While many people conflate the Arctic and Antarctic, these regions are quite distinct, having wildly different histories, different environments, and different systems of government and management. For example, walruses and polar bears are not found in the Antarctic, and penguins are not found in the Arctic. The Arctic generally comprises lands surrounding an ice-covered ocean, and the Antarctic is an ocean surrounding ice-covered lands. Arctic territory exists in in several sovereign countries like Denmark, the United States, Russia, and more. While seven countries have made territorial claims in Antarctica, the continent is governed through the Antarctic Treaty System, which does not allow enforcement of any of these claims.

Likely the most important difference, of course, is that while Indigenous people have lived and travelled throughout the Arctic for thousands of years, the human presence in Antarctica is much more recent. Māori (the Indigenous people of New Zealand) oral histories suggest that as early as the seventh century, the Polynesian explorer Ui-te-Rangiora could have traveled as far south as the Ross Sea, but documented human exploration of the Antarctic did not begin until the late eighteenth century. The continent was not discovered until 1820. Today, many people, both Indigenous and settlers, make their homes in the Arctic, while people travel to Antarctica only temporarily — to visit as a tourist, to conduct scientific research, or to support the research stations that dot the continent.

Yet despite these differences – and literally being polar opposites on the globes – the two regions do have so much in common that research collections like the Gerald F. Fitzgerald Collection at the Newberry Library, collections that combine the Antarctic and the Arctic, are not unusual. There are a few reasons for this. First, Europeans and white North Americans explored both regions in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a period when imperialism and colonialization by many European countries, as well as the United States and Japan, was at its zenith. Second, this period also coincided with the vast expansion of industrialization and globalization that demanded raw resources, some of which were plentiful in both polar regions. Finally, many people associated the two regions together as they are both cold, dry, and covered with ice and snow.

Fascination with the two regions among both the public and scientists also led to an explosion of publications documenting travel in these regions. These publications detailed the people (in the case of the Arctic), fauna, and landscapes of the polar regions, which were new to an audience of mostly white readers. There was a similar explosion of more literary works that introduced readers to these parts of the globe in attention-grabbing ways. This new polar literature in the nineteenth century included works by famous writers such as Edgar Allen Poe, Mary Shelley, William Coleridge, James Fenimore Cooper, and Jules Verne. Furthermore, it was not uncommon for European and white North American men to join expeditions to both of these regions to try to make names for themselves. Men such as Roald Amundsen, Richard Byrd, and James Clark Ross, all of whom you will read about in these essays, wrote extensively about their travels in both regions, often emphasizing their geographical discoveries and the heroism and endurance needed for polar travel. Finally, scientific interest in the biology, geology, anthropology, and other subjects related to both regions led to an increase in scientific publications and inquiries that tried to determine whether major scientific questions could be answered through travels in Antarctic and the Arctic.

The following essays are historical narratives that explore three different themes in polar history. Each of these essays address histories that are important to both the Arctic and Antarctic regions: science, resource extraction, and the exploitation of Indigenous people. These stories are only three examples of many that could be told about the history of polar regions using the resources in the Newberry Library. Perhaps, after reading these essays, you will be prompted to explore polar history further and write a history of your own.

Questions for Discussion:

- Look at a map of the world. What are the eight Arctic states (the eight countries whose territory overlaps with the Arctic region)? Both the United States and Denmark are Arctic states despite their Arctic territories being disconnected from their mainland. What does this tell you about Arctic history?

- Look at a map of the world. What seven states do you think have territorial claims in Antarctica? Why? Now look up these countries to find the answers and see if these countries match your guesses. Are there any that surprised you? Why or why not?

- Before 1940, only the following countries had sent expeditions to Antarctica: Great Britain (including Australia, New Zealand, and Scotland), Russia, France, Belgium, Japan, France, Germany, Norway, Sweden, and the United States. What did these countries have in common? Are you surprised by any of the countries on this list?

About the Author

Daniella McCahey is a historian whose research focuses on the history of science and exploration in Antarctica. Since she completed her PhD at the University of California, Irvine, she has published widely on this topic and is the co-author (with Jean de Pomereu) of Antarctica: A History in 100 Objects (Conway, 2022). Her work generally seeks to draw the Antarctic into larger conversations and themes in world history such as imperialism, science, the environment, geopolitics, culture, and gender relations, among others. Her professional goal to make people realize that Antarctic history is human history, and therefore deeply connected to the histories of the rest of the world. She is currently an assistant professor in the History Department at Texas Tech University, in Lubbock, TX, where she mainly teaches classes on the history of the British Empire and the history of modern science.

Indigenous Technology and White Polar Explorers

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, many European and American scientists and political and military leaders became increasingly interested in learning more about the Arctic and Antarctic regions. However, these regions were initially unknown and even alien territories to most of these (mostly) white men. So, to venture into these regions, polar explorers increasingly depended on help from the Indigenous people of the Arctic, drawing on their expertise as guides, scouts, and hunters, and using and adapting their technologies and survival skills for living and traveling in these regions. Before long, these Indigenous technologies had become some of the standard tools of exploration for white travelers engaged in polar exploration.

In this essay, you will learn about three primary examples of tools for traveling in polar environments that were invented by Indigenous Arctic peoples and then used by white Americans and Europeans as they “explored” polar regions: snow goggles, dogsleds, and boots. As such, this essay focuses on white North American and European perspectives on Indigenous technologies, rather than on the Indigenous development of these technologies. You will see a contradiction between men who, on one hand, viewed Indigenous peoples as primitive and backwards, but on the other hand, accepted that these same people had mastered survival in polar environments. When white North American and European men made achievements in the Arctic and Antarctic – like being the first humans to reach the North and South Poles, for example – they often did so based on knowledge that they had taken from Indigenous people. This meant that even though these “explorers” often owed their lives to Indigenous peoples, they rarely shared credit for their geographical discoveries with them. Instead, they frequently praised themselves for having the foresight to borrow aspects of Indigenous culture that they saw to be useful. Instead of acknowledging Indigenous ingenuity, most white Europeans and North Americans believed it was their own ability to recognize useful technologies that made them good explorers.

These white explorers had differing relationships with Indigenous technologies. Sometimes, especially in the Arctic, they acquired these tools directly from Indigenous people, receiving as gifts, buying, trading for, and even seizing clothing and tools by force. Sometimes white explorers tracked down the raw materials used to make this gear and copied it to the best of their ability. And sometimes, they would try to “improve” on Indigenous technologies, with varying degrees of success.

As a warning, this section contains quotations from historical writings published in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. At this time, it was common practice for Europeans and white Americans to refer to Indigenous people of the North American Arctic as “Eskimo,” a term that today is widely considered offensive by the Yup’ik (YOO-pick), Iñupiat (uh-NYOO-pee-ak), Kalaallit (KAH-lah-lit), and Inuit (IN-yuu-uht) people who make up the Indigenous communities of Arctic Canada, Alaska, and Greenland. For more on why libraries like the Newberry preserve items with offensive language, see the Newberry’s Statement on Potentially Offensive Materials.

Snow Goggles

One of the most common medical ailments associated with visiting the polar regions is snow-blindness. Snow-blindness describes the burns on the corneas, the outermost layers of the eye, when the eyes are exposed to the sun’s ultraviolet light for too long without protection. The intense light that comes from the reflection of sunlight off of snow and ice makes snow-blindness especially common for people traveling in the Arctic and Antarctica. Snow-blindness is both debilitating and extremely painful. For white North American and European men traveling in polar environments, it was a very persistent ailment. Note British explorer Ernest Shackleton’s account of the disease: “Snow-blindness…is a very painful complaint. The first sign of the approach of the trouble is running at the nose; then the sufferer begins to see double, and his vision gradually becomes blurred. The more painful symptoms appear very soon. The blood vessels of the eyes swell, making one feel as though sand had got in under the lids, and then the eyes begin to water freely and gradually close up. The best method of relief is to drop some cocaine into the eye, and then apply a powerful astringent, such as sulphate of zinc, in order to reduce the distended blood vessels.”1 Cocaine was a common medication for pain relief in the early twentieth century.

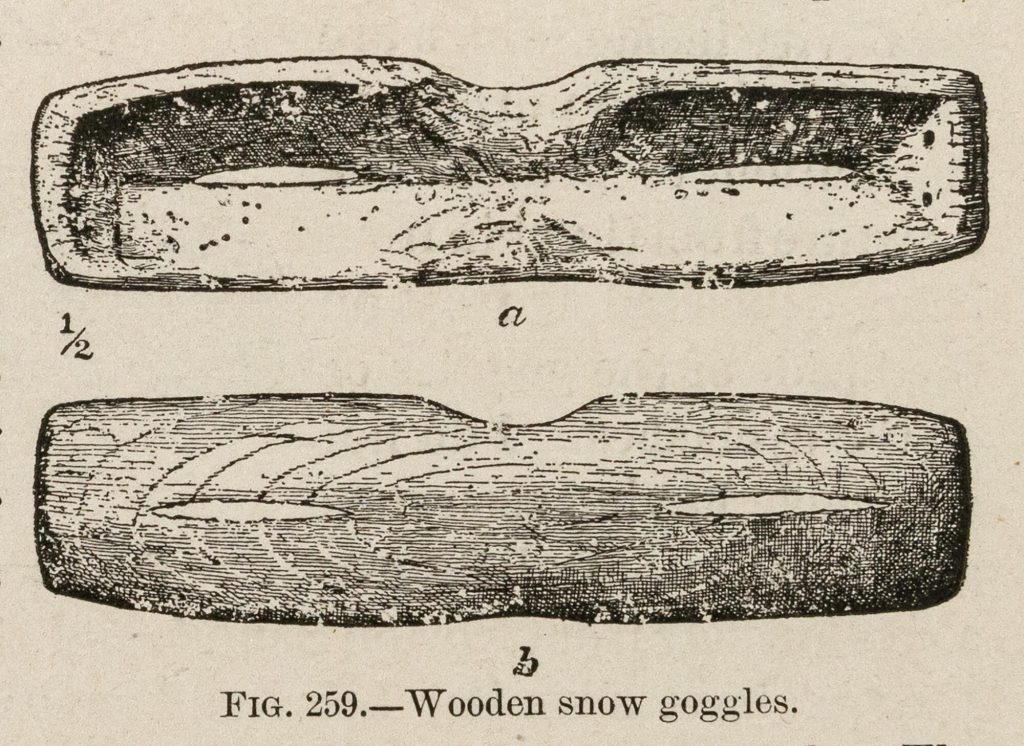

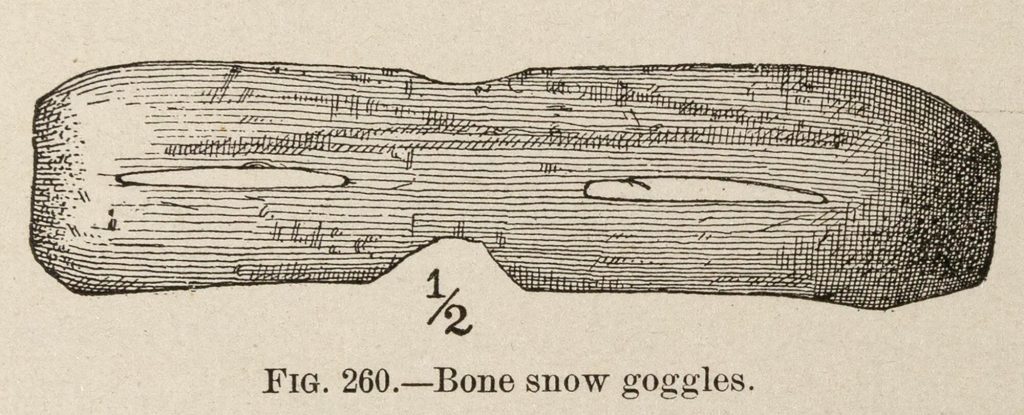

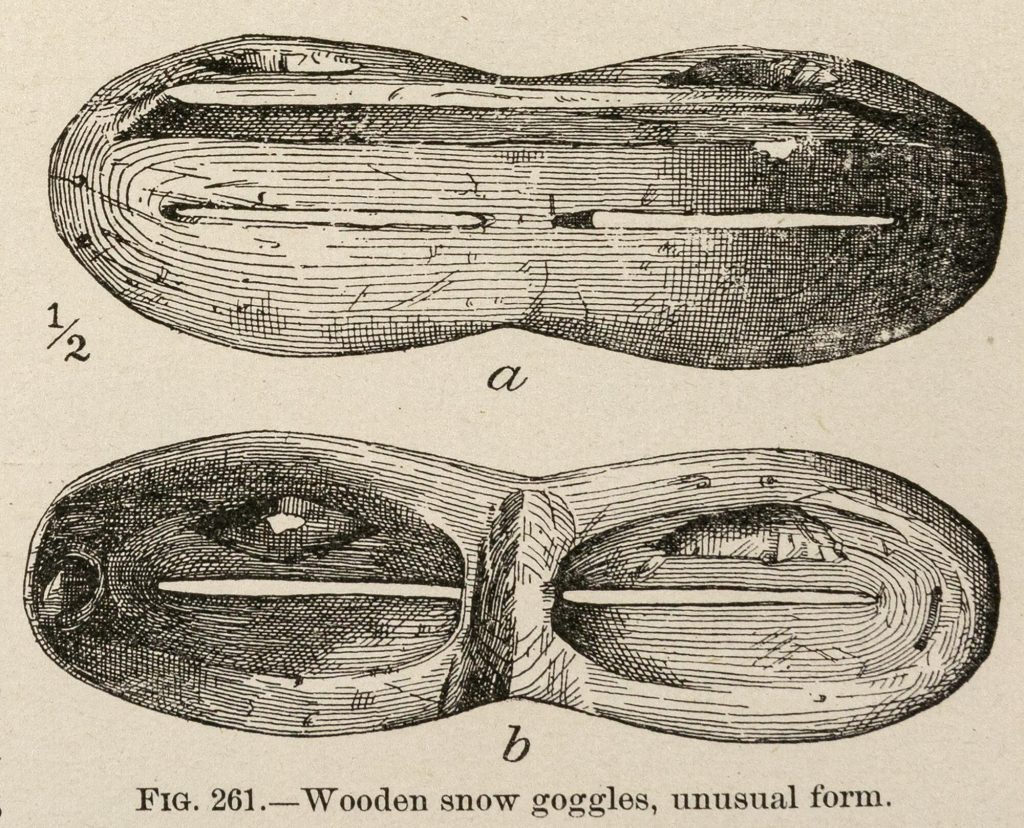

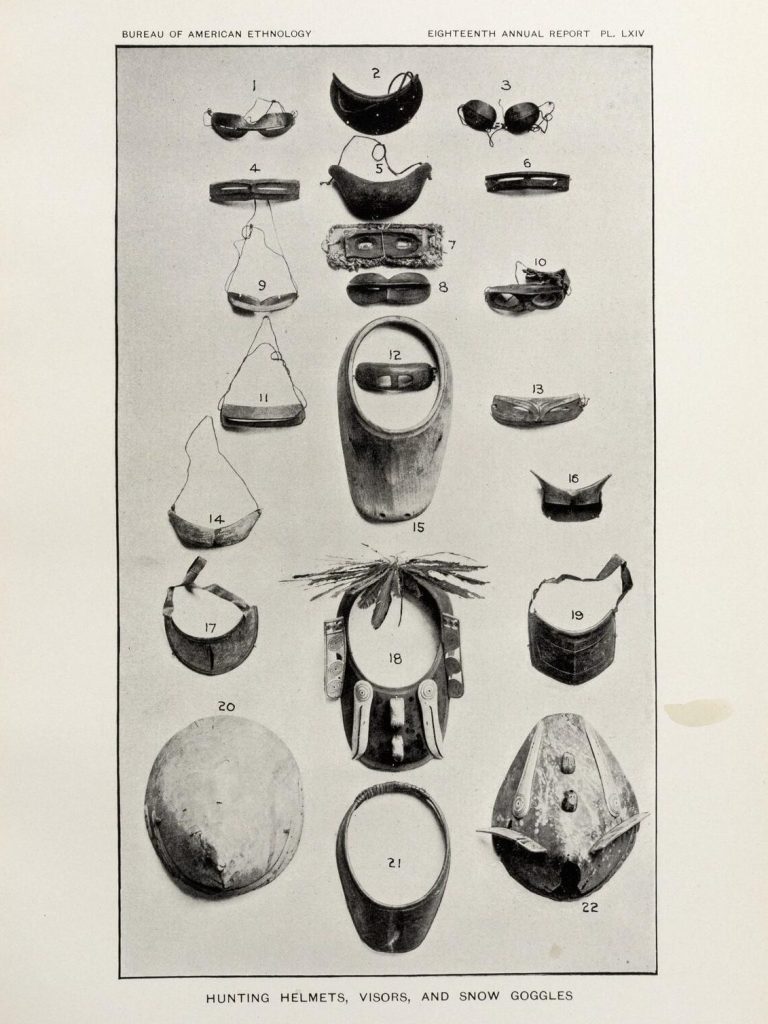

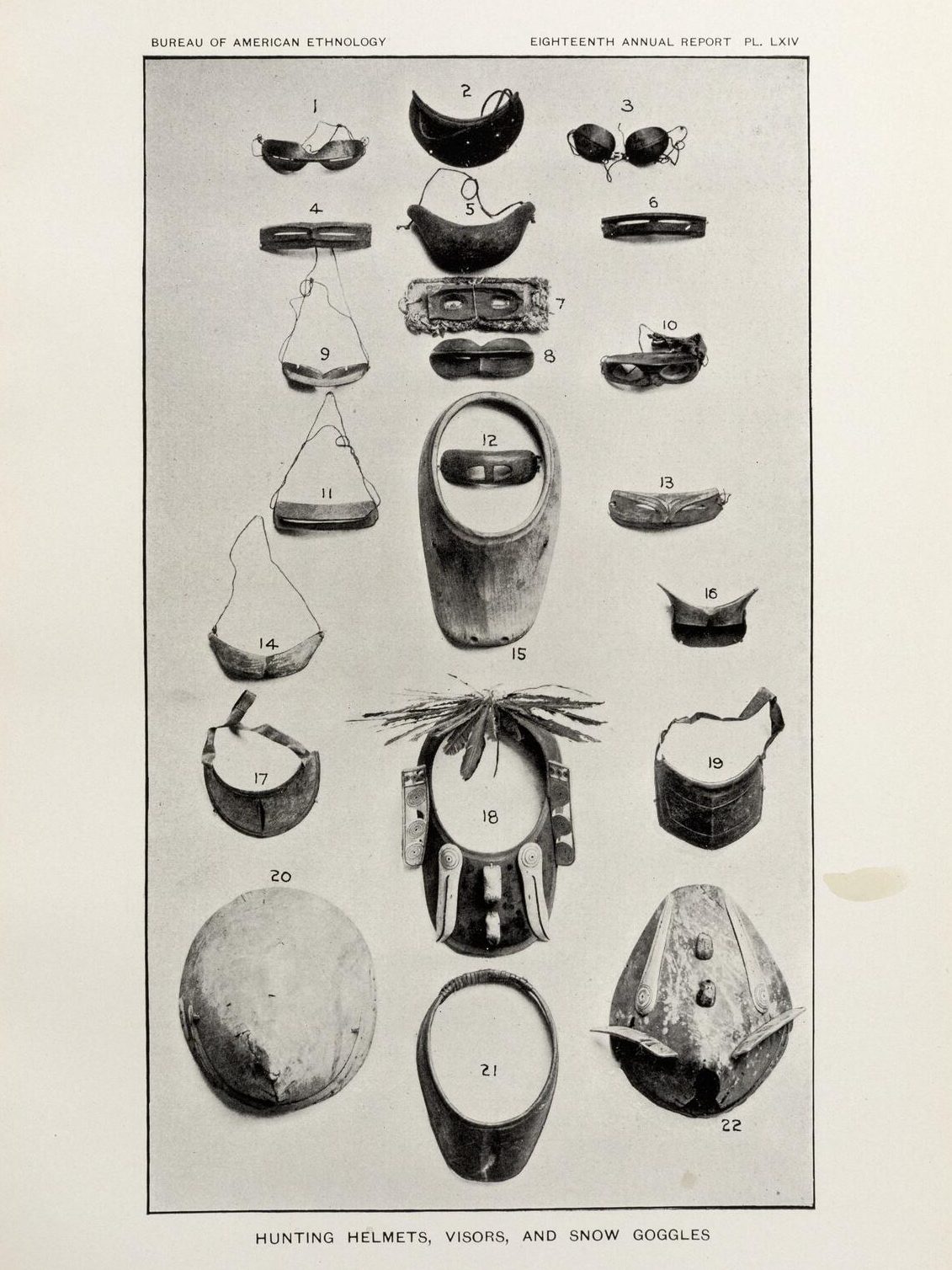

Trying to avoid this affliction, many polar explorers looked to Arctic Indigenous communities, who had thousands of years of experience in protecting their eyes from the sun. As noted by American ethnologist Edward William Nelson, “To preserve the eyes from the glare of the sun on the snow in the spring and thus prevent snow blindness, goggles are in general use among the Eskimos.”2 Nelson described several different types of goggles and other forms of eye protection in use among the Indigenous people of the Arctic. In general, they functioned by covering the eyes except for a very narrow slit, which greatly reduced an eye’s exposure to glare. The eye protectors in this image are just some of the over ten thousand artifacts that Nelson gathered on behalf of the United States National Museum (Smithsonian Institution) from 1877-81, while traveling in what is now Alaska.

Similarly, American ethnographer John Murdoch specifically noted the importance of goggles for the survival of Indigenous people in the Arctic, writing, “The wooden goggles worn to protect the eyes from snow-blindness may be considered as accessories to hunting, as they are worn chiefly by those engaged in hunting or fishing, especially when deer-hunting in the spring on the snow-covered tundra or when in the whaleboats among the ice. They are simply a wooden cover for the eyes, admitting the light by a narrow horizontal slit, which allows only a small amount of light to reach the eye and at the same time gives sufficient range of vision. Such goggles are universally employed by the Eskimos everywhere…”3

During the early days of Antarctic exploration, some explorers drew on this Indigenous Arctic technology to protect their own eyes. For example, during the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition (1910-1914), led by the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen, he and his men brainstormed possible technologies that could improve their (ultimately successful) chances at being the first to reach the geographic South Pole. Amundsen had previously been on an expedition to the Arctic from 1903 to 1906, so he was familiar with Inuit technologies. In Antarctica, Amundsen and the other Norwegians experimented with different eye covers, many of which were inspired by Inuit designs. Indeed, the man tasked with making these goggles was instructed to “prepare goggles in the Eskimo fashion.” However, many men insisted that they could improve on this design, “and every man made his own goggles.” In the end, only one man used these improvised goggles—the only man who suffered from snow-blindness.4 It was not so easy to adapt this technology as Amundsen and his men thought. This image from Amundsen’s account of the Antarctic expedition shows the Norwegians wearing their improvised goggles while sitting around the dining table at their base camp.

Dogsledding

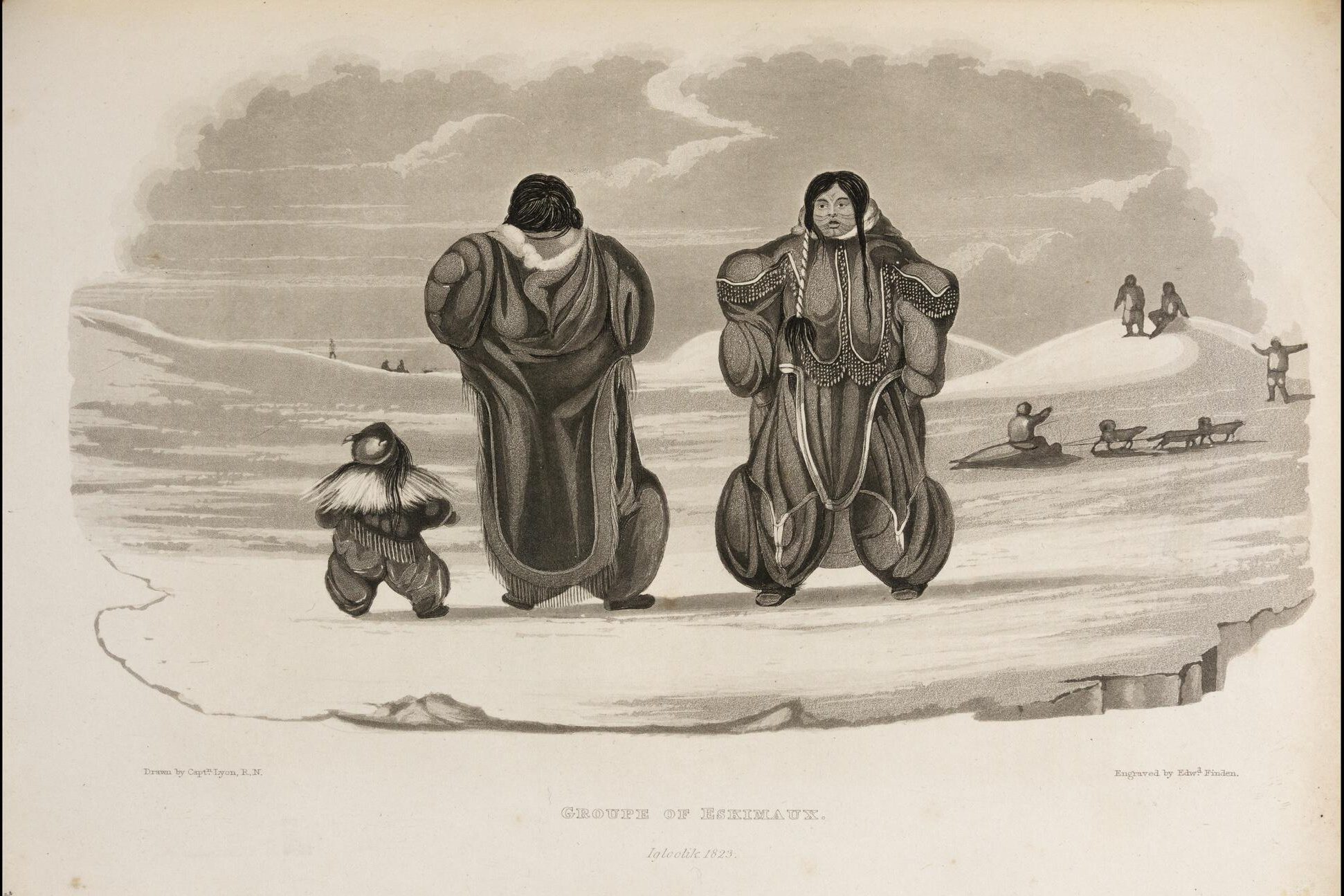

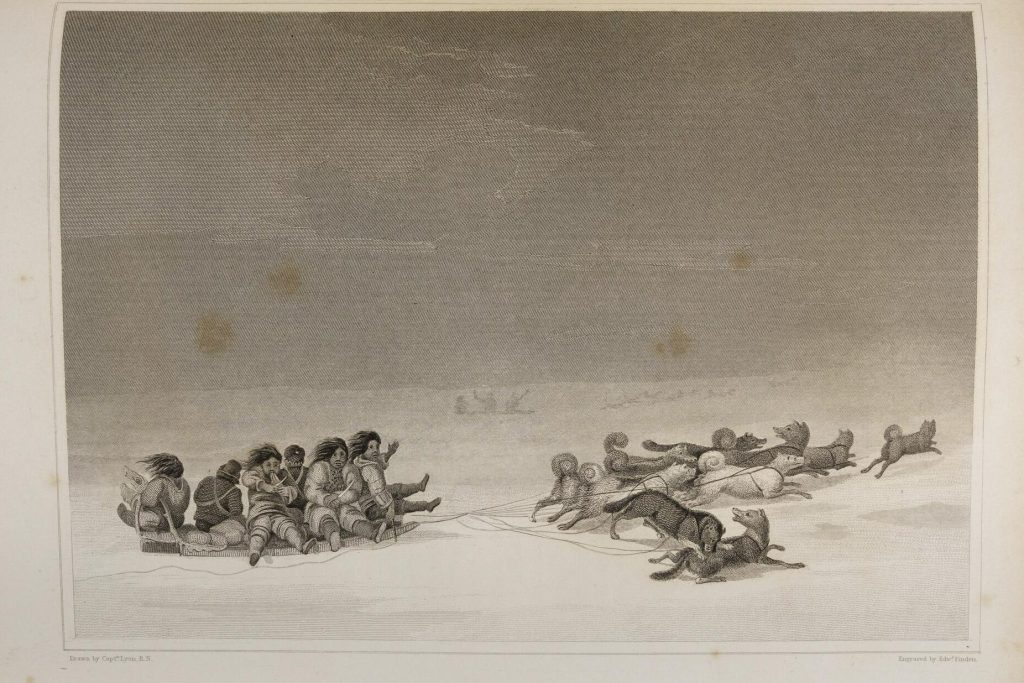

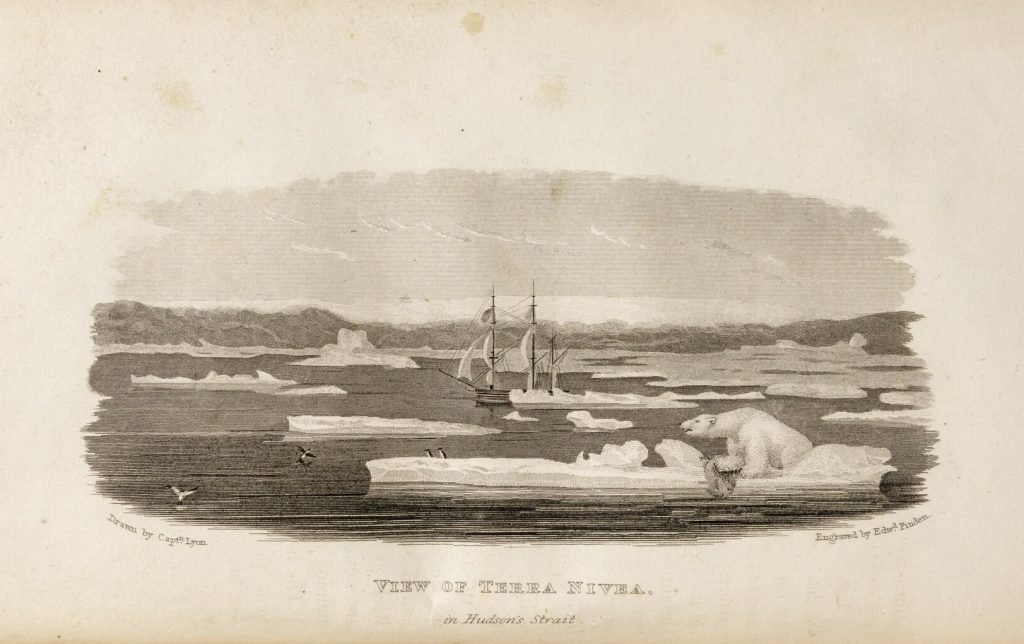

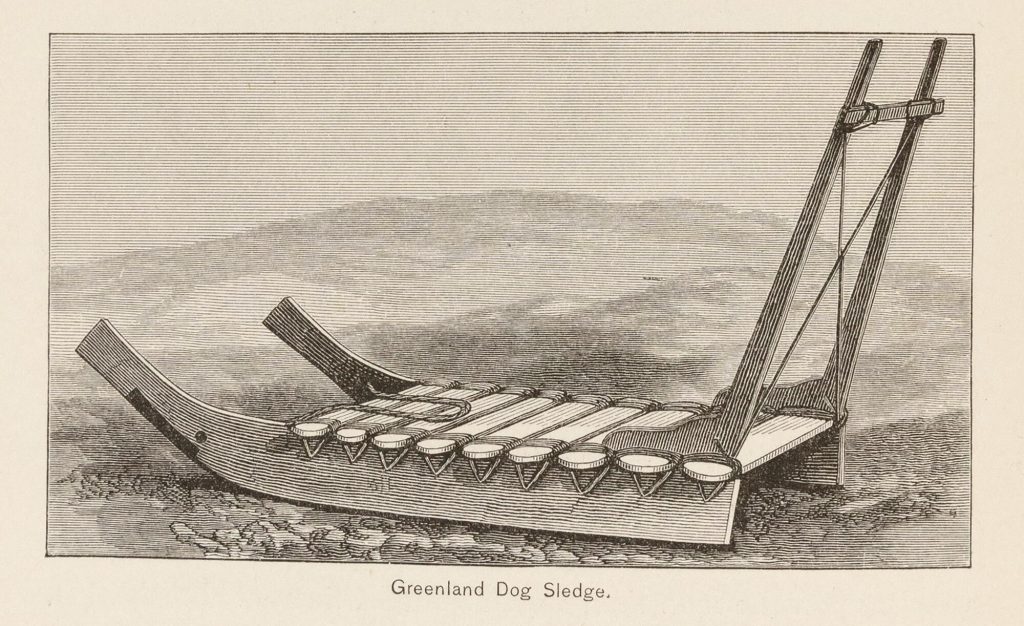

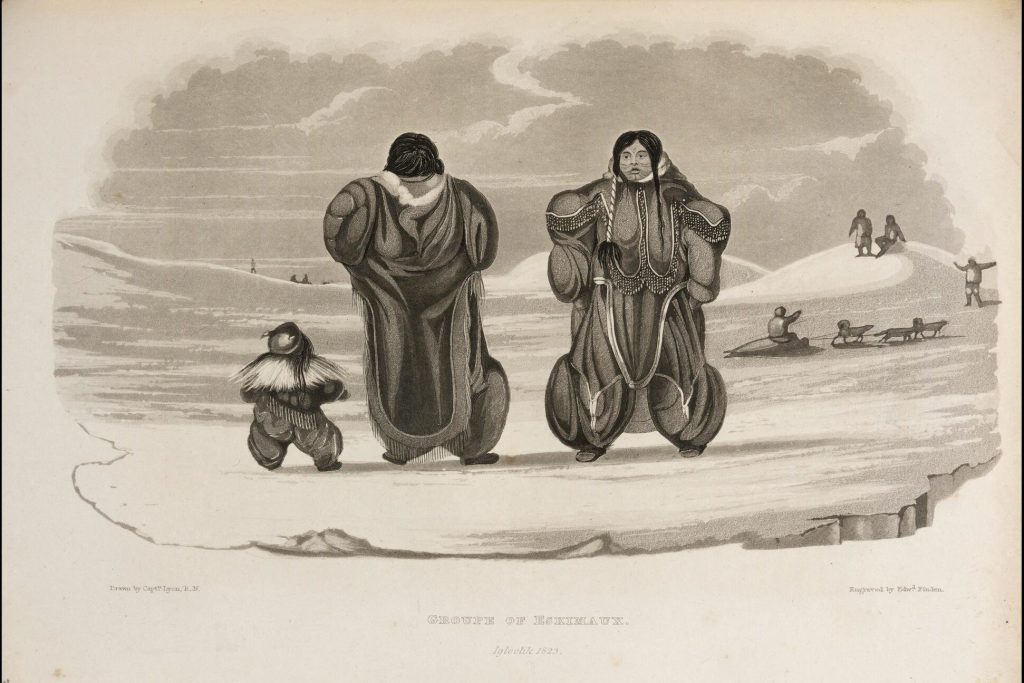

European and American explorers also drew on Indigenous expertise and technologies for their transportation in Polar regions, specifically the use of dogsledding over snowy and icy landscapes. Early European explorers took special note of the integral role of dogsledding to local Arctic societies, often including pictures of dogs and dogsledding in their publications.

From the second half of the nineteenth century forward, European and white American explorers often depended on Arctic dogs, long bred and trained by the Indigenous peoples to be ideal pullers, for travel. They also depended on Indigenous designs for their sleds, harnesses, and other related equipment. After all, American explorer Adolphus Greely wrote, “It was to be expected that long experience should make the Eskimo…cognizant of the best pattern.”5

Roald Amundsen, whose men had tried and mostly failed to adapt Indigenous snow goggles for his expedition to the South Pole, was far more successful in his adoption of Indigenous tools and techniques for travel over snowy and icy landscapes. He openly admired dogsledding as a tool for travel in Canada, Greenland, and Alaska, and before he headed south, he procured “100 of the finest Greenland dogs,” bred and trained by Indigenous Greenlanders for dog-sled travel. Criticizing British expeditions for their (generally unsuccessful) reliance on ponies in the Antarctic, he wondered if “There must be some misunderstanding or other at the bottom of the Englishmen’s estimate of the Eskimo dog’s utility in the Polar regions.”6

Amundsen also adopted Indigenous designs for dog harnesses and methods of sledging on his drive to the South Pole, which he believed were both the most efficient and the safest: “The Alaska Eskimo drive their dogs in tandem; the whole pull is this straight ahead in the direction that the sledge is going, and this undoubtably the best way of utilizing the power. I had made up my mind to adopt the same system in sledging on the Barrier. Another great advantage it had was that the dogs would pass singly across fissures, so that the danger of falling through was considerably reduced.” The whips for the dogs were also fashioned “on the Eskimo model.”7

Amundsen envied the ability of Indigenous Arctic peoples to navigate across the ice: “It is no easy matter to go straight on a surface without landmarks. Imagine an immense plain that you have to cross in thick fog; it is dead calm, and the snow lies evenly, without drifts. What would you do? An Eskimo can manage it, but none of us.”8 Copying the traveling techniques of Indigenous Arctic North Americans, in 1912 Amundsen’s party became the first men to travel to the geographic South Pole. None of Amundsen’s men died in the Antarctic.

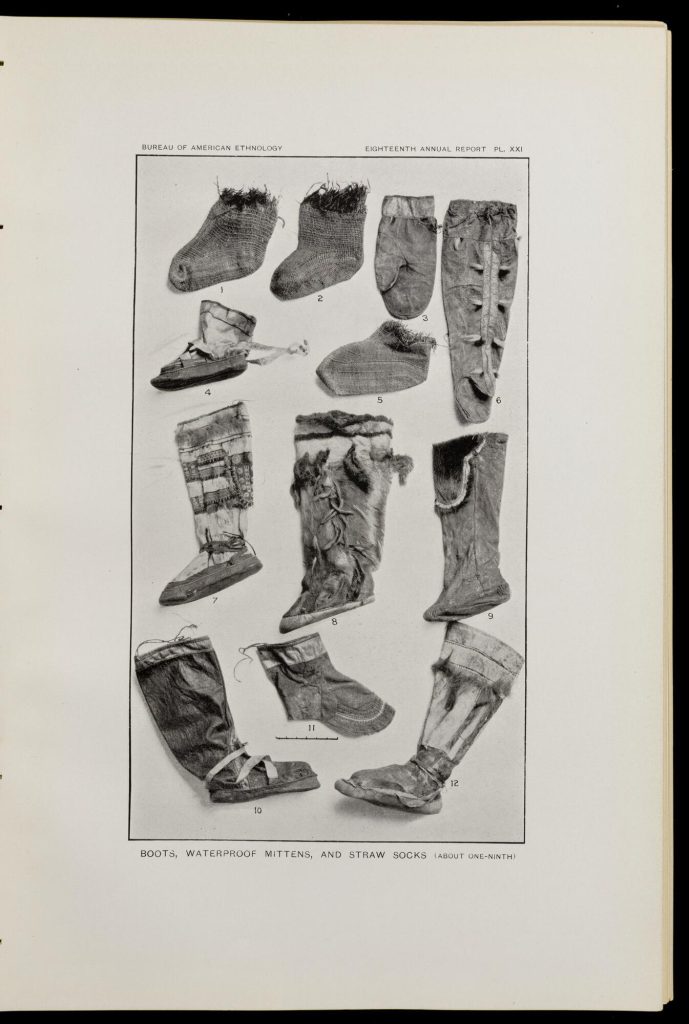

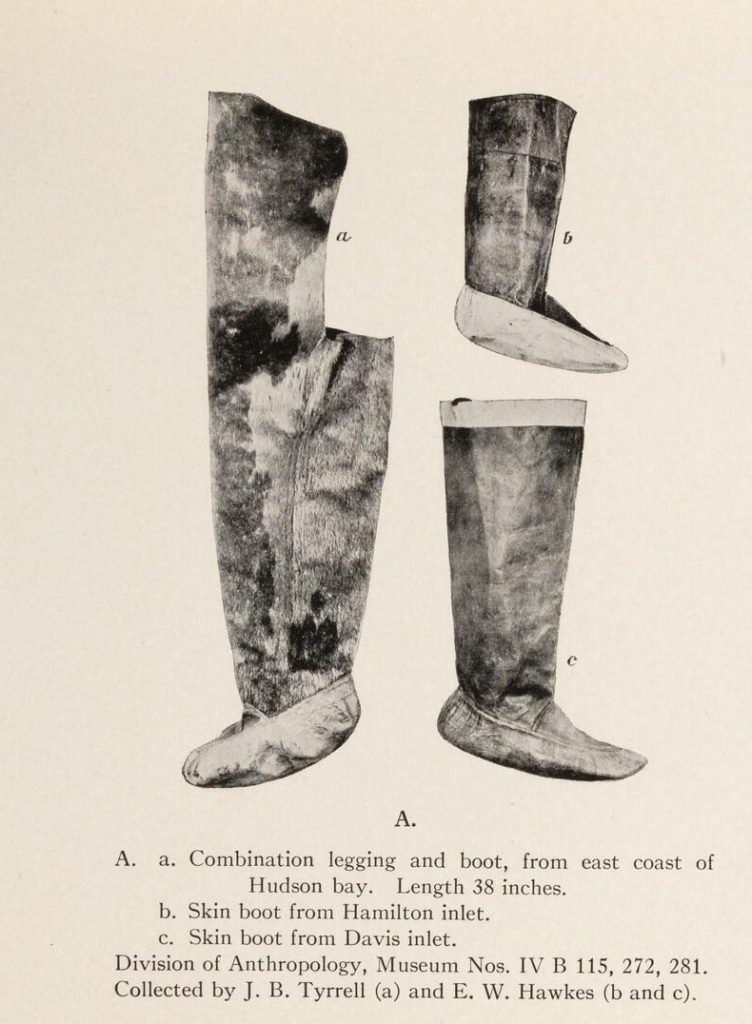

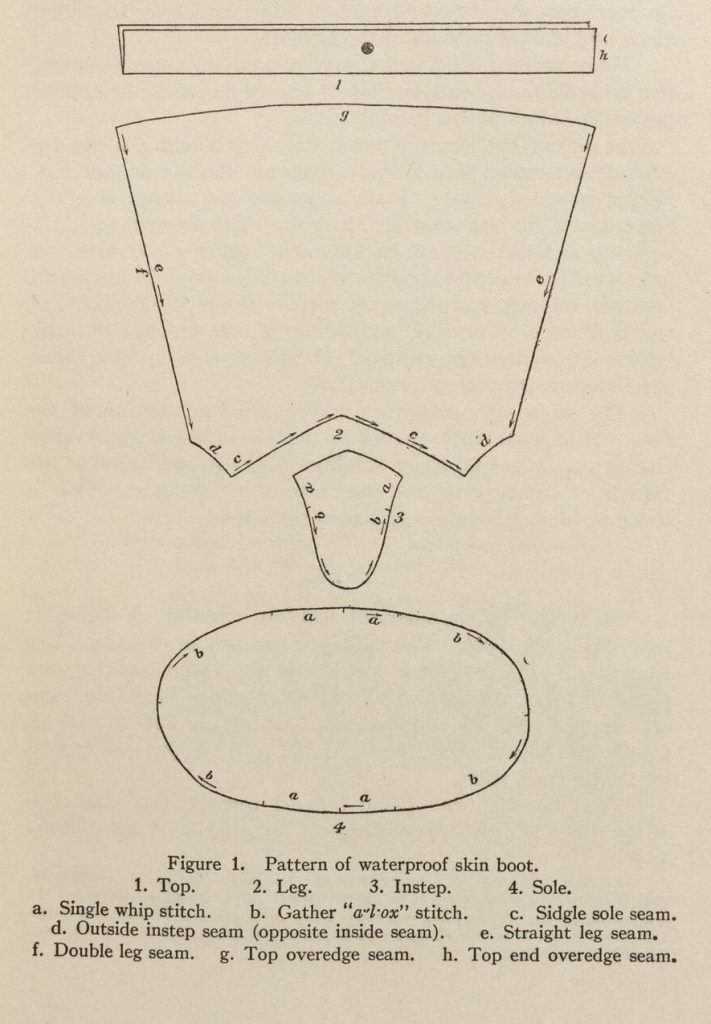

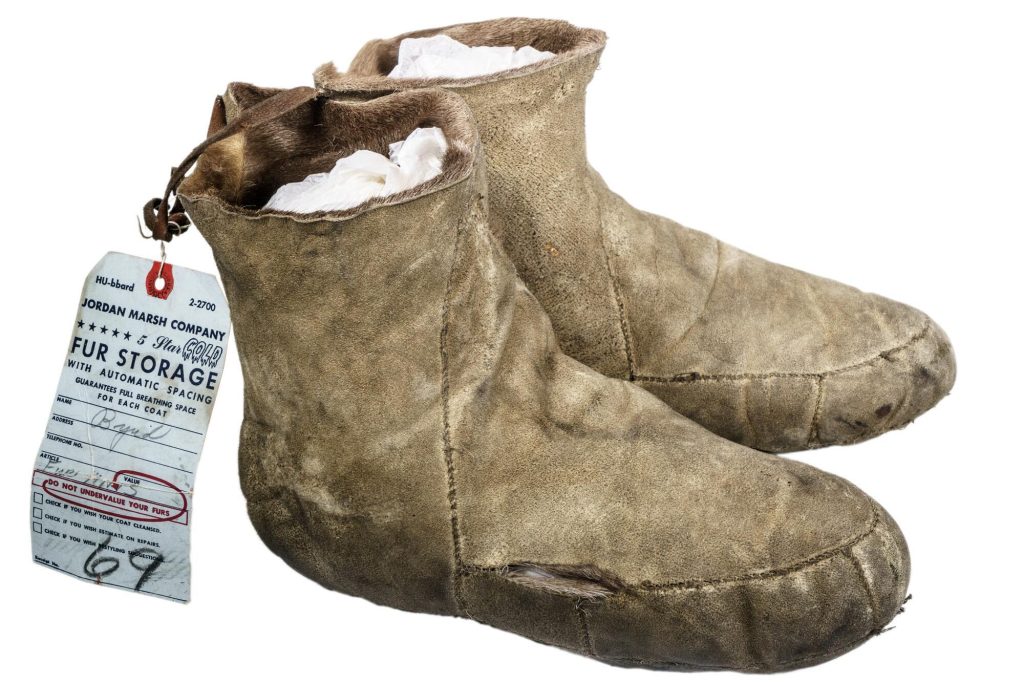

Boots

Many Indigenous people of the Arctic use clothing and footwear crafted from reindeer and seal skins (as well as a wide variety of other materials now available), although the designs vary considerably from region to region. This type of water-proof clothing was much admired and coveted by white European and North American polar travelers. Canadian explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson gushed that, “The Eskimos make admirable water boots out of seal skin.” During his Arctic travels, “We did commence wearing the Eskimo style seal skin water boots, which are lighter and in every way better than any other water boots known to me.”9

Roald Amundsen, who had traveled in the Arctic before leading an Antarctic Expedition, also wore clothing made from reindeer and seal skin. He was convinced that in the extraordinary cold of Antarctica “Skin clothing is …the only thing that is any use.” For this clothing, he drew on the expertise of the Indigenous people of the Arctic. Before traveling to Antarctica, he bought nearly 250 reindeer-skins, paid for them to be prepared by Indigenous Sámi (s-AM-me) craftsmen of Northern Scandinavia, and then made them into clothing “after the pattern of the Netchelli [Netsilik] Eskimo” of the Canadian Arctic. In low temperatures,” he continued, “these reindeer cloths are beyond comparison the best.”10 In fact, he sometimes found that they were too warm!

Another explorer who visited both the Arctic and the Antarctic and who utilized Indigenous-style clothing in both was the American aviator and explorer Richard Byrd. In 1926, Byrd attempted to fly over the North Pole in an airplane. He claimed to be successful, though it is still debated whether he in fact achieved this. In 1929, he led the first of multiple American expeditions to the Antarctic and headed a crew that was the first to fly over the South Pole. Both before and after these expeditions, Byrd’s image was widely circulated in American magazines and newspapers, often wearing the Indigenous-inspired clothing on which he had depended.

Questions for Discussion:

- Europeans often used Indigenous technology in their exploration of Polar regions. Yet while Indigenous men and women often worked as guides and dog-drivers on European-led Arctic expeditions, they were never given leadership positions on these expeditions. Additionally, no Indigenous North Americans were members of early Antarctic expeditions. What does this tell you about the relationship between white Europeans and Americans and Indigenous Arctic peoples? If Europeans and white North Americans praised and adopted Indigenous technology, why do you think they never invited Indigenous North Americans to co-lead their expeditions?

- The word “explorer” is typically attached to white American and European men who traveled in Polar regions in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Yet that word rarely gets applied to the Indigenous people who have explored and lived in the Arctic for thousands of years. Who gets to be an explorer? What constitutes “exploration”? How is exploration different now from one hundred years ago? A thousand years ago? What will it look like one hundred years in the future?

- Some of the images of snow goggles, clothing, and dogsledding tools in this essay come from the work of ethnographers (people who study the customs of other cultures). In general, the ethnographers do not describe these materials as “technologies.” Do you think they are technologies? How would you define a technology? Why does it matter whether these materials are recognized as technologies?

- If we know that many of these ethnographers and Arctic explorers harbored racist and patronizing beliefs towards Indigenous people, why do we still study their writings to learn about the history of the Arctic? What can these documents tell us? What can’t they tell us?

- Some of the technologies described in this article are no longer used in Polar regions (for example, there still is dogsledding in the Arctic, but not the Antarctic; making clothing from fur seals is illegal in the United States, except within Indigenous communities). What technologies have replaced these kinds of Arctic technologies?

The Magnetic Crusade

In the first half of the nineteenth century, men of science around the world became interested in terrestrial magnetism, or the study of the earth’s magnetic field. Many were interested in this research because they wanted to learn more about the characteristics of the earth, but some governments also saw the practical application of such research. They thought that understanding how the earth’s magnetic fields worked could lead to improvements for navigation, especially for sailing ships. For example, the compass, a key instrument in navigation, indicates direction by pointing towards the Earth’s Magnetic North Pole. While the earth has two geographic poles – the two points on Earth where its axis of rotation intersect – it also has two magnetic poles, the globe’s precise locations where magnetic intensity reaches its maximum.

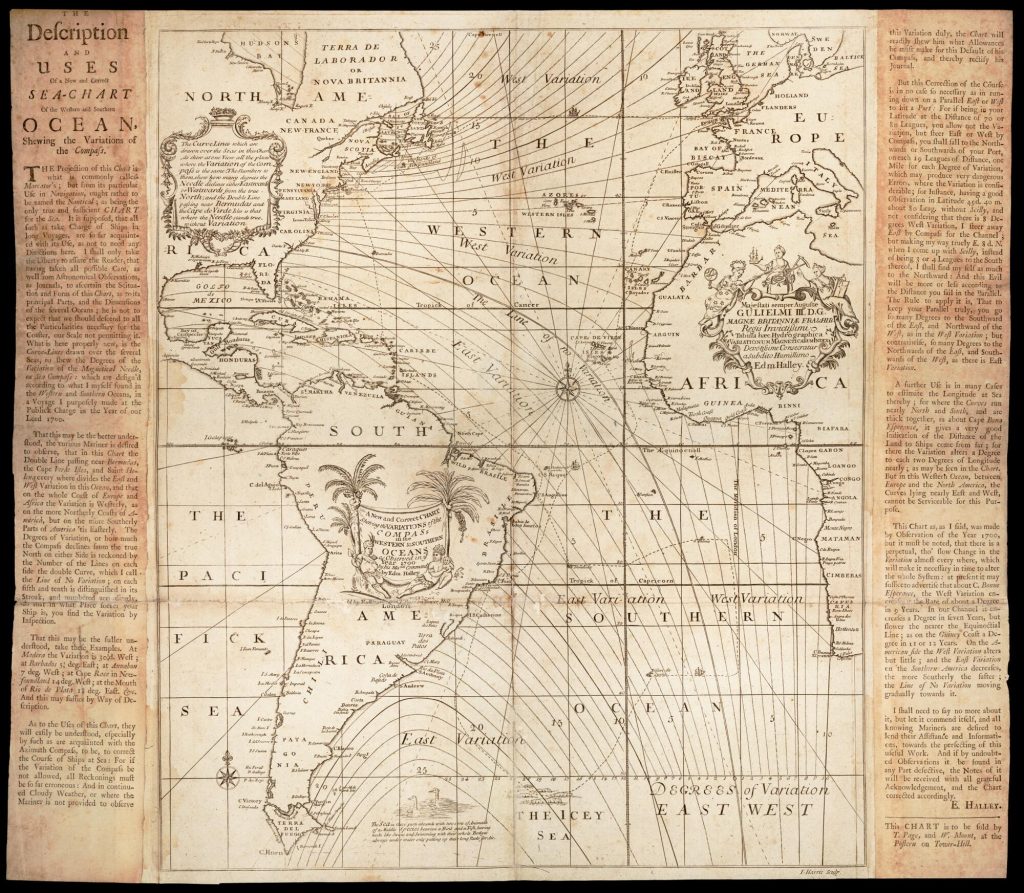

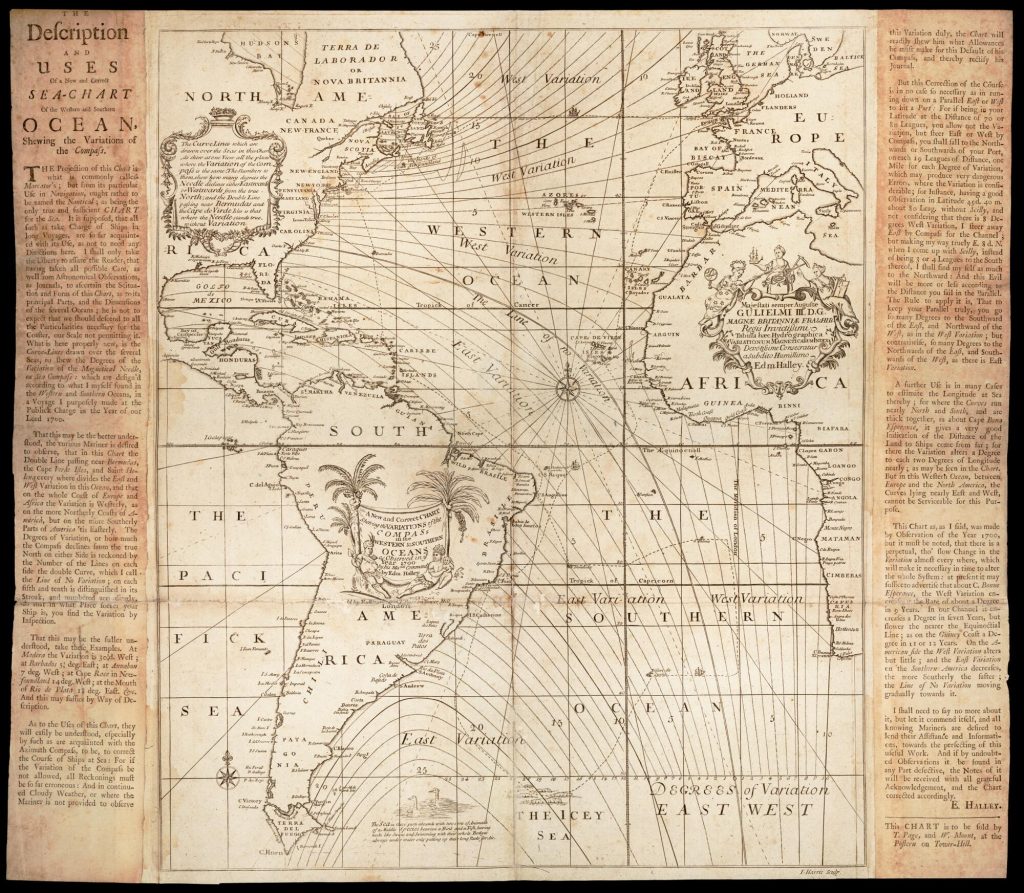

There were some individuals who had been interested in terrestrial magnetism even before the nineteenth century. In the eighteenth century, British astronomer Edmond Halley first tried to map the earth’s magnetic declination, or the variation of the magnetic north pole from the geographic north pole, in order to explain anomalies and variations in compass readings. After studying magnetism by taking compass readings on two Atlantic voyages, Halley published General Chart of the Variation of the Compass in 1701.

After Britain defeated France in the Napoleonic Wars of the early 1800s, the British Navy was the undisputed greatest in the world. It was also a key tool for managing Great Britain’s ever-expanding overseas empire. Therefore, understanding how terrestrial magnetism affected sea navigation became an important national concern in Britain. After all, according to Royal Navy officer and polar explorer James Clark Ross, “The science of magnetism, indeed, is eminently British. There is no country in the world whose interests are so deeply connected with it as a maritime nation, or whose glory as such is so intimately associated with it as Great Britain.”11 Sometimes called “The Magnetic Crusade,” the British natural philosopher William Whewell called this work “By far the greatest scientific undertaking the world has ever seen.”12

Because of earlier studies on magnetism, British scientists understood that the earth’s magnetic poles are not in exactly the same location as its geographic poles. A key feature of the Magnetic Crusade was to organize expeditions to find the precise locations of the two magnetic poles. In an expedition to the Arctic (1829-1833), James Clark Ross was a young officer serving aboard a ship under the command of his uncle, John Ross. On this expedition, James Clark Ross located the magnetic north pole on the Boothia Peninsula, in what is now Northern Canada, and “amidst mutual congratulations, we fixed the British flag on the spot and took possession of the North Magnetic Pole and its adjoining territory, in the name of Great Britain and King William the Fourth.”13

Encouraged by James Clark Ross’s continued interest in magnetism and his success in the Arctic, the British government ordered Ross to travel to the Antarctic in 1839, to amend “the deficiency, yet existing in our knowledge of terrestrial magnetism in the southern hemisphere.”14 Because finding the “existence and accessibility of two points of maximum intensity in the southern as in the northern hemisphere…is regarded as a first and, indeed indispensable step to the construction of a rigorous and complete theory of terrestrial magnetism.”15 In the Southern Ocean near Antarctica, Ross and his men were not able to reach the Magnetic South Pole in their ships, the Erebus and the Terror. However, they “had approached the pole some hundreds of miles nearer than any of our predecessors; and from the multitude of observations that were made in so many directions from it, its position may be determined with nearly as much accuracy as if we actually reached the spot itself.”16 Ross did have regrets, expressing some chagrin that he had been “compelled to abandon the perhaps too ambitious hope that I had so long cherished of being permitted to plant the flag of my country on both magnetic poles of our globe.”17

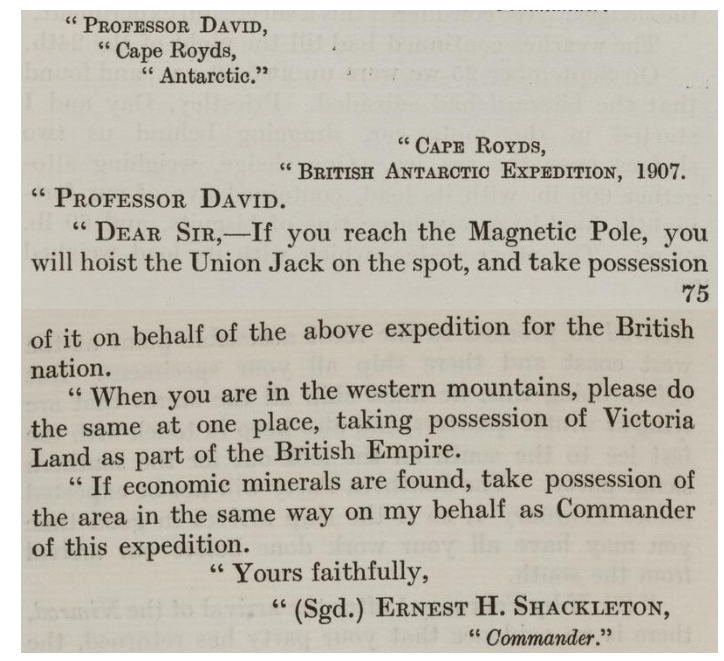

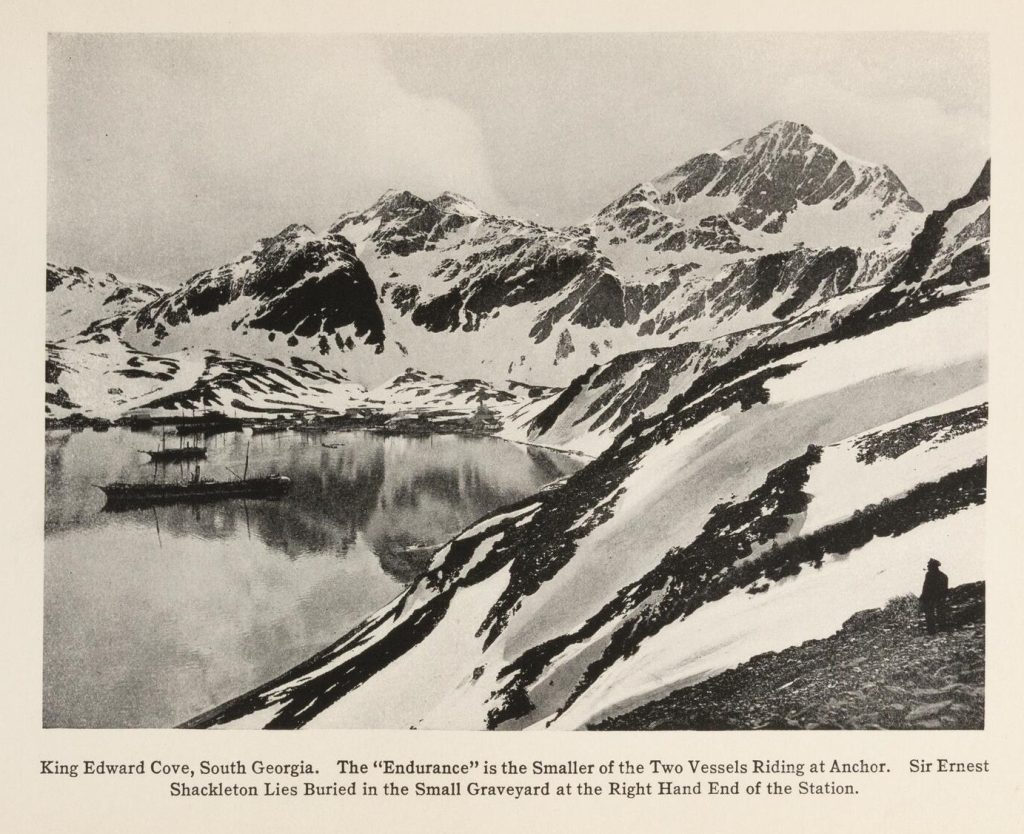

Even if Ross did not specifically locate the Magnetic South Pole, Great Britain did not abandon this goal forever. More than fifty years later, during the period known as the “Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration” (approximately 1897-1922), when many imperial powers sent expeditions to explore the Antarctic continent, the Magnetic Pole remained a priority for the British. During the Nimrod expedition (1907-09), led by the now-famous Antarctic explorer Ernest Shackleton, one of the team members was the Australian geologist Edgeworth David. David was included on this expedition so he could study the landscapes of this new territory and, among other things, determine if it held valuable minerals like gold or coal. He was also tasked with finding the Magnetic South Pole. Shackleton left David these instructions:

After a long and difficult journey, David and his team of two other men reached the South Magnetic Pole on January 16, 1908. They then “bared our heads and hoisted the Union Jack [a common nickname for the British flag] at 3:30 PM with the words uttered by myself, in conformity with Lieutenant Shackleton’s instructions, ‘I hereby take possession of this area now containing the Magnetic Pole for the British Empire.’ At the same time I fired the trigger of the camera by pulling the string. Thus the group were photographed in the matter shown in the plate.” Completing this great achievement, the three men remembered Ross and recalled that “It was an intense satisfaction and relief to all of us to feel that at last, after so many days of toil, hardship, and danger, we had been able to carry out our leader’s instructions, and to fulfill the wish of Sir James Clarke Ross that the South Magnetic Pole should actually be reached, as he had already in 1831 reached the North Magnetic Pole.”18 Weary, relieved, and grateful, David and his two companions returned to the Antarctic coast. The final task of the Magnetic Crusade had been completed.

Questions for Discussion:

- Why do you think that mapping the earth’s magnetic field was important for maritime navigation? What sort of people might specifically be interested in this information?

- Beyond the practical application of knowledge gained by locating the magnetic poles, what are some other reasons that these men might have wanted to find them?

- In this essay, you have seen men concerned with both finding the magnetic poles, which is arguably a useful scientific goal, and planting their flags on the magnetic poles, which is a political goal. What does this say about the relationship between science and the state? Is scientific discovery political? Can you think of other examples of when scientific discovery coincided with politics? Can you think of any more recent examples of people planting flags in new regions of discovery?

- The men who discovered the magnetic poles were eager to document their experiences, not only through writing, but through images. Why might they have done this? Are their words or images more convincing to you? Why?

- Compare the images of Ross planting the flag at the Magnetic North Pole and David at the Magnetic South Pole. How are these pictures similar? How are they different? What can an image created by drawing tell us that an image provided by photography cannot? What are the pros and cons of drawings and paintings versus photographs?

- During the Cold War in the mid-twentieth century, the United States built a research station at the Geographic South Pole. In response, the Soviet Union built one at the Magnetic South Pole. What connections do you see between this more recent history and the search for the magnetic poles that you just read about?

Extracting Resources from Polar Regions

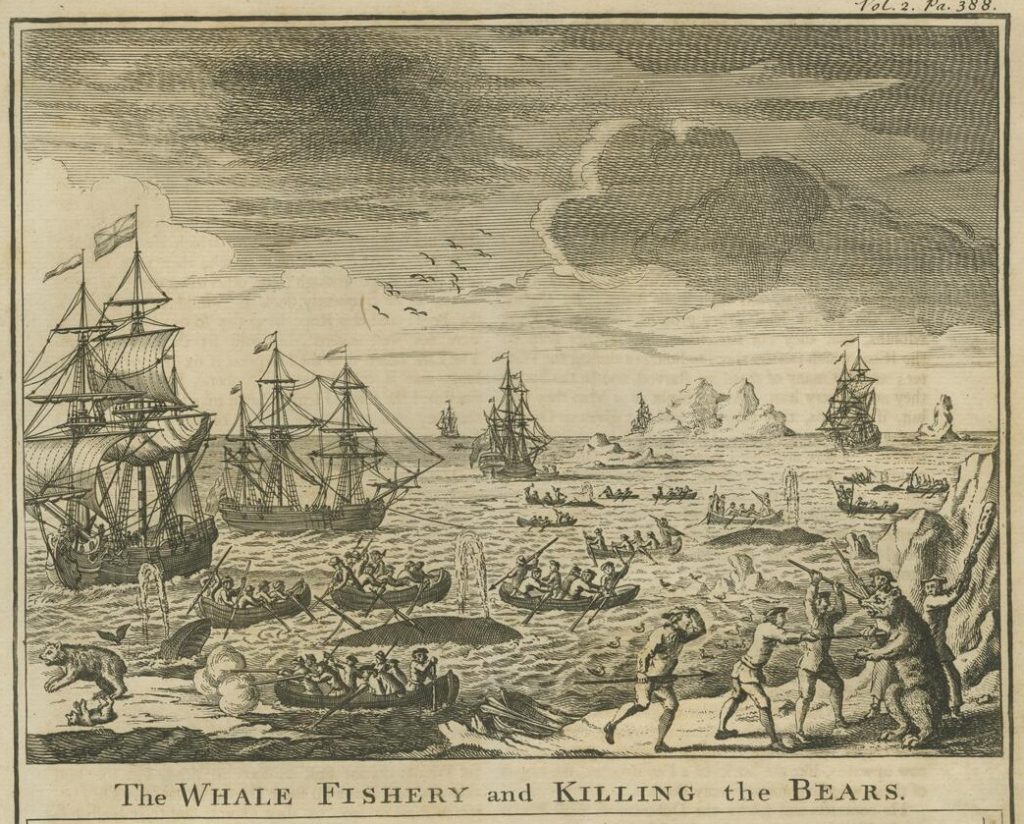

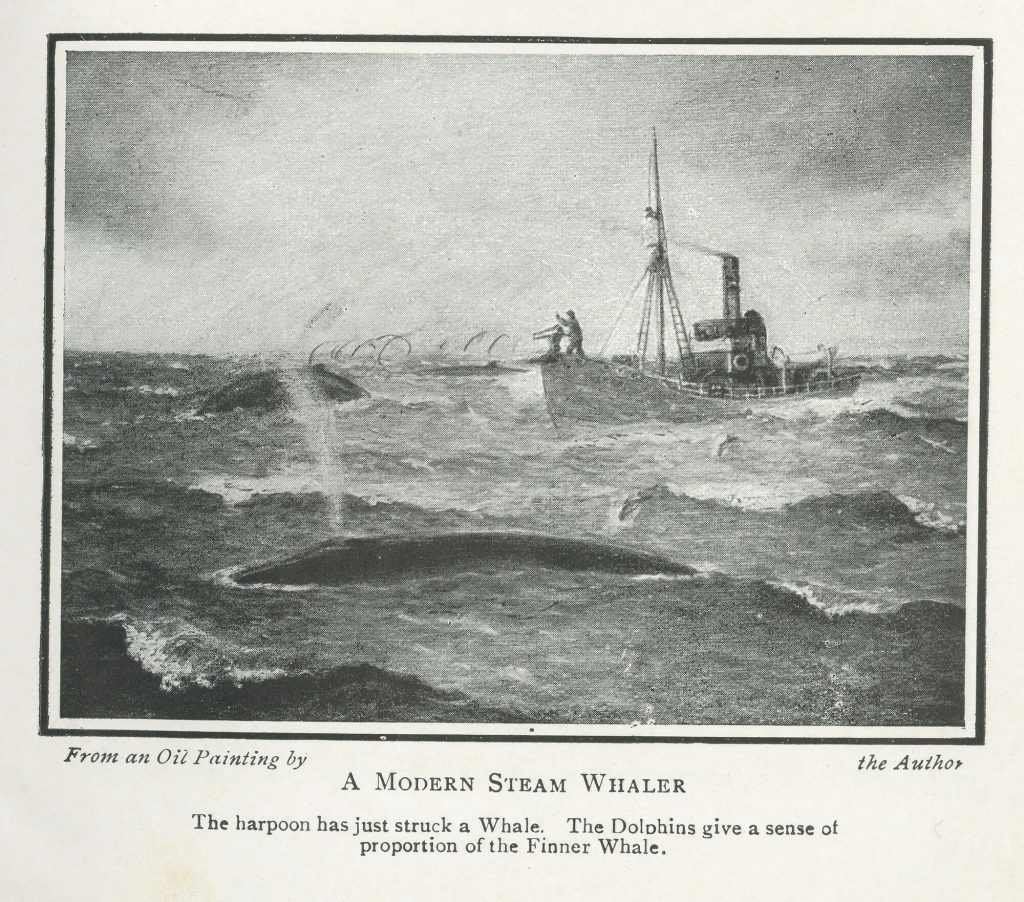

Humans are not the only species that live and travel through polar regions. Numerous animals live in both areas, and whales and seals are some of the most important. While Indigenous communities in the Arctic have depended on whales and seals for food for thousands of years, Europeans and white Americans began to make and use products from these animals on a massive scale in the seventeenth century, including whale teeth and bone, seal furs, and blubber (whale fat). This led to an increase in Europeans and Americans sailing the world’s oceans to hunt whales to meet this consumer demand. Whalers and sealers often traveled to the Arctic and Antarctic to hunt their prey. This resource extraction, which increased greatly as growing capitalist economies created more demand for whale and seal products, devastated the whale and seal populations in both polar regions.

Starting in the seventeenth century, Europeans sailed into Arctic waters, taking whales, carving them up, and sending their byproducts home. This industry began near the large Arctic island of Spitsbergen, which today is part of Norway. The hunters expanded their reach over the next two hundred years to all parts of the Arctic. Whaling was difficult and dangerous work in any region of the world. However, Arctic cold and ice caused extra dangers for whaling ships. For example, in 1871, thirty-three American whaling ships were trapped in the ice off the coast of Alaska. While miraculously all the men were rescued, the ships had to be abandoned.

During the seventeenth to twentieth centuries, whale byproducts served several uses. In the era before electricity, many people lit their homes with oil lamps or candles. Whale oil made both the best lamp oil and the best candle wax. It was used as a lubricant for machinery, important in an industrial era. In the twentieth century, while it was no longer used for lighting, whale oil remained an important lubricant for keeping factory machines running smoothly. It could also be used to make soap and cosmetics, like lipstick. In the first half of the twentieth century, it was used for margarine, comprising part of the fat intake for many people’s diets. The glycerin in whale oil was also used to make explosives, something that was vital for the countries that participated in the First World War (1914-1918).

Whale oil was not the only valuable part of a whale. Whale meat and bones were used in fertilizers. Ambergris, a substance produced by sperm whales, was used in expensive perfumes. Some whales have plates in their upper jaws made of baleen, made of the same keratin found in hair and fingernails, that filter food from seawater. In the nineteenth century, these strong and flexible plates, often called “whalebone,” were valuable for stiffening fashionable corsets and collars and making hoops to support the large dresses and skirts that were in style. Baleen had a plethora of other uses and was made into things ranging from knife handles to umbrella ribs to horseback riding crops.

By the end of the nineteenth century, Arctic whale populations had nearly collapsed from overfishing. In response, whaling companies began intensive whaling endeavors in the Antarctic starting in 1904. At this point, in 1908, Great Britain started to claim most of the Antarctic continent and its surrounding waters. One Antarctic explorer even noted later that “In Antarctica … the flag follows the trade. No nation made any definite claim to Antarctica until the development of whaling in southern waters showed that, however poor the land might be, here was a very valuable territory.”19 Before long, more whales were hunted Antarctic waters than in the rest of the world combined. British marine biologist Alister Hardy described a day he spent on the sub-Antarctic island of South Georgia in 1926, the main hub of whale processing: “It is a fantastic scene. The water in which the whales float, and on which we too are riding, is blood red. On the platform itself there are whales in all stages of dismemberment. Little figures, busy with long-handled knives like hockey sticks, look like flies as they work upon the huge carcasses.”20

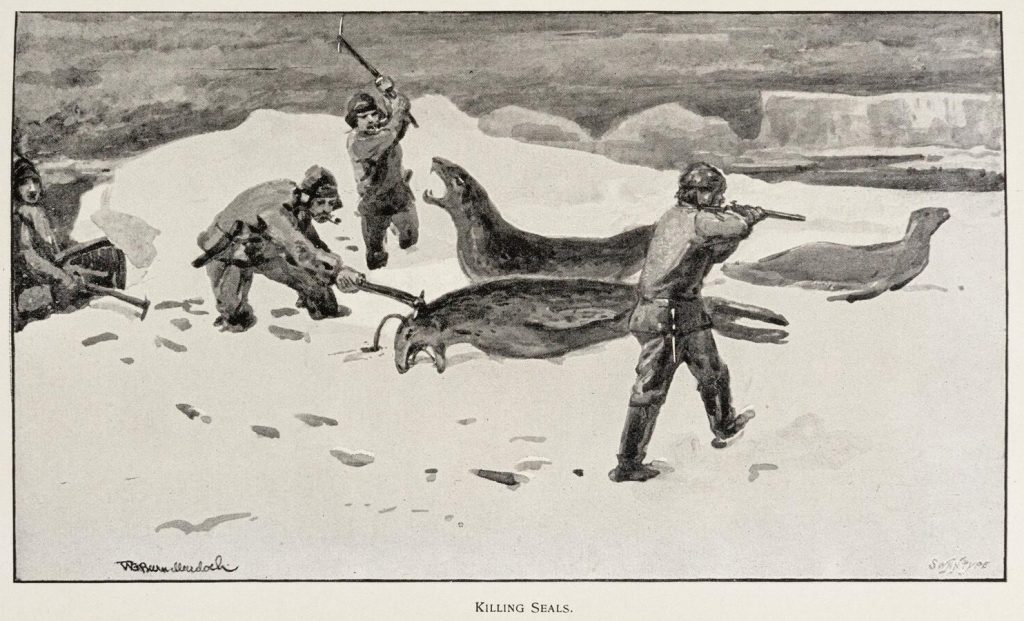

While whaling was more lucrative, seals were also targets for hunters in the Arctic and Antarctic. In fact, some of the earliest European and American explorers of Antarctica traveled to the region in search of fur seals, like the British sealer James Weddell, for whom the Weddell Sea in Antarctica is now named. Fur seal hides were used for clothing; the discovery of fur seals near the Antarctic Peninsula in the early nineteenth century led to them being hunted almost to extinction within a decade.

So rapid was this extermination that American naturalist James Eights traveled to the South Shetland Islands in the Southern Ocean in 1829, about a decade after the first landing of sealers, and observed that “This beautiful little animal was once most numerous here, but was almost exterminated by the sealers, at the time these islands were first discovered.”21 Lessons learned from this near extinction in the Antarctic led to the North Pacific Fur Seal Convention of 1911 between Japan, Russia, the United States, and Great Britain (Canada was a part of the British Empire at this time) to regulate the killing of fur seals in the Arctic region of the Pacific Ocean. This was the first international treaty addressing wildlife preservation. Throughout the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries, large elephant seals were also hunted for their oil, which was used for many of the same purposes as whale oil. In fact, there was often little distinction between whalers and sealers, as many men who were trying to hunt whales would happily kill seals and harvest their oil if they came across groups of seals. Hunters easily drove them out of the water to the beaches, lanced them through the heart (or shot them in the skull), drained their blood, and removed their blubber so it could be rendered. “We left the dead things, raw and meaty, lying on the beach,” according to one British scientist then working on a hunting vessel.22 Seabirds quickly picked the skeletons clean.

In 1946, the International Whaling Convention was established to help control whaling to prevent future collapses of the global whale population. By the late 1960s, the practice of whaling had widely died out. This was due to a number of factors. First, the rise of environmental movements worldwide led to a cultural shift toward protecting marine mammals rather than hunting them. Many people no longer saw whales (and seals, to a lesser extent) as just animals that could provide many resources, but as special, intelligent, and social individuals that merited protection above other animal species. Limits on killing whales to preserve the future stock just for hunting was no longer acceptable; today even killing one whale is generally considered bad in many parts of the world. Second, many of the products for which humans used to rely on whales, such as oil, now have cheaper synthetic alternatives, largely derived from petroleum. Today, whaling is generally only still practiced by people for whom the whale has traditionally formed part of their culture’s diet, including several Indigenous groups (notably in the Arctic), the Arctic states of Norway and Iceland, and Japan.

Questions for Discussion:

- During the entire period of intensive polar whaling, those involved knew that the supply of whales was not inexhaustible, and that the number of whales could drop until they were almost extinct. But they continued to hunt whales anyway. Do you see any parallels between this history and any modern environmental problems?

- With very few exceptions, Americans regularly consume animals or animal-related products, whether as food, leather clothing or accessories, or even fruit and vegetables grown with the help of pesticides. Even if you are vegan, it is nearly impossible to go through life without directly or indirectly harming animals. Furthermore, there are lots of highly intelligent animals that most people have no problem killing on a large scale, such as pigs. Why did commercial whaling, as opposed to other forms of animal consumption, come to be seen as especially cruel? Are whales special? Do they deserve extra protection?

- Many people have described polar regions as “wildernesses” both today and in the past. Do you think this is true? What is a wilderness?

- Look at Frank Hurley’s photograph of the coast of South Georgia. In the photograph, is the emphasis on the scenery or on the very productive whale processing facility? Is this a photograph of the “wilderness”? How might the perception that polar regions are “wildernesses” be harmful, particularly in the Arctic?

- Whaling and sealing died away in a large part because of the availability of cheap alternatives to the products that whales and seals produced for humans. One of the most widely used alternatives to these products is plastic, which has replaced whale baleen for items like cutlery handles and fashion accessories. How often do you use plastic? Can you plan a day when you would not touch plastic at all? What alternatives can you use for each plastic item that you use in your daily life?

- Outside of the Polar regions, can you think about other ways that animals have played a role in history? What are some specific examples that come to mind?

Indigenous Technologies and White Polar Explorers

Snow Goggles

Dogsledding

Boots

The Magnetic Crusade

Extracting Resources from Polar Regions

- Ernest Shackleton, The Heart of the Antarctic (1909). ↩︎

- Edward William Nelson, The Eskimo about the Bering Strait (1900), 169. ↩︎

- John Murdoch, Ethnological Results of the Point Barrow Expedition (1892), 260-261. ↩︎

- Roald Amundsen, K Prestrud, and Thorvald Nilsen. The South Pole (1912), 362, 368. ↩︎

- A.W. Greely, Three Years of Arctic Service (1886), 200. ↩︎

- Amundsen, et al., The South Pole, 56, 58. ↩︎

- Amundsen, et al., The South Pole, 86, 359. ↩︎

- Amundsen, et al., The South Pole, 212. ↩︎

- Vilhjalmur Stefansson, Hunters of the Great North (1923), 99, 192. ↩︎

- Amundsen, et al., The South Pole, 220, 78, 209. ↩︎

- James Clark Ross, “On the Position of the North Magnetic Pole,” in Robert Huish, The Last Voyage of Capt. Sir John Ross (1835), 28. ↩︎

- William Whewell, History of the Inductive Sciences (1857), 55. ↩︎

- John Ross, et al., Narrative of a Second Voyage in Search of a North-West Passage (1835), 359. ↩︎

- J.S. Herschell, “Introduction,” in James Clark Ross, A Voyage of Discovery and Research in the Southern and Antarctic Regions (1847), vi. ↩︎

- Herschell, “Introduction,” viii-xvi. ↩︎

- Ross, A Voyage of Discovery and Research in the Southern and Antarctic Regions (1847), 246. ↩︎

- Ross, A Voyage of Discovery and Research, 247. ↩︎

- Edgeworth David, “Narrative of Professor David,” in The Heart of the Antarctic, 310 ↩︎

- Thomas Griffith Taylor, Antarctic Adventure and Research (1930), 220. ↩︎

- Alister Clavering Hardy, Great Waters (1967), 161. ↩︎

- Edmund Fanning, Voyages to the South Seas, Indian and Pacific Oceans, China Sea, North-West Coast, Feejee Islands, South Shetlands, &c. (1838), 209. ↩︎

- F.D. Ommanney, South Latitude (1938). ↩︎