Introduction

Between 1775 and 1850, most of the colonies in the Western hemisphere declared and successfully won their independence from the European monarchies of Great Britain, Spain, Portugal, and France. This era of European and American history is generally thought to begin with the Revolutionary War to found the United States of America and end with number of European efforts for democratic reforms in 1848, and is often referred to as the “Age of Revolutions or “Age of Revolution.”

In the American colonies formerly held by Spain and Portugal—what we now refer to as Latin America—colonists claimed independence in a series of military and political struggles between 1808 and 1825, capitalizing on a particularly tumultuous period on the Iberian Peninsula and in Europe more broadly. White elites of Spanish descent in the colonies, particularly those born in the Americas (known as criollos or creoles), protested the demands and constraints of the imperial states, particularly the taxes and other economic burdens imposed by the colonial powers on their colonies, and the lack of opportunities for creoles in colonial administration. These complaints converged with ideas of Enlightenment thinkers about freedom, progress, and representative government, and the examples of the revolutions in the United States, France, and Haiti, to form independence movements. These ideas also resonated with many members of oppressed and marginalized populations, including enslaved people, people of color, the Indigenous, the poor, and almost all women—many of whom joined the struggles for independence in hopes of winning greater measures of equality and freedom for themselves under new regimes.

By 1836, the former Latin American colonies of Colombia, Mexico, Chile, Paraguay, Venezuela, Argentina, Peru, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Ecuador, and Bolivia had gained independence from Spain; Brazil from Portugal; and Uruguay from Brazil. That year, Spain formally renounced all claims to these lands. Cuba and Puerto Rico would remain Spanish colonies until the Spanish-American War of 1898; in the Dominican Republic, the fight for independence from Spain and from Haiti continued into the 1860s.

Essential Questions:

- What were some of the contextual issues in the Spanish and Portuguese colonial empires that are important for understanding why an independence movement evolved?

- How did the American (United States), Haitian, and French Revolutions influence and differ from the Latin American independence struggles?

- How did people of different races, ethnic groups, and genders contribute to Latin American independence?

- What challenges faced newly independent Latin American nations in deciding how they would be governed? Who was involved in those decisions?

Colonial Contexts

Over three centuries of colonial rule, Spain and Portugal enforced a racial caste system. While complex and fluid, the system placed European-born whites at the top and people of color at the bottom.

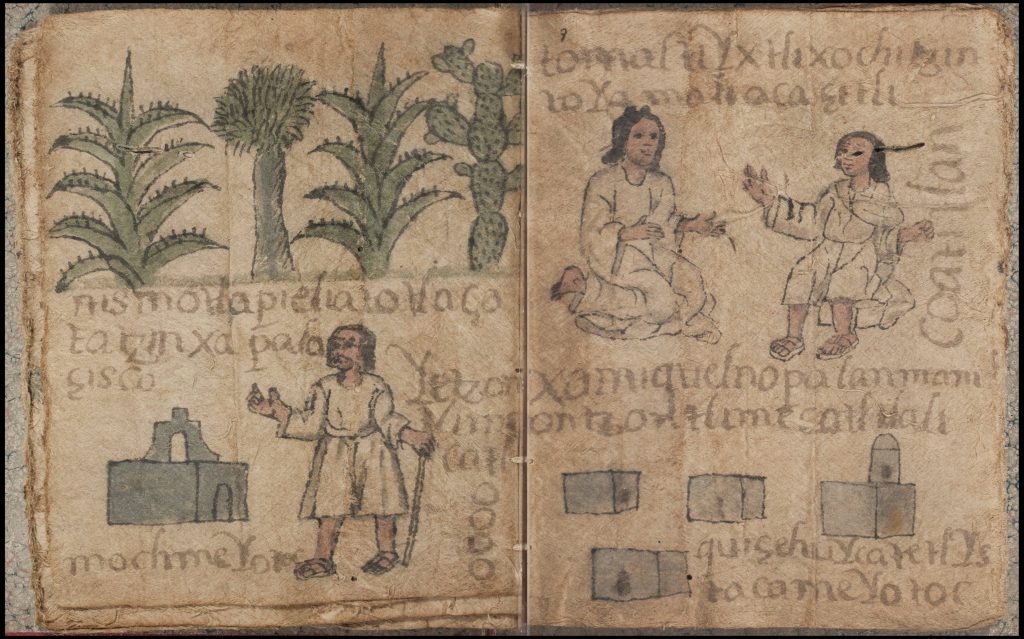

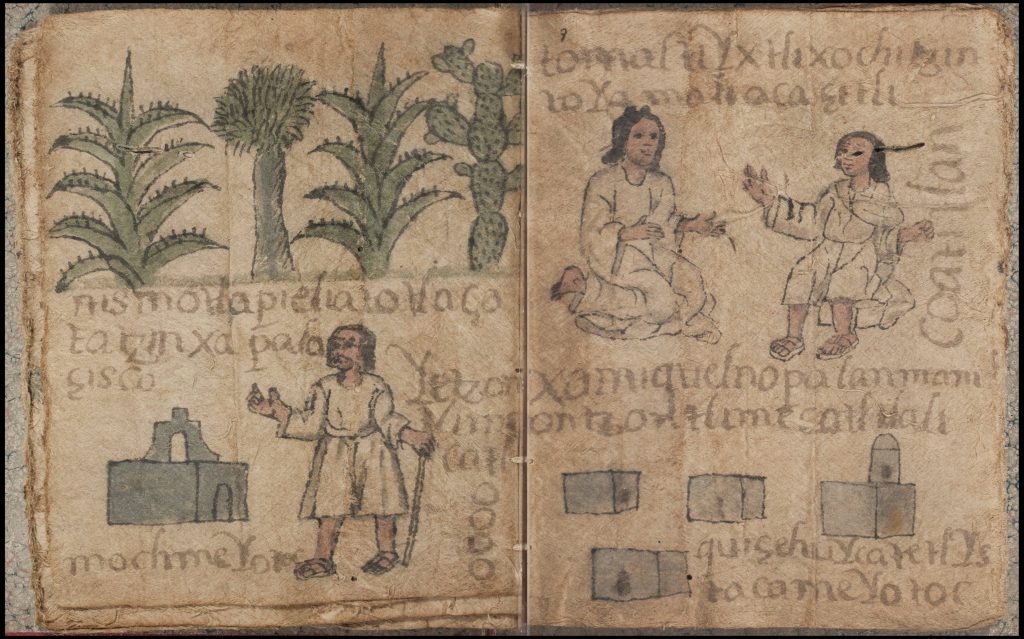

Many Indigenous people insisted on their human and land rights, even as colonial governments sought to extract work and wealth from them. In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the Spanish were imposing their own system of haciendas (large land estates, often plantations), ranches, and other mechanisms to regulate land in their colony of New Spain (which stretched from Central America to the Pacific Northwest). In response to policies threatening Indigenous communities’ land, water, and autonomy, communities developed Techialoyan documents, often called “village land books.” These manuscript documents aimed to support Indigenous land claims in Mexico by documenting the founding and history of a town, illustrating long-established boundaries predating the arrival of Spanish colonists. Indigenous people used the documents to prove to Spanish administrators that their towns’ autonomy should be respected as cabeceras (judicial districts). This example, known as the Codex Zempoala from the town of Zempoala in central Mexico, is composed of bound sheets of amatl paper, made in Mexico from pounded fig tree bark. It combines short written phrases describing the land in the Nahuatl language with illustrations of people, plants, buildings, and other features found there.

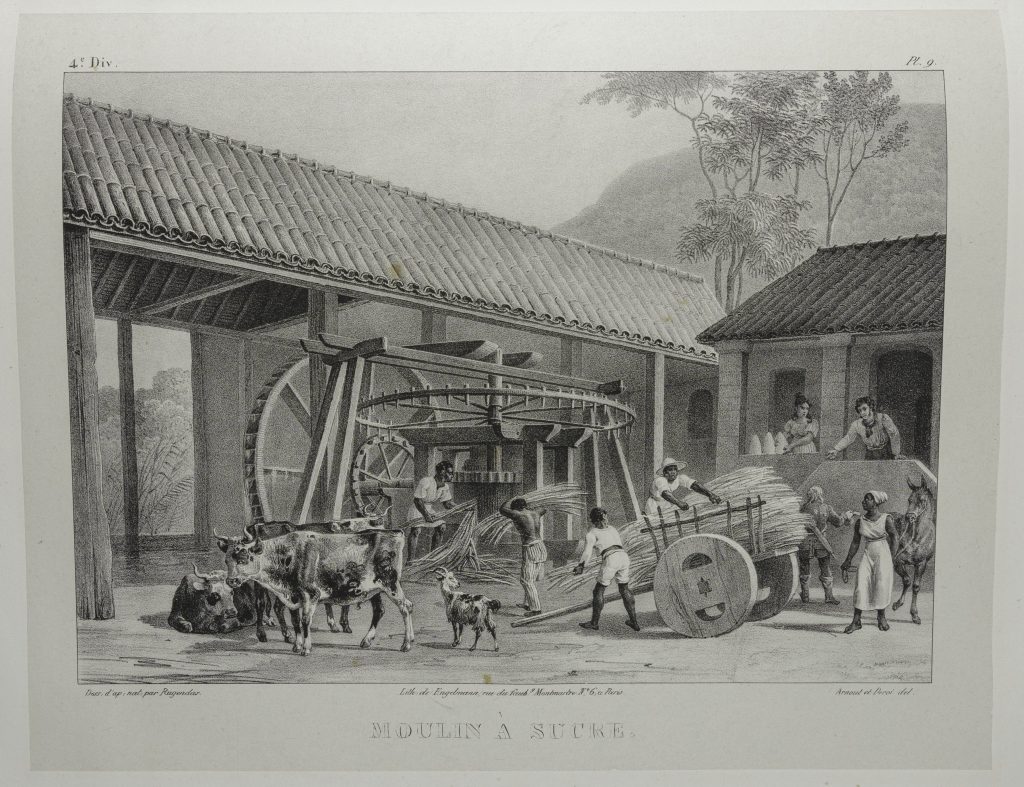

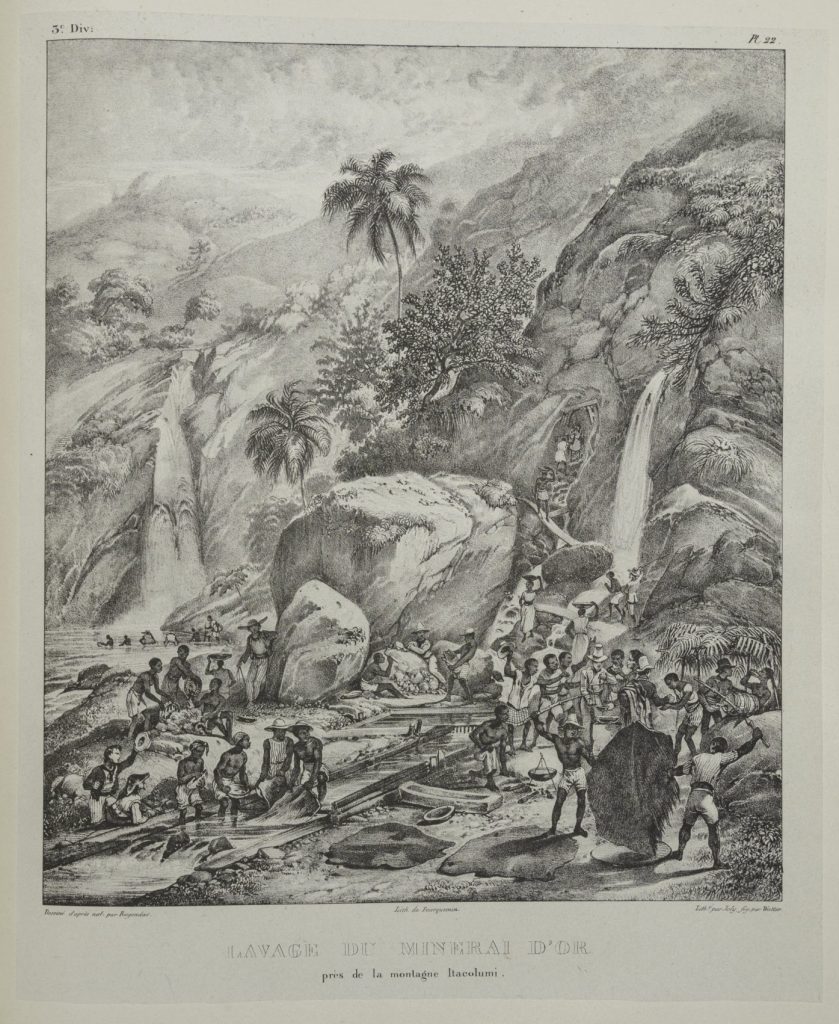

Enslavement of African-born people was central to the Spanish and Portuguese colonial enterprises in the Americas, particularly after Indigenous people were granted some rights and their slavery was abolished by the Spanish in the sixteenth century. Resources mined and harvested by enslaved Africans and their descendants provided wealth for European and American-born enslavers. A German artist, Johann Moritz Rugendas, visited Brazil as part of an exploratory and scientific mission in the 1820s. He depicted enslaved people working in a variety of capacities, including clearing forests for plantations; preparing cassava root, a food crop; harvesting coffee; operating a sugar mill; carrying water from a well; and gold mining.

Selection: Johann Mortiz Rugendas, Voyage pittoresque dans le Brésil, plates 6, 8, 9, 22 (1835).

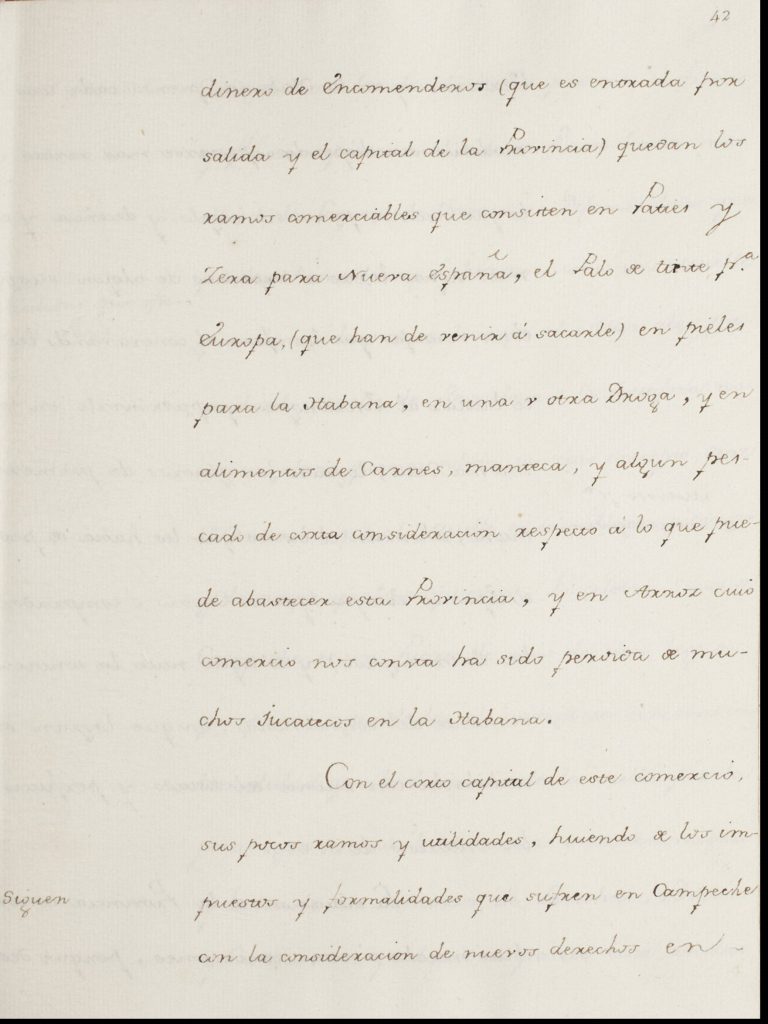

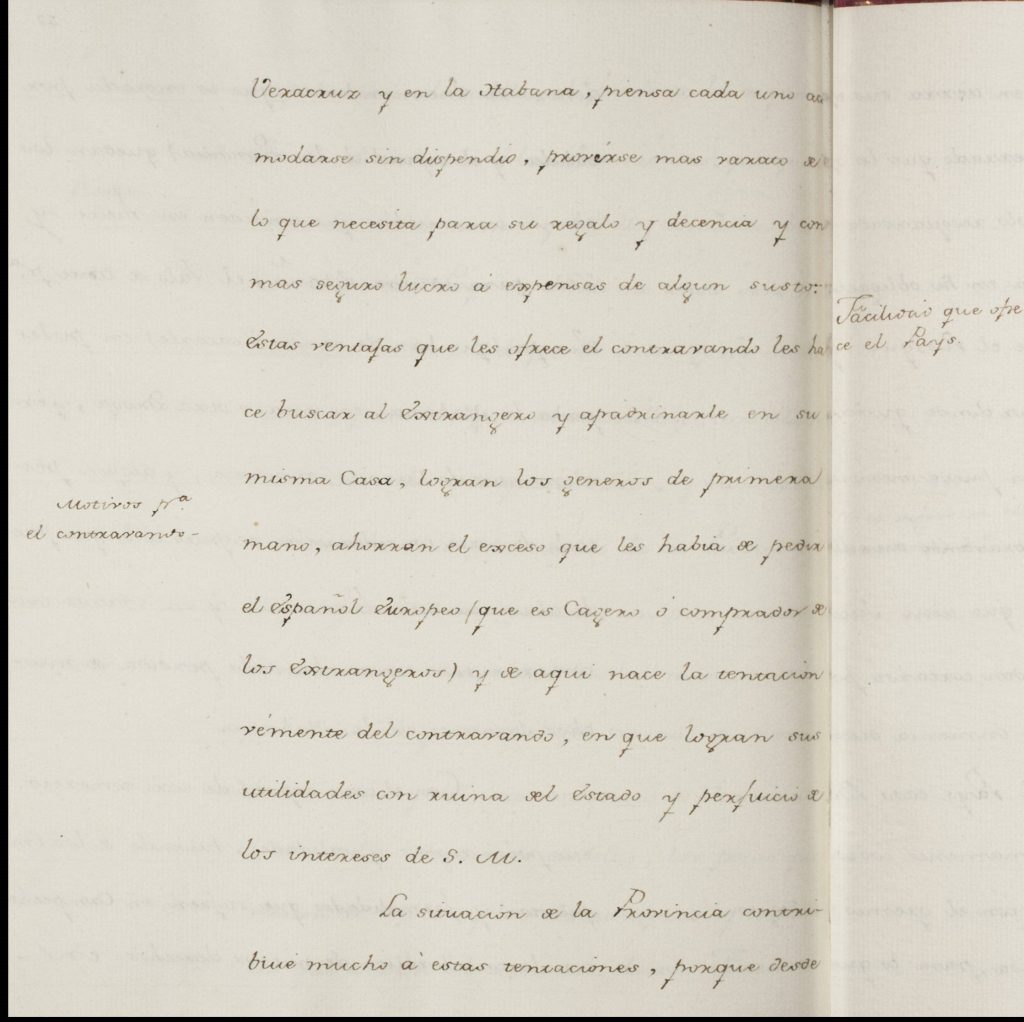

By the middle of the eighteenth century, Spanish monarchs instituted sweeping reforms of the administration of their colonies, known as the Bourbon Reforms (after the House of Bourbon, the noble family of the new Spanish royalty). Led particularly by José de Gálvez, Minister of the Indies, the reforms included transfers of power to Spanish-born administrators appointed by the crown from local American-born authorities (both creole and Indigenous) and a focus on improving revenue sent to Spain, including emphasizing mining of precious metals, improving tax collection, and restricting trade. Similar reforms were put into effect by the Portuguese in Brazil. American-born creole elites resented and protested these reforms, which reduced their autonomy and reinforced caste hierarchies. In a report to Gálvez from around 1766 about the Yucatán province in present-day southern Mexico, Spanish administrators explain their chronic problems with smugglers importing contraband goods on which Spain held a trade monopoly:

Selection: Descripcion de la Provincia de Jucatan con informe de su govierno secular y eclesiastico, comercio, cultivo, amenidad, situacion financiera (Description of the Yucatan Province, with a Report on Its Secular and Ecclesiastical Government, Commerce, Cultivation, Amenities, Financial Situation), 42r and 42v (c. 1766).

Translation of the above excerpt:

With the skimpy investment in trade here, and its few branches and profits, everyone, fleeing from the taxes and formalities suffered in Campeche and considering the new fees in Veracruz and Havana, thinks to accommodate himself without expense, to provide for himself more cheaply than by paying your taxes and fees, and with more certain profit–at the expense of some risk. These profits that smuggling offers make them look abroad and apart from their own homeland; they get cash in hand, and save the excess that had been asked of them by the European-born Spanish (who is cashier or buyer for foreigners), and it is here that the temptation of smuggling is born, in which they make their profits to the ruin of the state …

Questions to consider:

- Why do you think the Codex Zempoala includes a combination of drawings and written language? What different purposes and audiences might these types of communication (and the combination of the two) serve?

- Most official documents in the Latin American colonies were written on paper made in Europe and shipped across the Atlantic Ocean. What is the significance of the Codex Zempoala being made on Mexican amatl?

- Looking at Rugendas’s images of the work of enslaved people, what do you think the artist was most interested in? The work operations? The different classes of racial types of people involved? The relationships among enslaved people or between the enslavers and the enslaved? The context of rural or urban setting? Why do you think so?

- What motivations for independence do you find in the administrative report from the Yucatán? Consider motivations for consumers in the colonies, businesspeople involved in selling goods, and even the administrators writing the report.

Revolutionary Rumblings

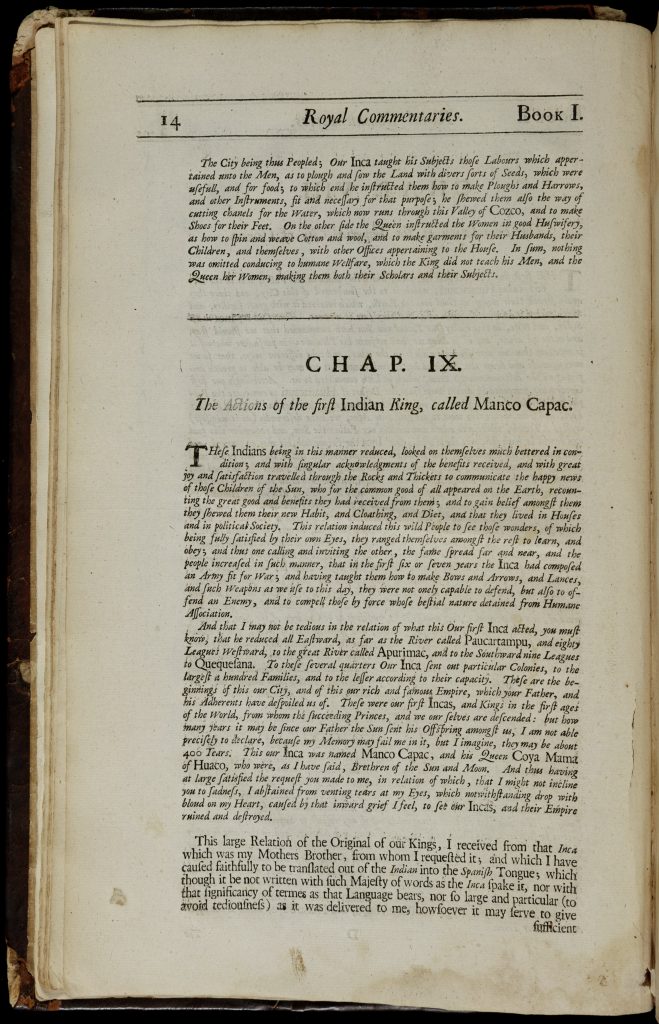

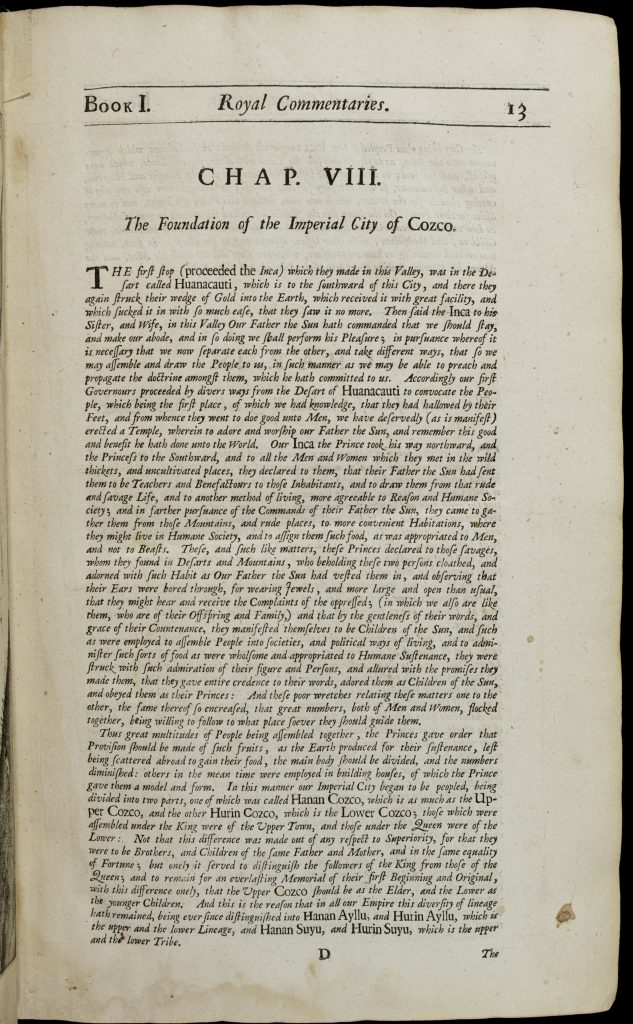

Many uprisings of Indigenous peoples, the enslaved, and mixed-race creole coalitions dissatisfied with European colonial governance preceded the wars of independence of the early nineteenth century. The Túpac Amaru rebellion in Peru from 1780-82 was the largest and bloodiest of these. The rebellion was originally led by the Indigenous kuraka (or clan leader) Túpac Amaru and his wife, Micaela Bastidas, and grew into a conflict that claimed tens of thousands of lives across present-day Peru and Bolivia. Túpac Amaru was motivated at least in part by a prophecy of the return of the Inca empire; the Spanish banned a popular account of the empire, Inca Garcilaso de la Vega’s Royal Commentaries of the Incas, in response.

Selection: Garcilaso de la Vega, The Royal Commentaries of Peru, “The City of Cuzco,” 13-14 (1688).

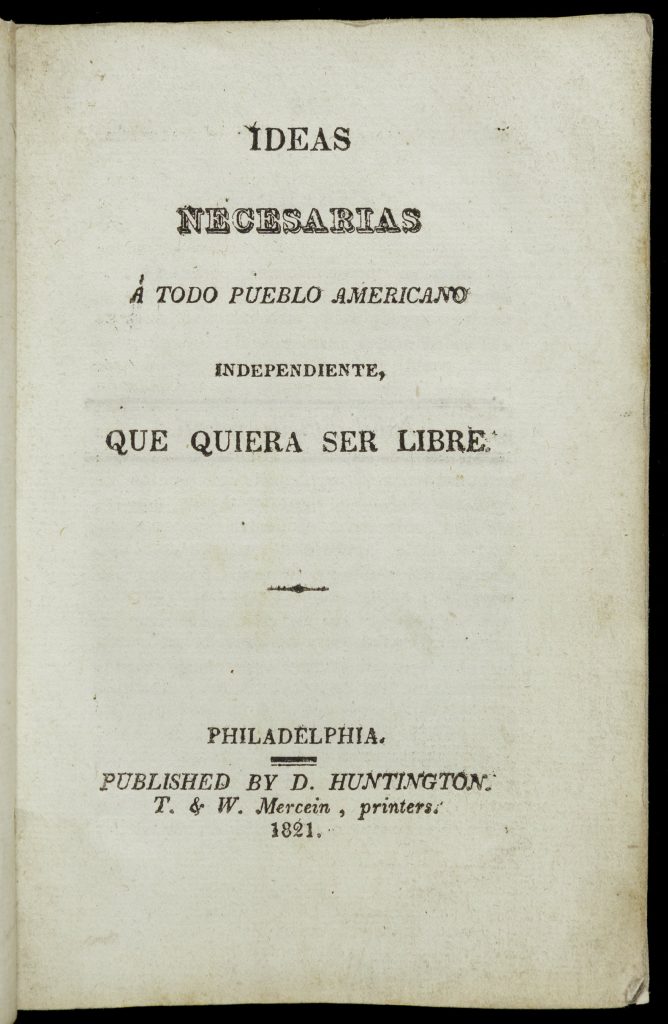

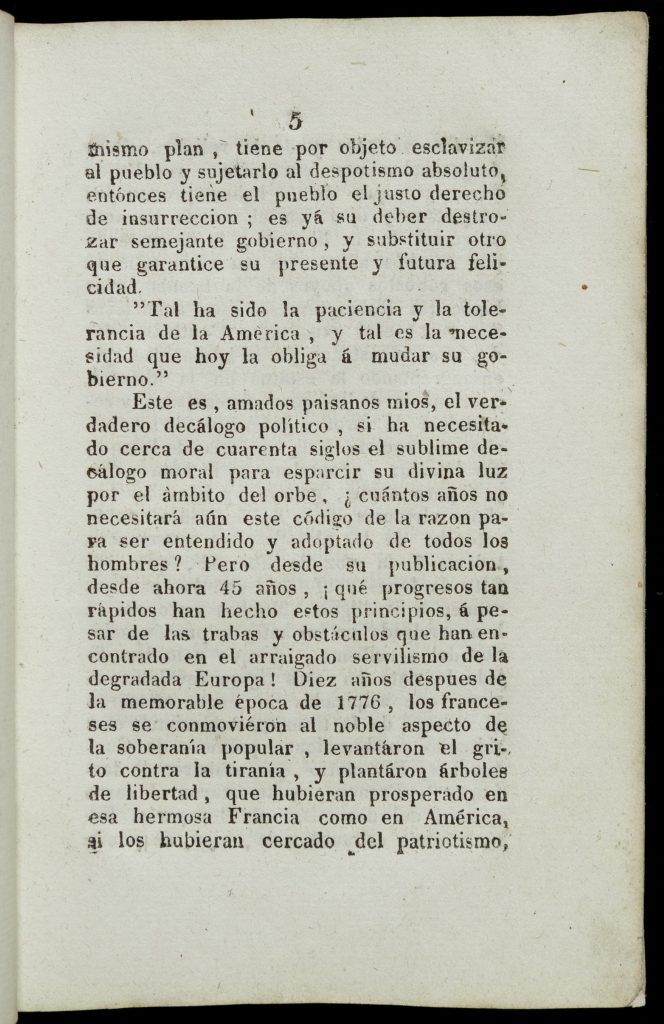

Tight control of the press by Spanish and Portuguese powers could not stop news of the revolutions in the United States, Haiti, and France from spreading in the colonies. Expatriates from Latin America who witnessed these changes and their aftermath firsthand brought radical ideas back with them to Latin America. The founding documents and republican structure of the government of the young United States were particularly influential. Vicente Rocafuerte, born into an aristocratic creole family in Ecuador, was based in the United States in the early 1820s, and in 1821 published Spanish translations of the United States’ founding documents as well as important speeches about its governmental structure, titled Ideas Necesarias á Todo Pueblo Americano Independiente, Que Quiera Ser Libre (Ideas Necessary for All Independent American People Who Want to Be Free).

Selection: Rocafuerte, Ideas Necesarias á Todo Pueblo Americano Independiente (Ideas Necessary for All Independent American People Who Want to Be Free), title page, 5-7 (1821).

Translation of the above selection:

These ideas [of constitutional government] so pleasing to rational man have gradually developed over time and prepared the current era of constitutional systems. This is now the general vote of Europe, and no matter how much those same impostors and vile tyrants who have replaced the great Napoleon try to oppose it, the august cause of constitutional freedom will triumph. There is no doubt, the victory is certain, despite the continuous and daily struggle that exists between ignorance and knowledge, superstition and religion, darkness and light, arbitrariness and law, caprice and justice. The constitutional laws are the true bases of grand and respectable freedom: the peoples of the world accustomed to the representative system will take giant steps in the race for their happiness…. In general, men are ready to use their reason… wanting to save as much as possible the fruits of their efforts and hard work, they will come to understand that it is absurd for people who live in deprivation, to give an income of 2, 3, or 4 million dollars to the so-called legitimate constitutional kings, such as those of France, England and Spain. They will compare the excessive expenses of these constitutional monarchies with the admirable economy of the American government; they will see the practicality that to govern great nations neither privileged families, nor crowns, nor crosses, nor titles, nor plagues of courtiers are needed; that only one head of the executive branch is enough, a president like that of the United States with $25,000 salary. Finally, they will understand that the most perfect government is the American one, the only one where man enjoys the greatest advantages of society, with the least possible tax; and as the human species has a natural tendency towards its perfection, the time will come when all aspire to change their constitutional monarchies into American governments; as today they are aspiring to change their despotic thrones into constitutional monarchies.

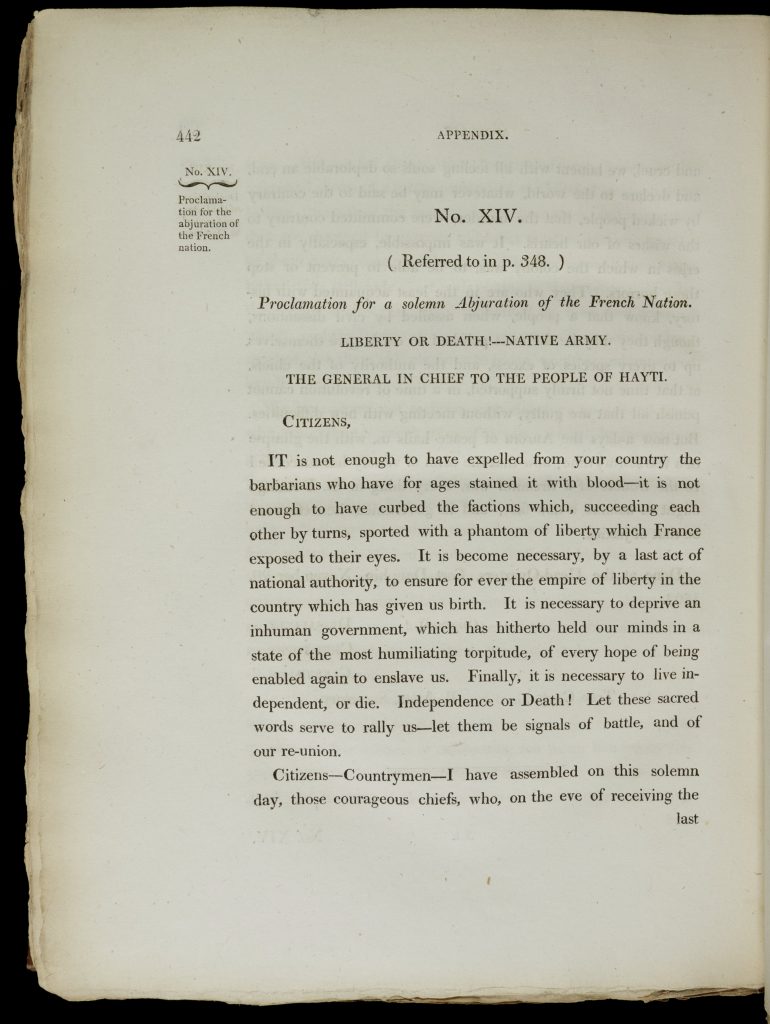

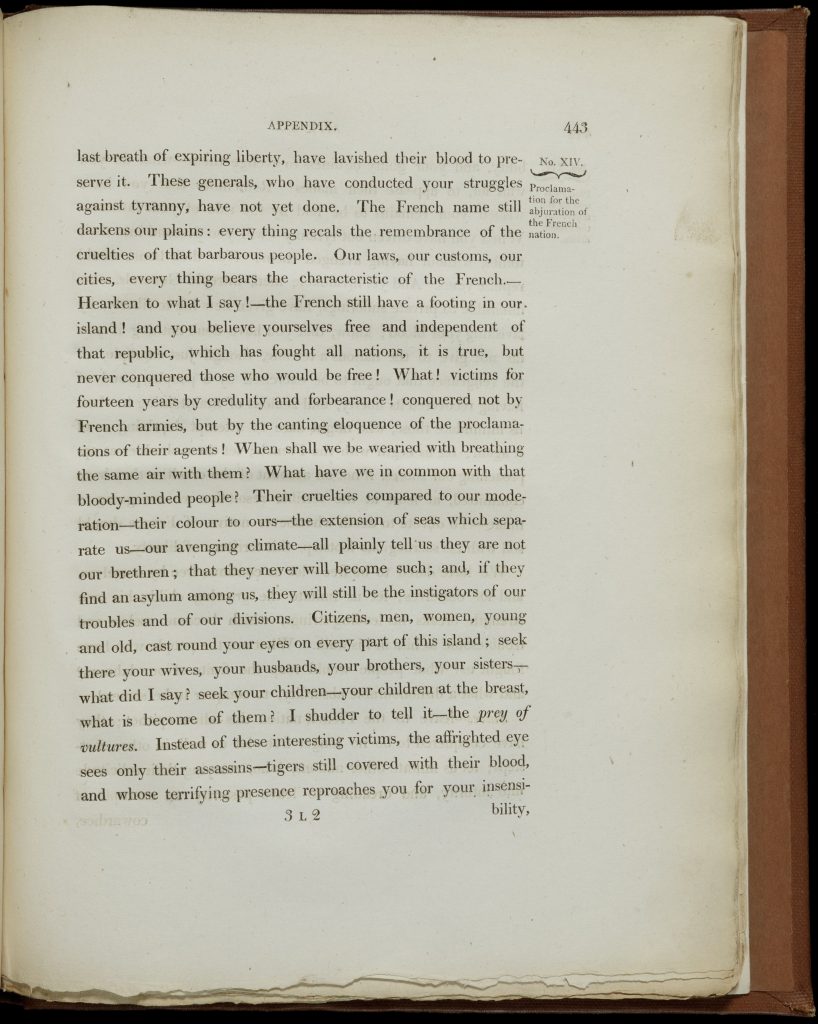

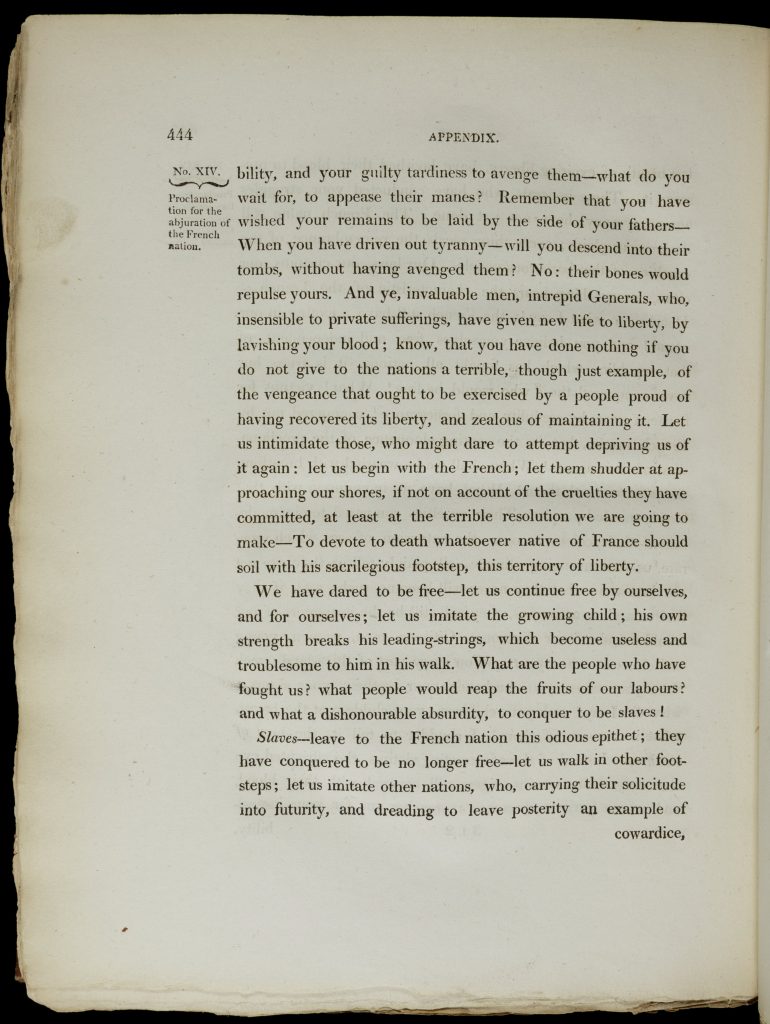

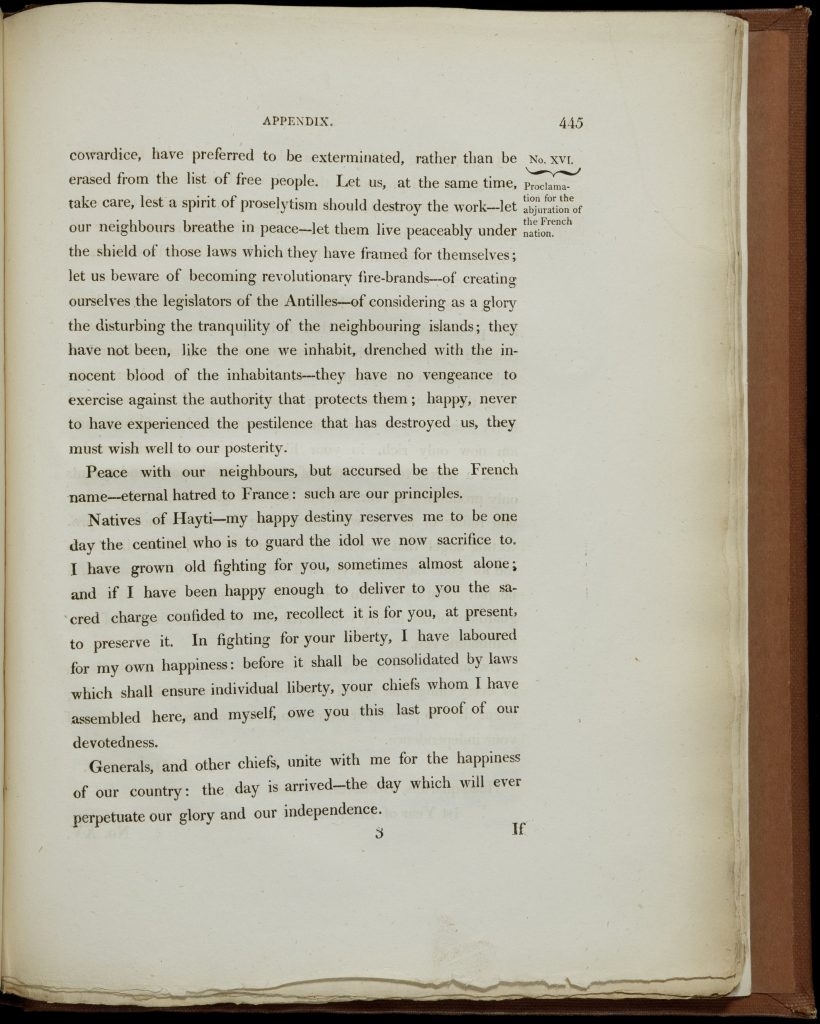

The impact of the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) on its mainland neighbors, both northern and southern, can hardly be overestimated. In the United States, news reports and the accounts of exiles from the former French colony of Saint-Domingue provoked discussion of abolition and Black capability, stoked fears of violent insurrections by the enslaved, and caused a reexamination of the country’s own revolution and founding documents. Early South American revolutionaries of African descent visited Haiti or were inspired by its example, including José Chirino (Venezuela, 1795), instigators of the “Revolt of the Tailors” (Brazil, 1798), and Francisco Xavier Pirela (Venezuela, 1799). The specter of “another Haiti” also was raised as the justification for merciless suppression of conflicts, and news about the conflict was suppressed as much as possible by administrators in colonial Latin America.

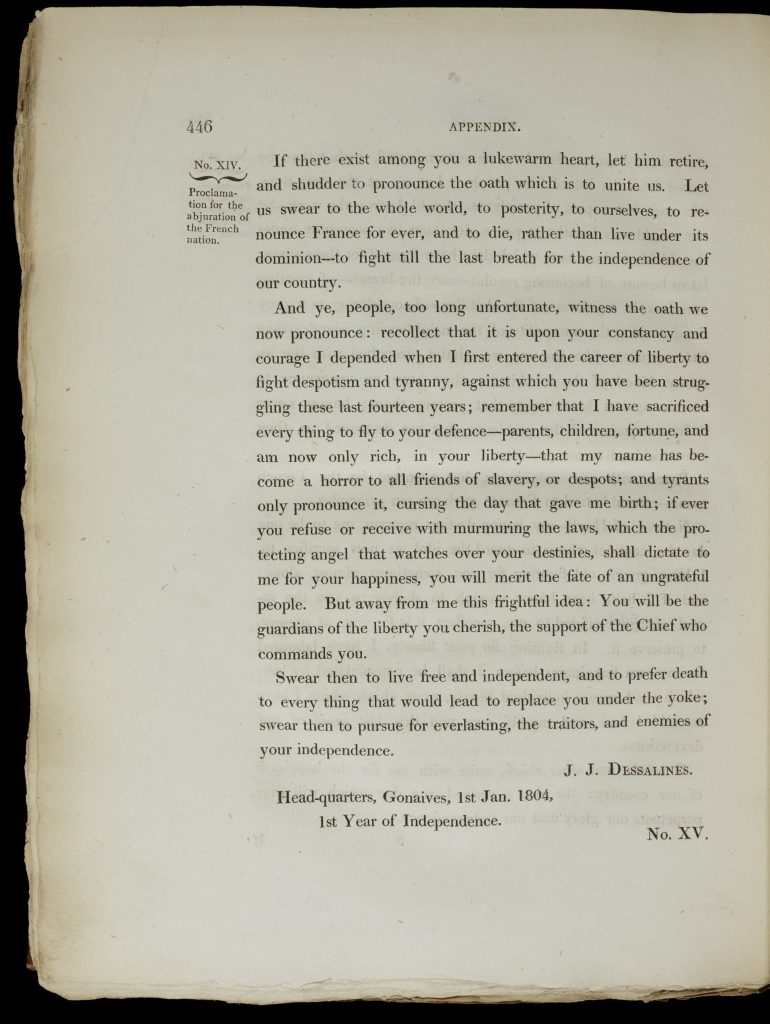

Selection: “Proclamation for a solemn Abjuration of the French Nation” [Haitian Declaration of Independence], in Marcus Rainsford, An Historical Account of the Black Empire of Hayti, 442-446 (1805).

Questions to Consider:

- Consider the visual depiction of Cuzco and the description of its founding in the Royal Commentaries of Peru. Why might the Spanish have felt threatened by this depiction?

- Examine the title page for Ideas Necesarias á Todo Pueblo Americano Independiente and think about the excerpt from Rocafuerte’s prologue. Who do you think his intended audience was for this book?

- Reading the Haitian Declaration of Independence, why do you think Spanish and Portuguese administrators found this document much more dangerous than the American Declaration of Independence? How does its rhetoric differ from the American Declaration?

Selection: Powers of the Peoples

Napoleon Bonaparte’s French army invaded and occupied Portugal in 1807 and then Spain in 1808. The Portuguese royal family fled across the Atlantic Ocean to Brazil, making Rio de Janeiro the new capital of the empire. In Spain, Napoleon forced the Spanish monarchs Charles IV and Ferdinand VII to relinquish the crown and placed them in exile. He installed his brother Joseph as king; Spanish subjects immediately rejected his rule, leading to six years of war to free the Iberian Peninsula. This conflict allowed movements toward independence to flourish in Latin America. Throughout the Spanish American colonies, in the absence of a leader acknowledged as an authentic monarch, groups of local civic leaders, or juntas, claimed power previously held by Spanish officials. From Mexico to Argentina, these new self-governing bodies first ostensibly ruled in the name of the true Spanish king, but long-held resentments by the American-born, mostly creole, leaders sparked movements toward true independence—which, in turn, sparked military conflicts.

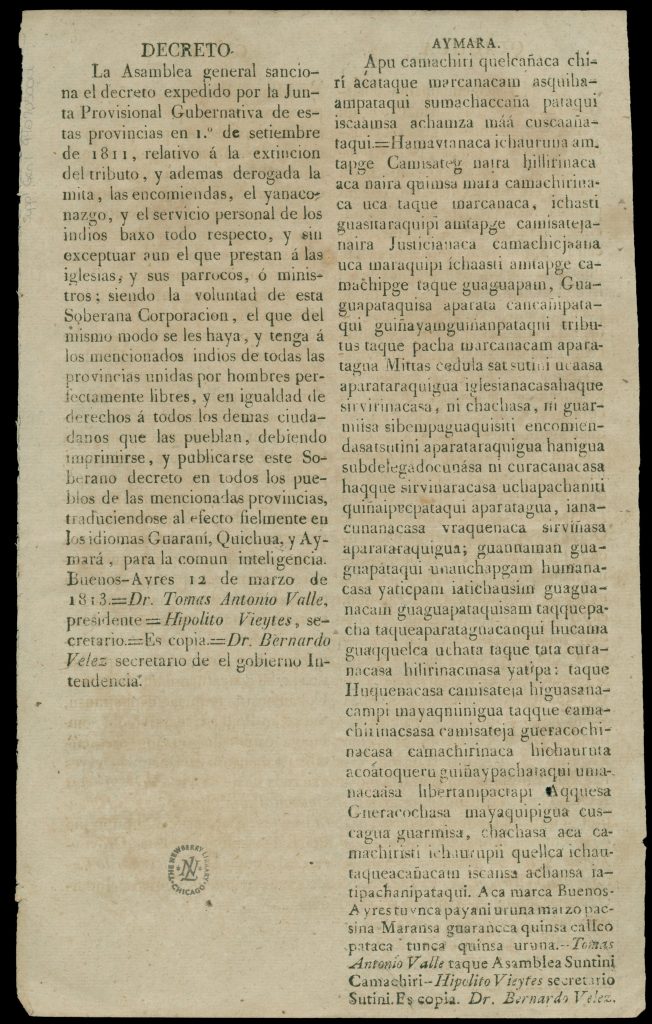

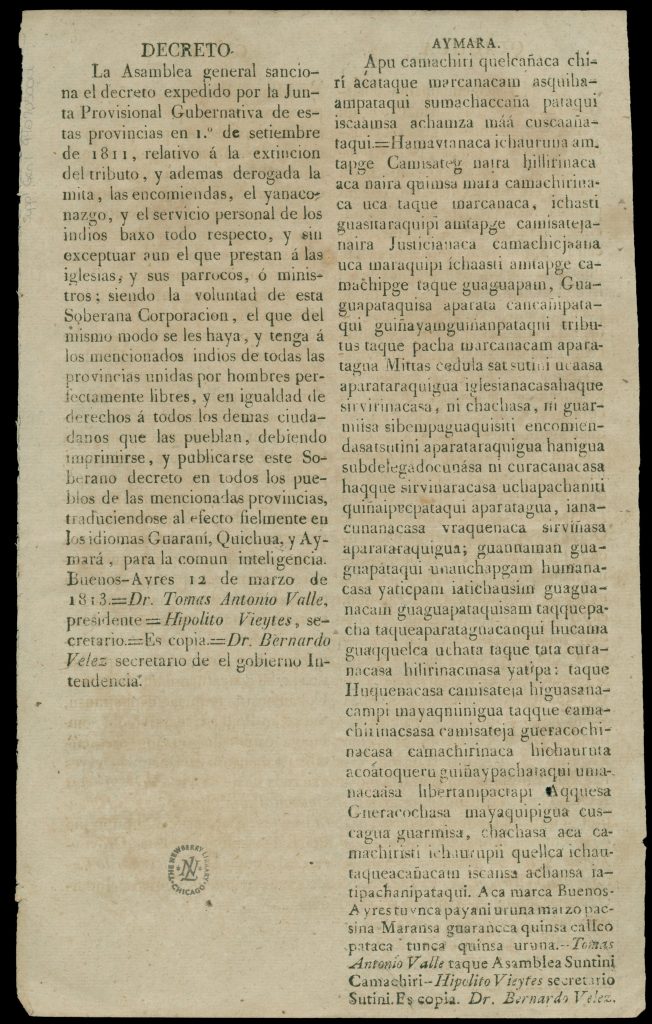

In 1813, the Argentinian General Assembly ratified the 1811 decree of the provisional Buenos Aires junta that abolished obligations for forced labor—the mita, encomienda, and yanaconazgo —and tributes to the church that had been expected of Indigenous people for centuries. Though many of these obligations had also been abolished under Spanish law earlier, the practice continued particularly in Andean regions. The government in Argentina printed the decree in the three most prevalent Indigenous languages of the region—Aymara, Quechua, and Guarani—in addition to Spanish.

Translation of selection from Decreto on the right:

The General Assembly sanctions the decree issued by the Provisional Government Junta of these provinces on September 1, 1811, regarding the extinction of the tribute, and also repealing the mita, the encomiendas, the yanaconazgo, and personal services of the Indians under all respects, and without excepting even that which they render to the churches, and their parish priests, or ministers; being the will of this Sovereign Corporation, that, in the same way, the aforementioned Indians of all the United Provinces are held as perfectly free men, and with rights equal to all the other citizens who populate them …

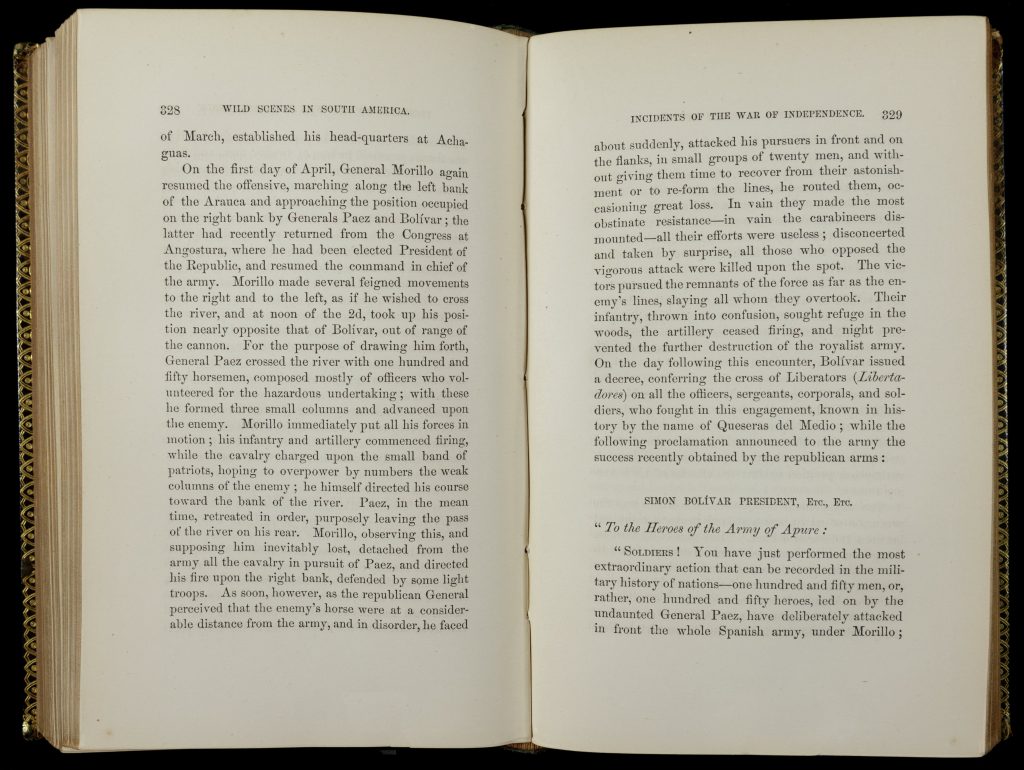

Creole leaders such as Simón Bolívar in Venezuela, José de San Martín in Argentina, Miguel Hidalgo in Mexico, Antonio José de Sucre in Peru and Bolivia, and Bernardo O’Higgins in Chile were the political and military leaders of these conflicts. Compared to other conflicts such as the revolutionary wars in the United States and Haiti, the armies fighting for independence in Latin America were thoroughly multiracial. Thousands of Indigenous people, free Black men, and others of mixed race served as soldiers. They included many non-white and mixed-race leaders such as Vicente Guerrero in Mexico and José Antonio Páez in Venezuela.

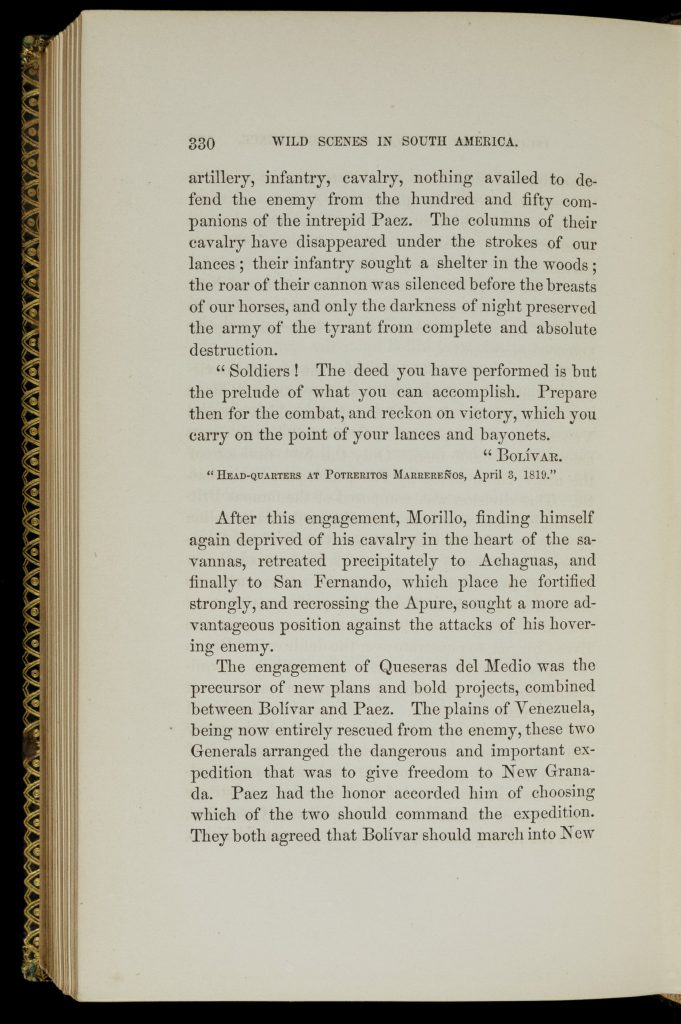

Páez led Venezuelan llaneros, herders of the grassy plains who acted as cavalry units as a result of to their skill with lances on horseback. The llaneros would become legendary and romanticized for their bravery and importance in Bolívar’s army. Páez’s son Ramón provided an account of the most celebrated victory of the llaneros, the Battle of Las Queseras del Medio, in his book Wild Scenes in South America; or Life in the Venezuelan Llanos:

Selection: Ramón Páez, Wild Scenes in South America, or, Life in the Llanos of Venezuela, 328-330 (1862).

Questions to Consider:

- Why do you think the decision was made to abolish Indigenous peoples’ monetary tribute and labor requirements in Buenos Aires in 1811, and ratified in 1813? What is the significance of it being printed in three Indigenous languages?

- What advantages of the South American rebels against the Spanish forces do you notice in the account from Wild Scenes in South America? What disadvantages?

- What arguments would you use to argue that Ramon Paez’s account of the Battle of Las Queseras del Medio is a trustworthy primary source? What arguments would you use to argue against that?

Liberty’s Promise, Liberty’s Problems

Independence in Latin America came at a massive cost—hundreds of thousands of lives and incalculable resources. Even before the wars with the Spanish forces (and Americano loyalists) were officially won, debates raged over the forms and principles of government for the new nations being formed. Bolívar and other framers of foundational documents in this period—primarily, but not exclusively, creoles—were profoundly influenced by ideas drawn from the writings of the French philosopher Montesquieu. In 1819, Bolívar convened the Second National Congress of Venezuela at Angostura (commonly referred to as the Congress of Angostura) to form the new nation of Colombia (later referred to as Gran Colombia, including present-day Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, and Panama, along with parts of other nations). In his Inaugural Address to the Congress, Bolívar proposed his understanding of the Montesquieu’s guidance, rather than the US Constitution, as a guiding light for the Congress’s deliberations:

Does not L’esprit de lois [Montesquieu’s treatise The Spirit of the Laws] state that laws should be suited to the people for whom they are made; that it would be a major coincidence if those of one nation could be adapted to another; that laws must take into account the physical conditions of the country, climate, character of the land, location, size, and mode of living of the people; that they should be in keeping with the degree of liberty that the Constitution can sanction respecting the religion of the inhabitants, their inclinations, resources, number, commerce, habits, and customs? This is the code we must consult, not the code of Washington!

Selection: Simón Bolívar, Selected Writings, 179-180 (1951).

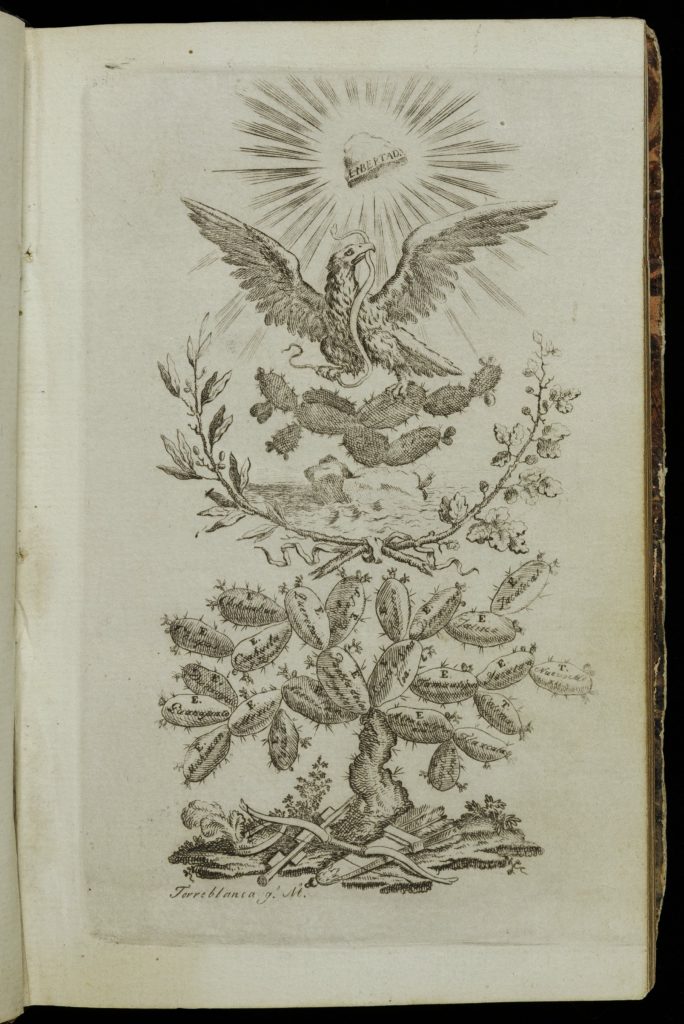

The tension between democratic ideals and republican constitutions on the one hand, and the belief of many creole leaders that Spanish tyranny had left the peoples of Latin America unprepared for full democracy on the other, led many nations to centralize power in the hands of a strong executive such as a President or Emperor. In many cases, this was ostensiblya temporary measure as the population acclimated to the participation required of citizens in a republic. In Mexico, for example, the military leader Agustín de Iturbide switched sides from the Spanish to the Mexican independence movement and led the Mexican forces in claiming victory in 1821. He was proclaimed constitutional Emperor of Mexico in 1822, but was resisted by the national congress, was forced into exile in 1823, and tried and executed upon his return in 1824. A new republican constitution was passed in 1824. The printing of the constitution was accompanied by an engraving symbolizing the new Estados Unidos Mexicanos (United Mexican States).

Questions to Consider:

- Compare the text from Bolívar’s address to the Congress of Angostura to the text from Vicente Rocafuerte’s prologue to Ideas Necesarias á Todo Pueblo Americano Independiente. What factors might explain the different rhetoric toward the United States’ system of government in these two works?

- Compare the image of Agustín de Iturbide as first emperor of Mexico and the engraved emblem of Mexico that accompanied the republican constitution of 1824. How do these images illustrate the transition from an authoritarian to a republican government?

Further Reading

For more information on castes in the Spanish colonies (and especially New Spain), see the Digital Collection “Caste and Politics in the Struggles for Mexican Independence.”

Ávila, Alfredo and Jordana Dym, eds. Los Declaraciones de Independencia: Los Textos Fundamentales de las Independencias Americanas. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, El Colegio de México, 2013.

Bolívar, Simón; Harold A. Bierck, trans.Selected Writings of Bolivar.New York: Colonial Press, 1951.

Chambers, Sarah C. and John Charles Chasteen, eds. and transl. Latin American Independence: An Anthology of Sources. Indianapolis IN: Hackett Publishing Company, 2010.

Chasteen, John Charles.Americanos: Latin America’s Struggle for Independence. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Dubois, Laurent.Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2005.

Fitz, Caitlin.Our Sister Republics: The United States in an Age of American Revolutions. New York: Liveright, 2016.

Langley, Lester D.The Americas in the Age of Revolution, 1750-1850.New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996.

Lynch, John. The Spanish American Revolutions, 1808-1826. New York: Norton, 1986.

Klooster, Wim. Revolutions in the Atlantic World: A Comparative History, New Edition. New York: New York University Press, 2018.

Ricketts, Mónica, Who Should Rule? Men of Arms, the Republic of Letters, and the Fall of the Spanish Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Soriano, Cristina. Tides of Revolution: Information, Insurgencies, and the Crisis of Colonial Rule in Venezuela. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2018.