Curriculum Connection: American Imperialism, Monroe Doctrine, Spanish American War, Monroe Doctrine, Women in the Military, Women’s History

From the Amy Elanor Wingreen Papers at the Newberry Library.

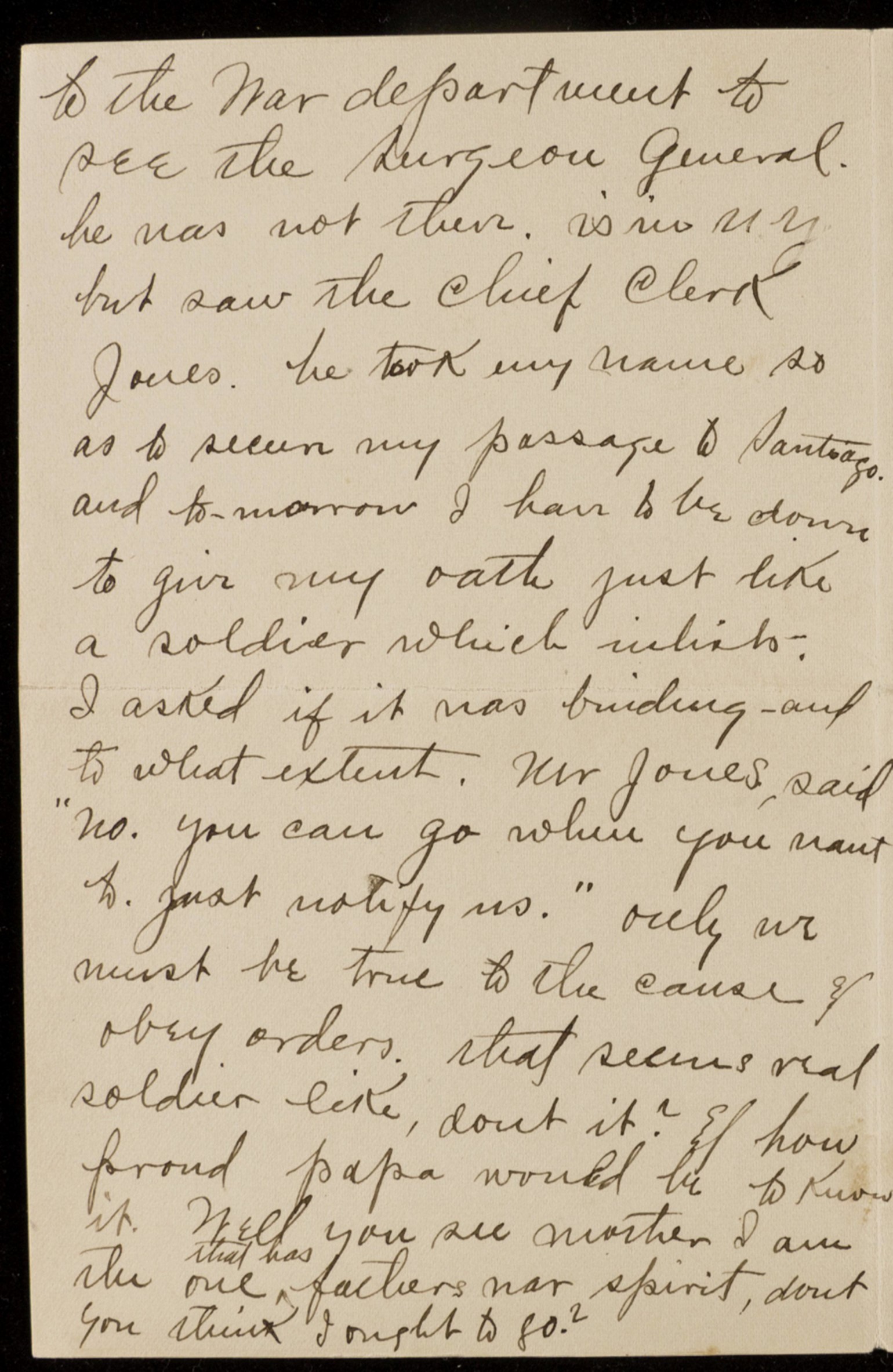

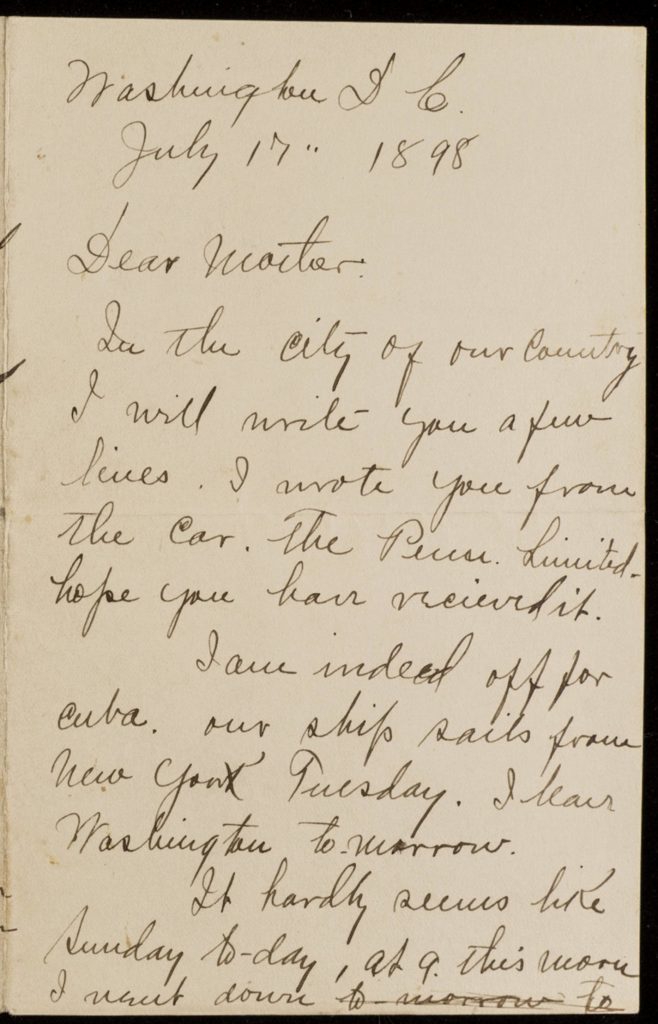

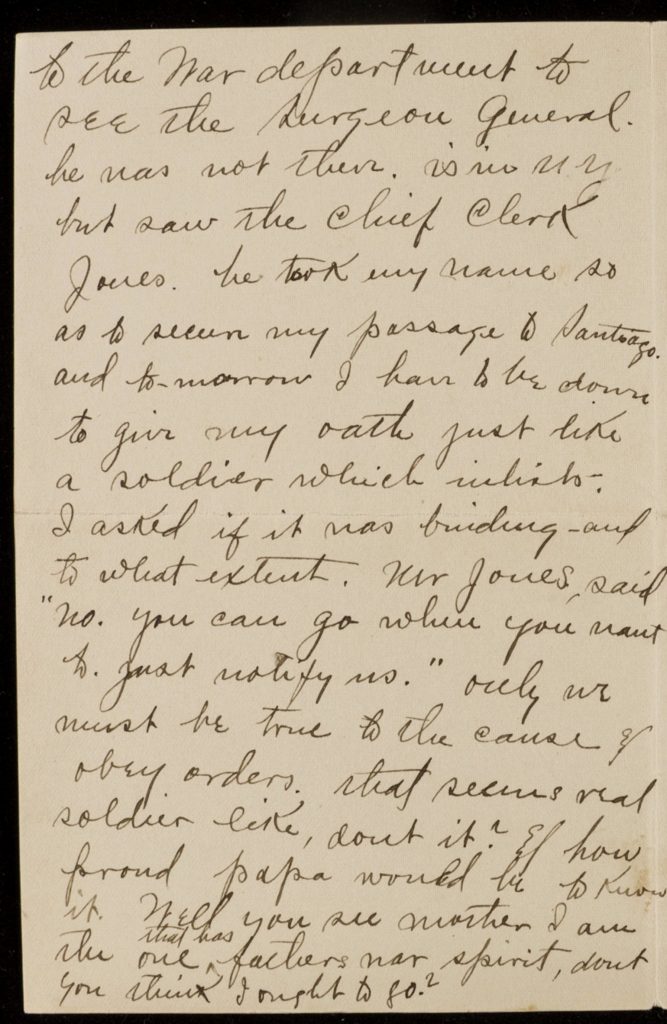

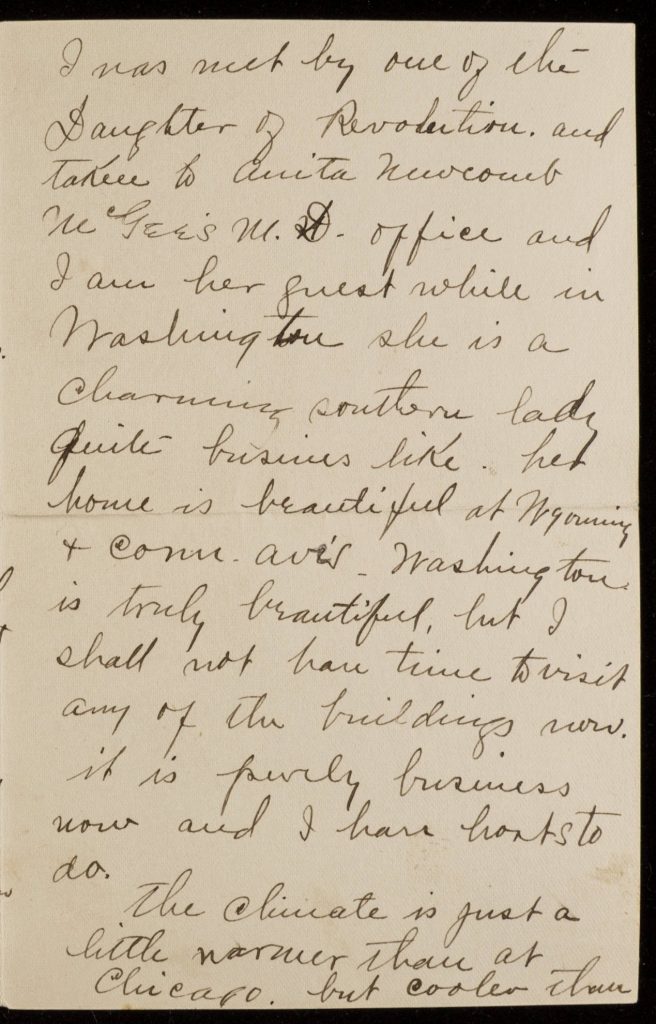

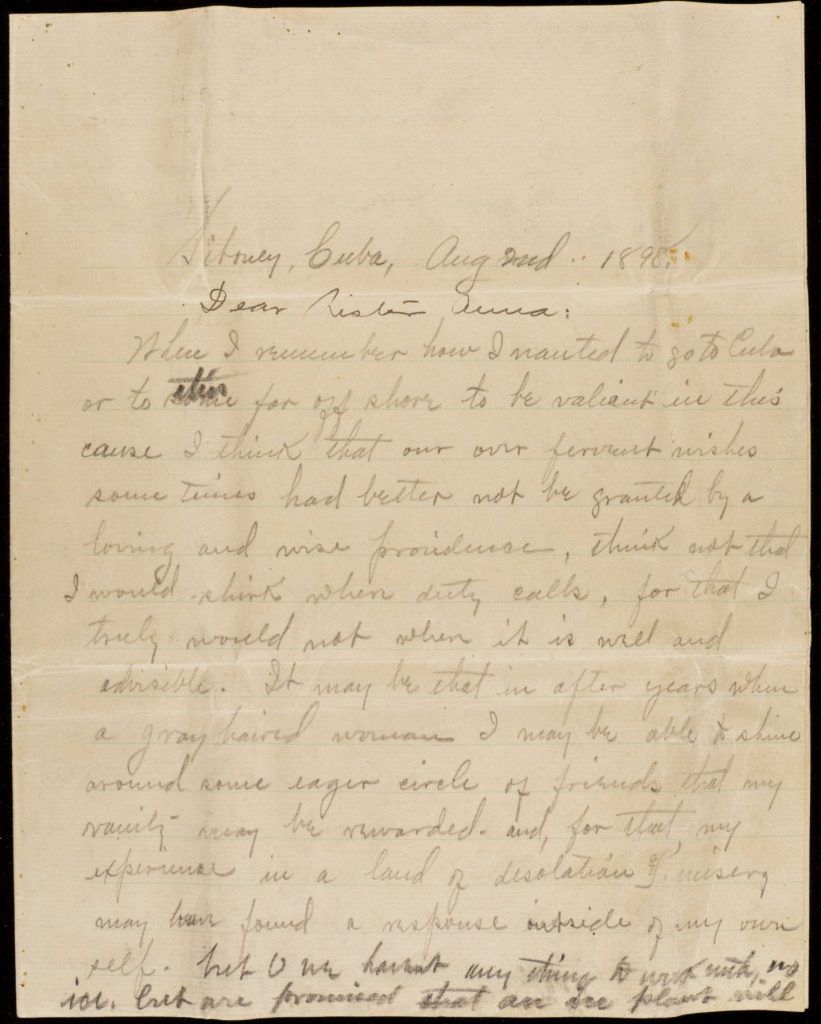

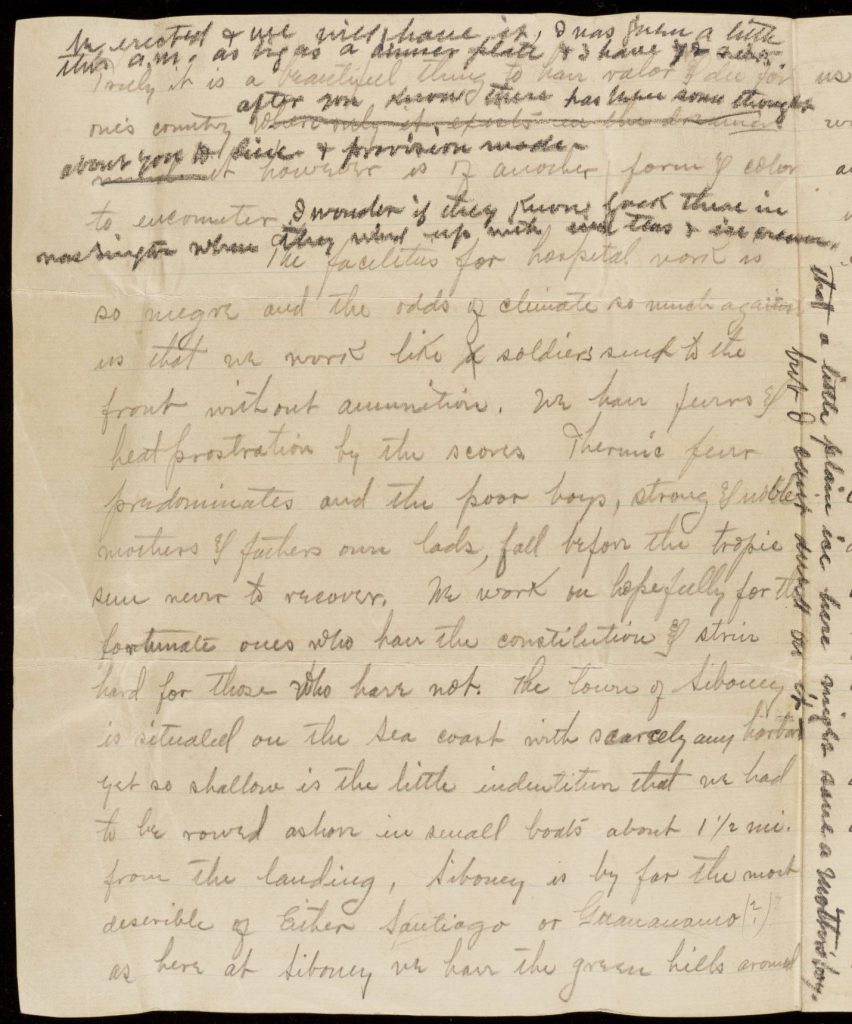

You and your students are going to read two excerpts from the letters of Amy Eleanor Wingreen. Explain to students that the typed excerpts are transcriptions of parts of handwritten letters. They can see images of the original letters below the transcriptions. You may want to review the Skills Lesson: Reading a Transcription.

This lesson is for a teacher-controlled class. If you would like your students to work with the source independently or in small groups, you can download the student worksheet in the Student Worksheet tab and transcripts and images of the sources in the Downloads tab.

With more advanced students, present the excerpts without any background and allow students to discover everything they can from the primary source and, possibly, their own research. For less advanced students, share the background material.

Process

Read the excerpts individually.

Letter of July 17, 1898

Excerpt Transcript

Washington, D. C.

July 17” 1898

Dear Mother:

In the City of our Country.

I will write you a few lines. I wrote you from the car, the Penn Limited, hope you have recieved [sic] it.

I am indeed off for Cuba. Our ship sails from New York Tuesday. I leave Washington tomorrow.

It hardly seems like Sunday to-day. At 9, this morn I went down to the War department to see the Surgeon General. He was not there, is in NY, but saw the Chief Clerk Jones. he took my name so as to secure my passage to Santiago, and to-morrow I have to be down to give my oath just like a soldier which enlists. I asked if it was binding—and to what extent. Mr Jones said “No. You can go where you want to. Just notify us.” Only we must be true to the cause & obey orders. That seems real soldier like, don’t it? & how proud papa would be to know it. Well you see mother I am the one that has fathers war spirit, don’t you think I ought to go?

I was met by one of the Daughter of Revolution. And taken to Anita Newcomb McGee’s M.D. office and I am her guest while in Washington she is a charming southern lady quite business like. her home is beautiful at Wyoming and Conn. Ave’s. Washington is truly beautiful, but I shall not have time to visit any of the buildings now. it is purely business now and I have lots [?] to do. . . .

After the first excerpt, ask students to tell you everything they can about the writer of the letters, Amy Wingreen, and what she is doing at the time she wrote them. If you need to prompt them, ask simple questions, such as “Where is she?” “Is that where she lives?” “Why is she there?” “How does she feel?” When the information requires an inference, ask students to explain how they made it.

For example, a student might say, “She’s a nurse.” The answer to “Why do you think so?” might be, “She goes to see the Surgeon General. And then she goes to an ‘M.D. office.’ I think that must be a doctor’s office. And besides, women couldn’t be soldiers then and she says she’s going to ‘give my oath just like a soldier.’ So, I think the only thing she could be doing is nursing.”

Letter of August 2, 1898

Excerpt Transcription

Siboney, Cuba, Aug 2nd 1898

Dear Sister Anna:

When I remember how I wanted to go to Cuba or to this far off shore to be valiant in this cause I think that our own fervent wishes some times had better not be granted by a loving and wise providence. Think not that I would shirk when duty calls, for that I truly would not when it is well and advisable. It may be that in after years when a gray-haired woman I may be able to shine around some eager circle of friends that my vanity may be rewarded. And, for that, my experience in a land of desolation [?] may have found a response in pride of my own self. But O we haven’t any thing to work with, no ice, but are promised that an ice plant will be created & we will have it. I was given a little this a.m., as big as a dinner plate, and I have [?]. Truly it is a beautiful thing to have valor and die for one’s county after you know there has [?] some thought about you to live & provision made. I wonder if they know back there in Washington where they wind up with [?] that a little plain ice here might save a mother’s boy, but I can’t dwell on it–

The facilities for hospital work is so meager and the odds of climate so much against us that we work like soldiers sent to the front without ammunition. We have fevers and heat prostration by the scores. Thermic fever predominates and the poor boys, strong & noble mothers & fathers own lads, fall before the tropic sun never to recover. We work so hopefully for the fortunate ones who have the constitution & strive hard for those who have not.

After the second excerpt, repeat the process of asking for all the information students can find in the source. Have them describe the obstacles Amy Wingreen faces. Then discuss the differences between the two excerpts. Ask students to focus on the feelings Amy expresses in each of the two letters. Ask about differences in the way the letters look. Then discuss how Amy’s thoughts and feelings change between the first letter and the second letter.

Just for Fun!

If your students like competition, divide the class into smaller groups and see who can get the most information from the excerpts. Remind students that they will need to give reasons for their inferences.

Background

Amy Eleanor Wingreen was a nurse from Chicago, Illinois, who volunteered to go to Cuba during the Spanish American War. At that time, Cuba had been a Spanish colony for about 400 years, and Spain was determined to keep it. The Cuban people were equally determined to become independent and began to fight against Spain. In the Monroe Doctrine (1823), the United States had declared its opposition to any further colonization by European countries in the Americas but had agreed to respect the colonies that already existed. At the same time, the United States very much wanted Spain out of Cuba, which is only ninety miles away from the coast of Florida. The United States sent a battleship, the USS Maine, to Havana Harbor in Cuba to protect U. S. citizens in the country. The stage was set for war.

The Spanish American War has sometimes been called “the war that Hearst made.” Newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst decided that promoting war against Spain would help him sell newspapers, so he started a propaganda campaign that churned up anti-Spanish, pro-war feelings. On February 15, 1898, there was a huge explosion on board the Maine, and it sank into the harbor. Despite a lack of evidence, the Hearst newspapers charged that Spain was responsible for the explosion and promoted the rallying cry, “Remember the Maine!”

Historians now believe that Hearst was only one factor in the overwhelming demand for the United States to declare war on Spain. There was also great sympathy for the Cuban desire for independence from a colonial power. In addition, reports that the Spanish treated Cuban prisoners cruelly outraged the American people. Certainly no one can deny that there was a kind of “war fever.” On April 21, 1898, the United States declared war.

Extension Activities

- Have students look at the digitized images of the letters themselves and see whether they agree with the transcriptions. Challenge them to decipher the words that the transcriber indicated only with [?]. If you think your students have a good suggestion for the missing words, please email the Newberry Library so that we can update the transcription.

- Have students look at some of the other letters in the Amy Eleanor Wingreen Collection and report back to the class what they have learned.

- Have students research conditions for soldiers in Cuba during the Spanish American war and write an essay describing them.

Words to Introduce

Excerpt │a part of a written text

Transcription │ the typed text of a handwritten document or an audio recording

Propaganda │ information, often biased or even false, used to influence public opinion

Additional Resources

Download a copy of the Amy Eleanor Wingreen Letters lesson plan, copies of the original letters, and copies of excerpt transcripts below.