Themes

Gender & Religion

Manuscript Studies

Middle English Lit

Periods & Events

Medieval Period

Skills & Document Types

Image Analysis

Text Analysis

Suitable for an introductory college survey course or an advanced high school class.

Materials – Available for Download in the Downloads Tab:

- A copy of the “Contexts for the Book of Margery Kempe” lesson (with discussion suggestions)

- A copy of the Student Discussion Guide (without discussion suggestions)

- A copy of the images used in this lesson

Curriculum Notes

These course materials are designed to facilitate and extend open-ended, student-led discussions of the Book of Margery Kempe at a college level. The additional exercises in this module introduce students to primary sources from late-medieval England and teach some basic skills in manuscript studies. Two Skills Lessons (linked below) guide them through initial encounters with medieval literary texts in their natural manuscript habitats, rather than in modern editions. The discussion questions build on close reading and visual analysis of primary materials to inform critical thinking about Kempe’s narrative, in particular around the complexities of literacy and gender in medieval England.

A little bit of historical context can help students to better appreciate the craft of the Book of Margery Kempe. These materials attempt to provide that context through direct, guided engagement with Newberry Library manuscripts. We focus particularly on excerpts from the Book printed in all recent and upcoming editions Norton Anthology of English Literature; each chapter is accompanied by a manuscript skills lesson. The course materials are designed to be suitable for use in an introductory survey course in British literature (in which Margery may likely make a brief appearance), or for a more advanced undergraduate course on Middle English literature in which larger sections of her Book are read. We use the modernized text of Margery’s Book in the Norton for all quotations. This lesson is ideal for a second or third day of class discussion on the Book of Margery Kempe, as it focuses on the excerpts drawn from later sections of the book. Prior to this class, instructors will have introduced their students to the Book itself and some of the major critical questions it raises. This lesson may be used piecemeal or in full — whatever works for the instructor.

The Student Discussion Guide can be assigned to students to read themselves or paraphrased in class as part of a guided discussion. (Discussion questions are marked with ❧.) The two Skills Lessons may be distributed in PDF or printed as two-sided handouts for individual or group work. Larger images files for use in slides are available for download here.

Pre-class Assignments

Students should have read an introduction to the Book of Margery Kempe, e.g. in the Norton or in Lynn Staley’s open-access edition published by TEAMS.

Read excerpts from the Book of Margery Kempe.

In the Norton, 10th ed., vol. I:

- 1.20: Margery Sees the Host Flutter at Mass (pp. 446–47)

- 1.60: Margery’s Reaction to a Pietà (pp. 452–3)

- 1.28: Pilgrimage to Jerusalem (pp. 447–48)

- 1.35: Margery’s Marriage and Intimacy with Christ (in Rome) (pp. 448–9)

For students using the other editions, they may use these chapter numbers to find the reference

Discussion Guide

Introduction

Margery Kempe was an extraordinary medieval writer: her Book is the oldest autobiography written in the English language available to us. In her Book, she tells the story of her spiritual life as a devout Christian who is moved by her belief and her visions to go on pilgrimage to faraway holy sites and frequently to wailing and crying. If you have read the first chapter of her Book, you already know that Margery Kempe didn’t exactly write it. Other people, she says, actually put pen to paper and wrote down the story as she told it in 1436. In fact, Margery distances herself from writing and reading books when she claims to be “not lettryd” herself. That expression—“not lettryd”—is flexible: she could mean that she was uneducated, or that she could not read books in Latin, or that she was just not that into reading. Margery, however, wants her Christian readers to trust her religious experiences and to learn to be better devoted to God through her own writing. Her own Christian education comes in many forms in her Book. Priests instruct her and answer her questions in person; they also read to her from spiritual books about Christian life, theology, and the lives of medieval visionaries like Bridget of Sweden. One story in the Book even begins with Margery worshipping at church, prayerbook in hand. If she’s “not lettryd,” why carry around a book?

You might have a lot of questions like these, because reading Margery’s extraordinary and sometimes perplexing Book from a modern perspective can be difficult to comprehend. As modern readers, we must come to an understanding of this text even though there is so much about its historical context we don’t know. This collection of materials will provide a little bit of context by opening up a few of the medieval books in the collections of the Newberry Library. It guides readers through a first-hand exploration of Margery’s wider world to contextualize the narrative of her life in her Book. We’ll focus on two short episodes: Margery’s vision of a fluttering dove at Mass (book 1, chapter 20) and Margery’s reaction to an image of Mary (book 1, chapter 68). Along the way you will learn the basics of how to read medieval writing (an area of study called paleography) and how to describe a page of a medieval manuscript.

Visions and the Vulgar Tongue: Book of Margery Kempe 1.20

One day as this creature was hearing her Mass, a young man and a good priest holding up the sacrament in his hands over his head, the sacrament shook and flickered to and fro as a dove flickers with her wings… Then said our Lord Jesus Christ to the creature, “You shall no more see it in this manner, therefore thank God that you have seen. My daughter, Bridget saw me never in this manner.”

I.20; p. 446 in Norton

In this chapter, Margery narrates a miraculous vision in her local church. At that solemn moment when the priest presents the Communion wafer to the congregation, Margery is granted a precious, fleeting vision. As usual, Margery refers to herself only as “this creature.” The voice of Jesus Christ himself then assures her that her vision is special, never seen before even by “my daughter Bridget.”

His “daughter Bridget” is Bridget of Sweden, a visionary woman who had lived about 100 years before Margery. So — what was Margery doing when she compares herself to Bridget, and their experiences?

❧ Let’s start by looking at a traditional illustration of Bridget of Sweden. Our example is from the beginning of her book called Revelations, in a book printed in 1482 and now at the Newberry Library. How has this artist chosen to represent Bridget? Write down what you’re seeing.

- Possible student answers in discussion: she is depicted WRITING her book, seated at desk with MORE BOOKS; she is depicted during a VISION; she sees GOD THE FATHER hold the CHRIST, SUFFERING; there’s a DOVE; an ANGEL speaks in her ear; a MALE KNEELING FIGURE prays with her in LATIN; she is in a full NUN’S HABIT. (STUDENTS MAY ASK ABOUT: a walking stick, bag, and cap of a PILGRIM; a SHIELD WITH SPQR, representing her pilgrimage to Rome)

❧ Taken together, what do all of the choices you’ve discussed say about Bridget herself? How does this image represent Bridget as a source of spiritual authority for other Christians?

- Her visions are true; she has a visionary AND literate kind of authority; she was recognized as holy or inspired by at least one man who here represents the authority of the (male) church.

❧ Now read through the rest of the passage of Margery’s vision in the church, with an eye for points of connection between this depiction of Bridget and Kempe’s portrayal of herself, “this creature.” How does Margery represent herself as a figure of spiritual authority, like or unlike Bridget? How are these strategies for claiming authority like or unlike those used by the artist when depicting Bridget?

- Strategies: unique, one-time VISION; her DESIRING direct CONVERSATION with Christ, including a PROPHECY; the ENVY and SCORN of the unrighteous people as ultimate validation; she is continuing the project begun by BRIDGET.

- Note specific echoes with Bridget: the specific vision of the DOVE; the VISIONARY SOURCE aspect of her authority; the “speaking directly to Christ”. Broader echoes: the pilgrim identity/going to Rome; Margery also has some holy men who validate her authority

- Note differences: Jesus says that she was given a unique revelation different from Bridget; Margery is “DESPISED” and object of men’s scorn while Bridget is shown respected by a devout, Latin-speaking man. Broader difference: the fact that Bridget writes down her own revelations and is presented as learned, while Margery presents herself as “NOT LETTRYD”, putting more weight on her visions.

Skills Lesson 1: Margey’s English in Manuscript

Margery says that the priest who held up the Host at Mass was a “good, young priest.” Why would this detail matter to Margery or her medieval readers?

To answer that question, let’s explore a manuscript from the Newberry Library (MS 32.9) in Skills Lesson 1: Reading Middle English in Manuscript.

Reading, Seeing, and Feeling: Book of Margery Kempe 1.60

The medieval pope Gregory the Great famously wrote, “Pictures are used in churches so that those who are ignorant of letters may at least read by seeing on the walls what they cannot read in books.” In Margery Kempe’s Book, images do a lot more than just instruct this admittedly “unlettyred” author in the Bible or Christian theology. Margery already knows the stories these images tell. More than that, images activate intense responses. The sights of Jerusalem where Jesus died, for instance, compel Margery to “weep and sob so plenteously as though she had seen our Lord with her bodily eye suffering his Passion” in chapter I.28 (pp. 447–8 in the Norton). Closer to home in England, she has a similar reaction to something she sees in a church in nearby Norwich.

She went to the church where the lady heard her service, where this creature saw a fair image of our Lady called a pity. And through the beholding of that pity, her mind was all wholly occupied in the Passion of our Lord Jesus Christ and in the compassion of our Lady, Saint Mary, by which she was compelled to cry full loudly and weep full sorely, as though she should have died.

1.60, p. 452 in the Norton

What did Margery see when she says she saw an image called a pity?

The editors of the Norton have translated “pity” as a pietà in their chapter title, “Margery’s Reaction to a Pietà.” The most famous example of a pietà is a magnificent sculpture by Michelangelo of Mary mourning over the dead body of Jesus. This grand marble statue, however, has little in common with what Margery saw. The pietà scene of Mary holding the dead body of her son was a popular one for artists working across medieval Europe, long before Michelangelo carved his masterpiece in Rome. The vast majority of these pietà pieces were much more humble, made with simpler materials. Margery Kempe might have seen the “fair image of our Lady called a pity” painted on a church wall, or on a cloth hanging. Maybe she saw a small sculpture, cut from wood or from soft, white alabaster stone.

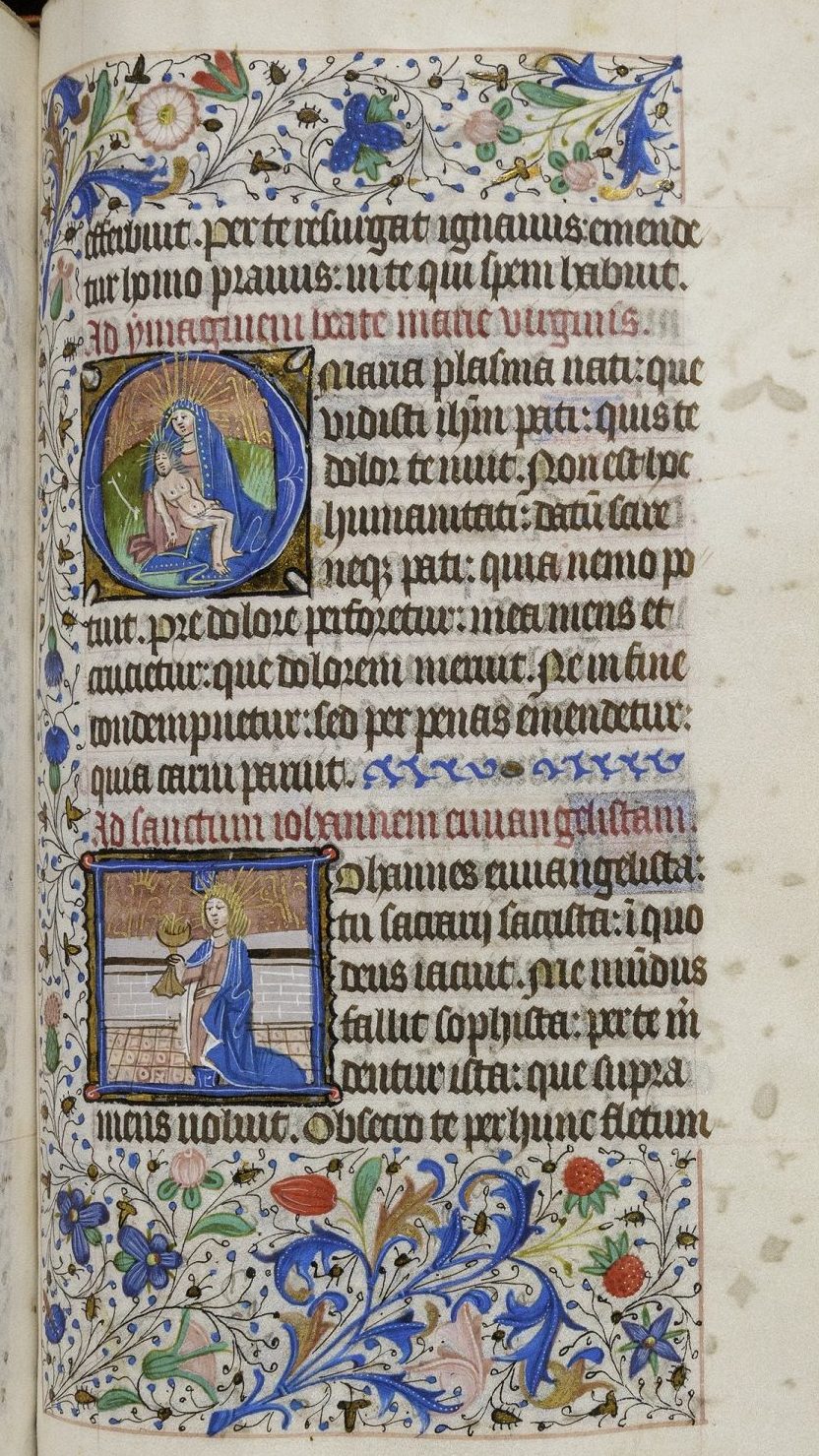

The ‘pity’, pietà, or lamentation of the Virgin was also a popular image to paint in medieval prayerbooks: perhaps this lady of Norwich opened her prayerbook to a page decorated with a ‘fair image of our Lady called a pity.’ The Newberry Library holds about a half-dozen or so of these prayerbooks, called ‘books of Hours.’ Books of hours recorded a sequence of prayers to be recited throughout the day at particular times. The Hours were usually written and recited in Latin (though one Newberry book of hours is written in Dutch). They could also be lavish luxury objects, full of beautiful and costly decorations.

Skills Lesson 2: Anatomy of a Manuscript Page

There is an excellent example of an illustrated book of hours from England in the Newberry collections (Case MS 35). Go to Skills Lesson 2: Anatomy of a Manuscript Page. This exercise will give you some vocabulary to describe what you notice in medieval books just by looking at them. (You don’t need to know Latin.)

Reading a little of the Latin prayer-poem, addressing Mary, on this page of Case MS 35 can give us some insight into how the image on the page and the text work together. Here is what is written in Latin; see if you can recognize where this quotation begins and ends.

Non est hoc humanitati: datum scire neque pati: qui nemo potuit.

Pre dolore perforetur: mea mens et crucietur: que dolorem meruit.

*Italics = abbreviations

Translated this means something like:

Humanity was not created to feel such sorrow, or to suffer through it, nor can any one else feel it;

Let my own mind be pierced and tortured by that extreme pain, for it deserves that pain.

❧ Discuss this passage from the pietà poem and Margery’s narrative of the pity. What commonalities do you see between them?

- Both are occasioned by IMAGES (the poem is “to the Image of the Virgin”; if you don’t do the Skills Lesson you will want to tell students this); both fix on COMPASSION, the vicarious feeling of suffering and take MARY and its figure of ultimate compassion.

The prayer-poem in the Newberry manuscript and the Book of Margery Kempe are participating in a hugely important religious and cultural movement among medieval Christians called affective piety, which infused their religious devotion (Latin pietas) with an intensity of feeling and emotion (affectus in Latin). A central point of medieval (and modern) Christian doctrine holds that Jesus Christ was fully divine and fully human at the same time. Because he was fully human, he felt suffering, pain, and sorrow like a human. Medieval Christians practiced affective piety in many different ways, but this focused devotion to Christ’s humanity and in particular to his suffering during the Passion and on the Cross was absolutely essential to it. And crucially, practicing affective piety did not require an official church position, or a university education, so affective piety was a mode of medieval Christian spirituality that an “unlettered” woman like Margery Kempe could embrace and exemplify.

From a certain perspective, the Book of Margery Kempe is a drama of the conflict between Margery’s own affective mode of spirituality and the resistance of other Christians, especially from men of the church, like bishops and priests. For instance, look at how Margery describes the aftermath of her reaction to the pity:

Then came to her the lady’s priest, saying, “Damsel, Jesus is long dead since.”

When her crying was ceased, she said to the priest, “Sir, his death is as fresh to me as if he had died this same day, and so I think it ought to be to you and to all Christian people. We ought to ever have mind of his kindness and ever think of the doleful death that he died for us.”

p. 453 in the Norton

The Book is filled with moments like this one in the Norwich church, where Margery describes her own personal version of affective piety.

❧ Search throughout your readings from the Book of Margery Kempe for other examples of Margery’s brand of affective piety. Pay close attention to her choice of words, her imagery, or her book’s point of view. You might look specifically for:

- the events of the Passion and Crucifixion

- the senses and the body: vision, sound, touch, smell, taste, heat; sickness and health; fasting

- pilgrimage, travel to holy sites in Jerusalem, Rome, and Norwich

- interactions with strangers, friends, and clergy (like priests and friars)

- reverence for Mary, other women saints; discussion of motherhood and chastity

This question is meant to give instructors latitude to connect these exercises with whatever they’ve assigned or chosen to focus on in discussion.

Visualizing Affective Piety: A Survey of Objects

In Skills Lessons 1 and 2, you learned to transcribe medieval writing and to describe a medieval manuscript page. You’re going to use those skills now to describe images of “pities” and the Passion from across late-medieval Europe (England, France, Holland, and Germany) in the Newberry Collections.

All these images are available to download here. You can also download a PDF packet of these images in the Downloads tab or access high-resolution online versions by following the links below.

Instructor may choose to use particular objects here to discuss with the whole class; or they may be distributed among the class.

- Case MS 56, fol. 151r (pietà, the prayerbook of Margaret of Croy)

- MS 40.1 fol. 40r (pietà, Rouen book of hours)

- Case MS 50.5, fol. 89r (pietà, Rouen book of hours)

- Case MS 45, fol. 26r (pietà, Paris book of hours)

- Case MS 61, fol. 120v (pietà, Dutch book of hours)

- Case MS 192, laid-in fragment with a heart-shaped illustration (pietà, German prayerbook)

- Case BV468 .E86 1512, woodcut on the very last page (pietà, French printed hymnbook)

- Case MS 35, fol. 148r (arma christi, English book of hours)

- MS 32, head of roll (arma christi with Crucifixion, The Stations of Rome)

- Case folio W 0145 .357, fol. D7v (Man of Sorrows woodcut in Passiones Christi)

- Inc. 2230 fol. 1v (Image of Bridget of Sweden)

- “Lamentation with Donors,” ca. 1440-1450, Chazen Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison (part of the Center for Renaissance Studies Consortium)

About the Author

Joe Stadolnik is an independent writer and researcher living in Chicago. He has held research fellowships at the Institute of Advanced Studies at University College London and the Institute on the Formation of Knowledge at the University of Chicago. He has published research on medieval English literature, medicine, alchemy, and manuscript culture in multilingual, international contexts. He is also the editor of A Treatise on the Astrolabe for the Cambridge Complete Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, with Jenna Mead.

Download the following materials below:

- A copy of the “Contexts for the Book of Margery Kempe” lesson (with discussion suggestions)

- A copy of the Student Discussion Guide (without discussion suggestions)

- A copy of the images used in this lesson