Captions can provide important information about a photograph, map, or piece of art. When reading a caption, look for specific facts about the image: Who took the photo or created the art or map? When was it created? Where was the photo taken or what does the art or map show? Who is being shown? Is it from a book? Is it part of a museum or library collection? Double-check any facts in the caption with the details in the photo itself. Does the caption fit the image it’s describing?

Sometimes captions are not about the photograph, but are about the text around the photo or piece of art. This is often the case with captions in textbooks.

Consider this photograph and caption:

The caption tells us something about immigration, but it doesn’t relate any facts about the photograph itself.

Now look at the same photo with a more complete caption:

This caption tells us that this version of the photo was found in a book, the name of the book, the author, and the date the book was published. It also gives us information about where the photo was taken and who took the photograph. Finally, the caption gives us information about where we might find the photo ourselves.

The most complete captions are often ones that were written by or contain information from the artist or photographer, though there is always the possibility of bias or errors.

Consider this photo and its caption:

This photograph is also by Lewis Hine. The caption has information taken from the National Archives database written by the photographer himself. It includes the name of the woman at the center of the photo, the ages of the children, the exact date the photograph was taken, where it was taken, the name of the photographer, who the photographer was working for (the National Child Labor Committee), and where the photograph is now located (the National Archives).

Most captions do not have this much information, but consider how much more we know about this photo because of the detailed caption. We know the identity of the people in it, and why they were photographed. Further research on the Totora family might even be possible.

Captions in textbooks frequently don’t provide much real information about photographs. And, unfortunately, what they do provide is sometimes inaccurate or misleading.

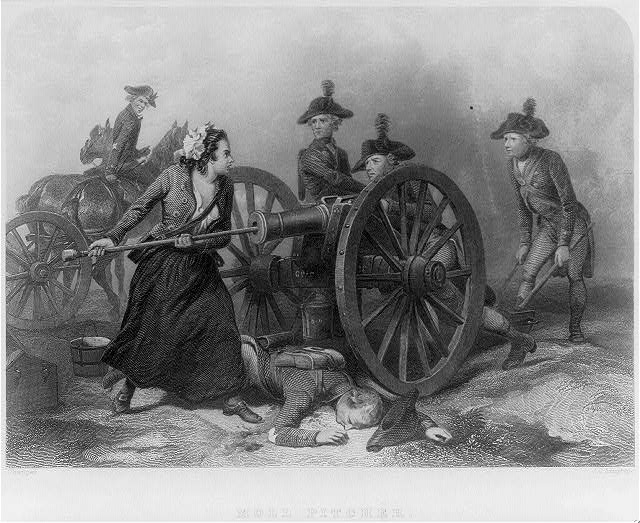

The caption that you see below the image is what you would see in most textbooks. It does not include who created the image or when it was created. The image has an “old” look to it, but it is actually an engraving created by J. C. Armytage in 1859 based on a painting by Alonzo Chappel, who was born in 1828, fifty years after the event portrayed. While the caption suggests that this is an actual depiction of Molly Macauley and her actions at the Battle of Monmouth, it’s really an illustration made up by an artist. This image is in the Library of Congress.