Introduction

In the twenty-first century, William Shakespeare remains the best-known English writer in the world. His work has been translated into over 100 languages and his plays appear on the stage and as movies and television shows. He remains a fixture in popular culture as well, and is his work is even referenced in the musical Hamilton.

It is a bit surprising, however, that Shakespeare became popular in America at all. Seventeenth-century Puritans and Quakers morally opposed the theater and authorized severe punishment for stage plays, which were placed in the same category as playing dice and bear-baiting. While Shakespeare’s plays were performed in America beginning in the 1730s, the Continental Congress placed a ban on theater during the Revolutionary War. This ban essentially created an embargo on British culture just as it had on British goods. By the late 1780s, anti-theatrical laws began to be repealed. Debates over repealing these laws focused on whether the stage could be politically beneficial to the new nation. Could theater be used to shape American values? Additionally, there were questions over whether theater, as an entertainment, had ever proven harmful. By 1794, new playhouses were built in Boston and Philadelphia. The first American-printed edition of Shakespeare was published in Philadelphia by Bioren and Madan in 1795.

By the early nineteenth century, Americans had begun to read, publish, perform, watch, and think about Shakespeare in new ways, and to “adopt” him as one of their own. The author James Fenimore Cooper even declared in his 1828 book Notions of The Americans: “Shakespeare is the great author of America” (1828 Philadelphia: Carey, Lea & Carey edition, 148-49). Part of what appealed to Americans in the post-Revolutionary period was that several of Shakespeare’s plays focused on kings who had come to power through criminal deeds (Richard III, Hamlet) or who had gone crazy (King Lear), offering proof that the monarchy against which they had just rebelled was indeed corrupt. Additionally, Shakespeare’s characters were not just kings and queens, but came from all walks of life. Residents of the new nation could see themselves in his work, even though it was two hundred years old. And finally, in the nineteenth century, people became interested in Shakespeare’s own life. They (incorrectly) described him as a man with almost no formal education who became the most important writer in the English language. To Americans, this meant that he was a self-made man who had pulled himself up by his bootstraps and become successful through his own hard work and determination. Ultimately, the Shakespeare that nineteenth-century Americans “created” was vastly different than the Shakespeare that we know today or that Shakespeare’s own audiences would have known.

Performances of Shakespeare did not look the way that we know them today. One play or even just a scene or two would form only one small part of an evening’s entertainment, which might also include music and dancing, animal acts, or even another play. Even when a full Shakespeare play was performed, the actors did not perform the same play night after night for weeks on end. Instead, they performed a different play every night to lure back theatergoers. Actors also used new methods of transportation – most specifically the railroad – to travel the country, performing to small towns throughout the interior of the United States and even to gold miners in San Francisco. After the invention of photography later in the nineteenth century, cabinet cards that featured photographs of actors in their most famous roles became hugely popular, linking Shakespeare to the rise of celebrity as we know it.

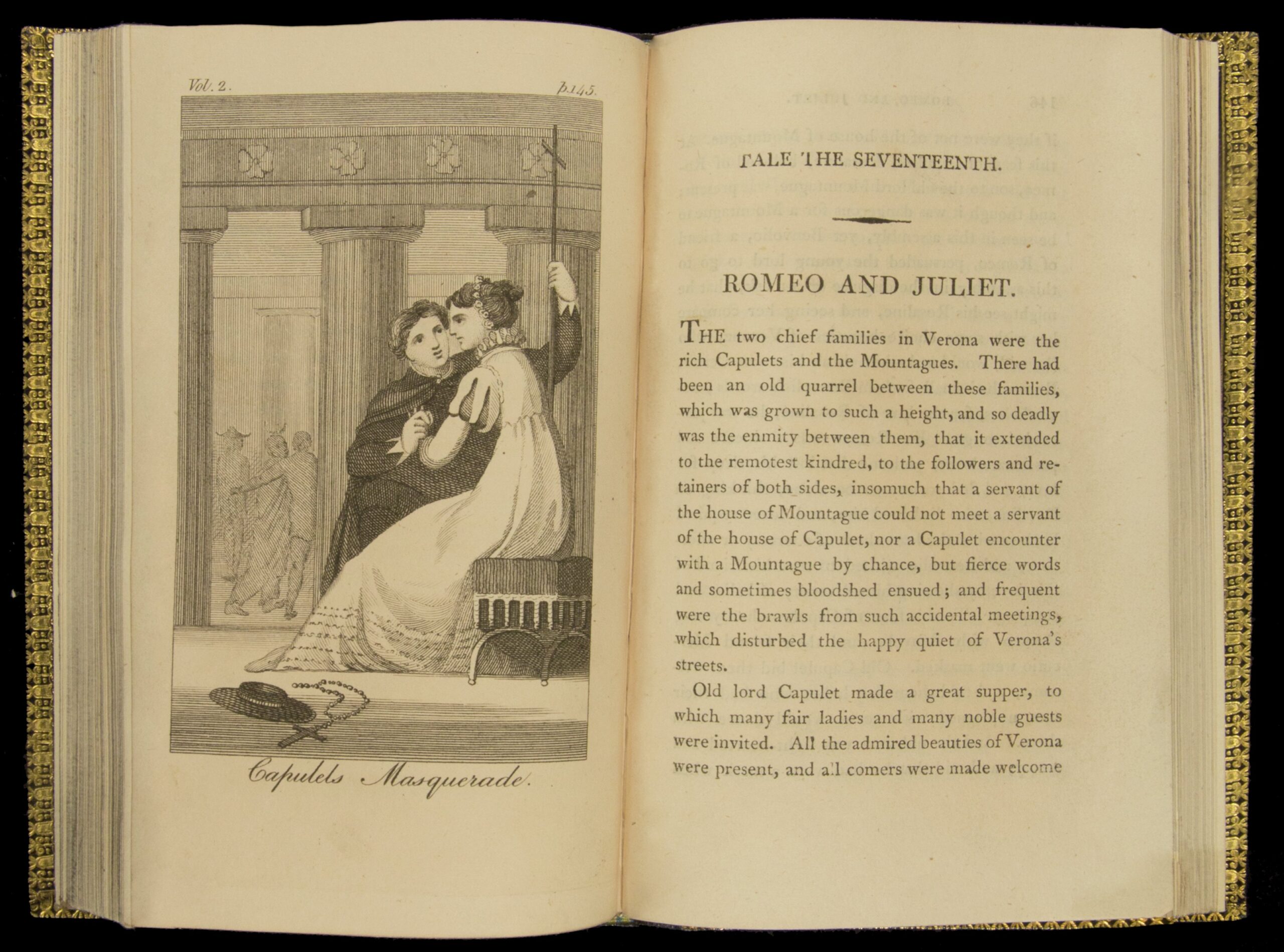

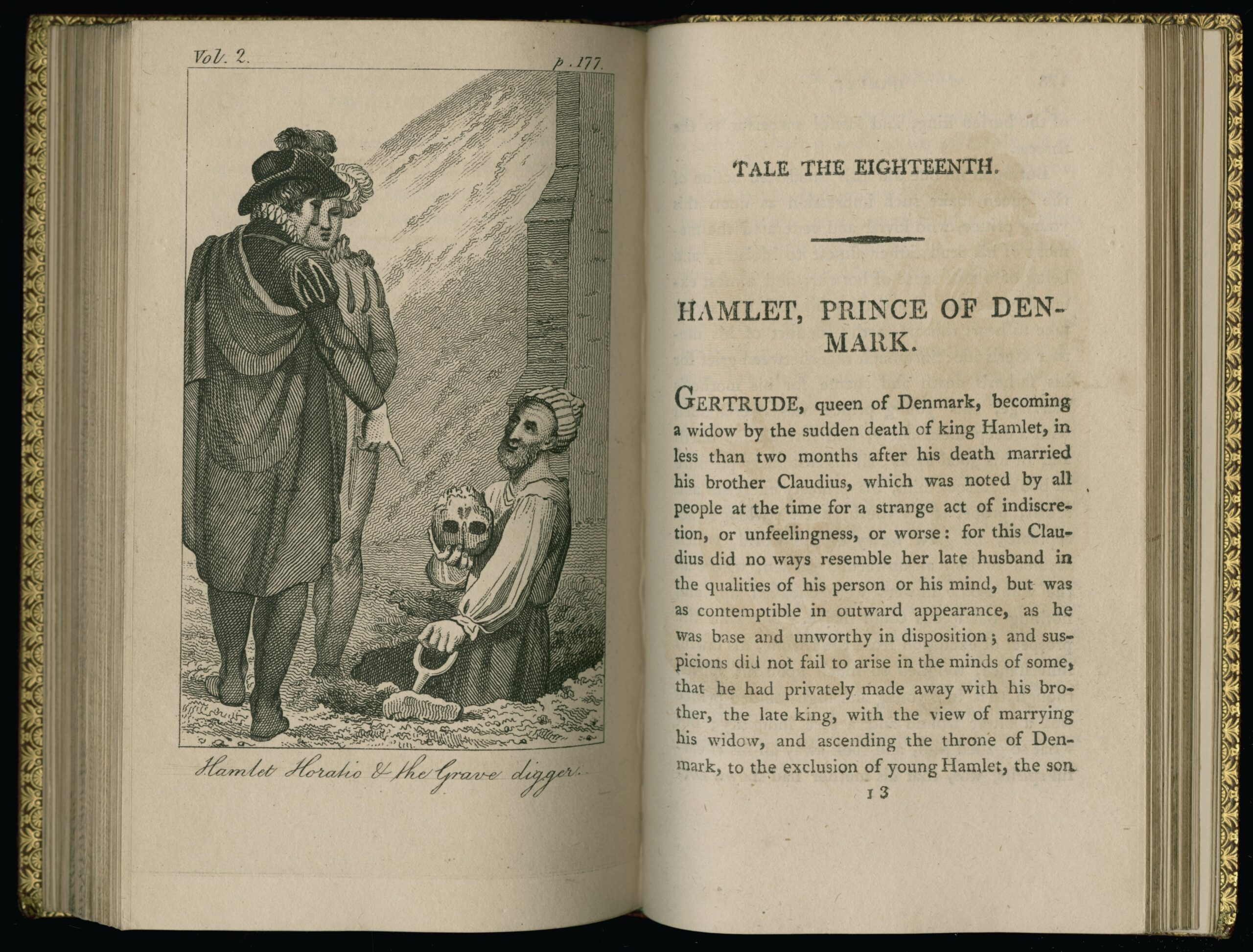

The American masses encountered Shakespeare through inexpensive books and periodicals, which were made possible by new printing technologies. Previously, it was expensive and time-consuming to produce books, but the invention of faster, mechanized printing presses meant that thousands of books could be printed cheaply in a short period of time. Affordable books and rising literacy rates meant that more people were buying and reading more books than ever before. Given that Shakespeare was already a household name, publishers looked for ways in which they could further commodify him. Beginning in the late eighteenth century, there was a proliferation of books marketed specifically to children. Shakespeare was adapted into short stories with illustrations that were designed to appeal to them (and to their parents), and these books were republished throughout the nineteenth century. Periodicals, which were popular with all kinds of readers, also often featured Shakespeare. Other books excerpted his work or described theatrical performances in great detail.

Shakespeare is a useful historical lens with which to view a rapidly changing America. In the early decades of the new nation Shakespeare was both a tool for shaping national identity and a product of this new identity. By the mid-nineteenth century, men, women, and children of all social classes knew and loved Shakespeare. Yet by the beginning of the twentieth century, another shift occurred, in part parallel to the rise of English literature as a scholarly discipline. Instead of being marketed to the masses as entertainment, his work was perceived as educational and a sign of high culture. It was taught in schools and intended only for those who were allegedly “refined.”

Questions to Consider:

- How is the Shakespeare represented in the nineteenth century different from the Shakespeare we know today? What are some similarities between them, as well?

- What cultural and technological changes occurred that helped to increase Shakespeare’s popularity in America?

Shakespeare on the Page

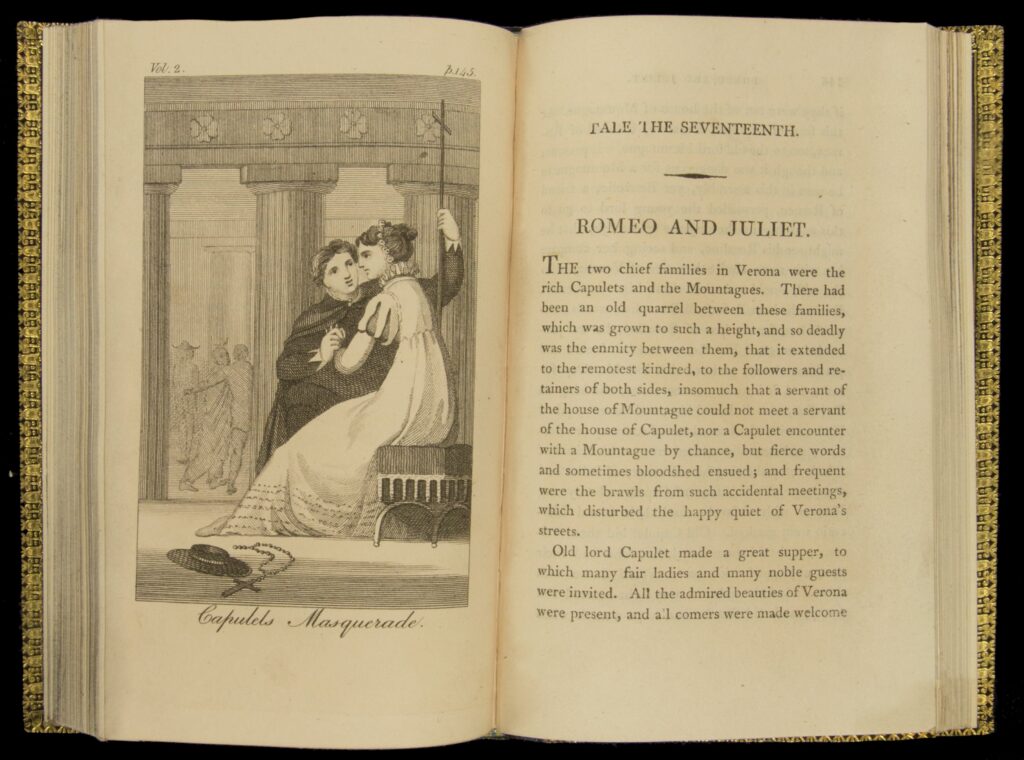

In the nineteenth century, Americans read Shakespeare constantly, but in different ways than previous generations. At the beginning of the century, the general public rarely his read plays in their entirety, but instead read adaptions and alterations of his work in new types of publications. Editions of Shakespeare designed specifically for children and families to read together became popular as changes in educational and childrearing practices opened up a new market for book publishers. Such books usually had a strong moral component. Charles and Mary Lamb’s Tales from Shakespear: Designed for the Use of Young Persons turned twenty of Shakespeare’s plays into short prose stories, using simple language paired with engraved illustrations that give the work a fairy tale quality. During the same time period, Thomas and Henrietta Bowdler published The Family Shakespeare, which removed any material deemed too inappropriate for young or female audiences. About 10% of Shakespeare’s original text was cut: exhortations using the word “God” were cut or changed to something gentler; bawdy characters were taken out; and Ophelia’s suicide in Hamlet was changed to an accidental drowning. While the Bowdlers liked Shakespeare, and simply wanted to make him more family friendly – much like the Lambs – their name became a shorthand for censorship: to “bowdlerize” a work is to censor it.

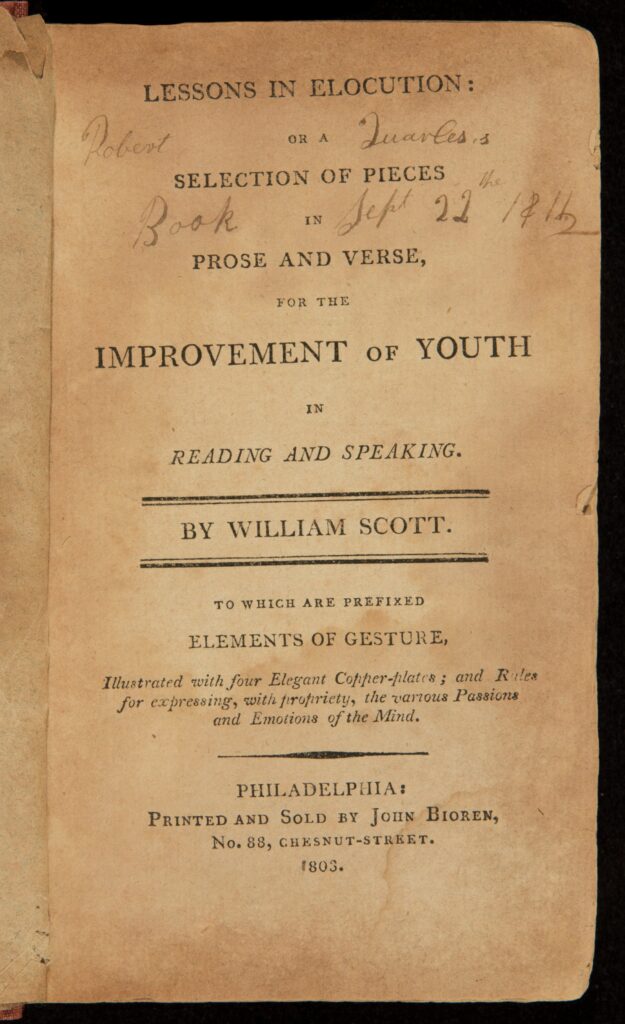

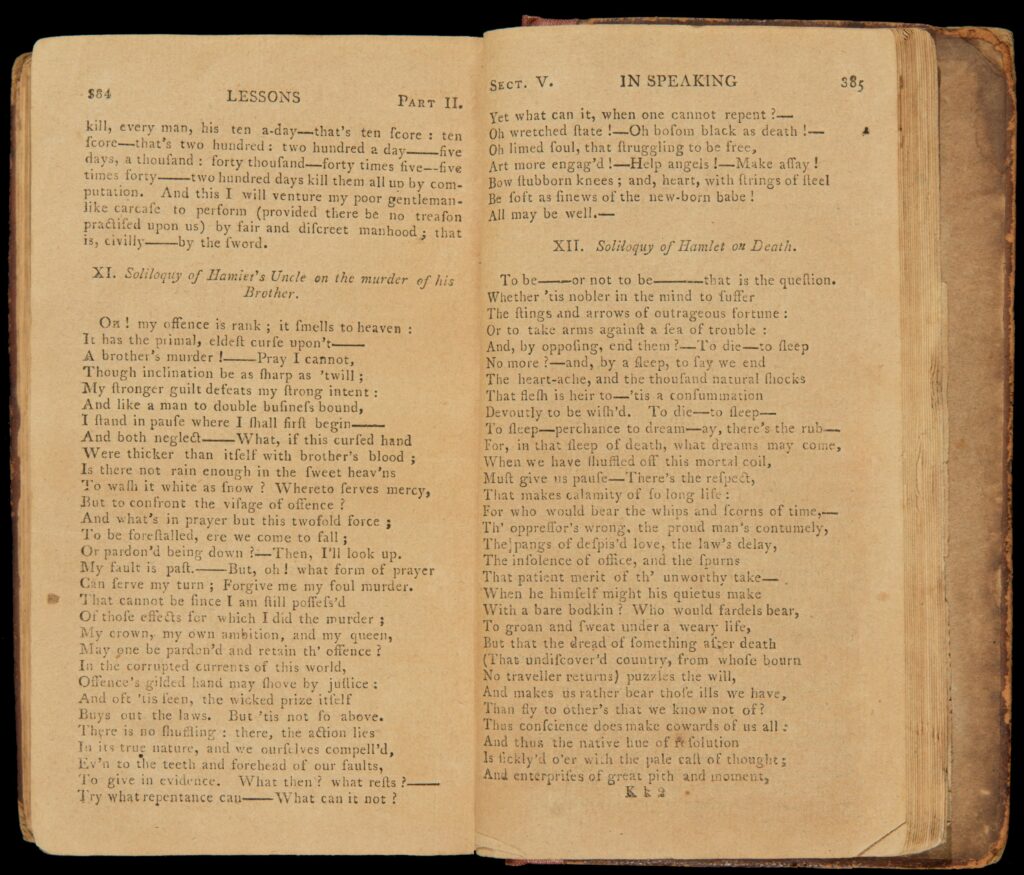

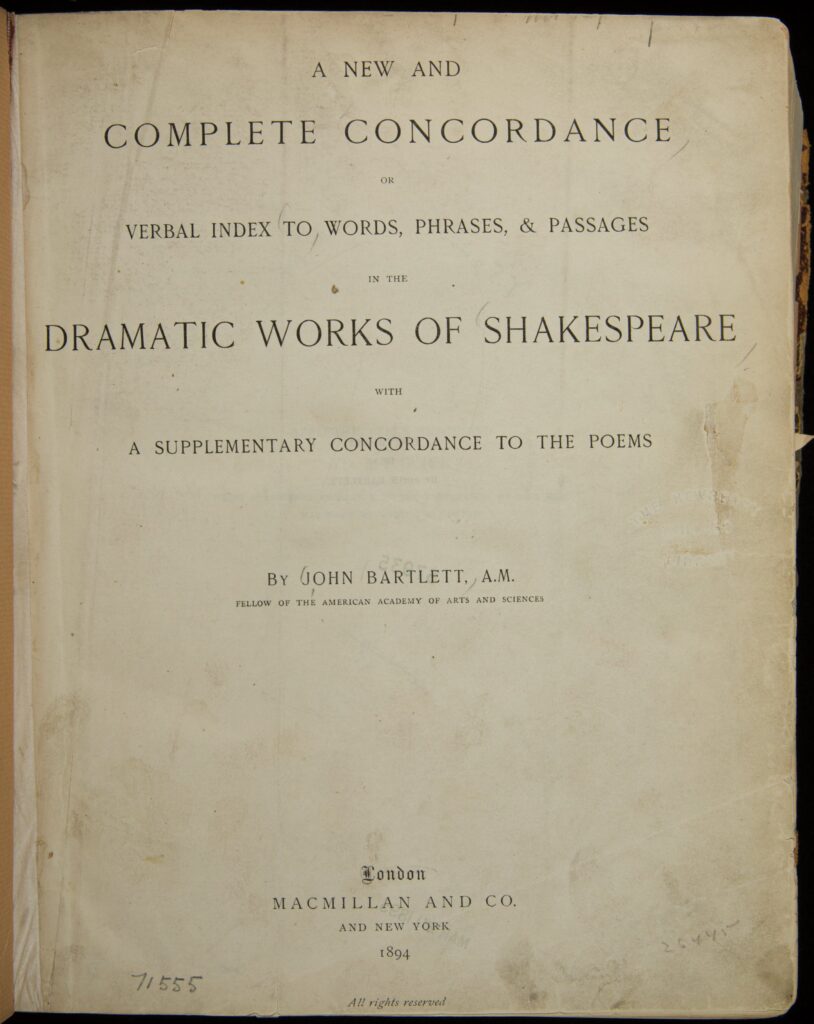

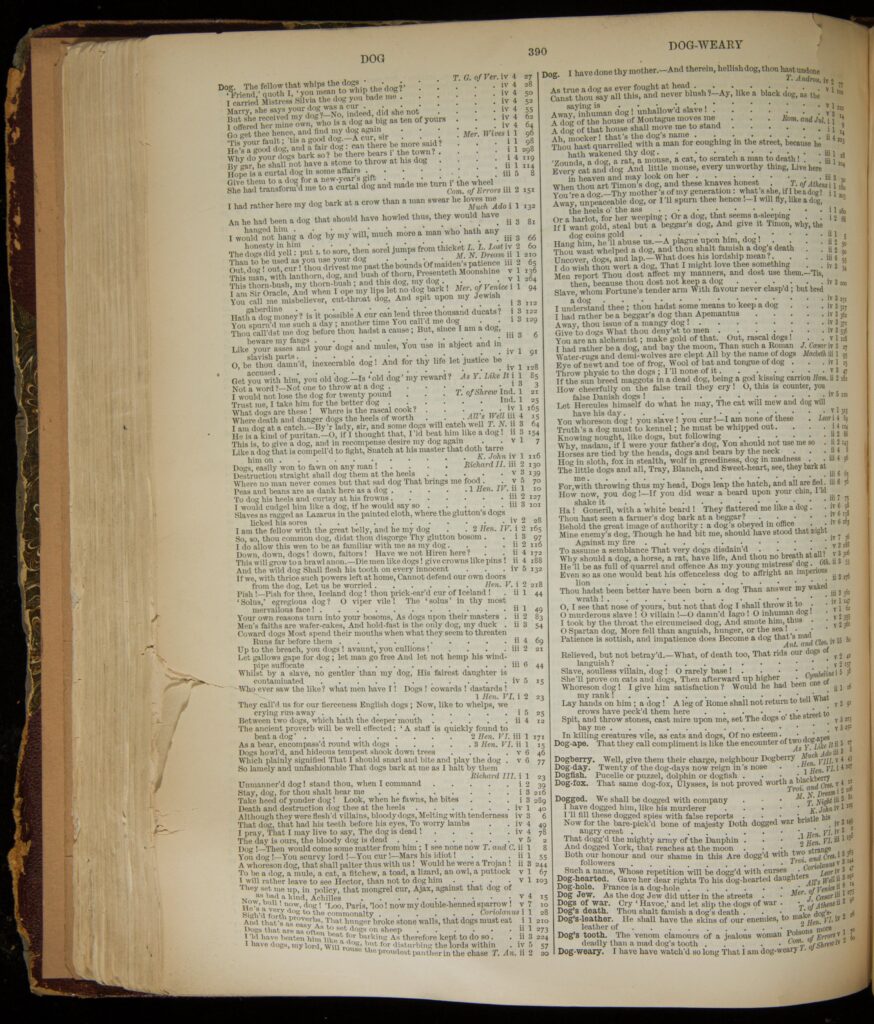

People also encountered Shakespeare through oratory, or public speaking. Oratory was an integral part of life in nineteenth-century America and like actors, orators traveled the country giving impassioned speeches to crowds. Young students might also have encountered Shakespeare in handbooks for public speaking. Such books often included monologues or speeches extracted from his plays. This practice “detached” the speeches from the plays (and Shakespeare himself). While many were familiar with, say, the “To be, or not to be” speech from Hamlet, they might not have recognized other speeches or scenes from the play, or even known its characters or plot. Abraham Lincoln largely learned his Shakespeare from these books; he even performed speeches from Hamlet and Macbeth while having his portrait painted in the White House. Oratory was not just about reading and memorizing passages but was about performing as well, and these handbooks also included instructions about gesture and other techniques for delivering effective speeches. Orators and writers were also interested in including Shakespeare in their own, original works and a common reference tool was a concordance – an index of every single word that occurs in Shakespeare’s plays and poems. Arranged alphabetically, like a dictionary, with references to each usage of a word, a concordance allows the reader to efficiently seek and retrieve each instance of whatever word is of interest – a bit like a Google search in print form. In making texts searchable, concordances inspired new practices of reading and composition. The only other work that had a concordance at this time period was the Bible. Josiah Bartlett, who began publishing his famous books of quotations mid-century, also produced a concordance to Shakespeare.

When nineteenth-century readers did read Shakespeare’s plays in their entirety, they weren’t satisfied with just reading the text. Instead, they wanted additional content like illustrations and notes about the plays, as well as illustrations of costumes, music, and more. These illustrated editions were inexpensive and worked to teach people history through Shakespeare. Nineteenth-century Americans found Elizabethan England fascinating and Shakespeare’s work – and the details of his own life – became part of this interest. It was this historical fascination that prompted publishers to add historical context and illustrations to printed editions of the plays.

Questions to Consider:

- In the Charles and Mary Lamb’s Tales from Shakespear, each play begins with an illustration of one of its scenes. Why do you think these particular illustrations were chosen? Do they help you recognize the play, and if so, how?

- When you read the opening lines of the stories in the Lamb’s book, do you immediately recognize them as Shakespeare’s plays? Why or why not?

Selection: Tales from Shakespeare by Charles and Mary Lamb, 1807

- On the title page of The Family Shakespeare, what evidence do you find of who the target audience was, and how the book was meant to be used?

- On the pages shown below from Lessons in Elocution, why do you think these particular speeches from Hamlet were chosen?

- In looking at the section below from Bartlett’s Index to Shakespeare, what can we learn about Shakespeare’s use of the word “dog”? How many plays did he use it in? What are the different ways in which he uses the word? Are they different from the ways in which we might use the word today?

- A free, online concordance to Shakespeare can be found here. A bit of searching reveals that Shakespeare used the words “dog” 143 times, “cat” 36 times, and “America” once (in Comedy of Errors). How do you think this kind of tool might both help and distort our thinking about Shakespeare?

Shakespeare on Stage

As with publishers, theaters made use of emerging technologies and pushed cultural boundaries to market Shakespeare – and the actors who performed his work – to new audiences, and in doing so, helped to cement Shakespeare’s position in popular culture. But also, as with print culture, these new technologies altered the public’s ideas about and perception of Shakespeare’s work. Additionally, theaters functioned as spaces where the public could engage with changing ideas of gender, race, and class in America; the ways in which Shakespeare’s plays were newly presented on stage contributed to these emerging cultural dialogues.

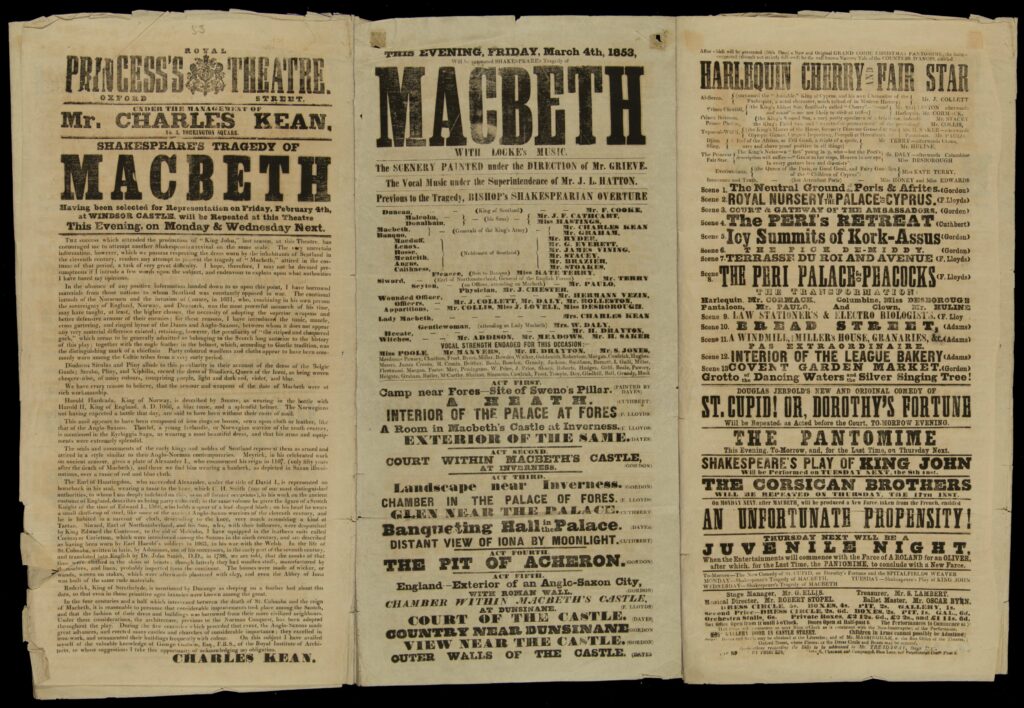

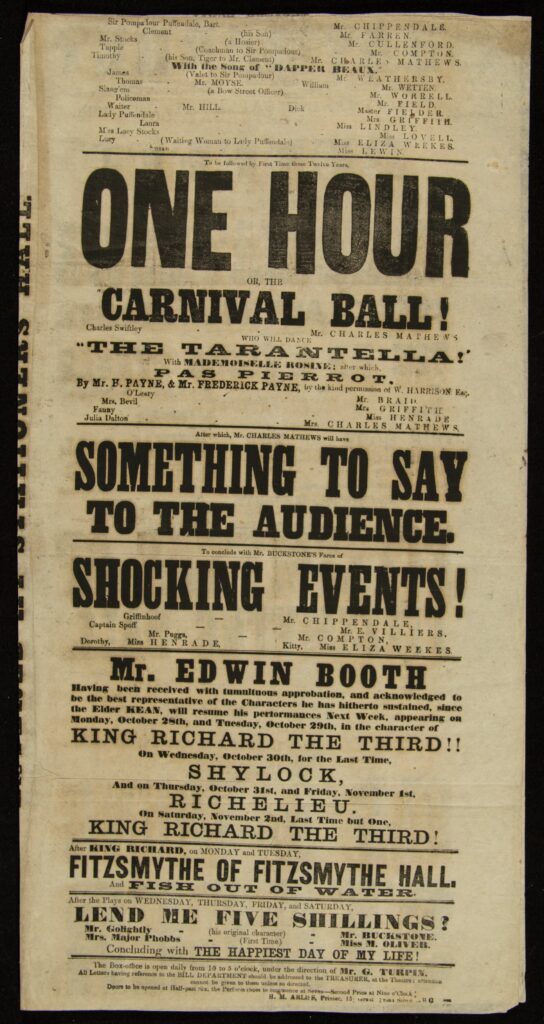

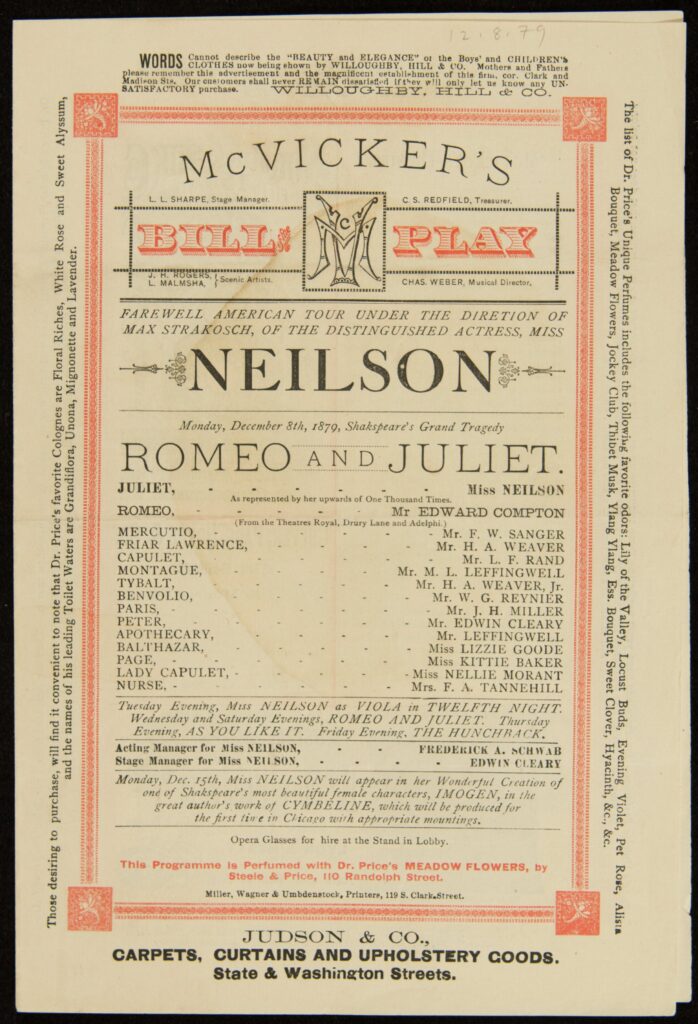

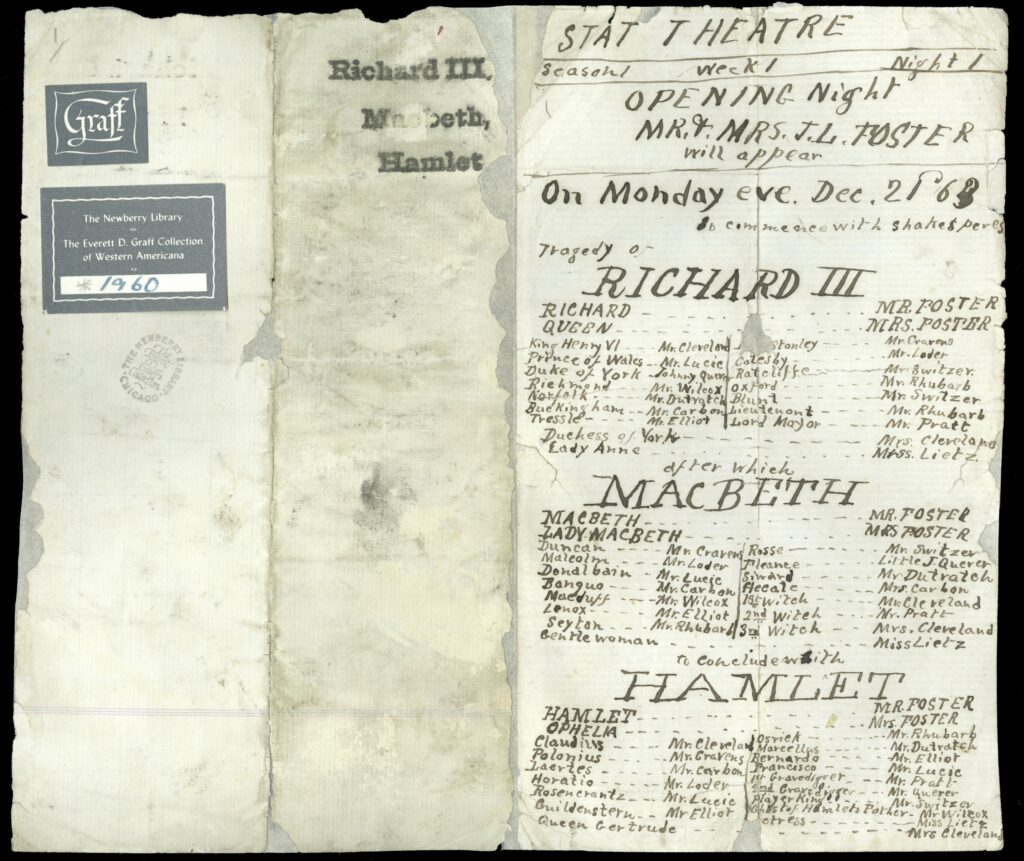

In the nineteenth century, theaters rarely featured a run of a single play. Instead, each night included a different combination of performances, interspersing plays, music, and dancing. This practice allowed actors and actresses to cycle through the plays in their repertoire and encouraged patrons to return many times to see their favorite actors in different roles. Theaters advertised performances with broadside playbills, which featured eye-catching type, and could be pasted up in various locations. Playbills provide a wealth of knowledge about theater in the period: they tell us what plays were performed and how often, who the actors were, and sometimes even what the scenery and costumes were like. All of these clues can help us piece together who a theater’s audience may have been and what – and who – they enjoyed seeing on the stage. A manuscript playbill created by a thirteen-year old boy in Ohio in 1863 for an imaginary evening of performance featuring his friends and family provides evidence of these advertisements’ popularity and impact. His handiwork is clearly modeled on his own familiarity with the theater and suggests that playbills played an important part in the theater-going experience.

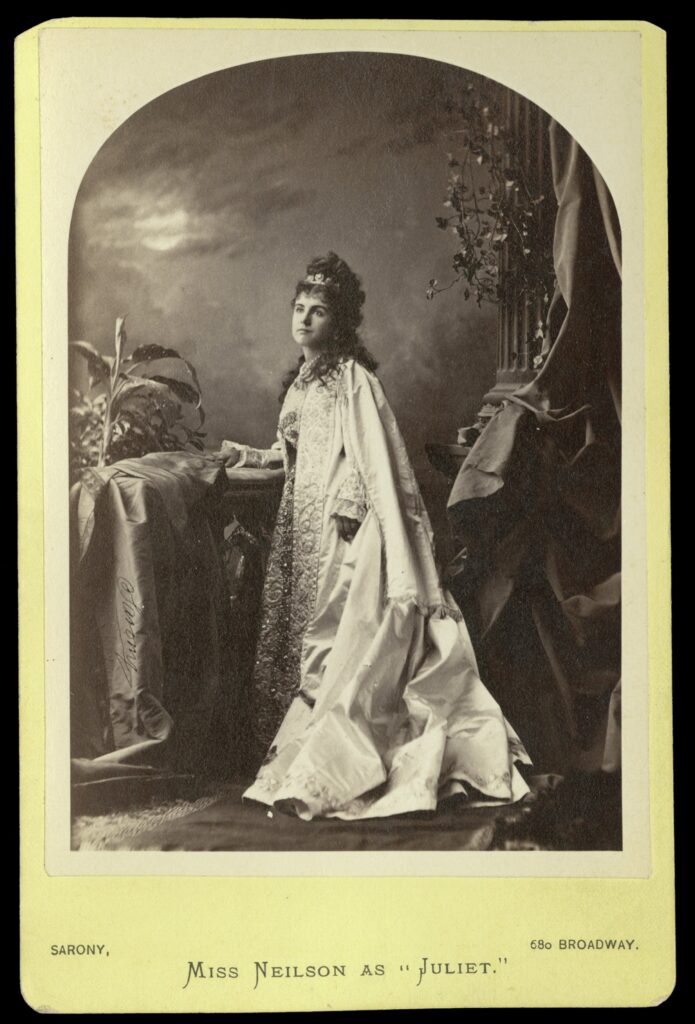

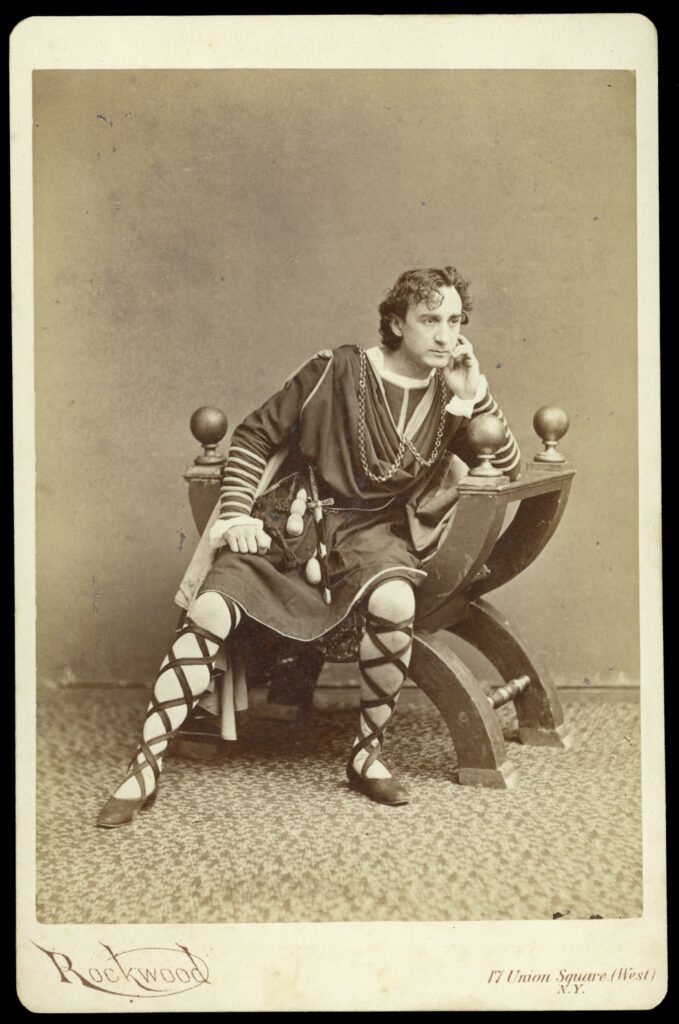

The invention of photography helped to create a new celebrity culture. Many actors and actresses posed for photographs in the costumes of their best-known roles. These photographs were turned into engravings or lithographs that could be easily reprinted in newspapers and magazines. Because early photography required people to remain still for a long time, actors in these pictures relied heavily on dramatic poses. It would have been impossible to photograph a live performance. Descriptions or reviews of Shakespeare’s plays that appeared in print often featured reproductions of these images of actors, helping to spread their fame far and wide and shifting the focus from the play’s author to the performer. Audiences began to think of “Edwin Booth’s Hamlet” instead of “Shakespeare’s Hamlet,” for example.

Theaters also made use of changing ideas about gender and often showcased women performers. This was a marked change from Shakespeare’s time, when women were not allowed on stage in England. Instead, all female roles were played by boys whose voices had not yet matured. While women began appearing on stage in the late seventeenth century, actresses really rose to prominence in the nineteenth century. Some women were even known for taking on male parts. Abraham Lincoln’s favorite actress was Charlotte Cushman (1816-1876), who, in addition to her well-known performances as Lady Macbeth, also played the roles of Hamlet and of Romeo opposite her own sister as Juliet in Romeo and Juliet. In 1895, the actress Sarah Bernhardt (1844-1923) became the first actor recorded on film as Hamlet – a role she continued to perform even after having one of her legs amputated. Featuring women in male roles reveals how people thought about masculinity and femininity in Shakespeare’s characters during the nineteenth century. Hamlet, in particular, was often considered a “feminine” character because of his philosophical, intellectual, and emotional nature; Claudius even declares Hamlet’s grief for his father “unmanly” (Act I, scene ii). Sometimes, though, it was the actors themselves who presented as masculine or feminine. Charlotte Cushman was so convincing in her portrayal of Romeo that playgoers wondered whether she was not actually a man. And surprisingly, Ulysses S. Grant played Desdemona in an 1845 U.S. Army production of Othello. It is hard to reconcile the popular image of an older, bearded Grant with the man who was described in his youth as “of fragile form” and “girlish modesty” and was nicknamed “Little Beauty” (Shaprio, Shakespeare in a Divided America). No matter which roles they played, men and women played parts for which they were famous for decades. Audiences didn’t care that the actors playing Romeo and Juliet might be in their seventies!

The Booth family, including the most-beloved actor of the American stage and the assassin of President Abraham Lincoln, forever altered the landscape of culture and politics in nineteenth-century America. Junius Brutus Booth, Sr. (1796-1852) was an English actor who emigrated to the United State in 1821. Booth had ten children, the most famous being Edwin Booth (1833-1893) and John Wilkes Booth (1839-1865). Edwin Booth was one of the most popular actors in America, but after his brother assassinated President Lincoln in April 1865, Booth abandoned the stage for over a year. He returned in Hamlet in New York in January 1866 due to public demand. Booth was a true American celebrity: fans could buy photographs of him (called cabinet cards), books of illustrations of him as different characters, and even sheet music that celebrated his looks and talent.

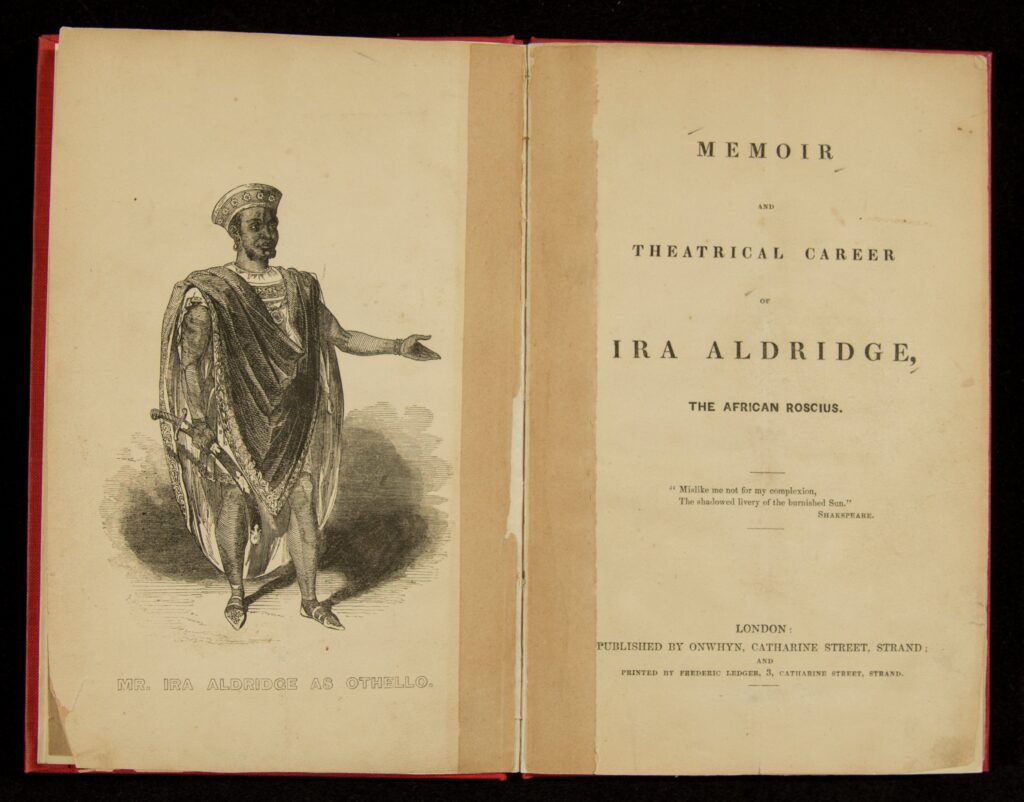

Another famous American actor was Ira Aldridge (1807-1867), who was the first black actor to appear on stage in England. Before that, black characters would have been played by white men in blackface (a practice that continued into the twentieth century). Aldridge made his debut as Othello in London in 1825. Although he was born in the United States, Aldridge created the myth that he was the descendant of a Senegalese prince whose family was forced to escape to America to save their lives. Aldridge became a star and forged a remarkable career in England. In addition to Othello, he played King Lear, Macbeth, and Richard III. Although he was a huge success in Europe, he never returned to the United States.

Performances – and performers – of Shakespeare in the nineteenth century would probably have surprised, and possibly bewildered, Shakespeare himself, while theatergoers would have increasingly recognized themselves and the world around them through productions of his plays.

Questions to Consider:

- From looking at these playbills, what can learn about how information was presented to theatergoers? What kind of details did theaters think might be important to potential audiences? Do we learn anything about the actors, the costumes, or the scenery? Compare, for example, the broadside playbills from the Princess’s Theatre (advertising Macbeth), the Royal Theatre Haymarket (advertising Edwin Booth as Richard III), and the McVicker’s playbill promoting Edwin Booth.

- In looking at the photographs below of Edwin Booth in costume, what clues do we see about his portrayals of Hamlet and Iago? What clues can you find in the costumes or scenery?

- How do the engraved illustrations of Booth differ from the photographs? What evidence suggests that they were intended for different audiences?

Selection: Images of Edwin Booth, ca. 1870s

- There exist a few wax cylinder recordings of Edwin Booth, including this one of him reciting a speech from Othello. While it is extremely difficult to hear him due to ambient noise, one can follow along using the text of the speech. What do you make of his voice and his style of speaking? Does it sound different than the way in which someone might perform Shakespeare today?

- How many plays are featured on John Allen Hosmer’s manuscript playbill? Can you figure out what kind of plays he enjoyed? Who do you think the performers were?

All the Rage: Shakespeare in Everyday Life

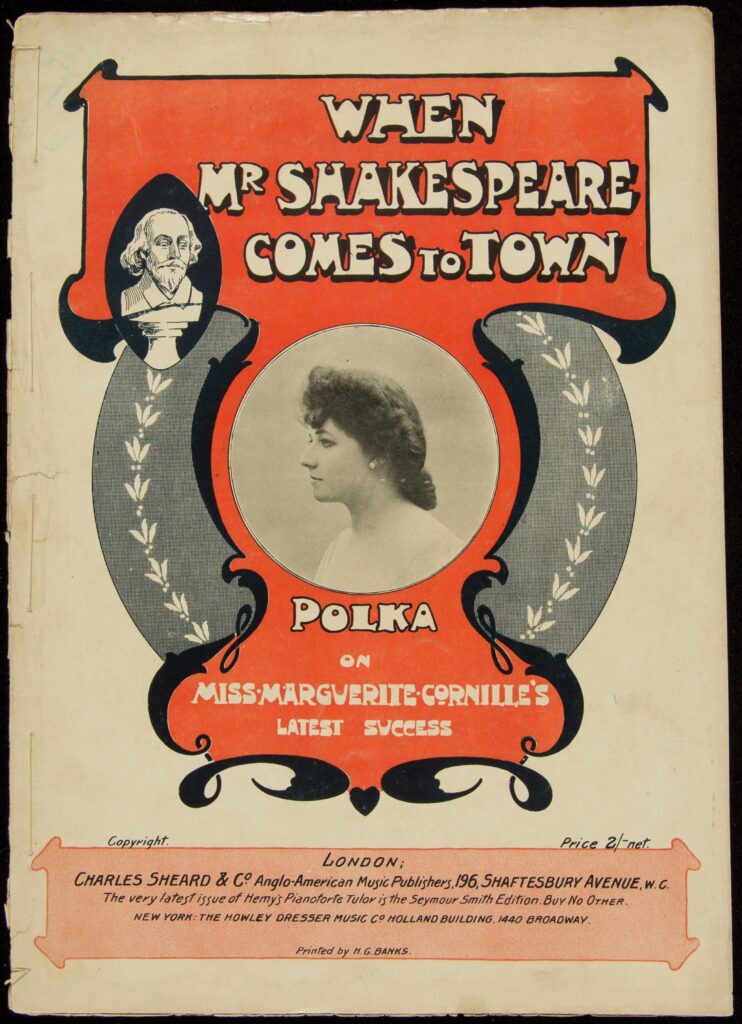

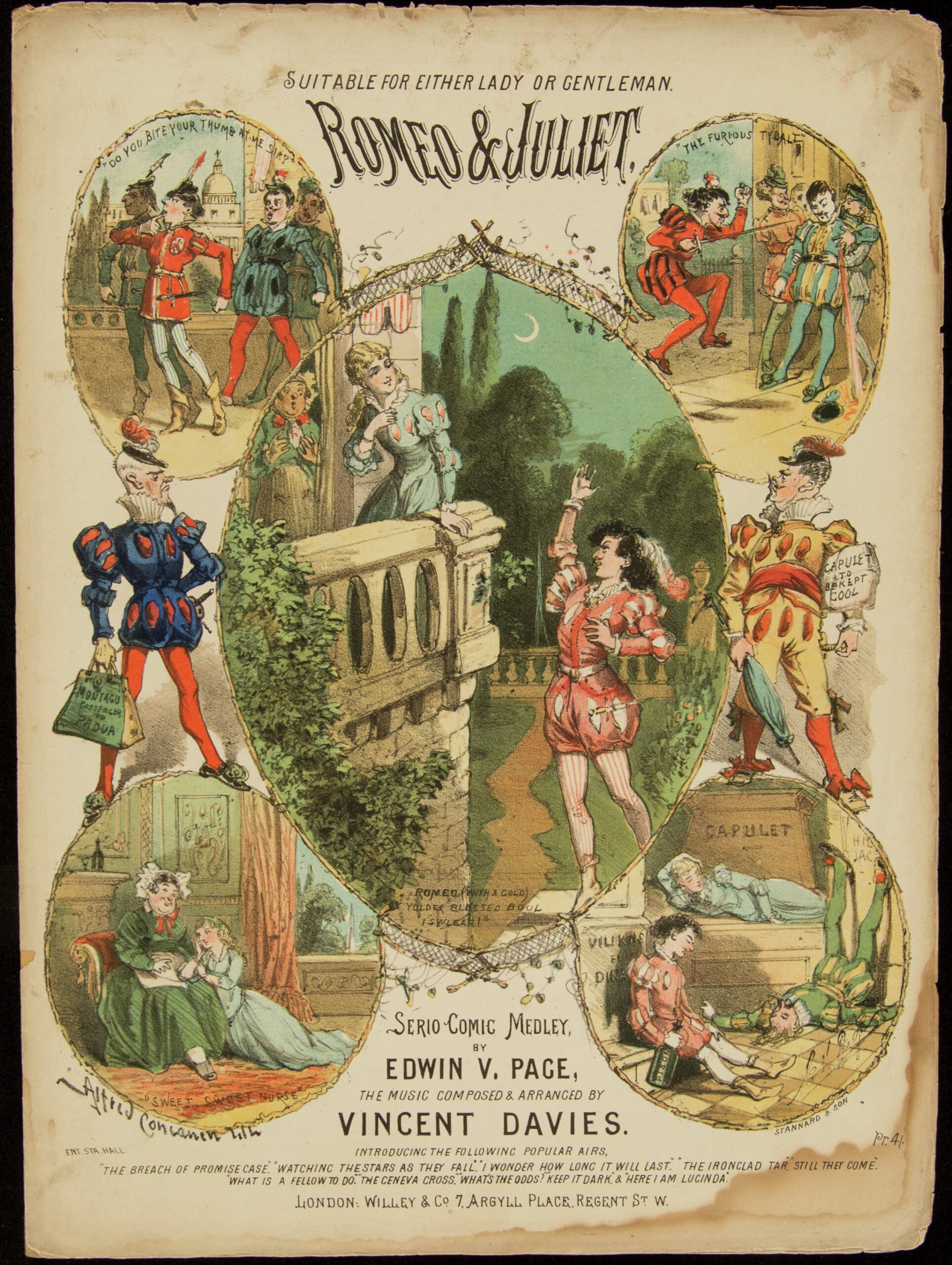

Nineteenth-century Americans did not have to read Shakespeare’s work or see it performed in order to encounter him in their daily lives. Shakespeare was, in fact, just about everywhere in popular culture. Today we might think of Shakespeare and music in relation to serious opera, like Giuseppe Verdi’s Otello, first performed in 1887. Musical Shakespeare was not limited to the opera or concert hall, though, but appeared in homes as part of everyday entertainment. The musically inclined could buy collections of Shakespeare songs and ballads, as well as of Shakespeare-themed sheet music for traditional as well as newly-composed songs. Shakespeare even became an integral part of weddings in the nineteenth century. In 1842, Felix Mendelssohn composed his “Wedding March” for Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream and the music is still used today as brides walk down the aisle.

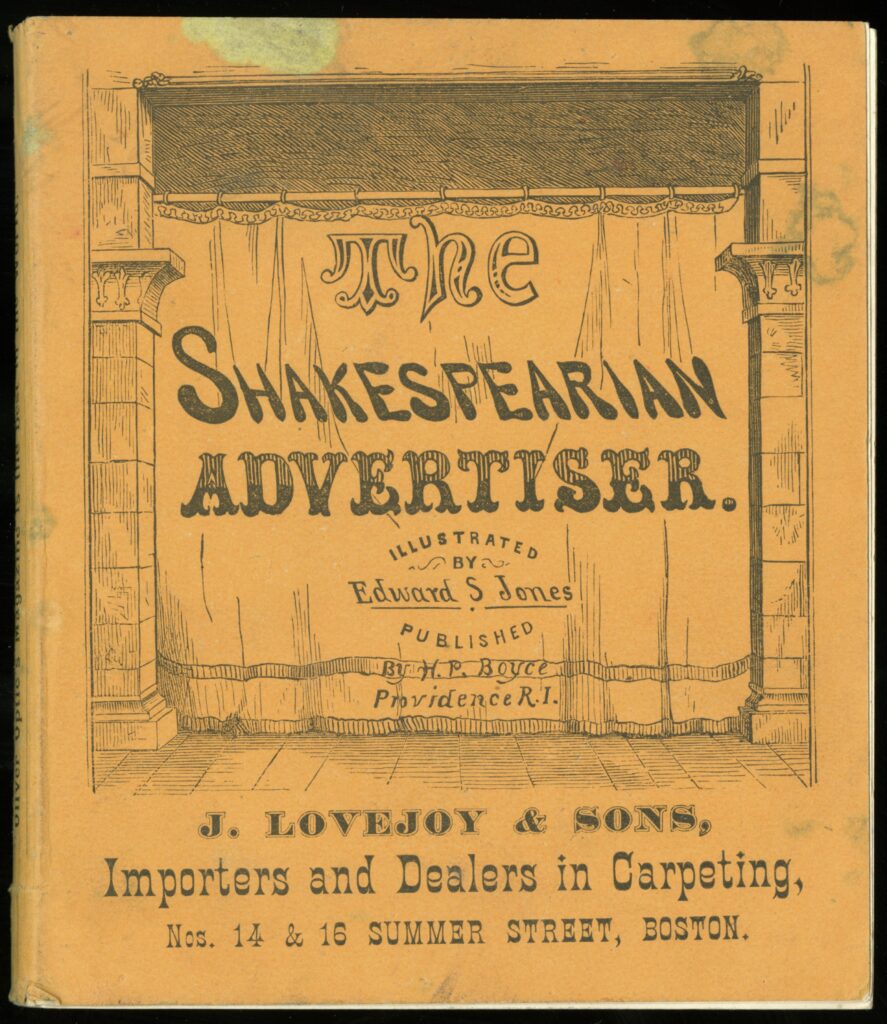

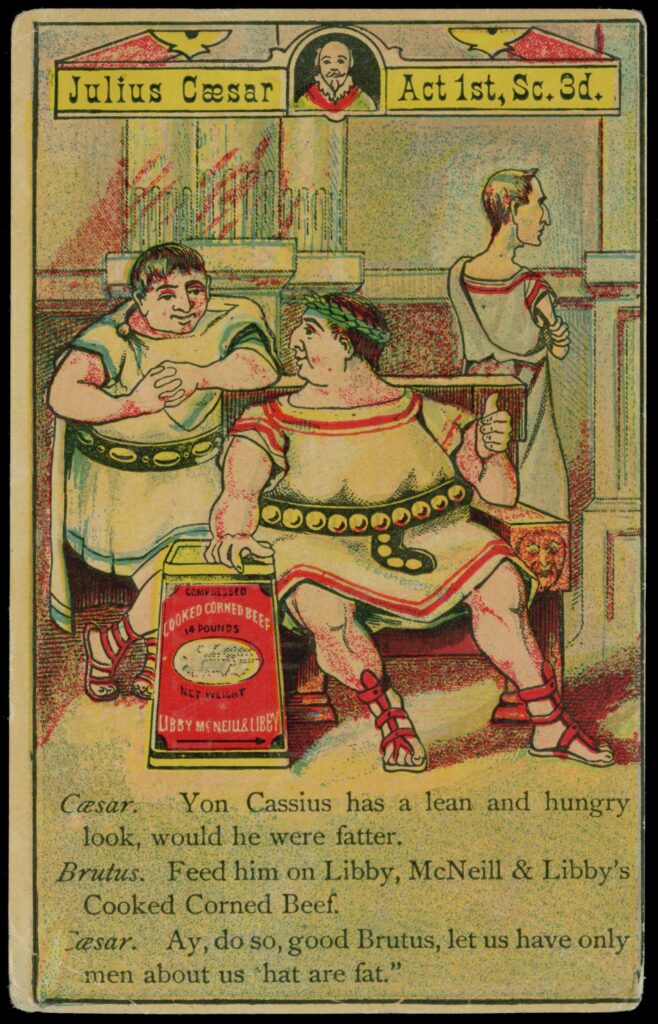

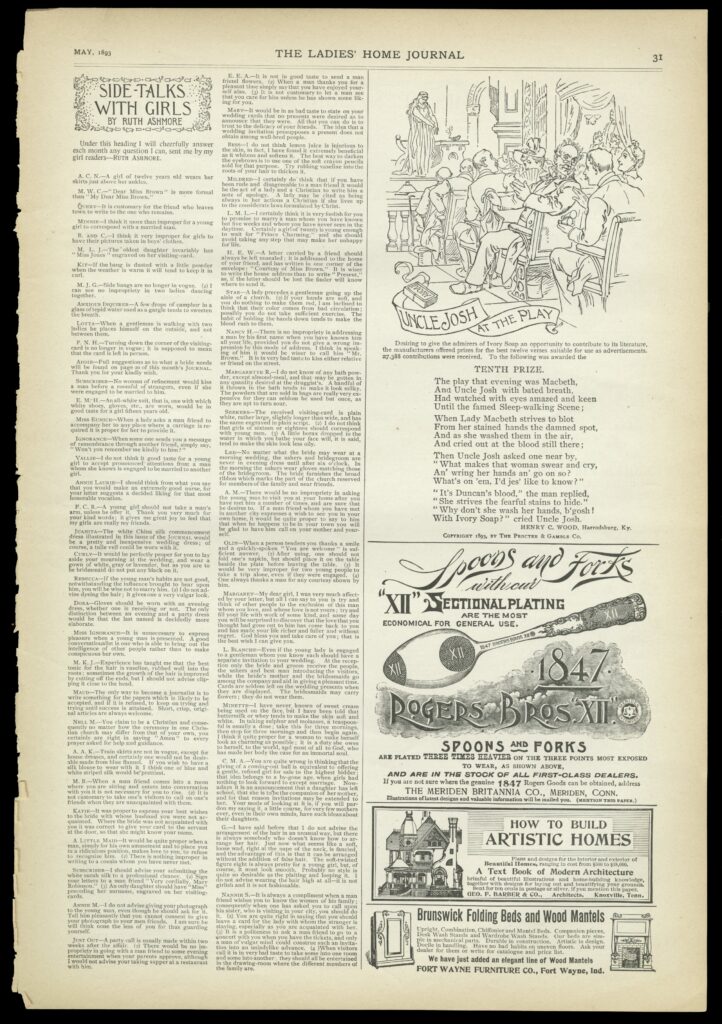

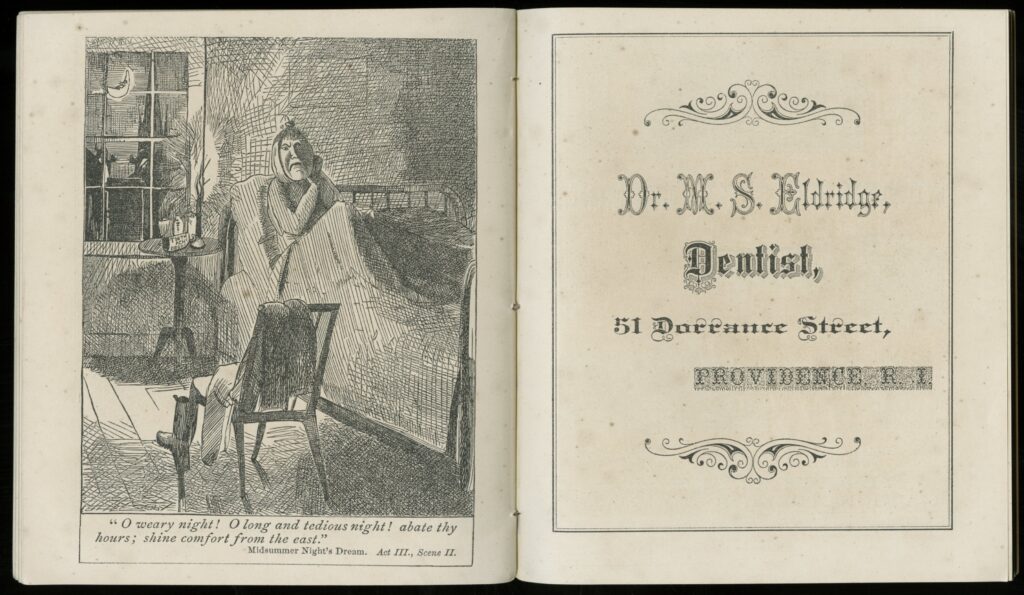

After the Civil War, the first modern advertising agencies were established in America (along with the modern concept of advertising) and by the late nineteenth century, Shakespeare was popular enough to sell just about anything, from soap, to clothing, to corned beef, to beer, to cars. In 1871, a directory from Providence, Rhode Island, The Shakespearian Advertiser (pictured in the Questions below), even used Shakespeare to sell business services. The publishers specifically commissioned comic illustrations of Shakespeare quotes to intersperse between advertisements for Rhode Island and Massachusetts businesses, in the hope that they would entice people to look through the entire booklet and pass it along to friends. Shakespeare-related advertising also took the form of trade cards. Often presented as a series of give-aways, with a brightly colored picture on the front and a publicity message on the back, the cards were meant to encourage customers to collect the series. Since these items were meant to be displayed in some fashion – on a wall or in an album – the products they advertised were always on view to existing or potential users. Although advertising trade cards had existed since the eighteenth century, in nineteenth-century century America they became radically different. While Shakespeare himself occasionally appeared on cards, in the United States, cards tended to feature specific plays, characters, or quotes. There were also parody cards that altered a quote or scene to make it seem as if Shakespeare himself were endorsing the product. For example, Libby’s canned meats found their way into the Tragedy of Julius Caesar, with Brutus being encouraged by Caesar to fatten up his fellow Roman senator Cassius on corned beef. By the late nineteenth century, Shakespeare advertising moved into popular periodicals. In 1893, Ivory Soap ran a contest offering prizes for the twelve best verses suitable for advertisements. Tenth prize went to a poem called “Uncle Josh at the Play” (pictured below), in which, during a performance of Macbeth, a sensible question is posed to Lady Macbeth, who is trying in vain to wash blood from her hands:

Why don’t she wash her hands, b’gosh!

With Ivory Soap”? cried Uncle Josh.

Advertisers continued to use Shakespeare to sell products through the mid-twentieth century; he was particularly favored by pen companies, but was also used to sell maps, alcohol, and even women’s underwear.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the creation of English literature as a field of study made Shakespeare a part of the school curriculum with students encouraged to read him in a serious manner with an eye towards literary criticism. New authors like L. Frank Baum, Willa Cather, Upton Sinclair, Eugene O’Neill, and F. Scott Fitzgerald offered readers works that captured their imaginations and surveyed the American experience. While Shakespeare never fell entirely out of fashion, his role in American culture nevertheless shifted.

In his preface to his 1765 edition of the plays of Shakespeare, Samuel Johnson calls Shakespeare “the poet of nature; the poet that holds up to his readers a faithful mirror of manners and of life.” And indeed, in the nineteenth century, Shakespeare was a mirror of American life. Publishers and theaters used Shakespeare to explore ideas about American ideals as well as problems facing the young nation. His works took on special meaning for a rapidly expanding country that had separated itself from Britain yet still felt culturally linked (or yoked) to it. Shakespeare’s plays speak deeply to the idea of identity and through them Americans confronted changing notions of gender, race, and class. Additionally, technological advances allowed more people than ever before to read and to “see” Shakespeare in new ways. Meanwhile, the emergence of an advertising culture worked to situate Shakespeare in Americans’ everyday life. Was Shakespeare the great author of America, as James Fenimore Cooper claimed? Perhaps not, but investigating Shakespeare of nineteenth-century America reveals much about how Americans saw themselves.

Questions to Consider:

- In looking at The Shakespearian Advertiser, why do you think that particular illustration was placed opposite an advertisement for a dentist? How do the illustration and the advertisement speak to each other?

Selection: The Shakespearian Advertiser, ca. 1871

- Read the advertisement for Ivory Soap in The Ladies’ Home Journal. What does this advertisement assume that readers will know about Macbeth? What kind of person do you think “Uncle Josh” is supposed to represent? Why would Lady Macbeth make such a terrific spokeswoman for Ivory Soap?

- Compare the Ivory Soap ad to the advertising card for Libby’s corned beef. Do you think that canned meat has any connection to Julius Caesar? Again, what does this card assume that the reader already knows?

- Are the two pieces of sheet music here comic or serious? What evidence do you find on the covers to support your argument?

Further Reading

Levine, Laurence. Highbrow/Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990).

O’Barr, William M. “A Brief History of Advertising in America.” Advertising & Society Review 6, no. 3 (2005).

Shapiro, James. Shakespeare in America: An Anthology from the Revolution to Now (Library of America #251, 2014)

———. Shakespeare in a Divided America: What His Plays Tell Us About Our Past and Future (New York: Penguin Press, 2020)

Taylor, Gary. Reinventing Shakespeare: A Cultural History, from the Restoration to the Present (New York: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1989)