Curriculum Connections: Age of Jackson, Native American and Indigenous History, Second Great Awakening

From William Apes, A Son of the Forest: The Experience of William Apes a Native of the Forest, Written by Himself (1831).

This activity can be used as part of a lesson on the Second Great Awakening. It can also be used as part of instruction on context clues, close reading, the experiences of American Indians, and how to gather information from a primary source. You may want to review the Skills Lesson: Reading a Transcription with students.

Display the text. You can also download a copy of the transcription in the Downloads tab. Give students time to read it, generate questions, and write notes. Use the background material at the end of this activity whenever you think it will encourage students to ask more questions and think more about how to engage with the material.

About this time the Methodists began to hold meetings in the neighbourhood . . . And it was openly said that the character of a respecable[sic] man would receive a stain, and a deep one too, by attending one of their meetings. Indeed the stories circulated about them were bad enough to deter people of “character!” from attending the Methodist ministry. But it had no effect on me. I thought I had no character to lose in the estimation of those who were accounted great. For what cared they for me? They had possession of the red man’s inheritance, and had deprived me of liberty; with this they were satisfied, and could do as they pleased; therefore, I thought I could do as I pleased, measurably. I therefore went to hear the noisy Methodists. When I reached the house I found a clever company. They did not appear to differ much from “respectable” people. They were neatly and decently clothed, and I could not see that they differed from other people except in their behaviour, which was more kind and gentlemanly. Their countenance was heavenly, their songs were like sweetest music—in their manners they were plain. Their language was not fashioned after the wisdom of men. When the minister preached he spoke as one having authority. The exercises were accompanied by the power of God. His people shouted for joy—while sinners wept. This being the first time I had ever attended a meeting of this kind, all things of course appeared new to me. I was very far from forming the opinion that most of the neighborhood entertained about them. From this time I became more serious, and soon went to hear the Methodists again, and was constrained to believe that they were the true people of God. . . .

I now attended these meetings constantly, and although I was a sinner before God, yet I felt no disposition to laugh or scoff. I make this observation because so many people went to these meetings to make fun. This was a common thing, and I often wondered how persons who professed to be considered great, i.e. “ladies and gentlemen,” would so far disgrace themselves as to scoff in the house of God, and at his holy services.

. . . The power of the Holy Ghost moved forth among the people—the spirit’s influence was felt at every meeting—the people of God were built up in their faith—their confidence in the Lord of hosts gathered strength, while many sinners were alarmed, and began to cry aloud for mercy. In a little time the work rolled onward like an overwhelming flood. Now the Methodists and all who attended their meetings were greatly persecuted. All denominations were up in arms against them, because the Lord was blessing their labours and making them (a poor despised people) his instruments in the conversion of sinners.

William Apes, A Son of the Forest: The Experience of William Apes a Native of the Forest, Written by Himself, 37-38 (1831)

Potential Questions

- What can you figure out about William Apes, the author of this text? Why do you think that?

- What kind of meeting is the text describing?

- What does the author think about the people in the meeting?

- What does the author think about the people who laugh at the meetings?

- What does he think of the people who attend the meetings for sincere reasons?

- What do the quotation marks around “character” and “ladies and gentlemen” mean? Why do you suppose Apes italicized noisy Methodists? How do the quotation marks and italics change the meanings of these words and phrases?

- Whom do you think the book was written for?

- When was it written?

- Why do you think William Apes wrote it?

- This text is about the Second Great Awakening. What does it tell you about this movement?

- Think about what you already know about the Second Great Awakening. Does this excerpt challenge or confirm what you know? Does anything in the excerpt surprise you?

- What other questions does this excerpt inspire? What else do you want to know after reading it and how could you find that information?

Background

William Apes (later changed to Apess, 1798–1839) was mixed-race Pequot Indian. His father, William, was also mixed-race Pequot. His mother, Candace, was a descendant of Metacomet, also known as King Philip, chief of the Wampanoag Confederacy during King Phillip’s War. She may have also had some African ancestry. Apes was a Methodist preacher, writer, and political activist. His book A Son of the Forest was among the first autobiographies published by a Native American. Some scholars consider him among the most important Indigenous activists of the antebellum era.

Apes was fifteen at the time of the events described in the excerpt and an indentured servant in an unwelcoming household, having been “sold” on from several previous households. Shortly after the events described here, he ran away and joined the army as a drummer. He saw action in the War of 1812. Apes was already preaching to mixed groups when was baptized in 1818. He was ordained by the Protestant Methodists in 1829, the same year the first edition of his autobiography was published. This autobiography is part of a religious literary tradition of the “conversion narrative,” or testimony. In the ten years after his autobiography was published, Apes wrote a number of texts about Christianity, history, and American Indian rights. His final book was Eulogy on King Philip, as Pronounced at the Odeon, in Federal Street, Boston (1836), a speech written from the perspective of the Wampanoag leader.

Extension Activity 1

Use some elided text from the first paragraph of the excerpt to help students use context clues to better understand unfamiliar words.

The unelided first paragraph reads:

About this time the Methodists began to hold meetings in the neighbourhood and consequently a storm of persecution gathered; the pharisee and the worldling united heartily in abusing them. The gall and wormwood of sectarian malice were emitted, and every evil report prejudicial to this pious people was freely circulated. And it was openly said that the character of a respecable[sic] man would receive a stain, and a deep one too, by attending one of their meetings. Indeed the stories circulated about them were bad enough to deter people of “character!” from attending the Methodist ministry.

Work with students to look at the context of these words: pharisee, worldling, gall, and wormwood. Ask, can you get a rough idea of what they mean? Do you need to know the exact meaning of these words to understand what the author is saying?

Extension Activity 2

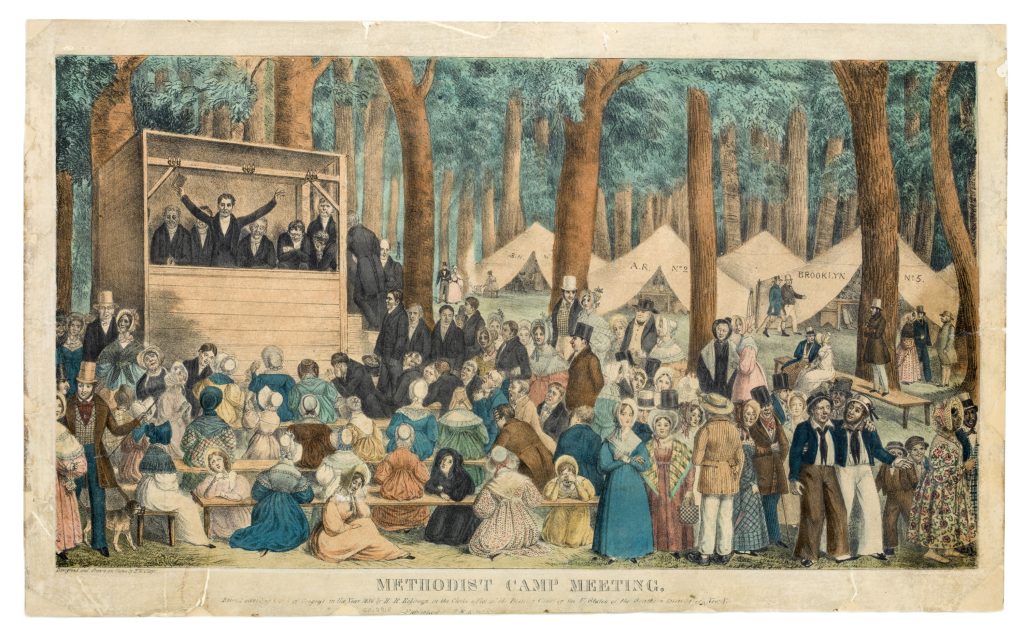

Images such as the ones below are used in textbooks and other middle and high school history materials to illustrate the Second Great Awakening. Have students compare Apes’ description of the Methodists revivals he attended to the images below. How do the images confirm what Apes describes? How do they differ and where are they different?

Click on the images for high-resolution versions that can be displayed for your class.

Additional Resources

The entirety of several of William Apes books are part of the Edward E. Ayer Collection at the Newberry Library, including On our own ground : the complete writings of William Apess, a Pequot, edited by Barry O’Connell.

Many of Apes’ books have also been digitized and can be found on the Internet Archive:

Download copies of this activity and the transcript from A Son of the Forest below.