Themes

Economics

Indigenous Studies

Westward Expansion

Periods

19th Century

US Civil War

Skills & Document Types

Bank Notes

Image Analysis

Visual Literacy

This activity is intended for middle school students and is less advanced than the accompanying lesson plan.

Materials – Documents Available for Download in the Downloads Tab:

- Optional: Computer and projector

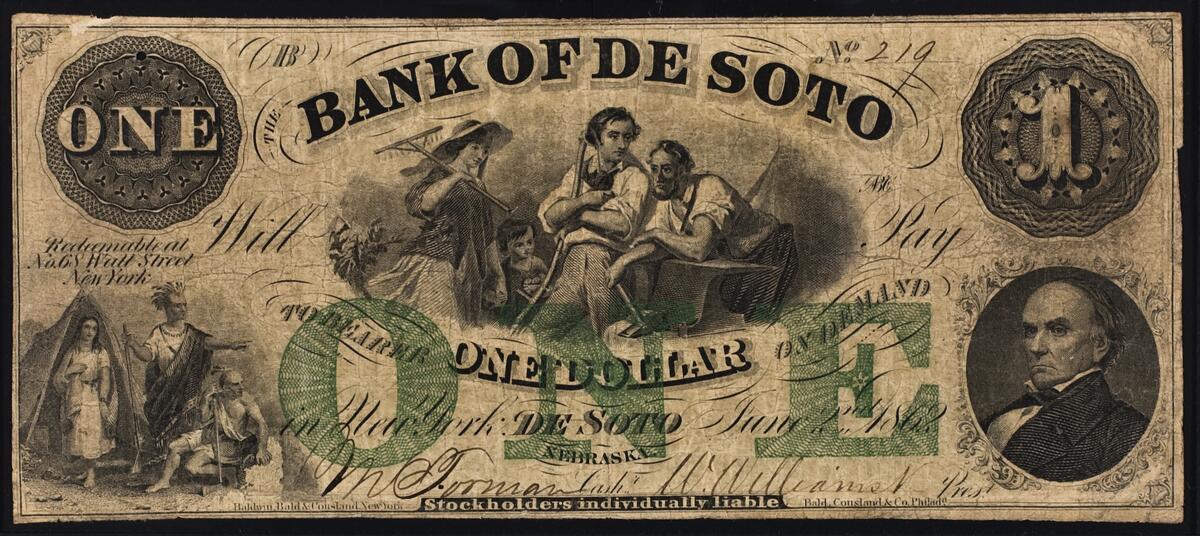

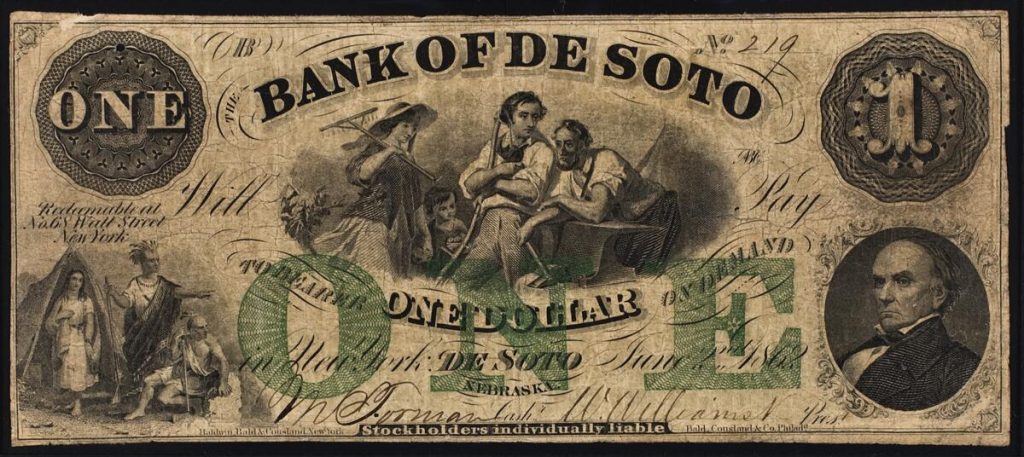

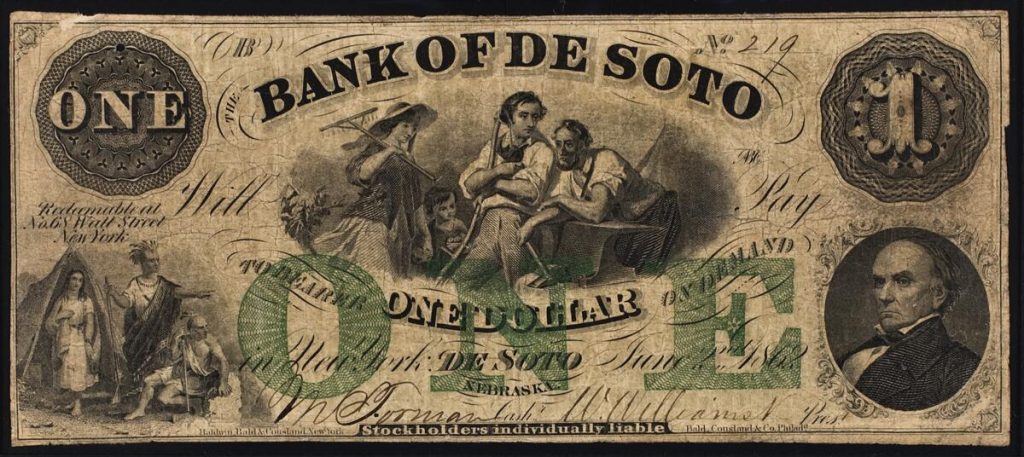

- Copy of the bank note used in this activity (high-resolution version here)

- Space for students to generate questions

Intro

This activity is a way to provide a lesson on visual literacy within a history curriculum as well as an introduction to or exploration of currency. You may want to begin with the Skills Lesson: Ephemera.

Process

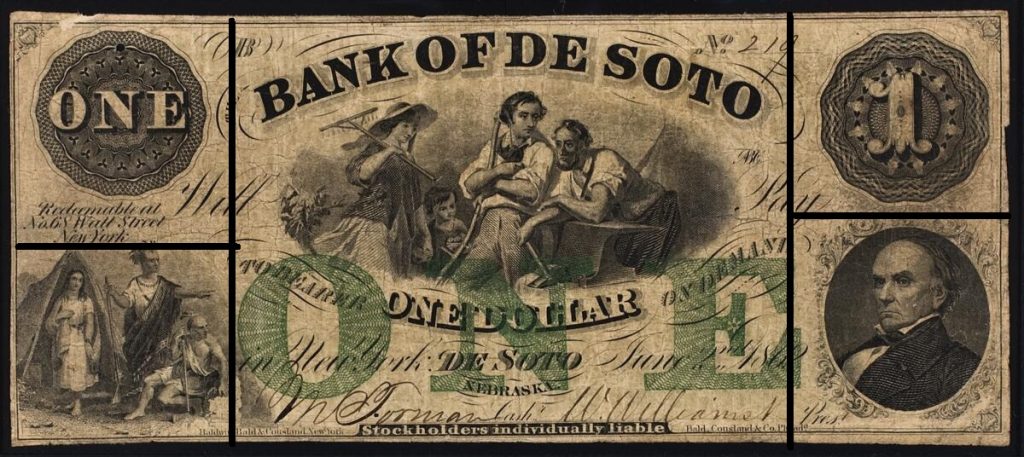

Display the image. Give students time to generate and answer questions about the object and write notes. Use the background material at the end of this activity whenever you think it will encourage students to ask more questions and think more about how to engage with the object.

Or add grid lines to the object to help students focus on different sections, like this:

Potential Questions

- What numbers can you find? What do they mean? (The number one is shown. It shows how much the bank note is worth. The number 1862 is a year.)

- What words are on the object? What do they tell you about it? (Words include Bank of De Soto, will, pay, to bearer, one dollar, on demand; in New York; June 2, 1862; redeemable at No. 68 Wall Street New York, De Soto, Nebraska; Stockholders individually liable)

- Who made this? How do you know? (Bank of De Soto because that is the name written on the object.)

- When was this made? How do you know? (1862 because the date is written on the object)

- What is this object? (a bank note)

- What is pictured at the center? What are the people holding? What does that tell you about the people and what they do? (men, a woman, a child; They are holding a rake, a scythe, and a hammer and one man is leaning on an anvil; this shows that they are farmers and a blacksmith.)

- Who is shown in the lower left corner? (Native Americans)

Notes for the teacher:

- Students might be confused by the references to New York. Help them understand that Bank of De Soto was the issuer, while the cash reserves backing the bank notes were presumably held that this address in New York.

- The image on the lower right is Daniel Webster, who died in 1852. He was a nationally known orator and supporter of the idea of a national bank.

Discussion

What do the images on the money tell you about De Soto, Nebraska?

(Possible conclusions: The center illustration shows that farming was important in the area and to the economy. The people who use the bank are farmers and people who help farmers like blacksmiths. The picturing of Native Americans might be because the US was in the process of forcing Native peoples off their homelands; Native Americans can also represent or symbolize the United States or the land itself. The woman and child show that the area was friendly for families; show that many families with children lived there.)

Background

Paper Currency People have been using metal coins as currency for millennia. In early America the British did not send enough minted coins to the colonies, so paper notes were used to fill that gap. The first national paper currency in the United States were $2 bills called “Continentals.” During the Early Republic era, the First and Second Banks of the United States issued private bank notes. However, from the closure of the Second National Bank in 1836 to the Civil War, there were no national bank notes. During the Civil War, the US Treasury began to print national bank notes, and in 1913 the Federal Reserve also began printing national bank notes. From 1913 to 1971 both US and Federal Reserve (a national banking system backed up by bonds) notes were in circulation. In 1971 US notes stopped being printed. Today all US currency is Federal Reserve notes.

Through the Civil War and for some years afterwards, local private banks could also issue bank notes. This currency was meant to be used locally, especially in areas where there was a lack of silver and gold coins and other currency in small denominations. In new US territories, these private bank notes helped local economies. The notes were backed up by the money the bank had on deposit.

A major problem with paper currency of all kinds was that it could be counterfeited easily, losing value as a result. Currency printers developed elaborate illustrations and used different inks to make counterfeiting more difficult. Another risk was the lack of regulation. Local banks often printed more notes than they could convert to coin, causing a bank to go bankrupt when people tried to exchange their notes for gold or silver during a financial panic. And panics in nineteenth-century America were frighteningly common. The most famous are the Panics of 1819, 1825, 1837, 1857, 1873, 1893, and 1896.

Throughout history, currency has incorporated imagery, symbolism and allegorical figures. On US paper currency allegorical figures have included female figures representing liberty, justice, history, agriculture, commerce, and the United States, among others.

Territorial Banking In Nebraska, banks had to be authorized by the legislature. It was not difficult to get authorization, though, and those banks were allowed to issue their own bank notes. These bank notes were called “wildcat notes” and their value changed often. Counterfeiting was a major problem. After the land boom ended and the Panic of 1857 hit, many of the banks failed and the bank notes they had issued became worthless.

De Soto, Nebraska was a boom town founded in 1855, and from 1858 to 1866 it was the center of government for Washington County. At its height, the town had three banks—the first was the De Soto Bank—as well as hotels, stores, and newspapers. The town hoped to become a transportation hub, first for ferries and steamships on the Missouri and then for the railroad. When these dreams failed to be realized the town began to disappear. Today, no town buildings still exist, but about three farms do.

Extension Activities

- Have students look up and examine more examples of currency from the Everett D. Graff Collection of Western Americana.

- What are the most common images on the currency in this collection? What does that say about the American West in this period?

- Have students look up currencies from around the world and from different points in history and create a museum exhibit that explains their favorite currencies and what the images on those currencies tell us about the societies that created it.

Additional Resources

- The History of U.S. currency, US Currency Education Program

- Banks Own Private Currencies in 19th-Century America, JStore Daily

- A Brief (and Fascinating) History of Money, Encyclopedia Britannica

- De Soto Townsite, History Nebraska

Words to Know

Ephemera │ a variety of paper and other objects that were created but not meant to be saved

Counterfeit | something that is made to look like something else with the intention to deceive

Redeem │ to turn in for a payment of equal value

Issue | print for public use

Themes

African American Studies

Economics

Indigenous Studies

Westward Expansion

Periods

19th Century

US Civil War

Skills & Document Types

Bank Notes

Image Analysis

Visual Literacy

This lesson is intended for advanced middle school students and early high school students and is more advanced than the accompanying activity.

Materials – Documents Available for Download in the Downloads Tab:

- Optional: computer and projector

- Copies of the bank notes used in this lesson

- High resolution versions of Newberry Library and Confederate bank note

- Student worksheet

Intro

You and your students are going to examine some ephemera. Help students understand that these objects reveal something about the place and time they were created. You may want to begin with the Skills Lesson: Ephemera.

Questions follow each of the objects. The questions are designed to help students examine each source carefully and to flow from one source to the next. You can choose among the questions depending upon the length and depth of the lesson you want to present.

Background information about currency in the United States in the mid-nineteenth century can be found at the end of the lesson, along with vocabulary and links to additional sources and ideas for extension activities.

Process

Display or distribute copies of the banknotes. If possible, have students examine the objects and write down their questions and ideas about them without any captioning or additional information.

After students have examined the first three sources without any information, provide them with captions and, as necessary, background information on currency. Then display or distribute Source 4 and engage students in comparing the first three with the last.

If you would like your students to work with the sources independently or in small groups, you can access the Student Worksheet in the Downloads tab above.

Display Source 1

Click on the image for a high-resolution version that can be displayed for your class.

Looking Closely Questions

To help students examine the object closely and carefully, ask:

- What numbers can you find? What do they mean? (The number one is shown. It shows how much the bank note is worth. The number 1862 is a year.)

- What words are on the object? What do they tell you about it? (Words include Bank of De Soto, will, pay, to bearer, one dollar, on demand; in New York; June 2, 1862; redeemable at No. 68 Wall Street New York, De Soto, Nebraska; Stockholders individually liable)

- Who made this? How do you know? (Bank of De Soto because that is the name written on the object.)

- When was this made? How do you know? (1862 because the date is written on the object.)

- Based on all this information what is this object? (This object is a “bank note,” a piece of currency.)

- What is pictured at the center of the bank note? What are they holding? How can what they are holding tell you about what they do and who they are? (men, a woman, a child; They are holding a rake, a scythe, and a hammer and one man is leaning on an anvil; this shows that they are farmers and a blacksmith.)

- What is shown in the lower left corner? (Native Americans)

- Is this a primary or secondary source? How do you know? (This is a primary source because it is an original piece of ephemera.)

Note to teachers: Students might be confused by the references to New York. Help them understand that Bank of De Soto was the issuer, while the cash reserves backing the bank notes were presumably held that this address in New York.

Generating Discussion

These questions might help students move from observation to analysis:

- What do the illustrations tell you about the area where this currency was issued? What was important to the economy in this area? How did people make their money? (The center illustration shows that farming was important in the area and to the economy. The people who use the bank are farmers and people who help farmers like blacksmiths. Indigenous people might be pictured because the US was still in the process of forcing them off this land; the Indigenous people here represent or symbolize the United States or the land itself.)

- What do you know about Nebraska in 1862 that might help you understand this object? (It was just being settled by European Americans; Indigenous peoples still controlled much of the West; it was still a territory; it was part of Westward Expansion)

- Why were a woman and child depicted along with two men in the top illustration? (To show that the area was friendly for families; to show that many families with children lived there)

- Does anything about this object surprise you?

- What do you not know about this object? What questions do you have? Where could you find answers to your questions?

Note to teachers: The image on the lower right is Daniel Webster, who died in 1852. He was a nationally known orator and long-time supporter of the idea of a national bank.

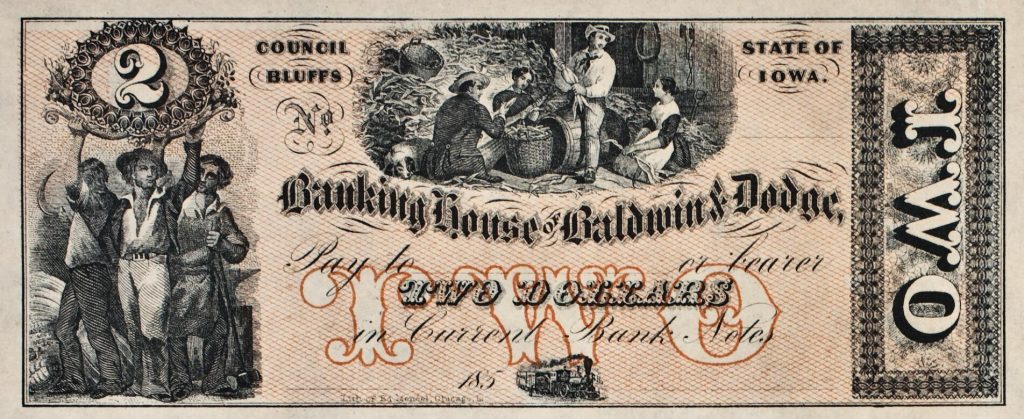

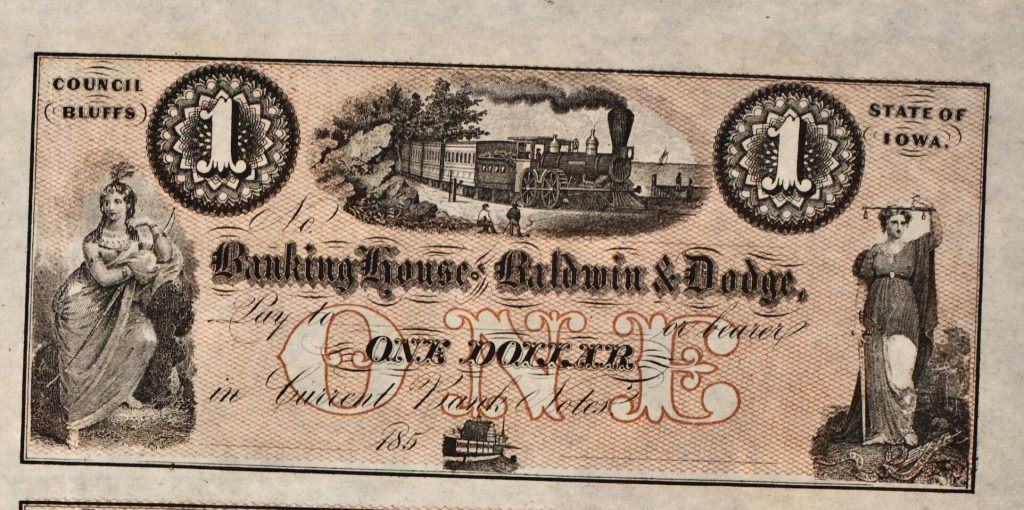

Displace Sources 2 and 3

Click on the image for a high-resolution version that can be displayed for your class.

Click on the image for a high-resolution version that can be displayed for your class.

Looking Closely Questions:

To help students examine the objects closely and carefully, ask:

- What numbers can you find? What do they mean? (The numbers shown are one and two. These numbers show how much the bank note is worth. The numbers “185” are part of a year.)

- What words are written on this object? What do they tell you about it? (Words include Council Bluffs, State of Iowa, pay to, [blank space] or bearer, one [two] dollar[s], in current bank notes.)

- Who made these objects? How do you know? (Baldwin and Dodge Bank because that is the name written on the objects.)

- When were these objects made? How do you know? (In the 1850s because 185_ is written on the object.)

- Based on all this information what is this object? (This object is a “bank note,” a piece of currency.)

- What is pictured on each bank note? Look for as many details as you can. (people shucking corn, men holding up the number two, an Indigenous woman [perhaps representing the continent of America or the United States], a train, a female figure holding scales and a sword [perhaps representing Lady Liberty or Justice], a building [at the bottom of the $1 bill, very hard to make out].)

Generating Discussion:

These questions might help students move from observation to analysis:

- What was an important crop at this time? How do you know? (corn; because the illustration shows farmers shucking corn)

- Why would the bank put this picture on a note? (Farming was important in Iowa.)

- What does the illustration on the left side of the top note show? (Men holding up the number “2”) What does this symbolize? (Working men are holding up, or are making sure, the money doesn’t fall or lose value; The local people support the bank; The money is good and safe to use.)

- What is one image shown on both notes? (a train) What does that reveal? (That the railroad was important to the economy)

- Do these sources answer any of your questions? Do they inspire new questions?

- Does anything about these objects surprise you?

- What do you not know about these objects? What questions do you have? Where could you find answers to your questions?

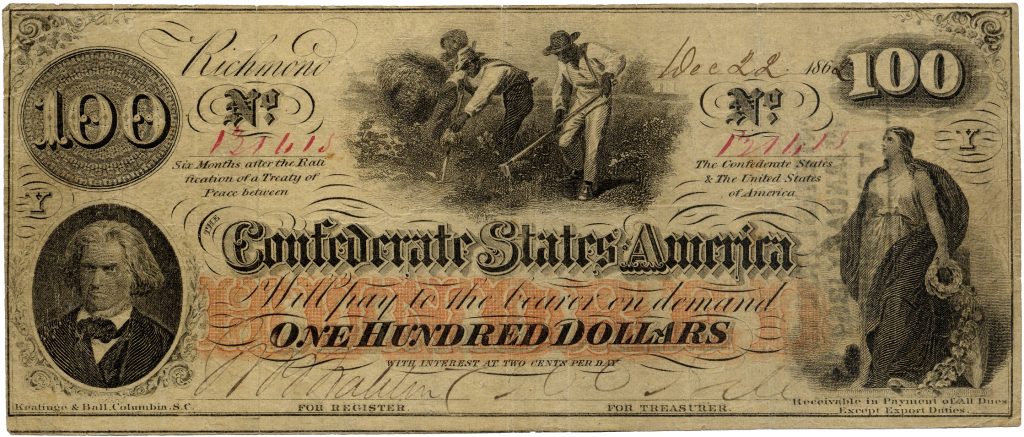

Display Source 4

Click on the image for a high-resolution version that can be displayed for your class.

Looking Closely Questions:

To help students examine the object closely and carefully, ask:

- What is this object? (It is a bank note, a $100 bill.)

- Who issued this bank note? (The Confederacy.)

- When and where was this made? How do you know? (December 22, 1862, Richmond; The date and city are both written on the bill.)

- What is the text on the object? (Six months after the ratification of a Treaty of Peace between the Confederate States of America & The United States of America The Confederate States of America will pay to the bearer on demand one hundred dollars with interest at two cents per day; Receivable in Payment of all Dues Except Export Duties.)

- What does the text tell you about this note? Could someone turn in this note during the war and get $100 plus interest in silver coin? (This means that the bill couldn’t be exchanged for gold or silver until after the war was won by the Confederacy.)

- Who is pictured at the top center of the bank note? (enslaved Black people hoeing cotton)

Generating Discussion:

These questions might help students move from observation to analysis:

- What does the main image on this bank note tell you about what was important to the economy of the government that issued this note? (The picturing of enslaved people on the note shows that slavery was important to the economy of the Confederacy.)

- How do the images on this bank note differ from and how are they similar to the previous bank notes we have examined? (All the bank notes showed people farming, which shows that agriculture was important to both economies. But the bank notes from Iowa and Nebraska show white, free families while the bank note from the Confederacy shows three enslaved men. This shows the different agricultural systems in the two regions. The Confederate bank note also does not show a train. This could be because rail lines were more essential to the development of western territories and the North. There were fewer railroads in the South at this time and railroads were less important to the Confederate identity.)

- Did this source answer any of your questions? Does it inspire new questions?

- Does anything about this source surprise you?

- What do you not know about this source? What questions do you have? Where could you find answers to your questions?

Background

Currency: People have been using metal coins as currency for millennia. In early America the British did not send enough minted coins to the colonies, so paper notes were used to fill that gap. The first national paper currency in the United States were $2 bills called “Continentals.” During the Early Republic era, the First and Second Banks of the United States issued private bank notes. However, from the closure of the Second National Bank in 1836 to the Civil War, there were no national bank notes.

During the Civil War, national bank notes again appeared on the scene. Both the Union and the Confederacy began printing their own paper currency. The Union notes were “United States notes.” In 1913 the Federal Reserve (a national banking system backed up by bonds) was created and also began printing national bank notes. From 1913 to 1971 both US and Federal Reserve notes were in circulation. In 1971 US notes stopped being printed. Today all US currency is Federal Reserve notes.

Through the Civil War and for some years afterwards, local private banks could also issue bank notes. This currency was meant to be used locally, especially in areas where there was a lack of silver and gold coins and other currency in small denominations. In new US territories, these private bank notes helped local economies. The notes were backed up by the money the bank had on deposit, meaning anyone with a valid bank note could present it to the bank that printed it and demand its value in gold or sometimes silver.

A major problem with paper currency of all types was that it could be counterfeited easily, losing value as a result. Currency printers developed elaborate illustrations and used different inks to make counterfeiting more difficult. Another risk was the lack of regulation. Local banks often printed more notes than they could convert to coin, causing a bank to go bankrupt when people tried to exchange their notes for gold or silver during a financial panic. And panics in nineteenth-century American were frighteningly common. The most famous are the Panics of 1819, 1825, 1837, 1857, 1873, 1893, and 1896.

Throughout history, currency has incorporated imagery, symbolism and allegorical figures. On US paper currency, allegorical figures have included female figures representing liberty, justice, history, agriculture, commerce, and the United States, among others.

Territorial Banking: In Nebraska, banks had to be authorized by the legislature. It was not difficult to get that authorization, though, and those banks were allowed to issue their own bank notes. These bank notes were called “wildcat notes” and their value changed often. Counterfeiting was a major problem. After the land boom ended and the Panic of 1857 hit, many of the banks failed and the bank notes they had issued became worthless.

De Soto, Nebraska: A boom town founded in 1855. From 1858 to 1866, it was the center of government for Washington County. At its height, the town had three banks—the first was the De Soto Bank—as well as hotels, stores, and newspapers. The town hoped to become a transportation hub, first for ferries and steamships on the Missouri and then for the railroad. When these dreams failed to be realized the town began to disappear. Today, no town buildings still exist, but about three farms do.

Baldwin and Dodge Bank: The Baldwin and Dodge bank and land agency opened in Council Bluff, Iowa, in January 1856. The notes issued by this bank went out of use when the State Bank of Iowa was founded in 1859.

Extension Activities

- Have students examine modern US currency (front, back of the $1 bill) and compare it to the currency in the lesson.

- What is different and what is similar?

- What is the “Federal Reserve” on the $1 bill?

- For an excellent exploration of the symbolism of U.S. currency, go to Symbols on American Money.

- Have students look up and examine more examples of historic currency from the Newberry’s collection.

- What are the most common images on the currency in this collection? What do they tell you about the American West in this period?

- Have students look up currencies from around the world and from different points in history and create a museum exhibit that explains their favorite currencies and what the images on those currencies tell us about the societies that created them.

Additional Resources

- The History of U.S. currency, U.S. Currency Education Program

- Private Money in our Past, Present, and Future, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland

- Banks Own Private Currencies in 19th-Century America, JStore Daily

- The Secret Art History on Your Money, New York Times

- A Brief (and Fascinating) History of Money, Encyclopedia Britannica

- De Soto Townsite, History Nebraska

- Two Dollar Bank of De Soto Note, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institute

- Council Bluffs, Iowa, Wikipedia

Words to Know

Ephemera │ a variety of paper and other objects that were created but not meant to be saved

Counterfeit | something that is made to look like something else with the intention to deceive

Redeemed │ to turn in for a payment of equal value

Issued | printed for public use

Download the following materials below:

- A copy of the activity “Nineteenth-Century Currency”

- A copy of the lesson “Nineteenth-Century Currency”

- Copies of the sources used in the activity and the lesson

- Student worksheets for the activity and the lesson