Introduction

The fourteenth and fifteenth centuries in England were punctuated by a series of cataclysmic events that permanently altered the social, political, and institutional structures of society. Beginning with the Hundred Years War (1337) with France, England was wracked by expensive conflicts that drained royal coffers and demanded the invention of new forms of taxation that were received with open hostility. The advent of the Great Famine (1315-1317) and the Black Death (1348-1350) decimated the population and took an extraordinary toll on people’s lives. Crucially, the Black Death halved the working population and created huge labor shortages, which led to demands for better payment by those still able to work. This culminated in the Peasant’s Revolt or Great Rising of 1381, which contributed to the upending of the feudal and agrarian economic system that had dominated medieval England for centuries.

As these events beset the country, authors took to writing in the vernacular English language with a new sense of urgency and creativity. Whereas the languages of the court and church had for centuries been French and Latin, during this period more authors began deliberately writing in Middle English, partly out of a desire to create distance from a French court and a hierarchical Church with which England was increasingly dissatisfied. This also served to assert English as a national language, and to promote it as a vehicle for literary expression. The rise of Middle English literature and movements to translate the Bible and other spiritual texts into vernacular languages indexes the broader breakdown of reliance on traditional institutions for intellectual exchange or scriptural interpretation. This shift gradually paved the way for the more dramatic rift with the Church that took hold during the Reformation, as well as the expansion of literacy in the Early Modern period.

With these transformations in the background, literary authors writing in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries increasingly incorporated political thought into their works. The Newberry Library holds several of the most important works of fourteenth- and fifteenth-century literature produced in England, which respond to these moments of social upheaval and crisis. This DCC will provide an overview of these crises and explore their implications for literature, culture, and daily life during this period.

Guiding Questions:

- How do language choices reflect political concerns in late medieval English literature?

- What was the impact of the Black Death on religious culture, practice, and education?

- How did rulers respond to the social changes occurring in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries?

- Why did so many authors direct their texts to royal figures and government officials?

I. A Crisis of Authority: The Impact of the Black Death on Religious Life

What we now call the Black Death was first referred to in major medieval outbreaks as ‘the great mortality’, ‘the pestilence’, or simply ‘the death’. It arrived in 1348 and rapidly swept through the continent, ultimately killing between forty and sixty percent of the population in England. This had a tremendous impact on daily life. The poorer agrarian workers and the clergy were hit the hardest, while the wealthiest members of the population were able to quarantine more easily (though approximately twenty-five percent were still killed). In the Decameron, Giovanni Boccaccio writes that “the plight of the lower and most of the middle classes was even more pitiful to behold. Most of them remained in their houses, either through poverty or in hopes of safety, and fell sick by the thousands. Since they received no care and attention, almost all of them died.”[1] The disproportionate suffering by the lower classes contributed to a growing resentment towards the upper classes and the institutions designed to support them, leading to the breakdown of feudalism,the development of popular revolt, and changes in religious life that would pave the way for the Reformation. The Church was the most powerful political, economic, and cultural body in the medieval European world at this time, and as the country reeled from the devastation of the plague, much of the social and political criticism that emerged in its aftermath focused particularly on the Church’s institutional inadequacies.

A Shortage of Priests

Many people thought that the Black Death was a punishment from God for sin and societal corruption, and they turned to religion for solace, guidance, and repentance in the face of so much loss. Yet in some areas, it was difficult to find a priest. The medieval clergy was drastically affected by the plague, with death rates in English dioceses averaging forty-five to fifty percent. Priests were responsible for administering the last rites and attending to the sick and dying and as a result were put at a much higher risk of infection and death. As a result, there were fewer priests available to attend to their congregations, and there was a greater burden placed on individuals for securing their salvation in case they fell ill and could not avail themselves of the usual sacraments. Ralph of Shrewsbury, the Bishop of Bath and Wells, stated in 1349 that “we understand that [because of the pestilence] many people are dying without the sacrament of penance,” advising that “if when on the point of death they cannot secure the services of a properly ordained priest, they should make confession of their sins…to any lay person, even to a woman if a man is not available.” [2] Suggesting that “even a woman” might hear someone else’s confession shows how dire the situation was for clergy and laity alike and helps explain why books made for laypeople became so important in the later Middle Ages. This situation propelled lay movements across Europe that emphasized the importance of having access to the Bible in vernacular languages, so that people who didn’t understand Latin would still be able to comprehend the text and thereby be able to deepen their religious experience.

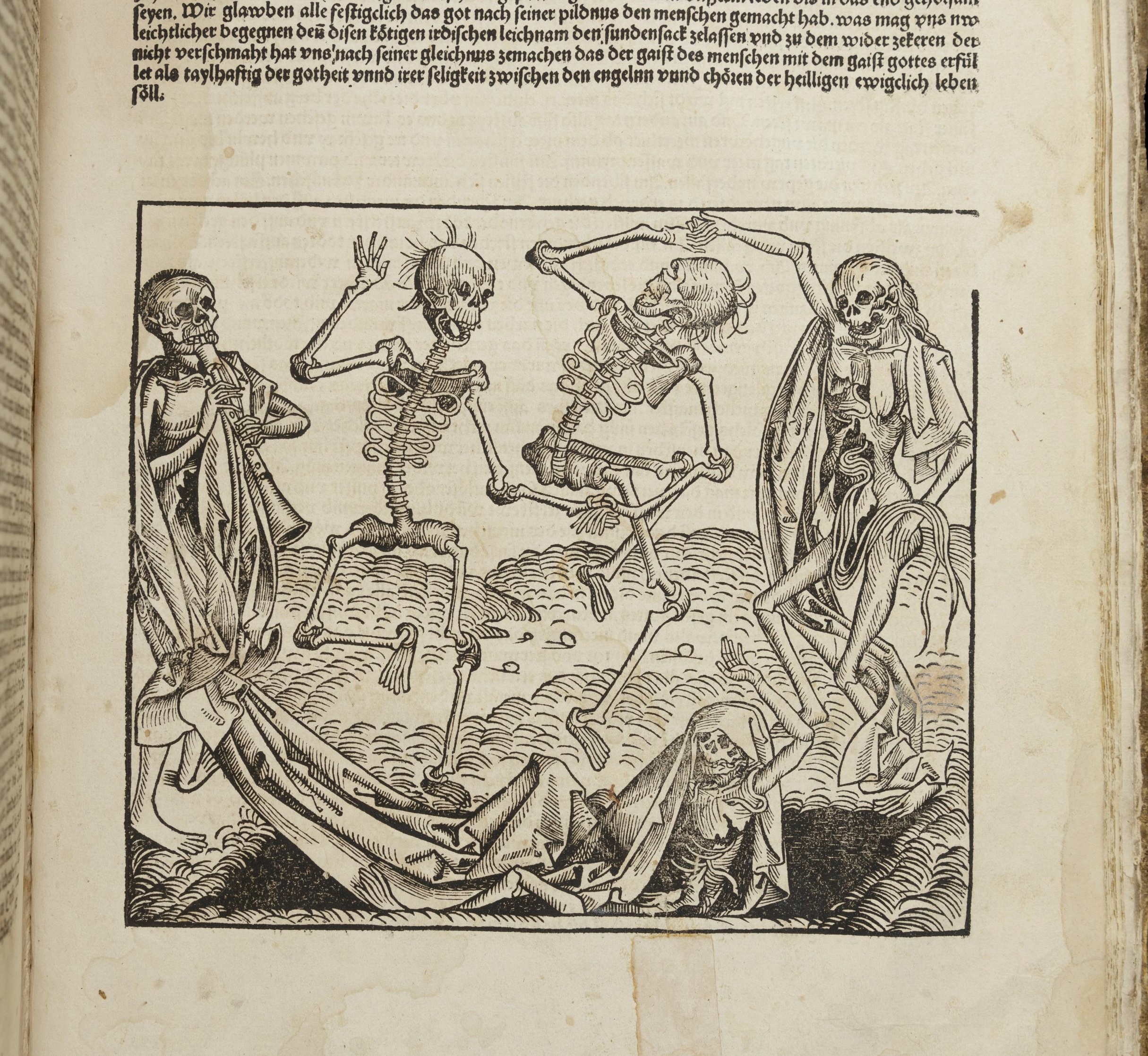

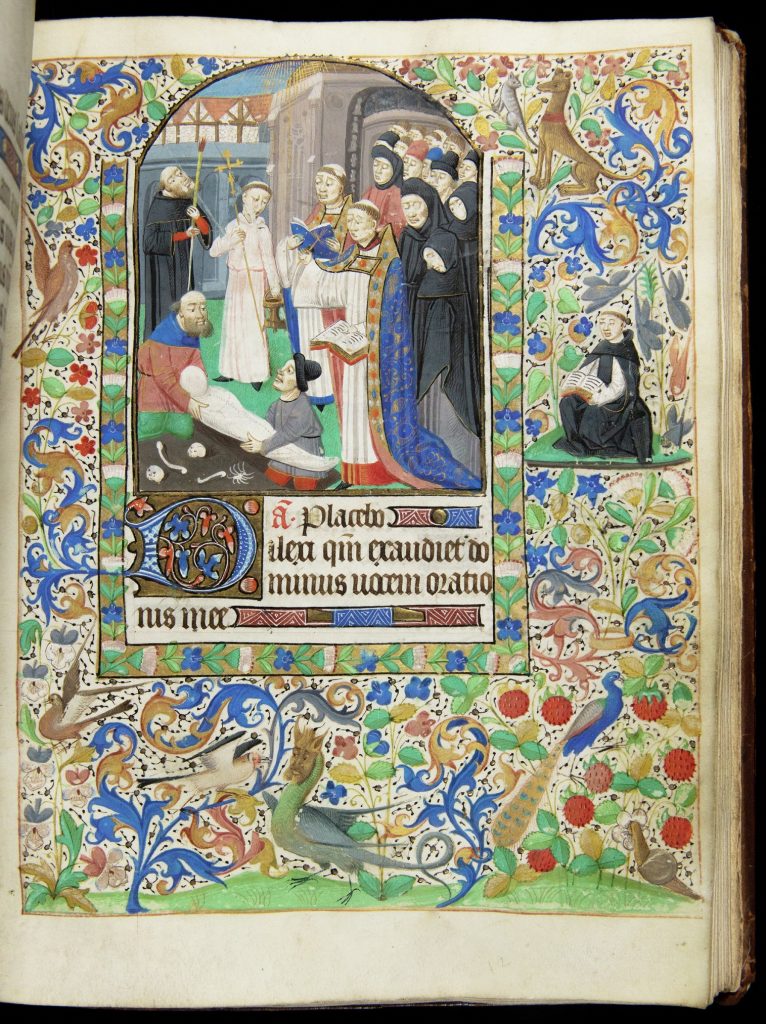

In addition to the renewed emphasis on translating the Bible into vernacular languages, during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries Books of Hours and lay primers became incredibly popular. Although Books of Hours were frequently commissioned and owned by the wealthiest members of society, their growing popularity indicated a growing desire for people to be able to pray and practice devotion at home. They were designed to provide men and women with a means by which they could participate in the same daily round of prayers and worship as monks and priests––the monastic Divine Office. They were the most popular books in the Middle Ages, surviving in far greater numbers than any other genre of manuscript. Their popularity shows how important it became for regular people to practice their devotion at home, and they were often written in both Latin and the vernacular to facilitate this. The Office of the Dead is the only text in the Books of Hours that replicates the exact same form the mass took when done by priests, and reciting and meditating on it was considered to be a powerful way to assist both the living and the souls of the departed find redemption. By having access to the Office of the Dead, people would be able to guide the dying towards heaven even if there were no priest available to perform these rites, and thus they were able to exercise more agency over the care and salvation of their souls. The illumination of the Office of the Dead from a Book of Hours produced in France c. 1470 shows a typical scene: a burial with attendants reciting the prayers of the Office. The skulls and bones around the grave show that the body was being interred in an overcrowded cemetery.

Death: The Great Equalizer

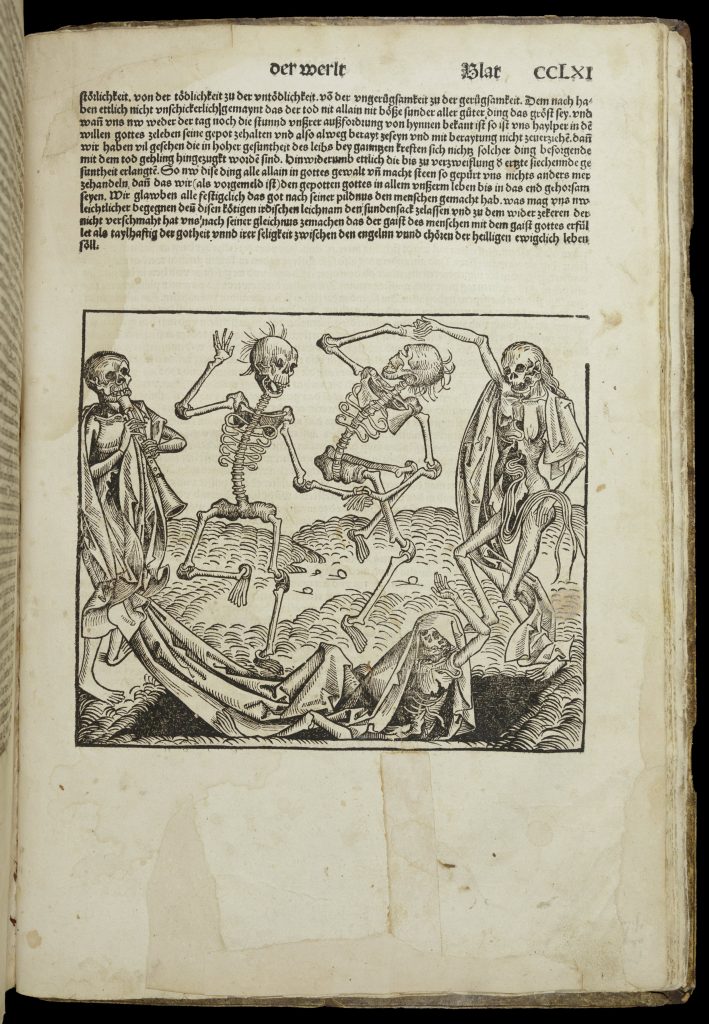

A number of motifs emerged in religious art and architecture that emphasized the transience of life, the importance of preparing for a “good death,” and the fact that death comes for all, regardless of wealth, status, or power. Images like the one below, of the Danse Macabre, or Dance of Death, reflect the idea that all people are fundamentally equal before God. The Danse Macabre was originally a mural in the Holy Innocents’ Cemetery in Paris, and it depicted fifteen dancing couples, comprised of one living and one deceased partner, who are framed by an author who introduces and concludes the dance. The mural was accompanied by written verses––often humorous dialogue––placed below each figure. The grinning, dancing skeletons mocked the living by poking fun at their dismay and, for those in positions of power, by making light of their high status. Enjoy it now, the skeletons implied, because it’s not going to last long! This motif became immensely popular, and appeared in many textual and visual sources. Hans Holbein’s version of the Dance of Death, produced between 1523 and 1526, is perhaps the best known. Instead of dancing, in Holbein’s version, Death aggressively pursues people from a wide range of occupations, including the pope, the emperor, kings and queens, merchants, friars, and beggars.

Condemning Corruption: Anticlericalism

The reputation of the Church was already in decline by the time the plague arrived and reduced the number of priests. The Black Death saw the rise of the flagellant movement, in which groups of men and women publicly flogged themselves while preaching a radically deinstitutionalized form of Christianity, incurring the condemnation by the Church but ultimately exposing its weakness. Heretical sects of Christianity proliferated in Western Europe, and while not all of these were as zealous as the flagellants, they shared a conviction that the Church was failing in its essential purpose. Antisemitic violence also increased as Christians sought a scapegoat to blame for the spread of the disease. Although the Church condemned this activity, the persistence of violence against Jewish people revealed deeper fractures in its ability to control or assuage the congregation.

As the Church was the wealthiest and most politically powerful institution throughout the Middle Ages, it became a focal point for accusations of decadence, corruption, and hypocrisy after the Black Death. The mendicant orders (Franciscans, Dominicans, Carmelites, and others) had proliferated since the early thirteenth century, and by the late-fourteenth century they became subject to increasing scorn and vilification. Criticism of friars, the papacy, and the institutional Church was known as “anticlericalism,” and anticlerical literature became a popular genre of complaint. Friars received especially vicious attacks, as they relied on charitable donations for their living and were reputed to take alms greedily and indiscriminately, amassing small fortunes for themselves whilst neglecting the spiritual welfare of the larger community.

Chaucer’s “Summoner’s Tale” in The Canterbury Tales illustrates this in a particularly vivid manner. Summoners were Church officials responsible for bringing people to ecclesiastical courts for punishments, and they were widely reviled in medieval society. Chaucer’s Summoner responds to his own negative portrayal in the preceding “Friar’s Tale,” and in his rebuke he offers the Friar a vision of hell. He describes how in a dream, a friar goes down to hell and sees many people suffering great torments, but he cannot see a single friar. He asks an angel if this is because friars are so blessed that they never wind up there. The angel says no, there are many friars here, they are just hidden. The angel points to the large tail covering Satan’s bottom, and asks him to lift it up. When he does so, thousands of friars come streaming out of Satan’s rear end, like bees coming out of a hive. The friar then wakes up and becomes concerned about the fate in store for him. Chaucer’s Summoner criticizes friars in colorful and embellished terms, yet in so doing, he speaks to a wider societal disillusionment with those who profess to work in service of the Church, but who act chiefly in self-interest.

Dissent: John Wycliffe and the Lollards

One of the most notorious critics of the institutional Church was John Wycliffe, whose heretical criticism became denigrated as “Lollardy” and whose followers were referred to as “Lollards.” John Wycliffe was a theologian who taught at Oxford. He became distressed with the degree of corruption and venality he saw throughout the clergy and the power they had over the laity, and vehemently sought major church reform. He believed that the Bible was the supreme authority, not the Church, that there was no scriptural justification for the authority and power of the Pope, and that clergy should not be allowed to hold property.

When the pope would not help Wycliffe with his push to reform, he turned to the state, and for a time enjoyed the favor of John of Gaunt and other important lay magnates, though this too was short-lived. His growing disillusionment led him to revise his beliefs about some of the most fundamental aspects of Catholic dogma: for example, he rejected the doctrine of transubstantiation (the process whereby during communion the bread and wine are transformed into Christ’s body and blood). He was brought to trial in 1377, and he and his writings were condemned as heretical in 1382, but he did not face punishment and continued writing until his death in 1384. Wycliffe’s most enduring legacy was his attempt to translate the Bible into the vernacular, so the majority of people who could not read Latin or French would be able to read it as well; this threatened the ability of the Church to read and interpret the Bible for them. In 1401, the parliamentary order De heretico comburendo forbade the translation of the Bible into any vernacular language, and attempted to crack down on extant and developing heretical movements. Forty-one years after his death, Wycliffe was officially condemned as a heretic, his books were burned, and his body was exhumed and burned. His ideas persisted, however, and propelled the transformation of religious life leading up to the Protestant Reformation.

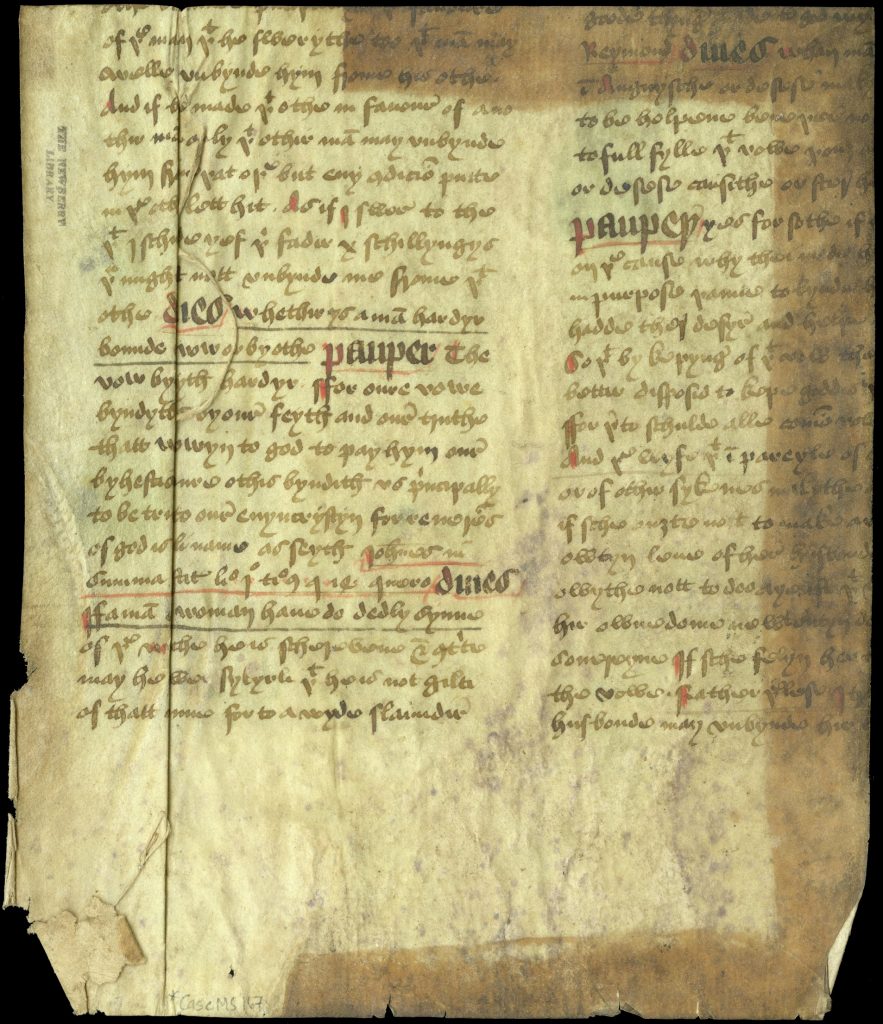

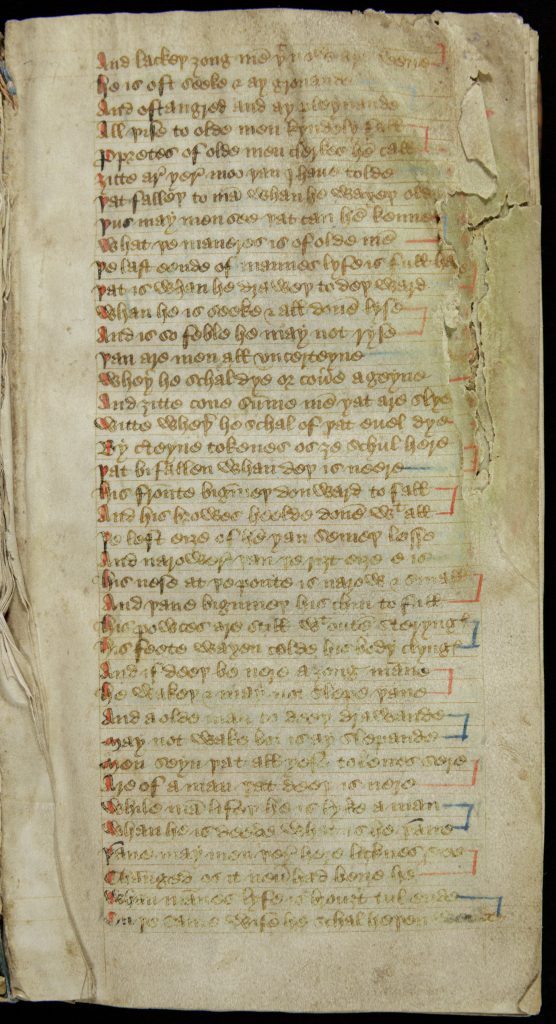

Although a layperson might not have access to an ornate Book of Hours or a copy of the Bible, during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, many texts of religious instruction began to appear in the vernacular. The Pricke of Conscience is a Middle English poem written during the fourteenth century that exemplifies this genre of religious poetry. The poem exists in more manuscripts–approximately 130–than any other Middle English poem. Its title refers to the stirrings of compunction or remorse in the conscience for sin, and the text elaborates a program of penitential reflection and practice. Over the course of seven sections, the anonymous author elaborates on central theological questions such as humankind’s sinfulness, the transient nature of the world, what to expect in purgatory, hell, or heaven. Importantly, the author offers paraphrases and interpretations of biblical passages, so that the reader (or listening audience) would glean knowledge of the text in the vernacular language. The Newberry owns two copies of this important example of medieval English religious poetry.

Guiding Questions:

- How did the Black Death impact the development of lay piety in late Middle Ages, and how did this precede the religious changes that arose during the Protestant Reformation?

- What was the purpose of the macabre imagery in Books of Hours and other late-medieval visual and literary sources?

- How did the shortage of priests shape religious practice?

- How did the institutional Church come under criticism in the aftermath of the plague?

- Why do you think a text like the Pricke of Conscience would become the most popular poem during the late-medieval period?

II. Writing in the Vernacular

This heightened attention to the use of English had political and literary implications as well as religious ones. When Henry IV came to the throne in 1399, he was the first king since the Norman Conquest of 1066 who spoke English as his native language.

To sketch linguistic custom out in the simplest terms, a writer in England during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries would have had three primary languages to use: the vernacular Middle English, emerging as the preferred vehicle for literary production; French, which remained the dominant language of the court and was often the default for official governmental writing; and Latin, the language of the Church. When authors chose to write in English or French, they were making a deliberate choice about the nature of their audience, and in this regard their choice was political. If they were writing in English, it was to edify, entertain, or instruct the unlearned masses. If they wrote in French or Latin, it was likely to communicate with educated peers—clerics and government officials who would know these languages as a matter of course. The use of English enabled writers to develop and celebrate a sense of national identity and community. As the scholar Thorlac Turville-Peter has said, “the very act of writing in English is a statement about belonging.” [3]

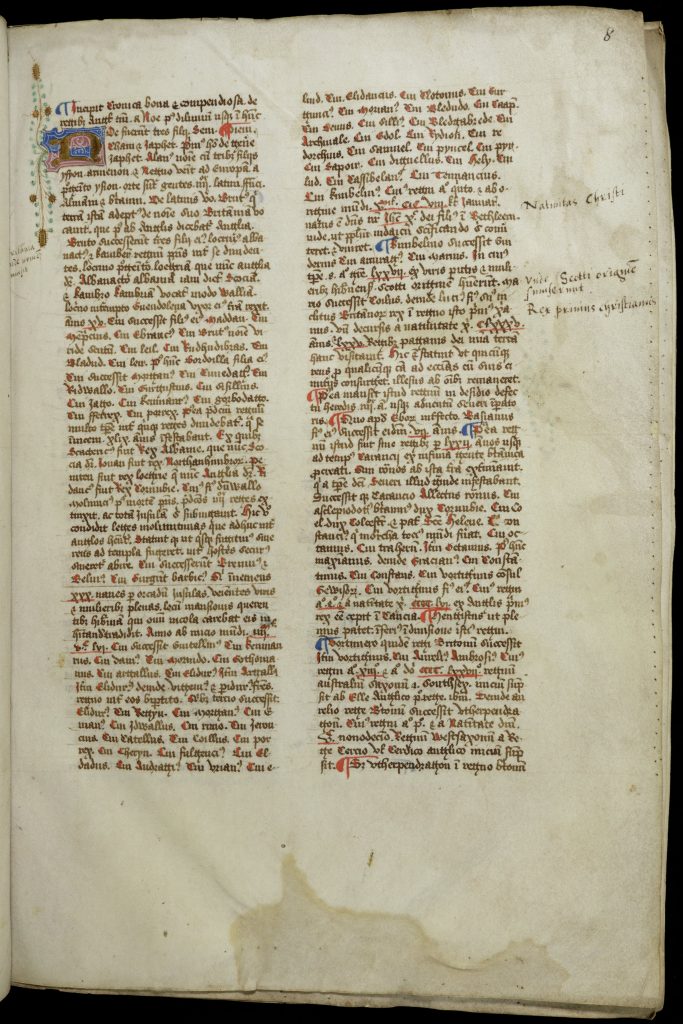

The Polychronicon

In 1386, John Trevisa produced a Middle English translation of Ranulf Higden’s Polychronicon, an ambitious work of history that was widely copied and read in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The Newberry owns a copy of this manuscript in Latin, where Higden introduces his subject by reflecting on the multilingualism throughout the British Isles. He describes how

Children in school, contrary to the usage and custom of other nations, are compelled to drop their own language and to construe their lessons and other tasks in French, and have done so since the Normans first came to England. Also, gentlemen’s children are taught to speak French from the time that they are rocked in their cradles and can talk and play with a child’s toy; and provincial men want to liken themselves to

Trevisa’s translation of Polychronicon Ranulphi Higden monachi Cestrensis . . . ed. Rev. Joseph Rawson Lumby (Liechtensteon: Krause Reprint, 1965).gentlemen, and try with great effort to speak French, so as to be more thought of. [4]

In his translation, Trevisa expands this meditation on language, noting how English is evolving into the sum of the many parts that comprise its founding by Norman, Danish, and Germanic settlers. He asserts the utility of a dominant language, given that regional dialects and languages such as Gaelic and Welsh are not mutually comprehensible. He also amends the situation Higden described in the quote above, noting that:

This fashion was much followed before the first plague [1348] and is since somewhat changed […] Now, the year of our Lord one thousand, three hundred, four score and five, in all the grammar schools of England, children leave French, and construe and learn in English.

Trevisa’s translation of Polychronicon Ranulphi Higden monachi Cestrensis . . . ed. Rev. Joseph Rawson Lumby (Liechtensteon: Krause Reprint, 1965).

Also gentlemen have now to a great extent stopped teaching their children French. It seems a great wonder how English, that is the native tongue of Englishmen and their own language and tongue, is so diverse in pronunciation in this island, and the language of Normandy is a newcomer from another land and has one pronunciation among all men that speak it correctly in England.

Trevisa’s accounting of the English language after the plague shows how dramatically educational norms evolved in the years after the plague. In 1362, the Parliament enacted the Statute of Pleading, which mandated that all pleas in the court be made, answered, and judged in the English language. While French was still held in high esteem in aristocratic circles, we can see how the use of English was quickly expanding because it was mutually intelligible throughout the country. This also reflected the shifting allegiances that resulted from the ongoing conflicts with France during the Hundred Years War. Finally, texts like the Polychronicon also provided English readers with biblical paraphrases that they could read and understand, responding to the desire for spiritual texts in the vernacular while it was still forbidden to translate the Bible.

Guiding Questions:

- Who do you think Higden intended the audience of the Polychronicon to be? What about Trevisa and his translation?

- Why would these meditations on language and linguistic customs precede a work of general history?

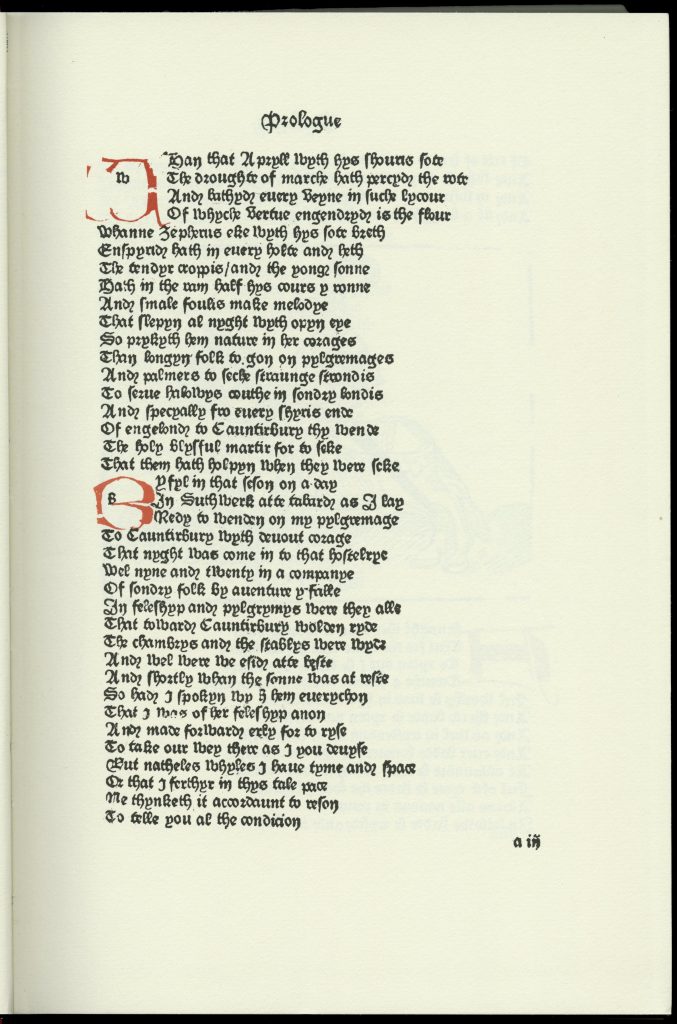

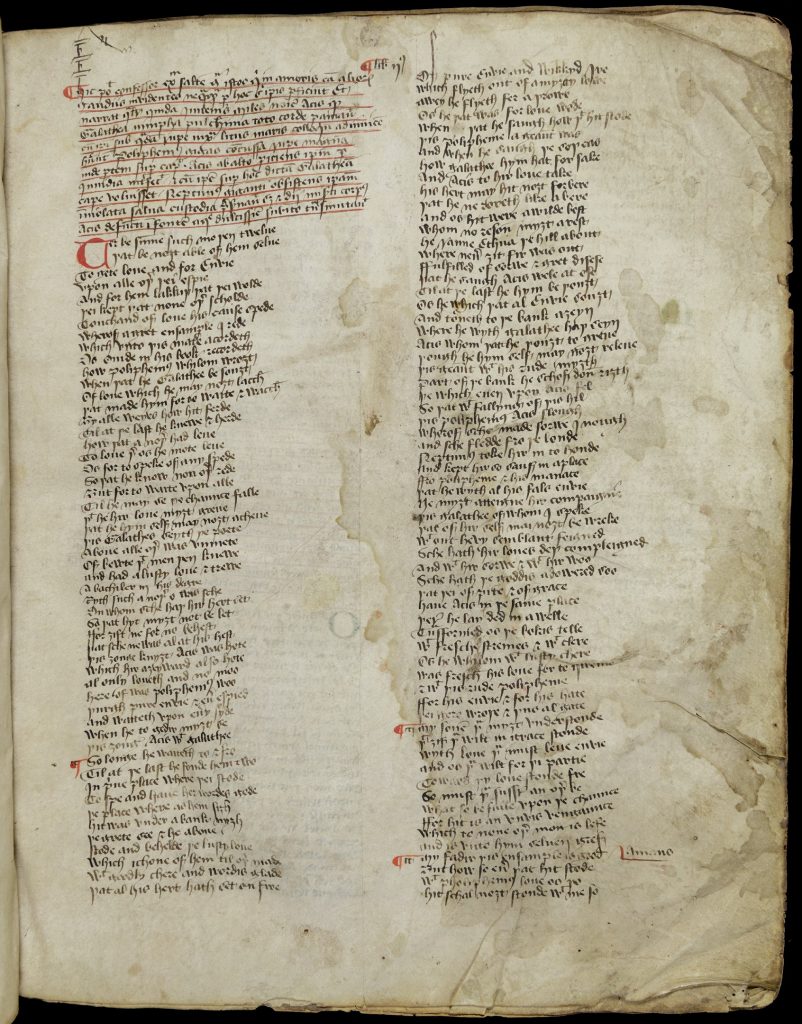

Middle English Literature

The literature of late-medieval England cannot be understood without reference to these shifting mores around linguistic custom. Geoffrey Chaucer receives credit for being the “father of English literature” in part because he made the choice to write his poetry in English, instead of what was regarded as the artistically superior French or Latin. He translated texts like Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy from Latin to English, and the Romance of the Rose from French. Chaucer’s work is saturated with a self-awareness of the linguistic choices he makes. For example, his poem the Complaint of Venus ends with a self-effacing apology for using a verse style in English better suited to “hem that maken [poetry] in Fraunce.” [4] (A selection from Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales is pictured in the Introduction.) In the Regiment of Princes, the poet and bureaucrat Thomas Hoccleve constructs an encomium (eulogy) to Chaucer, referring to him as “the firste fyndere of our fair language” and “the honour of Englissh tonge,” lamenting that his death “didest nat harm singuler…but al this land it smertith” [did not harm anyone singularly, but caused the entire country pain]. [5] Hoccleve discusses Chaucer in the context of his own literary work, a mirror for princes written for Prince Henry before his accession to the throne. “Mirrors for princes” were a literary genre that offered advice and counsel to rulers for leadership, usually reviewing all the habits and virtues an ideal leader should have. Hoccleve’s choice to compose his in English, while aligning himself with Chaucer’s literary lineage, is a way to promote both himself and the validity of the English language for the highest political office in the country.

Guiding Questions:

- Why does Hoccleve draw so much attention to Chaucer, a writer he claims is much better than him? Is it purely because of humility, or could it be something else?

- Find a version of Chaucer’s General Prologue to the Canterbury Tales and try to determine the etymology of the words he uses. Notice how many words from French and Latin he incorporates. What can this tell you about the state of English literary writing? How might authors and readers negotiate these competing languages in the late medieval period?

III. Popular Uprising: The Peasant’s Revolt of 1381

The Peasant’s Revolt, or Great Rising, stemmed from resentment against the English throne for the taxes and fines levied to support the long and messy Hundred Years War. It was also a product of the immense demographic shift that began with the Great Famine and reached its apex during the plague years. Cycles of crop failures, chronic hunger, and disease further reduced the productivity of laborers, which led to continued increases in the cost of living and a steady devaluation in standards of living. The mortality rate amongst the peasantry meant that in the decades after the Black Death, land was plentiful and labor was in much shorter supply. Thus laborers could charge more for work, driving wages upwards. The authorities responded with emergency legislation, the Ordinance of Laborers in 1349 and the Statute of Laborers in 1351. These attempted to fix wages at pre-plague levels, making it a crime to refuse work or to break an existing contract, punishable by branding or imprisonment. The revolt was prompted by these ordinances as well as the institution of a new form of taxation called the poll tax which was levied on every person over the age of 14. These decisions were incredibly unpopular and led to open protest. A full revolt began in May of 1381, and spread rapidly across the country. The rebels marched into London, destroying the legal buildings and the houses of officials around Westminster, and bringing tax records out into the street and setting them on fire. They burned down the Savoy Palace, a huge and luxurious building belonging to John of Gaunt, the Duke of Lancaster, they opened the Westminster and Newgate prisons, and they took over the Tower of London. The young king Richard II, eleven at the time, met with the rebels in the hopes of establishing a truce, but this fell apart after the rebels beheaded powerful figures like the Archbishop Sudbury and the treasurer Robert Hales. Although the Rising was ultimately suppressed, over the next fifty years life for peasants improved significantly, and many made more money and gained greater freedoms.

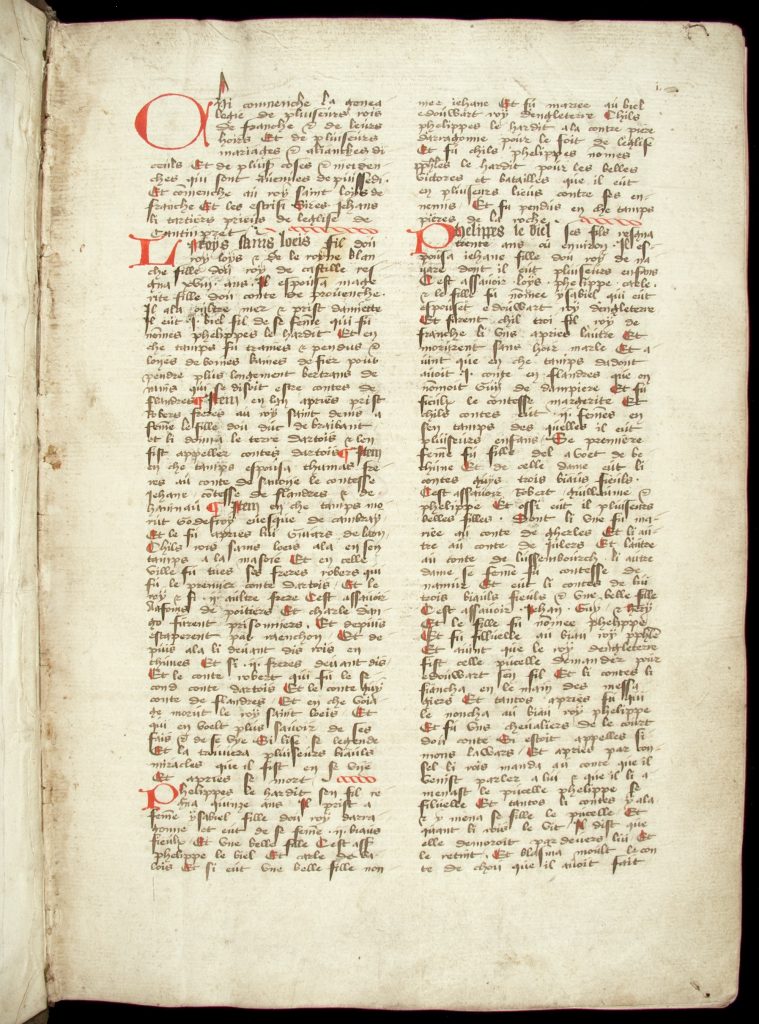

Jean Froissart’s Chronicles

Jean Froissart’s Chronicles are an important source for the history of France and England during the fourteenth century. They document the history of France and England from around 1326 through 1400, and are especially valuable for the account of the Hundred Years War. The Newberry owns two manuscripts, which contain Books I and II. This image from Book I shows the “Genealogy of the Kings of France,” and it was precisely over France’s throne that the Hundred Years War was fought. Froissart used both historical and eyewitness accounts to describe the politics of this period across four volumes, with particular emphasis on the Hundred Years War between England and France. Froissart also covers the Peasant’s Revolt, his account of which is excerpted below:

The evil-disposed in these districts began to rise, saying, they were too severely oppressed; that at the beginning of the world there were no slaves, and that no one ought to be treated as such, unless he had committed treason against his lord, as Lucifer had done against God: but they had done no such thing, for they were neither angels nor spirits, but men formed after the same likeness with their lords, who treated them as beasts. This they would not longer bear, but had determined to be free, and if they labored or did any other works for their lords, they would be paid for it.

A crazy priest in the county of Kent, called John Ball, who for his absurd preaching, had been thrice confined in the prison of the archbishop of Canterbury, was greatly instrumental in inflaming them with those ideas. He was accustomed, every Sunday after mass, as the people were coming out of the church, to preach to them in the market places and assemble a crowd around him; to whom he would say, —

‘My good friends, things cannot go on well in England, nor ever will until everything shall be in common; when there shall be neither vassal nor lord, and all distinctions levelled; when the lords shall be no more masters than ourselves. How ill have they used us! and for what reason do they hold us in bondage? Are we not all descended from the same parents, Adam and Eve? and what can they show, or what reasons give, why they should be more the masters than ourselves? except, perhaps, in making us labor and work, for them to spend.’

Jean Froissart, “Tales from Froissart,” Book II, chapter 73. Edited by Steve Muhlberger (Nipissing University: Internet Medieval Sourcebook. Accessed October 15, 2020.

Guiding Questions:

- How might the rise in prominence of vernacular English be connected to the Great Rising?

- How does Froissart characterize the Peasant’s Revolt? What does his characterization tell you about his opinion of the uprising? How does it impact your interpretation of the events he describes?

IV. Courtly Reform: Writing for the King

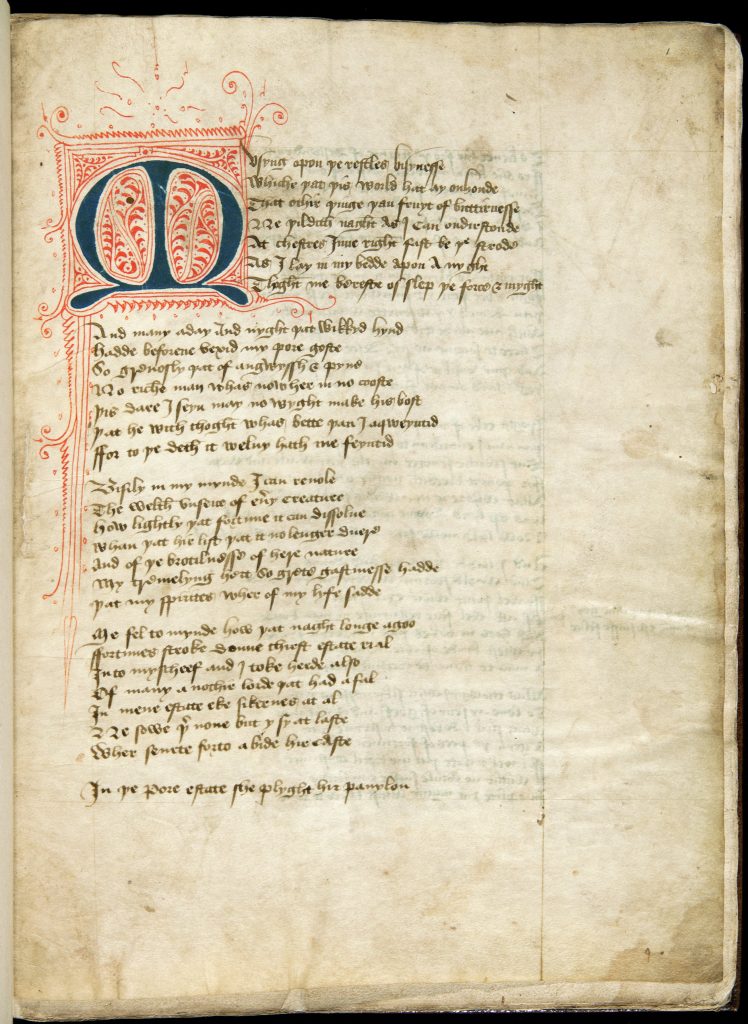

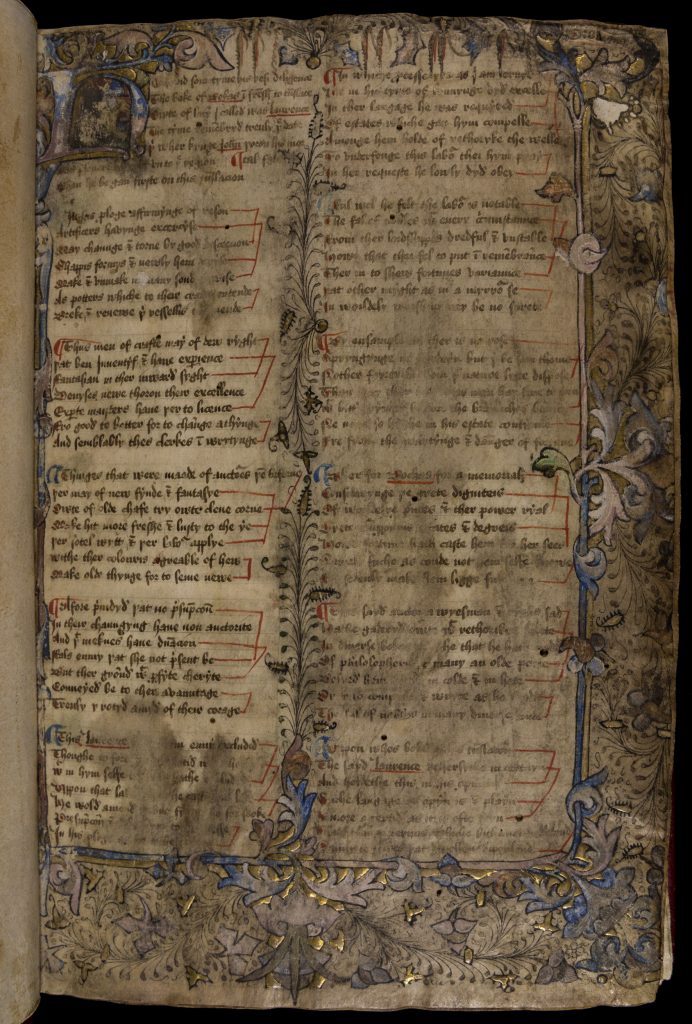

The end of the fourteenth and the beginning of the fifteenth centuries in England marked a time where the government was keen to rein in some of the dissent and upheaval that characterized the years after the Black Death. Following the rise of the English language in prominence and respectability in the fourteenth century, more members of the upper and noble classes began to support writers through patronage during the fifteenth century. Geoffrey Chaucer, for example, entertained Edward III’s court with stories and music and conducted numerous diplomatic missions for the English throne over the course of his life. Thomas Hoccleve, as mentioned, wrote his major poem the Regiment of Princes for Henry V, where he also provides a detailed account of his experience working as a bureaucrat in the Office of the Privy Seal. John Gower was a friend of Chaucer’s who reportedly began work on the Confessio Amantis after a chance meeting with King Richard II by the Thames. Gower’s Confessio Amantis was composed at the behest of King Richard II and is one of the best-known works of fourteenth-century English literature. Gower’s earlier works were written in Anglo-Norman French and Latin, so the fact that this is in English signifies a broader trend towards writing literature in the vernacular. John Lydgate was a Benedictine monk who wrote prodigiously on a variety of subjects. His best-known text, the Fall of Princes, was commissioned by his patron Humphrey, the Duke of Gloucester, brother to Henry V and the protector of England when the infant Henry VI took the throne in 1422.

Most of the major poets of the fifteenth century enjoyed a close proximity to the royal court, but this did not mean that they censored their own opinions when writing about politics or current events. Hoccleve’s text, for example, sharply critiques the treatment of the poor and laments the ongoing war with France, begging the Prince to work towards peace. John Gower characterizes those who began the Peasant’s Revolt as beasts incapable of rational thought. John Lydgate’s Fall of Princes is a Middle English poem composed between 1431 and 1438. The poem recounts the lives and tragic deaths of nearly 500 figures from history, the Bible, and classical mythology, beginning with the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eve to the capture of King John of France by the English in 1356. In presenting their various tragic ends, Lydgate analyzes the reasons behind their fall from good fortune to adversity. The poem, like Thomas Hoccelve’s Regiment of Princes, belongs to the “mirrors for princes” genre. These would not only catalogue all of the virtues that were required for good governance, but they would also teach how not to rule by negative example. As Lydgate evaluates the downfall of various powerful men and women, he also probes the vicissitudes in fortune faced by England’s current and recent rulers.

Guiding Questions:

- Why would a royal figure like Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, commission the Fall of Princes, which elaborates on how historical royal figures have misbehaved and met unfortunate ends?

- This manuscript page at the Newberry is quite damaged. What can you decipher from the damage on the page? What might this reveal about how the manuscript was used by readers? Who do you think those readers were?

- In the Prologue to Confessio Amantis, John Gower writes of his intent to create “A bok for Engelondes sake” (23-4). Given his opinion of the Peasant’s Revolt, what can you surmise about his intentions?

[1] Giovanni Boccacio, The Decameron, trans. Richard Aldington (Westminster: The Folio Society, 1955): 5-6.

[2] Ralph of Shrewsbury, Bishop of Bath and Wells. Reproduced in Rosemary Horrox, The Black Death (Manchester, 1994), 271-3.

[3] T.Turville-Peter, England the Nation (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996), 11. Wendy Scase, “Nation, Identity, and Otherness,” New Medieval Literatures, IV (2001): 1-8.

[4] Chaucer, The Complete Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, ed. F.N. Robinson, 2nd edn (London: Oxford University Press, 1957), 538.

[5] Thomas Hoccleve, The Regiment of Princes, ed. C.R. Blyth, METS (Kalamazoo, Michigan, 1999): 4978; 1959, 1968-69.

About the Author:

Sarah Wilson holds a PhD in English from Northwestern University. Her research focuses on the literature and culture of late-medieval England, with a particular emphasis on mourning and the philosophy of consolation. Sarah is also a Program Coordinator in the Department of Public Engagement at the Newberry.

Multilingualism in the British Isles and Writing in the Vernacular

Geoffrey Chaucer is often described as the “father of English literature” in part because of his decision to write his poetry in English, rather than French or Latin. This decision helped to start a broader trend towards writing in the vernacular and was followed by other writers and poets like Thomas Hoccleve, John Lydgate, and John Gower. Ranulf Higden’s Latin Polychronicon, also shown below, begins by reflecting upon multilingualism in the British Isles.

Death: The Great Equalizer

The Black Death caused a catastrophic loss of life in England and Europe and provoked reflections in works of art and architecture on the transience of life and inevitability of death.

Resistance, Revolt, and Dissent

The turbulence of late-Medieval England was the context for much dissent and resistance in social, political, and religious spheres, as can be seen in the documents below.

Further Reading

Boccaccio, Giovanni. “Prologue and First Book.” The Decameron. Trans. Richard Adlington. Westminster: The Folio Society, 1955.

Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Complete Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, ed. F.N. Robinson, 2nd ed. London: Oxford University Press, 1957.

Bailey, Mark. The Decline of Serfdom in Late Medieval England: From Bondage to Freedom; The Boydell Press: Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2014

Duffy, Eamon. The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, 1400-1580. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992.

Hoccleve, Thomas. The Regiment of Princes, ed. C.R. Blyth, METS. Kalamazoo, Michigan, 1999.

Horrox, Rosemary. The Black Death. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1994.

Justice, Steven. Writing and Rebellion: The Peasant’s Revolt in England. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

Related Sources:

Aberth, John, ed. The Black Death: The Great Mortality of 1348-1350: A Brief History with Documents. Boston: Bedford, St. Martin’s, 2005.

Byrne, Joseph P. Daily Life During The Black Death. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2006.

Goldberg, Jeremy. Medieval England: A Social History 1250-1550; Bloomsbury Academic: London, 2011.

Ormrod, Mark and Paul Lindley, The Black Death in England. Stamford: Paul Watkins, 1996.

Ruddick, A. English Identity and Political Culture in the Fourteenth Century; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2013; Vol. 93

Schofield, Phillip. Peasant and Community in Medieval England, 1200-1500; Palgrave-Macmillan: New York, 2003.

Strohm, Paul. Social Chaucer; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Mass, 1989.