Curriculum Connections: African American History, Civil Rights, Post-World War II, 1950s

Items in this lesson come from the Prescott Family Papers and the Gartz Family Papers.

Download a copy of this lesson plan or a copy of the source images and transcripts in the Downloads tab.

You and your students are going to read a rough draft of a letter or speech and an excerpt from a personal diary. Both sources describe housing discrimination and the practices of redlining and blockbusting in Chicago in the 1960s, one from a Black perspective and one from a white perspective. These sources are then followed by a third source, an excerpt from an encyclopedia which provides context and background information.

Blockbusting occurred when real estate agents frightened white homeowners into selling their homes cheaply out of fear that their neighborhoods would be “taken over” by Black families. Redlining occurred when financial institutions used federal government maps to deny mortgages, insurance, or Federal Housing Administration (FHA) loans to anyone living in an “undesirable” (i.e., African American or poor white) neighborhood. More detailed descriptions of both practices and their legacies can be found in Background Material below, as well as in the third source.

This lesson can be taught in a few different ways depending upon the time available. You could start by showing the original letters and work on deciphering cursive text with your students or simply focus on the transcriptions.

Be aware that the second excerpt was written by someone who was prejudiced. It uses two words that today are considered offensive: “colored” which was not considered offensive at the time, and “blackies” which was and is still offensive. If the language of this second excerpt is a concern, the lesson can also be taught using only the first except and the encyclopedia entry.

You can read the Newberry’s Statement on Potentially Offensive Materials and Descriptions here.

Process

This lesson is for a teacher-controlled class. The first two texts are primary sources. The third text is a secondary source.

Examining the Originals

Starting with the original materials is a way to help students see how historians work and why they have to be able to read cursive in order to explore the past. Display the original sources. (Links are provided with the sources below. You can also download a PDF of the sources and transcriptions in the Downloads tab.)

Zoom in and have students try to decipher the text. Discuss how difficult or easy it is to read the handwriting. Ask students to determine what kind of text they are reading and how they know that. Students might point out that the first source has crossed out sections and looks like a rough draft and the second source looks like a diary. Discuss with students how (or if) looking at the original documents changes their understanding of the texts versus only reading the transcripts.

Click the links below for high-resolution versions of the images to download or display for your class. You can also download a handout with these images in the Downloads tab.

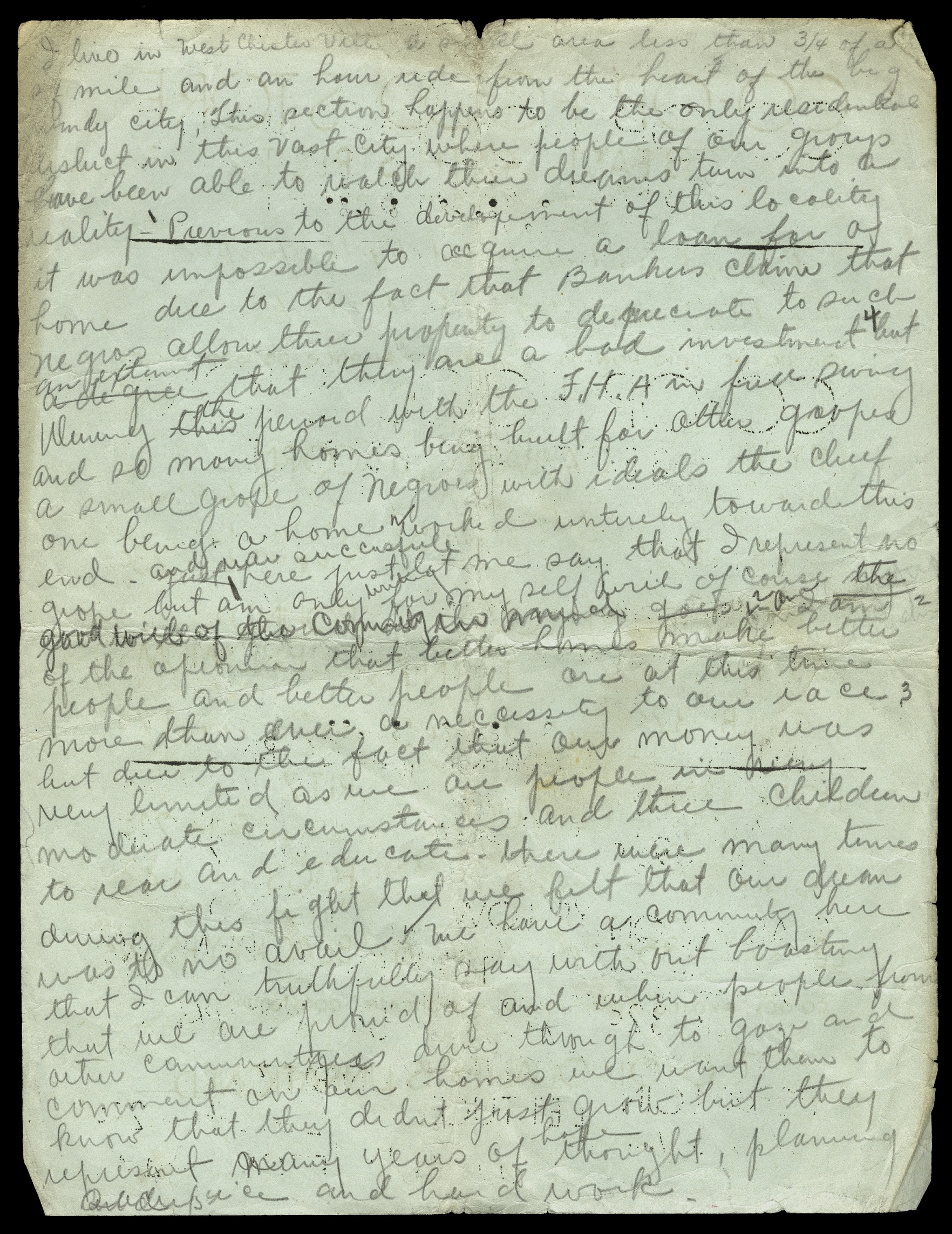

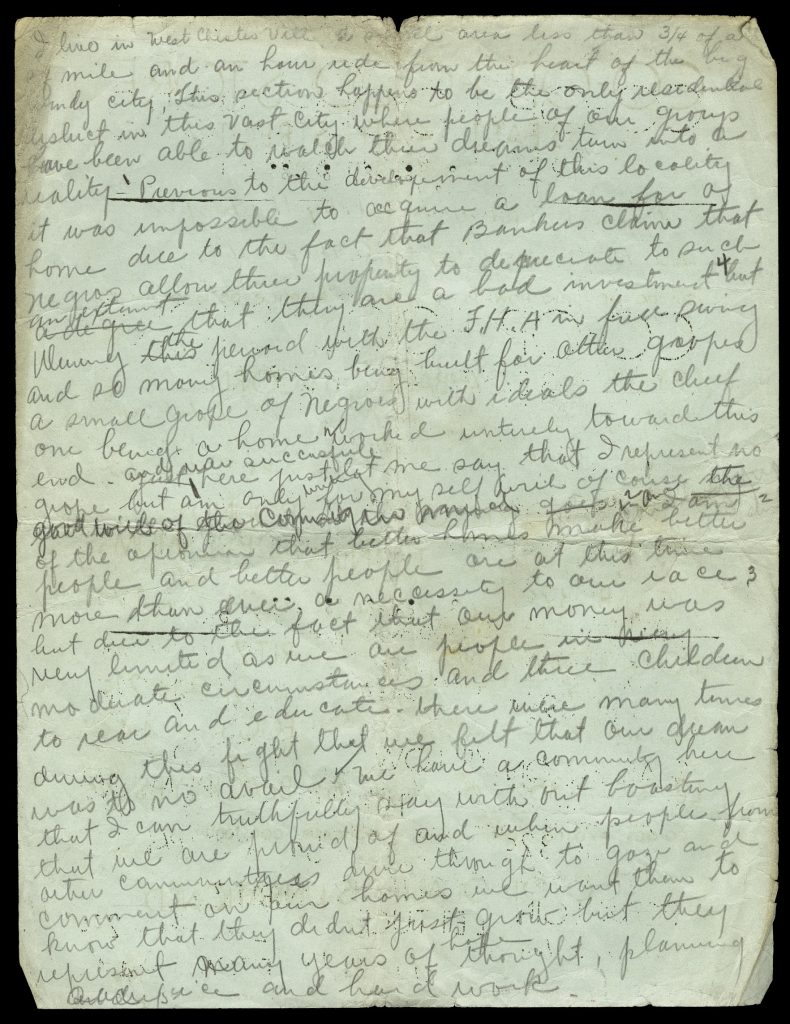

Source 1 – Document by Eunice Lyons Prescott

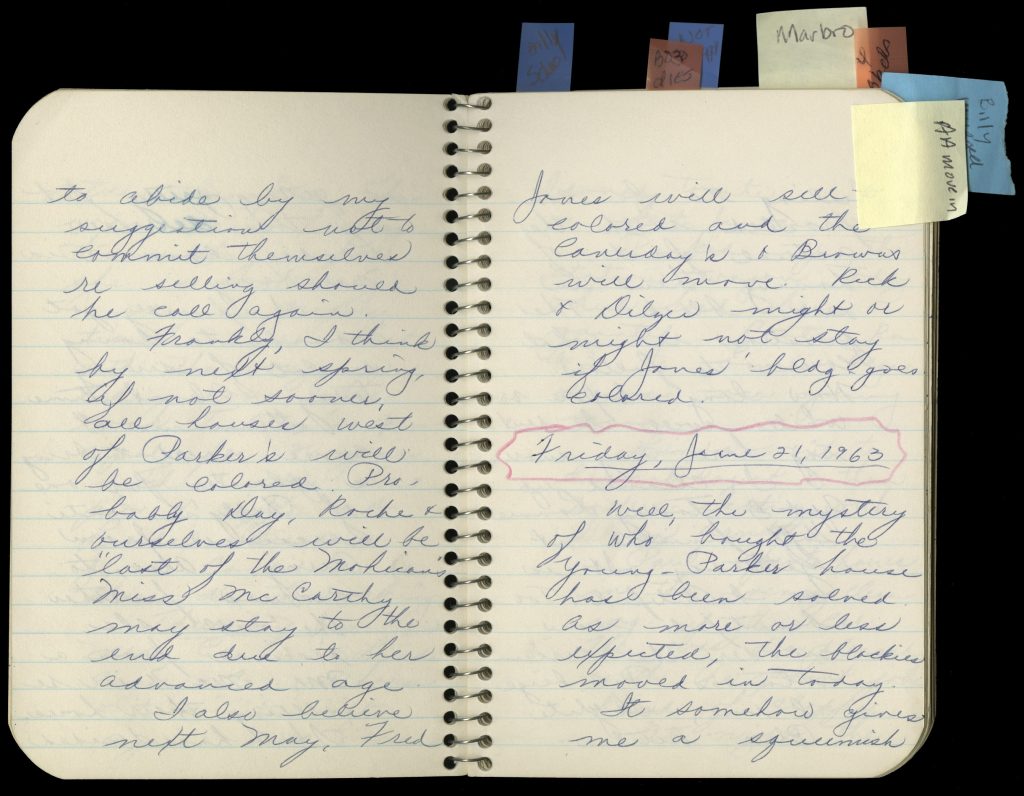

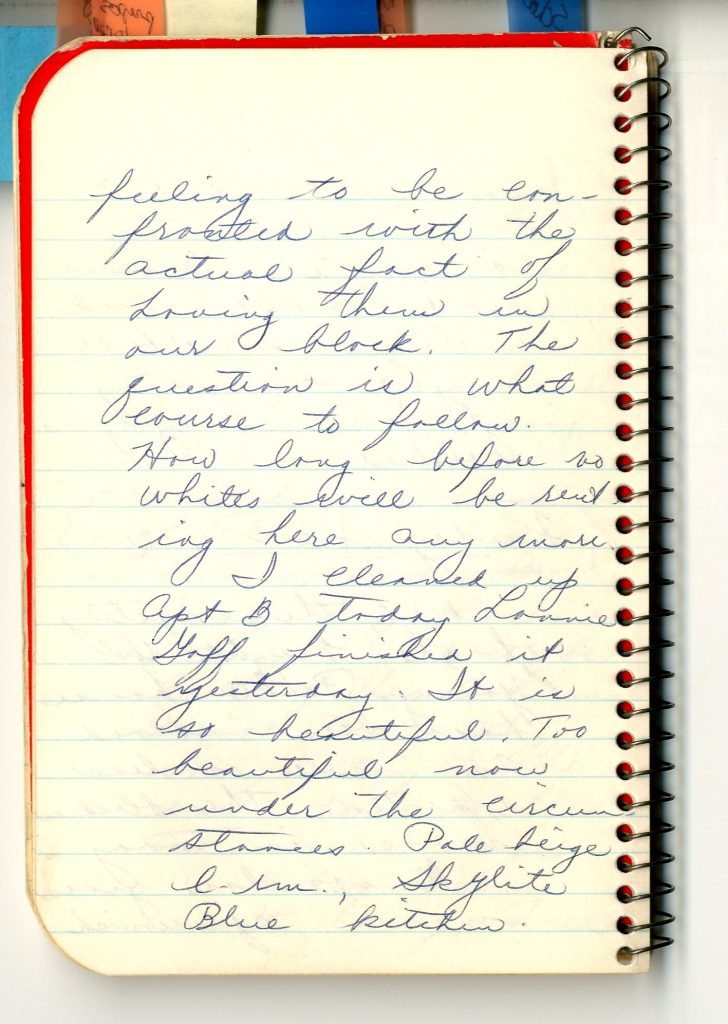

Source 2 – Journal by Lillian Gartz, page 1 and page 2

Examining the Sources

Display or distribute the transcribed sources.

Explain to students that the typed texts are transcriptions of handwritten sources. You may want to review the Skills Lesson: Reading a Transcription.

Explain that when a transcriber is not certain of a word, their best guess is written in brackets followed by a question mark, i.e., “[during?].” And when a transcriber can’t make out a word at all, they indicate this by writing [“illegible”].

If possible, have students read the first two sources and write down their questions and ideas without providing them with any additional information about the authors or the context. Challenge students to note all the information they can glean from each source and formulate questions about it. Then, after reading, discussing, and raising questions about the first two primary sources, provide students with the excerpt from the encyclopedia.

Possible close reading and analysis questions that can be used to spark students’ investigations and group discussions are listed after each source. Questions to prompt comparing and contrasting the first two sources are listed after those sources. Possible questions to use to prompt a synthesis of the information in all the texts are below the questions for the third source.

If you would like your students to work with the sources independently or in small groups, download the Student Worksheet in the Student Worksheet tab or the sources and transcriptions in the Downloads tab. You can also download images of the original documents in the Downloads tab.

Source One – Document by Eunice Lyons Prescott

I live in [West Chesterfield], a small area . . . an hour ride from the heart of the big windy city. This section happens to be the only residential district in this vast city where people of our group have been able to watch their dreams turn into a reality. Previous to the development of this locality it was impossible to acquire a loan for a home due to the fact that Bankers claim that negros allow their property to depreciate to such an extent that they are a bad investment but [during?] the [period?] with the F.H.A. [Federal Housing Authority] in full swing and so many homes being built for other groups a small [group?] of negroes with ideals the chief one being a home worked entirely toward this end and were successful. Here just let me say that I represent no group but am only writing for myself with of course the good will of the [community?] . . . I am of the opinion that better homes make better people and better people are at this time more than ever a necessity to our race [illegible] due to the fact that our money was very limited as we are people in very moderate circumstances and three children to rear and educate. There were many times during this fight that we felt that our dream was to no avail. We have a community here that I can truthfully say without boasting that we are proud of and when people from other communities drive through to gaze and comment on our homes we want them to know that they didn’t just grow but they represent many years of thought planning, [illegible], and hard work.

Eunice Lyons Prescott, date unknown

Questions

Potential Close Reading Questions

- What kind of text is this: a diary entry, a letter, a speech, or something else? Why do you think that?

- Who wrote this? How do you know?

- Where is West Chesterfield? How do you know? How could you find out more about this place?

- Who does the author mean by “people of our group”? How do you know?

- Why couldn’t the people in this group buy houses?

- How does the author feel about owning a house?

- How could you find out approximately when this was written?

- From the context of the text, what do you think the Federal Housing Authority is? Do you need to know the exact purpose of this agency to understand the rest of the text?

- In a sentence or two, what is this text about?

Other Potential Questions

- Is this a primary or secondary source? How do you know?

- What can you determine about the author of this source? How did you come to that conclusion?

- What is the perspective of the author of this source?

- What do you not know about the author? What questions do you have about them?

- Does anything in this source surprise you?

- What questions does this source raise? Where could you find answers to your questions?

Source Two – Journal by Lillian Gartz

Frankly, I think by next spring, if not sooner, all houses west of Parker’s will be colored. . . . Miss McCarthy may stay to the end due to her advanced age. I also believe next May, Fred Jones will sell to colored and the Canersay’s & Brown’s will move. . . .

Lillian Gartz, June 1963

Friday, June 21, 1963

Well, the mystery of who bought the Young-Parker house has been solved as more or less expected, the blackies moved in today. It somehow gives me a squeamish feeling to be confronted with the actual fact of having them in our block. The question is what course to follow. How long before no whites will be renting here any more.

Questions

Potential Close Reading Questions:

- What kind of text is this: a diary entry, a letter, a speech, or something else? What makes you think so?

- Who wrote it? How do you know?

- What can you tell about the author from the source only?

- When was this text written? How do you know?

- What does the author think Miss McCarthy will do and why?

- Who purchased the Young-Parker house? How does the author feel about this?

- What does the author think will ultimately happen to the neighborhood?

- How does the author feel about integration?

Other Potential Questions:

- Is this a primary or secondary source? How do you know?

- What can you determine about the author of this text? How did you come to that conclusion?

- What do you not know about the author? What questions do you have about her?

- Does anything in this source surprise you?

- What questions does this excerpt raise? Where could you find answers to your questions?

Compare and Contrast the First Two Sources

- How are the authors similar and how are they different?

- How are the sources similar and how are they different?

- What differing perspectives do the two authors bring to their texts?

- Were these sources written in about the same time period? Why do you think that?

- Did reading the second source affect your understanding of or reaction to the first? If so, how? If not, why not?

Source Three – Excerpt from the Encyclopedia of Chicago

“Blockbusting” refers to the efforts of real-estate agents and real-estate speculators to trigger the turnover of white-owned property and homes to African Americans. Often characterized as “panic peddling,” such practices frequently accompanied the expansion of black areas of residence and the entry of African Americans into neighborhoods previously denied to them. In evidence as early as 1900, blockbusting techniques included the repeated—often incessant—urging of white homeowners in areas adjacent to or near black communities to sell before it became “too late” and their property values diminished. Agents frequently hired African American subagents and other individuals to walk or drive through changing areas soliciting business and otherwise behaving in such a manner as to provoke and exaggerate white fears. Purchasing homes cheaply from nervous white occupants, the panic peddler sold dearly to African Americans who faced painfully limited choices and inflated prices in a discriminatory housing market. Often providing financing and stringent terms to a captive audience, the blockbuster could realize substantial profits.

Arnold R. Hirsch, “Blockbusting,” Encyclopedia of Chicago

Questions:

- Is this a primary or secondary source? How do you know?

- What questions raised by the other sources does this source answer?

- Does anything in this source surprise you?

- What information does your background knowledge of African American history or the history of Chicago give you about this source?

- What questions does this source raise? Where could you find answers to your questions?

Questions for All Sources:

Do these sources affect your understanding about housing discrimination? If so, how? If not, why not?

How do these sources relate to the civil rights movement?

Does reading these texts raise new questions? Where would you look to find answers to your questions?

Background

Source One

Source One is from the Prescott Family Papers at the Newberry Library. It was written by Eunice Lyons Prescott, probably in the late 1940s or early 1950s. Prescott was a Black woman born in Austin, Texas, where her grandfather and father were community leaders and ran a grocery store. With her mother, two sisters, and a brother Eunice migrated to Chicago sometime around 1919. In 1923, she married James Connor Prescott who had migrated with his family to Chicago from New Orleans, also around 1919.

Eunice Prescott was a hat maker, running a successful millinery store in Chicago. James Connor Prescott worked for the post office, “throwing the mail” (i.e., sorting.) They were solid members of the Black middle class in Chicago and lived for many years in the Michigan Boulevard Garden Apartments, also known as the Rosenwald Apartments, an apartment building for African Americans located at 47th Street and Michigan Avenue in the Bronzeville neighborhood. In the 1940s, they purchased land and built their own home at 9240 S. Michigan Ave. in the newly developing neighborhood of West Chesterfield. According to family sources, the area was farmland at the time. West Chesterfield is now part of the Chatham Neighborhood.

Source Two

Source Two is from a diary by Lillian Gartz in the Gartz Family Papers at the Newberry Library. The collection was donated by Linda Gartz who wrote the book Redlined: A Memoir of Race, Change, and Fractured Community in 1960s Chicago (2018).

The Gartz family settled in West Garfield Park, Chicago around 1910. Like Eunice Prescott’s family, Lillian Gartz’s parents ran a grocery store. The Gartz family lived in West Garfield Park as the all-white, mostly European immigrant community in Chicago changed to an all-African-American community through discriminatory housing policies like blockbusting. Despite the fears described in the diary entries in this lesson, Lillian Gartz and her husband Fred chose to stay in the neighborhood and ultimately overcame their prejudices and befriended their new neighbors.

Source Three

While the other two texts are primary sources, this is a secondary source taken from the Encyclopedia of Chicago, a joint effort of the Newberry Library, the Chicago History Museum, and Northwestern University. The author, Arnold R. Hirsch, was a historian who looked closely at segregation in housing. Hirsch wrote Making the Second Ghetto: Race and Housing in Chicago, 1940-1960.

Housing Discrimination in Chicago

From the early 1900s through the 1960s and beyond African Americans were confined to small areas of Chicago, even as their population increased. On the South Side of the city an area called the “Black Belt” developed where African Americans were allowed to live. Originally the Black Belt was confined to a narrow strip on either side of State Street from 22nd to 31st Street. As the Great Migrations brought more African Americans to the city, the Black Belt expanded until it reached north to south from 39th Street to 95th Street and east to west from the Dan Ryan Expressway to Lake Michigan. Other predominantly Black areas also developed on the West Side of the city.

Blockbusting occurred when real estate investors fed the fears of white property owners about Black migration into a neighborhood or onto a street. Real estate investors would build upon the prejudices of white owners and convince them that the value of their properties would drop if any Black family arrived. When white families decided to move, these same investors would purchase their properties at drastically reduced prices, only to turn around and sell them at inflated rates to families of color wanting to move in.

Redlining started with banks and insurance companies denying African Americans mortgage loans or insurance coverage no matter their financial status. The New Deal’s Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) further codified this practice during the Great Depression by creating color-coded maps of U.S. cities where Black and poor neighborhoods were outlined with a red line, indicating that the neighborhood was high risk or undesirable. Banks, developers, realtors, and insurance companies began using these maps to define where they would and would not provide services. The Federal Housing Authority also used these maps to determine where they would and would not federally insure new housing developments.

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 outlawed lending discrimination, including redlining, and banned investors and others from claiming that non-white residents would lower a neighborhood’s real estate values, but the effects of these practices still impact communities today. Formerly redlined neighborhoods are often food deserts (places with little access to grocery stores or fresh food) and often have less funding for schools, housing, and infrastructure like roads and water pipes. Housing discrimination also deepened the racial wealth gap in the US and contributed to the racial segregation that still exists in many US cities.

Extension Activities

- Continue the Discussion: Recently a great deal of information about redlining and blockbusting has been researched and published, especially about the practice in Chicago. Reading/watching and then discussing the groundbreaking article by Ta-Nehisi Coates and/or an upcoming five-part series on the subject are two great extension activities for more advanced students. Students can also interact with redlining maps through a University of Richmond project, read original descriptions of neighborhood ‘desirability,’ and look for their own or well-known neighborhoods.

- “The Case for Reparations”, Ta-Nehisi Coates, The Atlantic, June 2014

- The Shame of Chicago, documentary series, Bruce Orenstein and Chris L. Jenkins

- Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America, University of Richmond Digital Scholarship Lab.

- Do an oral history project: Ask students to talk to older family members and neighbors to see if they have memories about their neighborhood and how it has changed

Additional Resources

About Blockbusting and Redlining:

- “Blockbusting,” Encyclopedia of Chicago

- “Redlining,” Encyclopedia of Chicago

- “Redlining: The Jim Crow Laws of the North,” PBS

- “Study: Effects of Redlining in Chicago and Suburbs Continue to Perpetuate Blight in Many Communities,” CBS Chicago

About Chicago Neighborhoods:

- “West Garfield Park,” Encyclopedia of Chicago

- “Rosenwald Court Apartments,” Wikipedia

- “Chatham,” Encyclopedia of Chicago

At the Newberry:

- Gartz Family Papers, Newberry Library

- Prescott Family Papers, Newberry Library

Words to Know

Transcription │ the typed text of a handwritten document or an audio recording

Download the Blockbusting student worksheet below.

Download copies of the Blockbusting lesson plan and transcripts of the sources used in the lesson below.