Introduction

Having fun and enjoying “time off” is in our DNA, but how we spend our leisure time and seek entertainment has changed dramatically over the past century. Before the late nineteenth century, leisure and entertainment opportunities catered primarily to the affluent, who had both the income and lifestyle to partake in leisure activities. However, a cultural shift was on the horizon.

The early twentieth century was both an exciting and anxious time in the United States. The Industrial Revolution, the New Deal, and changes in labor laws, like the standardized work week, had a profound impact on US workers and leisure patterns in the early twentieth century. The workforce grew as city populations grew exponentially, with the influx of immigrants and the migration of African Americans during the Great Migration. A greater number of people had more time away from work and, for the first time, were able take part in leisure activities. People now had more free time for socializing and spending time with family, as well as resting from the hustle and bustle of life.

In addition to social and cultural changes, a growing and prospering middle class enjoyed innovations and technological advancements. For the first time, people now had more disposable income than their ancestors and found themselves eager to participate in and seek out more leisure activities. The upper class had both the time and money to indulge in the leisure activities that focused on prestige, such as charity balls. There was also a growing middle class that could enjoy time away from work and participate in social clubs and recreational activities. Although members of the middle and upper class were relishing their free time, this was not true for all, especially the working class that was still plagued by low wages and long hours. Many factory workers were still working a sixty-hour work week, and their leisure activities were limited to more local destinations and more affordable communal activities.

New forms of entertainment were heavily publicized and sought out. Both the 1893 and 1933 World’s Fairs brought new ideas and technology that were designed to improve daily life. Newspapers and advertisements of coming attractions encouraged people of all social classes to seek out new entertainment opportunities near and far. Greater mobility, transportation, and the creation of new roads and highways not only made it easier to travel to but also served as the locations for new leisure and entertainment activities. New highways, railroads, and trolley lines allowed people to escape the congestion or modernity of their daily life or hometown.

Amusement parks, circuses, and zoos are just three of the many casual leisure options that offered collective experiences to a greater public in this new era. These communal activities were the great equalizer, enjoyed by all socio-economic levels. The following documents explore the various types of leisure and entertainment activities that were shaped by advances in technology, mobility, and population growth.

Please consider the following questions as you review the documents:

- In your own life, how have advancements in technology effected the types of leisure and entertainment activities you enjoy?

- What influence did transportation have on leisure opportunities in the early twentieth century?

- Why would population growth have an impact on how people wanted to spend their free time?

- What types of publicity were used to promote amusement parks, circuses, and zoos? Would they attract the same visitors?

- What effect did a change in leisure patterns have on employment opportunities?

Buckle Up and Enjoy the Ride

In the early twentieth century, technological advances, especially the availability of electricity, influenced the type of leisure activities that were available. Amusement parks benefited from this increased availability.

The amusement park’s evolution can be traced back to Europe and the traveling fair pleasure gardens. In the United States, amusement parks evolved from Europe’s traveling fair and pleasure gardens. Early amusement parks were not “theme” oriented, as we often see today. These early parks focused on rides, shows, and concessions. These three aspects of the amusement park can all be traced back to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. The Exposition brought visitors from around the world to Chicago and the Midway provided the sights, smells, rides, and sounds of what we think of when we think of the amusement park of today.

In the early twentieth century, Chicago was a leader in the amusement park industry, boasting several parks throughout the city. The Ferris wheel that was first introduced at the Exposition was located in Lincoln Park from 1896-1903. On the South Side, there was White City in Woodlawn, and on the North side, Luna Park. Although these amusement parks were open to the public, they were not always welcome to all visitors, including African Americans. Recognizing larger amusement parks were racially segregated, South Side Chicago attorney Augustus L. Williams, Virgil Williams, editor Robert S. Abbott, and Broad Ax newspaper editor Julius Taylor established the first Black-owned and -operated amusement park, Joyland Park, in 1923. Located at 33rd and Wabash, the park offered African Americans the amusement park experience with rides, shows, and games in the rapidly growing Bronzeville neighborhood.

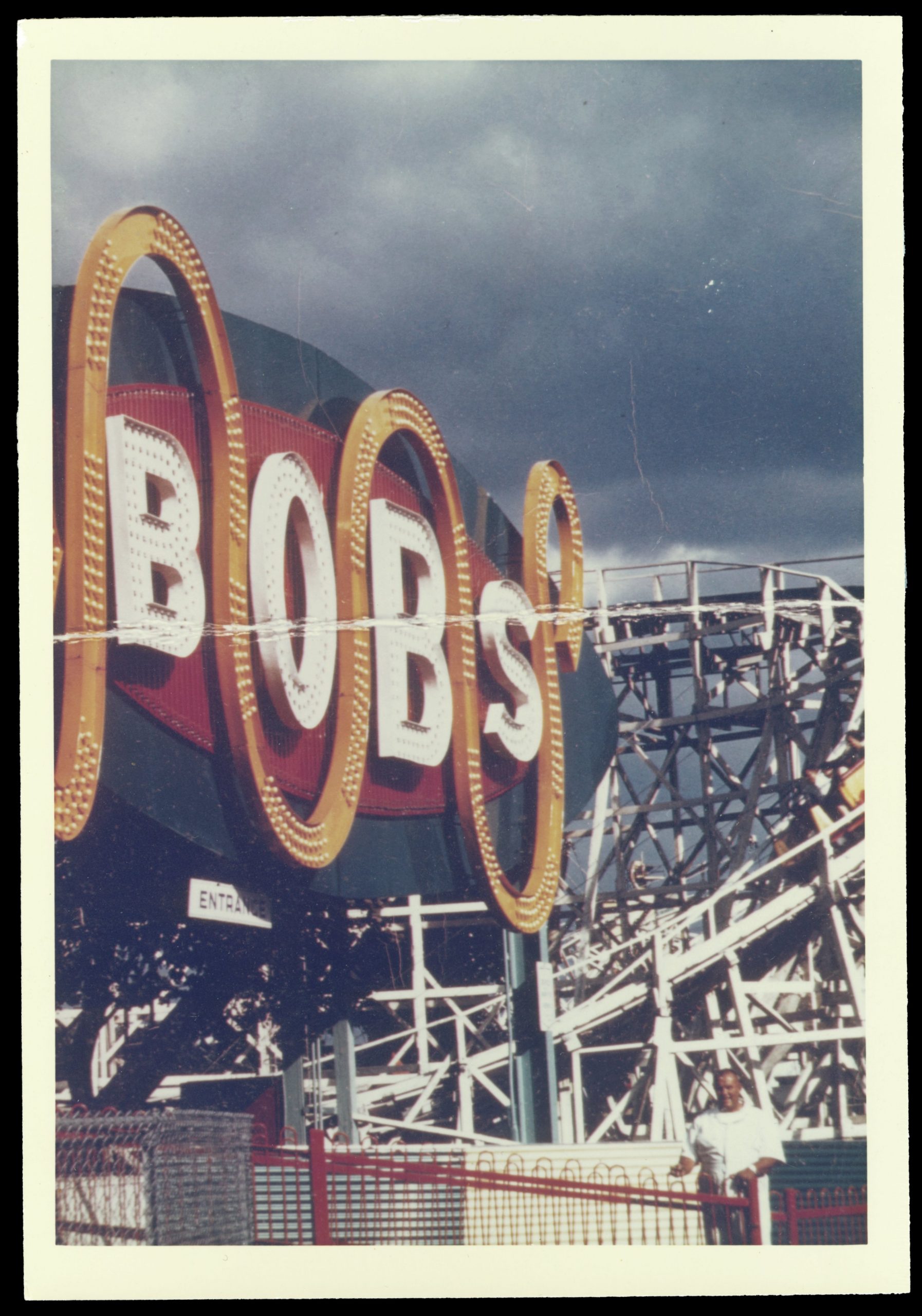

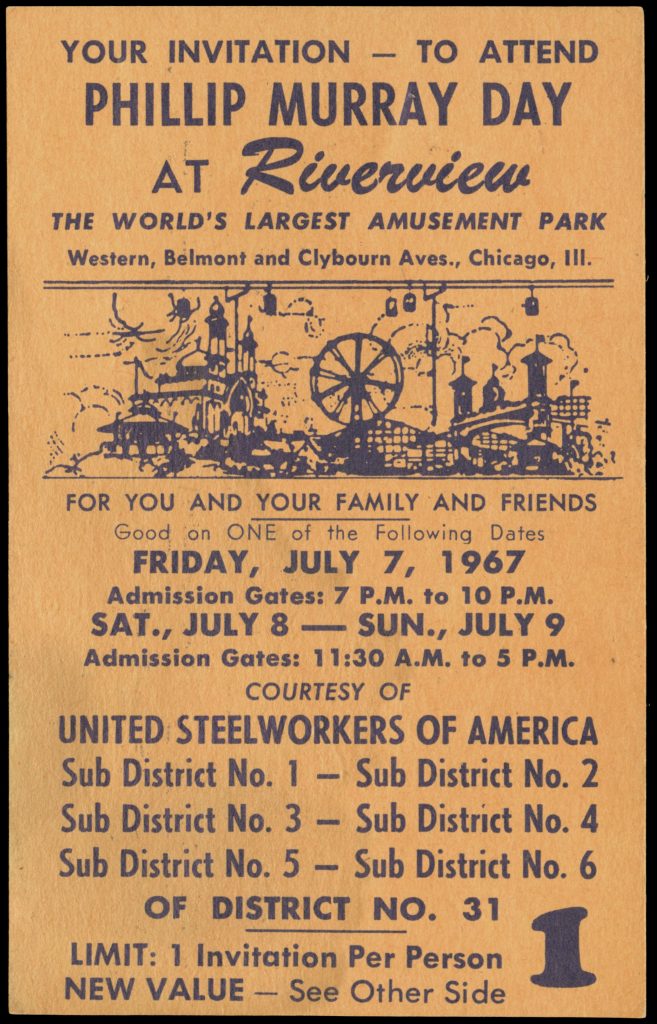

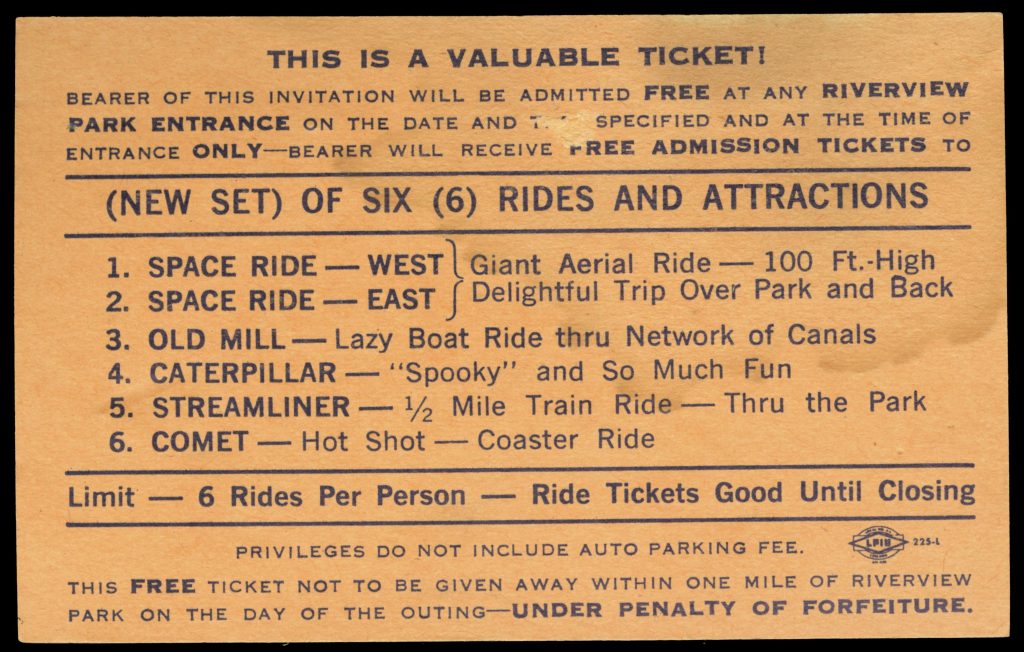

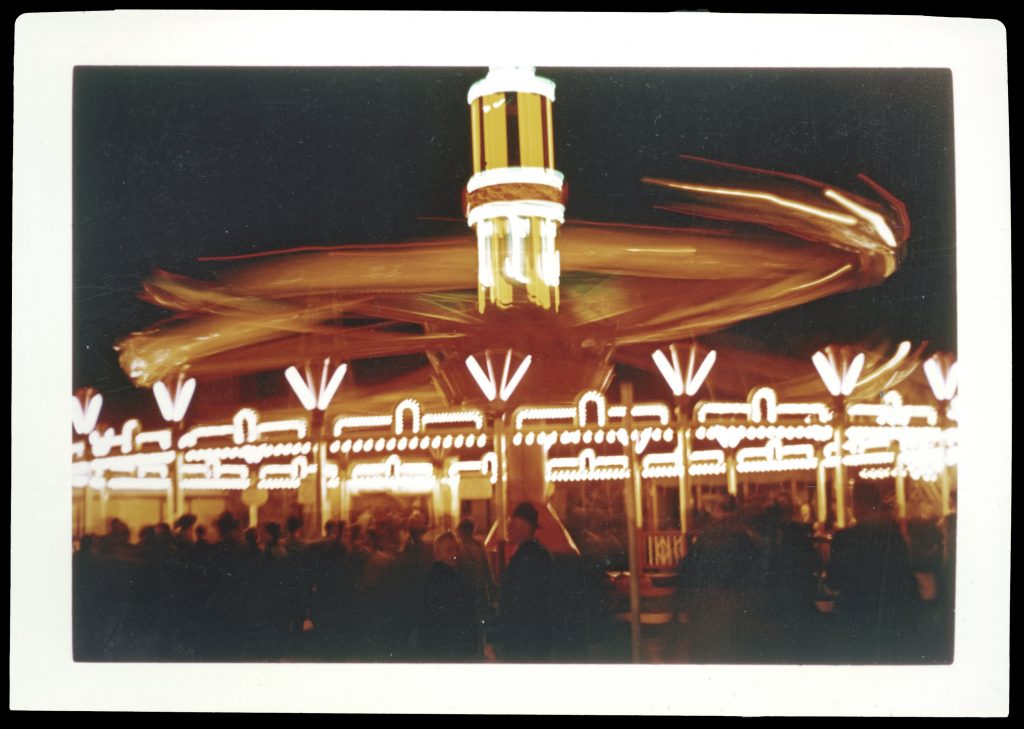

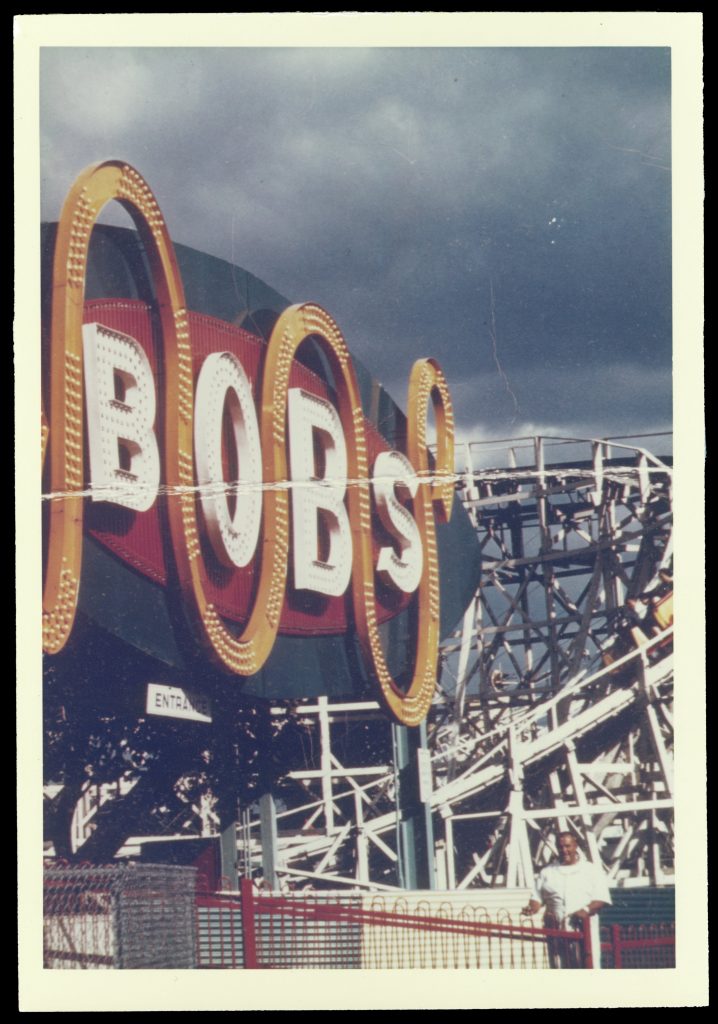

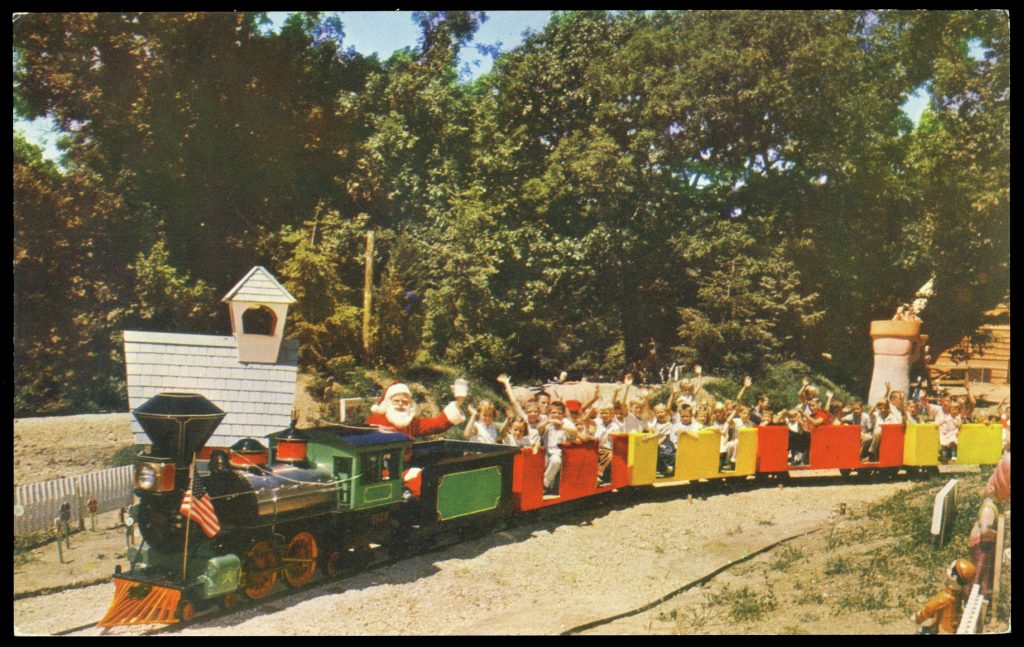

One of the most famous and largest amusement parks in the city was Riverview, located on the North Side of the city at the intersections of Roscoe, Belmont, and Western Avenues. Opened in 1904, it was once known as Sharpshooter Park, used by veterans of the Franco-Prussian war for rifle practice range. [1] It then slowly developed from picnic grounds to a six-acre park with three rides and eventually 140 acres with 100 rides becoming one of Chicago’s largest and longest running amusement parks. The park was one of the first to combine nature with rides. Advancements in technology offered new and exciting attractions including the first suspended roller coaster in 1908 and the parachute ride in 1936. The Rotor ride used centrifugal force, so that riders would stick to the wall as the floor beneath them dropped. One of the most famous attractions at the park was the “Bobs” wooden rollercoaster. Electricity not only added to the types of rides and activities offered at the park, it also allowed the coaster to operate well into the evening hours, offering brightly lit rides that pierced the night sky. To keep the crowds thrilled and returning, Riverview would host various groups and theme days, like the 1967 United Steel Workers “Phillip Murray Day,” and introduced a new ride each year. But this was not enough to keep the park open. The development of the national highway system had a deep impact on suburban sprawl and the ability to travel beyond the city limits for new adventures. The newly completed Northwest Tollway offered access to theme parks that began to pop up in outlying areas, such as Santa’s Village in East Dundee, Illinois. After its sixty-fourth season, Riverview closed its doors for good.

Selections: Riverview Park tickets, mid-20th century

Questions:

- Why do you think the availability of electricity was a major factor in the development of the amusement park?

- What impact do you think Joyland Park had on the Bronzeville neighborhood?

- How are the amusement and theme parks of today similar or different than Riverview?

- If you could create your own amusement park, what would be its feature attraction? How would you promote the park?

- Mini trains were attractions at both Riverview and Santa’s Village. Why were trains so appealing, then and now?

Step Right Up….

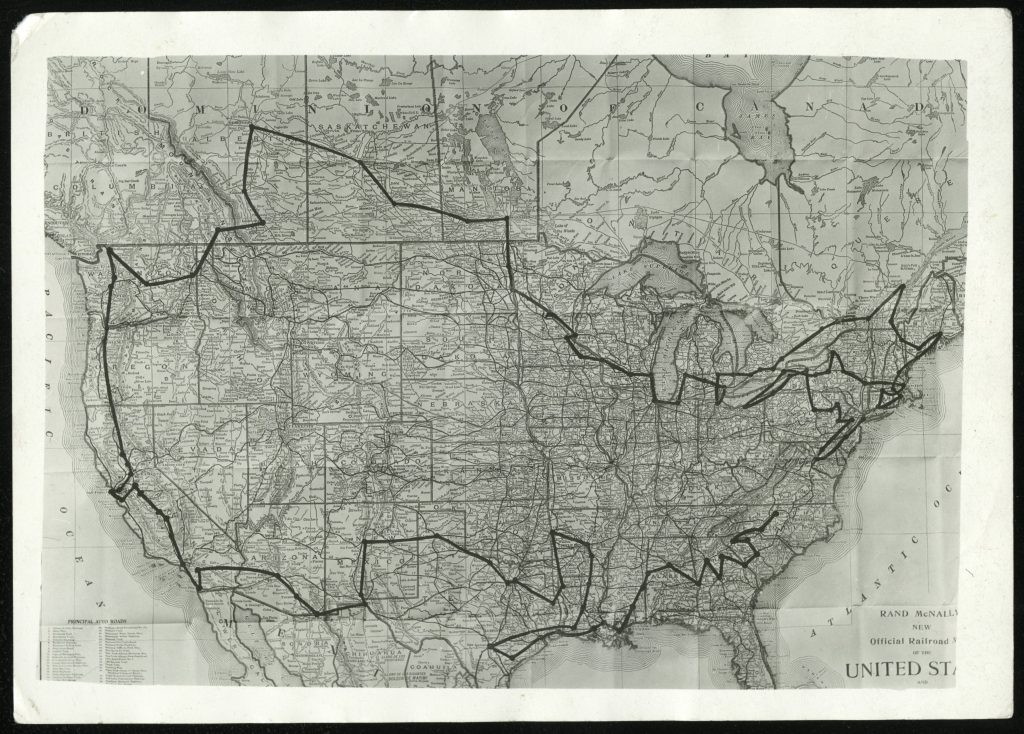

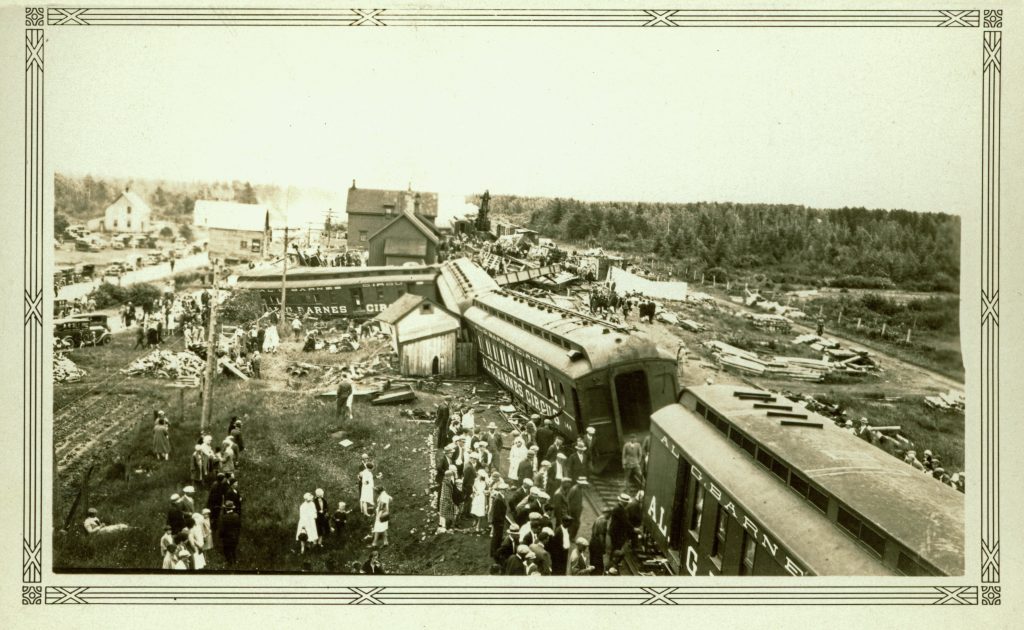

Although not an American creation, the circus as we know it today is steeped in the American tradition, offering a bit of vaudeville, athleticism, and imagination. P.T. Barnum and James A. Bailey popularized the expression, “The greatest show on earth,” to describe the American circus. An important contribution to the success of the circus entertainment industry was the railroad. With the improvement in rail service in the late nineteenth century, this was the means of transport for almost all circuses large and small. As transportation options moved from wagon to rail, the American circus brought entertainment to the masses and could reach new audiences far beyond the major cities. Travel by rail also offered a schedule, with set dates and locations making stops at towns that dotted the rail line. Circuses would travel and perform throughout the country as illustrated on this map of the 1930 tenting season of the Ringling Brother Barnum and Baily Circus. Circuses traveled at night, enabling them to arrive early in the morning at their destination. Although traveling by rail was more efficient and allowed the circus to perform an extensive number of dates, train wrecks were not uncommon, as exemplified by the aftermath of the Al G. Barnes train that derailed on July 20, 1930 on their way from Newcastle to Charlottetown.

Circuses were competitive. The circus’ “advance” man or team was sent ahead of the circus to publicize and drum up business in town to ensure a full house. Colorful show bills and heralds (similar to posters) placed strategically along the circus route and in town would broadcast the circus’ arrival. Many print shops catered exclusively to circuses producing posters as well as their programs, route cards, and other transitory documents meant to be thrown away after one use, called “ephemera” by scholars. Posters like this one promoting the Cristiani Wallace Circus were placed on barns and farm wagons. The printing industry and the circus have a long history, many printing firms can trace their early beginnings to creating ephemera for the circus industry.

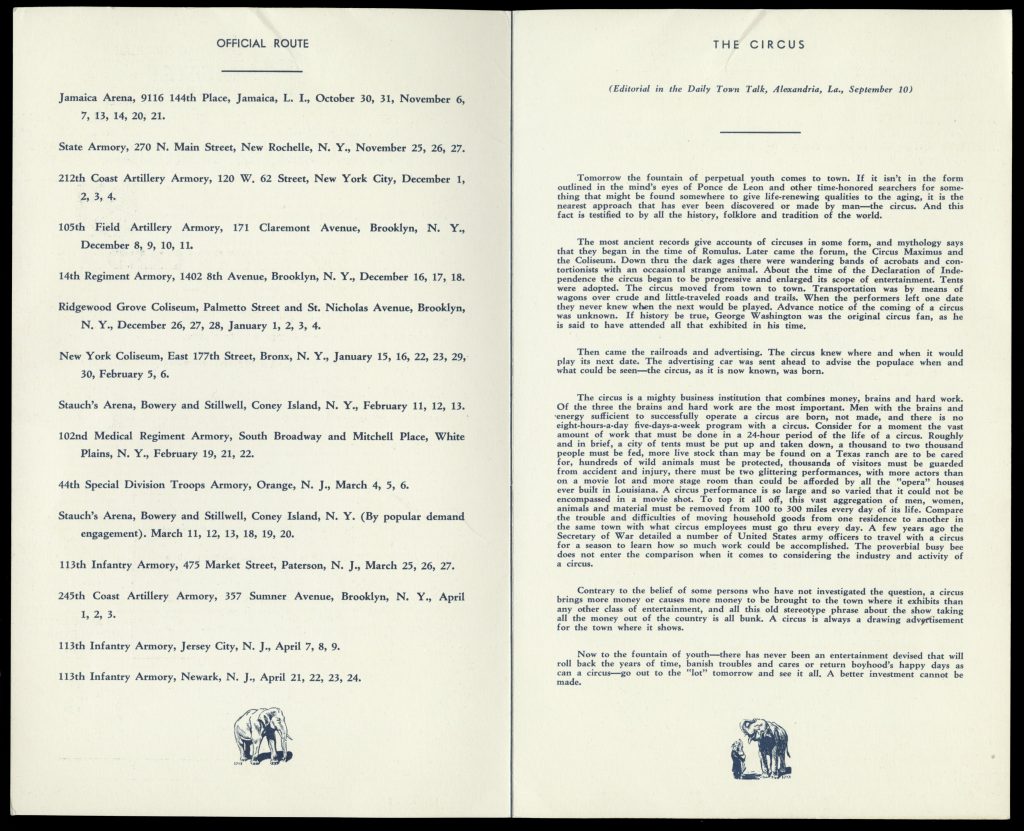

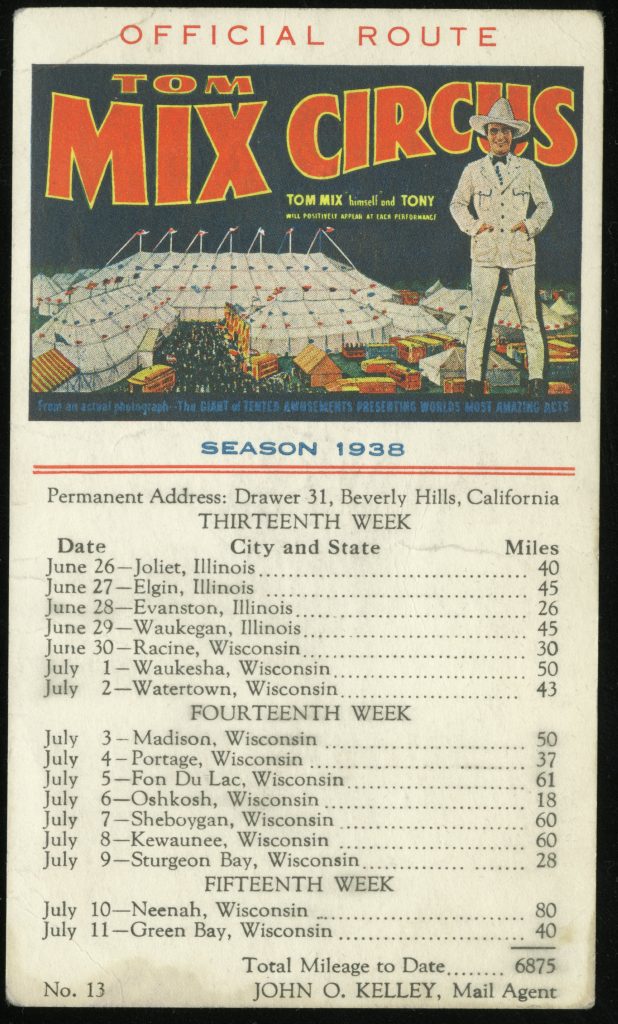

The individual route of a circus determined its financial success. Route cards were miniature ad campaigns for the circus, fostering excitement and anticipation in towns they were to perform. To promote their arrival, circuses published touring schedules by distributing route cards that listed the dates and location of each performance. Many times, performing only one night (or in circus lingo, “stand”), at any given location, as shown on the Tom Mix Circus route card pictured in the Introduction. The circus traveled more than 6,000 miles, during their 1938 season.

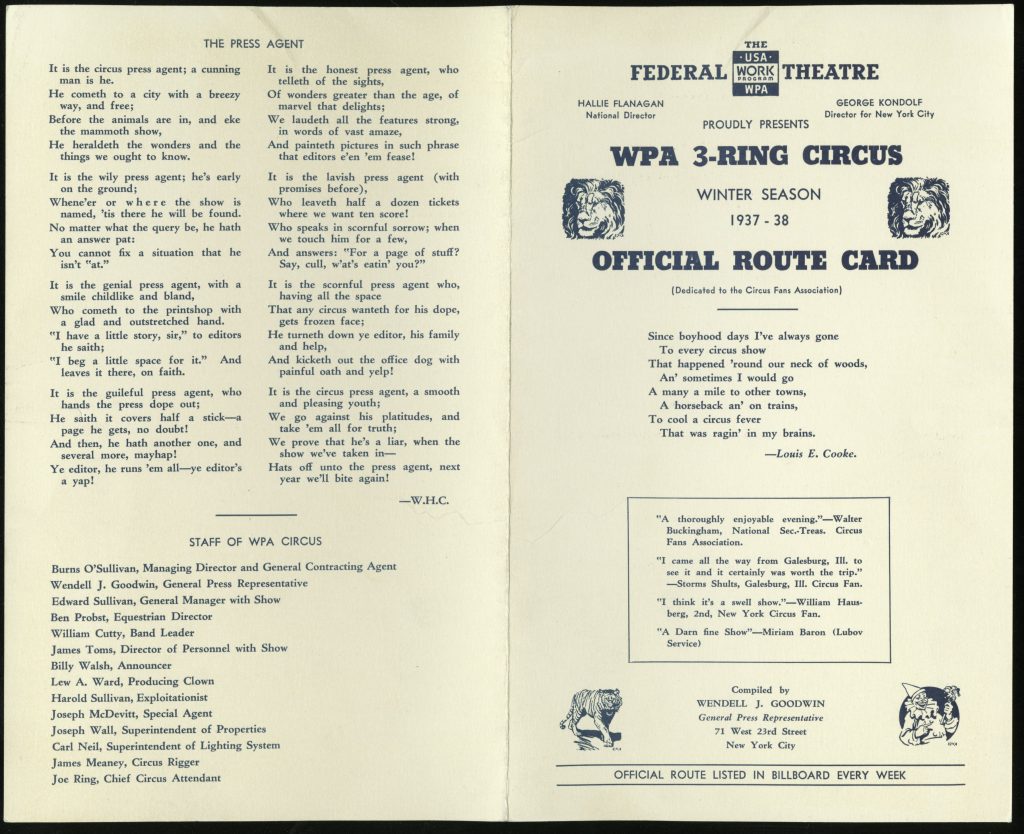

Selection: WPA route card, 1937-1938

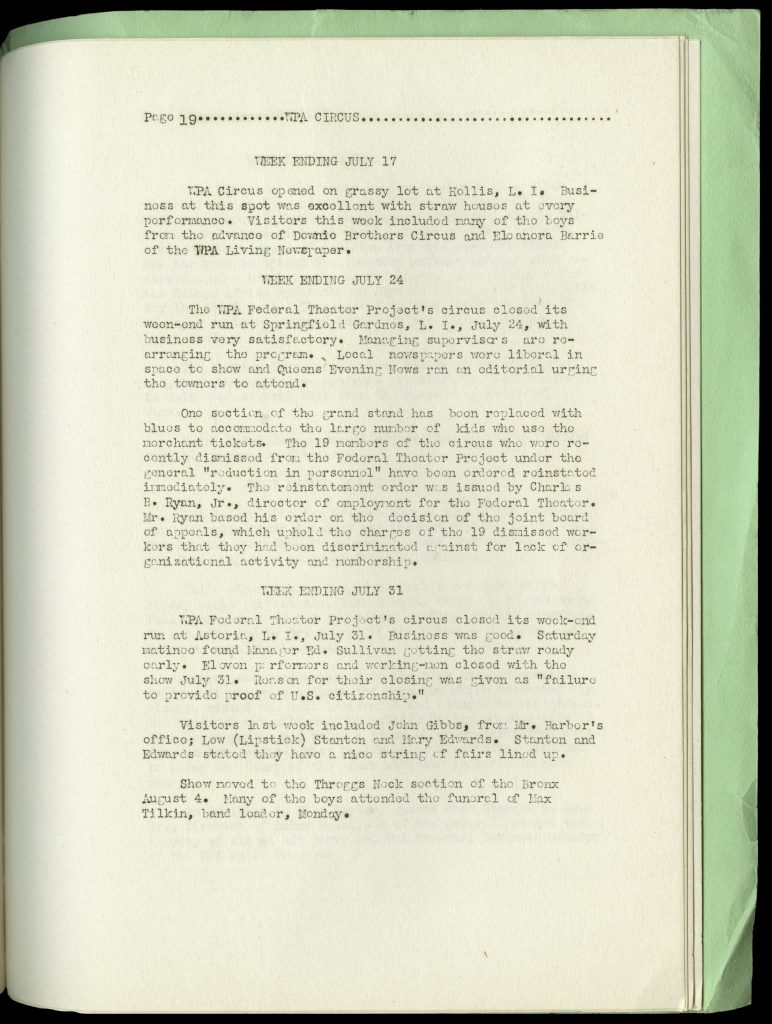

In addition to the route card, at the height of the tented circus in the early twentieth century, many circuses produced a route book, like a diary, at the season’s end. It listed performance dates and performers. The official route book of the 1937 tenting season of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) Circus Federal Theater Project included reviews of shows. During the Depression, circuses faced the same declines in attendance and job loss as in other industries. The WPA, later called the Works Project Administration, was part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. The goal of the WPA was to employ most of the unemployed people until the economy recovered. Federal Project Number One is the collective name for a group of projects under the WPA that employed writers, musicians, artists, and actors; this group included out-of-work circus performers. The Circus Unit was part of the larger Variety Unit of the Federal Theater Project, employing as many as 250 performers in sixty acts.

Selection: WPA circus route book, 1937-1938

Questions:

- Looking at the Tom Mix route card, in how many towns did the circus perform? How many weeks were they on the road?

- Why would a Works Progress Administration circus be created? Why was the route book important?

- The Cristiani Wallace Circus poster would have been used to promote circus attractions. Can you think of someone or something we use today for promotion?

- Why do you think traveling by train was the most efficient way for the circus to move around the country?

- Is the circus still relevant today? Why or why not?

Lions and Tigers and Bears, Oh My!

The modern zoo that can be found in most major cities today is more than a tourist attraction and is seen as a source of education, conservation, and scientific research. However, while early zoos were a common feature in major cities, most had limited space for expansion. Chicago’s Lincoln Park Zoo, one of the earliest zoos in the United States, was established in 1868 with the donation of a pair of swans from the menagerie in New York’s Central Park. In the years that followed, Lincoln Park Zoo grew in both exhibits and attendance. However, the zoo’s expansion was limited and had already found itself land-locked by 1909, as recognized by city planner Daniel H. Burnham. He saw the need for a zoological park appropriate for the size and importance of Chicago, but there was no room for the zoo to expand beyond its designated space within Lincoln Park.

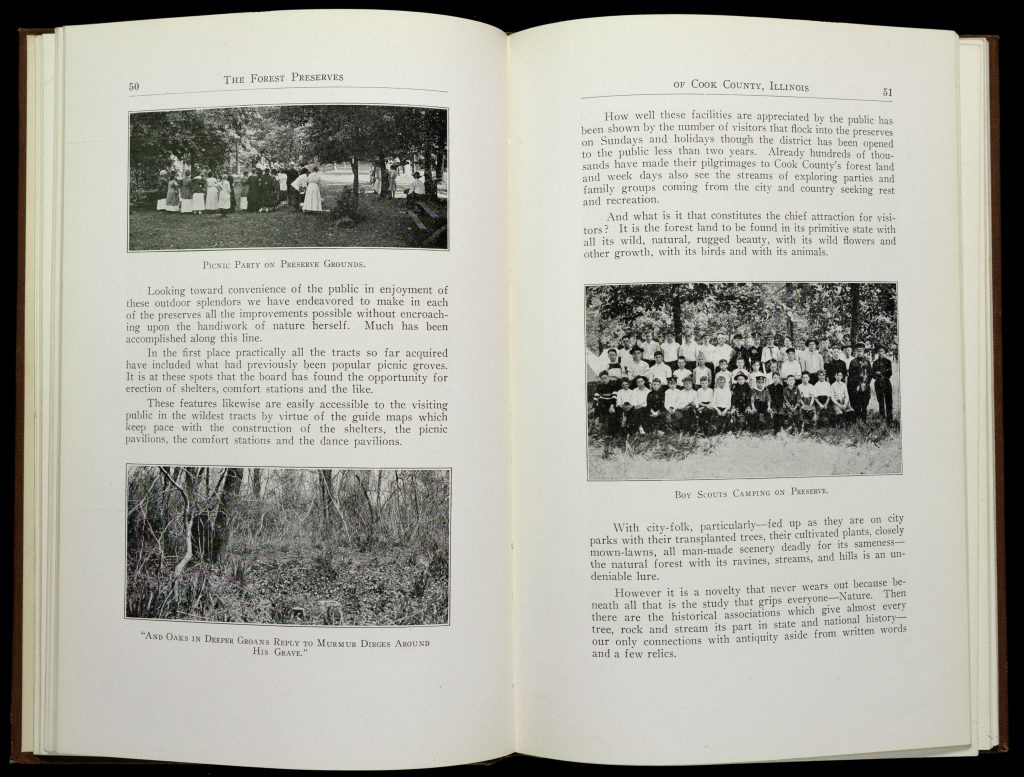

The Brookfield Zoo, just fourteen miles from the city, is a feature attraction of the Cook County Forest Preserve system, one of the most extensive systems near a large metropolitan city. In the early twentieth century, the need for outdoor space in urban areas intensified and became much more of a necessity than ever before. As population and industry flourished in cities, the need for more space and fresh air became paramount in urban areas. Forest preserves offered an oasis away from the steel and concrete of the city. Unlike city parks, which had “transplanted trees” as noted in a history of Cook County Forest Preserves,[2] these natural open spaces were leafy green retreats that offered miles of paths and trails waiting to be explored. At the turn of the twentieth century, just as the National Park System was taking shape, community leaders saw the need to create public land around the core of the city.

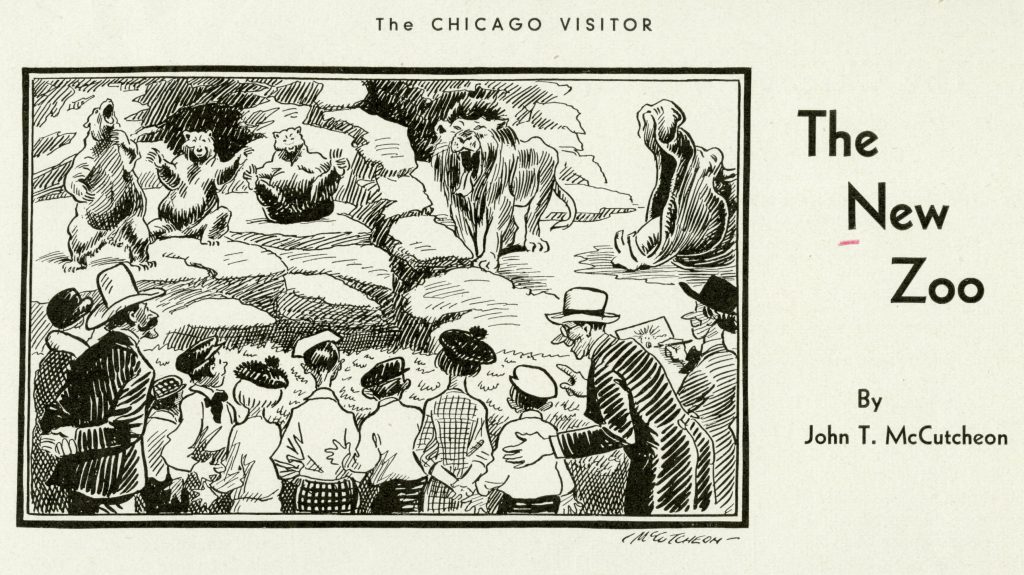

Nestled within a forest preserve, the Brookfield Zoo set out to open as the first zoo in America with bar-less exhibits. The concept of the bar-less zoo had been steadily growing and stems from early European zoos, in which animals were shown in their in their natural environments. Unlike restrictive cages, the animal enclosures were spacious and use moats and other natural features such as rocks and trees to provide a suitable environment emulating the animal’s natural habitat. Expansive dry moats in the front offered safety between visitor and animal as illustrated in the cartoon titled “The New Zoo.”

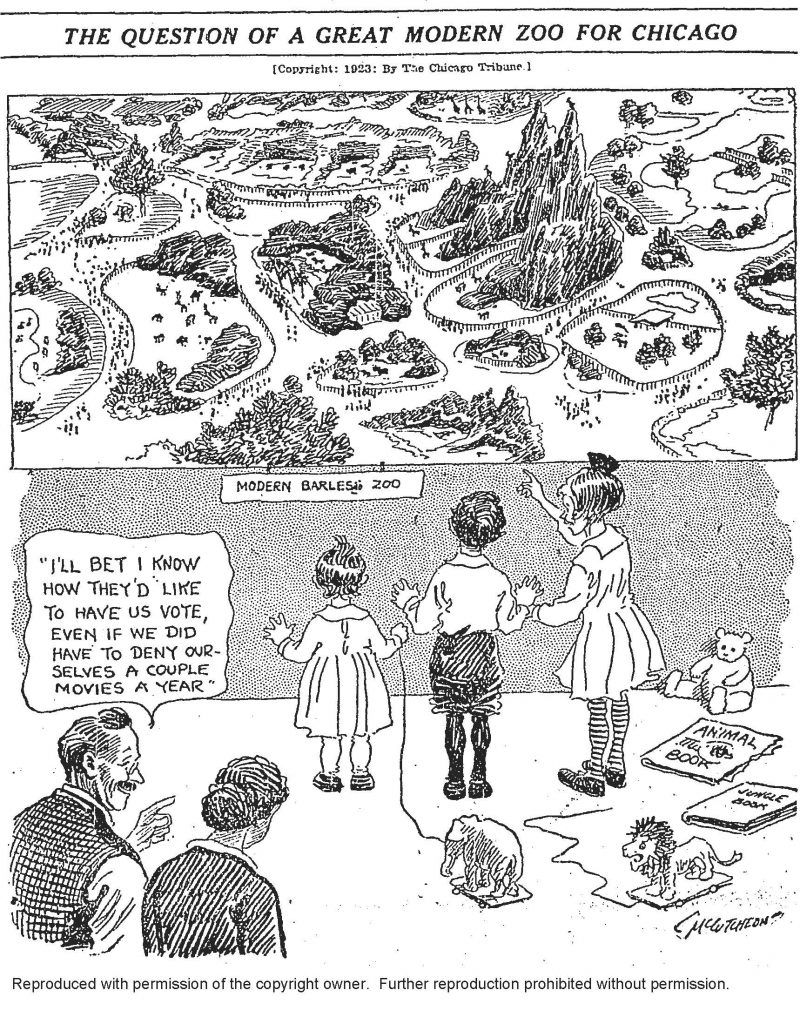

In 1920, Edith Rockefeller McCormick offered several acres of land to the Cook County forest preserve district on the conditions that they be used for a zoological park and the commissioners assume the back taxes. They accepted and felt the best way to carry out their vision and oversight of the Brookfield Zoo was to create a citizens’ committee, which should operate by the approval of the commissioners. Thus, the Chicago Zoological Society was incorporated and chose Chicago journalist and cartoonist John T. McCutcheon to be president. With Midwest roots in Indiana, his popular cartoons were a perfect fit for promoting and popularizing the zoo with general audiences. His drawings depicted both the celebrations and challenges of the zoo, including the struggle to convince county residents to approve a zoo tax. McCutcheon’s 1923 cartoon illustrates the doubts felt by many citizens to use tax dollars to fund the zoo Tax dollars were vital in the establishment of the zoo, but even with the urging and support from some of Chicago’s most prominent citizens, including social reformer Jane Addams, the vote was not unanimous, and the first referendum to fund the zoo was not approved.

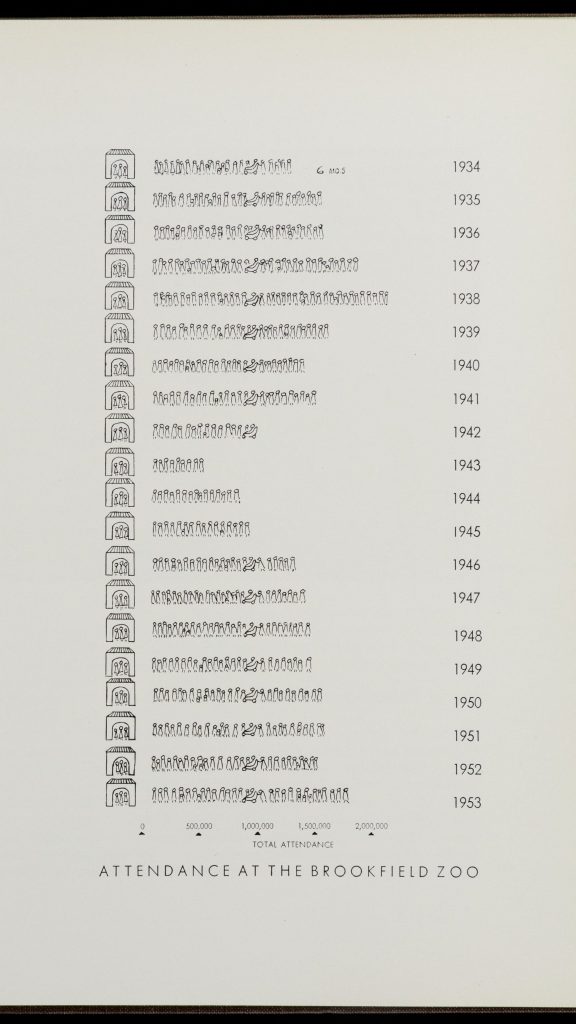

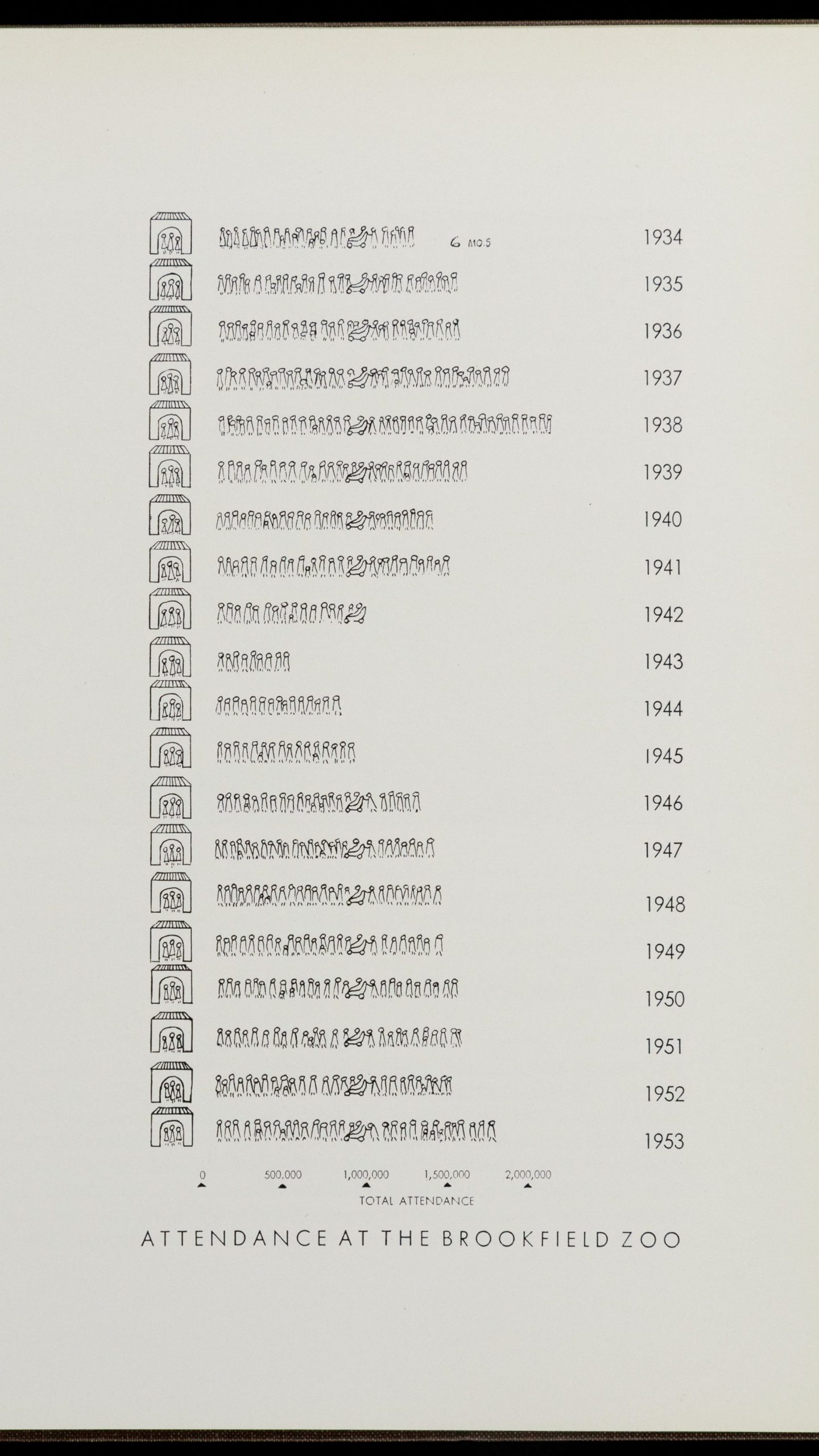

With the approval of the project by the second referendum, Cook County officials broke ground in 1926, in anticipation of being open by the 1933 World’s Fair. McCutcheon’s cartoon of permanent exhibits exemplifies the status of the Zoo’s position amongst Chicago’s most prestigious museums and cultural attractions. To meet the World’s Fair deadline, laborers from the Civil Works Administration, a precursor to the Works Progress Administration, were employed to finish structures, paint exteriors, and construct habitats, but even through their efforts, the zoo’s opening was delayed due to the Great Depression. Finally, on June 30, 1934, 2,000 invited guests from all over the Midwest came to celebrate the zoo’s official opening. The next day, the Chicago Tribune published an article providing directions for visitors, noting that the Zoo is served by highways, a railroad, a streetcar line, and elevated line. Roads leading to the zoo were congested with more than 58,000 visitors clamoring to be part of the Zoo’s opening day. Just a couple months after its opening day, visitor totals surpassed one million and in the coming decades, the zoo expanded both in size and exhibitions, drawing visitors from around the world.

Questions:

- Why is green space important to a city? How are cities incorporating open space in development of urban areas and planning?

- What are the differences between a park and a forest preserve? What are the similarities?

- Looking at the Brookfield Zoo attendance chart, what factors would have caused a decrease in visitors between 1941 and 1945? Would these same factors cause a decline in visits to other forest preserves and parks?

- Why would the commissioners want the zoo to be open by the World’s Fair in 1933?

- Cartoons were used to promote and express challenges in the creation of the zoo. Are cartoons still a relevant tool to express opinions?

[1] Haugh, D. Riverview Amusement Park. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Pub., 2004.

[2] Anon. The Forest Preserves of Cook County: Owned by the Forest Preserve District of Cook County in the State of Illinois. Chicago: Clohesey & Co., printers, 1918.

About the Author

Jo Ellen McKillop Dickie is the Reference Services Librarian and the Selector for Reference in the Newberry Library’s Collection Development Department.

Amusement Parks

See below for pictures of and writings about early and mid-twentieth century amusement parks.

Circuses

Improvements to the railroads were important for the success of the circus industry, which became famous in America as “the greatest show on earth.”

Zoos

The zoo was another prominent space in which people of all socioeconomic classes spent their leisure time in the early and mid-twentieth century.

Further Reading

American Circus Collection, Newberry Library ,Chicago.

Burnham, Daniel Hudson, Edward H. Bennett, and Charles Moore. Plan of Chicago .Centennial ed. Chicago, Ill: Great Books Foundation, 2010. Print.

Deuchler, Douglas., and Carla W. Owens. Brookfield Zoo and the Chicago Zoological Society . Charleston, S.C: Arcadia Pub., 2009. Print.

Dolores Haugh Riverview Amusement Park Collection, The Newberry Library, Chicago.

Flint, Richard W., “A Great Industrial Art: Circus Posters, Business Risks, and the Origins of Color Letterpress Printing in America”, Printing History, Vol. 25 no.2, New York: American Printing History Association, 2008. pp.18-43. Print.

The Forest Preserves of Cook County : Owned by the Forest Preserve District of Cook County in the State of Illinois. Chicago: Clohesey & Co., printers], 1918. Print.

Grossman, James R., Ann Durkin. Keating, and Janice L. Reiff. The Encyclopedia of Chicago . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004. Print.

Haugh, Dolores. Riverview Amusement Park . Charleston, SC: Arcadia Pub., 2004. Print.

Holabird, Christopher. The Brookfield Zoo, 1934-1954. Brookfield, Ill: N.p., 1954. Print.

John T. McCutcheon Papers, The Newberry Library, Chicago.

Mangels, William F. The Outdoor Amusement Industry : from Earliest Times to the Present . New York: Vantage Press, 1952. Print.

McCutcheon, John T. Drawn from Memory . Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1950. Print.

Ogden, Tom. Two Hundred Years of the American Circus : from Aba-Daba to the Zoppe-Zavatta Troupe . New York: Facts on File, 1993. Print

Pond, Irving K. (Irving Kane) et al. The Autobiography of Irving K. Pond : the Sons of Mary and Elihu . Oak Park, IL: Hyoogen Press, 2009. Print.

Wlodarczyk, Chuck. Riverview, Gone but Not Forgotten : a Photohistory, 1904-1967 . Chicago: Riverview Publications, 1977. Print.

Wenz, Phillip L., and Rich Juvinall. Santa’s Village . Charleston, SC: Arcadia Pub., 2007. Print.