub of radical activity until World War I, when it became a target of government surveillance and repression. Federal agents raided IWW’s headquarters in 1917, and a year later one hundred Wobbly leaders were tried and convicted before a federal judge in Chicago. The IWW continued to survive as an organization, but the relative prosperity of the 1920s continued to weaken the urgency of radical organizing in the United States. When the economy collapsed during the Great Depression of the 1930s, revolution as envisioned by the IWW and other radicals still did not take place. Instead, Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal brought many Progressive Era reforms to fruition. Despite continued obstacles, IWW sources from the early twentieth century show how the organization fought to sustain a long-term culture of revolution and continued to protest inequalities under industrial capitalism.

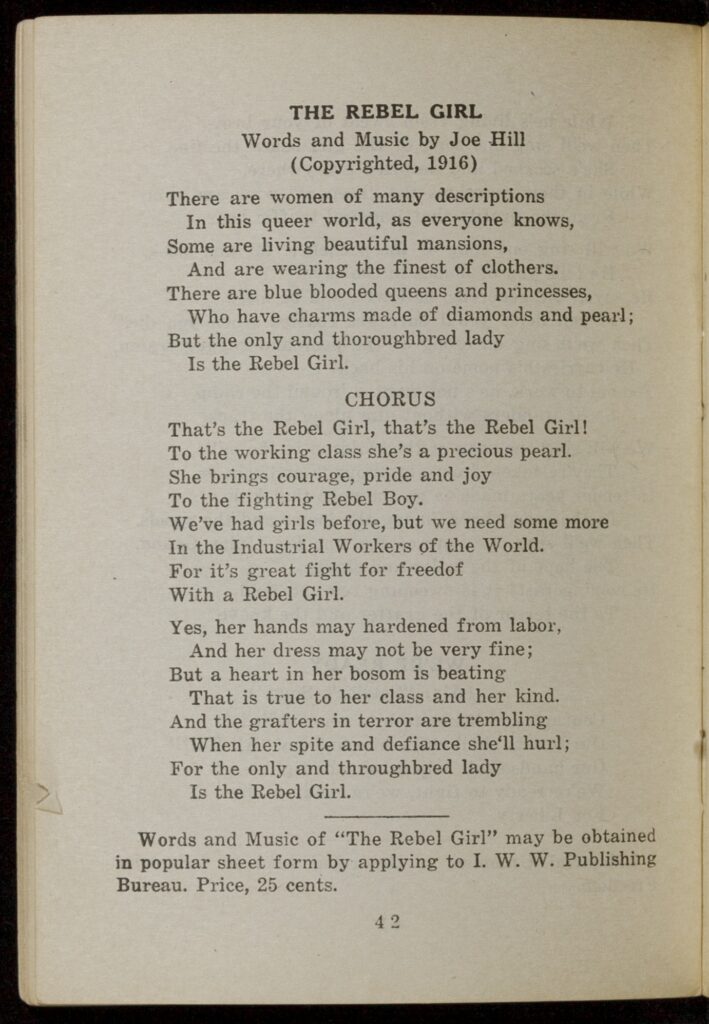

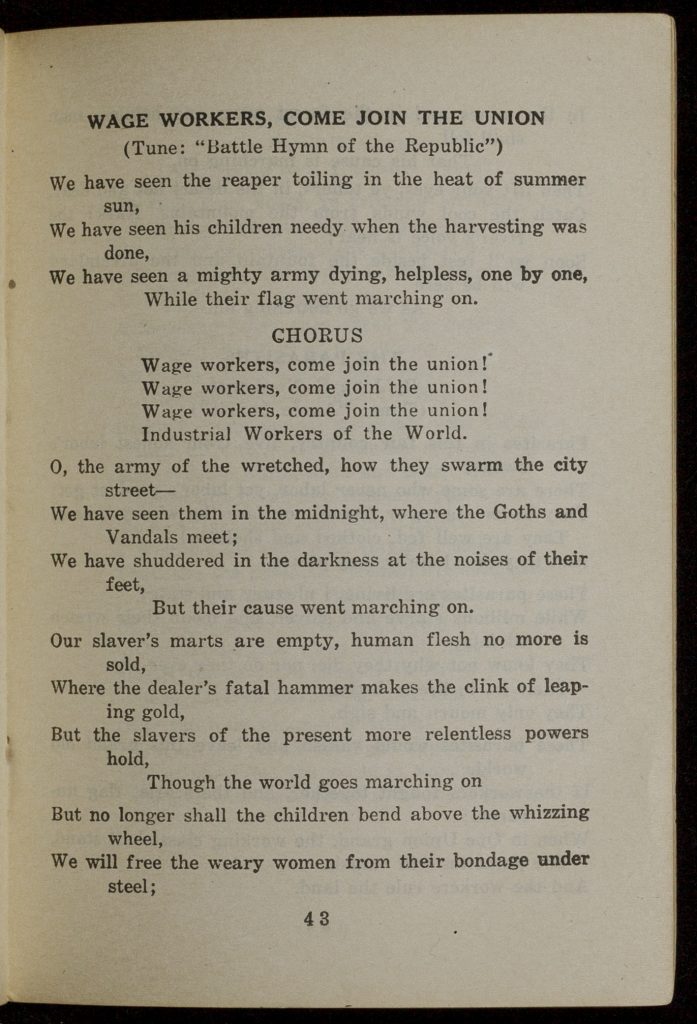

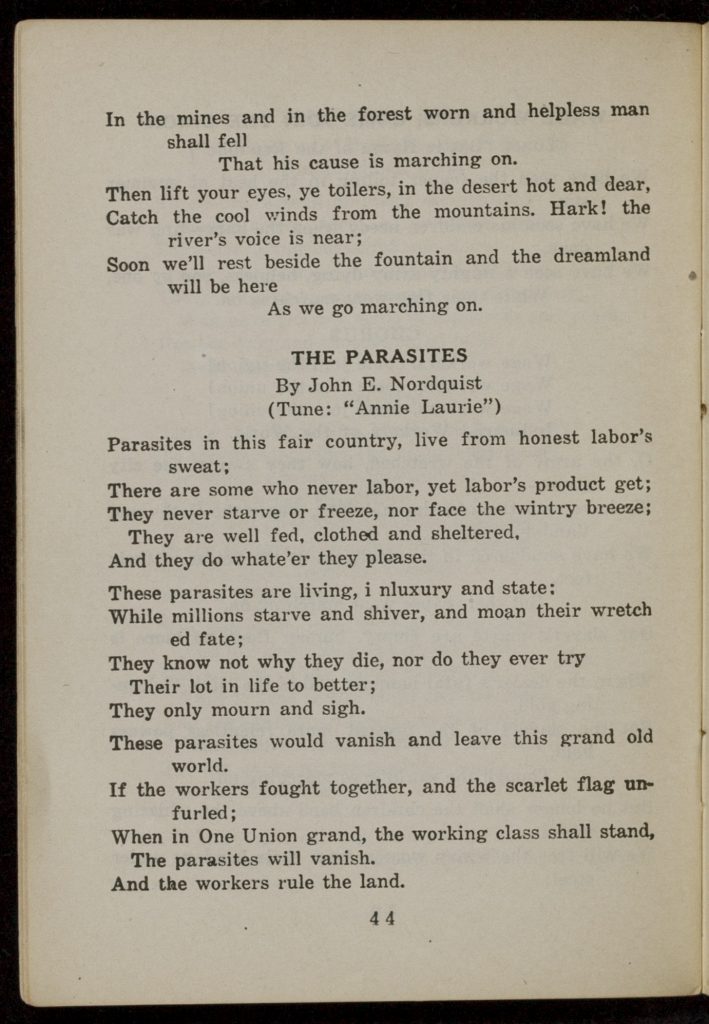

Selection: Excerpts from the 1919 IWW Song Book

Guiding Questions:

- How would you summarize the main message of the IWW Preamble in one or two sentences?

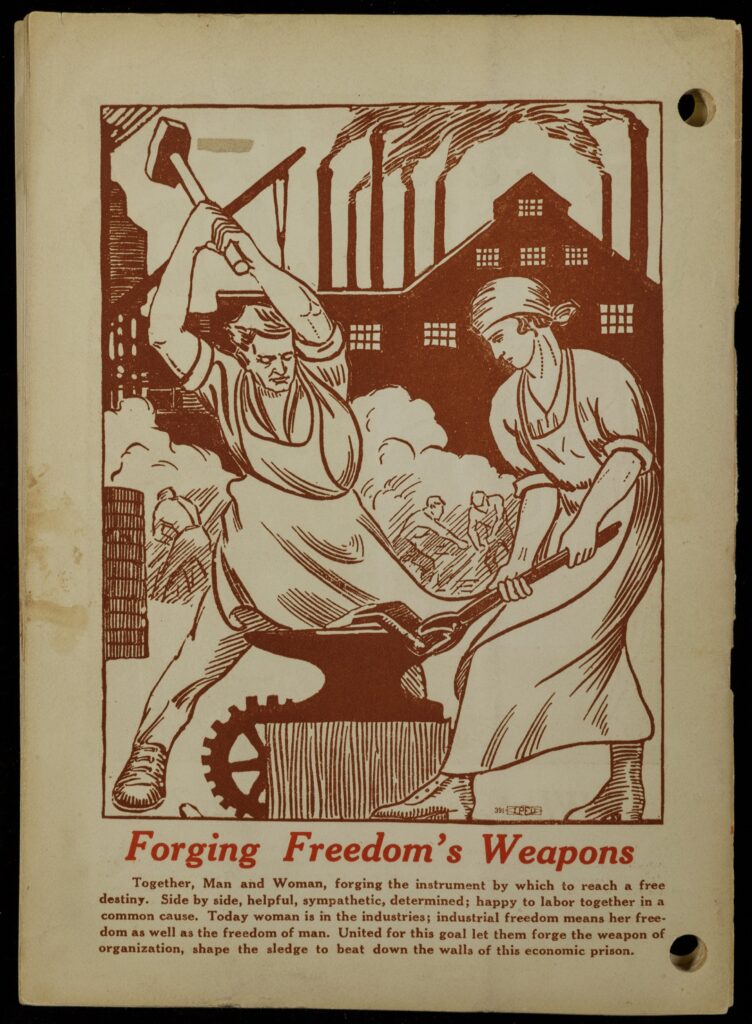

- How does “Forging Freedom’s Weapons” depict the relationship between men and women workers? How would you describe the illustration style? What visual features stand out to you?

- Who is the intended audience of “Forging Freedom’s Weapons,” in terms of gender, race, and occupation? Who is invited into or excluded from the illustration’s message? What is the main message of “Wage Workers, Come Join the Union”? What is the main message of “The Parasites”? How are the two messages similar or different?

- How are the key protest messages of the IWW communicated differently in writing, in illustration, and in song? How does the source medium change the impact of the message? How might the different forms reach different audiences ?

Protest or Riots in the 1960s?

The 1960s—and the year 1968 in particular—carry infamous associations with conflicts labeled as protests or riots. From World War I through the decades after World War II, millions of African Americans moved from the South to Northern cities like Chicago to seek new jobs and opportunities. From the beginning, Black Americans faced discrimination in employment, housing, and education. The descendants of European immigrants living in cities like Chicago increasingly viewed themselves as “white” precisely to distinguish themselves as different and superior to their new Black neighbors. White Chicagoans forcefully prevented African Americans from living in their neighborhoods, resulting in dense Black neighborhoods like the Black Belt on Chicago’s South Side. To make matters worse, factory owners and industrialists often hired Black workers to replace striking workers, making them “scabs” in the eyes of white workers. Many unions refused to admit Black workers. Meanwhile, the city kept most Black students in crowded, underfunded schools.

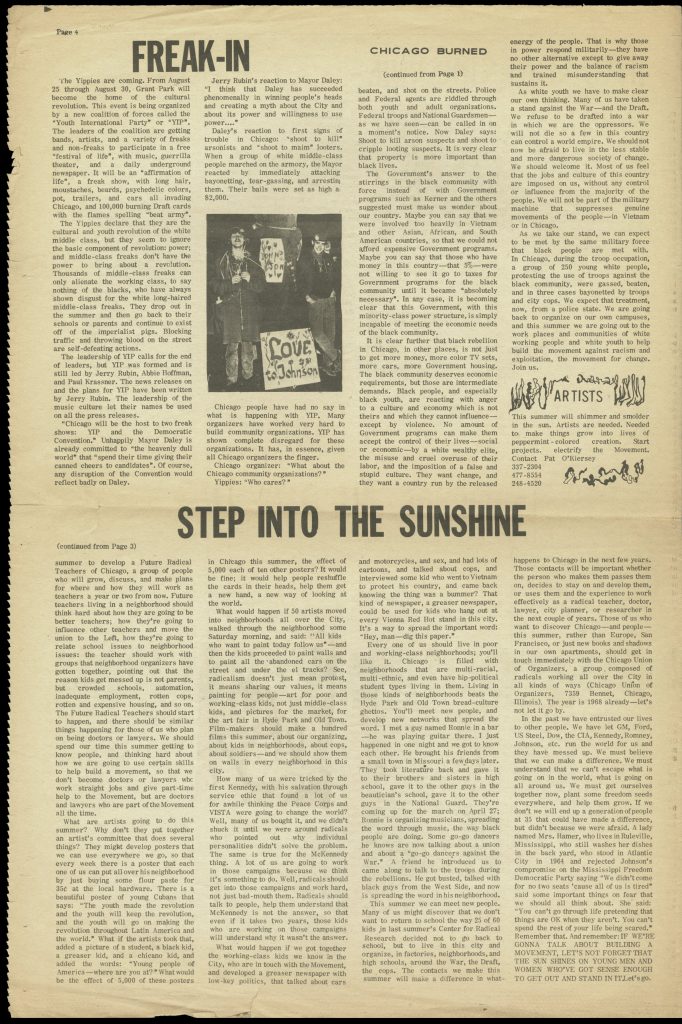

Selection: Students for a Democratic Society, “Chicago Burned” (1968)

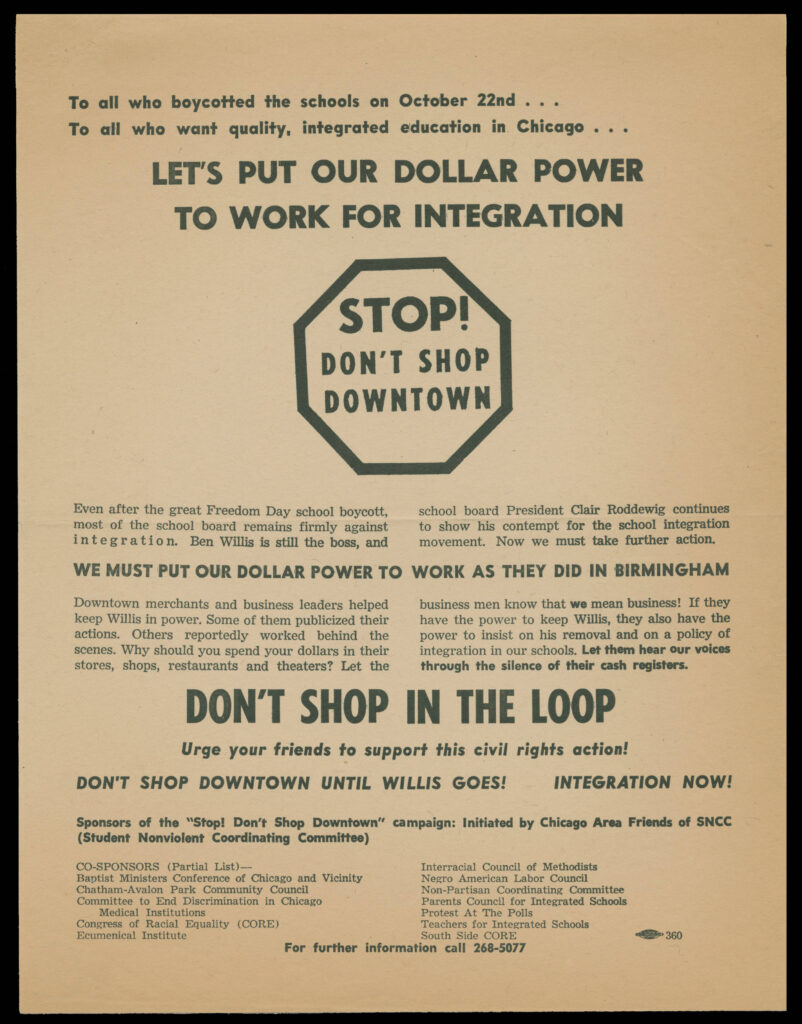

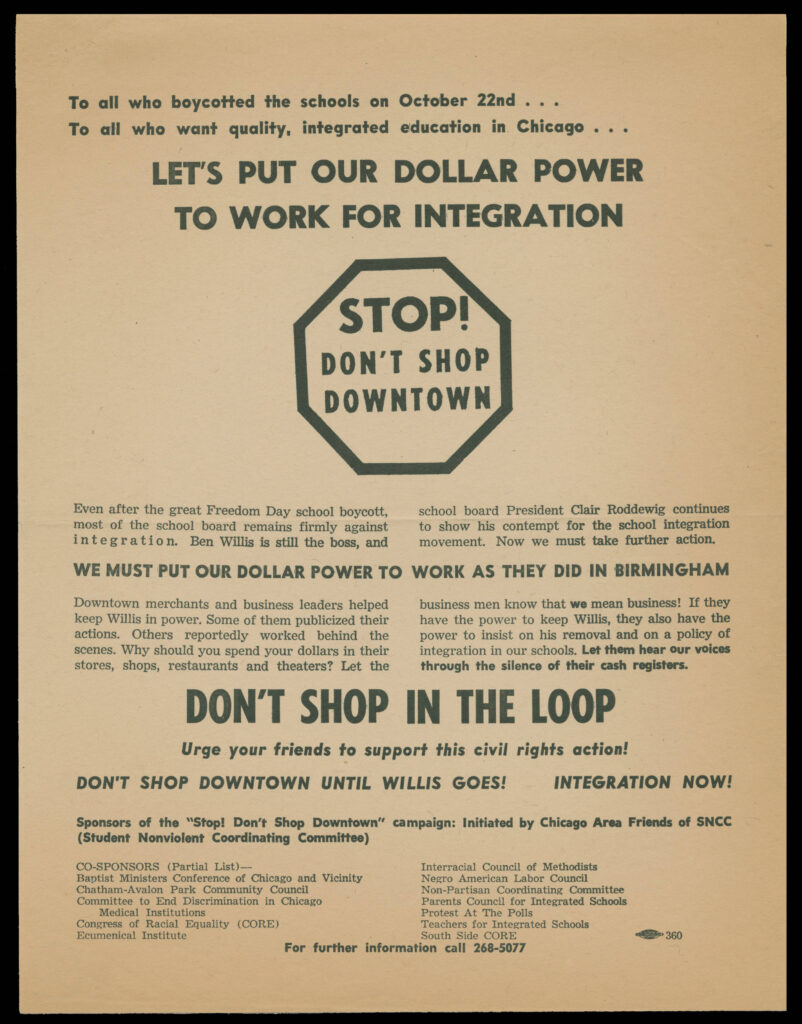

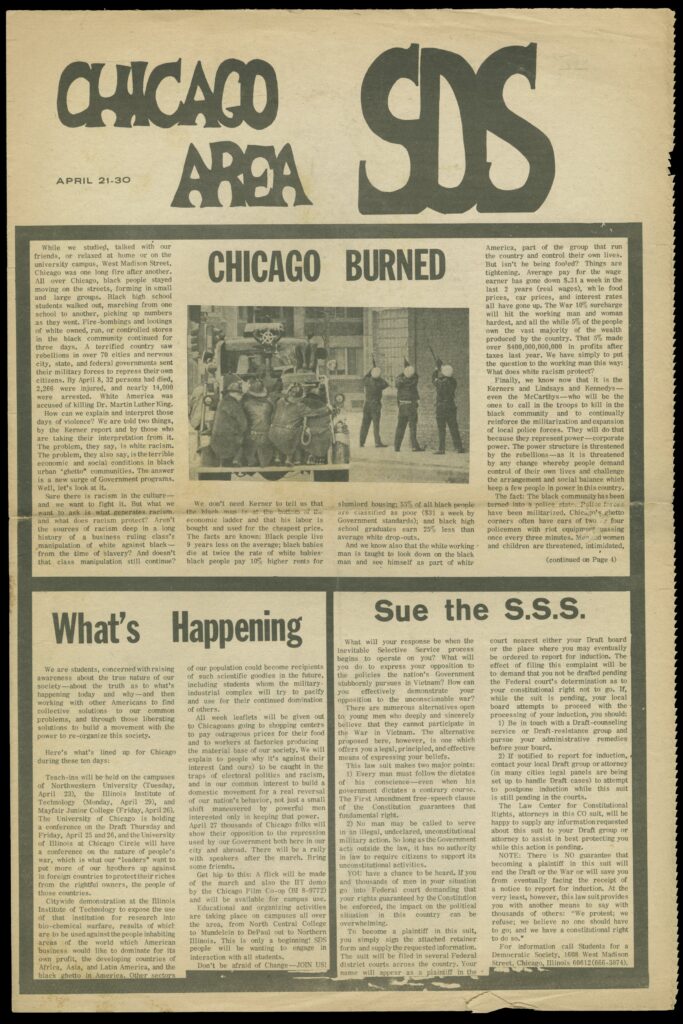

Black Chicagoans fought against pervasive discrimination throughout the twentieth century, launching protests for better education, jobs, and housing. For example, in October 1963, Black parents, students, and teachers boycotted Chicago Public Schools to protest segregation and unequal funding of the city’s schools. White Chicagoans stubbornly resisted educational integration, however, as well as equal housing and job opportunities. Frustration with ongoing racism, poverty, and limited gains after years of nonviolent protest erupted in Chicago and other cities after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968. Chicago’s city leaders called these uprisings “riots,” and dispatched police and the National Guard to violently subdue unrest in Black neighborhoods.

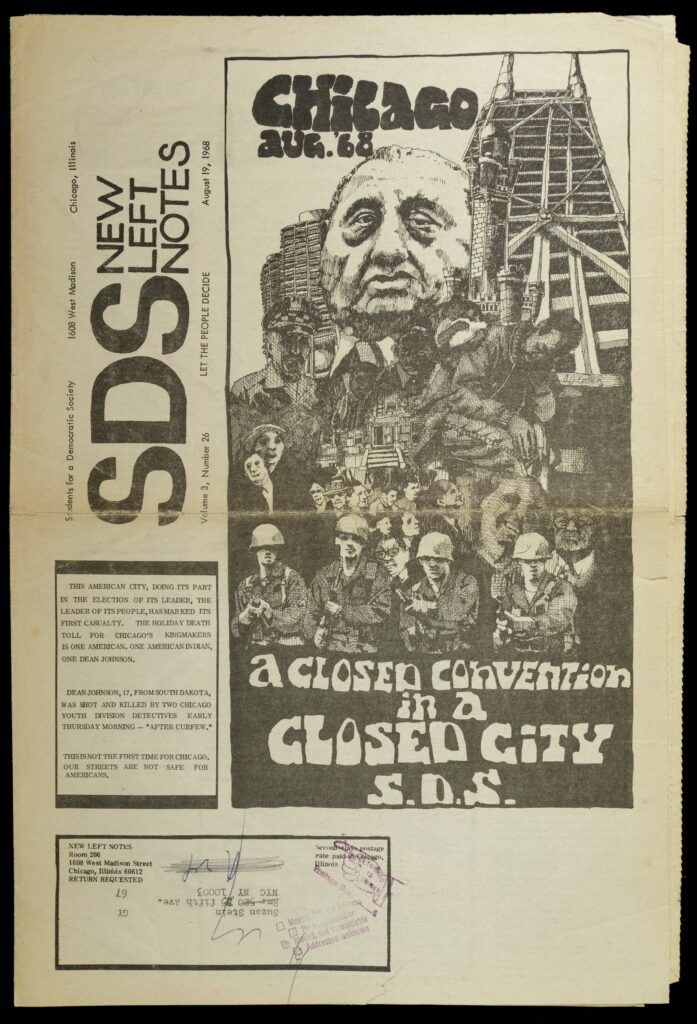

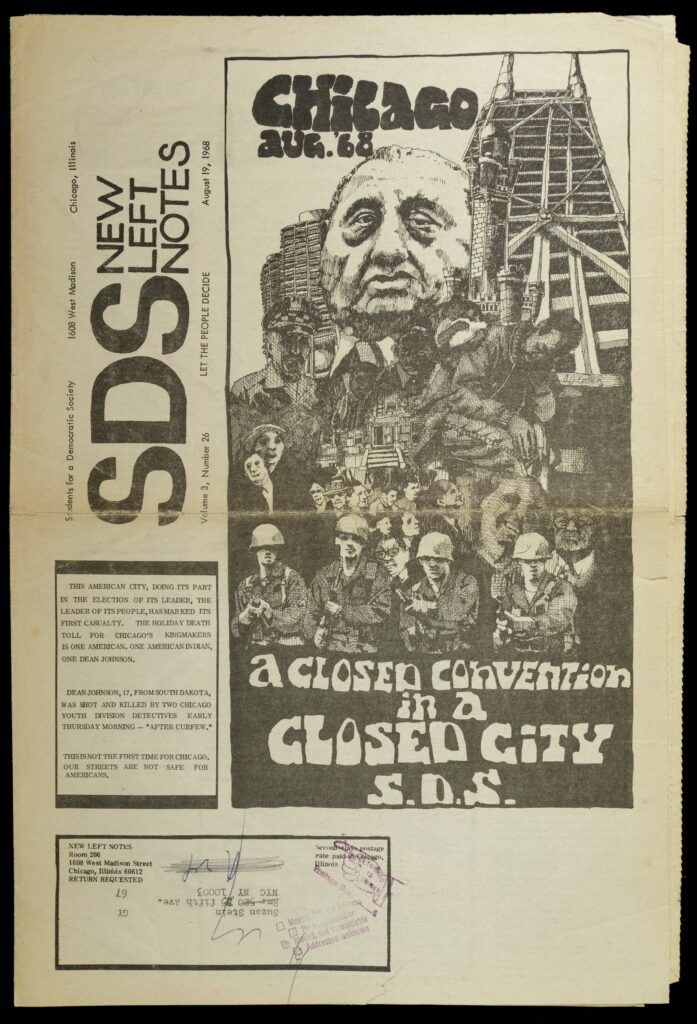

Later that summer, Chicago became the site of another violent, high-profile conflict between protesters and local police. The city hosted the Democratic National Convention, which drew many student protesters, anti-war groups, and civil rights organizations. Every night of the convention, Chicago police enforced an 11pm curfew, sometimes brutally clearing crowds in the city’s parks. On the third night of the convention, TV cameras captured police using tear gas and clubs on protesters in Grant Park and in front of the Hilton Hotel on Michigan Avenue. The police response shocked many TV viewers, but in many ways reflected an ongoing legacy of police brutality that had previously been deployed against industrial workers and Black Chicagoans.

Guiding Questions:

- According to the 1963 flyer, what is the purpose of the “Stop! Don’t Shop Downtown!” campaign? How does it try to expand or continue the Freedom Day school boycott? Why might this be an effective protest tactic?

- In “Chicago Burned,” how does the Chicago Area Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) describe the unrest in Chicago after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination? According to the source, what is the cause of the unrest? What is the solution to the causes of unrest?

- Who are the key players depicted in “A Closed Convention in a Closed City,” and how does the illustration convey their roles in the conflict? What visual elements of the image stand out to you? How would you describe the visual style of the illustration? How does the visual style support the illustration’s main message(s)?

- The Newberry Library collections do not hold other sources on the April 1968 “riots,” including any sources created by Black Chicagoans. What could we learn from sources from the Black community that cannot be learned from an article by a predominantly white organization like SDS? How does the lack of sources by or about Black Chicagoans in 1968 shape what we can and cannot learn from the Newberry’s collections about protest in Chicago?

Chicago Indian Village

Indigenous people have lived in Chicago beginning long before European settlement and continuing through the present day. Chicago resides on the homelands of the Odawa, Ojibwe, and Potawatomi Nations, as well as the Peoria and Kaskaskia Nations. Other nations have also lived in the region, including the Myaamia, Wea, Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Thakiwaki, Meskwaki, Kiikaapoi, and Mascouten peoples. Through a series of treaties from 1795 to 1833, the United States forcefully displaced Indigenous people from the Chicago area. Throughout the nineteenth century, the United States aggressively pursued the violent removal of Indigenous people from their lands across North America, often engaging in outright warfare and genocide. By the early twentieth century, many surviving Indigenous nations occupied reservations that represented a fraction of their land, often in regions far removed from their home. The United States government attempted to shrink reservations over time, repressed cultural traditions, and supported a damaging boarding school program for Indigenous children. As a result of US policies, many Indigenous people on reservations faced severe poverty throughout the twentieth century.

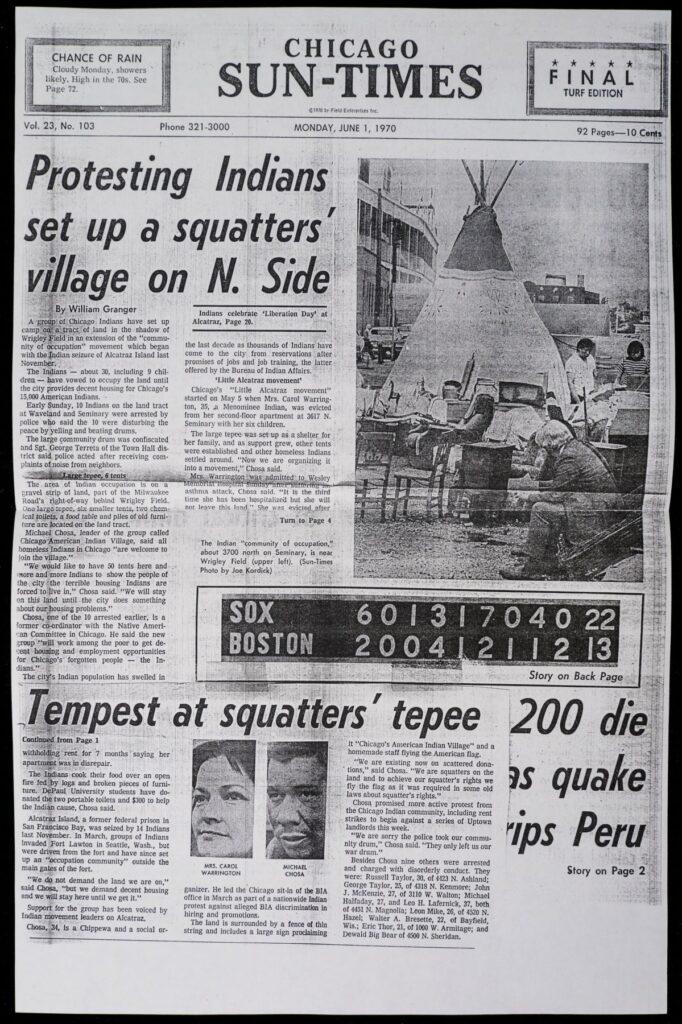

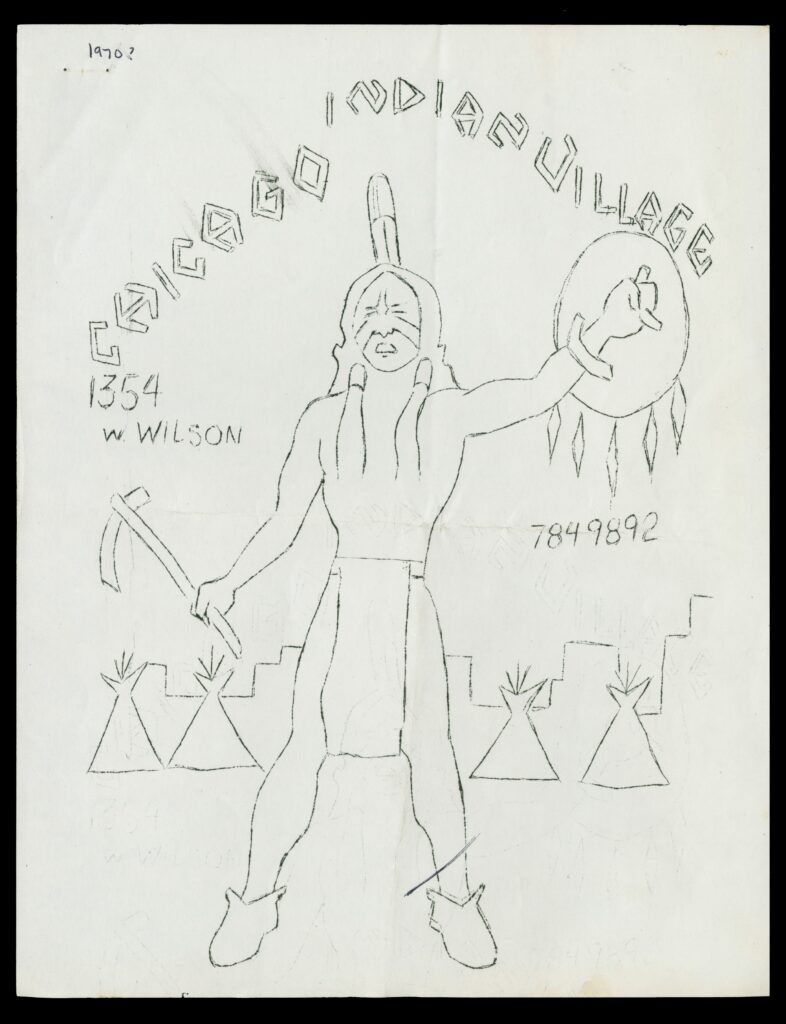

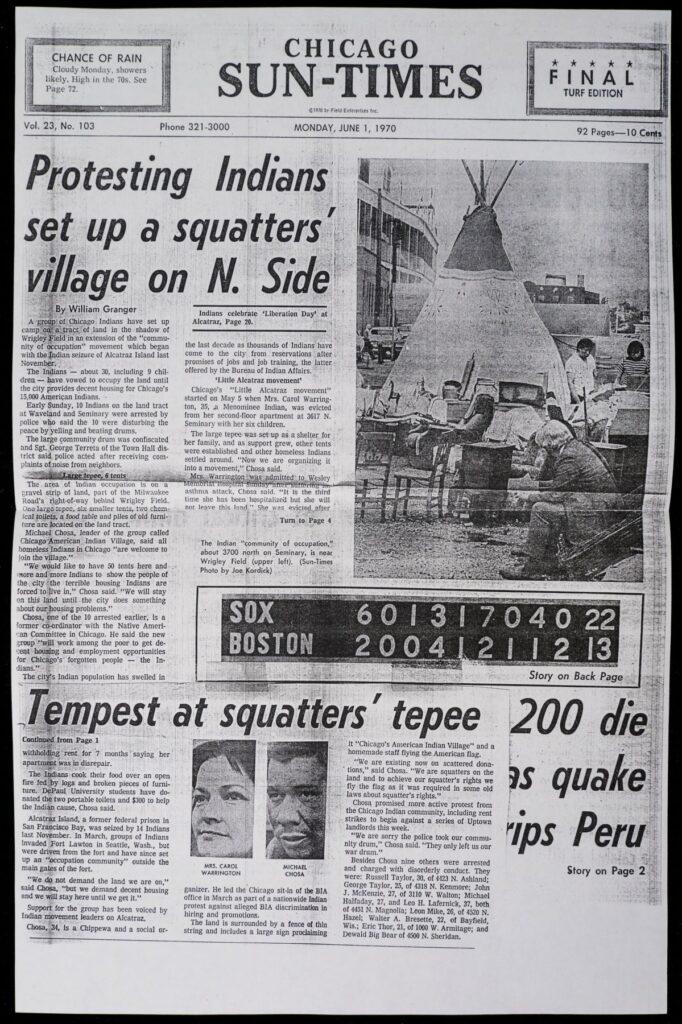

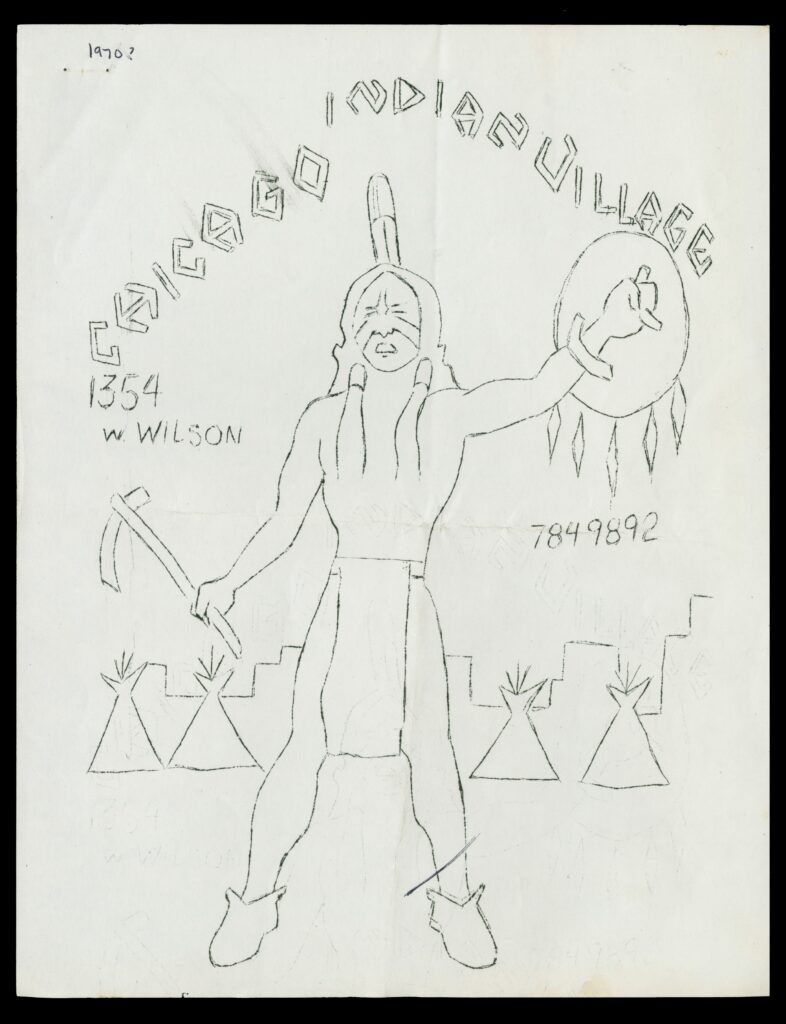

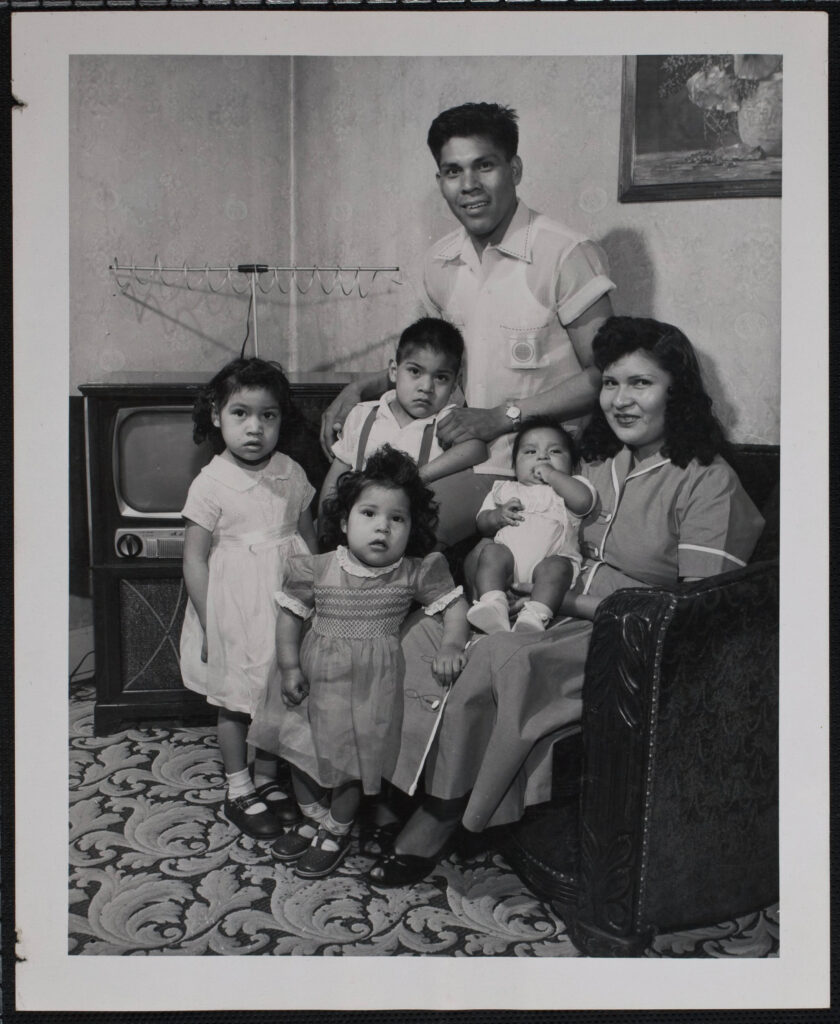

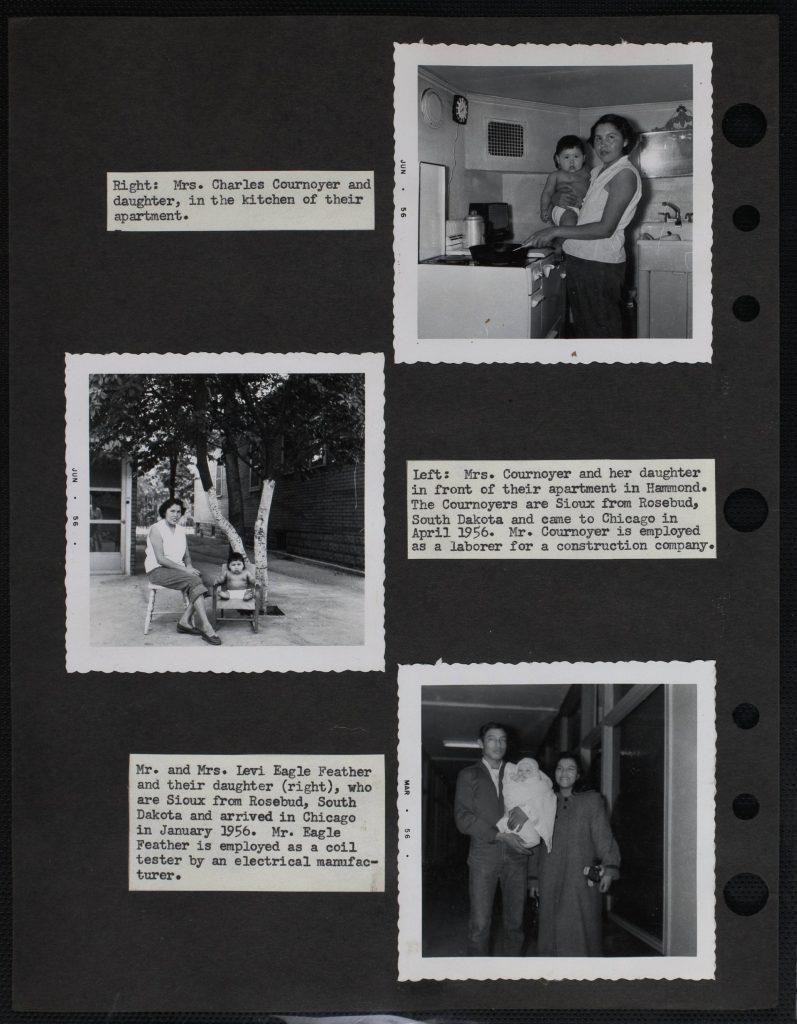

In the 1950s, the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs began a new program that encouraged thousands of American Indians to relocate from reservations to cities like Chicago, promising housing, job training, and educational assistance. As a result, Indigenous people from different nations across the country moved to Chicago for economic opportunities and formed community organizations like the American Indian Center. For many relocated American Indians, however, the Bureau’s promise of good housing, jobs, and education remained unfulfilled in the following years. When Carol Warrington’s landlord evicted her from her home in 1970, she set up a teepee in front of nearby Wrigley Field to protest her plight. Fellow local American Indians joined her, resulting in the creation of the Chicago Indian Village, an Indigenous activist group that protested the lack of resources and housing that American Indians faced in Chicago. In the following two years, the Chicago Indian Village went on to occupy other areas in Chicago to protest for better housing and social services. In some ways, Indigenous activism in Chicago resembled the ongoing activism among other marginalized groups, like Black Chicagoans, who also faced poor housing, inadequate social services, and discrimination. However, the protests of the Chicago Indian Village also reflected the distinct identities and histories of Indigenous people in the United States who survived decades of federal policies of displacement, genocide, and relocation.

Selection: Bureau of Indian Affairs Relocation Materials (c. 1955)

Guiding Questions:

- According to the promotional images by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, what are the markers of an Indigenous family that successfully relocated to Chicago? What do their lives look like?

- According to the Chicago Sun-Times, what is the purpose of the Chicago Indian Village encampment at Wrigley Field? Who are the spokespeople for the group?

- How does the newsletter cover convey elements of both Indigenous culture and urban life? Which is more prominent in the image? How does the image compare or contrast with the images of urban Indigenous people in the Bureau of Indian Affairs promotional images?

Remembering Protest in the Twenty-First Century

How is protest remembered? Some protest actions are well-documented by primary sources collected by institutions like the Newberry Library. Other conflicts do not result in archival evidence, as with the lack of materials in the Newberry related to the Chicago uprisings in April 1968. How should evidence from protests be collected? One response to this question is the Newberry Library’s Chicago Protest Collection, which actively collects public submissions of digital and physical materials that document current-day protests, counter-protests, and demonstrations. The archive contains images and signs from recent movements such as Women’s Marches, Inauguration Day Marches, and Immigration Ban Protests in 2017, as well as Black Lives Matter protests from 2015 to the present. Not all protests in Chicago from recent years are documented, and not all events result in equivalent amount of materials donated to the collection. Why are some events documented in the collection more than others? How do preserved images and physical material from past protests shape our collective memory of the event? How do primary sources impact whether we label conflicts as protests or riots? Does it matter who creates or donates the primary sources? Asking these questions of primary source documents and archival collections helps us better understand how we know what we think we know about the past. Importantly, it also reveals the limitations of physical records as sole evidence of historical events. How do we remember Chicago’s past protests beyond archival collections? And, most importantly, how do we use memories of historical conflict to inform actions today?

Guiding Questions:

- What are the similarities between the Black Lives Matter photograph and the Women’s March photograph? How do you know that the photographs document protests? How do photographs like these shape our understanding of what “protest” looks like?

- What are the differences between the Black Lives Matter photograph and the Women’s March photograph ? Consider the image coloring, perspective, framing, and who and what is visible in the image. What are the impact of these differences for the viewer? How do the differences shape the images’ messages about the two marches?

About the Author

Rachel Boyle, PhD is a historian and co–founder of Omnia History, a public history collaborative dedicated to using the past to promote social change. Boyle partners and consults with cultural organizations across the Midwest and United States to build constituent relationships and conduct historical research. She also teaches and writes for public audiences, using scholarship to inform her public history work and vice versa. Boyle earned her PhD in U.S. and Public History from Loyola University Chicago and currently teaches at DePaul University.

Further Reading

Bloom, Alexander and Wini Breines. “Takin’ it to the Streets”: A Sixties Reader. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Coates, Ta-Nahisi. “The Case for Reparations.” The Atlantic (June 2014).

Grossman, James R. Land of Hope: Chicago, Black Southerners, and the Great Migration. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989.

Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Montgomery, David. The Fall of the House of Labor: The Workplace, the State, and American Labor Activism, 1865-1925. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

Muhammad, Khalil Gibran. The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010.

Ralph, James R., Jr., Northern Protest: Martin Luther King, Jr., Chicago, and the Civil Rights Movement. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993.